Abstract

Rationale: Oxidative stress, resulting from excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), plays an important role in the initiation and progression of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Therefore, developing novel strategies to target the disease location and treat inflammation is urgently needed.

Methods: Herein, we designed and developed a novel and effective antioxidant orally-administered nanoplatform based on simulated gastric fluid (SGF)-stabilized titanium carbide MXene nanosheets (Ti3C2 NSs) with excellent biosafety and multiple ROS-scavenging abilities for IBD therapy.

Results: This broad-spectrum and efficient ROS scavenging performance was mainly relied on the strong reducibility of Ti-C bound. Intracellular ROS levels confirmed that Ti3C2 NSs could efficiently eliminate excess ROS against oxidative stress-induced cell damage. Following oral administration, negatively-charged Ti3C2 NSs specifically adsorbed onto the positively-charged inflamed colon tissue via electrostatic interaction, leading to efficient therapy of dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS)-induced colitis. The therapeutic mechanism mainly attributed to decreased ROS levels and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, and increased M2-phenotype macrophage infiltration and anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion, efficiently inhibiting inflammation and alleviating colitis symptoms. Due to their excellent ROS-scavenging performance, Ti3C2-based woundplast also promoted skin wound healing and functional vessel formation.

Conclusions: Our study introduces redox-mediated antioxidant MXene nanoplatform as a novel type of orally administered nanoagents for treating IBD and other inflammatory diseases of the digestive tract.

Keywords: Ti3C2 nanosheets, ROS scavenging, oral administration, anti-inflammation, IBD therapy

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with two main clinical forms, including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease, is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. Its prevalence adversely affects millions of people around the world 1-3. Though IBD deaths are low, IBD patients are at an increased risk of suffering more serious diseases like colon cancer 4, 5. Currently, small molecular drugs and antibiotics are the treatment options, but these strategies cannot completely cure IBD due to the lack of specificity, and further increasing the drug dose causes severe side-effects 6-8. Consequently, many IBD-targeted therapies rely on pH-, pressure-, and time-dependent therapeutic systems 9. However, most of these therapeutic systems are delivered via the bloodstream, targeting the entire colon, and few are specific to the inflamed colonic lesions 10. Therefore, developing novel strategies to target the disease location and treat inflammation is urgently needed.

During the progression of IBD, toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) cause biomolecular damage, such as lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and protein denaturation, thereby triggering high oxidative stress and excessive inflammatory response 11-13. Also, the presence of positively charged proteins in the inflamed colon lesions has been reported 11, 14, 15. Thus, developing novel therapeutic systems with negative charge to target positively charged proteins via electrostatic interactions and eliminating excess ROS for alleviating inflammation was an extremely effective treatment for IBD. For instance, multi-enzymes encapsulated into liposomes, montmorillonite-anchored ceria nanoparticles, and redox nanoparticles with negative charge were successfully constructed to scavenge ROS for IBD therapy 16-19. However, the instability of natural enzymes, nanozymes, or other therapeutic agents in the harsh, acidic, and enzyme-rich environment encountered in the complex gastrointestinal tract may reduce their pharmacological activities and affect in vivo performance 20. Consequently, innovative antioxidant strategies are urgently required to effectively prevent and resolve intestinal inflammation in IBD.

Currently, two-dimensional titanium carbide MXene nanosheets (2D Ti3C2 NSs) with ultrathin layer-structured topology have attracted much attention for biomedical applications 21, 22. In this context, Ti3C2 NSs with intrinsic Ti-C redox-active sites show profound chemical reactivity toward ROS, and can serve as an efficient antioxidant to treat many ROS-related diseases, including IBD 23. Due to their specificity, stability, and good ROS scavenging, we employed Ti3C2 NSs as novel orally administered ROS scavengers specifically targeted to the inflamed colon lesions via electrostatic interactions for IBD treatment (Scheme 1). Ti3C2 NSs were synthesized by a two-step exfoliation method and exhibited broad-spectrum redox-mediated ROS scavenging activity. The intracellular ROS levels confirmed that Ti3C2 NSs could efficiently eliminate excess ROS against oxidative stress-induced cell damage. Moreover, the negatively-charged Ti3C2 NSs could be specifically adsorbed onto positively-charged inflamed colon tissue after oral administration, leading to efficient therapy of dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS)-induced colitis. The therapeutic mechanism was mainly attributed to decreased ROS levels and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and increased M2-phenotype macrophage infiltration and anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion, efficiently inhibiting inflammation and alleviating colitis symptoms. Additionally, Ti3C2-based woundplasts have been employed to promote skin wound healing and functional vessel formation due to their excellent ROS scavenging ability. Thus, our study highlights an effective strategy based on 2D Ti3C2 NSs to treat IBD disease via redox-mediated antioxidative protection.

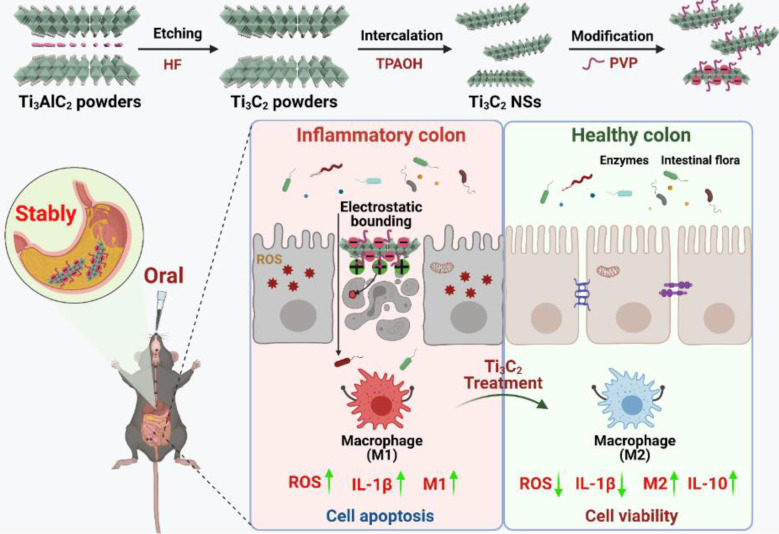

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration shows the preparation and application of Ti3C2 NSs. The route of Ti3C2 MXene prepared from the Ti3AlC2 MAX phase and the surface modification of them by PVP polymer. After oral administration of gastric acid-tolerant Ti3C2 NSs, they could bind to the inflamed mucosa through electrostatic force in the colon. Ti3C2 NSs could scavenge the excess reactive oxygens species (ROS) and regulate the phenotype of macrophages at the inflammation site, and thus relieve inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Results and Discussion

2D Ti3C2 NSs were synthesized via a two-step exfoliation strategy based on hydrofluoric acid (HF) etching and tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH) intercalation of titanium aluminum carbide (Ti3AlC2) powder (Figure 1A) 24-26. Initially, the Ti3AlC2 MAX phase with a layered morphology was etched with 20% HF solution for 4 h to remove Al layers. Subsequently, TPAOH aqueous solution was employed to insert the etched Ti3C2 flakes to reduce the sheet thickness (Figure 1B-C). The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image revealed that the synthesized Ti3C2 NSs exhibited typical sheet-like morphology with an average size of ~500 nm (Figure 1E). The lattice spacing of ~0.26 nm obtained from the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image corresponded with the standard Ti3C2 (JCPDS No. 65-0242) (Figure 1F-H). The energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) elemental mapping displayed the homogeneous distribution of Ti and C elements in Ti3C2 NSs (Figure 1D). As a sheet morphology, the height of Ti3C2 NSs determined by atomic force microscopy (AFM) was ~1.39 nm (Figure 1I-J). Importantly, this two-step exfoliation strategy could be scaled-up to prepare large amounts of high quality Ti3C2 NSs that could be well dispersed in water for a long-term storage (Figure 1G,1K-L). However, they would aggregate in the salt solution and showed poor biocompatibility (Figure S1). Therefore, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, MW 10k) polymer was used to stabilize Ti3C2 NSs via the steric hindrance among the macromolecular chains. Typical C=O and C-N signals in the Ti3C2-PVP sample were observed by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, indicating successful PVP modification onto the surface of Ti3C2 NSs (Figure S2). The amount of PVP modified on the surface of Ti3C2 NSs measured by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was ~12.4% (Figure S3). The PVP-modified Ti3C2 NSs exhibited excellent dispersity and long-term colloidal stability without significant dimensional change in H2O, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Figure 1L, Figure S4). Importantly, these Ti3C2-PVP NSs showed excellent long-time stability in simulated gastric fluid (SGF, pH = 1.5) and simulated intestinal fluid (SIF, pH = 6.8), indicating their suitability for oral administration. TEM and X-ray diffraction (XRD) characterization showed no change in the morphology and nanostructure of Ti3C2-PVP NSs after 5 h incubation in SGF (Figure 1M-O). Also, the UV-vis-NIR absorption spectra of Ti3C2-PVP NSs and SGF-incubated Ti3C2-PVP NSs showed no noticeable difference, further verifying the excellent acid corrosion resistance of Ti3C2-PVP NSs (Figure 1P). Finally, we investigated the surface potential of Ti3C2 NSs after incubation with SGF, and found that SGF-treated Ti3C2 NSs still had a negative charge (Figure S5), confirming the strong stability of Ti3C2 NSs in SGF. Together, these results verified the acid stability of Ti3C2 NSs, which could be used as a novel oral administration for treating inflammatory diseases of the digestive tract.

Figure 1.

Synthesis and characterization of 2D ultrathin Ti3C2 NSs (MXenes). (A) Scheme shows the synthesis procedures of Ti3C2 NSs and their surface modification. (B-C) SEM images of Ti3AlC2 powders and TPAOH-intercalated Ti3C2 (inset is the corresponding high-magnification SEM images). (D) High-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM) image of Ti3C2 NSs and the element distribution of Ti (green) and C (red) onside the Ti3C2 NSs. (E-F) TEM and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images of as-synthesized Ti3C2 NSs. (G) A photograph of Ti3C2 NSs in water (2 mg/mL). (H) XRD spectra of the Ti3AlC2 MAX phase and Ti3C2 Mxene. (I-J) AFM image of the Ti3C2 NSs and the height profiles along the red lines. (K) The obvious Tyndall effect of the Ti3C2 NSs in H2O. (L) The stability of the PVP-modified Ti3C2 NSs in various buffers including H2O, PBS, DMEM, SGF, and SIF. (M) The stability of the PVP-modified Ti3C2 NSs in SGF for 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, and 5 h. (N-P) TEM images, XRD spectrum, and UV-vis-NIR spectra of Ti3C2 NSs before and after incubation in SGF for 5 h.

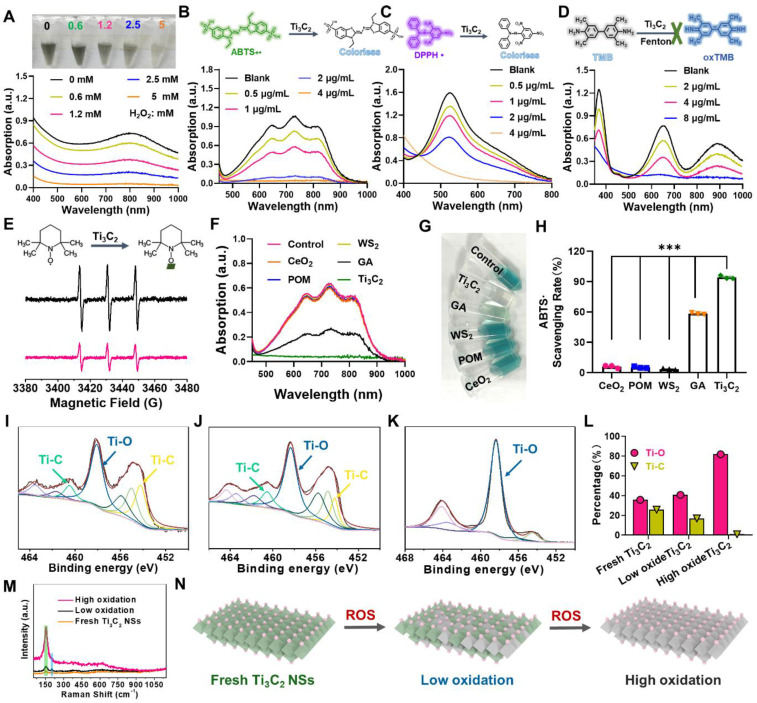

Considering the key role of reactive oxide/nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) in inflammatory diseases, the potential of Ti3C2 NSs as ROS/RNS scavengers was evaluated. Initially, the color of Ti3C2 NSs suspension gradually faded to colorless after incubation with different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2: 0.6, 1.2, 2.5, and 5 mM), and their UV-vis-NIR absorption spectra disappeared as the H2O2 concentration increased, indicating the reactivity and scavenging ability of Ti3C2 NSs toward H2O2 (Figure 2A). The UV-vis-NIR absorption spectra of two intrinsic RNS, 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radicals (DPPH•) and 2, 2-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical (ABTS+•), decreased significantly after mixing with Ti3C2 NSs (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μg/mL). Also, Ti3C2 NSs could scavenge almost all of RNS at a low concentration (2 μg/mL), suggesting an excellent radical-scavenging ability of the synthesized Ti3C2 NSs (Figure 2B-C).

Figure 2.

The performance and the probable mechanism of ROS scavenging by Ti3C2 NSs. (A) UV-vis absorbance spectra of H2O2-treated Ti3C2 NSs (H2O2 concentrations: 0.6, 1.2, 2.5, and 5 mM). (B-C) UV-vis absorbance spectra of ABTS+• and DPPH• radicals after incubation with Ti3C2 NSs at different concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μg/mL). (D) UV-vis absorbance spectra of TMB after co-incubation with Fenton agent and Ti3C2 NSs (Fe2+: 10 μM, H2O2: 50 μM, TMB: 0.3 mM; Ti3C2: 2, 4, and 8 μg/mL). (E) ESR spectra of TEMPO indicating radical scavenging ability of Ti3C2 NSs. (F) UV-vis absorbance spectra of ABTS+• radical after incubation with same concentrations of the CeO2, POM, WS2, GA and Ti3C2 NSs for 1 min (dose: 2 μg/mL). (G) A photograph of the above-mentioned solutions after reaction. (H) The quantitative analysis of ABTS+• scavenging rate by them. (I-L) XPS spectra of Ti 2P from Ti3C2 NSs with different degree of oxidation and corresponding peak area. (M) Raman spectra of Ti3C2 NSs with different degree of oxidation. (N) Schematic diagram of the antioxidant mechanism of Ti3C2 NSs. The statistical significance was calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001.

The superior antioxidant activity and stability of Ti3C2 NSs were confirmed by ABTS+• scavenging experiments (Figure S6-S9). Besides, the ROS-scavenging efficiency of Ti3C2 NSs was evaluated by hydroxyl radicals (HO•), regarded as one of the strong free radicals frequently involved in cell injuries and body diseases. A peroxidase substrate, 3,3,5,5-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB), used as an HO• indicator (colorless) could be oxidized into oxTMB (blue) by HO• (Figure 2D). The blue color of the reaction system sharply faded by adding Ti3C2 NSs, indicating a significant decrease in the HO•-induced oxTMB concentration. Moreover, TMB was not easily oxidized by HO• in the presence of Ti3C2 NSs at a much lower concentration (8 μg/mL), further indicating an excellent ROS scavenging ability of Ti3C2 NSs. Also, the terephthalic acid (TA) fluorescence probe, as a specific HO• indicator, confirmed the exceptional HO•-scavenging performance of Ti3C2 NSs (Figure S10). Lastly, 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO, intrinsic free radical) was employed to examine the antioxidative properties of Ti3C2 NSs by electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra. The results showed that the characteristic peaks of TEMPO could be effectively eliminated by Ti3C2 NSs, confirming the excellent antioxidative properties of Ti3C2 NSs (Figure 2E, Figure S11). Taken together, Ti3C2 NSs exhibited broad-spectrum and efficient ROS-scavenging ability to treat inflammatory diseases.

Then, a series of experiments were performed to understand the excellent anti-oxidant properties of Ti3C2 NSs and analyze structural changes of Ti3C2 NSs after ROS scavenging. As revealed by TEM imaging, Ti3C2 NSs degraded into ultra-small nanodots after reaction with ROS (Figure S12), and XRD spectra showed the disappearance of Ti3C2 NSs characteristic peaks during this process (Figure S13). X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS) spectra of Ti 2p showed oxidation of Ti3C2 NSs into Ti-based oxides after elimination of ROS compared with the original Ti3C2 NSs (Figure 2I-K). The two characteristic Ti-C peaks (460.5 eV and 454.2 eV) almost disappeared, and the peak intensity decreased from 25.7% to 0.9% while the intensity of Ti-O peaks (458.1 eV) significantly increased from 35.7% to 81.7% (Figure 2L), indicating intensive oxidation of Ti3C2 NSs during ROS scavenging.

We also performed Raman spectrum to analyze the surface change of Ti3C2 NSs during ROS scavenging. Notably, the characteristic peak of Ti3C2 NSs at 260 cm-1 (namely Ti-C) significantly decreased after ROS treatment, while an enhanced peak at 155 cm-1 (Ti-O) was observed in the ROS-treated samples, demonstrating that Ti-O was generated from Ti-C and then accumulated on the surface of Ti3C2 NSs (Figure 2M, Figure S14-S15) 27-29. The strong ROS scavenging could be explained by the following mechanism: Ti3C2 NSs scavenge ROS through the oxidation-reduction reactions between Ti-C and ROS, leading to a significant decrease of Ti-C and increase of Ti-O, resulting in efficient ROS scavenging (Figure 2N).

We conducted the ABTS+• radicals assay (Figure 2F-H, Figure S16) to compare the excellent ROS-scavenging performance of Ti3C2 NSs with the currently reported ROS-scavenging agents, including cerium dioxide (CeO2) 17, 30, 31, molybdenum-based polyoxometalate (POM) 32, transition-metal dichalcogenide (WS2) 33, and gallic acid (GA) 34. After incubation with the same concentration, the characteristic absorption peak intensity of ABTS+• radicals showed no change in CeO2, POM, and WS2 groups, a significant decrease in the GA group, and completely disappeared in the Ti3C2 NSs group (Figure 2F). Also, the color of various treatments revealed similar results (Figure 2G). Quantitative analysis of the ABTS+• scavenging rate further confirmed the comparably higher antioxidant performance of Ti3C2 NSs than CeO2 (~16-fold), POM (~18-fold), WS2 (~27-fold), and GA (~1.6-fold) antioxidative agents (Figure 2H).

Next, we studied the intracellular ROS-scavenging performance of Ti3C2 NSs on human colonic epithelial (HT29) cells, Raw 264.7 macrophage, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (Figure 3A). Ti3C2 NSs exhibited no apparent cytotoxicity to HT29, Raw 264.7 macrophage, and HUVECs cells by the standard methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay even at a high concentration (100 μg/mL) for 12 h (Figure 3B, Figure S17-S18). HT29 internalized Ti3C2 NSs via endocytosis in a time-dependent fashion (Figure S19-20). Subsequently, the protection mechanism of Ti3C2 NSs for H2O2-induced HT29 apoptosis was evaluated. As revealed by the MTT assay, H2O2 treatment could amplify the intracellular oxidative stress and eventually cause HT29 apoptosis (Figure 3C). In contrast, pretreatment of Ti3C2 NSs could significantly relieve oxidative stress and abolish cell apoptosis, indicating that almost all of H2O2 was scavenged by Ti3C2 NSs. Furthermore, calcein AM/propidium iodide (AM/PI) staining of H2O2-treated HT29 showed a red signal indicative of dead cells. However, the red signal significantly decreased upon treatment with Ti3C2 NSs, indicating that Ti3C2 NSs could scavenge H2O2 and block H2O2-induced cell apoptosis (Figure 3E, Figure S21).

Figure 3.

In vitro antioxidant investigation by Ti3C2 NSs. (A) Schematic illustration shows the intracellular ROS scavenging and cell protection by Ti3C2 NSs. (B) Relative viabilities of HT29 cells after incubation with different concentration of Ti3C2 NSs (0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μg/mL). (C) Relative viabilities of HT29 cells with different treatments including Ti3C2 (40 μg/mL), H2O2 (1 or 2 mM), and Ti3C2 plus H2O2. (D) Confocal images of HT29 cells stained with DCFH-DA after various treatments as indicated. (E) Confocal images of HT29 cells stained with Calcein-AM (green, live cells) and propidium iodide (red, dead cells) after treatments. (F) Scheme shows that Ti3C2 NSs could regulate the polarization of macrophages. (G-H) Flow cytometric examination and statistical analysis of the M1-phenotype macrophages in different groups. (I) Immunofluorescence images indicate the M1-type macrophages in different groups. (J) Scheme shows the intracellular ROS scavenging and the Ti3C2 and the macrophages polarization regulating by Ti3C2 NSs. The statistical significance was calculated by two-tailed student's t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001.

Since oxidative stress induced by excessive ROS generation induces lipid peroxidation, protein damage, and DNA breaks, the intracellular ROS-scavenging performance of Ti3C2 NSs was further studied via 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe, which reacts with intracellular ROS and forms green fluorescent DCF. We observed a strong green fluorescence signal in the H2O2-treated HT29 cells compared with untreated or only Ti3C2 NSs-treated cells (Figure 3D, Figure S22). After pretreatment with Ti3C2 NSs, the DCF fluorescence signal remarkably decreased in H2O2-treated HT29 cells, suggesting that most of the intracellular H2O2 was eliminated by Ti3C2 NSs. Thus, Ti3C2 NSs showed high in vitro ROS-scavenging ability and protective effect against the high oxidative-stress-induced cell death.

Besides the intracellular ROS-scavenging evaluation, the regulatory function of Ti3C2 NSs involved in macrophage polarization was investigated using lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated mouse macrophage cells (RAW 264.7) (Figure 3F). In addition to ROS scavenging, the macrophage phenotype plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of many inflammatory diseases. Macrophages in the inflammatory site are primarily of the M1 phenotype and promote inflammation by secreting various inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, down-regulating the M1 phenotype macrophages is a potential method for treating inflammatory diseases 35-37. To examine the capability of Ti3C2 NSs for reprogramming macrophages, LPS-pretreated RAW 264.7 cells with the M1 phenotype were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining with the antibody against CD80, an M1 marker. The strong CD80+ signal of LPS-pretreated RAW 264.7 cells significantly decreased after treatment with Ti3C2 NSs (Figure 3I), demonstrating the effective inhibition of macrophage polarization. Furthermore, the flow cytometric analysis combined with the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) confirmed that Ti3C2 NS treatment could significantly inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory factor interleukin-6 (IL-6) and reduce the proportion of LPS-induced inflammatory macrophages (Figure 3G-H, Figure S23). Thus, Ti3C2 NSs with strong antioxidant properties could efficiently scavenge intracellular ROS and regulate macrophage polarization to treat inflammatory diseases (Figure 3J).

Many positively charged proteins and excessive ROS were frequently observed in the inflamed colon lesions.14 Negatively charged nanoplatforms targeting positively charged proteins and scavenging excess ROS represent an extremely effective treatment for alleviating inflammation. We used negatively charged Ti3C2 NSs to target positively charged colonic lesions. A positively charged film of methanol-activated PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride) membranes was employed to simulate the inflamed colon tissue and evaluate the charge-attracted targeting accumulation of Ti3C2 NSs. After incubation with Ti3C2 NSs, the positively charged film showed black color, indicating that Ti3C2 NSs aggregated on the surface through charge adsorption (Figure 4I). Importantly, Ti3C2 NS concentration on the positively-charged film was 3-fold compared with the neutral film, confirming the effective electrostatic targeting of the negatively-charged Ti3C2 NSs to the inflamed colon.

Figure 4.

In vivo therapeutic effect of Ti3C2 NSs on DSS-induced colitis. (A) The scheme shows the protocol of DSS-induced colitis and the oral administration of Ti3C2 NSs for IBD treatment. (B) Daily body weight changes of mice from different groups as indicated. (C-D) Mice were sacrificed on day 10, and colons were collected, imaged, and their lengths measured. (E) Microscopy images of H&E-stained of longitudinal sections of these colon after different treatments. (F) Confocal images of colon tissue stained by DCFH-DA from various groups. (G) Bio-TEM of colon tissue from these mice after Ti3C2 NSs oral administration (Green, DCF; WGA, Wheat Germ Agglutini, Red; DAPI, blue). (H) The Ti levels in the colon tissue determined by ICP-OES at different days. (I) The Ti contents in the neutral and positively charged film after incubation with Ti3C2 solutions (The insert is the corresponding photograph). The statistical significance was calculated by two-tailed student's t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001.

The efficient ROS-scavenging property, excellent stability in SGF, and the inflamed colon targeting capability prompted us to investigate the in vivo therapeutic efficacy of Ti3C2 NSs for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) via oral administration. Mice were given 5% dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS) supplemented in the drinking water for 5 consecutive days to establish an IBD model, and Ti3C2 NSs (45 mg/kg) were orally administered for one week according to the previous dose climbing experiments (Figure 4A, Figure S24). The body weight changes were monitored daily to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy (Figure 4B). Compared with their initial weight, healthy mice showed an increased body weight; however, DSS-induced colitis mice showed ~15.4% decreased body weight on day 10, indicating the successful establishment of the IBD model. After the oral administration of Ti3C2 NSs, the body weight of the colitis mice slightly increased, demonstrating the positive therapeutic outcome of Ti3C2 NSs for IBD. Also, compared with the clinical drug 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), Ti3C2 NSs exhibited a satisfactory therapeutic effect after oral administration (Figure S25). We also examined pathological colon sections and measured changes in the colon length to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of the Ti3C2 NSs. DSS-induced colitis shortened the colon length by ~25% while Ti3C2 NSs treatment exhibited a protective effect and completely inhibited the shortening of the colon length (Figure 4C-D). Besides, the severely collapsed structure of colonic tissue, observed in the DSS-induced colitis mice (Figure 4E), significantly improved in histological appearance and regular colonic morphology was observed, demonstrating a great therapeutic outcome for IBD by Ti3C2 NSs treatment.

To understand the therapeutic mechanism of the in vivo IBD therapy and verify ROS elimination by Ti3C2 NSs, DCFH-DA staining of colon tissue slices was carried out for evaluating the ROS level in the colon after various treatments. The colon from DSS-induced colitis mice showed strong green fluorescence that sharply decreased to the normal level following treatment with Ti3C2 NSs (Figure 4F, Figure S26). Ti3C2 NSs aggregation in the colon site was observed by Bio-TEM imaging (Figure 4G), and Ti3C2 NSs concentration in the colon tissue was maintained at a high level during the therapeutic period (Figure 4H). Furthermore, the colon Ti3C2 NSs accumulation in colitis mice was higher than in normal mice, confirming that the negatively-charged Ti3C2 NSs could specifically adsorb to positively charged inflamed colonic tissues via electrostatic interactions (Figure S27).

Next, variations in the in vivo colon microenvironment of IBD mice after the oral administration of Ti3C2 NSs were investigated. It is well established that the immune response imbalance of the colon causes inflammation and even colitis, and regulating the phenotype of macrophages could alleviate colitis symptoms 37. Therefore, we evaluated the regulation of M1 and M2 macrophage phenotypes in colon tissues following Ti3C2 NS treatment. Compared with the control group, the total macrophages in the colitis and Ti3C2 NS-treated colitis groups remained almost unchanged (Figure 5B). However, significantly increased M1-phenotype and decreased M2-phenotype macrophages were observed in DSS-induced colitis while the changes in macrophage phenotypes were reversed by the Ti3C2 NSs treatment (Figure 5A, 5C-D). Furthermore, the increased ratio of M2 to M1 macrophage infiltration in the colon tissue remarkably alleviated colitis symptoms (Figure 5E). These results were also confirmed by immunofluorescence staining (Figure 5F-G). Similarly, the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β) was down-regulated, and the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10) was up-regulated in the Ti3C2 NS-treated group (Figure 5H-I). These results indicated that oral administration of Ti3C2 NSs could efficiently alleviate colitis symptoms by reversing the polarization of the macrophages from the M1 to M2 phenotype and regulating the secretion of various cytokines inside the colon (Figure 5J).

Figure 5.

The colon immune microenvironment variation induced by Ti3C2 NSs after oral administration. (A) Representative flow cytometry analysis results of M1-phenotype macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+CD80+) and M2-phenotype macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+CD206+) within these colons after different treatments. (B-E) The quantitative analysis results of total macrophages (B), M1-phenotype macrophages (C), M2-phenotype macrophages (D), and M2/M1 (E). (F) Confocal images of colon tissues stained by staining CD80 (M1 phenotype macrophage marker) and CD206 (M2 phenotype macrophage marker) from different groups. (G) The statistical analysis of these results in F. (H-I) The secretion level of IL-1β and IL-10 within the colon tissues from various groups. (J) Schematic illustration shows that Ti3C2 NSs could regulate the colon immune microenvironment to treat IBD. The statistical significance was calculated by two-tailed student's t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001.

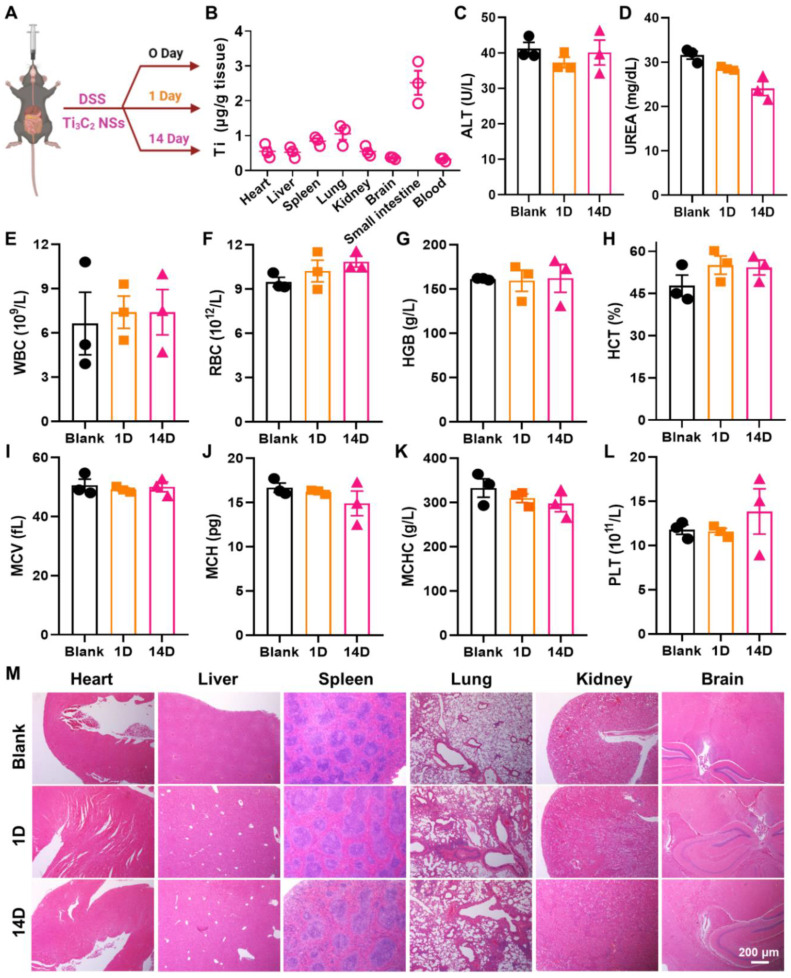

Biosafety is a critical issue for the biological application of nanomaterials. Therefore, the biodistribution of Ti3C2 NSs in major organs of mice was investigated (Figure 6A). Mice were orally administered Ti3C2 NSs for 7 consecutive days, and the Ti element level in major organs was measured by ICP-OES following treatment with Ti3C2 NSs. Notably, apart from the small intestine, no noticeable distribution was observed in other major organs (<1.25 μg/g tissue) (Figure 6B), indicating negligible toxicity of Ti3C2 NSs. The potential toxicity of Ti3C2 NSs was further evaluated by blood chemistry, complete blood panel analysis, and histology examination. The blood chemistry parameters and complete blood panel analysis in the orally administered Ti3C2 NSs group showed no significant difference compared with the control groups (Figure 6C-L). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and histology analysis also showed no apparent tissue damage and adverse effect in the Ti3C2 NS group (Figure 6M). These data showed no significant side effects in mice, indicating a promising potential of orally administered Ti3C2 NSs for in vivo biomedical applications in the future.

Figure 6.

In vivo biosafety of Ti3C2 NSs after oral administration. (A) Scheme of the biosafety assessment of Ti3C2 NSs after oral administration. (B) Biodistribution of Ti3C2 NSs in mice organs at 7 day. (C-D) Blood biochemistry analysis results of these Ti3C2-treated mice (alanine aminotransferase (ALT, C) and urea (D)). (E-L) Complete blood panel analysis results of above mice (white blood cells (WBC, E), red blood cells (RBC, F), hemoglobin (HGB, G), hematocrit (HCT, H), mean corpuscular volume (MCV, I), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH, J), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC, K), and platelet (PLT, L)). (M) Microscopy images of H&E-stained mice major organs at different treatment days.

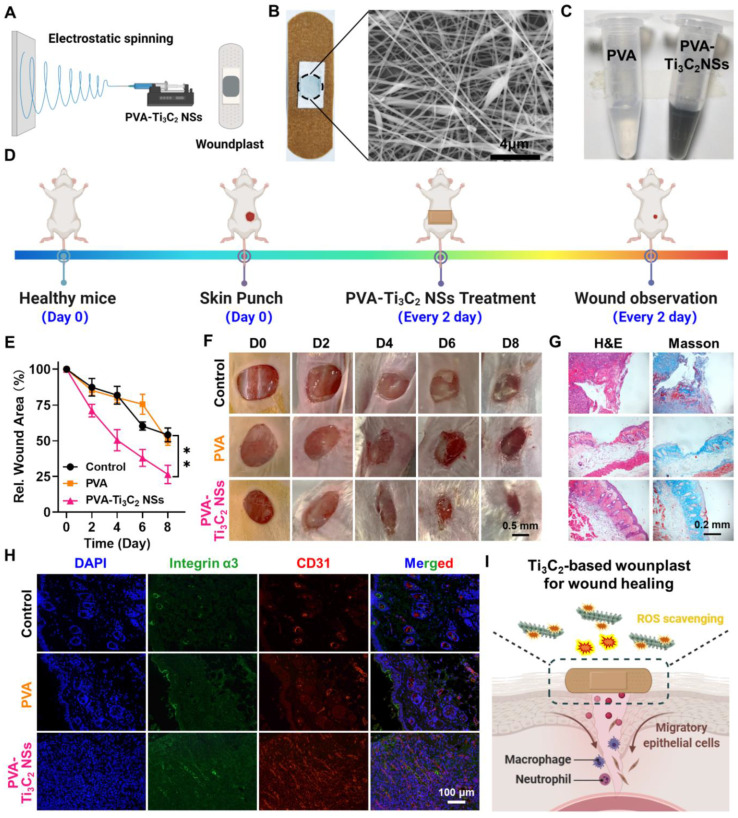

The excellent in vivo ROS-scavenging performance of Ti3C2 NSs prompted us to investigate its potential application in wound healing. Skin wounds are a frequent occurrence in our daily lives, and the high oxidative stress within the impaired wound largely impedes the wound healing process. Given the role of ROS in wound healing and considering the excellent ROS-scavenging ability of Ti3C2 NSs, we employed electrospinning technology to prepare Ti3C2 NS-containing polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers and obtained Ti3C2-based woundplasts (Figure 7A)38. Incorporation of Ti3C2 NSs into PVA spinning solution yielded Ti3C2-PVA fibers with black color and uniform Ti3C2 distribution on their surface (Figure 7B, Figure S28). The Ti3C2-PVA fibers could be easily dissolved in PBS, enabling efficient ROS scavenging by the released Ti3C2 NSs (Figure 7C, Figure S29).

Figure 7.

Skin wound healing on mice treated by Ti3C2-based woundplast. (A) Schematic illustration shows the preparation process of Ti3C2 NSs-based woundplast. (B) A photograph and its SEM image of our woundplast. (C) A photograph of the solutions of PVA or PVA-Ti3C2 fibers dissolved into PBS buffer. (D) Scheme depicts the skin wound healing process of mice treated with Ti3C2 NSs-based woundplast. (E) Relative wound areas after different treatments. (F) The images of skin wounds after treatments as indicated. (G) Micrographs of H&E- and Masson- stained wounds from various group in E. (H) The immunofluorescence images of CD31- and integrin α3- stained wound sections. (I) Scheme reveals the wound healing mechanism after treatment with Ti3C2 NSs-based woundplast. The statistical significance was calculated by two-tailed student's t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001.

Next, we assessed the effect of Ti3C2-PVA fibers on wound healing by randomly dividing the wound-bearing mice into three groups: (1) Control; (2) PVA-based woundplasts; (3) Ti3C2-PVA-based woundplasts (4 μg Ti3C2 NSs per woundplast). These woundplasts were applied on the wounds four times on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 (Figure 7D). The wound areas were monitored every two days in the three groups. Significantly, the wounds in the Ti3C2-based woundplast-treated group healed quickly and achieved ~73.5% closure on day 8 compared with the control and PVA-treated groups. These results demonstrated effective ROS scavenging by Ti3C2 NSs to accelerate wound healing (Figure 7E-F). H&E and Masson staining showed that the regenerated wound tissue in the Ti3C2-based woundplast-treated group was much thicker, and the collagen synthesis was also better than in the control groups (Figure 7G). These data confirmed the significant ability of the Ti3C2-based woundplast in skin wound healing.

Finally, the skin wounds were examined by immunofluorescence staining using CD31 and integrin α3 (markers of new blood vessels) and collagen. We found increased CD31 and integrin α3 expression in the Ti3C2-based woundplast group compared with the control groups, indicative of extensive neovascularization in the wounds (Figure 7H). The results demonstrated that the Ti3C2-based woundplast could efficiently eliminate excess ROS to increase CD31 and the integrin α3 around the wound, promoting skin wound healing and functional vessel formation (Figure 7I).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the novel antioxidant Ti3C2 NSs were successfully constructed for specifically targeting to inflammatory colon and effective ROS scavenging via oral administration. Ti3C2 NSs synthesized via a two-step exfoliation method exhibited excellent long-term stability in acidic SGF. The as-synthesized Ti3C2 NSs exhibited broad-spectrum ROS scavenging properties that could eliminate excess ROS against oxidative stress-induced cell apoptosis. After oral administration, the negatively-charged Ti3C2 NSs could specifically target the positively-charged inflamed colon lesions via electrostatic interactions and achieve efficient therapy of DSS-induced colitis. The systematic mechanism demonstrated that Ti3C2 NSs could significantly inhibit inflammation by decreasing the level of ROS and the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, increasing the infiltration of M2-phenotype macrophages and the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, therefore efficiently alleviating the colitis symptoms. Besides, owning to its ROS scavenging ability, Ti3C2-based woundplast were presented for promoting skin wound healing and functional vessel formation. Overall, the constructed Ti3C2 NSs with great biosafety and robust ROS eliminating ability could represent a promising orally administered antioxidant for treating IBD or other related inflammatory diseases of the digestive tract.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods and figures.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20254, 52072253, 21927803, 52032008), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021TQ0229), Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou Nano Science and Technology, Suzhou Key Laboratory of Nanotechnology and Biomedicine, a Jiangsu Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (BK20211544), the 111 Project, and Joint International Research Laboratory of Carbon-Based Functional Materials and Devices, a Jiangsu Social Development Project (BE2019658), and Suzhou Key Laboratory of Nanotechnology and Biomedicine. L. Cheng was supported by the Tang Scholarship of Soochow University.

References

- 1.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn's disease. The Lancet. 2012;380:1590–605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hindryckx P, Jairath V, D'Haens G. Acute severe ulcerative colitis: from pathophysiology to clinical management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:654–64. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Souza HSP, Fiocchi C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:13–27. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein CN, Fried M, Krabshuis JH, Cohen H, Eliakim R, Fedail S. et al. World gastroenterology organization practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of IBD in 2010. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:112–24. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoivik ML, Moum B, Solberg IC, Cvancarova M, Hoie O, Vatn MH. et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis after a 10-year disease course: results from the IBSEN study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1540–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sela-Passwell N, Kikkeri R, Dym O, Rozenberg H, Margalit R, Arad-Yellin R. et al. Antibodies targeting the catalytic zinc complex of activated matrix metalloproteinases show therapeutic potential. Nat Med. 2012;18:143–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson DS, Dalmasso G, Wang L, Sitaraman SV, Merlin D, Murthy N. Orally delivered thioketal nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α-siRNA target inflammation and inhibit gene expression in the intestines. Nat Mater. 2010;9:923–8. doi: 10.1038/nmat2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickson I. Ustekinumab therapy for Crohn's disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:4. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lautenschläger C, Schmidt C, Fischer D, Stallmach A. Drug delivery strategies in the therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2014;71:58–76. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung CH, Jung W, Keum H, Kim TW, Jon S. Nanoparticles derived from the natural antioxidant rosmarinic acid ameliorate acute inflammatory bowel disease. ACS Nano. 2020;14:6887–96. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c01018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S, Ermann J, Succi Marc D, Zhou A, Hamilton Matthew J, Cao B. et al. An inflammation-targeting hydrogel for local drug delivery in inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:300ra128–300ra128. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:504–11. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang LJ, Mao XT, Li YY, Liu DD, Fan KQ, Liu RB. et al. Multiomics analyses reveal a critical role of selenium in controlling T cell differentiation in Crohn's disease. Immunity. 2021;54:1728–44.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canny G, Levy O, Furuta GT, Narravula-Alipati S, Sisson RB, Serhan CN. et al. Lipid mediator-induced expression of bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI) in human mucosal epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:3902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052533799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Langer R, Traverso G. Nanoparticulate drug delivery systems targeting inflammation for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Nano Today. 2017;16:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han W, Mercenier A, Ait-Belgnaoui A, Pavan S, Lamine F, van Swam II. et al. Improvement of an experimental colitis in rats by lactic acid bacteria producing superoxide dismutase. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:1044–52. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000235101.09231.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao S, Li Y, Liu Q, Li S, Cheng Y, Cheng C. et al. An Orally Administered CeO2@montmorillonite nanozyme targets inflammation for inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30:2004692. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vong LB, Tomita T, Yoshitomi T, Matsui H, Nagasaki Y. An orally administered redox nanoparticle that accumulates in the colonic mucosa and reduces colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1027–36.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vong LB, Yoshitomi T, Matsui H, Nagasaki Y. Development of an oral nanotherapeutics using redox nanoparticles for treatment of colitis-associated colon cancer. Biomaterials. 2015;55:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q, Tao H, Lin Y, Hu Y, An H, Zhang D. et al. A superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic nanomedicine for targeted therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Biomaterials. 2016;105:206–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng W, Han X, Hu H, Chang M, Ding L, Xiang H. et al. 2D vanadium carbide MXenzyme to alleviate ROS-mediated inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2203. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22278-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu B, Wang A, Cheng L, Chen R, Shi H, Song B. et al. Ex vivo and in vivo fluorescence detection and imaging of adenosine triphosphate. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:187. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-00930-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao X, Wang LY, Li JM, Peng LM, Tang CY, Zha XJ. et al. Redox-mediated artificial non-enzymatic antioxidant MXene nanoplatforms for acute kidney injury alleviation. Adv Sci. 2021;8:2101498. doi: 10.1002/advs.202101498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naguib M, Kurtoglu M, Presser V, Lu J, Niu J, Heon M. et al. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv Mater. 2011;23:4248–53. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szuplewska A, Rozmysłowska-Wojciechowska A, Poźniak S, Wojciechowski T, Birowska M, Popielski M. et al. Multilayered stable 2D nano-sheets of Ti2NTx MXene: synthesis, characterization, and anticancer activity. J Nanobiotechnol. 2019;17:114. doi: 10.1186/s12951-019-0545-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang W, Dong Z, Zhang R, Yi X, Yang K, Jin M. et al. Multifunctional two-dimensional core-shell MXene@gold nanocomposites for enhanced photo-radio combined therapy in the second biological window. ACS Nano. 2019;13:284–94. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b05982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Low J, Zhang L, Tong T, Shen B, Yu J. TiO2/MXene Ti3C2 composite with excellent photocatalytic CO2 reduction activity. J Catal. 2018;361:255–66. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lotfi R, Naguib M, Yilmaz DE, Nanda J, van Duin ACT. A comparative study on the oxidation of two-dimensional Ti3C2 MXene structures in different environments. J Mater Chem A. 2018;6:12733–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Y, Wang S, Yang J, Han B, Nie R, Wang J. et al. In-situ grown nanocrystal TiO2 on 2D Ti3C2 nanosheets for artificial photosynthesis of chemical fuels. Nano Energy. 2018;51:442–50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weng Q, Sun H, Fang C, Xia F, Liao H, Lee J. et al. Catalytic activity tunable ceria nanoparticles prevent chemotherapy-induced acute kidney injury without interference with chemotherapeutics. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1436. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21714-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang T, Li Y, Cornel EJ, Li C, Du J. Combined antioxidant-antibiotic treatment for effectively healing infected diabetic wounds based on polymer vesicles. ACS Nano. 2021;15:9027–38. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c02102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ni D, Jiang D, Kutyreff CJ, Lai J, Yan Y, Barnhart TE. et al. Molybdenum-based nanoclusters act as antioxidants and ameliorate acute kidney injury in mice. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5421. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07890-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yim D, Lee D-E, So Y, Choi C, Son W, Jang K. et al. Sustainable nanosheet antioxidants for sepsis therapy via scavenging intracellular reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. ACS Nano. 2020;14:10324–36. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dehghani MA, Shakiba Maram N, Moghimipour E, Khorsandi L, Atefi khah M, Mahdavinia M. Protective effect of gallic acid and gallic acid-loaded Eudragit-RS 100 nanoparticles on cisplatin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation in rat kidney. BBA-MOL Basis Dis. 2020;1866:165911. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee B-C, Lee Jin Y, Kim J, Yoo Je M, Kang I, Kim J-J, Graphene quantum dots as anti-inflammatory therapy for colitis. Sci Adv. 6: eaaz2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Shen Q, Huang Z, Yao J, Jin Y. Extracellular vesicles-mediated interaction within intestinal microenvironment in inflammatory bowel disease. J Adv Res. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.07.002. DOI: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee Y, Sugihara K, Gillilland MG, Jon S, Kamada N, Moon JJ. Hyaluronic acid-bilirubin nanomedicine for targeted modulation of dysregulated intestinal barrier, microbiome and immune responses in colitis. Nat Mat. 2020;19:118–26. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0462-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Müller GFJ, Stürzel M, Mülhaupt R. Core/shell and hollow ultra gigh molecular weight polyethylene nanofibers and nanoporous polyethylene prepared by mesoscopic shape replication catalysis. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:2860–4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary methods and figures.