Abstract

Objective

We estimated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination rates in the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) population and investigated reasons for vaccine hesitancy.

Methods

In Spring 2021, we surveyed the NARCOMS participants about COVID-19 vaccinations. Participants reported whether they had received any COVID-19 vaccination; if not, they reported why not. They also reported whether they had received influenza vaccination. Using multivariable logistic regression, we assessed participant characteristics associated with uptake of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines.

Results

Of 4955 eligible respondents, 3998 (80.7%) were females with a mean (SD) age of 64.0 (9.7) years. Overall, 4165 (84.1%) reported that they had received a COVID-19 vaccine, most often Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, and 3723 (75.4%) received a seasonal influenza vaccine. Reasons for not getting the COVID-19 vaccine included possible adverse effects (47.73%), possible lack of efficacy (13.7%), and lack of perceived need (17.1%). Factors associated with receiving the COVID-19 vaccine included receipt of influenza vaccine, older age, higher socioeconomic status, any leisure physical activity, and use of disease-modifying therapy.

Conclusion

In this older cohort of people with multiple sclerosis, COVID-19 vaccine uptake was high, exceeding uptake of seasonal influenza vaccine. Concerns regarding safety, efficacy, and lack of perceived risk were associated with not obtaining the COVID-19 vaccine.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, vaccination, coronavirus disease 2019

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is associated with an increased risk of infection and infection-related hospitalizations, including viral infections.1–3 Although people with MS do not appear to have a heightened risk of infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (hereinafter coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] infection) compared to people without MS, those with severe disability are more likely to require hospitalization. 4 Vaccinations are an important means of preventing or reducing the severity of COVID-19 infection. However, the novelty of COVID-19 vaccinations and the complexity of messaging around vaccinations have raised many questions for people with MS, related to safety in general and specifically related to their MS, and effectiveness in the context of the usage of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs).

Prior work involving participants in the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) registry showed that uptake of influenza vaccination ranged from 59.1% to 79.9% depending on the age of the participant, thus lower than the recommended uptake of 100%. 5 Factors associated with the decision not to obtain an influenza vaccination included concerns regarding adverse effects including that the vaccine might worsen their MS and personal preference. Little is known about the factors associated with the uptake of COVID-19 vaccine. 6 One survey of 237 persons with MS found that 22.2% were vaccine hesitant but the response rate was approximately 18%, raising concerns about selection bias. We aimed to determine the uptake of COVID-19 vaccine in the NARCOMS population, and to investigate the reasons for not obtaining the vaccine.

Methods

Study population

The source population for this study was all active participants in the NARCOMS Registry, a self-report registry for persons with MS. 7 Participants report sociodemographic and clinical information at enrollment and update this information semi-annually. Participants completed their surveys on paper or online. Participants allow the usage of their de-identified information for research purposes. The spring 2021 survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of UT Southwestern.

Participant characteristics

We obtained participant characteristics from the enrollment and spring 2021 questionnaires. The enrollment questionnaire provided information regarding birth date, sex, race, level of education, region of residence, and ages at MS symptom onset and diagnosis. All other characteristics were drawn from the spring 2021 questionnaire. This information included marital status, annual household income, health behaviors, and disability status. As reported previously, we categorized race as White or non-White, and education level as high school/general education diploma, and post-secondary (Associate's Degree, Bachelor's Degree, Post-graduate education, and Technical degree).

Participants reported annual household income as ≤$50,000, $50,001–$100,000, >$100,000, and “I do not wish to answer.” Marital status was categorized as single (never married, divorced, widowed, or separated) and married (married or co-habiting). Using a question from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, participants reported their current smoking status as “no, yes Some days, or yes every day.” We collapsed these responses to yes/no. 8 They reported whether they had participated in any physical activity or exercise during the past month (yes/no). Participants also reported alcohol intake using one question from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C), 9 modified to use a recall period of 6 months rather than 12 months. Response options included never, monthly or less, two to four times a month, two to three times a week, or four or more times a week.

Disease duration from symptom onset was categorized (≤10, 11–19, ≥20 years). Disability status was reported using patient-determined disease steps (PDDS). PDDS is a single-item measure with response options ranging from 0 (normal) to 8 (bedridden) and is highly correlated with a physician-scored Expanded Disability Status Scale score. 10 We categorized PDDS as mild (0–1), moderate (2–4), and severe (5–8). 11 Based on items from SymptoMScreen we classified participants as having any depression (yes/no) or anxiety (yes/no) symptoms. 12 Participants reported use of DMT in the last 6 months which were as none or any.

COVID-19 infection and immunization

We asked participants several questions about COVID-19 immunization. Participants reported whether any of their health care providers had talked to them about COVID-19 vaccine (yes, no, don’t know). If they answered in the affirmative they reported which provider had talked to them including neurologist, primary care provider and other (specify). They also indicated whether their provider had recommended: (a) to get the COVID-19 vaccine; (b) to never get the COVID-19 vaccine; (c) to wait for more information to determine if you should get the COVID-19 vaccine; and (d) the recommendations were different from different providers.

Participants reported whether they had received a COVID-19 vaccine (yes, no, don’t know) and specifically which vaccine (Moderna, Pfizer-Biontech, Other), and whether they had received one or two doses. Unvaccinated participants reported their reasons as (a) vaccine not available to me (yet); (b) my doctor advised against it; (c) allergic reaction to vaccines; (d) concerned about side effects from the vaccine; (e) did not think I needed it; (f) allergy to polyethylene glycol; (g) concerned vaccine does not work; (h) concerned that vaccine would worsen MS; and (i) other, consistent with our prior work. 13 Influenza vaccination is routinely recommended for people with MS, therefore we used it as a comparator, and participants also reported whether or not they had received the influenza vaccination.

Statistical analysis

For consistency with our prior work, 13 we included individuals who reported a confirmed diagnosis of MS with an age of symptom onset ≥16 years, complete information regarding sex and date of birth; and were residing in the United States to limit heterogeneity related to differences in vaccination policy and availability. We excluded participants who did not respond to any of the questions regarding both COVID-19 and influenza vaccination as these were the key study outcomes. Missing responses were not imputed.

First, we summarized participant characteristics using descriptive statistics including means (standard deviations [SD]), median (interquartile range (IQR)), and frequency (percent). We summarized uptake of the COVID-19 and influenza vaccines, and physician recommendations for vaccination overall and stratified by sex, age (18–34, 35–50, 51–64, and ≥65 years), disability status (mild, moderate, severe), and DMT use (no as reference). We summarized the reasons for not receiving the COVID-19 vaccines.

Last, we used logistic regression to examine factors associated with (a) the uptake or not of the COVID-19 vaccine, and (b) uptake or not of the influenza vaccine. Consistent with our prior work, these models included sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and health behaviors. 13 Sociodemographic characteristics included sex (female as the reference group), race (White as reference), age (≥65 years as reference), education level (high school as reference), and income (<$50,000 as reference). Clinical characteristics included disease duration (<10 years as reference), disability status (mild as reference), DMT use, depression (no as reference), and anxiety (no as reference). Health behaviors included current smoking status (no as reference), alcohol intake (never as reference), and physical activity (inactive as reference). We tested for interactions between DMT use and age, education level and disability status using cross-product terms. We used standard methods to assess model assumptions, and assessed model fit using the Hosmer Lemeshow Goodness of Fit Statistic. 14 We report the c-statistic for each model. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS V9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Data availability

The data sets generated and analyzed during this study are held by the NARCOMS registry (narcoms.org).

Results

The Spring 2021 survey was distributed to 8516 participants, of whom 5760 (67.6%) responded. As compared to responders, non-responders were more likely to report non-White race, had a slightly higher level of education, and more severe disability (Supplemental Table e1). After applying exclusion criteria, 4955 (86%) participants constituted the final sample. Most respondents were females with some post-secondary education (Table 1). Over half of the respondents were aged 65 years and older. Based on the PDDS, respondents were almost evenly distributed across mild, moderate, and severe disability categories. Respondents with missing data did not differ from those without missing data (Supplemental Table e2).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristics | Responders |

|---|---|

| N | 4955 |

| Age at time of Spring 2021 survey (years)a, mean (SD) | 64 (9.7) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | |

| 18–34 | 14 (0.3) |

| 35–50 | 419 (8.5) |

| 51–64 | 1881 (38.0) |

| ≥65 | 2641 (53.3) |

| Femaleb, n (%) | 3998 (80.7) |

| White racec, n (%) | 4367 (88.2) |

| Education at enrollmentd, n (%) | |

| High school/GED | 1232 (25.9) |

| Post-secondary | 3532 (74.1) |

| Annual household income at enrollmente, n (%) | |

| Less than $50,000 | 1555 (31.7) |

| $50,001–$100,000 | 1202 (24.5) |

| Over $100,000 | 1032 (21.1) |

| I do not wish to answer | 1114 (22.7) |

| Age at MS symptom onset (years)f, mean (SD) | 32 (9.6) |

| Age at MS diagnosis (years)g, mean (SD) | 39 (9.7) |

| Disease Duration (years)h, mean (SD) | 32 (11.2) |

| PDDSi, median (IQR) | 4 (5) |

| PDDS | |

| Mild (0–1) | 1469 (30.1) |

| Moderate (2–4) | 1557 (32.0) |

| Severe (5–8) | 1848 (37.9) |

| Any disease-modifying therapy in last 6 monthsj, n(%) | 2601 (54.9) |

| Current smoking, n(%) | 315 (6.4) |

| Leisure Activityk, n(%) | 2912 (59.1) |

| Alcohol intakel, n(%) | |

| Never | 1807 (36.6) |

| Monthly or less | 1224 (24.8) |

| 2–4 times a month | 771 (15.6) |

| 2–3 times a week | 543 (11.0) |

| ≥4 times a week | 597 (12.1) |

| Anxietym, n(%) | 911 (18.9) |

| Depressionn, n(%) | 1747 (36.2) |

IQR: interquartile range; GED: general education diploma; PDDS: patient determined disease step.

0 missing.

0 missing.

1 missing.

191 missing.

52 missing.

62 missing.

20 missing.

65 missing.

81 missing.

220 missing.

31 missing.

13 missing.

146 missing.

130 missing.

Vaccination uptake

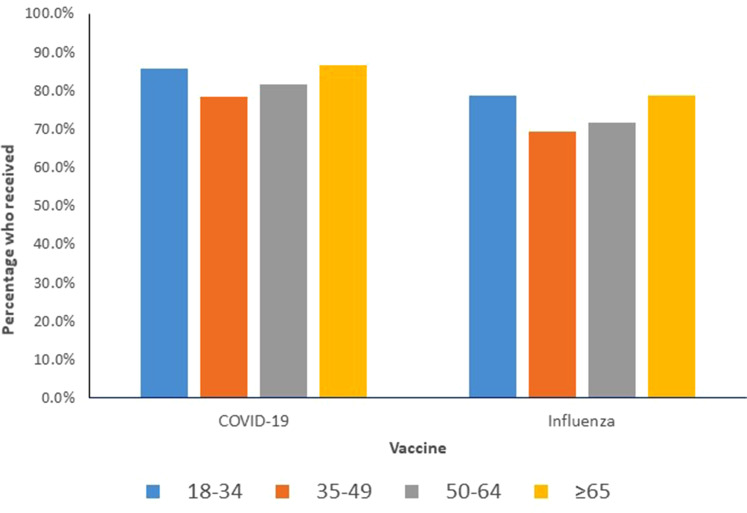

Overall, 4165 (84.06%) respondents received a COVID-19 vaccine with the most common vaccine being Pfizer-BioNtech, followed by Moderna. Nearly 10% more respondents received a COVID-19 vaccine than influenza vaccine. Table 2 shows the prevalence of uptake of each type of vaccine, stratified according to age, sex, and disability status. Supplemental Table e3 presents the characteristics of the participants who received each vaccine. The uptake of COVID-19 and influenza vaccine did not vary meaningfully by age group (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Prevalence of COVID-19 and influenza vaccination overall, and stratified by demographic characteristics and disability (N = 4955 for COVID-19 vaccinations, N = 4934 for influenza).

| Characteristics | Moderna | Pfizer-BioNTech | Other | Any COVID-19 vaccine | Influenza |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n(%); binomial 95% CI | 1797 (36.27); (34.93–37.61) | 2169 (43.77); (42.39–45.16) | 207 (4.18); (3.62–4.73) | 4165 (84.06); (83.04–85.08) | 3723 (75.44); (74.24–76.64) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | |||||

| 18–34 | 5 (35.71) | 7 (50.0) | 0 (0.00) | 12 (85.71) | 11 (78.57) |

| 35–50 | 120 (28.64) | 188 (44.87) | 22 (5.25) | 328 (78.28) | 290 (69.21) |

| 51–64 | 601 (31.95) | 842 (44.76) | 94 (5.00) | 1535 (81.61) | 1346 (71.71) |

| ≥65 | 1071 (40.55) | 1132 (42.86) | 91 (3.45) | 2290 (86.71) | 2076 (79.09) |

| Female, n (%) | 1439 (35.99) | 1753 (43.85) | 174 (4.35) | 3361 (84.07) | 2998 (75.21) |

| PDDS | |||||

| Mild (0–1) | 533 (36.28) | 680 (46.29) | 52 (3.54) | 1263 (85.98) | 1128 (77.10) |

| Moderate (2–4) | 547 (35.13) | 718 (46.11) | 62 (3.98) | 1324 (85.04) | 1190 (76.58) |

| Severe (5–8) | 690 (37.34) | 732 (39.61) | 86 (4.65) | 1505 (81.44) | 1342 (73.05) |

PDDS: Patient Determined Disease Steps; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants vaccinated against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine and influenza, stratified by age group.

Respondents spoke to their primary care providers (n = 2197, 44.34%) more often than to their neurologists (n = 1990, 38.35%) about COVID-19 vaccine. Among 3273 respondents who reported what their providers recommended with respect to COVID-19 vaccination, 92.82% reported that they were advised to get the COVID-19 vaccine. A minority reported that they were advised to wait for more information (4.12%) or to never get the vaccine (0.58%), whereas 2.47% reported receiving conflicting recommendations.

Of the respondents who did not receive the COVID-19 vaccine, 700 reported the reasons for that outcome. The most common reason was concern about the adverse effects of the vaccine (Table 3). Concerns about lack of effectiveness, allergy, and access were also reported.

Table 3.

Reasons for not receiving a COVID-19 vaccine (n = 700).

| Reason | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Concerned about side (adverse) effects from the vaccine | 332 (47.43) |

| Did not think I needed it | 120 (17.14) |

| Concerned vaccine does not work | 96 (13.71) |

| Vaccine not available to me yet | 72 (10.29) |

| Allergic reaction to vaccines | 57 (8.14) |

| My doctor advised against it | 49 (7.00) |

| Allergy to PEG | 9 (1.29) |

| Other (specify) | 279 (39.86) |

| Mobility issues make it hard to leave home | 44 (6.29) |

| My family members/friends don't support me getting the vaccine | 31 (4.43) |

| Don't know | 18 (2.57) |

| I can't arrange or afford transportation to a vaccination site | 12 (1.71) |

| I can't take the time to get vaccinated because of work or family responsibilities | 4 (0.57) |

| I can't afford the cost of the vaccine | 2 (0.29) |

PEG: polyethylene glycol; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

Factors associated with receiving vaccination

On univariate logistic regression analysis, demographic factors, clinical characteristics, and health behaviors were associated with uptake of COVID-19 vaccine (Table 4). Respondents aged 18–64 had lower odds of vaccination than those aged 65 years or older. Being a smoker and having severe, rather than mild, disability was also associated with reduced odds of vaccination. In contrast, higher versus lower annual household incomes, higher levels of education, any leisure activity, and any alcohol intake were associated with increased odds of vaccination. On multivariable analysis (Table 4), the findings were largely similar with two notable exceptions. First, disability was no longer associated with vaccine uptake. Second, using a DMT was associated with increased odds of vaccine uptake. We did not observe any interactions between DMT use, age, education level or disability status on vaccine uptake. When we added receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine into the regression model, findings were largely similar except that use of any DMT, and leisure activity were no longer associated with receipt of COVID-19 vaccine.

Table 4.

Logistic regression: odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for the association between participant characteristics and receipt of vaccine.

| Characteristics | Covid-19 vaccine (N = 4230) | Influenza (N = 3723) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Adjustedb | Unadjusted | Adjustedc | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Male | 1.00 (0.82–1.22) | 0.94 (0.74–1.18) | 0.91 (0.71–1.17) | 1.07 (0.90–1.26) | 1.01 (0.83–1.22) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Non-White | 1.06 (0.83–1.36) | 1.14 (0.87–1.51) | 1.26 (0.93–1.69) | 0.86 (0.71–1.05) | 0.87 (0.70–1.09) |

| Education at enrollment | |||||

| High school/GED | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Post-secondary | 2.00 (1.68–2.37) | 1.67 (1.38–2.03) | 1.67 (1.36–2.06) | 1.44 (1.24–1.66) | 1.16 (0.98–1.37) |

| Annual household income | |||||

| <$50,000 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| $50,001–$100,000 | 1.66 (1.34–2.06) | 1.58 (1.24–2.03) | 1.47 (1.13–1.91) | 1.45 (1.22–1.73) | 1.37 (1.12–1.68) |

| Over $100,000 | 2.19 (1.72–2.78) | 2.04 (1.53–2.72) | 1.73 (1.28–2.35) | 1.88 (1.55–2.28) | 1.77 (1.41–2.23) |

| I do not wish to answer | 1.30 (1.06–1.60) | 1.21 (0.96–1.53) | 1.19 (0.93–1.53) | 1.21 (1.02–1.44) | 1.09 (0.90–1.33) |

| Disease duration (years) | |||||

| ≤10 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 11–19 | 1.56 (0.82–2.96) | 1.43 (0.64–3.24) | 1.70 (0.71–4.07) | 1.12 (0.61–2.05) | 0.88 (0.39–1.95) |

| ≥20 | 1.83 (1.00–3.35) | 1.49 (0.68–3.28) | 1.79 (0.77–4.16) | 1.13 (0.63–2.01) | 0.79 (0.36–1.73) |

| PDDS | |||||

| Mild (0–1) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Moderate (2–4) | 0.92 (0.74–1.13) | 0.97 (0.77–1.24) | 0.97 (0.75–1.25) | 0.97 (0.82–1.15) | 1.04 (0.86–1.27) |

| Severe (5–8) | 0.79 (0.65–0.96) | 0.93 (0.72–1.19) | 0.94 (0.72–1.23) | 0.81 (0.69–0.95) | 0.97 (0.79–1.19) |

| Any DMT in last 6 months | 1.17 (0.99–1.37) | 1.34 (1.11–1.61) | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) | - | - |

| Current smoking | 0.65 (0.49–0.86) | 0.97 (0.69–1.38) | 1.11 (0.77–1.61) | 0.59 (0.46–0.75) | 0.69 (0.52–0.92) |

| Leisure activity | 1.44 (1.23–1.69) | 1.25 (1.03–1.52) | 1.14 (0.93–1.41) | 1.42 (1.24–1.61) | 1.29 (1.09–1.51) |

| Alcohol intake | |||||

| Never | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2–3 times per week | 1.59 (1.20–2.11) | 1.39 (1.00–1.92) | 1.30 (0.92–1.83) | 1.40 (1.12–1.76) | 1.28 (0.99–1.66) |

| 2–4 times per month | 1.49 (1.17–1.91) | 1.34 (1.01–1.77) | 1.26 (0.93–1.69) | 1.31 (1.08–1.60) | 1.24 (0.99–1.56) |

| 4 or more times per week | 2.09 (1.55–2.81) | 1.72 (1.23–2.39) | 1.58 (1.11–2.25) | 1.72 (1.37–2.17) | 1.49 (1.15–1.93) |

| Monthly or less | 1.32 (1.08–1.61) | 1.35 (1.08–1.70) | 1.26 (0.99–1.61) | 1.25 (1.06–1.47) | 1.27 (1.05–1.53) |

| Anxiety (Yes vs No) | 1.03 (0.84–1.27) | 1.19 (0.92–1.54) | 1.06 (0.81–1.40) | 1.21 (1.02–1.44) | 1.31 (1.06–1.63) |

| Depression (Yes vs No) | 1.10 (0.93–1.30) | 1.21 (0.99–1.50) | 1.09 (0.87–1.36) | 1.19 (1.03–1.36) | 1.22 (1.03–1.44) |

| Flu Shot (Yes vs No) | 7.47 (6.30–8.85) | ─ | 6.45 (5.33–7.80) | ─ | ─ |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 18–50 | 0.47 (0.37–0.62) | 0.30 (0.22–0.43) | 0.40 (0.28–0.58) | – | – |

| 51–64 | 0.58 (0.49–0.68) | 0.43 (0.35–0.53) | 0.52 (0.42–0.64) | – | – |

| ≥65 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | – | – |

| Any DMT in last 6 months | 1.17 (0.99–1.37) | 1.34 (1.11–1.61) | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) | – | – |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 18–50—No DMT | – | – | – | 0.60 (0.48–0.76) | 0.28 (0.17–0.47) |

| 18–50—Any DMT d | – | – | – | 0.62 (0.47–0.83) | 0.44 (0.32–0.62) |

| 51–64—No DMT | – | – | – | 0.67 (0.58–0.77) | 0.46 (0.37–0.58) |

| 51–64—Any DMTd | – | – | – | 0.72 (0.59–0.88) | 0.64 (0.51–0.80) |

| ≥65—No DMT | – | – | – | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| ≥65—Any DMT | – | – | – | 1.30 (1.14–1.48) | 1.23 (0.99–1.53) |

Bold font denotes statistical significance at p <0.05. GED: general education diploma; PDDS: patient determined disease steps; DMT: disease-modifying therapy.

Hosmer Lemeshow Goodness of Fit: ꭕ2 = 2.55, p = 0.96, c-statistic = 0.67.

Hosmer Lemeshow Goodness of Fit: ꭕ2 = 3.74, p = 0.88, c-statistic = 0.78.

Hosmer Lemeshow Goodness of Fit: ꭕ2 = 8.05, p = 0.43, c-statistic = 0.64.

Unadjusted models include age-group, any disease-modifying therapy, age-group*any disease-modifying therapy. Adjusted models include all covariates for which results are shown.

Findings were largely similar for influenza vaccine, although post-secondary education was not associated with vaccine uptake, and depression and anxiety symptoms were associated with increased odds of vaccine uptake. However, we did note an interaction between age and DMT use on uptake of influenza vaccine. Specifically, respondents aged 65 years and older using DMTs had greater uptake than those aged <65 years. Respondents aged 18–64 years had reduced odds of obtaining influenza vaccine than those aged ≥65 years, however these associations were partially attenuated among respondents using DMTs.

Participants who obtained the COVID-19 vaccine but not the influenza vaccine are shown in Supplemental Table e4, and are largely similar to the study population overall although the prevalence of depression appears to be lower.

Discussion

During the pandemic, the COVID-19 virus infected millions of Americans. In this study of over 4000 people living with MS, we examined the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine and the annual influenza vaccination. We found that 85% of respondents had received COVID-19 vaccine, whereas only 75% had received the influenza vaccine. Factors associated with increased odds of COVID-19 vaccination included older age, higher socioeconomic status, being physically active, consuming some alcohol, and use of DMT whereas smoking was associated with decreased odds of vaccination. Anxiety and depression were associated with increased odds of influenza vaccination but not with COVID-19 vaccination. The strongest predictor of COVID-19 vaccination was obtaining influenza vaccination. Concerns about adverse (side) effects and potential lack of efficacy featured prominently among reasons for not being vaccinated.

Our findings regarding COVID-19 vaccination are similar to prior findings. Two surveys involving smaller samples (less than 350 participants each) of people with MS similarly found that COVID-19 vaccination rates were both 88%.6,15 As of February 2022, 87.8% of the United States population aged 18 years and older had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, where Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was the most commonly used. 16 A study relying on administrative claims data in Ontario, Canada assessed uptake of COVID-19 vaccine as of October 2021 among individuals with several immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID) including rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease as compared to the general population. 17 Eighty-two percent of the general Ontario population had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, whereas uptake ranged from 87.3% to 90.6% in those with an IMID.

Vaccine hesitancy has been the subject of substantial interest during the pandemic. Previously we showed that NARCOMS participants who did not get the annual influenza vaccine reported concerns regarding vaccine safety and adverse effects in the context of MS, as well as about efficacy. These concerns were echoed in the present survey regarding COVID-19 vaccine. Surveys of 359 people with MS in early 2021 found that 20% were vaccine hesitant. 18 Similar to our findings that survey identified concerns regarding efficacy, adverse effects particularly long term, as well as regarding the vaccine approval process and their health conditions. The two more recent surveys of people with MS, that reported vaccination rates exceeding 87%, reported common reasons for not getting vaccinated including concerns about making their MS or other health conditions worse, 15 adverse effects, and long-term safety. 6 A survey of 239 people with inflammatory bowel disease, another IMID, similarly found that vaccine hesitancy was driven by concerns regarding vaccine safety and efficacy. 19 In the survey of 237 people, individuals who did not take DMT had reduced odds of COVID-19 vaccination, and those with two or more comorbidities had increased odds; comorbidities incorporated health behaviors such as smoking. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the 359 people with MS surveyed in early 2021 included lower level of education, being non-White, not having recent influenza vaccine, lower perception of COVID-19 risk, and lower trust in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 These are largely similar to our findings, although prior studies in people with MS did not examine the relationship of vaccine hesitancy to health behaviors such as physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption nor to use of DMT. Consistent with our observations, prior studies of influenza vaccination uptake have suggested that regular physical activity and regular alcohol intake were associated with greater vaccine uptake in older (≥65 years) Canadian populations. 20 However, smoking was associated with greater vaccine uptake, in contrast to our findings and those of a study in United States’ Veterans. 21 Greater uptake among respondents using DMT may reflect an increase in perceived risk, concordant with reports that exposure to some DMTs is associated with worse outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination. 22

Limitations of this study should be considered. Our response rate was 67.6%, modestly exceeding the average response rate of 60% in the literature. 23 Participants in NARCOMS are volunteers potentially creating a selection bias. Most participants were females of White race, and aged 50 years and older thus our findings may not generalize well to males, individuals who identify as Black, Indigenous or People of Color, and younger individuals. We focused on uptake of any doses of COVID-19 vaccine and did not examine the number of doses received. Vaccination status was self-reported so could be inaccurate.

Uptake of COVID-19 vaccine was higher among people living with MS than uptake of influenza vaccine, although similar types of concerns influenced vaccine hesitancy. These concerns highlight the importance of availability of information about safety and efficacy of emerging vaccines for people living with MS, and education about these issues by health care providers. Individuals who are younger, of lower socioeconomic status and less physically active are less likely to be vaccinated and may merit targeted education efforts.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-mso-10.1177_20552173221102067 for Attitudes toward coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in people with multiple sclerosis by Ruth Ann Marrie, Casandra Dolovich, Gary R Cutter, Robert J. Fox and Amber Salter in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Ruth Ann Marrie receives research funding from CIHR, Research Manitoba, Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Research Foundation, Crohn's and Colitis Canada, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the CMSC, the Arthritis Society and US Department of Defense. She is a co-investigator on a study funded in part by Biogen Idec and Roche Canada. She is supported by the Waugh Family Chair in Multiple Sclerosis. Casandra Dolovich has no disclosures. Robert J Fox has received personal consulting fees from AB Science, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genentech, Genzyme, Immunic, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, and TG Therapeutics; has served on advisory committees for AB Science, Biogen, Genzyme, Immunic, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, and TG Therapeutics; and received clinical trial contract and research grant funding from Biogen, Novartis, and Sanofi. Amber Salter receives research funding from Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, CMSC and the US Department of Defense and serves as a consultant for Gryphon Bio, LLC. She is a member of the editorial board for Neurology. Gary Cutter is employed by the University of Alabama at Birmingham and President of Pythagoras Inc. a private consulting company located in Birmingham AL. Data and Safety Monitoring Boards: AMO Pharma, Astra-Zeneca, Avexis Pharmaceuticals, Biolinerx, Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics, Bristol Meyers Squibb/Celgene, CSL Behring, Galmed Pharmaceuticals, Green Valley Pharma, Horizon Pharmaceuticals, Immunic, Mapi Pharmaceuticals LTD, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Holdings, Opko Biologics, Prothena Biosciences, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis, Reata Pharmaceuticals, NHLBI (Protocol Review Committee), University of Texas Southwestern, University of Pennsylvania, Visioneering Technologies, Inc. Consulting or Advisory Boards: Alexion, Antisense Therapeutics, Biogen, Clinical Trial Solutions LLC, Genzyme, Genentech, GW Pharmaceuticals, Immunic, Klein-Buendel Incorporated, Merck/Serono, Novartis, Osmotica Pharmaceuticals, Perception Neurosciences, Protalix Biotherapeutics, Recursion/Cerexis Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron, Roche, SAB Biotherapeutics.

Funding: NARCOMS is a project of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC). NARCOMS is funded in part by the CMSC and the Foundation of the CMSC. The study was also supported in part by the Waugh Family Chair in Multiple Sclerosis and Research Manitoba Chair (to RAM). The funding source(s) had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

ORCID iDs: Ruth Ann Marrie https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1855-5595

Robert J. Fox https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4263-3717

Amber Salter https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1088-110X

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Ruth Ann Marrie, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Internal Medicine, Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada.

Casandra Dolovich, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Community Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada.

Gary R Cutter, Department of Biostatistics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Robert J. Fox, Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis, Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Amber Salter, Department of Neurology, Section on Statistical Planning and Analysis, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, USA.

References

- 1.Wijnands JM, Kingwell E, Zhu F, et al. Infection-related health care utilization among people with and without multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2017; 23: 1506–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montgomery S, Hillert J, Bahmanyar S. Hospital admission due to infections in multiple sclerosis patients. Eur J Neurol. 2013; 20: 1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrie RA, Tan Q, Ekuma O, et al. Development and internal validation of a disability algorithm for multiple sclerosis in administrative data. Front Neurol. 2021; 12: 754144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salter A, Fox RJ, Newsome SD, et al. Outcomes and risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a North American registry of patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2021; 78: 699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farez MF, Correale J, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: vaccine-preventable infections and immunization in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2019; 93: 584–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciotti JR, Perantie DC, Moss BP, et al. Perspectives and experiences with COVID-19 vaccines in people with MS. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2022; 8. 20552173221085242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marrie RA, Cutter GR, Fox RJet al. et al. NARCOMS And other registries in multiple sclerosis: issues and insights. Int J MS Care. 2021; 23: 276–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey questionnaire. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MBet al. et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory care quality improvement project (ACQUIP). alcohol use disorders identification test Arch Intern Med. 1998; 158: 1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marrie RA, Goldman MD. Validity of performance scales for disability assessment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 1176–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marrie RA, Salter A, Tyry Tet al. et al. High hypothetical interest in physician-assisted death in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017; 88: 1528–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green R, Kalina J, Ford Ret al. et al. SymptoMScreen: a tool for rapid assessment of symptom severity in MS across multiple domains. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2017; 24: 183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marrie RA, Kosowan L, Cutter GRet al. et al. Uptake and attitudes about immunizations in people with multiple sclerosis. Neurol: Clin Pract. 2021. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000001099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunn JA, Dunietz GL, Romeo ARet al. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination outcomes in multiple sclerosis. Neurol: Clin Pract. 2022. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000001164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. Atlanta, Georgia: Department of Health and Human Services, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widdifield J, Eder L, Chen S, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination uptake among individuals with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases in ontario, Canada between December 2020 and October 2021: a population-based analysis. J Rheumatol. 2022; 49(5): 531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehde DM, Roberts MK, Humbert ATet al. et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in adults with multiple sclerosis in the United States: a follow up survey during the initial vaccine rollout in 2021. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021; 54: 103163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke K, Pelton M, Stuart A, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2022: 1–9. 10.1007/s10620-021-07377-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrew MK, McNeil S, Merry H, et al. Rates of influenza vaccination in older adults and factors associated with vaccine use: a secondary analysis of the Canadian study of health and aging. BMC Public Health. 2004; 4: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Der-Martirosian C, Heslin KC, Mitchell MNet al. et al. Comparison of the use of H1N1 and seasonal influenza vaccinations between veterans and non-veterans in the United States, 2010. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13: 1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson-Yap S, De Brouwer E, Kalincik T, et al. Associations of disease-modifying therapies with COVID-19 severity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2021; 97: e1870–e1e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997; 50: 1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-mso-10.1177_20552173221102067 for Attitudes toward coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in people with multiple sclerosis by Ruth Ann Marrie, Casandra Dolovich, Gary R Cutter, Robert J. Fox and Amber Salter in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and analyzed during this study are held by the NARCOMS registry (narcoms.org).