Abstract

Background

COVID-19 pandemic has caused an extraordinary situation, especially for the healthcare workers (HCWs), leading to increased psychological stress. The aim of the study was to estimate the prevalence of different grades of anxiety and depression across different centers in the Philippines and identify demographic factors associated with them.

Design and Method

A cross-sectional, web-based, multi-center study was conducted among HCWs of Philippines from April 20- May 20, 2020. The study instruments used were the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Risk perception scores were analyzed using Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis test. Logistic regression was done to identify factors significantly associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression determined.

Results

A total of 516 HCWs were included in the study. Most of them have anxiety symptoms (70.74%), but only half of them have symptoms of depression (50.97%). In addition, gender, age, marital status, living status, occupation, work premises, and availability of mental health services were significantly associated with the participants' anxiety symptoms. In contrast, gender, marital status, occupation, and work premises were significantly associated with depression symptoms.

Conclusion

This study reiterates the fact and demonstrates that COVID-19 has disrupted the mental well-being of HCWs in the Philippines. Majority of HCW was psychologically affected by COVID-19. Therefore, there is a dire need to address mental illness amongst HCWs and frame guidelines based on proven algorithms to overcome these mental illnesses.

Keywords: Anxiety, COVID-19, Depression, Healthcare workers, Mental health

Significance for public health

COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected all healthcare workers physically and psychologically. This study contributed to documenting the mental health condition of healthcare workers of the Philippines and the risk factors associated with them during COVID-19 pandemics. It also presented the gap that concerned authorities should play for the welfare of mental health conditions of healthcare workers in the time of pandemic.

Introduction

Time and again, different contagious diseases, including tuberculosis, smallpox, malaria, cholera, plague, AIDS, Ebola, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and now COVID-19, have threatened and disrupted humans. The first case of COVID-19 was reported in December 2019. 1 Now, as per World Health Organization (WHO), as of 1 June 2021, a total of 170,363,852 confirmed cases and 3,546,870 death cases were reported globally. 2

Pandemics ruin the lives of everyone. Among them, healthcare workers (HCWs) suffer significantly both physically and psychologically. Previous pandemics such as SARS in 2003 and H1N1 influenza in 2009 have been reported to cause psychological problems to HCWs.3,4 Similarly, COVID-19 have also reported causing adverse effects on the mental health of study participants, including the healthcare population.5–10 HCWs cannot stay at home and maintain social distancing as a preventive measure of infection. They are professionally and humanly responsible for playing a frontline role to save human life. Therefore, they are constantly at higher risk of infection due to direct contact with patients, as seen previously in other infectious diseases, namely SARS.4,11 As a consequence of COVID-19, HCWs are under immense psychological pressure and suffer from mental illness, as experienced during SARS and H1N1 epidemics. 12

Healthy and well-equipped HCWs are the essential weapons to combat the current pandemic. Therefore, various guidelines for precautions and preventive measures are prepared for HCWs.13,14 Unfortunately, mental well-being is not much prioritized. Furthermore, the recent reports of shortages of personal protective equipment in different countries have aggravated the risk of mental illness among HCWs. 15 WHO identified the various hazards, namely exposure to the virus, increased workload, fatigue, occupational burnout, psychological distress and physical as well as psychological violence, which have put HCWs at an increased risk of infection. 16 Thus, there is an unmet need to tackle the mental illness of HCWs during the stressful conditions of pandemic. 17 To overcome this challenge, it is important to identify and measure mental health triage among HCWs. This multicenter study sought to estimate the anxiety and depression symptoms among HCWs across different centers in the Philippines. Additionally, we aimed to identify demographic factors associated with mental illness among participants.

Design and Method

Study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted by recruiting HCWs living in the three main island groups in the Philippines: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) criteria was employed in administering the web form. 18 Participants were explained regarding the procedure of study, explaining their voluntary participation and confidentiality of the data. Afterward, informed consent was obtained in the Google Forms document. This was a closed and voluntary survey with no incentives, and initial contact with all participants was made via the Internet. The survey was announced through electronic mailing lists on WhatsApp, Telegram, and other social media due to movement restrictions. Completeness checks were performed by allowing submission only after mandatory answering of all questions, and multiple entries from the same individual were prevented via mandatory email address registration

Study participants and sample size

The data collection was conducted for one month from April 20th to May 20th, 2020. Participants were recruited from all healthcare sectors, including doctors, nurses, medical assistants, laboratory technicians, public health practitioners working at either the government or private healthcare institute. The criteria for selecting participants were that adults who were 18 years old and above and had resided in the Philippines for a minimum of one week during the COVID-19 pandemic, as per the announcement made by the WHO.

The sample size was calculated with the prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms among HCWs in China (50.4%) with 95% confidence interval and 5% precision (10). Therefore, the estimated sample size required was 384 participants. However, the final sample size for the study was estimated at 768 considering a 50% attrition rate, and the overall response rate of the survey was 67.2%, i.e. 516 participants responded.

Study instrument

The survey questionnaire included five sections as follow: (i) demographic characteristics such as nationality, gender, age, religion, marital status, living status during COVID-19 pandemic, and work-related questions; (ii) Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale; 19 (iii) Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); 20 and (iv) questions adapted from Dai Y et al. regarding the risk perception among HCWs. 21 The GAD-7 and PHQ-9 were validated scales. Meanwhile, the content validation score for the risk perception and coping strategies items were 87% evaluated by five professors in public health.

The GAD-7 questionnaire assessed the anxiety level among the participants. The responses were recorded as “Not at all= 0”, “Several days =1”, “More than half of the days = 2”, “Nearly every day= 3”. The total scoring was calculated and based on the score obtained, participants were classified as having symptoms of anxiety (0-4) or normal (>4). Participants having symptoms of anxiety were further classified depending upon the score into mild (5-9), moderate (10-14), and severe (15-21). The validated PHQ-9 questionnaire was used to assess the depression level among the participants. The responses were recorded as “Not at all= 0”, “Several days =1”, “More than half of the days = 2”, “Nearly every day= 3”. Similar to anxiety, the total scoring was calculated for depression scale. Based on the score obtained, participants were classified into normal (0-4) or have symptoms of depression (>4) which was further classified into mild (5-9), moderate (10-14), moderately severe (15-19), and severe (20-27).

The risk perception of the participants was assessed by using six items. The responses were recorded as “Agree = 2”, “Neutral = 1” and “Disagree = 0”. The individual item means score and the total mean score (range: 0-12) was calculated. The higher score indicated a higher level of risk perception.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics using count and proportion were used to summarize the participants' socio-demographic profiles according to their occupation. Prevalence of anxiety and depression was computed for all participants and was correlated with the socio-demographic profile. Risk perception scores were summarized by median and Interquartile range (IQR) and compared according to different grouping variables using the Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis test. A horizontal bar graph visually identified the common coping strategies set by HCWs to overcome psychological burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. Logistic regression was done to identify significant factors associated with severe anxiety and severe depression among Filipino HCWs.

Results

Demographics

A total of 516 HCWs were included in the study. Most of the participants were doctors, aged 25-60 years, with more than 10 years of experience working in hospitals providing direct patient care. Majority of included participants were Christian, single, and living with their families. In this current time of the COVID-19 pandemic, most participants have provided healthcare to COVID-19 patients. However, only few doctors (105, 24.8%) and nurses (8, 9.20%) had access to mental health services at their respective workplaces; of those with available services, even fewer participants availed mental health support (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics and occupation of participants (n=516).

| Occupation (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors | Nurses | Others a | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 212 (50.12) | 14 (16.09) | 4 (66.67) |

| Female | 211 (49.88) | 73 (83.91) | 2 (33.33) |

| Age | |||

| ≤25 years | 4 (0.95) | 6 (6.90) | 6 (100) |

| 26-40 years | 190 (44.92) | 35 (40.23) | - |

| 41-60 years | 229 (54.14) | 38 (43.68) | - |

| ≥61 years | - | 8 (9.20) | - |

| Religion | |||

| Christianity | 385 (91.02) | 87 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Islam | 38 (8.98) | - | - |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 106 (25.06) | 53 (60.92) | 4 (66.67) |

| Single b | 317 (74.94) | 34 (39.08) | 2 (33.33) |

| Living status | |||

| Family | 357 (84.40) | 87 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Friends | 28 (6.62) | - | - |

| Alone | 38 (8.98) | - | - |

| Duration of working experience | |||

| <2years | - | - | 4 (66.67) |

| 2-5 years | 4 (0.95) | 29 (33.33) | 2 (33.33) |

| 6-10 years | 34 (8.04) | 6 (6.90) | - |

| >10 years | 385 (91.02) | 52 (59.77) | - |

| Current workplace | |||

| Hospitals | 351 (83.37) | 56 (65.88) | - |

| Clinics | 44 (10.45) | 27 (31.76) | 2 (33.33) |

| Laboratory | 22 (5.23) | - | - |

| Others c | 4 (0.95) | 2 (2.35) | 4 (66.67) |

| Working in ICU | 116 (27.42) | 6 (6.90) | - |

| Working position | |||

| Direct patient care | 405 (95.74) | 85 (97.70) | 2 (33.33) |

| Indirect patient care | 18 (4.26) | 2 (2.30) | 4 (66.67) |

| Caring for COVID-19 patients | 299 (70.69) | 54 (62.07) | - |

| Access to mental health services | 105 (24.82) | 8 (9.20) | - |

| Getting mental health support | 26/105 (24.76) | 0/8 (0) | - |

Others (occupation) included medical assistants, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, research scientists, etc.

Participants who are widowed, divorced and who never married.

Others(workplace) included pharmacy, public health office, research institute, medical university, etc.

Anxiety

Most participants reported having varying degrees of symptoms of anxiety. There were higher proportions of doctors with anxiety symptoms than nurses, but most of these doctors had mild anxiety symptoms than most of these nurses with moderate anxiety. Participants who cared for COVID-19 patients had a lower proportion of anxiety symptoms than those who did not care for COVID-19 patients. The majority of those with available mental health services had mild anxiety symptoms compared to those without available mental health services who had moderate to severe anxiety symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of anxiety among the healthcare workers (n=516).

| GAD-7 (Anxiety, %) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| Total | 151 (29.26) | 188 (36.43) | 149 (28.88) | 28 (5.43) |

| Occupation | ||||

| Doctor | 119 (28.13) | 176 (41.61) | 106 (25.06) | 22 (5.20) |

| Nurses | 32 (36.78) | 8 (9.2) | 43 (49.43) | 4 (4.60) |

| Others | - | 4 (66.67) | - | 2 (33.33) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 44 (19.13) | 94 (40.87) | 76 (33.04) | 16 (6.96) |

| Female | 107 (37.41) | 94 (32.87) | 73 (25.52) | 12 (4.20) |

| Caring for COVID-19 patients | ||||

| Yes | 109 (30.88) | 126 (35.69) | 94 (26.63) | 24 (6.80) |

| No | 42 (25.77) | 62 (38.04) | 55 (33.74) | 4 (2.45) |

| Available mental health services | ||||

| Yes | 25 (22.12) | 72 (63.72) | 10 (8.85) | 6 (5.31) |

| No | 126 (31.27) | 116 (28.78) | 139 (34.49) | 22 (5.46) |

Depression

Half of the participants had symptoms of depression in varying degrees of severity. There were lower proportions of doctors with symptoms of depression than nurses, and most were in a mild form. Most nurses with the symptom of depression were to a moderate degree. Nearly 50% of participants who directly cared for COVID-19 patients and those who did not directly care for COVID-19 patients had symptoms of depression. Availability of mental health services did not affect the prevalence of participants having symptoms of depression (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of depression among the healthcare workers (n=516).

| Normal | Mild | PHQ-9 (Depression, %) Moderate | Moderately severe | Severe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 253 (49.03) | 168 (32.56) | 69 (13.37) | 22 (4.26) | 4 (0.78) |

| Occupation | |||||

| Doctor | 215 (50.83) | 152 (35.93) | 36 (8.51) | 16 (3.78) | 4 (0.95) |

| Nurses | 38 (43.68) | 14 (16.09) | 31 (35.63) | 4 (4.60) | - |

| Others | - | 2 (33.33) | 2 (33.33) | 2 (33.33) | - |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 104 (45.22) | 76 (33.04) | 38 (16.52) | 10 (4.35) | 2 (0.87) |

| Female | 76 (33.04) | 92 (32.17) | 31 (10.84) | 12 (4.20) | 2 (0.70) |

| Caring for COVID-19 patients | |||||

| Yes | 171 (48.44) | 124 (35.13) | 38 (10.76) | 16 (4.53) | 4 (1.13) |

| No | 82 (50.31) | 44 (26.99) | 31 (19.02) | 6 (3.68) | - |

| Available mental health services | |||||

| Yes | 57 (50.44) | 30 (26.55) | 22 (19.47) | 4 (3.54) | - |

| No | 196 (48.64) | 138 (34.24) | 47 (11.66) | 18 (4.47) | 4 (0.99) |

Risk perception

All participants agreed or were neutral to the first four questionnaire statements to assess the risk perception. However, some participants disagree with statements 5 and 6 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risk perception to COVID-19 among the healthcare workers (n=516).

At least one occupation has significantly different risk perception score distribution/ mean ranks. Post-hoc Dunn test shows that doctors have significantly lower risk perception score mean ranks than nurses (p<0.0001); others have significantly lower risk perception score mean ranks than nurses (p=0.0088); no sufficient evidence to conclude that there is a difference in risk perception score mean ranks between doctors and others (p=0.2497).

Males have significantly lower risk perception score mean ranks than females (p<0.0001). However, there is no sufficient evidence to conclude that there is a difference in risk perception score mean ranks between gender (Table 4).

Table 4.

Risk perception scores to COVID-19 among the healthcare workers (n=516) Mann-Whitney test/ Kruskal-Wallis, as appropriate.

| Variables | Total score (Median, Min-Max) | Mean ranks | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Over-all | 12 (6-12) | ||

| Occupation | 0.0001 | ||

| Doctor | 12 (6-12) | 243 | |

| Nurses | 12 (10-12) | 336 | |

| Others | 11 (11-12) | 208 | |

| Gender | 0.0266 | ||

| Male | 12 (6-12) | 245 | |

| Female | 12 (6-12) | 270 | |

| Caring for COVID-19 patients | 0.3021 | ||

| Yes | 12 (6-12) | 262 | |

| No | 12 (9-12) | 250 | |

| Available mental health services | 0.3157 | ||

| Yes | 12 (6-12) | 269 | |

| No | 12 (6-10) | 256 |

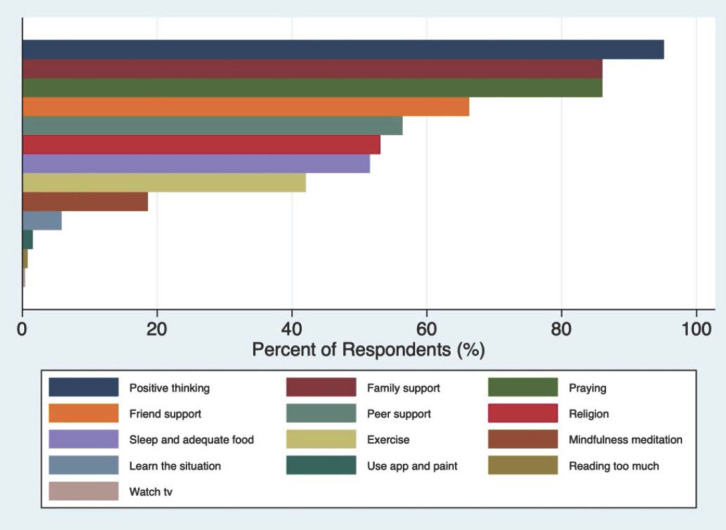

Coping strategies

The common (more than 80% of participants) coping strategies practice among HCWs included in our study were positive thinking, family support, and praying (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Coping strategies practiced among healthcare workers to overcome psychological burden during COVID-19 pandemic.

Factors associated with anxiety

Significant factors predicting severe anxiety symptoms among HCWs in our study were gender, age, marital status, living status, occupation, work premises, and availability of mental health services (Table 5). Controlling for all other factors, we found the following: i) females had lower odds of having severe anxiety symptoms than males; ii) higher age groups had higher odds of having severe anxiety symptoms than those aged less than 25 years; iii) single (unmarried) participants had lower odds of having severe anxiety symptoms than married participants; iv) those living with the family at this time of the COVID-19 pandemic had lower odds of having severe anxiety symptoms than those living alone; v) nurses and participants of other occupations had higher odds of having severe anxiety symptoms than doctors; vi) those who worked in ICU had higher odds of having severe anxiety symptoms than those who did not; vii) those with available mental health services at their workplace had lower odds of having severe anxiety symptoms than those without.

Table 5.

Factors associated with severe anxiety symptoms a among the healthcare workers.

| Variables | Number of severe cases (%) | Univariable OR (95% CI) | p | Multivariable Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 92 (40) | Reference | |||

| Female | 85 (29.72) | 0.63 (0.44-0.91) | 0.015 | 0.33 (0.2-0.53) | <0.001 |

| Age | |||||

| ≤25 years | 4 (25) | Reference | |||

| 26-40 years | 71 (31.56) | 1.38 (0.43-4.44) | 0.586 | 8.05 (1.46-44.36) | 0.017 |

| 41-60 years | 96 (35.96) | 1.68 (0.53-5.37) | 0.378 | 12.64 (2.28-69.93) | 0.004 |

| ≥61 years | 6 (75) | 9 (1.27-63.89) | 0.028 | 22.33 (2.17-230.16) | 0.009 |

| Religion | |||||

| Christianity | 177 (37.03) | Reference | |||

| Islam | 0 (0) | - | - | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 112 (31.73) | Reference | |||

| Single b | 65 (39.88) | 0.7 (0.48-1.03) | 0.070 | 0.58 (0.35-0.96) | 0.034 |

| Staying with | |||||

| Alone | 24 (63.16) | Reference | |||

| Friends | 0 (0) | - | - | - | - |

| Family | 153 (34) | 0.3 (0.15-0.6) | 0.001 | 0.19 (0.08-0.42) | <0.001 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Doctors | 128 (30.26) | Reference | |||

| Nurses | 47 (54.02) | 2.71 (1.69-4.33) | <0.001 | 4.5 (2.39-8.48) | <0.001 |

| Others c | 2 (33.33) | 1.15 (0.21-6.37) | 0.871 | 8.62 (0.75-99.61) | 0.084 |

| Work experience | |||||

| <2years | 2 (50) | Reference | |||

| 2-5 years | 21 (60) | 1.5 (0.19-11.93) | 0.702 | ||

| 6-10 years | 6 (15) | 0.18 (0.02-1.51) | 0.113 | ||

| >10 years | 148 (33.87) | 0.51 (0.07-3.67) | 0.506 | ||

| Workplace | |||||

| Hospitals | 150 (36.86) | Reference | |||

| Clinics | 25 (34.35) | 0.89 (0.53-1.51) | 0.670 | ||

| Laboratory | 0 (0) | - | - | ||

| Others d | 0 (0) | - | - | ||

| Working in ICU | 64 (52.46) | 2.74 (1.81-4.16) | <0.001 | 3.78 (2.29-6.23) | <0.001 |

| Working position | |||||

| Direct patient care | 177 (35.98) | Reference | |||

| Indirect patient care | 0 (0) | - | - | ||

| Caring for COVID-19 | 118 (33.43) | 0.89 (0.6-1.31) | 0.538 | ||

| patients | |||||

| Available mental health services | 16 (14.16) | 0.25 (0.14-0.44) | <0.001 | 0.14 (0.07-0.27) | <0.001 |

| Getting mental health support | 2/26 (7.69) | 0.28 (0.1-0.81) | 0.019 |

Participants who had GAD-7 total score of ≥10 are considered to have severe anxiety symptoms.25

Participants who are widowed, divorced and who never married.

Others (occupation) included medical assistants, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, research scientists, etc.

Others (workplace) included pharmacy, public health office, research institute, medical university, etc.

Interestingly, at this time of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is no supporting evidence that taking care of COVID-19 patients will have greater odds of having severe anxiety symptoms than those who do not.

Factors associated with depression

Significant factors predicting severe depressive symptoms among HCWs included in our study were gender, marital status, occupation, workplace, and work premises (Table 6). Controlling for all other factors, we found the following: i) females had lower odds of having severe depressive symptoms than males; ii) single (unmarried) participants had lower odds of having severe depressive symptoms than married participants; iii) nurses and participants of other occupations had higher odds of having severe depressive symptoms than doctors; iv) those who worked in clinics and other places had higher odds of severe depressive symptoms than those in hospitals; v) those who worked in ICU had lower odds of having severe depressive symptoms than those who did not.

Table 6.

Factors associated with the prevalence of severe depressive symptoms a among the healthcare workers.

| Variables | Number of severe cases (%) | Univariable OR (95% CI) | p | Multivariable Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 50 (21.74) | Reference | |||

| Female | 45 (15.73) | 0.67 (0.43-1.05) | 0.081 | 0.37 (0.21-0.66) | 0.001 |

| Age | |||||

| ≤25 years | 4 (25) | Reference | |||

| 26-40 years | 39 (17.33) | 0.63 (0.19-2.05) | 0.442 | ||

| 41-60 years | 46 (17.23) | 0.62 (0.19-2.02) | 0.432 | ||

| ≥61 years | 6 (75) | 9 (1.27-63.89) | 0.028 | ||

| Religion | |||||

| Christianity | 95 (19.87) | Reference | |||

| Islam | 0 (0) | - | - | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 40 (11.33) | Reference | |||

| Single b | 55 (33.74) | 0.25 (0.16-0.4) | <0.001 | 0.4 (0.24-0.66) | <0.001 |

| Staying with | |||||

| Alone | 4 (10.53) | Reference | |||

| Friends | 4 (14.29) | 1.42 (0.32-6.23) | 0.645 | ||

| Family | 87 (19.33) | 2.04 (0.7-5.89) | 0.189 | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Doctors | 56 (13.24) | Reference | |||

| Nurses | 35 (40.23) | 4.41 (2.64-7.36) | <0.001 | 3.7 (1.94-7.06) | <0.001 |

| Others c | 4 (66.67) | 13.11 (2.35-73.23) | 0.003 | 2.32 (0.31-17.65) | 0.415 |

| Work experience | |||||

| < 2years | 2 (50) | reference | |||

| 2-5 years | 23 (65.71) | 1.92 (0.24-15.35) | 0.540 | ||

| 6-10 years | 6 (15) | 0.18 (0.02-1.51) | 0.113 | ||

| >10 years | 64 (14.65) | 0.17 (0.02-1.24) | 0.081 | ||

| Workplace | |||||

| Hospitals | 64 (15.72) | reference | |||

| Clinics | 25 (34.25) | 2.79 (1.61-4.85) | 0.000 | 2.53 (1.26-5.11) | 0.009 |

| Laboratory | 0 (0) | - | - | - | - |

| Othersd | 6 (60) | 8.04 (2.21-29.29) | 0.002 | 5.5 (1.19-25.3) | 0.029 |

| Working in ICU | 14 (11.48) | 0.5 (0.27-0.92) | 0.026 | 0.77 (0.4-1.49) | 0.437 |

| Working position | |||||

| Direct patient care | 89 (18.09) | reference | |||

| Indirect patient care | 6 (25) | 1.51 (0.58-3.91) | 0.397 | ||

| Caring for COVID-19 patients | 58 (16.43) | 0.67 (0.42-1.06) | 0.089 | ||

| Available mental health services | 26 (23.01) | 1.45 (0.87-2.41) | 0.155 | ||

| Getting mental health support | 4/26 (15.38) | 0.67 (0.23-1.96) | 0.462 |

Participants who had PHQ-9 total score of ≥10 are considered to have severe depressive symptoms. 25

Participants who are widowed, divorced and who never married.

Others (occupation) included medical assistants, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, research scientists, etc.

Others (workplace) included pharmacy, public health office, research institute, medical university, etc.

Interestingly, at this time of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is no supporting evidence that taking care of COVID-19 patients will have greater odds of having severe depressive symptoms than those who do not.

Discussion

Intending to identify mental health status among HCWs across different healthcare centers in the three islands of the Philippines, we conducted this study.

The study found that 5% and 29% of participants had severe and moderate levels of anxiety symptoms, respectively. A recent meta-analysis revealed the prevalence of anxiety in HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic was 23%. 22 However, another multi-center study conducted in India and Singapore demonstrated only 8.7% of anxiety prevalence. 23 A higher proportion of doctors had anxiety symptoms than nurses; however, doctors majorly had a mild form of symptoms of anxiety and nurses had moderate. However, a recent report reported that the prevalence of anxiety was higher in nurses (27.9%) than doctors (11.4%). 24 Surprisingly, HCWs who cared for COVID-19 patients, had lower proportions of anxiety scores than those who did not.

Undoubtedly, the availability of mental health services resulted in better outcomes, as depicted by a lower proportion of HCWs with moderate anxiety symptoms than those who did not have available mental health services. We also identified gender, age, marital status, living status (alone or with family/friends), occupation, working place (ICU or not), and availability of mental health services as significant factors that predicted anxiety symptoms among these HCWs. Male HCWs of age more than 25 years, single unmarried, living alone, nurses and of other occupations, working in ICU, and without available mental health services had higher odds of developing severe anxiety symptoms than their counterparts. Zhu et al. identified that the prevalence of anxiety was higher in females than our finding. 24 Interestingly, there was no correlation between caring for COVID-19 patients and the odds of having anxiety symptoms in our study. However, Lai et al. reported that the HCWs who were directly in contact with COVID-19 infected patients were associated with higher risk symptoms of anxiety [odds ratio (OR),1.57; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.22-2.02; P < 0.01]. 25 Additionally, Chew et al. reported the association of stress level with physical symptoms. 23 In addition to HCW, the general population also suffers from clinically significant anxiety levels, and 28.8% population was reported to have moderate to severe anxiety in a Chinese cohort of the general population. 26

Like anxiety, depression is also a global concern. The prevalence of depression was found to be 22.8%in the HCWs according to the recent meta-analysis. 22 In our study, the PHQ-9 analysis revealed that around 51% of the study population had symptoms of depression at different levels. Nearly 49% and 52% of doctors and nurses were found to have symptoms of depression during the survey period, respectively; 55% and 64% of male and female HCWs had symptoms of depression, respectively. On the contrary, Zhu et al. reported that slightly lower: 46% and 43% of doctors and nurses suffered from depression, respectively. 24 However, caring for COVID-19 patients and the availability of mental health services did not make an impact to the proportion of HCWs suffering from depression. In the Chinese population, it was reported that 50.4% of HCWs exhibited symptoms of depression associated with the engagement with COVID-19 patients (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.11-2.09; P = 0.01). 25 Thus, the proportion of HCWs who had depression symptoms could be correlated with the risk perception to COVID-19. The factors associated with predicting symptoms of severe depression included gender (males had higher odds of developing severe depression than females), marital status (married people had higher odds than single people), occupation (doctors had lower odds than any other occupant), workplace (those who worked at hospitals had higher odds than those who worked elsewhere), and working in ICU (those who did not work in ICU had higher odds than those who did). Nurses had a higher risk perception than doctors and other occupants (p<0.0001). Notably, the risk perception was not different between HCWs caring for COVID-19 patients or caring for non-COVID-19 patients and between HCWs who had mental health services and who did not have mental health services.

Our study found that the nurses had a higher prevalence of symptoms associated with mental illness. This could be attributed to nurses being more exposed to the COVID-19 patients in the ward, providing direct care to the patients, and collecting samples for the diagnostic tests.

In addition to depression and anxiety, other mental illnesses such as insomnia, distress, and post-traumatic stress disorder were also reported among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.23,25 In one study, insomnia was reported in 34.0% of HCWs and was associated with direct contact with COVID-19 patients (OR, 2.97; 95% CI, 1.92-4.60; p<0.001); distress was reported in 71.5% of HCWs and was associated with direct contact with COVID-19 patients (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.25-2.04; p<0.001). 25 Another study reported stress and psychological distress in 2.2% of and 3.8% of HCWs, respectively. 23 The mental health of all HCWs was found similar globally. Even in the general population, COVID-19 resulted in psychological impact (53.8%) and stress (8.1%). 26 However, Cheung et al. reported that the HCWs are more prone to anxiety, burnout, and mental exhaustion during the pandemic. 27 A German study reported high levels of anxiety and depression among doc-tors. 28 It is known that unattended psychological issues result in intense pressure, prompting the individual to commit suicide. West et al., reported that physicians are at an increased risk of suicide than the general population. 29 Unfortunately, Montemurro et al., reported that accumulated psychological pressure and intense fear of death led to incidences of suicide amongst HCWs. 30

Additionally, the spread of infection to colleagues, friends, and family, lack of protective gear, and medical violence contributed to the psychological burden among HCWs.21,31 Xiao et al., negatively correlated the level of social support with the prevalence of anxiety and stress. 32 Therefore, in addition to the mental health services, coping strategies to combat psychological disorders at an individual level should be encouraged. Our study found that the HCWs practiced different coping strategies to overcome the challenging psychological burden during this pandemic. The most commonly used coping strategies included positive thinking, family support, and praying.

In addition to the fear of getting infected, HCWs often fear spreading the virus to their families, friends, and colleagues. To avoid this, HCWs are often suggested to undergo quarantine if exposed to high-risk situation. During the SARS epidemic, it was observed that HCWs who were quarantined, had more symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder than those who were not quarantined. 4 Additionally, it was also observed that the HCWs who worked directly in the SARS hospitals and units reported anxiety, fear, frustration, and depression.4,10 To this end, early interventions should be focused to acknowledge the global concern of mental illness among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kang et al., showed that early health support was essential even when the psychological symptoms were mild. 33 A digital learning package was introduced in the UK within the first three weeks of COVID-19 outbreak in UK. 34 This package included evidence-based guidance and support for the HCWs.

Additionally, it included signposting related to the mental well-being of the HCWs during the pandemic. 34 Such efforts should be made globally. In addition to this, other approaches can also be employed to support HCWs psychologically. These approaches include virtual clinics, chat lines, remote psychological therapies, psycho-education, and social support. It could not be emphasized that the mental well-being of HCWs is of utmost importance in providing medical support during the COVID-19 pandemic. With this study, we contribute to the data pool, which will help assessing healthcare providers' mental health status.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has tremendously impacted HCWs and has rendered them prone to mental fatigue and mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression. With this study, we reiterate this fact and demonstrate how COVID-19 has disrupted the mental well-being of HCWs in the Philippines. Irrespective of age, gender, occupation, and work profile, every HCWs is psychologically affected by COVID-19. Different risk factors are associated with the severity of illness, and HCWs have identified different coping strategies to combat these illnesses. Despite these coping mechanisms, there is a dire need to address the mental illness amongst HCWs and frame guidelines based on the proven algorithms to overcome these mental illnesses.

Footnotes

Contributions: RRM and MNH conceived and designed the study. RRM and UC performed validation and reliability of the questionnaire. RRM and EQV collected the data. EQV conducted the statistical analysis and interpretation of the findings. UC, RRM, EQV and MNH wrote the initial draft. UC and RRM wrote the final manuscript. RS and SS critically reviewed and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding: No funding was received for this particular study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee from Asia Metropolitan University (AMU), Project Ref No: AMU/MREC/FOM/NF/03/2020.

Availability of data and material: All the data supporting our findings have been presented in the manuscript; the datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Consent from the patient for the publication was taken before collecting the data from them.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative(s) for anonymized patient information to be published in this article

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020;395:470–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. WHO. Published 2021. Accessed May 20, 2021. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/

- 3.Wong LP, Sam IC. Behavioral responses to the influenza A(H1N1) outbreak in Malaysia. J Behav Med 2011;34:23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: Exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry 2009;54:302–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marzo RR, Ismail Z, Nu Htay MN, et al. Psychological distress during pandemic Covid-19 among adult general population: Result across 13 countries. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal 2021;10:100708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marzo RR, Singh A, Mukti RF. A survey of psychological distress among Bangladeshi people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal 2021;10;100693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marzo RR, Villanueva EQ, Faller EM, Baldonado AM. Factors associated with psychological distress among filipinos during coronavirus disease-19 pandemic crisis. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2020;8:309–13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Respati T, Irasanti SN, Sartika D, Akbar IB, Marzo RR. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Indonesian residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Public Heal Sci 2021;10:119–26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Htay MNN, Marzo RR, Al Rifai A, et al. Immediate impact of COVID-19 on mental health and its associated factors among healthcare workers: A global perspective across 31 countries. J Glob Health 2020;10:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, et al. COVID-19-Related Mental Health Effects in the Workplace: A Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:7857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ 2003;168:1245–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed Asymptomatic Carrier Transmission of COVID-19. JAMA 2020;323:1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cirrincione L, Plescia F, Ledda C, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: Prevention and Protection Measures to Be Adopted at the Workplace. Sustainability 2020;12:3603. [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Healthcare Workers: Information on COVID-19. Accessed May 22, 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/index.html

- 15.World Health Organization. Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide. WHO, March 2020. Accessed May 20, 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/03-03-2020-shortage-of-per-sonal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide

- 16.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (Covid-19) outbreak: Rights, roles and responsibilities of health workers, including key considerations for occupational safety. WHO, December 2019. Accessed May 20, 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-rights-roles-respon-hw-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=bcabd401_0

- 17.Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiat 2020;7:228–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang YL, Liang W, Chen ZM, et al. Validity and reliability of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 to screen for depression among college students in China. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 2013;5:268–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai Y, Hu G, Xiong H, et al. Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on healthcare workers in China. medRxiv 2020: doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20030874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:901–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:559–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu J, Sun L, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression symptoms in the first-line medical staff fighting against COVID-19 in Gansu. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheung T, Fong TKH, Bressington D. COVID-19 under the SARS Cloud: Mental Health nursing during the pandemic in Hong Kong. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2021;28:115–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohlken J, Schömig F, Lemke, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: Stress experience of healthcare workers: A short current review. Psychiatr Prax 2020;47:190–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 2018;283:516–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montemurro N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: From medical staff to common people. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:23–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Heal 2020;8:e790–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, et al. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit 2020;26:e923549–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blake H, Bermingham F, Johnson G, Tabner A. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: A digital learning package. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]