Abstract

Purpose:

The standards of care for transgender and gender diverse youth (TGDY) experiencing gender dysphoria are well-established and include gender-affirming medical interventions. As of July 2021, 22 states have introduced or passed legislation that bans the provision of gender-affirming medical care to anyone under the age of 18 even with parent or guardian consent. The purpose of this study is to understand what providers who deliver gender-affirming medical care to TGDY think about this legislation.

Methods:

In March 2021, we recruited participants via listservs known to be frequented by providers of gender-affirming medical care. Eligible participants were over the age of 18, currently working as a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician’s assistant, and providing gender-affirming care to TGDY under the age of 18 in the U.S.

Results:

We analyzed the responses of 103 providers from all 50 states and DC. Most participants identified as white (77%), cisgender women (70%), specializing in pediatric care (52%). The most salient theme, described by nearly all participants, was the fear that legislation banning gender-affirming care would lead to worsening mental health including increased risk for suicides among TGDY. Other themes included the politicization of medical care, legislation that defies the current standards of care for TGDY, worsening discrimination toward TGDY, and adverse effects on the providers.

Conclusions:

Providers of gender-affirming care overwhelmingly opposed legislation that bans gender-affirming care for TGDY citing the severe consequences to the health and well-being of TGDY along with the need to practice evidence-based medicine without fear.

Keywords: Transgender, Adolescent, Health Personnel, Providers, Laws and statutes, Gender dysphoria, Gender affirmation

The standards of care for transgender and gender diverse youth (TGDY) experiencing gender dysphoria are well-established and include mental health counseling, prescription of puberty blockers, hormones, and in some cases gender-affirming surgeries [1–3]. Risks of prolonged gender dysphoria in adolescents include increased suicidal ideation, anxiety, and depression [3–9]. Gender-affirming medical interventions improve social and mental health outcomes, such as decreased suicidal ideation and improved peer relations that last into adulthood [3–8,10,11].

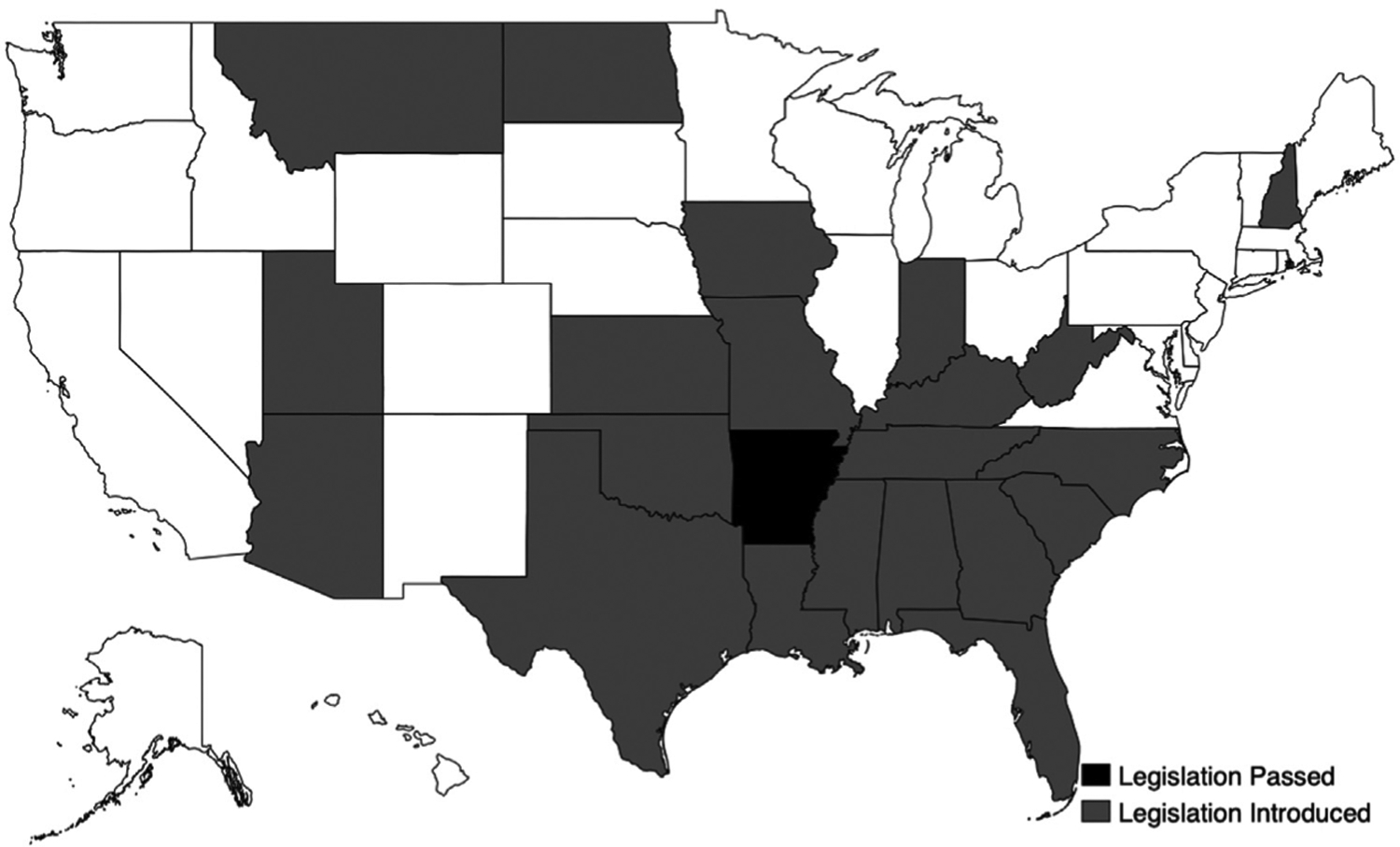

Despite evidence of the benefits of gender-affirming care for TGDY, as of July 2021, 22 states have introduced legislation that bans the provision of gender-affirming medical care (e.g., hormones, puberty blockers, surgeries) to anyone under age 18 years even with the consent of a parent or guardian consent [12,13]. So far, Arkansas is the only state to have passed this type of legislation [12]. See Figure 1 for a map of states that have introduced or passed this legislation. This legislation would impose criminal and/or civil liability to anyone who provides gender-affirming care to TGDY, with possible penalties ranging from revocation of a medical license to 20 years in prison [14,15]. Furthermore, several states have included provisions that would require school counselors, teachers, and others to disclose whether a child is experiencing gender dysphoria to their legal guardians regardless of the child’s will [16,17]. In some cases, this legislation imposes liability on guardians under the state’s child abuse statutes, which means that guardians could face fines, prison time, or lose custody if their child received gender-affirming care in states where this legislation is passed [18–20]. This legislation stands in direct opposition to current standards of care and national and international medical organizations have recently made statements opposing this legislation [21–23].

Figure 1.

States that have passed or introduced bans on gender-affirming care for trans youth. Notes: Based on available information in July 2021.

TGDY and their families already face significant barriers to accessing care such as few pediatricians trained in providing gender-affirming care, lack of consistent protocols, discrimination, and insurance exclusions [24–26]. Legislation that bans gender-affirming care for TGDY creates a formidable legal-structural barrier to this care for TGDY and their families [27]. Indeed, guardians of TGDY have described feeling distressed that laws banning gender-affirming care for TGDY would have devastating effects on TGDY [27]. Particularly, guardians of TGDY have described that under such laws their children are more likely to attempt suicide and self-harm, and more likely to experience discrimination, anxiety, and depression [27].

Although the perspectives of guardians on such legislation have been elucidated elsewhere [27], the perspectives of those who provide gender-affirming medical care to minors have yet to be described in the literature. Given that medical providers are essential to decision-making regarding the provision of gender-affirming care, understanding their perspectives is important to assessing the effects of this legislation on their practice, their patients, and their patients’ families. Furthermore, providers face significant civil and criminal liability as this legislation subjects providers to serious legal consequences for providing evidence-based gender-affirming care to TGDY.

Methods

In March of 2021, we recruited participants via professional society listservs for providers of pediatric gender-affirming medical care. Additionally, we encouraged sharing the survey link through professional networks and clinics that provide pediatric gender-affirming care following the basic tenets of a purposive snowball sample. To be eligible for our study, we required that: (1) a person be over the age of 18; (2) currently work as a physician (MD/DO), nurse practitioner, or physician’s assistant; and (3) currently provide gender-affirming care (e.g., prescribe hormones or puberty blockers) to TGDY under the age of 18 in the U.S. The survey was only available in English and data were collected using Qualtrics. Consent for the study was collected electronically.

The survey was developed by a multidisciplinary team of researchers and medical providers who each have a commitment to addressing inequities among TGDY. Before fielding the survey, five medical providers with relevant clinical expertise beta-tested the survey to ensure the content was clear and the skip logic worked appropriately. Prior to responding, participants were provided with the following information: “Several state legislatures in the United States are currently considering laws that would make providing gender-affirming care, specifically puberty blockers (leuprolide, histrelin), hormones (estrogen, testosterone), and surgeries to anyone under the age of 18 illegal regardless of parent/caregiver consent.” Participants were asked to provide their thoughts about these proposed laws in four separate open-ended survey questions: “What do laws like this mean to you as a gender-affirming care provider for transgender and gender diverse youth?” “How do you think laws like this would impact your practice?” “How do you think laws like this would impact your patients?” “What steps, if any, do you think would be helpful to ensure transgender and gender diverse youth receive gender-affirming care?” Participants who reported being aware of these potential laws before taking the survey were also asked: “Since becoming aware of these potential laws, what has your experience with providing gender-affirming medical care been like?” In addition, participants provided information on their demographics, medical practice, and the types of gender-affirming care they provide. Participants did not receive compensation. This study was ruled exempt by the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board (HUM00196292).

First, we conducted univariate analyses to characterize the study sample. Next, we employed an inductive thematic approach to open-ended responses [28]. Two members of the study team familiarized themselves with all of the responses. These two team members identified broad themes that were refined through discussions. The first author then indexed the data and identified specific sections that corresponded to our themes. Discrepancies in interpretation were resolved through discussions with the entire team.

Results

Overall, we screened 240 participants and 103 eligible providers from across the U.S. participated in the study. As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants identified as cisgender women (63%), with 21% identifying as cisgender men, 2% trans men, and 4% nonbinary or genderqueer. Participants ranged in age from 27 to 69 (mean [M] = 43, standard deviation [SD] = 9.4) and the majority (73%) had been providing gender-affirming medical care to TGDY for over 4 years. Most of the participants identified as white (70%) and represented all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia and were spread evenly across Census Regions. Forty participants, or 39% of our eligible sample practiced medicine in states where legislation banning the provision of gender-affirming medical care has either passed or been introduced. The majority were physicians (97%), followed by nurse practitioners (2%) and physician’s assistants (1%). Most participants specialized in pediatrics (52%) and provided hormones (93%), menstrual suppression (88%), antiandrogens (86%), puberty blockers (81%), and surgery referrals (85%) to their patients. We identified five overarching themes from the qualitative survey responses that are summarized below. Table 2 presents additional quotes.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n = 103)

| Age, mean (standard deviation) | 43 | (9.4) |

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| Gender identitya | ||

| Cisgender women | 65 | (63) |

| Cisgender men | 22 | (21) |

| Trans men | 2 | (2) |

| Nonbinary or genderqueer | 4 | (4) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 72 | (70) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 5 | (5) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2 | (2) |

| Non-Hispanic Middle Eastern, North | 2 | (2) |

| African, Arab, or Chaldean | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 4 | (4) |

| Biracial or other | 7 | (7) |

| Current occupation | ||

| Doctor (MD/DO) | 100 | (97) |

| Nurse practitioner | 2 | (2) |

| Physician’s assistant | 1 | (1) |

| Primary trainingb | ||

| Pediatrics | 54 | (52) |

| Adolescent medicine | 39 | (38) |

| Endocrinology | 32 | (31) |

| Family medicine | 10 | (10) |

| Other | 6 | (6) |

| Census region where providers practiceb | ||

| Midwest | 40 | (39) |

| Northeast | 57 | (55) |

| South | 51 | (50) |

| West | 52 | (50) |

| Gender-affirming care providedb | ||

| Prescribed hormones | 96 | (93) |

| Prescribed menstrual suppressants | 91 | (88) |

| Prescribed antiandrogens | 89 | (86) |

| Surgery referrals | 88 | (85) |

| Prescribed puberty blockers | 83 | (81) |

| Letter writing to support medical care | 81 | (79) |

| Mental healthcare | 18 | (17) |

| Time providing gender-affirming care to TGDYa | ||

| <1 year | 4 | (4) |

| 1–3 years | 23 | (22) |

| 4–6 years | 35 | (34) |

| 7–9 years | 22 | (21) |

| 10–19 years | 15 | (15) |

| 20+ years | 3 | (3) |

| Number of TGDY patientsa | ||

| <5 | 2 | (2) |

| 5–10 | 12 | (12) |

| 11–50 | 29 | (28) |

| 51–100 | 16 | (16) |

| 101–150 | 10 | (10) |

| 151–200 | 8 | (8) |

| 201+ | 25 | (24) |

TGDY = transgender and gender diverse youth.

Note all responses were optional, therefore some categories do not total to 100%.

Greater than total n as participants are able to choose more than one option.

Table 2.

Additional exemplary quotes by theme

| Theme 1: politicization of care “[These laws] are interference of politics in my professional life and the personal lives of my patients. Every time politics and medicine co-mingle, people die” “We are telling our patients about the laws. I typically do not actively talk politics in my exam room, but given the consequences of these laws, I feel it is a duty I have to let them know that if these laws pass, no one will provide care for them for fear of not being able to be a physician at all” Theme 2: legislation defies standards of care “These laws will be devastating for transgender/gender-diverse youth because they would outlaw and/or restrict treatments known to be effective in relieving gender dysphoria. It is akin to outlawing or restricting antibiotics to treat bacterial infections. It is irrational and not based on any science” “It’s deliberately and explicitly in opposition to the body of medical research and the established standards of care for gender dysphoria in children and adolescents, and is based on total ignorance of the medical literature and the nature of gender dysphoria” Theme 3: worsening mental health of TGDY and their families “Patients have increased anxiety and an increased urgency to start treatment in hopes that once started it will not be taken away from them. Just the proposal of the legislation has had minor but detectable negative impact on the majority of transgender teens and their families in my clinic” “This will lead to an increase in mental health problems for TGNB youth and will, without a doubt, be responsible for an increase in suicidality for this vulnerable population” “Some would be suicidal. Some would completely shut down. Some would break the law to get gender affirmative treatment. None would change their gender identity” |

Theme 4: worsening discrimination of TGDY “My patients are not going to feel safe being trans, especially if their family could be reported for child abuse just for supporting them. They already face a higher rate of bullying, depression, anxiety, etc-these laws will only make it worse” “I would also expect to see increased adverse events such as bullying and physical and sexual abuse as people feel more empowered and emboldened when the law supports their cause” Theme 5: adverse impact on providers “It just keeps me up more at night. You go into medicine because you want to help people. I spend a lot of time second guessing myself now, thinking “Are there really that many people who think that the work I do is wrong, when I am trying so hard to help people? Could it be?.” It is hard. But I am still doing the care. Once I get in the room (or a screen) with a patient/family, those fears, worries and negative thoughts pretty much fade away and I know I am helping” “[Since these bills have been introduced] we have protests occurring around our clinic but because we are mostly virtual right now we are able to protect our patients and families. Our clinic leaders receive hate mail often. We feel more emboldened to continue this hard and important work. We are saving lives” “I would be forced to choose between following the oath that I took when I became a physician (in which I vowed to do no harm, to deliver high quality care, and to practice in the best interests of the patient), and risk losing my medical license, my employment, or even my freedom (by serving jail time)” |

TGDY = transgender and gender diverse youth; TGNB = transgender and gender nonbinary.

Theme 1: politicization of care

Providers described how legislation that bans gender-affirming care for TGDY unnecessarily enables the influence of political ideology into the provision of medical care. For example, providers described how this legislation allows the government and politicians to interfere with medical decision-making processes for youth and families.

“[I am] very upset that legislators, who likely do not have any personal experience or knowledge of transgender health, are making healthcare decisions for families - ones that actually may increase the despair these kids and families feel. I can foresee an uptick in suicides among these kids.”

(Nevada)

“Preventing me from using my training and expertise to do my job shows such a lack of understanding of the severity of this situation for patients and trust in medical training on the part of lawmakers. Politicizing healthcare is frankly unacceptable and that is just what this is.”

(Pennsylvania)

Providers also described how they must engage in political processes (e.g., advocacy, contacting politicians) to protect their patients’ civil rights while serving their medical needs; however, some also described their own fears around advocacy efforts.

“This law will affect the well-being of my transgender pediatric patients. It will limit their right to medical care.”

(Tennessee)

“I am more fearful of seeing young patients since I live in a state with this legislation proposed. I fear to advocate my position to my elected representatives due to concern that I will be targeted later by them for punishment.”

(Georgia)

Theme 2: legislation defies standards of care

Providers described how this legislation restricts them from providing medical care according to the standards of care [1–3]. Many providers described this legislation as being at odds with the scientific literature and evidence-based practices.

“Laws like this would handcuff our ability to provide standards of medical care our patients deserve.”

(New York)

Furthermore, providers described how denial of evidence-based, gender-affirming care for TGDY will necessitate more serious and costly interventions including avoidable surgeries later in life.

“[L]imiting pubertal blocking and hormone therapy will lead to a need and desire for these individuals to later request surgical interventions to reverse changes which could have been prevented by hormones.”

(Oregon)

Theme 3: worsening mental health of transgender and gender diverse youth and their families

Nearly every provider believed that these laws would adversely impact the mental health of TGDY and their families. Providers mentioned that they would see an increase in suicide/ideation, depression, anxiety, gender dysphoria, and addiction among their patients.

“People will die if this legislation is enacted - we see all across the world that anti-trans legislation leads to poorer mental health and physical health outcomes for trans youth. Access to puberty blockers and gender affirming hormones is clearly associated with better mental and physical and social health outcomes. This legislation is one of the absolute worst things that could happen for LGBTQ health.”

(Minnesota)

Providers were also concerned that, in response to this legislation, TGDY would get hormones and other medical care from unregulated means placing them at greater risk for poor health.

“I fear it would lead to increased suicide attempts and completed suicides as well as a search for illegal means of getting the medications which are a normal, evidence-based part of healthcare for trans youth.”

(Massachusetts)

Providers also mentioned how TGDY and their families have become increasingly anxious since these bills have been introduced, which has taken up time that would be best spent on providing care.

“My patients are terrified. I’m probably getting 1–2 messages per week from parents and kids asking what they can do to protect the children from these potential laws.”

(Arizona)

“Many patients and families have expressed concern and anxiety around these bills. This has taken up a lot of time during visits which could have been used discussing other things.”

(Washington)

Theme 4: worsening discrimination of transgender and gender diverse youth

This legislation was often described as a serious form of discrimination targeting TGDY. Some mentioned how this legislation can further justify societal exclusion and interpersonal bullying of TGDY among their peers.

“[This legislation] creates an environment of fear and intolerance in the general population.”

(Montana)

“[This legislation] will tell [TGDY] as emerging adults that society does not care about them as a person or their medical needs. This will create an adult citizen who does not feel part of our society.”

(Virginia)

Theme 5: adverse impact on providers

Providers’ responses varied when asked whether this legislation would impact their practice. Some providers mentioned how this legislation would shut down or alter the care provided at their clinics because their primary service involves provision of gender-affirming care for TGDY. Some have considered moving to other states to continue providing gender-affirming care due to the professional, legal, and personal risks of this legislation.

“[This legislation] could mean we go to jail or have to close our clinic.”

(Texas)

“These laws could radically change my job, since providing transgender care is a significant part of my clinical practice and research.”

(Missouri)

“I have considered leaving my state to practice in a more tolerant area.”

(Montana)

Other providers described how this legislation would force them choose between their professional code of ethics and their livelihood, specifically their oath to “do no harm.”

“It would also jeopardize physicians’ ethical and moral stands as the law would criminalize evidence-based medicine.”

(Hawaii)

Some noted that protestors have sent them hate mail or picketed outside their clinics since these bills have been introduced, which makes them uncertain about their ability to practice medicine safely.

“There are emails on our listserv about protesters coming to children’s hospitals, or people receiving hate mail. I am somewhat scared to enter the public eye. Even to be an advocate - it makes me not want to put myself out there. I do not have fear for overt harm to myself or my family, but there is definitely a feeling of unease knowing that the world has some extreme people, many of whom have guns.”

(Illinois)

“Others in our clinic (and colleagues in the state) have been subject to harassment, protests, and threats - I know that it will only be a matter of time before I am also targeted. I worry about the safety of my family especially if things like addresses or phone numbers become publicly available (which has happened to a colleague).”

(California)

These bills were also described as creating emotional stress. One provider in North Carolina called this legislation “anxiety provoking,” while another from South Carolina said, “These proposed laws have created an emotional burden.” Others noted anxiety from the uncertainty and fears of losing their license for providing evidence-based care.

A few of the providers stated that this legislation would not affect their practice greatly because they were from a state that was unlikely to pass such legislation or because the majority of their patients were over the age of 18. Providers who believed this legislation was unlikely to become law in their states said they expected to see an increase in out-of-state patients if bordering states enact bans. Additionally, providers described the burden this legislation would place on their practices such as hiring lawyers to review their current processes, learning the laws in every state in which they practice, or hiring behavioral health staff to help TGDY who experience mental distress due to the mandated withdrawal of gender-affirming care.

Discussion

Given the critical role providers play in the provision of gender-affirming care to TGDY, our study sought to understand their perspectives on state legislation that seeks to ban this care. We were particularly interested in the perspectives of providers who practice gender-affirming care with TGDY as they could be held civilly or criminally liable for providing this care should this legislation become law in states they practice [14–20].

Many providers described legislation banning gender-affirming care for TGDY as conflicting with the standards of care outlined by the American Academy of Pediatrics [1] and the Endocrine Society [2] and felt that their profession was being needlessly politicized by state governments. Many described this legislation as creating ethical dilemmas, particularly choosing between upholding their oath to “do no harm” or to follow the law. Some providers in states that had introduced this legislation even noted that they had considered moving to a state that would not ban such care, but feared leaving their current patients behind. Providers moving from states that have proposed or passed this legislation would further compound previously identified challenges in accessing providers with training in supporting TGDY and their families [24–26].

Providers’ perspectives on the effect of legislation banning gender-affirming care would have on TGDY are similar to those of parents and guardians of TGDY, particularly that this legislation would increase the risk of suicide, suicidal ideation, and self-harm among TGDY [27]. Already, TGDY experience significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide compared to non-TGDY peers [4,9]. Like parents and guardians [27], providers also believed that laws banning gender-affirming care for TGDY would increase discrimination against TGDY because they fuel a toxic societal environment that perpetuates bullying, demeaning, and harming TGDY. Prior studies described how this population already faces stigma in school and other parts of public life [29] and participants in this study emphasized that this legislation would only serve to further stigmatize and exclude TGDY.

Providers described the severe negative impacts this legislation would have on their professional and personal lives, noting particularly detrimental consequences for provision of services (pediatric, adolescent, endocrinological) to medically under-served communities. Some providers described how this legislation would shut down their clinic and others said that this legislation would radically change their practice because they see a substantial number of TGDY. Several participants noted this legislation would require them to hire lawyers to consider how to continue to provide care. This legislation was described as causing significant psychological distress for providers themselves. For example, one provider who practices in a state that has introduced this legislation said they felt their ability to practice medicine freely in their state could be stripped away at any moment, causing them undue stress. Similar to reproductive health providers’ perspectives on abortion [30], participants described feeling an increasing stigma associated with their work that made them consider stopping gender-affirming care altogether. In general, providers felt this legislation makes them fearful to practice, or lose the ability to practice, evidence-based medicine. To counter these legislative efforts, many providers encouraged professional medical associations and medical experts to speak out against these efforts, as well as other legislation that restricts access to life-saving interventions. This approach has had mixed success in the context of legislation banning gender affirmation medical care for minors, as it led Governor Asa Hutchinson to veto Arkansas’s bill that ultimately went into effect [31]. However, there have been successes in other areas such as abortion [32] and naloxone to prevent opioid overdoses [33].

The major limitation of the study was that our sample was overwhelmingly white and most identified as cisgender women. Future research is needed to understand the perspectives of providers of color and those who are trans identified. Despite this limitation, this work builds on that of Kidd et al. [27] and is the first of our knowledge to capture the perspectives of providers regarding legislation that bans gender-affirming care for TGDY. Results from this geographically diverse sample indicated national agreement on both the importance of gender-affirming care for TGDY and the fear of negative health outcomes for TGDY if legislation restricts access to this care. Future research should focus on measuring the effects these legislative efforts have on the mental and physical health of trans youth in states where these bills are introduced and passed. Quantitative data would be particularly useful in assessing the effects of these legislative efforts.

Conclusions

Providers overwhelmingly believed that legislation banning gender-affirming care for TGDY would lead to increased mental health problems among TGDY, particularly suicide. Furthermore, most providers viewed this legislation as interfering with their practice of evidence-based medicine and for many causing severe distress and potentially threatening their livelihood. Our findings emphasize the need for lawmakers to hear from pediatric medical experts and continued advocacy by professional organizations that represent pediatric providers on state and national levels to ensure that access to evidence-based, life-saving gender affirming care for TGDY will be improved rather than decreased across the U.S.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

Despite current standards of care, several states have introduced legislation that would ban gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. This study found that providers overwhelmingly opposed this legislation, believing it would worsen mental health and increase the risk of suicide among transgender youth, while interfering with their ability to practice evidence-based medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the providers who participated in this study, as well as Drs. Shelby Davies and Jeffrey Eugene, as well as physicians from UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh for their feedback on the survey. Listed above is everyone who contributed significantly to the work. This work was supported by the Graduate Student Research Grant Fund from the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan. Dr. Kidd was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science of the NIH, Award Number TL1TR001858 (PI Kraemer). Dr. Dowshen’s work is supported by the Stoneleigh Foundation. The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest with the organization that sponsored the research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Rafferty J, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Adolescence, et al. Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20182162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: An endocrine society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:3869–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend 2012;13:165–232. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Turban JL, King D, Carswell JM, et al. Pubertal suppression for transgender youth and risk of suicidal ideation. Pediatrics 2020;145:e20191725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].de Vries ALC, Steensma TD, Doreleijers TAH, et al. Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: A prospective follow-up study. J Sex Med 2011;8:2276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Costa R, Dunsford M, Skagerberg E, et al. Psychological support, puberty suppression, and psychosocial functioning in adolescents with gender dysphoria. J Sex Med 2015;12:2206–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Allen LR, Watson LB, Egan AM, et al. Well-being and suicidality among transgender youth after gender-affirming hormones. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 2019;7:302–11. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Salas-Humara C, Sequeira GM, Rossi W, et al. Gender affirming medical care of transgender youth. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2019;49:100683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Toomey RB, Syvertsen AK, Shramko M. Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20174218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].van der Miesen AIR, Steensma TD, de Vries ALC, et al. Psychological functioning in transgender adolescents before and after gender-affirmative care compared with cisgender general population peers. J Adolesc Health 2020;66:699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].de Vries ALC, McGuire JK, Steensma TD, et al. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics 2014;134:696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Legislative tracker: Anti-transgender medical care bans. Washington, D.C.: Freedom For All Americans; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Janssen A, Voss R. Policies sanctioning discrimination against transgender patients flout scientific evidence and threaten health and safety. Transgend Health 2021;6:61–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].S.B. 442, 101st gen. Assemb. (Mo. 2021) n.d.

- [15].H.B. 4047, 124th Sess. Gen. Assemb., 1st Reg. Sess. (S.C. 2021) n.d.

- [16].S.B. 10, 2021 Reg. Sess. (Ala. 2021) n.d.

- [17].S.B. 2171, 136th Leg. Sess. (Miss. 2021) n.d.

- [18].H.B. 68, 1st Year, 167th Sess. Of the gen. Court (N.H. 2021) n.d.

- [19].S.B. 224, 122nd gen. Assemb., 1st Reg. Sess. (Ind. 2021) n.d.

- [20].S.B. 1646, 87th Leg. (Tex. 2021) n.d.

- [21].Sulaski Wyckoff A. State bills seek to place limits on transgender care, ‘punish’ physicians. AAP News 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [22].WPATH. Statement in response to proposed legislation denying evidence-based care for transgender people under 18 years of age and to penalize professionals who provide that medical care. n.d.

- [23].American Medical Association. State advocacy update 2021.

- [24].Eisenberg ME, McMorris BJ, Rider GN, et al. “It’s kind of hard to go to the doctor’s office if you’re hated there.” A call for gender-affirming care from transgender and gender diverse adolescents in the United States. Health Soc Care Community 2020;28:1082–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gridley SJ, Crouch JM, Evans Y, et al. Youth and caregiver perspectives on barriers to gender-affirming health care for transgender youth. J Adolesc Health 2016;59:254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pampati S, Andrzejewski J, Steiner RJ, et al. “We deserve care and we deserve competent care”: Qualitative perspectives on health care from transgender youth in the Southeast United States. J Pediatr Nurs 2021;56:54–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kidd KM, Sequeira GM, Paglisotti T, et al. “This could mean death for my child”: Parent perspectives on laws banning gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2021;68:1082–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval 2006;27:237–46. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, et al. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: Exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. J Adolesc Health 2006;38:230–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Norris A, Bessett D, Steinberg JR, et al. Abortion stigma: A reconceptualization of constituents, causes, and consequences. Womens Health Issues 2011;21:S49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hutchinson A. Why I vetoed my party’s bill restricting health care for transgender youth. The Washington Post; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [32].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Increasing access to abortion. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 815. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136: 107–15. [Google Scholar]

- [33].S.B. 406, 119th gen. Assemb., 1st. Reg. Sess. (Ind. 2015) (enacted as Pub. L. No. 156–2014) n.d.