Abstract

The population composition and biogeochemistry of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) in the rhizosphere of the marsh grass Spartina alterniflora was investigated over two growing seasons by molecular probing, enumerations of culturable SRB, and measurements of SO42− reduction rates and geochemical parameters. SO42− reduction was rapid in marsh sediments with rates up to 3.5 μmol ml−1 day−1. Rates increased greatly when plant growth began in April and decreased again when plants flowered in late July. Results with nucleic acid probes revealed that SRB rRNA accounted for up to 43% of the rRNA from members of the domain Bacteria in marsh sediments, with the highest percentages occurring in bacteria physically associated with root surfaces. The relative abundance (RA) of SRB rRNA in whole-sediment samples compared to that of Bacteria rRNA did not vary greatly throughout the year, despite large temporal changes in SO42− reduction activity. However, the RA of root-associated SRB did increase from <10 to >30% when plants were actively growing. rRNA from members of the family Desulfobacteriaceae comprised the majority of the SRB rRNA at 3 to 34% of Bacteria rRNA, with Desulfobulbus spp. accounting for 1 to 16%. The RA of Desulfovibrio rRNA generally comprised from <1 to 3% of the Bacteria rRNA. The highest Desulfobacteriaceae RA in whole sediments was 26% and was found in the deepest sediment samples (6 to 8 cm). Culturable SRB abundance, determined by most-probable-number analyses, was high at >107 ml−1. Ethanol utilizers were most abundant, followed by acetate utilizers. The high numbers of culturable SRB and the high RA of SRB rRNA compared to that of Bacteria rRNA may be due to the release of SRB substrates in plant root exudates, creating a microbial food web that circumvents fermentation.

Temperate salt marshes are among the most productive ecosystems on Earth with carbon fixation rates exceeding 1,000 g of C m−2 year−1 (50). A large portion of this carbon is decomposed within marsh sediments, and sulfate (SO42−) reduction accounts for more than half of this decomposition (24). The presence of a dense root or rhizome system in salt marsh sediments and the ability of this root system to deliver organic materials and oxidants below ground produce a dynamic subsurface redox biogeochemistry capable of supporting steep chemical gradients and a diverse microflora (18). Hence, the rhizosphere is an ideal microhabitat for bacterial proliferation and is important for plant health.

The dynamics of interactions between the salt marsh rhizosphere and bacteria can be regulated strongly by plant growth stage and the release of materials from roots. Organic matter supplied as root exudates may account for the majority of growing season SO42− reduction in salt marsh sediments (22). Changes in plant growth, i.e., initiation of active elongation (vegetative growth) and commencement of reproduction, affect SO42− reduction in sediments inhabited by the common cordgrass Spartina alterniflora (18, 22). Therefore, the marsh is a habitat with high rates of microbial activity that are strongly affected by plant activities.

Considerable effort has been devoted to studies of SO42− reduction in salt marsh sediments (15, 22, 25, 26). However, populations of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and how they might change in response to plant activity are not well known. Molecular approaches, especially those using phylogeny-based methods, offer the ability to investigate bacterial population dynamics of specific phylogenetic groups which often share physiological traits. The 16S rRNA phylogeny of the SRB is well described, and hybridization probes which target each of the known major SRB groups and several individual species have been developed (10, 11). These phylogenetic groups correspond with distinct physiological assemblages (11), so rRNA-based methods can provide information on the types of electron donors that might be used by SRB in the S. alterniflora rhizosphere. The present study was conducted to characterize SO42− reduction and SRB populations in the rhizosphere of S. alterniflora by utilizing hybridization probing techniques together with activity and enumeration approaches. The site chosen for the work was a marsh that we had studied in detail previously and which provided a fundamental baseline of information on the distribution of bacterial activity rates (19, 22), geochemistry (18, 22, 44, 61, 62), and diversity of SRB (47, 48).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site.

Samples were collected for 18 months (two growing seasons) from 1993 to 1994 from a tall-form (2.0-m), creekside stand of S. alterniflora in Chapman’s Marsh in southeastern New Hampshire (22). The tall form was studied because this actively growing form is capable of releasing larger quantities of O2 and dissolved organic carbon from roots than the short form (22). In addition, during reproductive periods, all of the tall-form culms simultaneously produce reproductive organs, while only about 30% of the culms in the short-form stands do so (29). Hence, the tall form was best suited for an investigation of the effects of changes in plant growth stage on below-ground microbial activity. The sediments were organically rich, i.e., composed primarily of living and dead plant roots and rhizomes, but they also contained detrital clay and silt-sized particles delivered from upstream terrestrial sources. To avoid disturbing the vegetation and sediment, boardwalks were used to access sampling sites.

Sample handling.

Sediment cores (5-cm diameter) were collected by using a handheld corer with a polycarbonate liner (47). Cores were flushed with N2 immediately after collection, capped, and held anoxically on ice for transport to the laboratory. Cores were either processed within 1 to 2 h of sample collection (for rate and most chemical analyses) or stored at −80°C until used for further manipulations (for RNA extractions). Samples for enumeration of SRB by culturing techniques were shipped cold overnight to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency laboratory in Gulf Breeze, Fla. All handling in the laboratory was conducted anoxically.

Pore water samples for sulfate analyses were collected with in situ sippers (22), which were deployed during the spring each year and removed in the fall prior to ice formation. These devices did not cause any unusual sediment erosion. Pore water samples were collected, filtered, and dispensed anoxically within 1 or 2 min in the field. Because the sippers were left in place for several months at a time, we were able to study temporal changes at several exact locations. In addition, the placement of the sippers prior to plant growth in the spring allowed for nondestructive sampling that prevented artifacts due to root damage (22, 27).

Sulfate reduction.

Rates of SO42− reduction (SRR) were determined by a 35S reduction assay using chromium (21). Briefly, duplicate sediment cores were sliced into sections in a N2-filled glove bag and portions were placed into 5-ml plastic syringes which were sealed with serum stoppers. Syringes and stoppers were preincubated for 2 weeks under N2 to prevent diffusion of O2 into samples (6). Subsamples were not homogenized prior to use. One μCi of 35SO42− was injected into each syringe, and samples were incubated in a dark N2-filled jar overnight at ambient temperature. Activity was stopped by freezing to −80°C. The concentration of 35S present in dissolved sulfide, acid-volatile sulfides, pyrite, and elemental sulfur was determined by reducing these chemical species to sulfide with reduced acidic chromium (21).

rRNA extraction and hybridization.

Nucleic acids were extracted from bulk sediments collected over 18 months from three depths: 0 to 2, 2 to 4, and 6 to 8 cm. During the second year (1994), cores were also sliced in half vertically, the upper two depth sections in one half of the core were combined, and the sediment was removed by gentle rinses with salinity-adjusted buffer (47). The rinsed roots were considered rhizosphere samples that contained bacteria closely associated with or attached to root material. RNA was extracted from all sediments and rhizosphere samples by a bead-beating technique (13, 47), and nucleic acids were further purified with Sephadex G25 spin columns (43).

RNA was denatured by adding 3 volumes of 2% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) to 1 volume of RNA extract and incubating at room temperature for 10 min (55). Denatured RNA was then diluted with sterile distilled H2O containing 0.0002% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue and 1 μg of poly(A) ml−1. Using a slot blot device (Minifold II; Schleicher and Schuell, Inc., Keene, N.H.) under slight vacuum, the various dilutions of sample and standard RNAs (in a volume of 100 μl) were applied to Immobilon-N membranes (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) that had been prewetted in 95% (vol/vol) ethanol and rinsed in distilled H2O. Membranes were then dried at room temperature and baked at 80°C for 1 h prior to prehybridization and subsequent hybridization (56).

Oligonucleotide probes were end labeled with 32P (13), purified with Nensorb 20 cartridges (Dupont Corp., Wilmington, Del.) (55), and hybridized at 40°C overnight. After the membranes were washed (56) (washing temperatures given in Table 1), they were air dried briefly and the amount of probe was quantified with a gas proportional radioisotope detection system (Ambis, Inc., San Diego, Calif.).

TABLE 1.

16S rRNA oligonucleotide probes and target groups

| Target | Probe | Probe sequence | Target sitea | Wash temp (°C) | Reference RNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desulfobacteriaceae family | 804b | CAACGTTTACTGCGTGGA | 804–821 | 46 | Desulfobotulus sapovorans |

| Desulfobacterium vacuolatum | |||||

| Desulfovibrio spp. | 687b | TACGGATTTCACTTCCT | 687–702 | 45 | Desulfovibrio piger |

| Desulfovibrio vulgaris | |||||

| Desulfobulbus spp. | 660b | GAATTCCACTTTCCCCTCTG | 660–679 | 59 | Desulfobulbus elongatus |

| Desulfobulbus propionicus | |||||

| Bacteria domain | 338c | GCTGCCTCCCTAGGAGT | 338–354 | 48 |

Two sets of hybridization membranes were used for slot blot analysis (55). One membrane was hybridized with a probe specific for a particular bacterial group or genus, while the other utilized a general probe designed to hybridize with 16S rRNA of almost all species in the domain Bacteria (EUB338) (56) (Table 1). The specific probes utilized were SRB probes 687 (primarily the family Desulfovibrionaceae), 660 (Desulfobulbus spp.), and 804 (most members of the family Desulfobacteriaceae). In addition, several samples collected during the first few months of the 1993 season were analyzed with probes that target phylogenetic groups within the Desulfobacteriaceae, including probes 129 (Desulfobacter spp.), 221 (Desulfobacterium spp.), and 814 (Desulfosarcina, Desulfococcus, and Desulfobotulus spp.) (13). Samples were added to membranes at three concentrations, with 50 to 200 ng per slot used for membranes assayed with the Bacteria probe and 600 to 1,800 ng per slot used on membranes for specific probes. Membranes assayed with the specific probes received reference rRNA extracted from pure cultures (Table 1) at a range of ∼0.78 to 25 ng per slot to generate a standard curve. Membranes hybridized with the general Bacteria probe (EUB338) received ∼1.56 to 200 ng per blot of reference rRNA that was the same reference material used for the specific probes.

The relative abundances (RA) of the specific probe targets as a function of total Bacteria rRNA were determined by first quantifying radioactive signal per slot and correcting for background. Next, the following equation was used to calculate RA: RA (percent) = [(mss × m sr)/(mes × mer)] × 100, where mss is the slope of specific probe signal per unit of sample rRNA, msr is the slope of the specific probe signal per unit of reference rRNA, mes is the slope of the Bacteria probe signal per unit of sample rRNA, and mer is the slope of the Bacteria probe signal per unit of reference rRNA (16). Samples for which the slope of probe signal per unit of rRNA was not linear (i.e., r2 < 0.90) were omitted from analyses.

MPN analyses.

SRB in sediment cores were enumerated by the most-probable-number (MPN) technique. Three types of samples were analyzed: bulk sediments from the top 3 cm and from a depth of 12 to 15 cm and the rhizosphere of the top 3 cm. Duplicate cores were aseptically extruded and cut horizontally, and sections were separated with a sterile razor in an anaerobic glove box. The section from the upper 3 cm was also cut vertically to provide subsamples for rhizosphere analysis. Sections from duplicate cores were combined, weighed, and transferred to a sterile Waring blender inside an anaerobic chamber. The medium of Widdel and Pfennig (64), without Na2SO4 or an electron donor, was used to rinse residual sample into the blender and to prepare a 10−1 dilution (wt/vol) of the sediments. This dilution was homogenized by blending for 5 min, and the homogenate was aseptically transferred to a sterile serum bottle, sealed, and reduced. This dilution was the inoculum for a triplicate MPN dilution series (10−2 to 10−9) in tubes sealed with serum stoppers. To prepare rhizosphere samples, the half-core duplicate sections from the upper 3 cm were combined and aseptically rinsed by gently immersing in a series of beakers containing the sterile rinse medium (100 ml) until all visible sediment was removed. The rinsed roots were weighed, and a 10−1 dilution was prepared as described above.

The medium of Widdel and Pfennig (64) prepared as described previously (52) was used for MPN determination. The salinity of the medium was adjusted to that of the overlying marsh water at the time of sampling with the addition of NaCl and MgCl · 6H2O in appropriate ratios (64). The completed medium contained one of the following electron donors: acetate, 20 mM; ethanol, 20 mM; benzoate, 5 mM; butyrate, 10 mM; malate, 10 mM; or propionate, 10 mM. All incubations were at 20°C. Growth was determined as the increase in optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm. Sulfate removal was confirmed by ion chromatography (51). Tubes showing both growth and SO42− consumption were considered positive and used to calculate the abundance of SRB per gram of sample.

RESULTS

Sulfate reduction.

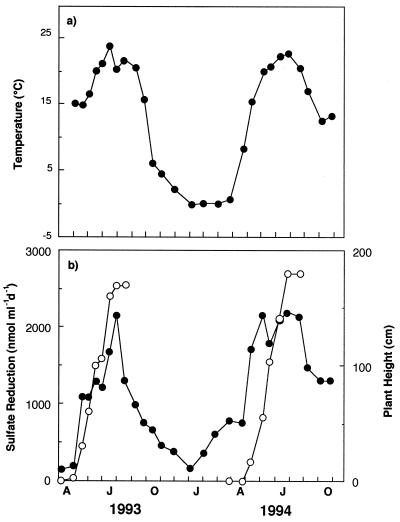

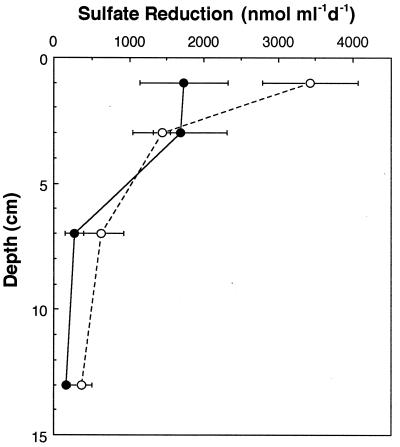

Temperatures in surficial marsh sediments displayed a typical seasonal cycle with highs near 25°C in summer and below 0°C in winter (Fig. 1a). In general, SRR followed the seasonal temperature, with low rates in winter and very high rates at over 2,000 nmol ml−1 day−1 in summer (Fig. 1b). However, temporal changes in SRR corresponded better with changes in plant growth than with temperature, i.e., SRR increased rapidly at the commencement of vegetative growth (aerial elongation) and decreased upon the initiation of reproductive growth (flowering) in late July. This phenomenon was noted previously in this marsh (22). In 1993, plant growth displayed a bimodal pattern in which aerial growth slowed in the middle of the season (late June to early July) and then increased again. The SRR displayed a similar bimodal pattern that year (Fig. 1b). In 1994 when plant growth was continuous, SRR increased rapidly upon the initiation of plant growth and remained high until mid-August. SRR were most rapid near the sediment surface where activities reached ∼3,500 nmol ml−1 day−1 in July (Fig. 2). Rates below 5 cm were generally <500 nmol ml−1 day−1.

FIG. 1.

(a) Sedimentary temperature and (b) plant height (○) and SRR (●) in marsh sediments over time. Rates are averages of data from the upper 0- to 2-cm and 2- to 4-cm depths. The data are plotted over time for two growing seasons (in 1993, April [A], June [J], and October [O] are shown; in 1994, January [J], April [A], June [J], and October [O] are shown in the x axis).

FIG. 2.

Depth profiles of SRR in marsh sediments in July 1993 (●) and July 1994 (○).

Application of probes to environmental rRNA.

Selected samples were analyzed for variability in the probe assay by comparing (i) triplicate cores, (ii) cores that were divided into two sections vertically, and (iii) individual rRNA samples analyzed two or three times. These comparisons showed that variability was usually less than 10% and often less than 5% of the mean (data not shown). This variability increased to as much as 21% in a few cases where the signal was weak and the RA was low.

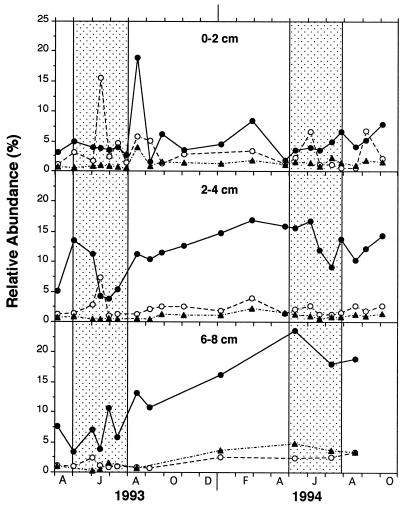

The sum of the probe data for rRNA from Desulfovibrio (probe 687), Desulfobacteriaceae (probe 804), and Desulfobulbus (probe 660) accounted for up to ∼30% of the total Bacteria rRNA in the marsh sediments (Fig. 3). Some of the highest RAs were noted in winter. The highest RAs occurred in the deepest samples (6 to 8 cm), which in 1994 accounted for 30% of the Bacteria rRNA. This depth yielded much higher values in 1994 than during the previous year. However, samples from 6 to 8 cm were not analyzed during each sampling period. In general, the lowest RAs were noted in surficial samples (0 to 2 cm), yet these still accounted for ∼5 to 12% of the total Bacteria rRNA throughout the study period. The data for 0 to 2 cm were the most variable and displayed two large maxima during the summer of 1993. RA at the 2- to 4-cm depth interval displayed smoother trends that included a decrease during the middle of the growing season in both years. Other than this two- to fourfold decrease in RA at 2 to 4 cm, dramatic changes in RA corresponding to plant growth variations were not observed in bulk sediment samples despite the fact that SRR did vary greatly (Fig. 1).

FIG. 3.

Temporal changes at three depths in the RA of species of Desulfobacteriaceae (probe 804) (●), Desulfobulbus (probe 660) (○), and Desulfovibrio (probe 687) (▴) in marsh sediments. Stippled area indicates period of plant vegetative growth. The data are plotted over time for two growing seasons (in 1993, April [A], June [J], August [A], October [O], and December [D] are shown; in 1994, February [F], April [A], June [J], August [A], and October [O] are shown on the x axis).

The Desulfobacteriaceae accounted for up to 25% of the Bacteria rRNA and exhibited a much higher RA than the Desulfovibrio and Desulfobulbus spp. (Fig. 3). The abundance of the Desulfobacteriaceae rRNA was most pronounced below the upper 2 cm where it was usually 10- to 20-fold higher than the other groups. The Desulfovibrio rRNA was poorly represented in all samples and accounted for less than 1 to 2% of the Bacteria rRNA, while the Desulfobulbus rRNA generally represented from 1 to 5%. In the middle of both growing seasons, the RA of the Desulfobacteriaceae rRNA from sediments 2 to 4 cm down decreased significantly (Fig. 3). The Desulfobulbus rRNA increased during this same period in 1993 from sediments 0 to 2 and 2 to 4 cm down and in sediments 0 to 2 cm down in 1994. The signals from probes 129, 221, and 814 were too low to accurately quantify in many instances and, when summed, represented a small portion of the RA of the Desulfobacteriaceae.

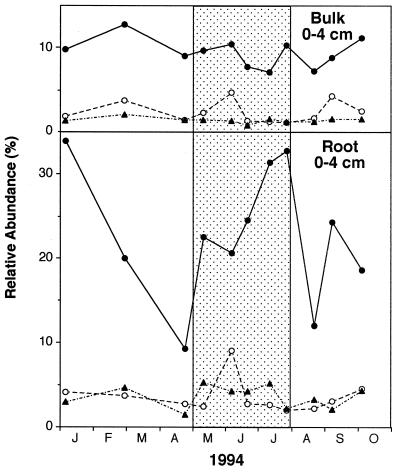

Root-associated SRB exhibited higher RAs than did samples of bulk sediments, with the former accounting for up to 40% of the Bacteria rRNA (Fig. 4). The data in Fig. 4 are compared to the average for the data from the upper 0 to 2 and 2 to 4 cm combined, since subsamples for root analyses consisted of the 0- to 4-cm depth interval. The RA of root-associated Desulfobacteriaceae dominated the SRB, as was noted for bulk sediment samples. However, in contrast to bulk sediment, the RA of the root-associated SRB increased during vegetative growth. This was seen most clearly for the Desulfobacteriaceae (probe 804), which increased nearly fourfold to over 30%.

FIG. 4.

Temporal changes in the RA of species of Desulfobacteriaceae (probe 804) (●), Desulfobulbus (probe 600) (○), and Desulfovibrio (probe 687) (▴) both in bulk sediments and on roots. Stippled area indicates period of plant vegatative growth. The data are plotted over time for most of 1994 as follows: January (J), February (F), March (M), April (A), May (M), June (J), July (J), August (A), September (S), and October (O).

Enumeration of SRB by MPN.

SRB physiological types were enumerated in sediment and isolated rhizosphere samples on three occasions during 1993. In addition, the upper 2 cm of sediment was assayed similarly in April 1994 (Table 2). Electron donors were chosen as those that might be released by roots (e.g., ethanol and malate [42]) or produced by anaerobic cellulolytic microorganisms (7). In almost all cases, the highest numbers of SRB were recovered with ethanol-containing medium with abundances reaching nearly 5 × 107 g−1 (wet weight). In fact, ethanol-utilizing SRB outnumbered the other types by nearly an order of magnitude in most instances. The second most abundant group was the acetate-utilizing species which were usually greater than 106 g−1, followed by butyrate utilizers, which reached 2.5 × 106 g−1.

TABLE 2.

Abundance of SRB in marsh sediments determined by the MPN method with various growth substrates

| Soil and month | SRB abundancea (no. g−1) with the following growth substrate:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Acetate | Benzoate | Malate | Propionate | Butyrate | |

| Bulk soil (0–3 cm) | ||||||

| June | 1.4 × 107 | 9.7 × 105 | 9.7 × 105 | 4.6 × 104 | 3.1 × 105 | 7.6 × 105 |

| August | 4.6 × 107 | 4.6 × 106 | 9.7 × 104 | 1.5 × 105 | 1.5 × 105 | 2.5 × 106 |

| October | 2.5 × 107 | 2.5 × 106 | 4.4 × 104 | 3.9 × 103 | 2.5 × 106 | 2.5 × 105 |

| April | 4.0 × 107 | 6.7 × 104 | 2.2 × 105 | NDb | 1.3 × 109 | 1.1 × 106 |

| Root associated (0–3 cm) | ||||||

| June | 1.4 × 107 | 2.4 × 106 | 3.0 × 105 | 2.5 × 104 | 4.5 × 105 | 4.5 × 105 |

| August | 2.5 × 107 | 4.5 × 106 | 9.4 × 104 | 1.4 × 104 | 2.5 × 105 | 2.5 × 106 |

| October | 4.5 × 107 | 2.5 × 106 | 3.0 × 104 | 4.0 × 103 | 7.5 × 105 | 1.5 × 105 |

| Bulk soil (12–15 cm) | ||||||

| June | 1.4 × 107 | 9.7 × 105 | 2.6 × 105 | 2.6 × 106 | 2.6 × 105 | 9.7 × 105 |

| August | 4.6 × 107 | 1.5 × 106 | 4.6 × 104 | 7.6 × 104 | 2.6 × 105 | 9.7 × 104 |

| October | 1.5 × 106 | 2.5 × 106 | 2.5 × 104 | 4.0 × 103 | 2.0 × 104 | 7.0 × 103 |

The error in the estimates is approximately 80% of the mean.

ND, not determined.

In June 1993, surficial sediments (0 to 3 cm), deeper sediments (12 to 15 cm), and roots rinsed free of sediment contained similar numbers of SRB on a weight basis (Table 2). Acetate-utilizing SRB were slightly higher in root samples at 2.4 × 106 g−1 compared to 1 × 106 g−1 in bulk sediments. In August, acetate-utilizing SRB were threefold more abundant in surficial sediments and on roots than in the deeper sediment samples. Butyrate-utilizing SRB were also more abundant in surficial sediments in August and displayed a sharp decrease in deeper sediments. Propionate-utilizing SRB were relatively low in all samples at 105 to 106 g−1 but did not show a significant decrease in abundance with depth, as was seen for many of the other SRB groups. In October, ethanol-, propionate-, and butyrate-utilizing species decreased with depth by about a factor of 10, while acetate and benzoate utilizers did not decrease.

DISCUSSION

Sulfate reduction.

The seasonal changes in the biogeochemical conditions in marsh sediments followed changes in plant growth activity and physiology as inferred previously by other studies in this marsh (18, 19, 22). SO42− reduction activity responded rapidly to changes in plant physiology. During active vegetative growth, SO42− reduction was rapid, whereas commencement of plant flowering near the end of July each year resulted in sharp decreases in rate. A likely explanation for this was that during vegetative growth, plants leaked dissolved organic compounds into the sediment, fueling anaerobic bacterial metabolism (22). This process ceases upon flowering as plants allocate carbon to reproductive organs (39). It is also possible that bacterial activity was inhibited by release of organic compounds (phenolic compounds) with bacteriostatic properties (3, 9). Blaabjerg et al. (1) noted a similar finding that a significant portion of the SO42− reduction activity in the rhizosphere of the sea grass Zostera marina was fueled by organic exudates rather than by sedimentary organic matter. SRR in the marsh were extremely high and similar in magnitude to those reported for microbial mats (57, 60).

SRB RA.

SRB rRNA comprised a very large percentage of Bacteria rRNA in marsh sediments throughout both 1993 and 1994. One would not expect SRB to dominate Bacteria, since SRB are situated at the terminal end of the decomposition hierarchy where they use end products of other bacteria for energy and growth (45, 54, 63). Devereux et al. (12), using methodology identical to that used here, reported that SRB accounted for <3% of the Bacteria in an unvegetated marine sediment. Trimmer et al. (58) found that <3.5% of the Bacteria rRNA in an estuarine sediment was attributable to SRB, but they did note SRB RA as high as 12% in brackish sediment (salinity, <1.3%). Purdy et al. (46) utilized probe techniques and reported that SRB comprised a relatively minor portion of the bacteria in estuarine sediment slurries. Because the methods used here measured rRNA RA and not cell numbers, the high SRB RA in marsh sediments indicated that SRB were either unusually abundant compared to other bacteria or were more active on a per cell basis and contained more rRNA. The marsh sediments exhibited SRR that were approximately an order of magnitude higher than those determined by Devereux et al. (12) and Trimmer et al. (58). However, high rates alone do not necessarily explain high SRB RA, since the latter represents the proportion of Bacteria rRNA that is from SRB which is a function of the microbial food web configuration.

An explanation for the high relative proportion of SRB rRNA in the marsh sediments is that a portion of the substrates utilized directly by SRB, i.e., fermentation products, were provided directly by roots during root fermentation activity. We did note active alcohol dehydrogenase activity by root tissues (unpublished data) which would provide ethanol for use by SRB (41, 42). S. alterniflora roots also produce malate (41) and perhaps acetate (19). Hence, SRB using these root exudates would not require a synergistic relationship with fermentative bacteria. In addition, other types of substrates released from roots, such as carbohydrate monomers (38), would require a less diverse bacterial consortium to degrade them compared to that needed to degrade solid-phase and polymeric compounds. Such a simplified food web would permit SRB to be a larger proportion of the bacterial community. This premise is supported by the finding that root-associated SRB displayed a higher RA than SRB in bulk sediments (Fig. 4). In addition, Purdy et al. (46) noted increases over time in the RA of SRB in sediment slurries amended with SRB electron donors, which underscores the above premise.

The RA and composition of SRB in bulk sediment samples did not vary greatly in response to plant growth stage despite the changes in SRR. One would assume that the rapid increases and decreases in SRR, which were noted during the commencement of plant growth and immediately after flowering, would result from a change in the quantity and composition of substrates used by SRB. It has been noted previously in this marsh that the redox status of the sediment changes dramatically during the growing season due to rapid changes in the delivery of oxidants by roots (22). These changes could also cause a shift in the relative importance of particular physiological groups of SRB. However, probe data for bulk sediments displayed little variation throughout the year compared to SRR. Since the SRB RAs in the marsh were generally high, it appeared that the marsh harbored a large and active population of SRB that continued to dominate sediment bacterial biomass throughout the year, regardless of SO42− reduction and how rapidly it changed over time. In fact, the general increase in the RA of the SRB during winter suggested that the SRB were able to survive long periods of cold better than other bacteria in the marsh.

Probe data for bulk sediment samples did correspond with changes in plant growth on some occasions. In particular, the Desulfobacteriaceae at the 2- to 4-cm depth during both years decreased by as much as 75% in the middle of the vegetative growth period (Fig. 4). One explanation for this decrease is that the delivery of organic material and oxidants to sediments by plants enhanced the growth of other types of bacteria capable of taking advantage of the changing habitat. Although anaerobic bacterial activity increased greatly during vegetative growth due to dissolved organic carbon input, it has been shown in this marsh that S. alterniflora also supplies oxygen to the sediments simultaneously (22). O2 exudation (in conjunction with organic matter release) would favor growth of aerobic bacteria and other bacteria capable of using alternate electron acceptors such as metals and nitrate regenerated from subsurface redox cycling. Reduced S (solid and dissolved) in these sediments exhibited a sharp decrease in concentration in June 1993, indicating a significant increase in oxidant input (23a). That decrease corresponded exactly with the decrease in RA of the Desulfobacteriaceae. Since SRR increased greatly during summer, it is likely that total SRB rRNA also increased but that non-SRB rRNA increased even more, resulting in a decrease in SRB RA.

The RA of the Desulfobulbus spp. increased in June 1993 as the Desulfobacteriaceae decreased (Fig. 3). In fact, the highest RA noted for the Desulfobulbus spp. occurred in the 0- to 2- and 2- to 4-cm-deep sections in mid June. Apparently, members of this genus were stimulated by the increased introduction of O2, perhaps due in part to their ability to disproportionate S0 generated from the oxidation of reduced S in the subsurface (36).

In contrast to bulk sediments, the RA of all the root-associated SRB groups, especially the Desulfobacteriaceae group, increased greatly during active plant growth. We propose that exudation of organic matter from roots stimulated these SRB relative to other bacterial groups even though the opposite occurred in bulk sediments. Despite the summer increase in the RA of SRB on roots, the bulk of the total marsh SRB rRNA decreased during summer relative to total rRNA. However, root bacterial populations were unique in that a large portion of the total Bacteria rRNA was SRB rRNA and that this rRNA increased further when plants were growing above ground. This result was intriguing, since one would envisage that the root surface would be subjected to higher levels of O2 than the remaining sediment if O2 were released from roots. Our previous work in this marsh demonstrated that large quantities of O2 are released by roots during vegetative growth (22). One would anticipate that bacteria other than SRB would flourish on the root, causing the SRB to make up a smaller portion of the total Bacteria. The opposite result may be due to microcolonies of SRB on roots, which respond to organic exudates, and the fact that organic release is separated spatially from O2 release. If O2 exudation is due primarily to movement of air through plant tissue when pore water is being removed by transpiration at low tide (8), then it is conceivable that organic exudation would not necessarily occur at the same sites as passive O2 exudation. In addition, the metabolic activity of root-associated bacteria on a cell basis may be extremely high compared to bulk sedimentary bacteria, since the former are juxtaposed at the source of dissolved organic material. Hence, the root SRB may be capable of creating a microenvironment conducive to growth through rapid production of sulfide-causing abiotic removal of O2. Furthermore, root-associated bacteria may be better adapted to the strong biogeochemical gradients on roots by possessing the ability to metabolize O2 and other electron acceptors and the ability to use a larger array of substrates than their bulk sediment counterparts. High SRR have been reported in the oxic layers of microbial mats (5, 14).

The marsh SRB population was dominated by members of the Desulfobacteriaceae and to a lesser extent by Desulfobulbus spp. These results suggest that the Desulfobacteriaceae and Desulfobulbus spp. may be well adapted to the marsh because they are better suited for a habitat that tends to rapidly change temporally and spatially. For example, Desulfobulbus propionicus is capable of conserving energy for growth from the disproportionation of elemental sulfur (36) which is abundant in marsh sediments (37). Members of the Desulfobacteriaceae are capable of utilizing a diverse array of electron donors including formate, lactate, ethanol, acetate, C3 to C16 fatty acids (63), secondary alcohols such as 2-propanol and 2-butanol, isobutyrate (17), H2, fumarate, malate, and benzoate (63). Members of this group are capable of complete oxidation of organic carbon to CO2, and aerobic respiration has been reported (14). Such nutritional versatility could be advantageous in a complex environment such as the salt marsh sediment and rhizosphere.

The RA of Desulfovibrio spp. in comparison was low and accounted for less than 11% on average of the total SRB rRNA detected, with a maximum of 27%. In the brackish sediments studied by Trimmer et al. (58), Desulfovibrio spp. accounted for up to 90% of the detected SRB, while estuarine sediments contained ∼35 to 65%. Devereux et al. (12) noted that Desulfovibrio spp. were 49 to 68% of the SRB rRNA in shallow marine sediments. Perhaps Desulfovibrio spp. are better adapted to habitats that tend to be more reduced.

The increase with depth in the RA of members of the Desulfobacteriaceae contrasts with observations in subtidal unvegetated sediments where Desulfovibrio spp. exhibited an increase with depth (12). In fact, the highest RA of Desulfobacteriaceae in the marsh was found in the deepest sediments sampled (Fig. 4). Living S. alterniflora roots occur at the deepest depths sampled (2, 28, 30), so the roots may have been influential at those depths. However, even though SRB consisted of a large portion of the total Bacteria rRNA at these depths, the actual amounts of rRNA extracted from sediments below the surface were quite small. Hence, the actual SRB biomass at depth was at least 10-fold lower than at the surface (data not shown).

The hypothesis that dynamic biogeochemical cycling selects for the enrichment of the Desulfobacteriaceae is challenged by the fact that this group remains dominant throughout the year even when plants are inactive. Apparently, the rapid activity of specific SRB in the summer is sufficient to maintain the population even in winter when rates are orders of magnitude lower. We conducted a preliminary study in a plot where plants had died from deposition of wrack (dead plant material) and in which we had severed plant roots along the periphery down to >40 cm to prevent lateral root and rhizome growth. However, even these sediments harbored a SRB population that 2 years later had a composition similar to sediments inhabited by living plants (data not shown). The decrease in the RA of Desulfobacteriaceae during the growing season also indicated that the populations of the non-SRB that diluted the Desulfobacteriaceae did respond temporally to plant growth while the SRB apparently remained. Therefore, the finding that the Desulfobacteriaceae persisted at these depths and in winter may simply indicate their ability to survive longer than other bacteria.

Data from probes which target subgroups within the Desulfobacteriaceae (probes 129, 814, and 221) were barely detectable, indicating that unknown members of this family not targeted by these probes are important in marsh sediments. In fact, Rooney-Varga et al. (47) found an uncultivated organism closely related to Desulfococcus multivorans that accounted for 24 to 40% of the Desulfobacteriaceae rRNA in the same extracts described here. This percentage was higher than the sum of the results using probes 129, 814, and 221 indicating that unknown SRB species are important in marsh sediments.

Abundance of culturable SRB.

High numbers of culturable SRB were measured by the MPN technique, which is not surprising, considering the high SRR. SRB viable counts from other studies were much lower than those reported here, often by several orders of magnitude (53). Viable counting methods are considered to underestimate bacterial densities due to the inability of the growth medium to allow for growth of all members of the community. Although SRB counts by MPN methods often do not correlate well with SRR (53), there are studies that do show good correlation (23, 31, 33, 40, 49). In subtidal estuarine, marine, and lake sediments, SRB counts vary from 103 to 106 per ml of whole sediment (4, 20, 33, 35). The marsh sediments studied here consistently contained over 107 SRB per ml. These abundances are slightly greater than those reported for very active cyanobacterial mats (57). This result provides further evidence for the predominance of SRB in salt marsh sediments and supports the premise that these SRB use substrates provided by plants as root exudates.

Vester and Ingvorsen (59) reported much higher SRB MPNs when using media made from natural sediment or sludge compared to those using synthetic media. However, our measurements using synthetic media yielded similar or higher SRB numbers. When our data were compared to SRR in the marsh, we calculated specific SRR (qSO42−) of ∼10−14 mol of SO42− cell−1 day−1, which are similar to those reported for pure cultures (32), cyanobacterial mats (57), and for enrichment cultures using natural media (59). Therefore, our MPN estimations may be approaching the natural SRB densities but are likely still somewhat low.

SRB viable counts did not vary temporally with SRR. However, MPN data did agree with the RA of SRB determined with probes. Both methods revealed that SRB were abundant during periods when activity rates were low. These results underscore the premise that SRR may change dramatically in response to seasonal temperature and plant growth changes, yet the population composition and perhaps even the actual density of SRB may not change significantly throughout the year.

Densities of SRB on roots were similar in magnitude to those found in bulk sediments on a weight basis. However, root mass was minor compared to total sediment (<20%). Therefore, although the association of SRB with S. alterniflora roots is significant, the root-associated SRB probably accounted for less than 20% of the total sedimentary bacteria.

The ethanol-utilizing SRB outnumbered the other types on most occasions. Ethanol utilization is a trait found in many SRB groups including virtually all of the Desulfovibrio spp., Desulfobulbus spp., and many of the species of other groups (63). Members of the Desulfomicrobium and Desulfonema genera do not have this ability (10). S. alterniflora releases ethanol from roots when metabolizing anaerobically (42), and it is tempting to speculate that the high abundance of ethanol-utilizing SRB in the marsh sediments is a result of the preferential use of these exudates. However, MPN techniques may support growth of certain physiological types of SRB better than others (34). During the present study, pure cultures isolated from MPN tubes containing ethanol were always Desulfovibrio sp. even though two of the isolates were unique (48). Probe results demonstrated that Desulfobulbus spp. were generally more abundant than Desulfovibrio spp. (Fig. 4), yet MPN values for propionate-utilizing Desulfobulbus spp. were lower than those for corresponding desulfovibrios from ethanol-containing media (Table 2). One new Desulfobulbus species was isolated from a butyrate-containing MPN tube (48). Hence, it is likely that the high estimates of ethanol-utilizing desulfovibrios were simply due to the fact that ethanol-utilizing SRB (probably Desulfovibrio spp.) grew well in the MPN medium used, while the medium is less than optimal for Desulfobulbus spp. Acetate-utilizing enrichments and MPNs tend to grow slowly, so the fact that the acetate-utilizing SRB MPNs were relatively high (>106 ml−1) suggests that acetate-utilizing SRB are also a significant component of the marsh sediment and rhizosphere.

In conclusion, probe results demonstrated that SRB were abundant in marsh sediments and represented a high percentage of the bacteria present. Population abundance and composition did not vary temporally nearly as much as rates of activity did in response to changes in plant growth. However, SRB on root surfaces increased during plant vegetative growth while those in bulk sediments decreased. This variation suggested that release of dissolved organic material from roots is capable of stimulating a variety of bacterial groups throughout the sediment but especially rhizoplane SRB. The rapidly changing habitat in marsh sediments selects for members of the Desulfobacteriaceae, a metabolically versatile group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency cooperative agreement CR-820062 and the National Science Foundation Ecology Program grant DEB-9520272.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blaabjerg V, Mouritsen K N, Finster K. Diel cycles of sulphate reduction rates in sediments of a Zostera marina bed (Denmark) Aquat Microb Ecol. 1998;15:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum L K. Spartina alterniflora root dynamics in a Virginia marsh. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1993;102:169–178. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boon P I, Johnstone L. Organic matter decay in coastal wetlands: an inhibitory role for essential oil from Melaleuca alternifolia leaves? Arch Hydrobiol. 1997;138:433–449. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bussmann I, Reichardt W. Sulfate-reducing bacteria in temporarily oxic sediments with bivalves. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1991;78:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canfield D E, Des Marais D J. Aerobic sulfate reduction in microbial mats. Science. 1991;251:1471–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.11538266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carignan R, St. Pierre S, Gachter R. Use of diffusion samplers in oligotrophic lake sediments—effects of free oxygen in sampler material. Limnol Oceanogr. 1994;39:468–474. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colberg P J. Anaerobic microbial degradation of cellulose, lignin, oligonols and monomeric lignin derivatives. In: Zehnder A J G, editor. Biology of anaerobic microorganisms. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1988. pp. 333–372. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dacey J W H, Howes B L. Water uptake by roots controls water table movement and sediment oxidation in short Spartina alterniflora marsh. Science. 1984;224:487–490. doi: 10.1126/science.224.4648.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deanross D, Rahimi M. Toxicity of phenolic compounds to sediment bacteria. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1995;55:245–250. doi: 10.1007/BF00203016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devereux R, Delaney M, Widdel F, Stahl D A. Natural relationships among sulfate-reducing eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6689–6695. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6689-6695.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux R, He S-H, Doyle C L, Orklnad S, Stahl D A, LeGall J, Whitman W B. Diversity and origin of Desulfovibrio species: phylogenetic definition of a family. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3609–3619. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3609-3619.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devereux R, Hines M E, Stahl D A. S cycling: characterization of natural communities of sulfate-reducing bacteria by 16S rRNA sequence comparisons. Microb Ecol. 1996;32:283–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00183063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devereux R, Kane M D, Winfrey J, Stahl D A. Genus- and group-specific hybridization probes for determinative and environmental studies of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:601–609. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dilling W, Cypionka H. Aerobic respiration in sulfate-reducing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner L R, Wolaver T G, Mitchell M. Spatial variations in the sulfur chemistry of salt marsh sediments at North Inlet, South Carolina, J. Mar Res. 1988;46:815–836. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giovannoni S J, Britschgi T B, Moyer C L, Field K G. Genetic diversity in Sargasso Sea bacterioplankton. Nature. 1990;345:60–63. doi: 10.1038/345060a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen T A. Carbon metabolism of sulfate-reducing bacteria. In: Odom J M, Singleton R, editors. The sulfate-reducing bacteria: contemporary perspectives. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1993. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hines M E. The role of certain infauna and vascular plants in the mediation of redox reactions in marine sediments. In: Berthelin J, editor. Diversity of environmental biogeochemistry. Vol. 6. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1991. pp. 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hines M E, Banta G T, Giblin A E, Hobbie J E, Tugel J T. Acetate concentrations and oxidation in salt marsh sediments. Limnol Oceanogr. 1994;39:140–148. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hines M E, Buck J D. Distribution of methanogenic and sulfate-reducing bacteria in near-shore marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:447–453. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.2.447-453.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hines M E, Visscher P T, Devereux R. Sulfur cycling. In: Hurst C J, Knudsen G R, McInerney M J, Stetzenbach L D, Walter M V, editors. Manual of environmental microbiology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. pp. 324–333. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hines M E, Knollmeyer S L, Tugel J B. Sulfate reduction and other sedimentary biogeochemistry in a northern New England salt marsh. Limnol Oceanogr. 1989;34:578–590. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hines M E, Lyons W B. Biogeochemistry of nearshore Bermuda sediments. I. Sulfate reduction rates and nutrient generation. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1982;8:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Hines, M. E., et al. Unpublished data.

- 24.Howarth R W, Hobbie J E. The regulation of decomposition and heterotrophic microbial activity in salt marsh soils: a review. In: Kennedy V S, editor. Estuarine comparisons. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 103–127. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howarth R W, Teal J M. Sulfate reduction in a New England salt marsh. Limnol Oceanogr. 1979;24:999–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howes B L, Dacey J W H, King G M. Carbon flow through oxygen and sulfate reduction pathways in salt marsh sediments. Limnol Oceanogr. 1984;29:1037–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howes B L, Dacey J W H, Wakeham S G. Effects of sampling technique on measurements of porewater constituents in salt marsh sediments. Limnol Oceanogr. 1985;30:221–227. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howes B L, Teal J M. Oxygen loss from Spartina alterniflora and its relationship to salt marsh oxygen balance. Oecologia. 1994;97:431–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00325879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hull R J, Sullivan D M, Lytle J R W. Photosynthate distribution in natural stands of salt water cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora Loisel) Agron J. 1976;68:969–972. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang Y H, Morris J T. Fixation of inorganic carbon from different sources and its translocation in Spartina alterniflora Loisel. Aquat Bot. 1992;43:137–147. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jørgensen B B. A comparison of methods for the quantification of bacterial sulfate reduction in coastal marine sediments. I. Measurements with radiotracer techniques. Geomicrobiol J. 1978;1:11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jørgensen B B. A comparison of methods for the quantification of bacterial sulfate reduction in coastal marine sediments. III. Estimation from chemical and bacteriological field data. Geomicrobiol J. 1978;1:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jørgensen B B, Bak F. Pathways and microbiology of thiosulfate transformations and sulfate reduction in a marine sediment (Kattegat, Denmark) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:847–856. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.3.847-856.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laanbroek H J, Abee T, Voogd I L. Alcohol conversions by Desulfobulbus propionicus Lindhorst in the presence and absence of sulfate and hydrogen. Arch Microbiol. 1982;133:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laanbroek H J, Pfennig N. Oxidation of short-chain fatty acids by sulfate-reducing bacteria in freshwater and marine sediments. Arch Microbiol. 1981;128:330–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00422540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovley D R, Phillips E J P. Novel processes for anaerobic sulfate production from elemental sulfur by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2394–2399. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2394-2399.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luther G W, Ferdelman T G, Kostka J E, Tsamakis E J, Church T M. Temporal and spatial variability of reduced sulfur species (FeS2,S2O2/3-) and porewater parameters in salt marsh sediments. Biogeochemistry. 1991;14:57–88. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lytle R W, Jr, Hull R J. Annual carbohydrate variation in culms and rhizomes of the smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora Loisel) Agron J. 1980;72:942–946. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lytle R W, Jr, Hull R J. Photoassimilate distribution in Spartina alterniflora Loisel. I. Vegetative and floral development. Agron J. 1980;72:933–938. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malcom S J, Battersby N S, Stanley S O, Brown C M. Organic degradation, sulphate reduction and ammonia production in the sediments of Loch Eil, Scotland. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 1986;23:689–707. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendelssohn I A, McKee K L. Root metabolic response of Spartina alterniflora to hypoxia. In: Crawford R M M, editor. Plant life in aquatic and amphibious habitats. British Ecological Society special publication no. 5. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific; 1987. pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mendelssohn I A, McKee K L, Patrick J W H. Oxygen deficiency in Spartina alterniflora roots: metabolic adaptation to anoxia. Science. 1981;214:439–441. doi: 10.1126/science.214.4519.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moran M A, Torsvik V L, Torsvik T, Hodson R E. Direct extraction and purification of rRNA for ecological studies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:915–918. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.915-918.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrison M C, Hines M E. The variability of biogenic sulfur flux from a temperate salt marsh on short time and space scales. Atmos Environ. 1990;24:1771–1779. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Postgate J R. The sulphate-reducing bacteria. 2nd ed. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Purdy K J, Nedwell D B, Embley T M, Takii S. Use of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes to investigate the occurrence and selection of sulfate-reducing bacteria in response to nutrient addition to sediment slurry microcosms from a Japanese estuary. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;24:221–234. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rooney-Varga J N, Devereux R, Evans R S, Hines M E. Seasonal changes in the relative abundance of uncultivated sulfate-reducing bacteria in a salt marsh sediment and rhizosphere of Spartina alterniflora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3895–3901. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3895-3901.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rooney-Varga J N, Genthner B R S, Devereux R, Willis S G, Friedman S D, Hines M E. Phylogenetic and physiologic diversity of sulfate-reducing bacteria isolated from a salt marsh sediment. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:557–568. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(98)80068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sass H, Cypionka H, Babenzien H D. Vertical distribution of sulfate-reducing bacteria at the oxic-anoxic interface in sediments of the oligotrophic Lake Stechlin. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;22:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schubauer J P, Hopkinson C S. Above- and belowground emergent macrophyte production and turnover in a coastal marsh ecosystem, Georgia. Limnol Oceanogr. 1984;29:1052–1065. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharak Genthner B R, Mundfrom G, Devereux R. Characterization of Desulfomicrobium escambium sp. nov. and proposal to assign Desulfovibrio desulfuricans strain Norway 4 to the genus Desulfomicrobium. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharak Genthner B R, Price W A, Pritchard P H. Anaerobic degradation of chloroaromatic compounds in aquatic sediments under a variety of enrichment conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1466–1471. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.6.1466-1471.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skyring G W. Sulfate reduction in coastal ecosystems. Geomicrobiol J. 1987;5:295–374. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith D W. Ecological actions of sulfate-reducing bacteria. In: Odom J M, Singleton R Jr, editors. The sulfate-reducing bacteria: contemporary perspectives. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1993. pp. 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stahl D A, Amann R. Development and application of nucleic acid probes. In: Stackbrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. pp. 205–248. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stahl D A, Flesher B, Mansfield H R, Montgomery L. Use of phylogenetically based hybridization probes for studies of ruminal microbial ecology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1079–1084. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.5.1079-1084.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teske A, Ramsing N B, Habicht K, Fukui M, Küver J, Jørgensen B B, Cohen Y. Sulfate-reducing bacteria and their activities in cyanobacterial mats of Solar Lake (Sinai, Egypt) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2943–2951. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2943-2951.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trimmer M, Purdy K J, Nedwell D B. Process measurement and phylogenetic analysis of the sulfate reducing bacterial communities of two contrasting benthic sites in the upper estuary of the Great Ouse, Norfolk, UK. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;24:333–342. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vester F, Ingvorsen K. Improved most-probable-number method to detect sulfate-reducing bacteria with natural media and a radiotracer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1700–1707. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1700-1707.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Visscher P T, Prins R A, van Gemerden H. Rates of sulfate reduction and thiosulfate consumption in a marine microbial mat. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1992;86:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weber J C, Hines M E, Jones S H, Weber J H. Interactions of tin(IV) and monomethyltin cation in estuarine water-sediment slurries from Great Bay Estuary, New Hampshire, USA. Appl Organomet Chem. 1995;9:581–590. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weber J H, Evans R, Jones S H, Hines M E. Conversion of mercury(II) into mercury(O), monomethylmercury cation, and dimethylmercury in saltmarsh sediment slurries. Chemosphere. 1998;36:1669–1687. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Widdel F, Bak F. Gram-negative mesophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H, editors. The procaryotes. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 583–624. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Widdel F, Pfennig N. Studies on dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacteria that decompose fatty acids. I. Isolation of new sulfate-reducing bacteria enriched with acetate from saline environments. Description of Desulfobacter postgatei gen. nov., sp. nov. Arch Microbiol. 1981;129:395–400. doi: 10.1007/BF00406470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]