Abstract

Climate change is the greatest threat to global health in human history. It has been declared a public health emergency by the World Health Organization and leading researchers from academic institutions around the globe. Structural racism disproportionately exposes communities targeted for marginalization to the harmful consequences of climate change through greater risk of exposure and sensitivity to climate hazards and less adaptive capacity to the health threats of climate change. Given its interdisciplinary approach to integrating behavioral, psychosocial, and biomedical knowledge, the discipline of behavioral medicine is uniquely qualified to address the systemic causes of climate change-related health inequities and can offer a perspective that is currently missing from many climate and health equity efforts. In this article, we summarize relevant concepts, describe how climate change and structural racism intersect to exacerbate health inequities, and recommend six strategies with the greatest potential for addressing climate-related health inequities.

Keywords: Climate change, Health inequities, Structural racism, Environmental justice

This paper calls upon behavioral medicine to address factors that contribute to structural racism and other underlying causes of climate-related health inequities.

Implications.

Practice: Behavioral medicine practitioners have an important role to play in addressing climate-related health inequities in their clinical practice.

Policy: Policymakers who want to address health inequities exacerbated by climate change should support legislative action that prioritizes environmental justice and health equity.

Research: Future research should be aimed at dismantling structural racism, incorporating environmental justice efforts, and identifying effective communication strategies that promote action on climate change and health equity.

The health harms of climate change are accelerating at an alarming rate and having a significant impact on the well-being of the general population [1]. In 2020, the intersection of climate change and structural racism on the health of individuals from racialized groups targeted for marginalization in the United States entered the national conversation in new ways and included a reckoning among health professionals about the importance of addressing the root causes of health inequities [2, 3]. It was against this backdrop that the Society of Behavioral Medicine’s Health Inequities and Climate Change Presidential Working Group convened to develop strategies for addressing climate-related health inequities.

Structural racism exacerbates climate-related health inequities through increased exposure to climate hazards, increased sensitivity to the health harms of climate change, and decreased adaptive capacity in communities targeted for marginalization. Through policy decisions such as redlining and the creation of “sacrifice zones” (i.e., geographic areas that have been permanently impaired by environmental damage or economic disinvestment), structural racism plays a central role in perpetuating the adverse health effects of climate change on populations targeted for marginalization.

In this call to action for the behavioral medicine community, we summarize relevant concepts, describe how climate change and structural racism intersect to exacerbate health inequities, and recommend strategies that have the greatest potential for addressing systemic causes. Throughout the article, we take a deliberate antiracist approach and attempt to embody the principles we recommend with the content and terminology we use. We center the voices of members from communities targeted for marginalization in determining solutions for dismantling structural racism, including recommendations to use intentional language. Therefore, we use the term “communities targeted for marginalization” throughout instead of terms such as “minorities,” “marginalized communities,” and “oppressed communities,” as a means of centering the conditions imposed on these communities as the root cause of health inequities while avoiding terminology that further oppresses these communities through the implication that they are holistically defined by their oppression [4, 5].

Definitions

Health Inequities

A health inequity is a particular type of health difference that adversely affects groups of people who have systematically experienced significant obstacles to health based on characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion [6].

Individuals from racialized groups targeted for marginalization have worse health outcomes than their white counterparts [7], including worse infant and maternal mortality [8], cardiovascular disease [9], cancer [10], Type 2 diabetes [11], hypertension [12], and pulmonary disease [13]. Lighter skin tone maps on to lower mortality rates, highlighting the influence of “colorism” and anti-Black racism [14, 15]. There is a growing recognition of the importance of addressing the root causes of health inequities, including structural racism [16] as well as climate change, which exacerbates health inequities and is predicted to amplify them further in the coming decades [17].

Racism

Racism has a structural basis and is embedded in long-standing social policy. It includes private prejudices held by individuals and is also produced and reproduced by laws, rules, and practices, sanctioned and implemented by various levels of government, and embedded in the economic system as well as in cultural and societal norms [18].

Racism can take place across different levels. Internalized racism comprises beliefs about race which are influenced by culture. Internalized racism can work as a psychosocial stressor and is associated with depression, anxiety, and stress [19–21]. Interpersonal racism refers to discriminatory interactions between individuals that reinforce hierarchical ordering of racialized groups. Although the most readily recognized forms of interpersonal racism include racially motivated attacks and microaggressions, unconscious bias, and other discriminatory behaviors in healthcare settings can lead to substandard care and worse health outcomes among individuals from racialized groups [7, 22–24]. Institutional racism refers to unfair policies and discriminatory practices of institutions that restrict access to the goods, services, and opportunities of societies. For example, financial institutions’ failure to provide adequate home financing to qualified applicants from racialized groups (i.e., mortgage discrimination) contributes to inequities in socioeconomic status and the decline of neighborhoods targeted for marginalization [25]. Systemic racism is the system in which policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other factors operate in various overlapping and reinforcing ways to systematically disempower and endanger racialized groups. For example, the Social Security Act of 1935 created a system of employment-based health insurance coverage that interacts with discriminatory hiring practices [26] to restrict access to health care for racialized groups leading to health inequities. Structural racism refers to the totality of ways in which societies reinforce racial discrimination through inequitable systems that are historically rooted and culturally reinforced.

There are many ways in which structural racism manifests. For example, government-sponsored racial residential segregation created a platform for broad social disinvestment in neighborhood infrastructure and services (e.g., transportation, schools), and is a primary cause of racial differences in socioeconomic status (SES) by restricting access to home ownership (a major determinant of inter-generational wealth), education, and employment opportunities [27]. Current policies that tie wealth to local political power—and therefore resource allocation—help perpetuate these structural disadvantages and promote racial stereotypes that undercut support for policies with the potential to improve economic well-being and environmental conditions for low SES individuals from all racial and ethnic identities.

Climate Change Exacerbates Health Inequities

Structural racism has concentrated the conditions that determine vulnerability to climate change in communities targeted for marginalization. These conditions include increased exposure, increased sensitivity, and decreased adaptive capacity [28–30]. Exposure refers to human contact with various environmental hazards (e.g., extreme weather events, exposure to toxic waste, infectious disease vectors), which will continue to increase with climate change, especially in communities targeted for marginalization. Sensitivity is the degree to which climate hazards impact humans, and is determined by underlying individual and community characteristics, such as SES and chronic disease burden. Adaptive capacity is the ability to cope with the consequences of climate change, which is impaired for individuals and communities with insufficient access to resources and political power.

Exposure

As a consequence of government-sponsored racially discriminatory policies, such as racial residential segregation, individuals from communities targeted for marginalization are at increased risk of exposure to climate hazards given their higher likelihood of living in risk-prone areas. For example, historically redlined neighborhoods [27] are disproportionately exposed to extreme intra-urban heat [31]. These communities are also more likely to be located in flood-prone areas [32, 33], near sites that release toxic waste when flooded [34], in areas with aging or decaying infrastructure, and in areas with a high burden of air pollution [35–37]. Discriminatory practices also often designate these same communities as “sacrifice zones” or “fenceline communities,” in which toxic pollutants and chemical exposures are concentrated, decreasing property value and opportunities for upward mobility while exacerbating health risks for individuals living in these communities [34, 38–41].

Sensitivity

Discriminatory policies, attitudes, and resource distribution also create barriers to health and contribute to inequities in the prevalence of chronic conditions associated with increased sensitivity to climate hazards [29]. Some of these barriers include limited access to full-service grocery stores with healthy and affordable dietary choices [42], limited access to green spaces [43], clustering of alcohol outlets [44], and targeted tobacco marketing [45]. These barriers increase risk of developing chronic illnesses such as cardiometabolic disease [46], cancer [47], and pulmonary disease [47, 48], all of which are illnesses that confer increased risk of climate-related morbidity and mortality [17, 49–51]. The systematic disinvestment in neighborhoods targeted for marginalization has also resulted in under-resourced health facilities, making it more difficult to recruit experienced and well-credentialed primary care providers and specialists [18], creating challenges in appropriately managing chronic conditions [52], and in providing continuity of care for patients with chronic diseases during and in the aftermath of extreme weather events [53].

Adaptive Capacity

Material and psychosocial circumstances can collectively impede the ability of individuals from communities targeted for marginalization to prepare for, respond to, and cope with climate-related hazards. Restricted access to the resources needed to follow emergency preparedness instructions, including being unable to stockpile food or evacuate in response to a warning, create barriers for residents of communities targeted for marginalization to prepare for extreme weather events [54]. Similarly, lack of adequately insulated housing, inability to afford or use air conditioning, and inadequate access to public shelters such as cooling centers limit the ability of individuals from these communities to respond to heat waves. Furthermore, the pervasive racial wealth gap leads to inequitable access to climate change mitigation resources. For example, solar panel adoption could help communities manage increasing climate change-related electricity costs and disruptions, as well as aid climate change mitigation [55], but there are barriers to adoption within communities targeted for marginalization [56].

Institutional racism also contributes to diminished adaptive capacity by limiting the ability of individuals from communities targeted for marginalization to cope with climate hazards. For example, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has a program for voluntary buy-out of flood-prone properties. However, this managed retreat program is available only to privileged communities [57]. Furthermore, Black disaster survivors have a lower probability of receiving FEMA assistance, and FEMA provides greater postdisaster financial assistance to white disaster survivors, even when the amount of damage is the same [58, 59].

A Call to Action for Behavioral Medicine

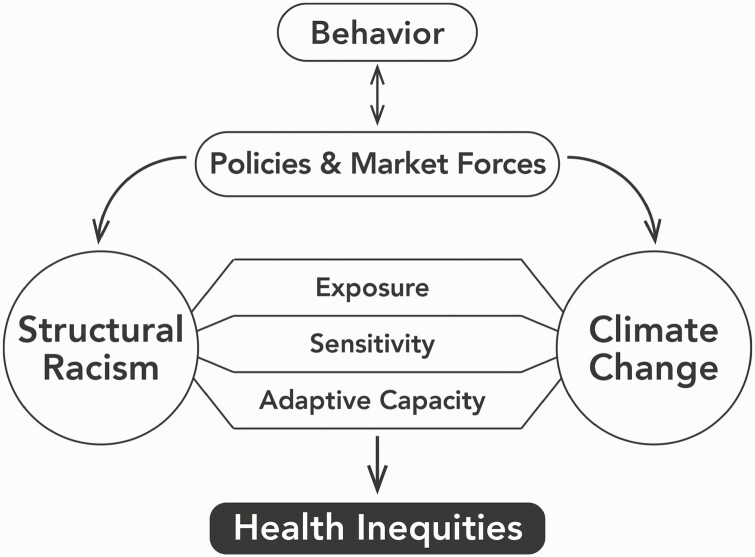

Climate change is already exacerbating health inequities rooted in structural racism. As public awareness of the shared structural causes of climate change and racism increases, the specific behavior changes necessary to address climate-related health inequities become clearer. These include consumer [60], professional [61], and social behaviors [62, 63] that influence market forces and policy changes impacting both structural racism [64] and climate change [55, 65], thus diminishing health inequities (Figure 1) [66].

Fig. 1.

Behavior changes that influence policies and market forces (such as supporting bans on development of new fossil fuel infrastructure near communities targeted for marginalization, urging professional institutions to divest from fossil fuels, and advocating for fair distribution of health resources and environmental burdens) are more likely to address both structural racism and climate change than behavioral changes aimed at reducing individual carbon footprint. Structural racism leads to increased exposure and sensitivity, and decreased adaptive capacity to the health consequences of climate change, amplifying health inequities.

The field of behavioral medicine is uniquely qualified to address climate change-related health inequities. It could offer a perspective currently missing from many climate and health equity efforts by leveraging its scholarly, educational, advocacy, and clinical practices to ensure that proposed solutions deliver better, more equitable health outcomes. We offer the following recommendations for how behavioral medicine professionals can center antiracism in professional activities aimed at addressing structural determinants of climate-related health inequities (Table 1). We further encourage behavioral medicine professionals to reflect on ways that addressing climate-related health inequities can be integrated into research, education, advocacy, and clinical practice.

Table 1.

Summary of recommendations for behavioral medicine in addressing climate-related health inequities

| 1. Adopt standards for the measurement and reporting of race as a sociopolitical construct in all behavioral medicine research and practices, including those directed at addressing climate change. |

| 2. Operationalize the concept of structural racism in all behavioral medicine research and practices, including those directed at addressing climate change. |

| 3. Incorporate environmental justice efforts into behavioral medicine research and practices. |

| 4. Center the voices of communities targeted for marginalization in all behavioral medicine research and practices, including those that address climate and environmental justice. |

| 5. Prioritize policy action on climate change and health equity. |

| 6. Identify effective communication strategies to foster action on climate change and health equity issues. |

Recommendation 1: Adopt Standards for the Measurement and Reporting of Race as a Sociopolitical Construct in All Behavioral Medicine Research and Practices, Including Those Directed at Addressing Climate Change

Modern American medicine has historical roots in scientific racism, which reified the concept of race as an innate biologic attribute [67]. However, race is socially constructed, and should only be used in behavioral medicine research and practice as a proxy for exposures to racism [68]. A wide adoption of guidelines and policies on conceptualizing race and ethnicity [69–71] is important because requiring behavioral medicine professionals to recognize the social and environmental conditions imposed on racialized groups as the fundamental causes of health outcomes can help identify modifiable systemic factors contributing to health inequities exacerbated by climate change [72]. Therefore, we recommend that behavioral medicine professionals adopt the practice of conceptualizing race as a sociopolitical construct in all research, publications, grant announcements and proposals, and other professional activities.

Recommendation 2: Operationalize the Concept of Structural Racism in All Behavioral Medicine Research and Practices, Including Those Directed at Addressing Climate Change

Structural racism is at the crux of racial health inequities exacerbated by climate change. Naming racism and identifying the type (internalized, interpersonal, institutional, systemic) of racism impacting health outcomes helps center the relevant social, environmental, and structural conditions imposed on communities targeted for marginalization as modifiable factors contributing to climate change-related health inequities.

Structural factors, such as education, housing, social security, and healthcare policies interact with broader cultural and institutional contexts to shape health trajectories [73, 74]. Thus, implementing theoretical frameworks, methodologies, and language that contribute to a paradigm shift from focusing on “individual behaviors” to examining the cumulative and interactive effects of systemic structures on health [5, 75–78], including measures of structural racism [79–81], are crucial for addressing climate-related health inequities. Therefore, we recommend that behavioral medicine professionals name racism, identify the type of racism contributing to climate-related health inequities, and adopt antiracism strategies in all professional activities.

Recommendation 3: Incorporate Environmental Justice Efforts Into Behavioral Medicine Research and Practices

Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in the development, implementation, and enforcement of policies and practices determining the distribution of environmental resources and burdens. The environmental justice movement, primarily led by communities targeted for marginalization, has battled discriminatory policies and practices that amplify climate change-related health disparities [82–85] and increase risk of exposure to other hazards. As behavioral medicine professionals, we must partner across communities and disciplines to generate evidence needed for legislative action and advocate for meaningful policy changes nationally and locally (including at our own institutions). For example, the construction of oil pipelines is concentrated near Indigenous communities, increasing health risks via environmental destruction, exposure to toxic chemicals, and increased risk of sexual violence [86–89]. Research on the short and long-term health, behavior, and quality of life consequences of proximity to fossil fuel infrastructure supports legislation banning new fossil fuel infrastructure development in communities targeted for marginalization [39, 55, 90]. Additionally, many interventions that target the disproportionate exposure to hazards due to structural racism [18, 91], as well as the integration of various antiracism approaches [92], have been tested. However, additional research is needed on the feasibility of scaling up targeted interventions [93] and whether the combination of interventions at different levels (individual, institution, policy) confer multiplicative effects for health [94]. Behavioral medicine’s efforts to address the unequal health consequences of climate change must operate from an environmental justice perspective to be truly impactful. Therefore, we recommend that behavioral medicine professionals apply environmental justice principles in all professional activities.

Recommendation 4: Center the Voices of Communities Targeted for Marginalization in All Behavioral Medicine Research and Practices, Including Those That Address Climate and Environmental Justice

Social and economic interventions at the community and population levels are crucial for addressing the structural determinants of health inequities. However, funding agencies are more likely to fund studies focusing on biologic and mechanistic investigations [95]. This pattern perpetuates the racial gap in grant funding because individuals from communities targeted for marginalization are more likely to propose research focused on social determinants of health and economic interventions [96]. Additionally, funding agencies and research institutions rely heavily on metrics that reflect exclusionary professional networks [97], which perpetuate the lack of diversity in the academic and scientific workforce [98].

The lack of diversity in the academic and scientific workforce contributes to the implementation of interventions developed from a limited, white-centered perspective, and can therefore exacerbate the very inequities that were the target of the intervention. For example, “urban greening” interventions developed without community partnership can lead to “climate/environmental gentrification,” or can be experienced as disruptive, thereby displacing and siphoning resources away from individuals in the communities meant to benefit from the interventions [99, 100].

Community-based participatory research is one approach that promotes the development of interventions to address community concerns and health inequities through a collaborative effort between researchers and community members involved as equal partners in all stages of research, and incorporates community practices, capacity building, and co-learning [101]. Other approaches that prioritize decision support, citizen science, community engagement, grassroots movements, and a research culture that is more inclusive [102–104] can also be implemented. Additionally, centering the lived experiences of individuals from communities targeted for marginalization leads to the development of more appropriate interventions, enhances the relevance and generalizability of findings, provides disciplines with valuable perspectives, and embodies antiracism principles as a part of the process. For example, “Indigenizing” food sovereignty is a broad, restorative, and sustainable approach to addressing food systems in a way that centers the voices and expertise of communities targeted for marginalization and most directly impacted by environmental injustices [105].

At the institutional level, behavioral medicine professionals can ask how diversity metrics (including diversity in leadership positions and salary inequality) and biases in hiring and promotion processes are evaluated and addressed, what type of diversity training is offered [18], and what procedures are in place to handle allegations of racial discrimination. Behavioral medicine professionals also can help center the voices of individuals from communities targeted for marginalization by incentivizing collaborative, community-oriented approaches to scholarship, advocating for systems-level supports that are invested in retention of professionals from communities targeted for marginalization, and amplifying the work and expertise of colleagues from these communities through recommendations for awards, positions on study sections, and leadership roles with decision-making power. Therefore, we recommend that behavioral medicine professionals support this essential culture shift to ensure that approaches used to address climate-related health inequities will have a healthy impact on all communities while also improving health equity.

Recommendation 5: Prioritize Policy Action on Climate Change and Health Equity

An outsized emphasis in behavioral literature has focused on behavioral changes for reducing individuals’ greenhouse gas emissions (i.e., “sustainable behaviors”) [106–108]. However, these are not sufficient to reduce climate change threats and behavioral changes aimed at addressing the systemic determinants of climate change and health inequities are required. In 2019, two federal bills, the Green New Deal [109] and the Environmental Justice Act of 2019 [110], were introduced to the House of Representatives and the Senate, both of which have the potential to address the structural causes of health inequities exacerbated by climate change. In addition to state and federal environmental laws, local land use planning, zoning code changes, ordinances, public health codes, and administrative policies at the city, county, and municipality levels have tremendous environmental justice potential [111].

Research can contribute to the evidence base needed to implement national, state, and local policies that address climate change and health equity [112, 113], including information used in environmental reviews and impact analysis conducted for local zoning and siting decisions [111]. Research can also evaluate the combined environmental and health impact of policies that subsidize fossil fuels [114], encourage the consumption of unhealthy foods [115] with high environmental impact [116, 117], or tobacco taxation policies, which both reduce smoking rates [118] and the environmental impact of tobacco [119].

Climate change and health equity policies can also be advanced through direct advocacy efforts [120]. There are multiple examples of advocacy leading to institutional policy change including student-led advocacy to divest from fossil fuels at Historically Black Colleges and Universities [121], Harvard [122], and the University of Minnesota [123], medical students advocating for the inclusion of climate change in their educational curriculum [124], and nurses advocating to reduce the environmental footprint within their healthcare systems [125]. These institutional efforts can influence market forces, which is especially important for system-level changes in fossil fuel consumption, where market prices fail to reflect the true cost of use [126]. As behavioral medicine professionals often working within large academic or healthcare institutions, we can also participate in broader advocacy efforts, which have the potential to influence higher-level structural factors as demonstrated by the Black Lives Matter movement leading to policy reforms in policing [127].

Climate-related health inequities are the result of tremendous power imbalances resulting from structural racism. Advocacy efforts lead by members from communities targeted for marginalization are strengthened when individuals from different backgrounds and in positions of power support them [128].Behavioral medicine professionals can amplify the impact of their research and advocacy efforts by recognizing and applying their own privileges and positions of power to advance antiracism efforts. Therefore, we recommend that behavioral medicine professionals conduct research on behavior changes that can impact structural determinants of climate change and health inequities, recognize individual privileges and positions of power, and engage in advocacy efforts related to climate change and health equity.

Recommendation 6: Identify Effective Communication Strategies to Foster Action on Climate Change and Health Equity Issues

Although the science is settled on the anthropogenic causes of climate change [129], and evidence continues to mount on the adverse and inequitable health impacts of climate change [28], climate change denial messages and efforts to delay or minimize climate action—including claims that it is too late to act on climate change (i.e. “doomism”) and shifting focus to “sustainable behaviors”—have been widely successful in stymying restorative action [107, 130, 131]. Climate change denial efforts are well-funded [132], and the same funders are the top monetary contributors to lawmakers sponsoring discriminatory bills and opposing policies necessary for reducing health inequities [66]. Therefore, communication strategies that go beyond disseminating scientific evidence on climate change and move toward increasing public recognition of the shared systems that contribute to both climate change and health inequities are needed. Communication that informs consumers of corporate practices that help uphold the structural determinants of climate change and health inequities are especially important. Consumer behavior changes can influence market forces and pressure companies to stop funding groups and organizations that are the worst contributors to climate change and perpetrators of climate change denial [133–135], thus addressing multiple structural-level factors.

Research has demonstrated that there are underlying factors that increase the likelihood of public engagement and motivate climate-related behaviors including changing norms, making messages personally relevant, appealing to values, emphasizing immediacy of benefits, and engaging emotional connection with the content [108, 136, 137]. Thus, communication strategies that prioritize action on climate change and environmental justice would likely benefit from framing in ways that are consistent with these underlying motivational factors. Therefore, we recommend that behavioral medicine professionals focus on developing communication strategies that expand public knowledge and foster action on the shared determinants of climate change and health inequities.

Conclusion

We have described how systemic factors drive structural racism and climate change and how these work synergistically to exacerbate health inequities (Figure 1). Our recommendations focus on how behavior changes that actively challenge these systemic factors can help dismantle the structural determinants of climate change and health inequities (Table 1). Additional forms of advocacy are described in the paper on climate advocacy and policy (this issue).

The behavioral medicine community can help bolster climate change and health equity efforts by expanding the scientific evidence needed for legislative action, using positions of influence to address power imbalances and advocate for system-level changes, and identifying effective strategies for advancing climate and health equity efforts. As an interdisciplinary field that is focused on health promotion, disease prevention, health equity, and addressing the biomedical, behavioral, and psychosocial aspects of health and well-being, behavioral medicine has an opportunity and the responsibility to heed the call to action for addressing climate change-related health inequities. How we respond to that call will impact the health of individuals from communities targeted for marginalization, future generations, and the health of the entire population.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a compilation of work from the Health Inequities and Climate Change subgroup of the Society of Behavioral Medicine’s Presidential Working Group on Climate. We would like to thank Dr. Elissa Epel, PhD, for her leadership as Chair of the subgroup.

Funding

BMB is supported by NIH grant 5T32CA250803-02.

Compliance With Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Human Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This article does not involve human participants and informed consent was therefore not required.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Transparency Statements

Five transparency statements related to (1) study registration, (2) analytic plan registration, (3) availability of data, (4) availability of analytic code, and (5) availability of materials.

Study registration: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Formal registration is not applicable for this manuscript.

Analytic plan preregistration: This article does not contain any analyses performed by any of the authors. Formal preregistration for an analysis plan is not applicable for this manuscript.

Data availability: Data availability is not applicable for this article.

Analytic code availability: There is not analytic code associated with this article.

Materials availability: There are no materials associated with this study.

References

- 1. Masson-Delmotte, V, Zhai, P, Pirani, A,, et al. IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, in Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland: Cambridge University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works—Racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krieger N. Enough: COVID-19, structural racism, police brutality, plutocracy, climate change-and time for health justice, democratic governance, and an equitable, sustainable future. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(11):1620–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cooper J. A Call for a Language Shift: From Covert Oppression to Overt Empowerment. 2016. http://education.uconn.edu/2016/12/07/a-call-for-a-language-shift-from-covert-oppression-to-overt-empowerment/. Accessibility verified July 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buchanan, NT, Perez, M, Prinstein, MJ, Thurston, IB. Upending racism in psychological science: Strategies to change how science is conducted, reported, reviewed, and disseminated. Am Psychol. 2021;76(7):1097–1112. doi:10.1037/amp0000905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beadle, MR, Graham GN, . U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Office of Minority Health (2011) National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity. Manual. UNSPECIFIED. 2011. doi:10.13016/4zxc-obmr [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. MacDorman MFThoma M, Declcerq E, Howell EA. . Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal mortality in the united states using enhanced vital records, 2016‒2017. Am J Public Health. 2002;111(9):1673–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Graham G. Disparities in cardiovascular disease risk in the United States. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11(3):238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aizer AA, Wilhite TJ, Chen MH, et al. Lack of reduction in racial disparities in cancer-specific mortality over a 20-year period. Cancer. 2014;120(10):1532–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020: 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fiscella K, Holt K. Racial disparity in hypertension control: tallying the death toll. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(6):497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Assari S, Chalian H, Bazargan M. Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and chronic lung disease in the U.S. Res Health Sci. 2020;5(1):48–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cobb RJ, Thomas CS, Laster Pirtle WN, Darity WA Jr. Self-identified race, socially assigned skin tone, and adult physiological dysregulation: assessing multiple dimensions of “race” in health disparities research. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stewart QT, Cobb RJ, Keith VM. The color of death: race, observed skin tone, and all-cause mortality in the United States. Ethn Health. 2020;25(7):1018–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, et al. The 2020 report of the lancet countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. Lancet. 2021;397(10269):129–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gale MM, et al. A meta-analysis of the relationship between internalized racial oppression and health-related outcomes. Counseling Psychol. 2020;48(4):498–525. [Google Scholar]

- 21. James D. Health and health-related correlates of internalized racism among racial/ethnic minorities: A review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(4):785–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(16):4296–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gangopadhyaya A, . Black Patients Are More Likely Than White Patients to Be in Hospitals with Worse Patient Safety Conditions. Washington, DC: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shavers VL, Shavers BS. Racism and health inequity among Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(3):386–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pager D, Shepherd H. The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:181–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rothstein R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rudolph L, et al. Climate Change, Health, and Equity: A Guide for Local Health Departments. Oakland, CA: Public Health Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Balbus JM, Malina C. Identifying vulnerable subpopulations for climate change health effects in the United States. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(1):33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. English PB, Richardson MJ. Components of population vulnerability and their relationship with climate-sensitive health threats. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2016;3(1):91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoffman JS, Shandas V, Pendleton NJC. The effects of historical housing policies on resident exposure to intra-urban heat: A study of 108 US urban areas. 2020;8(1):12. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Frank, T. Flooding disproportionately harms black neighborhoods. Scientific American. 2020. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/flooding-disproportionately-harms-black-neighborhoods/# [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Framing the Challenge of Urban Flooding in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taylor DE. Toxic Communities Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility. New York, NY: NYU Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tessum CW, Apte JS, Goodkind AL, et al. Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial-ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(13):6001–6006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tessum CW, et al. PM(2.5) polluters disproportionately and systemically affect people of color in the United States. Sci Adv. 2021;7(18). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Woo B, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Sass V, Crowder K, Teixeira S, Takeuchi DT. Residential segregation and racial/ethnic disparities in ambient air pollution. Race Soc Probl. 2019;11(1):60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bullard RD, et al. Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty 1987–2007: Grassroots Struggles to Dismantle Environmental Racism in the United States, in United Church of Christ Justice and Witness Ministries. Cleveland, OH :Justice and Witness Ministries United Church of Christ 700 Prospect Ave; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnston J, Cushing L. Chemical exposures, health, and environmental justice in communities living on the fenceline of industry. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2020;7(1):48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mohai, P, Saha R. Which came first, people or pollution? Assessing the disparate siting and post-siting demographic change hypotheses of environmental injustice. Environ Res Lett. 2015;10(11):115008. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stretesky PB, McKie R. A perspective on the historical analysis of race and treatment storage and disposal facilities in the United States. Environ Res Lett. 2016;11(3). [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hilmers A, Hilmers DC, Dave J. Neighborhood disparities in access to healthy foods and their effects on environmental justice. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1644–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rowland-Shea J, et al. The Nature Gap Confronting Racial and Economic Disparities in the Destruction and Protection of Nature in America. In Center for American Progress. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Trangenstein PJ, Gray C, Rossheim ME, Sadler R, Jernigan DH. Alcohol outlet clusters and population disparities. J Urban Health. 2020;97(1):123–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee JG, Henriksen L, Rose SW, Moreland-Russell S, Ribisl KM. A systematic review of neighborhood disparities in point-of-sale tobacco marketing. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lukachko A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morello-Frosch R, Jesdale BM. Separate and unequal: residential segregation and estimated cancer risks associated with ambient air toxics in U.S. metropolitan areas. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(3):386–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nardone A, Casey JA, Morello-Frosch R, Mujahid M, Balmes JR, Thakur N. Associations between historical residential redlining and current age-adjusted rates of emergency department visits due to asthma across eight cities in California: an ecological study. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(1):e24–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hiatt RA, Beyeler N. Cancer and climate change. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(11):e519–e527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kenny GP, Yardley J, Brown C, Sigal RJ, Jay O. Heat stress in older individuals and patients with common chronic diseases. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):1053–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xu R, Zhao Q, Coelho MSZS, et al. Association between heat exposure and hospitalization for diabetes in Brazil during 2000-2015: a nationwide case-crossover study. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127(11):117005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Qato DM, Daviglus ML, Wilder J, Lee T, Qato D, Lambert B. ‘Pharmacy deserts’ are prevalent in Chicago’s predominantly minority communities, raising medication access concerns. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(11):1958–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Arrieta MI, Foreman RD, Crook ED, Icenogle ML. Providing continuity of care for chronic diseases in the aftermath of Katrina: from field experience to policy recommendations. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3(3):174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fothergill A, Peek LA. Poverty and disasters in the United States: a review of recent sociological findings. Nat Hazards. 2004;32(1):89–110. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Olhoff A, Christensen JM.. Emissions Gap Report 2020. Nairobi: United Nations; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sunter DA, Castellanos S, Kammen DM. Disparities in rooftop photovoltaics deployment in the United States by race and ethnicity. Nat Sustain. 2019;2(1):71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mach KJ, Kraan CM, Hino M, Siders AR, Johnston EM, Field CB. Managed retreat through voluntary buyouts of flood-prone properties. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):eaax8995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Billings SB, Gallagher E, Ricketts L.. Let the rich be flooded: the distribution of financial aid and distress after hurricane harvey. J financ econ. 2019. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3396611 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Domingue SJ, Emrich CT, Social vulnerability and procedural equity: exploring the distribution of disaster aid across counties in the United States. Am Rev Publ Admin. 2019;49(8):897–913. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Creutzig F, et al. Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nat Clim Change. 2018;8(4):260–263. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nogueira LM, Yabroff KR, Bernstein A. Climate change and cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Otto IM, Donges JF, Cremades R, et al. Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(5):2354–2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Marquardt J. Fridays for future’s disruptive potential: An inconvenient youth between moderate and radical ideas. Front Commun. 2020;5(48). [Google Scholar]

- 64. Breland JY, Stanton MV. Anti-Black racism and behavioral medicine: confronting the past to envision the future. Transl Behav Med. 2022;12(1):ibab090. doi:10.1093/tbm/ibab090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet. 2015;386(10006):1861–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Krieger N. Climate crisis, health equity, and democratic governance: the need to act together. J Public Health Policy. 2020;41(1):4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jackson JP, Jr., Weidman NM, Rubin G. The origins of scientific racism. J Blacks Higher Educ. 2005;( 50):66–79. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 (Suppl 1):S30–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Andrews AL, Unaka N, Shah SS. New author guidelines for addressing race and racism in the journal of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(4):197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Breathett K, Spatz ES, Kramer DB, et al. The groundwater of racial and ethnic disparities research: a statement from circulation: cardiovascular quality and outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(2):e007868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Flanagin A, Frey T, Christiansen SL; AMA Manual of Style Committee . Updated guidance on the reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals. JAMA. 2021;326(7):621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Krieger N. Structural racism, health inequities, and the two-edged sword of data: structural problems require structural solutions. Front Public Health. 2021;9:655447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q. 2019;97(2):407–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Krieger N. Epidemiology—Why epidemiologists must reckon with racism. In: Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional. Washington, DC:American Public Health Association; 2019:249–266. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Smedley B. Toward a comprehensive understanding of racism and health inequities: a multilevel approach. In: Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional. Washington, DC:American Public Health Association; 2019:469–477. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dennis AC, Chung EO, Lodge EK, Martinez RA, Wilbur RE. Looking back to leap forward: a framework for operationalizing the structural racism construct in minority health research. Ethn Dis. 2021;31(Suppl 1):301–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice to implement strategic public health science. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(8):1389–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Groos M, et al. Measuring inequity: a systematic review of methods used to quantify structural racism. J Health Disparities Res Pract. 2018;11(2):13. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hunter D, et al. Health and Democracy Index. 2021. https://democracyindex.hdhp.us/about/. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the index of concentration at the extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bullard RD, Johnson GS. Environmental justice: grassroots activism and its impact on public policy decision making. J Social Issues. 2000;56(3):555–578. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mohai P, Pellow D, Roberts JT. Environmental justice. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2009;34(1):405–430. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sicotte DM, Brulle RJ. Social movements for environmental justice through the lens of social movement theory. In: Holifield R, Jayajit Chakraborty J, Gordon Walker G, eds. The Routledge. Handbook of Environmental Justice. Abingdon:Routledge; 2017:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Timmons Roberts J, Pellow D, Mohai P. Environmental justice. In: Boström M., Davidson, D.J., eds. Environment and Society: Concepts and Challenges. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018: 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Emanuel RE, Caretta MA, Rivers L 3rd, Vasudevan P. Natural gas gathering and transmission pipelines and social vulnerability in the United States. Geohealth. 2021;5(6):e2021GH000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Finn K, et al. Responsible resource development and prevention of sex trafficking: Safeguarding native women and children on the Fort Berthold Reservation. Harv Women’s LJ. 2017;40:1. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Jonasson ME, Spiegel SJ, Thomas S, et al. Oil pipelines and food sovereignty: threat to health equity for Indigenous communities. J Public Health Policy. 2019;40(4):504–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Martin K, et al. Violent Victimization Known to Law Enforcement in the Bakken Oil-Producing Region of Montana and North Dakota, 2006–2012. Washington, DC: National Crime Statistics Exchange; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Jacobs-Shaw R. What Standing Rock teaches us about environmental racism and justice. Health Affairs. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E, Petticrew M. The health impacts of housing improvement: a systematic review of intervention studies from 1887 to 2007. Am J Public Health. 2009;99 (Suppl 3):S681–S692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ben J, Kelly D, Paradies Y. Contemporary anti-racism: A review of effective practice. In: Solomos J, ed. Routledge International Handbook of Contemporary Racisms. New York, NY: Routledge; 2020:205–215. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Artiga S, Hinton E. Beyond health care: The role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. In: Issue brief. San Francisco, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pedersen A, Walker I, Wise M. “Talk does not cook rice”: Beyond anti-racism rhetoric to strategies for social action. Austral Psychol. 2005;40(1):20–31. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA, et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):eaaw7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, et al. Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science. 2011;333(6045):1015–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bennett CL, Salinas RY, Locascio JJ, Boyer EW. Two decades of little change: An analysis of U.S. medical school basic science faculty by sex, race/ethnicity, and academic rank. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Davies SW, Putnam HM, Ainsworth T, et al. Promoting inclusive metrics of success and impact to dismantle a discriminatory reward system in science. PLoS Biol. 2021;19(6):e3001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Keenan JM, Hill T, Gumber A, Climate gentrification: from theory to empiricism in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Environ Res Lett. 2018;13(5):054001. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Triguero-Mas M, Anguelovski I, García-Lamarca M, et al. Natural outdoor environments’ health effects in gentrifying neighborhoods: disruptive green landscapes for underprivileged neighborhood residents. Soc Sci Med. 2021;279:113964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, et al. Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Geller A. Environmental Justice Research Roadmap. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development (8101R); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 103. White-Newsome JL, Meadows P, Kabel C. Bridging climate, health, and equity: a growing imperative. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(Suppl 2):S72–S73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Coté C. “Indigenizing” food sovereignty. Revitalizing indigenous food practices and ecological knowledges in Canada and the United States. Humanities. 2016;5(3):57. [Google Scholar]

- 106. Ivanova D, et al. Quantifying the potential for climate change mitigation of consumption options. Environ Res Lett. 2020;15(9):093001. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Mann ME. The New Climate War: The 3 Fight to Take Back Our Planet. New York, NY: PublicAffairs; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 108. van den Berg NJ, et al. , Improved modelling of lifestyle changes in Integrated Assessment Models: Cross-disciplinary insights from methodologies and theories. Energy Strat Rev. 2019;26:100420. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Text - H.Res.109 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal. 2019. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/109/text

- 110. Text - S.2236 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): A bill to require Federal agencies to address environmental justice, to require consideration of cumulative impacts in certain permitting decisions, and for other purposes. 2019. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/2236/text

- 111. Park H, County F, County W.. Local Policies for Environmental Justice: A National Scan. New York, NY: Tishman Environment and Design Center; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 112. Duffy PB, et al. Strengthened scientific support for the Endangerment Finding for atmospheric greenhouse gases. Science 2019;363(6427). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Chan M. Achieving a cleaner, more sustainable, and healthier future. Lancet. 2015;386(10006):e27–e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Coady D, et al. How large are global fossil fuel subsidies? World Dev. 2017;91:11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 115. Do WL, Bullard KM, Stein AD, Ali MK, Narayan KMV, Siegel KR. Consumption of foods derived from subsidized crops remains associated with cardiometabolic risk: an update on the evidence using the national health and nutrition examination survey 2009–2014. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3244. doi:10.3390/nu12113244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Clune S, Crossin E, Verghese KJJOCP. Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories. J Clean Prod. 2017;140:766–783. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Vermeulen SJ., Campbell BM, Ingram JS. Climate change and food systems. Ann Rev Environ Res. 2012;37:195–222. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sharbaugh MS, Althouse AD, Thoma FW, Lee JS, Figueredo VM, Mulukutla SR. Impact of cigarette taxes on smoking prevalence from 2001–2015: A report using the Behavioral and Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS). PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. World Health Organization. Tobacco and Its Environmental Impact: An Overview. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 120. Stephens JC, Frumhoff PC, Yona L. The role of college and university faculty in the fossil fuel divestment movement. Elem Sci Anth. 2018;6. [Google Scholar]

- 121. White A. HBCUs Opt for Sustainability Over Fossil Fuel Divestment. 2016. https://hbsciu.com/2016/08/15/hbcus-opt-for-sustainability/.

- 122. Treisman R. Harvard University Will Stop Investing in Fossil Fuels After Years of Public Pressure. 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/09/10/1035901596/harvard-university-end-investment-fossil-fuel-industry-climate-change-activism.

- 123. Faircloth R. Under student pressure, University of Minnesota to Phase out Fossil Fuel Investments. 2021. https://www.startribune.com/under-student-pressure-university-of-minnesota-to-phase-out-fossil-fuel-investments/600100509/.

- 124. Rabin BM, Laney EB, Philipsborn RP. The unique role of medical students in catalyzing climate change education. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520957653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Jacobs E. Nurse Climate Champions Lead Hospital Sustainability Changes. 2020. https://www.hfmmagazine.com/articles/3843-nurse-climate-champions-lead-hospital-sustainability-changes.

- 126. Wirth TE, Heinz J, Stavins RN, . Project 88: Harnessing Market Forces to Protect Our Environment: Initiatives for the New President: A Public Policy Study. Vol. 52. Washington, DC: Environmental Policy Institute; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 127. Rummier O. The Major Police Reforms Enacted Since George Floyd’s Death. Arlington, VA: Axios; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 128. Ordner JP. Community action and climate change. Nat Clim Change. 2017;7(3):161–163. [Google Scholar]

- 129. Cook J, et al. Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. J Environ Res Lett. 2016;11:048002. [Google Scholar]

- 130. Begley S. Reality check on an embryonic debate. Newsweek. 2007;150(23):52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Aronoff K. Overheated: How Capitalism Broke the Planet—And How We Fight Back. New York, NY: Bold Type Books; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 132. Brulle RJ. The climate lobby: A sectoral analysis of lobbying spending on climate change in the USA, 2000 to 2016. Clim Change. 2018;149(3):289–303. [Google Scholar]

- 133. Michaels D. The Triumph of Doubt: Dark Money and the Science of Deception. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 134. Griffin P. The Carbon Majors Database: CDP Carbon Majors Report 2017. London, UK: Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) UK; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 135. Winters J, Teirstein Z. Report: Corporations Are Tanking America’s Best Shot at Fighting Climate Change. 2021. https://grist.org/accountability/report-corporations-are-tanking-americas-best-shot-at-fighting-climate-change/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&utm_campaign=weekly.

- 136. van der Linden S, Maibach E, Leiserowitz A. Improving public engagement with climate change: five “best practice” insights from psychological science. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(6):758–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. van Valkengoed AM, Steg L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat Clim Change. 2019;9(2):158–163. [Google Scholar]