Abstract

Epilepsy is a chronic non-infectious disease of the brain, characterized primarily by recurrent unprovoked seizures, defined as an episode of disturbance of motor, sensory, autonomic, or mental functions resulting from excessive neuronal discharge. Despite the advances in the treatment achieved with the use of antiepileptic drugs and other non-pharmacological therapies, about 30% of patients suffer from uncontrolled seizures. This review summarizes the currently available methods of gene and cell therapy for epilepsy and discusses the development of these approaches. Currently, gene therapy for epilepsy is predominantly adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated delivery of genes encoding neuro-modulatory peptides, neurotrophic factors, enzymes, and potassium channels. Cell therapy for epilepsy is represented by the transplantation of several types of cells such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), bone marrow mononuclear cells, neural stem cells, and MSC-derived exosomes. Another approach is encapsulated cell biodelivery, which is the transplantation of genetically modified cells placed in capsules and secreting various therapeutic agents. The use of gene and cell therapy approaches can significantly improve the condition of patient with epilepsy. Therefore, preclinical, and clinical studies have been actively conducted in recent years to prove the benefits and safety of these strategies.

Keywords: epilepsy, gene therapy, cell therapy, adeno-associated virus, mesenchymal stem cells, neural stem cells, mononuclear cells, encapsulated cell biodelivery

Introduction

Epilepsy is one of the most common diseases of the nervous system (more than 50 million cases have been reported worldwide). This condition is characterized by recurrent unprovoked seizures that result from abnormally excessive firing of neurons due to an imbalance in levels of excitation and inhibition in the brain (Stafstrom and Carmant, 2015). Epilepsy can have a variety of etiologies: structural, infectious, metabolic, immune, genetic as well as unknown (Perucca et al., 2020). Despite the active research in this area, the causes of the disease are still unclear. Epilepsy is also a group of conditions that are heterogeneous in manifestations and causes, making it difficult to develop unambiguous diagnostic criteria (Thijs et al., 2019). Patients suffer from seizures that often worsen over time and is accompanied by cognitive function deterioration and mental health problems. Patients often become resistant to existing antiepileptic drugs (Sheng et al., 2018).

The production of effective methods of treatment is an urgent problem that requires an immediate solution since epilepsy is a serious medical and social problem. The risk of premature death in people with epilepsy is three times higher than in the general population (according to WHO1).

Currently, gene and cell therapy is being investigated as a way to reduce neuronal loss, inflammation, oxidative stress, and the frequency and duration of epileptic seizures. The new approaches being developed are capable of increasing the survival of neurons, improving neurogenesis, providing neuroprotection and preserving cognitive functions.

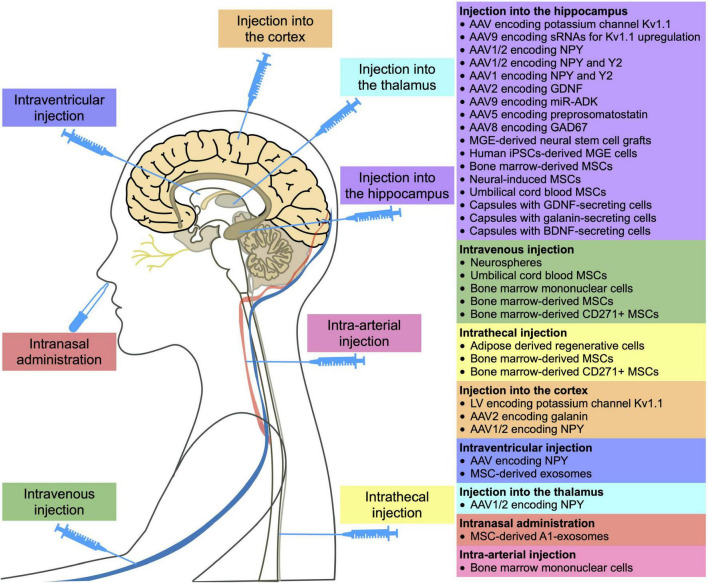

Thus, this paper discusses the promising results of gene and cell therapy for epilepsy. Table 1 and Figure 1 provide detailed information on existing in vivo studies and clinical trials.

TABLE 1.

Gene and cell therapy for epilepsy.

| Therapeutic agent | Model | Dose and duration | Therapy results | References |

| GENE THERAPY | ||||

| LV encoding potassium channel Kv1.1 | Rat model of tetanus toxin- induced epilepsy | Single injection of 1–1.5 mL of LV [2.6 × 109 viral genomes (vg/mL)] into layer 5 of the right motor cortex | Decrease in the frequency of seizures over several weeks | Wykes et al., 2012 |

| AAV encoding potassium channel Kv1.1 | Rat model of kainic acid-induced status epilepticus | Single injection of 8.0 μl of AAV (8.3 × 1014 vg/mL) into dorsal and ventral hippocampus | Decrease in the frequency and duration of seizures | Snowball et al., 2019 |

| AAV9 encoding small guide RNAs for Kv1.1 upregulation | Mouse model of kainic acid-induced status epilepticus | Single injection of 300 nL of AAV9 (8 × 1012 vg/ml) into right ventral hippocampus | Decrease in the frequency of spontaneous generalized seizures | Colasante et al., 2020 |

| AAV1/2 encoding NPY | Rat model of kainate-induced seizures | Single injection of 2 μl of AAV2 (1012 vg/mL) into dorsal hippocampus | Decrease in the frequency of kainate-induced seizures | Gotzsche et al., 2012 |

| AAV encoding NPY | Rat model of kainate-induced seizures | Single injection of 10 μL of AAV (5 × 1011 vg/mL) into the right lateral ventricle | Decrease in the frequency of kainate-induced seizures | Dong et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013 |

| AAV1/2 encoding NPY and Y2 | Rat model of kainate-induced seizures | Single injection of 1 μl of AAV-NPY (1012 vg/mL) and 1.5 μl of AAV-Y2 (1012 vg/mL) into dorsal and ventral hippocampus | Decrease in the frequency of kainate-induced seizures | Ledri et al., 2016 |

| AAV1/2 encoding NPY | Rat model of genetic generalized epilepsy | Single injection of 3 μl of AAV (6.6 × 1012 vg/ml) into thalamus and 1 μl into SC | Decrease in the frequency and duration of seizures in the thalamus, decrease in the frequency of seizures in the SC | Powell et al., 2018 |

| AAV1 encoding NPY and Y2 | Rat model of kainate-induced seizures | Single injection of 3 μL of AAV (1012 vg/mL) into hippocampus | Decrease in the frequency of seizures | Melin et al., 2019 |

| AAV2 encoding GDNF | Rat model of kindling-induced epilepsy | Single injection of 1 and 2 μl of virus (2.1 × 1012 vg/mL) into dorsal and ventral hippocampus | Decrease in the frequency of seizures, increase in seizure induction threshold | Kanter-Schlifke et al., 2007 |

| AAV9 encoding miR-ADK | Rat model of kainate-induced seizures | Single injection of 3 μL of AAV (9.48 × 1011 vg/mL) vector infused into hippocampus | Decrease in the frequency of seizures, protection of dentate hilar neurons | Young et al., 2014 |

| AAV5 encoding preprosomatostatin | Rat model of kindling-induced epilepsy | Single injection of 2 μL of AAV (4.19 × 1013 vg/mL) into the left and right CA1 region and dentate gyrus | Development of seizure resistance in 50% of animals | Natarajan et al., 2017 |

| AAV8 encoding GAD67 | The EL/Suz mouse model of epilepsy | Single injection of 3 μL of AAV (1 × 1010 vg/mL) bilaterally into the CA3 region of hippocampus | Significant reduction in seizure generation | Shimazaki et al., 2019 |

| AAV2 encoding galanin | Rat model of kainate-induced seizures | Single injection of 2 μl of AAV (8 × 1012 vg/mL) into the piriform cortex | Prevention of kainic acid-induced seizures | McCown, 2006 |

| CELL THERAPY | ||||

| Nervous system cells | ||||

| Intravenous infusion of neurospheres | Rat model of pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus | Single intravenous injection of 2 × 106 cells | Decrease in the oxidative stress damage | de Gois da Silva et al., 2018 |

| Transplantation of medial ganglionic eminence-derived neural stem cell grafts | Rat model of kainic acid-induced status epilepticus | Single transplantation of 4 grafts of 80,000 cells in each side of the hippocampus (640,000 cells/rat) | Suppression of spontaneous recurrent motor seizures, an increase in the number of GABAergic neurons, restoration of GDNF expression. No improvement in cognitive function | Waldau et al., 2010 |

| GABAergic interneuron precursors from the medial ganglionic eminence | Kv1.1 mutant mice | Bilateral transplantation into the deep layers of the cortex at two different sites on the hemisphere (4 × 105 cells/mouse) | Decrease in the duration and frequency of spontaneous electrographic seizures | Baraban et al., 2009 |

| Human iPSCs-derived medial ganglionic eminence cells | Mouse model of pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus | Transplantation of cells in the hippocampus (3 × 105 cells/mouse) | Suppression of seizures, aggressiveness, hyperactivity, improvement of cognitive function | Cunningham et al., 2014 |

| Human iPSCs-derived medial ganglionic eminence cells | Rat model of kainic acid-induced status epilepticus | Single transplantation of 3 grafts of 100,000 cells in each side of the hippocampus (600,000 cells/rat) | Relief of spontaneous recurrent seizures, improvement of cognitive function and memory, reduction in the loss of interneurons | Upadhya et al., 2019 |

| MSCs | ||||

| Undifferentiated autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs (in combination with anti-epileptic drugs) | Patients with epilepsy | Single intravenous injection of 1–1.5 × 106 cells/kg and single intrathecal injection of 1 × 105 cells/kg after 5–7 days | No serious side effects. Reduction in frequency or complete stop of seizures, improvement of clinical manifestations | Hlebokazov et al., 2017; Hlebokazov et al., 2021 NCT02497443 |

| Adipose derived regenerative cells | Patients with autoimmune refractory epilepsy | Intrathecal injection of 4 ml of stromal fraction, 3 times every 3 months | Complete remission in 1 of 6 patients (within 3 years), mild and short-term reduction in seizure (3 of 6 patients). Improvement in patients’ daily functioning. No further regression was observed for 3 years | Szczepanik et al., 2020 NCT03676569 |

| Bone marrow-derived CD271+ MSCs and bone marrow MSCs | Pediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy | Combination therapy consisting of single intrathecal (0.5 × 109) and intravenous (0.38 × 109–1.72 × 109) injections of bone marrow-derived CD271+ MSC and four intrathecal injections of bone marrow MSC (18.5 × 106–40 × 106) every 3 months | Neurological and cognitive improvement, decrease in the frequency of seizures | Milczarek et al., 2018 |

| Bone marrow-derived MSCs | Rat model of pilocarpine- induced status epilepticus | Single intravenous injection of 3 × 106 cells/rat | Decrease in the frequency of seizures, increase in the number of neurons | Abdanipour et al., 2011 |

| Bone marrow-derived MSCs | Rat model of lithium-pilocarpine- induced epilepsy | Single intravenous injection of 106 cells/rat | Inhibition of epileptogenesis and improvement of cognitive functions | Fukumura et al., 2018 |

| Bone marrow-derived MSCs | Rat model of pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus | Single injection of 100,000 cells in each side of the hippocampus (200,000 cells/rat) or single intravenous injection of 3 × 106 cells/rat | Reduction of oxidative stress in the hippocampus, decrease in the levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) and an apoptotic marker (caspase 3). Improvement of neurochemical and pathological changes in the brain | Salem et al., 2018 |

| Neural-induced adipose-derived stem cells | Rat model of kainic acid-induced status epilepticus | Single transplantation into the hippocampus (50,000 cells/rat) | Decrease in seizure activity, recovery of memory and learning ability | Wang et al., 2021 |

| Umbilical cord blood MSCs | Rat model of pentylenetetrazole-induced chronic epilepsy | Single intravenous injection (106 cells/rat) | Decrease in the severity of seizures and oxidative stress damage, improved motor coordination and cognitive function | Mohammed et al., 2014 |

| Umbilical cord blood MSCs | Rat model of lithium-pilocarpine induced status epilepticus | Single transplantation into the hippocampus (5 × 105 cells/rat) | Partial restoration of glucose metabolism in the hippocampus, seizure frequency did not differ from the control group | Park et al., 2015 |

| Exosomes | ||||

| MSC-derived exosomes | Mouse model of pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus | Single intraventricular injection (30 μg) | Reduction in the intensity of manifestation of reactive astrogliosis and inflammatory response, improvement in cognitive functions and memory | Xian et al., 2019 |

| MSC-derived A1-exosomes | Mouse model of pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus | Two intranasal administrations after 18 h (15 μg) | Reduction in the loss of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons, reduction in the inflammation, support of normal hippocampal neurogenesis, cognitive function, and memory | Long et al., 2017 |

| Mononuclear cells | ||||

| Bone marrow mononuclear cells | Patients with temporal lobe epilepsy | Single intra-arterial injection (1.52–10 × 108 cells/patient) | Decrease in the number of seizures, increase in average memory indicators. Complete disappearance of seizures in 40% of patients | DaCosta et al., 2018 NCT00916266 |

| Bone marrow mononuclear cells | Rat model of lithium-pilocarpine induced status epilepticus | Single intravenous injection (1 × 106 cells/rat) | Prevention of spontaneous recurrent seizures in the early stage of epilepsy, a significant reduction in the frequency and duration of seizures in the chronic phase | Costa-Ferro et al., 2010 |

| Bone marrow mononuclear cells | Mouse model of pilocarpine- induced status epilepticus | Single intravenous injection (2 × 106 cells/mouse) | Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects, decrease in the loss of hippocampal neurons | Leal et al., 2014 |

| Encapsulated cell biodelivery | ||||

| Semipermeable capsule containing GDNF-secreting ARPE-19 cells (arising retinal pigment epithelia cells) | Rat model of pilocarpine- induced status epilepticus | Transplantation in the hippocampus (5 × 104 cells/capsule). GDNF concentration up to 566.79 ± 192.47 ng/24 h | Decrease in the frequency of seizures, cognitive function improvement, neuroprotective effect | Paolone et al., 2019 |

| Semipermeable capsule containing GDNF-secreting cells | Rat model of kindling-induced epilepsy | Transplantation in the hippocampus. High GDNF concentration –150.92 ± 44.51 ng/ml/24 h, low concentration – 0.04 ± 0.88 ng/ml/24 h | Low GDNF levels have an antiepileptic effect compared to elevated levels | Kanter-Schlifke et al., 2009 |

| Semipermeable capsule containing galanin-secreting ARPE-19 cells | Rat model of kindling-induced epilepsy | Transplantation in the hippocampus (6 × 104 cells/capsule) High galanin concentration – 12.6 ng/ml/24 h, low concentration – 8.3 ng/ml/24 h | High doses decrease the duration of focal seizures | Nikitidou et al., 2014 |

| Semipermeable capsule containing BDNF-secreting ARPE-19 cells | Rat model of pilocarpine- induced status epilepticus | Transplantation in the hippocampus (5 × 104 cells/capsule). BDNF concentration – 200–400 ng/24 h | Decrease in the frequency of seizures. Cognitive function improvement | Falcicchia et al., 2018 |

| Semipermeable capsule containing BDNF-secreting baby hamster kidney cells | Rat model of pilocarpine- induced status epilepticus | Transplantation in the hippocampus (106 cells/capsule) BDNF concentration – 7.2 ± 1.2 ng/24 h | Injection of low doses had a neuroprotective effect and stimulated neurogenesis | Kuramoto et al., 2011 |

FIGURE 1.

Methods of administration of gene and cell drugs for epilepsy reported in in vivo and clinical studies.

Gene Therapy

The current focus of gene therapy strategies for epilepsy is primarily aimed at reducing neuronal excitability by overexpressing neuro-modulatory peptides such as neuropeptide Y (Dong et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013), galanin etc. (McCown, 2006) or by the genetic modification of astrocytes, for example, to suppress adenosine kinase (ADK) expression (Young et al., 2014).

Overexpression of ion channels such as the Kv1 potassium channel, which reduces the intrinsic excitability of neurons, increases the threshold for action potential generation required for neuron firing. Thus, permanent inhibition of the increased internal excitability of neurons inside the epileptic focus may have a long-term antiepileptic effect (Snowball et al., 2019). In a rat model of chronic refractory focal neocortical epilepsy, a lentivirus encoding Kv1.1 was shown to suppress epileptic activity for several weeks upon injection into an epileptic focus (Wykes et al., 2012). In addition, the use of adeno-associated virus (AAV) overexpressing Kv1.1 has resulted in a decrease in both the frequency and duration of seizures in the temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) model (Snowball et al., 2019). CRISPRa-mediated Kv1.1 upregulation decreased spontaneous generalized seizures in the mouse model of TLE (Colasante et al., 2020).

Another approach in antiepileptic treatment is the suppression of the activity of the excitatory mediator glutamate. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) preferentially binds to three G-protein coupled receptors (Y1, Y2, and Y5). Furthermore, the antiepileptic effect of NPY in the hippocampus is mediated by binding of NPY with presynaptic Y2 or Y5 receptors, which subsequently suppress glutamate release at excitatory synapses (Berglund et al., 2003). Binding of NPY to Y1 receptors leads to an increase in the epileptic activity (Benmaamar et al., 2003). Thus, genetic modification of the hippocampus by viruses with NPY can reduce the frequency of spontaneous seizures by 40% in both the TLE model (Noe et al., 2008) and kainate-induced seizures model (Dong et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). Additionally, AAV-NPY was shown to have therapeutic effects when injected into the thalamus or somatosensory cortex (SC) of genetic epilepsy model rats (Powell et al., 2018). In addition to viruses encoding the NPY, viruses encoding the receptors for this protein have also been administered to suppress seizures, which significantly increased the antiepileptic effect. For example, the injection of AAV1/2 with the NPY and Y5 significantly reduced the number of kainate-induced seizures (Gotzsche et al., 2012). The use of AAV1/2 viral vector encoding the NPY in combination with Y2 resulted in the reduction in the number of kainate-induced seizures by 31–45% (Ledri et al., 2016; Melin et al., 2019). The mechanisms of the antiepileptic effect of NPY are still unclear. However, overexpression of NPY is known to result in the expression of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits NR1, NR2A, and NR2B, which plays a critical role in the development of epilepsy (Dong et al., 2013). Moreover, the level of the synaptophysin protein, whose expression increased in the hippocampus of patients with epilepsy, was also decreased in the kainate-induced seizures model (Zhang et al., 2013). Overexpression of NPY has been studied in limited studies. Some studies have shown no effect on short- or long-term memory (Szczygiel et al., 2020), while others have illustrated that NPY decreases synaptic plasticity and negatively affects hippocampal-based spatial discrimination learning (Sorensen et al., 2008).

In addition to the treatment approaches described above, AAVs are actively being used to deliver proteins with therapeutic properties. Nevertheless, these are primarily in vivo studies that have not yet been further developed. For example, the introduction of AAV encoding the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) gene or the γ-aminobutyric acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67) gene reduced the seizure frequency in the TLE model (Kanter-Schlifke et al., 2007; Shimazaki et al., 2019). Moreover, promising results were demonstrated for AVVs encoding preprosomatostatin injected into the hippocampus (Natarajan et al., 2017).

Astrocyte transduction using AAV9 differs from the approach based on genetic modification of neurons described above. For example, miR-mediated suppression of ADK expression in astrocytes allowed an increase in the concentration of adenosine, which plays a pivotal role in seizure termination, and led to a decrease in the duration of kainate-induced seizures (Young et al., 2014).

A potential limitation of the viral vectors for the treatment of epilepsy is that viruses can transduce not only the epileptic focus cells, but also surrounding brain areas, so it can be difficult to determine the optimal dosage to achieve a therapeutic effect without impairing normal brain function. These difficulties can be overcome by a new strategy for creating a group of G-protein coupled receptors called designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs). DREADD technology is based on mutated human muscarinic receptors, which, when expressed in cells, can only be specifically bound and activated by the pharmacologically inert compounds, such as clozapine-N-oxide (CNO). Systemic administration of CNO leads to the opening of Gi-protein gated inwardly rectifying potassium channels, resulting in membrane hyperpolarization and neuronal inhibition. The efficacy of DREADDs has already been confirmed in a number of therapeutically relevant animal models of epilepsy (Lieb et al., 2019). For example, injection of AAV5 expressing a synthetic receptor hM4Di into the dorsal hippocampus of rats with pilocarpine-induced epilepsy led to a significantly reduction of seizures (Katzel et al., 2014). Another limiting factor is the high invasiveness of virus injection methods. In addition, even the most non-immunogenic AAV-based vectors are capable of inducing both humoral and cellular immune responses, which can greatly influence the outcome of gene therapy, since neutralizing antibodies can bind the viral particles and significantly reduce the transduction efficiency (Ronzitti et al., 2020). Some viral vectors can also lead to insertional mutagenesis due to genome integration (Athanasopoulos et al., 2017). In addition, the capacity of the vector is of great importance. For example, AAVs can only package ∼4.7 kb of DNA (Weinberg and McCown, 2013).

In gene therapy for epilepsy, the use of AAVs encoding potassium channel or NPY genes are the most investigated. However, the evaluation of the effectiveness of these therapeutic agents has not gone beyond in vivo animal systems. To date, there are no registered clinical trials aimed at investigating gene drugs for the treatment of epilepsy. In this regard, we can say that gene therapy is at an early stage of development and obviously requires more attention from researchers.

Cell Therapy

Cell therapy for epilepsy includes a variety of approaches, including the use of MSCs (Abdanipour et al., 2011; Mohammed et al., 2014; Park et al., 2015; Hlebokazov et al., 2017, 2021; Fukumura et al., 2018; Salem et al., 2018; Melin et al., 2019; Szczepanik et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021), mononuclear cells (Costa-Ferro et al., 2010; Leal et al., 2014; DaCosta et al., 2018), cells of the nervous system (Baraban et al., 2009; Waldau et al., 2010; Cunningham et al., 2014; de Gois da Silva et al., 2018; Upadhya et al., 2019), and encapsulated cells expressing various therapeutic factors (Kanter-Schlifke et al., 2009; Kuramoto et al., 2011; Nikitidou et al., 2014; Falcicchia et al., 2018; Paolone et al., 2019), as well as exosomes (Long et al., 2017; Xian et al., 2019). Cell therapy is an alternative treatment that can be used to reduce the incidence rate of seizures in epilepsy, including drug-resistant epilepsy, as shown in several clinical studies (Hlebokazov et al., 2017, 2021; DaCosta et al., 2018; Milczarek et al., 2018; Szczepanik et al., 2020).

Transplantation of Neural Cells

Promising approaches for epilepsy treatment are aimed at replenishing the neuronal loss in the hippocampus by transplanting cells of the nervous system. The neural stem cell is capable of self-renewal and differentiation into neurons, glial cells, and oligodendrocytes as well as expression of neurotrophic factors. Transplantation of neural stem cells into the hippocampus of epileptic rats led to an increase in the number of GABAergic neurons and cells expressing GDNF, which resulted in the suppression of seizures (Waldau et al., 2010).

The protective role of neurospheres, which are spherical clusters of neural stem cells grown in vitro, have also been studied. Intravenous administration of neurospheres into epileptic rats has been shown to reduce oxidative damage by significantly increasing the level of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione, superoxide dismutase and catalase (de Gois da Silva et al., 2018).

It has been shown that progenitor cells from embryonic medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) can differentiate into functional GABAergic interneurons. Transplantation of MGE precursors into the cortex of model mice with a deletion of potassium channels led to a significant reduction in the duration and frequency of spontaneous electrographic seizures, which is achieved due to GABA-mediated synaptic inhibition (GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter) (Baraban et al., 2009).

GABAergic interneurons can be derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). It has been shown that transplantation of pluripotent stem cell-derived GABAergic interneurons into the hippocampus of model animals led to a decrease in seizures and other behavioral abnormalities (Cunningham et al., 2014; Upadhya et al., 2019).

Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have many therapeutic properties useful in epilepsy, including neuroprotection, immunomodulation, neurogenesis support, inflammation, and oxidative stress damage suppression. These effects are achieved due to the fact that MSCs secrete various neurotrophic factors, anti-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors and other biologically active molecules (Vizoso et al., 2017; Milczarek et al., 2018). It is also known that MSCs can cross the blood-brain barrier and migrate to the affected area. Even after intravenous administration, MSCs migrate into the hippocampus of model animals with epilepsy and have a therapeutic effect (Abdanipour et al., 2011).

Numerous studies have shown that the administration of undifferentiated MSCs can significantly decrease the frequency of seizures (Hlebokazov et al., 2017, 2021; Milczarek et al., 2018; Szczepanik et al., 2020), improve cognitive (Fukumura et al., 2018; Milczarek et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021) and motor functions (Mohammed et al., 2014), increase the number of neurons (Abdanipour et al., 2011), reduce oxidative stress (Salem et al., 2018). The introduction of MSCs promotes the survival of GABAergic interneurons (Mohammed et al., 2014; Fukumura et al., 2018).

It has been shown that MSCs begin to secrete BDNF, NT3, and NT4 after neuronal differentiation. Their transplantation into the hippocampus of rats with kainic acid-induced epilepsy led to an increase in the level of BCL-2 and BCL-XL anti-apoptotic proteins and a decrease in the level of BAX pro-apoptotic protein in the hippocampus. Suppression of seizure activity and restoration of learning ability have also been noted (Wang et al., 2021).

The results of clinical studies also confirm benefits of MSC transplantation. For example, phase I/II clinical trials have demonstrated that the administration of antiepileptic drugs along with one or two intravenous and intrathecal administrations of MSCs has been safe and effective in treating patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Combined use of levetiracetam (an antiepileptic drug) and MSCs led to a decrease in the frequency of seizures, and a repeated course of MSC administration contributed to a further improvement in the patients’ condition (NCT02497443) (Hlebokazov et al., 2017, 2021).

A combination therapy has also been used for pediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. The intrathecal and intravenous administration of autologous bone marrow nucleated cells, followed by four intrathecal injections of MSCs every 3 months, resulted in neurological and cognitive improvement in all patients, including a decrease in the number of seizures (Milczarek et al., 2018).

Intrathecal administration of adipose-derived regenerative cells (a heterogeneous population of cells, including multipotent stem cells, fibroblasts, regulatory T-cells, and macrophages) into patients with autoimmune refractory epilepsy (3 times every 3 months) has also been reported. Only 1 out of 6 patients achieved complete remission (there were no seizures for more than 3 years), in 3 out of 6 there was a slight and short-term decrease in the frequency of seizures, and in two out of six no effect was found (Szczepanik et al., 2020). In all these clinical studies, some improvement after the introduction of cells without serious side effects was observed.

Exosome Injection

Not only MSCs, but also exosomes derived from them, exhibit immunoregulatory, anti-inflammatory and trophic effects (Harrell et al., 2019; Ha et al., 2020; Xunian and Kalluri, 2020), which means they also have great potential for the treatment of nervous systems diseases (Gorabi et al., 2019; Guy and Offen, 2020). As a result of intraventricular injection of exosomes, hippocampal astrocytes are able to take up the exosomes and attenuate astrogliosis and inflammation in model mice (Xian et al., 2019). After intranasal administration, exosomes also were able to reach the hippocampus, reduce the loss of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons, and significantly reduce inflammation in the hippocampus of model animals (Long et al., 2017).

Mononuclear Cell Transplantation

Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMCs) also possess immunomodulatory and neuroprotective properties (Yoshihara et al., 2007; Shrestha et al., 2014; do Prado-Lima et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2020) due to the secretion of various trophic factors and cytokines (Liu et al., 2004; Wei et al., 2020).

It has been shown that after intravenous administration to animals with status epilepticus, BMCs can migrate to the hippocampus, reduce the frequency and duration of seizures, maintain neuronal density (Costa-Ferro et al., 2010), increase proliferation of neurons, reduce the level of inflammatory cytokines and increase the level of anti-inflammatory cytokines (Leal et al., 2014).

Phase I/II clinical trials have investigated the safety and efficacy of intra-arterial injection of BMCs in TLE patients. Researchers demonstrated safety, improved memory, a decrease in theta activity, and a decrease in spike density (DaCosta et al., 2018).

Encapsulated Cell Biodelivery

Despite the proven efficacy, gene and cell therapy methods have a number of known disadvantages and side effects. It should be noted that these methods of therapy are irreversible and unregulated, and some of them can lead to an immune response and malignant transformation.

In the case of cell therapy, as mentioned above for gene therapy, the major limiting factor is safety, specifically the possibility of a significant immune response induction and oncogenic transformation. In some cases, long-term immunosuppressive therapy and monitoring of the cells after the administration are required (Aly, 2020). It is important to select a suitable donor in the case of allogeneic transplantation, not only in terms of HLA compatibility, but also in the heterogeneity of effector molecules secreted by the cells, which vary considerably between different donors and can lead to a significant variation in the treatment efficacy (Montzka et al., 2009; Mukhamedshina et al., 2019). The migration ability of cells also imposes restrictions on the use of cell-based therapy in clinical practice since highly invasive cell delivery is sometimes required to reach the target area and cross the blood-brain barrier (Issa et al., 2020).

One of the approaches to overcome some of the difficulties of cell-based therapy is encapsulated cell biodelivery (ECB). ECB usually involves the implantation of a capsule with a semipermeable membrane containing genetically modified cells that secrete therapeutic substances. In this case, the cells do not leave the capsule, but the therapeutically active molecules leave and spread in the area of transplantation. This method allows (1) preventing an immune response and transplant rejection, since the cells are physically isolated, (2) locally delivering therapeutic substances, and (3) stopping treatment by removing the capsule from the brain. To suppress epileptic activity, such capsules were designed to contain cells expressing GDNF (Kanter-Schlifke et al., 2009; Paolone et al., 2019), BDNF (Kuramoto et al., 2011; Falcicchia et al., 2018), or galanin (Nikitidou et al., 2014). ECB has shown positive results in epilepsy therapy since these neurotrophic factors and neuropeptide exhibit antiepileptic activity.

Conclusion

This review discussed recent developments in gene and cell therapy for epilepsy. To date, in vivo models have shown the potential benefit of viral vectors (mainly AAVs, rarely LVs) encoding genes of therapeutic agents. Thus, the effectiveness of viral delivery of (1) neuro-modulatory peptides, such as NPY or galanin, (2) potassium channels to inhibit increased internal excitability of neurons, (3) GDNF, (4) GAD67, (5) preprosomatostatin, as well as (6) miR to suppress ADK expression has been shown.

Cell-based therapy has made more progress with documented clinical trials showing the benefits and safety of MSC or BMC transplantation. The therapeutic effect can be achieved due to the neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory properties of these cells, which is also shown for MSC-derived exosomes. Researchers are also focusing on the transplantation of neural stem cells into the hippocampus to reduce neuronal loss in animal models. ECB, which is the injection of capsules with cells expressing BDNF, GDNF or galanin in the hippocampus, has shown an antiepileptic effect.

The majority of gene and cell therapies have not yet reached clinical practice, but they have made significant progress. To date, preclinical studies in animal model are ongoing and new clinical trials are being registered to confirm both the effectiveness and safety of these approaches. Considering the heterogeneous nature of the onset and manifestation of epilepsy, the development of methods of gene and cell therapy can make a significant contribution to progress in the treatment of this disease.

Author Contributions

AS, DC, VS, and AR: conceptualization. AS and DC: writing-original draft preparation. VS, AM, RG, ZA, and AR: writing-review and editing. AS: visualization. VS and AR: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Center for Precision Genome Editing and Genetic Technologies for Biomedicine, IGB RAS for scientific advice on development of gene therapy drugs. This article has been supported by the Kazan Federal University Strategic Academic Leadership Program (PRIORITY-2030).

Footnotes

Funding

This work was funded by the subsidy allocated to KFU for the state assignment 0671-2020-0058 in the sphere of scientific activities.

References

- Abdanipour A., Tiraihi T., Mirnajafi-Zadeh J. (2011). Improvement of the pilocarpine epilepsy model in rat using bone marrow stromal cell therapy. Neurol. Res. 33 625–632. 10.1179/1743132810Y.0000000018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aly R. M. (2020). Current state of stem cell-based therapies: an overview. Stem Cell Investig. 7:8. 10.21037/sci-2020-001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasopoulos T., Munye M. M., Yanez-Munoz R. J. (2017). Nonintegrating Gene Therapy Vectors. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 31 753–770. 10.1016/j.hoc.2017.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraban S. C., Southwell D. G., Estrada R. C., Jones D. L., Sebe J. Y., Alfaro-Cervello C., et al. (2009). Reduction of seizures by transplantation of cortical GABAergic interneuron precursors into Kv1.1 mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106 15472–15477. 10.1073/pnas.0900141106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmaamar R., Pham-Le B. T., Marescaux C., Pedrazzini T., Depaulis A. (2003). Induced down-regulation of neuropeptide Y-Y1 receptors delays initiation of kindling. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18 768–774. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02810.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund M. M., Hipskind P. A., Gehlert D. R. (2003). Recent developments in our understanding of the physiological role of PP-fold peptide receptor subtypes. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 228 217–244. 10.1177/153537020322800301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasante G., Qiu Y., Massimino L., Di Berardino C., Cornford J. H., Snowball A., et al. (2020). In vivo CRISPRa decreases seizures and rescues cognitive deficits in a rodent model of epilepsy. Brain 143 891–905. 10.1093/brain/awaa045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Ferro Z. S., Vitola A. S., Pedroso M. F., Cunha F. B., Xavier L. L., Machado D. C., et al. (2010). Prevention of seizures and reorganization of hippocampal functions by transplantation of bone marrow cells in the acute phase of experimental epilepsy. Seizure 19 84–92. 10.1016/j.seizure.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M., Cho J. H., Leung A., Savvidis G., Ahn S., Moon M., et al. (2014). hPSC-derived maturing GABAergic interneurons ameliorate seizures and abnormal behavior in epileptic mice. Cell Stem Cell 15 559–573. 10.1016/j.stem.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaCosta J. C., Portuguez M. W., Marinowic D. R., Schilling L. P., Torres C. M., DaCosta D. I., et al. (2018). Safety and seizure control in patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy treated with regional superselective intra-arterial injection of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells. J. Tiss. Eng. Regen. Med. 12 e648–e656. 10.1002/term.2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gois da Silva M. L., da Silva, Oliveira G. L., de Oliveira Bezerra D., da Rocha, et al. (2018). Neurochemical properties of neurospheres infusion in experimental-induced seizures. Tissue Cell 54 47–54. 10.1016/j.tice.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Prado-Lima P. A. S., Onsten G. A., de Oliveira G. N., Brito G. C., Ghilardi I. M., de Souza E. V., et al. (2019). The antidepressant effect of bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in chronic stress. J. Psychopharmacol. 33 632–639. 10.1177/0269881119841562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C., Zhao W., Li W., Lv P., Dong X. (2013). Anti-epileptic effects of neuropeptide Y gene transfection into the rat brain. Neural Regen. Res. 8 1307–1315. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.14.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcicchia C., Paolone G., Emerich D. F., Lovisari F., Bell W. J., Fradet T., et al. (2018). Seizure-Suppressant and Neuroprotective Effects of Encapsulated BDNF-Producing Cells in a Rat Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 9 211–224. 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumura S., Sasaki M., Kataoka-Sasaki Y., Oka S., Nakazaki M., Nagahama H., et al. (2018). Intravenous infusion of mesenchymal stem cells reduces epileptogenesis in a rat model of status epilepticus. Epilep. Res. 141 56–63. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorabi A. M., Kiaie N., Barreto G. E., Read M. I., Tafti H. A., Sahebkar A. (2019). The Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 56 8157–8167. 10.1007/s12035-019-01663-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotzsche C. R., Nikitidou L., Sorensen A. T., Olesen M. V., Sorensen G., Christiansen S. H., et al. (2012). Combined gene overexpression of neuropeptide Y and its receptor Y5 in the hippocampus suppresses seizures. Neurobiol. Dis. 45 288–296. 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy R., Offen D. (2020). Promising Opportunities for Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases with Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes. Biomolecules 10:1320. 10.3390/biom10091320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha D. H., Kim H. K., Lee J., Kwon H. H., Park G. H., Yang S. H., et al. (2020). Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell-Derived Exosomes for Immunomodulatory Therapeutics and Skin Regeneration. Cells 9:1157. 10.3390/cells9051157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell C. R., Jovicic N., Djonov V., Arsenijevic N., Volarevic V. (2019). Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles as New Remedies in the Therapy of Inflammatory Diseases. Cells 8:1605. 10.3390/cells8121605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlebokazov F., Dakukina T., Ihnatsenko S., Kosmacheva S., Potapnev M., Shakhbazau A., et al. (2017). Treatment of refractory epilepsy patients with autologous mesenchymal stem cells reduces seizure frequency: An open label study. Adv. Med. Sci. 62 273–279. 10.1016/j.advms.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlebokazov F., Dakukina T., Potapnev M., Kosmacheva S., Moroz L., Misiuk N., et al. (2021). Clinical benefits of single vs repeated courses of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in epilepsy patients. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 207:106736. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa S., Shaimardanova A., Valiullin V., Rizvanov A., Solovyeva V. (2020). Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Lysosomal Storage Diseases and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 13:859516. 10.3389/fphar.2022.859516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter-Schlifke I., Fjord-Larsen L., Kusk P., Angehagen M., Wahlberg L., Kokaia M. (2009). GDNF released from encapsulated cells suppresses seizure activity in the epileptic hippocampus. Exp. Neurol. 216 413–419. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter-Schlifke I., Georgievska B., Kirik D., Kokaia M. (2007). Seizure suppression by GDNF gene therapy in animal models of epilepsy. Mol. Ther. 15 1106–1113. 10.1038/sj.mt.6300148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzel D., Nicholson E., Schorge S., Walker M. C., Kullmann D. M. (2014). Chemical-genetic attenuation of focal neocortical seizures. Nat. Commun. 5:3847. 10.1038/ncomms4847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto S., Yasuhara T., Agari T., Kondo A., Jing M., Kikuchi Y., et al. (2011). BDNF-secreting capsule exerts neuroprotective effects on epilepsy model of rats. Brain Res. 1368 281–289. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal M. M., Costa-Ferro Z. S., Souza B. S., Azevedo C. M., Carvalho T. M., Kaneto C. M., et al. (2014). Early transplantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells promotes neuroprotection and modulation of inflammation after status epilepticus in mice by paracrine mechanisms. Neurochem. Res. 39 259–268. 10.1007/s11064-013-1217-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledri L. N., Melin E., Christiansen S. H., Gotzsche C. R., Cifra A., Woldbye D. P., et al. (2016). Translational approach for gene therapy in epilepsy: Model system and unilateral overexpression of neuropeptide Y and Y2 receptors. Neurobiol. Dis. 86 52–61. 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb A., Weston M., Kullmann D. M. (2019). Designer receptor technology for the treatment of epilepsy. EBioMedicine 43 641–649. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.04.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Guo J., Zhang P., Zhang S., Chen P., Ma K., et al. (2004). Bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation into heart elevates the expression of angiogenic factors. Microvasc. Res. 68 156–160. 10.1016/j.mvr.2004.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Q., Upadhya D., Hattiangady B., Kim D. K., An S. Y., Shuai B., et al. (2017). Intranasal MSC-derived A1-exosomes ease inflammation, and prevent abnormal neurogenesis and memory dysfunction after status epilepticus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 114 E3536–E3545. 10.1073/pnas.1703920114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown T. J. (2006). Adeno-associated virus-mediated expression and constitutive secretion of galanin suppresses limbic seizure activity in vivo. Mol. Ther. 14 63–68. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melin E., Nanobashvili A., Avdic U., Gotzsche C. R., Andersson M., Woldbye D. P. D., et al. (2019). Disease Modification by Combinatorial Single Vector Gene Therapy: A Preclinical Translational Study in Epilepsy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 15 179–193. 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milczarek O., Jarocha D., Starowicz-Filip A., Kwiatkowski S., Badyra B., Majka M. (2018). Multiple Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived CD271(+) Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation Overcomes Drug-Resistant Epilepsy in Children. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 7 20–33. 10.1002/sctm.17-0041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed A. S., Ewais M. M., Tawfik M. K., Essawy S. S. (2014). Effects of intravenous human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cell therapy versus gabapentin in pentylenetetrazole-induced chronic epilepsy in rats. Pharmacology 94 41–50. 10.1159/000365219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montzka K., Lassonczyk N., Tschoke B., Neuss S., Fuhrmann T., Franzen R., et al. (2009). Neural differentiation potential of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells: misleading marker gene expression. BMC Neurosci. 10:16. 10.1186/1471-2202-10-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhamedshina Y., Shulman I., Ogurcov S., Kostennikov A., Zakirova E., Akhmetzyanova E., et al. (2019). Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Spinal Cord Contusion: A Comparative Study on Small and Large Animal Models. Biomolecules 9:811. 10.3390/biom9120811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan G., Leibowitz J. A., Zhou J., Zhao Y., McElroy J. A., King M. A., et al. (2017). Adeno-associated viral vector-mediated preprosomatostatin expression suppresses induced seizures in kindled rats. Epilepsy Res 130 81–92. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitidou L., Torp M., Fjord-Larsen L., Kusk P., Wahlberg L. U., Kokaia M. (2014). Encapsulated galanin-producing cells attenuate focal epileptic seizures in the hippocampus. Epilepsia 55 167–174. 10.1111/epi.12470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe F., Pool A. H., Nissinen J., Gobbi M., Bland R., Rizzi M., et al. (2008). Neuropeptide Y gene therapy decreases chronic spontaneous seizures in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain 131(Pt 6), 1506–1515. 10.1093/brain/awn079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolone G., Falcicchia C., Lovisari F., Kokaia M., Bell W. J., Fradet T., et al. (2019). Long-Term, Targeted Delivery of GDNF from Encapsulated Cells Is Neuroprotective and Reduces Seizures in the Pilocarpine Model of Epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 39 2144–2156. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0435-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park G. Y., Lee E. M., Seo M. S., Seo Y. J., Oh J. S., Son W. C., et al. (2015). Preserved Hippocampal Glucose Metabolism on 18F-FDG PET after Transplantation of Human Umbilical Cord Blood-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Chronic Epileptic Rats. J. Kor. Med. Sci. 30 1232–1240. 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.9.1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perucca P., Bahlo M., Berkovic S. F. (2020). The Genetics of Epilepsy. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 21 205–230. 10.1146/annurev-genom-120219-074937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell K. L., Fitzgerald X., Shallue C., Jovanovska V., Klugmann M., Von Jonquieres G., et al. (2018). Gene therapy mediated seizure suppression in Genetic Generalised Epilepsy: Neuropeptide Y overexpression in a rat model. Neurobiol. Dis. 113 23–32. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronzitti G., Gross D. A., Mingozzi F. (2020). Human Immune Responses to Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vectors. Front. Immunol. 11:670. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem N. A., El-Shamarka M., Khadrawy Y., El-Shebiney S. (2018). New prospects of mesenchymal stem cells for ameliorating temporal lobe epilepsy. Inflammopharmacology 26 963–972. 10.1007/s10787-018-0456-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J., Liu S., Qin H., Li B., Zhang X. (2018). Drug-Resistant Epilepsy and Surgery. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 16 17–28. 10.2174/1570159X15666170504123316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K., Kobari T., Oguro K., Yokota H., Kasahara Y., Murashima Y., et al. (2019). Hippocampal GAD67 Transduction Using rAAV8 Regulates Epileptogenesis in EL Mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 13 180–186. 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha R. P., Qiao J. M., Shen F. G., Bista K. B., Zhao Z. N., Yang J. (2014). Intra-Spinal Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells Transplantation Inhibits the Expression of Nuclear Factor-kappaB in Acute Transection Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. J. Kor. Neurosurg. Soc. 56 375–382. 10.3340/jkns.2014.56.5.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowball A., Chabrol E., Wykes R. C., Shekh-Ahmad T., Cornford J. H., Lieb A., et al. (2019). Epilepsy Gene Therapy Using an Engineered Potassium Channel. J. Neurosci. 39 3159–3169. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1143-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen A. T., Kanter-Schlifke I., Carli M., Balducci C., Noe F., During M. J., et al. (2008). NPY gene transfer in the hippocampus attenuates synaptic plasticity and learning. Hippocampus 18 564–574. 10.1002/hipo.20415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom C. E., Carmant L. (2015). Seizures and epilepsy: an overview for neuroscientists. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 5:a022426. 10.1101/cshperspect.a022426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepanik E., Mierzewska H., Antczak-Marach D., Figiel-Dabrowska A., Terczynska I., Tryfon J., et al. (2020). Intrathecal Infusion of Autologous Adipose-Derived Regenerative Cells in Autoimmune Refractory Epilepsy: Evaluation of Safety and Efficacy. Stem Cells Int. 2020:7104243. 10.1155/2020/7104243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczygiel J. A., Danielsen K. I., Melin E., Rosenkranz S. H., Pankratova S., Ericsson A., et al. (2020). Gene Therapy Vector Encoding Neuropeptide Y and Its Receptor Y2 for Future Treatment of Epilepsy: Preclinical Data in Rats. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 13:232. 10.3389/fnmol.2020.603409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thijs R. D., Surges R., O’Brien T. J., Sander J. W. (2019). Epilepsy in adults. Lancet 393 689–701. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32596-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhya D., Hattiangady B., Castro O. W., Shuai B., Kodali M., Attaluri S., et al. (2019). Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived MGE cell grafting after status epilepticus attenuates chronic epilepsy and comorbidities via synaptic integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 116 287–296. 10.1073/pnas.1814185115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizoso F. J., Eiro N., Cid S., Schneider J., Perez-Fernandez R. (2017). Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 1852. 10.3390/ijms18091852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldau B., Hattiangady B., Kuruba R., Shetty A. K. (2010). Medial ganglionic eminence-derived neural stem cell grafts ease spontaneous seizures and restore GDNF expression in a rat model of chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Stem Cells 28 1153–1164. 10.1002/stem.446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Zhao Y., Pan X., Zhang Y., Lin L., Wu Y., et al. (2021). Adipose-derived stem cell transplantation improves learning and memory via releasing neurotrophins in rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 1750:147121. 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.147121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Li L., Deng L., Wang Z. J., Dong J. J., Lyu X. Y., et al. (2020). Autologous Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cell Transplantation Therapy Improved Symptoms in Patients with Refractory Diabetic Sensorimotor Polyneuropathy via the Mechanisms of Paracrine and Immunomodulation: A Controlled Study. Cell Transplant. 29:963689720949258. 10.1177/0963689720949258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg M. S., McCown T. J. (2013). Current prospects and challenges for epilepsy gene therapy. Exp. Neurol. 244 27–35. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes R. C., Heeroma J. H., Mantoan L., Zheng K., MacDonald D. C., Deisseroth K., et al. (2012). Optogenetic and potassium channel gene therapy in a rodent model of focal neocortical epilepsy. Sci. Transl. Med. 4:161ra152. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian P., Hei Y., Wang R., Wang T., Yang J., Li J., et al. (2019). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as a nanotherapeutic agent for amelioration of inflammation-induced astrocyte alterations in mice. Theranostics 9 5956–5975. 10.7150/thno.33872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xunian Z., Kalluri R. (2020). Biology and therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Cancer Sci. 111 3100–3110. 10.1111/cas.14563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara T., Ohta M., Itokazu Y., Matsumoto N., Dezawa M., Suzuki Y., et al. (2007). Neuroprotective effect of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells promoting functional recovery from spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 24 1026–1036. 10.1089/neu.2007.132R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D., Fong D. M., Lawlor P. A., Wu A., Mouravlev A., McRae M., et al. (2014). Adenosine kinase, glutamine synthetase and EAAT2 as gene therapy targets for temporal lobe epilepsy. Gene Ther. 21 1029–1040. 10.1038/gt.2014.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Zhao W., Li W., Dong C., Zhang X., Wu J., et al. (2013). Neuropeptide Y gene transfection inhibits post-epileptic hippocampal synaptic reconstruction. Neural Regen. Res. 8 1597–1605. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.17.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]