Abstract

Objective:

Adolescents are at high risk for alcohol and cannabis use. Emerging evidence suggests that discrimination exposure is prospectively associated with risk for alcohol use among adolescents of marginalized race, sexual orientation, or gender identity. However, it is unknown whether prospective discrimination-substance use associations among marginalized adolescents is also present for cannabis use. This study examined prospective associations of race, sexual orientation, and discrimination exposure with alcohol and cannabis use over one year.

Methods:

Data were drawn from a two-wave longitudinal health survey study of 9-11th graders (n=350 for the current analyses; Year 1 Mage=15.95 [SD=1.07, range=13-19]; 44% male; 44% Black, 22% White, 18% Asian, 16% Multiracial; 16% LGB; 10% Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity) at an urban high school. Two multinomial logistic regressions examined associations of Year 1 race, sexual orientation, and discrimination experiences with Year 2 alcohol and cannabis consumption separately.

Results:

Year 1 Discrimination exposure was associated with increased risk for Year 2 past-year alcohol use among Asian (OR=1.34) and past-month alcohol use among Multiracial (OR=1.30) adolescents, but not Black or LGB adolescents. Discrimination exposure was not associated with any cannabis use pattern in any group. Independent of discrimination, LGB adolescents were at greater risk for monthly alcohol (OR=3.48) and cannabis use (OR=4.07) at Year 2.

Conclusions:

Discrimination exposure is prospectively associated with risk for alcohol use among adolescents of understudied (Asian, Multiracial) racial backgrounds, and should be considered in alcohol prevention and intervention strategies. Risk factors for alcohol and cannabis use among LGB adolescents should continue to be explored.

Keywords: alcohol, cannabis, substance use, discrimination, adolescent

Among US adolescents aged 12-18, 47% are people of color (POC; U. S. Census Bureau, 2017) and 15% are lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB; Kann et al., 2018). Substance use and risk disparities have been documented across adolescent racial and sexual orientation groups, albeit rarely within the same sample. Across racial groups, White and Multiracial adolescents endorse greater alcohol use (versus Black and Asian peers; Clark et al., 2013; Lipari, 2019), whereas Black (Johnson et al., 2019; Kann et al., 2018) and Multiracial (Goings et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2013) adolescents report greater cannabis use (versus White and Asian peers; Lipari, 2019). Further, cannabis use rates are rising among Black and Asian adolescents (but not among White adolescents; Kann et al., 2018; Lipari, 2019), and Black adolescents are on a trajectory toward more frequent episodic drinking and cannabis use by young adulthood (versus White peers), although parallel research for other racial groups remains lacking (Lanza et al., 2015). POC adolescents may likewise experience greater substance-related risk, including increased risk of assault (Harford et al., 2016), risky sexual behavior (Everett et al., 2014), development of a substance use disorder (Mulia et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2014), and substance-related consequences across the lifespan (Green et al., 2017; Mulia et al., 2009).

Risk disparities affecting POC adolescents are paralleled in LGB adolescents. Compared to straight peers, LGB adolescents are more likely to initiate use of alcohol and cannabis during adolescence (Amos et al., 2020), report greater lifetime and current alcohol and cannabis use (Kann et al., 2018; Mereish et al., 2017), and engage in persistent, hazardous alcohol/cannabis use through late adolescence and early adulthood (Dermody et al., 2014; Talley et al., 2019). Further, substance use among LGB adolescents has been associated with increased risk of substance-related consequences across the lifespan (Dermody et al., 2014), as well as increased risk of proximal assault (Duncan et al., 2014) and risky sexual behavior (Hong et al., 2019).

Discrimination: A Risk Factor of Alcohol/Cannabis Disparities

Substance use disparities may be attributable to discrimination, or prejudicial treatment based on race, ethnicity, and/or sexual orientation (Desalu et al., 2019; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Between 79-90% of POC (Cheon & Yip, 2019; Pachter et al., 2018) and 71% of LGB (The Trevor Project, 2019) adolescents report past-year discrimination experiences. Experiencing discrimination may increase substance use, even among sub-groups typically less likely to cope using substances (e.g., Asians; Le & Iwamoto, 2019). The temporary relief of negative affect granted by substance use reinforces this coping tool (van der Zwaluw et al., 2011), promoting increased use and negative consequences over time among marginalized adolescents.

Indeed, race- and sexual orientation-based discrimination (versus other sources of marginalization) is most strongly associated with adolescent substance use (e.g., alcohol; for a review, see Gilbert & Zemore, 2016). Discrimination has been associated with greater alcohol and cannabis use among Black (Brody et al., 2012), Hispanic/Latinx (Cano et al., 2015), and Multiracial (Goodhines, Desalu, et al., 2020) adolescents. However, most research on discrimination-alcohol relationships among POC adolescents has focused exclusively on one racial group at a time (most commonly Black or African-American adolescents; e.g., Brody et al., 2012), neglecting Asian and Multiracial adolescents (Gilbert & Zemore, 2016). Across all racial groups, discrimination-cannabis relationships remain unexplored.

While discrimination is a theoretically indicated risk factor for adolescent substance use, and it has been shown that LGB adolescents who experience overt victimization because of their sexual orientation are more likely to engage in substance use (Goldbach et al., 2014), how perceived discrimination (a more covert, subjective construct) is associated with adolescent substance use remains under-researched. Independently, LGB adolescents are more likely than straight peers to experience discrimination (Amos et al., 2020) and use substances (including alcohol, cannabis, sedatives, and misused prescription medication; Amos et al., 2020; Huebner et al., 2015; Mereish et al., 2017), although explicit associations of discrimination with substance use in LGB adolescents have yet to be explored. However, among LGB adults, discrimination exacerbates alcohol and cannabis use disparities (Bränström & Pachankis, 2018), which may generalize to adolescent samples. Additionally, despite racially-diverse samples (i.e., Huebner et al., 2015; Mereish et al., 2017), research on LGB youth often lacks concurrent attention toward other sources of marginalization (Institute of Medicine, 2011) such as race.

The chronic stress of discrimination exposure has been associated with heightened perceptions of stress and acute increases in hypothalamic-pituitary axis activation (Hittner & Adam, 2020), ultimately leading to dysregulation of neurobiological stress systems and subsequent maladaptive cognitions and behaviors (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). Additionally, the comparative lack of alternative coping resources accessible to marginalized adolescents as compared with their majority peers (Meyer et al., 2008), such as social or structural support (e.g., access to racially- or sexual orientation-affirming spaces in schools), has been linked with stronger associations of discrimination with diverse negative health behaviors of adolescents of marginalized race and/or sexual orientation (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Walsh et al., 2018). The association between discrimination and adverse health behaviors, such as substance use, thus appears to be stronger among marginalized than nonmarginalized adolescents (Walsh et al., 2018).

Current Study

This two-wave one-year longitudinal study assessed whether associations of discrimination with alcohol/cannabis use differed by racial group or LGB status among adolescents. This study sought evidence for a common risk factor, namely discrimination, which could underlie substance use disparities observed in both racial and sexual minority groups. Building off prior discrimination-alcohol associations observed among adolescents of color, this study aimed to expand prior findings to include LGB adolescents. Further, it sought to explore whether a similar discrimination-substance association also exists for cannabis among diverse adolescents. Overall, it was hypothesized that associations of higher (versus lower) levels of discrimination with alcohol/cannabis use would be more strongly positive among POC (versus White) and LGB (versus straight) adolescents.

Methods

Participants

Data were drawn from a two-wave study of health behavior among 414 adolescents (Mage=16.00 [SD=1.08], 43% male) at an urban public high school in the northeastern United States (Goodhines, Desalu, et al., 2020; Goodhines, Taylor, et al., 2020). Students were eligible if they were English-speaking and in 9-11th grade at enrollment; 12th graders were ineligible due to expected graduation by follow-up.

Of the 414 participants at Year 1 (Y1), data from 350 participants (85% of the Y1 sample) were used for the current analyses, after excluding participants who did not participate in the follow-up assessment (Year 2 [Y2], n=47), membership in Pacific Islander or Native American racial groups too small to analyze (n=9), declining to endorse sexual orientation (n=2), or missing data on the Y1 discrimination experience variable (n=6). The final sample of 350 participants were on average 15.95 years old (SD=1.06), and racially and ethnically diverse (44% Black or African American, 22% White, 18% Asian, and 16% Multiracial, and 10% Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity regardless of race). The final sample consisted of 44% biological male sex (vs. female sex), and 14% LGB (4% gay/lesbian, 10% bisexual). The sample also demonstrated considerable socioeconomic disadvantage (83% eligible for free/reduced-price lunch, 26% primary caregiver without a high school diploma, and 78% living in a neighborhood where ≥20% of residents fell below the federal poverty line [U. S. Census Bureau, 2017]).

Compared to participants who provided completed Y1 and Y2 (n=350, 85%), those who did not complete Y2 (n=64, 16%) were more likely to be older, (t[410]=2.07, p=.039, Cohen’s d=.26), to be Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity (χ2[1]=7.96, p=.005, Cramer’s V=.14), and to report greater frequency of discrimination (t[402]=4.36, p < .001, Cohen’s d=.54), past-year alcohol use frequency (t[406]=3.09, p=.002, Cohen’s d=.39), and past-year cannabis use frequency (t[406]=3.62, p<.001, Cohen’s d=.39). Groups did not significantly differ by race, sexual orientation, or socioeconomic status (ps>.05).

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the IRB and the school district where data was collected. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health to protect sensitive information (e.g., illicit substance use). Written informed assent and guardian consent were obtained from all enrolled participants. Participants completed online surveys assessing diverse health behaviors at Y1 and Y2 (Minterval=389 days [SD=27.41]). Students were compensated with gift cards up to $15 at Y1 survey and $20 at Y2, and extra credit at individual teachers’ discretion.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics.

Age, sex assigned at birth (0=female, 1=male), and ethnicity (0=not Hispanic/Latinx, 1=Hispanic/Latinx) were assessed at Y1, and were included as covariates given associations with adolescent alcohol/cannabis use (Cano et al., 2015). Eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch (0=ineligible, 1=eligible) was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status (Nicholson et al., 2014) and included as a covariate given associations with discrimination and related health outcomes (Fuller-Rowell et al., 2018).

Race.

Race was assessed at Y1 via a single item (i.e., “What race do you consider yourself to be? Race is a group of people who have similar and distinct physical characteristics”; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). For analyses involving race, three dummy variables (i.e., Black/African American, Asian, and Multiracial) were created with White as the reference group.

Sexual orientation.

Sexual orientation was assessed at Y1 via a single item (0=straight, 1=lesbian/gay, 2=bisexual; Badgett et al., 2009). Sexual orientation was aggregated into one LGB status variable (0=straight, 1=LGB) to accommodate low endorsement precluding group comparison (n=14 lesbian/gay, n=35 bisexual).

Alcohol use.

Three items (Johnston et al., 1997) assessed lifetime, past-year, and past-month alcohol use frequencies at Y1 and Y2. Response options ranged from 0 (Never or 0 occasions) to 6 (40 or more occasions). Response variability within individual items was limited, because few participants endorsed high-frequency use, resulting in excess zeroes and positive skew of non-zero responses. However, the limited range of non-zero responses prevented the use of approaches tailored to deal with similar data distributions (e.g., zero-inflated negative binomial regression; Atkins et al., 2013). In contrast to the limited variabilities within individual items, variabilities in responses across items (e.g., differences in past-year frequency among lifetime drinkers) were substantial. Thus, an ordinal composite variable was computed using responses to these three items at Y2 (0=Lifetime alcohol abstainers, 1=Lifetime, but not past-year drinkers, 2=Past-year, but not past-month drinkers, 3=Past-month drinkers) was created and used for main analysis. To control for Y1 alcohol use, past-year alcohol use frequency at Y1 was entered as a covariate in the same analysis; Y1 life-time frequency was not chosen as a covariate due to its overlap with Y2 composite variable, and Y1 past-month frequency due to its low variability in this sample.

Cannabis use.

Three items (Johnston et al., 1997) assessed lifetime, past year, and past month cannabis use frequencies at Y1 and Y2. Response options ranged from 0 (Never or 0 occasions) to 6 (40 or more occasions). Parallel to alcohol use variables, an ordinal composite Y2 cannabis variable (0=Lifetime cannabis abstainers, 1=Lifetime, but not past-year cannabis users, 2=Past-year, but not past-month cannabis users, 3=Past-month cannabis users), was used for main analysis, controlling for Y1 past-year cannabis use frequency.

Discrimination Experiences.

The 9-item Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams et al., 1997) assessed frequency of discrimination experiences (e.g., being treated with less respect, being called names or insulted, or being threatened or harassed). Response options ranged from 0 (Never) to 5 (Always). A continuous sum score (grand mean centered) was used for primary analyses. Additional items assessed attribution of discrimination to race or sexual orientation (0=No, 1=Yes) as well as other potential sources (e.g., appearance, religious affiliation, peer group).

Data Analytic Strategies

All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 26 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, 2018). Means and standard deviations (or percentages) and bivariate correlations of all study variables were calculated. After transforming, all alcohol and cannabis ordinal composite variables (skewness values=0.72 to 1.03; kurtosis=−1.10 to −0.73) and discrimination exposure (skewness=0.77, kurtosis=0.84) were normally distributed. Descriptive analyses explored whether discrimination experiences differed by LGB status (t-test) or racial group (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis). Pearson chi square tests were used to assess differences in endorsement of specific relevant sources of discrimination (i.e., race/ethnicity or sexual orientation) by racial group and LGB status. For t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and chi-square analyses, Cohen’s d, partial η2, and Cramer’s V were respectively presented as effect sizes.

As primary analyses, two multinomial logistic regressions separately regressed Y2 alcohol and cannabis consumption onto main effects of Y1 race, LGB status, and discrimination, as well as interaction effects of discrimination with each racial group and LGB status. Multinomial logistic regressions produce separate results for each category of the outcome variable (i.e., lifetime, past-year, and past-month use). Multinomial logistic regressions were selected to accommodate assumptions of proportional odds, and odds ratios (ORs) are presented as effect sizes. Both models were adjusted for age, socioeconomic status, Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity, and Y1 past-year alcohol or cannabis use frequency. Ancillary analyses were conducted with discrimination attribution (i.e., discrimination based on race or sexual orientation) in place of discrimination frequency across models, thus accounting for interaction effects of a) race with race-based discrimination and b) LGB status with sexual orientation-based discrimination.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Descriptive statistics for the overall sample and for each group of interest (i.e., LGB, White, Black, Asian, Multiracial) are reported in Table 1. Race groups differed in terms of frequency of the overall discrimination experiences (F[3,346]=3.40, p=.02, partial η2=.03; Multiracial > White students, p=.01) and endorsement of race-based discrimination specifically (46% Multiracial, 39% Asian, 38% Black, and 19% White students; χ2[3]=12.77, p=.01, Cramer’s V=.19; White < all other racial groups, p<.001). Sexual orientation groups likewise differed in terms of frequency of overall discrimination experiences (t[348]=2.16, p=.03, Cohen’s d=.35) and endorsement of sexual orientation-based discrimination specifically (36% LGB and 7% straight students; χ2[1]=34.10, p<.001, ϕ=.31). Bivariate correlations between all study variables are reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Group Comparisons for the Total Sample and by Sexual Orientation and Racial Group

| Variable (range) | Total Sample (n=354) |

Sexual Orientation | Race | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGB (n=52) |

Non-LGB (n=298) |

White (n=78) |

Black (n=152) |

Asian (n=64) |

Multiracial (n=56) |

||

| M (SD) or % | |||||||

| Age | 15.95 (1.07) | 15.81 (1.05) | 15.98 (1.07) | 15.71 (0.91) | 16.05 (1.03) | 16.10 (1.27) | 15.86 (1.09) |

| Male Sex | 44% | 26%a | 47%b | 49% | 45% | 44% | 34% |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 10% | 11% | 10% | 4%a | 7%a | 2%a | 38%b |

| Free/reduced lunch eligibility | 87% | 79% | 89% | 73%a | 93%b | 88%a,b | 89%a,b |

| Y1 Discrimination (0-36) | 9.07 (6.90) | 10.29 (6.76) | 8.86 (6.92) | 7.88a (5.83) | 8.95a,b (7.26) | 8.59a,b (6.68) | 11.57b (7.08) |

| Y1 Past-year alcohol use (0-3) | 0.50 (0.99) | 0.71 (1.07) | 0.46 (0.98) | 0.87a (1.26) | 0.37b (0.90) | 0.38b (0.80) | 0.48a,b (0.91) |

| Y1 Past-year cannabis use (0-3) | 0.54 (1.36) | 0.88 (1.69) | 0.48 (1.29) | 1.00a (1.82) | 0.48b (1.24) | 0.13b (0.77) | 0.55a,b (1.31) |

| Y2 alcohol use composite (0-3) | 0.94 (1.17) | 1.38 (1.24)a | 0.87 (1.14)b | 1.42a (1.29) | 0.70b (1.08) | 0.73b (0.99) | 1.16b (1.19) |

| Y2 cannabis use composite (0-3) | 0.79 (1.21) | 1.25 (1.33)a | 0.71 (1.17)b | 1.08a (1.35) | 0.74a,b (1.21) | 0.41b (0.85) | 0.96a,b (1.22) |

Note. First column details available data for each study variable. Pearson chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables (e.g., sex, Hispanic ethnicity, Y2 alcohol and cannabis use ordinal composite) and one-way ANOVA tests were used to compare continuous variables (e.g., age, discrimination, Y1 alcohol and cannabis use frequency) by group. Y1=Year 1; Y2=Year 2. Groups that share a subscript are not significantly different from one another at p < .05.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations of All Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | - | ||||||||||||

| 2. Male Sex (vs. female) | .14** | - | |||||||||||

| 3. LGB (vs. non-LGB) | −.06 | −.16** | - | ||||||||||

| 4. White (vs. non-White) | −.12* | .05 | .12* | - | |||||||||

| 5. Black (vs. non-Black) | .08 | .02 | −.06 | −.47** | - | ||||||||

| 6. Asian (vs. non-Asian) | .07 | .00 | −.05 | −.25** | −.42** | - | |||||||

| 7. Multiracial (vs. Monoracial) | −.04 | −.09 | −.01 | −.23** | −.38** | −.21** | - | ||||||

| 8. Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity | .07 | −.04 | .02 | −.11** | −.10 | −.13* | .40** | - | |||||

| 9. Free/reduced lunch eligibility | .07 | −.05 | −.10 | −.22** | .15** | .01 | .03 | .04 | - | ||||

| 10. Y1 Discrimination | .02 | −.02 | .07 | −.09 | −.02 | −.03 | .16** | .03 | .11* | - | |||

| 11. Y1 Alcohol use frequency | .16* | .04 | .09 | .20** | −.11* | −.06 | −.01 | −.02 | −.18** | .07 | - | ||

| 12. Y1 Cannabis use frequency | .11* | .02 | .11* | .18** | −.05 | −.15* | .00 | .01 | −.17** | .11* | .63** | - | |

| 13. Y2 Alcohol use frequency | .13* | .04 | .16** | .22** | −.16** | −.08 | .08 | .02 | −.11* | .11* | .51** | .38** | - |

| 14. Y2 Cannabis use frequency | .11* | .09 | .16** | .13* | −.04 | −.15** | .06 | .02 | −.07 | .28** | .41** | .56** | .48** |

Note. N=350. Pearson’s r correlation statistics are reported for two continuous variables (i.e., age, discrimination experiences, and all alcohol and cannabis variables). Phi coefficients (ϕ) are presented for pairs of dichotomous variables (i.e., sex, LGB status, all racial groups, Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity, and free/reduced lunch eligibility). Spearman’s rs correlation statistics are reported for continuous and dichotomous variables. Y1=Year 1; Y2=Year 2.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Main Analyses

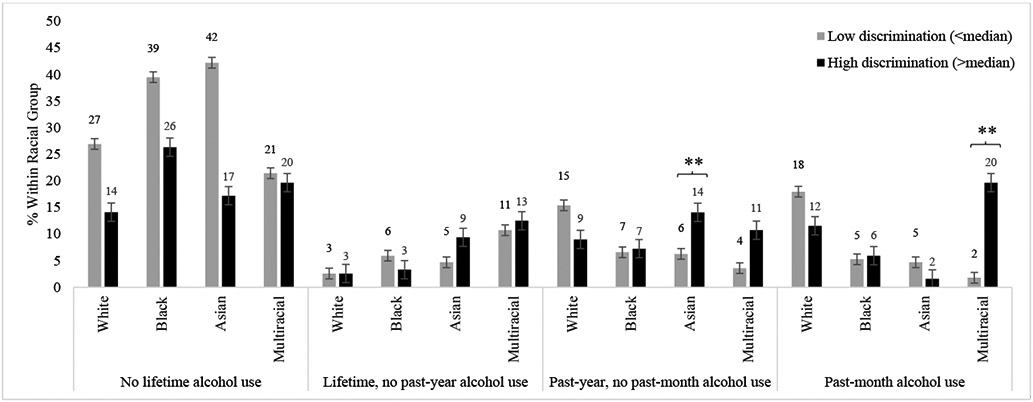

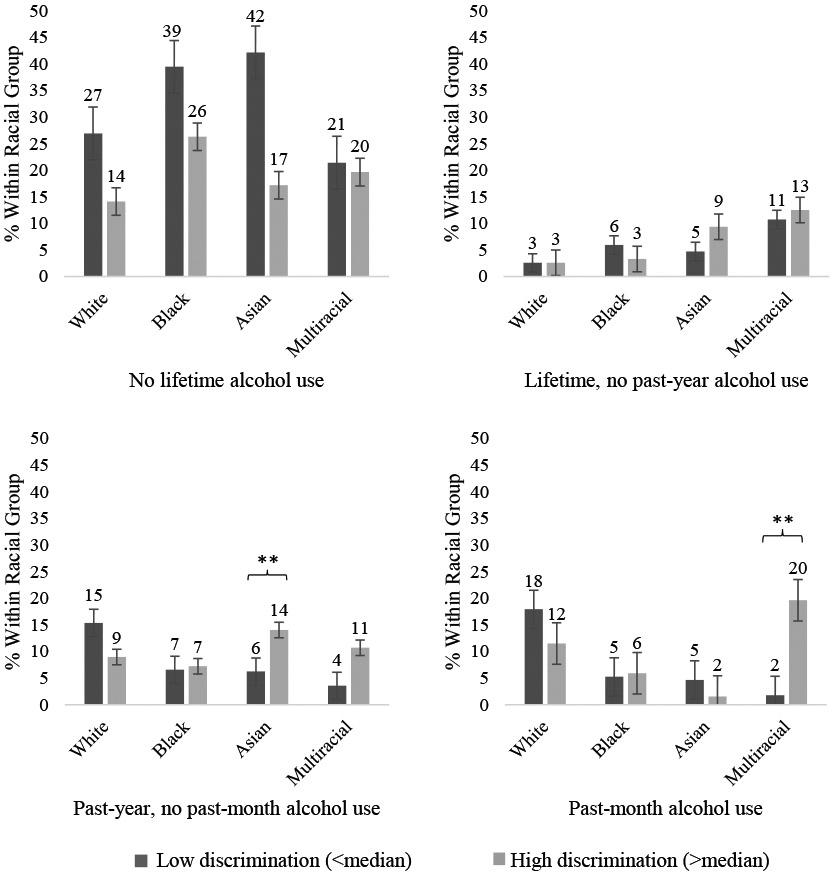

Results from the multinomial logistic regression predicting Y2 alcohol use are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1. Lifetime alcohol use (i.e., no past-year drinking) was not predicted by race, LGB status, Y1 discrimination, or any interactions. Past-year alcohol use (i.e., no drinking within the past month) was predicted by the interaction of discrimination with Asian (but not Black or Multiracial) race, such that Asian students experiencing more frequent discrimination were more likely to engage in past-year drinking; no significant interactions were found between discrimination and LGB status. Likelihood of past-year drinking did not differ by race or LGB status. Past-month alcohol use was predicted by the interaction of discrimination and Multiracial (but not Black or Asian) race, such that Multiracial students experiencing more frequent discrimination were more likely to engage in past-month drinking; no significant interactions were found between discrimination and LGB status. After accounting for discrimination frequency, Black and Asian (versus White) students were less likely and LGB (versus straight) students were more likely to engage in past-month drinking. Ancillary analyses using discrimination attribution (race, sexual orientation) in place of discrimination frequency found no significant interactions of attribution with race or sexual orientation, but similar main effects of racial group on each alcohol outcome as those observed with discrimination frequency.

Table 3.

Results of a Multinomial Logistic Regression for Year 2 Alcohol Use Patterns

| Year 1 Variable | Year 2 Alcohol Use Patterns (vs. No Lifetime Use) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Y2 Lifetime use (no past-year or past-month use) OR (95% CI) |

Y2 Past-year use (no past-month use) OR (95% CI) |

Y2 Past-month use OR (95% CI) |

|

| LGB status | 1.94 (0.55, 6.87) | 1.97 (0.69, 5.67) | 3.48 (1.20, 10.09)* |

| Black (vs. White) race | 1.19 (0.33, 4.34) | 0.51 (0.20, 1.27) | 0.34 (0.13, 0.89)* |

| Asian (vs. White) race | 2.37 (0.58, 9.70) | 0.86 (0.29, 2.58) | 0.18 (0.03, 0.94)* |

| Multiracial (vs. White) race | 3.58 (0.85, 15.02) | 0.77 (0.23, 2.56) | 0.76 (0.20, 2.91) |

| Y1 Discrimination experiences | 1.05 (0.89, 1.24) | 0.92 (0.81, 1.04) | 0.92 (0.81, 1.04) |

| Discrimination x LGB | 1.05 (0.87, 1.27) | 0.98 (0.81, 1.18) | 0.94 (0.79, 1.12) |

| Discrimination x Black | 0.93 (0.78, 1.12) | 1.11 (0.96, 1.28) | 1.09 (0.94, 1.26) |

| Discrimination x Asian | 1.08 (0.87, 1.36) | 1.34 (1.11, 1.63)** | 1.07 (0.81, 1.41) |

| Discrimination x Multiracial | 1.00 (0.82, 1.23) | 1.05 (0.86, 1.27) | 1.30 (1.07, 1.58)** |

| Age | 1.22 (0.86, 1.74) | 1.00 (0.71, 1.42) | 1.52 (1.03, 2.27)* |

| Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity | 1.98 (0.66, 5.92) | 1.72 (0.53, 5.58) | 0.55 (0.13, 2.27) |

| Free/reduced-price lunch eligibility | 1.94 (0.41, 9.30) | 1.04 (0.34, 3.19) | 0.81 (0.27, 2.45) |

| Male Sex | 1.20 (0.56, 2.56) | 0.97 (0.48, 1.95) | 1.47 (0.69, 3.17) |

| Y1 Past-year alcohol use frequency | 3.48 (1.73, 6.98)*** | 7.45 (4.09, 13.58)*** | 7.52 (4.09, 13.84)*** |

Note. N=350. OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval. Y1=Year 1; Y2=Year 2.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1. Observed Percentages (and Standard Error Bars) of Participants in Each Racial Group by Year 2 Alcohol Use Pattern and Year 1 Frequency of Discrimination Experiences.

Note. N=350. Significant interactions as found in the multinomial logistic regression are denoted by asterisks (** p < .01) where “No lifetime alcohol use” was used for comparison. White race was used as a reference group.

Results from the multinomial logistic regression predicting Y2 cannabis use are presented in Table 4. Neither discrimination experiences nor any interaction of race or LGB status with discrimination experiences predicted any cannabis use pattern relative to abstinence. Likelihood of any cannabis use pattern did not differ by race, but LGB (versus straight) participants were more likely to engage in past-month cannabis use. Ancillary analyses using discrimination type (race, sexual orientation) in place of discrimination frequency produced considerable standard errors due to small cell size of certain interaction terms (e.g., Asian past-month cannabis users who attributed discrimination to race n = 2), and thus could not be interpreted.

Table 4.

Results of a Multinomial Logistic Regression Model for Year 2 Cannabis Use Patterns

| Year 1 Variable | Year 2 Cannabis Use Patterns (vs. No Lifetime Use) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Y2 Lifetime use (no past-year or past-month use) OR (95% CI) |

Y2 Past-year use (no past-month use) OR (95% CI) |

Y2 Past-month use OR (95% CI) |

|

| LGB status | 3.70 (0.73, 18.74) | 2.19 (0.69, 6.95) | 4.07 (1.58, 11.23)** |

| Black (vs. White) race | 0.62 (0.11, 3.62) | 0.72 (0.24, 2.18) | 0.66 (0.25, 1.74) |

| Asian (vs. White) race | 1.79 (0.28, 11.49) | 0.85 (0.20, 3.68) | 0.32 (0.06, 1.66) |

| Multiracial (vs. White) race | 2.53 (0.31, 20.87) | 1.42 (0.34, 5.90) | 1.22 (0.32, 4.65) |

| Y1 Discrimination experiences | 0.96 (0.76, 1.20) | 1.05 (0.90, 1.24) | 1.15 (0.99, 1.33) |

| Discrimination x LGB | 1.05 (0.84, 1.31) | 1.00 (0.83, 1.19) | 0.89 (0.76, 1.06) |

| Discrimination x Black | 1.10 (0.84, 1.44) | 1.03 (0.86, 1.24) | 0.99 (0.84, 1.17) |

| Discrimination x Asian | 1.15 (0.88, 1.50) | 1.15 (0.93, 1.43) | 1.02 (0.80, 1.28) |

| Discrimination x Multiracial | 1.22 (0.90, 1.67) | 1.08 (0.87, 1.34) | 0.96 (0.78, 1.18) |

| Age | 1.87 (1.08, 3.24)* | 0.90 (0.59, 1.37) | 1.15 (0.78, 1.68) |

| Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity | -- | 1.26 (0.33, 4.83) | 0.82 (0.20, 3.30) |

| Free/reduced-price lunch eligibility | 0.91 (0.15, 5.43) | 0.73 (0.22, 2.44) | 1.01 (0.30, 3.38) |

| Male sex | 2.32 (0.69, 7.84) | 1.24 (0.53, 2.88) | 2.88 (1.30, 6.35)** |

| Y1 Past-year cannabis use frequency | 4.45 (2.04, 9.72)*** | 5.24 (2.62, 10.47)*** | 6.72 (3.38, 13.36)*** |

Note. N=350. OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval. No Hispanic participants reported lifetime (but no past-year) cannabis use, and thus, neither OR nor CIs were calculated. Y1=Year 1; Y2=Year 2.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Despite mounting evidence that discrimination is associated with greater alcohol use among POC and LGB adolescents, parallel associations between discrimination, marginalization status, and cannabis use remain under-researched. This study expanded the adolescent discrimination-substance literature by (a) utilizing a racially-diverse adolescent sample, (b) exploring discrimination as it relates to POC and LGB adolescents separately and simultaneously, and (c) examining associations with cannabis in addition to alcohol use. Findings suggest that discrimination experiences may elevate risk for alcohol (but not cannabis) use among adolescents of understudied (Asian, Multiracial) racial backgrounds, but not Black or LGB adolescents, over one year.

Alcohol Findings

Consistent with hypotheses, Asian adolescents experiencing more frequent discrimination had greater odds of past-year (but not lifetime or past-month) alcohol use. Adolescent findings expand emerging evidence for positive discrimination-alcohol associations among Asian-American young adults (Le & Iwamoto, 2019). Also consistent with hypotheses, Multiracial adolescents experiencing more frequent discrimination endorsed greater odds of past-month (but not lifetime or past-year) drinking. This finding adds to limited research, including the null cross-sectional association of discrimination frequency with past-year drinking observed among Multiracial adolescents in this sample (controlling for negative affect and insomnia symptoms; Goodhines, Desalu, et al., 2020). Associations of greater discrimination with higher odds of past-month drinking among Multiracial adolescents but higher odds of past-year drinking among Asian adolescents may be reflective of Multiracial adolescents’ overall more frequent alcohol use than Asian adolescents (Goings et al., 2018; Lipari, 2019); indeed, in this sample, 21% Multiracial adolescents but only 6% Asian adolescents reported past-month drinking. Taken together, results suggest that discrimination may be an indicator for youth drinking among these understudied racial groups.

Inconsistent with hypotheses and previous literature (e.g., Brody et al., 2012), Black adolescents’ alcohol use did not differ by frequency of discrimination. One possible explanation is the fact that Black adolescents (44%) make up the majority of the current sample drawn from a racially-diverse urban high school; the social support (Gilbert et al., 2014; Walsh et al., 2018) and racial identification (Stock et al., 2013) potentially afforded by Black peers may have mitigated the alcohol-related risk conferred by discrimination. Alternatively, discrimination-related drinking may manifest at a later age among Black adolescents given relatively later initiation and lower frequency (e.g., versus White peers; Johnson et al., 2019). Future research is needed to assess replicability of current findings, including explication of potential underlying psychosocial mechanisms and differential developmental trends.

Inconsistent with hypotheses, theory (Meyer, 2003), and previous literature (e.g., Mereish et al., 2017), alcohol use did not differ by discrimination frequency among LGB adolescents. Null findings may reflect that, in this sample, LGB adolescents did not report greater discrimination than straight peers (see Table 2). Alternatively, results may reflect the generalized nature of the discrimination scale used in this study, as compared to scales specific to homophobic victimization (Mereish et al., 2017). Future research is needed to explore potential variability in drinking frequency associated with LGB-specific (versus generalized) discrimination.

Cannabis Findings

Inconsistent with hypotheses, neither POC nor LGB adolescents reported higher odds of any pattern of cannabis use when experiencing frequent discrimination. Unexpected findings may be explained by differential motivations for cannabis (versus alcohol) use among these groups, such that alcohol may be used for coping (e.g., van der Zwaluw et al., 2011) whereas cannabis is more prevalently used for other motives (e.g., experiential enhancement; Caouette & Feldstein Ewing, 2017). Null findings may also be representative of relative difficulty in accessing cannabis (versus alcohol; Miech et al., 2020), especially for this socioeconomically disadvantaged sample. Future replications may investigate diverse motives underlying POC and LGB adolescents’ cannabis use, as well as socioeconomic generalizability.

However, LGB (versus straight) status was directly associated with higher odds of past-month (but not lifetime or past-year) cannabis use, independent of discrimination exposure. The absence of higher odds for lifetime or past-year cannabis use, and the high percentage of LGB adolescents who endorse past-month cannabis use (28%) compared to past-year (but not past-month) cannabis use (15%), may suggest an accelerated progression from initiation to frequent cannabis use for LGB adolescents. Indeed, LGB adolescents have been shown to initiate cannabis use earlier and escalate more rapidly compared to straight peers (Marshal et al., 2009). Future research is needed to explore potential cannabis-related risk mechanisms unique to LGB adolescents, such as cannabis’s utility for exploration and/or rejection of gender norms (Dahl & Sandberg, 2015) or as a tool for social connection (Robinson et al., 2016).

Clinical Implications

Findings may inform individual and systemic substance-related prevention and intervention. First, findings suggest that discrimination exposure should be monitored as an early indicator for later high-frequency drinking. Prevention efforts among marginalized groups may promote discrimination resilience strategies by bolstering existing protective strategies such as family-based attachment (Fang & Schinke, 2013), social support (Gilbert et al., 2014; Walsh et al., 2018) and racial identification (Stock et al., 2013). Further, evidence-based coping-oriented interventions for adolescent alcohol use may be adapted to address the specific needs of marginalized groups (e.g., Asian or Multiracial adolescents), while simultaneously remaining sensitive to within-group heterogeneity (Feldstein Ewing et al., 2012). Systemic interventions to reduce discrimination should be prioritized to limit development of downstream health consequences (i.e., substance use), prioritizing diversity in academic hiring practices and implementing culturally-competent classroom management training for teachers (Trent et al., 2019).

Limitations and Future Directions

Findings should be interpreted with consideration of limitations. First, results are correlational in nature, rendering implications regarding causality speculative. Additionally, as multilevel analyses could not be conducted due to the limited number of time points in the dataset, results do not account for within-person variation beyond controlling for Y1 substance use. Second, results may not generalize to samples with different demographic or socioeconomic makeup. Race-specific results may not generalize accurately to all group members due to known heterogeneity within racial groups (e.g., Gibbs et al., 2013; Kane et al., 2017). Further, race and ethnicity (Hispanic/Latinx) were assessed separately in this study (i.e., “two item approach”; Patten, 2015), precluding explication of individuals who identify as Latinx race (possibly especially relevant among Multiracial youth; Charmaraman et al., 2014). Third, LGB individuals were condensed into a single group due to low prevalence, precluding assessment of identity-specific effects and necessitating ongoing research into nuanced LGB identity(s) to capture potential variations by sexual orientation (e.g., consideration of bisexual women as a risk group relative to monosexual orientations; see Demant et al., 2016; Schuler & Collins, 2020). Fourth, exploration of intersecting/compounding risk conferred by belonging to both POC and LGB groups was precluded by low overlap in this sample, necessitating ongoing research into the frequency and forms of discrimination potentially novel to multiple marginalization. Fifth, whereas this study examined whether alcohol/cannabis use frequency among POC and LGB adolescents differed by frequency of discrimination, an important next step is to assess discrimination as a potential mediator of group membership and substance use associations (consistent with minority stress frameworks; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003).

Conclusions

Prospective findings suggest that Asian and Multiracial adolescents are at particular risk for high-frequency drinking when exposed to frequent discrimination. Null findings regarding discrimination-cannabis associations suggest alternative risk factors for adolescent cannabis use should be explored, particularly for LGB adolescents, who independently evidenced frequent cannabis use. Although replication is needed, current findings inform development and/or tailoring of prevention/intervention programming to mitigate adverse health effects of discrimination, as well as systemic intervention to reduce discrimination experiences among youth.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R15AA022496 and R01AA027677 awarded to Aesoon Park. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Amelia V. Wedel, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244

Patricia A. Goodhines, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244

Michelle J. Zaso, Clinical and Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo – The State University of New York, Buffalo, New York, USA

Aesoon Park, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244.

References

- Amos R, Manalastas EJ, White R, Bos H, & Patalay P (2020). Mental health, social adversity, and health-related outcomes in sexual minority adolescents: A contemporary national cohort study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 36–45. 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30339-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Baldwin SA, Zheng C, Gallop RJ, & Neighbors C (2013). A tutorial on count regression and zero-altered count models for longitudinal substance use data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 166–177. 10.1037/a0029508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgett MVL, Goldberg N, Conron KJ, & Gates GJ (2009). Best Practices for Asking Questions about Sexual Orientation on Surveys (SMART). UCLA School of Law, Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/smart-so-survey/ [Google Scholar]

- Bränström R, & Pachankis JE (2018). Sexual orientation disparities in the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress: A national population-based study (2008–2015). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(4), 403–412. 10.1007/s00127-018-1491-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kogan SM, & Chen Y (2012). Perceived Discrimination and Longitudinal Increases in Adolescent Substance Use: Gender Differences and Mediational Pathways. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 1006–1011. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, & Szapocznik J (2015). Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caouette JD, & Feldstein Ewing SW (2017). Four Mechanistic Models of Peer Influence on Adolescent Cannabis Use. Current Addiction Reports, 4(2), 90–99. 10.1007/s40429-017-0144-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (Demographics Module 2013-2014). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaraman L, Woo M, Quach A, & Erkut S (2014). How have researchers studied multiracial populations? A content and methodological review of 20 years of research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(3), 336–352. 10.1037/a0035437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon YM, & Yip T (2019). Longitudinal Associations between Ethnic/Racial Identity and Discrimination among Asian and Latinx Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(9), 1736–1753. 10.1007/s10964-019-01055-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TT, Nguyen AB, & Kropko J (2013). Epidemiology of Drug Use among Biracial/Ethnic Youth and Young Adults: Results from a U.S. Population-Based Survey. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45(2), 99–111. 10.1080/02791072.2013.785804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl SL, & Sandberg S (2015). Female Cannabis Users and New Masculinities: The Gendering of Cannabis Use. Sociology, 49(4), 696–711. 10.1177/0038038514547896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demant D, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, White KM, Winstock AR, & Ferris J (2016). Differences in substance use between sexual orientations in a multi-country sample: Findings from the Global Drug Survey 2015. Journal of Public Health, jphm;fdw069v2. 10.1093/pubmed/fdw069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody SS, Marshal MP, Cheong J, Burton C, Hughes T, Aranda F, & Friedman MS (2014). Longitudinal Disparities of Hazardous Drinking Between Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Individuals from Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(1), 30–39. 10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desalu JM, Goodhines PA, & Park A (2019). Racial discrimination and alcohol use and negative drinking consequences among Black Americans: A meta-analytical review. Addiction, 114(6), 957–967. 10.1111/add.14578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DT, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Johnson RM (2014). Neighborhood-level LGBT hate crimes and current illicit drug use among sexual minority youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 135, 65–70. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett BG, Schnarrs PW, Rosario M, Garofalo R, & Mustanski B (2014). Sexual Orientation Disparities in Sexually Transmitted Infection Risk Behaviors and Risk Determinants Among Sexually Active Adolescent Males: Results From a School-Based Sample. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1107–1112. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, & Schinke SP (2013). Two-year outcomes of a randomized, family-based substance use prevention trial for Asian American adolescent girls. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(3), 788–798. 10.1037/a0030925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein Ewing SW, Wray AM, Mead HK, & Adams SK (2012). Two approaches to tailoring treatment for cultural minority adolescents. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 43(2), 190–203. 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell TE, Curtis DS, Chae DH, & Ryff CD (2018). Longitudinal health consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage: Examining perceived discrimination as a mediator. Health Psychology, 37(5), 491–500. 10.1037/hea0000616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs TA, Okuda M, Oquendo MA, Lawson WB, Wang S, Thomas YF, & Blanco C (2013). Mental Health of African Americans and Caribbean Blacks in the United States: Results From the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. American Journal of Public Health, 103(2), 330–338. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PA, Perreira K, Eng E, & Rhodes SD (2014). Social Stressors and Alcohol Use Among Immigrant Sexual and Gender Minority Latinos in a Nontraditional Settlement State. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(11), 1365–1375. 10.3109/10826084.2014.901389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PA, & Zemore SE (2016). Discrimination and drinking: A systematic review of the evidence. Social Science & Medicine, 161, 178–194. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goings TC, Salas-Wright CP, Howard MO, & Vaughn MG (2018). Substance use among bi/multiracial youth in the United States: Profiles of psychosocial risk and protection. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(2), 206–214. 10.1080/00952990.2017.1359617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodhines PA, Desalu JM, Zaso MJ, Gellis LA, & Park A (2020). Sleep Problems and Drinking Frequency among Urban Multiracial and Monoracial Adolescents: Role of Discrimination Experiences and Negative Mood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(10), 2109–2123. 10.1007/s10964-020-01310-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodhines PA, Taylor LE, Zaso MJ, Antshel KM, & Park A (2020). Prescription Stimulant Misuse and Risk Correlates among Racially-Diverse Urban Adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse, 55(14), 2258–2267. 10.1080/10826084.2020.1800740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Doherty EE, & Ensminger ME (2017). Long-term consequences of adolescent cannabis use: Examining intermediary processes. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(5), 567–575. 10.1080/00952990.2016.1258706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Chen CM, & Grant BF (2016). Other- and Self-Directed Forms of Violence and Their Relationship With Number of Substance Use Disorder Criteria Among Youth Ages 12–17: Results From the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77(2), 277–286. 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. 10.1037/a0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittner EF, & Adam EK (2020). Emotional Pathways to the Biological Embodiment of Racial Discrimination Experiences. Psychosomatic Medicine, 82(4), 420–431. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JS, Kim J, Lee JJ, Shamoun CL, Lee JM, & Voisin DR (2019). Pathways From Peer Victimization to Sexually Transmitted Infections Among African American Adolescents. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 41(6), 798–815. 10.1177/0193945918797327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Thoma BC, & Neilands TB (2015). School Victimization and Substance Use Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adolescents. Prevention Science, 16(5), 734–743. 10.1007/s11121-014-0507-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (26.0). (2018). [Windows]. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RM, Fleming CB, Cambron C, Dean LT, Brighthaupt S-C, & Guttmannova K (2019). Race/Ethnicity Differences in Trends of Marijuana, Cigarette, and Alcohol Use Among 8th, 10th, and 12th Graders in Washington State, 2004–2016. Prevention Science, 20(2), 194–204. 10.1007/s11121-018-0899-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, & O’Malley PM (1997). Monitoring the Future: A Continuing Study of American Youth (12th-Grade Survey), 1995: Version 2 [Data set]. ICPSR - Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. 10.3886/ICPSR06716.V2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JC, Damian AJ, Fairman B, Bass JK, Iwamoto DK, & Johnson RM (2017). Differences in alcohol use patterns between adolescent Asian American ethnic groups: Representative estimates from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2002–2013. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 154–158. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, & Ethier KA (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017. 67(8), 479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, Dziak JJ, & Butera NM (2015). Trends Among U.S. High School Seniors in Recent Marijuana Use and Associations With Other Substances: 1976–2013. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(2), 198–204. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le TP, & Iwamoto DK (2019). A longitudinal investigation of racial discrimination, drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems among underage Asian American college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(6), 520–528. 10.1037/adb0000501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN (2019). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, & Thompson AL (2009). Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 104(6), 974–981. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02531.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereish EH, Goldbach JT, Burgess C, & DiBello AM (2017). Sexual orientation, minority stress, social norms, and substance use among racially diverse adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 178, 49–56. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, & Frost DM (2008). Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 368–379. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, & Bachman JG (2020). Trends in Reported Marijuana Vaping Among US Adolescents, 2017-2019. JAMA, 323(5), 475. 10.1001/jama.2019.20185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Tam TW, Bond J, Zemore SE, & Li L (2018). Racial/ethnic differences in life-course heavy drinking from adolescence to midlife. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 17(2), 167–186. 10.1080/15332640.2016.1275911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, & Zemore SE (2009). Disparities in Alcohol-Related Problems Among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(4), 654–662. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson LM, Slater SJ, Chriqui JF, & Chaloupka F (2014). Validating Adolescent Socioeconomic Status: Comparing School Free or Reduced Price Lunch with Community Measures. Spatial Demography, 2(1), 55–65. 10.1007/BF03354904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, Caldwell CH, Jackson JS, & Bernstein BA (2018). Discrimination and Mental Health in a Representative Sample of African-American and Afro-Caribbean Youth. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(4), 831–837. 10.1007/s40615-017-0428-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531–554. 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten. (2015). Who is Multiracial? Depends on How You Ask: A Comparison of Six Survey Methods to Capture Racial Identity. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/2015-11-06_race-question-methods_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M, Sanches M, & MacLeod MA (2016). Prevalence and Mental Health Correlates of Illegal Cannabis Use Among Bisexual Women. Journal of Bisexuality, 16(2), 181–202. 10.1080/15299716.2016.1147402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, & Collins RL (2020). Sexual minority substance use disparities: Bisexual women at elevated risk relative to other sexual minority groups. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 206, 107755. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock ML, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Houlihan AE, Weng C-Y, Lorenz FO, & Simons RL (2013). Racial identification, racial composition, and substance use vulnerability among African American adolescents and young adults. Health Psychology, 32(3), 237–247. 10.1037/a0030149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, Turner B, Foster AM, & Phillips G (2019). Sexual Minority Youth at Risk of Early and Persistent Alcohol, Tobacco, and Marijuana Use. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(4), 1073–1086. 10.1007/s10508-018-1275-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Trevor Project. (2019). National Survey on LGBTQ Mental Health. The Trevor Project. [Google Scholar]

- Trent M, Dooley DG, Dougé J, SECTION ON ADOLESCENT HEALTH, COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS, & COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE. (2019). The Impact of Racism on Child and Adolescent Health. Pediatrics, 144(2), e20191765. 10.1542/peds.2019-1765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau. (2017). Projected population by single year of age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States: 2016 to 2016 [Data set]. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popproj/datasets/2017/2017-popproj/np2017-d1.csv [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwaluw CS, Kuntsche E, & Engels RCME (2011). Risky alcohol use in adolescence: The role of genetics (DRD2, SLC6A4) and coping motives. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 35(4), 756–764. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SD, Kolobov T, & Harel-Fisch Y (2018). Social Capital as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Perceived Discrimination and Alcohol and Cannabis Use Among Immigrant and Non-immigrant Adolescents in Israel. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1556. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-T, Blazer DG, Swartz MS, Burchett B, & Brady KT (2013). Illicit and nonmedical drug use among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, and mixed-race individuals. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 133(2), 360–367. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-T, Brady KT, Mannelli P, & Killeen TK (2014). Cannabis use disorders are comparatively prevalent among nonwhite racial/ethnic groups and adolescents: A national study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 50, 26–35. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]