Abstract

Removal of dibenzofuran, dibenzo-p-dioxin, and 2-chlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (2-CDD) (10 ppm each) from soil microcosms to final concentrations in the parts-per-billion range was affected by the addition of Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Rates and extents of removal were influenced by the density of RW1 organisms. For 2-CDD, the rate of removal was dependent on the content of soil organic matter (SOM), with half-life values ranging from 5.8 h (0% SOM) to 26.3 h (5.5% SOM).

Diaryl ether compounds include several chemicals (e.g., 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin) that are recognized as toxic pollutants and that persist in soils, in part, by sorbing onto organic matter (7, 20) and, to a lesser extent, onto mineral surfaces (12). Aerobic bacteria that degrade dibenzo-p-dioxin (DD), dibenzofuran (DF), carboxydiphenyl ether, and some halogenated derivatives of these chemicals have been isolated (9, 11, 16, 17, 26, 32, 33). Researchers have primarily focused their studies on the activities of these bacteria in liquid culture (10, 18, 19). In one case, degradation of DD and DF in soil microcosms to which Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 was introduced was observed (25). To determine whether these and similar bacteria have potential for use in in situ bioremediation, data concerning the fate and activity of the bacteria in soils are needed in conjunction with data on the bioavailability of target chemicals (14). These factors were addressed in this study by using soil microcosms and Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1, a bacterium that mineralizes DD and DF as growth substrates and transforms certain mono- and dichlorinated analogs of these chemicals as cometabolic reactions (32).

Bacterial growth conditions.

Strain RW1 (no. 6014; German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany) was tagged with a Tn5 suicide donor system, pNMBH20, that encodes genes for resistance to kanamycin and for catechol-2,3-dioxygenase (24). This enzyme converts catechol to muconic acid semialdehyde, a product having a bright yellow color, and does so at a higher rate than the catechol-2,3-dioxygenase present in strain RW1. Strain RW1 was routinely grown in the dark (200 rpm, 30°C) by using M9 minimal medium (23) supplemented with trace elements (31) and DF (1 g/liter) as the sole substrate. Solid medium contained agar (15 g/liter) with benzoate (5 mM) as the sole substrate plus kanamycin (50 μg/ml).

Soils.

A pale brown, sandy Zimmerman soil (B21 horizon, 18 to 38 cm below surface) was obtained from a previously cultivated field in the Cedar Creek Natural History Area, Minn. A dark soil (A horizon) was obtained from Fort Snelling State Park, St. Paul, Minn. Soils were sieved (2-mm mesh) and stored at 4°C. A quartz sand (Jordan) was obtained from the Minnesota Frac Sand Co., Jordan, Minn. (Table 1). The sand was sieved to obtain a fraction with a particle size distribution of 0.15 to 0.6 mm. Cedar Creek soil was blended with Jordan sand and Fort Snelling soil to obtain various contents of organic matter, ranging from 0 to 5.5% total organic carbon (TOC). Mixtures were air dried, and water was added to a level equal to 60% field capacity.

TABLE 1.

Components of soils and sand

| Component | Wt (%) of component

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cedar Creek soil | Fort Snelling soil | Jordan sand | |

| Sand | 95 | 60 | >99.6 |

| Clay | 3 | 18 | 0 |

| Silt | 2 | 22 | 0 |

| SOM | 0.5 | 5.4 | <0.01 |

| TOC | 0.26 | 3.4 | <0.01 |

Soil microcosm studies.

Microcosms consisted of either serum bottles (100 ml) plus soil (20 g [dry weight] of soil) or vials (4 ml) plus soil (2 g [dry weight] of soil). DD, 2-chlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (2-CDD) (99% purity; Chemservice, West Chester, Pa.), and DF (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) were added to individual microcosms from methanolic stocks 24 h prior to inoculation with strain RW1; strain RW1 does not use methanol as substrate. Bacteria were grown to late log phase, collected by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 20 min), washed twice in saline (0.85% NaCl), and added to the microcosms during mixing. The microcosms were covered with Parafilm and incubated (21°C) in the dark. Densities of strain RW1 and concentrations of DD, DF, and 2-CDD were determined periodically by sacrificing individual microcosms. Data are reported as averages of triplicate determinations.

Bacteria were extracted from soil in an extraction solution (1 ml/g [dry weight] of soil [21]) by agitation on a wrist action shaker (30 min). Extracts were serially diluted in saline; aliquots were then spread on solid medium and incubated (30°C, 7 days). Resultant colonies were sprayed with a solution of catechol (100 mM) to identify strain RW1. The detection limit was 104 CFU/g (dry weight) of soil; the efficiency of recovery was 87%.

DD, DF, and 2-CDD were extracted from soil by addition of acetonitrile (2% H3PO4, 1 ml/g [dry weight] of soil) and agitation (60 min). Particles were settled out (10 min), and the supernatant was passed through a PTFE membrane filter (0.2 μm). Aliquots were analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography with a Waters LC Module I equipped with a reversed-phase Waters Nova-Pak phenyl column (3.9 by 150 mm; particle size, 4 μm) and a Waters 996 photodiode array detector (λ191–320 nm). An isocratic solvent of acidified, distilled water (0.1% H3PO4) and acetonitrile (50:50) was used. Injection was by automatic sampler; volumes ranged from 10 to 200 μl. Peaks and concentrations were identified by comparison to known standards. Recoveries of DF, DD, and 2-CDD ranged from 89 to 100%; detection limits were 50 ppb. As appropriate, concentrations of chemicals were fit to either a pseudo-first-order rate model, dP/dt = −kρP, or a second-order rate model, dP/dt = −k2BP, where P is the concentration of substrate, B is the concentration of biomass, t is time, kρ is the pseudo-first-order rate constant, and k2 is the second-order rate constant.

Survival of RW1.

Densities of strain RW1 (4 × 108 CFU/g [dry weight] of soil) decreased exponentially in soils without substrate amendment at a rate (0.156 ± 0.007 day−1) corresponding to a half-life of 4.4 days. In the presence of DF (10 ppm), the decrease in density was less rapid, at a rate (0.093 ± 0.034 day−1) corresponding to a half-life of 7.5 days. The same rate was observed for several initial densities of the bacterium (4 × 105, 4 × 106, and 4 × 107 CFU/g [dry weight] of soil). In contrast, the presence of DD (10 ppm) did not affect the survival of strain RW1; the density of the bacterium decreased at a rate of 0.148 ± 0.004 day−1, which is similar to that observed in soils without substrate amendment. Densities of strain RW1 decreased dramatically in soils containing 2-CDD (10 ppm), at a rate (0.782 ± 0.045 day−1) corresponding to a half-life of 0.9 days (data not shown).

Degradation of diaryl ether compounds.

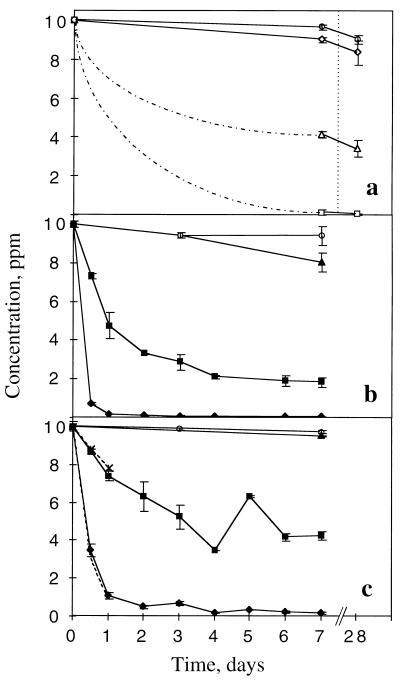

DF was removed from soils containing strain RW1 (Fig. 1a). The extent of removal was dependent on the initial density of the bacteria: a density of 4 × 107 CFU/g (dry weight) of soil resulted in complete removal of DF (<50 ppb) in 7 days. At lower densities, removal of DF was incomplete after 28 days of incubation. DD was also removed by strain RW1 (Fig. 1b); however, relatively higher densities of cells were required. At the highest density tested (109 CFU/g [dry weight] of soil), 90% of DD was degraded within 24 h; after 3 days, the concentration of DD was below the detection limit (50 ppb). In comparison to DD, 2-CDD was somewhat more persistent in soil (Fig. 1c).

FIG. 1.

Removal of DF (a) from soils inoculated with RW1 at densities of 4 × 105 (◊), 4 × 106 (▵), and 4 × 107 (□) CFU/g (dry weight) of soil and of DD (b) and 2-CDD (c) from soils inoculated with RW1 at densities of 107 (▴), 108 (■), and 109 (⧫) CFU/g (dry weight) of soil. Control microcosms (○) received substrates but not RW1.

Removal of 2-CDD by strain RW1 was tested further with soils having varying levels of organic matter; concentrations of 2-CDD were monitored over time (data not shown) and used to calculate rates of degradation (Table 2) with the pseudo-first-order rate model. Rates decreased when comparatively more soil organic matter (SOM) was present; half-life values ranged from 5.8 to 26.3 h. The influence of organic matter became more apparent when rates of degradation for 2-CDD were plotted against SOM (Fig. 2a) and TOC (Fig. 2b). Strong correlations that clearly demonstrated the negative impact of increasing amounts of organic matter on removal rates for 2-CDD were observed.

TABLE 2.

Pseudo-first-order rate coefficients and half-life values for 2-CDD in soils containing RW1 (109 CFU/g [dry weight] of soil) and various amounts of SOM

| SOM (% [dry wt]) | k (day−1)a | Half-life (h) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 2.88 (0.74) | 5.8 |

| 0.5 | 2.22 (0.13) | 7.5 |

| 1.0 | 2.41 (0.41) | 6.9 |

| 2.5 | 2.05 (0.14) | 8.1 |

| 3.0 | 1.37 (0.14) | 12.2 |

| 4.0 | 1.18 (0.13) | 14.1 |

| 5.0 | 1.04 (0.28) | 16.1 |

| 5.5 | 0.63 (0.09) | 26.3 |

Values in parentheses are standard deviations.

FIG. 2.

Correlations between pseudo-first-order rates of degradation of 2-CDD by RW1 with SOM (a) and TOC (b). Error bars indicate standard errors obtained by curve fitting.

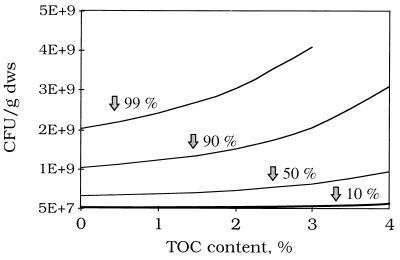

Data in Fig. 2b were used to obtain densities of strain RW1 that would be required to degrade 10, 50, 90, and 99% of 2-CDD in soils containing various concentrations of organic matter (Fig. 3). Removal rates for 2-CDD were estimated with the correlation in Fig. 2b and the estimated rates divided by cell density (109 CFU/g [dry weight] of soil) to obtain specific transformation rates (k2) per cell. The second-order rate model was then used to calculate cell densities for each percentage of TOC. This exercise indicated that as the TOC content of soil increased, relatively more biomass was required to achieve the same extent of removal of 2-CDD. For example, it was necessary to add approximately three times more biomass to soil containing 4% TOC than to soil containing 0% TOC to effect removal of 90% 2-CDD.

FIG. 3.

Calculated densities of RW1 (CFU/g [dry weight] of soil [dws]) that would be required to achieve 2-CDD removal of 10, 50, 90, and 99% within 24 h in soils with TOC ranging from 0 to 4%.

This study demonstrates three points with respect to the potential use of diaryl ether-degrading bacteria for in situ bioremediation. (i) Bacteria with catabolic pathways for diaryl ethers, as represented by strain RW1, can survive and degrade diaryl ether compounds in soil. (ii) Diaryl ethers can exist as bioavailable chemicals in soils, at least under the conditions used in this study. (iii) Soils having similar densities of diaryl ether-degrading microorganisms, but relatively higher levels of TOC, may exhibit relatively lower rates of degradation of these diaryl ether compounds.

It was interesting that the three diaryl ether compounds used in this study exerted different influences on the survival of strain RW1. Although degradation of DF prolonged the persistence of strain RW1, an increase in bacterial density was not observed, possibly due to a lack of essential nutrients. This suggestion was supported by the observation that nutrient supplementation increased the density of a second diaryl ether-degrading bacterium that was added to Cedar Creek soil (15). In contrast, degradation of DD did not prolong the persistence of strain RW1. This may be related to a difference in utilization rates for DF and DD by strain RW1, as was noted in a similar study (25). In pure culture, the turnover rate for DD (280 μmol h−1 g of protein−1) is relatively slower than the turnover rate for DF (562 μmol h−1 g of protein−1) (data from reference 32) and may not be sufficient to prolong survival of the microorganism.

The survival of strain RW1 was adversely affected by the presence of 2-CDD, suggesting that 2-CCD and/or its metabolites were toxic to the bacterium. Dioxins are typically neither toxic nor inhibitory to microorganisms and have no observable effect on soil respiration (5), microbial activity, and diversity (2). However, during transformation of 2-CDD, 4-chlorocatechol is observed as a dead-end product (32). Chlorinated phenolics are used as bactericides (27), and chlorocatechols are inhibitors of key catabolic enzymes (4, 29, 33). Thus, production of 4-chlorocatechol may have accounted for the relatively poor survival of strain RW1. It appears that by producing toxic intermediates, diaryl ether-degrading microorganisms could be negatively impacted during attempts to elicit in situ bioremediation. Judicious engineering of microorganisms for complete mineralization of diaryl ethers, as has been suggested previously (14, 32), may offer a way around this dilemma.

It is apparent that SOM controlled the rate at which 2-CDD was removed from soil by strain RW1. Bioavailability of hydrophobic pollutants can potentially limit degradation of organic chemicals in soils (1, 3, 30) and is typically controlled by physicochemical processes including diffusion, sorption/desorption, and dissolution (6, 22, 28). Relatively nonpolar chemicals such as dioxins primarily partition into SOM rather than mineral surfaces (7, 8, 13, 20). The correlation between increasing TOC and decreasing rates of removal of 2-CDD suggests that the rate of degradation was limited by sorption/desorption processes. Thus, as TOC content increases, the lower bioavailability of 2-CDD requires that the amount of biomass be increased to elicit effective degradation (Fig. 3). For soils with elevated levels of TOC, this means that the relative cost of remediation via bioaugmentation may be higher, due to the necessity of adding relatively more microorganisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Wittich for RW1, N. McClure for pNMBH20, and the Research Analytical Laboratory, University of Minnesota, for soil analyses.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (BCS-9318788). Financial support for R.U.H. was provided in part by a University of Minnesota Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adriaens P, Fu Q, Grbic-Gallic D. Bioavailability and transformation of highly chlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in anaerobic soils and sediments. Environ Sci Technol. 1995;29:2252–2260. doi: 10.1021/es00009a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur M F, Frea J I. Microbial activity in soils containing 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1987;7:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkovskii A L, Adriaens P. Microbial dechlorination of historically present and freshly spiked chlorinated dioxins and diversity of dioxin-dechlorinating populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4556–4562. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4556-4562.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartels I, Knackmuss H-J, Reineke W. Suicide inactivation of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida MT-2 by 3-halocatechols. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:500–505. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.3.500-505.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bollen W B, Norris L A. Influence of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on respiration in a forest floor and soil. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1979;62:648–652. doi: 10.1007/BF02027002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosma T N P, Middeldorp P J M, Schraa G, Zehnder A J B. Mass transfer limitation of biotransformation: quantifying bioavailability. Environ Sci Technol. 1997;31:248–252. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brzuzy L P, Hites R A. Estimating the atmospheric deposition of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans from soils. Environ Sci Technol. 1995;29:2090–2098. doi: 10.1021/es00008a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiou C T, Kile D E. Effects of polar and nonpolar groups on the stability of organic compounds in soil organic matter. Environ Sci Technol. 1994;28:1139–1144. doi: 10.1021/es00055a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engesser K-H, Fietz W, Fischer P, Schulte P, Knackmuss H-J. Dioxygenolytic cleavage of aryl ether bonds: 1,2-dihydro-1,2-dihydroxy-4-carboxyphenone as evidence for initial 1,2-dioxygenation in 3- and 4-carboxy biphenyl ether degradation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;69:317–322. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figge K, Wernitz A, Fortnagel P, Wittich R-M, Harms H. Dibenzofuran: Bakterielle Mineralisierung-Kinetik des Abbaus in heterogenen Systemen. Z Umweltchem Oekotox. 1991;3:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortnagel P, Harms H, Wittich R-M, Krohn S, Meyer H, Wilkes H, Francke W. Metabolism of dibenzofuran by Pseudomonas sp. strain HH69 and the mixed culture HH27. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1148–1156. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.4.1148-1156.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goss K U, Eisenreich S J. Adsorption of VOCs from the gas phase to different minerals in a mineral mixture. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:2135–2142. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunderson J L, Macintyre W G, Hale R C. pH-dependent sorption of chlorinated guaiacols on estuarine sediments: the effects of humic acids and TOC. Environ Sci Technol. 1997;31:188–193. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halden R U, Dwyer D F. Biodegradation of dioxins: a review. Bioremediat J. 1997;1:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halden, R. U., S. M. Tepp, B. G. Halden, and D. F. Dwyer. Influence of soil conditions on degradation of 3-phenoxybenzoic acid by Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes strain POB310 (pPOB) and two engineered bacterial strains. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Harms H, Wilkes H, Sinnwell V, Wittich R-M, Figge K, Francke W, Fortnagel P. Transformation of 3-chlorodibenzofuran by Pseudomonas sp. HH69. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;81:25–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90465-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harms H, Wittich R-M, Sinnwell V, Meyer H, Fortnagel P, Francke W. Transformation of dibenzo-p-dioxin by Pseudomonas sp. strain HH69. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1157–1159. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.4.1157-1159.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harms H, Zehnder A J B. Influence of substrate diffusion on degradation of dibenzofuran and 3-chlorodibenzofuran by attached and suspended bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2736–2745. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2736-2745.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harms H, Zehnder A J B. Bioavailability of sorbed 3-chlorodibenzofuran. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:27–33. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.27-33.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kile D E, Cjiou C T, Zhou H D, Li H, Xu O Y. Partition of nonpolar organic pollutants from water to soil and sediment organic matters. Environ Sci Technol. 1995;29:1401–1406. doi: 10.1021/es00005a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinkle B K, Schmidt E L. Transfer of the pea symbiotic plasmid pJB5JI in nonsterile soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3264–3269. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3264-3269.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luthy R G, Dzomback D A, Peters C A, Roy S B, Ramaswami A, Nackles D V, Nott B R. Remediating tar-contaminated soils at manufactured gas plant sites. Environ Sci Technol. 1994;28:A266–A276. doi: 10.1021/es00055a718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClure N C, Saint C P, Fry J C, Weightman A J. In: The construction of broad host range genetic markers and their use in monitoring the release of catabolic GEMS to aquatic environments. Christiansen C, Munk L, Villaden J, editors. Vol. 1. 1990. pp. 169–172. Proceedings of the 5th European Congress on Biotechnology.Munksgaard, International Publishers Ltd.Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Megharaj M, Wittich R-M, Blasco R, Pieper D H, Timmis K N. Superior survival and degradation of dibenzo-p-dioxin and dibenzofuran in soil by soil-adapted Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:109–114. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monna L, Omori T, Kodama T. Microbial degradation of dibenzofuran, fluorene, and dibenzo-p-dioxin by Staphylococcus auriculans DBF63. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:285–289. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.285-289.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruckdeschel G, Renner G, Schwarz K. Effects of pentachlorophenol and some of its known and possible metabolites on different bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2689–2692. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.11.2689-2692.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scow K M, Hutson J. Effect of diffusion and sorption on the kinetics of biodegradation: theoretical considerations. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1992;56:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strubel V, Engesser K-H, Fischer P, Knackmuss H-J. 3-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)catechol as substrate for proximal meta ring cleavage in dibenzofuran degradation by Brevibacterium sp. strain DPO 1361. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1932–1937. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1932-1937.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Umbreit T H, Hesse E J, Gallo M A. Bioavailability of dioxin in soil from a 2,4,5-T manufacturing site. Science. 1986;232:487–499. doi: 10.1126/science.3961492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner-Döbler I, Pipke R, Timmis K N, Dwyer D F. Evaluation of aquatic sediment microcosms and their use in assessing possible effects of introduced microorganisms on ecosystem parameters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1249–1265. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1249-1258.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkes H, Wittich R-M, Timmis K N, Fortnagel P, Francke W. Degradation of chlorinated dibenzofurans and dibenzo-p-dioxins by Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:367–371. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.367-371.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wittich R-M, Wilkes H, Sinnwell V, Francke W, Fortnagel P. Metabolism of dibenzo-p-dioxin by Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1005–1010. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.1005-1010.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]