Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate if adverse childhood experiences are associated with hormonal contraception discontinuation due to mood and sexual side effects.

Materials and Methods:

Women, ages 18-40 (N=826), with current and/or previous hormonal contraceptive use completed surveys on demographics, contraceptive history, and the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire. We characterized women into high (≥2 adverse experiences) and low (0 or 1) adverse childhood experience groups. We calculated risk ratios for associations between adverse childhood experiences and outcomes of interest using log binomial generalized linear models, and adjusted for relevant demographic variables.

Results:

Women in the high adverse childhood experiences group (n=355) were more likely to report having discontinued hormonal contraception due to decreases in sexual desire (adjusted risk ratio 1.44,1.03-2.00, p=0.030). Covariates included age, current hormonal contraception use, and various demographic variables associated with discontinuation. Adverse childhood experiences were not associated with mood or sexual side effects among current (n=541) hormonal contraceptive users.

Conclusions:

Self-reported adverse childhood experiences were associated with greater likelihood of discontinuing hormonal contraception due to behavioral side effects, particularly decreases in sexual desire. Identification of risk factors for behavioral side effects can assist patients and clinicians in making informed choices on contraception that minimize risk of early discontinuation.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, early life stress, hormonal contraception, women’s health, reward, sexual desire

Introduction

Hormonal contraception (HC) containing analogues of estradiol and progesterone are effective agents to prevent pregnancy and treat many gynecological conditions. Despite widespread use and safety, 30-50% of women will discontinue HC within 12 months of initiation, increasing the risk of unintended pregnancy [1,2]. Women who discontinue HC frequently cite mood or decreases in sexual desire as reasons for stopping [2] and in one prospective study, emotional and sexual side effects were the best predictor of discontinuation [1]. However, the distribution of side effects in the population is discontinuous, suggesting perhaps certain women experience mood and sexual side effects [3,4]. Studies suggest that HC may influence multiple brain functions relevant to mood and sexual desire such as the fear, stress reactivity, and reward systems [5,6]. The brain’s system for pleasure and reward, in particular, may represent a common link in governing both mood and sexual desire[7,8]. Specifically, evidence in humans and animals suggests that dysfunction of the brain’s reward system interferes with sexual desire and promotes negative mood states[9,10]. Currently, it is unclear what puts a woman at risk for HC side effects related to reward function.

One possible factor that might create vulnerability to HC-induced side effects related to reward function are adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Published data support that ACEs specifically influence the neurobiology of reward, creating vulnerability to deficits in reward function [11-13]. This vulnerability may be enhanced with HC-induced changes in brain steroid action. Receptors for gonadal steroids such as 17-beta estradiol and progesterone, and the neurosteroid allopregnanolone are replete across the reward system and promote its function [14-16]. The synthetic hormones found in HC differ from endogenous hormones in ways that could influence brain reward function, mood, and sexual desire. Importantly, HC types differ by the specific hormones they contain, delivery system, as well as systemic absorption. However, most synthetic hormones found in HC have differential steroid receptor binding [17,18] as well as differential metabolism into neurosteroids [19] compared to their endogenous counterparts. This differential pharmacology between endogenous hormones and HC has been linked to deficits in reward behavior in animals administered the oral contraceptive levonorgestrel and ethinyl estradiol [20]. While more research is needed, the aforementioned work provides biological plausibility that HC could influence some women’s capacity for feeling motivated towards pleasure. Women with ACEs who already demonstrate changes in reward neurobiology might be uniquely affected by the pharmacological differences of HC on the reward system, which would then be expected to increase risk of HC discontinuation due reward-related side effects.

Previous studies have emphasized the role that underlying depression and mood disorders have on increasing risk of HC side effects, specifically adverse changes in mood [27-30]. Changes to reward system neurobiology in individuals with ACEs have been found to predict later depressive symptoms[31,32]. As such, ACEs (rather than depression) appears to directly influence reward neurobiology, and might be a risk factor for reward-related HC side effects. Identifying these risk factors has important clinical value in terms of helping patients and clinicians make informed choices on HC that minimize the chances of discontinuation. The present study thus sought to evaluate the role of ACEs as a contributor to experiencing common HC side effects of negative mood and decreased sexual desire as well as discontinuing HC due to these side effects in a large sample of mainly American reproductive aged women.

Methods

Subjects

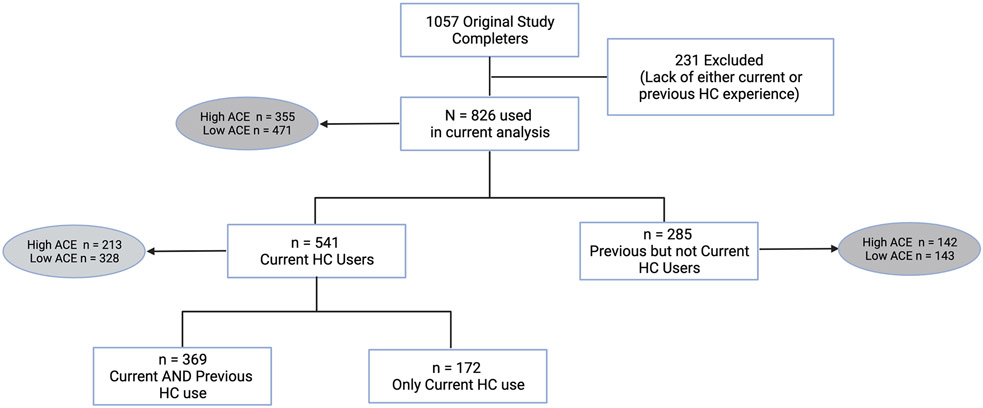

We recruited a sample of 1057 reproductive-age (18-40 years) cisgender women who were either current users or non-users of HC for an exploratory investigation on HC use. Of these, the present study utilized data from 826 women who reported current or past HC experience. 541 of the 826 were current HC users, of which the majority (68.2%) had previously used another HC before their current one. The remaining 285 of 826 women were not currently using any HC but had previously used a form of HC (Figure 1). Recruitment occurred via the internet using university listservs, social media, and ResearchMatch, a national health volunteer registry in the United States that has a population of volunteers who have consented to be contacted by researchers about health studies for which they may be eligible. We did not restrict enrollment by either nationality or geographic location. The COVID-19 pandemic limited capacity for in-person recruitment efforts that could have focused on more diverse and minority populations.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of sample population by hormonal contraception (HC) use and adverse childhood experience (ACE) grouping. High ACE = 2 or greater ACEs; Low ACE = 0-1 ACEs.

By self-report, women had to be in good health without current severe or unstable medical (including psychiatric) conditions. Women with chronic health conditions were eligible so long as they reported their condition to under stable control. Current HC users were using the same HC method for at least 3 months, while former users were free from HCs for at least three months with self-reported menstrual cycles between 21 and 35 days in length. We conducted surveys over the internet using the REDCap platform hosted at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus [33,34]. Surveys took approximately 40 minutes to complete and participants were enrolled in an optional lottery with an 8.3% chance of winning $100. If participants chose to be enrolled in the lottery, they were required to provide their name and email address following completion of the survey. Review and approval for this study was obtained from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. All participants provided consent to participation via an electronic consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board. All recruitment and study procedures occurred between June and October of 2020. Please see Supplemental Materials for additional information regarding inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Self-report measures

Participants completed surveys on demographic information, relationship status and health history, measures of depression (Center for Epidemiogical Studies Depression Scale, CES-D) and anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, GAD-7) and the Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire (ACE-Q). The CES-D is a widely used 10-item self-report questionnaire to assess symptoms of Major Depressive Disorer [35]. Each question (corresponding to various symptom domains of depression) is scored on a scale 0-3 based on frequency of symptoms, with a maximum score of 30. The GAD-7 consists of 7 questions each corresponding to symptoms of Generalized Anxiety Disorder that the individual rates on a scale of 0-3 based on frequency of symptoms, with a maximum score of 21 [36]. Scores on the CES-D and GAD-7 were treated as continuous, without specific cut-offs.

The ACE-Q queries the individual regarding the experience of 10 types of adversity before the age of 18. The ACE-Q includes three questions regarding abuse, two regarding neglect, and five regarding household/family dysfunction (Table 4). Scores can range from 0 to 10, with each endorsed experience increasing the score by 1. [37]. In prior studies by our group on neuropsychiatric consequences of ACEs, we found that an ACE score of two or more increased risk depression during perimenopause [21] and resulted in changes in neural activation associated with cognition [22,23]. We thus defined the high ACE group in the current study as individuals scoring 2 or higher on the ACE-Q.

Table 4.

Types of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) included in the ACE-Questionnaire [31]

| Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) assessed on the ACE-Q |

|---|

| Emotional abuse |

| Physical abuse |

| Sexual abuse |

| Emotional neglect |

| Physical neglect |

| Parental loss |

| Witnessing domestic violence |

| Substance use disorder in household |

| Mental illness in household |

| Imprisonment of a household member |

Participants currently taking HC were asked to indicate the type of HC they were taking, and were provided with options to indicate both general category (pill, intrauterine system, implant, etc) as well as specific formulation. Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) and hormonal intrauterine systems (IUS) were the most commonly used HC, reported by 45.9% and 42.4% of those currently using HC, respectively. Etonogestrel implants were endorsed by 6.5% of the group, etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol vaginal rings by 4.4%, depot medroxyprogesterone injections by 1.1%. Given the low percentage of women reporting other methods of HC besides IUS and OCPs, we grouped methods into IUS/Low-systemic progestin only users (46%), systemic progestin only method users (10%), and combined systemic progestin and estrogen method users (43%). Current users were subsequently asked what side effects they were currently experiencing due to their HC. Options included “Physical side effects (e.g. nausea, sore breasts, weight gain), “Mood changes (e.g. feeling down or anxious)”, “Decreased libido/sexual desire”, “Other”, or “No side effects”. We focused on self-reports of mood changes as described above instead of depression as the former could encompass mood lability, irritability as well as depressed mood. In order to assess discontinuation, participants who indicated previous use of HC were asked the reason to indicate the reason for discontinuation (“Side effects”; “Cost”; “Logistics (e.g. remembering to take pill)”; “No longer needed/wanted it (e.g. no risk of pregnancy, trying to get pregnant)”; “Other”). If the individual indicated that the reason for discontinuation was “Side effects”, they were subsequently asked if they discontinued due to the any of the following side effects: “Physical side effects (e.g. nausea, sore breasts, weight gain); “Mood changes (e.g. feeling down or anxious)” ;“Decreased libido/sexual desire”;or “Other.” Further details on survey questions are found in the supplemental materials.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and ACE variables were summarized overall and by discontinuation and/or HC group. Differences were tested with two-sample t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate.

For the sample (N = 826), we calculated risk ratios for association between ACE groups and discontinuation due to changes in mood or decreases in sexual desire using log binomial generalized linear models. Given previous literature that younger women and those with a previously diagnosed mood disorder may be more prone to HC related mood side effects[28,38], we chose to adjust for age and history and mood disorder in our models. We also adjusted for current HC use given that not all current HC users had previously discontinued a form of HC before, and thus inevitably had a different frequency of discontinuation. Additional covariates included demographic variables associated with discontinuation at the level α=0.2. For discontinuation due to adverse changes in mood these variables included ethnicity, relationship status, education, and history of eating disorder. For discontinuation due to decreased sexual desire, adjusted demographic variables associated with discontinuation included relationship status and education. Two-sided p-values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Assumptions for statistical power include 2-sided type I error of 5%, 80% power and prevalence of high ACE women of 43% in the full cohort, n=826. Assuming a discontinuation rate of 23% for mood symptoms, this study has power to detect an increase of 8.7% or more (risk ratios= 1.38). For a baseline rate of sexual side effects of 11%, this study can detect an increase of 7% (risk ratio=1.63).

Within the subgroup of current HC users, n=541, the prevalence of high ACE women was 40%. Assuming 19% of low ACE women experience current mood concerns attributed to their HC, this study can detect an increase of 10.5% or more (Risk Ratio=1.55) or higher with 80% power. For current experience of decreased sexual desire, the rate in low ACE women was 25%. This study had 80% power to detect an increase of 11.5% or greater in high ACE women (risk ratio=1.46).

We then used similar models to evaluate the role of specific ACE types of discontinuation outcomes (Supplemental Material). The effects of contraceptive type on current mood or sexual side effects were tested with the same covariates in log binomial generalized linear models, and power analyses for these additional comparisons are detailed in Supplemental Material. A standard statistical significant level of α = 0.05 was used. We conducted all statistical analyses using R version 4.0.2 [39].

3. Results

Sample Characteristics

The 826 study completers included in analyses on discontinuation all had HC experience either currently and/or in the past. The sample largely identified as white (n=694, 86%) and had an average age of 29 (SD 5). Sixty-five percent (n=541) were current users of hormonal contraceptives and 43% percent (n=355) of the 826 reported 2 or greater ACEs and were thus classified as “high ACE.” Among the current users, n=213 (39%) were in the high ACE group. Among women not currently using HC, n=285, 49.8% were in the high ACE group. There were significantly more individuals meeting criteria for the high ACE group among women not currently using HC compared to those currently using HC (p=0.005). A breakdown on the sample can be found in Figure 1, with additional details for the entire sample and current users only found in Table 1 and Table S1, respectively.

Table. 1.

Demographics of study population and those who discontinued hormonal contraception (HC) due to adverse changes in mood and decreased sexual desire.

| Demographics variable (row N [%] or mean [SD]) |

Total current and previous HC users (N = 826) |

Discontinued due to changes in mood (n = 212) |

p value | Discontinued due to decreased sexual desire (n = 114) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 29.0 (5.0) | 28.6 (4.8) | 0.256 | 29.1 (4.7) | 0.773 |

| Race | 0.498 | 0.509 | |||

| Asian | 46 | 9 (19.6%) | 6 (13.0%) | ||

| Black/African American | 29 | 5 (17.2%) | 4 (13.8%) | ||

| White | 694 | 181 (26.1%) | 100 (14.4%) | ||

| Other/multiracial | 57 | 17 (29.8%) | 4 (7.0%) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.068 | 0.129 | |||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 753 | 185 (24.6%) | 99 (13.1%) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 59 | 22 (37.3%) | 13 (22.0%) | ||

| Other/multiple ethnicities | 14 | 5 (35.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | ||

| Sexual orientation | 0.494 | 0.800 | |||

| Heterosexual | 653 | 161 (24.7%) | 87 (13.3%) | ||

| Bisexual | 128 | 37 (28.9%) | 21 (16.4%) | ||

| Homosexual/gay/lesbian | 16 | 4 (25.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | ||

| Other | 29 | 10 (34.5%) | 4 (13.8%) | ||

| Relationship status | 0.008 | 0.043 | |||

| In a relationship | 592 | 167 (28.2%) | 91 (15.4%) | ||

| Single | 234 | 45 (19.2%) | 23 (9.8%) | ||

| Household income | 0.917 | 0.656 | |||

| Less than $25,000 | 55 | 14 (25.5%) | 8 (14.5%) | ||

| $25,000-$75,000 | 323 | 87 (26.9%) | 47 (14.6%) | ||

| $75,000-$200,000 | 378 | 93 (24.6%) | 47 (12.4%) | ||

| $200,000 or more | 70 | 18 (25.7%) | 12 (17.1%) | ||

| Highest level of education | 0.260 | 0.288 | |||

| High school diploma or less | 111 | 31 (27.9%) | 10 (9.0%) | ||

| College degree | 404 | 111 (27.5%) | 60 (14.9%) | ||

| Master's/professional degree | 311 | 70 (22.5%) | 44 (14.1%) | ||

| History of mood disorder | 0.248 | 0.834 | |||

| Mood disorder | 300 | 84 (28.0%) | 40 (13.3%) | ||

| None | 526 | 128 (24.3%) | 74 (14.1%) | ||

| History of anxiety disorder | 0.630 | 0.265 | |||

| Anxiety disorder | 359 | 89 (24.8%) | 44 (12.3%) | ||

| None | 467 | 123 (26.3%) | 70 (15.0%) | ||

| History of Eating disorder | 0.071 | 0.567 | |||

| Eating disorder | 62 | 22 (35.5%) | 10 (16.1%) | ||

| None | 764 | 190 (24.9%) | 104 (13.6%) | ||

| History of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder | 0.558 | 1 | |||

| Post-traumatic Stress Disorder | 66 | 19 (28.8%) | 9 (13.6%) | ||

| None | 760 | 193 (25.4%) | 105 (13.8%) | ||

| Total ACE | 0.030 | 0.011 | |||

| Low ACE (0-1) | 471 | 107 (22.7%) | 52 (11.0%) | ||

| High ACE (>=2) | 355 | 105 (29.6%) | 62 (17.5%) | ||

| HC group | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Current HC users | 541 | 74 (13.7%) | 38 (7.0%) | ||

| Former HC users | 285 | 138 (48.4%) | 76 (26.7%) | ||

| CESD | 9.5 (5.7) | 9.6 (5.9) | 0.568 | 9.1 (5.7) | 0.512 |

| GAD-7 | 6.5 (4.8) | 6.8 (5.0) | 0.366 | 6.9 (5.4) | 0.342 |

Variables were summarized with means and standard deviations for continuous variables and with frequencies and percentages for categorical variables overall and by side effect and outcome type. Differences were tested with two-sample t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Mood disorders consisted of Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder. ACE – Adverse Childhood Experiences, HC – Hormonal Contraceptive, CESD – Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, GAD-7 – Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

Discontinuation of hormonal contraception due to adverse changes in mood

Women categorized as high ACE (≥2 ACEs) had higher prevalence of discontinuation due to adverse mood changes compared to low ACE women (29.6% vs 22.7%, p=0.030). Please see Table 1 for a full list of demographic variables and their relationship to discontinuation due to adverse changes in mood.

After adjustment for relevant confounders, increased risk of discontinuation due to adverse changes in mood for high ACE women was no longer statistically significant (aRR 1.10, 0.90-1.35, p=0.338). Please see Table 2 for additional details.

Table 2.

Risk ratios for discontinuation of hormonal contraception (HC) due to adverse changes in mood.

|

Full model with TOTAL ACE: Predictor of discontinuing HC due to changes in mood |

Unadjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.281 | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.020 |

| Ethnicity (ref: not Hispanic/Latino) | 0.081 | 0.045 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.52 (1.07, 2.16) | 0.021 | 1.33 (1.00, 1.76) | 0.052 |

| Other/multiple ethnicities | 1.45 (0.71, 2.97) | 0.304 | 1.11 (0.83, 1.48) | 0.469 |

| Relationship status (ref: single) | ||||

| In a relationships | 1.47 (1.10, 1.96) | 0.010 | 1.37 (1.06, 1.76) | 0.014 |

| Education (ref: HS diploma or less) | 0.266 | 0.287 | ||

| College degree | 0.98 (0.70, 1.38) | 0.925 | 1.27 (0.94, 1.73) | 0.121 |

| Master's/professional degree | 0.81 (0.56, 1.16) | 0.244 | 1.13 (0.79, 1.62) | 0.508 |

| History of mood disorder | 1.15 (0.91, 1.46) | 0.244 | 1.13 (0.91, 1.39) | 0.263 |

| History of eating disorder | 1.43 (1.00, 2.04) | 0.051 | 1.42 (1.10, 1.84) | 0.007 |

| Total ACE (ref: low [0-1]) | ||||

| High [>=2] | 1.30 (1.03, 1.64) | 0.025 | 1.10 (0.90, 1.35) | 0.338 |

Unadjusted bivariate risk ratios are presented with 95% confidence intervals and p values. Adjusted Risk ratios were estimated using a log binomial generalized linear model with ACE group as the primary predictor and were adjusted for age, current HC use, history of mood disorder (Major Depressive Disorder or Bipolar Disorder) and for demographic variables associated with discontinuation at the level α = 0.2 or below (ethnicity, relationship status, education, history of eating disorder). ACE -Adverse Childhood Experiences, HC – Hormonal Contraceptive.

Discontinuation of hormonal contraception due to decreases in sexual desire.

High ACE women had a higher frequency of discontinuation due to decreases in sexual desire (17.5% of women the high ACE group vs 11% in the low ACE group, p=0.011). Please see Table 1 for a full list of demographic variables and their relationship to discontinuation due to decreases in sexual desire.

After adjustment for potential confounders, increased risk of discontinuation due to decreases in sexual desire was found for high ACE women (1.44, 1.03-2.00, p=0.030, Table 3). Please see Table 3 for details.

Table. 3.

Risk ratios for discontinuation of hormonal contraception (HC) due to decreased sexual desire

|

Full model with TOTAL ACE: Predictor of discontinuing HC due to decreased sexual desire |

Unadjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

p value | Adjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.787 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) | 0.096 |

| Relationship status (ref: single) | ||||

| In a relationship | 1.56 (1.02, 2.41) | 0.042 | 1.49 (0.98, 2.24) | 0.060 |

| Education (ref: HS diploma or less) | 0.247 | 0.029 | ||

| College degree | 1.65 (0.87, 3.11) | 0.123 | 2.03 (1.10, 3.77) | 0.024 |

| Master's/professional degree | 1.57 (0.82, 3.01) | 0.175 | 2.16 (1.11, 4.19) | 0.023 |

| Total ACE (ref: low [0-1]) | ||||

| High [>=2] | 1.58 (1.12, 2.23) | 0.009 | 1.44 (1.03, 2.00) | 0.030 |

Unadjusted bivariate risk ratios are presented with 95% confidence intervals and p values.

Adjusted risk ratios were estimated using a log binomial generalized linear model with ACE group as the primary predictor and were adjusted for age, current HC use, history of mood disorder (Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder) and for demographic variables associated with discontinuation at the level α = 0.2 or below (relationship status and education). ACE -Adverse Childhood Experiences, HC – Hormonal Contraceptive.

Current adverse changes in mood due to hormonal contraception

Among current users (n=541), no significant differences were found with regards to ACE group and current reported mood changes due to HC (Table S1).Women reporting reported higher levels of depression as measured by the CES-D (p=0.001) and higher levels of anxiety as measured by the GAD-7 (p < 0.001). Current mood changes attributed to HC were not different depending on reported history of mood disorder (p=0.911) or history of anxiety disorder (p= 0.132). No other significant differences were found. (Table S1)

Current decreases in sexual desire due to hormonal contraception

Among current users (n=541), No significant differences were found with regards to ACE group and current reported decreases in sexual desire due to HC. Women reporting current decreases in sexual desire due to HC had higher anxiety scores as measured by the GAD-7 (p=0.05), however depression scores as measured by the CES-D were not elevated (p=0.250) (Table S1).

Types of hormonal contraception

Among current users (n=541), there were no significant differences in the risk of mood changes between different HC categories (Table S2). For decreases in sexual desire, those on a combined progestin and estrogen were more likely to experience decreases in sexual desire compared to those on hormonal IUS (aRR 1.52, 1.09-2.12, p=0.015). Women on progestin-only methods were also more likely to report decreases in sexual desire compared to women on hormonal IUS (aRR 1.67, 1.02-2.75, p=0.041) (Table S2).

Discussion

Findings and interpretation

In this large cross-sectional study of 826 current and/or former HC users, we hypothesized that ACE would increase risk for HC discontinuation due to adverse changes in mood and decreases in sexual desire. In models adjusting for relevant confounders, our results suggest there may be an association between high ACE scores and HC discontinuation due to decreased sexual desire. An association between ACE and HC discontinuation due to adverse changes in mood did not survive correction. For women who are current users, high ACE was not related to current side effects. Adverse changes in mood did not differ between categories of HC; however, women currently on hormonal IUS reported lower prevalence of decreased sexual desire.

The percentage of individuals in the United States with a history of two or more ACEs is likely around 35%, which is consistent with the 40% in our sample, especially since women tend to experience more ACEs than men [40]. Human and animal data have shown that ACEs are associated with deficits in the brain’s reward system [12,41,42]. Given evidence that HC can also blunt reward processes [20,43,44], individuals with high ACE might be at increased risk for side effects that depend on intact reward function: mood and sexual desire. In line with our hypothesis, high ACE women had higher rates of discontinuation due to decreases in sexual desire. Following adjustment for confounders, we did not find increased risk of discontinuation due to adverse mood changes in high ACE women. This might be due to a potential benefit on mood by HC in some women. Specifically, despite evidence that HC can reduce positive affect[45], HC have been found in several studies to stabilize variation in affect which might be viewed as beneficial in some women [45-48]. HC-induced mood stabilization in high ACE women could be particularly desirable given that this population is at risk for affective instability [49].

Our results suggests that high ACE women may be more sensitive to the effects of HC on sexual desire. Various types of HC are known to decrease concentrations of endogenous steroids involved in sexual desire including androgens [50,51], allopregnanolone [52,53] and estradiol [54,55]. While many women’s sexual desire may not be affected by these changes [56], the possibility that high ACE women are more vulnerable to decreases in endogenous steroids is suggested by literature on ACEs and neuropsychiatric consequences in the context of hormonal changes. For example, ACEs increase the risk of postpartum depression [24], pre-menstrual mood symptoms [25,26], and mood and cognitive changes in menopause [21,23]. Additional research is needed to determine if this is the case with high ACEs, HC, and sexual desire. If confirmed, such women might benefit from contraceptives with less influence on endogenous hormones (such as hormonal or non-hormonal IUS). In support of this, substituting estradiol for ethinyl estradiol has less influence on levels of androgens and ameliorates previous deficits in sexual desire [57].

In current HC users, the high ACE group was not found to be associated with current adverse changes in mood or decreases in sexual desire. We propose that this is likely due to a survivor effect which has been described in literature on HC and behavioral effects [58], such that the women still taking HC are less likely to be vulnerable to side effects. Those women who did report changes in mood that they attributed to current use of HC had higher depression and anxiety scores, which might be reflective of their current reported side-effects. Similarly, those reporting decreased sexual desire with their current HC method had higher anxiety scores. As increased levels of distress and anxiety can be both a consequence and contributor to decreased sexual desire[59,60], additional research would be necessary to disentangle the relationship between HC-induced sexual dysfunction and anxiety.

There were no differences in the frequency of mood side effects between different categories of HC. However, hormonal IUS users were less likely to report decreased sexual desire compared to both combined progestin plus estrogen methods and progestin-only methods. Due to the low number of women in the study currently taking a progestin-only method, we had limited powered to detect differences. Yet our result is consistent with prior literature that found improved sexual desire on hormonal IUS compared to both other types of HC and no contraception [61]. Although some studies have found differences in the effects of various HC on either mood or sexual desire [38,62], larger prospective studies are needed to further clarify individual progestin and estrogen effects on mood and sexual desire.

Strengths and weaknesses

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate ACEs as a risk factor for HC side effects and discontinuation. Additional strengths of this study include a large sample size and inclusion of current and former HC users. The fact that the sample was largely white and highly educated does limit generalizability of our findings. Importantly though, our sample did reflect the general population in terms of rates of lifetime mood and anxiety disorders which might be expected to influence reporting and vulnerability to side effects [63]. Our reliance on self-report for all measures, including basic eligibility information on a participant’s health has inherent limitations compared to in-person assessment and exam. As with similar surveys that ask participants about events in the past, recall bias was inevitable in our study. Like all survey research, we also cannot rule out the possibility that some individuals may not have felt comfortable providing honest answers to some questions. Another limitation of this study was lack of information on specific type of HC that women had discontinued, as this might have revealed which HC types were most likely to induce behavioral side-effects in the high ACE group and the sample as a whole. In addition, the cross-sectional, observational nature of the present study prevents drawing conclusions about the longitudinal or potentially causal effects of HC on mood and sexual side effects. While we attempted to adjust for relevant confounders, there are inevitably other variables that might influence the experience of both current side effects and discontinuation due to certain side effects. Future studies will consider data on additional factors such which specific HC was discontinued and pre-existing attitudes on contraception and sexuality. It is also possible that voluntary versus coercive use of contraception might influence side effects and discontinuation. Given the potential confounds, it will be important to perform future prospective, longitudinal studies using specific measures of mood and sexual desire to further explore these important questions.

Similarities and differences in relation to other studies

Several previous studies have found associations between a history of mood disorder, reported HC-induced negative changes in mood, and HC discontinuation [27-30,64]. In the present study, women with and without a reported history of mood disorders did not differ either in rates of current changes in mood or decreases in sexual desire (Table S1) or in reported rates of HC discontinuation due to these side effects (Table 1). As above, women who reported current mood changes or decreased sexual desire did score higher on measures of depression and anxiety (Table S1).

The above previous studies on mood disorders and HC side effects beg the question as to whether our major finding of increased discontinuation due to decreased sexual desire in high ACE individuals was actually due to depression. The cross-sectional nature of our study does not allow us to definitively disentangle such a relationship. However, combined lines of evidence suggest that ACEs on their own can exert independent effects, separate from depression, on sexual desire. First, as above, a history of mood disorder was not related to previous discontinuation due to decreased sexual desire (Table 1). Second, women in the present study who had previously discontinued HC due to decreased sexual desire did not demonstrate increased scores on measures of depression or anxiety (Table S1). This suggests that current levels of depression or anxiety are not predictive of past HC discontinuation due to decreased sexual desire. Third, although previous studies have found links to prior mood disorders and various HC side effects, these studies have not specifically looked at decreased sexual desire [27-30,64]. Finally, various experiments have demonstrated that ACEs impact reward neurobiology, which then puts individuals at risk for depression [31,32]. This temporal order of events suggests that depression is not required for ACEs to engender deficits in reward function like decreased sexual desire. Of course, confirming this will require prospective trials of HC that take ACEs into account.

Future Directions

To understand the underlying vulnerability to sexual side effects observed in the high ACE group when taking HCs, prospective trials (stratified by ACE status) that use neuroimaging to asses reward functioning in the brain are necessary. Recruitment of a diverse sample that resembles the general population will also be important for generalizability. In addition to testing various HC types, these trials would ultimately dissect effects of HC components, such as ethinyl estradiol and various progestins. The results of this could then be used to guide clinicians and patients in the selection of HC with the least risk of brain-related side effects.

Conclusions

The results of the present study demonstrate an association between high ACEs and reported HC discontinuation due to decreased sexual desire. This group, which is approximately 40% of individuals [40], could potentially represent a population vulnerable to HC-induced side effects related to central reward function. Additional prospective research is needed to confirm this, especially in diverse samples that better reflect the general population. If found, incorporating ACE measurements into research could assist with better understanding variation in individual response to HC and assist clinicians in personalizing treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the Center for Women’s Health Research at the University of Colorado (AMN) and NIH grants R01 CA215587 (CNE), R01 DA037289 (CNE), and U54AG062319 (AMN, PI Kohrt).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: CNE has served on advisory boards for Asarina Pharma and Sage Therapeutics and has been a consultant and received grant support from Sage Therapeutics. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Simmons RG, Sanders JN, Geist C, et al. Predictors of contraceptive switching and discontinuation within the first 6 months of use among Highly Effective Reversible Contraceptive Initiative Salt Lake study participants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:376.e1–376.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sanders SA, Graham CA, Bass JL, et al. A prospective study of the effects of oral contraceptives on sexuality and well-being and their relationship to discontinuation. Contraception. 2001;64:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Robakis T, Williams KE, Nutkiewicz L, et al. Hormonal Contraceptives and Mood: Review of the Literature and Implications for Future Research. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gingnell M, Engman J, Frick A, et al. Oral contraceptive use changes brain activity and mood in women with previous negative affect on the pill—A double-blinded, placebo-controlled randomized trial of a levonorgestrel-containing combined oral contraceptive. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1133–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lewis CA, Kimmig A-CS, Zsido RG, et al. Effects of Hormonal Contraceptives on Mood: A Focus on Emotion Recognition and Reactivity, Reward Processing, and Stress Response. Curr Psychiatry Rep [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2020 Jul 9];21. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6838021/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Montoya ER, Bos PA. How Oral Contraceptives Impact Social-Emotional Behavior and Brain Function. Trends Cogn Sci. 2017;21:125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Eldar E, Roth C, Dayan P, et al. Decodability of Reward Learning Signals Predicts Mood Fluctuations. Curr Biol. 2018;28:1433–1439.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Micevych PE, Meisel RL. Integrating Neural Circuits Controlling Female Sexual Behavior. Front Syst Neurosci [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2021 Feb 17];11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5462959/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kingsberg SA, Clayton AH, Pfaus JG. The Female Sexual Response: Current Models, Neurobiological Underpinnings and Agents Currently Approved or Under Investigation for the Treatment of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:915–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML. Pleasure Systems in the Brain. Neuron. 2015;86:646–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Birnie MT, Kooiker CL, Short AK, et al. Plasticity of the Reward Circuitry After Early-Life Adversity: Mechanisms and Significance. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87:875–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Novick AM, Levandowski ML, Laumann LE, et al. The effects of early life stress on reward processing. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;101:80–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Matthews K, Robbins TW. Early experience as a determinant of adult behavioural responses to reward: the effects of repeated maternal separation in the rat. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Willing J, Wagner CK. Progesterone receptor expression in the developing mesocortical dopamine pathway: importance for complex cognitive behavior in adulthood. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:207–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yoest KE, Quigley JA, Becker JB. Rapid effects of ovarian hormones in dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens. Horm Behav. 2018;104:119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vashchinkina E, Manner AK, Vekovischeva O, et al. Neurosteroid Agonist at GABA A Receptor Induces Persistent Neuroplasticity in VTA Dopamine Neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:727–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Escande A, Pillon A, Servant N, et al. Evaluation of ligand selectivity using reporter cell lines stably expressing estrogen receptor alpha or beta. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:1459–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Africander D, Verhoog N, Hapgood JP. Molecular mechanisms of steroid receptor-mediated actions by synthetic progestins used in HRT and contraception. Steroids. 2011;76:636–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Giatti S, Melcangi RC, Pesaresi M. The other side of progestins: effects in the brain. J Mol Endocrinol. 2016;57:R109–R126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Santoru F, Berretti R, Locci A, et al. Decreased allopregnanolone induced by hormonal contraceptives is associated with a reduction in social behavior and sexual motivation in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231:3351–3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hall KS, White KO, Rickert VI, et al. Influence of depressed mood and psychological stress symptoms on perceived oral contraceptive side effects and discontinuation in young minority women. Contraception. 2012;86:518–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shelef DQ, Raine-Bennett T, Chandra M, et al. The association between depression and contraceptive behaviors in a diverse sample of new prescription contraception users. Contraception. 2021;S0010782421003735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hall KS, Steinberg JR, Cwiak CA, et al. Contraception and mental health: a commentary on the evidence and principles for practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:740–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Segebladh B, Borgström A, Odlind V, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders and premenstrual dysphoric symptoms in patients with experience of adverse mood during treatment with combined oral contraceptives. Contraception. 2009;79:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hanson JL, Hariri AR, Williamson DE. Blunted Ventral Striatum Development in Adolescence Reflects Emotional Neglect and Predicts Depressive Symptoms. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Corral-Frías NS, Nikolova YS, Michalski LJ, et al. Stress-related anhedonia is associated with ventral striatum reactivity to reward and transdiagnostic psychiatric symptomatology. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2605–2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Björgvinsson T, Kertz SJ, Bigda-Peyton JS, et al. Psychometric Properties of the CES-D-10 in a Psychiatric Sample. Assessment. 2013;20:429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Epperson CN, Sammel MD, Bale TL, et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Risk for First-Episode Major Depression During the Menopause Transition. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:298–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shanmugan S, Loughead J, Cao W, et al. Impact of Tryptophan Depletion on Executive System Function during Menopause is Moderated by Childhood Adversity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:2398–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shanmugan S, Satterthwaite TD, Sammel MD, et al. Impact of early life adversity and tryptophan depletion on functional connectivity in menopausal women: A double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;84:197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Skovlund CW, Mørch LS, Kessing LV, et al. Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. Available from: https://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Giano Z, Wheeler DL, Hubach RD. The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the U.S. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mehta MA, Gore-Langton E, Golembo N, et al. Hyporesponsive reward anticipation in the basal ganglia following severe institutional deprivation early in life. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010;22:2316–2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hanson JL, Albert D, Iselin A-MR, et al. Cumulative stress in childhood is associated with blunted reward-related brain activity in adulthood. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11:405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Scheele D, Plota J, Stoffel-Wagner B, et al. Hormonal contraceptives suppress oxytocin-induced brain reward responses to the partner’s face. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11:767–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Abler B, Kumpfmüller D, Grön G, et al. Neural Correlates of Erotic Stimulation under Different Levels of Female Sexual Hormones. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2019 Nov 6];8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3572100/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jarva JA, Oinonen KA. Do oral contraceptives act as mood stabilizers? Evidence of positive affect stabilization. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Graham CA, Sherwin BB. The relationship between mood and sexuality in women using an oral contraceptive as a treatment for premenstrual symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1993;18:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sutker PB, Libet JM, Allain AN, et al. Alcohol Use, Negative Mood States, and Menstrual Cycle Phases. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1983;7:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Paige KE. Effects of oral contraceptives on affective fluctuations associated with the menstrual cycle. Psychosom Med. 1971;33:515–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Teicher MH, Ohashi K, Lowen SB, et al. Mood dysregulation and affective instability in emerging adults with childhood maltreatment: An ecological momentary assessment study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bancroft J, Sherwin BB, Alexander GM, et al. Oral contraceptives, androgens, and the sexuality of young women: I. A comparison of sexual experience, sexual attitudes, and gender role in oral contraceptive users and nonusers. Arch Sex Behav. 1991;20:105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Segall-Gutierrez P, Du J, Niu C, et al. Effect of subcutaneous depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-SC) on serum androgen markers in normal-weight, obese, and extremely obese women. Contraception. 2012;86:739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rapkin AJ, Morgan M, Sogliano C, et al. Decreased neuroactive steroids induced by combined oral contraceptive pills are not associated with mood changes. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1371–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].NAPPI RE, ABBIATI I, LUISI S, et al. Serum Allopregnanolone Levels Relate to FSFI Score During the Menstrual Cycle. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mishell DR, Thorneycroft IH, Nakamura RM, et al. Serum estradiol in women ingesting combination oral contraceptive steroids. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;114:923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cappelletti M, Wallen K. Increasing women’s sexual desire: The comparative effectiveness of estrogens and androgens. Horm Behav. 2016;78:178–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Alexander GM, Sherwin BB, Bancroft J, et al. Testosterone and sexual behavior in oral contraceptive users and nonusers: a prospective study. Horm Behav. 1990;24:388–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Racine N, Zumwalt K, McDonald S, et al. Perinatal depression: The role of maternal adverse childhood experiences and social support. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:576–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bertone-Johnson ER, Whitcomb BW, Missmer SA, et al. Early Life Emotional, Physical, and Sexual Abuse and the Development of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Longitudinal Study. J Womens Health. 2014;23:729–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Perkonigg A, Yonkers KA, Pfister H, et al. Risk Factors for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder in a Community Sample of Young Women: The Role of Traumatic Events and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Caruso S, Cianci S, Cariola M, et al. Improvement of Low Sexual Desire Due to Antiandrogenic Combined Oral Contraceptives After Switching to an Oral Contraceptive Containing 17β-Estradiol. J Womens Health. 2017;26:728–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Oinonen KA, Mazmanian D. To what extent do oral contraceptives influence mood and affect? J Affect Disord. 2002;70:229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].DeRogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D’Agostino D, et al. Validation of the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised for Assessing Distress in Women with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder. J Sex Med. 2008;5:357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Basson R, Gilks T. Women’s sexual dysfunction associated with psychiatric disorders and their treatment. Womens Health. 2018;14:1745506518762664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Skrzypulec V, Drosdzol A. Evaluation of quality of life and sexual functioning of women using levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive system--Mirena. Coll Antropol. 2008;32:1059–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Burrows LJ, Basha M, Goldstein AT. The Effects of Hormonal Contraceptives on Female Sexuality: A Review. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2213–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Lundin C, Wikman A, Bixo M, et al. Towards individualised contraceptive counselling: clinical and reproductive factors associated with self-reported hormonal contraceptive-induced adverse mood symptoms. BMJ Sex Reprod Health [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2021 Apr 18]; Available from: http://srh.bmj.com/content/early/2021/01/15/bmjsrh-2020-200658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.