Abstract

Aims:

This study identified the information needs of people with diabetes aged 65 and older through surveys and focus groups to inform the development of a patient-centered educational decision aid for diabetes care, SEE-Diabetes (Support-Engage-Empower-Diabetes).

Methods:

We conducted survey (N=37) and three focus groups (N=9). The survey collected demographics, diabetes duration, insulin usage, and clinic notes accessibility through a patient portal. In focus groups, participants evaluated the Assessment and Plan section of three selected deidentified clinic notes to assess readability and helpfulness for diabetes care.

Results:

The mean age of participants was 66 (24–82, SD=12), and 22 were female (60%). The mean diabetes duration was 20.9 years (1–63, SD=15). Most participants (80%) read their clinical notes via patient portal. In the focus groups, the readability of clinic notes was noted as a primary concern because of medical abbreviations and poor formatting. Participants found the helpfulness of clinic notes was negatively impacted by vague or insufficient self-care information.

Conclusions:

We found the high use of patient portal for reading clinic notes, which offers a use case opportunity for the proposed SEE-Diabetes educational aid. Feedback about the readability and helpfulness of clinic notes will be considered during the design process.

Keywords: Diabetes, Older adults, Patient-centered education, Diabetes self-management education and support, Survey, Focus groups

1. Introduction

The National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020 estimated a 26.8% prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in Americans 65 years or older[1]. With increasing age, the number of comorbidities and functional limitations also increases, contributing to the complexity of care and diabetes management[2]. The unique considerations of care in older people with diabetes include cognitive impairment, physical and neuropathic complications[3]. Older people are disproportionately impacted and at risk for disability, such as visual loss, immobility, falls, and daily mental health symptoms[4]. Thus, care plans for diabetes management in older people should be individualized with treatment goals based on the assessment of medical, psychological, functional, social domains and geriatric syndromes, such as falls, frailty, dementia, and incontinence[3-5].

One such care plan includes diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES), an evidence-based diabetes management model[6]. DSMES helps people with diabetes navigate daily self-care, improve clinical outcomes and prevent or delay complications[7-14]. Although DSMES services have well-documented benefits, less than 5% of Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes and only 6.8% of privately insured people with diabetes in the United States participate in DSMES services within the first year of diagnosis[7,15]. ADCES7 Self-Care Behaviors™ is a robust DSMES framework launched by the Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists (ADCES). ADCES7 is used to assist people with diabetes to achieve behavior change on the seven principles of Healthy Coping, Healthy Eating, Being Active, Taking Medication, Monitoring, Reducing Risks, and Problem Solving[16].

In 2010, the OpenNotes project started to investigate the effects of sharing notes between physicians and patients[17]. DesRoches et al.[18] conducted a survey to investigate the experiences of reading clinic notes via a patient portal in people aged 65 and older. The study reported older patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease, who read their notes improved recall of their treatment plan and prescribed medication. Moreover, reading clinic notes helped older patients understand and feel in control of their medications. The benefits of sharing notes led the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to propose a new rule, the 21st Century Cures Act Final Rule, to improve the interoperability of electronic health information. The Cures Act focuses on the accessibility of patients’ health information so that patients can access their electronic health information at no cost[19]. Since the 21st Century Cures Act became law on December 13, 2016, patients have had the right to view, download, and transmit their electronic health records (EHR)[20].

Our research team investigated the distribution of DSMES information among the seven ADCES7 principles in follow-up visit notes at the University of Missouri Health Care[21]. The results showed, regardless of patient characteristics, Monitoring was the most mentioned DSMES principle in the note sections, while Being Active and Healthy Coping were the least common. The study suggested a lack of patient-centered education for follow-up visits. Patient-centered education has shared decision-making (SDM) as a key component[22]. Delivering patient-centered education through SDM has been shown to improve several outcomes, such as patient satisfaction, doctor-patient communication, disease-specific knowledge, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes[23-26]. Although many studies support the benefits of shared clinic notes[27-30], current clinic notes are not effective for older adults with low health literacy who have particular difficulty managing their conditions[31-33].

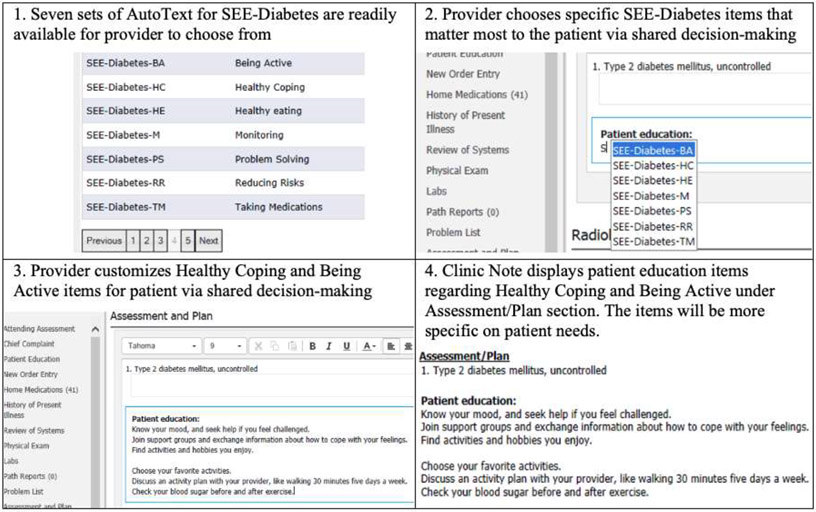

To our knowledge, the role of patient-centered DSMES created via SDM based on patients’ use of clinic notes through a patient portal has not been evaluated for improving diabetes. We hypothesize that incorporating patient-centered DSMES created via SDM to clinic notes can be a meaningful intervention to assist older people with diabetes to achieve their diabetes care goals. Therefore, we are developing an educational decision aid named SEE-Diabetes (Support-Engage-Empower-Diabetes) (Figure 1). SEE-Diabetes design supports patients and providers in SDM by organizing knowledge and information of ADCES7 principles presented at appropriate times during the clinical course to promote better health. As we developed the SEE-Diabetes, we considered user-centered design (UCD) methods with four main phases: understand the context of use, specify user requirements, design solutions, and evaluate against requirements[34]. In this study, we conducted a survey and focus groups to identify the context of use and user requirement.

Figure 1.

Overview of our proposed SEE-Diabetes to be integrated in EHR clinic note for diabetes visit

The objective of this study was to assess the SEE-Diabetes information needs of people with diabetes aged 65 and older. We conducted an online survey to determine the prevalence of patient portal usage and reading clinic notes among people with diabetes. We also compared the differences between the younger group (age <65 years old) and the older group (study group, age >65 years old). We conducted focus groups to explore patients’ experience of reading clinic notes derived from a real-life scenario. We accumulated opinions that would help to improve the SEE-Diabetes educational aid. The ultimate goal of this study is to implement SEE-Diabetes in clinic notes and provide patient-centered education for older people with diabetes following ADCES7 guidelines. We concurrently collected information needs of both patients with diabetes and providers who have experience managing diabetes. This present study reports the information needs of patients. Information needs of providers will be reported in a separate publication.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

In this mix-methods study, we have formed an interdisciplinary research team with a diversity of expertise, including informatics (P.N., M.K., S.B., E.J.S.), endocrinology (U.K.), primary care (P.N., M.D.), and diabetes education (S.B.). We conducted a combination of an online survey and focus groups to evaluate the clinic notes for people with diabetes and identified the needs of ADCES7 principles. This study was approved by the University of Missouri Healthcare Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Study Setting

The University of Missouri Health Care is an academic medical center with 640 beds in hospital and outpatient clinics providing primary care and specialty care in Missouri, the United States[35]. The University of Missouri Health Care has connected patient information across multiple hospitals and clinics through Cerner’s EHR using PowerChart[36]. Patients can access their medical records and download their clinic notes via a patient portal, HEALTHConnect[37]. The University of Missouri Health Care has PowerInsight[38], a Cerner's operational reporting platform, for reporting, querying, and aggregating data, which can be used for research purposes. In this study, we used PowerInsight to include diabetes patients and PowerChart EHR to select clinic notes.

2.3. Clinic Note Selection

We included patients aged 65 years and older with type 2 diabetes who presented for diabetes management between 2017 and 2018. Patients who had at least two clinic notes of follow-up for diabetes were included. We selected three different clinic notes and de-identified them to present to the study participants. (Figure 2). We extracted the “Assessment and Plan” section from clinic notes because we wanted to focus on the care plan documented at the clinic visit. The Assessment and Plan section is noted for structuring each problem with a separate plan of an individual patient[39]. Each clinic note was copied into Microsoft Word to evaluate Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level,[40] the most widely used to access readability formula of written health care information materials[41].

Figure 2. Participants’ opinions for each randomly de-identified clinic note of people with diabetes.

We asked participants to review each clinic note and answered questions: Q1) Is the clinic note easy to read and why or why not? and Q2) Is this note helpful for people with diabetes? The table shows the readability and the number of participants who agreed and disagreed with two questions for each clinic note.

Clinic note 1 was from a 73-year-old female with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, systolic congestive heart failure, and anemia. Word count of Clinic note 1 was 48 words, and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level was 6.9. Clinic note 2 was from a male with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and dyslipidemia. Word count of Clinic note 2 was 117 words, and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level was 9.4. Clinic note 3 was from a 74-year-old male with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. His diabetes duration was approximately 49 years. Word count of Clinic note 3 was 239 words, and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level was 9.6.

2.4. Survey Development

The survey was designed to gather information about participants’ characteristics and their accessibility to their clinic notes. The specialty of the participants’ providers was also noted. Participant characteristics included age (years), gender, race, education, diabetes duration (years), and insulin prescription (yes/no). The medical chart accessibility consisted of three questions: Q1) Do you access your medical chart using the patient portal? Q2) If yes, how do you access your medical chart? Q3) Have you ever read a clinic note in your chart? At the end of the survey, we invited participants to join focus group sessions.

2.5. Focus Group Questionnaire Development

Our research team designed five open-ended questions for focus groups. The first two questions gathered information regarding the clinic notes and were asked after participants read each clinic note (Figure 2). Q1) Is the clinic note easy to read, and why or why not? Q2) Is this note helpful for people with diabetes? The next two questions invited the participants to offer an opinion regarding “who” and “when” should DSMEs be delivered. Q3) Who do you think should discuss the DSMES principles with you? Q4) When would be the best time to discuss the DSMES principles? The last question sought the participants’ input regarding SEE-Diabetes in the clinic note. Q5) How can we improve SEE-Diabetes? Before asking the last question, we demonstrated our proposed SEE-Diabetes to participants by providing a persona scenario and an interactive discussion. Our persona was 71 years old female with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes who visited for six months follow-up. Her average blood sugar ranged from 140 to 150 mg/dL. Our goal was to apply the SEE-diabetes under the “Patient Education” section to provide individualized diabetes education following ADCES7 guidelines.

2.6. Data Collection and Analysis

First, 82 people with diabetes in all age groups were invited to participate in the survey from specialty care at the Cosmopolitan International Diabetes and Endocrinology Center and primary care clinics at multiple locations of the University of Missouri Health Care in April and May 2021. The 37 participants or caregivers of participants who accepted to join the research received a link to an online survey via email. Survey data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at the University of Missouri. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform developed by Vanderbilt University to support data capture for clinical research[42,43]. Second, we included all people with diabetes aged 65 and older for focus groups who accepted the invitation through the survey. Based on Kitzinger’s recommendation, the number of invited participants in each group was between four and eight participants[44]. Third, considering participants’ safety due to the COVID-19 pandemic, focus groups were conducted and recorded via Zoom[45] in April and May 2021. Participants were asked to evaluate the Assessment and Plan section of three randomly selected deidentified representative clinic notes of people with diabetes (Figure 2). Each focus group was facilitated by S.B., who has experience with focus group facilitation. The assistants (P.N., M.K., U.K.), on the other hand, took comprehensive notes, operated the Zoom recorder, and prepared for unexpected interruptions. In addition, the assistants noted the participants' body language throughout the discussion. Each focus group lasted approximately one hour. Lastly, descriptive statistics were performed to analyze participants’ characteristics and the medical chart accessibility. S.B. and P.N. transcribed the focus groups recording and analyzed qualitative data using thematic analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Survey

A total of 37 participants responded to the survey (response rate 45%). (Table 1) Most of the participants’ providers were from diabetes specialty care (31, 84%). The average age of participants in both age groups was 66 years old and ranged from 24 to 82 years old. Thirteen participants were aged less than 65 years old (M=53.5, SD=10.5), and 24 participants were aged 65 and older (M=72.3, SD=4.6). There were 15 males (40%) and 22 females (60%). Most participants were white (35, 95%), and all were non-Hispanic (37, 100%). The participants’ education levels were less than high school diploma (2, 5%), high school graduate, diploma, or the equivalent (10, 27%), some college credit, no degree (10, 27%), trade/technical/vocational training (3, 8%), associate degree (2, 5%), bachelor's degree (2, 5%), and higher than bachelor's degree (8, 22%). The average diabetes duration was 21 years, and 68% (N=25) were prescribed insulin. Twenty-eight participants (76%) accessed their medical records using the patient portal through a computer (18, 64%) and mobile devices (17, 61%). Most participants (29, 78%) have read clinical notes in their medical records.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants’ survey (N=37)

| Total | < 65 years | ≥65 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Participants’ provider specialty | ||||||

| Primary Care | 6 | 16.2 | 2 | 15.4 | 4 | 16.7 |

| Diabetes Specialty Care | 31 | 83.8 | 11 | 84.6 | 20 | 83.3 |

| Age | 65.7±11.5 (24.0-82.0) | 53.5±10.5 (24.0-63.0) | 72.3±4.6 (65.0-82.0) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 15 | 40.5 | 5 | 38.5 | 10 | 41.7 |

| Female | 22 | 59.5 | 8 | 61.5 | 14 | 58.3 |

| Hispanic or Latino | ||||||

| No | 37 | 100.0 | 13 | 100.0 | 24 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 35 | 94.6 | 12 | 92.3 | 23 | 95.8 |

| Asian | 1 | 2.7 | 1 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Black or African | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.2 |

| American | ||||||

| American Indian/ Alaska | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Native | ||||||

| Do not wish to report | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pacific Islander | ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school diploma | 2 | 5.4 | 1 | 7.7 | 1 | 4.2 |

| High school graduate, diploma or the equivalent (e.g. GED) | 10 | 27.0 | 2 | 15.4 | 8 | 33.3 |

| Some college credit, no degree | 10 | 27.0 | 5 | 38.5 | 5 | 20.8 |

| Trade/technical/vocational training | 3 | 8.1 | 1 | 7.7 | 2 | 8.3 |

| Associate degree | 2 | 5.4 | 2 | 15.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Bachelor's degree | 2 | 5.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 8.3 |

| Higher than Bachelor's degree | 8 | 21.6 | 2 | 15.4 | 6 | 25.0 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 20.9±15.0 (1-63.0) | 17.2±11.7 (1-37.0) | 22.9±16.4(37-63) | |||

| Are you taking insulin for diabetes? | ||||||

| No | 12 | 32.4 | 9 | 69.2 | 16 | 66.7 |

| Yes | 25 | 67.6 | 4 | 30.8 | 7 | 33.3 |

| Do you access your medical chart using the patient portal? | ||||||

| No | 9 | 24.3 | 3 | 23.1 | 6 | 25.0 |

| Yes | 28 | 75.7 | 10 | 76.9 | 18 | 75.0 |

| How do you access your medical chart? | ||||||

| Patient portal in computer (e.g., desktop, laptop) | 18 | 64.3 | 7 | 70.0 | 11 | 61.1 |

| Patient portal in mobile device (e.g., smartphone, tablet) | 17 | 60.7 | 6 | 60.0 | 13 | 72.2 |

| Have you ever read a clinic note in your chart? | ||||||

| No | 8 | 21.6 | 3 | 23.1 | 5 | 20.8 |

| Yes | 29 | 78.4 | 10 | 76.9 | 19 | 79.2 |

When compared between the younger group (N=13) and older group (N=24), we found that there were 10 participants (77%) aged less than 65 who accessed their medical records using the patient portal through a computer (7, 70%) and mobile devices (6, 60%). There were 18 participants (75%) aged 65 and older accessing their medical records through the patient portal via a computer (11, 61%) and mobile devices (13, 72%). Over three quarters have read their clinic notes in both the younger group (10, 77%) and the older group (19, 79%).

3.2. Focus Groups

3.2.1. Participants Characteristics

There were 17 participants aged 65 and older that agreed to join the focus group. Of these 17 participants, 9 ultimately completed participation in our focus groups. There were five males (56%). The average age of participants was 74 years old and ranged from 68 to 82 years old. The average diabetes duration was 33 years and ranged from 13 to 63 years. Eight participants followed up with a specialist (89%), and one followed up with a primary care physician (11%).

3.2.2. Theme 1: Readability of Clinic Notes

After participants reviewed each clinic note, we asked, “Is the clinic note easy to read and why or why not?”. For Clinic note 1 (Word count=48, Flesch-Kincaid=6.9), there were 11 statements from the conversation, and most participants agreed that it was easy to read. For Clinic note 2 (Word count=117, Flesch-Kincaid=9.4), there were 12 statements, and five participants mentioned it was easy to read. For Clinic note 3 (Word count=239, Flesch-Kincaid=9.6), there were eight statements, and all eight participants agreed that it was easy to read (Figure 2).

Participants shared clinic notes were easy to read because clinic notes used concise information, reminders of what had been discussed during the visit, as a plan of treatment, and clearly written in English. Participants also perceived that clinic notes were not easy to read because clinic notes used too many technical terms, abbreviations, and poorly written sentences (Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of participants’ statements on “Readability” of clinic notes

| Clinic note | Easy to read | Not easy to read |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “I think it's easy to read because it's very concise and it points out the very valuable points that we need to be made to consider, too. In the process of controlling our disease.” - Male, 82 years old, duration of diabetes 27 years | “MMSE is not clear to me. So this note's not easy to read for me, but the patient probably would know that.” - Male, 70 years old, diabetes duration 35 years |

| 2 | “It's easier for me because sometimes when you do your notes, I have to look to see what I need to change or what your advice is for the particular areas.” - Female, 69 years old, duration of diabetes 63 years | “I think I get lost in there. There’re too many technical terms that are that I'm not familiar with. And I thought I had read a lot of notes regarding diabetes. But this one is confusing for me.” - Male, 82 years old, duration of diabetes 27 years |

| “The language is going to be comparable with or kinda full of understanding. So, no, I think it must be brought down to maybe eight - nine grade level.” - Male, 82 years old, duration of diabetes 27 years | ||

| “Some of the coding on there is not understandable. And that's very important to know about. So if there's some way to state that in more everyday language for us and maybe the PPSV23 utd could be in parentheses after the explanation.” - Male, 76 years old, duration of diabetes 52 years | ||

| 3 | “I like that kind of advice because it looks very simple. If I was this patient, I would know exactly what I was supposed to continue to do, which is very concise. And one of the things that I had never, never done is carry glucose tablets with. Because I so seldom had a sugar low. Mine is that the other around sugar highs. And it's easy to see all the range from a sugar low to a sugar high. I like this. I think it's easy to read.” - Female, 79 years old, duration of diabetes 15 years | |

| “I think what I like the use of complete sentences and capitalizations. So for me, this is a little easier to read.” - Male, 76 years old, duration of diabetes 52 years |

3.2.3. Theme 2: Helpfulness of Clinic Notes for Diabetes Care

After participants reviewed each clinic note, the second question was asked, “Is this note helpful for people with diabetes?”. For Clinic note 1, there were 11 statements, and four participants agreed that it was helpful for people with diabetes. For Clinic note 2, there were eight statements. Five participants mentioned it was helpful for people with diabetes, and three participants mentioned it was not helpful for people with diabetes. For Clinic note 3, there were eight statements, and all eight participants agreed that it was helpful for their diabetes care (Figure 2).

Participants shared clinic notes were helpful because clinic notes were easy to understand, precise, written in a good format, and provided detailed information. On the other hand, participants shared clinic notes were not helpful because clinic notes did not provide enough medication information, used too many abbreviations, and were not well written in English (Table 3).

Table 3.

Examples of participants’ statements on “Helpfulness” about reading clinic notes

| Clinic note | Helpful | Not helpful |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “When reading these notes, perhaps it is a wakeup call. And when they are reading not control, perhaps what will motivate them to pay a little closer attention to their problems?” - Female, 79 years old, duration of diabetes 15 years | |

| 2 | “Yeah, it's helpful for me. I like this format.” - Female, 69 years old, duration of diabetes 63 years | “Not for me. I understand metformin. Not XR. There are a lot of abbreviations” - Male, 68 years old, diabetes duration 13 years |

| “As I read it the second time, I am able to understand it better because the first time I was coming upon that, I was. Ahh I just knew briefly, but now I can understand the context better. It is pretty you have to know a lot to read these and understand. So I would like for it to be simpler. But I do think they’re great.” - Female, 79 years old, duration of diabetes 15 years | ||

| 3 | “Yeah, I would say yes. Well, I'm looking at how many diagnoses or problems they have with diabetes and the dyslipidemia and the hypertension, I'm just saying, even if there's 10 of them by separating them, it makes it easier for the patient to figure out what to do about that.” - Female, 69 years old, duration of diabetes 63 years |

3.2.4. Suggestions for Improving SEE-Diabetes

After we completed the clinic note evaluation, we asked participants two questions, “Who do you think should discuss the DSMES principles with you?” and “When would be the best time to discuss the DSMES principles?”. Most participants wanted to discuss DSMES principles with providers (n=7), followed by diabetes educators (n=4), peer diabetes patients (n=3), family (n=1), and friends (n=1). The best time to discuss DSMES principles could be before (n=1), during (n=3), or after the visit (n=1). For instance, some participants stated as follows:

“In my case, I had diabetes for a long, long time, and I find that during the visit is probably the most appropriate time for me to gain further education, but possibly after the visit also could be another possibility.”

(Male, 82 years old, duration of diabetes 27 years)

“Well, while we're waiting for the doctor to come in. How about a handout that has some brief notes on it relative to the seven principles? Lay those right out on the table in there. So maybe just a piece of paper with some of these notes on there that are pretty hard to avoid picking up and reading when you go in there. That might be at least one way to get these reminders to the patient.”

(Male, 70 years old, duration of diabetes 35 years)

We demonstrated our proposed SEE-Diabetes to participants and asked their opinions for improvement. Participants suggested that SEE-Diabetes should provide concise information (n=2), use motivational words (n=2), use guiding words (n=1), provide external resources such as support groups (n=1), and add a patient education section (n=1). For instance, some participants stated as follows:

“I think that concise information that can be Take-Home for the patient would be very helpful.”

(Male, 82 years old, duration of diabetes 27 years)

“Motivation is something. Instead of saying, know your mood, you might state it as a question. You might say something. Have your moods been off? Have you been feeling blue or at times kind of really high? Here's something that might help.”

(Male, 76 years old, duration of diabetes 52 years)

4. Discussion

The quantitative and qualitative data we collected from older people with diabetes revealed that they did read their clinic notes (78%) and used a patient portal to access their medical records (76%) on either a computer (61%) or mobile devices (72%). The majority of participants indicated that the clinic note is helpful for people with diabetes. Our results were consistent with the study of Masys et al.[46], who developed a Patient-Centered Access to Secure Systems Online (PCASSO) to communicate clinic information via the internet. The study showed that 61% of patients were interested in the system, and 23% logged in at least five times. Most patients rated the overall value of having their records available online as very valuable. Our results also reflect the trend that 54.2 million Americans and Canadians were able to access their clinic notes based on the survey from 266 health systems in 2020[47]. Moreover, the National Poll on Healthy Aging surveyed older adults aged 50-80 years about patient portals in 2018. Half of older adults have set up their patient portals, and the most reason for usage was viewing their test results[48]. These findings indicated that patients are interested in their medical records. When providers write clinic notes, providers should keep in mind that the audience of clinic notes is not limited to health care providers anymore but includes patients who read their clinic notes.

The results from our survey show that three-quarters of participants, aged less than 65 and participants aged 65 and older, access their clinic notes via the patient portal. We did find a difference in the choice of devices used for access by the two groups. The younger group used a computer (70%) more than mobile devices (60%); on the other hand, the older group used mobile devices (72%) more than a computer (61%). The reason the older group used a computer less than the younger group could be technology barriers[49,50]. Linkage Technology Survey reported that 80% of older adults owned smartphones, and 69% of participants had personal computers[51]. Some studies mentioned that older adults preferred mobile devices more than computers because the size of devices was more appealing, and touching the screen was quicker than using a mouse and keyboard[52]. Some suggested that mobile devices have more functions than computers, such as navigation, photographing, and surfing the internet[53]. In addition, our study suggested older patients were motivated to read clinic notes via the patient portal for diabetes care compared to the younger group.

In the focus group study, after participants reviewed the clinic notes, we found the Flesh-Kincaid Grade Level or the number of words in each clinic note could not represent how easy to read or not the clinic notes were. Clinic note 3 had the highest Flesh-Kincaid Grade Level and word count; however, all participants agreed that it was easy to read. The possible reason could be because of the diabetes duration of participants. The average diabetes duration in focus groups was 33 years and ranged from 13 to 63 years. Participants may be familiar with medical terms related to diabetes. Participants also suggested clinic notes should use fewer abbreviations or technical terms. They also preferred that the plan be written in complete English sentences. Klein et al.’s study[54] suggested clinic notes be “clear and succinct” to be shared in clinical practice. They emphasized the use of plain and straightforward language with minimal medical jargon to reduce confusion for patients. Participants in our focus groups also suggested clinic notes should provide concise information and use motivational words. Concise information helps improve readability and speeds up documentation.[54] Using motivational words helps encourage and empower positive change as a positive care effect[55,56].

Regarding the helpfulness of clinic notes for diabetes care, most participants agreed all three clinic notes were helpful. Half of the participants’ statements mentioned Clinic note 2 was not easy to read; however, most participants still rated that Clinic note 2 was helpful. The results indicated that participants recognized the helpfulness of clinic notes. DesRoches et al.’s study[18] conducted a survey with patients aged 65 and older who used a patient portal. The study showed 80% of survey participants had read their clinic notes for a year or more. Specifically, patients who had two or more chronic diseases read at least four clinic notes. The study suggested reading clinic notes not just helped them feel in control of their health care but also significantly enhanced communication between physicians and older patients about health problems[57].

For the future direction of research streams, SEE-Diabetes will be developed for shared decision making between patients and providers. In this study, we determined the information needs of SEE-Diabetes from people with diabetes aged 65 and older. We are also conducting a parallel study to determine the information needs from providers’ perspectives. DSMES statements in SEE-Diabetes will reflect suggestions from both patients and providers.

Our SEE-Diabetes educational aid has several strengths. First, SEE-Diabetes provides tailored DSMES options based on SDM. Patient and provider can make a mutual decision on individual self-care behavior items from ADCES7 that matter most to the patient. Second, SEE-Diabetes will be aligned with the provider workflow without additional workload because DSMES discussion is part of clinic visits. Third, SEE-Diabetes will be written at a sixth-grade reading level to achieve clear and succinct language following NIH guidelines[58-60]. We believe SEE-Diabetes will guide a health care team to provide an effective person-centered collaboration and goal setting to improve health outcomes and quality of life.

Our study has several limitations. First, because all participants were non-Hispanic, and most of them were white, findings may not be extrapolated for minority populations. It is a typical characteristic because the majority of the Midwest population are non-Hispanic and white[61]. We plan to include more diverse groups of participants when we design and evaluate SEE-Diabetes. Second, we conducted an online survey and focus groups via Zoom, which may have led to selection bias. Participants without internet access or not familiar with technology probably use the patient portal rarely or would not want to participate in our study. However, we aimed to identify the SEE-Diabetes information needs, which will be implemented in the patient portal. Thus, our results can represent the population who have access to and more frequently use the patient portal and medical charts via the internet. Third, our numbers of participants were small and less than recommended for qualitative research [44]. However, our findings showed that our study had data saturation[62]. Thus, we decided to discontinue recruiting more participants after the third focus group.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated the accessibility and readability of information needs of developing patient-centered DSMES, namely SEE-Diabetes, in an EHR for people with diabetes aged 65 and older. The study noted most participants were able to access the patient portal and had read their clinic notes. Before creating clinic notes, providers should consider that clinic notes will be used to communicate not only with other providers but also with patients. We found that the readability of clinic notes was the main concern and related to the helpfulness of clinic notes. Our findings provide an opportunity for improving the effectiveness of our proposed SEE-Diabetes educational aid. For the next stages of the SEE-Diabetes project, we will iteratively evaluate the readability and usability of our SEE-Diabetes prototype.

Highlights.

Follow-up clinic notes lacked patient-centered education for diabetes patients.

Almost 80% of participants read their clinic notes and used patient portals.

Readability was concerned because of medical abbreviations and poor formatting.

Most participants recognized the helpfulness of clinic notes.

Clinic notes should be written at the sixth-grade reading level.

Funding statement

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders (NIDDK) P30DK092950 from Center for Diabetes Translation Research (CDTR) Pilot & Feasibility (P&F) program grant and University of Missouri Research Council grant URC-19-153 were available when this project was conducted.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Reference

- [1].National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States., (2020) 32. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Challenges in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes in the Elderly, (2011). https://www.touchendocrinology.com/diabetes/journal-articles/challenges-in-the-management-of-type-2-diabetes-in-the-elderly/ (accessed September 15, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sinclair A, Dunning T, Rodriguez-Mañas L, Diabetes in older people: new insights and remaining challenges, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 3 (2015) 275–285. 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sinclair AJ, Abdelhafiz AH, Challenges and Strategies for Diabetes Management in Community-Living Older Adults, Diabetes Spectr. 33 (2020) 217–227. 10.2337/ds20-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].A.D. Association, 12. Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020, Diabetes Care. 43 (2020) S152–S162. 10.2337/dc20-S012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Davis J, Fischl AH, Beck J, Browning L, Carter A, Condon JE, Dennison M, Francis T, Hughes PJ, Jaime S, Lau KHK, McArthur T, McAvoy K, Magee M, Newby O, Ponder SW, Quraishi U, Rawlings K, Socke J, Stancil M, Uelmen S, Villalobos S, 2022 National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support, Sci. Diabetes Self-Manag. Care. (2022) 26350106211072204. 10.1177/26350106211072203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Strawbridge LM, Lloyd JT, Meadow A, Riley GF, Howell BL, One-Year Outcomes of Diabetes Self-Management Training Among Medicare Beneficiaries Newly Diagnosed With Diabetes, Med. Care. 55 (2017) 391–397. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].He X, Li J, Wang B, Yao Q, Li L, Song R, Shi X, Zhang J, Diabetes self-management education reduces risk of all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Endocrine. 55 (2017) 712–731. 10.1007/s12020-016-1168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD, Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of the effect on glycemic control, Patient Educ. Couns. 99 (2016) 926–943. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cooke D, Bond R, Lawton J, Rankin D, Heller S, Clark M, Speight J, for the UK NIHR DAFNE Study Group, Structured Type 1 Diabetes Education Delivered Within Routine Care: Impact on glycemic control and diabetes-specific quality of life, Diabetes Care. 36 (2013) 270–272. 10.2337/dc12-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Duncan I, Ahmed T, (Emily) Li Q, Stetson B, L. Ruggiero, Burton K, Rosenthal D, Fitzner K, Assessing the Value of the Diabetes Educator, Diabetes Educ. 37 (2011) 638–657. 10.1177/0145721711416256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pillay J, Armstrong MJ, Butalia S, Donovan LE, Sigal RJ, Vandermeer B, Chordiya P, Dhakal S, Hartling L, Nuspl M, Featherstone R, Dryden DM, Behavioral Programs for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis, Ann. Intern. Med 163 (2015) 848. 10.7326/M15-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pillay J, Armstrong MJ, Butalia S, Donovan LE, Sigal RJ, Chordiya P, Dhakal S, Vandermeer B, Hartling L, Nuspl M, Featherstone R, Dryden DM, Behavioral Programs for Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Ann. Intern. Med 163 (2015) 836. 10.7326/M15-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Powers MA, Bardsley JK, Cypress M, Funnell MM, Harms D, Hess-Fischl A, Hooks B, Isaacs D, Mandel ED, Maryniuk MD, Norton A, Rinker J, Siminerio LM, Uelmen S, Diabetes Self-management Education and Support in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Consensus Report of the American Diabetes Association, the Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of PAs, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, and the American Pharmacists Association, Diabetes Care. 43 (2020) 1636–1649. 10.2337/dci20-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Strawbridge LM, Lloyd JT, Meadow A, Riley GF, Howell BL, Use of Medicare’s Diabetes Self-Management Training Benefit, Health Educ. Behav. Off. Publ. Soc. Public Health Educ. 42 (2015) 530–538. 10.1177/1090198114566271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kolb L, An Effective Model of Diabetes Care and Education: The ADCES7 Self-Care Behaviors™, Sci. Diabetes Self-Manag. Care. 47 (2021) 30–53. 10.1177/0145721720978154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vogel L, OpenNotes Project “levels the playing field” between doctors and patients, CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J 182 (2010) 1497–1498. 10.1503/cmaj.109-3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].DesRoches CM, Salmi L, Dong Z, Blease C, How do older patients with chronic conditions view reading open visit notes?, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. (2021). 10.1111/jgs.17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program, (2020). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/05/01/2020-07419/21st-century-cures-act-interoperability-information-blocking-and-the-onc-health-it-certification (accessed January 26, 2022).

- [20].Bonamici S, Text - H.R.34 - 114th Congress (2015-2016): 21st Century Cures Act, (2016). https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/34/text (accessed September 1, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ye Q, Patel R, Khan U, Boren SA, Kim MS, Evaluation of Provider Documentation Patterns as a Tool to Deliver Ongoing Patient-Centered Diabetes Education and Support, Int. J. Clin. Pract 74 (2020) e13451. 10.1111/ijcp.13451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shared Decision Making, (2013). www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/nlc_shared_decision_making_fact_sheet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mitchell TO, Goldenberg MN, When Doctor Means Teacher: An Interactive Workshop on Patient-Centered Education, MedEdPORTAL J. Teach. Learn. Resour 16 (2020) 11053. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Siddharthan T, Rabin T, Canavan ME, Nassali F, Kirchhoff P, Kalyesubula R, Coca S, Rastegar A, Knauf F, Implementation of Patient-Centered Education for Chronic-Disease Management in Uganda: An Effectiveness Study, PLoS ONE. 11 (2016) e0166411. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ong LML, de Haes JCJM, Hoos AM, Lammes FB, Doctor-patient communication: A review of the literature, Soc. Sci. Med 40 (1995) 903–918. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shay LA, Lafata JE, Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes, Med. Decis. Mak. Int. J. Soc. Med. Decis. Mak 35 (2015) 114–131. 10.1177/0272989X14551638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Walker J, Leveille S, Bell S, Chimowitz H, Dong Z, Elmore JG, Fernandez L, Fossa A, Gerard M, Fitzgerald P, Harcourt K, Jackson S, Payne TH, Perez J, Shucard H, Stametz R, DesRoches C, Delbanco T, OpenNotes After 7 Years: Patient Experiences With Ongoing Access to Their Clinicians’ Outpatient Visit Notes, J. Med. Internet Res. 21 (2019) e13876. 10.2196/13876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fossa AJ, Bell SK, DesRoches C, OpenNotes and shared decision making: a growing practice in clinical transparency and how it can support patient-centered care, J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA. 25 (2018) 1153–1159. 10.1093/jamia/ocy083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Leveille SG, Walker J, Ralston JD, Ross SE, Elmore JG, Delbanco T, Evaluating the impact of patients’ online access to doctors’ visit notes: designing and executing the OpenNotes project, BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak 12 (2012) 32. 10.1186/1472-6947-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shay LA, Lafata JE, Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes, Med. Decis. Mak. Int. J. Soc. Med. Decis. Mak 35 (2015) 114–131. 10.1177/0272989X14551638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fisher HM, McCabe S, Managing Chronic Conditions for Elderly Adults: The VNS CHOICE Model, Health Care Financ. Rev. 27 (2005) 33–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy, (2006). https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2006483 (accessed September 22, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chesser AK, Woods NK, Smothers K, Rogers N, Health Literacy and Older Adults: A Systematic Review, Gerontol. Geriatr. Med 2 (2016). 10.1177/2333721416630492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].What is User Centered Design?, Interact. Des. Found, (n.d.). https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/user-centered-design (accessed October 20, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [35].Facts/Figures, (n.d.). https://www.muhealth.org/for-media/resources/factsfigures (accessed September 8, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [36].PowerChart Touch solution ∣ Cerner, (n.d.). https://www.cerner.com/solutions/powerchart-touch (accessed October 27, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [37].Your MU Health Care, (n.d.). https://www.muhealth.org/patient-login (accessed October 27, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [38].Healthcare Analytics with Cerner: Part 1 - Data Acquisition, Hi I’m Boris Tyukin. (2016). http://boristyukin.com/healthcare-analytics-with-cerner-part-l-data-acquisition/ (accessed October 27, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [39].UC San Diego’s Practical Guide to Clinical Medicine, (n.d.). https://meded.ucsd.edu/clinicalmed/clinic.html (accessed October 25, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP Jr, Rogers RL, Chissom BS, Derivation Of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count And Flesch Reading Ease Formula) For Navy Enlisted Personnel, Institute for Simulation and Training, Millington (Tenn.), 1975. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/istlibrary/56 (accessed October 25, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wang L-W, Miller MJ, Schmitt MR, Wen FK, Assessing readability formula differences with written health information materials: application, results, and recommendations, Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. RSAP 9 (2013) 503–516. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN, The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners, J. Biomed. Inform 95 (2019) 103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG, Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support, J. Biomed. Inform 42 (2009) 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kitzinger J, Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups., BMJ. 311 (1995) 299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zoom Video Conferencing - University of Missouri System, (n.d.). https://umsystem.zoom.us/ (accessed November 4, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [46].Masys D, Baker D, Butros A, Cowles KE, Giving patients access to their medical records via the internet: the PCASSO experience, J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA. 9 (2002) 181–191. 10.1197/jamia.m1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].New survey data reveals 54 million people are able to access clinicians’ visit notes online, (n.d.). https://www.opennotes.org/news/new-survey-data-reveals-54-million-people-are-able-to-access-clinicians-visit-notes-online/ (accessed September 29, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [48].Logging in: Using Patient Portals to Access Health Information, Natl. Poll Healthy Aging, (n.d.). https://www.healthyagingpoll.org/reports-more/report/logging-using-patient-portals-access-health-information (accessed November 30, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [49].Patient Portals: Improving The Health Of Older Adults By Increasing Use And Access ∣ Health Affairs Blog, (n.d.). https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180830.888175/full/ (accessed September 29, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tieu L, Sarkar U, Schillinger D, Ralston JD, Ratanawongsa N, Pasick R, Lyles CR, Barriers and Facilitators to Online Portal Use Among Patients and Caregivers in a Safety Net Health Care System: A Qualitative Study, J. Med. Internet Res. 17 (2015) e4847. 10.2196/jmir.4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].2019 Technology Survey Older Adults Age 55-100, Linkage Connect, 2019. https://www.linkageconnect.com/wp-content/uploads/2019-Link-age-Connect-Technology-Study-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kuerbis A, Mulliken A, Muench F, Moore AA, Gardner D, Older adults and mobile technology: Factors that enhance and inhibit utilization in the context of behavioral health, Ment. Health Addict. Res. 2 (2017). 10.15761/MHAR.1000136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pan J, Bryan-Kinns N, Dong H, Mobile Technology Adoption Among Older People - An Exploratory Study in the UK, in: Zhou J, Salvendy G (Eds.), Hum. Asp. IT Aged Popul. Aging Des. User Exp., Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017: pp. 14–24. 10.1007/978-3-319-58530-7_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Klein JW, Jackson SL, Bell SK, Anselmo MK, Walker J, Delbanco T, Elmore JG, Your Patient Is Now Reading Your Note: Opportunities, Problems, and Prospects, Am. J. Med 129 (2016) 1018–1021. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bensing JM, Verheul W, The silent healer: the role of communication in placebo effects, Patient Educ. Couns 80 (2010) 293–299. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Blease C, The principle of parity: the “placebo effect” and physician communication, J. Med. Ethics 38 (2012) 199–203. 10.1136/medethics-2011-100177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bronson DL, Costanza MC, Tufo HM, Using medical records for older patient education in ambulatory practice, Med. Care 24 (1986) 332–339. 10.1097/00005650-198604000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Cotugna N, Vickery CE, Carpenter-Haefele KM, Evaluation of literacy level of patient education pages in health-related journals, J. Community Health. 30 (2005) 213–219. 10.1007/s10900-004-1959-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Weiss BD, Health Literacy and Patient Safety: Help Patients Understand, (2007). https://pogoe.org/sites/default/files/Health%20Literacy%20-%202016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Weiss BD, Coyne C, Communicating with Patients Who Cannot Read, N. Engl. J. Med. 337 (1997) 272–274. 10.1056/NEJM199707243370411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Census profile: Midwest Region, Census Report, (n.d.). http://censusreporter.org/profiles/02000US2-midwest-region/ (accessed October 3, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- [62].Saturation in Qualitative Research, in: SAGE Res. Methods Found., SAGE Publications Ltd, 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y ISP United Kingdom, 2020. 10.4135/9781526421036822322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]