Abstract

Analogues of N,N-dimethyladenine exploiting both thieno-and isothiazolo-pyrimidine cores were modified with 3-subsituted azetidines to yield visibly emissive and responsive fluorophores. The emission quantum yields, among the highest seen for purine analogues (0.64 and 0.77 in water and dioxane respectively), correlated with the Hammett inductive constants of the substituents on the azetidine ring. Ribosylation of the difluoroazetidino-modified nucleobase yielded an emissive nucleoside that displayed a substantially lower emission quantum yield in water, compared to the precursor nucleobase. Importantly, high emission quantum yield was restored in deuterium oxide, which highlights the potential impact of the sugar moiety on the photophysical features of fluorescent nucleosides, a functionality usually considered non-chromophoric and photophysically benign.

Keywords: fluorescence, nucleosides, RNA, modified nucleosides, heterocycles

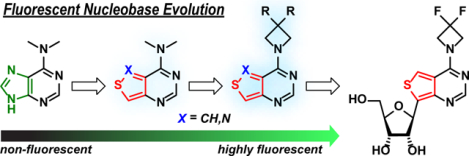

Graphical Abstract

Analogues of N,N-dimethyladenine exploiting both thieno-and isothiazolo-pyrimidine cores were modified with 3-subsituted azetidines to yield visibly emissive and responsive fluorophores. Ribosylation of the difluoroazetidino-modified nucleobase yielded an emissive nucleoside that displayed a substantially lower emission quantum yield in water, compared to the precursor nucleobase. The impact of the sugar moiety on the photophysical features of fluorescent nucleosides, a functionality usually considered non-chromophoric and photophysically benign, was analyzed.

Introduction

Adenosine (A), Uridine (U), Guanosine (G), and Cytidine (C) encompass the four ribonucleosides found in RNA, and in conjunction with their 2’-deoxy counterparts, comprise some of the most significant building blocks in living organisms through their key roles in storing and expressing the genetic code, as well as in mediating inter- and intramolecular signaling events. The additional structural complexity seen within modified nucleosides, especially in various forms of RNA and secondary messengers, points to highly expanded roles in all domains of life. These structural modifications are similarly implicated in human health, where the anomalous absence or presence of certain RNA modifications can lead to a myriad of human health disorders.[1] Currently, over 143 modified ribonucleosides are known, yet the presence and functional implications of many analogues remains undetermined.[2]

Curiously, two modified nucleosides, N6,N6-dimethyladenosine (m6,6A) and N6,N6,2’-O-trimethyladenosine (m6,6Am) possess an adenine nucleobase with a dimethylated exocyclic amine (Figure 1a), abolishing the native Watson-Crick pairing capabilities associated with the parent nucleobase.[2,3] The nucleoside antibiotic puromycin and related derivatives also possess this modification (Figure 1a). m6,6A has also been reported to play an important role in rRNA structure/function4 and inactivation of Dim1, the enzyme responsible for installing this modification during eukaryotic ribosome biosynthesis, is lethal to cells.[5–7] Within prokaryotes, the dimethylation occurs at A1518 and A1519 of the small ribosomal subunit of E. Coli and T. thermophilus, where the steric inference of the dimethyl groups and removal of the hydrogen bond donors weakens the tetraloop of helix 45 leading to decreased errors in translation and lower non-AUG translation initiation.6 Although well studied in the context of rRNA, little is known about the function served in tRNA, as it was also found in the bacteria Mycobacterium bovis.[8] Correspondingly, very little is reported on the rare m6,6Am modification as well, given that it only appears in the extensively modified 5’ cap4 structure in trypanosomatid protozoans. With both rarity and structural diversity at play, a fluorescent, faithful chemical probe could prove useful in uncovering the importance m6,6A and m6,6Am possess in their appropriate biochemical environments.

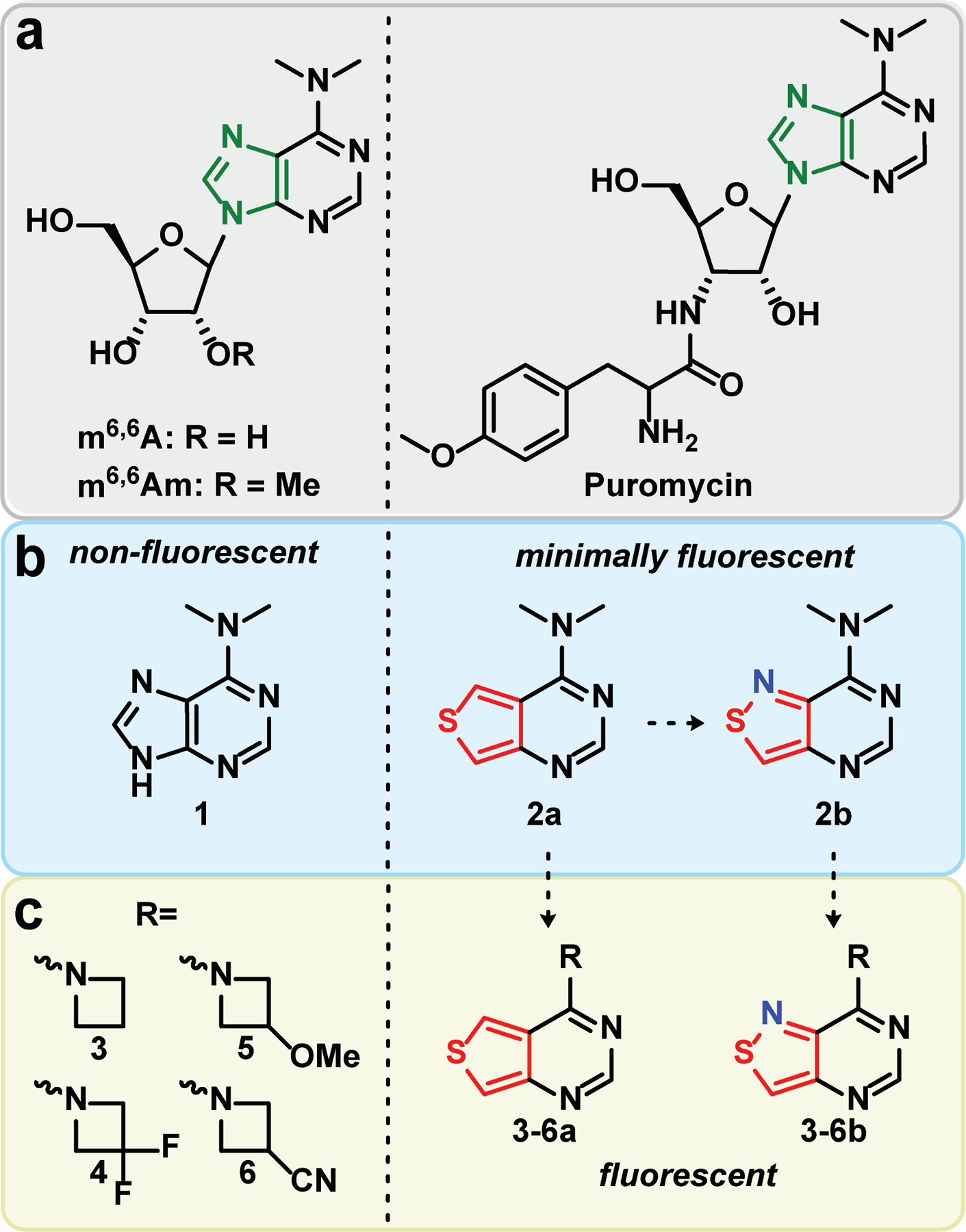

Figure 1.

Structures of (a) N6,N6-dimethyladenosine (m6,6A), N6,N6,2’-O-trimethyladenosine (m6,6Am), and puromycin. (b) Thieno- and isothiazolo- derived purines bearing dimethylamine substituents. (c) Thieno- and isothiazolo- derived purines bearing azetidine and difluoroazetidine substituents.

The native ribonucleosides possess impractical photophysical features with extremely low quantum yields and brightness coefficients.[9] While higher than the canonical nucleosides, m6,6A still suffers from similar deficient photophysical properties as well with low emission quantum yields (<1 % across various solvents).[10,11] Intriguingly, N6,N6-dimethyladenosine was reported by Albinsson to possess dual emission in various solvents with emission maxima at 355 and 568 nm.[10] The red emission band, attributed to the twisted intramolecular charge transfer state (TICT), predominates in aprotic environments but is significantly quenched by protic solvents.[10] In our quest to develop non-perturbing fluorescent nucleosides, we sought to create a small molecule fluorescent analogue of N6,N6-dimethyladenine that remains isomorphic and isofunctional, yet exhibits augmented photophysical properties.

Over the last two decades, we have developed and investigated two emissive RNA alphabets comprising both purine and pyrimidine analogues.[12–14] The first alphabet, derived from a thieno[3,4-d]-pyrimidine heterocyclic nucleus, exhibits markedly improved photophysical properties compared to the native ribonucleosides as evidenced by its employment in the analysis of various biomolecular processes.13 Its limitation is the lack of a nitrogen atom corresponding to the 7 position of the native purine skeleton. To circumvent this, a second generation alphabet based on an isothiazolo[4,3-d]pyrimidine core was synthesized.[12,14] While the restoration of the nitrogen atom into the Hoogsteen face resulted in lower emission quantum yields, the higher degree of isofunctionality facilitated a near-identical behavior of the fluorescent probes compared to the thieno alphabet when studying N7-dependent processes.[12,14–18] With these fluorescent nucleosides at our disposal, we opted to synthesize and explore the photophysical properties of N6,N6-dimethyladenine derivatives adopting both thieno- and isothiazolo-pyrimidines in place of the imidazole ring of the native purine (2a and 2b, Figure 1b,c), and assess their potential for generating emissive nucleoside analogs.

Similarly to the impact of dimethylation on the photophysics of native adenosine,[10,11] we observed elevated emission quantum yields for the dimethylated derivatives of the corresponding thieno- and isothiazolo-pyrimidines but they overall retained relatively of low brightness values. To therefore expand the scope of fluorescent demethylated adenines and adenosines, we thus employed modified azetidines in place of the dimethylamine group to produce purines with augmented photophysical properties. Originally developed by Luke Lavis,[19–21] substituting the Me2N group found in common fluorophores with azetidines was reported to significantly improve the photophysical features of nearly all fluorophore scaffolds analyzed.[19,20] Substituents at the 3-position of the azetidine ring were found to further tune the emission maxima.[19] Considering the fluorescent nucleobase analogues discussed here contain dimethylamine substituents, we opted to synthesize novel fluorophores employing substituted azetidines and compare them to the Me2N bearing heterocycles. Here we report synthetic approaches to these novel structures and their photophysical properties, where unprecedented quantum yields and brightness coefficients are observed. The most promising combination of a purine surrogate with a substituted azetidine was then implemented in a nucleoside skeleton.

Results and Discussion

We first synthesized the dimethylated thieno and isothiazolo derivatives 2a and 2b through a 3-step divergent pathway, starting from either methyl 4-aminothiophene-3-carboxylate hydrochloride (7a) or methyl 4-aminoisothiazole-3-carboxylate hydrochloride (7b), respectively.[12] A facile cyclization of the 4-aminoheterocycles with formamidine acetate yielded the inosine analogues 8a and 8b, respectively, in good yield. Thionation of these purine analogues with phosphorous pentasulfide or Lawesson’s reagent produced the thiopheno (9a) and isothiazolo (9b) analogues in 83% and 92% yield, respectively. Displacement reactions with methanolic dimethylamine yielded the desired heterocycles 2a and 2b in 64% and 69% yield, respectively. X-ray crystal structure determination confirmed the proposed heterocycle structures.

The absorption and emission spectra of the two heterocycles 2a and 2b are given in figure 2 and the fundamental spectroscopic properties are summarized in table 1. Both compounds displayed substantial bathochromic shifted maxima in their aqueous ground-state absorption spectra compared to native m6,6A (346 nm and 350 nm, respectively, vs. 275 nm). The corresponding aqueous emission maxima exhibited only one emission band at 411 nm and 412 nm as opposed to the dual emission bands observed for the native dimethylated adenosine. No significant variations in quantum yield were observed when compared to m6,6A (<1%), indicating that the two synthetic dimethylated analogues remained weakly fluorescent in aqueous media. The absorption and emission spectra largely retained similar photophysical properties in D2O, indicating no major solvent isotope effect. However, an increase in the brightness coefficient of the thieno analogue 2a from 5 to 14 due to an increase in quantum yield, along with a corresponding decrease in brightness of the isothiazolo derivative 2b from 1.6 to 1.1 due to a drop in extinction coefficient, hinted to a potential minor solvent isotopic effect. Notably, the changes observed for 2b are likely within error of inherently miniscule values, but nevertheless, any solvent isotopic effects are likely due to the presence of the N7 nitrogen augmenting hydrogen bonding through the Hoogsteen face of the heterocycle.

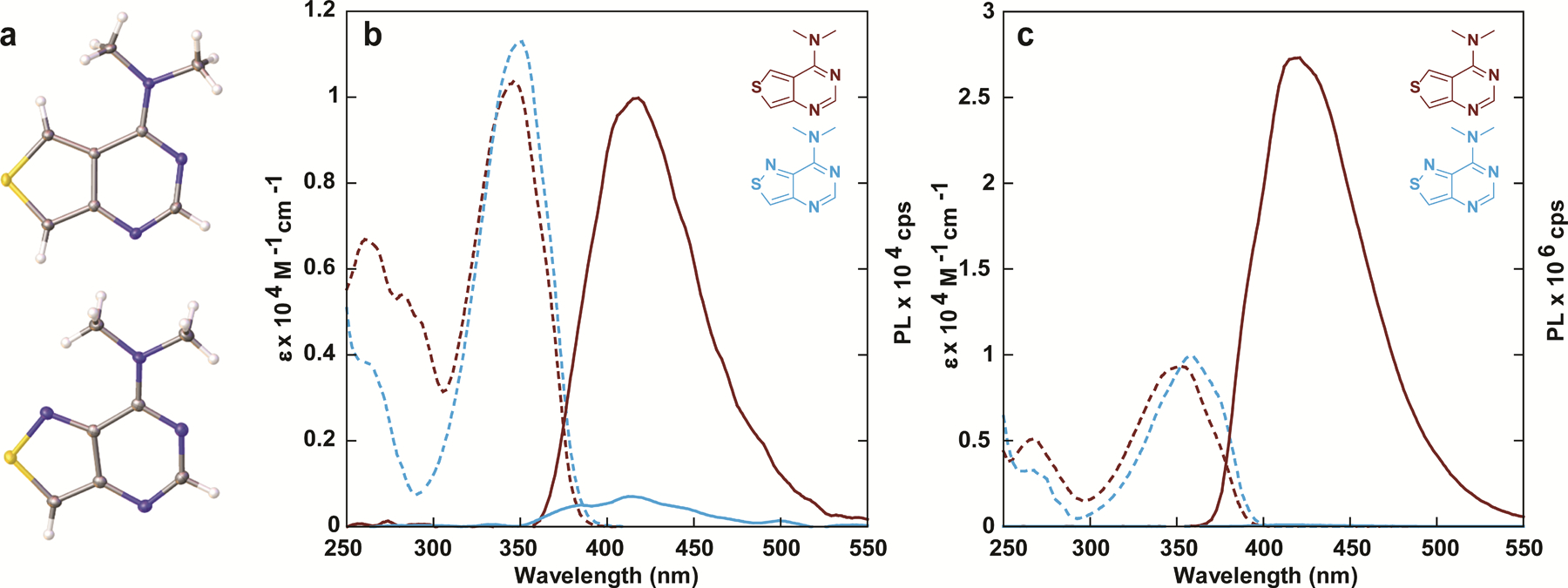

Figure 2.

(a) Crystal structures of compound 2a (top) and 2b (bottom). (b) absorption (dashed line) and emission (solid line) spectra of compounds 2a and 2b in water and (c) dioxane.

Table 1.

Photophysical Properties of Thieno [3,4-d] and Isothiazolo [4,3-d] Nucleobase Analogues 2a and 2b

| Solvent | λabs (ε)a | λem (Φ)a | Φε | Stokes Shifta | Polarity Sensitivityb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 c | water | 275 (n/a) | 355 (0.00035) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 568 (0.00026) | ||||||

| dioxane | 275 (n/a) | 333 (0.00051) | n/a | n/a | ||

| 493 (0.00062) | ||||||

| D2O | 275 (n/a) | 355 (0.00040) | n/a | n/a | ||

| 568 (0.00034 | ||||||

| 2a | water | 346 (1.03) | 411 (0.0005) | 5 | 3.80 | −0.69 |

| dioxane | 353 (0.94) | 416 (0.47) | 4392 | 4.33 | ||

| D2O | 346 (0.98) | 416 (0.0015) | 14 | 4.77 | ||

| 2b | water | 350 (1.13) | 412 (0.0001) | 1.6 | n/a | n/a |

| dioxane | 358 (0.92) | 418 (0.0010) | 11 | n/a | ||

| D2O | 349 (1.11) | 417 (0.0001) | 1.1 | n/a |

λabs, ε, λem and Stokes shift are reported in nm, 104 M–1 cm–1, nm and 103 cm–1 respectively. All the photophysical values reflect the average over three independent measurements.

Sensitivity to solvent polarity reported in cm–1/(kcal mol–1) is equal to the slope of the linear fit in figure S20.

Unlike the parent 1, the absorption spectra taken in dioxane were slightly red-shifted by almost 10 nm compared to aqueous solutions (346 to 353 nm, 350 to 358 nm for 2a and 2b respectively), and a similar trend was also observed in the emission spectra (411 nm to 416 nm, 412 nm to 418 nm, respectively, excitation at 350 nm). Intriguingly, while the quantum yield of analogue 2b increased ten-fold, that of corresponding analogue 2a increased nearly a thousand-fold and sharply rose to 47%. Additionally, exciting 2a in 10 nm increments between 260 nm and 380 nm in water and dioxane indicated no changes to the emission band after correcting for emission intensity (Figure S1b). Measuring the excitation spectra of the emission bands between 360 and 560 nm in water and dioxane indicated no distinct changes after correcting for intensity, suggesting that all emissive transitions observed are a result of excitation through the low energy absorption band (Figure S1c). However, when analyzing its sensitivity to polarity (Figure 3a), we found water to be an effective quencher (with as little as 5% in dioxane enough to drastically diminish the emission), a phenomenon noted in the behavior of (m6,6A) and its TICT state fluorescence quenching. Furthermore, substitution of the carbon atom at the 7-position of compound 2a (following native purine numbering) with a nitrogen atom (compound 2b) results in a loss of emission in dioxane.

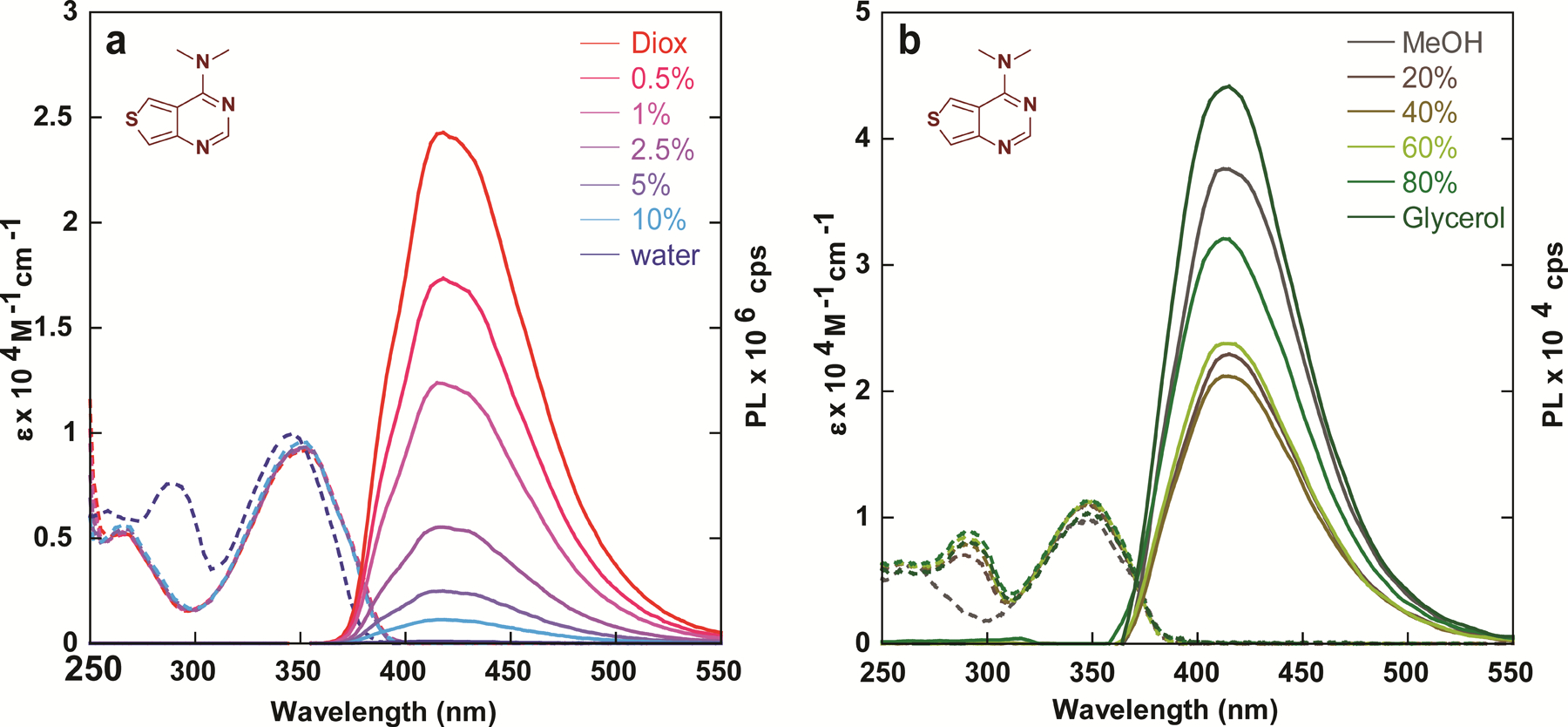

Figure 3.

Absorption (dashed line) and emission (solid line) of compound 2a in (a) water/dioxane mixtures and (b) MeOH/glycerol mixtures.

Fluorophores bearing dialkylamine substituents are known to non-radiatively decay through rotational relaxation around the carbon-nitrogen bond. To investigate the prevalence of this phenomenon in the analogues synthesized, we collected absorption and emission spectra in methanol/glycerol mixtures of varying viscosity (Figure 3b). Intriguingly, due to the analogues’ high sensitivity to microenvironmental polarity it appears that the effects of polarity outweigh the impact of viscosity in low % glycerol solutions (Figure S12), despite the relatively small polarity difference between the two (ΔET(30) = 1.6 kcal mol–1).[22] A drop in emission intensity is observed from 0 to 40% glycerol, yet beyond that it seems the effect of viscosity dominates, and the emission intensity steadily rises in solutions containing 40–100% glycerol. To circumvent or at least minimize the inevitable effects of polarity changes in solvent mixtures, we attempted to assess the effects of viscosity in a single solvent system, measuring the emission intensity in ethylene glycol whilst varying the temperature (Figure S14a). Notably, while the optical density remained unchanged, the emission intensity dropped slightly with increasing temperature, as expected due to the expected inverse relationship between emission quantum yield and temperature for Me2N-containing chromophores.

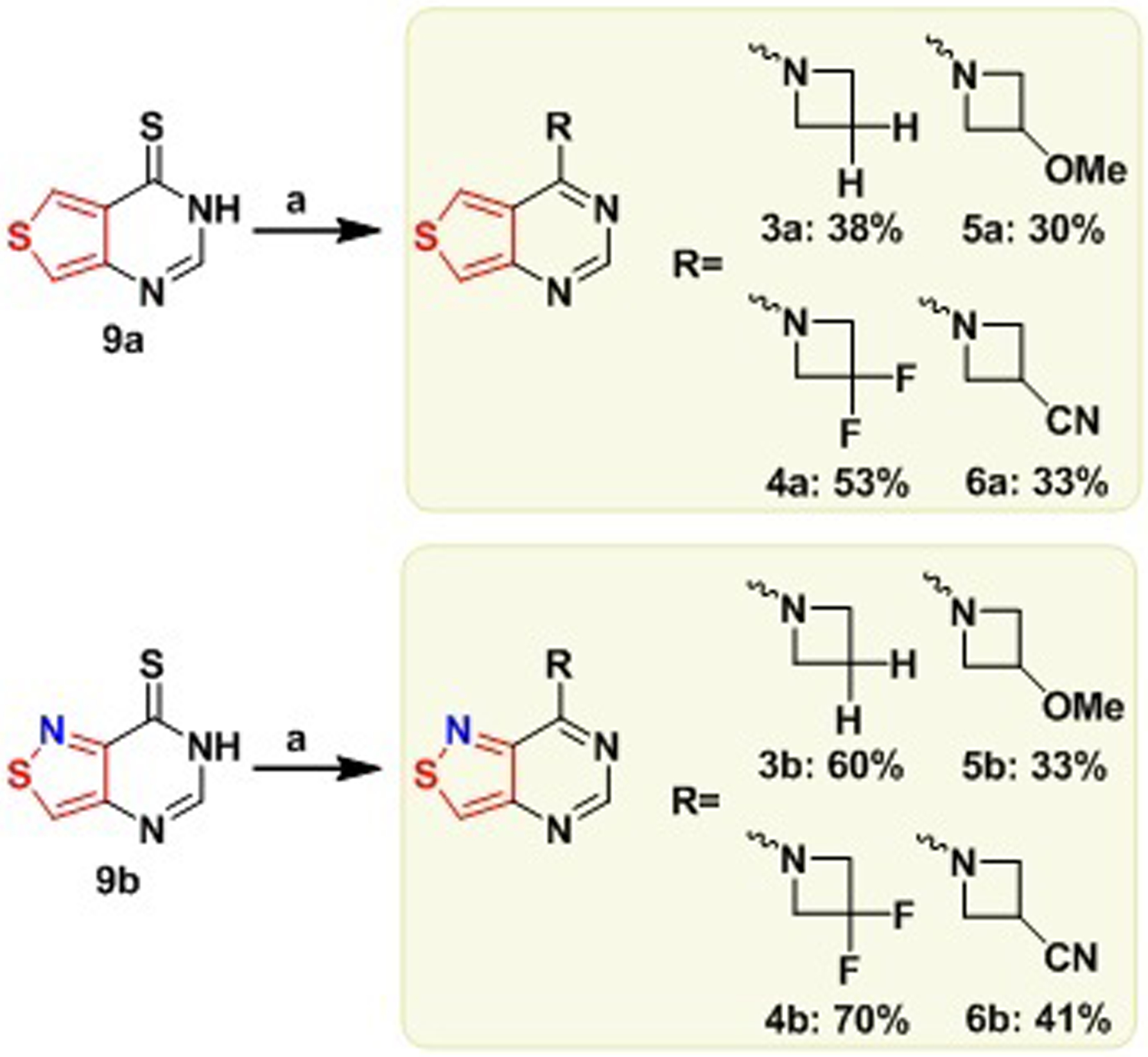

Ultimately, the dimethylated derivatives 2a and 2b exhibited less than desirable photophysical characteristics in aqueous solution due to their low emission quantum efficiencies, with only the thieno analogue 2a displaying strong fluorescence in relatively apolar media (e.g., dioxane), albeit with unusually high sensitivity to water content. We have therefore opted to employ the methodology pioneered by Lavis and substitute the dimethylamine groups on these fluorophores for azetidines. The strained azetidine ring reduces rotation around the C–N bond,[23] frequently limiting the non-radiative decay pathway through a TICT pathway.[23] Additionally, substituents at the azetidine’s 3 position were reported to shift the emission maxima across the visible, thus providing a molecular handle for tuning the photophysical features.[19] Initially, we opted to introduce the unsubstituted azetidine as well as the similarly sized 3,3-difluoroazetidine. Both the azetidine-bearing thieno and isothiazolo purine derivatives 3a–6a and 3b–6b, respectively, were synthesized through a substitution of the sulfur atom of the thionated intermediates 9a and 9b in methanol (scheme 2), similar to the pathway used for the heterocycles 2a and 2b (scheme 1). Since the commercial azetidines are provided as their hydrochloride salts, excess DIPEA was added to release the free cyclic secondary amines (scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Dimethyladenine Analogues 2a and 2b.

(a) H2RCl, DIPEA, MeOH, 60 °C, ON

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Dimethyladenine Analogues 2a and 2b.

(a) Formamidine acetate, EtOH, reflux, ON, X=CH: 78%, X=N: 76%. (b) i. X=CH: P2S5, Pyridine, 110 °C, 2 h, 83%; X=N: Lawesson’s reagent, Pyrdine, 110 °C, 2 h, 92%. (c) 2M HNMe2 in MeOH, 60 °C, ON, X=CH: 64%, X=N: 69%

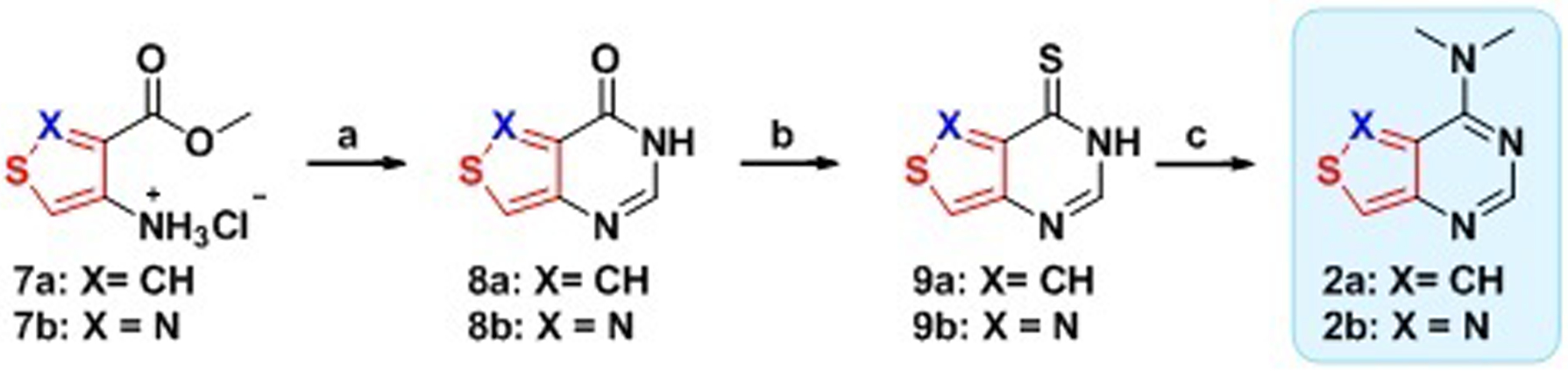

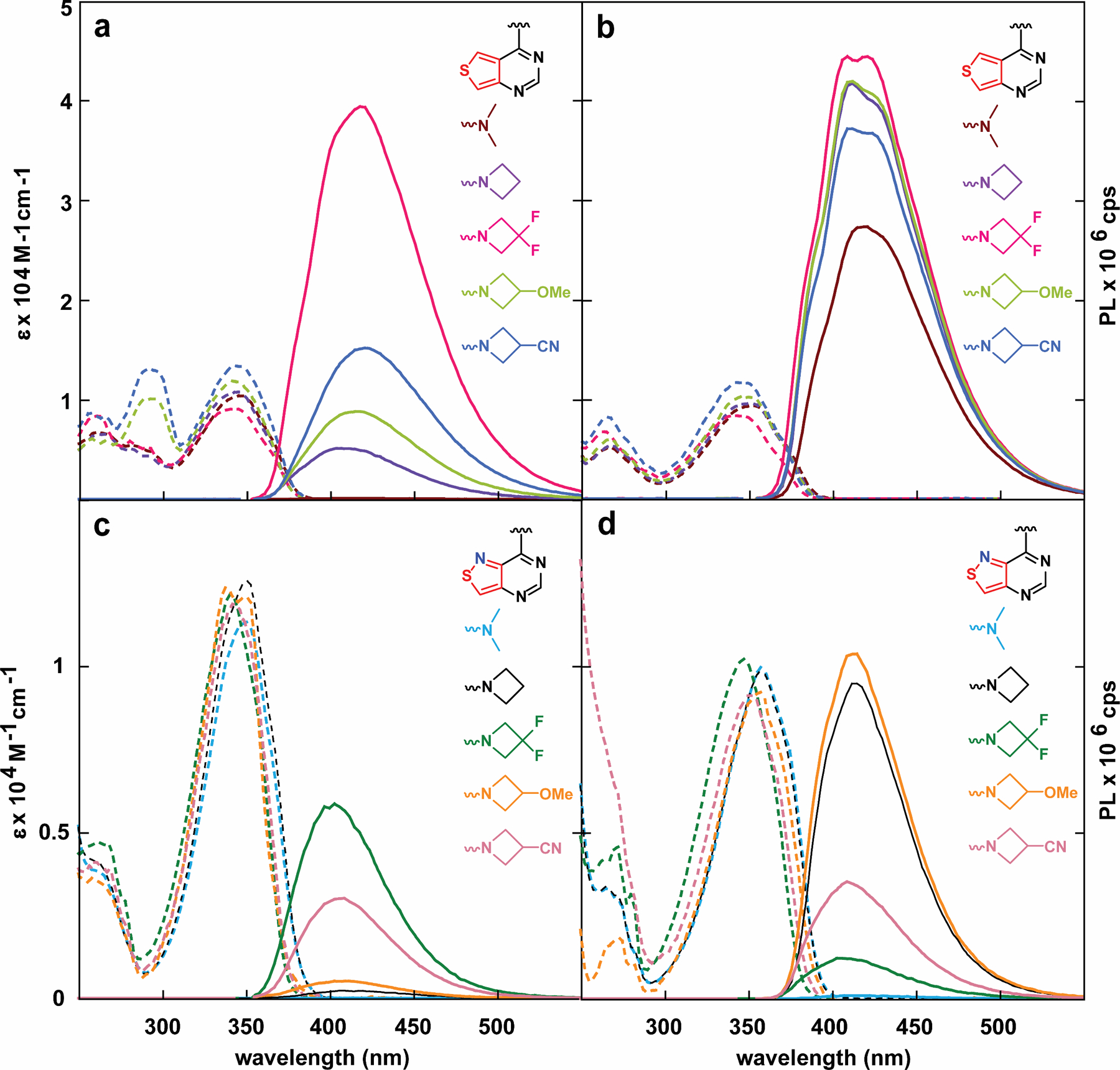

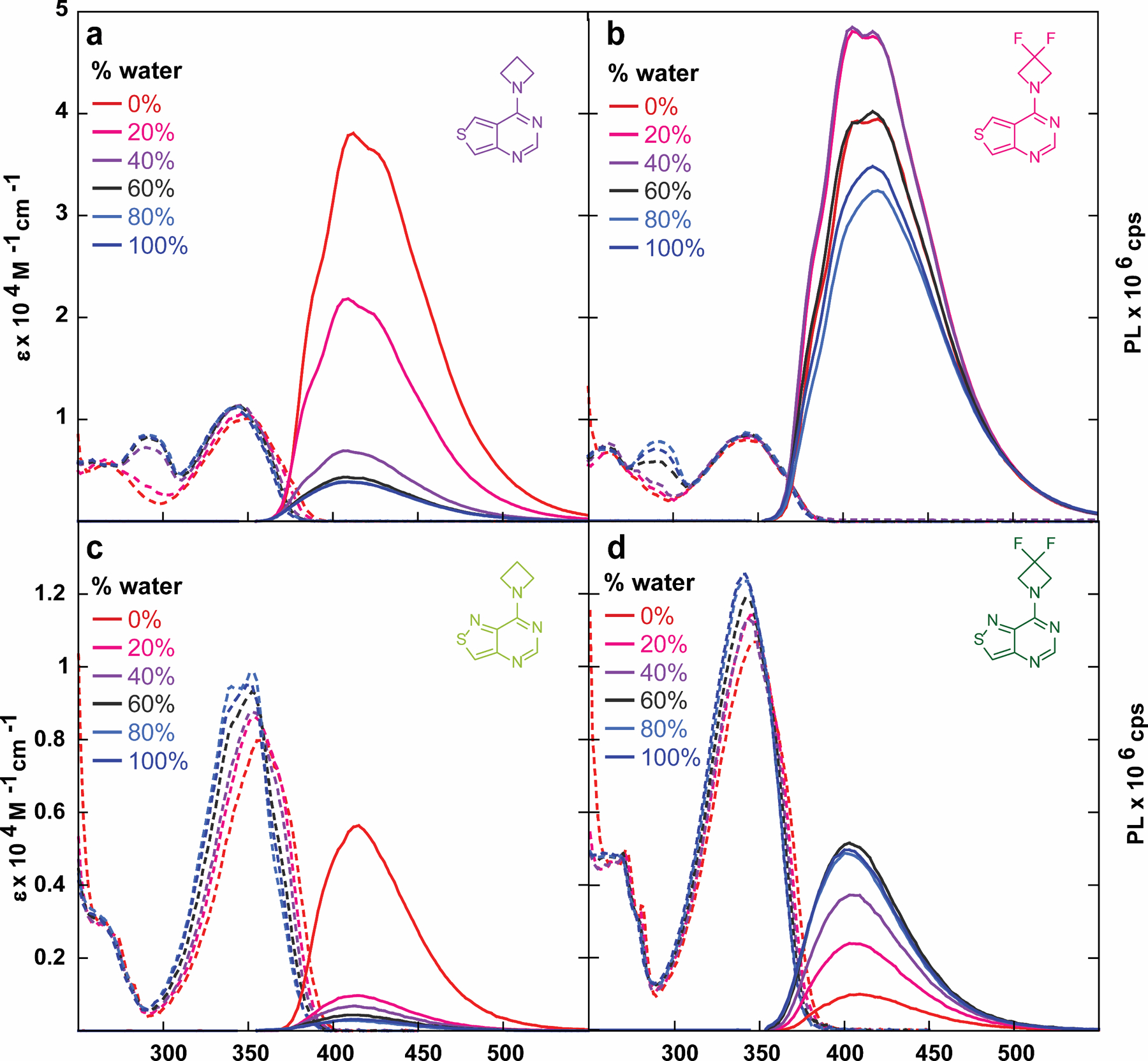

The absorption and emission spectra of heterocycles 2–6a and 2–6b are shown in figure 4 and their fundamental spectroscopic features are summarized in Table 2. Compared to the “parent” dimethylamino derivatives 2a and 2b, no significant changes in the absorption spectra were observed for the thieno- or isothiazolo- analogues bearing the azetidino substituents in aqueous solution, within a 10 nm range. A similar trend was observed in deuterium oxide. The emission maxima also exhibited minimal changes, yet the fluorescence quantum yields differed drastically, with compound 4a exhibiting a quantum yield of 64% in aqueous solution, nearly a thousand-fold higher than that of compound 2a (<0.1 %, Table 2). Intriguingly, the quantum yields of the isothiazolo analogues 3b and 4b also increased compared to analogue 2b (0.3 % and 6% vs. 0.1), but not to the same degree observed in analogues 3a and 4a (6% and 64%, respectively). Plotting the quantum yields values for 3–6b in water against the respective Hammett inductive substituent constants (σ1)[24] revealed an excellent correlation (figure 5). In D2O, a hypsochromic shift of 10 nm is observed in the emission maxima of 3a compared to 2a, which was not observed for 4a and 2a (406 and 418 vs. 416 nm), and an opposing trend is observed for the isothiazolo analogues, with azetidino derivative 3b possessing a similar emission maxima to 2b and the difluoro derivative 4b displaying a hypsochromic shift (415 and 403 vs. 417 nm, respectively), indicating the potential presence of a minor solvent isotope effect. The fluorescence quantum yields in D2O generally remain the same, although a slight decrease is observed for the difluoroazetidino-modified heterocycle 4a (0.57 in D2O vs. 0.64 in H2O).

Figure 4.

Absorption (dashed line) and emission (solid line) spectra of analogues 2–6a in (a) water (b) dioxane. (c) Absorption (dashed line) and emission (solid line) spectra of analogues 2–6b in water and (d) dioxane.

Table 2.

Photophysical Properties of Thieno [3,4-d] and Isothiazolo [4,3-d] Nucleobase Analogues 2–6a and b

| Solvent | λabs (ε)a | λem (Φ)a | Φε | Stokes Shifta | Polarity Sensitivityb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | water | 346 (1.03) | 411 (0.0005) | 5 | 3.80 | −0.69 |

| dioxane | 353 (0.94) | 416 (0.47) | 4392 | 4.33 | ||

| D2O | 346 (0.98) | 416 (0.0015) | 14 | 4.77 | ||

| 3a | water | 344 (1.11) | 407 (0.06) | 715 | 4.40 | 53 |

| dioxane | 351 (1.27) | 412 (0.75) | 9484 | 4.23 | ||

| D2O | 345 (1.00) | 406 (0.07) | 687 | 4.41 | ||

| 4a | water | 344 (0.90) | 419 (0.64) | 5766 | 5.14 | 81 |

| dioxane | 343 (0.85) | 419 (0.77) | 6587 | 5.26 | ||

| D2O | 343 (0.84) | 418 (0.57) | 4826 | 5.29 | ||

| 5a | water | 344 (1.12) | 415 (0.13) | 1421 | 4.99 | 80 |

| dioxane | 349 (1.03) | 411 (0.70) | 7218 | 4.28 | ||

| D2O | 344 (1.11) | 416 (0.15) | 1728 | 5.00 | ||

| 6a | water | 345 (1.30) | 421 (0.23) | 2951 | 5.17 | 110 |

| dioxane | 345 (1.19) | 409 (0.64) | 7579 | 4.52 | ||

| D2O | 344 (1.27) | 416 (0.33) | 4164 | 5.03 | ||

| 2b | water | 350 (1.17) | 412 (0.0001) | 1.6 | n/a | n/a |

| dioxane | 358 (1.03) | 418 (0.0010) | 14 | n/a | ||

| D2O | 349 (1.11) | 417 (0.0001) | 1.1 | n/a | ||

| 3b | water | 352 (1.22) | 416 (0.0030) | 33 | 4.38 | −17 |

| dioxane | 358 (1.05) | 415 (0.13) | 1192 | 3.84 | ||

| D2O | 349 (1.23) | 415 (0.0030) | 41 | 4.51 | ||

| 4b | water | 341 (1.21) | 403 (0.064) | 770 | 4.54 | 11 |

| dioxane | 348 (1.03) | 407 (0.020) | 173 | 4.19 | ||

| D2O | 341 (1.22) | 403 (0.073) | 884 | 4.49 | ||

| 5b | water | 346 (1.11) | 405 (0.007) | 77 | 4.12 | −2 |

| dioxane | 356 (0.96) | 413 (0.14) | 821 | 3.84 | ||

| D2O | 346 (1.06) | 408 (0.010) | 102 | 4.47 | ||

| 6b | water | 344 (1.11) | 406 (0.03) | 340 | 4.45 | 34 |

| dioxane | 352 (0.94) | 410 (0.06) | 607 | 4.07 | ||

| D2O | 343 (1.07) | 406 (0.03) | 293 | 4.49 |

λabs, ε, λem and Stokes shift are reported in nm, 104 M–1 cm–1, nm and 103 cm–1 respectively. All the photophysical values reflect the average over three independent measurements.

Sensitivity to solvent polarity reported in cm−1/ (kcal mol−1) is equal to the slope of the linear fit in figure S20. For full error analysis see table S1.

Figure 5.

Quantum yield vs Hammett inductive substituent constants (σ1) for compounds 3–6a (bottom) and compounds 3–6b (top).

The absorption maxima measured in dioxane show a hypsochromic shift for compounds 4–6a and 4–6b containing modified azetidines compared to 2a/3a and 2b/3b. While compounds 2–6a exhibited more classically shaped emission bands in water, the emission spectra in dioxane are highly irregular, likely indicating multiple partially overlapping emission bands (as the chromophores cannot tautomerize). Additionally, compounds 3–6a and 3–6b show significant increases in their emission quantum efficiency (0.64–0.77 and 0.02–0.14 respectively). Intriguingly, the emission quantum efficiencies of the isothiazolo- analogues 3–6b increased in dioxane compared to 2b but to a lesser extent than those seen in the thieno- derivatives. Taken together, the azetidine substitutions endows the respective heterocycles with unique photophysical properties, with the unsubstituted azetidine modification slightly improving quantum efficiency in water yet dramatically in dioxane, and the difluoroazetidine significantly elevating quantum efficiency in both water and dioxane. As previously observed, however, the presence of the “N7” atom seems to dramatically enhances the propensity for the fluorophores to non-radiatively decay. Whether that is through increased relaxation through a “dark” state or through solvent-mediated non-radiative relaxation of the excited state remains unclear.

Emission spectra of compounds 3–6b and 4–6b in water or dioxane, taken via excitation every 10 nm of their absorption band, show little variation in emission maxima, yet stark changes in emission intensity, suggesting minimal impact on their Franck-Condon states (Figure S1–S9). Analogue 4a, however, shows a slight shift in the emission band in water, indicating the potential presence of two emissive states. This, in conjunction with excitation spectra of compounds 3–6a/b taken at varying emission wavelengths show stark similarities to thieno- derivative 2a (Figure S1). Intriguingly, only derivative 4a shows variation in the excitation spectrum in water, with a particular excitation band at 280 nm increasing in intensity as the emission approaches longer wavelengths.

The sensitivity to polarity of compounds 3–6a/b in water–dioxane mixtures indicated that both azetidine-modified analogues 3a and 3b seemed to mirror the behavior of predecessor 2a, in that upon addition of water the fluorescence intensity of the main emission band decreases dramatically (Figure 6). Intriguingly, while isothiazolo analogue 4b exhibits increasing fluorescence intensity in water/dioxane mixtures with more water content due to its corresponding quantum efficiency in the two solvents, the thieno derivative 4a appears sporadic. A similar trend was observed in 6a as well, the two bases with the highest inductive Hammett constants. In water/dioxane mixtures with low water content, the fluorescence intensity initially increases plateauing at 20 or 40%. The compound then exhibits lower fluorescence intensity in solutions of higher water content, and the emission curve approaches a more “Gaussian” form (Figure 6b, Figure S14). Since electron-withdrawing substituents comprise the structural difference between compounds 3–6a, this suggests that the stark variations observed in the water-dioxane mixtures are likely attributed to their inductive impact on the charge transfer band of the heterocycle, a property previously introduced in figure 5. However, it is important to note that the inductive effect is not one from a substituent directly bonded to the π-system and signifies a rare occurrence in which a functional group separated from the heterocycle by sigma bonds is able to affect the photophysical properties of the chromophore. This inductive effect was also observed in Lavis’s original application of 3-modified azetidines.[19] However, the effects were observed on emission maxima rather than quantum yield as discussed here.

Figure 6.

Absorption (dashed line) and emission (solid line) spectra of compounds (a) 3a, (b) 4a, (c) 3b, and (d) 4b in water/dioxane mixtures.

Analysis of compounds’ 3–6a/b responsiveness to viscosity in ethylene glycol by varying the temperature indicated similar behavior to compound 2a, with no differences in the absorption spectra yet slight decreases in emission intensity (Figure S14–S17). Emission spectra taken in methanol/glycerol mixtures indicates bathochromic and hypsochromic shifts in mixtures with higher glycerol contents for compounds 4a and 3b, respectively (Figure 7). Given that structural rigidification through azetidine modifications are reported to diminish bond rotation compared to dialkylamino groups in both the ground and excited states, the diminution in fluorescence was expected, yet the shifts in emission maxima indicate potential solvent-dependent interactions with the excited state, despite very similar, though not identical, polarity for methanol and glycerol.

Figure 7.

Absorption (dashed line) and emission (solid line) spectra of compounds (a) 3a, (b) 4a, (c), 3b, and (d) 4b in MeOH/glycerol mixtures.

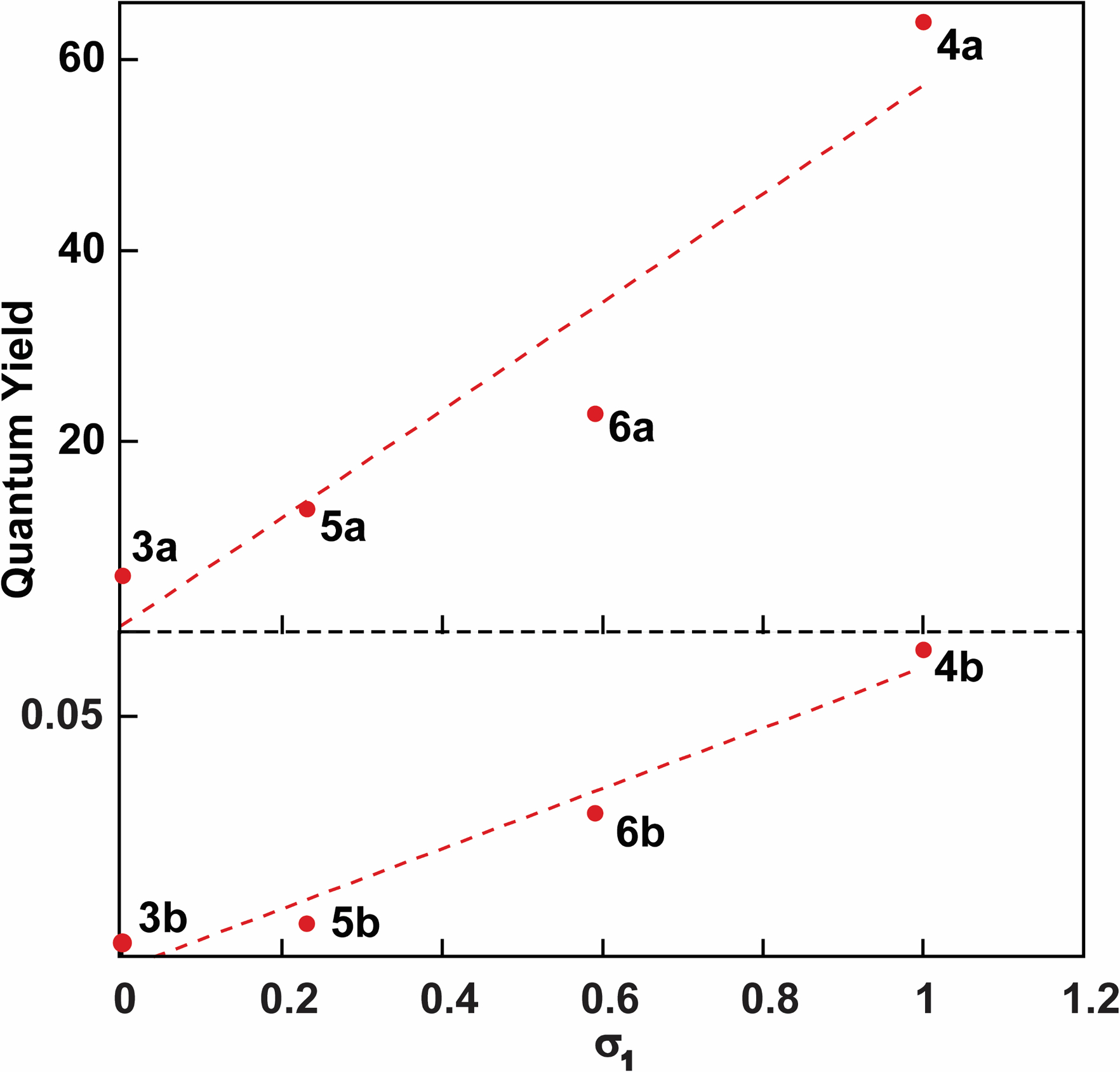

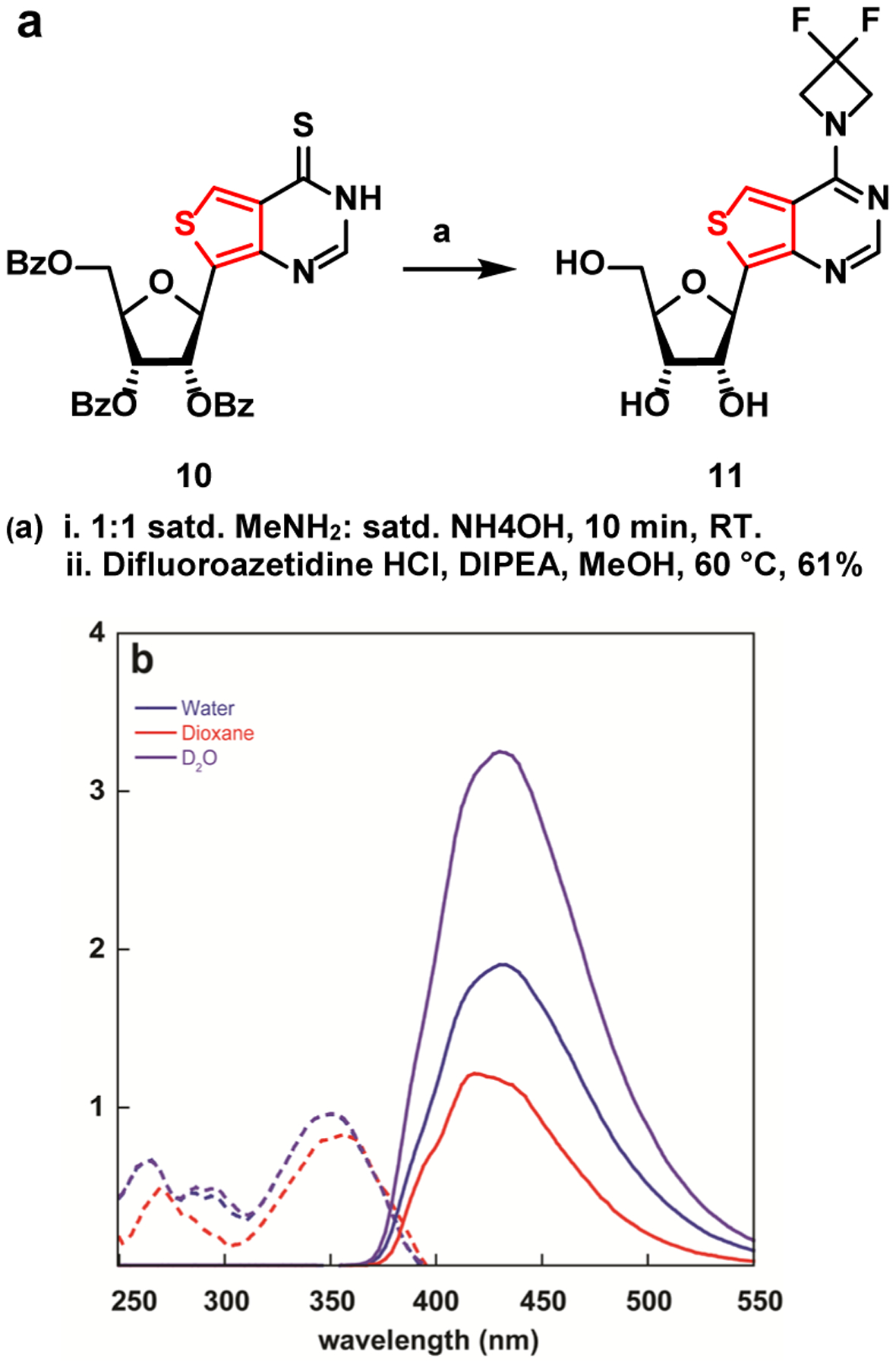

Inspired by the photophysical properties of compound 4a, we synthesized the ribonucleoside analogue 11 as a potential fluorescent surrogate of m6,6a. Deprotection of benzoate protected thioribonucleoside analogue 10[13] with 1:1 satd methylamine: satd. ammonium hydroxide, followed by SnAr with difluoroazetidine yielded the desired nucleoside 11 in 61% yield over two steps.

The photophysical parameters displayed by nucleoside 11 (figure 8b) differ from the ones possessed by its aglycon counterpart 4a. Incorporating the ribose moiety resulted in approximately 10 nm bathochromic shifts in the absorbance maxima in water, dioxane, and D2O compared to the nucleobase (352 vs 344 nm, 357 vs 343, 352 vs 343 nm, respectively). Similar shifts are visible in the emission maxima (435 vs 419 nm, 420 vs 419 nm, 431 vs 418 nm respectively) (table 1, table 2).

Figure 8.

(a) Synthesis of nucleoside 11. (b) Absorption (dashed line) and emission (solid line) of nucleoside 11 in water

Intriguingly, a two-fold and nearly a five-fold drop in quantum yield between 4a and 11 in water and dioxane, respectively, was observed (0.64 vs. 0.30 and 0.77 vs. 0.17, respectively). The emission quantum yield exhibits a significantly smaller drop in D2O (0.57 vs 0.47), indicating solvent-assisted quenching pathways play critical roles in defining the excited state landscape and processes of such chromophores. The substantial differences observed between H2O and D2O align well with a recent universal model proposed for the quenching effect of water, suggesting energy transfer to vibrational overtones and high energy stretching modes that exist in water and alcohols but become much less significant in the corresponding deuterated counterparts.[25] This observation explain the dichotomy frequently observed (although not well documented) between the photophysical features of the nucleobases compared to the corresponding modified nucleosides, suggesting a critical role for the sugar moiety that is frequently considered to be non-chromophoric and photophysically benign. The proximity of the sugar hydroxyl and their solvation may therefore impact the excited state features and should be further considered in designing fluorescent nucleosides and other emissive probes.

Conclusions

A series of N6,N6 dimethylated adenine, incorporating modified azetidines, has been developed turning otherwise non-fluorescent heterocycles into useful fluorophores in aqueous solutions. Importantly, the impact on the quantum yield of the fluorophores predictably depends on the substituent present at the 3-position of the four-membered heterocycle. While the azetidine modification has been shown to improve charge transfer-based fluorophores commonly used in fluorescence imaging,[19,20] this tactic appears to also be promising in producing highly emissive and responsive purine-like chromophores. Given the intense fluorescence of difluoroazetidine-modified nucleobase 4a, nucleoside 11 was prepared. Its photophysical features suggest high sensitivity to microenvironmental perturbations (e.g., polarity, viscosity). Additionally, the rigorously assessed solvent and isotopic effects (e.g., H2O vs. D2O) on the emission quantum yield of the new nucleobases/nucleoside should alert the community to the intricacies of fluorophore design and implementation in this and related fields.

While the azetidine modification has not yet been explored in the context of RNA oligonucleotides, we note that the fluorescent nucleobases/nucleosides developed in this work could potentially serve as useful probes for deconvoluting the biochemical significance of dialkylated adenosine residues in tRNA and rRNA through their sensitivity to their microenvironment. Challenges remain, however, particularly due to the presence of native dialkylated adenosines in complex RNA contexts (e.g., extensively modified rRNAs and tRNAs). Nevertheless, the fluorescent purine analogue described here could potentially evolve to serve as useful probes for deconvoluting the biochemical significance of dialkylated adenosine residues in RNA, exploiting the sensitivity of their photophysics to their microenvironment. We anticipate that once effective methods for site-specific incorporation of such probes into heavily modified RNAs are developed, their brightness and environmental sensitivity may assist in probing the spatiotemporal dynamics of dialkylated adenosine residues within tRNA and rRNA.

Experimental Section

Essential experimental procedures and data are given in the supporting information.

Crystallographic details

Deposition Number(s) 2140405 (for 2a), 2140406 (for 2b), 2140403 (for 5a), and 2140404 (for 6a) contain(s) the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Photophysical Properties of Nucleoside 11

| Solvent | λabs (ε)a | λem (Φ)a | Φε | Stokes Shifta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | water | 352 (0.94) | 435 (0.30) | 2838 | 5.41 |

| dioxane | 357 (0.85) | 420 (0.17) | 1444 | 4.21 | |

| D2O | 352 (0.95) | 431 (0.47) | 4486 | 5.23 |

λabs, ε, λem and Stokes shift are reported in nm, 104 M–1 cm–1, nm and 103 cm–1 respectively. All the photophysical values reflect the average over three independent measurements. For full error analysis see table S1.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institutes of Health (via grant number GM139407), the UCSD Molecular Mass Spectrometry Facility, Milan Gembicky and Jake Bailey (UCSD Crystallography Facility), Anthony Mrse (UCSD NMR Facility), and Andrea Fin for their assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References:

- [1].Jonkhout N, Tran J, Smith MA, Schonrock N, Mattick JS, Novoa EM, RNA 2017, 23, 1754–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McCown PJ, Ruszkowska A, Kunkler CN, Breger K, Hulewicz JP, Wang MC, Springer NA, Brown JA, WIREs RNA 2020, 11, e1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Neuner S, Micura R, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 22, 6989–6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Svetlov MS, Syroegin EA, Aleksandrova EV, Atkinson GC, Gregory ST, Mankin AS, Polikanov YS, Nat Chem Biol 2021, 17, 412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang Y-Z, Lindblom T, Chang A, Sudol M, Sluder AE, Golemis EA, Gene 2000, 257, 33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Demirci H, Murphy F, Belardinelli R, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V, Gregory ST, Dahlberg AE, Jogl G, RNA 2010, 16, 2319–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Seistrup KH, Rose S, Birkedal U, Nielsen H, Huber H, Douthwaite S, Nucleic Acids Research 2017, 45, 2007–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chan CTY, Chionh YH, Ho C-H, Lim KS, Babu IR, Ang E, Wenwei L, Alonso S, Dedon PC, Molecules 2011, 16, 5168–5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sinkeldam RW, Greco NJ, Tor Y, Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 2579–2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Albinsson B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 6369–6375. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ballini J-P, Daniels M, Vigny P, Eur Biophys J 1988, 16, 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rovira AR, Fin A, Tor Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 14602–14605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shin D, Sinkeldam RW, Tor Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 14912–14915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rovira AR, Fin A, Tor Y, Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 2983–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hallé F, Fin A, Rovira AR, Tor Y, Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2018, 57, 1087–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li Y, Ludford III PT, Fin A, Rovira AR, Tor Y, Chemistry – A European Journal 2020, 26, 6076–6084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li Y, Fin A, Rovira AR, Su Y, Dippel AB, Valderrama JA, Riestra AM, Nizet V, Hammond MC, Tor Y, ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 2595–2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bucardo MS, Wu Y, Ludford PT, Li Y, Fin A, Tor Y, ACS Chem. Biol 2021, 16, 1208–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Grimm JB, Muthusamy AK, Liang Y, Brown TA, Lemon WC, Patel R, Lu R, Macklin JJ, Keller PJ, Ji N, Lavis LD, Nat Methods 2017, 14, 987–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Grimm JB, English BP, Chen J, Slaughter JP, Zhang Z, Revyakin A, Patel R, Macklin JJ, Normanno D, Singer RH, Lionnet T, Lavis LD, Nature Methods 2015, 12, 244–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Grimm JB, Xie L, Casler JC, Patel R, Tkachuk AN, Falco N, Choi H, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Brown TA, Glick BS, Liu Z, Lavis LD, JACS Au 2021, 1, 690–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Reichardt C, Chem. Rev 1994, 94, 2319–2358. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Grabowski ZR, Rotkiewicz K, Rettig W, Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 3899–4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hansch Corwin, Leo A, Taft RW, Chem. Rev 1991, 91, 165–195. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maillard J, Klehs K, Rumble C, Vauthey E, Heilemann M, Fürstenberg A, Chem. Sci 2021, 12, 1352–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.