Abstract

Background:

In the REDUCE LAP-HF II trial, implantation of an atrial shunt device did not provide, overall, clinical benefit for patients with heart failure and preserved or mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF/HFmrEF). However, pre-specified analyses identified differences in response in subgroups defined by pulmonary artery systolic pressure during submaximal exercise, right atrial (RA) volume, and sex. Shunt implantation reduces left atrial (LA) pressures but increases pulmonary blood flow, which may be poorly tolerated in patients with pulmonary vascular disease (PVD). Based upon these results, we hypothesized that patients with latent PVD, defined as elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) during exercise, might be harmed by shunt implantation, and conversely that patients without PVD might benefit.

Methods:

REDUCE LAP-HF II enrolled 626 patients with HF, EF ≥40%, exercise pulmonary capillary wedge pressure ≥25 mmHg, and resting PVR <3.5 WU who were randomized 1:1 to atrial shunt device or sham control. The primary outcome, a hierarchical composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal ischemic stroke, recurrent HF events, and change in health status, was analyzed using the win ratio. Latent PVD was defined as PVR ≥1.74 WU (highest tertile) at peak exercise, measured prior to randomization.

Results:

Compared to patients without PVD (n=382), those with latent PVD (n=188) were older, had more atrial fibrillation and right heart dysfunction, and were more likely to have elevated LA pressure at rest. Shunt treatment was associated with worse outcomes in patients with PVD (win ratio 0.60, [95% CI 0.42, 0.86]; p=0.005) and signal of clinical benefit in patients without PVD (win ratio 1.31 [95% CI 1.02, 1.68]; p=0.038). Patients with larger RA volumes and men had worse outcomes with the device, and both groups were more likely to have pacemakers, HFmrEF, and increased LA volume. For patients without latent PVD or pacemaker (n=313, 50% of randomized patients), shunt treatment resulted in more robust signal of clinical benefit (win ratio 1.51 [95% CI 1.14, 2.00]; p=0.004).

Conclusions:

In patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF, the presence of latent PVD uncovered by invasive hemodynamic exercise testing identifies patients who may worsen with atrial shunt therapy, whereas those without latent PVD may benefit.

Keywords: heart failure, HFpEF, interatrial shunt, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary vascular disease, treatment, clinical trial

Brief Summary:

Exercise pulmonary vascular disease worsens response to atrial shunt in HFpEF, while patients with normal lung vasculature may benefit.

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) with preserved or mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF, HFmrEF) is a heterogenous syndrome that afflicts over half of patients with HF and has few effective treatments.1, 2 Elevation in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) at rest or with exercise is a unifying feature of HFpEF/HFmrEF that causes exertional symptoms, organ dysfunction, morbidity, and mortality.2–8 It has accordingly been hypothesized that treatments aimed at reducing PCWP during exercise will improve clinical status despite underlying mechanistic heterogeneity across the HFpEF/HFmrEF spectrum.9

In the REDUCE LAP-HF II trial, implantation of the Corvia Atrial Shunt (IASD System II) in patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF had no effect on the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or stroke, HF events, and health status.10 However, pre-specified analyses identified pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) <70 mmHg at 20W of exercise, right atrial (RA) volume index ≤29.7 ml/m2, and female sex as subgroups that appeared to benefit, whereas PASP ≥70 mmHg at 20W exercise, RA volume index >29.7 ml/m2, and male sex were associated with worse outcomes with the shunt.

Atrial shunts reduce PCWP by redistributing blood from the high-pressure left atrium (LA) to the lower-pressure right heart,11, 12 resulting in a ~25% increase in pulmonary blood flow.13 In the short term, shunt-related increases in lung blood flow have been associated with favorable effects on the pulmonary vasculature.13 However, sustained increases in lung blood flow following other shunts, such as those placed for renal dialysis access, have been linked to the development of right-sided HF,14, 15 which also commonly develops over time in chronic HFpEF/HFmrEF.16 Patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF and severe pulmonary vascular disease (PVD), defined invasively as a resting pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) >3.5 WU, were excluded from REDUCE LAP-HF II.9, 10 However, recent studies have shown that many patients display more subtle PVD that becomes apparent only during exercise (i.e., latent PVD), and these patients are not identifiable with imaging or invasive studies at rest.17–19

Given the important ramifications of potential responder subgroups to atrial shunt device treatment, and the identification of PASP during submaximal (20W) exercise as a potential marker of benefit or harm in a pre-specified subgroup analysis, we further investigated the response to shunt implantation in patients with or without latent PVD, defined by invasive hemodynamic exercise evaluation performed per protocol prior to randomization. We also explored other potential factors associated with RA remodeling and female sex that may alter treatment response to shunt therapy in this post hoc analysis from the REDUCE LAP-HF II trial.

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study will be shared with researchers who submit a detailed research proposal upon approval by the study steering committee. Data requests and detailed proposals can be submitted to Corvia Medical (info@corviamedical.com).

Patient Population

Detailed description of the rationale, methods, and primary results for the REDUCE LAP-HF II trial have been published.9, 10 Briefly, this was a randomized, international, multicenter, double-blind, sham-controlled trial conducted in 89 centers in the USA, Canada, Europe, Australia, and Japan. Patients with symptomatic HF and ejection fraction ≥40%, evidence of diastolic dysfunction, and elevated PCWP during exercise (≥25 mmHg) that exceeded right atrial (RA) pressure by ≥5 mmHg were enrolled. Key exclusion criteria included significant RV dysfunction; resting RA pressure >14 mmHg; PVR >3.5 Wood units at rest or at peak exercise; hemodynamically significant valve disease (including ≥ moderate tricuspid regurgitation); Stage D HF, cardiac index <2.0 L/min/m2, prior documented EF<30%, severe obstructive sleep apnea, chronic pulmonary disease requiring oxygen; body mass index >45 kg/m2; or an estimated glomerular filtration rate <25 mL/min per 1.73 m2. All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment. The study was approved by local ethics committees or institutional review boards at each enrolling site. The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03088033.

Study Protocol

Participants underwent comprehensive echocardiography and invasive hemodynamic exercise testing in the supine position prior to randomization to confirm eligibility. Pressures were measured in a blinded fashion at end-expiration at rest and during exercise at a central core lab, taking the average of ≥3 beats. Eligible participants were then randomly assigned (1:1) to receive the Corvia Atrial Shunt (IASD System II, Corvia Medical, Tewksbury, MA, USA) or a sham procedure, as previously described.12, 20 Echocardiograms and invasive hemodynamic pressure tracings were interpreted by independent core laboratories, blinded to all other data. Follow-up visits were conducted by clinicians masked to treatment allocation at 6, 12, and 24 months, where assessments were performed for adverse events, and health status Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) Overall Symptom Score (OSS).

Treatment Effect Modification by Pulmonary Vascular Disease Status

In subgroup analyses from REDUCE LAP-HF II, prespecified continuous variables were divided into tertiles, after which treatment by subgroup interactions were tested with respect to HF events. In these prespecified subgroup analyses from REDUCE LAP-HF II, there was a significant treatment interaction (p=0.002) effect by PASP during submaximal (20W) exercise.10 Exercise PA pressure is determined by PCWP, cardiac output, and PVR.21 Because patients with higher PCWP would be expected to benefit more from shunt treatment (higher LA pressure to drive shunting to the right atrium), we hypothesized that the treatment interaction observed for PA pressure would be related to elevation in exercise PVR, a marker of latent PVD,18 wherein patients with latent PVD (higher exercise PVR) may be more vulnerable to deleterious effects from shunt, and patients without latent PVD may derive benefit from the therapy. The present analyses were performed considering tertiles of exercise PVR, mirroring the prespecified subgroup analyses for PASP during exercise in the main trial.

Secondary Analysis of Other Treatment Effect Modifiers

As previously stated, 2 other subgroups were found to display a deleterious effect following shunt treatment in REDUCE LAP-HF II in prespecified subgroup analyses: men and participants with the highest tertile of RA volume index (>29.7 ml/m2) at baseline. To explore other potential characteristics associated with response to shunt treatment in addition to PVD, we identified baseline characteristics that commonly differed (defined by p<0.10) in both (1) men vs women and (2) patients with RA volume index > or ≤29.7 ml/m2, but that (3) were not significantly different in patients with or without latent PVD. Treatment responses were then contrasted in subgroups of patients with or without these characteristics in the presence or absence of latent PVD.

Efficacy and Safety Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint for this analysis was the hierarchical composite endpoint of: (a) cardiovascular death or non-fatal ischemic stroke through 12 months, (b) first and recurrent HF hospitalization or urgent intensification of oral diuresis (negative binomial regression) up to 24 months (analyzed when the last randomized patient completed 12 month follow-up), and (c) change in KCCQ OSS between baseline and 12 months, evaluating shunt effects in patients falling in the highest tertile of exercise PVR and the two lowest tertiles of exercise PVR. Key secondary efficacy endpoints included the individual components of the hierarchical composite and prespecified safety events. All events were adjudicated by a blinded clinical events committee.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean±SD and categorical variables were reported as the number and percentage of patients in each category. The win ratio22 was used as the primary analytic method in the post-hoc analyses presented here, where a win ratio >1 indicates a more favorable distribution of the primary endpoint components in the shunt group than in the control group. In the calculation of the win-ratio, all patients are compared with each other in a pairwise manner on the values of the three components, in a hierarchical manner. The win ratio method therefore provides the ability to combine time-to-event/binary (time to first incidence of cardiovascular death and/or nonfatal ischemic stroke, which was the first component in the hierarchy), recurrent (number of HF events and time-to-first HF when two patients being compared are tied on number of HF events, second in the hierarchy), and continuous (change from baseline KCCQ to 12 months, last in the hierarchy) outcomes, as was done here.

Additional analyses included individual examination of components of the primary efficacy endpoint (recurrent events analysis for HF events, using negative binomial regression adjusted for number of HF hospitalizations in the year prior to randomization; and change in KCCQ-OSS from baseline to 12 months using linear regression with adjustment for the baseline KCCQ-OSS value) calculated for each randomized treatment group within subgroups. The incidence of the major secondary safety endpoints was presented for each treatment group, with treatment group comparisons performed on the incidence rate using logistic regression within the main subgroup (presence or absence of latent PVD). The incidence of CV death or non-fatal stroke were compared between groups from Kaplan-Meier estimates. Log-rank p-value is presented with non-cardiovascular death treated as a competing risk. Interaction p-values were calculated for the outcome of recurrent HF hospitalization by entering the following terms in the negative binomial regression analyses: treatment, subgroup variable, and treatment × subgroup variable. Similar interaction analyses were performed using linear regression for the KCCQ-OSS outcome. Linear regression was used to examine continuous relationships between resting PVR and change in PVR with exercise.

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All statistical analyses were predefined in a post hoc statistical analysis plan following inspection of the prespecified trial results and were performed on the modified intent-to-treat population (defined as all randomized patients excluding those found to be ineligible after randomization) for whom peak PVR at baseline was able to be calculated. All P-values are two-sided. All statistical analyses were conducted independently (Baim Institute for Clinical Research, Boston, MA, USA; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; and Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA). An independent data safety and monitoring board reviewed study data approximately quarterly for all enrolled participants.

RESULTS

Of 626 participants randomized, 570 had the necessary measurements to calculate PVR at peak exercise and were included in the primary analysis (Figure S1). Participants displayed clinical characteristics typical of HFpEF/HFmrEF, including advanced age (mean 71 years), female predominance (61%), and high comorbidity burden (Table 1). Most patients had HFpEF (93%), and a minority had HFmrEF (7%).

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics

| No PVD (Exercise PVR<1.74) (n=382) |

Latent PVD (Exercise PVR≥1.74) (n=188) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.2±8.8 | 73.5±7.4 | <.001 |

| Female (n/%) | 61% (231/382) | 63% (118/188) | 0.742 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33±5.8 | 31.4±6.3 | 0.039 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 88% (335/381) | 89% (167/187) | 0.678 |

| Diabetes | 35% (134/382) | 40% (75/188) | 0.269 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 19% (73/382) | 21% (40/187) | 0.576 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 16% (59/379) | 18% (34/187) | 0.470 |

| Permanent Pacemaker | 18% (69/382) | 20% (38/188) | 0.537 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 47% (179/382) | 66% (124/188) | <.001 |

| Atrial Flutter | 9.2% (35/380) | 14% (25/185) | 0.145 |

| Heart Failure Status | |||

| NYHA Classification | 0.562 | ||

| II | 23% (86/382) | 20% (37/188) | |

| III | 76% (289/382) | 79% (149/188) | |

| IV | 1.8% (7/382) | 1.1% (2/188) | |

| HF visits within 12 Months of Enrollment2 | 42% (150/359) | 41% (72/175) | 0.926 |

| Hospitalization for HF in the past 12 Months | 28% (99/359) | 30% (52/175) | 0.610 |

| HFpEF (EF≥50%) | 94% (358/382) | 91% (171/188) | 0.231 |

| H2FPEF Score | 5 (4, 7) | 6 (5, 8) | 0.003 |

| Resting PCWP<15 mmHg | 33% (127/382) | 20% (37/188) | <.001 |

| Medications | |||

| Loop Diuretics | 80% (306/382) | 85% (160/188) | 0.167 |

| Thiazides Only | 4.2% (16/382) | 4.3% (8/188) | 1.000 |

| Loop Diuretics and Thiazides | 3.7% (14/382) | 8.0% (15/188) | 0.041 |

| Daily Furosemide Equivalent Dose (mg)1 | 55±50 (305) | 51±54 (160) | 0.401 |

| ACE-inhibitors or ARB | 61% (234/382) | 64% (120/188) | 0.582 |

| Beta-blockers | 69% (262/382) | 74% (139/188) | 0.205 |

| MRA | 53% (203/382) | 49% (92/188) | 0.373 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 3.1% (12/382) | 1.6% (3/188) | 0.406 |

| Other Baseline Measurements | |||

| BNP with AF | 196 (127,301) | 248 (113,447) | 0.317 |

| BNP without AF | 79 (37,147) | 128 (65,256) | 0.133 |

| NT-Pro BNP with AF | 881 (581,1325) | 1241 (833,1846) | 0.342 |

| NT-Pro BNP without AF | 270 (137,590) | 413 (255,723) | 0.001 |

| Estimated GFR | 56.4±18.2 (373) | 55.3±17.1 (184) | 0.496 |

For Subjects on Loop Diuretics)

Hospitalization/ER visit/Acute Care Facility Visit for Heart Failure

Latent PVD Definition and Patient Characteristics

The overall win ratio with shunt treatment as compared to sham treatment in REDUCE LAP-HF II was 1.0 [95% CI 0.8, 1.2], the incidence rate ratio (IRR) for HF events with shunt treatment was 1.26 (95% CI 0.84, 1.88), and the placebo-corrected 12-month change in KCCQ OSS with shunt was 1.2 [95% CI −2.3, 4.6]. Participants in the highest tertile of exercise PVR (≥1.74 WU) displayed a win ratio with shunt therapy significantly below 1.0, indicating clinical worsening, significant reduction in KCCQ OSS, and an increased risk for HF events (Table S1). Conversely, patients with exercise PVR in the lowest (<1.0 WU) and middle (1.0–1.73 WU) tertiles displayed or tended to display improvements in win ratio, KCCQ OSS, and lower HF event IRR. Because patients falling in the lower 2 tertiles responded more similarly to shunt treatment than the third tertile, and because prior studies have identified an upper limit of normal of ~1.8 WU for exercise PVR23 we used exercise PVR ≥1.74 WU to define latent PVD for the purposes of this analysis.

As compared to HFpEF/HFmrEF patients without latent PVD (exercise PVR<1.74 WU), those with latent PVD were older, had slightly lower BMI and higher H2FPEF score, were more likely to have atrial fibrillation, and were more likely to display elevated PCWP at rest (Table 1). On echocardiography, patients with latent PVD displayed similar LVEF and LA volumes as those without PVD, but E/e’ ratio and RA volume index were higher in latent PVD patients, with lower TAPSE, and a trend towards greater RV volume index (Table 2). On right heart catheterization, patients with latent PVD had higher RA pressure, PCWP, mean PA pressure, and PVR; and lower cardiac output compared with patients without PVD. During exercise, PVR increased on average in patients with latent PVD, with lower cardiac output, but exercise PCWP was similar to values observed in patients without PVD, indicating that the greater elevation in PA pressures in the latent PVD group is explained by PVR and not downstream LA pressures.

Table 2:

Cardiac Structure, Function, and Hemodynamics at Baseline

| Cardiac Structure and Function | No PVD (Exercise PVR<1.74) (n=382) |

Latent PVD (Exercise PVR≥1.74) (n=188) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (%) | 60±8 | 59±8 | 0.200 |

| LA volume index (ml/m2) | 34±13 (347) | 35±17 (172) | 0.270 |

| Septal E/e’ ratio | 15.1±6.7 (343) | 17.6±8.3 (161) | 0.001 |

| Mitral regurgitation (trace/mild/mod %) | 49/43/8 | 41/47/12 | 0.093 |

| TAPSE (cm) | 2.1±0.4 (339) | 1.9±0.4 (157) | <.001 |

| RV volume index (ml/m2) | 23±9 (276) | 25±11 (117) | 0.063 |

| RA volume index (ml/m2) | 27±12 (314) | 31±15 (145) | 0.003 |

| Resting Hemodynamics | |||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 72±13 (381) | 71±12 (188) | 0.688 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 141±25 (360) | 146±29 (174) | 0.046 |

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 9±4 (378) | 10±4 (187) | 0.026 |

| PA mean pressure (mmHg) | 25±7 (375) | 31±8 (187) | <.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 18±7 (375) | 20±6 (187) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac output (l/min) | 5.7±2.2 (366) | 5.0±1.3 (185) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (WU) | 1.4±0.6 (370) | 2.3±0.9 (185) | <.001 |

| Peak Exercise Hemodynamics | |||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 101±22 (381) | 102±24 (185) | 0.622 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 158±34 (339) | 165±34 (168) | 0.036 |

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 18±5 (379) | 20±7 (186) | <.001 |

| PA mean pressure (mmHg) | 44±8 (382) | 52±10 (188) | <.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 35±8 (382) | 35±9 (188) | 0.672 |

| Cardiac output (l/min) | 9.1±2.8 (382) | 7.1±2.3 (188) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (WU) | 0.98±0.43 (382) | 2.76±0.82 (188) | <.001 |

Impact of Latent PVD on Efficacy and Safety Outcomes

Baseline characteristics in patients with and without latent PVD randomized to shunt or sham were well matched between treatment groups, with no clinically relevant differences (Tables S2 and S3). In patients without latent PVD, treatment with the shunt was associated with 31% higher likelihood of clinical benefit as compared to sham procedure (win ratio 1.31 [95% CI 1.02, 1.68]; p=0.038 for superiority of shunt over sham) (Table 3). Conversely, in patients with latent PVD, treatment with the shunt was associated with 40% lower likelihood of clinical benefit (win ratio 0.60, [95% CI 0.42, 0.86]; p=0.005). Cardiovascular death and nonfatal ischemic stroke were uncommon (total of 6 events at 12 months of follow-up in the overall REDUCE LAP-HF II cohort) and did not statistically differ in patients with and without latent PVD.

Table 3:

Efficacy Outcomes Stratified by Latent Pulmonary Vascular Disease

| Subgroup | Variable | Statistic | Atrial Shunt Device Treatment | Sham Control | Win Ratio (95% CI) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVD | N=88 | N=100 | ||||

| Composite Primary Endpoint | Win Ratio1 | - | - | 0.60 (0.42, 0.86) |

0.005 | |

| CV Death/Non-fatal stroke | Cumulative incidence (n/%)2 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | - | 0.647 | |

| HF admission for IV diuresis or outpatient intensification of oral diuretics | Rate per person-year3 | 0.47 | 0.25 | - | 0.002 | |

| Change in KCCQ OSS at 12 months | Mean ± SD (n available)4 |

4.1 ± 20.4 (82) |

9.9 ± 19.8 (93) |

- | 0.027 | |

| No PVD | n=200 | N=182 | ||||

| Composite Primary Endpoint | Win Ratio1 | - | - | 1.31 (1.02, 1.68) |

0.038 | |

| CV Death/Non-fatal stroke | Cumulative incidence (n/%)2 | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | - | 0.178 | |

| HF admission for IV diuresis or outpatient intensification of oral diuretics | Rate per person-year3 | 0.17 | 0.23 | - | 0.103 | |

| Change in KCCQ OSS at 12 months | Mean ± SD (n available)4 |

14.6 ± 21.4 (190) |

9.2 ± 20.7 (169) |

- | 0.010 |

See methods section for explanation of the win ratio.

From Kaplan-Meier estimates. Log-rank P-value is presented with non-cardiovascular death treated as a competing risk.

P-value calculated using negative binomial regression (see methods section for further details)

P-value for change in KCCQ score from baseline to 12 months calculated with linear regression adjusting for baseline score.

The total rate of HF events was 0.20 events per patient-year in those without latent PVD and 0.35 in those with latent PVD (p=0.040 by t-test). In patients without latent PVD, atrial shunt treatment tended to reduce HF events (incidence rate ratio, IRR 0.71 [95% CI 0.42, 1.20]) and improved KCCQ OSS (+5.5 compared to control [95% CI +1.6, +9.5], p=0.0057) (Table 2). The odds ratio (OR) of shunt vs. sham for a ≥15-point improvement in KCCQ OSS following atrial shunt treatment was 1.66 [95% CI 1.07, 2.59] at 12 months in patients without PVD, while numerically fewer shunt patients than sham patients experienced no change or reduction in KCCQ OSS (Figure S2). Patients without latent PVD treated with atrial shunt therapy were more likely to display improvement in NYHA functional class 12 months as compared to sham control (OR 2.00 [95% CI 1.32, 3.03], p=0.001; Figure S3).

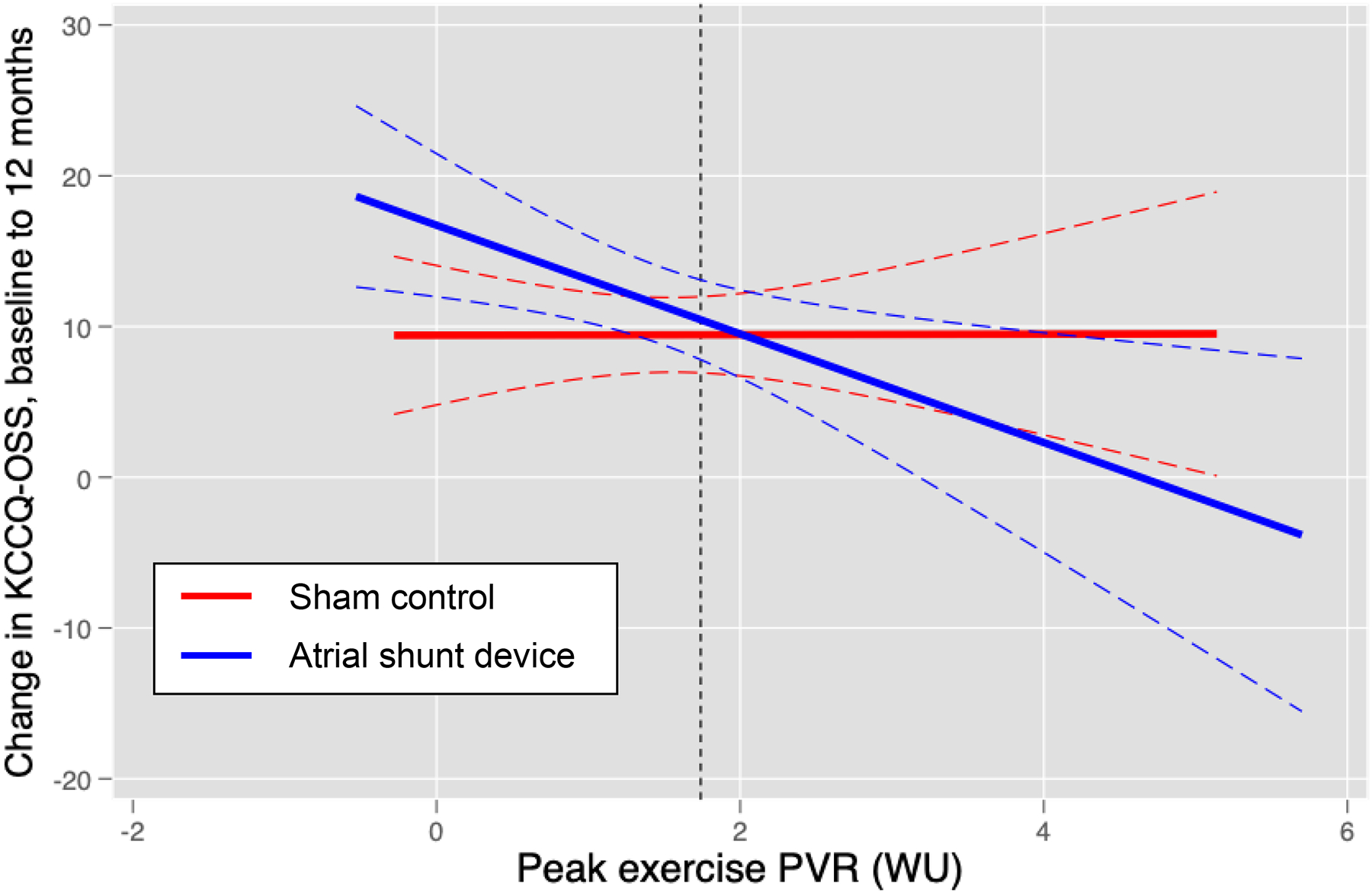

Conversely, in patients with latent PVD, shunt treatment resulted in an increase in HF events (IRR 2.48 [95% CI 1.23, 5.01]) and a lower (worse) KCCQ OSS (−6.2 [95% CI −11.8, −0.7], p=0.027) (Table 3). The OR of shunt vs. sham for a ≥15-point improvement in KCCQ OSS was 0.59 [95% CI 0.31, 1.15] at 12 months in patients with latent PVD, the likelihood of no change or worsening in KCCQ OSS was greater in shunt than in sham for patients with latent PVD (Figure S2), and there was no significant change in NYHA class (OR 1.04 [95% CI 0.57, 1.90], p=0.91; Figure S3). There was a significant interaction effect by exercise PVR for change in KCCQ OSS (interaction p=0.046) and for HF event IRR (interaction p=0.050). In linear regression analyses adjusting for baseline value, change in KCCQ OSS was inversely related to exercise PVR in patients receiving shunt, whereas there was no significant relationship observed in patients receiving sham control (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Linear regression plotting the relationship between change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy overall summary score (KCCQ-OSS) at 12 months versus baseline following atrial shunt device (blue) or sham control (red). There was a significant group interaction in the relationship between exercise PVR and change in KCCQ-OSS noted (p=0.046).

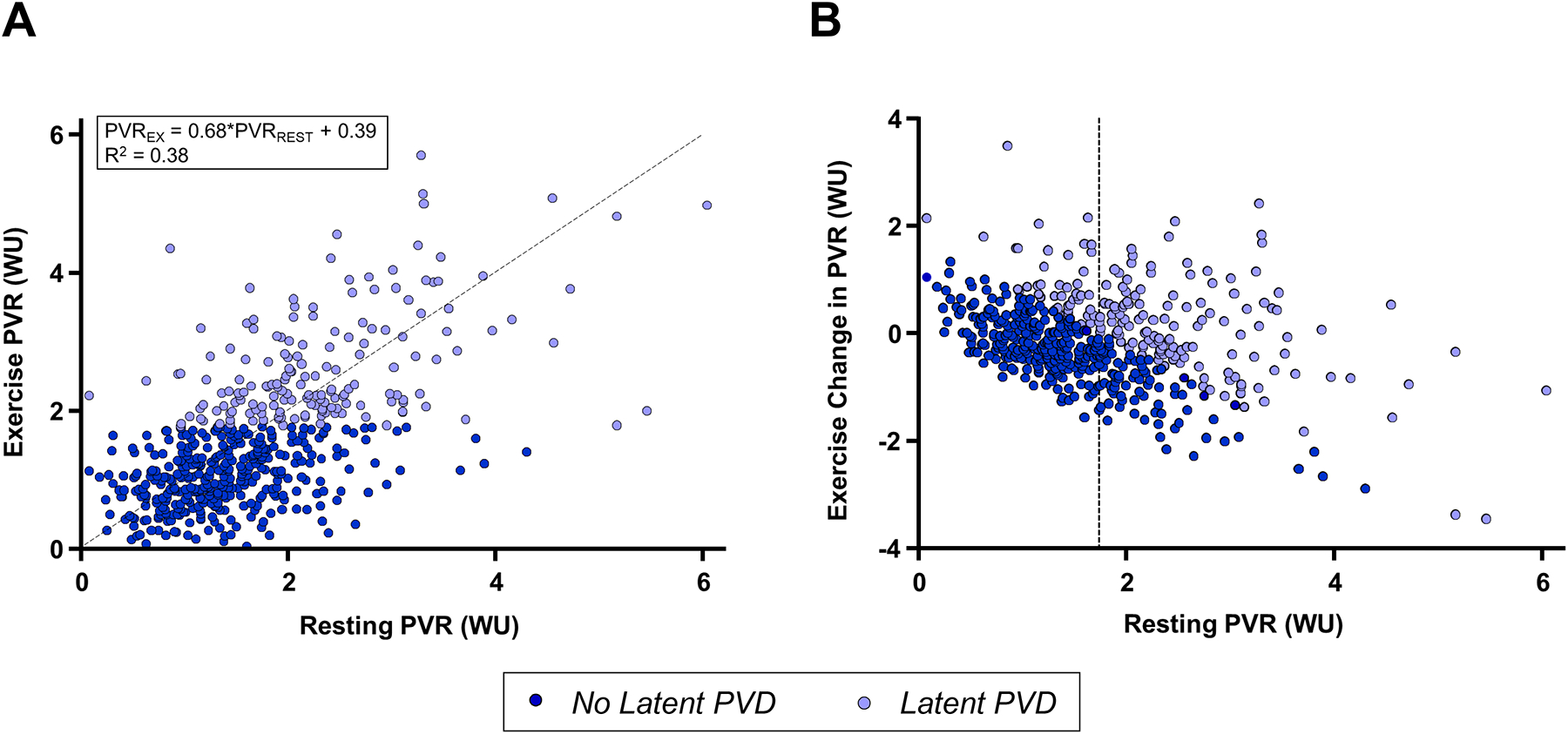

In regression analysis, rest PVR explained only 38% of the variance in exercise PVR, and many patients with normal rest PVR displayed exercise PVR≥1.74 WU, while many others without latent PVD displayed resting PVR≥1.74 WU (Figure 2). In contrast to latent PVD unmasked by exercise, there was no relationship between resting PVR and response to shunt treatment in regression analyses, indicating that hemodynamic responses during provocation are necessary to identify treatment responders (treatment-by-resting PVR interaction p=0.49 for total HF events and p=0.29 for time to first HF event). There was also no interaction between treatment effect and exercise change in PVR (p=0.35), or the ratio of exercise PVR to resting PVR (p=0.55).

Figure 2:

Correlations between rest and exercise pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). [A] Exercise PVR was only modestly correlated with resting PVR (R2 0.38), while many patients with normal resting PVR had elevations during exercise, as well as patients with higher resting PVR that became more normal during exercise, indicating intact pulmonary vascular reserve [B]. Dashed line in [A] shows the line of identity, while dashed line in [B] shows resting PVR 1.74 WU.

In safety results among patients without latent PVD, there was a significantly higher incidence in procedural bleeding complications in those randomized to the shunt device vs. sham (p=0.008), but no statistically significant difference in the risk of major adverse cardiac events as compared to sham (p=0.674), and a trend for lower risk of new onset or worsening kidney function (p=0.050, Table S4). Safety results in the group with latent PVD also revealed higher bleeding rates in shunt vs. sham, with a trend to greater risk of major adverse cardiac events in shunt vs. sham (p=0.057).

Effects on Cardiac Structure and Hemodynamic Estimates

At 12 months, there was no effect of shunt therapy on TAPSE or E/e’ ratio in patients with or without latent PVD (Table 4). In patients without latent PVD, there were significant increases in RA and RV volume following shunt treatment as compared to sham control, with no statistically significant changes in left ventricular (LV) end diastolic volume (LVEDV) or LA volume. In contrast, patients with latent PVD displayed no statistically significant changes in RA, RV, or LA volume, but there was a significant decrease in LVEDV (Table 4). In patients without latent PVD, tricuspid regurgitation severity and peak tricuspid regurgitation velocity increased slightly (but to a greater extent) in the shunt device-treated patients compared to sham. In patients with latent PVD, tricuspid regurgitation severity and peak tricuspid regurgitation velocity increased slightly in both treatment groups, with no difference between shunt and sham arms of the study (Table 4).

Table 4:

Effects on Cardiac Structure and Hemodynamics

| Change in Cardiac Structure at 12 months | Shunt | Sham | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Latent PVD | |||

| RA volume index, ml/m2 | +7±10 (124) | +1±8 (106) | <.001 |

| RV diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | +9±11 (100) | +3±10 (92) | <.001 |

| TAPSE, cm | +0.0±0.4 (144) | −0.0±0.4 (123) | 0.254 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation severity (0–4) | +0.31±0.58 (139) | +0.06±0.55 (119) | <.001 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation velocity (m/s) | +0.18±0.46 (136) | +0.04±0.50 (110) | 0.023 |

| LA volume index, ml/m2 | +1±8 (147) | +1±9 (126) | 0.900 |

| LV end diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | −6±10 (154) | −4±13 (133) | 0.157 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | +2±5 (162) | +2±6 (138) | 0.848 |

| E/e’ ratio | +0.1±13.2 (155) | +0.1±4.7 (132) | 0.968 |

| Latent PVD | |||

| RA volume index, ml/m2 | +6±13 (52) | +3±10 (53) | 0.227 |

| RV diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | +7±12 (40) | +5±12 (40) | 0.367 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation severity (0–4) | +0.22±0.48 (62) | +0.22±0.43 (63) | 0.956 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation velocity (m/s) | +0.19±0.63 (58) | +0.06±0.47 (58) | 0.237 |

| TAPSE, cm | +0.1±0.4 (59) | +0.0±0.4 (64) | 0.366 |

| LA volume index, ml/m2 | +1±10 (63) | +2±8 (64) | 0.383 |

| LV end diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | −8±12 (61) | −2±12 (65) | 0.008 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | +2±5 (64) | +2±6 (68) | 0.481 |

| E/e’ ratio | −0.2±4.9 (63) | −0.1±4.7 (69) | 0.899 |

Additional Responder Analyses

As previously reported,10 there were significant treatment effect interactions with sex and RA volume in REDUCE LAP-HF II, with poorer efficacy observed in men and in patients in the highest tertile of RA volume. In comparing men and women (Table S5) and patients with or without increased RA volume at baseline (Table S6), history of pacemaker implantation, prevalence of HFmrEF, and LA volume index emerged as variables at least trending towards being significantly different (p<0.10), while these baseline variables did not differ significantly in patients with vs. without PVD (Table 1).

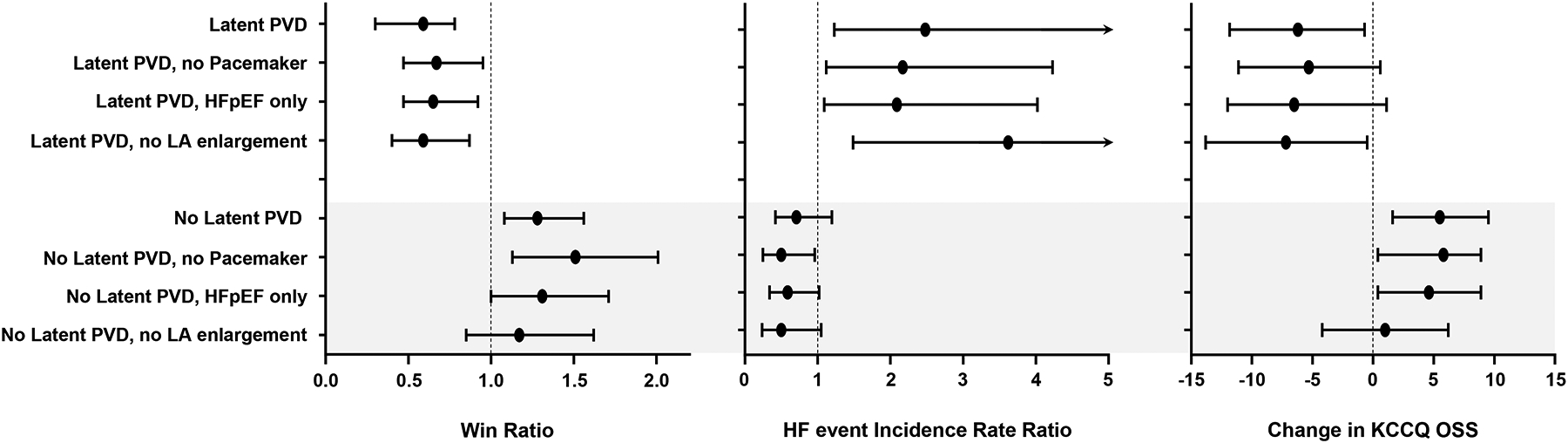

In patients with either latent PVD, pacemaker, HFmrEF, or LA enlargement, shunt treatment decreased the likelihood of clinical benefit, increased HF event risk and worsened health status compared to baseline (Table 5, Figure 3). Conversely, in patients with no PVD and no pacemaker (n=313, 50% of randomized patients), shunt treatment resulted in 51% greater likelihood of clinical benefit (win ratio 1.51 [95% CI 1.14, 2.01]), lower HF event rate (IRR 0.49 [95% CI 0.25, 0.95]) and greater KCCQ OSS improvement (+5.9 [95% CI 1.4, 10.3]) (Table 5, Figure 3). Similar benefits were observed for patients with no latent PVD and no HFmrEF, but there was no statistically significant relationship between LA enlargement and treatment response.

Table 5:

Efficacy Outcomes Stratified by Latent PVD and Other Subgroups

| Win Ratio | 95% CI | P | HF event IRR | 95% CI | P | Change in KCCQ | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No latent PVD with: (n sham/IASD) | |||||||||

| No Pacemaker (152/161) | 1.52 | 1.14, 2.00 | 0.004 | 0.49 | 0.25, 0.95 | 0.034 | +5.9 | 1.5, 10.3 | 0.010 |

| No HFmrEF1 (172/186) | 1.30 | 1.00, 1.69 | 0.050 | 0.58 | 0.34, 1.01 | 0.055 | +4.8 | 0.7, 8.9 | 0.022 |

| No LAE2 (108/132) | 1.21 | 0.88, 1.67 | 0.240 | 0.49 | 0.23, 1.04 | 0.063 | +1.6 | −3.4, 6.7 | 0.528 |

| Pacemaker (30/39) | 0.73 | 0.40, 1.32 | 0.295 | 1.47 | 0.62, 3.52 | 0.382 | +3.5 | −5.2, 13.2 | 0.423 |

| HFmrEF1 (10/14) | 1.47 | 0.53, 4.11 | 0.461 | 6.88 | 0.65, 73.2 | 0.110 | +14.5 | −5.2, 34.2 | 0.140 |

| LAE2 (74/68) | 1.38 | 0.92, 2.08 | 0.124 | 1.12 | 0.54, 2.33 | 0.766 | +9.8 | 3.5, 16.1 | 0.003 |

| Latent PVD with: (n sham/IASD) | |||||||||

| No Pacemaker (83/67) | 0.58 | 0.39, 0.86 | 0.008 | 2.39 | 1.13, 5.05 | 0.023 | −6.4 | −12.5, 0.3 | 0.041 |

| No HFmrEF1 (90/81) | 0.60 | 0.42, 0.88 | 0.008 | 2.28 | 1.05, 4.96 | 0.038 | −6.8 | −12.5, −1.1 | 0.021 |

| No LAE2 (53/55) | 0.57 | 0.36, 0.90 | 0.016 | 2.11 | 0.81, 5.51 | 0.126 | −16.8 | −16.8, −1.8 | 0.016 |

| Pacemaker (17/21) | 0.61 | 0.27, 1.37 | 0.230 | 3.61 | 0.48, 27.42 | 0.214 | −6.9 | −21.3, 7.6 | 0.342 |

| HFmrEF1 (17/10) | 0.53 | 0.16, 1.77 | 0.304 | 6.78 | 0.59, 77.38 | 0.123 | −1.0 | −25.3, 23.4 | 0.933 |

| LAE2 (47/33) | 0.66 | 0.38, 1.16 | 0.147 | 3.44 | 1.14, 10.40 | 0.029 | −3.3 | −12.1, 5.5 | 0.453 |

CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure; IRR, incidence rate ratio; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary score; PVD, pulmonary vascular disease; IASD, interatrial shunt device; HFmrEF, heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; LAE, left atrial enlargement

HFmrEF defined by EF 40–49%

LAE defined as values in the highest tertile (left atrial volume index>36.68 ml/m2)

Figure 3:

Forest plot displaying win ratio (left), heart failure (HF) event incidence rate ratio (middle) and change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary score (KCCQ OSS) in responder groups. PVD, pulmonary vascular disease; LA, left atrial. Bars reflect 95% confidence intervals.

In patients without latent PVD, when stratified by sex, there was no difference between sexes in terms of response to treatment, with both men and women improving with the shunt device compared to sham (win ratio 1.27 [95% CI 0.92, 1.77], p=0.15 in women with PVR <1.74 WU, and win ratio 1.32 [95% CI 0.88, 1.97], p=0.18 in men with PVR <1.74 WU.

DISCUSSION

In this post hoc analysis from the REDUCE LAP-HF II trial, we show that the presence of latent PVD, defined by an exercise PVR ≥1.74 WU, appears to modify the treatment response to atrial shunt therapy in patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF. Patients with latent PVD defined by invasive exercise testing at the time of enrollment demonstrated an adverse response, with an increased HF event rate and poorer health status. Conversely, there was signal for clinical benefit with shunt therapy in patients without latent PVD. This differential response to treatment was specific to latent PVD uncovered by exercise testing and was not apparent from resting PVR. History of pacemaker implantation, presence of HFmrEF (vs HFpEF), and greater LA enlargement were found to be a markers of adverse response to the atrial shunt that were common to male sex and subjects with increased RA volume, the other two prespecified subgroups with differential treatment effects. These data further emphasize the clinical importance of latent PVD as a pathophysiologic phenotypic marker in HFpEF/HFmrEF and reinforce the value for exertional hemodynamic phenotyping to characterize patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF. These hypothesis-generating data also have important clinical implications for novel therapies under active investigation utilizing LA shunting devices and other procedures to treat patients with heart failure, suggesting that patients without latent PVD may respond more favorably to shunt therapy, calling for further study in this patient population.

In the overall REDUCE LAP-HF II trial, atrial shunt treatment had no effect on the hierarchical composite outcome or its individual components in patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF.10 However, in prespecified subgroup analyses, there was a significant treatment interaction observed for PASP during exercise at 20W workload (interaction p=0.002). Pulmonary artery pressure during exercise is determined by downstream LA pressure alone in patients with isolated postcapillary pulmonary hypertension, but in patients with PVD, PA pressures increase due to the combination of elevated LA pressure and high PVR. Pulmonary vascular disease may be apparent at rest, or it may be uncovered only during the stress of exercise.18

Patients with this form of “latent” PVD might be less expected to benefit from therapeutic atrial shunting, because the LA to RA pressure gradient would be minimized or potentially reversed as the right heart becomes more congested from RV dysfunction, resulting in less effective shunting. In addition, the flow and volume load on the right heart-pulmonary circuit could accelerate disease progression. For example, creation of a systemic shunt for hemodialysis access may lead to development of pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.14, 15 In natural history studies, roughly one-quarter of patients with HFpEF and normal RV function at baseline develop RV dysfunction over 4 years of follow up.16 Thus, applying a treatment that aggravates the flow and volume loading in a patient with a vulnerable right heart-pulmonary circulation (with latent PVD) may accelerate this progression.

For these reasons, patients with overt PVD, defined by elevations in resting PVR (>3.5 WU) were excluded from REDUCE LAP-HF II.9, 10 While this was an established cutpoint at the time of trial design, the present analyses suggest that this safety exclusion (in retrospect) was not sufficient to identify patients with latent PVD revealed through exercise testing. Indeed, a substantial minority of patients with HFpEF, even without PVR elevation at rest, display abnormalities in pulmonary vascular reserve that only become apparent during exercise as lung blood flow increases.17, 18, 24 This is manifest by failure to adequately reduce PVR, or in some cases even an increase in PVR.18 Patients with PVD have poorer exercise capacity, more severe impairments in RV function during exercise, and worse clinical outcomes.25, 26 Here we show that patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF and modestly elevated PVR during exercise are harmed by atrial shunt therapy. Importantly, these patients could only be identified using invasive hemodynamic exercise testing, as resting PVR did not predict treatment response and was not strongly correlated with exercise PVR.

Conversely, patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF and a more normal pulmonary vasculature may be better positioned to respond favorably to atrial shunt therapy. In health, the pulmonary circulation can accommodate 50% increases in blood volume and 300–500% increases in blood flow during exercise with minimal increase in pressure owing its remarkable capacity to enhance vascular recruitment, distention, and flow-mediated dilation.21, 27 Thus the ~25% increase in pulmonary blood flow that occurs following shunt treatment would be expected to be well-tolerated in such patients, allowing for beneficial effects related to PCWP reduction, potentially without the untoward effects on the pulmonary circulation and right heart. In a prior study evaluating longitudinal changes in pulmonary vascular function following shunt treatment, Obokata et al identified significant improvements in PVR and PA compliance, and patients with enhanced PA compliance experienced greater improvements in exercise capacity.13 However this study evaluated only short-term hemodynamic effects (1 or 6 months), did not evaluate clinical outcomes, and did not include a sham control.

There are not adequate data to indicate what a normal exercise PVR should be in older adults. PVR during exercise increases with normal aging. Van Empel and colleagues reported a mean PVR of 1.2±0.3 WU during exercise in adults without heart failure aged >55 years (n=20),23 which would correspond to an upper limit of normal of ~1.8 WU for exercise PVR. Wolsk et al. reported a similar point estimate for mean exercise PVR of 1.1 at 75% of peak exercise in healthy adults aged 60–80 years (n=20).28 For the present analysis, we utilized the partition value separating the second and third tertiles among participants in the trial, because patients falling in the bottom two tertiles responded in a similar fashion to atrial shunt (Table S1), and because this cutpoint is close to the upper limit of normal from the prior literature.23, 28 Latent or early-stage PVD is a more recently described entity,17, 18, 24 without an established hemodynamic definition, and we cannot exclude the possibility that other partition values to define it might provide superior discrimination of treatment response following shunt therapy. However, the purpose of this study was not to define a specific cutpoint for latent PVD, but rather to test the concept hypothesis that patients with and without latent PVD, defined by exercise PVR, would respond differentially to atrial shunt therapy.

Indeed, the present results may have important implications that extend beyond this trial. Besides the device studied in this trial, at least 7 other interatrial shunt devices and procedures are currently at various stages of development, including ongoing human trials.9, 29, 30 This post hoc analysis suggests that invasive hemodynamic exercise phenotyping may be required to exclude patients at risk for harm following shunt therapy. While further study is required, exercise phenotyping may also be helpful to identify patients likely to benefit from atrial shunt therapy. In clinical trials it is typically desirable to enroll patients at the highest risk for events to enable smaller sample sizes, but here we observed that patients with lower risk (no latent PVD) were the group more likely to derive benefit, indicating that this notion is not always correct. The present results also provide further evidence supporting the clinical importance of latent PVD as a mechanistically important phenogroup in patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF.18

At 12 months, patients with no latent PVD experienced significant increases in RA and RV volume following atrial shunt as compared to sham control. Normally right heart dilation is an adverse marker,16 but in this situation, it may simply reflect right heart volume loading from effective shunting, as there was no deterioration in RV function as measured by TAPSE. Conversely, patients with latent PVD displayed no statistically significant change in RA or RV volume, but LVEDV decreased following treatment with the shunt. In the first heartbeat following atrial shunt creation, LVEDV is reduced as the LA fills both the LV and the RA, but in the ensuing beats the shunted blood will traverse the lungs, restoring pulmonary venous inflow to the LA. If the pulmonary circulation (or right heart) cannot accommodate the increase in lung blood flow related to the shunt, this increase in LA venous return will be reduced, yet the shunt will still exist, and thus LV filling will decrease. Thus, the absence of right heart dilation and reduction in LVEDV in patients with latent PVD may both indicate inadequate offloading by the shunt, whereas the opposite changes may indicate successful shunt flow in patients without latent PVD.

Limitations

While a significant treatment effect interaction was observed in REDUCE LAP-HF II for the prespecified subgroups of PA systolic pressure at 20W workload, sex, and RA volume, the present analyses were performed post hoc. Health status as measured by the KCCQ is related to outcomes but there may be disconnects, but differential treatment responses in patients with and without latent PVD were consistently observed with both KCCQ and HF events. This internal consistency increases confidence in the veracity of the results. There was no repeat invasive hemodynamic testing performed in REDUCE LAP-HF II to examine effects on pulmonary vascular function which might explain differential responses observed. While clinical events were recorded out to 12–24 months following treatment, it is possible that differing effects may be observed with longer term follow up, as development of progressive PVD and right heart failure may evolve more slowly following atrial shunt such that they are not detected during the interval studied here. Future studies will provide new insights into longer-term effects, ideally with repeat hemodynamic assessments performed.

Conclusions

This post hoc analysis from the REDUCE-LAP HF II trial demonstrates that in patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF, latent PVD uncovered by invasive hemodynamic exercise testing appears to modify the therapeutic response to atrial shunt therapy. Patients with latent PVD have worse outcomes and symptoms in the setting of increased pulmonary blood flow following atrial shunt therapy. Conversely, patients without latent PVD may better accommodate the increase in lung blood flow and might be better positioned to derive benefit from shunt mediated LA unloading, though further study is required. These data have important implications for future trials utilizing atrial shunt devices and procedures to treat HF; they further emphasize the clinical importance of latent PVD as an important phenotypic marker in HFpEF; and they reinforce the importance of invasive hemodynamic exercise evaluation to characterize underlying pathophysiology in HFpEF/HFmrEF to individualize therapy.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective:

- What is new?

- In patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF, the presence of latent pulmonary vascular disease (PVD), defined by an elevated pulmonary vascular resistance during exercise, appears to modify the response to atrial shunt therapy.

- The presence of latent PVD was associated with adverse response to shunt treatment, whereas patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF without latent PVD may benefit.

- What are the clinical implications?

- Further study is indicated to confirm whether atrial shunt therapy may improve clinical outcomes in patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF without latent PVD.

- These data emphasize the importance of latent PVD as an important pathophysiologic and phenotypic marker in HFpEF/HFmrEF

- These data also reinforce the importance of hemodynamic exercise evaluation to characterize pathophysiology and individualize treatment in patients with HFpEF/HFmrEF.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who agreed to participate in the REDUCE LAP-HF II trial, allowing for this study to be completed.

Sources of Funding

The REDUCE LAP-HF II trial was funded by Corvia Medical, Inc.

Dr. Borlaug is also supported by R01 HL128526 and U01 HL160226, from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Dr. Shah is also supported by U54 HL160273, R01 HL107577, R01 HL140731, and R01 HL149423 from the NIH.

Dr. Hummel is also supported by R01 HL139813, R01 AG062582, and R61 HL155498 from the NIH and CARA-009-16F9050 from the Veterans Health Administration.

Prof Cleland is also supported by the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence (grant number RE/18/6/34217)

Prof Petrie is also supported by a British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence Grant RE/18/6/34217.

Disclosures

All authors received research grant funding from Corvia to support this study, except DSC. JM, DB and DSC have received personal consulting fees from Corvia, DSC is a shareholder in Corvia, and JK is employed by Corvia. BAB has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Medtronic, GlaxoSmithKline, Mesoblast, Novartis, Tenax Therapeutics, and consulting fees from Actelion, Amgen, Aria, Axon Therapies, Boehringer Ingelheim, Edwards Lifesciences, Eli Lilly, Imbria, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and VADovations. JGFC has received research grants from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Novartis, Pharmacosmos, Servier and Vifor Pharma, support for travel from Corvia, and consulting fees from Abbott and Boehringer Ingelheim. MCP has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, SQ Innovations, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Pharmacosmos and served on clinical trial committees for Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Astra Zeneca, Novo Nordisk, Abbvie, Bayer, Takeda, Cardiorentis, Pharmacosmos, Siemens, Vifor. SJS has received research grants from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Corvia, Novartis, and Pfizer; and consulting fees from Abbott, Actelion, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Aria CV, Axon Therapies, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardiora, Coridea, CVRx, Cyclerion, Cytokinetics, Edwards Lifesciences, Eidos, Eisai, Imara, Impulse Dynamics, Intellia, Ionis, Ironwood, Lilly, Merck, MyoKardia, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Prothena, Regeneron, Rivus, Sanofi, Shifamed, Tenax, Tenaya, and United Therapeutics. FG has received consulting fees from Abbott, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Ionis, Alnylam, Bayer and speaker’s fees from Orion Pharma, Novartis, Vifor, AstraZeneca. JNT has received research grants Novartis and Boston Scientific, and has received personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, ViforPharma. JAM has received research support from Actelion and Tenax Therapeutics, and consulting fees from Actelion, United Therapeutics, Acceleron. SRM has received research support from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Johnson and Johnson. AN has received consulting fees from Abiomed. AR has received speakers’ fees from AstraZeneca and Bayer and congress fees from Servier. HMB has received consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Abbreviations

- EF

ejection fraction

- HF

heart failure

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFmrEF

heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction

- KCCQ

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

- LA

left atrial

- LV

left ventricular

- LVEDV

left ventricular end diastolic volume

- OSS

overall summary score

- PA

pulmonary artery

- PASP

pulmonary artery systolic pressure

- PCWP

pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

- PVD

pulmonary vascular disease

- PVR

pulmonary vascular resistance

- RA

right atrial

- RV

right ventricular

- TAPSE

tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

- WU

Wood unit

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Barry A. Borlaug, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA,.

John Blair, University of Chicago.

Martin W Bergmann, Cardiologicum Hamburg, Germany.

Heiko Bugger, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria.

Dan Burkhoff, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York NY, USA.

Leonhard Bruch, BG Klinikum Unfallkrankenhaus, Berlin, Germany.

David S. Celermajer, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, The University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia.

Brian Claggett, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

John GF Cleland, Robertson Centre for Biostatistics and Glasgow Clinical Trials Unit, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, Glasgow, and National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College London, United Kingdom..

Donald E. Cutlip, Baim Clinical Research Institute, Boston, MA.

Ira Dauber, South Denver Cardiology Associates/Centura Health. Denver, CO, USA.

Jean-Christophe Eicher, CHU de Dijon-Hôpital Bocage Central, Dijon, France.

Qi Gao, Baim Clinical Research Institute, Boston, MA.

Thomas M. Gorter, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Finn Gustafsson, Rigshospitalet, University ofCopenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Chris Hayward, St. Vincents Hospital Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

Jan van der Heyden, AZ Sint-Jan Brugge-Oostende, Bruges, Belgium.

Gerd Hasenfuß, Heart Center, University Medical Center, Göttingen, Germany.

Scott L Hummel, University of Michigan, Ann Harbor, MI and VA Ann Arbor Health System, Ann Arbor, MI.

David M Kaye, Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia.

Jan Komtebedde, Corvia Medical Inc..

Joseph M. Massaro, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Jeremy A. Mazurek, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Scott McKenzie, Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia.

Shamir R. Mehta, McMaster University and Hamilton Health Sciences, Hamilton, Canada.

Mark C Petrie, University of Glasgow, Scotland..

Marco C. Post, Departments of Cardiology, St. Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein and University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Ajith Nair, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX.

Andreas Rieth, Kerckhoff Heart and Thoraxcenter, Bad Nauheim, Germany.

Frank E. Silvestry, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Scott D. Solomon, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Jean-Noël Trochu, Nantes Université, CHU Nantes, CNRS, INSERM, l’institut du thorax, F-44000 Nantes, France.

Dirk J. Van Veldhuisen, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Ralf Westenfeld, Division of Cardiology, Pulmonology, and Vascular Medicine Medical Faculty, Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany.

Martin B. Leon, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York NY, USA.

Sanjiv J. Shah, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL USA.

References

- 1.Shah SJ, Borlaug BA, Kitzman DW, McCulloch AD, Blaxall BC, Agarwal R, Chirinos JA, Collins S, Deo RC, Gladwin MT, et al. Research Priorities for Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group Summary. Circulation. 2020;141:1001–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borlaug BA. Evaluation and management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:559–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy YNV, Obokata M, Wiley B, Koepp KE, Jorgenson CC, Egbe A, Melenovsky V, Carter RE and Borlaug BA. The haemodynamic basis of lung congestion during exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2019;40 3721–3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obokata M, Olson TP, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Kane GC and Borlaug BA. Haemodynamics, dyspnoea, and pulmonary reserve in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2810–2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolsk E, Kaye D, Borlaug BA, Burkhoff D, Kitzman DW, Komtebedde J, Lam CSP, Ponikowski P, Shah SJ and Gustafsson F. Resting and exercise haemodynamics in relation to six-minute walk test in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:715–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy YNV, Olson TP, Obokata M, Melenovsky V and Borlaug BA. Hemodynamic Correlates and Diagnostic Role of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:665–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorfs S, Zeh W, Hochholzer W, Jander N, Kienzle RP, Pieske B, Neumann FJ. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure during exercise and long-term mortality in patients with suspected heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisman AS, Shah RV, Dhakal BP, Pappagianopoulos PP, Wooster L, Bailey C, Cunningham TF, Hardin KM, Baggish AL, Ho JE, et al. Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure Patterns During Exercise Predict Exercise Capacity and Incident Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11:e004750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry N, Mauri L, Feldman T, Komtebedde J, van Veldhuisen DJ, Solomon SD, Massaro JM, Shah SJ. Transcatheter InterAtrial Shunt Device for the treatment of heart failure: Rationale and design of the pivotal randomized trial to REDUCE Elevated Left Atrial Pressure in Patients with Heart Failure II (REDUCE LAP-HF II). Am Heart J. 2020;226:222–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah SJ, Borlaug BA, Chung ES, Cutlip DE, Debonnaire P, Fail PS, Hasenfuß G, Kahwash R, Kaye DM, Litwin SE, et al. Atrial Shunt Device for Heart Failure with Preserved and Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction (REDUCE-LAP HF II): A Randomised, Multicentre, Blinded, Sham-Controlled Trial. Lancet. 2022;in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaye D, Shah SJ, Borlaug BA, Gustafsson F, Komtebedde J, Kubo S, Magnin C, Maurer MS, Feldman T and Burkhoff D. Effects of an interatrial shunt on rest and exercise hemodynamics: results of a computer simulation in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2014;20:212–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman T, Mauri L, Kahwash R, Litwin S, Ricciardi MJ, van der Harst P, Penicka M, Fail PS, Kaye DM, Petrie MC, et al. Transcatheter Interatrial Shunt Device for the Treatment of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (REDUCE LAP-HF I [Reduce Elevated Left Atrial Pressure in Patients With Heart Failure]): A Phase 2, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial. Circulation. 2018;137:364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Shah SJ, Kaye DM, Gustafsson F, Hasenfuss G, Hoendermis E, Litwin SE, Komtebedde J, Lam C, et al. Effects of Interatrial Shunt on Pulmonary Vascular Function in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:2539–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy YNV, Obokata M, Dean PG, Melenovsky V, Nath KA and Borlaug BA. Long-term cardiovascular changes following creation of arteriovenous fistula in patients with end stage renal disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1913–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy YN, Melenovsky V, Redfield MM, Nishimura RA and Borlaug BA. High-Output Heart Failure: A 15-Year Experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:473–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Pislaru S and Borlaug BA. Deterioration in right ventricular structure and function over time in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:689–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borlaug BA, Kane GC, Melenovsky V and Olson TP. Abnormal right ventricular-pulmonary artery coupling with exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3293–3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borlaug BA and Obokata M. Is it time to recognize a new phenotype? Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction with pulmonary vascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2874–2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho JE, Zern EK, Lau ES, Wooster L, Bailey CS, Cunningham T, Eisman AS, Hardin KM, Farrell R, Sbarbaro JA, et al. Exercise Pulmonary Hypertension Predicts Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Dyspnea on Effort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaye DM, Hasenfuss G, Neuzil P, Post MC, Doughty R, Trochu JN, Kolodziej A, Westenfeld R, Penicka M, Rosenberg M, et al. One-Year Outcomes After Transcatheter Insertion of an Interatrial Shunt Device for the Management of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:pii: e003662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy YNV and Borlaug BA. Pulmonary Hypertension in Left Heart Disease. Clin Chest Med. 2021;42:39–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pocock SJ, Ariti CA, Collier TJ and Wang D. The win ratio: a new approach to the analysis of composite endpoints in clinical trials based on clinical priorities. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Empel VP, Kaye DM and Borlaug BA. Effects of healthy aging on the cardiopulmonary hemodynamic response to exercise. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:131–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang W, Oliveira RKF, Lei H, Systrom DM and Waxman AB. Pulmonary Vascular Resistance During Exercise Predicts Long-Term Outcomes in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Card Fail. 2017;24:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorter TM, Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V and Borlaug BA. Exercise unmasks distinct pathophysiologic features in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and pulmonary vascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2825–2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanderpool RR, Saul M, Nouraie M, Gladwin MT and Simon MA. Association Between Hemodynamic Markers of Pulmonary Hypertension and Outcomes in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flamm SD, Taki J, Moore R, Lewis SF, Keech F, Maltais F, Ahmad M, Callahan R, Dragotakes S and Alpert N. Redistribution of regional and organ blood volume and effect on cardiac function in relation to upright exercise intensity in healthy human subjects. Circulation. 1990;81:1550–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolsk E, Bakkestrom R, Thomsen JH, Balling L, Andersen MJ, Dahl JS, Hassager C, Moller JE and Gustafsson F. The Influence of Age on Hemodynamic Parameters During Rest and Exercise in Healthy Individuals. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffin JM, Borlaug BA, Komtebedde J, Litwin SE, Shah SJ, Kaye DM, Hoendermis E, Hasenfuss G, Gustafsson F, Wolsk E, et al. Impact of Interatrial Shunts on Invasive Hemodynamics and Exercise Tolerance in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fudim M, Abraham WT, von Bardeleben RS, Lindenfeld J, Ponikowski PP, Salah HM, Khan MS, Sievert H, Stone GW, Anker SD et al. Device Therapy in Chronic Heart Failure: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:931–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.