Abstract

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease that causes several clinical manifestations. Parasites of the genus Leishmania cause this disease. Spread across five continents, leishmaniasis is a particular public health problem in developing countries. Leishmania infects phagocytic cells such as macrophages, where it induces adenosine triphosphate (ATP) release at the time of infection. ATP activates purinergic receptors in the cell membranes of infected cells and promotes parasite control by inducing leukotriene B4 release and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Moreover, uridine triphosphate induces ATP release, exacerbating the immune response. However, ATP may also undergo catalysis by ectonucleotidases present in the parasite membrane, generating adenosine, which activates P1 receptors and induces the production of anti-inflammatory molecules such as prostaglandin E2 and IL-10. These mechanisms culminate in Leishmania's survival. Thus, how Leishmania handles extracellular nucleotides and the activation of purinergic receptors determines the control or the dissemination of the disease.

Keywords: Purinergic signaling, Leishmaniasis, Innate immune response, Evasion

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease found in almost 100 countries worldwide. It affects 12 million people globally, and about 1.5–2 million new cases are reported annually [1,2]. Leishmaniasis is the second-leading cause of death related to parasite infections, causing 20,000 to 30,000 deaths per year [3]. This parasitic disease can be generated by at least 20 different protozoan species belonging to the family Trypanosomatidae, order Kinetoplastida, and genus Leishmania. Three clinical manifestations depend on the Leishmania species, ranging from self-healing cutaneous lesions and mucosal tissue damage to life-threatening visceral disease. Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) manifests primarily in the infectious site with self-resolving lesions; however, mucosal damage often occurs. In some cases, more severe variants of CL may occur, including diffuse or disseminated CL [4]. Some Leishmania species may localize in nasal and oropharyngeal mucosa sites, where they cause mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. The parasites also can migrate to the spleen, liver, and bone marrow, leading to fatal visceral leishmaniasis (VL) [5].

Leishmania spp. are transmitted by the bite of female vectors called sand flies, genus Phlebotomus and Lutzomyia, transmitters of Old World and New World disease, respectively [2]. The parasites exist in two forms during their life cycle: flagellar promastigotes, found in the vector's midgut, and amastigotes, mandatory intracellular forms found within phagolysosomes of phagocytic cells in the vertebrate host [6]. Infected sand flies bite the mammalian host during blood-feeding and regurgitate the infectious forms, called metacyclic promastigotes, into the dermis [7]. Leishmania parasites infect phagocytic cells present in the skin, mainly neutrophils and dermis-resident macrophages, in the first hour post-transmission [8]. The phagocytosed promastigote differentiates in amastigote form approximately 12–24 h later [9]. The Leishmania life cycle continues when the vector aspirates amastigote-infected cells or free parasites. Aflagellate amastigotes become virulent and non-proliferative metacyclic promastigotes in the vector's digestive tract [10].

Currently, leishmaniasis treatment is a challenge for researchers and physicians. Researchers struggle to develop vaccines for humans and domestic reservoirs such as dogs. Medications for treating leishmaniasis are toxic and generate drug resistance [11]. Thus, new therapeutic strategies are vital for leishmaniasis management. In this effort, the elucidation of immune response is critical to the identification of new therapeutic targets.

Innate immune system cells present in the dermis, including dendritic cells (DC) and dermis-resident macrophages (DRMs), are the first line of defense against Leishmania [12,13]. After the infected vector injects the parasite into the dermis, neutrophils are quickly recruited to the infection site, promoting phagocytosis and becoming the first circulating cells to reach the infected tissue [9,14]. Recently, a population of DRMs was identified whose main characteristic is the expression of high levels of mannose receptor. In addition, these cells do not have progenitors from bone marrow, and IL-4 maintains them derived mainly from eosinophils in the skin. This inflammatory environment is required for DRM proliferation and maintenance of its M2-like phenotype [15,16]. DRMs are the first cells to become infected after transmission; they are the main target for infection and a niche for Leishmania major proliferation [9,15,17].

On the other hand, neutrophils can promote resistance to infection by some Leishmania species. During infection by Leishmania donovani, neutrophil depletion increased the parasitic burden in mice [18]. When obtained from Leishmania amazonensis-infected mice, neutrophils could release NETs, which helped prevent the parasite from spreading [19]. A previous study showed the importance of leukotriene B4 (LTB4) in the control of L. amazonensis infection [20]. Macrophages release LTB4 when infected with the parasites, and this mediator induces neutrophil recruitment [21,22]. The interaction between neutrophils and macrophages is relevant in the context of leishmaniasis. The essential role of neutrophils in the persistence of L. major infection is because these cells act as a “Trojan Horse.” In this model, neutrophils infected by L. major undergo apoptosis and silently enter macrophages, deactivating these cells [8,23] and favoring infection.

Macrophages and neutrophils have pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) activated by molecular patterns associated with pathogens (PAMPs) expressed on the Leishmania cell surface. The most well-known PAMPs present on Leishmania are lipophosphoglycan and glycoprotein 63, both in humans and mice [[24], [25], [26]]. One of the most well-known PRRs is Toll-like (TLR) receptors. The activation of TLRs was associated with the production and release of inflammatory mediators by macrophages and neutrophils, such as cytokines, lipid mediators, and adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) [27,28].

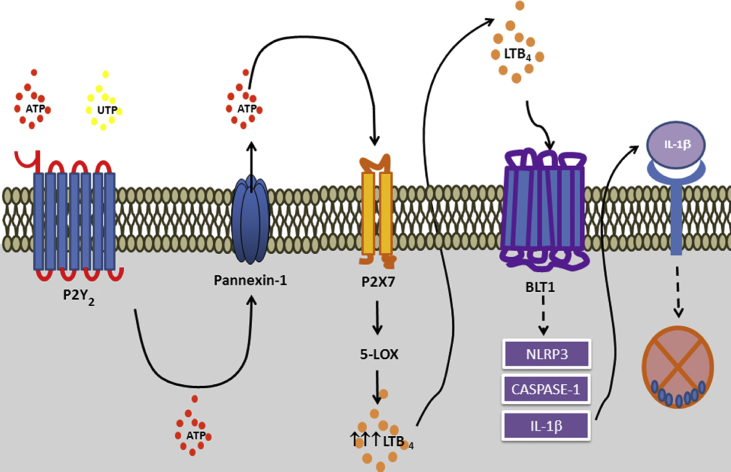

ATP and other nucleotides are released through both specific and non-specific mechanisms [29]. Nucleotides may be released from live cells in a non-regulated pathway in response to various cell stress conditions, including exposure to cytotoxic agents, hypoxia, or plasma membrane damage [30]. During the inflammatory response, cell membrane disruption can lead to a non-specific release of large amounts of nucleotides. In the extracellular environment, ATP is practically non-existent; under physiological conditions, the extracellular ATP concentration is approximately 10 nM. By contrast, ATP is present in high concentrations in the intracellular space, ranging from 3 to 10 mM [31]. Ion channels in the cell surface, such as pannexin (Panx), may regulate ATP release in healthy cells and consequently participate in several physiologic and pathologic processes in various cell types and tissues [32]. Three forms of Panx have been described in vertebrates, including Panx1, expressed in various tissues and cells, Panx2 expressed in the central nervous system, and Panx3 primarily present in the skin and bone [33,34]. Interestingly, lipopolysaccharide was shown to induce ATP release via Panx in a TLR activation-dependent manner [35]. TLRs are also crucial to Leishmania infection [36], and we found that L. amazonensis phagocytosis by macrophages induced ATP secretion [22], suggesting possible participation of TLR in ATP release during Leishmania infection [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1.

P2Y2and P2X7 receptor cooperation favoring control of Leishmania infection. Leishmania infection induces P2Y2 and P2X7 overexpression. Extracellular ATP and UTP activate the P2Y2 receptor. The activation of the P2Y2 receptor potentiates ATP release via Panx-1 channels. High levels of ATP in the extracellular media culminate in activating the enzyme 5-LO and consequent LTB4 production and release. Then, LTB4 acts in the extracellular environment to activate the leukotriene B4 receptor 1 receptor that further induces NLRP3 activation and IL-1β secretion, promoting Leishmania infection control.

When in the extracellular media, nucleotides are signaling molecules that activate P2 receptors. The low concentrations of ATP in the extracellular media are maintained by enzymes that rapidly metabolize ATP to adenosine, called ectonucleotidases. These enzymes consist of four large families of ectoenzymes that include ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (i.e., NTPDase1/CD39), alkaline phosphatases, and ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) [37]. The adenosine formed by the action of these enzymes is known to activate P1 receptors [37].

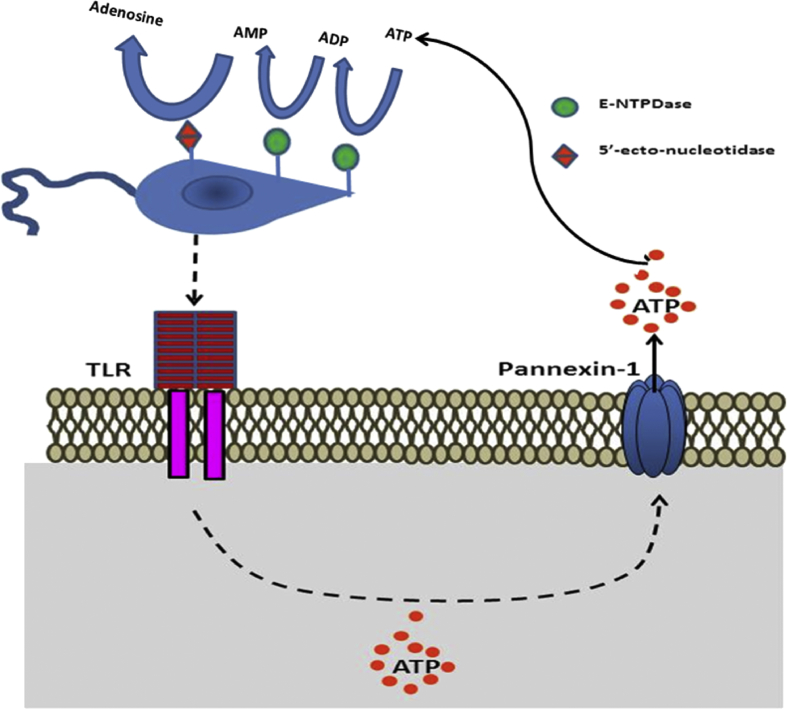

The role of purinergic signaling in leishmaniasis has been explored over the last two decades [[38], [39], [40]]. Phagocytosis of L. amazonensis by macrophages induces the release of ATP into the extracellular space [22]. Once released, ATP and other nucleotides activate microbicidal mechanisms via P2 receptors. These nucleotides can also be degraded by ectoenzymes generating adenosine, which has anti-inflammatory effects. In this review, we discuss the role of purinergic signaling in leishmaniasis, highlighting mechanisms that contribute to parasite control and contribute to a better understanding of the infection physiology [see Fig. 2].

Fig. 2.

Leishmania infection culminates in nucleotide release. Leishmania spp. is recognized by TLRs in the membrane of the host cell. The binding of parasites to these receptors induces ATP release to the extracellular environment through pannexin-1 channels. Once in the extracellular medium, ATP can be metabolized by ectonucleotidases such as ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase and ecto-5′-nucleotidase present in the Leishmania membrane, leading to Ado accumulation in the extracellular medium.

P2 receptors and leishmaniasis

The family of P2 receptors is expressed in almost all cells in the body [41]. This family of receptors is subdivided into P2X and P2Y. The P2Y receptor family includes metabotropic G-coupled protein receptors. These receptors have seven transmembrane domains [Fig. 1A], and eight members have been cloned in mammals: P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11, P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14 [42]. P2Y receptors can be differentiated according to the type of G-coupled protein: while P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, and P2Y11 receptors bind to Gq protein, P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14 receptors are linked to Gi protein. The P2Y11 receptor, on the other hand, can bind both Gq and Gs proteins, being the only one with this capacity [42]. The family of P2Y receptors triggers cellular events such as activation and differentiation of human pro-monocytic cells [43]. They also mediate the production of IL-8 in inflammatory bowel diseases [44]. Moreover, P2Y receptors are involved in chemotaxis and phagocytosis of macrophages [45,46], chemotaxis of neutrophils [47], and the clearance of damaged and apoptotic cells [48].

P2X are ionotropic receptors that form non-selective cationic channels permeable to Na+, K+, and Ca2+. Seven subtypes of the P2X family have been cloned: P2X1 to P2X7. The P2X5 receptor subtype is an exception, being permeable to Cl− [49]. The most studied of the P2X receptors is the P2X7 subtype. Their activation leads to the opening of non-selective pores in the cell membrane, allowing the passage of molecules up to 900 Da [50]. In addition, as a consequence of P2X7 receptor activation, several cellular mechanisms are triggered, including apoptosis, exosome release, and cytokine secretion (i.e., IL-1β and IL-18), along with inflammatory lipid mediators such as LTB4 [22,49,51]. P2X7 also triggers the activation of microbicidal mechanisms, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) production [40]. Thus, the relevance of the P2X7 receptor in the control of several diseases caused by protozoan parasites has already been demonstrated [52]. Polymorphisms in the P2X7 receptor gene have also been associated with susceptibility to certain infectious diseases [53].

The importance of extracellular nucleotides and the activation of purinergic receptors during infection by Leishmania has been characterized [38,52]. ATP can lead to the elimination of L. amazonensis in infected macrophages via the P2X7 receptor, with an increased expression and functionality of this receptor during in vitro infection [54]. ATP controls L. amazonensis infection by activating the P2X7 receptor, which induces the release of LTB4 in peritoneal macrophages [22]. In addition, P2X7-deficient mice are more susceptible to L. amazonensis infection [54]. The absence of P2X7 receptor during L. amazonensis infection resulted in higher IFN-γ and IL10 levels and lower IL-12p40, IL-4, IL-17, and TGF-β levels than in wild-type animals [54]. These data suggest that the lack of P2X7 receptors in L. amazonensis-infected mice causes intense inflammation associated with a Th1 response.

The P2X7 receptor is a well-known second signal for the full activation of inflammasome NLRP3, culminating in the conversion of pro-caspase-1 to its active form [55,56]. The caspase-1 enzyme is involved in the processing and release of cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18, with subsequent systemic effects on the immune system. NLRP3 inflammasome assembly is essential for initiating and progressing inflammatory responses by activating macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells [57]. Moreover, inflammasome activation plays an essential role during intracellular protozoa infections, including leishmaniasis [58]. Lima-Junior and collaborators (2013) demonstrated the role of NLRP3 in inflammasome and NO production in the control of CL [59]. Furthermore, NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β have crucial roles in the visceralization of L. donovani soon after transmission by the natural vector [60]. Based on these findings, several reports demonstrated the ability of Leishmania to inhibit or evade NLRP3 inflammasome expression and activation [61,62]. Recently, we found that L. amazonensis infection control via P2X7 receptor and LTB4 release depends on NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-11 activation [63] [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3.

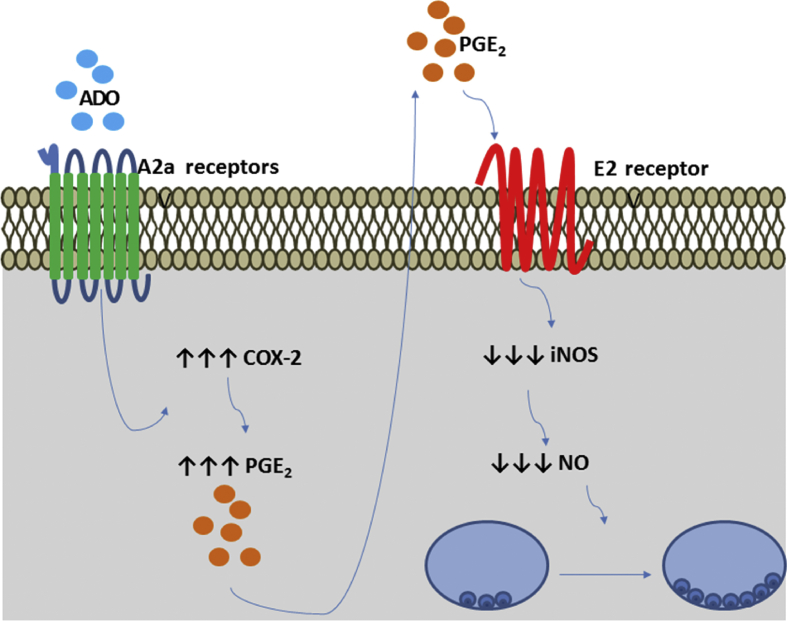

P1 receptor activation and Leishmania survival. Ado actives A2A receptors in the membranes of host cells. The activation of A2A receptors induces COX-2 expression and consequent production and release of PGE2 to the extracellular environment. PGE2 activates prostaglandin E2 receptors in an autocrine or paracrine manner, leading to the decrease of iNOS expression and NO production, resulting in the growth and establishment of Leishmania spp. Infection.

In addition to P2X receptors, P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptors are overexpressed and upregulated during infection. Uridine triphosphate (UTP) in the extracellular media can induce apoptosis of infected macrophages and, consequently, eliminate the parasite [64]. The role of UTP was also described in vivo during L. amazonensis infection, shifting the immune responses to a Th1 profile and increasing host resistance via ROS production [39]. Subsequential studies revealed that P2Y2 and P2X7 receptors cooperate to trigger potent innate immune responses against L. amazonensis infection, which involves Panx-1 and LTB4 release [65] [Fig. 3]. Activation of P2Y receptor by UTP induced ATP release with consequent P2X7 receptor activation and NLRP3 inflammasome assembly [66].

Ectonucleotidases and leishmaniasis

The ectonucleotidases play significant roles in nucleotide metabolism, preventing interaction of nucleotides with their receptors and consequent activation of the immune system and inflammation in mammals. NTPDases modulate ATP degradation. Several subtypes have already been described: NTPDase 1, 2, 3, and 8 are expressed on the cell surface, NTPDase 4, 5, 6, and 7 are located inside cells [67]. These enzymes possess different catalytic properties: NTPDase 1 or CD39 hydrolyzes ATP and adenosine diphosphate equally, while NTPDase 2, 3, and 8 have ATP as the preferential substrate [68].

CD73/ecto-5′-nucleotidase hydrolyzes 5′-adenosine monophosphate, generating adenosine (Ado) and inorganic phosphate [69]. Ado may be regulated by adenosine deaminase, which modulates adenosine levels by deaminating this nucleoside into inosine [37].

The principal member of the NTPDase family in mammals is CD39; its role is to limit ATP concentrations in the extracellular medium and catalysis of ATP to ADP and ADP to AMP, subsequently converted into Ado by CD73 [37]. Outside cells, Ado has a half-life of a few seconds and can activate P1 purinergic receptors [39]. In humans, CD39 and CD73 are constitutively expressed in innate and adaptive immune cells such as monocytes, granulocytes, B-cells, and T-cell subsets [70]; it activates predominantly anti-inflammatory responses.

However, NTPDases were not described only in mammals. Several species of Trypanossomatides, including Leishmania, including Leishmania infantum, Leishmania braziliensis, L. donovani, Leishmania mexicana, L. major, L. amazonensis, and Leishmania tropica, express two predicted NTPDases [71,72]. Ecto-ATPase activity was demonstrated in L. amazonensis, L. tropica, and L. infantum [[72], [73], [74]] [Fig. 1].

L. amazonensis infection increases the number of CD39+CD73+ DC with consequent deactivation of these cells, promoting the establishment of the disease [75]. In L. donovani and L. infantum infections, ectonucleotidase inhibition in host cells decreased parasite survival and increased host-favorable cytokine production [76,77]. These findings demonstrated the role of these enzymes in Leishmania infection pathophysiology. These findings also corroborate the observation that patients with VL showed higher serum Ado levels than healthy individuals [78], suggesting that Ado is an essential regulator in VL.

Moreover, sandfly saliva exhibits ATPase activity which can hydrolyze ATP [79]. This saliva possesses high levels of Ado which modulates the inflammatory microenvironment in the skin, causing NO inhibition and macrophage inactivation, consequently favoring parasitic growth in host cells such as macrophages and neutrophils [80,81].

P1 receptors and leishmaniasis

Ado is an agonist for the P1 receptor family that includes four metabotropic receptors. All are G-coupled protein receptors, named A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 [82]. Depending on the type of G-protein, these receptors are coupled and can generate inhibitory or stimulatory effects concerning the production of cyclic AMP (cAMP). The activation of A1 and A3 has inhibitory effects via Gi/Go, and Gi/Gq proteins, respectively. By contrast, A2A and A2B receptors stimulate cAMP production and activate adenylate cyclase via Gs and Gs/Gq, respectively [82,83]. Moreover, the activation of A2B receptors may also induce phospholipase C activation via Gq [83] [Table 1]. In general, the activation of P1 receptors can generate several effects, including inflammatory reactions [83,84].

Table 1.

Adenosine receptor signaling and leishmaniasis.

| Adenosine receptor | G-coupled protein | Second messengers | Effector enzymes | Effect in leishmaniasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2A | Gs → ↑Adenylate cyclase | cAMP↑ | ↑PKA | Favors leishmaniasis [95] |

| A2B | Gs → ↑Adenylate cyclase | cAMP↑ | ↑PKA | Favors leishmaniasis [96] |

| Gq → ↑ PLCγ | IP3 + DG | ↑PKC | ||

| A1 | Gi → Ø Adenylate cyclase | cAMP↓ | Ø PKA | Unknown |

| Go → ↑PLCβ | IP3 + DG | ↑PKC | ||

| A3 | Gi → Ø Adenylate cyclase | cAMP↓ | Ø PKA | Unknown |

| Gq → ↑PLCγ | IP3 + DG | ↑PKA |

Abbreviations: PLC: Phospholipase C; IP3: Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; DG: Diacylglycerol; PKA: Protein kinase A; PKC; Protein kinase C; Ø: inhibition.

Ado possesses immunosuppressive properties; it suppresses M1 macrophage functions and favors polarization to the M2 phenotype [85]. In addition, the activation of Ado receptors may impair the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages [86].

Macrophages produce nitric NO through inducible NO synthase (iNOS) with an anti-leishmanial effect [87]. Interestingly, Ado can negatively regulate the release of NO by impairing the expression of iNOS [88]. Moreover, A2B receptor signaling prevents IFN-γ production by Th1 cells and, consequently, IFNγ-induced macrophage activation [89]. L. infantum can subvert the host response by inducing A2A receptor signaling to promote the establishment of the infection [90] [Fig. 3]. Moreover, A2B receptor activation can impair DC activation [91]. The anti-inflammatory effects of PGs have been demonstrated during the resolution phase of inflammation [92] [Fig. 3]. PGE2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory responses and allows Leishmania establishment [93,94]. PGE2 impairs nitric oxide synthase expression and, consequently, downregulates NO production [92,95], combining with PGE2 to favor infection [Fig. 3]. These findings suggest that Ado may induce the formation of an anti-inflammatory environment that facilitates the parasite growth and consequent establishment of infection.

Conclusion

In summary, studies of purinergic signaling during Leishmania infection are crucial for understanding the disease's resistance and susceptibility. Consequently, new therapeutic methods could be developed using these mechanisms. As described here, the parasites have developed strategies to evade control pathways. The host triggers the purinergic signaling as an attempt to eradicate the parasite. P2 receptors, when activated during infection, stimulate the production and release of several microbicidal molecules. However, to perpetuate itself, Leishmania built pathways that can prevent its death, using purinergic mechanisms such as ectonucleotidase overexpression and P1 receptor activation.

In this context, the development or discovery of specific P2Y2 or P2X7 agonists could contribute to parasite control boosting the immune response in leishmaniasis. Interestingly, natural compounds have been explored as modulators of P2 receptors [96,97]. Clemastine fumarate, a synthetic ethanolamine that potentially acts as a P2X7 receptor positive allosteric modulator, showed antileishmanial effects [98]. Diquafosol (INS365), a P2Y2 agonist, has already been approved as a topical treatment for dry-eye disease could be repurposed for cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment [99]. In addition to P2 agonists, the administration of CD39/CD73 inhibitors or neutralizing antibodies that limit adenosine generation could also be an interesting approach to inhibit parasite growth in host cells [70]. Finally, adenosine A2A and A2B antagonists could also inhibit the formation of an immunosuppressive environment that contributes to parasite spreading, as previously proposed for the treatment of some types of cancer [70].

Development of more severe forms of leishmaniasis and even asymptomatic disease may be caused by host defect in the signaling triggered by the purinergic receptor; nevertheless, this has not yet been demonstrated in Leishmania-infected patients and would be of great importance for understanding the disease and its worsening. Such processes have been shown to occur in other infections, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis that causes tuberculosis [53].

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo - FAPESP (2018/14398-0), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnológico do Brasil – CNPq (306839/2019-9) RCS and (305857/2020-7) LEBS. Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro - FAPERJ (E-26/202.701/2019 and E-26/010.002260/2019 to LEBS; E-26/010.002985/2014, E-26/010.101036/2018 and E-26/202.774/2018 to RCS).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Contributor Information

Luiz Eduardo Savio, Email: savio@biof.ufrj.br.

Robson Coutinho-Silva, Email: rcsilva@biof.ufrj.br.

References

- 1.Burza S., Croft S.L., Boelaert M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2018;392:951–970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steverding D. The history of leishmaniasis. Parasites Vectors. 2017;10:82. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2028-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvar J., Croft S.L., Kaye P., Khamesipour A., Sundar S., Reed S.G. Case study for a vaccine against leishmaniasis. Vaccine. 2013;31:B244–B249. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Griensven J., Carrillo E., Lopez-Velez R., Lynen L., Moreno J. Leishmaniasis in immunosuppressed individuals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:286–299. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray H.W., Berman J.D., Davies C.R., Saravia N.G. Advances in leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2005;366:1561–1577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunter J., Gull K. Shape, form, function and Leishmania pathogenicity: from textbook descriptions to biological understanding. Open Biol. 2017;7:170165. doi: 10.1098/rsob.170165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates P.A. Revising Leishmania's life cycle. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:529–530. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaves M.M., Lee S.H., Kamenyeva O., Ghosh K., Peters N.C., Sacks D. The role of dermis resident macrophages and their interaction with neutrophils in the early establishment of Leishmania major infection transmitted by sand fly bite. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courret N., Frehel C., Prina E., Lang T., Antoine J.C. Kinetics of the intracellular differentiation of Leishmania amazonensis and internalization of host MHC molecules by the intermediate parasite stages. Parasitology. 2001;122:263–279. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001007387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.da Silva R., Sacks D.L. Metacyclogenesis is a major determinant of Leishmania promastigote virulence and attenuation. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2802–2806. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2802-2806.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Croft S.L., Sundar S., Fairlamb A.H. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111–126. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.111-126.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feijo D., Tiburcio R., Ampuero M., Brodskyn C., Tavares N. Dendritic cells and Leishmania infection: adding layers of complexity to a complex disease. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:3967436. doi: 10.1155/2016/3967436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Locksley R.M., Heinzel F.P., Fankhauser J.E., Nelson C.S., Sadick M.D. Cutaneous host defense in leishmaniasis: interaction of isolated dermal macrophages and epidermal Langerhans cells with the insect-stage promastigote. Infect Immun. 1988;56:336–342. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.336-342.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters N.C., Egen J.G., Secundino N., Debrabant A., Kimblin N., Kamhawi S., et al. In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science. 2008;321:970–974. doi: 10.1126/science.1159194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S.H., Charmoy M., Romano A., Paun A., Chaves M.M., Cope F.O., et al. Mannose receptor high, M2 dermal macrophages mediate nonhealing Leishmania major infection in a Th1 immune environment. J Exp Med. 2018;215:357–375. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S.H., Chaves M.M., Kamenyeva O., Gazzinelli-Guimaraes P.H., Kang B., Pessenda G., et al. M2-like, dermal macrophages are maintained via IL-4/CCL24-mediated cooperative interaction with eosinophils in cutaneous leishmaniasis. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eaaz4415. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavin Y., Winter D., Blecher-Gonen R., David E., Keren-Shaul H., Merad M., et al. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell. 2014;159:1312–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFarlane E., Perez C., Charmoy M., Allenbach C., Carter K.C., Alexander J., et al. Neutrophils contribute to development of a protective immune response during onset of infection with Leishmania donovani. Infect Immun. 2008;76:532–541. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01388-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guimaraes-Costa A.B., Nascimento M.T., Froment G.S., Soares R.P., Morgado F.N., Conceicao-Silva F., et al. Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes induce and are killed by neutrophil extracellular traps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6748–6753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900226106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serezani C.H., Perrela J.H., Russo M., Peters-Golden M., Jancar S. Leukotrienes are essential for the control of Leishmania amazonensis infection and contribute to strain variation in susceptibility. J Immunol. 2006;177:3201–3208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sampson S.E., Costello J.F., Sampson A.P. The effect of inhaled leukotriene B4 in normal and in asthmatic subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1789–1792. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaves M.M., Marques-da-Silva C., Monteiro A.P., Canetti C., Coutinho-Silva R. Leukotriene B4 modulates P2X7 receptor-mediated Leishmania amazonensis elimination in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2014;192:4765–4773. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Zandbergen G., Klinger M., Mueller A., Dannenberg S., Gebert A., Solbach W., et al. Cutting edge: neutrophil granulocyte serves as a vector for Leishmania entry into macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;173:6521–6525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isnard A., Shio M.T., Olivier M. Impact of Leishmania metalloprotease GP63 on macrophage signaling. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:72. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawai T., Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spath G.F., Garraway L.A., Turco S.J., Beverley S.M. The role(s) of lipophosphoglycan (LPG) in the establishment of Leishmania major infections in mammalian hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9536–9541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530604100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen P. The TLR and IL-1 signalling network at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:2383–2390. doi: 10.1242/jcs.149831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren H., Teng Y., Tan B., Zhang X., Jiang W., Liu M., et al. Toll-like receptor-triggered calcium mobilization protects mice against bacterial infection through extracellular ATP release. Infect Immun. 2014;82:5076–5085. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02546-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dosch M., Gerber J., Jebbawi F., Beldi G. Mechanisms of ATP release by inflammatory cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1222. doi: 10.3390/ijms19041222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martins I., Wang Y., Michaud M., Ma Y., Sukkurwala A.Q., Shen S., et al. Molecular mechanisms of ATP secretion during immunogenic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:79–91. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trautmann A. Extracellular ATP in the immune system: more than just a “danger signal”. Sci Signal. 2009;2:pe6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.256pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahl G. ATP release through pannexon channels. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:20140191. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baranova A., Ivanov D., Petrash N., Pestova A., Skoblov M., Kelmanson I., et al. The mammalian pannexin family is homologous to the invertebrate innexin gap junction proteins. Genomics. 2004;83:706–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruzzone R., Hormuzdi S.G., Barbe M.T., Herb A., Monyer H. Pannexins, a family of gap junction proteins expressed in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13644–13649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233464100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silberfeld A., Chavez B., Obidike C., Daugherty S., de Groat W.C., Beckel J.M. LPS-mediated release of ATP from urothelial cells occurs by lysosomal exocytosis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39:1321–1329. doi: 10.1002/nau.24377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halliday A., Bates P.A., Chance M.L., Taylor M.J. Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) plays a role in controlling cutaneous leishmaniasis in vivo, but does not require activation by parasite lipophosphoglycan. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:532. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1807-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yegutkin G.G. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaves M.M., Canetti C., Coutinho-Silva R. Crosstalk between purinergic receptors and lipid mediators in leishmaniasis. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:489. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1781-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marques-da-Silva C., Chaves M.M., Thorstenberg M.L., Figliuolo V.R., Vieira F.S., Chaves S.P., et al. Intralesional uridine-5'-triphosphate (UTP) treatment induced resistance to Leishmania amazonensis infection by boosting Th1 immune responses and reactive oxygen species production. Purinergic Signal. 2018;14:201–211. doi: 10.1007/s11302-018-9606-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coutinho-Silva R., Savio L.E.B. Purinergic signalling in host innate immune defence against intracellular pathogens. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;187:114405. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burnstock G. Purine and pyrimidine receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1471–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobson K.A., Delicado E.G., Gachet C., Kennedy C., von Kugelgen I., Li B., et al. Update of P2Y receptor pharmacology: IUPHAR Review 27. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:2413–2433. doi: 10.1111/bph.15005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santiago-Perez L.I., Flores R.V., Santos-Berrios C., Chorna N.E., Krugh B., Garrad R.C., et al. P2Y(2) nucleotide receptor signaling in human monocytic cells: activation, desensitization and coupling to mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:196–208. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khine A.A., Del Sorbo L., Vaschetto R., Voglis S., Tullis E., Slutsky A.S., et al. Human neutrophil peptides induce interleukin-8 production through the P2Y6 signaling pathway. Blood. 2006;107:2936–2942. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kronlage M., Song J., Sorokin L., Isfort K., Schwerdtle T., Leipziger J., et al. Autocrine purinergic receptor signaling is essential for macrophage chemotaxis. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra55. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koizumi S., Shigemoto-Mogami Y., Nasu-Tada K., Shinozaki Y., Ohsawa K., Tsuda M., et al. UDP acting at P2Y6 receptors is a mediator of microglial phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;446:1091–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature05704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y., Corriden R., Inoue Y., Yip L., Hashiguchi N., Zinkernagel A., et al. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elliott M.R., Chekeni F.B., Trampont P.C., Lazarowski E.R., Kadl A., Walk S.F., et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.North R.A. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coutinho-Silva R., Persechini P.M. P2Z purinoceptor-associated pores induced by extracellular ATP in macrophages and J774 cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1793–C1800. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.6.C1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Savio L.E.B., de Andrade Mello P., da Silva C.G., Coutinho-Silva R. The P2X7 receptor in inflammatory diseases: angel or demon? Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:52. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Savio L.E.B., Coutinho-Silva R. Immunomodulatory effects of P2X7 receptor in intracellular parasite infections. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019;47:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chaudhary A., Singh J.P., Sehajpal P.K., Sarin B.C. P2X7 receptor polymorphisms and susceptibility to tuberculosis in a North Indian Punjabi population. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis. 2018;22:884–889. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.18.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Figliuolo V.R., Chaves S.P., Savio L.E.B., Thorstenberg M.L.P., Machado Salles E., Takiya C.M., et al. The role of the P2X7 receptor in murine cutaneous leishmaniasis: aspects of inflammation and parasite control. Purinergic Signal. 2017;13:143–152. doi: 10.1007/s11302-016-9544-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kahlenberg J.M., Dubyak G.R. Mechanisms of caspase-1 activation by P2X7 receptor-mediated K+ release. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C1100–C1108. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00494.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marinho Y., Marques-da-Silva C., Santana P.T., Chaves M.M., Tamura A.S., Rangel T.P., et al. MSU Crystals induce sterile IL-1beta secretion via P2X7 receptor activation and HMGB1 release. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2020;1864:129461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.129461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sutterwala F.S., Ogura Y., Zamboni D.S., Roy C.R., Flavell R.A. NALP3: a key player in caspase-1 activation. J Endotoxin Res. 2006;12:251–256. doi: 10.1177/09680519060120040701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zamboni D.S., Sacks D.L. Inflammasomes and Leishmania: in good times or bad, in sickness or in health. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019;52:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lima-Junior D.S., Costa D.L., Carregaro V., Cunha L.D., Silva A.L., Mineo T.W., et al. Inflammasome-derived IL-1beta production induces nitric oxide-mediated resistance to Leishmania. Nat Med. 2013;19:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm.3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dey R., Joshi A.B., Oliveira F., Pereira L., Guimaraes-Costa A.B., Serafim T.D., et al. Gut microbes egested during bites of infected sand flies augment severity of leishmaniasis via inflammasome-derived IL-1beta. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.002. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lecoeur H., Prina E., Rosazza T., Kokou K., N'Diaye P., Aulner N., et al. Targeting macrophage histone H3 modification as a Leishmania strategy to dampen the NF-kappaB/NLRP3-Mediated inflammatory response. Cell Rep. 2020;30:1870–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.030. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gupta A.K., Ghosh K., Palit S., Barua J., Das P.K., Ukil A. Leishmania donovani inhibits inflammasome-dependent macrophage activation by exploiting the negative regulatory proteins A20 and UCP2. Faseb J. 2017;31:5087–5101. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700407R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chaves M.M., Sinflorio D.A., Thorstenberg M.L., Martins M.D.A., Moreira-Souza A.C.A., Rangel T.P., et al. Non-canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1beta signaling are necessary to L. amazonensis control mediated by P2X7 receptor and leukotriene B4. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marques-da-Silva C., Chaves M.M., Chaves S.P., Figliuolo V.R., Meyer-Fernandes J.R., Corte-Real S., et al. Infection with Leishmania amazonensis upregulates purinergic receptor expression and induces host-cell susceptibility to UTP-mediated apoptosis. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:1410–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thorstenberg M.L., Rangel Ferreira M.V., Amorim N., Canetti C., Morrone F.B., Alves Filho J.C., et al. Purinergic cooperation between P2Y2 and P2X7 receptors promote cutaneous leishmaniasis control: involvement of pannexin-1 and leukotrienes. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1531. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thorstenberg M.L., Martins M.D.A., Figliuolo V., Silva C.L.M., Savio L.E.B., Coutinho-Silva R. P2Y2 receptor induces L. Amazonensis infection control in a mechanism dependent on caspase-1 activation and IL-1beta secretion. Mediat Inflamm. 2020;2020:2545682. doi: 10.1155/2020/2545682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vaisitti T., Arruga F., Guerra G., Deaglio S. Ectonucleotidases in blood malignancies: a tale of surface markers and therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2301. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kukulski F., Levesque S.A., Lavoie E.G., Lecka J., Bigonnesse F., Knowles A.F., et al. Comparative hydrolysis of P2 receptor agonists by NTPDases 1, 2, 3 and 8. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-6217-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robson S.C., Sevigny J., Zimmermann H. The E-NTPDase family of ectonucleotidases: structure function relationships and pathophysiological significance. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:409–430. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Allard B., Longhi M.S., Robson S.C., Stagg J. The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73: novel checkpoint inhibitor targets. Immunol Rev. 2017;276:121–144. doi: 10.1111/imr.12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meyer-Fernandes J.R., Dutra P.M., Rodrigues C.O., Saad-Nehme J., Lopes A.H. Mg-dependent ecto-ATPase activity in Leishmania tropica. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;341:40–46. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peacock C.S., Seeger K., Harris D., Murphy L., Ruiz J.C., Quail M.A., et al. Comparative genomic analysis of three Leishmania species that cause diverse human disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:839–847. doi: 10.1038/ng2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pinheiro C.M., Martins-Duarte E.S., Ferraro R.B., Fonseca de Souza A.L., Gomes M.T., Lopes A.H., et al. Leishmania amazonensis: biological and biochemical characterization of ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase activities. Exp Parasitol. 2006;114:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vieira D.P., Paletta-Silva R., Saraiva E.M., Lopes A.H., Meyer-Fernandes J.R. Leishmania chagasi: an ecto-3'-nucleotidase activity modulated by inorganic phosphate and its possible involvement in parasite-macrophage interaction. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127:702–707. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Figueiredo A.B., Serafim T.D., Marques-da-Silva E.A., Meyer-Fernandes J.R., Afonso L.C. Leishmania amazonensis impairs DC function by inhibiting CD40 expression via A2B adenosine receptor activation. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1203–1215. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Basu M., Gupta P., Dutta A., Jana K., Ukil A. Increased host ATP efflux and its conversion to extracellular adenosine is crucial for establishing Leishmania infection. J Cell Sci. 2020;133:jcs239939. doi: 10.1242/jcs.239939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peres N.T.A., Cunha L.C.S., Barbosa M.L.A., Santos M.B., de Oliveira F.A., de Jesus A.M.R., et al. Infection of human macrophages by Leishmania infantum is influenced by ecto-nucleotidases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1954. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rai A.K., Thakur C.P., Velpandian T., Sharma S.K., Ghosh B., Mitra D.K. High concentration of adenosine in human visceral leishmaniasis despite increased ADA and decreased CD73. Parasite Immunol. 2011;33:632–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2011.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Charlab R., Valenzuela J.G., Rowton E.D., Ribeiro J.M. Toward an understanding of the biochemical and pharmacological complexity of the saliva of a hematophagous sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15155–15160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Katz O., Waitumbi J.N., Zer R., Warburg A. Adenosine, AMP, and protein phosphatase activity in sandfly saliva. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:145–150. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carregaro V., Ribeiro J.M., Valenzuela J.G., Souza-Junior D.L., Costa D.L., Oliveira C.J., et al. Nucleosides present on phlebotomine saliva induce immunossuppression and promote the infection establishment. PLoS Neglected Trop Dis. 2015;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fredholm B.B., Irenius E., Kull B., Schulte G. Comparison of the potency of adenosine as an agonist at human adenosine receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells11Abbreviations: cAMP, cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; NBMPR, nitrobenzylthioinosine; and NECA, 5′-N-ethyl carboxamido adenosine. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:443–448. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Antonioli L., Fornai M., Blandizzi C., Pacher P., Hasko G. Adenosine signaling and the immune system: when a lot could be too much. Immunol Lett. 2019;205:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gessi S., Merighi S., Varani K., Borea P.A. Adenosine receptors in health and disease. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;61:41–75. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ferrante C.J., Pinhal-Enfield G., Elson G., Cronstein B.N., Hasko G., Outram S., et al. The adenosine-dependent angiogenic switch of macrophages to an M2-like phenotype is independent of interleukin-4 receptor alpha (IL-4Ralpha) signaling. Inflammation. 2013;36:921–931. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9621-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Najar H.M., Ruhl S., Bru-Capdeville A.C., Peters J.H. Adenosine and its derivatives control human monocyte differentiation into highly accessory cells versus macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1990;47:429–439. doi: 10.1002/jlb.47.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mukbel R.M., Petersen C., Ghosh M., Gibson K., Patten C., Jones D.E. Macrophage killing of Leishmania amazonensis amastigotes requires both nitric oxide and superoxide. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:669–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xaus J., Mirabet M., Lloberas J., Soler C., Lluis C., Franco R., et al. IFN-γ up-regulates the A(2B) adenosine receptor expression in macrophages: a mechanism of macrophage deactivation. J Immunol. 1999;162:3607–3614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hasko G., Szabo C., Nemeth Z.H., Kvetan V., Pastores S.M., Vizi E.S. Adenosine receptor agonists differentially regulate IL-10, TNF-alpha, and nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 macrophages and in endotoxemic mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:4634–4640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lima M.H.F., Sacramento L.A., Quirino G.F.S., Ferreira M.D., Benevides L., Santana A.K.M., et al. Leishmania infantum parasites subvert the host inflammatory response through the adenosine A2A receptor to promote the establishment of infection. Front Immunol. 2017;8:815. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Figueiredo A.B., Souza-Testasicca M.C., Mineo T.W.P., Afonso L.C.C. Leishmania amazonensis-induced cAMP triggered by adenosine A2B receptor is important to inhibit dendritic cell activation and evade immune response in infected mice. Front Immunol. 2017;8:849. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Milano S., Arcoleo F., Dieli M., D'Agostino R., D'Agostino P., De Nucci G., et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase in the murine macrophage cell line J774. Prostaglandins. 1995;49:105–115. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(94)00004-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Barreto-de-Souza V., Pacheco G.J., Silva A.R., Castro-Faria-Neto H.C., Bozza P.T., Saraiva E.M., et al. Increased Leishmania replication in HIV-1-infected macrophages is mediated by tat protein through cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 synthesis. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:846–854. doi: 10.1086/506618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guimaraes E.T., Santos L.A., Ribeiro dos Santos R., Teixeira M.M., dos Santos W.L., Soares M.B. Role of interleukin-4 and prostaglandin E2 in Leishmania amazonensis infection of BALB/c mice. Microb Infect. 2006;8:1219–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Franca-Costa J., Van Weyenbergh J., Boaventura V.S., Luz N.F., Malta-Santos H., Oliveira M.C., et al. Arginase I, polyamine, and prostaglandin E2 pathways suppress the inflammatory response and contribute to diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:426–435. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pacheco P.A.F., Diogo R.T., Magalhães B.Q., Faria R.X. Plant natural products as source of new P2 receptors ligands. Fitoterapia. 2020;146:104709. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ai X., Dong X., Guo Y., Yang P., Hou Y., Bai J., et al. Targeting P2 receptors in purinergic signaling: a new strategy of active ingredients in traditional Chinese herbals for diseases treatment. Purinergic Signal. 2021;17:229–240. doi: 10.1007/s11302-021-09774-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mina J.G.M., Charlton R.L., Alpizar-Sosa E., Escrivani D.O., Brown C., Alqaisi A., et al. Antileishmanial chemotherapy through clemastine fumarate mediated inhibition of the Leishmania Inositol phosphorylceramide synthase. ACS Infect Dis. 2021;7:47–63. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yamane M., Ogawa Y., Fukui M., Kamoi M., Saijo-Ban Y., Yaguchi S., et al. Long-term rebamipide and diquafosol in two cases of immune mediated dry eye. Optom Vis Sci. 2015;92:S25–S32. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]