Abstract

Purpose

Given the relative radioresistance of sarcomas and their often large size, conventional palliative radiation therapy (RT) often offers limited tumor control and symptom relief. We report on our use of hypofractionated RT (HFRT) as a strategy to promote durable local disease control and optimize palliation.

Methods and Materials

We retrospectively reviewed 73 consecutive patients with sarcoma who received >10 fractions of HFRT from 2017 to 2020. Clinical scenarios included: (1) palliative or symptomatic intent (34%), (2) an unresectable primary (27%), (3) oligometastatic disease (16%), and (4) oligoprogressive disease (23%).

Results

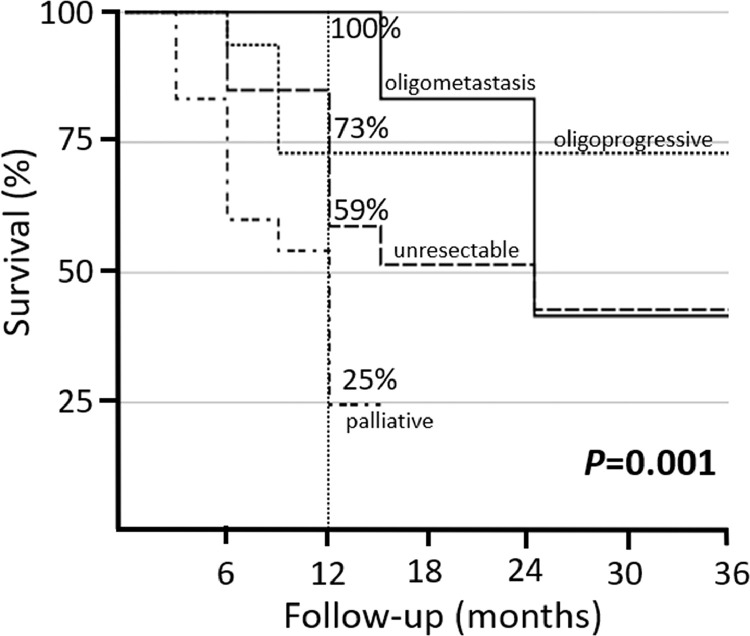

The HFRT target was a primary tumor in 64% of patients with a median dose of 45 Gy in 15 fractions (59% ≥45 Gy). The 1-year disease-specific survival was 59%, which was more favorable for patients receiving HFRT for oligometastatic (1-year 100%) or oligoprogressive (1-year 73%) disease (P = .001). The 1-year local control (LC) of targeted lesions was 73%. A metastatic target (1-year 95% vs 60% primary; P = .02; hazard ratio, 0.27; P = .04) and soft tissue origin (1-year 78% vs 61% bone; P = .01; hazard ratio, 0.33; P = .02) were associated with better LC. The rate of distant failure was high with a 6-month distant metastasis-free survival of only 43%. For patients not planned for adjuvant systemic therapy (n = 53), the median systemic therapy break was 9 months and notably longer in oligometastatic (13 months), oligoprogressive (12 months) or unresectable (13 months) disease. HFRT provided palliative relief in 95% of cases with symptoms. Overall, 49% of patients developed acute grade 1 to 2 RT toxicities (no grade 3-5). No late grade 2 to 5 toxicities were observed.

Conclusions

HFRT is an effective treatment strategy for patients with unresectable or metastatic sarcoma to provide durable LC, symptom relief, and systemic therapy breaks with limited toxic effects.

Introduction

Sarcomas represent a highly heterogeneous population of tumors with unique epidemiology, biology and sensitivity to treatment.1, 2, 3, 4 Accordingly, the contemporary management for sarcomas is complex in both the localized and metastatic setting.5 In the localized setting, treatment often requires a multidisciplinary approach with a combination of surgery, radiation therapy (RT) and systemic therapy.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 For localized soft tissue sarcoma preoperative RT is the preferred approach.11 In contrast, for bone sarcomas RT is more commonly performed in the adjuvant setting for positive margins or high-risk features or used as a definitive therapy for unresectable tumors.12, 13, 14, 15, 16

Although such approaches offer effective durable local control, high rates of distant metastasis remain a primary concern. Approximately one-third of sarcoma patients develop distant disease, and in particular those with high-risk features such as intermediate to high-grade or larger tumors are at an elevated risk of having metastatic disease.17, 18, 19 In the metastatic setting, management often includes anthracycline-based chemotherapy or second line systemic therapy.20,21 Unfortunately, overall response rates for systemic therapy are relatively poor with nearly all patients eventually progressing on therapy.22 Therefore, RT is commonly delivered in these settings with palliative intent for symptom relief.23

Due to the relative radioresistance and often large size of sarcoma lesions, conventionally fractionated palliative RT may be inadequate to provide effective palliation or durable tumor control.24 Furthermore, given the emerging understanding of the oligometastatic state,25,26 new evidence has demonstrated that improved oncologic outcomes including overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) can be achieved when aggressive local therapy in the form of surgery or RT is pursued along with systemic therapy.27,28 Recent evidence has highlighted this paradigm shift in the multimodal management of sarcoma, specifically using locally directed treatments such as metastasectomy and locally ablative therapies (including RT and radiofrequency ablation) in patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease.29,30 Therefore, these data further support this concept of dose escalation as a form of more aggressive local therapy, in select patients, with the goal of improving outcomes. Given the shifting paradigms and increasing use of hypofractionated RT (HFRT) to more aggressively manage patients with sarcoma diagnoses in patients not eligible for stereotactic body RT (SBRT) due to size or anatomic considerations, we evaluated our experience to determine tumor and survival outcomes, efficacy of palliation, and duration of systemic therapy breaks.

Methods and Materials

Seventy-three patients with histologically confirmed sarcoma who were treated with >10 fractions of HFRT (dose >2 Gy per fraction) at our institution between 2017 and 2020 were retrospectively identified from institutional databases for subsequent review and analysis. Institutional review board approval was obtained before reviewing patients’ medical records. Treatment decisions regarding all patients were based on consensus recommendations from a multidisciplinary sarcoma team.

The reason for more aggressive HFRT was categorized into 4 clinical indications including: (1) palliation or symptom relief that the treating physician thought may not respond as well to conventional palliative doses; (2) more definitive intent for an unresectable primary; (3) oligometastatic disease; or (4) oligoprogressive disease where the goal of RT was to delay or prevent the need to change or reinitiate chemotherapy. Oligometastatic disease was defined as <5 sites of metastases based on CT or positron emission tomography imaging. Oligoprogressive disease was defined as limited sites (<3) of progressive disease in patients with otherwise stable metastatic disease.

HFRT was delivered most commonly using intensity modulated radiation therapy with a simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) to further escalate the dose. Gross tumor volumes (GTV) were contoured based on imaging or clinical findings. Expansions for clinical target volumes (CTV) varied based on the clinical scenario, anatomic location, and tumor type, and generally ranged between ∼1 to 2 cm. The planning target volume expansions were dependent on the immobilization, motion management, and image guidance but typically were 5 to 8 mm.

Dose fractionation was determined by the treating radiation oncologist. A number of factors were used to guide radiation prescriptions including target size, anatomic location, and treatment intent. The histologic subtype was less commonly used to guide prescription selection. Radiation doses generally <40 Gy were employed for patients treated with palliative intent, whereas doses ranging between 45 and 52.5 Gy in 15 fractions were more commonly prescribed for unresectable tumors and those with oligometastatic/oligoprogressive disease. In those cases, when nearby organs at risk did not exceed standard dose constraints following biologic equivalent dose calculations, the GTV prescription was commonly 52.5 Gy in 15 fractions. If equivalent standard dose constraints were exceeded, the GTV prescription was commonly lowered to 45 Gy and an intentional heterogenous 110% to 120% “hot center” was permitted as a way to safely dose escalate the GTV while still prioritizing a low toxicity risk. Multiple dose-levels were often employed using a SIB technique. When the GTV was prescribed 52.5 Gy in 15 fractions, the CTV was typically prescribed 45 Gy. If the GTV was prescribed 45 Gy in 15 fractions, the CTV received 37.5 Gy.

Patient follow-up most commonly involved a clinical history, physical examination, and serial imaging every 3 months for the first 3 years and annually thereafter. Local control (LC) of the targeted lesion was assessed by serial cross-sectional imaging. Musculoskeletal radiology reports were used to annotate the best radiographic response after RT and were categorized as a decrease in size only, a decrease in size and enhancement or avidity, decreased enhancement or avidity only, or having stable disease without evidence of radiographic progression. Once radiographic reports annotated tumor growth or increasing enhancement or avidity, if that trend continued on follow-up imaging, the date of the initial imaging change was scored as progressive. Pain response was assessed by comparing patient reported pain scores before and after HFRT.

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate baseline patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics. Fisher exact tests and χ2 analyses were used to evaluate differences between categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate actuarial rates of OS, PFS, disease-specific survival (DSS), LC, and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) with survival times calculated from the completion of local therapy. Log-rank tests were used to assess differences between actuarial curves. Multivariable analyses were conducted using the Cox proportional hazards model. Significant (P < .05) estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for data analysis.

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics

Patient and tumor characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age was 51 years (interquartile range [IQR], 35-69 years), and 60% (n = 44) were male. The HFRT strategy was used to treat primary tumors (n = 47, 64%) more commonly than sites of metastatic disease (n = 26, 36%). Anatomically, most irradiated tumors were located in the trunk (n = 48, 66%), with the majority either intrathoracic (n = 18, 38%) or in the pelvis (n = 14, 29%). The next most common involved anatomic location was the head and neck (n = 20, 27%), with 8 (40%) involving the neck and the other 12 (60%) involving various subsites of the head. Involvement of the extremities was least common (upper, n = 2, 3%; lower, n = 3, 4%). The median tumor size was 7 cm (range, 1-23 cm) and 27% of tumors (n = 20) were >10 cm.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

| Variable | Value or n (%)N = 73 |

|---|---|

| Follow-up time for all patients, mo | |

| Median | 9 |

| Range | 2-24 |

| IQR | 5-13 |

| Age, y | |

| Median | 51 |

| Range | 18-86 |

| IQR | 35-69 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 29 (40) |

| Male | 44 (60) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 19 (26) |

| 1 | 35 (48) |

| 2 | 14 (19) |

| 3 | 2 (3) |

| 4 | 3 (4) |

| Median | 1 |

| Irradiated tumor | |

| Primary tumor | 47 (64) |

| Metastasis | 26 (36) |

| Irradiated location | |

| Head and neck | 20 (27) |

| Upper extremities | 2 (3) |

| Lower extremities | 3 (4) |

| Trunk | 48 (66) |

| Superficial trunk | 12 |

| Intrathorax | 18 |

| Pelvis | 14 |

| Retroperitoneum | 4 |

| Sarcoma type | |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 53 (73) |

| Bone sarcoma | 20 (27) |

| Histology | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 11 (15) |

| Synovial sarcoma | 9 (12) |

| High-grade sarcoma, NOS | 9 (12) |

| Osteosarcoma | 6 (8) |

| Ewing sarcoma | 6 (8) |

| Chondrosarcoma | 5 (7) |

| Dedifferentiated liposarcoma | 4 (6) |

| Angiosarcoma | 4 (6) |

| Chordoma | 3 (4) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 3 (4) |

| Solitary fibrous tumor | 3 (4) |

| Hemangioendothelioma | 2 (3) |

| Myxoid liposarcoma | 2 (3) |

| MPNST | 2 (3) |

| Other | 4 (6) |

| Maximum tumor dimension, cm | |

| Median | 7 |

| Range | 1-23 |

| IQR | 4-12 |

| Tumor size | |

| ≤5 cm | 28 (38) |

| 5-10 cm | 25 (34) |

| >10 cm | 20 (27) |

Abbreviations: ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IQR = interquartile range; NOS = not otherwise specified; MPNST = malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.

Most tumors were of soft tissue origin (n = 53, 73%). Leiomyosarcomas (n = 11) and synovial sarcomas (n = 9) were the most common, although other histologies were also treated (Table 1). Tumors of bone origin were less common (n = 20, 27%) and included osteosarcoma (n = 6), Ewing sarcoma (n = 6), chondrosarcoma (n = 5), and chordoma (n = 3).

Treatment

Most patients (n = 64, 87.7%) received systemic therapy before HFRT, often having had multiple lines of therapy (median = 2; ≥2 lines; n = 46, 63%) during the course of their sarcoma treatment. Immediately preceding RT, 50 (68%) patients had received systemic therapy, most commonly chemotherapy (n = 33), whereas 23 (32%) patients were not treated with systemic therapy immediately before RT. Additionally, at initiation of HFRT, the majority of the tumors were radiographically progressing (n = 56, 77%) whereas 8 (11%) patients had stable disease and 9 (12%) had a partial response to therapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment characteristics

| Variable | Value or n (%)N = 73 |

|---|---|

| Lines of systemic therapy preceding HFRT | |

| Median | 2 |

| Range | 0-11 |

| IQR | 1-3 |

| 0 | 9 (12) |

| 1 | 18 (25) |

| 2-3 | 29 (40) |

| ≥4 | 17 (23) |

| Systemic therapy immediately preceding HFRT | |

| Chemotherapy | 33 (45) |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | 9 (12) |

| Immunotherapy | 8 (11) |

| None | 23 (32) |

| Best radiographic response of tumor before HFRT | |

| Progressing | 56 (77) |

| Stable | 8 (11) |

| Partial response | 9 (12) |

| Rationale for hypofractionated HFRT | |

| Palliation | 25 (34) |

| Unresectable | 20 (27) |

| Oligoprogression | 16 (23) |

| Oligometastasis | 12 (16) |

| Dose-fraction schemes to GTV | |

| Median | 45 Gy/15 fx |

| 35 Gy/14 fx | 1 (1) |

| 36 Gy/12 fx | 5 (7) |

| 37.5 Gy/15 fx | 9 (12) |

| 39 Gy/12 fx | 1 (1) |

| 39.6 Gy/12 fx | 1 (1) |

| 42 Gy/12 fx | 4 (5) |

| 42.5 Gy/17 fx | 9 (12) |

| 45 Gy/15 fx | 32 (44) |

| 45.9 Gy/17 fx | 1 (1) |

| 48.75 Gy/15 fx | 1 (1) |

| 51 Gy/17 fx | 1 (1) |

| 52.5 Gy/15 fx | 8 (11) |

| Dose-fraction schemes to PTV | |

| Median | 37.5 Gy/15 fx |

| 33 Gy/12 fx | 1 (1) |

| 35 Gy/14 fx | 1 (1) |

| 35 Gy/15 fx | 1 (1) |

| 36 Gy/12 fx | 7 (10) |

| 37.5 Gy/15 fx | 44 (60) |

| 37.5 Gy/17 fx | 1 (1) |

| 38.25 Gy/17 fx | 2 (3) |

| 39 Gy/12 fx | 1 (1) |

| 40.05 Gy/15 fx | 1 (1) |

| 42 Gy/12 fx | 1 (1) |

| 42.5 Gy/17 fx | 7 (10) |

| 45 Gy/15 fx | 6 (8) |

| Dose per fraction GTV | |

| <3 Gy/fx | 21 (29) |

| 3 Gy/fx | 38 (52) |

| >3 Gy/fx | 14 (19) |

| SIB used | |

| Yes | 47 (64) |

| No | 26 (36) |

| GTV “hot center” | |

| Yes | 20 (27) |

| No | 53 (73) |

| Best radiographic response to HFRT | |

| Decreased size | 30 (41) |

| Decreased size and enhancement/avidity | 19 (26) |

| Decreased enhancement/avidity only | 5 (7) |

| Stable only | 16 (22) |

| Unknown | 3 (4) |

Abbreviations: fx = fraction; GTV = gross tumor volume; HFRT = hypofractionated radiation therapy; IQR = interquartile range; NOS = not otherwise specified; PTV = planning target volume; SIB = simultaneous integrated boost.

The rationale for delivery of HFRT varied, but the most common reason was for palliation of symptoms (n = 25, 34%); 35 (48%) patients had tumor-related pain at the time of RT (Table 3). Patients receiving palliative hypofractionated RT tended to have larger tumors (median, 9 cm) than patients receiving RT for other reasons (median, 6 cm; P = .02), which included irradiating unresectable primary tumors (n = 20, 27%) or local treatment for oligoprogression (n = 16, 23%) or oligometastasis (n = 12, 16%).

Table 3.

Symptoms related to tumor and radiation toxicity

| Variable | Value or n (%)N = 73 |

|---|---|

| Symptoms related to tumor | |

| None | 34 (47) |

| Pain only | 28 (38) |

| Neurologic only | 1 (1) |

| Pain and neurologic | 7 (10) |

| Other | 3 (4) |

| Symptomatic benefit after RT | |

| Yes | 37 (51) |

| No | 2 (3) |

| Absence of symptoms before RT | 34 (46) |

| Acute toxicity | |

| None | 37 (51) |

| Pain flare | 15 (21) |

| Lower GI | 13 (18) |

| Upper GI | 14 (19) |

| Acute GI toxicity grade | |

| Grade 1 | 20 (74) |

| Grade 2 | 7 (26) |

| Grades 3-5 | 0 (0) |

| Late toxicity | |

| Respiratory | 2 (3) |

| GI | 0 (0) |

| Neurologic | 0 (0) |

| Late toxicity grade | |

| Grade 1 | 2 (3) |

| Grades 2-5 | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: GI = gastrointestinal; RT, radiation therapy.

The median RT dose was 45 Gy (IQR, 42-45 Gy) over a median of 15 fractions with 43 (59%) patients receiving ≥45 Gy (Table 2). Details of dose-fractionation schemes are presented in Table 1. Delivery of 3 Gy per fraction was most common (n = 38, 52%), whereas higher total doses were more commonly used to treat truncal tumors (P = .001) and to treat patients receiving HFRT for unresectable or oligo-metastatic or progressive disease compared with palliative intent (P = .03). An SIB technique was used for 47 (64%) of patients to provide dose-escalation to the GTV and or CTV. Additionally, heterogeneity was planned for 20 (27%) patients with intentionally higher doses to the center of the tumor (median, 52.5 Gy; IQR 48-52.5 Gy).

Of the 39 (54%) patients who had tumor-related symptoms before RT, 37 (95%) had improvement after treatment, including 33 of the 35 patients presenting with pain.

Patterns of disease recurrence

After RT, 49 (67%) patients had a measurable partial response with a decrease in the size of treated tumors with 19 (39%) also exhibiting decreased enhancement or fluorodeoxyglucose-avidity. Sixteen (22%) patients had no radiographic change in their tumor (Table 2).

Nineteen (26%) patients developed local failure of the irradiated tumor at a median time of 7.5 months (IQR, 5.5-13). The 1- and 2-year LC was 73% and 47%, respectively. Two factors associated with more favorable LC on univariate analysis included having the metastasis as the target lesion (1-year 95% vs 60% primary tumor, P = .02) and having a sarcoma of soft tissue origin (1-year 78% vs 61% for bone sarcomas, P = .01); smaller tumor size ≤5 cm neared favorable significance (1-year LC 82% vs 66% for >5 cm; P = .07). On univariate analysis, LC was not associated with radiation dose stratified at 45 Gy (P = .84), dose per fraction (<3 Gy vs 3 Gy vs >3 Gy, P = .92), use of a SIB to increase the dose to the central part of the tumor (P = .46), or radiographic response after RT (P = .23). On multivariable analysis accounting for tumor size, tissue origin, and target type, both having a metastatic site as the target lesion (HR, 0.27; P = .04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.94) and the target being of soft tissue origin (HR, 0.33; P = .02; 95% CI, 0.13-0.87) remained significant for LC.

The rate of distant failure from targeted lesions (progression at an existing untreated distant site or development of a new distant site) was high with a 6-month and 1-year DMFS of only 43% and 22%, respectively. Fifty-two (71%) patients developed distant relapse or progression at a median time of 2 months (IQR 1-5 months). Three factors were associated with more favorable DMFS on univariate analysis; having a primary tumor as the target lesion (1-year 33% vs 0% for metastasis, P = .01), diagnostic imaging showing stable or partial response of the target tumor before irradiating (1-year 53% vs 12% for a progressing target, P = .01), and the clinical rationale for HFRT being used for an unresectable primary (6-month 70% vs 40% for oligoprogression vs 53% for oligometastasis vs 15% for palliation, P < .001). However, on multivariable analysis accounting for target origin (primary site vs metastasis), systemic treatment before RT, response of target before RT, and rationale for RT, only the rationale for RT (unresectable primary = HR, 0.14; P < .001; 95% CI, 0.06-0.33; oligometastatic = HR, 0.25; P = .003; 95% CI, 0.1-0.62; oligoprogression = HR, 0.51; P = .07; 95% CI, 0.25-1.06; all vs palliation as the rationale) remained significant.

Survival

The median follow-up time from the completion of RT was 9 months (IQR, 5-13 months). The 1- and 2-year OS rates were 53% and 39%, respectively (Fig. 1). There were 31 (43%) deaths attributable to disease resulting in a median survival of 9.5 months (IQR 5-13) and a 1- and 2-year DSS of 59% and 43%, respectively. On univariate analysis, the only factor associated with DSS was the clinical rationale for hypofractionated RT. The 1- and 2-year DSS was more favorable for patients treated for oligoprogressive (73% and 73%) or oligometastatic (100% and 83%) disease compared with unresectable primary (59% and 43%) or for palliation (25% and 0%) (P = .001; Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing outcomes for patients with sarcoma using a hypofractionated radiation therapy strategy: (A) 12-month overall survival (53%), (B) 12-month disease-specific survival (59%), (C) 12-month local control (73%), and (D) 6-month distant metastatic free survival (43%).

Figure 2.

A Kaplan-Meier curve showing disease-specific survival at 12 months by the clinical rationale for using a hypofractionated radiation strategy including oligometastasis (100%), oligoprogression (73%), unresectable primary (59%), and palliation (25%) (P = .001).

Systemic therapy break

A total of 23 (32%) patients were not receiving systemic therapy before RT (within 1 month), of whom 9 had never received systemic therapy typically due to limited efficacy for their tumor-type. After RT, 20 (27%) patients were planned to restart or continue systemic therapy, whereas 53 were not planned for additional therapy. For all patients, the median systemic therapy break was 6.5 months (IQR 2.5-20). However, for patients not planned for adjuvant systemic therapy, the median systemic therapy break was 9 months (IQR 4-23).

The systemic therapy break was notably longer for patients receiving RT due to oligometastatic (median, 13 months; IQR, 8-36 months), oligoprogressive (median, 12 months; IQR, 3-25 months), or for unresectable disease (median, 13 months; IQR 7-35 months) compared with those treated for palliation of symptoms.

Outcomes for patients with oligometastatic or oligoprogressive disease

Twelve (16%) patients received HFRT to treat oligometastatic disease for which the 1- and 2-year OS was 91% and 38%, respectively. Two (17%) patients developed local recurrence at a median of 8.5 months while 7 (58%) developed distant recurrence at a median of 5 months (IQR 3-8). The median systemic therapy break was 13 months and RT provided a median addition of 7 months off systemic therapy (IQR 5-14 months).

Sixteen (23%) patients were treated due to oligoprogression for which both the 1- and 2-year OS was 73%, respectively. Six (38%) patients developed local relapse at a median of 12 months (IQR, 6-18), and all but one (94%) developed distant progression at a median time of 4.5 months (IQR, 1-7). The median systemic therapy break was 12 months and RT provided a median addition of 6 months off systemic therapy (IQR 2-11.5).

Toxic effects

Acute radiation-related toxic effects occurred in 36 patients (49%). Twenty-seven (37%) patients experienced acute gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity; 14 (52%) had upper GI-related symptoms (ie, mucositis, dysphagia, esophagitis, etc), and 13 (48%) had lower GI symptoms (ie, increased bowel movements, nausea, vomiting, etc). Most patients had grade 1 toxicities (n = 20, 74%), with a minority of grade 2 (n = 7, 26%) and no grade 3 to 5 toxicities. Fifteen (21%) patients had a pain flare related to RT, which occurred more commonly in patients who had tumor-related pain before RT (P = .04). Late toxic effects were limited. Two (3%) patients had grade 1 pneumonitis and 1 (1%) patient had expected persistent dry eye. There were no late neurologic or GI-related toxic effects.

Discussion

The management of sarcoma is complex in both the localized and metastatic setting due to its relative resistance to conventional oncologic therapy. Considering suboptimal outcomes in the unresectable and metastatic setting with conventional RT and anatomic or size limitations for SBRT, we present one of the largest series of hypofractionated RT for patients with unresectable or metastatic sarcoma. Our findings demonstrate that HFRT is an effective treatment option for such patients as it confers durable local control, excellent symptom relief and prolonged systemic therapy breaks with limited toxic effects. In particular, patients with oligometastatic or oligoprogressive disease appeared to derive the greatest benefit with favorable disease-specific survival and significant chemotherapy breaks, which likely improves quality of life for these patients.

HFRT is increasingly being used as an escalated form of local therapy in select patients with oligometastatic presentations or limited gross disease. Additionally, HFRT is also being increasingly used in the definitive setting for multidisciplinary sarcoma management.31,32 SBRT is efficacious with high rates of LC in appropriately selected patients. A majority of the evidence is based on SBRT for sarcoma lung metastases. Dose fractionation schemes for lung SBRT have ranged from 30 to 60 Gy in 1 to 10 fractions and have been seen to yield 86% to 96% LC.33, 34, 35 Outside of the lung, stereotactic approaches for metastatic sarcomas include treating spinal metastases with spine SRS (SSRS).36, 37, 38 In these studies, SSRS was delivered to 18 to 36 Gy in 1 to 6 fractions achieving LC rates of 81% to 91%.36, 37, 38 Notably, some of these studies demonstrated improved LC with dose escalation, in particular a biologically effective dose (BED) >45 Gy was noted to be a significant predictor of improved LC (P = .006).37,38 However, given the natural history of sarcomas, commonly lesions grow too large for SBRT or in locations not conducive to this strategy. This is reflected in our series as 62% of treated sites were >5 cm in size (median 7 cm), thus beyond the size threshold of SBRT. Additionally, despite there often large size many of these tumors were not necessarily strictly palliative cases where common palliative dose regimens like 20 Gy in 5 fractions would be warranted as many of these patients did not have necessarily have extensive metastatic disease, poor functional status, or immanent prognosis of death. Therefore, HFRT was used as a means of delivering dose-escalated and more aggressive therapy compared with conventional palliative treatment. This HFRT strategy has been demonstrated to be effective in other tumor types such as central non-small cell lung cancer with low toxicity, while also offering the advantage of using concurrent chemotherapy or immunotherapy.39, 40, 41 Thus, considering that a majority of patients with metastatic or unresectable sarcomas are suboptimal SBRT candidates, HFRT serves as an intermediary approach to pursue improved LC without significant treatment toxicity.

Using HFRT we achieved 1- and 2-year LC rates of 73% and 47%, respectively. It is difficult to draw comparisons of HFRT to conventional fractionation with respect to efficacy of palliation in metastatic sarcoma as there is limited evidence on the subject. For example, in a recently published study of nearly 300 patients treated with conventional palliative RT to the spine, only about 10 patients had sarcoma histology which precluded any histology-specific analysis.42 In general, however, conventional palliative RT has resulted in local control rates around 50% to 70% among all malignancies, most of which are notably more responsive to RT than sarcomas.43, 44, 45 The relative radio-resistance of sarcomas has been supported by preclinical and clinical data. Sarcomas generally have been noted to have relatively low α/β ratios a measure of sensitivity to radiation fractionation, suggesting that such tumors may be more vulnerable to HFRT.46, 47, 48 This coupled with recent advances in RT technology and image guidance, makes hypofractionated approaches an attractive option, particularly for patients with unresectable tumors or oligometastatic disease.

The patients who are to derive the greatest benefit from these more aggressive approaches are undoubtedly those with oligometastatic or oligoprogressive disease. Our findings revealed that patients with oligometastatic and oligoprogressive disease had significantly improved 1-year DSS at 100% and 73% (P = .001) respectively compared with those treated with unresectable primaries or with a palliative rationale. Furthermore, patients with oligometastatic disease were noted to have significantly improved DMFS. Similar findings for patients with NSCLC were reported in the landmark trial by Gomez et al27 after observing a substantial PFS benefit with local consolidative therapy (LCT) in patients with oligometastatic NSCLC as LCT improved median PFS to 14.2 months compared with 4.4 months for standard of care systemic therapy (P = .022). Similarly, the SABR-COMET trial displayed that SBRT for oligometastatic patients doubled median progression free survival.28

Analogous findings have been demonstrated in sarcoma.29,30 Most notably, a prospective study conducted by the French Sarcoma Group evaluated the efficacy of LCT for 281 patients with oligometastatic sarcoma.30 This study used a combination of LCT including surgery, radiofrequency ablation, and RT and reported a substantial improvement in OS with LCT 45.3 months vs standard of care systemic therapy 12.6 months.30 Although treatment in the oligometastatic setting remains an evolving paradigm, patient selection is of chief importance. This is reflected by the high rate of progressive distant failure reported within our series, with a 6-month DMFS of only 43%. In totality, these data highlight the importance of patient selection to balance the benefits of LCT while prioritizing systemic therapy for those who are greater risk of distant failure.

Although LC and OS are important measures for such patients, symptom relief and palliation is also paramount and one of the most common indications for RT in patients with metastatic sarcoma. Overall, limited data are available in the modern area exploring the efficacy of RT for palliation in patients with metastatic sarcoma. A recent comprehensive study by Tween et al49 evaluated the role of HFRT for 105 patients with metastatic sarcoma treated with 25 different dose fractionation schemes. Although this study did not report OS or LC related outcomes, they did note that 70% of patients with STS and 55% of those with osseous sarcomas reported significant improvement in their symptoms.49 This study noted that a BED of 50 Gy (α/β = 4) was associated with improved palliation, yet no additional dose response was seen above this level.49 Our results, however, suggest that higher biologic doses may achieve better palliation as 95% of patients in our series received symptomatic relief. This underscores that one of the primary rationales of using HFRT for sarcoma patients should be for improved palliation and also prevention of serious complications and or quality of life consequences from continued tumor progression.

Another critical endpoint for patients that is less commonly reported but is effective for quality of life (QOL) for patients with incurable cancer presentations is time off of systemic therapy. We found that HFRT was successful in providing systemic therapy breaks, particularly for patients with oligometastatic or progressive and unresectable disease. Emerging evidence supports this finding as HFRT has recently also been shown to provide meaningful drug holidays in patients with metastatic ovarian cancer.50 The benefits of drug holidays include both improving patient QOL and reducing drug resistance as have been exhibited in several disease sites,51, 52, 53 including sarcoma.54 The ability of HFRT to offer effective palliation for sarcoma patients while also potentially providing a valuable systemic therapy breaks can drastically improve patient QOL.

Although this study represents the largest single‐institution series of sarcoma patients treated with HFRT there still remains limitations inherent to the retrospective nature of this study. First, there is intentional selection bias in terms of the patient cohort selected to receive dose-escalated therapy as patients with more significant disease burden, poor functional status, or significant comorbidities would likely receive conventional palliative RT. Additionally, this study examined a heterogenous cohort of patients with rare diseases representing different sarcoma histologies or biologies, anatomic sites, treatment indications (palliative, curative, oligometastatic etc) and tumor sizes, which decreases the power to detect interactions between variables. Similarly, due to the relatively heterogeneous dose-fractionation schemes used and variable α/β ratios for differing sarcoma histologies, we were unable to confidently explore the effects of dose-escalation or BED on outcomes. Furthermore, although systemic therapy regimens were quite varied, specific regimen details were not available for analysis. Finally, long-term follow-up would be beneficial to better understand the durability of this HFRT approach.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that HFRT is an effective treatment strategy for patients with unresectable or metastatic sarcoma as it can provide durable LC, excellent symptom relief and valuable systemic therapy breaks while conferring limited toxic effects. Those with oligometastatic or oligoprogressive disease derive the greatest benefit. However, appropriate patient selection remains crucial as risk of distant failure remains high for a large proportion of patients with unresectable primary and metastatic sarcoma. Further investigations are required to determine the optimal dose-fractionation regimens for HFRT in this setting.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Disclosures: none.

Data sharing statement: Research data are stored in an institutional repository and may be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Grünewald TG, Alonso M, Avnet S, et al. Sarcoma treatment in the era of molecular medicine. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12:e11131. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201911131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gage MM, Nagarajan N, Ruck JM, et al. Sarcomas in the United States: Recent trends and a call for improved staging. Oncotarget. 2019;10:2462–2474. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bovée JVMG, Hogendoorn PCW. Molecular pathology of sarcomas: Concepts and clinical implications. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:193–199. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0828-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toro JR, Travis LB, Wu HJ, Zhu K, Fletcher CDM, Devesa SS. Incidence patterns of soft tissue sarcomas, regardless of primary site, in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1978-2001: An analysis of 26,758 cases. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2922–2930. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farooqi A, Mitra D, Guadagnolo BA, Bishop AJ. The evolving role of radiation therapy in patients with metastatic soft tissue sarcoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22:79. doi: 10.1007/s11912-020-00936-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisters PW, Harrison LB, Leung DH, Woodruff JM, Casper ES, Brennan MF. Long-term results of a prospective randomized trial of adjuvant brachytherapy in soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:859–868. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, Tepper J, Glatstein E, et al. The treatment of soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities: prospective randomized evaluations of (1) limb-sparing surgery plus radiation therapy compared with amputation and (2) the role of adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1982;196:305–315. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198209000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang JC, Chang AE, Baker AR, et al. Randomized prospective study of the benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:197–203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benjamin RS, Wagner MJ, Livingston JA, Ravi V, Patel SR. Chemotherapy for bone sarcomas in adults: The MD Anderson experience. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015:e656–e660. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.e656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gronchi A, Palmerini E, Quagliuolo V, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in high-risk soft tissue sarcomas: Final results of a randomized trial from Italian (ISG), Spanish (GEIS), French (FSG), and Polish (PSG) Sarcoma Groups. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2178–2186. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Sullivan B, Davis AM, Turcotte R, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative radiotherapy in soft-tissue sarcoma of the limbs: A randomised trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2002;359:2235–2241. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutowski CJ, Basu-Mallick A, Abraham JA. Management of bone sarcoma. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96:1077–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimer R, Athanasou N, Gerrand C, et al. UK guidelines for the management of bone sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/317462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picci P, Sangiorgi L, Bahamonde L, et al. Risk factors for local recurrences after limb-salvage surgery for high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremities. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:899–903. doi: 10.1023/a:1008230801849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sailer SL. The role of radiation therapy in localized Ewing sarcoma. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1997;7:225–235. doi: 10.1053/SRAO00700225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyce-Fappiano D, Guadagnolo BA, Ratan R, et al. Evaluating the soft tissue sarcoma paradigm for the local management of extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma. The Oncologist. 2021;26:250–260. doi: 10.1002/onco.13616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weitz J, Antonescu CR, Brennan MF. Localized extremity soft tissue sarcoma: Improved knowledge with unchanged survival over time. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2719–2725. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coindre J-M, Terrier P, Guillou L, et al. Predictive value of grade for metastasis development in the main histologic types of adult soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 2001;91:1914–1926. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010515)91:10<1914::aid-cncr1214>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zagars GK, Ballo MT, Pisters PWT, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with localized soft-tissue sarcoma treated with conservation surgery and radiation therapy. Cancer. 2003;97:2530–2543. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seddon B, Strauss SJ, Whelan J, et al. Gemcitabine and docetaxel versus doxorubicin as first-line treatment in previously untreated advanced unresectable or metastatic soft-tissue sarcomas (GeDDiS): A randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1397–1410. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30622-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Judson I, Verweij J, Gelderblom H, et al. Doxorubicin alone versus intensified doxorubicin plus ifosfamide for first-line treatment of advanced or metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma: A randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:415–423. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karavasilis V, Seddon BM, Ashley S, Al-Muderis O, Fisher C, Judson I. Significant clinical benefit of first-line palliative chemotherapy in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma: Retrospective analysis and identification of prognostic factors in 488 patients. Cancer. 2008;112:1585–1591. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perry H, Chu FCH. Radiation therapy in the palliative management of soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 1962;15:179–183. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196201/02)15:1<179::aid-cncr2820150125>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soyfer V, Corn BW, Kollender Y, Tempelhoff H, Meller I, Merimsky O. Radiation therapy for palliation of sarcoma metastases: A unique and uniform hypofractionation experience. Sarcoma. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/927972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellman S, Oligometastases Weichselbaum RR. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:8–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weichselbaum RR, Hellman S. Oligometastases revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:378–382. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J, et al. Local consolidative therapy vs. maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Long-term results of a multi-institutional, phase II, randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1558–1565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard of care palliative treatment in patients with oligometastatic cancers (SABR-COMET): A randomised, phase 2, open-label trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2019;393:2051–2058. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang S, Kim H-S, Kim S, Kim W, Han I. Post-metastasis survival in extremity soft tissue sarcoma: A recursive partitioning analysis of prognostic factors. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1649–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falk AT, Moureau-Zabotto L, Ouali M, et al. Effect on survival of local ablative treatment of metastases from sarcomas: A study of the French sarcoma group. Clin Oncol. 2015;27:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalbasi A, Kamrava M, Chu F-I, et al. A phase II trial of 5-day neoadjuvant radiotherapy for patients with high-risk primary soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:1829–1836. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spałek MJ, Koseła-Paterczyk H, Borkowska A, et al. Combined preoperative hypofractionated radiotherapy with doxorubicin-ifosfamide chemotherapy in marginally resectable soft tissue sarcomas: Results of a phase 2 clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110:1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navarria P, Ascolese AM, Cozzi L, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for lung metastases from soft tissue sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frakulli R, Salvi F, Balestrini D, et al. Stereotactic radiotherapy in the treatment of lung metastases from bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:5581–5586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsay AD, Haupt EE, Chan CM, et al. Treatment of sarcoma lung metastases with stereotactic body radiotherapy. Sarcoma. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/9132359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang UK, Cho WI, Lee DH, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for primary and metastatic sarcomas involving the spine. J Neurooncol. 2012;107:551–557. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0777-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishop AJ, Tao R, Guadagnolo BA, et al. Spine stereotactic radiosurgery for metastatic sarcoma: patterns of failure and radiation treatment volume considerations. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;27:303–311. doi: 10.3171/2017.1.SPINE161045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Folkert MR, Bilsky MH, Tom AK, et al. Outcomes and toxicity for hypofractionated and single-fraction image-guided stereotactic radiosurgery for sarcomas metastasizing to the spine. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2014;88:1085–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang P, Swanick CW, Pezzi TA, et al. Outcomes and toxicity following high-dose radiation therapy in 15 fractions for non-small cell lung cancer. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7:433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang D, Bi N, Zhang T, et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety between simultaneous integrated boost intensity-modulated radiotherapy and conventional intensity-modulated radiotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl. 2019;14:106. doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng KL, Poon I, Ung YC, Zhang L, Cheung P. Accelerated hypofractionated radiation therapy for centrally located lung tumors not suitable for stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) or concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102:e719–e720. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen JJ, Sullivan AJ, Shi DD, et al. Characteristics and predictors of radiographic local failure in patients with spinal metastases treated with palliative conventional radiation therapy. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2021.100665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao G, Suki D, Chakrabarti I, et al. Surgical management of primary and metastatic sarcoma of the mobile spine. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:120–128. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/9/8/120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bilsky MH, Boland PJ, Panageas KS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF, Healey JH. Intralesional resection of primary and metastatic sarcoma involving the spine: Outcome analysis of 59 patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1277–1287. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200112000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerszten PC, Mendel E, Yamada Y. Radiotherapy and radiosurgery for metastatic spine disease: What are the options, indications, and outcomes? Spine. 2009;34:S78. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b8b6f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown JM, Carlson DJ, Brenner DJ. The tumor radiobiology of SRS and SBRT: Are more than the 5 Rs involved? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thames HD, Suit HD. Tumor radioresponsiveness versus fractionation sensitivity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12:687–691. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(86)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haas RLM, Miah AB, LePechoux C, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy for extremity soft tissue sarcoma: Past, present and future perspectives on dose fractionation regimens and combined modality strategies. Radiother Oncol. 2016;119:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tween H, Peake D, Spooner D, Sherriff J. Radiotherapy for the palliation of advanced sarcomas—the effectiveness of radiotherapy in providing symptomatic improvement for advanced sarcomas in a single centre cohort. Healthcare. 2019;7 doi: 10.3390/healthcare7040120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lazzari R, Ronchi S, Gandini S, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for oligometastatic ovarian cancer: A step toward a drug holiday. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2018;101:650–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song T, Yu W, Wu S-X. Subsequent treatment choices for patients with acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs in non-small cell lung cancer: Restore after a drug holiday or switch to another EGFR-TKI? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:205–213. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chu E. The role of a drug holiday: Even patients with cancer need a vacation. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2006;6:182. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2006.n.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tonini G, Imperatori M, Vincenzi B, Frezza AM, Santini D. Rechallenge therapy and treatment holiday: Different strategies in management of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32:92. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lebellec L, Defachelles A-S, Cren P-Y, Penel N. Maintenance therapy and drug holiday in sarcoma patients: Systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2020;59:1084–1090. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1759825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]