Abstract

Introduction

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) is a rare vascular congenital disorder characterized by the classical triad of port-wine stains, abnormal growth of soft tissues and bones, and vascular malformations. The involvement of the genitourinary tract and of the uterus in particular is extremely infrequent but relevant for possible consequences.

Methods

We performed an extensive review of the literature using the Pubmed, Scopus and ISI web of knowledge database to identify all cases of KTS with uterine involvement. The search was done using the MeSH term “Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome” AND “uterine” OR “uterus.” We considered publications only in the English language with no limits of time. We selected a total of 11 records of KTS with uterine involvement, including those affecting pregnant women.

Results

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome was described for the first time in the year 1900 in two patients with hemangiomatous lesions of the skin associated with varicose veins and asymmetric soft tissue and bone hypertrophy. Uterine involvement is a rare condition and can cause severe menorrhagia. Diagnosis is based on physical signs and symptoms. CT scans and MRI are first-choice test procedures to evaluate both the extension of the lesion and the infiltration of deeper tissues before treatment. The management of Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome should be personalized using careful diagnosis, prevention and treatment of complications.

Conclusion

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome is a rare vascular malformation with a wide variability of manifestations. There are no univocal and clear guidelines that suggest the most adequate monitoring of the possible complications of the disease. Treatment is generally conservative, but in case of recurrent bleeding, surgery may be needed.

Keywords: Uterus, uterine bleeding, Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, genitourinary, gynecological surgery

Introduction

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) is a rare vascular congenital disorder. It is associated with the classical triad of port-wine stains, abnormal overgrowth of soft tissues and bones, and vascular malformations (1). KTS involves most frequently the lower limbs and less commonly the upper extremity and trunk (2). Visceral involvement is rare but has been described in the colon, small bowel, bladder, kidney, spleen, liver, mediastinum and brain. We can also see finger anomalies and visceromegaly. The involvement of the genitourinary tract is extremely rare. In this article, we present an extensive review of the literature on patients with KTS and genital involvement.

Materials and Methods

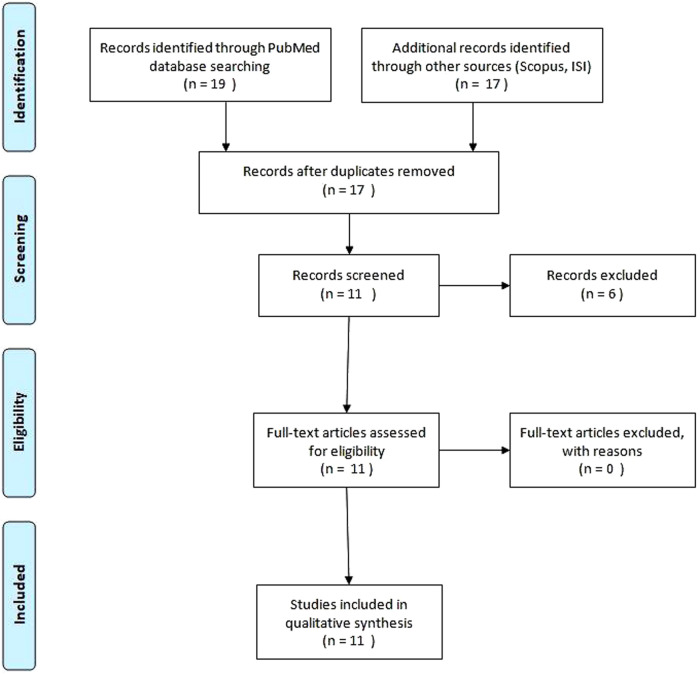

We performed an extensive review of the literature using the Pubmed, Scopus and ISI web of knowledge database to identify all cases of KTS with uterine involvement. The search was done using the MeSH term “Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome” AND “uterine” OR “uterus.” We considered publications only in the English language with no limits of time. We selected a total of 11 records of KTS with uterine involvement, including those affecting pregnant women (Figure 1). The data on patients are reported in Table 1 and include age, limb or trunk involvement, the presence of internal lesions and the management of vascular lesions.

Figure 1.

Systematic literature review to identify studies about Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome and uterine involvement.

Table 1.

Uterine involvement of Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome and respective treatments.

| Study | Characteristics | Age | Limb involvement | Trunk involvement | Internal lesions | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aronoff et al. | Female | 30 | Left upper extremities Left psoas muscle |

Chest wall, arms | Spleen, uterus | Hysterectomy |

| Markos et al. | Female | 26 | Right lower limb knee, hip | – | Uterus | Hormonal with levonorgestrel |

| Milman et al. | Female | 45 | – | – | Uterus | Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy VLS |

| Rodriguez Peña et al. | Female | 14 | Lower left limb that extended to the pelvic region. | – | Bladder and uterus | Selective arterial embolization of the internal and external iliac territories//laser endo-coagulation |

| Zhang et al. | Female in pregnancy | 24 | Left buttock left lower extremity |

– | Vulva Vagina |

Laparotomy followed by embolization of the bilateral internal iliac artery |

| Yara et al. | Female in pregnancy | 23 | Left leg | – | Uterus | Elective cesarean section |

| Sun et al. | Female in post menopause | 55 | Left leg with arteriovenous shunts | – | Vaginal wall | Interventional arteriovenous fistula occlusion operation |

| Verheijen, et al. | Female in pregnancy | 28 | Right popliteal region | – | Uterus | Cesarean section |

| Lawlor et al. | Female | 25 | Right lower extremity anal region and perineal skin | – | Uterus | Hormonal with levonorgestrel |

| Watermayer et al. (3) | Female in pregnancy | 21 | Left lower limb | – | Vulva, cervix and uterus | Cesarean section |

| Minguez et al. (4) | Female | 31 | Lower limb | – | Vulva and uterus | Sclerotherapy |

Results

In this review of the literature, a total of 11 patients with KTS and uterine involvement were evaluated. Their bladder and uterus were the most commonly affected organs, and all of them had a positive history of intermittent bleeding that manifested in the form of hematuria or menometrorrhagia. In 10 cases, we registered uterine and vaginal involvement. All patients had a history of severe menometrorrhagia with significant vascular abnormalities of the reproductive organs. Only in the cases reported by Markos (5) and Lawlor and Charles-Holmes (6), hormonal therapy with levonorgestrel alone was effective. In the other cases, conservative management failed, and the patients were treated with surgical procedures. In particular, the failure of conservative treatment included recurrent bleeding requiring repetitive hospitalization or massive hemorrhage resistant to transfusion. Aronoff and Roshon (7) described the case of a 30-year-old woman with KTS and Kasabach–Merritt syndrome who had disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with severe hemorrhage. The radiologic embolization of uterine arteries and subsequent abdominal hysterectomy was ineffective, and finally, bleeding was controlled with the use of intravenous low-dose heparin and antithrombin III. Milman et al. (8) described the case of a 45-year-old woman with KTS with abnormal uterine bleeding treated with total laparoscopic hysterectomy because of the smaller size of her uterus (15.7 × 6.9 × 5.3 cm). Rodriguez Peña and Ovando et al. (9) exposed the case of a 14-year-old female patient with macroscopic hematuria and metrorrhagia due to the presence of multiple angiomatous lesions in the bladder managed with a selective arterial embolization of the internal and external iliac territories and then with laser endo-coagulation of the bleeding foci. Metrorrhagia instead was controlled by the use of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) analogs. In nonpregnant women, postmenopausal vaginal bleeding from vaginal varices rarely occurs and is typically related to gynecological malignancies (10–12). Sun et al. (13) described a rare case of vaginal bleeding secondary to increased central venous pressure due to the presence of arteriovenous shunts in the leg of the patient. An arterial angiography was performed, and the arteriovenous shunts were partly closed by an interventional arteriovenous fistula occlusion operation. In the literature, a few cases of pregnancy in patients with KTS have been reported. Zhang et al. presented the case of a late puerperal hemorrhage in a patient with this syndrome, which became complicated with DIC, peritonitis and sepsis, and this patient was treated first with an emergency hysterectomy because of the occurrence of hemoperitoneum and later with bilateral internal iliac artery embolization to prevent the risk of recurrent bleeding (14). Yara et al. reported the case of a pregnant woman with KTS, complicated with diffuse venous malformation of the uterus, who underwent an elective cesarean section because of severe dystonia (15). Another case of pregnancy in a patient with KTS treated with an uncomplicated cesarean section was described by Verheijen et al. (16). This patient, in the course of her first pregnancy, developed a circumscript angiomatosis on the left and right sides of the uterus that extended into the cervix and that caused a slight growth retardation of the fetus. In KTS, the involvement of the urinary tract is up to 10% and hematuria, which occurs in more severe cases, is usually the initial clinical manifestation. Rubenwolf et al. (17) reported the clinical presentation and surgical management of a 9-year-old boy with extensive vascular malformations occupying more than two-thirds of the bladder lumen, which led to recurrent episodes of life-threatening gross hematuria. In this case, due to the extent of bladder involvement and the vulnerability of cystoscopy, conservative management was not possible, and surgical treatment with trigone sparing cystectomy and enterocystoplasty using an ileo-cecal segment was performed. Vulvar or vaginal vascular malformation is a rare manifestation of the KTS. Molkenboer and Hermans described the case of a woman with a vulvar swelling due to varicosis of the right labium removed by electrocoagulation (18).

Discussion

KTS or angio-osteodystrophy syndrome has been listed as a “rare disease.” Its incidence is estimated between 2 and 5 in 100,000 and is found equally in both sexes (19). The age of onset of the first manifestations is birth or the first year of life. This condition was described for the first time in the year 1900 by two French Physicians, Maurice Klippel and Paul Trenaunay, in two patients with hemangiomatous lesions of the skin associated with varicose veins and asymmetric soft tissue and bone hypertrophy (20). Today, these three major findings constitute the primary diagnostic criteria of the syndrome. Later, Parkes-Weber added the presence of arteriovenous fistulas to the symptomatology of KTS, and it represented a distinct disorder called Parkes–Weber syndrome (21). The etiology of this syndrome is still unknown. Generally, the disease occurs sporadically with no sex predilection, although some authors have proposed that KTS affects males more often than females (2, 22, 23). Vahidnezhad et al. hypothesized that KTS may result from mutations in PIK3CA, the gene involved in the construction of the enzyme PI3K (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase), cellular proliferation and migration, suggesting that KTS belonged to the PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS) (22, 24). Recently, several genetic studies reported sporadic translocations of chromosomes 5–11 and chromosomes 8–14 as the cause (25). Tian et al. proposed as a molecular pathogenic mechanism of the disease an angiogenic factor, called VG5Q, which causes an increase in angiogenesis when overexpressed (26). Patients with a mutation in the PIK3CA gene show an abnormal growth of the bones, soft tissues and blood vessels. The most common skin manifestation of the syndrome is represented by capillary malformations or “port-wine stains” that are often noted at birth. As reported by Jacob et al. in a study of 252 patients with KTS, capillary malformations (port-wine stains) were found in 246 patients (98%), varicosities or venous malformations in 182 (72%) and limb hypertrophy in 170 (67%), although the patients did not have all three symptoms at the same time (27). Capillary malformations are dilated telangiectatic vessels and appear in the upper dermis with a dermatomal distribution (28). These malformations do not tend to regress spontaneously with time but may cause hemorrhage and internal bleeding (29), especially in cases of visceral involvement such as the pleura, spleen, liver, bladder and colon (30, 31). Varicose veins are found in 76–100% of patients with KTS and may be distributed over extensive areas of the affected extremity, especially below the knee, on the lateral face of the thigh and occasionally in the pelvic region (31). Hypertrophy of the bones and soft tissues is present in a majority of patients with KTS and affects one or more limbs (32). Vascular abnormalities can also affect other organs, including the anterior chamber of the eye (glaucoma), retina (retinal varices, choroid angioma) and the central nervous system (the absence of deep cerebral veins, a dilation of the sinuses petrous and cavernous or hemimegalencephaly). Other central nervous system abnormalities are microcephaly, macrocephaly, cerebellar hemihypertrophy, cerebral atrophy and cerebral calcifications. Patients with the involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and the genitourinary tract have symptoms such as hematuria and/or hematochezia (33). The involvement of the gastrointestinal tract occurs in 20% of the patients and may be unnoticed in the absence of obvious signs. It most frequently affects the distal colon and the rectum, manifesting itself in the form of occult bleeding or massive hemorrhages (34). Genitourinary involvement occurs in severe cases, and vascular anomalies can affect external or visceral genitourinary systems. Furness et al. (35), in a study conducted on a large patient population with KTS, found that 23% with KTS (51 of 218) had cutaneous genitourinary involvement and 51% with KTS (111 of 218) had visceral genitourinary involvement with vascular malformations of the abdominal wall, pelvis or perineum. The presence of vascular abnormalities is not predictive of visceral involvement. For this reason, to avoid postoperative complications that may occur when these vascular abnormalities are inadvertently identified, all patients with KTS must be subjected to instrumental examinations for visceral vascular malformations before surgery. Gross hematuria from a visceral genitourinary source was reported in 1% of patients with KTS and is usually the first clinical sign of bladder involvement (34). Other sources of bleeding are external genitalia, urethra, kidney and ureter (35). The diagnosis is confirmed by radiological and cystoscopic studies. CT scan or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis evaluates the extent of vascular lesions and infiltration of deeper tissues. On cystoscopy, vascular lesions usually appear reddish blue, may appear sessile or pedunculated, flattened or lobulated and are more frequently localized on the anterior bladder wall and dome, but rarely in the trigone and the neck. During the procedure, a biopsy is not recommended because it can cause massive bleeding. The treatment of KTS-associated gross hematuria is still an object of study and is based on observation or surgical excision. Conservative management with intravenous hydration, transfusion and bladder irrigation using saline solution can be considered as the initial treatment for gross hematuria whenever possible. However, in the presence of refractory or life-threatening hematuria, a more invasive approach may be necessary. When vascular lesions are located extratrigonally, partial cystectomy is the standard surgical approach. Selective embolization of the internal iliac arteries can be a therapeutic alternative, but cases of relapse due to the development of collateral circulation and infarction of the bladder or prostate have been described in the literature (36). In refractory cases, laser coagulation and formalin instillation appear to be effective and should be attempted before any surgical intervention. Endoscopic management is not recommended as it may result in worsening hematuria (37). Uterine involvement is also an extremely rare condition, and there are only a few cases described in the literature. In a study of 218 patients with KTS conducted by Husmann et al. (33), only five patients had severe menorrhagia, and four of these had significant vaginal or uterine vascular abnormalities. Vascular lesions are usually confirmed by MRI, which evaluates the extension, the size and the anatomical relationships of the malformation. CT scan and/or MRI should always be performed before any therapeutic procedure, with the only exception of small and superficial localizations, for which ultrasonography is sufficient. Menorrhagia secondary to KTS vascular lesions can be well controlled with hormonal therapy (LHRH analogs and progestogens) (5), but in the presence of recurrent bleeding requiring repetitive hospitalization or massive hemorrhage resistant to transfusion, surgery may be needed. Hysterectomy is the treatment of choice in case of abnormal uterine bleeding. Laparoscopic hysterectomy represents a better surgical approach for less postoperative discomfort, a shorter hospital stay and a faster recovery, but in the presence of a very large uterus, open surgery remains the first-choice approach in most cases. Other factors that allow the feasibility of laparoscopy are the flexibility of the anterior abdominal wall, the residual intra-abdominal volume and the surgical experience of the team. Pregnancy is a rare event in women with this syndrome, and only a few cases are reported in the literature (14–16). It could become complicated with bleeding, DIC and thromboembolic events, so antithrombotic prophylaxis should be advised (38). In the event of complications arising during labor, an emergency cesarean section becomes necessary. How fertility can be preserved in order to avoid known vascular complications by surrogacy maternity has been reported. This is possible (3) using embryos obtained by a controlled ovarian stimulation and performing fertilization through intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Usually to avoid ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), it is better to freeze all by the vitrification system using gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist administration the day before human chorionic gonadotropin trigger (4, 39–42).

Conclusions

KTS is a very rare disease with a wide variability of manifestations. The typical vascular lesions are not progressive or proliferative, but the syndrome has a clinical course evolutionary type worsening in the course of life. The diagnosis is predominantly clinical based on careful anamnesis, physical signs and symptoms, but it must be integrated with radiographic examinations (such as the X-ray of the segment affected by vascular anomalies), with CT scan and MRI (which is the elective examination for vascular malformations), with a ultrasound of the internal organs. Although biopsy is contraindicated as it could cause massive bleeding, histology examination should be limited to cases where the imaging methods are not able to provide an accurate diagnosis and when a tumor lesion is suspected. The prognosis is linked to the presence of complications that appear to be more common when the cutaneous vascular anomalies are localized to the trunk or abdomen and have a map shape. In the literature, there are no univocal and clear guidelines that suggest the most adequate monitoring of the possible complications of the disease. Most of the authors focus on specific aspects of the syndrome such as urological and gynecological complications, on radiological diagnostics or on the genetic peculiarities of the disease. Management and diagnostic investigations of KTS should be personalized and guided by a multidisciplinary clinical evaluation of the patient. Treatment is generally conservative, but repeated transfusion and life-threatening bleeding episodes require surgical treatment. Certainly, a diversified and tailored multidisciplinary approach is necessary (43).

Funding

This article was published with funds from the school of General Surgery - Department of Surgical, Oncological and Oral Sciences, University of Palermo.

Author Contributions

Gaspare Cucinella and Giuseppe Gullo have contributed equally to the manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed significantly to the present research. CG: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data; also participated substantially in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. DBG: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data; also participated substantially in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. GG: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. RF: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. GG: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. ME: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. RG: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. BG: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. AG: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. BS: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. RG: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. AA: Participated substantially in conception, design and execution of the study, and in the analysis and interpretation of the data; also participated substantially in the drafting and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Atis A, Ozdemir G, Tuncer G, Cetincelik U, Goker N, Ozsoy S. Management of a Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome in pregnant women with mega-cisterna magna and splenic and vulvar varices at birth: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. (2012) 38:1331–4. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung HM, Chung HY, Lee SJ, Lee JM, Huh S, Lee JW, et al. Clinical experience of the Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Arch Plast Surg. (2015) 42(5):552–8. 10.5999/aps.2015.42.5.552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watermeyer SR, Davies N, Goodwin RI. The Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome in pregnancy. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. (2002) 109(11):1301–2. 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.01186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minguez JA, Aubá M, Olartecoechea B. Cervical prolapse during pregnancy and Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2009) 107(2):158. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markos AR. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome–a rare cause of severe menorrhagia. Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. (1987) 94(11):1105–6. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb02299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawlor F, Charles-Holmes S. Uterine haemangioma in Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. J R Soc Med. (1988) 81(11):665–6. 10.1177/014107688808101118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aronoff DM, Roshon M. Severe hemorrhage complicating the Klippel–Trénaunay–Weber syndrome. South Med J. (1998) 91(11):1073–5. 10.1097/00007611-199811000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milman T, Murji A, Papillon-Smith J. Abnormal uterine bleeding in a patient with Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2019) 26(5):791–3. 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez Peña M, Ovando E. Síndrome de Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber con compromiso vesical y uterino tratado por vía endoscópica y endovascular [Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome with vesical and uterine involvement treated by endoscopic and endovascular routes]. Medicina (B Aires). (2020) 80(1):84–86 (Spanish). PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cucinella G, Perino A, Romano G, Di Buono G, Calagna G, Sorce V, et al. Endometrial cancer: robotic versus laparoscopic treatment. Preliminary Rep. (2015) 37(6):283–87. 10.11138/giog/2015.37.6.283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capozzi VA, Rosati A, Rumolo V, Ferrari F, Gullo G, Karaman E, et al. Novelties of ultrasound imaging for endometrial cancer preoperative workup. Minerva Med. (2021) 112(1):3–11. 10.23736/S0026-4806.20.07125-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavaliere AF, Perelli F, Zaami S, D'Indinosante M, Turrini I, Giusti M, et al. Fertility sparing treatments in endometrial cancer patients: the potential role of the new molecular classification. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22(22):12248. 10.3390/ijms222212248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun J, Guo Y, Ma L, Qian Z, Lai D. An unusual cause of postmenopausal vaginal haemorrhage: a case report. BMC Womens Health. (2019) 19(1):31. 10.1186/s12905-019-0731-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Wang K, Mei J. Late puerperal hemorrhage of a patient with Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). (2019) 98(50):e18378. 10.1097/MD.0000000000018378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yara N, Masamoto H, Iraha Y, Wakayama A, Chinen Y, Nitta H, et al. Diffuse venous malformation of the uterus in a pregnant woman with Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome diagnosed by DCE-MRI. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. (2016) 2016:4328450. 10.1155/2016/4328450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verheijen RH, van Rijen-de Rooij HJ, van Zundert AA, de Jong PA. Pregnancy in a patient with the Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome: a case report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (1989) 33(1):89–94. 10.1016/0028-2243(89)90083-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubenwolf P, Roosen A, Gerharz EW, Kirchhoff-Moradpour A, Darge K, Riedmiller H. Life-threatening gross hematuria due to genitourinary manifestation of Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Int Urol Nephrol. (2006) 38(1):137–40. 10.1007/s11255-005-3154-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molkenboer JF, Hermans RH. Een vrouw met een vulvaire zwelling, een zeldzame uiting van het Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber-syndrome [A woman with a vulvar swelling, a rare manifestation of the Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. (2005) 149(41):2287–9. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alwalid O, Makamure J, Cheng QG, Wu WJ, Yang C, Samran E, et al. Radiological aspect of Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome: a case series with review of literature. Curr Med Sci. (2018) 38(5):925–31. 10.1007/s11596-018-1964-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klippel M, Trénaunay P. Ostéohypertrophique de variqueux de Du naevus. Archive générales de médecine, Paris. (1900) 3:641–72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volz KR, Kanner CD, Evans J, Evans KD. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: need for careful clinical classification. J Ultrasound Med. (2016) 35:2057–65. 10.7863/ultra.15.08007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vahidnezhad H, Youssefian L, Uitto J. Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome belongs to the PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS). Exp Dermatol. (2016) 25(1):17–19. 10.1111/exd.12826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma D, Lamba S, Pandita A, Shastri S. Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome–a very rare and interesting syndrome. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. (2015) 9:1–4. 10.4137/CCRPM.S21645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luks VL, Kamitaki N, Vivero MP, UllerW RR, Bovée JVMG, Rialon KL, et al. Lymphatic and other vascular malformative/overgrowth disorders are caused by somatic mutations in PIK3CA. J Pediatr. (2015) 166:1048–1054.e5. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oduber CEU, van der Horst CMAM, Hennekam RCM. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. (2008) 60:217–23. 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318062abc1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tian XL, Kadaba R, You SA, Liu M, Timur AA, Yang L, et al. Identification of an angiogenic factor that when mutated causes susceptibility to Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Nature. (2004) 427:640–5. 10.1038/nature02320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacob AG, Driscoll DJ, Shaughnessy WJ, Stanson AW, Clay RP, Gloviczki P. Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome: spectrum and management. Mayo Clin Proc. (1998) 73(1):28–36. 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63615-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viljoen D, Saxe N, Pearn J, Beighton P. The cutaneous manifestations of the Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. Clin Exper Dermatol. (1986) 12:12–17. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1987.tb01845.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howlett DC, Roebuck DJ, Frazer CK, Ayers B. The use of ultrasound in the venous assessment of lower limb Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Eur J Radiol. (1994) 18:224–26. 10.1016/0720-048X(94)90340-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gloviczki P, Hollier LH, Telander RL, Kaufman B, Bianco AJ, Stickler GB. Surgical implications of Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome. Ann Surg. (1983) 197:353–62. 10.1097/00000658-198303000-00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Servelle M. Klippel and Trenaunay’s syndrome, 768 operated cases. Ann Surg. (1985) 201:365–73. 10.1097/00000658-198503000-00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin Lindenauer S. The Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: varicosity, hypertrophy and hemangioma with no arterio-venous fistula. Ann Surg. (1965) 162:303–14. 10.1097/00000658-196508000-00023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husmann DA, Rathburn SR, Driscoll DJ. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: incidence and treatment of genitourinary sequelae. J Urol. (2007) 177:1244–49. 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Servelle M, Bastin R, Loygue J, Montagnani A, Bacour F, Soulie J. Hematuria and rectal bleeding in the child with Klippel and Trénaunay syndrome. Ann Surg. (1976) 183:418–28. 10.1097/00000658-197604000-00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furness PD, 3rd, Barqawi AZ, Bisignani G, Decter RM. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: 2 case reports and a review of the literature. J Urol. (2001) 166:1418. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65798-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kato M, Chiba Y, Sakai K, Orikasa S. Endoscopic neodymium:yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser irradiation of a bladder hemangioma associated with Klippel–Weber syndrome. Int J Urol. (2000) 7:145–8. 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2000.00150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klein TW, Kaplan GW. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome associated with urinary tract hemangioma. J Urol. (1975) 114:596–600. 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)67092-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horbach SE, Lokhorst MM, Oduber CE, Middeldorp S, van der Post JA, van der Horst CM. Complications of pregnancy and labour in women with Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. (2017) 124(11):1780–8. 10.1111/1471-0528.14698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin JR, Pels SG, Paidas M, Seli E. Assisted reproduction in a patient with Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: management of thrombophilia and consumptive coagulopathy. J Assist Reprod Genet. (2011) 28(3):217–9. 10.1007/s10815-010-9526-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papatheodorou A, Vanderzwalmen P, Panagiotidis Y, Petousis S, Gullo G, Kasapi E, et al. How does closed system vitrification of human oocytes affect the clinical outcome? A prospective, observational, cohort, noninferiority trial in an oocyte donation program. Fertil Steril. (2016) 106(6):1348–55. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gullo G, Petousis S, Papatheodorou A, Panagiotidis Y, Margioula-Siarkou C, Prapas N, et al. Closed vs. open oocyte vitrification methods are equally effective for blastocyst embryo transfers: prospective study from a sibling oocyte donation program. Gynecol Obstet Invest. (2020) 85(2):206–12. 10.1159/000506803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prapas Y, Ravanos K, Petousis S, Panagiotidis Y, Papatheodorou A, Margioula-Siarkou C, et al. GnRH antagonist administered twice the day before hCG trigger combined with a step-down protocol may prevent OHSS in IVF/ICSI antagonist cycles at risk for OHSS without affecting the reproductive outcomes: a prospective randomized control trial. J Assist Reprod Genet. (2017) 34(11):1537–45. 10.1007/s10815-017-1010-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.La Rosa VL. Psychological impact of gynecological diseases: the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2018) 30:23–26. 10.14660/2385-0868-86 [DOI] [Google Scholar]