Abstract

Background

More than half of the global population is not effectively covered by any type of social protection benefit and women's coverage lags behind. Most girls and boys living in low‐resource settings have no effective social protection coverage. Interest in these essential programmes in low and middle‐income settings is rising and in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic the value of social protection for all has been undoubtedly confirmed. However, evidence on whether the impact of different social protection programmes (social assistance, social insurance and social care services and labour market programmes) differs by gender has not been consistently analysed. Evidence is needed on the structural and contextual factors that determine differential impacts. Questions remain as to whether programme outcomes vary according to intervention implementation and design.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to collect, appraise, and synthesise the evidence from available systematic reviews on the differential gender impacts of social protection programmes in low and middle‐income countries. It answers the following questions:

-

1.

What is known from systematic reviews on the gender‐differentiated impacts of social protection programmes in low and middle‐income countries?

-

2.

What is known from systematic reviews about the factors that determine these gender‐differentiated impacts?

-

3.

What is known from existing systematic reviews about design and implementation features of social protection programmes and their association with gender outcomes?

Search Methods

We searched for published and grey literature from 19 bibliographic databases and libraries. The search techniques used were subject searching, reference list checking, citation searching and expert consultations. All searches were conducted between 10 February and 1 March 2021 to retrieve systematic reviews published within the last 10 years with no language restrictions.

Selection Criteria

We included systematic reviews that synthesised evidence from qualitative, quantitative or mixed‐methods studies and analysed the outcomes of social protection programmes on women, men, girls, and boys with no age restrictions. The reviews included investigated one or more types of social protection programmes in low and middle‐income countries. We included systematic reviews that investigated the effects of social protection interventions on any outcomes within any of the following six core outcome areas of gender equality: economic security and empowerment, health, education, mental health and psychosocial wellbeing, safety and protection and voice and agency.

Data Collection and Analysis

A total of 6265 records were identified. After removing duplicates, 5250 records were screened independently and simultaneously by two reviewers based on title and abstract and 298 full texts were assessed for eligibility. Another 48 records, identified through the initial scoping exercise, consultations with experts and citation searching, were also screened. The review includes 70 high to moderate quality systematic reviews, representing a total of 3289 studies from 121 countries. We extracted data on the following areas of interest: population, intervention, methodology, quality appraisal, and findings for each research question. We also extracted the pooled effect sizes of gender equality outcomes of meta‐analyses. The methodological quality of the included systematic reviews was assessed, and framework synthesis was used as the synthesis method. To estimate the degree of overlap, we created citation matrices and calculated the corrected covered area.

Main Results

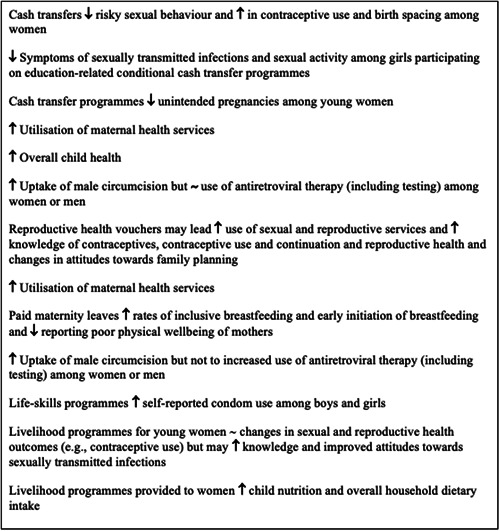

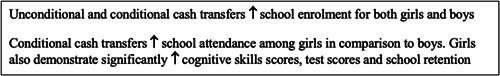

Most reviews examined more than one type of social protection programme. The majority investigated social assistance programmes (77%, N = 54), 40% (N = 28) examined labour market programmes, 11% (N = 8) focused on social insurance interventions and 9% (N = 6) analysed social care interventions. Health was the most researched (e.g., maternal health; 70%, N = 49) outcome area, followed by economic security and empowerment (e.g., savings; 39%, N = 27) and education (e.g., school enrolment and attendance; 24%, N = 17). Five key findings were consistent across intervention and outcomes areas: (1) Although pre‐existing gender differences should be considered, social protection programmes tend to report higher impacts on women and girls in comparison to men and boys; (2) Women are more likely to save, invest and share the benefits of social protection but lack of family support is a key barrier to their participation and retention in programmes; (3) Social protection programmes with explicit objectives tend to demonstrate higher effects in comparison to social protection programmes without broad objectives; (4) While no reviews point to negative impacts of social protection programmes on women or men, adverse and unintended outcomes have been attributed to design and implementation features. However, there are no one‐size‐fits‐all approaches to design and implementation of social protection programmes and these features need to be gender‐responsive and adapted; and (5) Direct investment in individuals and families' needs to be accompanied by efforts to strengthen health, education, and child protection systems. Social assistance programmes may increase labour participation, savings, investments, the utilisation of health care services and contraception use among women, school enrolment among boys and girls and school attendance among girls. They reduce unintended pregnancies among young women, risky sexual behaviour, and symptoms of sexually transmitted infections among women. Social insurance programmes increase the utilisation of sexual, reproductive, and maternal health services, and knowledge of reproductive health; improve changes in attitudes towards family planning; increase rates of inclusive and early initiation of breastfeeding and decrease poor physical wellbeing among mothers. Labour market programmes increase labour participation among women receiving benefits, savings, ownership of assets, and earning capacity among young women. They improve knowledge and attitudes towards sexually transmitted infections, increase self‐reported condom use among boys and girls, increase child nutrition and overall household dietary intake, improve subjective wellbeing among women. Evidence on the impact of social care programmes on gender equality outcomes is needed.

Authors' Conclusions

Although effectiveness gaps remain, current programmatic interests are not matched by a rigorous evidence base demonstrating how to appropriately design and implement social protection interventions. Advancing current knowledge of gender‐responsive social protection entails moving beyond effectiveness studies to test packages or combinations of design and implementation features that determine the impact of these interventions on gender equality. Systematic reviews investigating the impact of social care programmes, old age pensions and parental leave on gender equality outcomes in low and middle‐income settings are needed. Voice and agency and mental health and psychosocial wellbeing remain under‐researched gender equality outcome areas.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Social protection programmes appear to have higher impacts on women and girls than men and boys

Social protection programmes appear to have higher impacts on women and girls, who more likely than boys and men to save, invest and share the benefit from social protection programmes.

1.2. What is this review about?

Gender and age determine how people experience opportunities, vulnerabilities and risks. Social protection programmes, such as cash transfers, pensions and unemployment benefits aim to tackle poverty and adversity, manage risks and improve quality of life from childhood through to old age.

While social protection programmes do not negatively impact women or men, design and implementation features may lead to adverse outcomes. However, there is no one‐size‐fits‐all approach to design and implementation of social protection programmes and these features should explicitly address gender differences.

This systematic review of reviews contributes to a clearer picture of the differential impact of social protection on women and men, and girls and boys, in low‐ and middle‐income countries. It also contributes to translating this knowledge into policy actions that improve gender equality outcomes across the life‐course.

1.3. What studies are included?

The review includes 70 systematic reviews, representing a total of 3289 studies investigating 4 different types of social protection programmes (defined here as social assistance, social insurance, labour market and social care programmes) in 121 countries.

What is the aim of this review?

This systematic review of reviews summarises the evidence from 70 systematic reviews on the differential impacts of social protection programmes on women and men, and boys and girls in low‐ and middle‐income countries. The authors also reflect on implications for policy, programming, practice and research gaps arising from the evidence.

1.4. What are the main findings of this review?

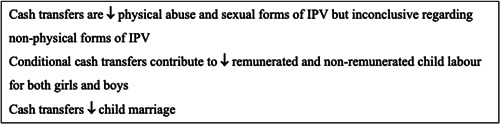

Social assistance programmes improve labour participation, saving, investment, utilisation of health care services and contraception use among women, improve uptake of male circumcision, increase school enrolment among boys and girls and school attendance among girls. Such programmes also reduce unintended pregnancies among young women, risky sexual behaviour, and symptoms of sexually transmitted infections among women.

Social insurance programmes improve the utilisation of sexual, reproductive, and maternal health services, and knowledge of reproductive health; improve changes in attitudes towards family planning; increase uptake of male circumcision; increase rates of inclusive breastfeeding and early initiation of breastfeeding and improve physical wellbeing of mothers.

Labour market programmes improve labour participation among women receiving benefits, improve savings, ownership of assets, earning capacity among young women, and knowledge and attitudes towards sexually transmitted infections.

Labour market programmes also increase self‐reported condom use among boys and girls, increase child nutrition and overall household dietary intake, improve subjective wellbeing, economic, social and political empowerment and self‐confidence and social skills among women, and increase respect from family members in some settings.

Evidence on the impact of social care programmes on gender equality outcomes is scarce, so it was not possible to find patterns across systematic reviews.

Despite positive effects across multiple outcomes, social protection programmes with explicit objectives tend to demonstrate higher effects in comparison to social protection programmes with broad objectives.

Direct investment in individuals and families via social protection programmes must be accompanied by efforts to strengthen health, education and protection systems.

1.5. What do the findings of this review mean?

Important progress has been made on identifying social protection interventions that effectively address gender equality outcomes. Reviews acknowledge the crucial role of addressing gender differences in design and implementation of programmes.

There are substantial evidence gaps on the impact of social care programmes, parental leave and old age pensions on gender equality outcomes, and within the outcome areas of voice and agency, and mental health and psychosocial wellbeing.

There is a clear recognition of the potential negative impact of inadequate and unfit design and implementation features. Questions remain as to how to appropriately design and implement social protection interventions across different contexts and according to each population.

Advancing current knowledge of gender‐responsive social protection interventions requires moving beyond effectiveness studies to test packages or combinations of design and implementation features.

1.6. How up to date is this review?

All searches were conducted between 10 February and 1 March 2021 to retrieve all systematic reviews published within the last 10 years with no language restrictions.

2. BACKGROUND

Gender and age determine how people experience opportunities, vulnerabilities, and risks. In low‐income settings, adolescent girls are at higher risk of child marriage, which further hinders school enrolment and attendance, while adolescent boys are more likely to engage or be forced into child labour (Jones, 2019). During and after natural disasters, children and older adults are more vulnerable to protection harms and health risks such as poor nutrition and violence (Karunakara & Stevenson, 2012; Seddighi et al., 2017). Adult women tend to have fewer economic resources to cope with crises such as sickness or death of family members, extreme weather events or emergencies (Wenham et al., 2020) and adult men are also affected by restrictive gender norms which translate into negative social and health outcomes for all (Heise et al., 2019).

Social protection programmes, such as cash transfers, pensions, or unemployment benefits, aim to tackle poverty and adversity, manage risks, and improve quality of life from childhood through to old age. Increased socioeconomic insecurity, inadequate resources and limited access to services mean that demand for social protection is higher in low‐ and middle‐income settings. Inequality, economic insecurity and the socioeconomic shocks triggered by the COVID‐19 pandemic have widened pre‐existing gaps and further underscored the critical importance of achieving universal social protection (International Labour Organization, 2021).

Various systematic reviews point to positive effects of social protection programmes on food security (Bastagli et al., 2016), school enrolment and attendance (Baird et al., 2014), sexual and reproductive health (Owusu‐Addo et al., 2018), poverty reduction (Owusu‐Addo & Cross, 2014), access to health (Erlangga et al., 2019; Habib et al., 2016), employment (Chinen et al., 2017; Kluve, 2010) and child development (Leroy et al., 2012) in low and middle‐income countries (LMICs). Gender differences on the effectiveness of social protection programmes have been identified in some settings (Cluver et al., 2016; Gibbs et al., 2012; Manley et al., 2013). In addition, programme design and implementation may have different intended and unintended consequences for women and men at varying ages and stages of their life (Holmes & Jones, 2010).

Women's coverage of social protection programmes lags behind men's coverage (International Labour Organization, 2021). Globally 26.5% of women and 34.3% of men are legally covered by comprehensive social security systems that include a full range of benefits such as child and family benefits and old age pensions (International Labour Organization, 2021). These coverage gap can be explained by structural barriers, often associated with low labour force participation, unemployment, and informal employment (International Labour Organization, 2021). Additionally, most girls and boys still have no effective social protection coverage. According to the 2021, ILO World Social Protection Report only 26.4% of children globally receive social protection benefits, with significant regional disparities (International Labour Organization, 2021). The current evidence on the benefits and risks of social protection across gender (i.e., girls and boys, women, and men) in LMICs is yet to be consistently appraised and systematically examined. Evidence on whether the impact of different social protection programmes (i.e., social assistance, social insurance and care services and labour market programmes) differ by gender has not been synthesised and analysed. Research is needed on the contextual and structural factors that determine these differential impacts. Notably, questions remain as to whether programme outcomes vary according to intervention implementation and design. As a result, governments and organisations seeking to design, implement, de‐implement, scale up, down or close social protection programmes in LMICs face challenges when examining the evidence on social protection as a whole and its impact on gender equality indicators.

The primary aim of this review is to synthesise evidence from systematic reviews on the differential gender impacts of social protection programmes. In doing so, this review places itself at the intersection of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1 (end poverty in all its forms everywhere) and 5 (achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls). In addition, this review informs specific targets within the rest of the SDG Agenda, such as health (target 3.8), decent work and economic growth (target 8.5) and equality (target 10.4). In the context of meeting these goals, it synthesises the evidence on social protection by gender to inform the use, design, and implementation of programmes in LMICs, contributes to building the evidence‐base of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and strengthening national initiatives for achieving gender equality and reducing poverty.

2.1. Description of the intervention

More than half of the global population is not effectively covered by any type of social protection benefit, with very low coverage in Africa (17.4%), Arab States (40%) and Asia and the Pacific (44.1%) compared to Europe and Central Asia, and the Americas (83.9% and 64.3%, respectively) (International Labour Organization, 2021). Only 44.9% of women with new‐borns receive maternity cash benefits that provide them with income security during this critical period. Just 18.6% of unemployed workers worldwide have effective coverage for unemployment and 33.5% of people with severe disabilities receive a disability benefit (International Labour Organization, 2021). Effective pension coverage for older women and men stands at 77.5% of all persons above retirement age worldwide (International Labour Organization, 2021).

However, in LMICs investment and interest in these interventions is rising. The number of LMICs with social safety nets has doubled from 72 to 149 in the last two decades (World Bank, 2017). Examples of such social protection programmes include food for education programmes (Tanzania), scholarships for low‐income families (Guatemala), electricity and fuel subsidies for low‐income households (Cambodia), and noncontributory old age pensions (Mexico).

While there is no single definition of social protection, it is hereby understood as ‘a set of policies and programmes aimed at preventing or protecting all people against poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion throughout their lifecycle, with an emphasis towards vulnerable groups’ (UNICEF, 2019; p. 2; SPIAC‐B, 2012). As such, social protection aims to both avert and provide relief from poverty and adversity (Devereux & Sabates‐Wheeler, 2004). Social protection programmes can be provided by public organisations or bodies with or without collaboration of nongovernmental organisations or private institutions. Programmes implemented solely by private organisations or nongovernmental organisations without government affiliation are hereby not considered part of social protection (UNICEF, 2019). Characteristics such as recipient, duration, frequency, and rates of social protection programme varies according to the conditions and socioeconomic disadvantages each programme aims to address. The field of social protection can be conceptualised or divided into four areas or categories (i.e., social assistance, social insurance, labour market programmes and social care) drawing from various international categorisations such as the Interagency Social Protection Assessment and UNICEF Global Social Protection Framework (SPIAC‐B, 2012; UNICEF, 2019), as defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Social protection categories, definitions and examples

| Category | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Social assistance | Cash and near cash benefits, in‐kind benefits, where receipt is not determined by individual contributions (i.e., noncontributory and publicly provided) |

|

| Social insurance | Cash or near cash benefits where eligibility is determined based on personal contributions or employer contributions (i.e., contributory schemes) |

|

| Labour market programmes | Programmes and services that support employment and livelihoods and enable families to have enough income while ensuring provision and time for quality childcare. |

|

| Social care services | Direct outreach, case management and referral services to children and families |

|

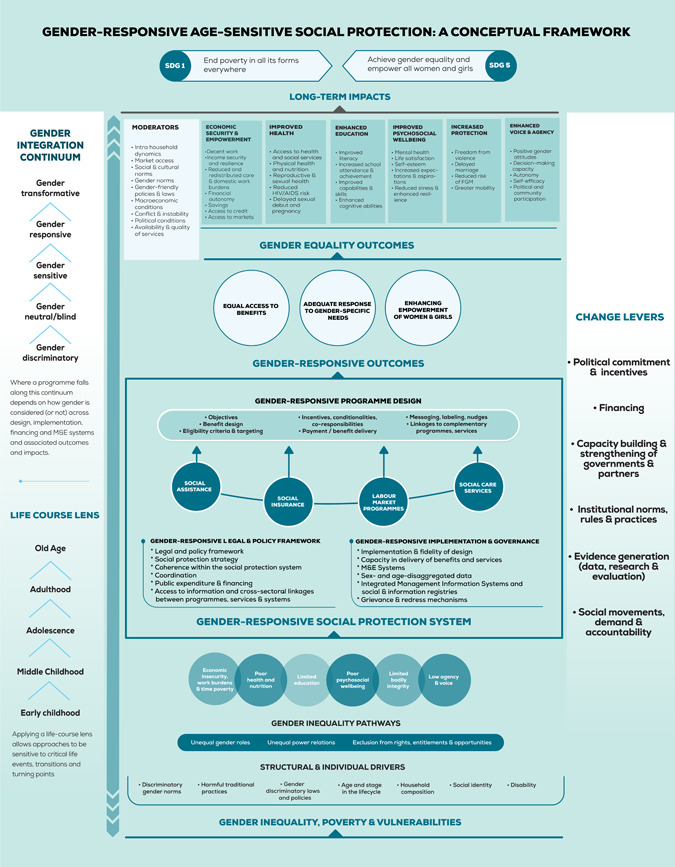

2.2. How the intervention might work

The Gender‐Responsive Age‐Sensitive Social Protection Conceptual Framework (Figure 1—Reprinted with authors' permission) guides this review and delineates how social protection is hypothesised to lead to poverty reduction and promote long‐term and sustained gender equality (UNICEF Office of Research—Innocenti, 2020). Building on existing conceptual and theoretical efforts (Holmes & Jones, 2013), the framework starts by acknowledging that poverty and vulnerabilities are gendered, can change at different transitions and turning points throughout the life course, as well as accumulate over time. It reflects structural and individual‐level drivers of gender inequality that result in unequal outcomes for girls and women relative to boys and men, with long‐term negative impacts for them, and for sustainably reducing poverty and enhancing gender equality. It outlines moderating factors, which are dependent on context and programme design components. Integrating analysis by age and gender allows for a life course lens on gendered inequalities in relation to poverty and vulnerability.

Figure 1.

Gender‐responsive age‐sensitive social protection: a conceptual framework

Second, the framework maps out the opportunities and mechanisms through which social protection systems may address gendered risks and vulnerabilities through specific programmes across the social protection delivery cycle, including the legal and policy framework, programme design, implementation, governance, and financing. The conceptual framework deliberately takes a macro‐view, acknowledging the importance of a systemic and institutional perspective, beyond project or programme level pathways.

Third, the framework applies a Gender Integration Continuum (GIC), a tool to distinguish different degrees of integration of gender considerations across the social protection delivery cycle, ranging from gender‐discriminatory to gender‐transformative. The GIC helps assess the extent to which social protection systems and programmes are designed and delivered in a way that explicitly addresses gender inequality. It is based on a recognition that programmatic or policy attention to addressing gender inequality depends to a great extent on the prior understanding of prevailing gender inequalities and norms that need to be transformed through purposive actions. It thus shows how gender‐responsive social protection, by specifically addressing gendered poverty, risks, and vulnerabilities, can strengthen social protection system‐level outcomes, such as improved coverage and adequacy of social protection systems, as well as individual programme results, and thereby contribute to a range of gender equality outcomes, including economic security and empowerment, health, and education. In turn, the achievements of social protection are conceptualised to contribute to SDGs 1 and 5.

2.3. Why it is important to do this review

There is a large body of empirical evidence investigating the impact of social protection programmes. A myriad of robust systematic reviews have sought to clarify the impact of social protection programmes on women and men, across different age groups (e.g., Baird et al., 2014; Bassani et al., 2013; Bastagli et al., 2016; Buller et al., 2018; Chinen et al., 2017; Dickson & Bangpan, 2012; Durao et al., 2020; Haberland et al., 2018; Kalamar et al., 2016; Kluve et al., 2017; Langer et al., 2018; Målqvist et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2014; Pega et al., 2015; Tripney et al., 2013; van Hees et al., 2019; Yoong, Rabinovich and Diepeveen 2012). The results, however, are dispersed with reviews focusing on various specific sub‐types of social protection (e.g., labour market programmes, cash transfers), women and/or men, in different regions, and with some offering conflicting or discordant results regarding the impact of social protection interventions. Although various systematic reviews have gathered evidence on various areas of social protection in LMICs, evidence on the whole field is yet to be examined. For the results of a scoping exercise conducted to inform this systematic review, see the review protocol (Perera et al., 2021).

Systematic reviews summarise the best available evidence relevant to a specific research question. They are the most comprehensive way to collate all the relevant evidence on a specific topic or theme (Bakrania, 2020). The accelerated increase of systematic review publishing creates a growing interest in summarising and analysing systematic reviews. Systematic reviews of reviews help gather a wide range of evidence on interventions, enable large comparisons and can help clarify discrepant systematic review results (Polanin et al., 2017). By considering only the highest level of evidence (i.e., systematic reviews), they offer a means to review the evidence base and to obtain a clear understanding of a broad topic area (Aromataris et al., 2015). In addition, systematic reviews of reviews provide conclusions regarding research trends and gaps, making them also useful for researchers (Duvendack & Mader, 2019; Polanin et al., 2017).

A systematic review of reviews allows us to identify patterns within and across programme types and outcomes to understand whether and how social protection programmes distinctively impact women and men. This systematic review of reviews generates a clearer picture of the available evidence on the differential impact of social protection on women and men, and girls and boys, and translates this knowledge into policy actions that improve gender equality outcomes across the life‐course. As such, this review aims to inform the decisions of donors, policymakers and programme managers seeking to establish social protection programmes. More specifically, the findings of this review provide valuable insights for different components of UNICEF's and strategic partners' programmes.

3. OBJECTIVES

This review aims to systematically collect, appraise, map, and synthesise the evidence from systematic reviews on the differential gender impacts of social protection programmes in LMICs as well as findings on the design and implementation of these programmes. Therefore, it answers the following questions:

-

1.

What is known from systematic reviews on the gender‐differentiated impacts of social protection programmes in LMICs?

-

2.

What is known from systematic reviews about the factors that determine these gender‐differentiated impacts?

-

3.

What is known from existing systematic reviews about design and implementation features of social protection programmes and their association with gender outcomes?

4. METHODS

4.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

4.1.1. Types of studies

We included systematic reviews, irrespective of publication status and the language they were published in, that synthesise and analyse evidence from qualitative, quantitative or mixed‐methods studies. As defined by the Campbell Collaboration: ‘A systematic review summarises the best available evidence on a specific question using transparent procedures to locate, evaluate, and integrate the findings of relevant research’ (Campbell Collaboration, 2014; p. 6). In addition, we adopted the following additional criteria, as outlined by Higgins & Green, 2011;

A set of clearly stated objectives and pre‐defined eligibility criteria

A methodology that is clearly defined allowing reproducibility

A search strategy that allows the identification of studies meeting the pre‐defined eligibility criteria

A quality appraisal of included studies

A systematic synthesis, including systematic reviews that adopt a meta‐analytical, narrative, or thematic approach

Co‐registered reports were treated as duplicate reviews with data extracted from the most detailed version. Similarly, when multiple versions of the same systematic review were identified, the latest and most comprehensive version was considered for inclusion. Protocols of systematic reviews were initially included and excluded once the full review was identified. Authors were contacted when the final review was not identified to inquire whether the relevant reviews of interventions were close to completion and assess the prepublication version for inclusion in our systematic review of reviews. Other systematic reviews of reviews identified through our search were excluded.

4.1.2. Types of participants

We include systematic reviews that analyse the outcomes of social protection programmes on women, men, girls, and boys in LMICs. As we are interested in the impacts of social protection during different stages of the life course, no restrictions were set on age. Studies that do not report gender‐disaggregated results of the impact of these programmes were excluded.

4.1.3. Types of interventions

To be included in this review, systematic reviews had to investigate one or more types of social protection programmes. No restrictions were imposed on intervention comparison (e.g., control or waitlisted groups or regions, other interventions) to determine the relative impact of social protection interventions.

4.1.4. Types of outcome measures

Our review is informed by the Gender‐Responsive Age‐Sensitive Social Protection Conceptual Framework, which establishes the following outcome areas of gender equality:

Economic security and empowerment: Right to access opportunities and decent work, including the ability to participate equally in existing markets; control over and ownership of resources and assets (including one's own time); reduced burden of unpaid care and domestic work, and meaningful participation in economic decision‐making at all levels.

Health: Right to live healthily, including sexual and reproductive health rights, and right to access safe, nutritious and enough food. This is also concerned with information, knowledge and awareness of health issues, and access to and expenditure on health services.

Education: Right to inclusive and equitable quality education, leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes, including cognitive skills and knowledge; right, access to and expenditure on lifelong learning opportunities.

Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing: A state of complete physical, mental, and social well‐being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in which an individual realises their own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to contribute to his or her community.

Safety and protection: Freedom from all forms of violence (physical, sexual, and psychological violence, including controlling behaviour), exploitation, abuse, and neglect, including harmful practices (e.g., child, early and forced marriage, FGM) and child labour (including children's unpaid care and domestic work).

Voice and agency: Ability to speak up and be heard, and to articulate one's views in a meaningful way (voice), and to make decisions about one's own life and act on them at all levels (agency).

In this systematic review of reviews, we include all systematic reviews that investigate any outcomes within any of these core areas. The use of core outcome areas has been recommended as a strategy to prevent the loss of information in systematic reviews (Saldanha et al., 2020). Narrowing down our study to a specific set of gender outcomes (e.g., increased school attendance, delayed marriage, income security) could result in missed opportunities to understand the impact of social protection on gender equality.

We report on contextual and structural factors, and programme design and implementation features determining the impact of social protection programmes. Implementation is understood as the process of fulfilling or carrying out a social protection intervention into effect (Peters et al., 2014). Intervention design or development is the period or process of developing an intervention to ‘the point where it can reasonably be expected to have worthwhile effect’ (Craig & Petticrew, 2013; p. 9) that usually consists of making decisions about the content, format and delivery and ends with the production of a document or manual describing the intervention and how it should be delivered (O'Cathain et al., 2019).

4.1.5. Primary outcomes

We did not distinguish between primary or secondary outcomes, and we did not impose restrictions based on the duration of follow‐up.

4.1.6. Types of settings

The reviews included in our systematic review of reviews investigate social protection programmes in LMICs, as defined by the World Bank in 2019 (Cochrane, 2020). Where systematic reviews and meta‐analyses include evidence from high‐income countries, we have only considered the findings that are presented for LMICs; we also consider systematic reviews covering regions within LMICs (e.g., Sub‐Saharan Africa). Reviews that do not disaggregate results by country, region or national income level were not included.

4.1.7. Timeframe

A seminal report published in 2010 titled Rethinking social protection using a gender lens, identified the need to systematically appraise the evidence on social protection and gender equality (Holmes & Jones, 2010). Since the report points to the absence of systematic reviews on the field, our searches were limited to 2010 onwards.

4.2. Search methods for identification of studies

Our search strategy aimed to find both published and unpublished literature from a wide range of sources (i.e., bibliographic databases, institutional websites, and libraries) (Kugley et al., 2017). The search techniques used were subject searching, reference list checking, citation searching and expert consultations.

We gathered evidence from systematic reviews on the impact of these programmes on gender‐related outcomes, any determinants of these impacts as well any available evidence on the design and implementation of these interventions.

4.2.1. Electronic searches

The following academic databases were searched:

Web of Science

Academic Search Complete (EBSCO)

International Bibliography of the Social Science Database via ProQuest

Africa‐Wide via EBSCOHOST

ERIC (Education Resources Information Centre)

Medline Complete via EBSCOHOST

PsycINFO via EBSCOHOST

EconLit via EBSCOHOST

In addition, a search for more reviews, especially unpublished studies and grey literature was conducted for the following institutional websites, libraries, and sources of grey literature:

Campbell Collaboration Library

World Bank eLibrary (https://elibrary.worldbank.org/)

EPPI‐Centre

IDEAS/RePEC (https://ideas.repec.org/)

3ieimpact evidence portal

ILO (International Labor Organization)

SSRN (Social Science Research Network)

Research for Development Outputs (https://www.gov.uk/research-for-development-outputs)

Asian Development Bank (https://www.adb.org/about/library)

Africa Centre for Evidence—Systematic Review Repository

Social Systems Evidence (socialsystemsevidence.org)

We ran searches in Web of Science (3,860hits), Academic Search Complete (370hits), Social Science database (39hits), Africa‐Wide via EBSCOHOST (297hits) World Bank elibrary (127hits), ERIC (50hits), Medline Complete (54hits), PsycINFO (391hits) and EconLit (188hits). The search strategies were developed using keywords and index terms (controlled vocabulary) relevant to the study concepts. Each search strategy consisted of the study concepts divided into four parts: intervention and related terms (adapted from the GRASSP Conceptual Framework—Figure 1), study design (search filter for systematic review database by 3ie), population and LMICs (adapted from Cochrane, 2020). The search strings were adapted for each database to retrieve all systematic reviews published within the last 10 years with no language restrictions. All searches were conducted between 10 February and 1 March 2021. See the review protocol for the full search strategies of academic databases (Perera et al., 2021).

4.2.2. Searching other resources

This systematic review is part of a research programme investigating Gender‐Responsive Age‐Sensitive Social Protection (GRASSP) systems to enhance gender equality outcomes in low and middle‐income settings. This review is guided by the feedback and input of the GRASSP External Advisory Group (EAG). The group is composed of academics and practitioners, with expertise on social protection and gender, from UNICEF and partner organisations as well as academic institutions, including ILO, ODI, LSE and the World Bank. The EAG has provided expert advice on the subject areas of the review (i.e., gender and social protection) throughout different steps of the systematic review process. The role of the EAG members consisted of revising the search strategy, identifying systematic reviews not retrieved through the searches, providing feedback on the results of the review, as well as providing suggestions for increasing uptake and communication of findings. Experts from the EAG were consulted via e‐mail to identify systematic reviews not retrieved through the database and websites searches. In addition, reference lists of included reviews were screened to identify additional, potentially relevant, records.

4.3. Data collection and analysis

4.3.1. Description of methods used in systematic reviews

Systematic reviews have sought to clarify the impacts of social protection programmes on gender outcomes as well as aspects of their design and implementation, using quantitative and qualitative findings from primary studies. Therefore, we adopt a broad scope to synthesise evidence from reviews investigating social protection programmes, regardless of their methodology or epistemological approach.

4.3.2. Criteria for determination of independent reviews

A prevalent challenge of systematic reviews of reviews is the inclusion of systematic reviews that address similar research questions or synthesise evidence on similar and/or related interventions, which, may include some of the same underlying primary studies. The potential for ‘overlap' in primary studies between included systematic reviews introduces a risk of bias, by including the same primary study's results multiple times. As suggested by Pollock et al. (2021); in this review the degree of overlap is estimated by:

Creating a citation matrix to visually demonstrate the percentage of overlap across each of the four intervention areas.

Computing the Corrected Covered Area (CCA) (Pieper et al., 2014) as a measure of overlap by dividing the frequency of repeated occurrence of the index publication in other reviews by the product of index publications and reviews, reduced by the number of index publications.

Describing the percentage of overlapping primary studies and CCA, and discussing whether and how overlap affects the results reported in the systematic review of reviews.

Briefly, the CCA is calculated with the following equation: where N is the sum of the number of primary studies in each review, r is the total number of primary studies, and c is the number of reviews. To assess this bias, we calculated the CCA of every two included systematic reviews in the four intervention areas, as a measure of overlap, by dividing the frequency of repeated occurrence of the index publication in other reviews by the product of index publications and reviews, reduced by the number of index publications. We listed all primary studies included in the systematic reviews and count the CCA of every two systematic reviews in four intervention areas respectively. A CCA score of less than 5% is regarded as a slight overlap, 5%–9.9% as moderate overlap, 10%–14.9% as high overlap, and over 15% as a very high level of overlap (Pieper et al., 2014).

When discussing possible overlap, is also important to consider independence from other systematic reviews of reviews. Duvendack and Mader (2019) conducted the first systematic review of reviews of the Campbell Collaboration and set a precedent for the use of the systematic review of reviews methodology to better inform the decisions of development donors, policymakers, and programme managers. This systematic review of reviews analysed the impact of financial inclusion in LMICs. Along with financial inclusion, social protection is a widely recognised and funded area of international development. Although both reviews are complementary, they constitute independent reviews. Overlaps between both systematic reviews of reviews are presented in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies.

4.3.3. Selection of studies

A review author (OIO) developed the search terminology. The screening process and checklist were pilot tested at title, abstract and full text with the reviews identified through the scoping exercise. At least two review authors (CP, SB, AI, RY, JVDS) independently screened each title, abstract and full text (double‐blind screening). Disagreements were solved by consensus or by consulting another reviewer if consensus could not be reached. Two other review authors (DR, ZNA) revised the list of included reviews to confirm inclusion.

4.3.4. Data extraction and management

A coding tool was developed, and pilot tested for extracting data on the following areas of interest: population, intervention, methodology, quality appraisal, findings for each research question. See the review protocol for details on each data item (Perera et al., 2021). Data from each study was extracted by four reviewers in EPPI‐Reviewer Web (Thomas et al., 2020). To ensure coding consistency, 5% of reviews were coded simultaneously by the entire team and another 10% of reviews were coded independently by two reviewers at the start of the process. Inconsistencies were solved by consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the included systematic reviews was assessed by employing the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses (Aromataris et al., 2015). The JBI checklist includes various considerations for the extent to which a systematic review addresses the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. These considerations include language and publication bias in the search strategy; approaches to minimising systematic errors in the conduct of the systematic review; and whether recommendations are supported by results.

The JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist has 11 criteria:

-

1.

Is the review question clearly and explicitly stated?

-

2.

Were the inclusion criteria appropriate for the review question?

-

3.

Was the search strategy appropriate?

-

4.

Were the sources and resources used to search for studies adequate?

-

5.

Were the criteria for appraising studies appropriate?

-

6.

Was critical appraisal conducted by two or more reviewers independently?

-

7.

Were there methods to minimise errors in data extraction?

-

8.

Were the methods used to combine studies appropriate?

-

9.

Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed?

-

10.

Were recommendations for policy and/or practice supported by the reported data?

-

11.

Were the specific directives for new research appropriate?

Each of the questions posed in the checklist can be scored as being ‘met’, ‘not met’, ‘unclear’ or ‘not applicable’, which allows assessors to make a broad assessment of the quality of included reviews. Supporting Information Appendix 2 presents the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. Reviews were given a score of 1 for each checklist criteria clearly met and 0 for those not met or unclear, with a maximum possible score of 11. Reviews scoring 8‐11 were categorised as high quality, those scoring 4–7 as moderate, and 0–3 as low‐quality systematic reviews. Reviews rated as low‐quality were excluded. To ensure consistency, two reviewers simultaneously appraised the quality of 20% of reviews at the start of the process and disagreements were solved by consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

As suggested by Pollock et al. (2021); we extracted and tabulated the pooled effect sizes of gender equality outcomes of meta‐analyses as reported by the review authors.

Unit of analysis issues

We extracted information at the systematic review level. However, when only a subset of the studies included in a review meet our inclusion criteria, data was extracted from the results that relate to said studies. To ensure that this data refers to the specific studies, extracted data was cross‐checked with the primary study. Lastly, we extracted results from systematic reviews as reported by the review authors.

Assessment of reporting biases

One of the items on the JBI checklist (criteria 9) assesses whether the review authors carry out an investigation of publication bias and discuss the impact this had on their review findings. Any other observations relating to other types of reporting biases (e.g., language, location, citation, outcome reporting biases) were noted and addressed in the discussion section of the review.

Data synthesis

This systematic review of reviews employed framework synthesis as the synthesis method. Framework synthesis is a method used in systematic reviews to examine complexity in which an a priori conceptual framework shapes the understanding and analysis of the research problem (Brunton et al., 2020). There are several reasons why this approach is suitable for this review. First, it can be applied to reviews of complex interventions and where there is a broad thematic scope (Brunton et al., 2020; Snilstveit et al., 2012). This review encompasses an entire domain of interventions (social protection), which itself comprises multiple intervention types and sub‐types. The GRASSP Conceptual Framework (Figure 1) illustrates how complex the linkages and pathways are between interventions and gender outcomes. Secondly, as Flemming et al., 2019 argue, framework synthesis allows for the juxtaposition of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Our review seeks to address not only the impacts of different social protection interventions, but also the differential impacts according to gender and age, the factors that determine those impacts and the circumstances under which the intervention might work. The GRASSP Conceptual Framework serves as a ‘scaffold’ for collating quantitative and qualitative evidence on complex social protection interventions from different types of review. The approach to framework synthesis described by Brunton et al. (2020) consists of three steps, as summarised below.

-

1.

Framework selection and familiarisation

Prior work undertaken within the broader GRASSP programme, in scoping the literature and developing the GRASSP Conceptual Framework constitutes part of this stage. The framework proposes a systematic, holistic, and integrated approach for conceptualising the intersections between gender and social protection. It provides this review with a typology of social protection interventions and gender equality outcome areas, as well as delineating the structural and individual drivers, moderators and design and implementation elements that may determine gender outcomes. It was developed through a review of the literature and refined through consultations with gender and social policy experts. The current framework builds on and expands existing conceptual and theoretical efforts focused on integrating a gender lens into public policy (UNICEF Office of Research—Innocenti, 2020). The scope of this review is determined by the GRASSP Conceptual Framework. This process, along with the previously described scoping exercise, contributed to the review team's familiarisation with the selected framework.

-

2.

Indexing and charting

The GRASSP Conceptual Framework provides a basis for searching for, screening, and extracting data from included reviews. The search strategy translates the key concepts from the typologies of interventions and outcomes. Our approach to the data, themes, and categories to be coded are driven by the way in which the interventions, outcomes, structural and individual drivers, moderators and design and implementation factors are represented in the framework. Data extraction draws directly from the typologies contained within the framework. This provides us with an initial scaffolding for grouping characteristics from each review into categories and deriving themes from this data. Framework synthesis is iterative in nature (Petticrew et al., 2013) and therefore allows for both a deductive and inductive approach to synthesis. This allows to extract and synthesise data from qualitative and quantitative reviews that may have different epistemological underpinnings, which is necessary to answer our research questions. We took a partly deductive approach to answering our research questions. We draw on reviews, including but not limited to systematic reviews of effectiveness. From these studies, we extracted data on programme impacts, and on differential impacts on gender and age sub‐groups. In this way, our synthesis of data from reviews of quantitative studies has much in common with current deductive approaches to the narrative synthesis of quantitative findings. Answering research question 2 entailed extracting data iteratively on factors that may influence the impacts of social protection programmes on gender equality outcomes, as represented in the GRASSP Conceptual Framework. Similarly, for research question 3, we built upon the typology of implementation and design issues considered in the framework. In this iterative synthesis, the results need to be organised so that patterns in findings from design and implementation of interventions can be identified across reviews (Popay et al., 2006).

-

3.

Mapping and interpretation

The main concepts for interventions, outcomes, contextual factors, and implementation and design issues have been identified in the GRASSP Conceptual Framework and were supplemented with additional themes emerging from the included reviews (Snilstveit et al., 2012). The first and third authors (CP and AI) synthesised the extracted data across each research question independently and then revised and merged each other's synthesis to produce a common synthesis of findings by outcome area (i.e., economic security and empowerment, health, education, mental health and psychosocial support, voice and agency and safety and social protection), which was discussed with and revised by the second author (SB). Following this, the two authors (CP and AI) identified and drafted key findings across outcome areas which were then checked and validated by the second author. All key findings were revised in collaborative discussions with all co‐authors based on the synthesis of findings by outcome area. Theories and pathways presented by the authors were also considered and were included in our analysis. When reviews offered discordant results, findings are presented along with a discussion on potential reasons for differing results. Results from meta‐analysis were included based on review authors' interpretation of their findings. However, to offer more information, we tabulated the pooled effect size of meta‐analyses that provided gender disaggregated findings (Supporting Information Appendix 6).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The relationships or subgroup analysis explored as part of step 2 of framework synthesis include exploring different outcomes across gender and age groups (e.g., women and men, adolescent girls and boys, older adults) to investigate differences in outcomes as well as what factors explain any identified patterns.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Description of studies

5.1.1. Results of the search

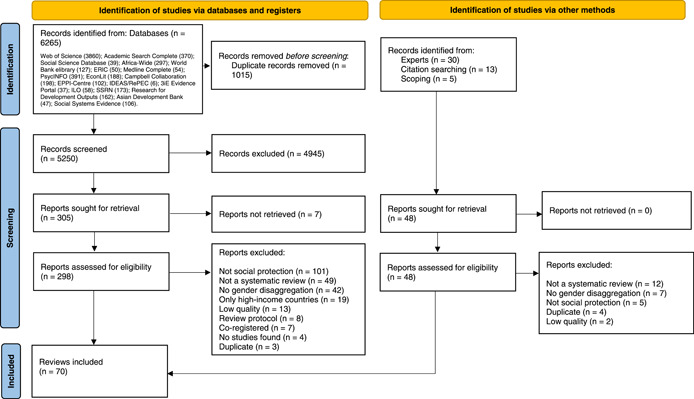

A total of 6265 records were identified through 19 databases, libraries, and institutional websites, of which 1015 were duplicates. After removing duplicates, 5250 records were screened independently and simultaneously by two reviewers (AI, JVDS, RY, CP) based on title and abstract and 298 full texts were subsequently assessed for eligibility. An additional 48 records, identified through the initial scoping exercise, consultations with experts and citation searching, were also screened. After quality appraisal, 15 systematic reviews were classified as low‐quality and excluded from the review.

Upon screening and quality appraisal completion, 70 systematic reviews, representing a total of 3289 studies, met the criteria for inclusion and were taken forward for data extraction and analysis. Figure 2 outlines the process of identifying reviews via databases, expert consultations and citation searching.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram

5.1.2. Included studies

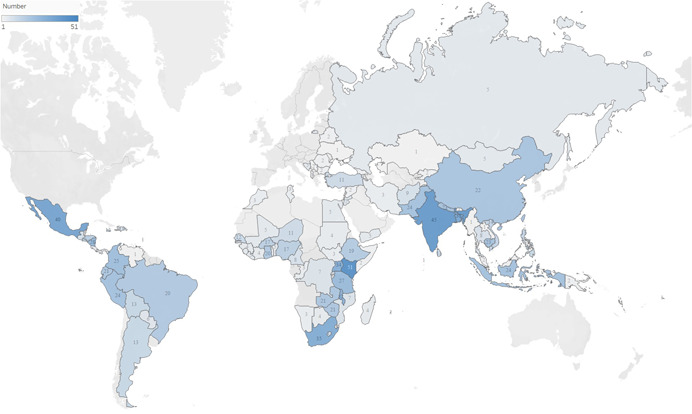

Of the 70 reviews, 9 had global geographical coverage and the remaining 61 focused on LMICs covering a total of 121 countries, with only one review specifically narrowing the scope to contexts of humanitarian emergencies. Of the 70 included systematic reviews, two focused specifically on Sub‐Saharan Africa. Figure 3 presents the geographical spread of primary studies. Kenya (N = 51), India (N = 45), Mexico (N = 40) and Bangladesh (N = 38) are the top four represented countries. Given the large number of primary studies within each systematic review, the country where the study was conducted was extracted once regardless of how many studies within the review were conducted in each country. Supporting Information Appendix 3 presents a summary of included reviews according to authors, number of included studies, type of review and analysis, geographic focus, gender and life course, intervention area and outcome area.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of low and middle‐income countries of primary studies per review. High‐income countries included in systematic reviews' primary studies are not presented in this map

Reviews were published between 2011 and 2021, with most (46%, N = 32) being published between 2015 and 2017. The number of studies included in each review ranged between 3 and 420, with a mean value of studies of 47. However, this is mainly driven up by eight reviews with over 100 included studies each (Bastagli et al., 2016; Clifford et al., 2013; Doocy & Tappis, 2017; Kluve et al., 2017; Oya et al., 2017; Waddington et al., 2014; World Bank, 2014), with one outlier with 420 included studies (Snilstveit et al., 2015). Only one of the included reviews was published in a language other than English (Portuguese; Santos et al., 2019).

Most reviews included qualitative synthesis methodologies (87%, N = 61). Of these, most employed narrative synthesis (44% of the 61 qualitative analysis reviews, N = 27), followed by thematic analysis and descriptive synthesis (both at 10%, N = 6). Systematic reviews conducting meta‐analyses made up 31% (N = 22) of the sample and 24% (N = 17) of reviews employed both quantitative and qualitative methodologies to synthesise their findings. Reviews included primary studies with multiple designs, with most focusing solely on quantitative methodologies.

Most reviews (63%) did not impose any age restrictions, and 16% focused only on children (0–19 years of age). As it was part of the review's inclusion criteria, all reviews provided some sort of gender disaggregated outcomes. Most recipients of programmes were women and men, and 24% targeted women alone. Other specific populations of focus included: low‐income households, mothers, caregivers and children, women of child‐bearing age, women of working age, smallholder farmers, population affected by humanitarian crises.

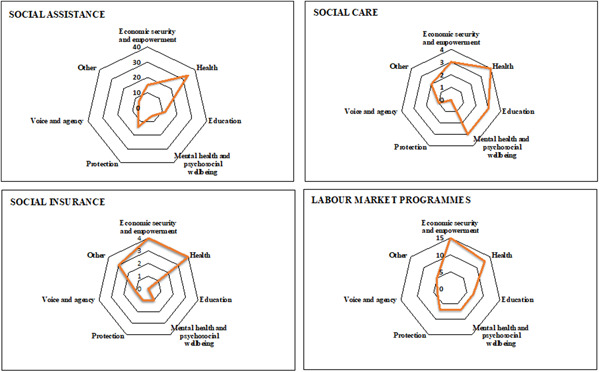

Most reviews (77%, N = 54) investigated social assistance programmes, 40% (N = 28) investigated labour market programmes, 11% (N = 8) focused on social insurance interventions and 9% (N = 6) focused on social care interventions. Most of the reviews included only one intervention type (69%, N = 49), with 24% (N = 17) including two types of intervention, most of which are a combination of social assistance and labour market interventions, 26% (N = 18) of the total number of reviews; 6% (N = 4) including three or four types of intervention, and 13% (N = 9) including also other forms of interventions that are not social protection (e.g., microfinance, health, and education interventions). Most studies (69%, N = 48) included in the reviews assessed impact of the intervention in comparison to control groups (e.g., including non‐beneficiary populations or treatment as usual, beneficiaries with and without disabilities, and before and after comparisons). Just over a third of reviews analysed results of both control and other interventions (36%, N = 25) and 43% (N = 30) only included studies with a comparison condition (e.g., conditional vs. unconditional transfers, different types of transfer modalities and transfer size).

Health (e.g., utilisation of services, knowledge of sexual and reproductive health, anthropometric measures) was the most covered (70%, N = 49) outcome area among the 70 reviews. This is mainly driven by social assistance programmes (Figure 4). Economic security and empowerment (e.g., employment, savings, expenditure; 39%, N = 27) was the second most researched outcome area followed by education (e.g., school enrolment and attendance, test scores; 24%, N = 17). Most reviews covered a single outcome area (59%, N = 41) with less than half that number covering two types of outcomes areas. Economic security and empowerment and health were most frequently investigated together (e.g., nutritional outcomes and household expenditure; 26%, N = 18), followed by either of these with education (e.g., school enrolment and household employment, sexual and reproductive health outcomes, and school attendance; 17%, N = 12). Interventions were mostly provided by government agencies (73%, N = 51), followed by partnerships with NGOs (51%, N = 36) and private institutions (e.g., private health facilities) were involved in 26% (N = 18) of reviews. Figure 4 presents the distribution of interventions by outcome type. A list of the specific interventions and indicators considered within each review is available upon request.

Figure 4.

Outcome areas by intervention type

5.1.3. Excluded studies

During title and abstract screening, most records (63%) were excluded for not meeting the criteria of systematic review, 28% were excluded based on not reviewing social protection interventions and the remaining 9% were excluded for other reasons (e.g., focus on high‐income countries alone). At full‐text screening, most records (35%) retrieved through academic databases and institutional websites were excluded for not addressing at least one type of social protection intervention, 16% were not systematic reviews, 14% did not provide gender disaggregated results and the remaining 35% were excluded for other reasons (e.g., focus on high‐income countries alone, low‐quality, protocol of review).

5.2. Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of included reviews was assessed using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. As explained in the review protocol (Perera et al., 2021), low‐quality reviews were excluded from this systematic review. Although these reviews may offer contributions to the study of the impact of social protection programmes on gender equality, their quality hinders the validity of their findings and conclusions and including them could have affected the overall validity of this systematic review of reviews.

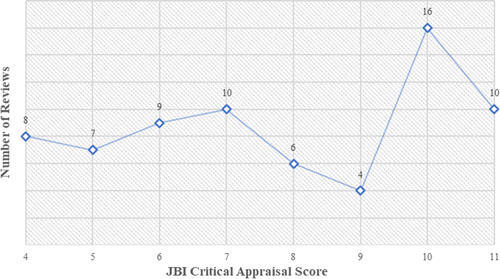

Low‐quality reviews were excluded based on unclear or no reporting of methodological aspects such as synthesis process, appraisal of primary studies and sources and resources used to conduct the search. Upon appraisal completion, 51.4% (N = 36) of reviews were rated as high quality (JBI score = 8–11) and 48.6% were rated as moderate quality (JBI score = 4–7). Ten reviews received the highest quality score (Baird et al., 2013; Brody et al., 2015; Chinen et al., 2017; Doocy & Tappis, 2017; Kristjansson et al., 2015; Langer et al., 2018; Pega et al., 2015; Pega et al., 2017; Tripney et al., 2013; Waddington et al., 2014) and eight reviews received the lowest moderate quality score (Bassani et al., 2013; Buller et al., 2018; Dammert et al., 2018; Glassman et al., 2013; Halim et al., 2015; Kabeer et al., 2012; Kennedy et al., 2020; Skeen et al., 2017). Figure 5 presents the number of reviews by quality score. Supporting Information Appendix 5 presents a list of included high and moderate quality reviews and a list of reviews excluded due to low quality, as well as a graph of the number of reviews that scored positively across each JBI item.

Figure 5.

Number of reviews by JBI critical appraisal score (high‐moderate). JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute

5.2.1. Independence of review—Overlap

Given that all included reviews were published in the same decade (2011–2021), it is likely that reviews overlap on different aspects of their inclusion criteria and therefore draw on the same pool of studies. We created citation matrixes to visually demonstrate the degree of overlap in percentage across every two included systematic reviews in the four intervention areas, to address the potential risk of bias that inclusion of systematic reviews that address similar research questions or related interventions, which may include some of the same underlying primary studies multiple times. The overall CCA across the 70 included reviews was 0.54% which according to Pieper et al., 4'sterpretation represents a slight overlap.

Across the 54 reviews investigating social assistance programmes, we find an overall slight overlap of 1.02%. Although the overlap is low, this category of interventions demonstrates the highest overlap of all four types of social protection interventions. In addition, within this category, there are four groups of systematic reviews that have very high CCA scores exceeding 15%. We find that the highest correlations occur between three reviews investigating male circumcision (Choko et al., 2018; Ensor et al., 2019; Kennedy et al., 2014). Three reviews on maternity care services also showed high overlapping scores (Hunter & Murray, 2017; Hunter et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2014). Four reviews on the topics of child marriage, unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted illnesses among young people demonstrate high overlapping scores (Hindin et al., 2016; Kalamar, Bayer, et al., 2016; Kalamar, Lee‐Rife, et al., 2016; Malhotra et al., 2021). In addition, 10 additional sets of systematic reviews of which the CCA score exceeds 10%, considered as a high level of overlap. Supporting Information Appendix 4 presents matrices of systematic review with overlap.

Across the 24 reviews investigating labour market programmes, we find an overall slight overlap of 0.46%. In addition, there is one group of systematic reviews that have CCA scores exceeding 15%, including the notable overlap between reviews also presented above on the topics of child marriage and unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted illnesses among young people (Hindin et al., 2016; Kalamar, Bayer, et al., 2016; Kalamar, Lee‐Rife, et al., 2016; Malhotra et al., 2021). Besides, the correlation scores between reviews investigating the impact of labour market programmes on women also show a high overlap, as presented in the appendices (Chinen et al., 2017; Ibanez et al., 2017; Langer et al., 2018; Yoong, Rabinovich and Diepeveen 2012).

Within the social insurance interventions or programmes, which includes eight systematic reviews, only one correlation was identified between two reviews on community‐based health insurance (Adebayo et al., 2015; Dror et al., 2016), with a very high CCA score of 16.18%. Similarly, within the social care intervention area, which includes nine systematic reviews, there was only one correlation between Ibanez et al., 2017; and Langer et al., 2018 with a slightly low CCA score of 3.77%.

Lastly, two systematic reviews (Brody et al., 2015; Kennedy et al., 2014) were included in another systematic review of reviews focusing on financial inclusion interventions (Duvendack & Mader, 2019) since they both simultaneously researched social protection and micro‐finance interventions.

5.3. Effects of interventions

This section presents the results of the synthesis of 70 moderate to high quality systematic reviews on the impact of social protection interventions on gender equality. First, we report five key findings that were consistent across different intervention and outcome areas (‘Findings across Outcome Areas’). Next, we outline the findings on intervention effectiveness by outcome area (i.e., economic security and empowerment, health, education, mental health and psychosocial wellbeing, voice and agency and safety and protection) (‘Findings by Outcome Area’). Supporting Information Appendix 7 summarises effectiveness findings across each intervention category and Supporting Information Appendix 6 provides a summary table of pooled effect sizes of gender equality outcomes of meta‐analyses as reported by the authors of included systematic reviews.

Within each sub‐section, we report on the contextual and structural factors as well the design and implementation features that were identified as determinants of intervention effectiveness. Although separated for ease of reference, effectiveness, contextual and structural factors and design and implementation features are intertwined. In several reviews, gender differentiated effects were partially attributed to design and implementation features and were regularly influenced by contextual and structural factors. Similarly, the influence of contextual or structural factors can be addressed via appropriate design and implementation features. The findings below stem from the framework synthesis and are stated without interpretation.

5.3.1. Findings across outcome areas

Key finding: Social protection programmes tend to report higher impacts on women and girls in comparison to men and boys

Most reviews report higher effectiveness of social protection programmes (e.g., increased saving and investment, utilisation of health care services, school attendance) on women and girls than on men and boys. This is possibly explained by women reporting lower scores at baseline (e.g., women are more likely to be unemployed, out of school, possess lower decision‐making power within household and lower social support in the community), which most primary studies do not seem to control for. The largest effects of interventions are identified in settings with the poorest indicators and among the most vulnerable populations (e.g., lowest income areas and countries, lowest levels of education, women with heavier household workloads, women living in rural areas, child labourers) (Clifford et al., 2013; Dammert et al., 2018; Dickson & Bangpan, 2012; Kluve et al., 2017; Kristjansson et al., 2015; Manley & Slavchevska 2012; Maynard et al., 2017; Oya et al., 2017; Ton et al., 2013; Tripney et al., 2013; Waddington et al., 2014; World Bank, 2014). At the same time, these vulnerabilities (e.g., limited access to information or education, women with disabilities, older people living alone, poverty, discrimination, persons affected by humanitarian emergencies) act as barriers to uptake of social protection programmes (Brody et al., 2015; Dickson & Bangpan, 2012; Maynard et al., 2017; Oya et al., 2017).

Key finding: Women are more likely to save, invest and share the benefits of social protection but lack of family support is a key barrier

Across reviews, there are indications of structural altruistic behaviour among women participating in social protection programmes whereby women seem more likely to save and invest to off‐set future shocks (Bastagli et al., 2016; Durao et al., 2020; Hidrobo et al., 2018; Kabeer et al., 2012; Owusu‐Addo et al., 2018; Tirivayi et al., 2016; World Bank, 2014; Yoong et al., 2012). Some reviews indicate that women are also more likely to allocate transfers and income on the needs of children or other members of the household (Durao et al., 2020; Kabeer et al., 2012; Tirivayi et al., 2016; Yoong et al., 2012).

At the same time, women's uptake of social protection programmes is often contingent on the support women receive from family members (Bastagli et al., 2016; Buller et al., 2018; Chinen et al., 2017; Clifford et al., 2013; Dickson & Bangpan, 2012; Gibbs et al., 2017; Hunter & Murray, 2017; Kluve et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2018; Murray et al., 2014; Owusu‐Addo et al., 2018; Oya et al., 2017; Waddington et al., 2014; Zuurmond et al., 2012). The uptake of health care services vouchers is determined by social and cultural attitudes (e.g., expectations to return to family home after birth, childcare expectations, partners not wanting to be labelled as poor) (Gibbs et al., 2017; Hunter & Murray, 2017; Zuurmond et al., 2012). Family pressures and responsibilities also act as a barrier to uptake in labour market programmes (Chinen et al., 2017; Clifford et al., 2013; Kluve et al., 2017; Oya et al., 2017), cash transfers (Owusu‐Addo et al., 2018) and earlier discharge from hospital among women participating in social assistance programmes for maternity services (e.g., short‐term payments to offset costs and vouchers for maternity services) (Murray et al., 2014). Indeed, a review on certification schemes for agricultural production identified higher participation of women in trainings, in matrilocal setting and settings with high rates of migration among men (Oya et al., 2017).

Domestic and childcare responsibilities are key barriers to women's participation in vocational and business training programmes and the access to income associated with participation in such trainings (Chinen et al., 2017). Transfers to women are in some contexts more acceptable within families and communities if they aim to support an activity considered within the responsibilities of women, such as child nutrition (Buller et al., 2018). Our synthesis shows that transfers that do not create excessive disruptions to household gender norms may be more acceptable. In turn, transfers that disrupt gender norms are more detrimental in highly patriarchal societies (Bastagli et al., 2016; Buller et al., 2018). This is also the case for labour market programmes implemented in contexts where women are not expected to work outside the home (Chinen et al., 2017; Gibbs et al., 2017; Oya et al., 2017). Other key barriers to uptake include gender norms relating to freedom of movement, disapproval regarding their choices, disbelief in their abilities, and limited decision‐making capacity within the household (Chinen et al., 2017; Gibbs et al., 2017; Oya et al., 2017). These key barriers, however, are context‐specific and more prevalent in patriarchal or religious countries with discriminatory formal or informal laws.

Key finding: Adverse and unintended outcomes are attributed to design and implementation features

No reviews report negative impacts of social protection programmes on women or men. However, there are indications of adverse and unintended outcomes attributed to design and implementation features. Targeting girls through financial incentives for education may have an unintended negative impact on boys' schooling (i.e., decreases in enrolment) (Dickson & Bangpan, 2012), old‐age pensions for persons living alone may drive older adults away from families to comply with requirements (Devereux et al., 2015), the participation of mothers in labour market programmes may lead to decreases in school attendance among their adolescent daughters who make take up more of the care and domestic work in the household (Dammert et al., 2018) and girls' mental health can be negatively impacted when conditional cash transfers become the key or main source of income (Dickson & Bangpan, 2012). Several reviews (Chinen et al., 2017; Hunter & Harrison, Portela, et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2016; Langer et al., 2018; Maynard et al., 2017; Mwaikambo et al., 2011) emphasise the importance of identifying and addressing women's local barriers to access, uptake and retention of social protection such as programme‐induced expenses (e.g., child‐care, transport, medicine and material costs). Such features, however, are not generalisable and vary largely across intervention types and settings. This, combined with the lack of evidence on design and implementation, make drawing inferences on features (e.g., eligibility criteria, gender of recipient) inappropriate. The impact of social protection programmes is largely dependent on the overarching social, cultural, political, and economic context, making it critical for programmes design and implementation to be tailored to each setting and targeted group.

Key finding: Social protection programmes with explicit objectives tend to demonstrate higher effects in comparison to social protection programmes without broad objectives

Reviews indicate that social protection programmes with explicit objectives tend to demonstrate higher effects on targeted outcomes (e.g., child marriage or gender norms) or closely related structural factors (e.g., child marriage via school attendance) in comparison to social protection programmes with broad objectives (e.g., reproductive health, empowerment; Chinen et al., 2017; Kalamar et al., 2016b; Malhotra et al., 2021). This has been attributed to the important role of awareness, ‘framing’ of the issue, promotional, outreach and communication strategies (e.g., providing information on eligibility criteria, available facilities, resources and services) in the implementation of social protection programmes (Hunter & Harrison, Portela, et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2014). Indeed, various reviews (Brody et al., 2015; Buller et al., 2018; Chinen et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2018; Langer et al., 2018) identify, qualitatively and quantitatively, the added value of providing social protection interventions in combination with some form of training (e.g., life‐skills, soft‐skills, financial trainings or gender training) relating to the objectives of the benefit. This finding may be connected to conditionalities, which appear to be a determinant of programme effectiveness across two outcome areas (i.e., education and safety and protection).

Key finding: Strengthening social protection systems contributes to acceptability, uptake, retention, and sustainability of interventions

Lastly, various reviews (Baird et al., 2013; Blacklock et al., 2016; Glassman et al., 2013; Hunter & Murray, 2017; Hurst et al., 2015; Lee‐Rife et al., 2012; Malhotra et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2014; World Bank, 2014) identify the importance of strengthening health, protection and education systems (supply‐side) to respond to the demand created by social protection programmes. This is hypothesised to increase the acceptability of services, which in turn contribute to uptake, retention, and sustainability of social protection programmes.

5.3.2. Findings by outcome area

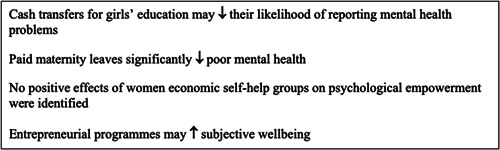

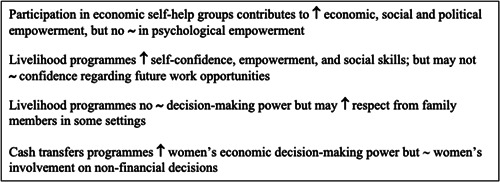

Economic security and empowerment

Various social assistance and labour market programmes are associated with higher labour participation among women in comparison to men. Higher, although small, effects in overall employment, formal employment, hours in paid employment and earnings were found among women participating in vocational and business trainings in comparison to control groups. Interventions that provide job skills training with job placement services are an effective approach to increase women's wage labour participation in higher‐growth sectors in LMICs (Langer et al., 2018). Various reviews (Brody et al., 2015; Chinen et al., 2017; Langer et al., 2018) identify higher returns of social assistance and labour market programmes for women in comparison to control groups when provided in combination with some form of training (e.g., life‐skills, soft‐skills or financial trainings). However, programmes aiming to address various economic objectives by integrating multiple social protection programmes may require longer exposure to achieve significant results (Haberland et al., 2018). In addition, despite these positive findings on social assistance and labour market programmes, improvements across various economic outcomes (e.g., formal employment, earnings, self‐employment) may decrease over time (e.g., 6‐month follow‐up), especially when programmes are discontinued (Chinen et al., 2017; Haberland et al., 2018).

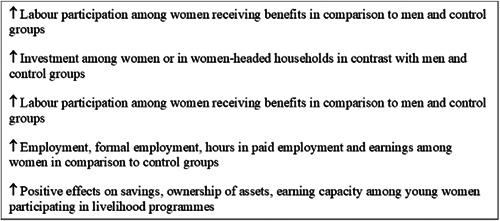

Several systematic reviews point to an association between social assistance programmes, particularly conditional or unconditional cash transfers, and significantly higher investment (e.g., savings, investment in livestock and agricultural tools) among women or in women‐headed households in contrast with men and control groups (Bastagli et al., 2016; Hidrobo et al., 2018; Owusu‐Addo et al., 2018; World Bank, 2014). Of note, while existing reviews use the terms male or female‐headed households, in this review we use the terms households headed by women or men when discussing household headship. Similar associations (i.e., positive effects on savings, ownership of assets, earning capacity) were identified among young women (10‐24 years old) participating in livelihood programmes (i.e., livelihood programmes often combine an economic transfer with a skill or knowledge component; Dickson & Bangpan, 2012). A review conducted by the World Bank, 2014 argues that this finding is consistent with evidence on altruistic behaviour identified among women, whereby they are more likely to pool resources from social assistance to offset future shocks. Figure 6 summarises key findings on the effectiveness of social protection programmes on economic security and empowerment outcomes.

Figure 6.