Take Home Message

Radical perineal prostatectomy with the Xi system is a challenging but reproducible minimally invasive approach for selected patients. No patient reported biochemical recurrence at 12 mo. However, the choice of the surgical approach for radical prostatectomy is likely to be based on the patient’s characteristics, as well as the surgeon’s preferences.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Robotic, Perineal, Radical prostatectomy, Continence, Early continence recovery

Abstract

Background

Radical prostatectomy (RP) represents the standard of care for the treatment of patients with organ-confined prostatic cancer. Historically, perineal RP has been described as the first surgical approach for the complete removal of the prostatic gland. In the past years, robotic techniques provided some technical advantages that allow resuming alternative approaches, such as robotic radical perineal prostatectomy (r-RPP).

Objective

To present in detail the technique of Xi nerve-sparing r-RPP and to report perioperative, oncological, and functional outcomes from a European tertiary center.

Design, setting, and participants

Patients with low- or intermediate-risk prostatic cancer not suitable for active surveillance and prostate volume up to 60 ml who underwent r-RPP between November 2018 and December 2020 were identified.

Surgical procedure

All patients underwent Xi nerve-sparing r-RPP.

Measurements

Baseline characteristics and intraoperative, pathological, and postoperative data were collected and analyzed. The complications were reported according to the standardized methodology to report complications proposed by European Association of Urology guidelines.

Results and limitations

Overall, our series included 26 patients who underwent r-RPP. Patients’ median age was 62.5 yr. Thirteen (50%) and eight (30.7%) patients showed a body mass index (BMI) of 25–30 and >30, respectively. A history of past surgical procedures was present in seven (26.8%) patients. The median prostate volume was 40 (interquartile range [IQR]: 28–52) ml. The median operative time and blood lost were 246 (IQR: 230–268) min and 275 (IQR: 200–400) ml, respectively. Overall, four (15.4%) patients reported intraoperative complications and five (19.2%) reported postoperative complications, with one (3.8%) reporting major complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥3). No patient with biochemical recurrence (BCR) was reported at 1 yr of follow-up. Continence rates were 73.0%, 84.6%, and 92.3%, respectively, at 3, 6, and 12 mo after surgery. Erectile potency recovery rates were 57.1%, 66.6%, and 80.9% at 3, 6, and 12 mo of follow-up, respectively.

Conclusions

Xi r-RPP is a challenging but safe minimally invasive approach for selected patients. No patient reported BCR at 12 mo. The choice of the surgical approach for RP is likely to be based on the patient’s characteristics as well as the surgeon’s preferences.

Patient summary

Our study suggests that Xi radical perineal prostatectomy is a safe minimally invasive approach for patients with low- or intermediate-risk prostatic cancer, and complex abdominal surgical history or comorbidities.

1. Introduction

Radical prostatectomy (RP) represents the standard of care for the treatment of patients with organ-confined prostatic cancer (PCa) [1]. Historically, perineal RP has been described as the first surgical approach for the complete removal of the prostatic gland [2]. Nevertheless, retropubic RP by Walsh is considered the most common surgical treatment for localized PCa to date [3]. This surgical approach overcame intrinsic technical limitations of the perineal RP, offering more familiar landmarks [3].

In the past years, robot-assisted RP (RARP) has rapidly become the leading procedure in prostate cancer surgery [4]. RARP is frequently performed transperitoneally for the large working space and familiar anatomy [5], [6]. Overall, the robotic platform provided some technical advantages as seven degrees of freedom, tremor filtration, a three-dimensional magnified view, and improved ergonomics that facilitate performing complex surgical steps, allowing to resume alternative approaches such as the perineal RP following the principles described by Young [2], [3], [7], [8].

To date, few centers reported their early experience with robotic radical perineal prostatectomy (r-RPP), especially using the da Vinci Si platform [9], [10]. More recently, the introduction of the da Vinci Xi surgical system further facilitated this surgical approach, making it more reproducible and safe [11]. Furthermore, no study evaluated the safety of r-RPP in agreement with the standardized methodology to report complications proposed by European Association of Urology guidelines [12].

The aim of the present study is to present in detail the technique of Xi nerve-sparing r-RPP and to report perioperative, oncological, and functional outcomes from a European tertiary center.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design and population

The present work represents a retrospective study from a prospectively maintained database (institute review board [IRB] number: 0071337–30/09/2020–AOUCPG23/COMET/P, study number: 6523) Residents and surgeons collected all the data. Patients with low- or intermediate-risk PCa and prostate volume up to 60 ml who underwent r-RPP between November 2018 and December 2020 at our academic center (University of Bari, Bari, Italy) were identified. All the patients underwent preoperative multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients who presented prostate volume >60 ml, high-risk PCa, nodal metastasis risk according to Briganti’s nomogram 2018 [1], [13], and locally advanced disease proven on biopsy or MRI were not suitable for r-RPP and not included in the current analysis.

A single surgeon with experience in open and robotic surgery (>500 robotic cases of “standard” transperitoneal RARP, nephrectomy, and radical cystectomy) performed all r-RPP procedures (P.D.) after a step-by-step training on living models; a surgeon with experience in open and urethral surgery assisted during perineal open access (A.V.). All the procedures were performed with the da Vinci Xi surgical system. Bilateral nerve-sparing surgery was applied in all patients with preoperative erectile potency, provided a nerve-sparing approach was not contraindicated according to current guidelines [1]. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

IRB approval was obtained. Baseline characteristics and intraoperative, pathological, and postoperative data were collected. The dataset included the following variables:

-

1.

Baseline features included age, race, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, comorbidities, symptoms, history of prior surgery, preoperative hemoglobin (Hb), preoperative prostate-specific antigen (PSA), ultrasound prostate volume and characteristics, clinical tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging, prostatic biopsy, preoperative International Prostate Symptom Score, International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), and history of urinary incontinence.

-

2.

Treatment and perioperative outcomes included operative time (OT), estimated blood loss (EBL), length of stay (LOS), discharge Hb, complications (intra- and postoperative complications, graded according to Clavien-Dindo classification), and 30-d readmission. The complications were reported according to guidelines [12].

-

3.

Pathological outcomes included histology, pathological TNM [14], grading, Gleason score, and margin status.

-

4.

Oncological and functional outcomes included biochemical recurrence (BCR) defined as a PSA level of >0.2 ng/ml at two consecutive measurements [1], [15]. Continence was defined as the use of one pad or saver-pad [16]. Postoperative erectile function assessment was performed using the IIEF-5 questionnaire [17]. Potency was defined as an IIEF-5 score of ≥17 with or without the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors [17]. Questionnaires were provided to patients at each visit.

2.2. Surgical technique

Surgical technique is described step by step in the accompanying video (Supplementary material).

2.2.1. Robotic system and instruments

The da Vinci Xi surgical system represents the fourth-generation robot by Intuitive Surgical (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Compared with the Si system, the Xi system offers higher versatility and flexibility. For the r-RPP procedure, the following robotic instruments can be used, also depending on the surgeon’s preference:

-

1.

A 30° endoscope with camera (Intuitive Surgical).

-

2.

Monopolar curved scissor (Intuitive Surgical).

-

3.

Fenestrated Bipolar Forceps (Intuitive Surgical).

-

4.

Medium/large needle driver (Intuitive Surgical).

-

5.

AirSeal access ports (ConMed, Utica, NY, USA).

-

6.

GelPOINT Mini (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, US) single-port device

2.2.2. Patient positioning, anesthesia, and port placement

The patient is placed in a dorsal lithotomy position or with a 10–15° Trendelenburg to facilitate access to the perineum. A cushion is placed under the sacrum to increase the patient’s inclination. Whenever possible, a spinal block with deep sedation is performed.

The perineal incision is performed following a semicircular line between the ischial tuberosities, 2 cm above the anus on the midline (Fig. 1). Dissection is conducted on a plane anterior to the external anal sphincter, as described by Young [2]. The ischiorectal fossae are smoothly opened on both sides. The incision of the central tendon of the perineum allows exposure of the rectourethral muscle, which is gradually divided giving access to the dorsal surface of the prostate.

Fig. 1.

Skin incision.

The GelPOINT Mini is placed into a subcutaneous pocket after dissecting the superficial adipose tissue. The GelPOINT Mini allows the introduction of the robotic instruments through a single perineal incision. Three robotic trocars are placed on the GelPOINT at the vertices of an equilateral triangle, as shown in Figure 2. After the port placement, the Xi system is docked, usually on the patient’s left side.

Fig. 2.

GelPOINT Mini and trocar configuration. Three robotic trocars are placed through its jelly top in a triangular disposition, with the optic trocar being upward (orange arrow) and the AirSeal at the base (yellow arrow).

2.2.3. Initial steps and prostate dissection

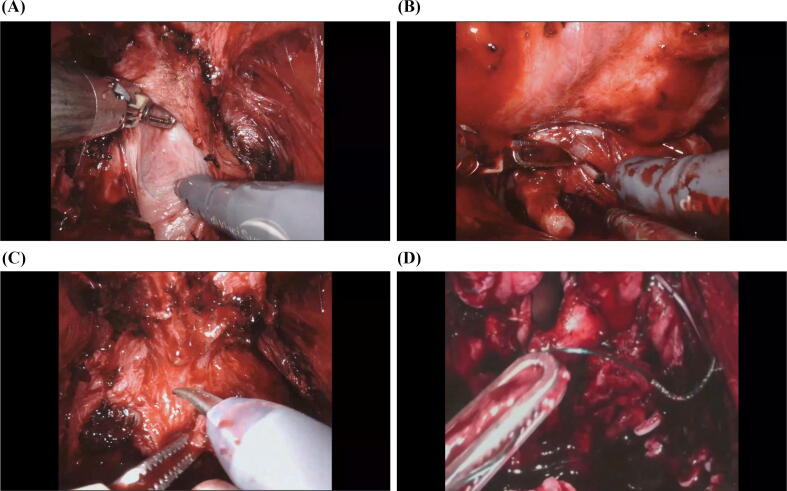

Prostate dissection is performed from the apex to the base, progressing mediolaterally. It reduces the risk of damages to the neurovascular bundles (NVBs; Fig. 3A). The lateral aspects of the prostate are isolated, leaving the endopelvic fascia intact. The dissection can be performed along an inter- or extrafascial plane, according to the Gleason score, clinical staging, prostate disease localization, and preoperative erectile status. In particular, our video shows complete preservation of the right-sided NVB with an intrafascial nerve-sparing approach plane using small Hem-o-lok clips (Weck Closure Systems, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) only. The insufflation pressure was 15 mmHg.

Fig. 3.

(A) The retrograde dissection of the posterior surface of the prostate gland in the nerve-sparing approach. (B) Identification and isolation of seminal vesicle. (C) Dissection of the prostate apex. (D) Vesicourethral anastomosis.

The prostatic pedicles are clipped with Hem-o-lok (Weck Closure Systems) and removed. During the nerve-sparing procedure, electrocauterization of the pedicles should be avoided.

2.2.4. Seminal vesicle and vas deferens isolation

Once the Denonvilliers’ fascia is open, vas deferens is identified, clipped, and removed, as well as the seminal vesicle. Isolation of the dorsal aspect of the prostate is completed (Fig. 3B).

2.2.5. Dissection of the prostate apex and membranous urethra

The membranous urethra is then gently dissected from the external urinary sphincter. Care is taken to completely isolate the apex of the prostate, while keeping the membranous urethra as long as possible (Fig. 3C). In this step, the surgeon needs to carefully mind the localization of NVBs, which run alongside the apex at 5 and 7 o’clock positions, and slightly move towards 3 and 9 o’clock at the junction with the membranous urethra. The urethra is incised with cold scissors, and the catheter is clipped and then cut, keeping the balloon inflated inside the bladder. This is useful for handling during the dissection of the bladder neck (BN).

2.2.6. Anterior dissection and preservation of the BN support

The anterior aspect of the prostate is isolated by lifting the endopelvic fascia and the dorsal venous complex, preserving the Retzius space and its ligamentous structures. The ventral circular fibers of the BN are identified and incised. After catheter removal, incision of the BN is completed on lateral and dorsal margins.

2.2.7. Specimen removal and vesicourethral anastomosis

The robot is undocked, and the specimen can be retrieved by removing the GelPOINT. After robot redocking, anastomosis is carried out with a running suture using V-Loc 90 barbed sutures (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) following van Velthoven et al’s [18] single-knot method (Fig. 3D). The insufflation pressure is reduced to 5 mmHg for the approximation of the BN to the urethra.

2.2.8. Postoperative management and follow-up

Prolonged antibiotics therapy is not required postoperatively, whereas intravenous fluids and pain drugs are used as needed. Daily blood tests are run to evaluate Hb levels and kidney function. The drain is removed on the 1st postoperative day, whereas the catheter can be removed 7–10 d after surgery to allow the closure of the bladder defect. When there are concerns regarding anastomosis healing, a cystography is recommended before catheter removal. Patients were followed according to current guidelines at 1, 3, 6, and 12 mo after surgery [1].

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted according to guidelines [19]. Descriptive statistics was adopted to describe patients’ characteristics and surgical outcomes. The median with interquartile range (IQR) and frequencies were adopted to report continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Kaplan-Meier analyses of recurrence-free and overall survival were performed. All statistical tests were performed with SPSS 25.0 (version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline and staging characteristics

Overall, our series included 26 patients who underwent r-RPP. Baseline characteristics of the study population, and surgical and pathological outcomes are summarized in Table 1, Table 2. Patients’ median age was 62.5 (IQR: 57–66.3) yr. Thirteen (50%) and eight (30.7%) patients showed a BMI of 25–30 and >30, respectively. A history of past surgical procedures was present in seven (26.8%) patients. The median prostate volume was 40 (IQR: 28–52) ml and median PSA was 6 (IQR: 5–7) ng/ml. Of the patients, 75% presented clinical T1c and 57.7% a biopsy International Society of Urological Pathology grade group of 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and staging characteristics of patients undergoing r-RPP

| r-RPP (N = 26) | Results |

|---|---|

| Baseline features | |

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 62.5 (57–66.3) |

| BMI, n (%) | |

| <25 | 5 (19.3) |

| 25–30 | 13 (50) |

| >30 | 8 (30.7) |

| ASA score, n (%) | |

| 1 | 6 (23) |

| 2 | 15 (57.7) |

| 3 | 5 (19.3) |

| CCI, median (IQR) | 4 (3–5) |

| Overall past surgical history, n (%) | 7 (26.8) |

| Abdominal surgery | 4 (15.4) |

| Kidney transplant | 1 (3.8) |

| Hernia repair | 1 (3.8) |

| Other | 1 (3.8) |

| Staging features | |

| PSA (ng/ml), median (IQR) | 6 (5–7) |

| Prostate volume (ml), median (IQR) | 40 (28–52) |

| Clinical T stage, n (%) | |

| T1c | 21 (75.0) |

| T2 | 5 (25.0) |

| Biopsy GS, n (%) | |

| 6 (3 + 3) | 15 (57.7) |

| 7 (3 + 4) | 11 (42.3) |

| Biopsy ISUP grade group, n (%) | |

| 1 | 15 (57.7) |

| 2 | 11 (42.3) |

| Presence of 3rd lobe, n (%) | 2 (7.7) |

| Preoperative IIEF-5, median (IQR) | 18.5 (13.5–22.3) |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI = body mass index; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; GS = Gleason score; IIEF-5 = International Index of Erectile Function-5; IQR = interquartile range; ISUP = International Society of Urological Pathology; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; r-RPP = robotic radical perineal prostatectomy.

Table 2.

Operative, postoperative, and histopathological outcomes of patients undergoing r-RPP

| r-RPP (N = 26) | Results |

|---|---|

| Operative outcomes | |

| Operative time (min), median (IQR) | 246 (230–268) |

| Estimated blood loss (ml), median (IQR) | 275 (200–400) |

| Anesthesia, n (%) | |

| General | 6 (23.0) |

| Spinal | 3 (11.5) |

| Combined | 17 (65.5) |

| Nerve-sparing technique, n (%) | |

| Unilateral | 7 (26.9) |

| Bilateral | 14 (53.8) |

| No | 5 (19.3) |

| Intraoperative opioid use, n (%) | 2 (7.7) |

| Intraoperative complications, n (%) | 4 (15.4) |

| Postoperative outcomes | |

| Overall postoperative complications, n (%) | 5 (19.2) |

| Major postoperative complications | 1 (3.8) |

| Postoperative opioid use, n (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Length of stay (d), median (IQR) | 3 (3–5) |

| Catheter removal time (d), median (IQR) | 9 (8–10) |

| Drain removal (d), median (IQR) | 2 (1–2) |

| Follow-up (mo), median (IQR) | 15 (12–18) |

| Readmission, n (%) | 1 (3.8) |

| Pathological outcomes | |

| Final ISUP grade group, n (%) | |

| 1 | 16 (61.6) |

| 2 | 9 (34.6) |

| 3 | 1 (3.8) |

| Pathological T stage, n (%) | |

| 2 | 21 (80.7) |

| 3a | 5 (19.3) |

| Overall PSM, n (%) | 9 (34.5) |

| Focal | 6 (23.0) |

| Nonfocal | 3 (11.5) |

| Concordance of PSM and site of index lesion at mpMRI, n (%) | |

| Yes | 4 (44.4) |

| No | 3 (33.3) |

| Unknown | 2 (22.3) |

| LVI, N (%) | 1 (3.8) |

IQR = interquartile range; ISUP = International Society of Urological Pathology; LVI = lymphovascular invasion; mpMRI = multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging; PSM = positive surgical margin; r-RPP = robotic radical perineal prostatectomy.

3.2. Surgical and pathology outcomes

The Median OT and EBL were 246 (IQR: 230–268) min and 275 (IQR: 200–400) ml, respectively. Overall, four (15.4%) patients had intraoperative complications and five (19.2%) reported postoperative complications, with one (3.8%) reporting major ones. Details on peri- and postoperative complications are shown in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1. The median drain and catheterization time was 2 and 9 d, respectively. LOS was 3 (IQR: 3–5) d. Nine patients (34.5%) presented positive surgical margins (PSMs; Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3.

Peri- and postoperative complications according to EAU “ad hoc” guidelines [12]

| Descriptive | Grading | Management | Timing, (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative complications | ||||

| Patient #13 | Bleeding | 2 a | Intra- & postoperative transfusions | 2.3 b |

| Patient #15 | GI lesion | 3 a | Intraoperative surgical repair | 2 b |

| Patient #19 | GI lesion | 3 a | Intraoperative surgical repair | 2.2 b |

| Patient #26 | Bleeding | 2 a | Intra- & postoperative transfusions | 1 b |

| Postoperative complications | ||||

| Patient #5 | Bleeding | 2 | Transfusion | 12 c |

| Patient #8 | Wound dehiscence | 2 d | Prolonged catheterization and medications | 24 c |

| Patient #11 | Urine leak | 2 d | Prolonged catheterization | 24 c |

| Patient #13 | Urine leak | 2 d | Prolonged catheterization | 24 c |

| Patient #16 | Bleeding | 3 d | Surgical management | 12 c |

EAU = European Association of Urology; GI = gastrointestinal (rectum).

Grade according to the EAU ad hoc panel guidelines.

Time that occurred between anesthesia initiation and termination.

Time that occurred between anesthesia termination and either 30 or 90 d of follow-up.

Grade according to the Clavien-Dindo Classification and EAU ad hoc panel guidelines.

3.3. Oncology and functional outcomes

Oncological and functional outcomes are reported in Table 4. Overall, no patient with BCR was shown at 1 yr of follow-up. Kaplan-Meier analyses were shown in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2. After catheter removal, postoperative continence rate at 1 mo was 47.6%. Continence rates were 73.0%, 84.6%, and 92.3%, respectively, at 3, 6, and 12 mo after surgery. Erectile potency recovery rates were 57.1%, 66.6%, and 80.9% at 3, 6, and 12 mo of follow-up, respectively.

Table 4.

Oncological and functional outcomes after r-RPP

| Results | |

|---|---|

| PSA, median (IQR) | |

| Postoperative 1 mo | 0.03 (0–0.09) |

| Postoperative 3 mo | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) |

| Postoperative 12 mo | 0.05 (0.04–0.06) |

| BCR at 12 mo, n (%) a | 0 |

| Recovery of erectile function (according to IIEF-5), n (%) b | |

| Postoperative 1 mo | 11 (52.3) |

| Postoperative 3 mo | 12 (57.1) |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 14 (66.6) |

| Postoperative 12 mo | 17 (80.9) |

| Recovery of continence, n (%) c | |

| Postoperative 1 mo | 10 (47.6) |

| Postoperative 3 mo | 19 (73.0) |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 22 (84.6) |

| Postoperative 12 mo | 24 (92.3) |

BCR = biochemical recurrence; IIEF-5 = International Index of Erectile Function-5; IQR = interquartile range; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; r-RPP = robotic radical perineal prostatectomy.

BCR was defined as a PSA level of >0.2 ng/ml at two consecutive measurements [1].

Continence was defined as the use of one pad or saver-pad [13].

Potency was defined as an IIEF-5 score of ≥17 with or without the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors [14]. Only patients who underwent nerve-sparing approach were considered.

4. Discussion

Herein, we provide in detail the surgical technique and present the outcomes of Xi r-RPP with the longest follow-up available to date (Table 5). Our analysis relies on a prospectively maintained dataset that includes a granular description of the study population and its outcomes. Indeed, despite the diffusion of robotic surgery, the literature lacks surgical and postoperative details on Xi r-RPP [3].

Table 5.

Previous series of r-RPP performed in the literature with more than ten patients

| Robotic platform | N | FU (mo) | Prostate volume (ml) | OPT (min) | Nerve sparing (%) | LOS (d) | Catheterization time (d) | PSM (%) | Continence (%) | Major complication (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuğcu et al (2020) [11] | Xi | 95 | 13 | 52 | 140 | 100 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 91 a | 11 |

| Lenfant et al (2021) [23] | Sp | 26 | 12.4 | 30 | 255 | 62.5 | 1 | 11 | 65.4 | 80.1 a | 23 |

| Current | Xi | 26 | 15 | 40 | 246 | 90.7 | 2 | 16 | 34.5 | 92.3 a | 3.8 |

FU = follow-up; LOS = length of stay; OPT = operative time; PSM = positive surgical margins; r-RPP = robotic radical perineal prostatectomy; Sp = single-port platform.

12 mo of follow-up.

Port placement represents a key point in performing a perineal approach with a multiport robotic platform, as also described by Tuğcu et al [11]. The da Vinci Xi system facilitates this approach by maximizing freedom of movement, minimizing instrument clashing, and providing good ergonomics during the critical steps of the procedure, compared with Si [20], [21], [22]. Moreover, we introduced for the first time the AirSeal system as an assistant port. This type of insufflation system responds immediately to the slightest changes in pressure maintaining continuous smoke evacuation and CO2 recirculation, and ensuring visibility during the procedure. One of the challenging steps during r-RPP is the management of the nerve-sparing approach. In our series, in all but five cases (all patients with IIEF-5 <17), the nerve-sparing approach was accomplished. This demonstrates that one of the advantages of using the Xi system is to facilitate this step, allowing adherence to a key oncological principle, as also pointed out in the guidelines [11].

In our cohort, 21 (80.7%) patients reported a BMI of >25, as well as a median Charlson comorbidity index of 4. Overall, nine (34.5%) patients showed a past surgical history. One of the benefits of r-RPP is allowing an optimal surgical option in patients with a previous history of surgical procedure and/or obesity, and cardiac and pulmonary comorbidities, which represent a technical challenge during standard RARP [3]. Moreover, the perineal access minimizes the risks of accidental visceral or major vessel injuries, as well as the no steep Trendelenburg position limits the risk of anesthetic complications [3].

The assessment of surgical outcomes in the present series shows Xi r-RPP to be a safe and effective minimally invasive procedure, providing acceptable OT, acceptable EBL, and a low risk of complications in selected patients. Indeed, we offered r-RPP only to patients with PCa, with prostate volume <60 ml, and without a nodal metastasis risk. In a recent match-paired analysis, the Cleveland Clinic group compared the outcomes of r-RPP performed with a single-port (SP) robotic platform versus Si RARP [23]. The authors reported that SP r-RPP was performed especially in patients with prostate volume <80 cc and who were unfit for the standard surgical approach as well as radiation treatment options. In their study, one and six patients with major complications were reported in the Si RARP and SP r-RPP groups, respectively (p = 0.233) [23]. These findings underline the safety and reproducibility of r-RPP using different new-generation robotic platforms. Notably, at a time when the da Vinci SP platform is not available in Europe, our results showed that Xi r-RPP represents a safe alternative to standard RARP. Moreover, we reported the complications of r-RPP according to European Association of Urology “ad hoc” panel guidelines for the first time, which allow to increase the accuracy of the analysis and avoid missing complication reporting [24], [25], [26], [27].

Regarding perineal lymph node dissection (LND), we selected patients not suitable for LND according to Briganti’s nomogram and staging in the present series. Moreover, this represents a challenging procedure that raised few concerns on the safety and technical feasibility [3]. However, several series reported the safety and feasibility of robotic LND with the perineal approach, and the use of a single-port robotic platform facilitated this surgically challenging procedure [23].

Concerning functional outcomes, 24 (92.3%) and 17 (80.9%) patients showed, respectively, recovery of continence and erectile function at 12 mo of follow-up in our cohort. Recently, Egan et al [28] reported the outcomes of 70 patients who underwent Retzius-sparing RARP compared with those of 70 patients undergoing standard RARP. In their cohort, the Retzius-sparing approach showed a significant improvement of continence rate at 12 mo (97.6% vs 81.4%, p = 0.002) with a faster return to continence (zero to one safety pad, 44 vs 131 d, p < 0.001) compared with the standard approach. To note, our functional results are very similar to those reported by Egan et al [28]. The two surgical approaches allowed a high continence rate due to the preservation of anterior ligaments of the bladder as well as prevention of vesical-urethral anastomosis prolapse with the attempt to maintain as much normal pelvic anatomy as possible [29]. Overall, the robotic platform improved functional outcomes of patients undergoing RP compared with the open and laparoscopic approaches [5], [30].

Regarding oncological outcomes, nine (34.5%) patients reported PSMs in our cohort. In the largest cohort available to date, Tuğcu et al [11] analyzed the outcomes of 95 patients who underwent r-RPP between 2016 and 2018. The authors reported that only eight (8.4%) patients presented PSMs after the surgical procedure [11]. These results are dissimilar to other series looking at an open or minimally invasive approach [3], [23], [31]. However, the difference in the study period, as well as the early phase of the r-RPP learning curve, could have influenced our findings. Furthermore, a low prostate weight was significantly associated with high PSM rates [32]. To note, despite a high PSM rate within our cohort, no patients reported BCR at 12 mo of follow-up after surgery. Intuitively, the short follow-up prevents any conclusion on this aspect, and further studies are needed to better address oncological outcomes of r-RPP and confirm oncological efficacy.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective nature of the study carries intrinsic biases. A selection bias is related to the precise selection criteria of this surgical approach. Second, these outcomes relied on the experience of a high-volume referral center with extensive experience with open and robotic surgery, and therefore the outcomes might be different in other clinical settings [33]. Last, the length of follow-up, as well as the small study cohort, was limited to assess middle- and longer-term oncological and functional outcomes. Further studies with multicenter design and longer follow-up are needed to better address our findings.

5. Conclusions

The current study provides evidence that Xi r-RPP is a challenging but safe minimally invasive approach, particularly for patients with low- and intermediate-risk PCa and prostate volume up to 60 ml. Notably, r-RPP could represent a valid alternative in patients with a previous history of abdominal surgery, and with cardiac or pulmonary comorbidities, or in whom the transperitoneal approach is not indicated.

Author contributions: Umberto Carbonara had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Carbonara, Minafra, Ditonno.

Acquisition of data: Carbonara, Minafra, Papapicco.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Carbonara, Minafra.

Drafting of the manuscript: Carbonara, Minafra.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: De Rienzo, Pagliarulo, Lucarelli, Vitarelli.

Statistical analysis: Carbonara.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Carbonara, Ditonno.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Umberto Carbonara certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Ethics statement: IRB number: 0071337—30/09/2020—AOUCPG23/COMET/P—University of Bari, Bari, Italy. Study number: 6523. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Associate Editor: Guillaume Ploussard

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2022.04.014.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Mottet N, Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, et al. EAU guidelines: prostate cancer.

- 2.Young H.H. The early diagnosis and radical cure of carcinoma of the prostate. CA Cancer J Clin. 1977;27:308–314. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.27.5.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minafra P., Carbonara U., Vitarelli A., Lucarelli G., Battaglia M., Ditonno P. Robotic radical perineal prostatectomy: tradition and evolution in the robotic era. Curr Opin Urol. 2021;31:11–17. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porpiglia F., Fiori C., Bertolo R., et al. Five-year outcomes for a prospective randomised controlled trial comparing laparoscopic and robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basiri A., de la Rosette J.J., Tabatabaei S., Woo H.H., Laguna M.P., Shemshaki H. Comparison of retropubic, laparoscopic and robotic radical prostatectomy: who is the winner? World J Urol. 2018;36:609–621. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbonara U., Srinath M., Crocerossa F., et al. Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy versus standard laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: an evidence-based analysis of comparative outcomes. World J Urol. 2021;39:3721–3732. doi: 10.1007/s00345-021-03687-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martini A., Falagario U.G., Villers A., et al. Contemporary techniques of prostate dissection for robot-assisted prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2020;78:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Traboulsi S.L., Nguyen D.D., Zakaria A.S., et al. Functional and perioperative outcomes in elderly men after robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2020;38:2791–2798. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang Y., Xu W., Lu X., et al. Robotic perineal radical prostatectomy: initial experience with the da Vinci Si robotic system. Urol Int. 2020;104:710–715. doi: 10.1159/000505557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaouk J.H., Akca O., Zargar H., et al. Descriptive technique and initial results for robotic radical perineal prostatectomy. Urology. 2016;94:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuğcu V., Ekşi M., Sahin S., et al. Robot-assisted radical perineal prostatectomy: a review of 95 cases. BJU Int. 2020;125:573–578. doi: 10.1111/bju.15018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitropoulos D., Artibani W., Graefen M., et al. Reporting and grading of complications after urologic surgical procedures: an ad hoc EAU guidelines panel assessment and recommendations. Eur Urol. 2012;61:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandaglia G., Ploussard G., Valerio M., et al. A novel nomogram to identify candidates for extended pelvic lymph node. Eur Urol. 2019;75:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edge S.B., Compton C.C. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crocerossa F., Marchioni M., Novara G., et al. Detection rate of prostate-specific membrane antigen tracers for positron emission tomography/computed tomography in prostate cancer biochemical recurrence: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Urol. 2021;205:356–369. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stolzenburg J.-U., Holze S., Neuhaus P., et al. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic surgery: outcomes from the first multicentre, randomised, patient-blinded controlled trial in radical prostatectomy (LAP-01) Eur Urol. 2021;79:750–759. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jo J.K., Jeong S.J., Oh J.J., et al. Effect of starting penile rehabilitation with sildenafil immediately after robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy on erectile function recovery: a prospective randomized trial. J Urol. 2018;199:1600–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Velthoven R., Ahlering T.E., Skarecky D.W., Huynh L., Clayman R.V. Technique for laparoscopic running urethrovesical anastomosis: the single knot method. Urology. 2020;145:331–332. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Assel M., Sjoberg D., Elders A., et al. Guidelines for reporting of statistics for clinical research in urology. J Urol. 2019;201:595–604. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francavilla S., Veccia A., Dobbs R.W., et al. Radical prostatectomy technique in the robotic evolution: from da Vinci standard to single port—a single surgeon pathway. J Robot Surg. 2022;16:21–27. doi: 10.1007/s11701-021-01194-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cisu T., Crocerossa F., Carbonara U., Porpiglia F., Autorino R. New robotic surgical systems in urology: an update. Curr Opin Urol. 2021;31:37–42. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veccia A., Carbonara U., Derweesh I., et al. Single stage Xi® robotic radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma: surgical technique and outcomes. Minerva Urol Nephrol. 2022;74:233–241. doi: 10.23736/S2724-6051.21.04247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenfant L., Garisto J., Sawczyn G., et al. Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy using single-port perineal approach: technique and single-surgeon matched-paired comparative outcomes. Eur Urol. 2021;79:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gandaglia G., Bravi C.A., Dell’Oglio P., et al. The impact of implementation of the European Association of Urology Guidelines Panel recommendations on reporting and grading complications on perioperative outcomes after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2018;74:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazzone E., Dell’Oglio P., Rosiello G., et al. Technical refinements in superextended robot-assisted radical prostatectomy for locally advanced prostate cancer patients at multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Urol. 2021;80:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazzone E., D’Hondt F., Beato S., et al. Robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal urinary diversion decreases postoperative complications only in highly comorbid patients: findings that rely on a standardized methodology recommended by the European Association of Urology guidelines. World J Urol. 2021;39:803–812. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dell’Oglio P., Palagonia E., Wisz P., et al. Robot-assisted Boari flap and psoas hitch ureteric reimplantation: technique insight and outcomes of a case series with ≥1 year of follow-up. BJU Int. 2021;128:625–633. doi: 10.1111/bju.15421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egan J., Marhamati S., Carvalho F.L.F., et al. Retzius-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy leads to durable improvement in urinary function and quality of life versus standard robot-assisted radical prostatectomy without compromise on oncologic efficacy: single-surgeon series and step-by-step guide. Eur Urol. 2021;79:839–857. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galfano A., Ascione A., Grimaldi S., Petralia G., Strada E., Bocciardi A.M. A new anatomic approach for robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: a feasibility study for completely intrafascial surgery. Eur Urol. 2010;58:457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Branche B., Crocerossa F., Carbonara U., et al. Management of bladder neck contracture in the age of robotic prostatectomy: an evidence-based guide. Eur Urol Focus. 2022;8:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weldon V.E., Tavel F.R., Neuwirth H., Cohen R. Patterns of positive specimen margins and detectable prostate specific antigen after radical perineal prostatectomy. J Urol. 1995;153:1565–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freedland S.J., Isaacs W.B., Platz E.A., et al. Prostate size and risk of high-grade, advanced prostate cancer and biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy: a search database study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7546–7554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quarto G., Grimaldi G., Castaldo L., et al. Avoiding disruption of timely surgical management of genitourinary cancers during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. BJU Int. 2020;126:425–427. doi: 10.1111/bju.15174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.