Abstract

Macrophages are paracrine signalers that regulate tissular responses to injury through interactions with parenchymal cells. Connexin hemichannels have recently been shown to mediate efflux of ATP by macrophages, with resulting cytosolic calcium responses in adjacent cells. Here we report that lung macrophages with deletion of connexin 43 (MacΔCx43) had decreased ATP efflux into the extracellular space and induced a decreased cytosolic calcium response in co-cultured fibroblasts compared to WT macrophages. Furthermore, MacΔCx43 mice had decreased lung fibrosis after bleomycin-induced injury. Interrogating single cell data for human and mouse, we found that P2rx4 was the most highly expressed ATP receptor and calcium channel in lung fibroblasts and that its expression was increased in the setting of fibrosis. Fibroblast-specific deletion of P2rx4 in mice decreased lung fibrosis and collagen expression in lung fibroblasts in the bleomycin model. Taken together, these studies reveal a Cx43-dependent profibrotic effect of lung macrophages and support development of fibroblast P2rx4 as a therapeutic target for lung fibrosis.

Keywords: P2RX4, lung fibrosis, fibroblast, macrophage, calcium imaging

Introduction

Tissue fibrosis is a universal feature of the response to injury and is associated with high mortality in pulmonary fibrosis, liver cirrhosis, chronic heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. In most cases, the inflammatory response is marked by large numbers of monocyte-derived macrophages, which have been found to be necessary for lung fibrosis (1–3). Our recent work profiled the fibrotic phase of lung injury at the single-cell level, revealing a subset of Cx3cr1+ macrophages that localize to clusters of activated fibroblasts and exert a profibrotic effect (3). With respect to the profibrotic mechanisms of these macrophages, one emerging view is that they activate surrounding fibroblasts by secreting cytokines and growth factors, such as TNFα, TGFβ, and PDGF (2–6). However, the full repertory of signals deriving from macrophages is not known.

Previous in vitro results have shown that extracellular ATP activates purinergic receptors on fibroblasts, leading to calcium influx and collagen expression (7, 8). ATP is a known damage associated molecular pattern that binds to and activates membrane channels for calcium entry in a range of inflammatory contexts (9). Recent reports demonstrate that connexin 43 (Cx43) hemichannels are a conduit for ATP efflux by macrophages, with paracrine effects on calcium transients in bystander cells (10–12). However, this biology has not been explored in reference to macrophage-fibroblast crosstalk.

In this study, we found lung fibroblast calcium is increased by co-culture with lung monocyte-derived macrophages. Furthermore, macrophages were found to secrete ATP in a Cx43-dependent manner after injury, and the fibroblast cytosolic calcium response was decreased in co-culture with Cx43 KO macrophages. In vivo studies indicated that the ATP receptor P2rx4 expressed by fibroblasts was necessary for lung fibrosis, revealing a novel profibrotic interaction of macrophages and fibroblasts in lung injury.

Materials And Methods

Mice

Ai14 (Rosa26-LSL-tdTomato), Cx3cr1-CreERT2 (Cx3cr1tm2.1(cre/ERT2)Jung), Cx43 floxed, Rosa26-LSL-Salsa6f, and Macblue (Csf1r-GAL4/VP16,UAS-ECFP)1Hume/J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Col1a2-CreERT2 mice were obtained from Bin Zhou (13). Pdgfrb-Cre (14) and P2rx4 floxed (15) mice were in the possession of the investigative team. Mice with tamoxifen-inducible alleles were administered 2 mg tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648) dissolved in olive oil (Sigma, 01514) via intraperitoneal injection every other day for Cre induction. All experiments were balanced for gender, and mice were used for experiments between the ages of 6 and 10 weeks. Mice were maintained in specific-pathogen-free conditions in the Animal Barrier Facility of the University of California, San Francisco.

ATP Measurement

To isolate macrophages, we sorted tdTomato+ cells using a Sony SH 800 flow cytometer with freshly isolated lung cell suspensions from tamoxifen-induced Cx3cr1-CreERT2: Rosa26-loxp-STOP-loxP-tdTomato mice following lung dissociation with 2000 U/ml DNase I (Roche, 4716728001), 0.1 mg/ml Dispase II (Sigma, 4942078001) and 0.2% Collagenase (Roche, 10103586001), with gating as previously described (3). Cells were passed through a 70-µm filter prior to FACS (Sony SH800) of DAPI- (live), tdTomato+ cells followed by 24-hour culture. Supernatants were then collected for ATP measurement using a luciferase assay as described in the manufacturer’s protocol (ATP Determination Kit, ThermoFisher Scientific, A22066). Bioluminescence was quantified using a Biotek H1 Plate Reader. The ATPase inhibitor ARL 67156 (Sigma-Aldrich, 67156) was used to reduce extracellular ATP degradation.

Macrophage-Fibroblast Co-Culture

tdTomato+ cells were isolated as above by FACS of freshly isolated cell suspensions from Cx3cr1-CreERT2:Ai14 or Cx3cr1-CreERT2: Ai14: Cx43 fl/fl mice. Primary fibroblasts were freshly isolated from mouse lung cell suspensions from Col1a2-CreERT2: Rosa26-LSL-Salsa6f mice by negative selection of endothelial (CD31), leukocyte (CD45), epithelial (Epcam), vascular endothelial, pericytes & smooth muscle (CD146) and red blood (Ter119) cells by biotin-labeled antibodies and Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 65601) as per Tsukui et al. (16). Sorted macrophages and isolated fibroblasts were co-cultured at 1:1 in µ-slide plates (Ibidi, 81506) for 24 hours. Fluorescence images were captured by confocal microscopy with a Leica CTR 6500 microscope, and images were analyzed using Imaris software.

Lung Slice Preparation and Calcium Imaging by Two-Photon Microscopy

Precision-cut lung slices were obtained from mouse lungs according to the protocol described (17). Mice at day 7 after injury with bleomycin were euthanized, and the trachea was cannulated followed by inflation of the lung with 1 mL of 2% low melting point agarose warmed to 37°C (Lonza, 50111) dissolved in 1X PBS. After inflation, agarose was solidified by applying ice-cold 1X PBS to the chest cavity for 1 min. Subsequently, the lungs were excised from the body along with heart and trachea and immersed in ice-cold, serum-free Leibovitz’s media (Gibco, 21083-027). Left lung lobes were isolated and precision-cut transversely in a bath of ice-cold PBS to generate 400-µm slices using a vibratome (Leica VT1200). Slices were placed in a 24-well plate in Leibovitz’s media until imaging.

During imaging, slices were housed in an HP Ultra Quiet Imaging Chamber (Warner Instruments, JG23W/HP) attached to a PM-1 Chamber platform and Series 20 stage adapter. 1X Hank’s Balanced salt solution (HBSS, Gibco, 14025-076) was bubbled with a carbogen gas mixture (95% O2/5% CO2) in a 39°C water bath and pumped with a mini-variable flow pump at a rate of approximately 1.5 mL/minute through an in-line heater into the imaging chamber, maintaining the temperature of the sample at 35-37°C with a dual-chamber temperature controller. Live calcium imaging was performed by two-photon microscopy using an upright LSM 7 MP INDIMO system (Carl Zeiss Microscopy), customized with four GaAsP detectors and a Z-Deck motorized stage (Prior). Samples were imaged with a W Plan-Apochromat 20X/1.0 N.A. water-immersion objective. To minimize the spectral overlap of CFP and GFP, these fluorophores were sequentially excited at different wavelengths. Specifically, one Chameleon Ultra II laser (Coherent) was tuned to a wavelength of 870nm to excite CFP, while the other Chameleon Ultra II laser was tuned to a wavelength of 970 nm to excite both GFP and tdTomato. Samples were imaged with two ‘tracks’ with rapid line switching of laser emissions by acousto-optic modulators (Carl Zeiss Microscopy). Emission filters were 472/30 (Semrock) for CFP, 525/50 (Chroma) for GFP, and 605/70 (Chroma) for tdTomato. Images were collected with ZEN Black software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy), and image analysis was performed with Imaris software (Bitplane). Mean GFP intensity from the entire duration of the video was plotted for all the individual tdTomato+ cells in the field of view.

Bleomycin Lung Injury and Hydroxyproline Measurement

Animals were euthanized 21 days after injury with bleomycin (Fresenius; 3 U/kg), and lungs were perfused with 1X PBS and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. These samples were then homogenized and incubated with 50% Trichloroacetic acid (Sigma, T6399) on ice for 20 mins followed by an overnight incubation at 110°C in 12N HCl (Fisher, A144). Samples were reconstituted in distilled water with constant shaking for 2h. Aliquots of these samples were allowed to react with 1.4% Chloramine T (Sigma, 85739) and 0.5 M sodium acetate (Sigma, 241245) in 10% 2-propanol (Fisher, A416). The samples were incubated with Ehrlich’s solution (Sigma, 03891) for 15 min at 65°C. Hydroxyproline content was measured by the analyzing absorbance at 550 nm with respect to the standard curve generated from purchased hydroxyproline (Sigma, H5534).

Analysis of Published Mouse and Human Lung scRNAseq Data Sets

Data were downloaded from GSE132771 (16), who performed 10x-based single cell sequencing of lungs from 3 Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis patients and 3 healthy controls as well as mice with and without bleomycin-induced lung injury. For human data analysis, we used the lineage-negative data from GSE132771 and combined the data with SCTransform by Seurat v3 (18). For mouse data, we used the same Seurat object of Col1a1+ cells as Tsukui et al. (16).

qPCR of Primary Mouse Lung Fibroblasts

Primary mouse lung fibroblasts were freshly isolated by negative selection from lung cell suspensions as above. RNA was purified using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, 74106) with on-column DNaseI digestion. iScript reverse transcription super mix (Bio-Rad, 1708841) was used for first-strand synthesis, followed by qPCR using SYBR Green super mix (Applied Biosystems, 4309155). Gene expression was normalized to Gapdh. The following primers were used (5’ to 3’):

Mouse Cx43 Forward: ACAGCGGTTGAGTCAGCTTG

Mouse Cx43 Reverse: GAGAGATGGGGAAGGACTTGT

Mouse Col1a1 Forward: CCTCAGGGTATTGCTGGACAAC

Mouse Col1a1 Reverse: CAGAAGGACCTTGTTTGCCAGG

Mouse Col3a1 Forward: GACCAAAAGGTGATGCTGGACAG

Mouse Col3a1 Reverse: CAAGACCTCGTGCTCCAGTTAG

Mouse P2rx4 Forward: GCTTTCAGGAGATGGCAGTGGA

Mouse P2rx4 Reverse: TGTAGCCAGGAGACACGTTGTG

Mouse Gapdh Forward: AGTATGACTCCACTCACGGCAA

Mouse Gapdh Reverse: TCTCGCTCCTGGAAGATGGT

ATPγS Treatment of Human and Mouse Fibroblasts

Normal adult human lung parenchyma was collected from lobectomy specimens from resections performed for primary lung cancer or from normal lungs not used for transplantation. Lung tissue was considered “normal” if the pulmonary function was normal. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants as part of an approved ongoing research protocol by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research in full accordance with the declaration of Helsinki principles. Lung fibroblasts isolated were cultured by the explant technique (19) and used P1 to P4. Primary mouse lung fibroblasts were freshly isolated by negative selection from lung cell suspensions as above.

In both cases (human and mouse), cells were serum starved for 1 hour and, in some cases, treated with ATPγS (Sigma, A1338). Cells were lysed, and RNA was purified using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen,74106) with on-column DNaseI digestion. iScript reverse transcription super mix (Bio-Rad, 1708841) was used for first-strand synthesis, followed by qPCR using SYBR Green super mix (Applied Biosystems, 4309155). Gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA.

Human COL1A1 Forward: GATTCCCTGGACCTAAAGGTGC

Human COL1A1 Reverse: AGCCTCTCCATCTTTGCCAGCA

Human COL3A1 Forward: TGGTCTGCAAGGAATGCCTGGA

Human COL3A1 Reverse: TCTTTCCCTGGGACACCATCAG

Human 18S rRNA Forward: GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT

Human 18S rRNA Reverse: CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG

Sirius Red With Fast Green

Staining with Sirius red (Electron Microscopy Science, 26357-02) and Fast Green FCF (Fisher Scientific, F99-10) was performed on sections prepared from mouse lungs frozen in OCT. Sections were stained with Sirius Red/Fast Green solution (0.125% Fast Green FCF and 0.1% Sirius Red in saturated Picric Acid) for 60 minutes followed by a 2-minute 0.01 N HCl wash, rinsed in 70% EtOH, and air dried overnight prior to imaging. A brightfield microscope (Zeiss Axio scan. Z1) was used for acquiring images, which were quantified using ImageJ. At least three different regions of interest were used for analysis of each sample.

Western Blot

Fibroblasts isolated from mice were lysed with Pierce RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 89901) and Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1861278). 25 micrograms of protein was subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Bio-rad, 4561034) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 88520). Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in 1X PBST (1X PBS+0.01%Tween 20) for 2h at room temperature. Thereafter, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies: Phospho-p38 MAPK (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9211) and p38 MAPK (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9212). After washing with PBST, membranes were incubated with secondary antibody, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:20000, Anaspec, AS28177). Membranes were developed using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 34080) and scanned using ChemiDoc XRS+ gel imaging system (Bio-rad). Quantification of bands was done using ImageJ as described earlier (20).

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism version 8 was used for statistical analysis and linear regression. For categorical variables, Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test was used to calculate P values. For comparing more than 2 populations, 1-way ANOVA or 2-way ANOVA was used followed by Sidak’s or Kruskal Wallis multiple-comparisons testing. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

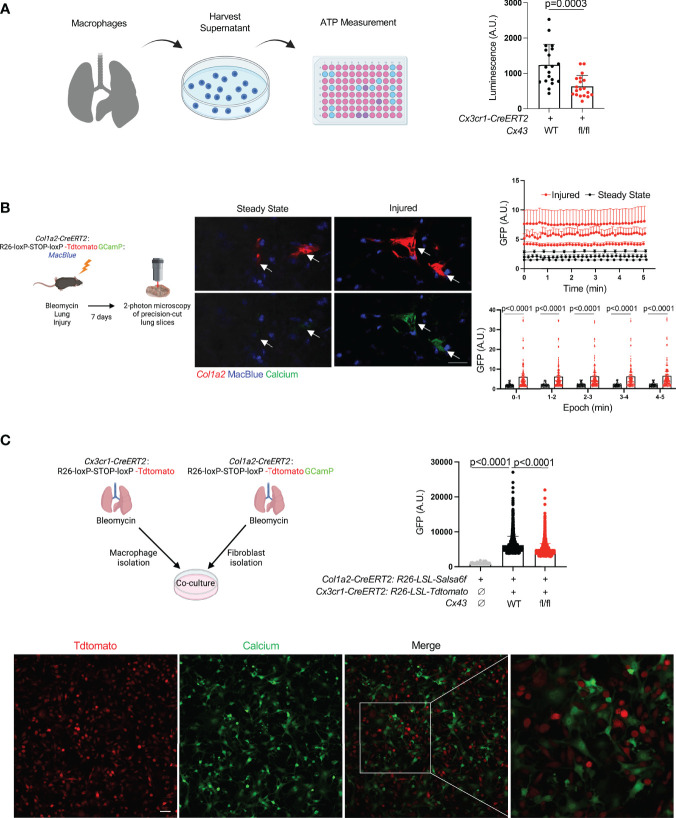

Recent studies have shown that Cx43 hemichannels serve as a conduit for ATP release from macrophages, leading to paracrine effects on other cells in the microenvironment (10–12). To probe the potential significance of macrophage ATP efflux in fibrosis, we employed the bleomycin model of lung fibrosis (21). We first measured ATP in conditioned media of cultured tdTomato+ cells isolated from the lungs of bleomycin-injured Cx3cr1-CreERT2: Rosa26-LSL-tdtomato mice (largely monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages) and found that Cx43 KO macrophages released less ATP into the extracellular space than wild type ( Figure 1A ).

Figure 1.

Lung moMac Cx43 is required for ATP efflux and fibroblast cytosolic calcium in co-culture. (A) ATP measured in conditioned media after 24 hours of culture of tdTomato+ cells sorted from tamoxifen-induced Cx3cr1-CreERT2: LSL-tdTomato mice with or without homozygous floxed Cx43 alleles. Quantitation is for n=3 mice in each group, and points in the graph represent all technical replicates. P value is for Student’s unpaired two-tailed t-test. (B) Representative images of two-photon calcium imaging of precision-cut lung slices taken from Col1a2-CreERT2: R26-LSL-Salsa6f(tdtomato-GCaMP): MacBlue mice at steady state or 7 days after bleomycin injury. Arrows indicate fibroblasts. Scale bar= 50μm. Plots are for time-lapse imaging of individual slices from n=3 mice per condition (10-18 individual cells per field of view for injured and 5-11 individual cells per field of view for steady-state slices). Upper plot shows mean cytosolic GFP fluorescence for individual fibroblasts (as marked by tdTomato) for each slice across time; lower plot presents the same data as mean GFP fluorescence for aggregate data within 5 consecutive 1-minute time periods. P values are for 2-way ANOVA followed Sidak’s multiple comparison test. (C) Confocal calcium imaging of macrophages sorted from tamoxifen-induced Cx3cr1-CreERT2: R26-LSL-tdtomato mice and co-cultured with fibroblasts isolated from tamoxifen-induced Col1a2-CreERT2: R26-LSL-Salsa6f(tdtomato-GCaMP) mice. A representative field of view is shown, and the right-most image magnifies the indicated area in the merge. Scale bar= 50μm. Quantitation is for co-culture with WT or Cx43 KO macrophages, or for fibroblasts alone, for n=3 mice in each condition, and points in the graph represent individual cells. P values are for one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

Extracellular ATP is known to bind to membrane-bound purinergic receptors that mediate extracellular calcium entry into the cytosol. First, to test whether fibroblast cytosolic calcium is elevated in injury, we imaged precision-cut lung slices by two-photon laser scanning microscopy. Slices were prepared from mice with the fibroblast-specific Col1a2-CreERT2 (13) crossed to R26-LSL-Salsa6f (22), which consists of tdTomato fused to the calcium indicator GCaMP; the MacBlue allele (23) was included for visualization of moMacs. These data indicated that fibroblast cytosolic calcium was increased in injured mice compared to uninjured controls ( Figures 1B , Supplementary Videos 1 , 2 ). We then explored the role of macrophage Cx43 by fibroblast calcium imaging in a co-culture system. Co-culture with WT macrophages was associated with higher fibroblast cytosolic calcium than co-culture with Cx43 KO macrophages, or fibroblasts alone ( Figure 1C ). Of note, our previous bulk RNAseq data indicated an increase in Cx43 expression in lung monocyte-derived macrophages compared with tissue-resident alveolar macrophages after bleomycin injury (3). Therefore, to test the functional role of Cx43 in lung fibrosis resulting from injury we used the Cx3cr1-CreERT2, a Cre driver that has been used for functional study of monocyte-derived macrophages in multiple contexts in vivo (3, 24, 25). We measured lung collagen by hydroxyproline assay and found that the increase of lung collagen after bleomycin injury was markedly reduced with Cx43 deletion in moMacs compared to wild type ( Figures 2A, B ). Taken together, these data suggest the hypothesis that macrophages efflux ATP into the extracellular space via Cx43, with a resulting calcium response that is necessary for lung fibrosis after injury.

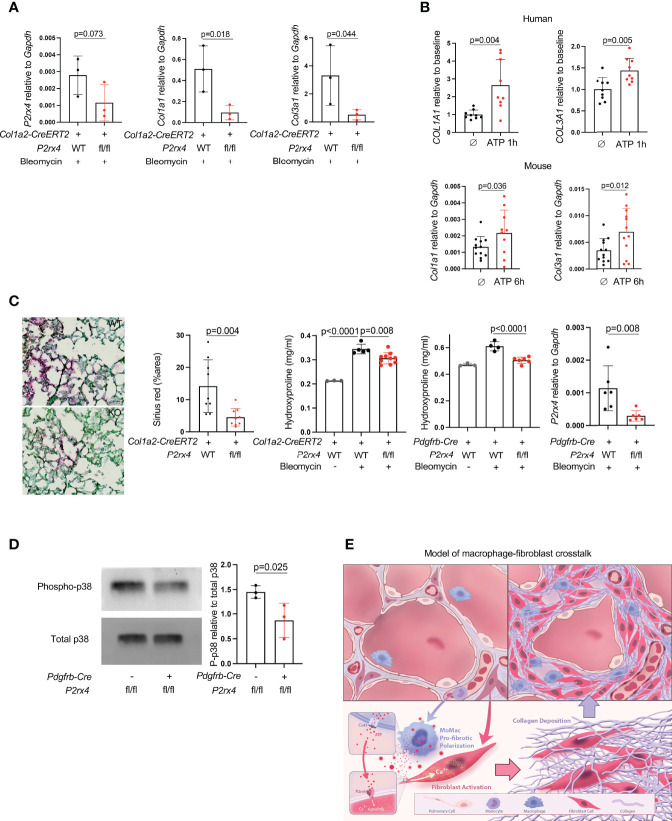

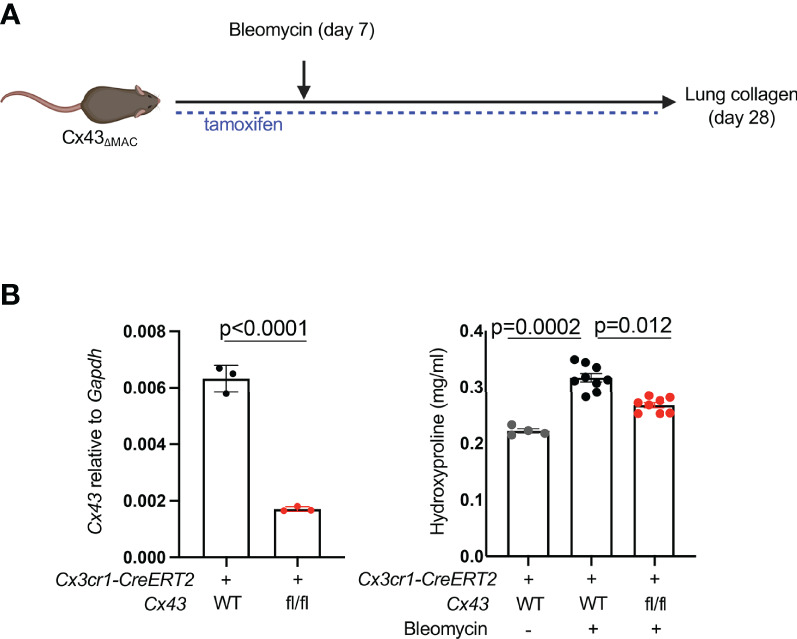

Figure 2.

MoMac Cx43 is required for lung fibrosis. (A) Schematic for testing the effect of macrophage-specific Cx43 deletion on lung collagen after bleomycin injury with Cx3cr1-CreERT2: Cx43 fl/fl mice and controls. (B) qPCR of Cx43 expression in sorted tdTomato+ macrophages from Cx3cr1-CreERT2: R26-LSL-tdtomato: Cx43 fl/fl mice and Cx3cr1-CreERT2: R26-LSL-tdtomato controls. N=3 mice per condition. P value is for unpaired one-tailed t-test (left). Hydroxyproline assay of whole lung collagen from Cx3cr1-CreERT2: Cx43 fl/fl mice and Cx3cr1-CreERT2 controls. N=4, 9, and 8 mice as shown. P value is for one-way ANOVA followed by Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparison test (right).

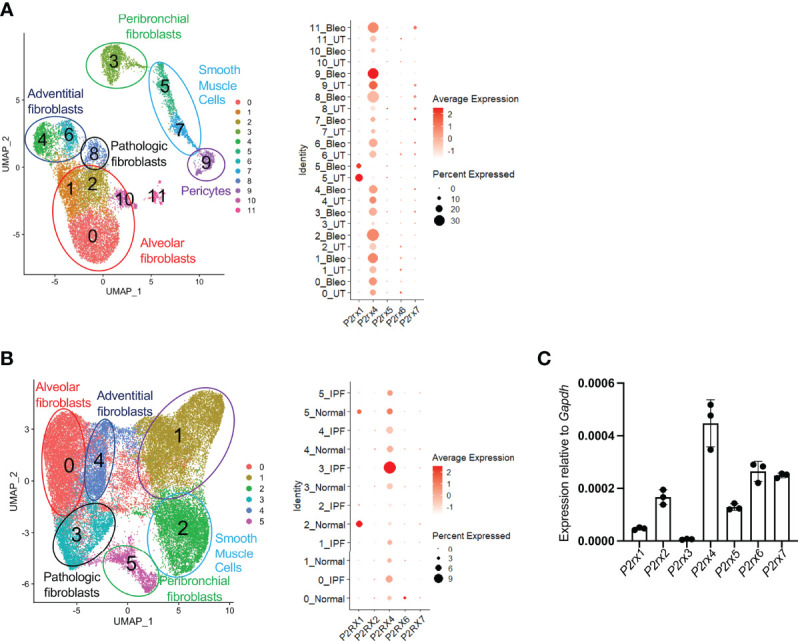

To pursue this hypothesis further, we first sought to elucidate the relevant ATP receptor in fibroblasts. We had previously identified 12 distinct subsets of collagen-producing cells from control mice and mice treated with bleomycin, as well as 6 distinct populations of collagen-producing cells from normal human lungs and lungs obtained at the time of transplant from patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (16). Using these datasets, we interrogated expression of all 7 ionotropic ATP receptors in lung fibroblasts by single cell scRNAseq. We found that, among the detected ATP ionotropic receptors, P2rx4 was the most highly expressed in nearly all populations of collagen-producing cells as measured by scRNAseq or qPCR ( Figures 3A–C ); notably, the scRNAseq data indicated that P2rx4 was increased with bleomycin injury and in IPF lung samples relative to control. The increases in P2rx4 were the most pronounced in the cellular subclusters previously found (16) to express the highest levels of pathologic extracellular matrix proteins (clusters 8 in mice and 3 in humans).

Figure 3.

P2rx4 is the most highly expressed ionotropic ATP receptor in lung fibroblasts. (A) UMAP plot of mouse fibroblasts from Tsukui et al. Dot plot shows expression of ionotropic ATP receptors. (B) UMAP plot of human fibroblasts from Tsukui et al. Dot plot shows expression of ionotropic ATP receptors. (C) qPCR of ionotropic ATP receptors in primary mouse lung fibroblasts isolated at steady state. N=3 mice.

Given the high expression of P2rx4 both at steady state and its even higher expression in pathologic fibrosis, we next tested the effect of fibroblast-specific P2rx4 deletion by crossing a P2rx4 floxed allele that we previously generated (15) to the Col1a2-CreERT2 allele (13). In the entire lung fibroblast population isolated from bleomycin-injured mice, there was a modest decrease in P2rx4 ( Figure 4A ); nonetheless, possibly because of focused expression of this collagen promoter-driven Cre in fibroblasts with high collagen production, fibroblasts from Col1a2-CreERT2:P2rx4 fl/fl mice had a pronounced decrease in collagen gene expression after bleomycin injury compared to wild type ( Figure 4A ). Conversely, collagen genes were induced by treatment of primary human and mouse lung fibroblasts with ATPγS (a non-hydrolyzable form of ATP; Figure 4B ). Importantly, fibroblast-specific P2rx4 KO mice using two different Cre drivers, the Col1a2-CreERT2 and the Pdgfrb-Cre, had decreased lung collagen after bleomycin injury compared to wild type ( Figure 4C ). Moreover, we confirmed that P2rx4 signals in fibroblasts via p38 MAP kinase ( Figure 4D ), which has previously found to be necessary for P2rx4 signaling in other systems (26, 27). Taken together, these results suggest a model of ATP signaling via fibroblast P2rx4 as a positive regulator of tissue fibrosis after injury ( Figure 4E ).

Figure 4.

P2rx4 is necessary for lung fibrosis. (A) qPCR for collagen genes and P2rx4 in primary mouse lung fibroblasts isolated from mice with fibroblast-specific P2rx4 deletion. N=3 mice. P values are for unpaired one-tailed t-tests. (B) qPCR for collagen genes in human (upper) and mouse (lower) primary lung fibroblasts treated with ATPγS. N=3 separate individuals and n=3 separate mice. P values are for unpaired two-tailed t-tests. (C) Left: Sirius red staining of lungs at 21 days post bleomycin injury in Col1a2-CreERT2: P2rx4 fl/fl or Col1a2-CreERT2 controls. Representative images are shown. Quantification is for n=3 mice. Scale bar=50μm. P value is for unpaired two-tailed t-test. Right: Hydroxyproline assays of whole lung collagen from mice with fibroblast-specific P2rx4 deletion with two different Cre drivers as indicated, and controls. N=3-10 as shown. P values are for one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. qPCR is for P2rx4 in fibroblasts isolated from Pdgfrb-Cre: P2rx4 fl/fl or Pdgfrb-Cre controls. N=6 mice in each group and P value is for Mann-Whitney test. (D) Western Blot of phospho-p38 and total p38 for fibroblasts isolated from Pdgfrb-Cre: P2rx4 fl/fl or Pdgfrb-Cre controls. Quantification shows the ratio of P-p38 to total p38 by densitometry. P value is shown for unpaired one-tailed t-test and n=3 mice. (E) Model of fibroblast activation by paracrine ATP derived from monocyte-derived macrophages in lung fibrosis.

Discussion

How macrophages regulate tissular remodeling in homeostasis and injury is an area of active investigation (28), and much of the focus of the recent literature has been on the ontogeny of macrophages that subserve various functions in pathologic states. A major emerging theme is the role of moMacs, which support a range of pathologic phenotypes in multiple disease models (29, 30). Lung fibrosis is no exception, with monocyte-lineage cells being shown to be associated with poor outcomes in multiple clinical cohorts (31) and in mouse models including our own prior work showing a pro-fibrotic effect of moMacs (1–3, 6). This pathologic effect of macrophages has been proposed to be related to macrophage-derived factors that both support fibroblast growth and lead to fibroblast activation, including TGFβ, PDGF, and other secreted factors (4–6).

Connexin hemichannel-mediated ATP efflux as a paracrine signaling mechanism has been described in multiple contexts (10, 11, 32). Here we found that Cx43 was necessary for lung moMac ATP efflux after bleomycin injury. Furthermore, deletion of Cx43 in moMacs decreased fibrosis, and we noted decreased cytosolic calcium in fibroblasts co-cultured with Cx43 KO moMacs. Both human and mouse lung fibroblasts had increased expression of collagen in response to ATPγS treatment. Thus, we tested the role in lung fibrosis of ATP receptor P2rx4, which we found was the most highly expressed ionotropic ATP receptor in both murine and human lung fibroblasts. Furthermore, fibroblast P2rx4 was upregulated in lung fibrosis and has previously been found both to have a pro-fibrotic role and to be necessary for fibroblast calcium in liver fibrosis (27). Using two different fibroblast Cre drivers, we found that fibroblast-specific deletion of P2rx4 decreased lung collagen in mice, both at the cellular and whole-lung levels. Taken together, these results motivate enthusiasm for therapeutic development of inhibitors to P2rx4, some of which exist but are of relatively low potency (33). Moreover, they support a novel hypothesis of profibrotic macrophage-fibroblast interaction based on macrophage efflux of ATP via connexin hemichannels.

Our study has several limitations. While the finding of elevated fibroblast cytosolic calcium dependent on macrophage co-culture was acquired in vitro, importantly, we also observed injury-induced calcium elevation in fibroblasts in precision-cut lung slices, a closer reflection of the biology of intact tissue. However, future studies should seek to confirm specifically within the context of lung slice imaging the dependence of this fibroblast calcium elevation on macrophages and on extracellular ATP, since other paracrine or cell autonomous factors may be relevant. Furthermore, our in vitro data do not rule out the possibility that macrophage Cx43 could have other effects separate from ATP efflux, including gap junctional communication or secretion of other profibrotic mediators that may regulate cytosolic calcium in adjacent fibroblasts in a paracrine manner. We add that it remains to be determined what initiates ATP efflux by macrophages, and whether the resolution of fibrosis results from downregulation of this signaling. The use of two Cre drivers for our analysis of the effects of fibroblast P2rx4 also deserves comment. We observed modest P2rx4 knockout in fibroblasts in aggregate with the Col1a2-CreERT2, which is likely due to mosaic expression with this driver, although it was reassuring to find consistent effects with the Pdgfrb-Cre, which achieved more marked knockout in fibroblasts in aggregate. Finally, the pathways downstream of P2rx4 that drive expression of collagen genes in fibroblasts, including the role of calcium and p38 MAP kinase signaling, will require further elucidation. Despite these limitations, our results reveal a novel role for macrophages in paracrine regulation of fibroblast calcium, as well as a specific dependency on Cx43, and raise the profile of P2rx4 as a potential therapeutic target for lung fibrosis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by UCSF Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The animal study was reviewed and approved by UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Program.

Author Contributions

AB, PT, and PY performed all experiments under the guidance of MB. Imaging experiments were performed by PT and AB under the direction of JJ, X-ZT, and CA. KB and TC prepared breeding and experimental stocks of genetically modified mice under the guidance of PT and MB. RM contributed P2rx4 floxed mice. TT performed analysis of single cell RNA-seq data under the supervision of DS. RS and SN isolated and provided human lung fibroblasts for analysis. MB conceived of the work, supervised experimental planning and execution, and wrote the manuscript with input from AB, PT and RM. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the US Department of Defense (W81XWH2110417 to MB), the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute (DP2HL117752 to CA), the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases (R21AI130495 to CA), the UCSF Cardiovascular Research Institute, and the UCSF Sandler Asthma Basic Research Center.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hui Liu and Janet Iwasa for their contribution of artwork for Figure 4E . Drawings in Figures 1A–C , 2A were created under license with BioRender.com.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.880887/full#supplementary-material

5-minute time-lapse video corresponding to Figure 1B , with images acquired every 5 seconds by two-photon calcium imaging of precision-cut lung slices from steady-state Col1a2-CreERT2: R26-LSL-Salsa6f(tdTomato-GCaMP): MacBlue mice. Scale is as for Supplementary Video 2 .

20-minute time-lapse video corresponding to Figure 1B , with images acquired every 5 seconds by two-photon calcium imaging of precision-cut lung slices from Col1a2-CreERT2: R26-LSL-Salsa6f(tdTomato-GCaMP): MacBlue mice 7 days post-bleomycin injury. Scale is as for Supplementary Video 2 .

References

- 1. Misharin AV, Morales-Nebreda L, Reyfman PA, Cuda CM, Walter JM, Mcquattie-Pimentel AC, et al. Monocyte-Derived Alveolar Macrophages Drive Lung Fibrosis and Persist in the Lung Over the Life Span. J Exp Med (2017) 214:2387–404. doi: 10.1084/jem.20162152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Satoh T, Nakagawa K, Sugihara F, Kuwahara R, Ashihara M, Yamane F, et al. Identification of an Atypical Monocyte and Committed Progenitor Involved in Fibrosis. Nature (2017) 541:96–101. doi: 10.1038/nature20611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aran D, Looney AP, Liu L, Wu E, Fong V, Hsu A, et al. Reference-Based Analysis of Lung Single-Cell Sequencing Reveals a Transitional Profibrotic Macrophage. Nat Immunol (2019) 20:163–72. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0276-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larson-Casey JL, Deshane JS, Ryan AJ, Thannickal VJ, Carter AB. Macrophage Akt1 Kinase-Mediated Mitophagy Modulates Apoptosis Resistance and Pulmonary Fibrosis. Immunity (2016) 44:582–96. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou X, Franklin RA, Adler M, Jacox JB, Bailis W, Shyer JA, et al. Circuit Design Features of a Stable Two-Cell System. Cell (2018) 172:744–57.e717. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhattacharyya A, Boostanpour K, Bouzidi M, Magee L, Chen TY, Wolters R, et al. IL10 Trains Macrophage Pro-Fibrotic Function After Lung Injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol (2022) 322:L495–502. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00458.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Janssen LJ, Farkas L, Rahman T, Kolb MR. ATP Stimulates Ca(2+)-Waves and Gene Expression in Cultured Human Pulmonary Fibroblasts. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2009) 41:2477–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lembong J, Sabass B, Sun B, Rogers ME, Stone HA. Mechanics Regulates ATP-Stimulated Collective Calcium Response in Fibroblast Cells. J R Soc Interface (2015) 12:20150140. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Idzko M, Ferrari D, Eltzschig HK. Nucleotide Signalling During Inflammation. Nature (2014) 509:310–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li W, Bao G, Chen W, Qiang X, Zhu S, Wang S, et al. Connexin 43 Hemichannel as a Novel Mediator of Sterile and Infectious Inflammatory Diseases. Sci Rep (2018) 8:166. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18452-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dosch M, Zindel J, Jebbawi F, Melin N, Sanchez-Taltavull D, Stroka D, et al. Connexin-43-Dependent ATP Release Mediates Macrophage Activation During Sepsis. Elife (2019) 8:e42670. doi: 10.7554/eLife.42670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zumerle S, Cali B, Munari F, Angioni R, Di Virgilio F, Molon B, et al. Intercellular Calcium Signaling Induced by ATP Potentiates Macrophage Phagocytosis. Cell Rep (2019) 27:1–10.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. He L, Huang X, Kanisicak O, Li Y, Wang Y, Li Y, et al. Preexisting Endothelial Cells Mediate Cardiac Neovascularization After Injury. J Clin Invest (2017) 127:2968–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI93868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Foo SS, Turner CJ, Adams S, Compagni A, Aubyn D, Kogata N, et al. Ephrin-B2 Controls Cell Motility and Adhesion During Blood-Vessel-Wall Assembly. Cell (2006) 124:161–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ozaki T, Muramatsu R, Sasai M, Yamamoto M, Kubota Y, Fujinaka T, et al. The P2X4 Receptor Is Required for Neuroprotection via Ischemic Preconditioning. Sci Rep (2016) 6:25893. doi: 10.1038/srep25893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsukui T, Sun KH, Wetter JB, Wilson-Kanamori JR, Hazelwood LA, Henderson NC, et al. Collagen-Producing Lung Cell Atlas Identifies Multiple Subsets With Distinct Localization and Relevance to Fibrosis. Nat Commun (2020) 11:1920. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15647-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sullivan BM, Liang HE, Bando JK, Wu D, Cheng LE, Mckerrow JK, et al. Genetic Analysis of Basophil Function In Vivo . Nat Immunol (2011) 12:527–35. doi: 10.1038/ni.2036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D, Schier AF, Regev A. Spatial Reconstruction of Single-Cell Gene Expression Data. Nat Biotechnol (2015) 33:495–502. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Finkbeiner WE. "Respiratory Cell Culture". In: R.G C, editor. The Lung: Scientific Foundations. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; (1997). p. 415–33. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taylor SC, Berkelman T, Yadav G, Hammond M. A Defined Methodology for Reliable Quantification of Western Blot Data. Mol Biotechnol (2013) 55:217–26. doi: 10.1007/s12033-013-9672-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blackwell TS, Tager AM, Borok Z, Moore BB, Schwartz DA, Anstrom KJ, et al. Future Directions in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Research. An NHLBI Workshop Report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2014) 189:214–22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1141WS [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dong TX, Othy S, Jairaman A, Skupsky J, Zavala A, Parker I, et al. T-Cell Calcium Dynamics Visualized in a Ratiometric Tdtomato-GCaMP6f Transgenic Reporter Mouse. Elife (2017) 6:e32417. doi: 10.7554/eLife.32417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ovchinnikov DA, Van Zuylen WJ, Debats CE, Alexander KA, Kellie S, Hume DA. Expression of Gal4-Dependent Transgenes in Cells of the Mononuclear Phagocyte System Labeled With Enhanced Cyan Fluorescent Protein Using Csf1r-Gal4VP16/UAS-ECFP Double-Transgenic Mice. J Leukoc Biol (2008) 83:430–3. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Molawi K, Wolf Y, Kandalla PK, Favret J, Hagemeyer N, Frenzel K, et al. Progressive Replacement of Embryo-Derived Cardiac Macrophages With Age. J Exp Med (2014) 211:2151–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fidler TP, Xue C, Yalcinkaya M, Hardaway B, Abramowicz S, Xiao T, et al. The AIM2 Inflammasome Exacerbates Atherosclerosis in Clonal Haematopoiesis. Nature (2021) 592:296–301. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03341-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Trang T, Beggs S, Wan X, Salter MW. P2X4-Receptor-Mediated Synthesis and Release of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Microglia Is Dependent on Calcium and P38-Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activation. J Neurosci (2009) 29:3518–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5714-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Le Guilcher C, Garcin I, Dellis O, Cauchois F, Tebbi A, Doignon I, et al. The P2X4 Purinergic Receptor Regulates Hepatic Myofibroblast Activation During Liver Fibrogenesis. J Hepatol (2018) 69:644–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guilliams M, Thierry GR, Bonnardel J, Bajenoff M. Establishment and Maintenance of the Macrophage Niche. Immunity (2020) 52:434–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ginhoux F, Schultze JL, Murray PJ, Ochando J, Biswas SK. New Insights Into the Multidimensional Concept of Macrophage Ontogeny, Activation and Function. Nat Immunol (2016) 17:34–40. doi: 10.1038/ni.3324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mulder K, Patel AA, Kong WT, Piot C, Halitzki E, Dunsmore G, et al. Cross-Tissue Single-Cell Landscape of Human Monocytes and Macrophages in Health and Disease. Immunity (2021) 54:1883–900.e1885. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scott MKD, Quinn K, Li Q, Carroll R, Warsinske H, Vallania F, et al. Increased Monocyte Count as a Cellular Biomarker for Poor Outcomes in Fibrotic Diseases: A Retrospective, Multicentre Cohort Study. Lancet Respir Med (2019) 7:497–508. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30508-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kang J, Kang N, Lovatt D, Torres A, Zhao Z, Lin J, et al. Connexin 43 Hemichannels Are Permeable to ATP. J Neurosci (2008) 28:4702–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5048-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Braganca B, Correia-De-Sa P. Resolving the Ionotropic P2X4 Receptor Mystery Points Towards a New Therapeutic Target for Cardiovascular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21:5005. doi: 10.3390/ijms21145005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

5-minute time-lapse video corresponding to Figure 1B , with images acquired every 5 seconds by two-photon calcium imaging of precision-cut lung slices from steady-state Col1a2-CreERT2: R26-LSL-Salsa6f(tdTomato-GCaMP): MacBlue mice. Scale is as for Supplementary Video 2 .

20-minute time-lapse video corresponding to Figure 1B , with images acquired every 5 seconds by two-photon calcium imaging of precision-cut lung slices from Col1a2-CreERT2: R26-LSL-Salsa6f(tdTomato-GCaMP): MacBlue mice 7 days post-bleomycin injury. Scale is as for Supplementary Video 2 .

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article.