Abstract

Metagenome assembly is a core yet methodologically challenging step for taxonomic classification and functional annotation of a microbiome. This study aims to generate the high-resolution human gut metagenome using both Illumina and Nanopore platforms. Assembly was achieved using four assemblers, including Flye (Nanopore), metaSPAdes (Illumina), hybridSPAdes (Illumina and Nanopore), and OPERA-MS (Illumina and Nanopore). Hybrid metagenome assembly was shown to generate contigs with almost same sizes comparable to those produced using Illumina reads alone, but was more contiguous, informative, and longer compared with those assembled with Illumina reads only. In addition, hybrid metagenome assembly enables us to obtain complete plasmid sequences and much more AMR gene-encoding contigs than the Illumina method. Most importantly, using our workflow, 58 novel high-quality metagenome bins were obtained from four assembly algorithms, particularly hybrid assembly (47/58), although metaSPAdes could provide 11 high-quality bins independently. Among them, 29 bins were currently uncultured bacterial metagenome-assembled genomes. These findings were highly consistent and supported by mock community data tested. In the analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), the number of BGCs in the contigs from hybridSPAdes (241) is higher than that of contigs from metaSPAdes (233). In conclusion, hybrid metagenome assembly could significantly enhance the efficiency of contig assembly, taxonomic binning, and genome construction compared with procedures using Illumina short-read data alone, indicating that nanopore long reads are highly useful in metagenomic applications. This technique could be used to create high-resolution references for future human metagenome studies.

Keywords: human metagenome, Illumina, nanopore, hybrid assembly, high resolution

Introduction

The human gut microbiome is a dynamic and complex microbial ecosystem dominated by bacteria, which interact with the host and directly impact human physiology (Lloyd-Price et al., 2016; Forster et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2021). Classical studies of the gut microbiome were largely dependent on cultivation techniques. However, traditional methods only cultivate 10–30% of gut microbiota (Suau et al., 1999; Tannock, 2001; Sokol and Seksik, 2010). With the rapid development of advanced molecular technologies such as PCR-denaturing gel electrophoresis, it has been demonstrated that the gut microbial ecosystem is more complex than previously thought (Eckburg et al., 2005). In recent years, several next-generation sequencing technologies have been developed (Shendure and Ji, 2008; Fuller et al., 2009; Zhong et al., 2021), thus further facilitating analysis of a large number of microorganism in different environment (Tyson et al., 2004; Venter et al., 2004; Tringe et al., 2005) and human body sites (Ding and Schloss, 2014), including the human gut (Huttenhower et al., 2012; Methé et al., 2012; Tyakht et al., 2013). 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis has been used to study uncultivated gut microbial communities, which focused on the sequence of the conserved 16S rRNA gene present in all microbes (Woese and Fox, 1977; Cole et al., 2006; Oyewusi et al., 2021), and has established a series of novel connections between intestinal microbiota and disease (Cho and Blaser, 2012; Blaser et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2022). Advent of shotgun metagenome sequencing substantially resolved the technical difficulties associated with taxonomic classification and functional annotation of gut microbiome by offering a way to assess the entire genomic contents (Lloyd-Price et al., 2016; Almeida et al., 2019; Forster et al., 2019; Peterson et al., 2021). With the recent advance in computational approaches, the recovery of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from highly diverse communities was accessible via de novo assembling shotgun metagenomic reads into contig sequences and binning the assembled contigs with similar sequence composition, taxonomic affiliations, and coverage depth (Truong et al., 2015; Parks et al., 2017; Quince et al., 2017; Uritskiy et al., 2018). Metagenome assembly is methodologically more challenging compared with the assembly of single isolates due to the inability to distinguish between closely related community members in both the assembly and binning processes, which limits the accuracy of MAGs-related analyses (Parks et al., 2017; Truong et al., 2017; Forster et al., 2019). Extensive work has been conducted to expand the tree of life by recovering MAGs with high accuracy and completeness, including establishment of reference genome catalogs through cultivation of human gut bacteria, such as Human Microbiome Project (HMP) (Turnbaugh et al., 2007; Integrative et al., 2019) and Human Gastrointestinal Bacteria Genome Collection (HGG) (Forster et al., 2019), increasing the sample size of gut microbiota sequenced with the reference-free and culture-independent approach as well as improving the sequencing output by using long reads generated from third-generation sequencing platforms like Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing (Bleidorn, 2016; Frank et al., 2016; Mukherjee et al., 2017; Almeida et al., 2019; Bertrand et al., 2019; Pasolli et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2019).

Theoretically, long-read sequencing technologies can overcome many problems associated with those using short reads such as the poor contiguity and ambiguity in metagenome assemblies, but they are more expensive and error-prone (Frank et al., 2016; Wick et al., 2017; Bertrand et al., 2019). The hybrid genome assembly approach that employs reads generated by different platforms is a powerful way to retain the advantage of both short- and long-read sequencing methods and generate larger contigs with fewer misassemblies (Mostovoy et al., 2016; Wick et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2018). It has been successfully applied for the study of human genomes and single bacterial colonies, and there are only a few reports on the use of such a method in microbiome-related studies (Mostovoy et al., 2016; Wick et al., 2017; Jain et al., 2018b; Ma et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021). Frank et al. (2016) reported the enhanced genome construction of the complex microbial community in a commercial biogas reactor by using the combination of Illumina short reads and PacBio long-read circular consensus sequence (CCS) data. Bertrand et al. (2019) recently developed another hybrid metagenome assembler, OPERA-MS, which could accurately generate near-complete genomes from metagenomes with relatively low coverage of long reads (∼9×). Since SMRT sequencing is currently inaccessible to most laboratories because of its high cost and laborious preparation procedure, researchers often work with the portable MinION device available from ONT (Li et al., 2018). Although hybrid approach recovered high-quality MAGs from a complex aquifer system Overholt et al. (2020) and Jin et al. (2022) used MetaBAT2 to assemble 475 high-quality MAGs by HiSeq-PacBio hybrid, there were few reports on the assessment of different hybrid assemblers and Metagenome-assembled genome binning methods.

In this study, we present an application and one novel workflow of combined nanopore MinION long reads and Illumina short reads data in a complex gut microbial community of a healthy man. We compared the contiguity and accuracy of the assemblies of HiSeq X10 short reads, MinION nanopore long reads, and hybrid assemblies from both platforms. A staggered mock community was also constructed to compare the assembly quality from different assembling strategies with ground-truth reference. We demonstrated that, with the advance in data analysis tools, the workflow is feasible for MAG recovery, and that these MAGs can serve as valuable high-resolution references for studying human gut microbiota.

Materials and Methods

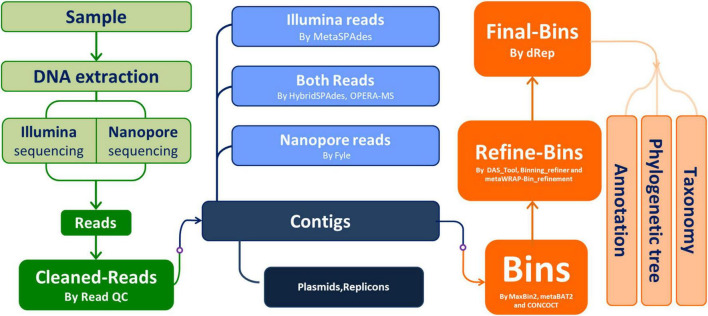

The major workflow of this study is depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Workflow of this study. The starting sample was the stool sample from a “healthy” Chinese young man.

High-Molecular-Weight DNA Extraction

Metagenomic DNA extraction was carried out using QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, United States), E.Z.N.A. stool DNA kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, United States), and FastDNA® SPIN Kit (Bio 101, Carlsbad, CA, United States) from the fecal sample of a young healthy man who was 29 years of age, weighing 70 kg, and height 168 cm according to the instructions of the manufacturer. However, E.Z.N.A. Stool DNA Kit and FastDNA SPIN Kit generated a majority of DNA fragments of <5 kb, which were not suitable for nanopore sequencing. DNA was finally extracted using QIAamp DNA with minor modifications. Briefly, we followed the major instructions in the section “Isolation of DNA from stool for pathogen detection” in the second step. After weighing the fresh stool and adding 1 ml InhibitEX Buffer, one sterile 1-ml tip was used to smash the stool and some 0.5 mm sterile glass beads were added to help homogenize the sample. In the fifth step, 2 μl 20 mg/ml RNase A from PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit were added; the final volume of sterile water to elute DNA was reduced to 50 μl to obtain DNA with increased concentration. To reduce short DNA fragments, 0.5 × Agencourt AMPure XP beads were used. The quality and quantity of DNA were evaluated by running a 0.5% agarose gel and using the Qubit™ dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, United States), respectively. Finally, DNA with high molecular weight (modal size >5 kbp) and sufficient quantity (>20 μg) for sequencing (Supplementary Figure 6) was extracted from the stool sample of a healthy young man without any overt disease as described previously (Aagaard et al., 2013).

Construction of BMS21 Mock Community

The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) was used to purchase eight bacterial strains, including Acinetobacter baumannii (ATCC 19606), Enterococcus faecium (ATCC 29212), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 13883), Lactobacillus casei (ATCC 393), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), Pseudomonas putida (ATCC 12633), and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213). A total of 13 other strains belonging to different species, including Enterobacter asburiae, Hafnia alvei, Serratia liquefaciens, Providencia rettgeri, Providencia heimbachae, E. coli, Ideonella dechloratans, Morganella morganii, Escherichia cloacae, Vibrio vulnificus, Streptococcus faecalis, and Lactobacillus spp. isolated from human feces, pig feces, yogurt, and shrimp samples, were stock strains from our lab. DNA extraction was carried out using the PureLink™ Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Integrity of extracted DNA was inspected on 0.5% agarose gel. DNA concentration was determined by Qubit dsDNA BR assay. A staggered mock community, BMS21, was constructed by pooling DNA for the 21 strains in different abundance levels varying from 0.1 to 30% (Supplementary Table 12). DNA of individual isolates, the BMS21 mock community, and the human metagenome were also subjected to quality and quantity evaluation with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). The comparative assessment of BMS21 was carried using AMBER (Meyer et al., 2018) which provides commonly used metrics for assessing the quality of metagenome binnings on benchmark datasets.

Illumina and Nanopore MinION Sequencing of Metagenomics DNA Sample

DNA of individual isolates, the mock community, and the human metagenome were subjected to both Illumina short-read and nanopore long-read sequencing. Illumina paired-end libraries were prepared by the focused acoustic shearing method with the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit and the Multiplex Oligos Kit for Illumina (NEB) (Li et al., 2018). The libraries were quantified by employing quantitative PCR with P5-P7 primers, and were pooled together and sequenced in the HiSeq X10 platform according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). After read trimming and removal of the human reads, a total of 26 Gb 2 × 150 bp pair-end sequencing data was generated by the Illumina HiSeq X10 apparatus. Libraries of nanopore long-read sequencing were prepared with the Rapid Barcoding Sequencing Kit (SQK-RBK004) and flowcell R9.4 according to the protocols of the manufacturer. The sequencing run was stopped after 8 h, and the flow cell was washed by a Wash Kit (EXP-WSH002) (Li et al., 2018).

Metagenome Assembly, Contiguity Estimation, and Metagenome Binning

Illumina raw reads were trimmed and sequences belonging to the human genome were removed using the READ_QC module in metaWRAP version 1.1.5 (Uritskiy et al., 2018). Nanopore reads were basecalled and debarcoded with guppy version 3.1. Nanopore reads were assembled into contigs with Flye version 2.9 (Kolmogorov et al., 2020) using a genome size of 100 Mbp, and the Illumina reads were assembled using metaSPAdes version 3.15.3 using default parameters (Koren et al., 2017; Nurk et al., 2017). Hybrid assembly of reads from both platforms was conducted using hybridSPAdes version 3.15.3 (Bankevich et al., 2012) and OPERA-MS (Bertrand et al., 2018), respectively. MetaQUAST version 5.0.2 was used to evaluate all metagenome assemblies and obtain statistics including N50, genes assembled and misassembly errors (Mikheenko et al., 2015). Specifically, misassemblies is the number of positions in the assembled contigs where the left flanking sequence aligns over 1 kb away from the right flanking sequence on the reference or they overlap on more than 1 kbp or flanking sequences align on different strands or different chromosomes. The PlasFlow (Krawczyk et al., 2018) was used to classify the contigs generated by four assemblers. Binning of metagenomic contigs was conducted using MaxBin 2.0 (Wu et al., 2015), MetaBAT2 (Kang et al., 2015), and CONCOCT (Alneberg et al., 2014) embedded in metaWRAP version 1.1.5 using default parameters (Uritskiy et al., 2018). A refinement step was then performed using the bin_refinement module from MetaWRAP to combine and improve the results generated by the three binners, the cutoff value of genome completeness was set to 50%, and that of contamination was 10% (Uritskiy et al., 2018). Self-mapping was conducted with Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) and SAMtools (Li et al., 2009). The running times/memory consumption of the assemblers are described in the Supplementary Table 13.

Dereplication and Characterization of the Metagenome-Assembled Bins

The refined bins generated for contigs from each metagenome assembly methods were subsequently dereplicated with dRep version 2.3.2 to extract the MAGs displaying the best quality and representing individual metagenomic species (Olm et al., 2017). The lineage, completeness, and contamination of the recovered MAG were estimated using CheckM version 1.1.3 (Parks et al., 2015) with lineage-specific marker genes. The GTDB-Tk was used to identify the classification of bins. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) of the bins with related genomes was calculated using OrthoANI (Lee et al., 2016). SNP calculation was conducted using snippy version 3.2 (Seemann, 2015).

Assignment of Metagenome-Assembled Genomes to Reference Databases

Three reference databases were used to classify the set of MAGs in our study recovered from the human gut microbiome, namely, HR, RefSeq, and a collection of MAGs from public datasets. HR comprised a total of 2,110 high-quality genomes (>90% completeness and <5% contamination) retrieved from both the HMP catalog1 and the HGG (Forster et al., 2019). From the RefSeq database, we used all the complete bacterial genomes and chromosome available (n = 30,057). Finally, we surveyed 92,143 MAGS database (Almeida et al., 2019)2. For each database, FastANI was used to calculate the whole-genome ANI (Jain et al., 2018a). Subsequently, each MAG and its closest relative compared their aligned sequence fragments. These unclassified MAGs were clustered into phylum level using GTDB-Tk (Chaumeil et al., 2020).

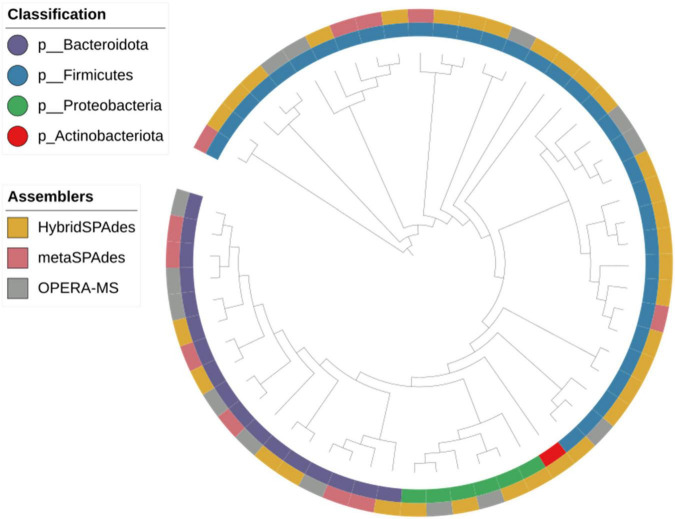

Phylogeny of the Metagenome-Assembled Bins

Using specI version 1.0, forty universal core marker genes from each genome bin were extracted (Mende et al., 2013). Phylogenetic trees were built by concatenating and aligning the marker genes with MUSCLE version 3.8.31 (Edgar, 2004). Marker genes absent only from specific genomes were kept in the alignment as missing data. Maximum-likelihood trees were constructed using RAxML version 8.2.11 with option -m PROTGAMMAAUTO. All phylogenetic trees were visualized and modified in iTOL (Stamatakis, 2014; Letunic and Bork, 2016).

Analysis of Plasmids, Mobile Elements, and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

Plasmid sequences were identified by looking for plasmid replicons using PlasmidFinder 2.1 (Carattoli et al., 2014) and PlasFlow (Krawczyk et al., 2018). Completeness of the plasmids was identified by inspecting the similarity of plasmid sequences at both ends. Acquired antibiotic resistance genes were identified with ResFinder 2.1 using the genome assemblies as input (Zankari et al., 2012). Antibiotic resistance genes with >98% of the sequence aligning to the contig with an identity >99% were selected for further analysis. Insertion sequences were identified using ISfinder (Siguier et al., 2006). Plasmids were annotated with the RAST server (Overbeek et al., 2013). Map of plasmids was plotted using BRIG (Alikhan et al., 2011).

Results

Hybrid Metagenome Assembly Improves Assembly Quality

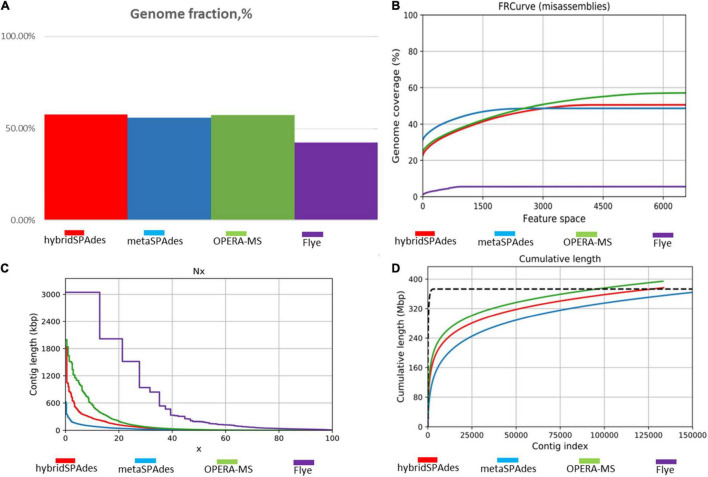

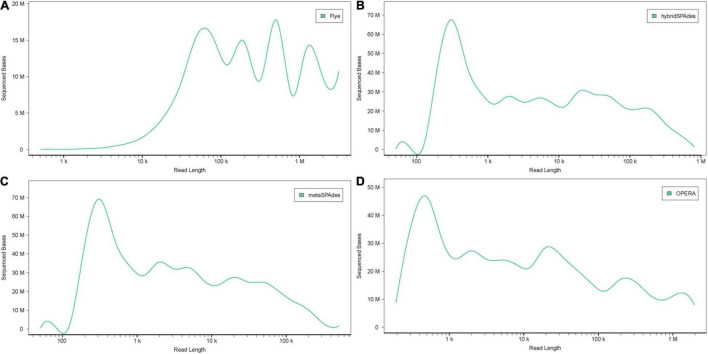

Two nanopore MinION flow cells generated a total of 1,205,055 base-called reads containing 5.4 gigabases, with a read N50 (read length refers to reads equal to or longer than this length in at least half of the total bases) of 9,521 bp and a maximum read length of 85,079 bp (Supplementary Figure 1). To analyze data generated by the two different sequencing platforms, multiple metagenome assembly algorithms were used. The metaSPAdes version 3.15.3 program was used to assemble the HiSeq X10 reads and generate 150,855 contigs with a size larger than 0.5 kb, a maximum length of 595,004 bp, and an average contig length of 2,400 bp. Flye version 2.9 was used to assemble the nanopore MinION reads and generated 1,968 contigs (>0.5 kb) averaging 74,028 bp, with the maximum contig length of 2,947,413 bp. Hybrid metagenome assembly with both short- and long-sequencing reads was conducted with two software, hybridSPAdes version 3.15.3 and the recently developed hybrid metagenomic assembler OPERA-MS. Assembly with hybridSPAdes produced 131,093 contigs (>0.5 kb) with an average size of 2,854 bp and a maximum contig length of 807,998 bp. OPERA-MS assembly generated 134,680 contigs (>0.5 kb) with an average length of 2,813 bp and a maximum contig length of 3,008,007 bp. The N50 of contigs (>500) assembled from metaSPAdes, Flye, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS were 6,048, 227,485, 11,867, and 12,770, respectively. Numbers of contigs longer than 500 kb that were assembled by Flye, metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS were 48, 2, 11, and 39, respectively (Table 1), suggesting that the use of nanopore long-reads improved the assembly contiguity of human metagenome. Hybrid assemblies using OPERA-MS and hybridSPAdes generated metagenome sizes that were similar to those generated by the short-read-only assembly using metaSPAdes, 378, 374, and 362 Mb, respectively. Such sizes were around 2.5-fold the total assembly size from Flye assembly (142 Mb). The self-mapping rates of Illumina short pair-end reads to four assemblies were 45.5% (Flye), 79.0% (OPERA-MS), 94.2% (metaSPAdes), and 95.5% (hybridSPAdes), respectively. Comparison of the assembly statistics of the four assemblies showed that assembly with the nanopore reads alone generated the longest contigs, but the total assembly size and the assembly accuracy were much lower than those generated by the other three assembly methods involving Illumina short reads (Figures 2C, 3, Table 1, and Supplementary Table 1). Considering the high-cost, high error rate, low-throughput of long-read sequencing and taking datasets generated in this study into account (Figure 4), Illumina short-read sequencing was considered essential for improving the accuracy and completeness of metagenome assembly.

TABLE 1.

Assembly statistics of different assembly algorithms for the healthy human gut microbiome.

| Reads | Assembly method | No. of contigs (>500 bp) | No. of contigs (>1 Mb) | No. of contigs (>500 kb) | No. of contigs (>100 kb) | Total assembly size (Mb)* | Mean (bp) | Median (bp) | Max (bp) |

| Nanopore | Flye v2.9 | 1968 | 20 | 48 | 267 | 145 | 74,028 | 28,893 | 2,947,413 |

| HiSeq X10 | metaSPAdes v3.15.3 | 150,854 | 0 | 2 | 197 | 362 | 2,400 | 897 | 595,004 |

| Hybrid | hybridSPAdes v3.15.3 | 131,093 | 0 | 11 | 342 | 374 | 2,854 | 866 | 807,998 |

| Hybrid | OPERA-MS | 134680 | 15 | 39 | 293 | 378 | 2,813 | 842 | 1,996,746 |

*Contigs less than 500 bp were not calculated.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of the healthy human gut metagenome assembly statistics from the four different assembly methods. (A) Genome fraction depicted by different methods. Genome fraction is the percentage of aligned bases in the reference genome. A base in the reference genome is aligned if there is at least one contig with at least one alignment to this base. Contigs from repetitive regions may map to multiple places, and thus may be counted multiple times. (B) Feature-response misassembly curve. Y is the total number of aligned bases divided by the reference length, in the contigs having the total number of misassemblies at most X. FRCurve definition: given any such set of features, the response (quality) of the assembler output is then analyzed as a function of the maximum number of possible errors (features) allowed in the contigs. (C) Percentage distribution (X-axis) of contig length (Y-axis) with the four methods. (D) Cumulative number of assembled nucleotides in contigs of different lengths. Each line corresponds to a different assembly program (hybridSPAdes, metaSPAdes, OPERA-MS, and Flye).

FIGURE 3.

Accumulative distribution of contig length with the four methods: (A) Flye, (B) hybridSPAdes, (C) metaSPAdes, and (D) OPERA-MS. The X and Y axis represent the length (bp) and number of the contigs, respectively.

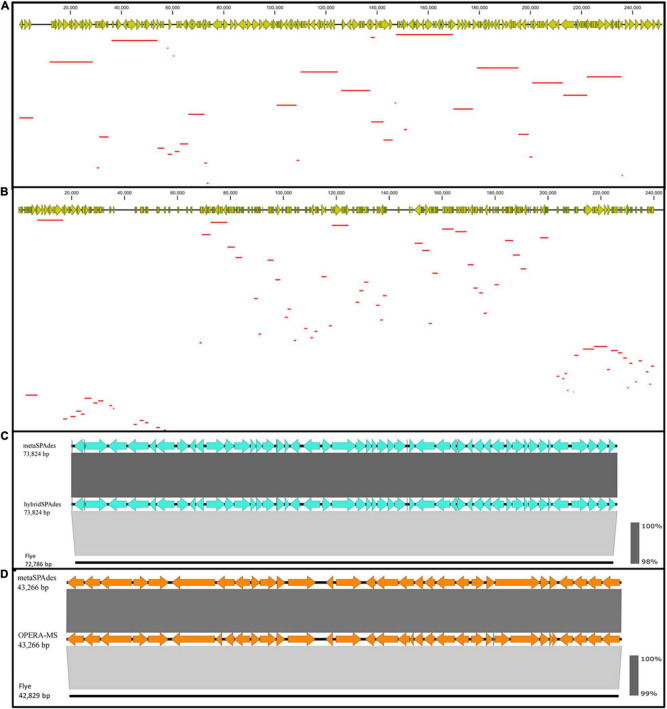

FIGURE 4.

Contiguity and accuracy of assembly with four different assembly algorithms. BLASTN of a 242,790 bp (A) and 242,845 bp (B) contigs assembled using hybrid assembly methods, hybridSPAdes (A), and OPERA-MS (B) against the metaSPAdes assembly with Illumina reads alone. This result indicated that the hybrid assembly generates more contiguous contigs. Linear alignment of contigs assembled using hybridSPAdes [(C) ∼73,824 bp] and OPERA-MS [(D) ∼43,266 bp] with assemblies constructed using Flye and metaSPAdes. The results indicated that the hybrid assembly generated contigs with high accuracy. The red lines represent Illumina contigs matched to hybrid assembled contig.

To demonstrate the contiguity of hybrid assembly, alignment between contigs generated by OPERA-MS/hybridSPAdes and metaSPAdes was conducted. A total of 32 contigs assembled with metaSPAdes were aligned to a 242,790 bp contig generated by hybridSPAdes. Such contig was found to encode 185 ORFs whose size ranged from 248 bp to 22,228 bp when generated by hybridSPAdes. Among these 32 contigs, only 6 are longer than 10,000 bp (Figure 4A). A BLAST search in the NCBI Nucleotide collection (nr/nt) database indicated that it was 81.84% identical to the Sutterella sp. KGMB03119 chromosome sequence (accession: CP040882.1) at 21% coverage, indicating that this contig may originate from an unknown genome. Consistently, a total of 77 contigs ranging from 630 bp to 9,772 bp assembled with metaSPAdes were aligned to a 242,845 bp OPERA-MS-generated contig that comprised 328 genes. The 77 contigs comprised a total of 201 genes, with the majority being less than 5 kb. A BLAST search in the NCBI database suggested it was a novel sequence that was 94.50% identical to the chromosomal sequence of E. coli strain 602354 (accession: CP025847.1) at 29% coverage (Figure 4B). The sequence alignment results indicated that a hybrid metagenome assembly contains more contiguous and informative, as well as longer contigs compared to those assembled with Illumina reads only. Assembly with the Illumina reads alone generated contigs with the highest accuracy, but the low contiguity of such contigs limits their application potential. Hybrid metagenome assembly with both nanopore long- and Illumina short reads could be an effective approach that integrates the strength of both sequencing platforms. The two currently available hybrid metagenome assembly algorithms, OPERA-MS and hybridSPAdes, enabled high-quality assemblies with low-coverage nanopore long reads and fragmented Illumina short reads, with the former performing better on the contiguity (number of long contigs which are >500 kb, Table 1). The difference in performance could be due to the difference in the discrimination and assembly principles of the two algorithms. HybridSPAdes conducts hybrid assembly by mapping the third-generation long reads to the assembly of second-generation short reads, and OPERA-MS integrates a novel assembly-based metagenome clustering technique with an exact scaffolding algorithm that can efficiently assemble repeat-rich sequences (Antipov et al., 2015; Bertrand et al., 2019).

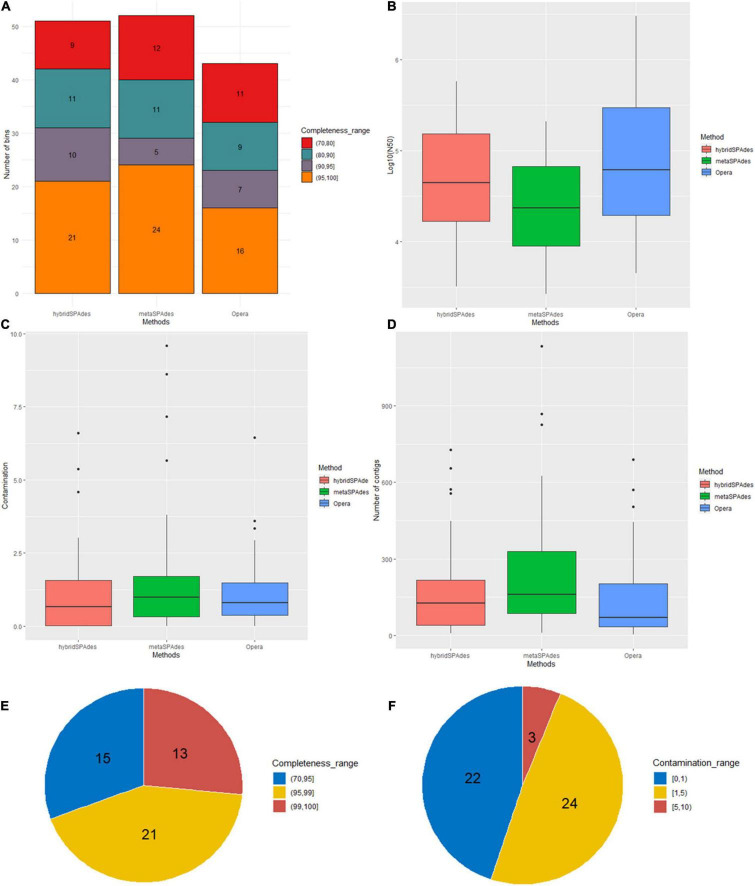

Construction of Near-Complete and High-Fidelity Metagenome Bins With Hybrid Assembly Algorithms

Binning of the assembled metagenome sequences generated with the four algorithms (metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS) was conducted using three different software (MaxBin2, MetaBAT2, and concoct), resulting in generation of primary metagenome bins (Table 2, Supplementary File 1, and Supplementary Table 2). The metaSPAdes assembler generated 349 bins. The number of bins with less than 100 contigs was 142. In these bins, only 38 were at the completeness of >50% and <10% contamination, and the number of high quality (completeness >95% and contamination <3%) were 19. A total of 199 bins were generated by OPERA-MS assembler and the number of bins with less 100 contigs was 81, 21% (42) of which exhibited completeness of >50% and <10% contamination and 9.5% (19) were high-quality bins. A total of 179 of the 373 bins assembled by hybridSPAdes with less 100 contigs were at completeness of >50% and contamination. The number of high-quality (completeness >95% and contamination <3%) bins was 28 (7.4%). The N50 of the contigs in each bin were 1,999–573,607 (metaSPAdes), 2,728–3,008,073 (OPERA-MS), and 1,024–596,353 (hybridSPAdes), respectively (Supplementary File 1). Comparison with bins from metaSPAdes, bins assembled by Illumina and nanopore reads show higher quality and better quantity. The primary bins were refined with DAS_Tool and finalized using metaWRAP-Bin_refinement using a completeness cutoff of 50% and contamination cutoff of 10%. A total of 156 bins were obtained from different metagenome assemblies, including 52, 51, and 53 from, metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS, respectively (Figure 5A). The number of bins and the corresponding bin completeness generated by metaSPAdes and hybridSPAdes are similar, which are slightly more than that recorded in hybrid assembly using OPERA-MS, but the number of contigs in each bin decreased in bins of hybrid assembled contigs compared with contigs assembled with the Illumina reads alone (Figure 5D and Supplementary File 1). The N50 of the contigs in each bin were, respectively, 2,642–209,184 bp (metaSPAdes), 3,163–578,001 bp (hybridSPAdes), and 4,467–3,008,073 bp (OPERA-MS) (Figure 5B). The numbers of bins with less than 100 contigs are 17 (32.0%), 22 (43.1%), and 24 (55.8%) for assembly with metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS, respectively. These data indicated the efficiency of metagenome binning with hybrid genome assemblies was enhanced by increasing contig length and decreasing number of contigs in each bin without introducing more contamination.

TABLE 2.

Summary of primary bins and refined bins generated.

| Primary bins | metaWRAP refine-bin | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| No. of Primary-bins | No. of contig <100 | Comp.a >50 and cont.b <10% | Comp. >95 and cont. <3% | N50 | No. refine-bins | N50 | No. of contig <100 | |

| metaSPAdes | 349 | 142 | 38 | 19 | 1,999–573,607 | 52 | 2,642–209,184 | 17 |

| HybridSPAdes | 373 | 277 | 179 | 28 | 2,728–3,008,073 | 51 | 3,163–578,001 | 22 |

| OPERA-MS | 199 | 81 | 42 | 19 | 1,024–596,353 | 53 | 4,467–3,008,073 | 23 |

aCompleteness.

bContamination.

FIGURE 5.

Binning statistics of genome assembly with different algorithms (metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS). (A) Number of genome bins with different completeness (>95%, 90–95%, and 70–95%). (B) log10 N50 of the genome bins. (C) Contamination percentages (%) of the genome bins. (D) Distribution of number of contigs in each bin. Distribution of completeness (E) and contamination (F) of metagenome bins after dereplication.

Metagenome-Assembled Genomes in the Human Gut Microbiome

Comparison and dereplication of metagenome bins generated from the four assemblies using dRep resulted in the generation of a total of 58 bins, among which 11 was from assembly with Illumina reads alone, and the remaining 47 were from binning of hybrid assemblies (14 from OPERA-MS, 33 from hybridSPAdes, Supplementary Figure 2). The percentage of genome completeness ranged from 71.3 to 100% and that of the contamination level was between 0 and 6.5% (Figure 5 and Table 3). The number of contigs in the 58 bins ranged from 7 to 689, with 37 bins (63.8%) containing contigs less than 200 contigs (Table 2). Of note, the five bins with lowest number of contigs, which ranged from 7 to 30 contigs, were generated using contigs from hybridSPAdes (4) and metaSPAdes (1). Compared with these bins, the number of contigs in metaSPAdes-assembled bins is mostly more than 50 (10/11) and there are eight bins that contain more than 90% of the contigs that were less than 100 kb. The completeness of the seven bins was >80% except for one with 77.2% completeness and contamination was <3%. Among them, three bins with less than 10 contigs at the completeness of >97% and <2% contamination were identified and the largest contigs in these three bins were all more than 0.8 Mb, indicating that hybrid metagenome assemblies prompt the generation of near-complete and high-fidelity metagenome bins.

TABLE 3.

General genomic features of all bins reconstructed from dereplication of metagenome assembly with different algorithms.

| Bin ID | No. of contig | Length (bp) | NGA50 (bp) | No. of tRNA | No. of tmRNA | No. of protein coding genes | GC content (%) | No. of rRNA | Comp.a (%) | Cont.b (%) | No. of gene annotated by COG |

| hySP11 | 269 | 1,769,144 | 10,331 | 27 | 1 | 1,599 | 0.599 | 1 | 78.9 | 6.598 | 578 |

| hySPA12 | 74 | 3,112,166 | 88,795 | 36 | 0 | 2,389 | 0.565 | 2 | 97.98 | 0.335 | 829 |

| hySPA13 | 189 | 2,663,870 | 27,772 | 30 | 1 | 2,269 | 0.36 | 0 | 97.98 | 0.167 | 807 |

| hySPA14 | 39 | 4,005,050 | 156,162 | 43 | 1 | 2,435 | 0.482 | 3 | 99.23 | 0 | 810 |

| hySP18 | 175 | 2,288,156 | 13,249 | 44 | 1 | 2,189 | 0.491 | 0 | 91.77 | 0.843 | 826 |

| hySPA20 | 655 | 2,495,082 | 20,138 | 26 | 0 | 2,247 | 0.382 | 0 | 87.07 | 1.067 | 812 |

| hySPA21 | 181 | 4,164,099 | 5,175 | 12 | 1 | 1,853 | 0.426 | 0 | 86.25 | 0.716 | 638 |

| hySPA22 | 573 | 2,504,650 | 44,101 | 43 | 1 | 2,533 | 0.507 | 0 | 83.9 | 1.901 | 754 |

| hydSPA25 | 126 | 3,292,018 | 5,617 | 26 | 0 | 2,117 | 0.415 | 1 | 84.76 | 0.019 | 761 |

| hydSPA27 | 219 | 2,376,518 | 40,640 | 32 | 1 | 2,655 | 0.563 | 0 | 97.61 | 0.68 | 936 |

| hySPA29 | 154 | 2,167,563 | 17,597 | 24 | 1 | 2,079 | 0.342 | 0 | 93.68 | 1.86 | 760 |

| hydSPA3 | 208 | 1,763,270 | 26,437 | 29 | 1 | 2,001 | 0.395 | 0 | 94.41 | 2.469 | 701 |

| hydSPA31 | 14 | 2,618,360 | 15,581 | 36 | 1 | 2,377 | 0.461 | 1 | 100 | 1.197 | 1,117 |

| hySPA32 | 149 | 2,183,825 | 342,806 | 56 | 1 | 2,431 | 0.598 | 5 | 95.96 | 0.806 | 867 |

| hySPA34 | 215 | 4,831,208 | 23,761 | 51 | 1 | 2,007 | 0.581 | 0 | 96.71 | 1.091 | 716 |

| hySPA35 | 449 | 2,306,057 | 44,008 | 61 | 0 | 6,929 | 0.423 | 11 | 80.65 | 2.013 | 2,807 |

| hySPA36 | 191 | 2,511,299 | 6,595 | 24 | 1 | 1,897 | 0.599 | 0 | 90.49 | 0.48 | 677 |

| hySPA38 | 39 | 2,727,000 | 22,674 | 29 | 1 | 1,733 | 0.614 | 0 | 98.75 | 0.621 | 588 |

| hySPA39 | 35 | 2,975,866 | 167,826 | 66 | 1 | 2,457 | 0.413 | 8 | 99.51 | 0 | 922 |

| hySPA4 | 29 | 2,522,937 | 153,428 | 29 | 1 | 2,637 | 0.576 | 0 | 98.65 | 0 | 921 |

| hySPA4 | 29 | 2,522,937 | 151,635 | 46 | 1 | 2,111 | 0.576 | 2 | 98.65 | 0 | 725 |

| hySPA41 | 138 | 1,924,037 | 23,085 | 32 | 0 | 1,913 | 0.482 | 0 | 95.13 | 0.559 | 693 |

| hySPA43 | 61 | 4,228,141 | 114,127 | 49 | 1 | 2,823 | 0.432 | 1 | 98.92 | 0 | 917 |

| hySPA44 | 205 | 1,810,309 | 15,099 | 27 | 0 | 1,725 | 0.613 | 1 | 87.63 | 3.02 | 600 |

| hySP46 | 391 | 2,211,788 | 7,930 | 9 | 0 | 2,209 | 0.289 | 0 | 88.52 | 0 | 796 |

| hySP47 | 59 | 2,309,764 | 70,537 | 44 | 1 | 2,083 | 0.582 | 3 | 94.47 | 0 | 741 |

| hySPA48 | 116 | 4,882,463 | 183,297 | 37 | 1 | 2,639 | 0.422 | 2 | 82.44 | 2.944 | 820 |

| hySPA5 | 250 | 4,227,969 | 26,976 | 41 | 0 | 6,183 | 0.511 | 6 | 92.44 | 0.453 | 2,585 |

| hySPA50 | 85 | 2,430,178 | 53,327 | 41 | 1 | 1,983 | 0.41 | 4 | 98.99 | 1.006 | 680 |

| hySPA51 | 445 | 2,294,131 | 6,300 | 14 | 0 | 2,115 | 0.469 | 0 | 78.61 | 5.37 | 771 |

| hySPA6 | 183 | 2,552,049 | 21,470 | 23 | 0 | 2,273 | 0.504 | 0 | 90.31 | 0.41 | 811 |

| hySPA7 | 7 | 1,834,142 | 578,001 | 47 | 1 | 1,823 | 0.366 | 7 | 98.65 | 0 | 642 |

| hySPA8 | 411 | 1,976,503 | 6,078 | 27 | 0 | 1,887 | 0.343 | 0 | 79.09 | 2.322 | 664 |

| SPAd1 | 87 | 4,165,019 | 103,305 | 37 | 1 | 2,721 | 0.461 | 0 | 96.42 | 0.247 | 862 |

| mSPA14 | 125 | 1,902,876 | 78,191 | 38 | 1 | 1,765 | 0.591 | 0 | 84.6 | 5.668 | 625 |

| mSPA15 | 75 | 3,257,610 | 7,534 | 35 | 1 | 2,441 | 0.365 | 0 | 98.65 | 0 | 817 |

| mSPA.20 | 363 | 2,188,068 | 38,734 | 17 | 0 | 1,739 | 0.448 | 0 | 77.24 | 0.393 | 605 |

| mSPA21 | 132 | 2,878,203 | 115,100 | 40 | 1 | 1,999 | 0.596 | 1 | 99.18 | 0.24 | 664 |

| mSPA36 | 25 | 2,146,454 | 23,934 | 43 | 1 | 1,731 | 0.545 | 0 | 99.51 | 0.961 | 606 |

| mSPA38 | 243 | 3,152,086 | 25,918 | 31 | 1 | 2,617 | 0.419 | 0 | 91.69 | 1.011 | 935 |

| mSPA40 | 236 | 3,782,419 | 57,354 | 33 | 0 | 2,549 | 0.456 | 0 | 91.74 | 1.794 | 837 |

| mSPA44 | 80 | 3,137,080 | 119,525 | 29 | 1 | 2,731 | 0.417 | 0 | 97.58 | 0.483 | 941 |

| mSPA.46 | 51 | 3,299,494 | 44,325 | 43 | 1 | 2,153 | 0.454 | 0 | 98.51 | 0.277 | 704 |

| mSPA47 | 94 | 2,771,004 | 21,825 | 10 | 0 | 2,023 | 0.455 | 0 | 79.11 | 0 | 678 |

| Op1 | 200 | 2,317,819 | 374,219 | 32 | 1 | 2,075 | 0.563 | 1 | 96.54 | 0.68 | 737 |

| Op2 | 202 | 2,492,862 | 844,209 | 49 | 1 | 2,273 | 0.599 | 10 | 89.5 | 0.48 | 824 |

| Op24 | 504 | 2,071,756 | 55,129 | 68 | 1 | 3,279 | 0.595 | 15 | 71.31 | 1.469 | 1,043 |

| Op26 | 570 | 1,872,933 | 14,003 | 59 | 1 | 2,467 | 0.503 | 2 | 71.57 | 3.601 | 864 |

| Op29 | 71 | 2,743,675 | 856,673 | 42 | 1 | 2,295 | 0.487 | 9 | 99.05 | 0.632 | 1,080 |

| Op3 | 689 | 2,530,979 | 306,231 | 49 | 0 | 2,475 | 0.286 | 11 | 75.43 | 0 | 823 |

| Op30 | 115 | 3,184,703 | 204,798 | 50 | 1 | 2,159 | 0.418 | 2 | 92.63 | 0.672 | 756 |

| Op31 | 71 | 2,135,893 | 1,541,592 | 38 | 0 | 1,837 | 0.406 | 8 | 98.99 | 1.006 | 641 |

| Op34 | 40 | 3,825,506 | 2,482,255 | 39 | 1 | 2,873 | 0.482 | 8 | 98.51 | 0 | 880 |

| Op35 | 232 | 1,706,406 | 609,88 | 58 | 0 | 3,031 | 0.395 | 17 | 84.36 | 3.337 | 941 |

| Op39 | 205 | 8,306,390 | 296,992 | 28 | 1 | 1,675 | 0.415 | 6 | 74.29 | 6.45 | 594 |

| Op41 | 170 | 2,138,655 | 231,829 | 51 | 1 | 2,895 | 0.599 | 7 | 95.16 | 0.806 | 1,038 |

| Op42 | 181 | 2,133,167 | 562,214 | 39 | 0 | 6,821 | 0.343 | 17 | 89.5 | 1.069 | 2,864 |

| Op43 | 32 | 2,582,353 | 42 | 1 | 1,839 | 0.462 | 4 | 99.85 | 1.197 | 596 |

aCompleteness.

bContamination. Op, OPERA-MS; mSPA, metaSPAdes; hySPA, hybridSPAdes.

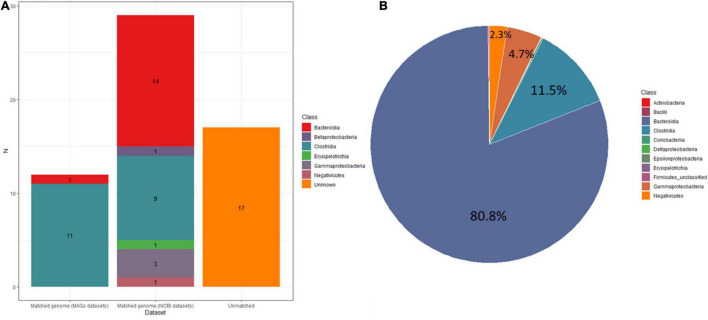

To determine how many of the MAGs belong to species that have been isolated from pure bacterial cultures (i.e., isolate genomes), we attempted to assign these MAGs to all bacteria references of NCBI datasets (RefSeq database) and 2,110 isolate genomes (HR database) combined from HMP and HGG (Forster et al., 2019). In addition, we also compared the 58 MAGs to a set of 92,143 MAGs from 11,850 human gut metagenome (Almeida et al., 2019), including 1,952 unclassified bacterial MAGs (UMGs). Of the 58 MAGs, we were able to assign 29 MAGs and 12 MAGs to the HR and UMGs dataset, respectively, using a criterion of at least 60% of aligned fragment (AF) with at least 95% ANI. Among the 29 MAGs, there were two most frequent genomes assigned to the class (Bacteroidia n = 14, Clostridia n = 9). All are known colonizers of the human gut, confirming that these species are common members of the intestinal microbiota (Figures 6, 7A and Supplementary File 4). In addition, it was consistent with the microbiome abundance obtained from metagenomic analysis (Figure 7B). Meanwhile, twelve MAGs matched to the UMGs dataset were Clostridia (n = 11) and Bacteroidia (n = 1). However, there still were 17 MAGs that were not matched in these two datasets, while they were clustered by GTDB-Tk into Firmicutes (n = 14), Bacteroidota (n = 1), Proteobacteria (n = 1), and Actinobacteriota (n = 1) (Figures 6, 7 and Supplementary File 4). This indicated our workflow has a positive effort in researching unclassified bacterial.

FIGURE 6.

Phylogeny of the genome bins reconstructed from dereplication of metagenome assembly with different algorithms. Phylum of the strains and assemblers are plotted in the figure.

FIGURE 7.

(A) Stacked bar plots showing the number of MAGs matched in UMGS and HR datasets or unknown. (B) Pie figure showing relative abundance of the gut microbiota. The different colors represent different bacteria at class level.

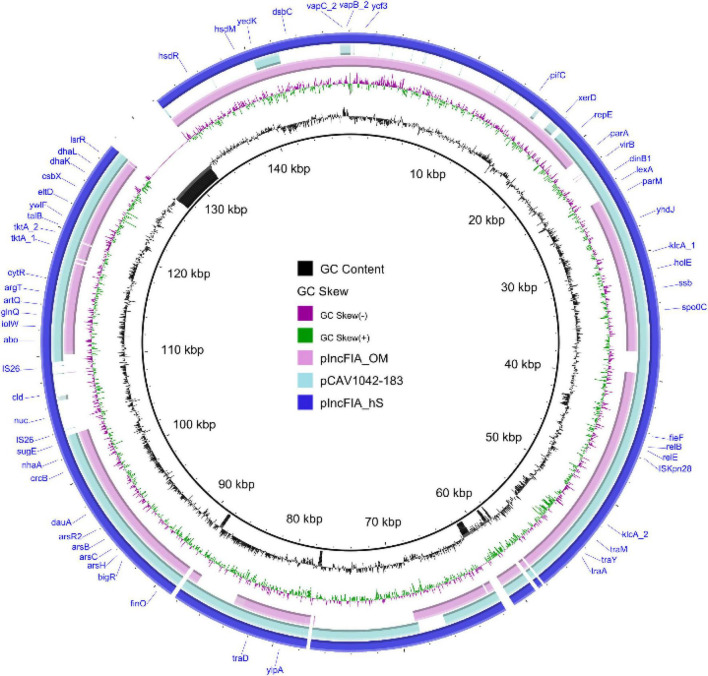

Plasmids and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Human Microbiome

Plasmids are major genome contents of bacteria, which normally carry genes that benefit the survival of the organism, such as the antimicrobial resistance genes. Due to the carriage of large numbers of Insertion Sequences in MDR plasmids, short-read Illumina sequencing become challenging in getting complete MDR plasmid sequences. To compare the plasmid contents resolved by different assembly algorithms, contigs carrying the plasmid replicons were extracted. A total of 32.5% (38,570/118,507) and 29.3% (39,433/134,361) contigs generated by hybridSPAdes and OPERA-MS were identified as chromosomal-related contigs that were clustered into the phylum level, respectively. The chromosomal data for contigs from Flye and metaSPAdes assemblers were 79.0% (1556/1968) and 31.2% (47,034/150,470), respectively. The number of plasmid (>10 kbp) assembled by Flye, metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS were 65, 129, 174, and 164, respectively (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 3). Plasmid replicons identified in assemblies metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS were highly consistent, with a few replicons identified only in hybrid assemblies (hybridSPAdes and OPERA-MS) (Supplementary File 2). The largest plasmid contig identified in assembly with Flye, metaSPAdes, OPERA-MS, and hybridSPAdes were 145,633, 162,508, 229,251, and 214,848 bp, respectively (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 4). The alignment of the 214,848 bp plasmid and the contigs from metaSPAdes assembly could be seen in Supplementary Figure 3. The top 10 longest plasmids generated by the four programs are also shown in Supplementary Table 4. Contigs (152,484 bp, hybridSPAdes) pIncFIA_hS and (157,875 bp, OPERA-MS) pIncFIA_OM were both complete plasmid sequences that belonged to IncFIA plasmids and shared 99.95% identity at 79% coverage. pIncFIA_hS and pIncFIA_OM were novel plasmids, which exhibited 99.9% identity to plasmid pCAV1042_183 (GenBank accession: CP018670) at 69 and 63% coverage, respectively (Figure 8 and Supplementary Table 4). We identified 5, 17, 27, and 29 different antimicrobial resistance genes with Flye, metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS assemblies, respectively (Supplementary Table 5). At least 10 genes, including floR, sul1, and sul2, assembled with hybrid algorithms were missing in assembly with single read types. Additionally, contigs carrying AMR genes were identified in 2, 2, 5, and 4 contigs from Flye, metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS assemblers, respectively (Supplementary File 2). Importantly, hybrid assembly methods (hybridSPAdes and OPERA-MS) enabled us to obtain more contigs/plasmids carrying AMR genes compared to single assembly methods (Flye and metaSPAdes) (Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 6). These findings indicated the advantage of hybrid assembly in AMR-related research, including completed plasmid and mobile element sequences.

TABLE 4.

Summary of chromosomal and plasmids contigs.

| Chromosomal-contig | No. of plasmid (>10 Kbp) | Largest plasmid contig | |

| metaSPAdes | 31.20% | 129 | 162,508 bp |

| HybridSPAdes | 32.50% | 174 | 214,848 bp |

| OPERA-MS | 29.30% | 164 | 229,251 bp |

| Flye | 79.00% | 65 | 145,633 bp |

FIGURE 8.

Map of the largest observed new completed circular plasmid sequence using hybrid assembly methods, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS. Plasmids pIncFIA_hS, pIncFIA_OM, and pCAV1042_183 are plotted in the figure using the sequence of pIncFIA_hS as a reference.

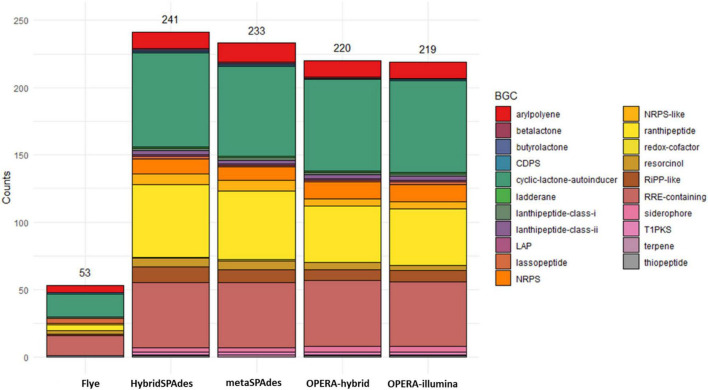

Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Prediction

The genome contiguity, completeness, and accuracy have significant effect on gene prediction. Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) are especially influenced by these factors since they are usually found in repetitive regions that are often poorly assembled. AntiSMASH was used to assess the number of clusters found in the draft assemblies in comparison to the reference metagenome with the aim of evaluating BGC prediction on metagenomic assemblies (Figure 9). The number of BGCs recovered by hybrid assemblers (OPERA-MS and HybridSPAdes) is higher than that of metaSPAdes. HybridSPAdes assembler improves the number of BGCs recovered. Meanwhile, the analysis of two MAGs’ BGC shows that one MAG assembled by HybridSPAdes carried one more BGC cluster named resorcinol compared with (99.7% similarity) one MAG assembled by metaSPAdes (Supplementary Figure 7). These findings indicated that the higher completeness MAGs assembled by hybrid assembler have positive effect on the downstream analysis.

FIGURE 9.

Number of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) predicted by antiSMASH for each draft assembly.

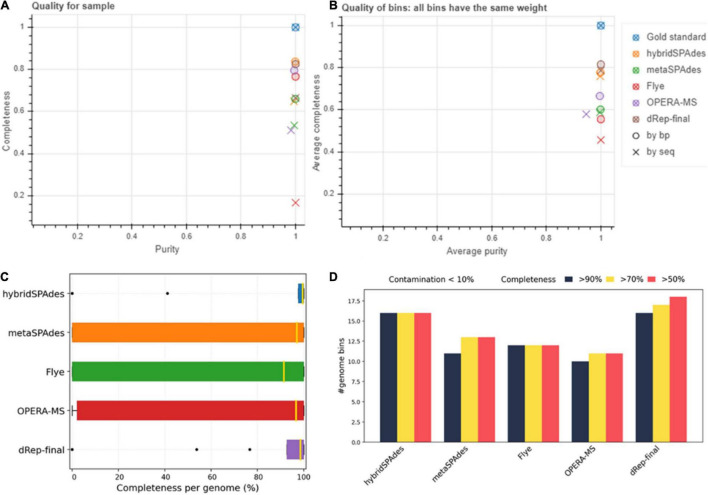

The BMS21 Mock Community Datasets

Mock community standards are essential for the validation of metagenome-related bioinformatics approaches, and the development of genomics methods (Nicholls et al., 2019). To validate the results of human gut metagenome, we constructed a mock community named BMS21 from a low-complexity microbial community with 21 bacterial genomes (accounted for 0.01–30%) (Supplementary Table 12), for which the ground truth was known, and evaluated its assembly datasets. A total of 61 Gb 2 × 150 bp high-quality pair-end Illumina sequencing data and 18.6 Gb base-called nanopore reads were generated for the BMS21 mock community. Assembly with algorithms Flye, metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS resulted in generation of a metagenome size of 71, 94, 95, and 93 Mb with N50 of 4,185,707, 93,165, 209,776, and 385,369 bp, respectively (Supplementary Table 7). The numbers of contigs assembled with each method were 229, 2,999, 1,812, and 2,521, with the size of the longest contig being 6,834,171, 670,411, 2,247,228, and 6,176,973 bp, respectively. The BMS21 benchmark results are shown in Supplementary File 3. Flye had the highest NGA50s for 18 bacterial genomes. The number of misassemblies and misassembled contigs length was markedly smaller in hybridSPAdes than other tools, suggesting the high accuracy of its core regions were constructed from short and long reads. HybridSPAdes assembler has a higher genome fraction for each reference genome than other assemblers, whereas Flye and OPERA-MS have a higher duplication ratio. The numbers of plasmids were 15 (metaSPAdes) and 16 (hybridSPAdes) (Supplementary Table 14). The assembly statistics of the mock community supported the finding that hybrid metagenome assembly with both nanopore long- and Illumina short reads could efficiently increase assembly contiguity, and that hybridSPAdes performs better than OPERA-MS in terms of accuracy.

Genome binning and refinement of the BMS21 mock community assembled using different software resulted in generation a total of 49 bins, including 9, 13, 16, and 11 from Flye, metaSPAdes, hybridSPAdes, and OPERA-MS assemblies, respectively (Supplementary Table 9). Binning results with the HybridSPAdes assembly algorithm were closest to the actual number of strains in the mock community, which was 21. However, dereplication (dRep) of metagenome bins from different assembly methods resulted in the generation of a total of 18 final bins (hybridSPAdes 16, metaSPAdes 4, and OPERA-MS 2). A gold standard mapping shows that MAGs generated by Flye and dRep achieved the highest purity per bin, and by dRep and hybridSPAdes achieved the highest completeness per genome on this dataset (Figures 10A,B). MAGs generated by dRep recovered the most genomes with the specified thresholds of completeness and contamination on this dataset (Figures 10C,D and Table 5). The completeness of the 18 bins ranged from 75.86 to 100%, with the majority (n = 16, 83%) being more than 95%. The contamination level of these bins ranged from 0 to 5.17%. The number of contigs in the 18 bins ranged from 6 to 205, with 6 (33.3%) bins containing no more than 30 contigs at more than 99.5% completeness. The abundance of the five bins was from 0.1 to 30%, which represented a majority genome content of the mock community (Supplementary Figure 5 and Supplementary Tables 10–12). ANI between metagenome bins and the individually assembled genomes ranged from 81.6 to 99.98%, with the majority (n = 15, 83.3%) being more than 99%. SNP of metagenome ranged from 11 to 81,540, with 7 bins (38.8%) exhibiting less than 100 SNPs compared to the reference genomes. Genome sequences of three strains in the mock community were not resolved with the algorithms, with the abundance of each genome being 0.10 and 0.25% (Supplementary Table 12), respectively. Findings here indicated the potential of hybrid genome assembly to resolve the near-complete and high-fidelity metagenome bins, and our workflow could generate more and higher quality MAGs, but there is still room for improvement of such algorithms in terms of assembly and binning accuracy.

FIGURE 10.

Assessment of genome bins reconstructed from mock community (BMS21) dataset by different methods. (A) Purity (x-axis) and completeness (y-axis). (B) Average purity per base pair (x-axis) and average completeness per base pair (y-axis). (C) Box plots of purity per bin and completeness per genome, respectively. (D) Number of genomes with less than 10 and 5% contamination and more than 50, 70, and 90% completeness.

TABLE 5.

Respective numbers of genomes recovered from mock community (BMS21) dataset with less than 10 and 5% contamination and more than 50, 70, and 90% completeness.

| Tool | Contamination | >50% completeness | >70% completeness | >90% completeness |

| Gold standard | <10% | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Gold standard | <5% | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| dRep | <10% | 18 | 17 | 16 |

| dRep | <5% | 18 | 17 | 16 |

| Flye | <10% | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Flye | <5% | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| hybridSPAdes | <10% | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| hybridSPAdes | <5% | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| metaSPAdes | <10% | 13 | 13 | 11 |

| metaSPAdes | <5% | 13 | 13 | 11 |

| OPERA-MS | <10% | 11 | 11 | 10 |

| OPERA-MS | <5% | 11 | 11 | 10 |

Discussion

The human gut microbiota is one of the most studied microbial environments, but technical and practical constraints hinder our ability to isolate and sequence every constituent species (Almeida et al., 2019). Currently, short-read sequencing is still one of the most cost-effective approaches to study complex microbial communities. Long-read sequencing methods (PacBio and Oxford nanopore), which have been widely applied in the study of single bacteria genomes, were gradually applied in metagenome studies (Loman et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2022). To our knowledge, although research groups have applied the third-generation long-read sequencing in metagenome-related studies (Frank et al., 2016; Tsai et al., 2016; Driscoll et al., 2017; Kerkhof et al., 2017; Bertrand et al., 2019; Overholt et al., 2020), the feasibility of nanopore sequencing in metagenomic studies remains to be unveiled, and the methods of assembling MAGs depending on a HiSeq-Nanopore hybrid metagenomic approach need to improve.

Mock communities, which represent simpler communities compared to the natural ones, are commonly recognized as a gold standard (Meyer et al., 2021) for evaluating metagenomic assemblies (Bertrand et al., 2019). By applying the workflow from metagenomic DNA analysis to generation of finally assembled bins in both natural healthy human gut microbiota and mock community, this study demonstrated the advantage of hybrid assembly with both short- and long-sequencing reads in both complex and simplified communities and the better performance of our workflow.

Specific benefits of analyzing nanopore contigs were the considerably larger average contig sizes as well as the number of large contigs, with the latter being comparable to the HiSeq assembly that was generated from tens to hundreds of folds of data. In metagenomic analyses, larger contigs are key to producing higher quality output that is needed for downstream applications such as taxonomic assignments (Patil et al., 2011; Ciuffreda et al., 2021), gene calling, annotation of operons (often exceed 10 kb in length), or detection of structural variation (Pope et al., 2010). The assembly output from both platforms varied considerably in both contig size and distribution (Figures 2, 3). Despite the similar size of the hybrid assembly and Illumina assembly contigs >0.5 kb contig datasets available for binning, the contig size of bins obtained from the Nanopore sequencing data were, on average, ∼3× to ∼6× larger, respectively (Figure 5). Another observation was the examples of hybrid contigs containing difficult to assemble regions. Hence, this approach presents an alternative means to reconstruct genomes in cases where phylotypes are not conducive to Illumina assembly alone and experimental design that cannot handle multiple sample timepoints or several differential DNA extractions, which are necessary for accurate binning algorithms that use differential coverage of populations (Alneberg et al., 2014; Imelfort et al., 2014).

This study shows the potential value that nanopore long-sequencing reads can exert upon a metagenomic study, although there is certain room for improvement. The comparative high cost of nanopore data restricts the sequencing depth of raw data used. Moreover, a major concern with the usage of nanopore reads is data wastage with respect to the number that passes the quality cutoffs. Increasing read quality and cost reductions would benefit its future applications.

We presented human gut microbiome co-assembled with Illumina short reads and nanopore long reads. Hybrid metagenome assembly resulted in a significant increase in contig length and accuracy, as well as enhancement in efficiency of taxonomic binning and genome construction compared with that using Illumina short-read data alone. OPERA-MS performs well on contig contiguity and hybridSPAdes was good at accuracy. Using our workflow, 58 high-quality metagenome bins were successfully obtained from the gut microbiota of a healthy young man, and 29 of them were currently uncultured bacteria. In summary, this study generated the high-resolution human metagenome, which could serve as a reference to improve the quality and comprehensiveness of future human metagenomics studies. Findings in this study show that nanopore long reads are highly valuable in metagenomic applications.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the Local Legislation and Institutional Requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

LY and ND designed and performed the experiment and data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. WX, RL, HH, and JL helped with data analysis. EC edited the manuscript. SC supervised the whole project and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

Funding

This study was supported by the Hong Kong Branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory, Guangzhou, China (SMSEGL20SC02).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.801587/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aagaard K., Petrosino J., Keitel W., Watson M., Katancik J., Garcia N., et al. (2013). The Human Microbiome Project strategy for comprehensive sampling of the human microbiome and why it matters. FASEB J. 27 1012–1022. 10.1096/fj.12-220806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhan N.-F., Petty N. K., Zakour N. L. B., Beatson S. A. (2011). BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics 12:402. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida A., Mitchell A. L., Boland M., Forster S. C., Gloor G. B., Tarkowska A., et al. (2019). A new genomic blueprint of the human gut microbiota. Nature 568 499–504. 10.1038/s41586-019-0965-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alneberg J., Bjarnason B. S., De Bruijn I., Schirmer M., Quick J., Ijaz U. Z., et al. (2014). Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat. Methods 11:1144. 10.1038/nmeth.3103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antipov D., Korobeynikov A., Mclean J. S., Pevzner P. A. (2015). hybridSPAdes: an algorithm for hybrid assembly of short and long reads. Bioinformatics 32 1009–1015. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D., Shaw J., Kalathiyappan M., Ng A. H. Q., Kumar M. S., Li C., et al. (2019). Hybrid metagenomic assembly enables high-resolution analysis of resistance determinants and mobile elements in human microbiomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 37 937–944. 10.1038/s41587-019-0191-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D., Shaw J., Narayan M., Ng H. Q. A., Kumar S., Li C., et al. (2018). Nanopore sequencing enables high-resolution analysis of resistance determinants and mobile elements in the human gut microbiome. bioRxiv [preprint] 10.1101/456905 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser M., Bork P., Fraser C., Knight R., Wang J. J. (2013). The microbiome explored: recent insights and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11:213. 10.1038/nrmicro2973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleidorn C. (2016). Third generation sequencing: technology and its potential impact on evolutionary biodiversity research. Systemat. Biodiversity 14 1–8. 10.1080/14772000.2015.1099575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A., Zankari E., García-Fernández A., Larsen M. V., Lund O., Villa L., et al. (2014). In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 3895–3903. 10.1128/AAC.02412-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumeil P.-A., Mussig A. J., Hugenholtz P., Parks D. H. (2020). GTDB-Tk: a Toolkit to Classify Genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I., Blaser M. J. (2012). The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13:260. 10.1038/nrg3182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciuffreda L., Rodríguez-Pérez H., Flores C. (2021). Nanopore sequencing and its application to the study of microbial communities. Comp. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19 1497–1511. 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J. R., Chai B., Farris R. J., Wang Q., Kulam-Syed-Mohideen A., Mcgarrell D. M., et al. (2006). The ribosomal database project (RDP-II): introducing myRDP space and quality controlled public data. Nucleic Acids Res. 35 D169–D172. 10.1093/nar/gkl889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding T., Schloss P. D. (2014). Dynamics and associations of microbial community types across the human body. Nature 509:357. 10.1038/nature13178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll C. B., Otten T. G., Brown N. M., Dreher T. W. (2017). Towards long-read metagenomics: complete assembly of three novel genomes from bacteria dependent on a diazotrophic cyanobacterium in a freshwater lake co-culture. Stand. Genom. Sci. 12:9. 10.1186/s40793-017-0224-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckburg P. B., Bik E. M., Bernstein C. N., Purdom E., Dethlefsen L., Sargent M., et al. (2005). Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308 1635–1638. 10.1126/science.1110591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster S. C., Kumar N., Anonye B. O., Almeida A., Viciani E., Stares M. D., et al. (2019). A human gut bacterial genome and culture collection for improved metagenomic analyses. Nat. Biotechnol. 37 186–192. 10.1038/s41587-018-0009-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J. A., Pan Y., Tooming-Klunderud A., Eijsink V. G., Mchardy A. C., Nederbragt A. J., et al. (2016). Improved metagenome assemblies and taxonomic binning using long-read circular consensus sequence data. Sci. Rep. 6:25373. 10.1038/srep25373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller C. W., Middendorf L. R., Benner S. A., Church G. M., Harris T., Huang X., et al. (2009). The challenges of sequencing by synthesis. Nat. Biotechnol. 27:1013. 10.1038/nbt.1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenhower C., Gevers D., Knight R., Abubucker S., Badger J. H., Chinwalla A. T., et al. (2012). Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486:207. 10.1038/nature11234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imelfort M., Parks D., Woodcroft B. J., Dennis P., Hugenholtz P., Tyson G. W. (2014). GroopM: an automated tool for the recovery of population genomes from related metagenomes. PeerJ 2:e603. 10.7717/peerj.603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Integrative H., Proctor L. M., Creasy H. H., Fettweis J. M., Lloyd-Price J., Mahurkar A., et al. (2019). The integrative human microbiome project. Nature 569 641–648. 10.1038/s41586-019-1238-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain C., Rodriguez-R L. M., Phillippy A. M., Konstantinidis K. T., Aluru S. (2018a). High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9:5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M., Koren S., Miga K. H., Quick J., Rand A. C., Sasani T. A., et al. (2018b). Nanopore sequencing and assembly of a human genome with ultra-long reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 36:338. 10.1038/nbt.4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H., You L., Zhao F., Li S., Ma T., Kwok L.-Y., et al. (2022). Hybrid, ultra-deep metagenomic sequencing enables genomic and functional characterization of low-abundance species in the human gut microbiome. Gut Microbes 14:2021790. 10.1080/19490976.2021.2021790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D. D., Froula J., Egan R., Wang Z. (2015). MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. PeerJ 3:e1165. 10.7717/peerj.1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhof L. J., Dillon K. P., Häggblom M. M., Mcguinness L. R. (2017). Profiling bacterial communities by MinION sequencing of ribosomal operons. Microbiome 5:116. 10.1186/s40168-017-0336-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov M., Bickhart D. M., Behsaz B., Gurevich A., Rayko M., Shin S. B., et al. (2020). metaFlye: scalable long-read metagenome assembly using repeat graphs. Nat. Methods 17 1103–1110. 10.1038/s41592-020-00971-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren S., Walenz B. P., Berlin K., Miller J. R., Bergman N. H., Phillippy A. M. (2017). Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27 722–736. 10.1101/gr.215087.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk P. S., Lipinski L., Dziembowski A. (2018). PlasFlow: predicting plasmid sequences in metagenomic data using genome signatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 46:e35. 10.1093/nar/gkx1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9:357. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I., Kim Y. O., Park S.-C., Chun J. J. (2016). OrthoANI: an improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66 1100–1103. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Bork P. (2016). Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 W242–W245. 10.1093/nar/gkw290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., et al. (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Xie M., Dong N., Lin D., Yang X., Wong M. H. Y., et al. (2018). Efficient generation of complete sequences of MDR-encoding plasmids by rapid assembly of MinION barcoding sequencing data. Gigascience 7:gix132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Jin Y., Zhang J., Pan H., Wu L., Liu D., et al. (2021). Recovery of human gut microbiota genomes with third-generation sequencing. Cell Death Dis. 12:569. 10.1038/s41419-021-03829-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Price J., Abu-Ali G., Huttenhower C. (2016). The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 8:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman N. J., Quick J., Simpson J. T. (2015). A complete bacterial genome assembled de novo using only nanopore sequencing data. Nat. Methods 12:733. 10.1038/nmeth.3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z. S., Li L., Ye C., Peng M., Zhang Y.-P. (2018). Hybrid assembly of ultra-long nanopore reads augmented with 10×-genomics contigs: demonstrated with a human genome. Genomics 111 1896–1901. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2018.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mende D. R., Sunagawa S., Zeller G., Bork P. (2013). Accurate and universal delineation of prokaryotic species. Nat. Methods 10:881. 10.1038/nmeth.2575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methé B. A., Nelson K. E., Pop M., Creasy H. H., Giglio M. G., Huttenhower C., et al. (2012). A framework for human microbiome research. Nature 486 215–212. 10.1038/nature11209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer F., Hofmann P., Belmann P., Garrido-Oter R., Fritz A., Sczyrba A., et al. (2018). AMBER: assessment of metagenome BinnERs. Gigascience 7:giy069. 10.1093/gigascience/giy069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer F., Lesker T.-R., Koslicki D., Fritz A., Gurevich A., Darling A. E., et al. (2021). Tutorial: assessing metagenomics software with the CAMI benchmarking toolkit. Nat. Protocols 16 1785–1801. 10.1038/s41596-020-00480-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikheenko A., Saveliev V., Gurevich A. (2015). MetaQUAST: evaluation of metagenome assemblies. Bioinformatics 32 1088–1090. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostovoy Y., Levy-Sakin M., Lam J., Lam E. T., Hastie A. R., Marks P., et al. (2016). A hybrid approach for de novo human genome sequence assembly and phasing. Nat. Methods 13:587. 10.1038/nmeth.3865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S., Seshadri R., Varghese N. J., Eloe-Fadrosh E. A., Meier-Kolthoff J. P., Göker M., et al. (2017). 1,003 reference genomes of bacterial and archaeal isolates expand coverage of the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 35:676. 10.1038/nbt.3886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls S. M., Quick J. C., Tang S., Loman N. J. (2019). Ultra-deep, long-read nanopore sequencing of mock microbial community standards. Gigascience 8:giz043. 10.1093/gigascience/giz043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurk S., Meleshko D., Korobeynikov A., Pevzner P. A. (2017). metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 27 824–834. 10.1101/gr.213959.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olm M. R., Brown C. T., Brooks B., Banfield J. F. (2017). dRep: a tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 11:2864. 10.1038/ismej.2017.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R., Olson R., Pusch G. D., Olsen G. J., Davis J. J., Disz T., et al. (2013). The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 42 D206–D214. 10.1093/nar/gkt1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overholt W. A., Hölzer M., Geesink P., Diezel C., Marz M., Küsel K. (2020). Inclusion of Oxford Nanopore long reads improves all microbial and viral metagenome-assembled genomes from a complex aquifer system. Environ. Microbiol. 22 4000–4013. 10.1111/1462-2920.15186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyewusi H. A., Abdul Wahab R., Edbeib M. F., Mohamad M. A. N., Abdul Hamid A. A., Kaya Y., et al. (2021). Functional profiling of bacterial communities in Lake Tuz using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equipment 35 1–10. 10.1080/13102818.2020.1840437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parks D. H., Imelfort M., Skennerton C. T., Hugenholtz P., Tyson G. W. (2015). CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25 1043–1055. 10.1101/gr.186072.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks D. H., Rinke C., Chuvochina M., Chaumeil P.-A., Woodcroft B. J., Evans P. N., et al. (2017). Recovery of nearly 8,000 metagenome-assembled genomes substantially expands the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol. 2:1533. 10.1038/s41564-017-0012-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasolli E., Asnicar F., Manara S., Zolfo M., Karcher N., Armanini F., et al. (2019). Extensive unexplored human microbiome diversity revealed by over 150,000 genomes from metagenomes spanning age, geography, and lifestyle. Cell 176 649–662.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil K. R., Haider P., Pope P. B., Turnbaugh P. J., Morrison M., Scheffer T., et al. (2011). Taxonomic metagenome sequence assignment with structured output models. Nat. Methods 8:191. 10.1038/nmeth0311-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson D., Bonham K. S., Rowland S., Pattanayak C. W., Klepac-Ceraj V. (2021). Comparative analysis of 16S rRNA gene and metagenome sequencing in pediatric gut microbiomes. Front. Microbiol. 12:670336. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.670336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope P., Denman S., Jones M., Tringe S., Barry K., Malfatti S., et al. (2010). Adaptation to herbivory by the Tammar wallaby includes bacterial and glycoside hydrolase profiles different from other herbivores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107 14793–14798. 10.1073/pnas.1005297107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quince C., Walker A. W., Simpson J. T., Loman N. J., Segata N. (2017). Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 35:833. 10.1038/nbt.3935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z., Cui G., Lu H., Chen X., Jiang J., Liu H., et al. (2013). Liver ischemic preconditioning (IPC) improves intestinal microbiota following liver transplantation in rats through 16s rDNA-based analysis of microbial structure shift. PLoS One 8:e75950. 10.1371/journal.pone.0075950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2015). Snippy: fast Bacterial Variant Calling from NGS Reads. San Francisco, CA: Github. [Google Scholar]

- Shendure J., Ji H. (2008). Next-generation DNA sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 26:1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siguier P., Pérochon J., Lestrade L., Mahillon J., Chandler M. J. (2006). ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 D32–D36. 10.1093/nar/gkj014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol H., Seksik P. J. (2010). The intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases: time to connect with the host. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 26 327–331. 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328339536b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2014). RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30 1312–1313. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suau A., Bonnet R., Sutren M., Godon J.-J., Gibson G. R., Collins M. D., et al. (1999). Direct analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA from complex communities reveals many novel molecular species within the human gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 4799–4807. 10.1128/AEM.65.11.4799-4807.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A. H., Chong C. W., Lim S. Y., Yap I. K. S., Teh C. S. J., Loke M. F., et al. (2021). Gut microbial ecosystem in Parkinson disease: new clinicobiological insights from multi-omics. Ann. Neurol. 89 546–559. 10.1002/ana.25982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannock G. W. (2001). Molecular assessment of intestinal microflora. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 73 410s–414s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringe S. G., Von Mering C., Kobayashi A., Salamov A. A., Chen K., Chang H. W., et al. (2005). Comparative metagenomics of microbial communities. Science 308 554–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong D. T., Franzosa E. A., Tickle T. L., Scholz M., Weingart G., Pasolli E., et al. (2015). MetaPhlAn2 for enhanced metagenomic taxonomic profiling. Nat. Methods 12:902. 10.1038/nmeth.3589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong D. T., Tett A., Pasolli E., Huttenhower C., Segata N. (2017). Microbial strain-level population structure and genetic diversity from metagenomes. Genome Res. 27 626–638. 10.1101/gr.216242.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y.-C., Conlan S., Deming C., Segre J. A., Kong H. H., Korlach J., et al. (2016). Resolving the complexity of human skin metagenomes using single-molecule sequencing. mBio 7:e01948-15. 10.1128/mBio.01948-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Ley R. E., Hamady M., Fraser-Liggett C. M., Knight R., Gordon J. I. (2007). The human microbiome project. Nature 449 804–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyakht A. V., Kostryukova E. S., Popenko A. S., Belenikin M. S., Pavlenko A. V., Larin A. K., et al. (2013). Human gut microbiota community structures in urban and rural populations in Russia. Nat. Commun. 4:2469. 10.1038/ncomms3469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson G. W., Chapman J., Hugenholtz P., Allen E. E., Ram R. J., Richardson P. M., et al. (2004). Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature 428:37. 10.1038/nature02340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uritskiy G. V., Diruggiero J., Taylor J. (2018). MetaWRAP—a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome 6:158. 10.1186/s40168-018-0541-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter J. C., Remington K., Heidelberg J. F., Halpern A. L., Rusch D., Eisen J. A., et al. (2004). Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science 304 66–74. 10.1126/science.1093857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Qing Y., Zhou H., Liu J., Qi C., Gao J. (2022). 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing of gut microbiota in gestational diabetes mellitus and their correlation with disease risk factors. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 45 279–289. 10.1007/s40618-021-01595-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick R. R., Judd L. M., Gorrie C. L., Holt K. E. (2017). Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comp. Biol. 13:e1005595. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese C. R., Fox G. E. (1977). Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 74 5088–5090. 10.1073/pnas.74.11.5088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.-W., Simmons B. A., Singer S. W. (2015). MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 32 605–607. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., et al. (2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 67 2640–2644. 10.1093/jac/dks261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y., Xu F., Wu J., Schubert J., Li M. M. (2021). Application of next generation sequencing in laboratory medicine. Ann. Lab. Med. 41 25–43. 10.3343/alm.2021.41.1.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y., Xue W., Luo G., Deng Z., Qin P., Guo R., et al. (2019). 1,520 reference genomes from cultivated human gut bacteria enable functional microbiome analyses. Nat. Biotechnol. 37:179. 10.1038/s41587-018-0008-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.