Abstract

We present a cost-effective means of 2H and 13C enrichment of cholesterol. This method exploits the metabolism of 2H,13C-acetate into acetyl-CoA, the first substrate in the mevalonate pathway. We show that growing the cholesterol producing strain RH6827 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in 2H,13C-acetate-enriched minimal media produces a skip-labeled pattern of deuteration. We characterize this cholesterol labeling pattern by mass spectrometry and solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. It is confirmed that most 2H nuclei retain their original 2H–13C bonds from acetate throughout the biosynthetic pathway. We then quantify the changes in 13C chemical shifts brought by deuteration and the impact upon 13C–13C spin diffusion. Finally, using adiabatic rotor echo short pulse irradiation cross-polarization (RESPIRATIONCP), we acquire the 2H–13C correlation spectra to site specifically quantify cholesterol dynamics in two model membranes as a function of temperature. These measurements show that cholesterol acyl chains at physiological temperatures in mixtures of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC), sphingomyelin, and cholesterol are more dynamic than cholesterol in POPC. However, this overall change in motion is not uniform across the cholesterol molecule. This result establishes that this cholesterol labeling pattern will have great utility in reporting on cholesterol dynamics and orientation in a variety of environments and with different membrane bilayer components, as well as monitoring the mevalonate pathway product interactions within the bilayer. Finally, the flexibility and universality of acetate labeling will allow this technique to be widely applied to a large range of lipids and other natural products.

Introduction

Quadrupolar nuclei report on molecular structure,1 dynamics,2 and chemical coordination3 in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (SSNMR) spectroscopy. Their ubiquity across the periodic table ensures that SSNMR can target quadrupolar nuclei in many types of materials. Spin >1/2 nuclei have more than two Zeeman splitting energy levels, unlike their spin 1/2 counterparts. The electric field gradient surrounding these nuclei introduces asymmetry in energy level spacing and additional energy splittings. The electric field gradients alter the Zeeman energy levels and lead to inhomogeneously broadened spectra from which the quadrupolar coupling pattern (CQ) and the asymmetry parameter (ηQ) characterize the local electronic environment. Under magic-angle spinning (MAS), the characteristic homogeneously broadened line shape breaks into a quadrupolar sideband manifold. The sideband pattern reports on the hybridization state, molecular geometry, electrostatic interactions, and molecular motions within the sample. In the studies of biological systems in solids, deuterium is the most commonly used quadrupolar nucleus. It is often introduced to decrease the effective 1H–1H dipolar interactions of samples. This attenuates relaxational processes, improving spectral resolution. 2H enrichment is used for protein structure determination and to quantify molecular motions.4−92H also has a rich history as a means of investigating motions in lipid bilayers.10−152H (S = 1) is most often carried out by measuring effective quadrupolar magnitudes and comparing them to the static limit, allowing for measurement of ordered parameters. For example, Chakraborty et al. demonstrated using 2H-labeled 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine that successive additions of cholesterol increases membrane ordering. This contradicted past assumptions that cholesterol does not significantly alter the mechanical properties of unsaturated lipid bilayer systems.16 The motional timescales probed by 2H-based order parameters also facilitated highly synergistic 2H SSNMR-molecular dynamics studies, permitting comparison between computational and experimental results. Recent work from Huster and colleagues identified how the small neurotransmitter serotonin is able to restructure the raft domains in model mimetic membrane systems.17 This has drastic implications within neuron biology as the phase behavior augmenting the lipid raft behavior of the pre- and post-synaptic vesicle membranes is believed to play a key part within the propagation of current within these excitable cells.18−20

SSNMR spectroscopy is uniquely capable of interrogating dynamical and structural interactions between sterols, phospholipids, membrane proteins, and other lipid bilayer components on multiple timescales under physiological conditions.21−27 Using cholesterol with high isotopic enrichment drove a recent SSNMR study and reported cholesterol dimer formation within a lipid bilayer.28 Further work examined cholesterol interactions with the M2 influenza protein,29 with profound implications for viral budding.22 Other recent work targeted the HIV fusion protein gp41 and direct cholesterol interactions within lipid bilayers.21 However, a key element lacking from extant studies is a cheap and effective means of introducing 2H into cholesterol and other bilayer components. This limits the applicability of SSNMR techniques to commercially available site specifically deuterated cholesterol with natural abundance 13C. This limitation also restricts the components of cholesterol that may be studied. We have therefore observed a niche position that may be filled with a cheap alternative that provides greater spectroscopic freedom for a wider variety of structural characterization methods.

Below, we introduce a cost-effective means of 2H and 13C enrichment of cholesterol (Figure 1a). Given similar metabolic pathways, our 2H,13C enrichment protocol is generalizable for multiple sterol and polycyclic lipids, enabling a wide range of labeling strategies. In principle, our isotopic enrichment method could aid in any study requiring enrichment with deuterium or tritium. We exploit the direct route of acetate metabolism toward acetyl-CoA, the entry molecule to this mevalonate pathway, using 2H,13C-acetate.30 The mevalonate pathway is conserved in the production of polycyclic lipids in archaea, eukaryotes, and some bacteria.31 The general utilization of the products of the mevalonate pathway leads to highly predictive labeling of essential functional lipids that span most domains of life.32 These include sterols, hormones,33 hopanoids,34 and vitamins.35 Direct protein interaction with these natural products is an extremely active field of study, with direct implications for therapeutic development.36 The cholesterol biosynthetic pathway is well characterized.33 Recent studies reported site-specific 13C labeling of cholesterol using the RH6829 strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered by the Riezman laboratory.37,38 This has proven to be a highly cost-efficient method for labeling cholesterol in quantities necessary for NMR structural studies.21,28,29,39 Here, we grow the RH6829 yeast strain with U–2H,13C-acetate to selectively “skip-label” sites within cholesterol with 2H while retaining high (∼85%) 13C enrichment.

Figure 1.

Confirmation of predicted 2H enrichment of cholesterol. (a) Schematic representing the passage of 2H from U–2H–13C acetate through the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway. (b) GC–MS of purified cholesterol extracts in the negative ion collection mode. The highest peak height of each sample is normalized to 1. Depicted are the NA-cholesterol standard (black), 13C-cholesterol (blue), and 2H,13C-cholesterol (red). (c) rINEPT spectra of fully protonated 13C-labeled cholesterol (blue) and 2H–13C cholesterol (red). Resonances predicted to have 2H incorporation show dramatically reduced spectral intensity. (d) Comparison of 2H to 13C adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP (red) and 1H to 13C cross-polarization (blue) of 2H–13C cholesterol. In aggregate, these data suggest that 2H species largely remain bound to the same 13C site throughout cholesterol biosynthesis.

We use these highly enriched samples to quantify the site-specific molecular motions of cholesterol in lipid bilayers of different compositions using two-dimensional (2D) 2H–13C correlation spectroscopy.40−43 In these spectra, the dynamically averaged 2H sideband manifolds are reported on the covalently bound 13C resonance. This illustrates how this isotopic enrichment pattern can be utilized to study the dynamic interactions of cholesterol with lipids, transmembrane-/membrane-associated proteins, and other bilayer components. These spectra also encode the phase-related dynamic properties of cholesterol under different samples and experimental conditions. We foresee this method as a non-invasive probe of native cholesterol interactions within biological and biologically derived membranes. In this vein, we assess the effects 2H incorporation has on the dipolar-assisted rotational resonance (DARR) efficiency in comparison to fully protonated 13C-labeled cholesterol. We also quantify the changes in chemical shift 2H imparts onto 13C resonances. We further quantify the site-specific dynamics of cholesterol in two model lipid bilayers by measuring the 2H quadrupolar manifold. In organic molecules, 2H quadrupolar magnitudes span up to ∼180 kHz at the rigid limit. Unfortunately, site-specific resolution is prevented by peak degeneracy in one-dimensional (1D) 2H SSNMR. Therefore, we resolve each site in cholesterol using 2H–13C 2D correlation spectroscopy. This heteronuclear correlation (HETCOR) encodes the quadrupolar coupling sideband manifold in the indirectly detected dimension. This information is transferred to the directly bound 13C resonance for direct detection. While this experiment appears relatively straightforward, the bandwidth required to measure a complete quadrupolar coupling complicates the complete transfer of the 2H sideband manifold to a neighboring spin 1/2 nucleus. Traditional adiabatic ramped CP cannot accommodate the required bandwidth. Recently, adiabatic rotor echo short pulse irradiation cross-polarization (RESPIRATIONCP)41,44 was found to exhibit sufficient transfer bandwidth to accommodate the entire 2H manifold. Thus, we are capable of resolving most cholesterol sites within each bilayer of interest and are able to report their quadrupolar coupling value.

Results and Discussion

Production of 13C- and 2H,13C-cholesterol

We produced both 13C-enriched and 2H,13C-enriched cholesterol the RH6829 strain of S. cerevisiae (gifted from Professor Riezman at the University of Geneva). This strain is modified to produce cholesterol instead of ergosterol. We adapted the reported protocol exploiting acetate metabolism to acetyl-CoA, which is an entry substrate to this mevalonate pathway. Cells were grown from yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) medium consisting of 1 g of 13C or 2H,13C-sodium acetate, 7 g of yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 5 g of yeast extract, 40 mg of leucine, 40 mg of uracil, and 10 g of d-glucose. After saponification, we extracted sterols with petroleum ether and purified the crude material using a silica flash column. We used high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) through a C18 reversed-phase column to selectively separate cholesterol after batch purification. Identification of the cholesterol-containing elution peak was confirmed by comparison to the elution of a cholesterol standard mixture (Avanti Polar lipids).

Quantification of 2H and 13C Enrichment

We determined the purity and 13C incorporation of purified 13C-cholesterol against all possible variations of isotopic enrichment using gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC–MS). GC–MS data exhibited the well-established cholesterol fragmentation pattern with the highest peak at a standard literature value of 386.4 m/z. The terminal fragmentation pattern for U–13C-labeled cholesterol and 2H,13C-labeled cholesterol contained a distribution of masses (Figure 1b). First, the 13C-labeled cholesterol sample had a maximum mass increase of 27 amu, in agreement with all carbons in cholesterol being 13C enriched. Thus, in our hands, the 13C-acetate-based method reported by Della Ripa et al.39 labels ∼6% of the cholesterol molecules uniformly and 96% of the cholesterol molecules with >16 13C-labeled sites, thus demonstrating the efficiency of acetate labeling of cholesterol. Overall, ∼85% of carbons are 13C enriched. These results confirm the robust reproducibility of cholesterol labeling using 13C-acetate. Next, we quantified the efficiency of 2H enrichment for 2H,13C-cholesterol. Compared to the natural abundance cholesterol standard, the maximum peak for 2H,13C-cholesterol is +50.1 m/z above the standard, indicating substantial 2H and 13C incorporation. We compared the largest peak size in the mass spectrum (Figure 1b) and observe that the distribution of 2H,13C-cholesterol masses to the 13C-labeled cholesterol have a consistent ∼23 m/z increase but the relative span of the mass distribution remaining the same. This is contrary to our expectations as we expected a wider span of mass distribution for the final fragmentation pattern as the possible permutations of 2H and 13C fractional labeling would compound the complexity of the spectra. This suggested 2H atoms covalently bound to 13C sites in the 2H,13C-acetate largely remain bound during cholesterol biosynthesis, ensuring fidelity of predicted labeling patterns. Our GC–MS data obviously cannot adequately determine the site specificity of 13C or 2H incorporation, but the mass distributions are consistent with this conclusion (Table 1).

Table 1. Quadrupolar Sideband Manifold Fit Values of 2H–13C Cholesterol Positions in 2:1 POPC/Cholesterol.

| sample | 2 POPC/1 cholesterol | |||||

| temperature | –5 ± 2 °C | 15 ± 2 °C | 35 ± 2 °C | |||

| position | 2Haa | 2Hbb | 2Ha | 2Hb | 2Ha | 2Hb |

| C1 | 114 ± 6 | 33 ± 4 | 78.8 ± 5.7 | 37.7 ± 3.9 | 68.7 ± 2.0 | |

| C7 | 79.1 ± 8.0 | 34.8 ± 7.4 | 82.7 ± 7.5 | 32.8 ± 2.5 | ||

| C15 | 75.6 ± 2.6 | 80.6 ± 4.7 | 27.6 ± 8.5 | |||

| C17 | 71.8 ± 4.1 | 52.0 ± 1.6 | ||||

| C18 | 23.6 ± 0.8 | 18.6 ± 0.48 | 19.8 ± 0.5 | |||

| C19 | 24.3 ± 0.6 | 19.0 ± 0.49 | 18.75 ± 0.50 | |||

| C21 | 26.2 ± 0.5 | 19.6 ± 0.57 | 19.77 ± 0.58 | |||

| C22 | 105 ± 5 | 36 ± 3 | 85.9 ± 2.0 | 28.6 ± 1.7 | 81.5 ± 2.4 | 28.4 ± 2.2 |

| C24 | 45 ± 2 | 33.6 ± 0.73 | 27.6 ± 0.99 | |||

| C26/27 | isotropic | isotropic | isotropic | |||

2Ha denotes the higher CQ of a CH2 group.

2Hb denotes the lower CQ of a CH2 group. If 2Hb is missing, then the value could not be extracted from the higher CQ value.

Confirmation of Site-Specific 2H and 13C Enrichment by 1D SSNMR

Liposomes with a 2:1 ratio of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC)/13C-cholesterol or 2H,13C-cholesterol were prepared as described below. We used these samples to assess the site-specific incorporation of 1H and 2H into 2H,13C-cholesterol using 1H–13C-refocused insensitive nuclei enhancement by polarization transfer (rINEPT) (Figure 1c) and adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP (Figure 1d), respectively. The rINEPT pulse sequence transfers polarization through the one-bond scalar J-coupling. Because rINEPT transfers polarization through the chemical bond, it is ideal for correlating site-specific isotopic enrichment to chemical bonds. Thus, only 13C resonances directly bound to 1H will be visible in these spectra. These peaks will correlate with sites where the hydrogen species do not originate from 2H,13C-acetate via the mevalonate pathway. This through-bond 1H to 13C transfer was achieved using a 1.25 ms delay between refocusing pulses. We observe that the peak intensities for resonances predicted to have 2H incorporation diminish dramatically compared to the completely protonated 13C-labeled cholesterol (red vs blue, Figure 1c). There is only very weak signal for predicted 2H-enriched sites C3, C1, C24, C24, C7, C26/27, C19, C21, C15, and C18, implying that these resonances are heavily deuterated. C13 and C10 lack a directly bound 1H and are therefore invisible through rINEPT polarization transfer. These spectra were normalized to the height of the natural abundance lipids as a control for unequal amounts of cholesterol in each sample. However, some peak intensities for fully protonated 13C resonances increase in the 2H,13C-cholesterol sample. This observation is attributed to increased T2 from the diluted 1H bath, improving 1H to 13C transfer. C9 was expected to have 2H incorporation, but all experiments indicate that this carbon is bound to 1H. We also attempted 2H to 13C rINEPT to ascertain 2H incorporation, but the required insensitive nuclei enhanced by polarization transfer delay times were longer than the effective T2 of 2H (∼10 ms); thus, no signal was observed. We instead used 2H–13C dipolar couplings (through space) to transfer polarization from 2H to their directly bound 13C nucleus. As described in more detail below, we employed the adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP pulse sequence to transfer polarization from 2H to 13C (Figure 1d) with a relatively short contact time (∼1 ms) targeting one bond distances. This spectrum confirmed that the remaining sites in cholesterol were highly 2H enriched (Table 2).

Table 2. Quadrupolar Sideband Manifold Fit Values of 2H–13C Cholesterol Positions in POPC/Sphingomyelin/Cholesterol.

| sample | 1 POPC/1 sphingomyelin/1cholesterol | |||||

| temperature | –5 ± 2 °C | 15 ± 2 °C | 35 ± 2 °C | |||

| position | 2Ha | 2Hb | 2Ha | 2Hb | 2Ha | 2Hb |

| C1 | ||||||

| C7 | ||||||

| C15 | ||||||

| C17 | ||||||

| C18 | 25.6 ± 0.13 | 26.3 ± 0.14 | 18.9 ± 0.19 | |||

| C19 | 25.6 ± 0.17 | 20.4 ± 0.18 | 18.7 ± 0.19 | |||

| C21 | 24.3 ± 0.17 | 21.1 ± 0.17 | 18.9 ± 0.19 | |||

| C22 | 79.55 ± 0.36 | 8.2 ± 2.75 | 71.6 ± 0.39 | 26 ± 0.81 | 72.0 ± 10.76 | 57.2 ± 2.47 |

| C24 | 44.2 ± 0.57 | 31.1 ± 0.29 | ||||

| C26/27 | isotropic | isotropic | isotropic | |||

Impact of Skip-Labeled Deuteration on 13C Chemical Shifts and Spin Diffusion

The kinetic isotope effect associated with replacing 1H with 2H slightly alters molecular orbitals. This can, in turn, change 13C chemical shifts. Additionally, the 13C–13C spin-diffusion pathways rely on the large dipole–dipole couplings between 1H and 13C nuclei to broaden the energy levels and improve the 13C–13C polarization-transfer efficiency. We acquired 2D DARR 13C–13C correlation spectra to gauge both of these effects. In Figure 2 (blue), we depict a 2D 13C–13C correlation spectrum of uniformly 13C-labeled cholesterol in a 1:2 ratio with POPC acquired with 200 ms of DARR at a set point of 0 °C. This spectrum illustrates the completeness of our chemical shift assignments and the efficiency of DARR polarization transfer through spin relay. We clearly observe cross peaks between C3 and distal resonances, including C9 (4.4 Å; SNR: 77), C11 (5.4 Å; SNR: 12), C14 (6.6 Å; SNR: 18), and C15 (7.8 Å; SNR: 10). These correlations indicate strong through-space couplings from one end of the ring structure of cholesterol to the other. We then acquired a spectrum of 2H,13C-cholesterol under the same experimental conditions (Figure 2, red). We clearly observe that the dilution of the 1H spin bath reduced DARR polarization-transfer efficiency. For example, only the C3 to the C9 (SNR: 9) correlation is retained. It is clear from this spectrum that spin transfers are limited to one to three bond distances (1.6–4.5 Å) at an identical 200 ms DARR mixing time. It is also clear that 2H introduces small changes in the observed 13C chemical shifts. The measured 13C chemical shifts are provided in Table S1.

Figure 2.

Comparison of 2D 13C–13C spectra of “skip-labeled” 2H–13C cholesterol to fully protonated 13C-cholesterol acquired with 200 ms DARR mixing. (a) Overlay of the aliphatic region of the spectrum of 2H–13C cholesterol (red) onto the spectrum of 1H–13C cholesterol (blue). (b) Expansion of the central region of (a). This data indicates a reduction in DARR efficiency and clear changes in chemical shift for 13C resonances directly bound to 2H.

2H-Edited 13C–13C Correlation Spectra

In Figure 2, both DARR spectra are acquired with 1H to 13C CP. This polarization transfer is through space. The 1H–13C dipole–dipole couplings are strong enough so that a 13C nucleus without a directly bound 1H can still be excited if the transfer time is lengthened. However, 2H–13C couplings are weak enough, and 2H–13C excitation may be explored as a convenient means of spectral editing. In extensively, but not uniformly, 2H-enriched samples, it is straightforward to begin 13C to 13C polarization transfer from only 2H-bound 13C resonances. In addition, the quadrupolar moment of 2H increases the R1 relaxation rate relative to 1H. Thus, while the initial polarization on 2H is lower, more transients can be acquired per unit time. This allows for an increased rate of transient acquisition when polarization is initiated on 2H, with a recycle delay short as 250 ms being possible.2 (We use a recycle rate of 500–750 ms throughout our experiments to reduce equipment duty and control RF heating of the sample.) This method has facilitated the rapid acquisition of a 13C–13C correlation spectrum with polarization initiated via 2H excitation, followed by adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP (Figure 3b). We used this 2H-excited adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP 13C–13C correlation spectrum to confirm 2H incorporation assignments. This was especially important for the resonance at 38.6 ppm, which we assigned to C22, for which we observe an unexpected behavior and will expand upon in the text below. However, this spectrum illustrates the efficacy of 2H spectral editing. Indeed, future applications could utilize 13C–13C polarization-transfer pulse sequences radio frequency-driven recoupling or DREAM which will benefit from the reduced 1H–13C dipole–dipole couplings and produce edited high signal-to-noise spectra.

Figure 3.

Adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP for 13C–13C correlation assignments within cholesterol. (a) Pulse sequence for adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP. (b) 2H-excited adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP 13C–13C correlation spectrum (black) with 200 ms of DARR mixing overlaid onto otherwise identical experiment, but starting with 1H to 13C CP (red). (c) Adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP 13C 1D spectra with 1.33 ms of contact time at set point temperatures of −20, 0, and 20 °C.

2H–13C 2D Spectra to Measure Lipid Dynamics

The 2H quadrupolar manifold spans an extremely wide bandwidth, with a quadrupolar coupling rigid limit of ∼175 kHz for 2H bound to aliphatic 13C. Compared to the rigid limit of a 1H–13C/15N dipolar covering rigid limit dipolar coupling value of ∼23 kHz, the 2H quadrupolar coupling benefits from a less error prone measurement and is able to report on a finer microsecond time scale. We test this sensitivity to differing motional time scales by investigating 2H quadrupolar manifolds of cholesterol under a range of temperatures and in two different lipid mixtures. For this purpose, we prepared a third liposomal sample with a 1:1:1 ratio of POPC/sphingomyelin/2H,13C-cholesterol. It is observed in Figure 3c that the adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP-transfer efficiency varies at different temperatures under identical CP contact times. The lowest temperature appears to facilitate more efficient transfer of the methyl species, C18, C19, C21, and C26/27 due to the decreased dynamics and the resulting stronger dipolar couplings between 2H and 13C. These CP efficiencies drop as the temperature is increased following the increase in dynamics as the bilayer phase transitions from a gel phase to a more liquid-crystalline phase. Resonances are located upon the ring structure of cholesterol, C1, C7, C15, and C17, with the addition of C22 located near the base of the cholesterol tail. The conservation of CP efficiency of these peaks across the temperature range implies that the rigid ring structure preserves the dipolar coupling between 2H and 13C of these resonances. We additionally observe an increase in the resolution of the ring structure peaks, demonstrating the increased motion of cholesterol in the bilayer across the temperatures measured impacting the transverse relaxation of cholesterol.

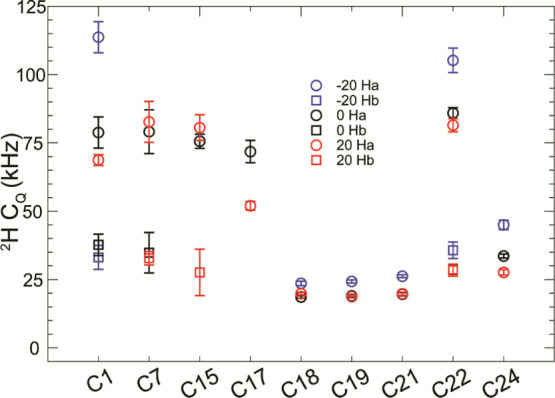

Encouraged by the changes in RESPIRATIONCP efficiency observed at different temperatures, we hypothesize that changes to the dynamics of the bilayer are occurring on the time scale of the quadrupolar coupling and are therefore directly manifest in the dynamically sensitive quadrupolar coupling. To pursue this hypothesis, we acquired a 2H to 13C HETCOR to assess site specifically the dynamics changes to cholesterol. In Figure 4, we show the alterations to the sideband manifold for the 2:1 POPC/cholesterol sample at a range of temperatures. Utilization of adiabatic RESPIRATIONCP allowed for the full unobstructed 2H sideband manifold to be transferred to the indirect dimension correlating with the 13C resonance the 2H is bound (Figure 4a). As expected with increasing sample temperature, the quadrupolar coupling constant should decrease as the temperature increases, as the coupling is attenuated by molecular motions, and indeed this is the case (Figure 4b). For comparison, identical RESPIRATIONCP HETCOR spectra were acquired for the 1:1:1 POPC/sphingomyelin/cholesterol sample. This lipid mixture was chosen because of its known propensity to form cholesterol-rich lipid microdomains, or “lipid rafts.”18,45,46 For both samples containing 2H,13C-cholesterrol, each peak was fit at the temperatures of 20, 0, and −20 °C (Figure 4c–e). In all fits, the η parameter was assumed to be 0 as the asymmetric sharing of electrons between 2H and 13C for aliphatic carbons is negligible. We note that sideband manifolds for 2H directly bound to the ring structure exhibit greater quadrupolar ordering than methyl groups (C18, C19, C21, and C26/27) or C22 and C24 in the acyl chain owing to the rigid nature of the ring structure. In both samples, the methyl groups exhibit extremely small quadrupolar coupling values as a rapid three-site exchange attenuates the 2H quadrupolar coupling. For the methylene groups of C1, C7, C15, and C22, two populations of 2H couplings were identified, corresponding to a large and small quadrupolar coupling, and were identified as a separate 2H bound to the same 13C site. We additionally note that the cholesterol tail residue C22 displays an unexpectedly high quadrupolar coupling values, which reduce in the 1:1:1 POPC/sphingomyelin/cholesterol sample at physiological temperatures, with the C24 resonance disappearing entirely at 35 °C. This is an interesting observation. In previous SSNMR investigations, it was observed that introduction of cholesterol increased the overall order of surrounding 2H-enriched lipid acyl chains. However, here, we observe that the ordering of the cholesterol rings is nearly identical between the POPC/cholesterol and POPC/sphingomyelin/cholesterol samples, but with increased dynamics in the cholesterol acyl chain in the raft-forming lipid mixture. Thus, this small observation suggests samples prepared with our 2H,13C labeling pattern could be leveraged to tease out finer details of membrane biophysics in future work and to compliment measurements taken of the surrounding lipids. As one final note, 2H sideband manifolds and the powder line shapes observed in static spectra also report upon cholesterol orientation, as was recently exploited in a study of cholesterol in contact with the influenza H+ channel M2.22 Thus, our 2H,13C-cholesterol could be utilized for structural arrangements of cholesterol around membrane proteins and other biological assemblies (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

2H–13C HETCOR of cholesterol and fitting of the 2H sideband manifolds. (a) Projection of the central splitting band at each of the temperatures with resonances assigned and (b) HETCOR spectrum of the three assessed temperatures. Red: 20 °C; black: 0 °C; and blue: −20 °C. Dashed lines correspond to the sideband fits below. (c–e) Sideband manifold of C1, C24, and C21, respectively. The black spectrum is the experimental data, and the red spectrum is the simulated best fit model. The gray spectrum is the residual of the fit. The temperature of each fit is noted to the left of C. In (c), for C1 at 0 and −20 °C, green and blue simulated spectra correspond to the individually fit 2H populations.

Figure 5.

Temperature dependence of the quadrupolar couplings within cholesterol in the 2:1 POPC/cholesterol sample. Lower quadrupolar couplings are generally shown as the temperature decreases. 2Ha denotes the higher CQ of a CH2 group. 2Hb denotes the lower CQ of a CH2 group. If 2Hb is missing, then the value could not be extracted from the higher CQ value.

Conclusions

We contend that the efficacy of this labeling strategy is great enough that it allows for a very cost-effective means of producing highly 2H enriched cholesterol. This is manifest as the 2H,13C-acetate starting material is far more affordable than many other isotopically enriched reagents. Additionally, the ease of this method of cell growth and purification is well documented. It can consistently produce 50–100 mg of cholesterol from a single liter of growth culture. Thus, this method of 2H,13C-cholesterol production is an attractive route for NMR structural studies without the need for using large amounts of relatively expensive 2H2O-based media. Additional 2H incorporation into cholesterol is feasible through addition of 2H2O though a greater initial cost for diminished returns. We additionally note small chemical shift perturbations within the sterol ring structure for sites with 2H directly bound, following the deuterium isotope effect.

Modern-day SSNMR technology and techniques facilitate full utilization of all isotope species within the skip-labeled 2H–13C cholesterol. We have shown herein that the skip labeling scheme produces selective cholesterol enrichment of high-enough quality for multidimensional NMR experiments. Site-specific isotopic enrichment of cholesterol was measured by the use of polarization-transfer techniques well suited to the spin of the nucleus being investigated, with detection along 13C for unambiguous site specificity. We qualify the sample’s high quality through a series of homonuclear and heteronuclear multidimensional experiments. In the homonuclear correlation experiments, we take advantage of the rigid cholesterol ring structure to determine the distance of polarization transfer with a diminished 1H spin bath and observe abundant short-range to medium-range contacts.

We further interrogate cholesterol’s motional timescale in the bilayer by investigating the 2H–13C quadrupolar coupling through heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy. We observe site specifically alterations to the 2H line shapes of cholesterol within the 2:1 POPC/cholesterol as a function of temperature.

This work establishes an additional, highly affordable method for producing doubly isotopically labeled cholesterol in a predictable 2H incorporation pattern. The ability to skip label the 2H sites allows for additional motional time scales to be probed within the lipid bilayer, while retaining the 1H population for 1H–13C dipolar-coupling chemical shift correlation studies. Additionally, recent advances in solid-state NMR quadrupolar dynamics techniques such as 2H chemical exchange saturation transfer monitor slow dynamics that could further inform lipid-phase changes and protein interactions. The dilution of the 1H bath of cholesterol also enables 1H detect methods to further interrogate protein–ligand interactions. Herein, we show the applicability of the skip-labeled 2H–13C cholesterol using MAS SSNMR, but we foresee broader applicability of use with this sample for investigations into cholesterol–protein interactions using orientated sample NMR and neutron diffraction.

Methods and Materials

The cholesterol producing yeast strain RH6829 (gifted by Professor Riezman at the University of Geneva) was used to produce 13C-labeled cholesterol. Cells were plated onto YPD media supplemented with kanamycin and ampicillin to an effective concentration of 50 μL/mL. Cell colonies were allowed to grow for 48 h before 5 large colonies were used to inoculate 500 mL of YPD medium consisting of 1 g of 13C-labeled sodium acetate, 7 g of yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 5 g of yeast extract, 40 mg of leucine, 40 mg of uracil, and 10 g of d-glucose. Cells were allowed to grow for 72 h at 30 °C and then shaken at 185 rpm until the medium was confluent. The cells were spun down at 5500 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min.

Crude sterols were extracted following a modified sterol extraction procedure.47 The cells were resuspended in 1 mL of 0.1 M HCl per gram of cells. This was then transferred to a flask and refluxed at 90 °C for 1 h. To this, 10 mL of 100% ethanol per gram of cells was added to the flask and refluxed for an additional hour. At this point, 10 mL of 50% KOH (w/v) per gram cells was added to the flask and refluxed for 2 h. The sample was then allowed to cool before sterols were extracted using petroleum ether organic phase extraction. Sterols were extracted three times with petroleum ether. The extracts were pooled, and sodium sulfate was added to remove residual water and dried under a N2 stream.

Excess non-steroidal lipid and cellular debris for HPLC sample preparation was removed via the flash column chromatography method. First, the non-saponifiable fraction of lipid yeast extract is dissolved in hexane, filtered, and added to a 4 cm diameter chromatographic column. The column is preloaded with a 50 mL bed volume (BV) of hexane-rinsed Millipore Sigma 60 Å silica gel. The sample is loaded by pouring the hexane-dissolved sample and allowing the hexane to pass through. Once the loading is complete, a hexane rinse of 10 BV hexane is done. The column is then rinsed with diethyl ether to elute the sterol fraction and dried using a rotovap. The pass-through fractions, hexane and fresh hexane rinse, will be discarded upon confirmation of sample collection in the ether fraction.

HPLC Purification

The sample is dissolved in 70:30 acetonitrile/ethanol solution to 1.5 mg/mL for HPLC purification. This is done using a Phenomenex semipreparative, C18(2), 100 Å pore size, 10 μm particle size, 250 × 10 mm LC column on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 system using an isocratic 30% solvent A (90% ethanol, 5% isopropyl alcohol, and 5% methanol) and 70% solvent B (acetonitrile) at 2 mL/min, 20 °C method. The sample peak was identified using 210 and 282 nm absorbance and by comparing retention times to cholesterol standard. The sample is then dried as before with a rotovap. The sample is then run through a final flash column, as noted previously, for a final polishing step. The samples were then dried under a N2 stream and stored at −20 °C until further use.

GC Quantification

The sample is then quantified by resuspension in a known volume of acetone and injection into a 2 mm ID × 50 cm glass column packed with 3% SE-30 installed into a 5890 Series II gas chromatograph (GC) with a flame ionization detector and HP 3395 integrator. Its registered area was compared to a 1 mg/mL cholesterol standard and mass calculated.

GC–MS Identification

GC–MS compound identification and purity were checked using an HP 6890 GC interfaced with an HP 5973 mass spectrometer using a ZB-5 capillary column at a programmed temperature range from 170 to 280 °C at 20 °C/min and a constant flow of helium gas at 1.2 mL/min. The MS was operated at an ionization voltage of 70 eV and an interface temperature of 250 °C in the negative ion mode. Compound peaks were identified through comparing retention times and fragmentation patterns to laboratory standards.

NMR Sample Preparation

POPC and sphingomyelin lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Lipids were solubilized in chloroform to a concentration of 5 mg/mL and mixed in the following molar ratios to the final lipid quantities: 1:1:1 POPC/sphingomyelin/cholesterol and 2:1 POPC/cholesterol. The lipids were dried under a N2 gas stream to a film within a glass container and left under vacuum overnight to remove any excess solvent. The samples were then resuspended in a solution of 50 mM Tris-base, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.02% NaN3, and pH 7.5 w/HCl. Hydrated films were then periodically sonicated to generate lamellar vesicles. Once the mixture was homogeneous, the sample was pelleted using a benchtop centrifuge (Eppendorf 5430 R, fixed angle rotor, 17,500 rpm). The supernatant was decanted, and the resulting pellet was transferred to an Agilent 1.6 mm Pencil FastMAS rotor. This sample preparation has been characterized and validated by our laboratory for different lipid mixtures, including native stain electron microscopy, which were found to be large unilamellar vesicles prior to pelleting and packing into the rotor.48 We recently used this procedure to produce cholesterol-rich liposomes prior to inserting KirBac 1.1 to determine the structural details of KirBac 1.1 inactivation by cholesterol.49 Assay data within that text further established the formation of LUVs.

Solid-State NMR

All experiments were acquired on a 600 MHz Agilent DD2 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies) equipped with a FastMAS probe in the hardware configuration definition configuration. 13C was referenced indirectly to the decision support system using the peak at 40.48 ppm of adamantane. The recycle delay was set to 1.5 s for experiments requiring 1H preparation and 0.75 for experiments starting with 2H preparation. The standard pulse widths were 1.5 μs for 1H and 13C and 2.0 μs for 2H. In rINEPT experiments, all delay times were set to 1.25 ms. 2H to 13C RESPIRATIONCP experiments were acquired with 1.8 μs hard pulses and adiabatic ramps of delta ranging from 1000 to 1500 rad/sec and beta ranging from 3200/2π to 7500/2π Hz. All experiments were acquired for 20.48 ms in the direct dimension.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. Howard Riezman for his gift of the RH6827 strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Byeong (Andrew) Cho for stimulating discussions over the GC–MS data interpretation.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c00796.

Site-specific chemical shift differences of deuterated cholesterol (PDF)

Author Present Address

† University of Wisconsin–Madison, Department of Biochemistry, Madison, WI, United States

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award (MIRA, R35, R35 GM124979).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gelenter M. D.; Wang T.; Liao S.-Y.; O’Neill H.; Hong M. 2H-13C correlation solid-state NMR for investigating dynamics and water accessibilities of proteins and carbohydrates. J. Biomol. NMR 2017, 68, 257–270. 10.1007/s10858-017-0124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Rienstra C. M. Site-Specific Internal Motions in GB1 Protein Microcrystals Revealed by 3D 2H-13C-13C Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 4105–4119. 10.1021/jacs.5b12974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt M. J.; Mackay A. L. Deuterium And Nitrogen Pure Quadrupole-Resonance In Deuterated Amino-Acids. J. Magn. Reson. 1974, 15, 402–414. 10.1016/0022-2364(74)90143-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schanda P.; Ernst M. Studying dynamics by magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy: Principles and applications to biomolecules. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2016, 96, 1–46. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linser R.; Dasari M.; Hiller M.; Higman V.; Fink U.; Lopez del Amo J.-M.; Markovic S.; Handel L.; Kessler B.; Schmieder P.; Oesterhelt D.; Oschkinat H.; Reif B. Proton-Detected Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy of Fibrillar and Membrane Proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4508–4512. 10.1002/anie.201008244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hologne M.; Chevelkov V.; Reif B. Deuterated peptides and proteins in MAS solid-state NMR. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2006, 48, 211–232. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2006.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hologne M.; Faelber K.; Diehl A.; Reif B. Characterization of dynamics of perdeuterated proteins by MAS solid-state NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11208–11209. 10.1021/ja051830l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevelkov V.; van Rossum B. J.; Castellani F.; Rehbein K.; Diehl A.; Hohwy M.; Steuernagel S.; Engelke F.; Oschkinat H.; Reif B. H-1 detection in MAS solid-state NMR Spectroscopy of biomacromolecules employing pulsed field gradients for residual solvent suppression. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 7788–7789. 10.1021/ja029354b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif B.; Griffin R. G. 1H detected 1H,15N correlation spectroscopy in rotating solids. J. Magn. Reson. 2003, 160, 78–83. 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goñi F. M.; Alonso A.; Bagatolli L. A.; Brown R. E.; Marsh D.; Prieto M.; Thewalt J. L. Phase diagrams of lipid mixtures relevant to the study of membrane rafts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2008, 1781, 665–684. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. F.; Heyn M. P.; Job C.; Kim S.; Moltke S.; Nakanishi K.; Nevzorov A. A.; Struts A. V.; Salgado G. F. J.; Wallat I. Solid-State 2H NMR spectroscopy of retinal proteins in aligned membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2007, 1768, 2979–3000. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aussenac F.; Tavares M.; Dufourc E. J. Cholesterol Dynamics in Membranes of Raft Composition: A Molecular Point of View from 2H and 31P Solid-State NMR. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 1383–1390. 10.1021/bi026717b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefcik M. D.; Schaefer J.; Stejskal E. O.; Mckay R. A.; Ellena J. F.; Dodd S. W.; Brown M. F. High-Resolution Solid-State C-13 Nmr-Studies of Unsonicated Membrane Dispersions. Biophys. J. 1983, 41, A282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield E.; Adebodun F.; Chung J.; Montez B.; Park K. D.; Le H. B.; Phillips B. C-13 Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance Spectroscopy Of Lipids - Differential Line Broadening Due To Cross-Correlation Effects As A Probe Of Membrane-Structure. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 11025–11028. 10.1021/bi00110a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler H.; Seelig J. Deuterium Order Parameters in Relation to Thermodynamic Properties of a Phospholipid Bilayer - Statistical Mechanical Interpretation. Biochemistry 1975, 14, 2283–2287. 10.1021/bi00682a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S.; Doktorova M.; Molugu T. R.; Heberle F. A.; Scott H. L.; Dzikovski B.; Nagao M.; Stingaciu L.-R.; Standaert R. F.; Barrera F. N.; Katsaras J.; Khelashvili G.; Brown M. F.; Ashkar R. How cholesterol stiffens unsaturated lipid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 21896–21905. 10.1073/pnas.2004807117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engberg O.; Bochicchio A.; Brandner A. F.; Gupta A.; Dey S.; Böckmann R. A.; Maiti S.; Huster D. Serotonin Alters the Phase Equilibrium of a Ternary Mixture of Phospholipids and Cholesterol. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 578868. 10.3389/fphys.2020.578868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leftin A.; Job C.; Beyer K.; Brown M. F. Solid-State 13C NMR Reveals Annealing of Raft-Like Membranes Containing Cholesterol by the Intrinsically Disordered Protein α-Synuclein. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 2973–2987. 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfrieger F. W. Role of cholesterol in synapse formation and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembranes 2003, 1610, 271–280. 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J.; Wu J.; Shao H.; Kong F.; Jain N.; Hunt G.; Feigenson G. Phase studies of model biomembranes: Macroscopic coexistence of Lα+Lβ, with light-induced coexistence of Lα+Lo Phases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembranes 2007, 1768, 2777–2786. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon B.; Mandal T.; Elkins M. R.; Oh Y.; Cui Q.; Hong M. Cholesterol Interaction with the Trimeric HIV Fusion Protein gp41 in Lipid Bilayers Investigated by Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 4705–4721. 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins M. R.; Williams J. K.; Gelenter M. D.; Dai P.; Kwon B.; Sergeyev I. V.; Pentelute B. L.; Hong M. Cholesterol-binding site of the influenza M2 protein in lipid bilayers from solid-state NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 12946–12951. 10.1073/pnas.1715127114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Hong M. Investigation of the Curvature Induction and Membrane Localization of the Influenza Virus M2 Protein Using Static and Off-Magic-Angle Spinning Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance of Oriented Bicelles. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 2214–2226. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. F. Soft Matter in Lipid-Protein Interactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2017, 46, 379–410. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070816-033843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leftin A.; Molugu T. R.; Job C.; Beyer K.; Brown M. F. Area per Lipid and Cholesterol Interactions in Membranes from Separated Local-Field 13C NMR Spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2014, 107, 2274–2286. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutajar M.; Ashbrook S.; Wimperis S. H-2 double-quantum MAS NMR spectroscopy as a probe of dynamics on the microsecond timescale in solids. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 423, 276–281. 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.03.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odin C.; Webb G. NMR studies of phase transitions. Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 2006, 5959, 117–205. 10.1016/s0066-4103(06)59003-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins M. R.; Bandara A.; Pantelopulos G. A.; Straub J. E.; Hong M. Direct Observation of Cholesterol Dimers and Tetramers in Lipid Bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 1825–1837. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c10631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins M. R.; Sergeyev I. V.; Hong M. Determining Cholesterol Binding to Membrane Proteins by Cholesterol 13C Labeling in Yeast and Dynamic Nuclear Polarization NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15437–15449. 10.1021/jacs.8b09658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard J.; Moreira D. Origins and Early Evolution of the Mevalonate Pathway of Isoprenoid Biosynthesis in the Three Domains of Life. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 87–99. 10.1093/molbev/msq177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard J.; López-García P.; Moreira D. The early evolution of lipid membranes and the three domains of life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 507–515. 10.1038/nrmicro2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciejak A.; Leszczynska A.; Warchol I.; Gora M.; Kaminska J.; Plochocka D.; Wysocka-Kapcinska M.; Tulacz D.; Siedlecka J.; Swiezewska E.; Sojka M.; Danikiewicz W.; Odolczyk N.; Szkopinska A.; Sygitowicz G.; Burzynska B. The effects of statins on the mevalonic acid pathway in recombinant yeast strains expressing human HMG-CoA reductase. BMC Biotechnol. 2013, 13, 18. 10.1186/1472-6750-13-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nes W. D. Biosynthesis of Cholesterol and Other Sterols. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6423–6451. 10.1021/cr200021m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J.-J.; Solbiati J. O.; Ramamoorthy G.; Hillerich B. S.; Seidel R. D.; Cronan J. E.; Almo S. C.; Poulter C. D. Biosynthesis of Squalene from Farnesyl Diphosphate in Bacteria: Three Steps Catalyzed by Three Enzymes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2015, 1, 77–82. 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.-R.; Lin Y.-K.; Fang J.-Y. Biological and Pharmacological Activities of Squalene and Related Compounds: Potential Uses in Cosmetic Dermatology. Molecules 2009, 14, 540–554. 10.3390/molecules14010540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhaescu I.; Izzedine H. Mevalonate pathway: A review of clinical and therapeutical implications. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 40, 575–584. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivapurkar R.; Souza C. M.; Jeannerat D.; Riezman H. An efficient method for the production of isotopically enriched cholesterol for NMR. J. Lipid Res. 2011, 52, 1062–1065. 10.1194/jlr.d014209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza C. M.; Schwabe T. M. E.; Pichler H.; Ploier B.; Leitner E.; Guan X. L.; Wenk M. R.; Riezman I.; Riezman H. A stable yeast strain efficiently producing cholesterol instead of ergosterol is functional for tryptophan uptake, but not weak organic acid resistance. Metab. Eng. 2011, 13, 555–569. 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Ripa L. A.; Petros Z. A.; Cioffi A. G.; Piehl D. W.; Courtney J. M.; Burke M. D.; Rienstra C. M. Solid-State NMR of highly 13C-enriched cholesterol in lipid bilayers. Methods 2018, 138–139, 47–53. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S. K.; Nielsen A. B.; Hiller M.; Handel L.; Ernst M.; Oschkinat H.; Akbey Ü.; Nielsen N. C. Low-power polarization transfer between deuterons and spin-1/2 nuclei using adiabatic (RESPIRATION)CP in solid-state NMR. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 2827–2830. 10.1039/c3cp54419b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen A. B.; Jain S.; Ernst M.; Meier B. H.; Nielsen N. C. Adiabatic Rotor-Echo-Short-Pulse-Irradiation mediated cross-polarization. J. Magn. Reson. 2013, 237, 147–151. 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbey Ü. Dynamics of uniformly labelled solid proteins between 100 and 300 K: A 2D 2H-13C MAS NMR approach. J. Magn. Reson. 2021, 327, 106974. 10.1016/j.jmr.2021.106974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerring M.; Paaske B.; Oschkinat H.; Akbey Ü.; Nielsen N. C. Rapid solid-state NMR of deuterated proteins by interleaved cross-polarization from 1H and 2H nuclei. J. Magn. Reson. 2012, 214, 324–328. 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S.; Bjerring M.; Nielsen N. C. Correction to “Efficient and Robust Heteronuclear Cross-Polarization for High-Speed-Spinning Biological Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy”. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 2020. 10.1021/jz3008084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels T.; Lankalapalli R. S.; Bittman R.; Beyer K.; Brown M. F. Raftlike Mixtures of Sphingomyelin and Cholesterol Investigated by Solid-State 2H NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 14521–14532. 10.1021/ja801789t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leftin A.; Beyer K.; Brown M. F. An NMR Resource for Structural and Dynamic Simulations of Membranes. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 310. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh E. G.; Dyer W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borcik C. G.; Versteeg D. B.; Wylie B. J. An Inward-Rectifier Potassium Channel Coordinates the Properties of Biologically Derived Membranes. Biophys. J. 2019, 116, 1701–1718. 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borcik C. G.; Eason I. R.; Yekefallah M.; Amani R.; Han R.; Vanderloop B. H.; Wylie B. J. A Cholesterol Dimer Stabilizes the Inactivated State of an Inward-Rectifier Potassium Channel. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202112232 10.1002/anie.202112232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.