Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To estimate the national pregnancy-associated homicide mortality ratio, characterize pregnancy-associated homicide victims, and compare the risk of homicide in the perinatal period (pregnancy and up to 1 year postpartum) with risk among nonpregnant, nonpostpartum females aged 10–44 years.

METHODS:

Data from the National Center for Health Statistics 2018 and 2019 mortality files were used to identify all female decedents aged 10–44 in the United States. These data were used to estimate 2-year pregnancy-associated homicide mortality ratios (deaths/100,000 live births) for comparison with homicide mortality among nonpregnant, nonpostpartum females (deaths/100,000 population) and to mortality ratios for direct maternal causes of death. We compared characteristics and estimated homicide mortality rate ratios and 95% CIs between pregnant or postpartum and nonpregnant, nonpostpartum victims for the total population and with stratification by race and ethnicity and age.

RESULTS:

There were 3.62 homicides per 100,000 live births among females who were pregnant or within 1 year postpartum, 16% higher than homicide prevalence among nonpregnant and nonpostpartum females of reproductive age (3.12 deaths/100,000 population, P<.05). Homicide during pregnancy or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy exceeded all the leading causes of maternal mortality by more than twofold. Pregnancy was associated with a significantly elevated homicide risk in the Black population and among girls and younger women (age 10–24 years) across racial and ethnic subgroups.

CONCLUSION:

Homicide is a leading cause of death during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the United States. Pregnancy and the postpartum period are times of elevated risk for homicide among all females of reproductive age.

For decades, research from single cities,1,2 states,3–10 and subnational geographies11–13 has identified homicide as a leading cause of death during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the United States. However, efforts aimed at preventing death in this population underemphasize homicide and intimate partner violence (IPV) as potential targets for public health intervention. Homicide and other violent causes are, by definition, not counted in estimates of maternal mortality,14 which fails to capture the totality of preventable death occurring among girls and women who are pregnant or in the postpartum period.

Until recently, data limitations have, in large part, contributed to the inadequate response and lack of accountability for both maternal mortality (defined as deaths while pregnant or within 42 days from the end of pregnancy from causes related to or aggravated by the pregnancy)14 and more broadly defined pregnancy-associated mortality (deaths during pregnancy and within 1 year postpartum from any cause).15 In an attempt to improve identification and surveillance of deaths occurring during pregnancy and postpartum, the 2003 revision to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death included a pregnancy checkbox to classify female decedents: not pregnant at time of death, pregnant, within 42 days, or 43 days to 1 year after pregnancy.16 However, state adoption of the 2003 revision was incremental, and it was not until 2018 that every state’s vital registration system included the pregnancy checkbox.

In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published the 2018 national maternal mortality ratio—17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births14—the first such reporting since the last official estimate 13 years prior. The purpose of this study was to analyze the first 2 years of nationally available data (2018 and 2019) and report the national prevalence of pregnancy-associated homicide. We hypothesized that pregnancy-associated homicide would exceed rates of mortality from leading obstetric causes of death, and that pregnancy and the postpartum period are times when girls and women are at increased risk of homicide.

METHODS

We obtained the 2018 and 2019 restricted use mortality files from the National Center for Health Statistics, which include a death record for every decedent in the United States. These data reflect the 2018 maternal mortality coding scheme developed and applied by the National Center for Health Statistics to mitigate misclassification of maternal deaths—errors previously arising from the pregnancy checkbox-based coding scheme.14 We first restricted the data to female decedents aged 10–44 years to further minimize bias caused by misclassification of pregnancy status among older women.17 Cases of pregnancy-associated homicide were decedents with a manner of death indicating homicide (from options including homicide, suicide, accident, natural, and unknown) or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) underlying cause of death code for assault (X85-Y09), in addition to a pregnancy checkbox value indicating the decedent was pregnant, within 42 days of pregnancy, or within 43 days to 1 year of pregnancy at the time of her death (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C453).

We used the World Health Organization’s ICD-10 underlying cause of death code group categories18 to identify direct maternal deaths occurring during pregnancy or within 42 days from the end of pregnancy for comparison with the magnitude of pregnancy-associated homicide occurring within the same timeframe. We explored this comparison first using the entire population of deaths and subsequently excluding those occurring in California, where data on timing of death relative to pregnancy do not differentiate the 42-day period, only that it occurred during or within 1 year.

Cases of nonpregnant, nonpostpartum homicide were those with a pregnancy checkbox indicating anything other than pregnant or within 42 days, or within 1 year of the end of pregnancy at the time of death and with manner of death indicating homicide or ICD-10 underlying cause of death code for assault.

In addition to age (10–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–44 years), we assessed decedent racial ethnic group (non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, and other) given previous evidence of racial inequity in pregnancy-associated homicide,19 and mechanism of injury, specifically firearm involvement (ICD-10 codes X93-X95). Death records do not include data on the victim–perpetrator relationship or IPV involvement. However, we characterized place of injury to document the proportion of homicides that occurred within the home (yes, no).

We ran chi square tests for bivariate associations between pregnancy status and age, race and ethnicity, mechanism, and place of injury. We estimated 2-year homicide mortality ratios (deaths/100,000 population) for the perinatal and nonpregnant, nonpostpartum populations separately, using the sum of live births in 2018 and 2019, and females aged 10–44 years minus live births (proxy for the nonpregnant, nonpostpartum population) as respective denominators. Data on live births by maternal characteristic were from the 2018 and 2019 National Center for Health Statistics natality files. Data on population aged 10–44 by race and ethnicity were from the American Community Survey 2018 and 2019 1-year national estimates.20 Finally, we estimated mortality rate ratios and 95% CIs to explore the degree to which pregnancy and the postpartum period is associated with risk of homicide for the total population, and with stratification by race and ethnicity and age, where cell sizes allowed. This analysis of deidentified, secondary data was ruled exempt by the Tulane University Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

From 2018 to 2019 there were 4,705 female homicide victims of reproductive age. Of these, 273 (5.8%) were pregnant or within 1 year from the end of pregnancy at the time of their deaths. Among pregnancy-associated homicide victims, most were non-Hispanic Black, and almost half were younger than age 25 years at the time of their deaths (Table 1). Approximately two thirds of the fatal injuries occurred in the home, and most involved firearms. Assault by sharp object and strangulation were the second and third most common mechanisms of injury. About half of the pregnancy-associated homicide victims were pregnant at the time of their deaths, and the other half within 1 year of the end of their pregnancies. Compared with nonpregnant, nonpostpartum victims of reproductive age, pregnant and postpartum decedents were significantly more likely to be non-Hispanic Black and of younger ages. Pregnancy-associated homicide was more likely to occur in the home. Fewer, but still a majority, of homicides in the nonpregnant, nonpostpartum population involved firearms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Female Homicide Victims Aged 10–44 Years in the United States, 2018–2019, by Pregnancy Status

| Characteristic | Pregnant or Within 1 y Postpartum (n=273) | Neither Pregnant Nor Within 1 y Postpartum (n=4,432) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total homicides | 273 (100) | 4,432 (100) | |

| Race and ethnicity | <.01 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 82 (30.0) | 1,621 (36.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 137 (50.2) | 1,812 (40.9) | |

| Hispanic | 26 (9.5) | 441 (10.0) | |

| Other* | 28 (10.3) | 558 (12.6) | |

| Age (y) | <.01 | ||

| 10–19 | 36 (13.2) | 628 (14.2) | |

| 20–24 | 97 (35.5) | 803 (18.1) | |

| 25–29 | 57 (20.9) | 841 (19.0) | |

| 30–34 | 49 (18.0) | 799 (18.0) | |

| 35–44 | 34 (12.5) | 1,361 (30.7) | |

| Time of death | |||

| Pregnant | 129 (50.9) | — | |

| Within 42 d from the end of pregnancy | 28 (10.3) | ||

| 43 d to 1 y from the end of pregnancy | 106 (38.8) | — | |

| Firearm involvement | .37 | ||

| No | 84 (30.8) | 1,481 (33.4) | |

| Yes | 189 (69.2) | 2,951 (66.6) | |

| Place of injury | <.01 | ||

| In the home | 173 (64.8) | 2,267 (53.6) | |

| Not in the home | 94 (35.2) | 1,965 (46.4) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Data-suppression rules prohibit further delineating persons in the Other category by race and ethnic group. Persons included in this category are decedents of all racial and ethnic identities other than Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and non-Hispanic Black.

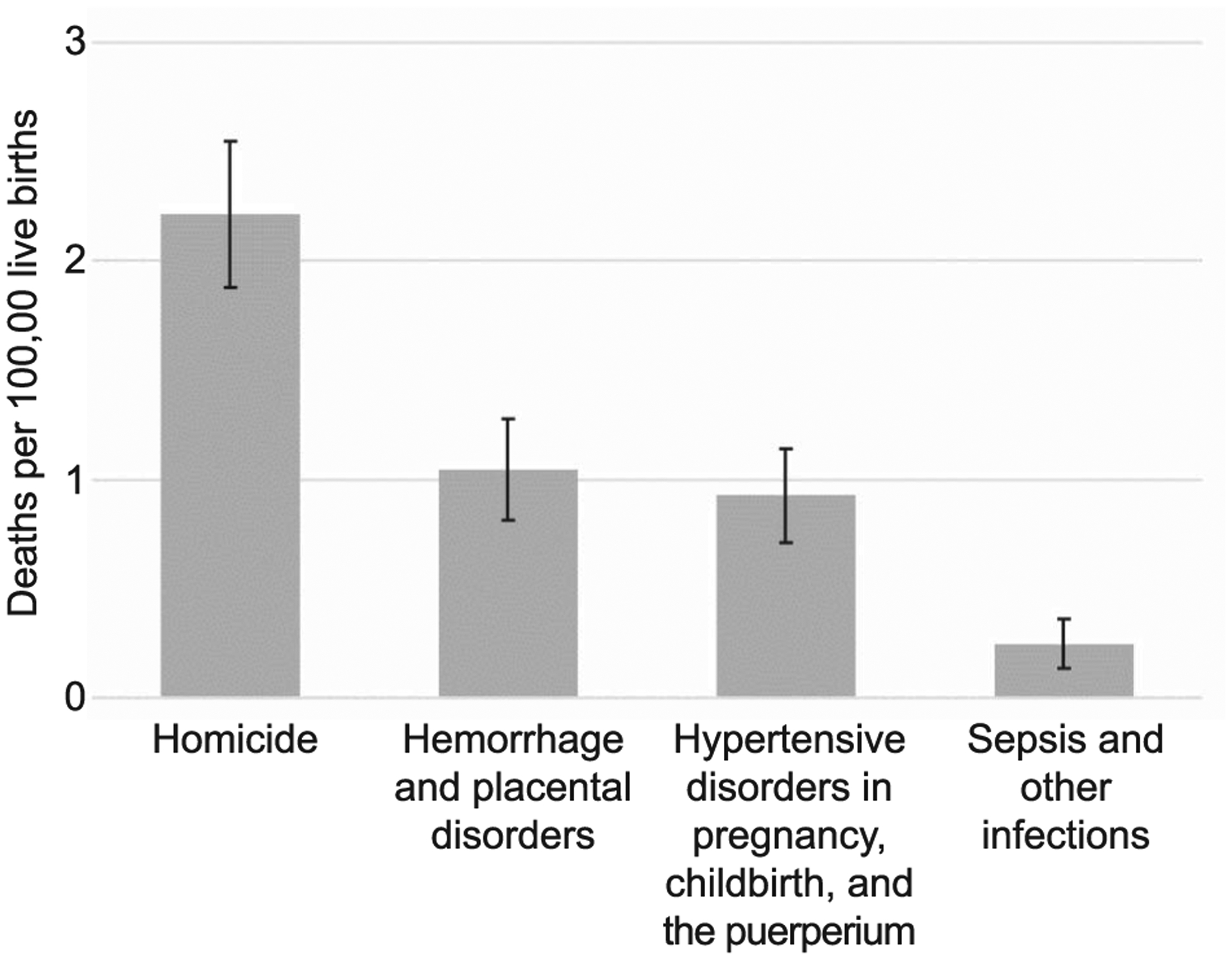

The 2018–2019 national pregnancy-associated homicide mortality ratio was 3.62 deaths per 100,000 live births (Table 2). Homicide mortality during pregnancy and within the first 42 days from the end of pregnancy (2.21 deaths/100,000 live births) exceeded all the leading causes of maternal mortality, including hypertensive disorders, hemorrhage, and infection, by more than twofold (Fig. 1). This pattern was consistent after excluding data from California such that homicide mortality remained twofold higher the leading obstetric causes of death (data not shown). Prevalence of pregnancy-associated homicide was highest among non-Hispanic Black females and females younger than age 25 years.

Table 2.

Homicide Mortality by Pregnancy Status and Victim Characteristics and Mortality Rate Ratios for Risk of Homicide Among Females in the Perinatal Period Compared With Nonpregnant, Nonpostpartum Females of Reproductive Age (10–44 Years) in the United States, 2018–2019

| Mortality Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Pregnant or Within 1 y Postpartum* | Neither Pregnant Nor Within 1 y Postpartum† | Mortality RR (95% CI) |

| Total homicides | 3.62 (3.19–4.05) | 3.12 (3.03–3.22) | 1.16 (1.03–1.31) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2.12 (1.66–2.58) | 2.12 (2.02–2.22) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.47 (10.38–14.56) | 8.95 (8.53–9.36) | 1.39 (1.17–1.66) |

| Hispanic | 1.46 (0.90–2.02) | 1.44 (1.31–1.57) | 1.01 (0.68–1.50) |

| Other‡ | 3.54 (2.23–4.85) | 3.84 (3.53–4.16) | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) |

| Age (y) | |||

| 10–19 | 10.12 (6.81–13.42) | 1.52 (1.40–1.64) | 6.67 (4.77–9.33) |

| 20–24 | 6.77 (5.42–8.11) | 4.09 (3.81–4.38) | 1.65 (1.34–2.04) |

| 25–29 | 2.61 (1.93–3.29) | 4.07 (3.79–4.34) | 0.64 (0.49–0.84) |

| 30–34 | 2.24 (1.61–2.87) | 4.04 (3.76–4.32) | 0.56 (0.42–0.74) |

| 35–44 | 2.46 (1.63–3.29) | 3.37 (3.19–3.55) | 0.73 (0.52–1.03) |

| Race-ethnicity and age (y) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | |||

| 10–24 | 4.05 (2.62–5.47) | 1.35 (1.23–1.48) | 2.99 (2.08–4.30) |

| 25–29 | 1.76 (0.99–2.54) | 2.52 (2.23–2.81) | 0.70 (0.44–1.10) |

| 30–44 | 1.58 (1.02–2.13) | 2.71 (2.53–2.88) | 0.58 (0.41–0.83) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | |||

| 10–24 | 21.09 (16.25–25.93) | 7.63 (7.05–8.21) | 2.77 (2.17–3.52) |

| 25–29 | 9.62 (6.28–12.95) | 11.93 (10.72–13.14) | 0.81 (0.56–1.16) |

| 30–44 | 7.63 (4.99–10.27) | 9.21 (8.56–9.85) | 0.83 (0.58–1.18) |

RR, rate ratio.

Deaths per 100,000 live births to females aged 10–44 years.

Deaths per 100,000 females aged 10–44 years minus live births to females aged 10–44 years.

Data-suppression rules prohibit further delineating persons in the Other category by race and ethnic group. Persons included in this category are decedents of all racial and ethnic identities other than Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and non-Hispanic Black.

Fig. 1.

Cause-specific mortality ratios (deaths/100,000 live births) and 95% CIs among females during pregnancy and up to 42 days from the end of pregnancy, United States, 2018–2019 (obstetric causes of death are World Health Organization ICD-10 underlying cause of death code group categories for direct maternal deaths18)

Homicide mortality among reproductive-aged females who were neither pregnant nor within 1 year postpartum was 3.12 deaths per 100,000 population. Among all females, risk of homicide was significantly higher among women who were pregnant and within 1 year postpartum compared with females of reproductive age who were neither pregnant nor postpartum (Table 2). Stratification revealed that pregnancy was associated with a significantly elevated risk of homicide among non-Hispanic Black females but not among other racial and ethnic groups. Pregnancy was associated with a more than sixfold increased risk of homicide among the 10–19-year age group and a 65% increase in risk in the 20–24-year age group. Patterns were similar in further stratification by both race and age such that pregnancy was associated with more than a doubled risk of homicide among girls and women aged 10–24 in both the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Universal implementation of the 2003 revision to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death has enabled this national analysis of violent death occurring during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The magnitude of pregnancy-associated homicide in the United States–3.62 deaths per 100,000 live births—is higher than previous estimates based on subnational groups of states: 1.7 in Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System data (1991–1999),11 2.9 among 16 states participating in the National Violent Death Reporting System from 2003 to 2007,12 2.9 among 17 states in the National Violent Death Reporting System from 2011 to 2015,13 and 2.2 among the 37 states with pregnancy checkbox data on death records from 2005 to 2010.21 Greater variation exists across estimates from single states, which have generally been higher, including 9.3 in Maryland (1993–2008),8 5.0 in Illinois (2002–2011),10 6.2 in North Carolina (2005–2011),22 and 12.9 in Louisiana (2016–2017).9 Globally, reported ratios per 100,000 live births are considerably lower, ranging from 0.39 in rural Bangladesh (1976–1993), 0.7 in Finland (1987–2000), and 0.97 in the United Kingdom (2015).23

Our finding that pregnancy may increase homicide risk is consistent with previous reports.9,10,21,24,25 Not only does the perinatal period appear to increase likelihood of experiencing violence, but a study on trauma victims in Pennsylvania found that injuries inflicted on pregnant females are more likely to be fatal.24 The consistency of these findings implicates health and social system failures. Although there have been longstanding recommendations for universal IPV screening during prenatal care visits,26 implementation has been inadequate at best27 and stigmatizing at worst (Paruchuri Y, Rajendran S, Chang J. Screening and counseling for intimate partner violence in pregnancy [abstract]. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:70S.). Moreover, lack of universal procedures for responding to positive screens in effective and nonpunitive ways means that opportunities for intervention are missed.

We found that increased risk for homicide conferred by pregnancy was most pronounced among younger women and among non-Hispanic Black girls and women. This finding is in line with recent work by Kivisto et al19 who found that, whereas rates of intimate partner homicide among females outside of the perinatal period were similar across White and Black populations, Black females had a pregnancy-associated intimate partner homicide rate more than three times higher than that of White females and more than eight times higher than that of nonpregnant Black females. Explanations for this social patterning of risk associated with pregnancy may include racial inequity in unintended pregnancy28 (which has been associated with intimate partner stress, conflict, and violence29,30), and racism within maternity care settings31,32 that may prevent girls and women from disclosing victimization and otherwise impede access to services, resources, and support. It is also evidence of the failure and indeed violence wrought on Black girls and women by systems purported to serve and protect them. Research has identified multiple ways in which medical, law enforcement, criminal justice, child welfare, and other social service systems responding to violence victimization perpetuate discriminatory treatment such that Black girls and women cannot or choose not to access services when needed or that services are inadequate and ineffective when they do.33–35

Although we are unable to directly evaluate the involvement of IPV in this report, we did find that a majority of pregnancy-associated homicides occurred in the home, implicating the likelihood of involvement by persons known to the victim. We were able to directly evaluate the role of firearms and found that nearly 7 of 10 incidents involved a firearm. This prevalence surpasses previously reported estimates—likely a reflection of the broader national increase in gun-related homicide occurring over the past decade36—and reaffirms firearms as the most common means of perpetrating pregnancy-associated homicide.8,13 States enacting laws that ban possession of firearms by perpetrators of domestic violence experience subsequent declines in IPV-related homicides.37,38 The same is likely true of trends in pregnancy-associated homicide.

This study has a number of limitations. Although death records are the only national source of data on violent maternal death, they are notably short of detail on victim characteristics and lack circumstantial information entirely. Data on victim–perpetrator relationship; IPV involvement; victim history of prenatal care; emergency or other health, criminal justice, and social service encounters; and the role of pregnancy itself in precipitating violence may be vitally important to the design of programmatic and policy interventions effective at preventing violent maternal deaths. The National Violent Death Reporting System provides substantially more information surrounding each incident than death records alone, via linkage to state and local medical examiner, coroner, law enforcement, and toxicology records.39 The National Violent Death Reporting System is not nationally representative, although an increasing number of states are participating,40 and so researchers should be encouraged to use these data to further our understanding of state-level policy and contextual features that may lead to violent maternal deaths. Additionally, coordination between state National Violent Death Reporting System programs and maternal mortality review committees could facilitate the use of these data during their discussion of cases involving violence. This enhanced review could be used to generate meaningful recommendations around prevention of pregnancy-associated homicide.

Second, universal adoption of the pregnancy checkbox is likely to enhance surveillance of pregnancy-associated homicide by allowing certifiers to indicate pregnancy status when known. Research on the validity of the checkbox for identifying decedent pregnancy status has raised concerns about its inclusion of both false-positives and false-negatives.41 However, in cases of homicide and other external causes of death, there remains probable underascertainment of such deaths on death records,42 for example, in cases in which the pregnancy is in its early weeks. We included all deaths where pregnancy status was unknown in the nonpregnant, nonpostpartum group. Our findings, therefore, are almost certainly underestimates of the true prevalence of pregnancy-associated homicide, which may be considerably higher. Increased awareness and training on the importance of the pregnancy checkbox among physicians, medical examiners, and coroners may improve the validity of vital records data for surveillance of pregnancy-associated death.41

Third, we have no data on the outcome of pregnancy to stratify decedents by those who experienced a live birth, miscarriage, or abortion within 1 year of their deaths. Homicide victims in the latter two groups may be less likely to be identified as cases of pregnancy-associated homicide than those with a live birth owing to the absence of systematically collected data on these outcomes. This would again result in an underestimation of pregnancy-associated homicide mortality in our study.

Finally, we combined 2 years of data to increase rate stability, but still small case numbers prohibited our further stratifying girls and women into more narrowly defined groups (women of other racial and ethnic groups, for example). Moreover, although we estimated 95% CIs around estimates, small case numbers warrants investigating homicide longitudinally or on a rolling basis to establish national prevalence of pregnancy-associated homicide over time and, most importantly, to accurately track progress towards its elimination.

Enhanced surveillance of maternal death has allowed us to confirm that homicide is a leading cause of death during pregnancy and postpartum in the United States. Although this is important information for monitoring progress towards the elimination of pregnancy-associated homicide, information alone will do nothing to save lives.43 Already, increasing efforts within individual states have been devoted to identifying and reviewing maternal deaths due to violence to make recommendations at individual, community, system, and policy levels for the prevention of future cases.44,45 Although encouraging, a commitment to the actual implementation of policies and investments known to be effective at protecting and the promoting the health and safety of girls and women must follow.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant number R01HD092653. The funding source had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. M Wallace had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Veronica Gillispie-Bell reports receiving funding from AbbVie, Inc., the Institute of Healthcare Improvement, and Lecturio GmBH. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fildes J, Reed L, Jones N, Martin M, Barrett J. Trauma: the leading cause of maternal death. J Trauma 1992;32:643–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dannenberg AL, Carter DM, Lawson HW, Ashton DM, Dorfman SF, Graham EH. Homicide and other injuries as causes of maternal death in New York City, 1987 through 1991. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172:1557–64. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90496-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons LH, Harper MA. Violent maternal deaths in North Carolina. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94:990–3. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00466-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harper M, Parsons L. Maternal deaths due to homicide and other injuries in North Carolina: 1992–1994. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:920–3. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00485-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sachs BP, Brown DA, Driscoll SG, Acker D, Ransil BJ, Jewett JF. Maternal mortality in Massachusetts. Trends and prevention. N Engl J Med 1987;316:667–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703123161105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horon IL, Cheng D. Enhanced surveillance for pregnancy-associated mortality–Maryland, 1993–1998. JAMA 2001;285: 1455–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jocums SB, Berg CJ, Entman SS, Mitchell EF Jr. Postdelivery mortality in Tennessee, 1989–1991. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91: 766–70. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00063-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng D, Horon IL. Intimate-partner homicide among pregnant and postpartum women. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:1181–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181de0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace ME, Crear-Perry J, Mehta PK, Theall KP. Homicide during pregnancy and the postpartum period in Louisiana, 2016–2017. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174:387–8. doi: 10.1001/jama-pediatrics.2019.5853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch AR, Rosenberg D, Geller SE; Illinois Department of Public Health Maternal Mortality Review Committee Working Group. Higher risk of homicide among pregnant and postpartum females aged 10–29 years in Illinois. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 128:440–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang J, Berg CJ, Saltzman LE, Herndon J. Homicide: a leading cause of injury deaths among pregnant and postpartum women in the United States, 1991–1999. Am J Public Health 2005;95:471–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.029868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, Flynn H, Gold KJ. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the national violent death reporting system. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:1056–63. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823294da [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace ME, Friar N, Herwehe J, Theall KP. Violence as a direct cause of and indirect contributor to maternal death. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2020;29:1032–8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.8072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoyert DL, Minino AM. Maternal mortality in the United States: changes in coding, publication, and data release. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2020;69:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossen LM, Womack LS, Hoyert DL, Anderson RN, Uddin SFG. The impact of the pregnancy checkbox and misclassification on maternal mortality trends in the United States, 1999–2017. Vital Health Stat 3 2020:1–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mac KAP, Berg CJ, Liu X, Duran C, Hoyert DL. Changes in pregnancy mortality ascertainment: United States, 1999–2005. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:104–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821fd49d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis NL, Hoyert DL, Goodman DA, Hirai AH, Callaghan WM. Contribution of maternal age and pregnancy checkbox on maternal mortality ratios in the United States, 1978–2012. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:352.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium: ICD-MM. Accessed December 10, 2020. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/9789241548458/en/

- 19.Kivisto AJ, Mills S, Elwood LS. Racial disparities in pregnancy-associated intimate partner homicide. J Interpers Violence 2021. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1177/0886260521990831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2019: ACS 1-year estimates subject tables. Accessed November 1, 2020. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=sex%20by%20age&-tid=ACSST1Y2019.S0101

- 21.Wallace ME, Hoyert D, Williams C, Mendola P. Pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide in 37 US states with enhanced pregnancy surveillance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:364.e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin AE, Vladutiu CJ, Jones-Vessey KA, Norwood TS, Proescholdbell SK, Menard MK. Improved ascertainment of pregnancy-associated suicides and homicides in North Carolina. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:S234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cliffe C, Miele M, Reid S. Homicide in pregnant and postpartum women worldwide: a review of the literature. J Public Health Pol Jun 2019;40:180–216. doi: 10.1057/s41271-018-0150-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deshpande NA, Kucirka LM, Smith RN, Oxford CM. Pregnant trauma victims experience nearly 2-fold higher mortality compared to their nonpregnant counterparts. Am J Obstet Gynecol Nov 2017;217:590.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dietz PM, Rochat RW, Thompson BL, Berg CJ, Griffin GW. Differences in the risk of homicide and other fatal injuries between postpartum women and other women of childbearing age: implications for prevention. Am J Public Health 1998;88: 641–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.4.641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Intimate partner violence. Committee Opinion No. 518. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:412–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318249ff74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halpern-Meekin S, Costanzo M, Ehrenthal D, Rhoades G. Intimate partner violence screening in the prenatal period: variation by state, insurance, and patient characteristics. Matern Child Health J 2019;23:756–67. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2692-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374:843–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yakubovich AR, Stockl H, Murray J, Melendez-Torres GJ, Steinert J, Glavin CEY, et al. Risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence against women: systematic review and meta-analyses of prospective-longitudinal studies. Am J Public Health 2018;108:e1–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception Mar 2009;79:194–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLemore MR, Altman MR, Cooper N, Williams S, Rand L, Franck L. Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Soc Sci Med Mar 2018;201:127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehra R, Boyd LM, Magriples U, Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR, Keene DE. Black pregnant women “get the most judgment”: a qualitative study of the experiences of Black women at the intersection of race, gender, and pregnancy. Womens Health Issues 2020;30:484–92. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs ER. How our service systems impact resiliency and recovery of domestic violence survivors: clinical perspectives. Accessed December 2, 2020. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/1895

- 34.Tillman S, Bryant-Davis T, Smith K, Marks A. Shattering silence: exploring barriers to disclosure for African American sexual assault survivors. Trauma Violence Abuse 2010;11:59–70. doi: 10.1177/1524838010363717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bent-Goodley TB. Health disparities and violence against women: why and how cultural and societal influences matter. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007;8:90–104. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fridel EE, Fox JA. Gender differences in patterns and trends in U.S. homicide, 1976–2017. Violence Gend 2019;6:27–36. doi: 10.1089/vio.2019.0005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeoli AM, McCourt A, Buggs S, Frattaroli S, Lilley D, Webster DW. Analysis of the strength of legal firearms restrictions for perpetrators of domestic violence and their associations with intimate partner homicide. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187:2365–71. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diez C, Kurland RP, Rothman EF, Bair-Merritt M, Fleegler E, Xuan Z, et al. State intimate partner violence-related firearm laws and intimate partner homicide rates in the United States, 1991 to 2015. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:536–43. doi: 10.7326/M16-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National violent death reporting system. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/datasources/NVDRS/index.html

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National violent death reporting system state profiles. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nvdrs/stateprofiles.html

- 41.Catalano A, Davis NL, Petersen EE, Harrison C, Kieltyka L, You M, et al. Pregnant? Validity of the pregnancy checkbox on death certificates in four states, and characteristics associated with pregnancy checkbox errors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020; 222:269.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horon IL, Cheng D. Effectiveness of pregnancy check boxes on death certificates in identifying pregnancy-associated mortality. Public Health Rep 2011;126:195–200. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bridges K Racial disparities in maternal mortality. NYU Law Rev 2020;95. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koch AR, Geller SE. Addressing maternal deaths due to violence: the Illinois experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217: 556.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benno J, Trichilo R, Gillispie-Bell V, Lake C. Louisiana pregnancy-associated mortality review 2017 report. Accessed 2021, Jan 20. https://ldh.la.gov/assets/oph/Center-PHCH/Center-PH/maternal/2017_PAMR_Report_FINAL.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.