Abstract

Objectives:

Healthcare coding and billing are an important aspect of practice management that directly impacts the financial stability of a health care practice. To financially sustain or grow a medical practice, it is imperative that resident and faculty physicians have knowledge and skills for accurate billing in every patient encounter.

Methods:

A systematic review was conducted to identify recently published studies that report on improvements in medical coding and billing accuracy, clinical documentation, and reimbursement rate. A search of three databases yielded a total of 5754 records. After screening, 41 records were sought for retrieval and a total of 18 records were obtained for review.

Results:

Following a thorough review of literature, the most common reasons for inaccurate or inappropriate billing were a lack of formal education within residency curriculum, inadequate clinical documentation supporting level of billing, and lack of a feedback system aimed to correct billing errors.

Conclusion:

A formal education curriculum implemented in training could enhance knowledge and application of accurate billing and coding and further benefit practice longevity. The purpose of this systematic review is to apply knowledge gained to the development and implementation of a quality improvement study intended to improve accuracy of coding and billing within an academic pediatric outpatient center.

Keywords: General pediatrics, billing, coding, reimbursement, documentation

Introduction

In medical practice today, there is a higher demand on physicians to see more patients, provide enhanced complex medical services, and complete detailed documentation efficiently. This leaves little time for the process of billing and coding. Yet, medical coding and billing are a critical component of daily practice that determine financial stability as well as legal compliance of a medical establishment. In an outpatient practice, accurate coding and billing are essential because it provides the main source of income for the medical practice. 1 Coding and billing become even more significant within an academic center where resident physicians are increasingly responsible for appropriate medical record documentation which helps to ensure appropriate coding and billing for each patient encounter.

Guidelines for coding and billing using the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) are set forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2 The current process of coding and billing set forth by CMS relies on evaluation and management (E&M) codes which permit insurance companies to provide a fee for service reimbursement approach. Many private insurance companies adhere to the same guidelines set forth by CMS. As part of these guidelines, appropriate documentation is a requirement of CMS and plays a crucial role in practice effectiveness in coding and billing.

The cost of health care is an undeniably expensive endeavor for providers, consumers, and insurers. In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that personal health expenditures in the United States reached US$3.0 trillion, a 3.8% increase from 2016. Of the US$3.0 trillion, 38.6% was spent on inpatient hospitalization, while physician services and clinical services accounted for 23.4%. 3 The health care expenditure was further analyzed by payer type. It was found that 35.1% of the total cost was paid by private insurance, 22.3% paid by Medicare, 17.6% paid by Medicaid, 12.3% paid by out-of-pocket, and the remaining paid by other types of insurance/payers. 3 The CDC also provides 2018 estimates on health insurance coverage type among children under 18 years of age, with 36% being covered by Medicaid, 54.7% covered by private insurance, and 5.2% were uninsured. 3 As seen, Medicare and Medicaid make up a sizable portion of payer source in healthcare. From a physician point of view, there are significant risks associated with inaccurate coding and billing such as lost revenue, legal investigations, and potential exclusion from government sanctioned programs such as Medicaid and Medicare. 4 Incorrect upcoding or downcoding can lead to penalties as severe as federal penalties and even imprisonment. Yet, there is still a lack of educational curriculum on coding and billing.

To compare effective strategies for improvement in appropriate medical coding and billing within academic outpatient medical practice, a systemic review of previous literature is crucial. Although there are multiple studies evaluating reasons for inappropriate coding and billing as well as looking at methods on attempts to improve coding and billing within outpatient clinical settings, a systemic comparison of these strategies is lacking. Such systemic comparison can bring to light sources leading to inappropriate coding and billing as well as provide insight into effective methods for outpatient medical practice to enhance accuracy of coding and billing. The purpose of this systematic review is to identify effective strategies to improve medical coding and billing practices within an outpatient academic medical practice setting.

Methods

Information sources

A search of available literature for articles assessing healthcare coding and billing was conducted using multiple databases including PubMed, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) journal Pediatrics, and Marshall University Health Science Library research database (MU Summons). Databases were last accessed on 23 August 2020. In addition, website sources including CDC, CMS, and CMS website (CMS.org) were used. Websites were last accessed on 29 August 2020. The search was initially confined to published literature with specified dates between August 2015 through August 2020 to capture the most recent literature. The search was then expanded to include literature published in January 2000 onward to include more literature articles.

Search strategy

The following search terms were used within each database: “medical coding AND billing,” “billing reimbursement,” “medical billing AND resident,” and “billing AND coding AND outpatient.” The CDC website was used to search “health care utilization statistics within the United States.” Resources were entered into Mendeley software and screened for duplicates. All duplicates were removed. Titles were screened for relevance to the topic.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: focused on improvement strategies for outpatient billing and coding, provided assessment of accuracy of coding and billing in outpatient clinics, provided assessment of physician or resident knowledge of billing and coding, included resident educational curriculum on coding and billing, assessed the impact of medical documentation on billing and coding, and assessed legality and/or legal ramifications of coding and billing. Studies were excluded based on the following exclusion criteria: the study took place in a setting other than an outpatient clinical setting, included procedure or procedural coding and billing, the full-text article was not accessible, or the study results were inconclusive. Only full-text articles available for download were reviewed.

Literature selection

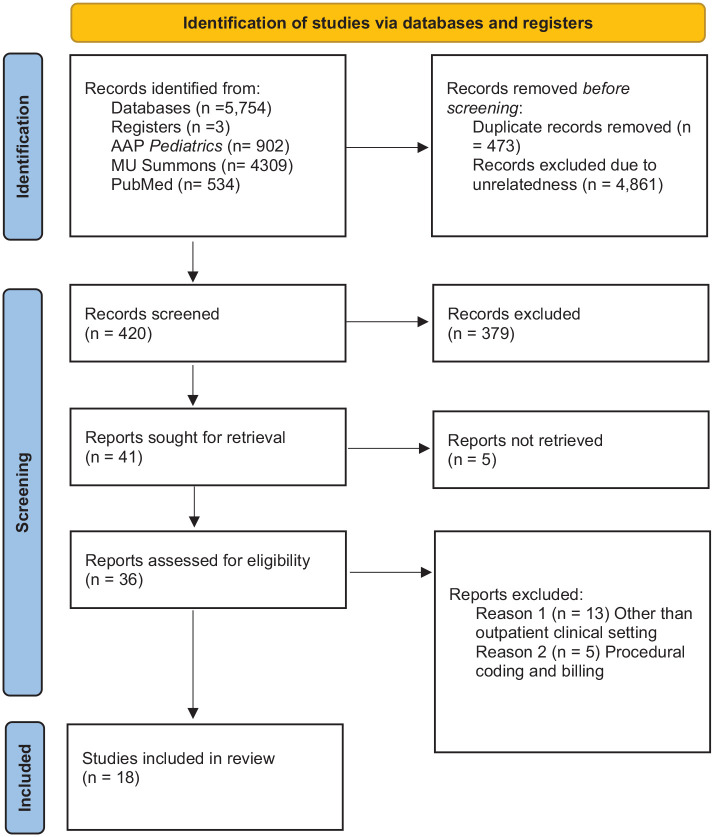

A thorough search of the literature was undertaken. Figure 1 provides a PRISMA flowchart detailing the step-by-step process used to generate the final number of studies selected for this review. After filtering publications for the detailed inclusion criteria, a total of forty-one publications were sought for review, of which, five were inaccessible. This provided 36 full-text articles for review. Of these, 18 publications were found to contain information relevant and applicable to the proposed quality improvement project.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart showing the step-by-step process of selection including inclusion and exclusion criteria to generate the final number of studies for analysis in this systematic review of coding and billing in the outpatient setting.

Data collection process

Data were collected by an independent researcher who performed data search, data review, and data selection. Data were entered into Mendeley software for analysis and tracking.

Statistical analyses

This is a systematic review; therefore, we did not perform statistical analyses.

Results

In researching the literature, there were multiple reoccurring issues that affect the accuracy of coding and billing within medical practice. First, there is a lack of formal coding and billing curriculum within residency, fellowship, and post-training years. Second, there is a need for complete and efficient documentation within the electronic health record (EHR). There is also the need for legal compliance and implementation of strategies for improvement with the medical practice. Table 1 provides a summarization of the origin, purpose, research design, and results of each study reviewed.

Table 1.

Literature on billing and coding summarized by author, origin, study purpose, study design, and results.

| Authors | Origin | Purpose | Research design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cawse-Lucas et al. 1 | The United States | To investigate the impact of Medicare Primary Care Exception (PCE) on resident coding practices. | A survey sent to Family Medicine (FM) residency program directors in a five-state region. The percentage of high-level codes was compared between residents and attendings using the chi-square analysis. Data from 125,016 visits from 337 residents and 172 faculties in 15 eligible FM residencies were analyzed. | Attending physicians coded higher level visits. The estimated revenue lost was 2558.66 per resident and 57,569.85 per year for the average residency in their sample. |

| Adams et al. 4 | The United States | To recommend an approach for assessing potential risk, preventing improper billing, and improving financial management of a medical practice. | Lays out a training module for physicians. | E&M guidelines are updated periodically, and coding practices need to be updated accordingly to reflect new guidelines. |

| Adiga et al. 5 | The United States | To determine “perceived, desired, and actual knowledge” of Medicare billing and reimbursement among internal medical (IM) residents compared with community IM generalist. | Survey of community and university PGY-2 IM residents from four

geographical regions in the United States assessing: 1. Self-awareness. 2. Ability to correctly answer billing questions. |

Participants disagree with the statement that they receive enough training about Medicare and agree that reimbursement should be taught. Residents scored significantly lower than general IM physicians on actual knowledge. Primary care track residents scored significantly lower on actual knowledge test than did categorical residents. |

| Al Achkar et al. 6 | The United States | To assess the variation in billing patterns between resident and attending physicians considering provider, patient, and visit characteristics. | Retrospective cohort of established patient visits in outpatient FM clinic over 5 years. Used logistic regression methodology to identify variation and used Poisson’s regression to test sensitivity. A total of 116 residents and 18 attendings were reviewed. | After review, residents were shown to bill higher E&M codes less often when compared to attendings for comparable visits. |

| Andreae et al. 7 | The United States | To assess recent pediatric graduates’ views on training for billing and coding during training. | National survey using AAP national database. 1200 generalist pediatricians and 1100 subspecialists were selected to receive a survey which asked them to rate their impression of the adequacy of their training program in teaching billing and coding. | Response rate was 76% for generalist and 77% for subspecialty. A total of 81% of generalist and 78% of subspecialist respondents indicated they could have used additional training in billing and coding. |

| Arora et al. 8 | The United States | To assess AAP pediatric trainee’s thoughts about time spent documenting and need for education in billing and coding. | Pediatric residents and fellows who are members of AAP Section of Pediatric Trainees were sent a survey via email and hosted on Google Forms. Responses based on the Likert scale (1–5). There were 601 respondents. | A total of 62% of respondents had no prior training in billing and coding. A total of 263 respondents were involved in billing and coding of which 75% of respondents were not comfortable with billing and coding. Three out of four agreed billing/coding techniques should be part of medical education. |

| Austin and von Schroeder 9 | Ontario, CA | To compare surgical resident and staff physicians on billing knowledge as well as explore experiences and opinions regarding billing and coding education during residency training. | Both groups completed 10 hypothetical scenario-based clinical billing assessments graded by professional billing experts. Responses were scored as correct (most appropriate), underbilled, overbilled, or incorrect. Post-test survey. Small sample size: 16 residents and 17 staff physicians at one center. | Staff physicians scored higher percentage correct on billing codes, underbilled codes, and had fewer missed billing codes. On the post-test survey, 100% residents and 79% physicians wanted additional education. |

| Faux et al. 10 | Australia | Attempt to systematically map all avenues of education on Medicare billing and compliance in Australia and explore perception of teaching medical billing. | National cross-sectional survey assessing percentage of programs offering education course on billing. Sample size n = 57. | There was an 86% response rate with 70% stating they did not offer a course on billing. Remaining 30% offered a course, but 71% of these courses were vocational education providers. Survey concluded there was a lack of qualified educators and education is largely taught by medical practitioners rather than qualified educators who have expertise in administrative and legal aspects of Medicare. |

| Ghaderi et al. 11 | The United States | To improve billing and coding in surgical residency outpatient practice. | A total of three separate 20-min didactic sessions were held prior to regular conference. One year pre-intervention compared to 1-year post-intervention. | They found an increase in higher level coding and billing accuracy comparable to national average post-intervention. |

| Varacallo et al. 12 | The United States | To assess a group of orthopedic residents’ knowledge on documentation, billing, and ability to identify Medicare fraud. | Voluntary participation from two separate residency programs; n = 32. Residents completed a baseline assessment followed by a 45-min lecture, followed by post-test. Each resident asked to self-rate documentation and coding comfort level on Likert (1–5) scale. | Level of comfort increased with increasing post-graduate year (PGY); however, there was no difference in baseline scores on pre-test between junior and senior residents. The lecture significantly improved knowledge as assessed by the post-test. |

| Waugh 13 | The United States | QI project to improve knowledge of billing within neurology residency and fellowship training. | Pre-intervention in which resident documentation and billing were analyzed. Followed by an intervention implementing dedicated curriculum to improve accuracy of documentation and coding. Implemented documentation tools. Analysis of resident documentation and billing for 15 months after initiation of intervention. | Pre-intervention: 56% of trainee-generated outpatient encounter notes had insufficient documentation to support level of billing. Study progressively eliminated note devaluation and increased mean level billed by US$34,313 per trainee per year. |

| Kapa et al. 14 | The United States | To develop an instrument for billing in IM resident clinics, to compare billing practices among different resident levels, and to estimate financial losses from inappropriate resident billing. | A total of 100 random patient notes were assessed and scored by three different coding specialists, and billing codes were converted to US$ based on Medicare reimbursement list. | A total of 55% of assessed notes were underbilled by an average of US$45.26 per encounter, and 18% were overbilled by US$51.29 per encounter. The percentage for appropriate coding was 16.1% for PGY-1, 26.8% for PGY-2, and 39.3% for PGY-3. |

| O’Donnell and Suresh 15 | The United States | Provide a policy statement from AAP on clinical documentation, direct future research and development for electronic media to improve health care delivery, and address challenges for efficient and effective documentation in pediatrics. | This policy statement provides recommendations for advocacy for development and advancement of pediatric electronic health records (EHR) functionality. | The needs of child health care documentation differ from adults, yet there has not been a defining EHR documentation for pediatric populations. There is a market for EHR development, however, because children represent a small percentage of overall healthcare usage, it may be difficult to engage vendors in pediatric-specific projects and EHR enhancement. |

| Caskey et al. 16 | The United States | To examine how the transition to ICD-10-CM may result in ambiguity of clinical information and financial disruption for pediatricians. | ICD-9-CM codes were obtained from IL Medicaid for 1 year (2010) and were mapped to ICD-10-CM codes. Mappings were examined by pediatricians for clinical accuracy and financial analysis of findings conducted. | The diagnosis codes represented by information loss (3.6%), overlapping categories (3.2%), and inconsistency (1.2%) represented 8% of Medicaid pediatric reimbursement. This could translate to potential financial and administrative errors which necessitates attention to coding when transitioning to ICD-10-CM. |

| Chung et al. 17 | The United States | To summarize the payer structure including CHIP, discuss the process by which radiologists receive reimbursement, explain process of using ICD-10-CM codes, and explore coding-related issues specific to pediatric radiology. | Explains payers of services, billing process, documenting clinical necessity of imaging services, use of ICD-10-CM codes, documenting imaging services provided, requesting reimbursement, and finally, the unique challenges for reimbursement in pediatric radiology. | Pediatric radiologists can improve coding accuracy and enhance revenue through proper documentation of clinical necessity and detailed description of the services provided with an understanding of the components required for correct billing. |

| Bala and Shelburne 18 | The United States | To reduce the average monthly number of missed charges within two pediatric neurology clinics by 50% within 6 months. | Pre-intervention: looked at a 3-month period, 1255 encounters at

two clinic sites. Intervention: 1. Electronic billing was mandated. 2. A formal tracking and feedback mechanism was created to educate providers about their own missed charges and facilitate accountability. Feedback was provided every 1–2 weeks via email. Providers could measure their own performance against de-identified peers. |

At the beginning, the department was missing an average of 91 charges per month. A total of 25% of charges were created late or not at all. Denial of payment or non-payment resulted in US$9831.33 lost revenue per month. Post-intervention missed charges were reduced by more than 50% over a 6-month period to 26 missed charges per month. |

| Nguyen et al. 19 | The United States | To implement a longitudinal method for teaching billing and coding within an FM residency. | Pre-test and post-test combined with monthly coding learning sessions implemented within academic curriculum. | There was no improvement in coding accuracy rates from baseline from didactic teaching. |

| Chiu et al. 20 | The United States | To focus on opportunities for changes in state Medicaid programs resulting from the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. | Policy recommendations focus on the areas of benefit coverage, financing and payment, eligibility, outreach and enrollment, managed care, and QI. | Regardless of state variations in participation in the ACA Medicaid expansion, Medicaid will remain as the largest single insurer of children. Governmental health policy on both state and federal levels has not adequately met the needs of children; however, the AAP has developed a framework to readdress these deficiencies to enhance care and outcome. |

QI: quality improvement; AAP: American Academy of Pediatrics; ICD-10-CM: International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; ACA: Affordable Care Act.

A lack of education, training, and feedback

The literature indicates that a high rate of physician coding error can be attributed to inadequate training within residency and fellowship training.5–13 Multiple studies used survey analysis to assess physician and resident perspectives on adequacy of education in billing and coding during training years. These studies found that residents and attendings alike felt education was inadequate and additional training in coding and billing was needed.5,7,8,10 In a study by Arora et al., 8 a total of 263 AAP trainees responded to a survey stating they were actively involved in billing and coding; however, 75% reported they did not feel comfortable with the process.

Lack of education within training years was also made apparent in a study by Kapa et al. 14 who assessed billing practices among different level residents within an internal medicine residency. Of 100 random patient clinical encounter visits scored by three separate coding specialists, the percentage of accurate coding was 16.1% for post-graduate year (PGY)-1, 26.8% for PGY-2, and 39.3% for PGY-3. Underbilling decreased as residents advanced; however, the amount of overbilling increased. 14

Although attending physicians oversee resident clinical education and provide mentorship, one retrospective cohort study comparing 116 residents and 18 attending physicians billing patterns over a 5-year period found that residents billed for higher level codes less often than attending physicians for comparable established patient visits. 6 Another study looking at 125,016 patient clinical encounters from 337 resident and 172 faculty physicians found similar results. This study again showed that residents do not bill established patient encounters at the appropriate level that is generally acceptable and attending physicians billed more high-level codes. 1

Consequences of insufficient documentation in billing

Documentation is required by CMS and has been adopted by most clinics and hospitals in the United States. O’Donnell and Suresh 15 emphasize the importance of having specific documentation guidelines as they are imperative to the workflow and functionality of the EHR systems in pediatric care. In addition, this manuscript points out that the Office of Inspector General puts the responsibility for accurate billing squarely on the provider. Providers cannot abdicate this duty by over reliance on EHR tools or coding staff.

Documentation should effectively communicate the clinical picture while also accurately reflecting the extent and quality of medical services provided, “if it is not in the medical records, it did not happen.” 4 Failure of the physician to appropriately document the necessary components in the medical record could result in improper coding and erroneous billing.

In Caskey et al., 16 International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes were obtained for 1 year (2010) and mapped to ICD-10-CM. This study found that diagnosis codes represented by information loss (3.6%), overlapping categories (3.2%), and inconsistency (1.2%) represented 8% of Medicaid pediatric reimbursement. Adequate documentation and accurate coding are used to measure quality, predict clinical outcomes, and anticipate future needs by health care systems. 16

Chung et al. 17 discuss medical coding and billing in pediatric radiology. This study points out that improper documentation and coding can lead to patients’ families receiving unexpected and unnecessary bills that could cause financial hardships. 17

Legal compliance to ensure reimbursement

Adams et al. 4 explain that the Department of Justice, Attorney General, and Medicaid Fraud Units have implemented methods to detect and investigate providers who submit false claims. They also described two types of reported false claims, “erroneous claims” and “fraudulent claims.” Erroneous claims have been redefined by CMS to reassure providers that innocent billing mistakes will not be targeted for investigations; however, a pattern of erroneous claims will be subjected to investigation. Fraudulent claims are defined as applications for reimbursement that have reckless intention to collect payment for services not provided. The article goes on to list eight high-risk activities of fraudulent billing. One common high-risk activity is termed “upcoding” and is defined as billing for more expensive services than what is actually provided. 4

Strategies for improvement in billing

There were multiple articles that studied interventional methods for improving knowledge and accuracy of coding and billing.4,11–14,18,19 Adams et al. 4 emphasize the importance in auditing and monitoring medical documentation, billing, and coding practices on a routine basis as a strategy to lessen billing errors and achieve compliance within a practice. In addition, this article points out that E&M guidelines change frequently, and it is important for the physician to stay up-to-date on these changes in order to support proper documentation for accurate coding and billing. 4

A study by Ghaderi et al. 11 focused on implementing three separate 20-min didactic sessions prior to conference over a period of 1 year. The simple intervention resulted in improved documentation for E&M and generation of higher billing codes by residents. 11 The study was limited by a small sample size. A study that contrasts this method found that didactic teaching sessions implemented within an academic curriculum did not improve coding accuracy comparing pre-test scores to post-test scores. 19

A quality improvement project by Waugh 13 implemented a dedicated curriculum that included tools to assist in efficiency and accuracy of documentation. Following a 15-month intervention period, there was improvement in clinical documentation and the average level billed increased by US$34,313 per trainee per year. 13 Another quality improvement study by Caskey et al. 16 implemented two interventions which included mandating the use of EHR and implementation of a formal feedback system to educate providers on their missed or inaccurately billed charges. Over a 6-month post-intervention period, missed charges were reduced by more than 50% and an estimate of US$75,000 per year revenue was rescued. 18 This study points out one of the challenges faced in ongoing feedback can be the lack of an employee with the job description/position dedicated to this role; therefore, the responsibility for training and feedback should be designated. In addition, it is emphasized that leadership must be committed to provider accountability for timely, accurate billing. Finally, the need for an emphasis on trainee compliance with timely documentation is noted to be important as faculty must wait for the note from the trainee before they can provide attestation and submit billing.

A few studies made suggestions on improvement strategies but did not formally study the strategy. One study by Austin and von Schroeder 9 suggested implementing a seminar series taught by senior staff mentors and outside consultants to senior residents and fellows. A study by Faux et al. 10 conducted a national cross-sectional survey in Australia exploring perception of teaching of medical billing. This study found that only 30% of programs offered billing education, but of these, 71% of education was taught by vocational or post-graduate general practitioners and not billing specialists. The study therefore stated a formal national medical billing curriculum for medical physicians should be encouraged. 10 Although outside the United States, this study exemplifies the need for specialized education in billing and coding within training to enhance level of provider comfort.

In addition to the literature, it was found that the CMS website provides online courses for general medical coding knowledge. These online courses are offered through the Medicare Learning Network.

Discussion

During the clinical years of residency, education is directed at generating independent-practicing physicians with adequate medical knowledge in their chosen specialty. However, little time is spent on education in coding and billing necessary for practice management. Within the literature, there is limited evidence to suggest wide-spread acceptance of a formal educational curriculum or a billing mentor within residency, fellowship, or post-training practice. There was a common feeling of unpreparedness and unfamiliarity with coding and billing concepts among all levels including residents, fellows, and post-training practitioners.5–8 Without formal training, clinical encounters can be coded and billed inaccurately and repetitively, resulting in destructive consequences for a medical practice.

The literature reinforces the importance of adequate documentation for each patient encounter within the EHR coding. Documentation is not only an essential part of patient care that provides a method for various health care providers to share pertinent patient information but also an important driver of proper coding and billing. If documentation is missing components that directly relate to the level of coding, there is potential for the billing claim to be denied, resulting in loss of reimbursement. 17 In addition, complete documentation provides a means to measure quality of care, predict clinical outcomes, and anticipate future patient needs. 16 Due to concerns about potential fraud with upcoding, 4 physicians may be inclined to under code. However, this should be avoided as it is actually fraud as well, in addition to having profound financial ramifications.

Due to time constraints within the office, some physicians rely on professional coding and billing staff to process patient medical claims and never review their billing forms. 4 This practice prevents learning through feedback which was found as an effective method to improve accuracy. 18 It also allows for missed charges or inaccurate billing as the physician is the legally responsible coder 15 and the main driver of documentation, coding, and billing. They were present in the clinical encounter as opposed to the billing staff member who was not. This results in lost revenue for the practice. Therefore, implementing a feedback system may prevent recurrent billing errors and increase practice revenue by helping claim lost revenue. As noted by Bala and Shelburne, 18 lack of a designated person to do this feedback can be a problem. It seems building a system that promotes a close association between billing and coding staff and providers and defines specific responsibilities would address this issue.

It is also important to think about population served. Medical reimbursement fees differ among coverage types. Chiu et al. 20 note the Medicaid fee-for-service schedule and reimbursement payments to primary care physicians and subspecialty providers is substantially lower compared to that paid by private insurance companies. Therefore, accurate coding and billing ensures adequate repayment for all payer types and prevents claim denial resulting in lost revenue.

There are multiple studies looking at coding and billing quality improvement.4,11–14,18,19 From these studies, it is apparent that implementation of an educational component is necessary to close gaps in knowledge and provide physicians with confidence in coding and billing patient encounters. Several strategies including implementation of didactic sessions, a formal feedback and corrective system, pre- and post-test evaluation with formal lecture series, and documentation tools all positively correlated with an increase in accuracy of billing and/or increased revenue.

Limitations

We did not identify any risk of bias in our review as data were collected by an independent researcher and followed a step-by-step process. However, possible limitations exist at the retrieval level since those articles which did not have full-text accessibility were not included. This resulted in the loss of five out of the forty-one publications which met other inclusion criteria. Finally, we also included some studies outside the United States which weakens our conclusions since Australia and Canada have different billing systems than our country. We do think the principles of needing formal education applies to either system.

Conclusion

The literature supports a need for a formal education curriculum aimed at teaching residents, fellows, and general physicians’ accurate methods of coding and billing in addition to adequate clinical documentation. Failure to comply with documentation guidelines and submission of recurrent erroneous or fraudulent medical claims could have catastrophic consequences and result in dismissal from government-funded medical reimbursement programs. There were several studies within the literature that looked at the implementation of strategies aimed to improve coding and billing accuracy. From this knowledge, a quality improvement study can be designed to expectantly improve coding and billing practices within a pediatric academic outpatient practice.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Susan Flesher  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3208-7097

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3208-7097

References

- 1. Cawse-Lucas J, Evans DV, Ruiz DR, et al. Impact of the primary care exception on family medicine resident coding. Fam Med 2016; 48(3): 175–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Center for Health Statistics N. ICD-10-CM official guidelines for coding and reporting FY 2020, 2019–2021, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/10cmguidelines-FY2020_final.pdf

- 3. Center for Health Statistics N. Health, United States 2018 chartbook. Health, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/hus_infographic.htm

- 4. Adams DL, Norman H, Burroughs VJ. Addressing medical coding and billing: part II—a strategy for achieving compliance a risk management approach for reducing coding and billing errors. J Natl Med Assoc 2002; 94(6): 430–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adiga K, Buss M, Beasley BW. Perceived, actual, and desired knowledge regarding Medicare billing and reimbursement: a national needs assessment survey of internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21(5): 466–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Al Achkar M, Kengeri-Srikantiah S, Yamane BM, et al. Billing by residents and attending physicians in family medicine: the effects of the provider, patient, and visit factors. BMC Med Educ 2018; 18(1): 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andreae MC, Dunham K, Freed GL. Inadequate training in billing and coding as perceived by recent pediatric graduates. Clin Pediatr 2009; 48(9): 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arora A, Garg A, Arora V, et al. National survey of pediatric care providers: assessing time and impact of coding and documentation in physician practice. Clin Pediatr 2018; 57(11): 1300–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Austin RE, von Schroeder HP. How accurate are we? A comparison of resident and staff physician billing knowledge and exposure to billing education during residency training. Can J Surg 2019; 62(5): 340–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Faux M, Wardle J, Thompson-Butel AG, et al. Who teaches medical billing? A national cross-sectional survey of Australian medical education stakeholders. BMJ Open 2018; 8(7): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ghaderi KF, Schmidt ST, Drolet BC. Coding and billing in surgical education: a systems-based practice education program. J Surg Educ 2017; 74(2): 199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varacallo MA, Wolf M, Herman MJ. Improving orthopedic resident knowledge of documentation, coding, and Medicare fraud. J Surg Educ 2017; 74(5): 794–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Waugh JL. Education in medical billing benefits both neurology trainees and academic departments. Neurology 2014; 83(20): 1856–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kapa S, Beckman TJ, Cha SS, et al. A reliable billing method for internal medicine resident clinics: financial implications for an academic medical center. J Grad Med Educ 2010; 2(2): 181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O’Donnell H, Suresh S. Electronic documentation in pediatrics: the rationale and functionality requirements. Pediatrics 2020; 146(1): e20201682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Caskey R, Zaman J, Nam H, et al. The transition to ICD-10-CM: challenges for pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2014; 134(1): 31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chung CY, Alson MD, Duszak R, Jr, et al. From imaging to reimbursement: what the pediatric radiologist needs to know about health care payers, documentation, coding and billing. Pediatr Radiol 2018; 48(7): 904–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bala TR, Shelburne J. Improving billing compliance within a pediatric neurology department. Pediatrics 2018; 141: 123–123. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nguyen D, O’Mara H, Powell R. Improving coding accuracy in an academic practice. US Army Med Dep J 2017(2–17): 95–98, https://ezproxy.southern.edu/login?qurl=http%3A%2F%2Fsearch.ebscohost.com%2Flogin.aspx%3Fdirect%3Dtrue%26db%3Dmnh%26AN%3D28853126%26site%3Dehost-live%26scope%3Dsite [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chiu T, Hudak ML, Snider IG, et al. Medicaid policy statement. Pediatrics 2013; 131(5): e1697–e1706. [Google Scholar]