Abstract

Introduction:

Health care workers who work daily with human body fluids and hazardous drugs are among those at the highest risk of occupational exposure to these agents. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogens Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030) prescribes safeguards to protect workers against health hazards related to bloodborne pathogens. Similarly, the United States Pharmacopeia General Chapter 800 (USP <800>), a standard first published in February 2016 and implementation required by December 2019, addresses the occupational exposure risks of health care workers at organizations working with hazardous drugs. With emerging technologies in the field of gene therapy, these occupational exposure risks to health care workers now extend beyond those associated with bloodborne pathogens and hazardous drugs and now include recombinant DNA. The fifth edition of the Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) and the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH Guidelines) mostly govern work with biohazardous agents and recombinant DNA in a laboratory research setting. When gene therapy products are utilized in a hospital environment, health care workers have very few resources to identify and reduce the risks associated with product use during and after the administration of treatments.

Methods:

At the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, a comprehensive gap analysis was executed between the research and health care environment to develop a program for risk mitigation. The BMBL, NIH Guidelines, World Health Organization Biosafety Manual, OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, and USP <800> were used to develop a framework for the gap analysis process.

Results:

The standards and guidelines for working with viral vector systems in a research laboratory environment were adapted to develop a program that will mitigate the risks to health care workers involved in the preparation, transportation, and administration of gene therapies as well as subsequent patient care activities. The gap analysis identified significant differences in technical language used in daily operations, work environment, training and education, disinfection practices, and policy development between research and health care settings. These differences informed decisions and helped the organization develop a collaborative framework for risk mitigation when a gene therapy product enters the health care setting.

Discussion:

With continuing advances in the field of gene therapy, the oversight structure needs to evolve for the health care setting. To deliver the best outcomes to the patients of these therapies, researchers, Institutional Biosafety Committees, and health care workers need to collaborate on training programs to safeguard the public trust in the use of this technology both in clinical trials and as FDA-approved therapeutics.

Keywords: gene therapy, biosafety, gap analysis, risk mitigation, health care workers

Introduction

Gene therapy involves altering the genes inside cells in an attempt to treat or stop disease. 1,2 Similarly, cell therapy is the use of cells that are taken either from the patient themselves or a donor to treat diseases. Stem cells are often used for cell therapy that can mature into different types of specialized cells. 1,2 The cells that are used for cell therapy may or may not be genetically altered. In most cases, it is easier to remove cells from the body, treat them with gene therapy, and then place them back than treating the cells inside the body. This is the case for gene therapy for blood disorders. Therefore, both gene and cell therapy often go together. 3 -5

As of 2020, more than 2900 gene therapy clinical trial studies have been initiated worldwide. 3,4,6 A search in the ClinicalTrials.gov webpage with the keywords “gene therapy” resulted in more than 4255 studies, with more than 1000 currently recruiting or enrolling research participants. 3- 6 Bracing for a massive upsurge in the development of cell and gene therapies, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) expects to receive up to 200 new applications every year from 2020 to start trials. 3,4,6 The FDA also expects to be approving 10 to 20 cell and gene therapies every year from 2025, reflecting a turning point in the development of these technologies and their application to human health. 3,7

The FDA issued its first recombinant DNA product approval in 2015 and has since approved 6 more products, the most recent being Zolgensma in May 2019. 3,6 With 291 gene therapy studies currently in Phase III clinical trials (with up to 3000 participants), several more gene therapy products will likely be considered for approval in the coming years. 3,4,7 Most of these gene therapy products are viral vector system based. 1,3,8 These viral vector systems offer the potential for efficient gene delivery and can act as a vital tool or vehicle to treat genetic disease. 9 -12

Viral vector systems for gene therapy are promising treatment options for diseases such as metabolic, cardiovascular, muscular, hematologic, ophthalmologic, and infectious diseases and different types of cancer. 1,13 However, some viral vector systems remain risky and are still under study to ensure safety and efficacy during clinical trials. 6 Viruses used for gene delivery systems include retrovirus, adenovirus, adeno-associated viruses, and herpes simplex viruses. 2,14 Additionally, vector types represent both RNA and DNA viruses with either single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds) genomes. 14,15 The choice of viral vector systems for clinical use depends on the efficiency of transgene expression, ease of production, toxicity, safety, and stability. 15,16

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Recombinant DNA Guidelines and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Laboratory Biosafety Manual categorize all infectious agents into 4 risk groups for laboratory research. 17,18 The risk group informs the level of containment needed to minimize risk during the handling of these infectious agents as designated by its biosafety level (BSL). 17 -19 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WHO, and NIH have published recommendations for work at different biosafety levels (BSL-1–BSL-4) for wild-type virus and viral vector handling in a laboratory research setting. 18 -20 As with risk group classification, biosafety levels differ by viral vector systems. Historically, institutional biosafety committees (IBCs) have been responsible for reviewing any risks associated with viral shedding and insertional mutagenesis during the protocol review process for work in a research laboratory setting 21 or utilization within a clinical research trial. However, IBC oversight becomes difficult once these products enter the health care environment or are approved by the FDA as therapeutic products.

Biosafety structure and oversight, in the form of regulations, policy, guidelines, and other governance strategies, are continuously challenged to keep pace with the ever-evolving complex landscape of biomedical research. 22,23 Although the current guidelines are vital tools for performing thorough risk assessments in a laboratory setting, challenges arise when the gene therapy products enter the health care setting. Because health care settings have no consensus guidelines for working with viral vector systems or gene therapy products, to mitigate and minimize risk and exposure during therapeutic use, a comprehensive risk assessment framework is needed to develop these recommendations/guidelines. The current article is the first to perform a comprehensive gap analysis to identify the differences between the research and health care environments when using a gene therapy product or viral vector systems. Additionally, we discuss how gap analysis results improved the biosafety program management at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (NCH). We anticipate that the strategies outlined here will serve as a guideline for other organizations developing a risk assessment framework and may help to meet institution-specific regulations and requirements. With the continued growth in the field of gene therapy, health care professionals need to familiarize themselves with the prospects, risks, and regulatory requirements for working with gene therapy products.

Methods

Gap Analysis at NCH

Gap analysis was conducted to compare the current state of work processes in the research and health care environment when working with viral vector systems and gene therapy products. The primary guidelines for comparison between these settings included NIH recombinant DNA guidelines, fifth edition of the Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), WHO Laboratory Biosafety Manual, Occupational Safety and Health Administration Laboratory Safety Guidance, CDC Healthcare Infection Control Guidelines, and United States Pharmacopeia General Chapter 800 (USP <800>). These guidelines were reviewed during this process to glean risk mitigation policies and procedures. The research safety team met with researchers from different centers employing the viral vector systems for gene therapy experiments in a laboratory environment as well as with physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and nurse educators who worked/administered these gene therapy products (clinical trials and FDA approved) in the health care environment. The objective was to ascertain the different approaches currently used for risk assessment/risk mitigation and training in these environments. The research safety team reviewed all of the current practices and further refined the selection and description of the core practices in these areas to identify the significant differences in the core practices between the 2 environments (research and health care). These differences were evaluated to develop a uniform program for risk mitigation when these products enter the health care setting.

Results

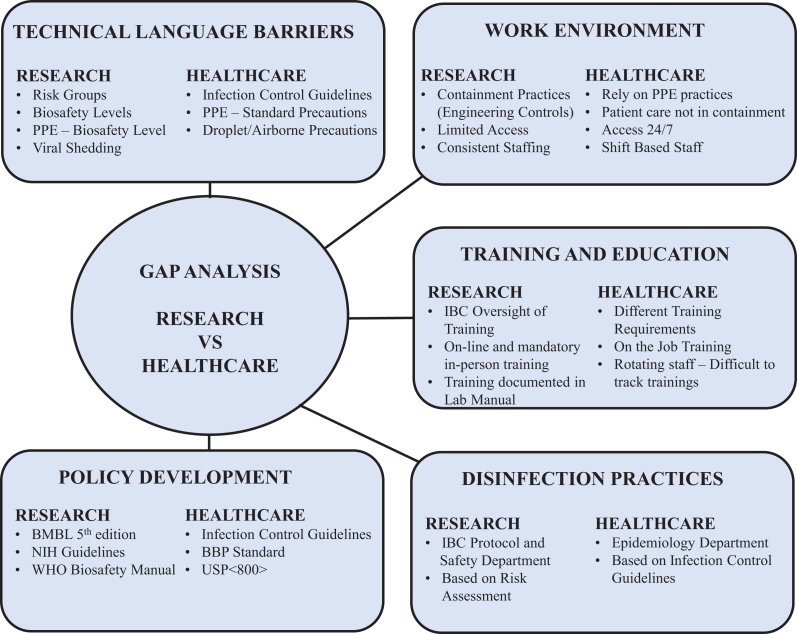

The gap analyses provided a snapshot of gaps in 5 significant areas between the research and the health care settings: technical language barriers, work environment, training and education, disinfection practices, and policy development (Figure 1). These 5 areas served as the basis for prioritizing our current program management and practices to develop a common framework of risk assessment and mitigation.

Figure 1.

Gap analysis outlining the differences between research and health care environments.

Technical Language Barrier

During the gap analysis, the first and foremost difference observed was related to differences in the technical language used in the research and the health care setting. The terms such as “BSL” and “risk groups” commonly used in a research environment are not typical in the hospital areas. Not only were most RNs unfamiliar with these terms, but when it came to the use of viral vector systems in gene therapy in the health care setting, they were unaware of the terminology “viral shedding” and the potential associated risks.

Additionally, in the hospital areas, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) was based on standard precautions with additional transmission-based precautions. Staff also used personal risk assessment to determine what was needed for specific patient care activities in which contact with blood and body fluids is likely to occur. The risks associated with the administration of gene therapy products and subsequent patient care activities were new concepts to most of the staff. In the laboratory setting, the BSLs dictate the PPE requirements. In contrast, patient rooms were not marked with BSL designations outside, nor were the doors required to have a biohazard symbol or other hazard communication signage.

Similarly, the terms used in the health care setting were foreign to many working in the research setting. Some terminology associated with infection control practices, which include standard precautions, transmission-based precautions, hand hygiene, and sterile injection practices, were unfamiliar to staff working in the research setting. For example, it may not be immediately evident to a nonclinical employee about the PPE restrictions when “droplet precautions” are in place, whereas this may be crystal clear to an individual in the clinical environment.

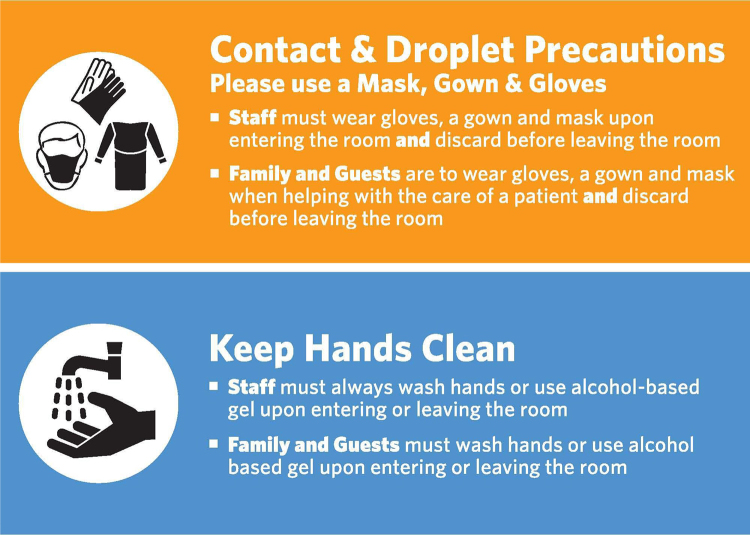

Gap analysis identified differences with technical language barriers in the research and health care settings at NCH, which helped establish procedures to overcome many of the associated hurdles. The collaboration of the research safety team with the epidemiology department in the hospital helped develop infection control policies that captured the terminologies of BSL, risk groups, and viral shedding commonly used in the research environment. The epidemiology department developed a PPE matrix that captured the biosafety practices used to mitigate hazards associated with the use of the viral vector systems and gene therapy products in research. The PPE guidelines used existing infection control terminology to adopt similar levels of precaution for clinical staff working with viral vectors as those used in research when working at BSL-2 based on risk assessment. Similarly, standardized signage was developed for staff and visitors and posted outside rooms of patients who were administered gene therapy products. These hazard communication signs convey information related to entry requirements and other safety considerations to staff and visitors (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Current practices utilized for hazard communication and personal protective equipment requirements in hospital patient areas.

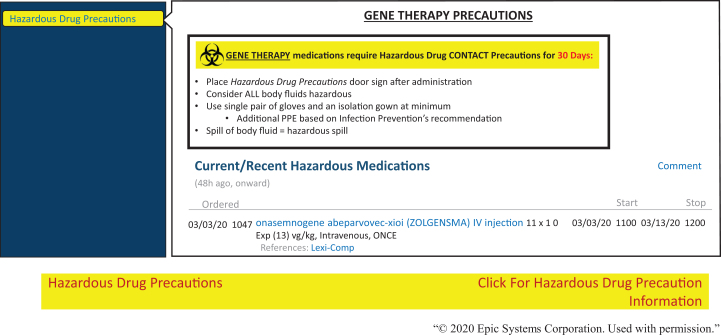

Similarly, the research safety team worked with epidemiology department to develop a training program to overcome some of the technical language barriers related to biosafety in the clinical environment. The training covered topics related to the basic biosafety principles, risks, safety, and shedding associated with the administration of viral vector systems/gene therapy products. All staff now have required training in interpreting biosafety and PPE requirements when working with viral vector systems/gene therapy products in the patient areas. Additionally, we recently started creating flags and banners in the electronic medical record (EMR) software (Epic Systems Corporation) to display relevant information about hazardous drugs. These flags were expanded to include viral-mediated gene therapy products. The banner is brightly colored to capture the attention of care providers viewing the chart (Figure 3). Rolling over the banner with the cursor opens more detailed notes regarding the precautions to be taken and the duration for which precautions are to be observed. Leveraging this technology makes this information widely available to all service providers in the hospital network. For example, when a child treated with a gene therapy product is scheduled for physical therapy (eg, within 1-2 weeks of administration), the physical therapist will also have this information, increasing awareness of the precautions required during and after a session. Banner notes inform about viral shedding periods and that higher level disinfection practices will be required after therapy sessions. Additionally, recommendations for appointments at a particular time of the day help reduce exposure risks to other patients.

Figure 3.

Current practices utilized for risk mitigation in clinical areas to flag patients receiving gene therapy products. The figure outlines gene therapy precautions that need to be followed by the hospital staff for a patient receiving ZOLGENSMA.

Work Environment

The gap analysis also identified significant differences in the work environment and practices between research and health care settings. Unfortunately, research containment practices are not feasible for all activities in the patient care setting. In research, most work with viral vector systems is performed using engineering controls (eg, biosafety cabinets). 24 Containment practices are not practical when these products are administered to a patient. After administration of gene therapy product, appropriate administrative controls are mostly implemented to prevent exposure of staff and family members to biohazards (eg, body fluids, shed virus, etc).

In the hierarchy of controls, research laboratories rely heavily on engineering controls for containment to provide a safe work environment. For example, all work that generate aerosols with the viral vector systems is done in a biological safety cabinet (BSC). Similarly, in a research setting, there is always an effort to minimize the use of sharps. In a clinical setting, the use of sharps and safer sharps are also evaluated and minimized when practicable; however, the use of sharps is often unavoidable for certain procedures. Additionally, all the research laboratories have specific ventilation requirements (negative pressure), compared to hospital patient areas where specific ventilation requirement is based on risk assessment. Meanwhile, the patient care environment is a step down on the hierarchy of controls and mostly relies on work practices and PPE to control hazards at the bedside. For example, transmission-based precautions are designed to protect staff and families who will be in direct contact with patients after the administration of a gene therapy product. In a children’s hospital setting, parents will often take up residence in the room with their child for the duration of their stay. Additional considerations for exposure must also be made for who is allowed for visitation or if there are other patients within the same area. In general, we require siblings or those who may also be candidates for the same treatment to be separated from the patient.

Additionally, the organization of the laboratory work environment is fundamentally different from a hospital inpatient unit. Research laboratories are usually staffed with employees who work on the same projects for their duration of stay. It is a relatively small span of control for the principal investigator (PI) or lab manager of a research laboratory. Much of the work in a research laboratory can be planned to be done during regular working hours, with some variation for time points and other unique study requirements. In contrast, hospital units are staffed by multiple departments working multiple shifts to provide patient care 24 hours a day. Not only may staff assignments vary from day to day, but float-staff and even contract workers may also be temporarily assigned to a unit on short notice, especially when short-staffed.

NCH currently addresses some of these critical differences in the work environment between research and health care settings with the following measures. Pharmacists manipulate all viral vectors systems or gene therapy products using engineering controls (eg, BSC). Similarly, when these products are administered to the patient, exposure to the product is minimized by using closed-loop delivery systems whenever possible. First, the patients receiving these products are scheduled onto specific units of the hospital to minimize the risks associated with viral shedding and exposure. The staff members in these units are required to complete the training on viral vectors systems. They are also required to employ specific disinfection practices during the stay and after the discharge of treated patients. In the clinical research setting, patients administered with gene therapy product may be returning for follow-up while potential candidate patients of gene therapy products may be visiting on the same day. In this type of outpatient setting with shared restrooms and multiple visits in the same rooms, disinfection practices are strictly followed to limit exposure of potential study participants to shed virus. Although the risk of seroconversion from contact with patients dosed with any gene therapy product is not available, caregivers and health care professionals are informed about how theoretically, seroconversion may limit the efficacy of future gene therapy treatment. 25 Recommendations are provided to families through the informed consent process to consider sequestering patient siblings from the treated patient to reduce the potential for exposure resulting in immunity to the viral vector. 25

In research laboratories, there is always an effort to minimize the use of sharps, and safer alternatives are used whenever possible. A thorough risk assessment related to sharps use is part of the protocol review by the IBC committee. Additionally, the research safety team is involved in risk assessment at the individual laboratory level. However, the use of sharps in a clinical environment is unavoidable given that pharmacists are required to prepare doses of gene therapy products or clinicians are required to administer products. At NCH, guidance for the use of safer sharps and nonsharp alternatives in the clinical environment are outlined in the Infection Control Policy on Safe Injection, Infusion, Medication Vial, and Point of Care Testing Practices as well as the Exposure Control Plan. The policies governing the use of sharps at NCH are in accordance with the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, 29 CFR 1910.1030, 26 and most of the risks associated with the use of sharps are mitigated at the procedure level based on these guidance documents by the departments. Additionally, the employee safety team evaluates all incidents related to sharps use at NCH. This team works with the supply chain as well as individual departments to propose alternative products and practices to reduce sharps-related injuries.

To address issues with rotating staff assignments, float-staff coming from different departments, we have implemented a Just-in-Time training document. This 1-page document goes to all staff on the patient unit before the administration of the gene therapy product. This training format has proven beneficial in refreshing the knowledge of current employees considering that the time from initial training on the risks associated with the viral vector systems/gene therapy products to the time the staff member may care for a gene therapy patient varies. Moreover, this document helps to capture and train any employees or rotating fellows that may have recently transferred to the unit.

Despite the substantial number of clinical gene therapy trials that have been conducted worldwide, a summary of actual human viral shedding data is currently unavailable for the different viral vector systems. Peer-reviewed publications, which outline shedding data of different viral vector systems when administered to human research subjects, are also limited. 24 Most investigator brochures and product inserts of FDA-approved gene therapy products recommend 30-day universal or standard precautions. 25,27 Based on the limited viral-shedding data, we generally recommend contact precautions with patient material for 30 days postadministration for both health care staff and direct family members (Figure 2). 25 This recommendation is also flagged in the EMR software (Epic Systems Corporation), which our organization currently uses for patient data (Figure 3). Furthermore, instructions are provided to family members and caregivers to practice good hand hygiene for a minimum of 30 days after the injection. 25 Good hand hygiene requires washing hands with soap regularly and using appropriate protective gloves if coming into direct contact with the patient’s bodily fluids and waste. 25

Training and Education

One major area that most organizations with both laboratory research and health care environments struggle with is the administration and assessment of training programs for staff competency that work with biohazardous agents. Before working with biological agents in a laboratory setting, all research staff at the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at NCH must complete an extensive training program (in-person and online modules). Training by the PI or their designee on specific standard operating procedures must also be documented after completion in the online TrainingTracker software.

However, when a gene therapy product or viral vector systems enters the health care setting, the clinical staff do not function under the same training expectations. Translating a successful training program from the research setting to the hospital poses additional challenges due to the differences in the work environment and reporting structures of the different teams operating in the clinical space. Each department in the hospital has a different method for training and measuring competency. The patient care setting relies on a system of nurse educators who are responsible for in-service training, distribution of organization-specific policies and procedures, and maintaining the professional competencies required for the job. Support staff such as patient care assistants, nutrition services, or environmental services mainly rely on an initial orientation by their supervisor, online modules, and then on-the-job training by their staff. Similarly, physicians have new information passed to them through their section chiefs, or they are required to attend skills-based programs or gain expertise through clinical observations or simulations.

Due to the diverse training requirements in moving from the research to the health care environment, we have used a learning management system (LMS) to administer and track all the required trainings for work with gene therapy/viral vector products. The LMS allows us to assign curriculum as appropriate to staff working in particular functions or on specific units. For clinical staff, we developed an in-house gene therapy training module that covers topics related to risk groups, biosafety levels, viral shedding, and exposure/emergency responses.

In many cases, within 48 hours of gene therapy product administration, the patient can go home. When these patients return home, the family members assume patient care activities. Despite leaving the hospital, these patients may still be shedding the virus. At NCH, we have developed a Take-Home Letter and a document called Helping Hands guide, which serve as references for precautions for the family to follow at home or to share with visitors. Additionally, wallet-sized cards with similar information to inform outside providers on the associated risks with patient contact are also provided to families. We recommend the patient’s family to follow contact precautions for waste handling for at least 30 days postadministration. Furthermore, the research safety team works proactively with employee health services to strategize possible exposure responses to the gene therapy products/viral vector systems in use in the research, clinical research, and health care settings.

Disinfection Practices

Disinfection practices and products may vary between laboratory and clinical environments. In the laboratory research environment, disinfectant practices are dictated by the approved IBC protocol, as outlined by the PI. However, in the hospital setting, all disinfection practices are dictated by the epidemiology department. This department also approves certain disinfectants for use in clinical environments. Premade disinfectants and/or wipes are more common in a health care environment, and health care staff are not permitted to make the disinfectant solutions (eg, 10% bleach or 70% alcohol) that are commonly found in research labs. Regulatory documents or published peer-reviewed guidelines do not exist that dictate standard disinfection practices for all possible viral vector systems currently used in human gene therapy research. 24 In an attempt to streamline the disinfection practices across our organization, the research safety team collaborated with the epidemiology department on disinfectant practices and products suitable for gene therapy products/viral vector systems. The disinfection practices and products for gene therapy products and viral vector system at NCH are outlined in the Infection Control Policy maintained by epidemiology and are followed in both research and clinical environments to avoid confusion.

The current procedures are based on the risks associated with each viral vector system. For example, susceptibility to virucidal agents varies because some viral vectors are enveloped and some have only a proteinaceous capsid. We require all patient areas to use only the approved products (Table 1) that meet the definition of intermediate-level disinfectants. Consideration is also given to the compatibility of different disinfection products with the materials present in the patient room. For example, some disinfectants may damage medical equipment, and to avoid potential issues, we consult with the biomedical engineering department of our organization before use. Future studies must evaluate the effectiveness of other disinfectants on different viral vector systems that can be potentially used for human gene therapy research. Currently, there is limited data that validate disinfection practices in a clinical setting when it comes to viral vector systems.

Table 1.

The Intermediate-Level Disinfectants Approved for Use with Viral Vector Systems or Approved Gene Therapy Products.a

| Intermediate-Level Disinfectants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Product | Description |

Contact Time

Wet Time |

| Clorox Healthcare bleach germicidal cleaner, spray or wipe | Active ingredient: 0.55% sodium hypochlorite (equivalent to a 1:10 bleach solution) | 3 min |

| PDI Sani-Cloth AF3 germicidal disposable wipe | Active ingredients: quaternary ammonium compounds Does not contain fragrance, alcohol, bleach, acid, phenol, acetone, or ammonia. Only available in a wipe; if a Quaternary Ammonium spray is needed, the approved product is Virex Tb RTU. |

3 min |

| Metrex Cavicide spray or CaviWipes | Active ingredients: isopropyl alcohol (17.2%) and ammonium chloride Only approved for hospital use if equipment IFU requires it. Bleach free |

3 min |

| Clorox Healthcare hydrogen peroxide cleaner disinfectant spray or wipe | - Active ingredient: 1.4% hydrogen peroxide | Wipes: 5 min Spray: 4 min |

| Diversity Virex Tb ready-to-use disinfectant cleaner spray | - Active ingredients: quaternary ammonium compounds | 10 min |

Abbreviation: IFU, manufacturer’s instructions of use.

a Alcohol is not an effective disinfectant against adeno-associated virus and adenovirus.

Policy Development

The NIH recombinant DNA guidelines and the fifth edition of the BMBL offer the general framework of working with viral vectors and are often used as a reference for risk assessment for human gene transfer research. 6,19,20 In the clinical setting, the CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Guidelines and OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogen Standard recommend safeguards to protect workers against health hazards related to infectious material. 28 Similarly, USP <800> describes the practice and quality standards for handling hazardous drugs to promote patient safety, worker safety, and environmental protection. 29 However, standard documents for conducting a comprehensive risk assessment do not exist for viral vector systems used in gene therapy in the health care setting. Moreover, FDA-approved products are exempt from IBC purview, so in the absence of a defined oversight, individual organizations must develop their own policies and procedures.

In the health care setting, the people who may potentially be exposed to gene therapy products include but are not limited to pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, nurses, physicians, physician assistants, patient care assistants, housekeeping staff (environmental services), and family members. So we took a systematic approach for developing policies that were relevant to the diverse team that handles gene therapy products (clinical trials and FDA approved). This approach involved collaboration between pharmacists, epidemiology, research safety, environmental services, clinical research teams, and physicians/nursing staff to develop procedures that can be adapted to both research and hospital environments.

For example, the infection control policy of our organization has specific PPE guidelines for work with materials of human origin. A PPE matrix designed for exposure determination and prevention is included in the NCH Infection Control Policies. This PPE matrix specifies requirements for hand hygiene, gloves, fluid-resistant gowns, as well as eye and face protection specific to patient care activities. For gene therapy products, this PPE matrix is based on risk assessment for each viral vector or trial. We use the EMR system to communicate the PPE requirements based on risk assessment for each trial or gene therapy product (Figure 3). We generally recommend contact precautions with patient material for 30 days postadministration for both health care staff, which is reflected in the EMR software (Figure 3). This list has been expanded to provide information about laboratory practices involving work with potentially infectious material. Similarly, USP <800> guidelines were adapted to develop a procedure for hazardous drug disposal for the hospital and the research setting. These policies take into consideration the risk group and the biosafety level of each viral vector, including the potential risk associated with the encoding transgene. It was determined that employing a systematic approach in policy development prevents duplication of efforts and encourages standard practices throughout the organization. A standard format was adopted for all organizational policies to facilitate staff in reading and retaining information as well as scanning documents later for specific guidelines and rules. All health care organizations can significantly benefit in the area of policy development for work with viral vectors systems in human gene therapy research if more relevant guidelines for a health care environment are included in BMBL or other regulatory documents in the future.

Discussion

Gene therapy is an area of intense focus in the biotech industry right now, with so many treatments in progress and several recent approvals. Much of gene therapy’s recent success can be attributed to considerable advances in the viral vector technologies used to deliver the genetic material to patients’ cells. The safe use of viral vector systems in human gene therapy is a significant concern in the clinical setting because there is no single document that summarizes the guidelines of working with them. Additionally, IBCs are being asked to extend their influence beyond the academic research laboratory and into the health care environment, often for the first time. As a result, most organizations develop their own policies and procedures for gene therapy handling and administration. However, the key to the development of policies and appropriate handling procedures for gene therapy products is establishing relevant collaboration across the organization’s departments. Because pharmacists, nurses, and physicians all handle the gene therapy product once it enters the clinical setting, organizations need to involve these people in the policy and standard operating procedure development process. In our organization, we met with all the departments that handle gene therapy products. We learned about their processes so that a common framework of training and risk mitigation could be developed. The collaboration among departments for risk mitigation is what helped us achieve the best outcomes for the children who receive these treatments.

The revised NIH guidelines highlight the critical role of IBCs in reviewing gene therapy research studies. The NIH guidelines, Section III-C, now require IBCs to undertake a review of safety risks at the level of the investigators’ institutions (e.g., universities and research centers) for all forms of human gene therapy research. 6 This highlights the need for IBCs to collaborate with other compliance committees for providing oversight of gene therapy research and ensuring compliance with education, training, risk assessment, and institutional policies. However, for FDA-approved gene therapy products, IBC review or approval is not required. So, it is critical for IBCs of organizations that have a hospital associated with it to work and collaborate with departments, centers, and committees having oversight over patient safety and employee safety to ensure safe administration of gene therapy products. IBCs play an important role in aiding the development of policies and procedures to protect both patients and employees and contributing to the risk assessment process when evaluating a vector and transgene. At NCH, the PIs at the research institute are involved in the gene therapy centers of the hospital. The communication between these PIs, IBC, epidemiology, and safety has resulted in the development of practices that reduce the risk to patients and staff. Such collaboration is also critical for research organizations that do not have a hospital associated with it. It is critical for biosafety professionals in these areas to identify risk level and develop policies related to gene therapy product administration predominantly in the absence of consensus framework for the risk assessment process for viral vector systems and communicating them to their PIs.

Our current program is not perfect, and we continue to focus on ongoing challenges. Not all departments have efficient and effective methods of distributing training. We still struggle to ensure we have informed all of the physicians who may provide care to patients receiving gene therapy treatment. Physicians have a different training methodology and are not necessarily required to complete training modules in the LMS, as is the case with other staff. Additionally, last-minute staffing changes continue to pose challenges in training administration. The Just-in-Time documents that we use do serve as a minimum guideline to anyone present on the unit, but there is still room for improvement with training processes.

Our organization benefits considerably by having the research and hospital departments’ collaboration on policies and for procedural development to achieve best outcomes. However, as the number of clinical trials with viral vector systems or FDA approved biologicals increase, health care systems without the advantage of an academic research program will be struggling to implement appropriate safety training without a common regulatory document or just based on product insert information (FDA-approved products). With the approval of more FDA gene therapy products and without IBC oversight, more organizations should consider developing a risk-based program for the administration of these products. Now is a unique time in the evolution of our ability to treat disease using biological agents, and increased collaboration and understanding between health care systems and biosafety professionals will be essential in providing health care workers appropriate tools, training, and resources to safely administer the treatments of tomorrow.

Conclusions

In this report, we outline a program for overcoming some of the biosafety challenges associated with the administration of gene therapy products in a health care setting. Health care professionals have a critical role in the proper handling of gene therapy products, identifying risk levels, establishing training programs, and developing policies in the absence of consensus guidelines for the handling and administration of gene therapy products in a clinical environment. Where applicable, our plan outlines practical recommendations that can be adapted to a wide variety of environments. The procedures and strategies outlined here should serve as guidelines for establishing gene therapy product safety programs at other health care organizations to serve institution-specific standards.

Acknowledgments

We thank Melody Davis at the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital for critical reading of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval Statement

Not applicable to this study.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

Not applicable to this study.

Statement of Informed Consent

Not applicable to this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Sumit Ghosh  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6890-954X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6890-954X

References

- 1. Boulaiz H, Marchal JA, Prados J, Melguizo C, Aránega A. Non-viral and viral vectors for gene therapy. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2005;51(1):3–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lundstrom K. Viral vectors in gene therapy. Diseases. 2018;6(2):1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eisenman D. Established safety profiles allow for a gene therapy boom and streamlining of regulatory oversight. Clinical Researcher. 2019;33(8). Accessed June 4, 2020. https://acrpnet.org/2019/09/19/established-safety-profiles-allow-for-a-gene-therapy-boom-and-streamlining-of-regulatory-oversight/ [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eisenman D. The United States’ Regulatory Environment is evolving to accommodate a coming boom in gene therapy research. Appl Biosaf. 2019;24(3):153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Institutes of Health U.S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov.

- 6. Ghosh S, Brown AM, Jenkins C, Campbell K. Viral vector systems for gene therapy: a comprehensive literature review of progress and biosafety challenges. Appl Biosaf. 2020;25(1):7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins FS, Gottlieb S. The next phase of human gene-therapy oversight. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(15):1393–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen YH, Keiser MS, Davidson BL. Viral vectors for gene transfer. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2018;8(4):58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hutchinson E. American society of gene therapy - First Annual Meeting Education session. The ABCs of non-viral vectors for gene therapy. IDrugs. 1998;1(3):265–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shah PB, Losordo DW. Non-viral vectors for gene therapy: clinical trials in cardiovascular disease. Adv Genet. 2005;54:339–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kootstra NA, Verma IM. Gene therapy with viral vectors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:413–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dangi A, Yu S, Luo X. Emerging approaches and technologies in transplantation: the potential game changers. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16(4):334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Strayer DS. Viral vectors for gene therapy: past, present and future. Drug News Perspect. 1998;11(5):277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guedon JM, Wu S, Zheng X, et al. Current gene therapy using viral vectors for chronic pain. Mol Pai. 2015;11:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hansen JE, Gram GJ. Viral vectors for clinical gene therapy. Ugeskr Laeger. 2002;164(37):4272–4276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. David RM, Doherty AT. Viral vectors: the road to reducing genotoxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2017;155(2):315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Petrich J, Marchese D, Jenkins C, Storey M, Blind J. Gene replacement therapy: a primer for the health-system pharmacist. J Pharm Pract. Published online June 27, 2019. doi:10.1177/0897190019854962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization. Laboratory Biosafety Manual. 3rd ed. WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health. Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. 5th ed. HHS Publication No. (CDC) 21-1112; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Department of Health and Human Services. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH guidelines). 2019:1-14. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Favre D, Provost N, Blouin V, et al. Immediate and long-term safety of recombinant adeno-associated virus injection into the nonhuman primate muscle. Mol Ther. 2001:4(6):559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Millett P, Binz T, Evans SW, et al. Developing a comprehensive, adaptive, and international biosafety and biosecurity program for advanced biotechnology: the iGEM experience. Appl Biosaf. 2019;24(2):64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lunshof JE, Birnbaum A. Adaptive risk management of gene drive experiments: biosafety, biosecurity, and ethics. Appl Biosaf. 2017;22(3):97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghosh S, Voigt J, Wynne T, Nelson T. Developing an in-house biological safety cabinet certification program at the University of North Dakota. Appl Biosaf. 2019;24(3):153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blind JE, McLeod EN, Campbell KJ. Viral-mediated gene therapy and genetically modified therapeutics: a primer on biosafety handling for the health-system pharmacist. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(11):795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Model Plans and Programs for the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens and Hazard Communications Standards (OSHA 3186-06R). 2003;1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bubela T, Boch R, Viswanathan S. Recommendations for regulating the environmental risk of shedding for gene therapy and oncolytic viruses in Canada. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6:58. Published March 28, 2019. doi:10.3389/fmed.2019.00058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Health Organization. Improving Infection Prevention and Control at the Health Facility. 2019;1–123.

- 29. Gabay M. USP <800>: handling hazardous drugs. Hosp Pharm. 2014;49(9):811–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]