Abstract

Degradation of glucose has been implicated in acetate production in rice field soil, but the abundance of glucose, the temporal change of glucose turnover, and the relationship between glucose and acetate catabolism are not well understood. We therefore measured the pool sizes of glucose and acetate in rice field soil and investigated the turnover of [U-14C]glucose and [2-14C]acetate. Acetate accumulated up to about 2 mM during days 5 to 10 after flooding of the soil. Subsequently, methanogenesis started and the acetate concentration decreased to about 100 to 200 μM. Glucose always made up >50% of the total monosaccharides detected. Glucose concentrations decreased during the first 10 days from 90 μM initially to about 3 μM after 40 days of incubation. With the exception at day 0 when glucose consumption was slow, the glucose turnover time was in the range of minutes, while the acetate turnover time was in the range of hours. Anaerobic degradation of [U-14C]glucose released [14C]acetate and 14CO2 as the main products, with [14C]acetate being released faster than 14CO2. The products of [2-14C]acetate metabolism, on the other hand, were 14CO2 during the reduction phase of soil incubation (days 0 to 15) and 14CH4 during the methanogenic phase (after day 15). Except during the accumulation period of acetate (days 5 to 10), approximately 50 to 80% of the acetate consumed was produced from glucose catabolism. However, during the accumulation period of acetate, the rate of acetate production from glucose greatly exceeded that of acetate consumption. Under steady-state conditions, up to 67% of the CH4 was produced from acetate, of which up to 56% was produced from glucose degradation.

Acetate is the main intermediate in anaerobic mineralization of organic carbon in many aquatic ecosystems (22, 27, 29, 43). Even in upland environments, such as prairie and forest soils, where anaerobic conditions are restricted to microsites in soil aggregates, acetate was found to play an important role in the turnover of carbon (20, 37). In rice field soil, acetate is well known as the most dominant fatty acid, and it has frequently been observed to accumulate up to millimolar concentrations within 2 weeks after soil flooding (14, 17, 19, 33, 39). It is also known that during methanogenesis in rice field soil, >60% of the produced CH4 is derived from acetate (28, 31, 34).

Although considerable research has emphasized the consumption of acetate, especially in relation to CH4 formation (17, 31, 33), only a few studies have documented the production and consumption of acetate in the same set of experiments (18, 35). Furthermore, the relationship between accumulation of acetate and catabolism of complex acetate precursors in rice field soil has not seriously been examined. Thebrath et al. (35) investigated the process of reductive acetogenesis from CO2 in Italian rice soil and concluded that this process produces only a small amount of acetate compared to the amount of acetate turned over during methanogenesis. Thus, it is assumed that acetate is produced from other processes to balance its consumption by the ongoing acetoclastic methanogenesis. A study using position-labeled glucose demonstrated that glucose is a potential substrate for acetate production in Italian rice soil (18). To our knowledge, measurement of the glucose concentration in rice field soil has not yet been reported. As a result, the quantitative relationship between glucose catabolism and acetate accumulation is not known.

Sugar analysis with a pulsed amperometric detector (PAD) allows the measurement of the in situ concentrations of various sugars (15, 40, 41). Using this technique, we report here the results of measurement of dissolved monosaccharides in Italian rice field soil. The importance of glucose as a potential acetate precursor and the temporal change of glucose and acetate turnover in anoxic Italian rice field soil were investigated by using [U-14C]glucose and [2-14C]acetate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of anoxic soil.

Rice field soil was obtained in 1993 from the plow layer (0 to 15 cm in depth) of the experimental fields of the Italian Rice Research Institute in Vercelli. The main soil characteristics were 60% sand, 25% silt, 12% clay, 1.49% organic carbon, and 0.15% total nitrogen (12). The soil was air dried, mechanically crushed, passed through a sieve with a mesh size of 0.5 mm, and stored at room temperature until use. Storage of the soil under oxic conditions does not affect the initiation of CH4 production and the population size of methanogenic bacteria (23). Soil slurry was prepared by adding 28 ml of sterilized water to 28 g of air-dried soil in a sterile 120-ml serum bottle. All treatments were duplicates. The bottles were then closed with a sterile black rubber stopper, and the headspace was exchanged with pure nitrogen gas. The incubation of the soil slurry was performed at 30°C without shaking to avoid damage of the methanogenic community (8). At given time intervals, gas samples were taken from the headspace after vigorous shaking of the bottles by hand, and then the samples were analyzed for CO2 and CH4. Two additional bottles were prepared for slurry sampling and analysis of organic acids. For analysis of monosaccharides, 20 additional bottles were prepared, and 2 were sacrificed at each time point. The pH of the soil slurries increased from an initial pH of 6.0 and eventually stabilized at pH 7.1.

Radioactive studies.

An additional 13 duplicate bottles with soil slurry were prepared for each radioactive experiment, with one set for [U-14C]glucose utilization and another one for [2-14C]acetate utilization. Four radioactive experiments with both [U-14C]glucose and [2-14C]acetate were conducted (i.e., at 0, 5, 10, and 36 days after the start of the anoxic slurry incubation). Approximately 2.5 μCi (1 μCi = 2.22 × 106 dpm = 37 kBq) of carrier-free [U-14C]glucose or [2-14C]acetate (purity of >99%; specific radioactivity of 300 mCi mmol−1 for glucose and 57 mCi mmol−1 for acetate; American Radiolabel Chemical, Inc.) was added with a syringe to each bottle. Before the labeled compounds were added at day 0, the bottles were preincubated for 5 h at 30°C for acclimatization. With the exception of days 10 and 36, when the amounts of [U-14C]glucose added were 6 and 8% of the glucose pool size, respectively, the [U-14C]glucose and [2-14C]acetate added at the other dates were <1% of the substrate pools. Therefore, addition of labeled compounds did not significantly increase the endogenous pool sizes of both substrates.

The reaction in the bottles was terminated by addition of 3 ml of 7 N H2SO4. Slurry acidification also resulted in the release of 14CO2 from dissolved radioactive bicarbonate and carbonate to the gas phase (9). When used below, the term “14CO2” is assumed to represent total 14CO2 (CO2 plus bicarbonate plus carbonate). Recovery of the [U-14C]glucose added to the autoclaved soil was constant throughout the experiment at 97.66% ± 2.32% (mean ± standard error [SE]; n = 4). When [2-14C]acetate was added to autoclaved soil, its recovery was constant at 46.10% ± 1.57% (mean ± SE; n = 4). The relatively low recovery of acetate from the sterilized soil slurry indicates that this was due to physical factors, such as absorption to soil particles and/or exchange with tightly bound acetate pools, which were not accessible by the extraction procedure (5, 25, 31). When used below, the term “radioactivity” of glucose or acetate refers to the values that have been previously corrected by the radioactive recovery from autoclaved soil slurry.

Chemical analyses.

To measure the concentrations of monosaccharides, the soil slurry was transferred to a sterile 30-ml centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 5,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered through 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate membrane filters (Nucleopore Corp., Pleasanton, Calif.) and immediately frozen at −20°C until analysis. For the analyses of acetate and propionate, 1 ml of soil slurry was taken at each given time and centrifuged at 14,000 × g at room temperature for 5 min. The supernatant was passed through polytetrafluoroethylene membrane filters with a pore size of 0.2 μm (Sartorious AG, Göttingen, Germany).

Concentrations of CH4 and CO2 were determined by gas chromatography (7). Radioactivity of gaseous products was measured by a gas proportional counter as described previously (7). Acetate and propionate concentrations were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Sykam, Gauting, Germany) with a chromatograph equipped with a refraction index detector (18). The detection limit was approximately 5 μM. The radioactivity of glucose and acetate was measured by connecting a scintillation monitor (a lithium-glass scintillator cell with a volume of 400 μl; Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany) to the outlet of the HPLC column. The limit of detection of radioactivity was approximately 1 kdpm ml of eluent−1 (35). The concentration of glucose could not be determined by the refractive index detector due to the interference of an unknown peak. Thus, monosaccharides were determined in a parallel experiment by using PAD-HPLC. The PAD-HPLC was equipped with a Dionex ED40 PAD and a gold electrode, and the sugars were separated by CarboPac PA10 columns (250 by 4 and 50 by 4 mm) eluted with NaOH at different concentrations (15). Mannose and xylose could not be completely separated by these columns and, therefore, are shown as a combined peak (mannose plus xylose).

Calculations.

The uptake rate constant (k) of glucose and acetate was estimated from a semilogarithmic plot of the radioactive glucose or acetate (disintegrations per minute) versus the incubation time, and then the slope of the line was determined. The data points included in the calculation of glucose uptake rate constant were usually obtained within 20 min after the addition of [U-14C]glucose, except at day 0, when the data points between 10 and 120 min were used. Acetate uptake rate constants were calculated from the time period when accumulation of metabolic products was observed. These were between 120 and 720 min (n = 4) at day 0, between 60 and 720 min (n = 6) at day 5, between 120 and 1,440 min (n = 4) at day 10, and between 0 and 240 min (n = 7) at day 36. Actual turnover rates of glucose and acetate were obtained by multiplying the uptake rate constant by the pool size (pore water concentration) of the respective substrate. The fraction of CH4 produced from the labeled acetate added was calculated from the specific radioactivity (SR; disintegrations per minute per nanomole) of the CH4 produced and the SR of acetate (disintegrations per minute per nanomole). In addition, the respiratory index (RI) was used to compare the carbon flow toward CH4 and CO2: RI = [(14CO2)/(14CO2 + 14CH4)].

RESULTS

Abundance of monosaccharides in rice field soil.

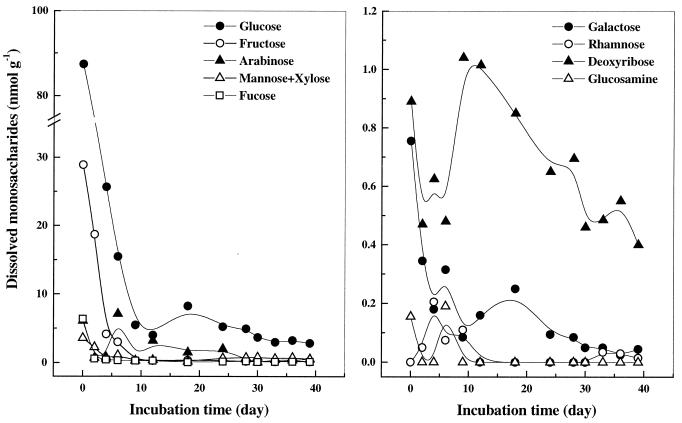

When the soil condition was changed from air dried to prolonged flooding, the content of total dissolved monosaccharides decreased significantly from 136 μM to 5 μM. Glucose was the dominant monosaccharide (Fig. 1). The contribution of glucose to total dissolved monosaccharides was always >50%. Fructose was the second-most-abundant monosaccharide (21%). Relatively large amounts (>10% of total monosaccharides) of arabinose and deoxyribose were occasionally found. Mannose plus xylose made up <5% of total monosaccharides during the early period of incubation, but increased to >10% a month later. Other monosaccharides detected were galactose, rhamnose, fucose, and glucosamine. However, together these sugars made up <10% of total monosaccharides. On a carbon basis, the total dissolved monosaccharides in the present study were <1% of the total soil organic carbon content.

FIG. 1.

Dissolved monosaccharides detected in Italian rice field soil. The first data point represents the measurement in extracts of air-dried soil before slurring; 1 nmol g of dry soil−1 is equivalent to a pore water concentration of 1 μM.

Sequential reduction processes and acetate and CH4 accumulation.

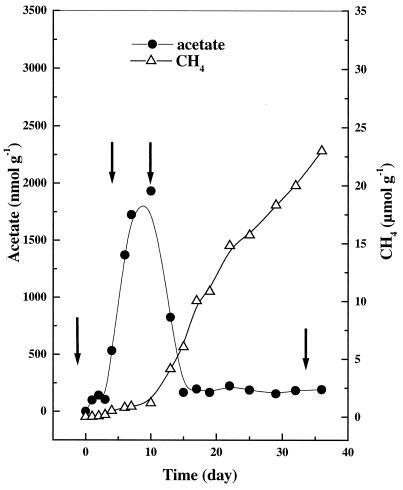

The reduction process in the Italian rice field soil has been well investigated (1, 17, 19). Generally, nitrate is consumed within less than a day of anaerobic incubation. Reduction of ferric iron also starts immediately after onset of anaerobic incubation, but usually lasts until about days 10 to 15. Sulfate reduction, on the other hand, begins at about day 5 and continues until about days 10 to 15. Thus, the time from day 0 to day 15 when various oxidants are sequentially reduced is designated as the “reduction phase” (44). Accumulation of acetate during this reduction phase has often been observed and is regarded as a typical characteristic of anoxic rice field soil. In the present study, acetate started to accumulate at day 5 and reached its accumulation peak (ca. 2 mM) around day 10 (Fig. 2). CH4 production started around day 10 and reached a constant rate of 34.5 nmol g−1 h−1 around day 15. The period after day 15 is therefore designated as the “methanogenic phase.” The acetate concentration during the methanogenic phase was 100 to 200 μM. Propionate was also found to accumulate, but generally made up <5% of the acetate concentration and became undetectable after day 25 (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Temporal changes of production of acetate and CH4 in anoxic rice soil slurry. The arrows indicate the dates when labeled glucose and acetate were added.

Products of the glucose and acetate metabolisms.

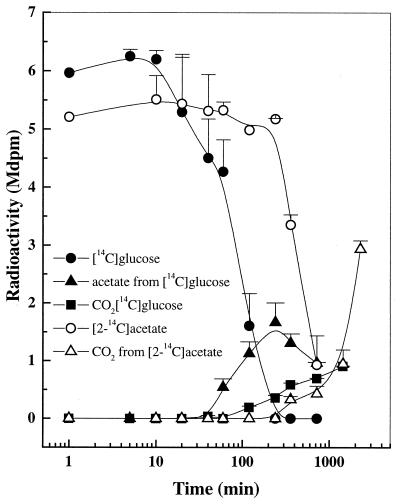

When [U-14C]glucose was added to the soil at day 0, its consumption started only after a lag phase of about 20 min (Fig. 3). After glucose consumption started, [14C]acetate and, somewhat later, 14CO2 started to accumulate. 14CH4 was not produced. Glucose consumption and the formation of radioactive products followed the same pattern for days 5 (data not shown), 10 (data not shown), and 36 (Fig. 4), but some differences were found in the magnitude and time course of intermediate and end product formation. Besides acetate, propionate was occasionally detected from [U-14C]glucose catabolism, but the amount was too small to be accurately quantified.

FIG. 3.

Uptake and product formation from [U-14C]glucose and [2-14C]acetate in anoxic rice soil slurry at day 0. Values are means ± SD of duplicate determinations. Note the logarithmic time scale.

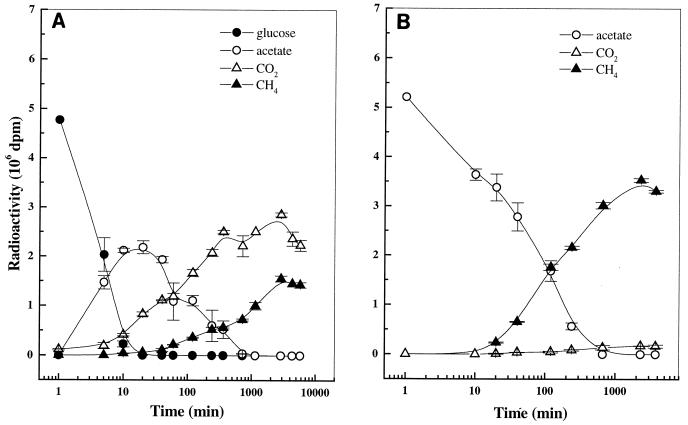

FIG. 4.

Uptake and product formation from [U-14C]glucose (A) and [2-14C]acetate (B) in anoxic rice soil slurry at day 36. Values are means ± SD of duplicate determinations. Note the logarithmic time scale.

In contrast to the results obtained at day 0 (Fig. 3), [U-14C]glucose was consumed without a lag after its addition at days 5, 10, and 36 (Fig. 4). At day 5, consumption of [U-14C]glucose was completed after 10 min (data not shown). Again, only 14CO2, but no 14CH4, was produced. At day 10, however, a small amount of 14CH4 was produced 2 days after glucose addition (data not shown), although the main products of glucose degradation were still labeled CO2 and acetate. The appearance of 14CH4 long after addition of [U-14C]glucose at this date indicates that the newly formed radioactive acetate was only slowly consumed. This result was in agreement with the uptake rate constant of acetate (see next section), which was slowest at day 10. At day 36, more 14CH4 was produced from [U-14C]glucose, but [14C]acetate and 14CO2 were still the main degradation products (Fig. 4).

The final recovery of [U-14C]glucose in the form of radioactive products (CO2 plus acetate plus CH4) ranged from 31% at day 0 to 84% at day 36 (Table 1), indicating that intracellular storage or assimilation into the biomass was approximately 70% at day 0 and was less than 20% at day 36. Despite the high variation in glucose uptake as described below, the maximum recovery of glucose as labeled acetate was fairly constant at 44 to 47% during the reduction phase and 62% during methanogenic phase, respectively (Table 2), assuming that two-thirds of glucose carbon was maximally incorporated into acetate as glucose was degraded by glycolysis (17).

TABLE 1.

Turnover of glucose and acetate in anaerobic rice soil at different dates of soil incubationa

| Product | Rate constant (h−1)b | r2 | n | P | Pool size (nmol g−1) | Turnover rate (nmol g−1 h−1) | Turnover time (h) | RI | Recovery of radioactivity in products (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | |||||||||

| Glucose | 0.31 | 0.96 | 5 | 0.004 | 89 | 27.7 | 3.2 | 1.00 | 31.4 |

| Acetate | 0.07 | 0.97 | 4 | 0.015 | 309 | 22.9 | 13.5 | 1.00 | 68.5 |

| Day 5 | |||||||||

| Glucose | 28.6 | 0.89 | 3 | 0.208 | 26 | 733.4 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 58.1 |

| Acetate | 0.03 | 0.94 | 6 | 0.001 | 233 | 6.5 | 35.7 | 1.00 | 78.5 |

| Day 10 | |||||||||

| Glucose | 6.7 | 0.96 | 3 | 0.122 | 5 | 36.8 | 0.15 | 0.82 | 53.1 |

| Acetate | 0.02 | 0.98 | 4 | 0.009 | 1,336 | 21.4 | 62.5 | 0.22 | 95.7 |

| Day 36 | |||||||||

| Glucose | 7.9 | 0.94 | 3 | 0.058 | 3 | 25.9 | 0.13 | 0.76 | 83.5 |

| Acetate | 0.22 | 0.98 | 7 | <0.0001 | 130 | 28.7 | 4.5 | 0.07 | 68.9 |

Each value represents the mean of two replicates. The quality of the fit is given by r2 and P.

Rate constants were calculated by linear regression of n data pairs.

TABLE 2.

Acetate production from glucose catabolism at different times of rice field soil incubationa

| Day of incuba-tion | Recovery of [14C]glucose as [14C]acetate (%)b | Rate of acetate production from glucose (nmol g−1 h−1)c | Total acetate turnover rate (nmol g−1 h−1) | % Acetate turned over via glucose | Total CH4 production (nmol g−1 h−1) | CH4 production from acetate (nmol g−1 h−1)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1 − RI) × acetate turnover rate | (SRCH4/SR[2-14C]acetate) × total CH4 production | ||||||

| 0 | 44.5 | 12.3 | 22.9 | 54 | |||

| 5 | 43.8 | 321.3 | 6.5 | 4,928 | |||

| 10 | 47.2 | 17.4 | 21.4 | 81 | |||

| 36 | 62.4 | 16.2 | 28.7 | 56 | 39.7 | 26.7 | 20.4 |

Each value represents the mean of two replicates.

Recovery of [14C]glucose as [14C]acetate, assuming that two-thirds of the radioactivity of glucose is maximally converted to acetate.

Glucose turnover rate × fraction (percent) of acetate production from glucose.

Similar to glucose consumption at day 0, acetate was not consumed until 6 h after its addition (Fig. 3). When [2-14C]acetate was added to the soil at days 0 and 5, only 14CO2, but no 14CH4, was produced. Thus, similar to glucose metabolism, acetate was metabolized oxidatively to CO2. On the other hand, the end product of acetate metabolism at day 10 was mainly 14CH4 (RI = 0.22; Table 1). This indicates that at day 10, acetoclastic methanogenesis was already established. During the active CH4 formation at day 36, almost all of the [2-14C]acetate was converted to CH4 (RI = 0.07; Fig. 4 and Table 1). The rate of total CH4 production measured during the radioactive experiment at day 36 was 39.7 nmol g−1 h−1. The recovery of radioactive acetate after 12 h generally ranged from 70 to 96%, indicating that only a small portion of acetate was assimilated into microbial biomass.

Turnover of glucose and acetate.

We used [2-14C]acetate instead of [U-14C]acetate or [1-14C]acetate for two main reasons: (i) to account for acetate-dependent CH4 production during the methanogenic phase of the soil (17, 35) and (ii) to avoid isotopic exchange between the carboxyl position of acetate and CO2. This exchange process is known to be rapid and may be a source of bias when acetate turnover is estimated from [1-14C]acetate or [U-14C]acetate (9).

The uptake rate constant of glucose changed with the date of anaerobic soil incubation (Table 1). It was lowest at day 0 (0.3 h−1), highest at day 5 (28.6 h−1), and stayed relatively constant (6.7 to 7.9 h−1) thereafter. Consequently, the turnover time of glucose ranged from 3 h at day 0 to about 2 min at day 5. The change in the uptake rate constant together with the change in the glucose pool size (Table 1) led to a change in the glucose turnover rate from 28 nmol g−1 h−1 at day 0 to 733 nmol g−1 h−1 at day 5 and then to 26 nmol g−1 h−1 at day 36. For acetate, the uptake rate constant was less variable than for glucose. The lowest acetate uptake rate constant (k = 0.07 h−1) was found at day 10, when the acetate pool size attained its maximum (Fig. 2). Relatively slow acetate uptake was also found at day 5 (k = 0.03 h−1), when glucose degradation was fastest. Acetate uptake was fastest at day 36 (k = 0.22 h−1). As a result, the acetate turnover times ranged from >60 h at day 10 to about 5 h at day 36. The pore water concentration of acetate varied over a range of 130 to 1,336 nmol g−1. Thus, the turnover rates of acetate were between 6 nmol g−1 h−1 at day 5 and approximately 29 nmol g−1 h−1 at day 36.

DISCUSSION

Incorporation of organic matter such as rice straw into rice field soil is a traditional farming practice for enhancing soil nutrient availability and productivity (13, 26). In Italian rice field soil, rice straw has been annually incorporated into the soil when the field is plowed after drainage and harvest. Microbial breakdown of rice straw (ca. 50% cellulose and 20 to 30% hemicellulose on a dry weight basis [36]) releases soluble carbohydrates which become part of the dissolved organic carbon pool available for soil microbes (21, 32, 38). Glucose was the most abundant monosaccharide in rice field soil, similar to the case in freshwater and marine ecosystems (3, 10, 11, 15, 16, 24, 41). The concentrations of glucose (3 to 90 μM) and total dissolved monosaccharides (5 to 136 μM) in the Italian rice field soil were in the same range as values reported in the literature.

The dominant glucose-utilizing microorganisms are not known definitely, but polysaccharolytic clostridia with the capacity to ferment glucose have been isolated (4). The formation of acetate and other fatty acids from glucose (18) indicates that fermentative microorganisms were important. Glycolysis has been shown to be the glucose degradation pathway in Italian rice field soil (18). Through this pathway, both CO2 and acetate would be simultaneously produced. However, we observed that the labeled glucose was consumed relatively faster than the formation of the products and that acetate was released faster than CO2. King and coworkers (16, 30) suggested that the observed difference between [U-14C]glucose uptake and 14C-end product formation is most likely due to differences in the specific radioactivity of extracellular and intracellular glucose pools. The slower formation of 14C-end product can be explained by the transport of [U-14C]glucose from extracellular pools with a relatively high specific radioactivity to intracellular pools with a lower specific radioactivity.

Uptake of glucose varied greatly throughout the incubation period. The most rapid uptake of glucose and acetate was found at days 5 and 36, respectively. At day 5, rapid glucose uptake was accompanied by a relative slow acetate uptake and therefore resulted in the accumulation of acetate during days 5 to 10 (Fig. 2). It is likely that a similar imbalance between glucose degradation and acetate consumption is the reason for the accumulation of acetate that has usually been observed in other rice fields within 1 or 2 weeks of flooding (14, 33, 39). Nitrate reducers and ferric iron reducers were shown to be able to utilize acetate efficiently (1), while acetotrophic sulfate reducers were not so numerous and active in anoxic rice soil (2, 42). However, since soil nitrate is normally consumed within a few hours of anoxic incubation (1, 17), ferric iron reducers instead of nitrate reducers would play the most important role for acetate consumption during the reduction phase. We observed that acetate uptake was much faster during the methanogenic phase than during the reduction phase, probably due to activation and/or growth of acetate-utilizing methanogens. Hence, population shifts may be responsible for variations in glucose and acetate uptake during the incubation period.

The amount of [U-14C]glucose recovered as labeled acetate was used to estimate the rate of acetate production from glucose (Table 2). Glucose apparently served as an important precursor of acetate in rice field soil. Acetate production from glucose alone accounted for 54, 81, and 56% of the acetate turned over at days 0, 10, and 36, respectively. Thus, during these dates, it is assumed that acetate was additionally produced from other substrates (e.g., dissolved combined carbohydrates [11, 24]) to balance the amount of acetate that was simultaneously consumed. On the other hand, at day 5, the rate of acetate production from glucose was considerably greater than the rate of acetate consumption. It is noted that the rate of glucose consumption, and consequently the rate of acetate production from glucose at day 5, was so high that its persistence until day 10 would have resulted in the accumulation of 321 nmol of acetate per g of soil. However, the actual amount of acetate that accumulated between days 5 and 10 was much less (ca. 15 nmol g−1), indicating that the high rate of glucose turnover at day 5 persisted only for a short time.

From the experiment using labeled acetate, we know that 93% of the acetate was converted to CH4 (RI = 0.07; Table 1) at day 36. By assuming that CH4 was only produced from acetate or H2-CO2, the rate of CH4 production from acetate was estimated to be 20 to 27 nmol g−1 h−1, or 51 to 67% of the total rate of CH4 production (Table 2). These fractions of CH4 produced from acetate (51 to 67%) agree reasonably well with the value of 66% that is theoretically expected when carbohydrates are methanogenically degraded (6) and also agree with earlier estimates of fractions of CH4 produced from H2-CO2 (28). We also estimated the flow of carbon from glucose to CH4 (via acetate) by multiplying the rate of CH4 production from acetate with the percentage of acetate produced from glucose resulting in 32 to 42% of total CH4 formation. A similar range (30 to 40%) was also given by other studies (16, 22), indicating that glucose degradation via acetate to CH4 is of general importance in methanogenic systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Simon for giving access to the analytical equipment for the analysis of monosaccharides.

Amnat Chidthaisong was supported by a fellowship of the Alexander-von-Humboldt Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtnich C, Bak F, Conrad R. Competition for electron donors among nitrate reducers, ferric iron reducers, sulfate reducers, and methanogens in anoxic paddy soil. Biol Fertil Soils. 1995;19:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achtnich C, Schuhmann A, Wind T, Conrad R. Role of interspecies H2 transfer to sulfate and ferric iron reducing bacteria in acetate consumption in anoxic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;16:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boschker H T S, Dekkers E M J, Pel R, Cappenberg T E. Sources of organic carbon in the littoral of Lake Gloomier as indicated by stable carbon isotope and carbohydrate compositions. Biogeochemistry. 1995;29:89–105. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin K J, Rainey F A, Janssen P H, Conrad R. Methanogenic degradation of polysaccharides and the characterization of polysaccharolytic clostridia from anoxic rice field soil. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen D, Blackburn T H. Turnover of 14C-labelled acetate in marine sediments. Mar Biol. 1982;71:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conrad R. Contribution of hydrogen to methane production and control of hydrogen concentrations in methanogenic soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;28:193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad R, Mayer H P, Wüst M. Temporal change of gas metabolism by hydrogen-syntrophic methanogenic bacterial associations in anoxic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1989;62:265–274. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dannenberg S, Wudler J, Conrad R. Agitation of anoxic paddy soil slurries affects the performance of the methanogenic microbial community. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;22:257–263. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Graaf W, Wellsbury P, Parkes R J, Cappenberg T E. Comparison of acetate turnover in methanogenic and sulfate-reducing sediments by radiolabeling and stable isotope labeling and by use of specific inhibitors: evidence for isotopic exchange. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:772–777. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.772-777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dulov L E, Namsaraev B B, Lisyanskaya V Y. Seasonal decomposition of glucose in littoral sediments of a eutrophic lake. Microbiology. 1995;64:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanisch K, Schweitzer B, Simon M. Use of dissolved carbohydrates by planktonic bacteria in mesotrophic lake. Microb Ecol. 1996;31:41–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00175074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holzapfel-Pschorn A, Conrad R, Seiler W. Effect of vegetation on the emission of methane from submerged paddy soil. Plant Soil. 1986;92:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoko A. Organic matter and rice. Los Baños, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute; 1984. Compost as a source of plant nutrients; pp. 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inubushi K, Wada H, Takai Y. Easily decomposable organic matter in paddy soil. IV. Relationship between reduction process and organic matter decomposition. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1984;30:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jørgensen N O G, Jensen R E. Microbial fluxes of free monosaccharides and total carbohydrates in freshwater determined by PAD-HPLC. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1994;14:79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 16.King G M, Klug M J. Glucose metabolism in sediments of a eutrophic lake: tracer analysis of uptake and product formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:1308–1317. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.6.1308-1317.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klüber H D, Conrad R. Effect of nitrate, NO, and N2O on methanogenesis and other redox processes in anoxic rice field soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25:301–318. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krumböck M, Conrad R. Metabolism of position-labelled glucose in anoxic methanogenic paddy soil and lake sediment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1991;85:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krylova N I, Janssen P H, Conrad R. Turnover of propionate in methanogenic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;23:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Küsel K, Drake H L. Acetate synthesis in soil from a Bavarian beech forest. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1370–1373. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1370-1373.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leschine S B, Canale-Parola E. Mesophilic cellulolytic clostridia from freshwater environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:728–737. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.3.728-737.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovley D R, Klug M J. Intermediary metabolism of organic matter in the sediments of a eutrophic lake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:552–560. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.3.552-560.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer H P, Conrad R. Factors influencing the population of methanogenic bacteria and the initiation of methane production upon flooding of paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1990;73:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Münster U. Extracellular enzyme activity in eutrophic and polyhumic lakes. In: Chrost R J, editor. Microbial enzymes in aquatic environments. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1991. pp. 96–122. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parkes R J, Taylor J, Joerck-Ramberg D. Demonstration, using Desulfobacter sp., of two pools of acetate with different biological availabilities in marine pore water. Mar Biol. 1984;83:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ponnamperuma F N. IRRI (ed.), Organic matter and rice. Los Baños, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute; 1984. Straw as a sources of nutrients for wetland rice; pp. 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothfuss F, Conrad R. Thermodynamics of methanogenic intermediary metabolism in littoral sediment of Lake Constance. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1993;12:265–276. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothfuss F, Conrad R. Vertical profiles of CH4 concentrations, dissolved substrates and processes involved in CH4 production in a flooded Italian rice field. Biogeochemistry. 1993;18:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sansone F J, Martens C S. Methane production from acetate and associated methane fluxes from anoxic coastal sediments. Science. 1981;211:707–709. doi: 10.1126/science.211.4483.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawyer T E, King G M. Glucose uptake and end product formation in an intertidal marine sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:120–128. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.120-128.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schütz H, Seiler W, Conrad R. Processes involved in formation and emission of methane in rice paddies. Biogeochemistry. 1989;7:33–53. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snitwongse P, Pongpan S, Neue H U. Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Paddy Soil Fertility, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 6 to 13 December 1988. 1988. Decomposition of 14C-labelled rice straw in a submerged and aerated rice in northern Thailand; pp. 461–479. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugimoto A, Wada E. Carbon isotopic composition of bacterial methane in a soil incubation experiment: contribution of acetate and CO2/H2. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1993;57:4015–4027. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takai Y. The mechanism of methane fermentation in flooded paddy soil. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1970;16:238–244. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thebrath B, Mayer H P, Conrad R. Bicarbonate-dependent production and methanogenic consumption of acetate in anoxic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1992;86:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vlasenko E Y, Ding H, Labavitch J M, Shoemaker S P. Enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated rice straw. Biores Technol. 1997;59:109–119. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner C, Grießhammer A, Drake H L. Acetogenic capacities and the anaerobic turnover of carbon in a Kansas prairie soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:494–500. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.494-500.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warren R A J. Microbial hydrolysis of polysaccharides. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:183–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe I. Organic matter and rice. Los Baños, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute; 1984. Anaerobic decomposition of organic matter in flooded rice soil; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- 40.White D R, Jr, Widmer W W. Application of high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection to sugar analysis in citrus juice. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38:1918–1921. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wicks R J, Moran M A, Pittman L J, Hodson R E. Carbohydrate signatures of aquatic macrophytes and their dissolved degradation products as determined by a sensitive high-performance ion chromatography method. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3135–3143. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3135-3143.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wind T, Conrad R. Sulfur compounds, potential turnover of sulfate and thiosulfate, and numbers of sulfate-reducing bacteria in planted and unplanted paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;18:257–266. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winfrey M R, Zeikus J G. Microbial methanogenesis and acetate metabolism in a meromictic lake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;37:213–221. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.2.213-221.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao, H., R. Conrad, R. Wassmann, and H. U. Neue. Effect of soil characteristics on sequential reduction and methane production in sixteen rice paddy soils from China, the Philippines, and Italy. Biogeochemistry, in press.