SUMMARY

This study assessed variation in coverage of maternal pertussis vaccination, introduced in England in October 2012 in response to a national outbreak, and a new infant rotavirus vaccination programme, implemented in July 2013. Vaccine eligible patients were included from national vaccine coverage datasets and covered April 2014 to March 2015 for pertussis and January 2014 to June 2016 for rotavirus. Vaccine coverage (%) was calculated overall and by NHS England Local Team (LT), ethnicity and Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintile, and compared using binomial regression. Compared with white-British infants, the largest differences in rotavirus coverage were in ‘other’, white-Irish and black-Caribbean infants (−13·9%, −12·1% and −10·7%, respectively), after adjusting for IMD and LT. The largest differences in maternal pertussis coverage were in black-other and black-Caribbean women (−16·3% and −15·4%, respectively). Coverage was lowest in London LT for both programmes. Coverage decreased with increasing deprivation and was 14·0% lower in the most deprived quintile compared with the least deprived for the pertussis programme and 4·4% lower for rotavirus. Patients’ ethnicity and deprivation were therefore predictors of coverage which contributed to, but did not wholly account for, geographical variation in coverage in England.

Key words: Ethnicity, inequalities, vaccination

INTRODUCTION

Whooping cough (pertussis) is a highly infectious respiratory disease caused by Bordetella pertussis. In infants, illness can be clinically severe, often resulting in hospitalisation, whereas adolescents and adults typically present with milder illness. The risk of complications and death is highest in infants, particularly those aged <6 months [1, 2]. Rotavirus represents another common infection that mainly affects young infants causing vomiting and diarrhoea, sometimes leading to dehydration and hospitalisation. The routine vaccination schedule in England now provides protection against both pathogens, although using different strategies.

In 2012, pertussis incidence increased beyond levels reported in the previous 20 years [3]. In response, a national pertussis outbreak was declared, and in October 2012, a temporary maternal pertussis vaccination programme was introduced [4] offering vaccination to every pregnant woman initially between 28 and 32 weeks [5], and between 20 and 32 weeks after April 2016 [6]. The programme aims to passively protect infants from birth, through intra-uterine antibody transfer, until they can be actively protected with the first dose of pertussis vaccine scheduled at 2 months of age [7], and through directly protecting mothers, lowering their probability of being a source of infection for their infants.

The rotavirus immunisation programme was introduced in 2013 in the UK with the aims of directly protecting infants against infection and providing herd immunity to the wider population [7], using a two-dose schedule given at 8 and 12 weeks of age [5].

The programmes have achieved high coverage, and demonstrated impact and/or effectiveness against both rotavirus [8] and pertussis [9, 10]. For the period August 2015–January 2016, 88·9% of 6-month olds had received two doses of rotavirus [11], whereas coverage for the maternal pertussis programme has increased yearly since its introduction, reaching 60·7% in March 2016 [12]. However, equity of delivery, mandated by the UK Equality Act 2010 [13], has not been evaluated.

Differential coverage of vaccinations by socio-demographic factors including ethnic group, religious affiliation and markers of socio-economic status have been demonstrated for a number of vaccination programmes in the UK and elsewhere [14–20]. Routine surveillance of vaccine coverage for the maternal pertussis and infant rotavirus vaccination programmes indicates marked variation by geographical area and ethnic group [21, 22]. We aimed to assess and quantify coverage inequalities for these two recently implemented vaccination programmes taking ethnicity, geography and deprivation into account.

METHODS

Data collection

Data were collected via ImmForm, a platform which automatically extracts data from four participating general practice (GP) IT suppliers, representing 95% GPs in England, and used by the Public Health England (PHE) to estimate coverage for a number of vaccine programmes. Ethnicity is only captured in ImmForm when coded using the Office for National Statistics (ONS) 2001 census classifications. When ethnicity is not recorded or recorded using another classification, it is coded as not recorded.

Data handling

Data from one of four GP IT suppliers, representing 1·1% of the sample, were found to be unreliable in the maternal pertussis dataset and were excluded [21]. For rotavirus, two of four GP IT suppliers, representing 45% of eligible infants, provided incomplete ethnicity data and were excluded [22]. Each GP was assigned to their relevant NHS England commissioning region termed a Local Team (LT). Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) estimates for GPs were calculated by the Department of Primary Care and Public Health Sciences, King's College London (Dr Mark Ashworth, personal communication, 2015). A population weighted average was built over the IMD scores of the lower super output areas (LSOAs, small administrative areas defined by ONS [23]), with an average population of 1500 residents or 650 households where the practice population resided, using patient numbers obtained from the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) at April 2015. Ethnicity data collected as numbers of patients by ethnic group for each GP were disaggregated into patient-level data. Practices not included in the IMD dataset or where all patients had no ethnicity recorded were excluded from analyses. Quintiles were generated for IMD scores and assigned at the patient level according to their GP's assigned IMD score. Patients were assigned a LT based on their GP postcode. Therefore, for each patient, vaccination status and ethnicity were assessed at an individual level, with IMD and geographical area considered at an ecological level. Data management was undertaken in Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, USA).

Data analysis

To assess representativeness of the study sample, GPs included in the study were compared with all GPs in England by LT and IMD. Live birth statistics for 2013–2015 were used to estimate the proportion of the underlying populations represented in the datasets [24]. The distribution of ethnic groups in the pertussis sample was compared to maternal ethnicity data captured in the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) delivery data [25].

To estimate maternal pertussis vaccine coverage, the percentage of women who delivered at more than 28 weeks gestational age between April 2014 and March 2015 who received a pertussis-containing vaccine in the preceding 14 weeks was calculated. For rotavirus, the number of infants in each GP who, in each month between January 2014 and June 2016, reached 25 weeks of age and of those the number who received (a) a first dose and (b) a second dose of vaccine between 6 and 24 weeks of age were extracted.

Vaccine coverage (%) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated overall and by LT, IMD quintile and patient's ethnic group. To assess the reliability of coverage estimates, national coverage was also calculated using the datasets prior to excluding patients with no ethnicity recorded. For each predictor, we used binomial regression using an identity link to calculate risk difference in coverage between a baseline group and others. Interactions between ethnicity and IMD quintile were also considered. For rotavirus, differences between the baseline group and others were calculated for vaccine completion (i.e. two doses) and for differences between initiation (one dose) and completion, using binomial regression. London LT, white-British ethnicity and the least deprived IMD quintile were chosen as baseline groups. All analyses were undertaken in STATA 13·0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Data representativeness

For both programmes, the GPs included were distributed across all 13 LTs (Table 1). However, participation by LT varied from 23·0% in the East LT to 86·8% in Lancashire and Greater Manchester for the maternal pertussis programme, and 25·6% in Yorkshire and Humber LT to 86·5% in Cheshire and Merseyside LT for the infant rotavirus programme. The mean IMD score attributed to GPs included in the samples did not differ to all GPs nationally or by LT (data not shown).

Table 1.

Proportion of GP data included in the study for the maternal pertussis vaccination programme April 2014 to March 2015, and the infant rotavirus vaccination programme January 2014 to June 2016

| NHS England local team | Maternal pertussis programme | Infant rotavirus programme | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All GPs | Included GPs1-5 | % | All GPs | Included GPs1-5 | % | |

| Central Midlands | 554 | 173 | 31·2 | 565 | 166 | 29·4 |

| Cheshire and Merseyside | 389 | 337 | 86·6 | 394 | 341 | 86·5 |

| Cumbria and North East | 462 | 270 | 58·4 | 472 | 274 | 58·1 |

| East | 551 | 127 | 23·0 | 560 | 144 | 25·7 |

| Lancashire and Greater Manchester | 718 | 623 | 86·8 | 723 | 548 | 75·8 |

| London | 1395 | 1081 | 77·5 | 1426 | 996 | 69·8 |

| North Midlands | 505 | 260 | 51·5 | 518 | 270 | 52·1 |

| South Central | 427 | 279 | 65·3 | 434 | 246 | 56·7 |

| South East | 588 | 443 | 75·3 | 597 | 324 | 54·3 |

| South West | 403 | 232 | 57·6 | 411 | 291 | 70·8 |

| Wessex | 314 | 196 | 62·4 | 322 | 183 | 56·8 |

| West Midlands | 668 | 538 | 80·5 | 689 | 499 | 72·4 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 768 | 195 | 25·4 | 790 | 202 | 25·6 |

| England | 7742 | 4754 | 61·4 | 7901 | 4484 | 56·8 |

All GPs included consenting GPs using a GP IT supplier systems able to automatically extract data as of May 2015 for the retrospective period April 2015 to March 2015.

GPs were excluded if they had no weighted IMD score due not comprising the HSCIC GPs population taken at April 2015, if they had no eligible patients over the reporting period and if all eligible patients extracted had ethnicity assigned as not recorded.

GPs were excluded from two IT suppliers identified during data validation as incorrectly implementing the extraction specification with regards to ethnicity.

All GPs included consenting GPs using a GP IT supplier system able to automatically extract data for one or more months during the monthly reporting period July 2013 to June 2016.

GPs were excluded from one IT supplier identified during data validation as incorrectly implementing the extraction specification with regards to ethnicity.

A sample of 191 533 women eligible for maternal pertussis vaccination and 459 074 infants eligible for infant rotavirus vaccination were included for analyses. The average number of babies born annually between 2013 and 2015 in England was 663 000, and the study samples for pertussis and rotavirus therefore represented approximately 29% and 28% of their respective populations. The total proportion of white women in the pertussis sample was 72·9% and 75·6% infants in the rotavirus sample (Table 2), which compared with 75·5% among mothers reported in the 2014–2015 HES delivery data [25].

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients included in the study for maternal pertussis vaccination (April 2015–March 2015) and infant rotavirus vaccination (January 2013–June 2016) in England

| Pertussis vaccination | Rotavirus vaccination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | % Patients | No. patients | % Patients | |

| All patients | 191 533 | n/a | 459 074 | n/a |

| NHS England area team | ||||

| Central Midlands | 8560 | 4·5 | 21 484 | 4·7 |

| Cheshire and Merseyside | 8970 | 4·7 | 25 181 | 5·2 |

| Cumbria and North East | 6846 | 3·6 | 20 211 | 4·4 |

| East | 5429 | 2·8 | 14 665 | 3·2 |

| Lancashire and Greater Manchester | 20 052 | 10·5 | 44 997 | 9·7 |

| London | 54 724 | 28·6 | 131 225 | 28·8 |

| North Midlands | 9511 | 5·0 | 22 072 | 4·9 |

| South Central | 15 235 | 8·0 | 31 111 | 6·6 |

| South East | 14 725 | 7·7 | 28 398 | 6·2 |

| South West | 10 308 | 5·4 | 29 243 | 6·6 |

| Wessex | 9083 | 4·7 | 21 396 | 4·7 |

| West Midlands | 20 320 | 10·6 | 49 025 | 10·5 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 7770 | 4·1 | 20 066 | 4·5 |

| IMD quintile | ||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 38 313 | 20·0 | 92 236 | 20·0 |

| 2 | 38 330 | 20·0 | 91 430 | 20·0 |

| 3 | 38 278 | 20·0 | 91 830 | 20·0 |

| 4 | 38 351 | 20·0 | 82 000 | 20·0 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 38 261 | 20·0 | 91 578 | 20·0 |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| White-British | 110 235 | 57·6 | 304 068 | 66·2 |

| White-Irish | 1210 | 0·6 | 1215 | 0·3 |

| White-other | 28 148 | 14·7 | 41 864 | 9·1 |

| Mixed: white and black Caribbean | 1163 | 0·6 | 4932 | 1·1 |

| Mixed: white and black African | 1150 | 0·6 | 3892 | 0·8 |

| Mixed: white and Asian | 851 | 0·4 | 5203 | 1·1 |

| Mixed: other | 1482 | 0·8 | 8114 | 1·8 |

| Indian | 8047 | 4·2 | 14 809 | 3·2 |

| Pakistani | 8900 | 4·7 | 18 816 | 4·1 |

| Bangladeshi | 5181 | 2·7 | 9475 | 2·1 |

| Asian other | 5546 | 2·9 | 10 293 | 2·2 |

| Black Caribbean | 2035 | 1·1 | 3511 | 0·8 |

| Black African | 8296 | 4·3 | 14 098 | 3·1 |

| Black other | 2310 | 1·2 | 6530 | 1·4 |

| Chinese | 2107 | 1·1 | 2754 | 0·6 |

| ‘Other’ ethnic group | 4872 | 2·5 | 9500 | 2·1 |

Pertussis coverage

Crude coverage in the sample was 57·4% (95% CI 57·2–57·6), which compared with 56·4% (95% CI 56·3–56·5) national coverage calculated using all extracted data. Coverage varied up to 16·6% across LTs, from 49·5% in London to 66·1% in Cumbria and the North East (Table 3). After adjusting for IMD and ethnicity, differences in coverage reduced but persisted in all LTs with between 2·8% and 11·7% higher coverage, compared with London.

Table 3.

Crude coverage and adjusteda coverage differences of maternal pertussis vaccination by and between socio-demographic groups, April 2014–March 2015

| No. patients | No. vaccinated | % Crude coverage | −/+95% CI | % Adjusted coverage differencea | −/+95% CI | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 191 533 | 109 927 | 57·4 | 57·2 | 57·6 | n/a | |||

| NHS England local team | |||||||||

| London | 54 724 | 27 080 | 49·5 | 49·1 | 49·9 | (ref) | |||

| Central Midlands | 8560 | 5454 | 63·7 | 62·7 | 64·7 | 6·2 | 5·0 | 7·3 | <0·001 |

| Cheshire and Merseyside | 8970 | 5705 | 63·6 | 62·6 | 64·6 | 10·5 | 9·4 | 11·6 | <0·001 |

| Cumbria and North East | 6846 | 4528 | 66·1 | 65 | 67·3 | 11·7 | 10·5 | 12·9 | <0·001 |

| East | 5429 | 3267 | 60·2 | 58·9 | 61·5 | 4·7 | 3·3 | 6·1 | <0·001 |

| Lancashire and Great Manchester | 20 052 | 11 246 | 56·1 | 55·4 | 56·8 | 5·2 | 4·3 | 6·0 | <0·001 |

| North Midlands | 9511 | 6123 | 64·4 | 63·4 | 65·3 | 9·6 | 8·5 | 10·6 | <0·001 |

| South Central | 15 235 | 9200 | 60·4 | 59·6 | 61·2 | 3·0 | 2·0 | 3·9 | <0·001 |

| South East | 14 725 | 8799 | 59·8 | 59 | 60·5 | 2·8 | 1·9 | 3·8 | <0·001 |

| South West | 10 308 | 6322 | 61·3 | 60·4 | 62·3 | 6·2 | 5·2 | 7·3 | <0·001 |

| Wessex | 9083 | 5891 | 64·9 | 63·9 | 65·8 | 7·0 | 5·9 | 8·2 | <0·001 |

| West Midlands | 20 320 | 11 404 | 56·1 | 55·4 | 56·8 | 5·4 | 4·5 | 6·2 | <0·001 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 7770 | 4908 | 63·2 | 62·1 | 64·2 | 9·9 | 8·7 | 11·1 | <0·001 |

| IMD quintile | |||||||||

| 1 (0·85–10·65) | 38 313 | 25 180 | 65·7 | 65·2 | 66·2 | (ref) | |||

| 2 (10·7–18·6) | 38 330 | 23 263 | 60·7 | 60·2 | 61·2 | −4·7 | −4·0 | −5·4 | <0·001 |

| 3 (18·7–28·3) | 38 278 | 22 179 | 57·9 | 57·5 | 58·4 | −6·4 | −5·7 | −7·1 | <0·001 |

| 4 (28·4–40·82) | 38 351 | 20 415 | 53·2 | 52·8 | 53·7 | −9·9 | −9·1 | −10·6 | <0·001 |

| 5 (40·83–46·4) | 38 261 | 18 890 | 49·4 | 48·9 | 49·9 | −14·0 | −13·2 | −14·8 | <0·001 |

| Ethnic group | |||||||||

| White-British | 110 235 | 69 016 | 62·6 | 62·3 | 62·9 | (ref) | |||

| White-Irish | 1210 | 670 | 55·4 | 52·6 | 58·2 | −4·4 | −7·2 | −1·6 | 0·002 |

| White-other | 28 148 | 13 882 | 49·3 | 48·7 | 49·9 | −9·6 | −10·3 | −8·9 | <0·001 |

| Mixed: white and black Caribbean | 1163 | 533 | 45·8 | 43·0 | 48·7 | −11·5 | −14·4 | −8·7 | <0·001 |

| Mixed: white and black African | 1150 | 512 | 44·5 | 41·6 | 47·4 | −12·8 | −15·7 | −9·9 | <0·001 |

| Mixed: white and Asian | 851 | 452 | 53·1 | 49·8 | 56·5 | −6·1 | −9·4 | −2·7 | <0·001 |

| Mixed: other | 1482 | 734 | 49·5 | 47·0 | 52·1 | −8·7 | −11·3 | −6·2 | <0·001 |

| Indian | 8047 | 4855 | 60·3 | 59·3 | 61·4 | 1·7 | 0·6 | 2·8 | 0·003 |

| Pakistani | 8900 | 4363 | 49·0 | 48·0 | 50·1 | −7·7 | −8·9 | −6·6 | <0·001 |

| Bangladeshi | 5181 | 2951 | 57·0 | 55·6 | 58·3 | 3·3 | 1·8 | 4·7 | <0·001 |

| Asian other | 5546 | 3090 | 55·7 | 54·4 | 57·0 | −2·6 | −4·0 | −1·3 | <0·001 |

| Black Caribbean | 2035 | 798 | 39·2 | 37·1 | 41·3 | −15·4 | −17·6 | −13·2 | <0·001 |

| Black African | 8296 | 3767 | 45·4 | 44·3 | 46·5 | −9·4 | −10·5 | −8·2 | <0·001 |

| Black other | 2310 | 876 | 37·9 | 35·9 | 39·9 | −16·3 | −18·3 | −14·2 | <0·001 |

| Chinese | 2107 | 1311 | 62·2 | 60·1 | 64·3 | 3·0 | 1·0 | 5·1 | 0·004 |

| ‘Other’ ethnic group | 4872 | 2117 | 43·5 | 42·1 | 44·8 | −13·7 | −15·2 | −12·3 | <0·001 |

Adjusted for NHS England LT, IMD quintile and ethnic group.

There was a gradient of decreasing coverage with increasing deprivation, with 14·0% lower coverage in patients in the most deprived quintile compared with the least deprived quintile, after adjusting for LT and ethnicity. Compared with other ethnicities, the gradient by IMD was less apparent among Bangladeshi, Pakistani and black-Caribbean groups, although the number of individuals for specific IMD bands in these groups was small.

Compared with white-British (62·6% crude coverage, 95% CI 62·3–62·9), pregnant women of all other ethnicities had lower crude coverage (−0·4% (Chinese) to −24·7% (black-other, Table 3). After adjusting for IMD and LT, differences in ethnicity decreased but persisted in most groups, except among Indian, Bangladeshi and Chinese groups who had higher coverage than white-British women (Table 3). The largest differences in coverage were in black-other and black-Caribbean women (−16·3% and −15·4%, respectively).

Rotavirus coverage

For two doses of vaccine, crude coverage in the sample was 86·7% (95% CI 86·6–86·8), which compared with national coverage of 87·4% (95% CI 87·4–87·5) when calculated using all extracted data. Coverage ranged from 82·7% in London to 91·9% in Cumbria and the North East LT (Table 4). After adjusting for IMD and ethnicity, the magnitude of the difference in coverage between London LT and other LTs was reduced, however with the exception of South West LT, all LTs still had significantly higher coverage, ranging from 1·6% to 6·5% higher.

Table 4.

Crude coverage and adjusteda coverage differences of completing doses of infant rotavirus vaccination by and between socio-demographic groups, January 2014 to June 2016

| No. patients | No. vaccinated | % crude coverage | −/+ 95% CI | % adjusted coverage differencea | −/+ 95% CI | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 459 074 | 398 187 | 86·7 | 86·6 | 86·8 | ||||

| NHS England local team | |||||||||

| London | 131 225 | 108 500 | 82·7 | 82·5 | 82·9 | (ref) | |||

| Central Midlands | 21 484 | 19 236 | 89·5 | 89·1 | 89·9 | 3·0 | 2·5 | 3·5 | <0·001 |

| Cheshire & Merseyside | 25 181 | 22 191 | 88·1 | 87·7 | 88·5 | 3·2 | 2·7 | 3·6 | <0·001 |

| Cumbria & North East | 20 211 | 18 575 | 91·9 | 81·5 | 92·3 | 6·5 | 6·0 | 6·9 | <0·001 |

| East | 14 665 | 13 058 | 89·0 | 88·5 | 89·5 | 3·0 | 2·5 | 3·6 | <0·001 |

| Lancashire & Gtr. Manchester | 44 997 | 39 407 | 87·6 | 87·3 | 87·9 | 3·9 | 3·5 | 4·3 | <0·001 |

| North Midlands | 22 072 | 19 824 | 89·8 | 89·4 | 90·2 | 4·0 | 3·5 | 4·4 | <0·001 |

| South Central | 31 111 | 27 505 | 88·4 | 88·0 | 88·8 | 2·4 | 2·0 | 2·8 | <0·001 |

| South East | 28 398 | 24 965 | 87·9 | 87·5 | 88·3 | 1·6 | 1·1 | 2·0 | <0·001 |

| South West | 29 243 | 25 098 | 85·8 | 85·4 | 86·2 | 0·3 | 0·2 | 0·8 | 0·195 |

| Wessex | 21 396 | 19 324 | 90·3 | 89·9 | 90·7 | 3·7 | 3·3 | 4·2 | <0·001 |

| West Midlands | 49 025 | 42 719 | 87·1 | 86·8 | 87·4 | 3·5 | 3·2 | 3·9 | <0·001 |

| Yorkshire & Humber | 20 066 | 17 785 | 88·6 | 88·2 | 89·1 | 3·6 | 3·1 | 4·1 | <0·001 |

| IMD quintile | |||||||||

| 1 (0·85–10·65) | 92 236 | 82 267 | 89·2 | 89·0 | 89·4 | (ref) | |||

| 2 (10·7–18·6) | 91 430 | 81 319 | 88·9 | 88·7 | 89·1 | −0·1 | −0·4 | −0·2 | 0·598 |

| 3 (18·7–28·3) | 91 830 | 80 119 | 87·2 | 87·0 | 87·5 | −0·9 | −1·3 | −0·6 | <0·001 |

| 4 (28·4–40·82) | 92 000 | 77 876 | 84·6 | 84·4 | 84·9 | −2·7 | −3·0 | −2·4 | <0·001 |

| 5 (40·83–46·4) | 91 578 | 76 606 | 83·7 | 83·4 | 83·9 | −4·4 | −4·7 | −4·0 | <0·001 |

| Ethnic group | |||||||||

| White-British | 304 068 | 270 668 | 89·0 | 88·9 | 89·1 | (ref) | |||

| White-Irish | 1215 | 943 | 77·6 | 75·3 | 80·0 | −9·7 | −12·1 | −7·4 | <0·001 |

| White-Other | 41 864 | 33 940 | 81·1 | 80·7 | 81·4 | −6·2 | −6·6 | −5·8 | <0·001 |

| Mixed: White & Black Caribbean | 4932 | 4003 | 81·2 | 80·1 | 82·2 | −6·0 | −7·1 | −4·9 | <0·001 |

| Mixed: White & Black African | 3892 | 3325 | 85·4 | 84·3 | 86·5 | −1·6 | −2·8 | −0·5 | 0·004 |

| Mixed: White & Asian | 5203 | 4454 | 85·6 | 84·7 | 86·6 | −2·3 | −3·2 | −1·3 | <0·001 |

| Mixed: Other | 8114 | 6644 | 81·9 | 81·0 | 82·7 | −5·2 | −6·0 | −4·4 | <0·001 |

| Indian | 14 809 | 12 799 | 86·4 | 85·9 | 87·0 | −1·3 | −1·8 | −0·7 | <0·001 |

| Pakistani | 18 816 | 15 606 | 82·9 | 82·4 | 83·5 | −4·4 | −5·0 | −3·8 | <0·001 |

| Bangladeshi | 9475 | 8000 | 84·4 | 83·7 | 85·2 | −1·2 | −2·0 | −0·4 | 0·003 |

| Asian Other | 10 293 | 8739 | 84·9 | 83·7 | 85·2 | −2·4 | −3·1 | −1·7 | <0·001 |

| Black Caribbean | 3511 | 2681 | 76·4 | 75·0 | 77·8 | −9·3 | −10·7 | −7·9 | <0·001 |

| Black African | 14 098 | 11 819 | 83·8 | 83·2 | 84·4 | −2·0 | −2·7 | −1·4 | <0·001 |

| Black Other | 6530 | 5201 | 79·6 | 78·7 | 80·6 | −6·1 | −7·1 | −5·1 | <0·001 |

| Chinese | 2754 | 2388 | 86·7 | 85·4 | 88·0 | −0·8 | −2·1 | −0·5 | 0·239 |

| ‘Other’ Ethnic Group | 9500 | 6977 | 73·4 | 72·5 | 74·3 | −13·0 | −13·9 | −12·1 | <0·001 |

Adjusted for NHS England LT, IMD quintile and ethnic group.

There was a gradient of decreasing coverage with increasing deprivation, with 4·4% lower coverage in patients in the most deprived quintile compared with the least deprived quintile after adjusting for LT and ethnicity (Table 4). However, this gradient was not observed for Chinese, black-African or Bangladeshi infants.

Compared with white-British infants (89·0% crude coverage, 95% CI 88·9–89·1), infants of all other ethnicities had lower crude coverage (−2·3% (Chinese) to −15·6% (‘other’ ethnic group)). After adjusting for IMD and LT, differences in coverage by ethnicity decreased but persisted in all groups except the Chinese ethnic group. The largest differences in coverage remained in the ‘other’ ethnic group, black-Caribbean and white-Irish infants compared with white-British infants (Table 4).

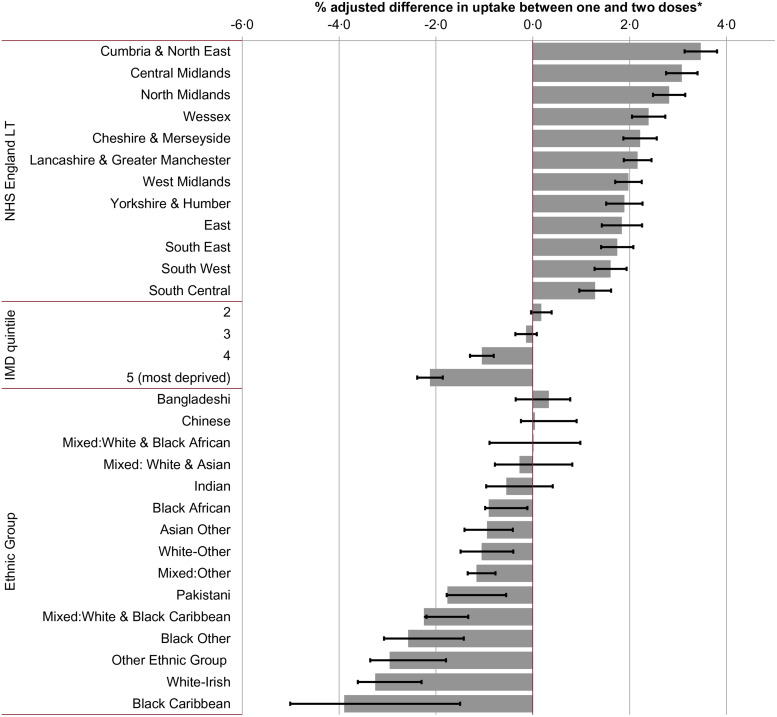

Among infants who had received the first dose of the two-dose rotavirus course, all LTs outside of London had a greater proportion of infants completing the schedule, ranging from 1·3% infants in South Central LT to 3·5% in Cumbria and North East LT (Fig. 1). A gradient of decreasing completion among primed infants was observed with increasing deprivation. Infants of mixed white and black-African; mixed white and Asian; Bangladeshi; and Chinese ethnicity had no significant difference in completion compared with white-British infants. Black-Caribbean (−3·9%, 95% CI −5·0 to −1·5), white-Irish (−3·3%, 95% CI −3·6 to −2·3) and those recorded as ‘other’ ethnic group (−3·0%, 95% CI−3·4 to −1·8) had the greatest difference in completion compared with white-British infants.

Fig. 1.

Percentage difference between initiation and completion of the infant rotavirus vaccination schedule adjusted for socio-demographic factors1,2. (1) Adjusted for NHS England Area Team, ethnic group and IMD quintile. (2) Reference categories were London NHS LT; IMD quintile 1 (least deprived) and white-British ethnicity.

DISCUSSION

The relatively high crude national coverage achieved following implementation of these new vaccine programmes masks wide variation among socio-demographic groups, which was more extreme for the maternal pertussis programme than the infant rotavirus vaccination programme. The ability to highlight inequalities in vaccine coverage by ethnicity at national level using routine surveillance data is a rare and important feature of the English surveillance system that helps to ensure compliance with the Equality Act 2010. Differences were most prominent between ethnic groups, with adjusted coverage varying up to 16% for the maternal pertussis programme and 14% for the infant rotavirus programme. Compared with white-British infants, infants of certain ethnic minorities were both less likely to initiate rotavirus vaccination, and of those who did, were less likely to complete their course. Adjusted coverage also declined significantly with increasing relative deprivation but was much greater in magnitude for the maternal programme compared with the infant programme.

The delivery of immunisation programmes in England is likely to impact upon measured coverage. Routine antenatal care is delivered through midwife-led maternity services and a recent survey indicated that 58% of women received antenatal care solely from midwifes [26]. Identifying and offering eligible women timely vaccination through GPs is reliant on the timely exchange of information between antenatal services and GPs, and creates potential for missed opportunities for vaccination at the recommended stage in pregnancy [27]. Further, measurement of coverage through GP data relies on maternity service-delivered immunisations being recorded on GP records. The substantially lower coverage observed in London, which has been observed consistently over time across all vaccine programmes, may reflect the challenges of delivering care in a large diverse city with a mobile population. However, the delivery of rotavirus vaccination alongside routine immunisations in childhood using well-established recall systems, may in part mitigate some of these challenges, explaining the higher coverage overall and the lower inequality in coverage of this infant programme, when compared with the maternal pertussis programme.

Attitudinal studies on maternal vaccination indicate that barriers to vaccination include perceived low risk of disease to the mother and infant, concerns about safety or lack of trust in the vaccination [28, 29]. Women of Bangladeshi, Chinese and Indian ethnicity had the highest coverage of maternal pertussis vaccination while women who were black-other, black-Caribbean and ‘other’ ethnicity had the lowest coverage. These findings are consistent with previous, smaller studies on vaccination in pregnancy in England [16, 18, 30], and a recent study which indicated that white-British women had a more positive attitude to vaccination in pregnancy than all other ethnic groups, although these groups were not delineated into specific ethnic groups [31]. Women of black-African, Caribbean and Pakistani ethnicity have been shown to have higher rates of both maternal morbidity and mortality [32], and studies have demonstrated that these groups engage less with antenatal services and access care later in pregnancy, which may explain missed opportunities for advocacy and delivery of vaccination [26, 33, 34]. The reason for the higher observed coverage in women from Indian and Bangladeshi origin in particular is unclear.

For the infant rotavirus programme, black-Caribbean infants had much lower coverage than all other infants, which has been demonstrated for routine childhood immunisations previously [18, 20]. Among the elderly population in England, shingles vaccine coverage is substantially lower among black-other, black-African and black-Caribbean patients than white-British patients [35], and indicates that underimmunisation among these ethnicities is not confined to vaccination in childhood or pregnancy but to immunisation more widely. This is likely to be reflective of both differences in attitude to vaccination and in access to services. Furthermore, all written information pertaining to vaccinations are in English, representing a barrier to vaccination for all vaccination programmes for those who do not understand English.

Rotavirus vaccination is bound by strict timescales; for the first dose, infants must be aged 6 weeks and the full course of two doses of vaccine needs to be completed before 16 weeks of age, allowing at least 4 weeks between doses. Children presenting later will remain unvaccinated, and if a child is not vaccinated with the first dose early enough, it is not possible for them to complete their schedule. In our study, infants of most non-white-British ethnicities, particularly white-Irish and black-Caribbean, had significantly lower completion rates for rotavirus vaccination than white-British infants. Children of these ethnicities are therefore not only less likely to initiate vaccination, but those who did were less likely to complete their course. A previous study examining reasons for partial immunisation of infants found the primary reasons were mainly medical and/or problems with access [18]. Timeliness of medical reasons (e.g. colds and common childhood illnesses) would not be expected to differ between ethnic groups, and it can be inferred that issues with access disproportionately affect particular ethnic groups, and in the case of rotavirus, vaccination may be in part due to these groups engaging later for receipt of the first dose scheduled at 8 weeks. This inequality in access may also be a factor in explaining the decreasing completion among infants living in areas of increasing deprivation observed here and elsewhere [14, 17, 19].

Adjusted coverage declined significantly with increasing relative deprivation, but this decline was much larger for the maternal programme vs. The infant programme. However, in both programmes, the clear gradient of declining coverage with deprivation for white-British patients that was not seen across all ethnic groups. This is consistent with a previous study, which concluded that social deprivation presented a unique disadvantage to infants born to white mothers in deprived areas [16]. Conversely, factors other than relative deprivation play a role in determining lower coverage among ethnic minority groups.

This is the first assessment of equity of delivery of these two recently implemented vaccination programmes in England, and to our knowledge, the first study assessing coverage inequalities on a national scale for either a maternal or routine infant immunisation programme. The large size of the study enables sufficient power to adequately assess differences between groups. The availability of ethnicity data at 2001 census level categories offered further insight into the differences among unique ethnicities, which previous studies have grouped into larger categories, or as black minority ethnic (BME) or non-BME groups. More granular data, including country of birth, would benefit locally targeted interventions to improve coverage among subgroups, and could provide further understanding of the barriers to vaccination in those individuals.

There are several limitations to the data used in this study. First, LT and IMD were assigned to individuals based on their GP and our results therefore could suffer from ecological bias. Second, the completeness of ethnicity recording using the ONS 2001 census categories is poor, and only practices with complete ethnicity recording were included. However, patients in our samples were comparable with population estimates in terms of IMD and ethnicity, all areas were represented, and overall coverage in the samples were broadly comparable with national estimates. Our findings are therefore likely to be representative of the general population. Lastly, it was not possible to assess the effects of other factors such as religion and rurality, which have previously been found to influence vaccine coverage [15, 17].

Despite these limitations, it is clear that there are marked inequalities between ethnic groups in the coverage of these two vaccination programmes, and the drivers behind those inequalities are complex and multifactorial. Qualitative research to further understand specific barriers in each community will ensure interventions to improve coverage are tailored and targeted at those most in need.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors would like to acknowledge all staff in PHE and NHS England responsible for the planning and delivery of the maternal pertussis and infant rotavirus immunisation programmes. The authors thank the ImmForm team for their management of the GP sentinel data collections and Vanessa Saliba and Karen Tiley for their work on vaccine coverage and collection of ethnicity data.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Briand V, Bonmarin I, Levy-Bruhl D. Study of the risk factors for severe childhood pertussis based on hospital surveillance data. Vaccine 2007; 25: 7224–7232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall H, et al. Predictors of disease severity in children hospitalized for pertussis during an epidemic. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2015; 34: 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health Protection Agency. Confirmed Pertussis in England and Wales Continues to Increase. Health Protection Report, 2012, London. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. Pregnant women to be offered whooping cough vaccination. 2012. News story. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pregnant-women-to-be-offered-whooping-cough-vaccination.

- 5.Public Health England. The green book: immunisation against infectious disease, Chapter 24-“Pertussis” [Internet]. London: PHE; 2013. Available from:, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/514363/Pertussis_Green_Book_Chapter_24_Ap2016.pdf.

- 6.Public Health England. Vaccination against pertussis (whooping cough) for pregnant women – 2016. Information for healthcare professionals. 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaccination-against-pertussis-whooping-cough-for-pregnant-women.

- 7.Public Health England. The complete routine immunisation schedule. 2016. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaccination-against-pertussis-whooping-cough-for-pregnant-women.

- 8.Public Health England. National rotavirus immunisation programme: preliminary data for England, February 2014 to July 2015. Health Protection Report 2015; 9. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/457925/hpr3015_rtvrs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amirthalingam G, et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet 2014; 384: 1521–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Hoek AJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness and programmatic benefits of maternal vaccination against pertussis in England. Journal of Infection 2016; 73: 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Public Health England. National rotavirus immunisation programme update: preliminary vaccine coverage for England, August 2015 to January 2016. Health Protection Report 2016; 10. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/503761/hpr0816_rtvrs-vc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Public Health England. Pertussis Vaccination Programme for Pregnant Women update: vaccine coverage in England, January to march 2016. Health Protection Report 2017; 11. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/616198/hpr1917_prntl-prtsssVC.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS England. Public health section 7A commissioning intentions 2015/16. 2014. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2014/12/ph-comms-intent-15-16.pdf.

- 14.Wagner KS, et al. Childhood vaccination coverage by ethnicity within London between 2006/2007 and 2010/2011. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2014; 99: 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Lier A, et al. Vaccine uptake determinants in The Netherlands. European Journal of Public Health 2014; 24: 304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker D, Garrow A, Shiels C. Inequalities in immunisation and breast feeding in an ethnically diverse urban area: cross-sectional study in Manchester, UK. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2011; 65: 346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green HK, et al. Phased introduction of a universal childhood influenza vaccination programme in England: population-level factors predicting variation in national uptake during the first year, 2013/14. Vaccine 2015; 33: 2620–2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samad L, et al. Differences in risk factors for partial and no immunisation in the first year of life: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2006; 332: 1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brien S, et al. Neighborhood determinants of 2009 pandemic A/H1N1 influenza vaccination in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. American Journal of Epidemiology 2012; 176: 897–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawker JI, et al. Widening inequalities in MMR vaccine uptake rates among ethnic groups in an urban area of the UK during a period of vaccine controversy (1994–2000). Vaccine 2007; 25: 7516–7519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Public Health England. Prenatal pertussis immunisation programme 2014/15: annual vaccine coverage report for England. 2015. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pertussis-vaccine-coverage-in-pregnant-women-april-2014-to-march-2015.

- 22.Public Health England. Rotavirus infant immunisation programme 2014/15: vaccine uptake report on the temporary sentinel data collection for England. 2015. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rotavirus-vaccine-uptake-report-for-england.

- 23.Office for National Statistics. 2011. Super Output Area (SOA). Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160106001702tf_/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/geography/beginner-s-guide/census/super-output-areas--soas-/index.html.

- 24.Office for National Statistics. Live births. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths In.

- 25.NHS Digital. NHS Maternity Statistics, England, 2014. –15: NHS Maternity Statistics Tables. 2015. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB19127.

- 26.Redshaw M, Henderson J. Safely Delivered: A National Survey of Women's Experience of Maternity Care 2014. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Oxford: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amirthalingam G, et al. Lessons learnt from the implementation of maternal immunisation programs in England. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 2016; 12: 2934–2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng PJ, et al. Factors influencing women's decisions regarding pertussis vaccine: a decision-making study in the Postpartum Pertussis Immunization Program of a teaching hospital in Taiwan. Vaccine 2010; 28: 5641–5647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins J, et al. Increased awareness and health care provider endorsement is required to encourage pregnant women to be vaccinated. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 2014; 10: 2922–2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donaldson B, et al. What determines uptake of pertussis vaccine in pregnancy? A cross sectional survey in an ethnically diverse population of pregnant women in London. Vaccine 2015; 33: 5822–5828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell H, et al. Attitudes to immunisation in pregnancy among women in the UK targeted by such programmes. British Journal of Midwifery 2015; 23: 566–573. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nair M, Kurinczuk JJ, Knight M. Ethnic variations in severe maternal morbidity in the UK – a case control study. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e95086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson J, Gao H, Redshaw M. Experiencing maternity care: the care received and perceptions of women from different ethnic groups. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2013; 13: 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knight M, et al. Inequalities in maternal health: national cohort study of ethnic variation in severe maternal morbidities. BMJ 2009; 338: b542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Public Health England. Herpes zoster (shingles) immunisation programme 2013 to 2014: report for England. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/herpes-zoster-shingles-immunisation-programme-2013-to-2014-evaluation-report.