Abstract

Production of extracellular proteins plays an important role in the physiology of Trichoderma reesei and has potential industrial application. To improve the efficiency of protein secretion, we overexpressed in T. reesei the DPM1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encoding mannosylphosphodolichol (MPD) synthase, under homologous, constitutively acting expression signals. Four stable transformants, each with different copy numbers of tandemly integrated DPM1, exhibited roughly double the activity of MPD synthase in the respective endoplasmic reticulum membrane fraction. On a dry-weight basis, they secreted up to sevenfold-higher concentrations of extracellular proteins during growth on lactose, a carbon source promoting formation of cellulases. Northern blot analysis showed that the relative level of the transcript of cbh1, which encodes the major cellulase (cellobiohydrolase I [CBH I]), did not increase in the transformants. On the other hand, the amount of secreted CBH I and, in all but one of the transformants, intracellular CBH I was elevated. Our results suggest that posttranscriptional processes are responsible for the increase in CBH I production. The carbohydrate contents of the extracellular proteins were comparable in the wild type and in the transformants, and no hyperglycosylation was detected. Electron microscopy of the DPM1-amplified strains revealed amorphous structure of the cell wall and over three times as many mitochondria as in the control. Our data indicate that molecular manipulation of glycan biosynthesis in Trichoderma can result in improved protein secretion.

The saprophytic fungus Trichoderma reesei secretes a wide range of enzymes such as cellulases or hemicellulases, which are of considerable biotechnical importance in the food, feed, and paper industries (10). Despite the progress that has been made in studies of the enzymology and molecular biology of Trichoderma hydrolytic proteins (37), the pathway of protein secretion and its regulation are still poorly understood (1, 34). The presence of cleavage sites for the signal peptidase and a Kex2-like dipeptidyl peptidase in many cellulase prepropeptides (2, 7), the results of immunoelectron microscopy (6, 22), and the recent cloning of a sar1 homologue (39) support the hypothesis that the T. reesei secretory pathway involves transport from the endoplasmic reticulum through the Golgi complex to the plasma membrane.

Many extracellular proteins of fungi are glycosylated, and for the cellulolytic enzymes, there is indirect evidence that O glycosylation may be essential for secretion (19). O glycosylation in T. reesei and other fungi occurs by the dolichol pathway (14, 23, 38). This pathway differs from other eukaryotic O-glycosylation by the involvement of phosphodolichol as a carrier lipid and by the fact that transfer of the first mannosyl residue occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (11).

We have suggested previously (15) that mannosylphosphodolichol synthase (MPD synthase; EC 2.4.1.8.80) plays a key role in T. reesei O glycosylation and is activated by cyclic AMP-dependent phosphorylation (16). The protein and the gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (DPM1) have been characterized elsewhere (12, 32). Loss of DPM1 expression is lethal (32). Successful attempts to clone homologues of S. cerevisiae DPM1 from T. reesei or other filamentous fungi have yet to be reported (29). In an S. cerevisiae temperature-sensitive dpm1 mutant (33), the MPD synthase is required for O mannosylation and participates in N glycosylation of proteins as a donor of the last four mannosyl residues during the assembly of the lipid-linked precursor oligosaccharide, i.e., dolichylpyrophosphate GlcNac2Man9Glc3, and is required for the biosynthesis of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchor (13). Cloned MPD synthases from human tissues and Schizosaccharomyces pombe both encode a separate MPD synthase class that lacks the C-terminal hydrophobic domain (4), which is otherwise typical for S. cerevisiae, Ustilago maydis (42), and Trypanosoma brucei. The major difference between the two classes is that in the S. cerevisiae group a single component (Dpm1p) has MPD synthase activity whereas in mammalian cells MPD synthase activity is mediated by two proteins, i.e., catalytic Dpm1 and regulatory Dpm2 (28).

Based on our previous findings that MPD synthase activity in T. reesei is related to the level of protein secretion (15, 17), we determined whether overexpression of DPM1 resulted in enhanced cellulase secretion. Such an increase would improve the secretion of other O-glycosylated proteins. We have overexpressed S. cerevisiae DPM1 in T. reesei and examined its effect on protein glycosylation and secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and conditions for growth.

T. reesei TU-6, a Δpyr4 mutant of T. reesei QM 9414 (10), was used as the recipient for transformation. Escherichia coli JM 109 was used for plasmid propagation (41).

T. reesei was cultivated in 2-liter shake flasks containing 1 liter of minimal medium, i.e., 1 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 6 g of (NH4)2SO4, 10 g of KH2PO4, 3 g of Na citrate · 2H2O, microelements (90 μM FeSO4, 20 μM MnCl2, 20 μM ZnSO4, 100 μM CaCl2, final concentrations in the medium), and 1% lactose as a carbon source, as specified for the experiments, at 28°C on a rotary shaker (250 rpm).

Preparation of cell extracts.

Mycelia were harvested by filtration, washed with ice-cold tap water, dried, and suspended in 50 mM citrate buffer, pH 5.0 (10 ml/g [wet weight]). Cell extracts were prepared by ultrasonication of the suspension. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g (15 min, 4°C), and the supernatant (typically containing 2 to 4 mg of protein per ml) was used for Western blot analysis.

Expression of S. cerevisiae DPM1 in T. reesei.

To amplify S. cerevisiae DPM1 in T. reesei, we introduced the gene into T. reesei fused to the regulatory signals of the pki1 (pyruvate kinase-encoding) gene (36). Thus, the complete coding sequence of the S. cerevisiae DPM1 gene was amplified by PCR, with an Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Boehringer-Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). The oligonucleotides Dpm1s (5′-GCTCTAGAATGAGCATCGAATACTCTGTAA-3′) and Dpm1r (5′-GCTCTAGATTAAAAGACCAAATGGTATAGC-3′) were used as forward and reverse primers, respectively. Both primers had XbaI restriction sites attached to both ends to facilitate subsequent cloning. The reaction mixture for amplification contained 1 mM primers, 250 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, Expand high-fidelity reaction buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.6 U of enzyme mix, and H2O to a total of 50 μl. Twenty nanograms of plasmid pDM8 (32) was used as a template. The temperature program was as follows: denaturation at 96°C for 2 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and a final elongation at 72°C for 3 min. We obtained an 801-bp fragment that was sequenced and cloned into the XbaI site of pUC19 to yield pJSK1. Linearization of pJSK1 by SspI, partial digestion with XbaI, and complete cleavage with SalI generated an 0.8-kb XbaI/SalI fragment, which was subcloned into pLMRS3 (26) previously digested with SalI/XbaI to yield pDPMEX. This vector was introduced into T. reesei TU-6 (10) by cotransformation as described previously (20, 27), with 5 μg of pFG1 containing the T. reesei pyr4 gene (8) and 15 μg of pDPMEX. Further isolation of transformants was carried out as previously described (8).

Molecular biology methods.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from T. reesei by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction as described previously (8). Total RNA was isolated by a single-step method described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (3). Other molecular biological techniques were performed according to standard protocols (35).

Biochemical techniques.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, Western blotting, and immunological detection of secreted cellobiohydrolase I (CBH I) were carried out as described previously (31), by a chemiluminescence assay (ECL Western blot analysis system; Amersham Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). When intracellular CBH I was assayed, a secondary antibody was used to remove nonspecific antigens. The secondary antibody was incubated (30 min, 4°C) with T. reesei cell walls prepared as described elsewhere (30) at 1 mg/ml.

The presence of soluble polysaccharides and glycoproteins in the culture filtrate was assayed by the phenol-sulfuric acid procedure (5), with samples precipitated by 2 volumes of ethanol and resuspended in distilled water. The calibration curve was prepared with d-mannose. Protein was estimated according to the method of Lowry et al. (25).

Enzyme activity assay.

MPD synthase activity was assayed in a microsomal membrane fraction of T. reesei (14, 16).

Quantification of fungal dry weight.

Fungal dry weight was quantified by filtering culture through a coarse (G1 grade) sinter funnel, washing the fungal material with a threefold volume of tap water, and drying the material to a constant weight at 110°C.

Electron microscopy.

Mycelia of T. reesei JSK97/3 (transformed strain) and T. reesei JSK97/C (control strain) harvested after 200 h of cultivation were collected by centrifugation and prepared for electron microscopy as described previously (21) except that the procedure for immunolocalization was omitted. Ultrathin sections were examined under a JEM100C transmission electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV.

RESULTS

Construction of T. reesei strains overexpressing S. cerevisiae DPM1.

Our strategy to enhance the cellular MPD synthase activity was to introduce multiple copies of the S. cerevisiae DPM1 gene into T. reesei. To this end, we fused DPM1 under the 5′ regulatory signals of the T. reesei pki1 (pyruvate kinase-encoding) (36) gene, which allows a three- to fourfold increase in transcription (26). The resulting vector was introduced into T. reesei TU-6 by cotransformation, and prototrophic transformants were selected. Stable transformants were isolated by three rounds of transfer from selective to nonselective medium and screened by Southern hybridization for genomic copies of DPM1. Four such transformants (JSK97/1, -2, -3, and -6) were obtained. All of them carried integrated copies of the yeast gene. T. reesei JSK97/C, the control, i.e., a recipient TU-6 strain transformed with the pFG1 helper vector only, gave no signal with the DPM1 probe.

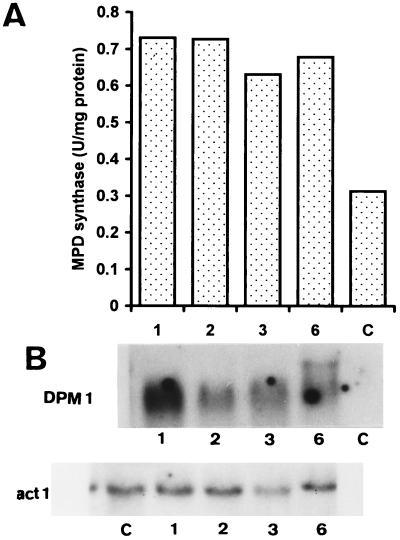

To determine if the heterologous DPM1 gene was correctly expressed and translated, we carried out Northern blot analysis and MPD synthase activity assays of the transformants (Fig. 1). As expected, no DPM1 transcript was detected in the JSK97/C control, but this transcript was detected in all of the transformants.

FIG. 1.

Transcription and function of the yeast DPM1 gene in T. reesei. (A) MPD synthase activity (given in picomoles of [U-14C]mannose incorporated into the lipid fraction per 5 min per milligram of protein) was measured in the membrane (50,000 × g) fraction from the control (strain C) and the transformants harboring the yeast DPM1 gene (strains 1, 2, 3, and 6). Values are means of at least five independent measurements, with a standard deviation of <5%. (B) Northern blot analysis of DPM1 mRNA. Equal amounts of total RNA (20 μg) from the control (C) strain and from the transformants (1, 2, 3, and 6) were loaded onto the gels, blotted, and probed with a 0.6-kb BanII fragment of the S. cerevisiae DPM1 gene. Loading controls, hybridized with a 1.9-kb KpnI fragment of the T. reesei act1 (actin-encoding) gene, are also shown.

MPD synthase activity of the transformants increased 2- to 2.5-fold over that of the control. This relatively low increase is not due to limiting amounts of GDP[14C]Man in the assay, since the use of a sixfold-higher concentration of GDP[14C]Man in the assay did not result in a higher ratio of activities of the transformants and the control strain (data not shown). The assay was carried out in the presence of exogenous dolichylphosphate (5 nmol) to ensure that sufficient lipid substrate was available for the increased amount of MPD synthase in the transformants.

Expression of the yeast MPD synthase-encoding gene in T. reesei.

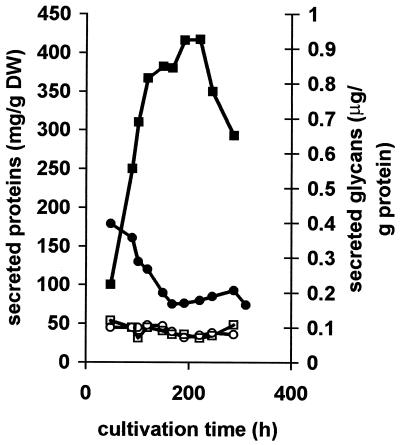

To determine if the doubled activity of MPD synthase influenced the rate of protein secretion or the final concentration of the secreted protein, we cultivated the transformants and the control strain on medium containing lactose as the sole carbon source and measured protein production (Fig. 2). All of the transformants secreted increased amounts of protein. The differences were most pronounced following extended cultivation and reached the maximum at 180 to 200 h. The effect was even more drastic when calculated per unit of cell mass (gram of fungal dry weight), reaching up to sevenfold-higher levels (Fig. 2). Note that the parental strain had only negligible amounts of cellulase activity within its cell wall (18) and that the increase in activity in the transformants could not be due to a more efficient release from or passage through the cell wall.

FIG. 2.

Effect of DPM1 overexpression on protein secretion by T. reesei. The figure shows the specific rate of protein secretion (milligrams of protein per gram of fungal dry weight, left axis) and the ratio of protein-bound carbohydrate to protein concentration (right axis). Open symbols, secreted glycans; solid symbols, secreted proteins; circles, control strain JSK97/C; squares, JSK97/3 transformant. The data shown are from a single experiment only; however, in at least five parallel experiments, similar patterns were observed. DW, dry weight.

Overexpression of MPD synthase might preferentially affect the amount of the secreted glycoproteins or their degree of glycosylation. We determined the concentration of total protein-bound carbohydrate in the medium and normalized it to the amount of protein (Fig. 2). The resulting values were comparable in the transformants and in the wild-type strain, leading us to conclude that overexpression of DPM1 does not affect the degree of glycosylation of the secreted proteins.

Cellulase formation in T. reesei strains overexpressing DPM1.

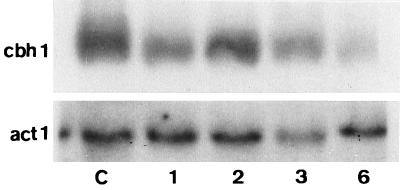

We made Northern blots of mRNA from all the transformants and hybridized them to a fragment of the cbh1 gene. CBH I accounts for more than 50% of total secreted protein in T. reesei and can be used as a marker for total cellulase formation. Despite the significant increase in cellulase formation, cbh1 transcript levels were not increased in the transformants (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Effect of DPM1 overexpression on cbh1 gene expression in T. reesei. Total RNA was isolated from the control (C) and the transformant (1, 2, 3, and 6) strains, and equal amounts (20 μg) were loaded onto agarose gels, blotted, and hybridized with a 1.5-kb BglI fragment of cbh1, randomly primed with [γ-32P]dATP. Actin controls were used as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

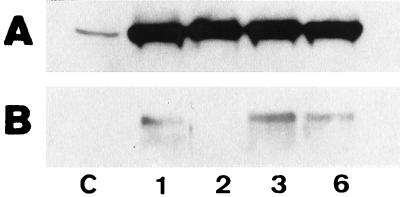

The results from Northern blotting suggested that a posttranscriptional process may be responsible for cellulase overproduction in the transformants. We determined the intra- and extracellular cellulase contents. CBH I was again used as the model. All but one of the transformants contained clearly detectable intracellular levels of CBH I, which were absent in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Effect of DPM1 overexpression on intra- and extracellular levels of CBH I. The presence of CBH I in the culture fluid (A) or in cell extracts (B) was analyzed by Western blotting and immunostaining. Equal volumes of the culture filtrate were loaded onto the gels for panel A, whereas equal amounts of protein (25 μg) were loaded onto the gels for panel B. Lane C, control strain; lanes 1, 2, 3, and 6, transformant strains.

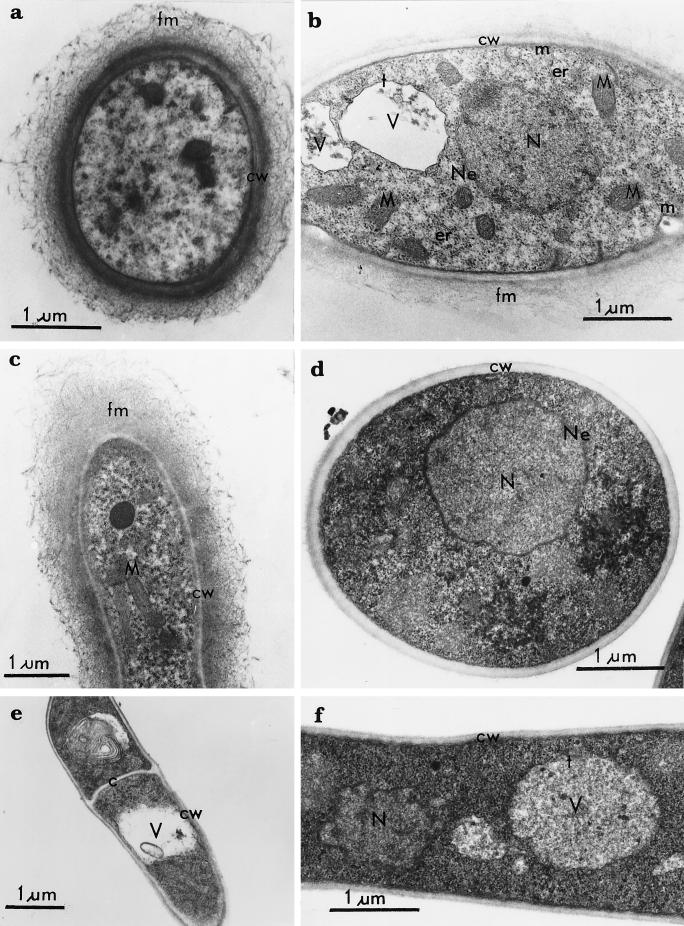

Cell ultrastructure of T. reesei strains overexpressing DPM1.

The JSK97/3 transformant, showing the highest rate of growth and protein secretion (per milliliter of medium), was subjected to electron microscopy and compared with the control (JSK97/C). Some essential differences were observed. The cell wall of T. reesei JSK97/3 has a clearly flocculous structure (Fig. 5a to c). The cytoplasm of the transformed cells was electron transparent, and the number of mitochondria, but not of vacuoles and nuclei, was three times higher than what we observed in the control (Table 1). The cell wall of the control JSK/97 C strain (Fig. 5d and e) showed a compact cell wall layer, and the cytoplasm was electron opaque and densely packed with ribosomes.

FIG. 5.

Effect of DPM1 overexpression on cellular ultrastructure of T. reesei. Ultrathin sections are shown from T. reesei transformant JSK97/3 (a to c) and the control strain JSK97/C (d to f). (a to c) Filamentous material at the surface of the cell wall; electron-transparent cytoplasm; mitochondria (b and c) and endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane (b). The cell wall of the control strain is composed of one compact layer, not covered by filamentous material, and the cytoplasm is electron opaque, showing cell wall, cross wall, nucleus, tonoplast, and vacuole. c, cross wall; cw, cell wall; er, endoplasmic reticulum; fm, filamentous material; m, plasma membrane; M, mitochondria; N, nucleus; Ne, nuclear envelope; t, tonoplast; V, vacuoles.

TABLE 1.

Ultrastructural differences between the T. reesei strain overexpressing the DPM1 gene, JSK97/3, and the control strain, JSK97/Ca

| Organelle | No. of organelles/100 cellular sections or characteristic

|

|

|---|---|---|

| JSK97/3 | JSK97/C | |

| Nucleus | 37 | 45 |

| Vacuole | 108 | 102 |

| Mitochondrion | 765 | 216 |

| Cytoplasm | Electron transparent | Electron opaque |

| Cell wall | Flocculous, amorphous | One compact layer |

Transformed and control strains were harvested after approximately 200 h of cultivation, at the time of highest rate of protein secretion.

DISCUSSION

Secretory pathways of filamentous fungi are widely studied. So far, however, no clear data on the regulation of secretion are available (1, 34). We improved protein secretion in T. reesei by overexpressing the yeast DPM1 gene, involved in biosynthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor and O mannosylation and N glycosylation of protein. CBH I contains both N- and O-linked mannose, and dolichyl phosphate is involved in O mannosylation in T. reesei (14, 34).

We have previously suggested that the O-mannosyl linkage is an essential or a rate-limiting step for cellulase secretion (15, 19). The present data are consistent with this hypothesis since higher levels of activity of MPD synthase, the key enzyme in the O-mannosylation reaction, correspond to increased levels of protein production-secretion.

The mechanism of this process, however, is not obvious. The extracellular proteins secreted by the parental strain and by the transformants overexpressing MPD synthase contain the same percentages of carbohydrate and are not overglycosylated. These results also are consistent either with a limiting role of O mannosylation in protein secretion or with tight control of the number of occupied sites in the nascent protein and the glycan chain length. Alternatively, O mannosylation of Aspergillus glucoamylase may limit the conformational space available to the unfolded peptide and help stabilize the folded protein (24, 40). If this explanation applies to T. reesei cellulases, then an increase in O mannosylation might increase protein production by slowing down the turnover of the nascent protein. This hypothesis is supported by our findings of higher intracellular levels of CBH I in the DPM1-amplified strains. However, no hyperglycosylated, secreted proteins were detected in the culture medium. The DPM1-transformed strains secreted most of their protein at a time of cultivation when the parent had already stopped protein secretion. Whether this behavior is related to the hypothesized effect on protein turnover is not known, but it could be related to other major physiological changes in the transformants.

We identified several such major changes in this study, e.g., alterations in cell wall architecture, increase in the number of mitochondria, and changes of the electron density of the cytoplasm in the DPM1-transformed strains (Table 1). The increase in the number of mitochondria was concomitant with a two- to threefold increase in activity of cytochrome c oxidase, a mitochondrial marker enzyme. Hardwick et al. (9) observed altered membrane organization in yeast strains overexpressing DPM1. These transformants accumulated small vesicles that were not observed in the present study with T. reesei. Hardwick et al. (9) reasoned that overexpression of MPD synthase deregulates dolichol metabolism and thereby alters the properties of endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi membranes; if this explanation is also true for T. reesei, it may give rise to a number of pleiotropic effects.

Our results from this study clearly show that overexpression of yeast DPM1 in T. reesei influences protein secretion. While at the cellular level the effect is not yet defined, to the best of our knowledge this is the first report of protein secretion in a filamentous fungus being increased by molecular genetic manipulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants (662699203 to J.S.K. and 6PO4B 01712 to G.P.) from the State Committee for Scientific Research (KBN), Warsaw, Poland, and by grants from the Ministry of Science and Research of Austria (GZ 49.694/3-II/A/4/1990) and from the Austrian Science Foundation (P 7542, 1990–1991) to C.P.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archer D, Peberdy J F. The molecular biology of secreted enzyme production in fungi. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1997;17:273–306. doi: 10.3109/07388559709146616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calmels T P G, Martin F, Durand H, Tiraby G. Proteolytic events in the processing of secreted proteins in fungi. J Biotechnol. 1991;17:51–66. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(91)90026-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colussi P A, Taron C H, Mach J, Orlean P. Human and Saccharomyces cerevisiae dolichyl phosphate mannose synthases represent two classes of the enzymes, but both function in Scizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7873–7878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glenn M, Ghosh A, Ghosh B K. Subcellular fractionation of a hypercellulolytic mutant Trichoderma reesei RUT C-30: localization of endoglucanase in microsomal fractions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:1137–1143. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.5.1137-1143.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goller S P, Schoisswohl D, Baron M, Parriche M, Kubicek C P. Role of endoproteolytic dibasic proprotein processing in maturation of secretory proteins in Trichoderma reesei. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3202–3208. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3202-3208.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruber F, Visser J, Kubicek C P, de Graaff L H. The development of a heterologous transformation system for the cellulolytic fungus Trichoderma reesei based on a pyrG-negative mutant strain. Curr Genet. 1990;18:71–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00321118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardwick K G, Boothroyd J C, Rudner A D, Pelham H R. Genes that allow yeast cells to grow in the absence of the HDEL receptor. EMBO J. 1992;11:4187–4195. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harman G E, Kubicek C P. Enzymes, biocontrol and commercial application. In: Harman G E, Kubicek C P, editors. Trichoderma and Gliocladium. Vol. 2. London, United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 1998. pp. 129–163. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haselbeck A, Tanner W. O-glycosylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is initiated at the endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 1983;158:335–338. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80608-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haselbeck A. Purification of GDP mannoase:dolichyl-phosphate O β-d-mannosyltransferase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur J Biochem. 1989;181:663–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herscovics A, Orlean P. Glycoprotein biosynthesis in yeast. FASEB J. 1993;7:540–550. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.6.8472892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruszewska J, Messner R, Kubicek C P, Palamarczyk G. O-glycosylation of protein by membrane fraction of Trichoderma reesei QM 9414. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:301–307. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruszewska J, Palamarczyk G, Kubicek C P. Stimulation of exoprotein secretion by choline and Tween 80 in Trichoderma reesei QM 9414 correlates with increased activities of dolichol phosphate mannose synthase. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1293–1298. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruszewska J, Palamarczyk G, Kubicek C P. Mannosyl-phospho-dolichyl synthase from Trichoderma reesei is activated by protein kinase dependent phosphorylation in vitro. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;80:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruszewska J, Kubicek C P, Palamarczyk G. Modulation of mannosylphosphodolichol synthase and dolichol kinase activity in Trichoderma reesei related to protein secretion. Acta Biochim Pol. 1994;41:331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubicek C P. Release of carboxymethyl-cellulase and β-glucosidase from cell-wall of Trichoderma reesei. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1981;13:226–231. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubicek C P, Panda T, Schreferl-Kunar G, Gruber F, Messner R. O-linked—but not N-linked—glycosylation is necessary for endoglucanase I and II secretion by Trichoderma reesei. Can J Microbiol. 1987;33:698–703. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubicek-Pranz E M, Gruber F, Kubicek C P. Transformation of Trichoderma reesei with the cellobiohydrolase II gene as a means for obtaining strains with increased cellulase production and specific activity. J Biotechnol. 1991;20:83–94. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurzątkowski W, Palissa H, Liempt H, Van Doehren H, Von Kleinkauf H, Wolf W P, Kurylowicz W. Localization of isopenicillin N synthase in Penicillium chrysogenum PQ 96. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;35:517–520. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurzątkowski W, Solecka J, Filipek J, Rozbicka B, Messner R, Kubicek C P. Ultrastructural localization of cellular compartments involved in secretion of the low molecular weight, alkaline xylanase by Trichoderma reesei. Arch Microbiol. 1993;159:417–422. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Letoublon R, Gott R. Role d’un intermediaire lipidique dans le transfert du mannose a des accepteurs glycoproteiques endogenes chez Aspergillus niger. FEBS Lett. 1974;46:214–217. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(74)80371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Libby C B, Cornett C A G, Reilly P J, Ford C. Effect of amino acid deletions in the O-glycosylated region of Aspergillus awamori glucamylase. Protein Eng. 1994;7:1109–1114. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.9.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mach, R. L. Unpublished results.

- 27.Mach R L, Schindler M, Kubicek C P. Transformation of Trichoderma reesei based on hygromycin B resistance using homologous expression signals. Curr Genet. 1994;25:567–570. doi: 10.1007/BF00351679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maeda Y, Tomita S, Watanabe R, Ohishi K, Kinoshita T. DPM2 regulates biosynthesis of dolichol phosphate-mannose in mammalian cells: correct subcellular localization and stabilization of DPM1, and binding of dolichol phosphate. EMBO J. 1998;17:4920–4929. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Messner, R., and C. P. Kubicek. Unpublished results.

- 30.Messner R, Hagspiel K, Kubicek C P. Isolation of a β-glucosidase binding and activating polysaccharide from cell-walls of Trichoderma reesei. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:150–155. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mischak H, Hofer F, Weissinger E, Messner R, Hayn M, Tomme P, Küchler E, Esterbauer H, Claeyssens M, Kubicek C P. Monoclonal antibodies against different domains of cellobiohydrolase I and II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;990:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(89)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orlean P, Albright H, Robbins P W. Cloning and sequencing of the yeast gene for dolichol phosphate mannose synthase, an essential protein. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17499–17507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orlean P. Dolichol phosphate mannose synthase is required in vivo for glycosyl phosphatidylinositol membrane anchoring, O-mannosylation, and N-glycosylation of protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5796–5805. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palamarczyk G, Maras M, Contreras R, Kruszewska J. Protein secretion and glycosylation in Trichoderma. In: Kubicek C P, Harman G E, editors. Trichoderma and Gliocladium. Vol. 1. London, United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 1998. pp. 120–138. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. pp. 7.37–7.52. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schindler M, Mach R L, Vollenhofer S K, Hodits R, Gruber F, Visser J, De Graaff L, Kubicek C P. Characterization of the pyruvate kinase-encoding gene (pki 1) of Trichoderma reesei. Gene. 1993;130:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90430-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suominen P, Rainikainen T. Trichoderma reesei cellulases and other hydrolases: enzyme structures, biochemistry, genetics and applications. Vol. 8. Helsinki, Finland: Fagepaino Oy; 1993. Foundation for Biotechnical and Industrial Fermentation Research publications. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanner W, Lehle L. Protein glycosylation in yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;906:81–99. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(87)90006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veldhuisen G, Saloheimo M, Fiers M A, Punt P J, Contreras R, Penttila M, van den Hondel C A. Isolation and analysis of functional homologues of the secretion-related SAR1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae from Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma reesei. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;256:446–455. doi: 10.1007/pl00008613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williamson G, Belshaw N J, Noel T R, Ring S G, Williamson M P. O-glycosylation and stability. Unfolding of glucamylase induced by heat and guanidine hydrochloride. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:661–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zimmermann J W, Specht C A, Cazares B X, Robbins P W. The isolation of a Dol-P-Man synthase from Ustilago maydis that functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1996;12:765–771. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19960630)12:8%3C765::AID-YEA974%3E3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]