Dear Editor,

Recently, Venturas et al. had reported in this Journal that HIV infection is neither a risk factor for moderate or severe COVID-19 nor for mortality.1 Moreover, Martin-Vicente described that people with HIV (PWH) presented similar levels of anti-SARS-Cov-2 antibodies compared to HIV-negative individuals.2

The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2, etiologic agent of COVID-19, has raised concerns around the world and Argentina was not the exception.3 PWH were, a priori, considered an at-risk population for severe COVID-19. As clinical and immunological data was generated, controversies emerged mainly because different studies included PWH with different progression rates and PWH on and off antiretrovirals (ART). Reports in line with Venturas et al. indicate that HIV infection is not a risk factor for severe COVID-19 as long as individuals are on-ART and have a preserved CD4+T cell count.4 In agreement with Martin-Vicente, others have shown that similar antibody responses can be achieved by PWH on ART with complete HIV suppression compared to HIV-uninfected individuals.5 However, lower conversion rates in PWH, compared to HIV-negative persons, were also reported by other researchers.6 , 7 In addition, memory cellular immunity could be assessed after SARS-CoV-2 infection in PWH7. Studies such as those of Venturas et al. 1 and Martin-Vicente et al.,2 are key to have a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of SARS-CoV-2 immunity in PWH, which is fundamental to apply health care strategies (including optimal vaccination strategies) tailored for this population.

In this line, we aimed to study the immune landscape that occurs after COVID-19 in PWH. To that, we performed a cross-sectional study. Between April and December 2020 peripheral blood samples from donors to the Argentinean Biobank of Infectious Diseases (BBEI) with confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were collected at convalescence: 29 PWH with preserved CD4+T-cell counts on ART and 29 HIV-negative individuals (HIVneg) were included. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Research was conducted according to protocols approved by the institutional review board of Fundación Huésped, Argentina.

Serum, plasma and PBMCs were fractioned from blood samples. Levels (normalized optical density, NOD) and titers (2-fold bases) of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies were evaluated by ELISA. Viral neutralization assays were performed as described in Supplemental methods. Flow cytometry was performed to determine the frequency of CD4+ and CD8+T-lymphocytes, antibody-secreting cells (ASC), follicular helper T-cells (Tfh) and soluble plasma mediators (CBA assays). Finally, SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell responses were determined by ELISpot assays using viral proteins and peptide pools as stimuli (Supplemental materials).

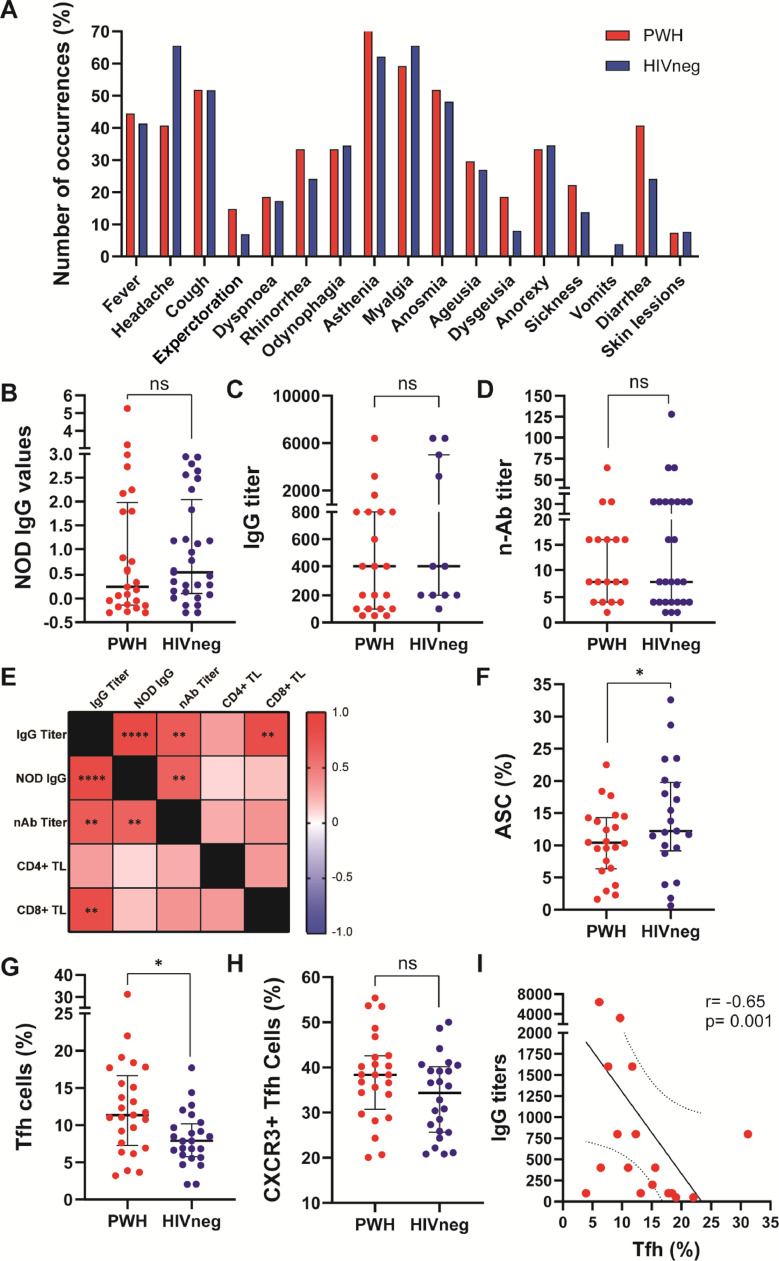

The median age of HIV-negative donors was 41 years (IQR: 35-51.5) and 11/29 (37.9%) were male. In PWH, median age was 44 years (IQR: 34.7-53.5) and 22/29 individuals (75.8%) were male. Median CD4+ T-cell count was 513 cells/µL (IQR: 351-873). All individuals had confirmed COVID-19 infection before enrolment (positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR). In both groups 23/29 individuals showed a mild to moderate COVID-19 presentation, whereas the remaining individuals presented a severe disease. The mean time from symptoms onset to sampling was 69 days (IQR: 31-93) for PWH and 41 days (IQR: 18.5-55) for HIVneg. Both groups displayed similar symptom patterns with no statistical differences (Chi square test, Yates correction; significance level: 0.05; not significant for any symptom analyzed, Fig. 1 A). We observed similar levels of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG, IgG titers and neutralizing antibodies between groups (Fig. 1 B, C and D respectively). Within PWH, neutralization capacity correlated with IgG titers (r:0.70, p<0.001) and NOD values (r:0.65, p<0.001). Additionally, IgG titers were associated with NOD values (r:0.87, p:0.0001) and CD8+TL counts (r:0.82, p<0.001) (Fig. 1E), as was also reported previously by our group in HIVneg donors.3

Figure 1.

Clinical manifestations, anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses, B and T cell phenotype in PWH and HIVneg individuals. (A) Frequency of occurrence of the depicted symptoms in PWH (red) and HIVneg (blue) cohorts. (B) IgG NOD values, (C) IgG titers, and (D) neutralizing Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were determined in plasma from PWH and HIVneg individuals (COVIDAR kit, Laboratorio Lemos S.R.L., Argentina). Normalized optical density (NOD) values were calculated by subtracting the cut-off value to each donor sample OD value, and the resulting value was divided by the mean positive control OD value. Mann-Whitney test was used. p < 0.05 were considered significant. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range. (E) Heatmap depicting from red (+1) to blue (-1) Spearman Rank correlation values between each parameter. p values per correlation are shown in those boxes where statistics were significant. **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. Frequency of (F) antibody-secreting cells (ASC), (G) Tfh, and (H) CXCR3+ Tfh cells in SARS-CoV-2 convalescent PWH (n =25) and HIV-negative (n =24) individuals via traditional gating flow cytometric analysis. Each dot represents an individual donor. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range. (I) Spearman test (two-tailed) showing a negative correlation between IgG titters and frequency of Tfh in PWH.

Regarding relevant lymphocytic populations involved in the immune response against SARS-CoV-2, diminished percentages of circulating ASC were observed among PWH compared to HIVneg (Fig. 1F). Although PWH displayed augmented percentages of Tfh CD4+ cells, the proportion of CXCR3-expressing Tfh subset, a population involved in antibody responses against viral infections and vaccination,8 were similar between groups (Fig. 1G and H). Importantly, we observed a negative correlation between IgG titers and Tfh proportions in PWH (Fig. 1I), therefore highlighting that the dysregulation previously reported of TFh among PWH play an important role in the capacity to exert specific humoral responses against SARS-CoV-2.9

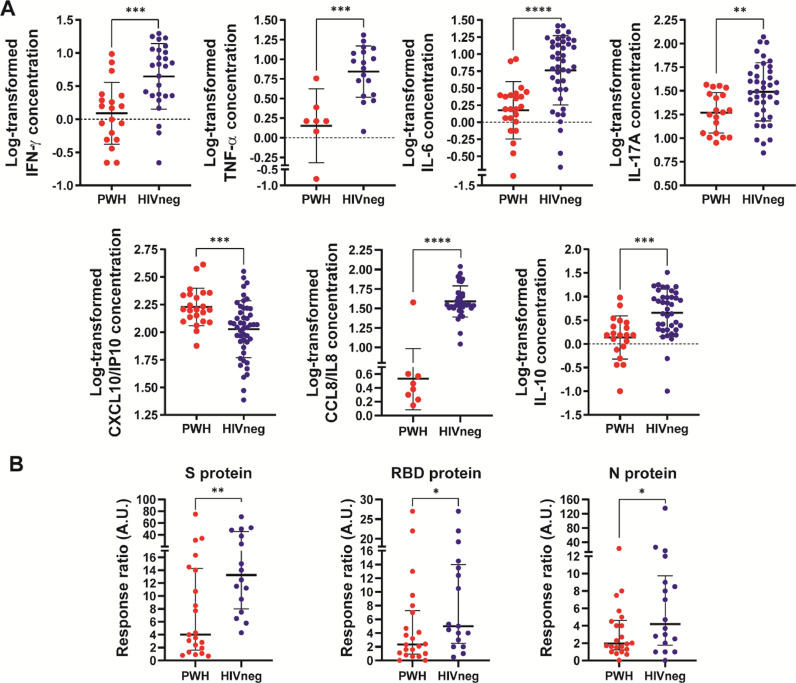

Regarding plasma concentration of cytokines and chemokines, a marked decrease of IL-8/CCL8 and increased IP-10/CXCL10 levels were observed in PWH compared to HIV-neg (Fig. 2 A ). Moreover, significantly diminished levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17A, IL-6 and IL-10 plasma concentrations were noticed in PWH compared to HIVneg (Fig. 2A). Notably, IL-8/CCL8 was not detected in 65.2% of PWH, whereas in HIVneg it was undetectable only in 22.9% of individuals (p = 0,0005, Chi square test, Yates correction).

Figure 2.

Assessment of serum cytokines and chemokines and cellular immunity in PWH and HIVneg donors. (A) The concentrations of CCL8/IL8; CXCL10/IP10; IFN-γ; TNF-α; IL-17A; IL-10 and IL-6 were determined by a multiplex assay and flow cytometry. Data are depicted as the log-transformed concentration values (pg/mL). Each point represents an individual donor. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range. Significance was determined by two-tailed Mann−Whitney U test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. (B) IFN-γ ELISpot assays were performed to determine the frequency of Ag-experienced T cells in peripheral blood from the individuals enrolled. Stimulation of PBMCs with Spike (S) protein, RBD protein or Nucleocapside (N) protein was performed. Afterwards, IFN-γ producing cells were determinined as illustrated in the Supplementary Materials section. In order to compare group differences, data were normalized to media levels. Each dot represents an individual donor. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range. Significance was determined by two-tailed Mann−Whitney U test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. A.U.: arbitrary units.

Advancing on our studies, we determined T-cell responses against SARS-CoV-2 proteins and peptide pools. Our data shows an overall diminished response against SARS-CoV-2 antigens, specifically against Spike, RBD and Nucleocapside whole proteins in PWH (Fig. 2B), with no differences in T-cell responses against Spike or Nucleocapside peptide pools (data not shown). These data show that although PWH presented lower memory T-cell responses against SARS-CoV-2 compared to HIV-negative donors and a dysregulated Tfh population, that is enough to generate a T-B collaboration that allows to elicit a detectable humoral response against the pathogen.

Untreated HIV infection has been proposed as a serious comorbidity for COVID-19, but it is increasingly clear that suppressive ART and conserved CD4+ T-cell levels provide a proper environment for the generation of an effective immunity against SARS-CoV-2, not different to HIV-negative individuals.10 Our data support the landscape of reduced cellular responses and altered plasma cytokines concurrent with effective antibodies responses against SARS-CoV-2 in PWH on-ART, which reinforces the idea of a significant impact of ART not only in HIV control but also in reducing overall morbi-mortality by, for instance, helping to restrict other infections.

Authorship

NL and MFQ conceived and designed experiments; DG, MBV, NL and MFQ analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. DG, MBV, AC, MLP and LC processed samples and performed experiments. SB, BWG, NL and YL recruited donors, collected samples and obtained clinical data. YL performed serological studies. VGP performed and analyzed flow cytometry data. GT, NL and YG contributed reagents/materials and analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors contributed to the refinement of the report and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the BBEI donor subjects for their participation, Dr. Andrea Gamarnik, Dr. Maria M. Gonzalez Lopez Ledesma and Dr. Sandra Gallego for providing materials and Dr. Horacio Salomon for continuous support.

This work was supported by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación (Agencia I+D+i) from Argentina through an extraordinary funding opportunity to improve the national response to COVID-19 (Proyecto COVID N° 11, IP 285).

Footnotes

Biobanco de Enfermedades Infecciosas (BBEI) Colección COVID19 working group: Sabrina AZZOLINA1, 2, Silvia BALINOTTI4, Cinthia CASTRO4, Leonel CRUCES1, 2, Alejandro CZERNIKIER1, 2, Yanina GHIGLIONE1, 2, Denise Anabella GIANNONE1, 2, Virginia GONZALEZ POLO1, 2, Verónica LACAL4, Natalia LAUFER2, 3, Yesica LONGUEIRA1, 2, Marcelo H. LOSSO8, Laura MORENO MACIAS8, Andrea PEÑA MALAVERA7, Claudio PICCARDO1, 2, María Laura POLO1, 2, María Florencia QUIROGA2, 3, Maximiliano MARTINEZ4, Jimena NUÑEZ4, Sebastián NUÑEZ4, Carla PASCUALE1, 2, María REY4, Claudia SALGUEIRA5, Horacio SALOMON2, 3, Melina SALVATORI1, 2, Gabriela SIGNES6, Luciana SPADACCINI5, Melisa TATTA5, César TRIFONE1, 2, Gabriela TURK2, 3, María Belén VECCHIONE1, 2

Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Medicina. Buenos Aires. Argentina. 2CONICET – Universidad de Buenos Aires. Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas en Retrovirus y SIDA (INBIRS). Buenos Aires. Argentina. 3Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Medicina. Departamento de Microbiología, Parasitología e Inmunología. Buenos Aires. Argentina. 4Sanatorio Güemes, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina. 5Sanatorio Anchorena, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina. 6Servicio Penitenciario Federal, Argentina. 7CONICET – Instituto de Tecnología Agroindustrial del Noroeste Argentino, Estación Experimental Agroindustrial Obispo Colombres, Tucumán, Argentina. 8Hospital General de Agudos José María Ramos Mejía, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2022.05.026.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Venturas J., et al. Comparison of outcomes in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with COVID-19. J Infect. 2021;83:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin-Vicente M., et al. Similar humoral immune responses against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in HIV and non-HIV individuals after COVID-19. J Infect. 2022;84:418–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longueira Y., et al. Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies among COVID19 biobank donors in Argentina. Heliyon. 2021;7:e08140. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambrosioni J., et al. Overview of SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults living with HIV. Lancet HIV. 2021;8:e294–e305. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00070-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyman J., et al. Similar antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 in HIV uninfected and infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy during the first South African infection wave. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y., et al. People living with HIV easily lose their immune response to SARS-CoV-2: result from a cohort of COVID-19 cases in Wuhan, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:1029. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06723-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alrubayyi A., et al. Characterization of humoral and SARS-CoV-2 specific T cell responses in people living with HIV. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.02.15.431215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J., et al. Circulating CXCR3(+) Tfh cells positively correlate with neutralizing antibody responses in HCV-infected patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10090. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46533-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindqvist M., et al. Expansion of HIV-specific T follicular helper cells in chronic HIV infection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3271–3280. doi: 10.1172/JCI64314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharov K.S. HIV/SARS-CoV-2 co-infection: T cell profile, cytokine dynamics and role of exhausted lymphocytes. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.