Abstract

Aims: Inflammation is involved in various processes of atherosclerosis development. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, a predictor for cardiovascular risk, are reportedly reduced by statins. However, several studies have demonstrated that CRP is a bystander during atherogenesis. While S100A12 has been focused on as an inflammatory molecule, it remains unclear whether statins affect circulating S100A12 levels. Here, we investigated whether atorvastatin treatment affected S100A12 and which biomarkers were correlated with changes in arterial inflammation.

Methods: We performed a prospective, randomized open-labeled trial on whether atorvastatin affected arterial (carotid and thoracic aorta) inflammation using18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET/CT) and inflammatory markers. Thirty-one statin-naïve patients with carotid atherosclerotic plaques were randomized to either a group receiving dietary management (n=15) or one receiving atorvastatin (10mg/day,n=16) for 12weeks.18F-FDG-PET/CT and flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD) were performed, the latter to evaluate endothelial function.

Results: Atorvastatin, but not the diet-only treatment, significantly reduced LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C, -43%), serum CRP (-37%) and S100A12 levels (-28%) and improved FMD (+38%).18F-FDG-PET/CT demonstrated that atorvastatin, but not the diet-only treatment, significantly reduced accumulation of18F-FDG in the carotid artery and thoracic aorta. A multivariate analysis revealed that reduction in CRP, S100A12, LDL-C, oxidized-LDL, and increase in FMD were significantly associated with reduced arterial inflammation in the thoracic aorta, but not in the carotid artery.

Conclusions: Atorvastatin treatment reduced S100A12/CRP levels, and the changes in these circulating markers mirrored the improvement in arterial inflammation. Our observations suggest that S100A12 may be an emerging therapeutic target for atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Atorvastatin, CRP, S100A12, 18F-FDG-PET/CT, Flow-mediated vasodilatation

Clinical Trial Registration: This study is registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00920101

1. Introduction

Inflammation is believed to play pivotal roles in atherogenesis 1) . Also, it has been found that circulating C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are a good predictor for incidence of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) 2) . A number of clinical trials have shown that CVD events are reduced by treatment with statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors), which reduce not only serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) -cholesterol levels but also CRP levels, suggesting that statins have pleiotropic actions 3) . Greater CRP reduction during statin therapy is reportedly associated with lower incidence of CVD events 4) . However, it remains controversial whether CRP is a good therapeutic target for CVD, because there was no difference in atherosclerosis development among CRP knockout 5) , transgenic 6 , 7) and wild type mice, indicating that CRP is a bystander during atherogenesis.

In contrast, accumulating evidence indicates that S100A12 is an emerging therapeutic target for CVD 8) . S100A12 is mainly secreted from neutrophils into the circulation and reportedly modulates various neutrophil activities by regulating specific calcium-dependent signal transduction pathways via receptor for advanced glycation end product (RAGE) 8) . Regarding the effects of S100A12 on atherogenesis, Hofmann Bowman et al. 9) reported that, using apolipoprotein E (apoE) knockout mice, overexpression of S100A12 accelerated development of atherosclerosis and resulted in enhancing the typical characteristics of vulnerable plaques. Moreover, in this mouse model, inhibition of S100A12 by a small molecule compound, which had been previously known to inhibit inflammation, reportedly attenuated atherogenesis 10) . In the clinical setting, recent studies have shed light on relationships between CVD and serum levels of S100A12. Namely, higher levels of serum S100A12 are reportedly associated with a poor prognosis 11) and higher incidence 12) of CVD. Consistent with the above basic observations, another study found that serum S100A12 levels were increased in patients with acute coronary syndrome and lesion complexity observed angiographically 13) , demonstrating that circulating levels of S100A12 may be a marker for plaque vulnerability in humans. Collectively, based on the hypothesis that leukocytes significantly contribute to atherogenesis, S100A12 would be a more promising therapeutic target in CVD than CRP, a secretory protein released from the liver.

Positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) has been established as a useful modality for evaluating atherosclerotic plaques and visualizing inflammation of the arterial wall. Abbas et al. 14) recently reported that increased levels of circulating S100A12 were associated with carotid plaque inflammation evaluated by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET (18F-FDG-PET)/CT. While other recent studies have demonstrated that statins attenuate plaque inflammation detected by PET/CT, it remains unclear whether they affect circulating human S100A12 levels, and, if so, whether the changes in S100A12 due to statins correlate with changes in atherosclerotic plaque inflammation.

We performed a randomized control trial as a pilot study to evaluate effects of atorvastatin on plaque inflammation using 18F-FDG-PET/CT imaging together with circulating levels of S100A12 and other inflammatory/oxidative stress markers and endothelial function measurements in patients with carotid atherosclerosis.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

This study was a prospective, randomized, open-labeled study to investigate the effects of atorvastatin on plaque inflammation in the aortic/carotid arteries using 18F-FDG-PET/CT, circulating S100A12 levels and other serum markers, and endothelial function as evaluated by flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD) in the brachial artery. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the National Defense Medical College, and conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent prior to starting any study procedures.

This study consisted of a 4-week pre-study observation period with diet and exercise therapy, followed by a 12-week treatment period. It was conducted as a pilot study and therefore, the sample size (n=30) was determined according to the previously published method 15) .

Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 20 and <80 years and carotid artery with atherosclerotic plaque (focal intimal protrusion above 1.4 mm) detected by ultrasonography. Exclusion criteria included: 1) taking any statin or fibrate at study entry, 2) poorly-controlled hypertension, 3) poorly-controlled diabetes (Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 8.5 %), 4) history of stroke, acute coronary syndrome or any cardiovascular diseases requiring inpatient treatment within 6 months, 5) end stage renal disease, 6) hepatic dysfunction (either level of aspartate aminotransaminase or alanine aminotransferase exceeding 3 times normal limits), 7) malignancies or inflammatory diseases.

Each subject individually participated in a program of nutritional counseling according to Executive Summary of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society Guidelines 16) from the 4-week run-in period throughout the study. After the observation period, 31 eligible patients (mean age 62±12 years) were randomized to a diet (control) group or an atorvastatin 10 mg daily plus diet group. Measurement of FMD/nitroglycerin (NTG)-mediated vasodilatation (NMD), blood/urine sampling, and PET/CT were performed at baseline and 12 weeks after randomization. Other medications, such as anti-diabetic and anti-hypertensive agents, were maintained throughout the study for both groups.

2.2. Blood Sampling and Biochemical Analysis

Venous blood samples for measurement of biochemical parameters were obtained in the morning after an overnight fast. Serum total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-C, glucose and creatinine levels were determined by standard enzymatic methods. LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were calculated using the Friedewald formula. HbA1c was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography. Serum malondialdehyde-modified LDL (MDA-LDL) levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) 17) . Serum high sensitivity CRP levels were measured using a BNII nephelometer (Dade Behring, Germany). Serum levels of S100A12 (Circulex TM, Nagano, Japan) and pentraxin 3 (Perseus Proteomics, Tokyo, Japan) were determined using ELISA kits. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) levels were also determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The vacutainers were immediately transferred on ice after sampling, centrifuged, isolated and stored at −70℃ until further analyses.

2.3. 18F-FDG-PET/CT Imaging

PET/CT imaging using Biograph Duo (Siemens CTI) was performed according to the methods published in a previous paper 18) . Biograph Duo allows simultaneous collection of 64 slices over a span of 15.8 cm with a slice thickness of 2.5 mm and a transaxial resolution of 6.3 mm. After at least a 6 hr fast, the study subjects were intravenously injected with 18F-FDG (3.7Mbq/kg). Two hr after injection, a transmission scan using CT for attenuation correction and anatomical imaging was acquired for 90 sec, and a static emission scan was acquired for 15 min. There were no subjects with blood glucose levels above 200 mg/dl. All data were reconstructed with OSEM image.

For the semiquantitative assessment of FDG uptake, regions of interest (ROIs) were placed in the carotid artery and thoracic aorta, which included the highest uptake area (circle ROI, 1 cm in diameter), and the Standardized Uptake Value (SUVmax) was calculated. Regarding the repeat PET/CT imaging, special attention was paid to matching the images to those at baseline. Slices most closely matching those obtained at baseline were selected using several anatomic landmarks (i.e., vertebrae, intercostal arteries, pulmonary arteries and veins). The matching procedure was carried out by 2 observers. All patient information was removed from images and analyzed in a blinded fashion by radiologists of the National Defense Medical College Hospital and Tokorozawa PET Imaging and Diagnostic Clinic.

2.4. Assessment of Endothelial Function

Endothelial function was assessed by FMD of the brachial artery at baseline and 12 weeks after randomization. After measurement of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, FMD was measured noninvasively using a high-resolution ultrasound apparatus with a 7.5-MHz linear array transducer (Aplio SSA-770A, Toshiba Co Ltd) according to the guidelines of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force 19) . All measurements were performed in the morning from 9 to 11 am before taking any drugs, in a temperature-controlled room (25℃) with the subject in a fasting, resting, and supine state. Electrocardiograms were monitored continuously. The subject’s dominant arm (right) was immobilized comfortably in the extended position to allow consistent access to the brachial artery for imaging. The vasodilatation responses of the brachial artery were observed using a previously validated technique 20) . For each subject, optimal brachial artery images were obtained between 2 and 10 cm above the antecubital fossa. First, baseline two-dimensional (2-D) images were obtained and after measurement of the baseline artery diameter, a narrow-width blood pressure cuff was inflated on the most proximal part of the forearm to an occlusive pressure (200 mmHg) for 5 min to induce hyperemia. The position of the ultrasound transducer was carefully maintained throughout the procedure. The cuff was then deflated rapidly and 2-D images of the artery were obtained for 30-120 sec after deflation. Using the same method, we measured endothelium-independent vasodilatation due to administration of NTG (0.3 mg). Nitroglycerin-mediated vasodilation (NMD) was measured before (baseline) and 240-300 sec after NTG administration. Throughout the study, FMD and NMD were examined by cardiologists who were blinded to the treatment regimen of each subject, using the same ultrasound apparatus and probe set for all measurements. Each subject was examined by the same cardiologist throughout the study. All images were recorded as movie files in a hard disk recorder for later analysis. To manually measure vasodilator responses in each patient’s artery, movies were played back and a 10-20 mm segment was identified for analysis using anatomic landmarks. To select images reproducibly for the same point in the cardiac cycle, images at peak systole were identified and the diameter of the artery was digitized using a caliper function of the ultrasound apparatus. For each condition (baseline, FMD, baseline before NMD, and after NMD), 3 separate images from 3 different cardiac cycles were digitized and their average segment diameters determined. Both FMD and NMD were expressed as percentage change from baseline to peak dilation. The intra- and inter-observer variability (coefficient of covariance) for repeated diameter measurements at baseline and reactive hyperemia or NMD in the brachial artery were both <3% 20) .

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Data were presented as mean with standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range as appropriate. Baseline characteristics were summarized by treatment sequences and compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Differences before and after the treatments were evaluated using the paired t test for parametric variables. For TG and CRP, the t-test was used to compare log-transformed values, which were normally distributed. Multiple linear regression was used to assess the relationship between FDG uptake in arteries and the changes in LDL-C, TG, MDA-LDL, CRP, S100A12 and %FMD. A p value <0.05 denoted a statistically significant difference. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP Version 12.0 software package (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

The baseline characteristics of each group are shown in Table 1 . In both groups, there were no subjects who discontinued participation in the study due to health complaints. There were no differences between the 2 groups in any category including age, body mass index, smoking status, diabetes mellitus (diagnostic criteria according to Japanese Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes 2016 21) ), medications for diabetes/hypertension, lipid levels, and concomitant use of medications.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

| Control (n = 15) | Atorvastatin (n = 16) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male | 12 | 12 | 1.00 |

| Age, years | 60.1±14.8 | 62.9±8.3 | 0.84 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.4±2.4 | 23.4±2.3 | 0.76 |

| Smoking, n | 3 | 3 | 0.60 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n | 4 | 4 | 1.00 |

| Hypertension, n | 7 | 5 | 0.46 |

| Coronary artery diseases, n | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| TC, mg/dl | 239±34.7 | 226±32.6 | 0.21 |

| LDL-C, mg/dl | 147±28.5 | 132±32.0 | 0.25 |

| TG, mg/dl | 121 [104, 192] | 117 [89, 147] | 0.71 |

| HDL-C, mg/dl | 62.0±22.0 | 63.1±25.9 | 1.00 |

| Medication, n | |||

| Anti-hypertensives | 7 | 5 | 0.47 |

| Anti-platelet agents | 4 | 4 | 1.00 |

| Anti-diabetic agents | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; TC, total cholesterol, LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Values are mean±SD except for TG (median [interquartile ranges]).

p values are for Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables.

3.2. Atorvastatin Reduced Serum CRP and S100A12 Levels as well as Lipids, and Enhanced FMD

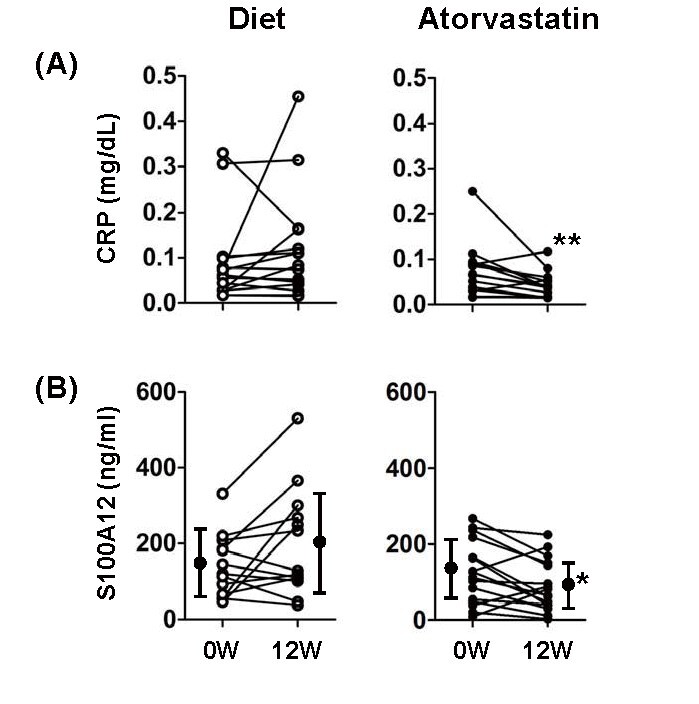

As shown in Table 2 , atorvastatin treatment, as expected, significantly reduced LDL-C levels as well as TG and MDA-LDL levels. It significantly reduced serum CRP levels as previously reported 3) , and also S100A12 levels ( Fig.1 ) . We also measured circulating levels of S100A8/9 and other S100 protein family members, revealing that atorvastatin did not affect them. Serum levels of inflammatory markers, such as TNF-α, MCP-1 and pentraxin 3, were unaffected by atorvastatin. As also expected, atorvastatin treatment, increased FMD; however, NMD was not affected.

Table 2. Anthropometric/biochemical parameters, endothelial function and 18F-FDG uptake in arteries before and after treatments.

| Control (n = 15) | Atorvastatin (n = 16) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 week | 12 weeks | p valuea | 0 week | 12 weeks | p valuea | |

| Body weight, kg | 63.9±7.0 | 63.5±7.9 | 0.356 | 61.5±6.9 | 61.7±6.4 | 0.358 |

| SBP, mmHg | 134±14 | 132±19 | 0.723 | 132±19 | 125±17 | 0.221 |

| DBP, mmHg | 78.1±12.7 | 75.1±7.6 | 0.235 | 78.3±14.9 | 70.7±13.5 | 0.054 |

| Biochemical parameters | ||||||

| TC, mg/dl | 229±35 | 217±34 | 0.051 | 222±42 | 161±25 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dl | 132±44 | 133±30 | 0.918 | 137±42 | 78.6±21.2 | <0.001 |

| TG, mg/dl | 106 [81, 147] | 95 [74, 118] | 0.074 | 117 [80, 177] | 95 [74, 118] | 0.030 |

| HDL-C, mg/dl | 59.6±21.3 | 60.5±20.9 | 0.608 | 57.6±18.5 | 61.2±20.1 | 0.077 |

| MDA-LDL, U/l | 153±61 | 140±55 | 0.606 | 166±62 | 106±27 | 0.002 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 106±23 | 104±18 | 0.531 | 112±36 | 112±31 | 0.960 |

| HbA1C, % | 5.73±0.82 | 5.91±0.82 | 0.200 | 6.30±1.22 | 6.43±1.29 | 0.359 |

| CRP, mg/l | 0.61 [0.28, 0.89] | 0.84 [0.44, 1.42] | 0.184 | 0.59 [0.27, 0.90] | 0.37 [0.16, 0.52] | 0.004 |

| S100A8, ng/ml | 34.0±8.9 | 42.0±17.91 | 0.099 | 30.2±11.8 | 27.5±9.5 | 0.378 |

| S100A9, ng/ml | 22.7±12.6 | 35.2±27.3 | 0.377 | 19.8±18.6 | 15.5±11.9 | 0.054 |

| S100A12, ng/ml | 140±82 | 20±141 | 0.071 | 125±83 | 89.5±67.0 | 0.030 |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | 17.3±10.3 | 13.7±9.5 | 0.316 | 23.0±10.0 | 19.5±11.5 | 0.280 |

| MCP-1, pg/ml | 240±79 | 241±97 | 0.494 | 187±56 | 180±64 | 0.920 |

| Pentraxin3, pg/ml | 35.6±22.4 | 43.0±40.0 | 0.201 | 35.6±25.9 | 25.9±12.8 | 0.407 |

| Endothelial function | ||||||

| FMD, % | 6.14±4.35 | 6.51±2.68 | 0.758 | 6.00±2.27 | 8.27±4.32 | 0.039 |

| NMD, % | 21.9±9.1 | 19.9±6.3 | 0.564 | 20.7±10.2 | 20.2±8.7 | 0.887 |

| 18F-FDG uptake in arteries | ||||||

| Carotid artery | 1.99±0.24 | 1.85±0.30 | 0.100 | 1.94±0.40 | 1.77±0.40 | 0.039 |

| Thoracic aorta | 2.01±0.27 | 1.90±0.25 | 0.107 | 2.07±0.30 | 1.90±0.26 | 0.044 |

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; apo, apolipoprotein; MDA-LDL, malondialdehyde-modified LDL; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; CRP, C-reactive protein; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; FMD, flow-mediated dilatation; NMD, nitroglycerin-mediated dilatation. For quantitative analysis in 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging, the maximum standardized uptake values (SUVs) were evaluated in individual plaques and averaged for analysis of the results of the subject-wise SUV at baseline and after 3-month treatment.

Values are mean±SD except for TG and CRP (median [interquartile ranges]). a The values of TG/CRP were analyzed after logarithmic transformation.

Fig.1. Effects of atorvastatin on serum CRP (A) and S100A12 (B) levels.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01

3.3. Atorvastatin Attenuated Arterial Plaque Inflammation Detected by PET/CT

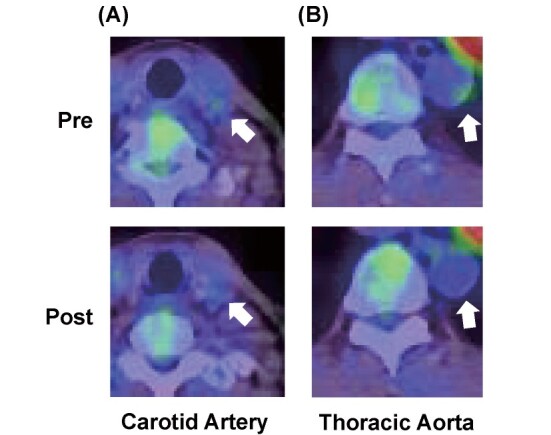

18F-FDG-PET/CT imaging revealed that FDG uptake levels in the carotid artery and thoracic aorta were significantly decreased in the atorvastatin group, but not in the control group ( Fig. 2 and Table 2 ) .

Fig.2. Representative PET/CT Images.

The arrows indicate reduced accumulation of 18F-FDG in carotid artery (A) and thoracic aorta (B) after atorvastatin treatment.

3.4. Atorvastatin-Mediated Changes in Circulating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Markers and Endothelial Function were Associated with Attenuated Plaque Inflammation

To further investigate which factors contributed to attenuation of arterial inflammation by atorvastatin, we performed multivariate analysis ( Table 3 ) using parameters significantly affected by atorvastatin treatment (LDL-C, log TG, MDA-LDL, log CRP, S100A12 and FMD). Interestingly, although there was no significant factor for the carotid artery, the changes in log CRP, S100A12, MDA-LDL levels, and FMD were factors significantly correlated with changes in FDG uptake in the thoracic aorta.

Table 3. Relationships between changes in FDG uptake in arteries and biochemical parameters and FMD after treatment with atorvastatin by multiple linear regression analysis.

| Changes in FDG-PET uptake in arteries | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimates | Standard error | p value | |

| Carotid artery | |||

| LDL-C | -0.001 | 0.007 | 0.605 |

| log TG | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.896 |

| MDA-LDL | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.225 |

| log CRP | -0.468 | 0.463 | 0.343 |

| S100A12 | -0.005 | 0.003 | 0.090 |

| %FMD | 0.007 | 0.023 | 0.940 |

| Thoracic aorta | |||

| LDL-C | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.055 |

| log TG | -0.408 | 0.968 | 0.351 |

| MDA-LDL | -0.005 | 0.001 | 0.011 |

| log CRP | 1.562 | 0.240 | 0.001 |

| S100A12 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.020 |

| %FMD | 0.033 | 0.001 | 0.045 |

Multiple linear regression analysis was performed for carotid artery and thoracic aorta, respectively. Abbreviations: LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; MDA, malondialdehyde; CRP, C-reactive protein; FMD, flow-mediated dilatation.

4. Discussion

The present study showed that, for the first time, atorvastatin treatment reduced circulating levels of an emerging inflammatory marker, S100A12, in addition to those of CRP, and the reduction in these factors was significantly associated with attenuated arterial inflammation during statin treatment.

Accumulating evidence from several clinical trials shows that various statins reduce serum CRP levels 22) . Further, the clinical importance of inflammation was demonstrated in the JUPITER trial 4) . In it, cumulative cardiovascular event rates increased as a function of both LDL-C and CRP levels with greater event rates in the subjects with on-treatment high CRP levels as compared to their low CRP counterparts. Although CRP is a clinically useful biomarker for CVD risk prediction, several mechanistic studies have suggested that CRP itself is not a good therapeutic target for CVD and therefore, an innovative clinical trial targeting an upstream inflammatory molecule, interleukin-1β, was performed 23) . It revealed that administration of a monoclonal antibody against IL-1β resulted in reductions not only in circulating CRP levels, but also recurrent cardiovascular events, indicating that anti-inflammatory therapies are a promising strategy against CVD.

S100A12 is an emerging therapeutic target for CVD 8) . S100A8/9/12 share structural and functional homologies, S100A8/9 constitute 40% of the cytosolic protein in neutrophils, and S100A12 constitutes 5% 24) . They interact with various target molecules involved in inflammation, calcium homeostasis, cellular differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and cytoskeleton regulation. S100A12 reportedly binds to RAGE, which, in turn, activates the downstream transcription factor NFκB, resulting in an enhanced inflammatory response 25) . Circulating S100A12 levels have been reported to be associated with the status and activity of various inflammatory diseases, such as infectious diseases 26) , rheumatoid arthritis 27 , 28) , and inflammatory bowel diseases 29) . Although there was scarce evidence that medical interventions affect circulating S100A12 levels, treatments did reduce S100A12 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis 27 , 28) . Regarding atherosclerotic diseases, a series of animal studies 9 , 10) have produced interesting observations. While S100A8/9 are present in mice, S100A12 is known to be lacking. Therefore, Hofmann Bowman et al. 9) generated S100A12 transgenic mice with an apoE null background, in which there was greater development of atherosclerosis as compared to the control. Furthermore, treatment with an S100A12 inhibitor, ABR-215757, attenuated atherosclerosis development in these mice, and more importantly, larger necrotic core size and other typical pathological features of vulnerable plaques were less prominent due to treatment with this compound. Also, strikingly, in wild type mice with an apoE null background, these effects of ABR-215757 were not observed, indicating that S100A12 contributes to atherogenesis. Taken together with the findings from several cross-sectional clinical studies 11 - 13) described in Introduction, this indicates that S100A12 is a promising target for the prevention and treatment of CVD.

The present study demonstrated that lipid-lowering therapy using atorvastatin reduced serum S100A12 levels in patients with carotid atherosclerosis ( Table 2 ) . Statins are believed to also exert pleiotropic lipid-lowering–independent effects, including anti-inflammatory effects, which are regulated by various distinct mechanisms via HMG-CoA reductase-dependent/independent pathways 30) . Although the precise regulatory mechanism of S100A12 expression remains unclear, several feasible mechanisms were recently reported 31 , 32) . Based on the findings of these studies, S100A12 expression was transcriptionally up-regulated by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β and activator protein. Since statins reportedly promote expression of other genes by activating these transcription factors 33 , 34) , further studies are needed to explore underlying mechanisms for atorvastatin-mediated reduction of serum S100A12 levels.

Similar to CRP, previous studies observed that serum S100A12 levels were not normally distributed in patients with cardiovascular 11 , 12) and inflammatory 28) diseases. In contrast, in the present study, S100A12 levels were normally distributed. We also confirmed the normal distribution of S100A12 levels through measurement in blood samples obtained from the healthy subjects (unpublished data). Therefore, distribution of circulating S100A12 levels depends on patient (or subject) backgrounds. Further studies are needed to assess whether statin treatment reduces circulating S100A12 levels in such high-risk patients.

Recent studies have noted that treatment using statins not only reduced circulating inflammatory markers, such as CRP, but also attenuated plaque inflammation detected by 18F-FDG-PET/CT 35) . Ishii et al. 36) reported that reduced accumulation of 18F-FDG in the ascending aorta and femoral artery after treatment with atorvastatin was significantly associated with reduced circulating levels of LDL-C, MDA-LDL, and CRP. Consistent with the findings of these previous studies, we also found that atorvastatin treatment significantly attenuated arterial inflammation evaluated by 18F-FDG-PET/CT ( Table 2 ) . Multivariate analysis revealed that reduced levels of S100A12, CRP and MDA-LDL and increased FMD were associated with attenuated plaque inflammation in the thoracic aorta, but not in the carotid artery ( Table 3 ) , implying that S100A12 may play an important role in particular sites of arterial inflammation. Although reasons for this discrepancy in associations remain unclear, the distinct anatomical location of arteries might account for it. In this regard, we previously reported that rosuvastatin therapy yielded a significant reduction in CRP levels, which was correlated with plaque regression in the thoracic aorta, but not in the abdominal aorta, detected by magnetic resonance imaging 37) , suggesting that factors contributing to statin-mediated beneficial changes may differ among arteries.

We also observed that atorvastatin treatment improved endothelial function evaluated by FMD ( Table 2 ) , a finding consistent with previous studies 38) . Molecular mechanisms by which statins restore endothelial dysfunction have been reported to be direct and indirect pathways involved in endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) 39) . Statins reportedly enhance eNOS expression by activating its transcription and stabilizing mRNA, and also attenuate eNOS uncoupling by reducing circulating asymmetrical dimethylarginine. Inhibition of inflammation also indirectly contributes to the statin-mediated beneficial effect on endothelial function. Conversely, endothelial function would also be expected to influence vascular inflammation based on endothelial exocytosis. Statins reportedly inhibit endothelial exocytosis via N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor by increasing NO production, which, in turn, attenuates a release into the circulation of numerous pro-inflammatory molecules, such as von Willebrand factor and P-selectin, leading to reduced endothelial inflammation. Such mechanisms might have contributed to the association between attenuated arterial inflammation and enhanced FMD due to atorvastatin in the present study ( Table 3 ) .

4.1. Study Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, the sample size of our study was small. Although it would have been ideal to use a larger sample size, we had to limit the numbers of subjects, because 18F-FDG-PET/CT is an expensive examination. Second, the statin dose was lower than that in other countries. In Japanese patients with hypercholesterolemia, 10 mg of atorvastatin was adequate for achieving LDL-C reduction of up to 40%, which is comparable to the reduction achieved by 20-40 mg atorvastatin in the patients in Western countries. We therefore used 10 mg, the most frequently prescribed dose in Japan. Finally, we conducted this research as an open label study with patients and their attending physicians aware of the atorvastatin doses in the titration protocol, creating a potential bias.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, atorvastatin treatment reduced S100A12/CRP levels, implying that statins inhibit inflammation systemically and partially in arterial plaques. The present study therefore suggests that the novel inflammatory marker S100A12 contributes to the arterial inflammation attenuated by statins, and may be a potential therapeutic target for atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgements and Notice of Grant Support

None.

Conflict of Interest

There is no relationship with industry that we should disclose.

References

- 1).Libby P and Hansson GK: Inflammation and immunity in diseases of the arterial tree: players and layers. Circ Res, 2015; 116: 307-311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Verma S, Szmitko PE and Ridker PM: C-reactive protein comes of age. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med, 2005; 2: 29-36; quiz 58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Koenig W: High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and atherosclerotic disease: from improved risk prediction to risk-guided therapy. Int J Cardiol, 2013; 168: 5126-5134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr., Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, Macfadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT and Glynn RJ: Reduction in C-reactive protein and LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular event rates after initiation of rosuvastatin: a prospective study of the JUPITER trial. Lancet, 2009; 373: 1175-1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Teupser D, Weber O, Rao TN, Sass K, Thiery J and Fehling HJ: No reduction of atherosclerosis in C-reactive protein (CRP)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem, 2011; 286: 6272-6279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Hirschfield GM, Gallimore JR, Kahan MC, Hutchinson WL, Sabin CA, Benson GM, Dhillon AP, Tennent GA and Pepys MB: Transgenic human C-reactive protein is not proatherogenic in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005; 102: 8309-8314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Reifenberg K, Lehr HA, Baskal D, Wiese E, Schaefer SC, Black S, Samols D, Torzewski M, Lackner KJ, Husmann M, Blettner M and Bhakdi S: Role of C-reactive protein in atherogenesis: can the apolipoprotein E knockout mouse provide the answer? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2005; 25: 1641-1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Oesterle A and Bowman MA: S100A12 and the S100/Calgranulins: Emerging Biomarkers for Atherosclerosis and Possibly Therapeutic Targets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2015; 35: 2496-2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Hofmann Bowman MA, Gawdzik J, Bukhari U, Husain AN, Toth PT, Kim G, Earley J and McNally EM: S100A12 in vascular smooth muscle accelerates vascular calcification in apolipoprotein E-null mice by activating an osteogenic gene regulatory program. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2011; 31: 337-344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Yan L, Bjork P, Butuc R, Gawdzik J, Earley J, Kim G and Hofmann Bowman MA: Beneficial effects of quinoline-3-carboxamide (ABR-215757) on atherosclerotic plaque morphology in S100A12 transgenic ApoE null mice. Atherosclerosis, 2013; 228: 69-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Saito T, Hojo Y, Ogoyama Y, Hirose M, Ikemoto T, Katsuki T, Shimada K and Kario K: S100A12 as a marker to predict cardiovascular events in patients with chronic coronary artery disease. Circ J, 2012; 76: 2647-2652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Grauen Larsen H, Yndigegn T, Marinkovic G, Grufman H, Mares R, Nilsson J, Goncalves I and Schiopu A: The soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products (sRAGE) has a dual phase-dependent association with residual cardiovascular risk after an acute coronary event. Atherosclerosis, 2019; 287: 16-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Liu J, Ren YG, Zhang LH, Tong YW and Kang L: Serum S100A12 concentrations are correlated with angiographic coronary lesion complexity in patients with coronary artery disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest, 2014; 74: 149-154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Abbas A, Aukrust P, Dahl TB, Bjerkeli V, Sagen EB, Michelsen A, Russell D, Krohg-Sorensen K, Holm S, Skjelland M and Halvorsen B: High levels of S100A12 are associated with recent plaque symptomatology in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. Stroke, 2012; 43: 1347-1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Whitehead AL, Julious SA, Cooper CL and Campbell MJ: Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat Methods Med Res, 2016; 25: 1057-1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, Birou S, Daida H, Dohi S, Egusa G, Hiro T, Hirobe K, Iida M, Kihara S, Kinoshita M, Maruyama C, Ohta T, Okamura T, Yamashita S, Yokode M and Yokote K: Treatment A) lifestyle modification: executive summary of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guidelines for the diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in Japan--2012 version. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2013; 20: 835-849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Kotani K, Maekawa M, Kanno T, Kondo A, Toda N and Manabe M: Distribution of immunoreactive malondialdehyde-modified low-density lipoprotein in human serum. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1994; 1215: 121-125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Tahara N, Kai H, Ishibashi M, Nakaura H, Kaida H, Baba K, Hayabuchi N and Imaizumi T: Simvastatin attenuates plaque inflammation: evaluation by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2006; 48: 1825-1831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, Celermajer D, Charbonneau F, Creager MA, Deanfield J, Drexler H, Gerhard-Herman M, Herrington D, Vallance P, Vita J and Vogel R: Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2002; 39: 257-265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Takiguchi S, Ayaori M, Uto-Kondo H, Iizuka M, Sasaki M, Komatsu T, Takase B, Adachi T, Ohsuzu F and Ikewaki K: Olmesartan improves endothelial function in hypertensive patients: link with extracellular superoxide dismutase. Hypertens Res, 2011; 34: 686-692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Haneda M, Noda M, Origasa H, Noto H, Yabe D, Fujita Y, Goto A, Kondo T and Araki E: Japanese Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes 2016. Diabetol Int, 2018; 9: 1-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Arevalo-Lorido JC: Clinical relevance for lowering C-reactive protein with statins. Ann Med, 2016; 48: 516-524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Ridker PM: From C-Reactive Protein to Interleukin-6 to Interleukin-1: Moving Upstream To Identify Novel Targets for Atheroprotection. Circ Res, 2016; 118: 145-156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Averill MM, Kerkhoff C and Bornfeldt KE: S100A8 and S100A9 in cardiovascular biology and disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2012; 32: 223-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Hofmann MA, Drury S, Fu C, Qu W, Taguchi A, Lu Y, Avila C, Kambham N, Bierhaus A, Nawroth P, Neurath MF, Slattery T, Beach D, McClary J, Nagashima M, Morser J, Stern D and Schmidt AM: RAGE mediates a novel proinflammatory axis: a central cell surface receptor for S100/calgranulin polypeptides. Cell, 1999; 97: 889-901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Zackular JP, Chazin WJ and Skaar EP: Nutritional Immunity: S100 Proteins at the Host-Pathogen Interface. J Biol Chem, 2015; 290: 18991-18998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Wittkowski H, Foell D, af Klint E, De Rycke L, De Keyser F, Frosch M, Ulfgren AK and Roth J: Effects of intra-articular corticosteroids and anti-TNF therapy on neutrophil activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis, 2007; 66: 1020-1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Nordal HH, Brun JG, Halse AK, Jonsson R, Fagerhol MK and Hammer HB: The neutrophil protein S100A12 is associated with a comprehensive ultrasonographic synovitis score in a longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2014; 15: 335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Brinar M, Cleynen I, Coopmans T, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P and Vermeire S: Serum S100A12 as a new marker for inflammatory bowel disease and its relationship with disease activity. Gut, 2010; 59: 1728-1729; author reply 1729-1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Jain MK and Ridker PM: Anti-inflammatory effects of statins: clinical evidence and basic mechanisms. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2005; 4: 977-987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Chen H, Cheng L, Yang S, Liu X, Liu Y, Tang J, Li X, He Q and Zhao S: Molecular characterization, induced expression, and transcriptional regulation of porcine S100A12 gene. Mol Immunol, 2010; 47: 1601-1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Li X, Tang J, Xu J, Zhu M, Cao J, Liu Y, Yu M and Zhao S: The inflammation-related gene S100A12 is positively regulated by C/EBPbeta and AP-1 in pigs. Int J Mol Sci, 2014; 15: 13802-13816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Matsumoto M, Einhaus D, Gold ES and Aderem A: Simvastatin augments lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory responses in macrophages by differential regulation of the c-Fos and c-Jun transcription factors. J Immunol, 2004; 172: 7377-7384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Mouawad CA, Mrad MF, Al-Hariri M, Soussi H, Hamade E, Alam J and Habib A: Role of nitric oxide and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein transcription factor in statin-dependent induction of heme oxygenase-1 in mouse macrophages. PLoS One, 2013; 8: e64092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Pirro M, Simental-Mendia LE, Bianconi V, Watts GF, Banach M and Sahebkar A: Effect of Statin Therapy on Arterial Wall Inflammation Based on 18F-FDG PET/CT: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventional Studies. J Clin Med, 2019; 8: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Ishii H, Nishio M, Takahashi H, Aoyama T, Tanaka M, Toriyama T, Tamaki T, Yoshikawa D, Hayashi M, Amano T, Matsubara T and Murohara T: Comparison of atorvastatin 5 and 20 mg/d for reducing F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in atherosclerotic plaques on positron emission tomography/computed tomography: a randomized, investigator-blinded, open-label, 6-month study in Japanese adults scheduled for percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Ther, 2010; 32: 2337-2347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Yogo M, Sasaki M, Ayaori M, Kihara T, Sato H, Takiguchi S, Uto-Kondo H, Yakushiji E, Nakaya K, Komatsu T, Momiyama Y, Nagata M, Mochio S, Iguchi Y and Ikewaki K: Intensive lipid lowering therapy with titrated rosuvastatin yields greater atherosclerotic aortic plaque regression: Serial magnetic resonance imaging observations from RAPID study. Atherosclerosis, 2014; 232: 31-39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Masoura C, Pitsavos C, Aznaouridis K, Skoumas I, Vlachopoulos C and Stefanadis C: Arterial endothelial function and wall thickness in familial hypercholesterolemia and familial combined hyperlipidemia and the effect of statins. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis, 2011; 214: 129-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Antonopoulos AS, Margaritis M, Shirodaria C and Antoniades C: Translating the effects of statins: from redox regulation to suppression of vascular wall inflammation. Thromb Haemost, 2012; 108: 840-848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]