Abstract

Since 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection resulting in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has afflicted hundreds of millions of people in a worldwide pandemic. Several safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines are now available. However, the rapid emergence of variants and risk of viral escape from vaccine-induced immunity emphasize the need to develop broadly protective vaccines. A recombinant plant-derived virus-like particle vaccine for the ancestral COVID-19 (CoVLP) recently authorized by Canadian Health Authorities and a modified CoVLP.B1351 targeting the B.1.351 variant (both formulated with the adjuvant AS03) were assessed in homologous and heterologous prime-boost regimen in mice. Both strategies induced strong and broadly cross-reactive neutralizing antibody (NAb) responses against several Variants of Concern (VOCs), including B.1.351/Beta, B.1.1.7/Alpha, P.1/Gamma, B.1.617.2/Delta and B.1.1.529/Omicron strains. The neutralizing antibody (NAb) response was robust with both primary vaccination strategies and tended to be higher for almost all VOCs following the heterologous prime-boost regimen.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 vaccine, Virus-like particle, AS03, Heterologous regimen, Variant of concerns, Cross-neutralization

Abbreviations: ACC, Animal Care Committee; ACE2, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme; CoVLP, Coronavirus-Like Particle; CI, Confidence Interval; CT, Cytoplasmic Tail; GMT, Geometric Mean; IM, Intramuscular/Intramuscularly; MRD, Minimum Required Dilution; NAb, Neutralizing Antibody; PBS, Phosphate Buffered Saline; PNA, Pseudovirus Neutralizing Assay; RBD, Receptor Binding Domain; S, Spike; TM, Transmembrane Domain; VOC, Variant of Concern; WHO, World Health Organisation

1. Introduction

Since the declaration of a pandemic situation caused by the SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organisation (WHO), over 410 million cases have been reported and >5.8 million people have died from COVID-19 (WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, https://covid19.who.int/, 2021). The rapid development and approval of vaccines with efficacy up to 95% led to hope in mid-2021 that the worst of the pandemic was over [1], [2], [3], [4]. However, the total number of COVID-19 cases is still growing rapidly worldwide with almost 300 000 reported deaths in just the last month, mostly attributable to highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern (VOCs). The most worrisome variants are those with mutations in the Spike (S) protein that not only enhance transmissibility but also increase virulence and evasion of vaccine-induced immunity [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10] or resistance to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies [8], [9], [11]. The S protein plays a crucial role in SARS-CoV-2 infection through the interaction of its receptor binding domain (RBD) with the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor on host respiratory epithelial cells [12], [13], [14]. All of the currently approved vaccines target the S protein of the ancestral strain of SARS-CoV-2 identified in Wuhan and a growing number of reports demonstrate that their efficacy against mainly the B.1.351 and the B.1.617.2 variants is reduced [15], [16], [17], [18]. Medicago has developed a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine using a platform technology based on transient expression of recombinant proteins in non-transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana plants and a disarmed Agrobacterium tumefaciens as a transfer vector to move targeted DNA constructs into the plant cells [19]. The S protein trimers displayed on the surface of the plant-derived coronavirus-like particles (CoVLP) are in a stabilized, prefusion conformation that resemble native structures on wild-type SARS-CoV-2 virions. Plant-based VLP vaccines are an emerging production platform that has many potential advantages such as proper eukaryotic protein modification and assembly, low risk of contamination with adventitious agents, scalability, and rapid production speed [20]. Currently, several plant-based VLP vaccine candidates against pathogens such as Hepatitis B virus [21], Rabies virus [22], Influenza virus [23] and Norwalk virus [24] are under clinical development. At the time of writing, only two plant-based VLP vaccine candidates against SARS-CoV-2 have reached the clinical stage; Medicago’s CoVLP has completed its primary vaccine efficacy analyses in Phase 3 (NCT04636697) and has recently been authorized by Canadian Health Authorities [25] and Kentucky Bioprocessing-201 is in Phase 1/2 (NCT04473690). Herein, we present the preclinical evaluation of a CoVLP candidate targeting the B.1.351 variant compared with the original CoVLP targeting the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain, both of which were formulated with AS03, an Adjuvant System containing DL-α-tocopherol and squalene in an oil-in-water emulsion. Both homologous and heterologous primary immunization strategies induced strong neutralizing antibody (NAb) responses with broad cross-reactivity against the B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.351 (Beta), P.1 (Gamma), B.1.617.2 (Delta), and B.1.1.529 (Omicron) VOCs. SARS-CoV-2 variant strains were selected based on the WHO designation for VOCs and degree of global public health concern.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. AS03-Adjuvanted CoVLP vaccine and CoVLP.B1351 vaccine candidate

The full-length S glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 from the GISAID database (https://www.gisaid.org/), strain hCoV-19/USA/CA2/2020 (nucleotides sequence 21,563 to 25,384 from EPI_ISL_406036) corresponding to the ancestral Wuhan strain for CoVLP or hCoV-19/Belgium/AZDelta05413-2105R/2021 (nucleotides sequence 21,521 to 25,342 from EPI_ISL_961189) for CoVLP.B1351 were expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana plants as previously described [19]. The S protein was modified at the S1/S2 cleavage site (CoVLP: R667G, R668S and R670S substitutions; CoVLP.B1351: R682G, R683S and R685S substitutions; relative to native S protein from original B strain from EPI_ISL_406036) to increase stability and to stabilize the protein prefusion conformation (CoVLP: and K971P and V972P substitutions; CoVLP.B1351: K986P and V987P; relative to native S protein from original B strain from EPI_ISL_406036). The signal peptide was replaced with a plant gene signal peptide and the transmembrane domain (TM) and cytoplasmic tail (CT) of S protein were also replaced with TM/CT from Influenza H5 A/Indonesia/5/2005 to increase VLP assembly and budding. The self-assembled VLPs bearing S protein trimers were isolated from the plant matrix and subsequently purified using a process similar to that described for Medicago’s plant-derived influenza VLP vaccine candidates [26].

The AS03 Adjuvant System, an oil-in-water emulsion containing 11.86 mg DL-α-tocopherol, 10.69 mg squalene and 4.86 mg Polysorbate 80 per adult human dose, was supplied by GSK, (Rixensart, Belgium) and was used as recommended by the manufacturer. The control article was phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution with Polysorbate 80. On each dosing day, CoVLP and CoVLP.B1351 were diluted with PBS to achieve the appropriate concentration and then mixed in a 1:1 (volume:volume) ratio with adjuvant prior to administration.

2.2. Animals, immunizations and In-Life/Post-Mortem observations

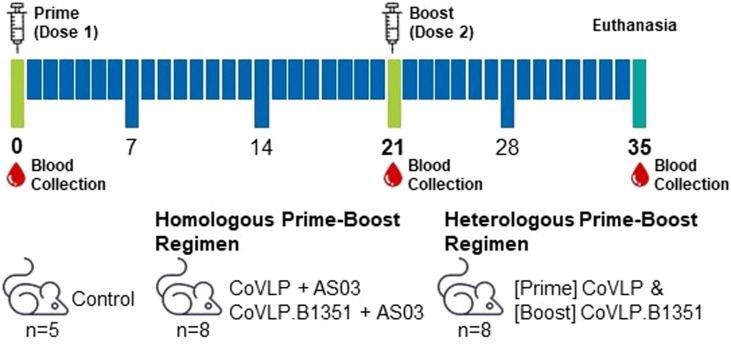

Female specific pathogen free BALB/c mice (8 weeks old) were supplied from Charles River (St-Constant, Québec, Canada) and the study was conducted at ITR Laboratories Canada Inc (Baie d’Urfe, Quebec, Canada). The study protocol was approved by ITR’s internal Animal Care Committee (ACC) and all animals used were cared for in accordance with the principles outlined in the current “Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals” published by the Canadian Council on Animal Care, the NIH’s “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and the Animal Research Reporting In Vivo Experiments guidance. In summary, animals were maintained under standard laboratory conditions (lighting: 12 / 12 h, temperature: 21 ± 3 °C, relative humidity: 50 ± 20%) with certified rodents pellet feed and drinking water ad libitum. The mice (8/group, except for no vaccine control; 5/group) were immunized intramuscularly (IM) with 3.75 µg AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 or the PBS control on Days 0 and 21 (final volume 0.1 mL; 0.05 mL per injection site). The administered dose was calculated based on the total protein content (measured by the BCA method) and adjusted for the purity of the CoVLP content. The purity is based on the relative abundance of the S protein measured by reduced SDS-PAGE and densitometry analyses. The purity of CoVLP and CoVLP.B1351 were 81% and 80% respectively. The AS03-adjuvanted vaccines were administered as either a homologous (CoVLP-CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351-CoVLP.B1351) or heterologous (CoVLP-CoVLP.B1351) prime-boost during primary vaccination (Fig. 1 ). Mortality, clinical signs, body weight, food consumption and injection site observations were evaluated throughout the study. Macroscopic observations were performed at euthanasia on Day 35. Blood was collected on Days 0 (pre-immune), 21 and 35 to measure serum NAb levels.

Fig. 1.

Experimental Design Female BALB/c mice were intramuscularly vaccinated twice (Days 0 and 21) with 0.1 mL of control (PBS), CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 adjuvanted with AS03 (final CoVLP dose of 3.75 µg) as homologous or heterologous prime-boost regimen. n, number of mice within the group. Syringe indicates immunization day. Red drop indicates blood collection day.

2.3. Pseudovirus neutralization assay (PNA)

The PNA was performed by Nexelis (Laval, Quebec, Canada) using a pseudovirus based on SARS-CoV-2 ancestral Wuhan strain (reference MN908947) as previously described [27]. Analyses were performed in duplicate and included appropriate controls. The assay was qualified for the ancestral pseudovirus strain. Cross-reactivity was evaluated using modified pseudovirions expressing SARS-CoV-2 S glycoproteins from representative B.1.351 (L18F, D80A, D215G, del242-244, R246I, K417N, N501Y, E484K, D614G, A701V, plus Δ19aa C-terminal for the PP processing), B.1.1.7 (del69-70, del144, N501Y, A570D, D614G, P681H, T716I, S982A, D1118H, plus Δ19aa C-terminal for the PP processing), P.1 (L18F, T20N, P26S, D138Y, R190S, K417T, E484K, N501Y, D614G, H655Y, T1027I, V1176F, plus Δ19aa C-terminal for the PP processing), B.1.617.2 (T19R, G142D, Del156, Del157, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N) and B.1.1.529 (A67V, Δ69-70, T95I, G142D/Δ143-145, Δ211/L212I, ins214EPE, G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, K417N, N440K, G446S, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493K, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, T547K, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, L981F) strain sequences. In brief, serum samples were heat-inactivated at 56 ± 2 °C for 30 min and diluted in duplicates in cell growth media at a starting dilution of 1/25 or 1/250, followed by a serial dilution (2-fold dilutions, 5 times). A previously pre-determined concentration of pseudovirus was then added to diluted sera samples and pre-incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with CO2. The mixture was then added to pre-seeded confluent Vero E6 cells expressing the ACE2 receptor (ATCC CRL-1586) and incubated for 18–24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Following incubation and removal of media, ONE-Glo EX Luciferase Assay Substrate (Promega, Madison, WI) was added to cells and incubated for 3 min at room temperature with shaking. Luminescence was measured using a SpectraMax i3x microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). A titration curve was generated based on a 4-parameter logistic regression (4PL) using Microsoft Excel. The NAb titer was defined as the reciprocal of the sample dilution for which the luminescence was equal to a pre-determined cut-point value corresponding to 50 % neutralization. Responders were considered positive if the NAb titer was ≥ 25. NAb results presented in the current study were obtained using pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 virus. Note that results obtained with PNA generally correlates with live virus based microneutralization assay [28].

2.4. Statistical analyses

The descriptive statistics and statistical comparisons were performed using GraphPad Prism software (Version 8.4.2; GraphPad Prism Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). The geometric mean titers (GMT) of NAb titers with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) and percentage of positive responders were calculated for each group of mice. A titer value of 12.5 was attributed to titers lower than the minimum required dilution (MRD) (i.e., 1/25). Statistical comparisons to evaluate differences between groups were performed using either a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc test, or a two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test on log10-transformed antibody titers. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank was used to assess differences between the various SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus strains. The threshold for statistical significance was set to p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Neutralizing and Cross-Reactive antibodies induced by AS03-Adjuvanted CoVLP and CoVLP.B1351 following homologous Prime-Boost primary vaccination strategies

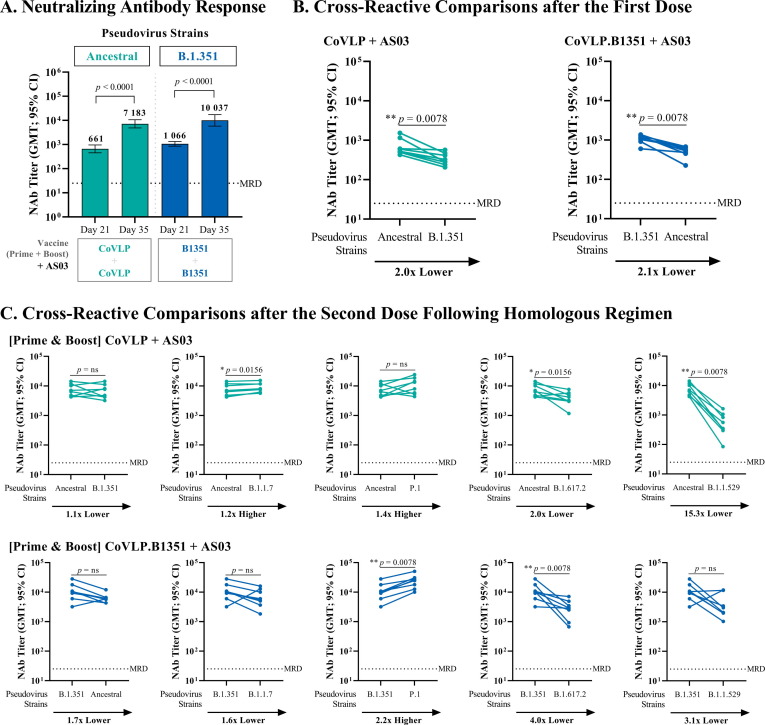

In this study, mice were immunized following either a homologous or heterologous prime-boost regimen with AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP and/or CoVLP.B1351 (Fig. 1). A single dose of either AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 induced a significant NAb response against the homologous strain (CoVLP versus ancestral strain: GMT 661 [95% CI: 454–963]; CoVLP.B1351 versus the B.1.351 strain: GMT 1 066 [95% CI: 852–1 333](Fig. 2 A). All animals in the CoVLP and CoVLP.1351 groups respectively mounted a response above the MRD after the first dose. Cross-reactivity was also observed (Fig. 2B) following a single dose of either CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 when tested against heterologous strains. These responses were ∼ 2x lower than against its homologous viral strain (both p < 0.01). NAb responses induced by either AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 were increased approximately 10-fold after the boost (both p < 0.0001) with GMT against the homologous strain of 7 183 [95% CI: 4 859–10 618] and 10 037 [95% CI: 5 816–17 324] for CoVLP and CoVLP.1351 respectively. Cross-reactive responses after two doses with either CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 were increased to similar levels against the opposite strain (Fig. 2C): CoVLP-CoVLP against the B.1.351 strain 6 363 [95% CI: 4 093–9 893] and CoVLP.1351-CoVLP.B1351 against the ancestral strain 6 066 [95% CI: 4 628–7 952] (both p > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Serum Neutralizing Antibody Response and Cross-Reactivity Comparisons of AS03-Adjuvanted CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 Following Homologous Prime-Boost Regimen. BALB/c mice (n = 8) were immunized IM on Days 0 and 21 with 3.75 µg of CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 formulated with AS03 adjuvant. NAb titers were measured against SARS-CoV-2 pseudoparticles in serum samples using a cell-based PNA targeting the ancestral or B.1.351 strains. Half of the minimum required dilution (MRD) of the method was assigned to non-responders (i.e. 12.5). (A) GMT with 95 % CI measured 21 days after the 1st immunization (Day 21) and 14 days after the 2nd immunization (Day 35). Statistical comparisons were performed using a two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test on log10-transformed NAb titers. (B-C) Results from individual mouse serum samples (n = 8 per antigen) are represented as dots on each figure with lines connecting ancestral of B.1.351 to the B.1.351, B.1.1.7, P.1, B.1.617.2 or B.1.1.529 neutralization titers. Statistical comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test. p-values are indicated on the graphs. ns: Not significant (p > 0.05).

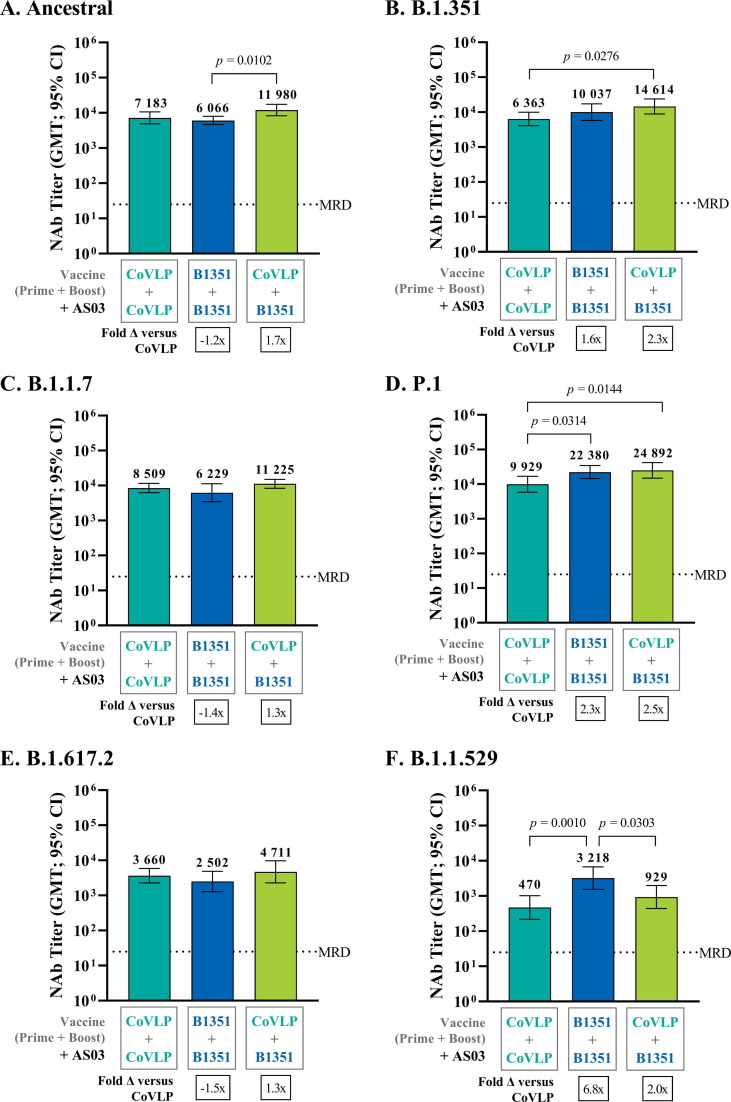

3.2. High levels of Cross-Reactive response against other VOCs

Both homologous prime-boost strategies (CoVLP-CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351- CoVLP.B1351) induced high levels of cross-reactive NAbs against several other VOCs including B.1.1.7 and P.1. (Fig. 2C). A significant decrease in NAbs was observed against the B.1.617.2 and B.1.1.529 variants (Fig. 2C). The degree of cross-reactive neutralization induced by AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP-CoVLP was similar to that elicited by AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP-B1351-CoVLP.B1351 (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3 ) except for the P.1 and B.1.1.529 strains, for which the latter strategy generated significantly higher titers (P.1 : GMT 22 380 [95% CI: 14 529–34 473] versus 9 929 [95% CI: 5 843–16 872], B.1.1.529: GMT 3 218 [95% CI: 1 547–6 693] versus 470 [95% CI: 218–1 016]: p < 0.05) (Fig. 3D and 3F). As previously shown in Fig. 2C, the degree of cross-neutralization for the AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP-CoVLP homologous prime-boost regimen varied across the tested VOCs as follows: P.1 > B.1.1.7 > B.1.351 > B.1.617.2 > B.1.1.529 and for the CoVLP.B1351-CoVLP.B1351 regimen (Fig. 2C): P.1 > ancestral/B.1.1.7 > B.1.1.529 > B.1.617.2.

Fig. 3.

Cross-Reactive Neutralization against the ancestral, Beta (B.1.351) Alpha (B.1.1.7), Gamma (P.1), Delta (B.1.617.2), and Omicron (B.1.1.529) strains Following Homologous or Heterologous Prime-Boost Regimen. BALB/c mice (n = 8) were immunized IM on Days 0 and 21 with 3.75 µg of CoVLP.B1351 or CoVLP (both formulated with AS03 adjuvant). NAb titers were measured against SARS-CoV-2 pseudoparticles in serum samples using a cell-based PNA targeting the ancestral, B.1.351, B.1.1.7, P.1, B.1.617.2 or B.1.1.529 strains. Half of the minimum required dilution (MRD) of the method was assigned to non-responders (i.e. 12.5). GMT with 95 % CI obtained 14 days after the boost (Day 35) for the (A) ancestral, (B) B.1.351, (C) B.1.1.7, (D) P.1, (E) B.1.617.2 or (F) B.1.1.529 strains. Statistical comparisons between the CoVLP-treated groups were performed using a One-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc test (Day 35) on log10-transformed NAb titers. Significant differences are indicated with p-values on the graphs.

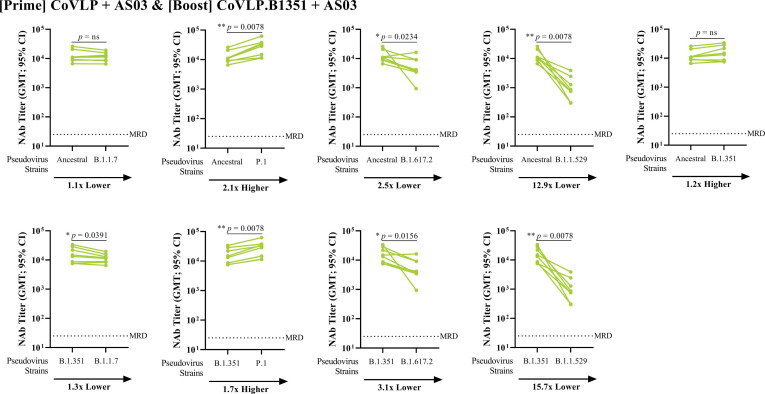

3.3. Heterologous Prime-Boost vaccination also induced a strong and Cross-Reactive antibody response to VOCs

The heterologous, AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP-CoVLP.B1351 vaccination also successfully induced high titers of NAbs against both strains included in the regimen as well as the other VOCs tested (Fig. 3), with the exception of the B.1.1.529 variant, for which NAb levels were 12–15 folds lower compared to the ancestral and the B.1.351 strains. Compared to the AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP-CoVLP group, the heterologous prime-boost group induced a significantly greater cross-reactive response for the B.1.351 (Fig. 3B) and P.1 (Fig. 3D) VOCs (p < 0.05). Compared to the CoVLP.B1351-CoVLP.B1351 homologous regimen, only the response against the ancestral strain was higher in the heterologous prime-boost group (Fig. 3A; p < 0.05). Again, a significantly lower response against the B.1.1.529 strain was observed (Fig. 3F; p < 0.05). The amplitude of the cross-reactive neutralizing antibody response after heterologous prime-boost vaccination varied across the strains tested (Fig. 4 ): P.1 > B.1.351 > ancestral/B.1.1.7 > B.1.617.2 > B.1.1.529.

Fig. 4.

Cross-Reactivity Comparisons against Alpha (B.1.1.7), Gamma (P.1), Delta (B.1.617.2), and Omicron (B.1.1.529) strains Following Heterologous Prime-Boost Regimen. BALB/c mice (n = 8) were immunized IM on Days 0 with 3.75 µg CoVLP and 21 with 3.75 µg of CoVLP.B1351 (both formulated with AS03 adjuvant). NAb titers were measured against SARS-CoV-2 pseudoparticles in serum samples using a cell-based PNA targeting the ancestral, B.1.351, B.1.1.7, P.1, B.1.617.2 or B.1.1.529 strains. Half of the minimum required dilution (MRD) of the method was assigned to non-responders (i.e. 12.5). Results from individual mouse sera (n = 8 per antigen) are represented as dots on each figure with lines connecting the ancestral or B.1.351 variant to the B.1.351, B.1.1.7, P.1, B.1.617.2 or B.1.1.529 neutralization titers. Statistical comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test. p-values are indicated on the graphs. ns: Not significant (p > 0.05).

3.4. Safety of CoVLP and CoVLP.B1351 vaccines in animals

Overall, no safety concerns were raised following homologous prime-boost strategies or the heterologous strategy. The post-immunization variations observed for body weight and food consumption were transient and/or within the normal variations (Figures S1 and S2). An unexpected increase in food consumption was observed in the CoVLP + AS03 group between Days 7–14 that was likely attributable to eating-like behavior (i.e. stashing of food pellets at the bottom of the cage) in a small number of the animals in this group. Transient signs of discomfort (Table S1) and inflammation at the dosing sites (edema and erythema) were reported in all treated groups following the prime (Figure S3). All observations generally subsided within 10–14 days and were no longer seen prior to the second administration. After the second administration, no signs of reactogenicity or discomfort were reported at the injection site. No macroscopic anomalies were reported following euthanasia and collection of organs and tissues.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The first anti-COVID-19 vaccines were approved for emergency use within a year of the start of the pandemic with reported efficacies ranging from 50 to 95% [29]. Simultaneously however, multiple viral variants have emerged in different geographic regions with varied transmissibility, virulence and resistance to vaccine-induced immunity [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]. Many parts of the world have experienced rapid replacement of the ancestral Wuhan-like strain with one or a sequence of these variants of concern “VOCs”. The different waves of variants has complicated diagnostic efforts in some cases [8], [9], [36] and generally frustrated efforts to control the spread and impact of the pandemic [37]. Among the most important VOCs that have emerged over the last year include the B.1.1.7, B.1.351, P.1/B.1.1.248, B.1.617.2 and B.1.1.529 strains [38], [39], [40], [41].

The rapid worldwide spread of some VOCs can be attributed to enhanced transmissibility. For example, transmission of the B.1.617.2 variant is at least 40% greater than the ancestral or B.1.1.7 strains [42], [43] and it is estimated that the transmission rate of the recent B.1.1.529 variant is at least 4-times higher than the ancestral strain [44]. Several lines of evidence including animal models and epidemiological observations suggest that this increased transmissibility is related to Spike protein mutations [45], [46] such as D614G [47], [48], P681R [49] or K417N/E484K/N501Y [50]. These mutations have significant functional effects related to transmissibility such as accelerated cell-to-cell spread [49] and the generation of higher virus loads in the upper airways when compared to the B.1.1.7 strain [42]. Although the relationship between different mutations and disease severity is not yet fully understood [51], recent evidence suggests that the B.1.1.7 variant is associated with a higher risk of emergency care consultation and hospital admission for unvaccinated individuals compared with B.1.1.7 variants [35]. It is very clear however that some of these mutations can confer significant resistance to antibody neutralization in vitro, particularly those present in the B.1.351 [52], [53], [54], B.1.617.2 [55], and B.1.1.529 [56] strains raising important concerns about the countermeasures available to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic [57]. Indeed, reduced neutralizing efficacy of antibodies from several of the deployed vaccines has already been demonstrated against the P.1/B.1.1.248, B.1.351, B.1.617.2, and B.1.1.529 variants in both clinical trials and real-world evidence studies [5], [11], [18], [58], [59]. In several randomized controlled trials with different vaccines, efficacy against the B.1.351 variant was observed to fall by 33–84% [15], [16], [17], [60]

Although most of the deployed vaccines continue to have good efficacy against severe disease induced by most of the VOCs identified to date [15], [61] and there is evidence of convergent evolution [62], [63], it is unlikely that SARS-CoV-2 has fully exhausted its genetic repertoire. These observations highlight the need both to evaluate the ability of vaccines already deployed or in advanced development to neutralize the VOCs and to develop next generation vaccines with broader cross-reactivity. In this study, the cross-reactive neutralizing antibody responses elicited by AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP (targeting the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain) were generally promising. Despite slight (1-2x) reductions in neutralizing activity for the B.1.351 (-1.1x) and B.1.617.2 (-2.0x) variants compared to the ancestral strain, two doses of CoVLP with AS03 still elicited high levels of serum cross-neutralizing antibodies against the VOCs tested. These observations are similar to those reported with other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines targeting the ancestral S protein [58], [64] although the decrement in neutralization for VOCs was less pronounced for CoVLP, particularly for the B.1.351 strain. Of particular note, similar trends were observed in recently reported results on neutralization of VOCs with human serum samples collected in Medicago’s ongoing clinical development program of AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP administered at 3.75 μg [65]. The B.1.1.529 variant is now well known to escape neutralization by many monoclonal antibodies and vaccine-induced humoral responses that are active against other SARS-CoV-2 variants [43], [56], [59]. Hence it is not a surprise that an important decrease in the neutralizing potential of antibodies against the B.1.1.529 variant strain was observed in the current study. Similar reductions in neutralizing antibody titers have been reported in both clinical trials [43], [56], [59] and studies in non-human primates immunized with ancestral SARS-CoV-2 vaccines [66], [67]. In the current study, the decrease in neutralizing activity was less pronounced following the administration of the candidate B.1.351 vaccine compared to the vaccine based on the ancestral strain, possibly due to the closer phylogenic relationship between B.1.351 and the Omicron variants [68].

Despite these promising data, it is possible that one or more VOCs will eventually emerge that is/are no longer effectively neutralized by vaccine-induced immunity. It is in this context that Medicago and others have chosen to develop next-generation vaccine candidates targeting the B.1.351 strain since this strain is one of the most antigenically distant VOC to emerge to date. The B.1.351 variant has consistently proved to be difficult to neutralize in vitro [69], [70] and has caused large decrements in vaccine efficacy in several randomized controlled trials [15], [16], [17], [61]. In the current study, animals that received two doses of either AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 mounted neutralizing antibody responses that were comparable for both homologous and heterologous strains while reports for other candidate B.1.351 vaccines in mice have shown either strong homologous (ie: B.1.351-specific) responses only [71] or the requirement for three doses to achieve high levels of NAbs [64]. The pattern of the NAb response was consistent across multiple VOCs in the current study with the CoVLP.B1351 candidate generally eliciting higher titers than the ancestral CoVLP and this difference reached significance for the P.1 (2.3x) and the B.1.1.529 (6.8x) strains. Although the level of cross-neutralization in the animals that received CoVLP.1351 was lower for the B.1.1.7 (-1.6x) and B.1.617.2 (-4.0x) variants compared to the homologous response, such differences are expected given the genetic and antigen ‘distance’ between these VOCs [43]. Furthermore, while these relative decreases were observed, the absolute titers of cross-reactive antibodies induced by two doses of CoVLP.B1351 with AS03 against the VOCs tested was still substantial. These findings are consistent with observations of others [64], [71], [72] and suggest that vaccines targeting the original Wuhan-like strain may be eventually become suboptimal in the next stages of the pandemic, opening the door to less conventional vaccination approaches including heterologous prime-boost strategies.

Concern over the ability of any single S protein antigen to elicit a broad enough response to neutralize all of the known and possibly future VOCs prompted us to evaluate the possible benefits of a heterologous prime-boost strategy with the Wuhan-like CoVLP as the prime and CoVLP.B1351 as the boost; both adjuvanted with AS03. Heterologous vaccination strategies that use two distinct platforms and/or deliver two slightly different antigens have shown considerable promises for a wide range of viral pathogens that rapidly mutate such as HIV [73], hepatitis C virus [74] or influenza to both broaden the immune response and focus the response on conserved epitopes [75]. This approach was largely confirmed in the current study since the neutralizing antibody titers were consistently higher in the animals that had received the AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP-CoVLP.B1351 regimen, reaching statistical significance over the AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP-CoVLP regimen for B.1.351 and P.1 strains and over the AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP.B1351-CoVLP.B1351 regimen for the ancestral strain. It is not currently known if these differences between high and very high neutralizing antibody responses will have any clinical significance. However, induction of very high initial titers is likely desirable since it is well-documented that antibody titers wane substantially with time after both natural disease and vaccination [76]. These observations are similar to the results recently released by others [72], [77] [Pfizer, Novavax] but distinct from those reported by Moderna [71] in that no evidence of original antigenic sin was noted [78]. Since these animals only received two doses, it is currently unknown how humoral response against VOCs would be influenced by a third (booster) dose but others have reported very high and cross-protective neutralizing antibody responses both in animals [64], [71] and human trials [65], [79], [80] after this additional dose.

Finally, it is worth noting that these observations focus entirely on vaccine-induced antibody responses and particularly on the induction of antibodies capable of neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 variants in vitro. Although many consider NAb levels to be a good candidate for a correlate of protection [81], this is a fairly limited evaluation of vaccine-induced immunity and it is very likely that non-neutralizing but functional antibodies and cellular responses also contribute to vaccine-induced protection [82]. Data from a large non-human primate study [83] as well as ongoing clinical trials [27], [65], [84] demonstrate that AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP stimulates multiple arms of the adaptive response to SARS-CoV-2. Results from Medicago’s ongoing pivotal Phase 3 efficacy study [25] (NCT04636697), performed in different regions of the world where several VOCs have been circulating, demonstrated a good protection of the CoVLP vaccine (targeting the ancestral strain) against several VOCs such as B.1.617.2 and P.1. These results are in line with the non-clinical cross-neutralization data presented in this study. Based on these Phase 3 results, it is unclear what immediate benefit might be gained by switching to a heterologous prime-boost strategy for primary vaccination. However, both the magnitude and the breadth of response need to be considered as SARS-CoV-2 continues to mutate under increasing immune pressure including the most recent example of the B.1.1.529 variant. The data presented herein suggest two doses of AS03-adjuvanted CoVLP or CoVLP.B1351 can induce a strong immune response against a broad range of VOCs. Moreover, recently published preclinical data also highlight the added value of a third dose [64], [71]. These observations provide further support for the growing body of data suggesting that the use of heterologous antigens, whether B.1.351 of some new VOC yet to emerge, in either primary or third-dose booster strategies may have advantages over traditional homologous antigen vaccination approaches and further clinical trials will be needed to confirm the efficacy of such vaccination strategies.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CD, SPR, GA, MAD, BJW and ST are either employees of Medicago Inc or receive salary support from Medicago Inc.

CG is an employee of the GSK group of companies and reports ownership of GSK shares.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The study was sponsored by Medicago Inc. The authors would like to acknowledge Philippe Boutet, Margherita Coccia, Marie-Ange Demoitié, Ulrike Krause and Eric Destexhe from GSK for critical review of the manuscript. The authors also wish to acknowledge all the Medicago employees and their contractors (ITR Laboratories Canada Inc and Nexelis) for their exceptional dedication and professionalism.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the submitted work. CD, SPR, GA, CG, BJW and ST contributed to design and execution of the study as well as analyses and presentation of the data. All authors contributed to critical review of the data and the writing of the manuscript. All Medicago authors had full access to the data.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.05.046.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Mean Body Weight. BALB/c mice were immunized IM on Days 0 and 21 with 3.75 µg of either CoVLP.B1351 or CoVLP (formulated with AS03 adjuvant) or control (phosphate buffered saline). Body weight for each animal (8/group, except for control 5/group) was measured prior to immunization (on Days 0 and 21), daily for 7 days post-dosing, and weekly afterwards up to Day 35. Results are reported as mean body weight (± SD) per group. At each timepoint, statistical comparisons with the control were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (except for day 22, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was performed on log10 transformed data). Significant significance was set at p < 0.05. No significant differences were observed

Mean Weekly Food Consumption. BALB/c mice were immunized IM on Days 0 and 21 with 3.75 µg of either CoVLP.B1351 or CoVLP (formulated with AS03 adjuvant) or control. Food consumption was measured weekly throughout the study period on all animals (8/group, excepted for control 5/group). Results are reported as mean weekly food consumption (± SD) per group. Statistical comparisons with the control were performed for each 7-day study period using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis followed by a Dunnett’s test on ranks. Significant differences were annotated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Aberrant measurement was reported for CoVLP + AS03 between Days 7-14 and could be explained be eating like behavior reported in animals

Injection Site Observations (Draize Scoring). Animals were injected either with CoVLP. B1351 or CoVLP (formulated with AS03 adjuvant) or control on Days 0 and 21. Injection site reaction was evaluated daily on individual mouse for 7 days post-immunization according to the Draize scoring scale and weekly thereafter. Frequency of observations is presented at the right of the histogram. Draize score is defined as: 0 = no erythema/edema; 1 = very slight erythema/edema (barely perceptible); 2 = well defined erythema (pale red in color)/slight edema (edges of area well defined by definite raising); 3 = moderate to severe erythema (definite red color)/moderate edema (area well-defined and raised approximately 1 mm); 4 = severe erythema (beet or crimson red in color) to slight eschar formation (injuries in depth)/severe edema (raised more than 1 mm and extending beyond the area of exposure). Note that no observation was recorded following the second immunization (Day 21). Therefore, only results after the first immunization are shown. Data are presented as mean Draize scoring ± SD.

References

- 1.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadoff J., Gray G., Vandebosch A.n., Cárdenas V., Shukarev G., Grinsztejn B., et al. Safety and Efficacy of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(23):2187–2201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voysey M., Costa Clemens S.A., Madhi S.A., Weckx L.Y., Folegatti P.M., Aley P.K., et al. Single-dose administration and the influence of the timing of the booster dose on immunogenicity and efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine: a pooled analysis of four randomised trials. Lancet. 2021;397(10277):881–891. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00432-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen R.E., Zhang X., Case J.B., Winkler E.S., Liu Y., VanBlargan L.A., et al. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):717–726. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01294-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X., Chen Z., Azman A.S., Sun R., Lu W., Zheng N., et al. Comprehensive mapping of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants induced by natural infection or vaccination. MedRxiv. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies N.G., Jarvis C.I., Edmunds W.J., Jewell N.P., Diaz-Ordaz K., Keogh R.H. Increased mortality in community-tested cases of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7. Nature. 2021;593(7858):270–274. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03426-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann M., Arora P., Groß R., Seidel A., Hörnich B.F., Hahn A.S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and P.1 escape from neutralizing antibodies. Cell. 2021;184(9):2384–2393.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCallum M., De Marco A., Lempp F.A., Tortorici M.A., Pinto D., Walls A.C., et al. N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2021;184(9):2332–2347.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update.

- 11.Wang P., Nair M.S., Liu L., Iketani S., Luo Y., Guo Y., et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature. 2021;593(7857):130–135. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letko M., Marzi A., Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):562–569. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walls A.C., Park Y.-J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281–292.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.-L., Abiona O., et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367(6483):1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson CY. Single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine prevents illness but shows the threat of variants. The Washington Post.

- 16.Madhi S.A., Baillie V., Cutland C.L., Voysey M., Koen A.L., Fairlie L., et al. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(20):1885–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadman M., Cohen J. Novavax vaccine delivers 89% efficacy against COVID-19 in UK—but is less potent in South Africa. Science. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez Bernal J., Andrews N., Gower C., Gallagher E., Simmons R., Thelwall S., et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 Vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):585–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Aoust M.-A., Couture M.-J., Charland N., Trépanier S., Landry N., Ors F., et al. The production of hemagglutinin-based virus-like particles in plants: a rapid, efficient and safe response to pandemic influenza. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2010;8(5):607–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemmati F., Hemmati-Dinarvand M., Karimzade M., Rutkowska D., Eskandari M.H., Khanizadeh S., et al. Plant-derived VLP: a worthy platform to produce vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Biotechnol Lett. 2022;44(1):45–57. doi: 10.1007/s10529-021-03211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thanavala Y., Mahoney M., Pal S., Scott A., Richter L., Natarajan N., et al. Immunogenicity in humans of an edible vaccine for hepatitis B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(9):3378–3382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409899102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yusibov V., Hooper D.C., Spitsin S.V., Fleysh N., Kean R.B., Mikheeva T., et al. Expression in plants and immunogenicity of plant virus-based experimental rabies vaccine. Vaccine. 2002;20:3155–3164. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward B.J., Makarkov A., Séguin A., Pillet S., Trépanier S., Dhaliwall J., et al. Efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of a plant-derived, quadrivalent, virus-like particle influenza vaccine in adults (18–64 years) and older adults (≥65 years): two multicentre, randomised phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2020;396(10261):1491–1503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tacket C., Mason H., Losonsky G., Estes M., Levine M., Arntzen C. Human immune responses to a novel norwalk virus vaccine delivered in transgenic potatoes. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(1):302–305. doi: 10.1086/315653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hager KJ, Marc GP, Gobeil P, Diaz RS, Heizer G, Llapur C, et al. Efficacy and Safety of a Plant-Based Virus-Like Particle Vaccine for COVID-19 Adjuvanted with AS03. MedRxiv. 2022:2022.01.17.22269242.

- 26.Pillet S, Couillard J, Trépanier S, Poulin J-F, Yassine-Diab B, Guy B, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a quadrivalent plant-derived virus like particle influenza vaccine candidate—Two randomized Phase II clinical trials in 18 to 49 and≥ 50 years old adults. PloS one. 2019;14:e0216533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Ward B.J., Gobeil P., Séguin A., Atkins J., Boulay I., Charbonneau P.-Y., et al. Phase 1 randomized trial of a plant-derived virus-like particle vaccine for COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01370-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tolah A.M.K., Sohrab S.S., Tolah K.M.K., Hassan A.M., El-Kafrawy S.A., Azhar E.I. Evaluation of a Pseudovirus Neutralization Assay for SARS-CoV-2 and Correlation with Live Virus-Based Micro Neutralization Assay. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11(6):994. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11060994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan Y., Pang Y., Lyu Z., Wang R., Wu X., You C., et al. The COVID-19 vaccines: recent development, challenges and prospects. Vaccines. 2021;9(4):349. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gómez CE, Perdiguero B, Esteban M. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Impact in Global Vaccination Programs against SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Janik E., Niemcewicz M., Podogrocki M., Majsterek I., Bijak M. The Emerging Concern and Interest SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Pathogens. 2021;10(6):633. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10060633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khateeb J., Li Y., Zhang H. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and potential intervention approaches. Crit Care. 2021;25:244. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nyberg T., Twohig K.A., Harris R.J., Seaman S.R., Flannagan J., Allen H., et al. Increased risk of hospitalisation for COVID-19 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant B. 2021;1(1):7. arXiv preprint arXiv:210405560. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ong SWX, Chiew CJ, Ang LW, Mak TM, Cui L, Toh M, et al. Clinical and virological features of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: a retrospective cohort study comparing B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.315 (Beta), and B.1.617.2 (Delta). Clin Infect Dis. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Twohig K.A., Nyberg T., Zaidi A., Thelwall S., Sinnathamby M.A., Aliabadi S., et al. Hospital admission and emergency care attendance risk for SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) compared with alpha (B.1.1.7) variants of concern: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00475-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andreano E., Piccini G., Licastro D., Casalino L., Johnson N.V., Paciello I., et al. SARS-CoV-2 escape from a highly neutralizing COVID-19 convalescent plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(36) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2103154118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akkiz H. Implications of the Novel Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Genome for Transmission, Disease Severity, and the Vaccine Development. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.636532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chakraborty C., Sharma A.R., Bhattacharya M., Agoramoorthy G., Lee S.-S., Goff S.P. Evolution, Mode of Transmission, and Mutational Landscape of Newly Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants. mBio. 2021;12(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01140-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faria N.R., Mellan T.A., Whittaker C., Claro I.M., Candido D.d.S., Mishra S., et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P. 1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science. 2021;372(6544):815–821. doi: 10.1126/science.abh2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tegally H., Wilkinson E., Giovanetti M., Iranzadeh A., Fonseca V., Giandhari J., et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature. 2021;592(7854):438–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thakur V., Ratho R.K. OMICRON (B.1.1.529): A new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern mounting worldwide fear. J Med Virol. 2022;94(5):1821–1824. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo C.H., Morris C.P., Sachithanandham J., Amadi A., Gaston D., Li M., et al. Infection with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant is Associated with Higher Infectious Virus Loads Compared to the Alpha Variant in both Unvaccinated and Vaccinated Individuals. MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Planas D., Veyer D., Baidaliuk A., Staropoli I., Guivel-Benhassine F., Rajah M.M., et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596(7871):276–280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Araf Y., Akter F., Tang Y.-D., Fatemi R., Parvez M.S.A., Zheng C., et al. Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: Genomics, transmissibility, and responses to current COVID-19 vaccines. J Med Virol. 2022;94(5):1825–1832. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou Y.J., Chiba S., Halfmann P., Ehre C., Kuroda M., Dinnon K.H., et al. SARS-CoV-2 D614G variant exhibits efficient replication ex vivo and transmission in vivo. Science. 2020;370(6523):1464–1468. doi: 10.1126/science.abe8499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soh S.M., Kim Y., Kim C., Jang U.S., Lee H.-R. The rapid adaptation of SARS-CoV-2-rise of the variants: transmission and resistance. J Microbiol. 2021;59(9):807–818. doi: 10.1007/s12275-021-1348-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plante J.A., Liu Y., Liu J., Xia H., Johnson B.A., Lokugamage K.G., et al. Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness. Nature. 2021;592(7852):116–121. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2895-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volz E., Hill V., McCrone J.T., Price A., Jorgensen D., O'Toole Á., et al. Evaluating the Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutation D614G on Transmissibility and Pathogenicity. Cell. 2021;184:64–75.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Callaway E. The mutation that helps Delta spread like wildfire. Nature. 2021;596(7873):472–473. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-02275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tegally H., Wilkinson E., Giovanetti M., Iranzadeh A., Fonseca V., Giandhari J., et al. Emergence and rapid spread of a new severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) lineage with multiple spike mutations in South Africa. MedRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dao T.L., Hoang V.T., Colson P., Lagier J.C., Million M., Raoult D., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infectivity and Severity of COVID-19 According to SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Current Evidence. J Clin Med. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/jcm10122635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diamond M., Chen R., Xie X., Case J., Zhang X., VanBlargan L., et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants show resistance to neutralization by many monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Research square. 2021:rs.;3:rs-228079. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01294-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Planas D., Bruel T., Grzelak L., Guivel-Benhassine F., Staropoli I., Porrot F., et al. Sensitivity of infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants to neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2021;27:917–924. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rees-Spear C., Muir L., Griffith S.A., Heaney J., Aldon Y., Snitselaar J.L., et al. The effect of spike mutations on SARS-CoV-2 neutralization. Cell Rep. 2021;34 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu C., Ginn H.M., Dejnirattisai W., Supasa P., Wang B., Tuekprakhon A., Nutalai R., Zhou D., Mentzer A.J., Zhao Y., Duyvesteyn H.M. Reduced neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 B. 1.617 by vaccine and convalescent serum. Cell. 2021;184(16):4220–4236. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cao Y., Wang J., Jian F., Xiao T., Song W., Yisimayi A., et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04385-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lazarevic I., Pravica V., Miljanovic D., Cupic M. Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Emerging Variants: what Have We Learnt So Far? Viruses. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/v13071192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu K., Werner A.P., Koch M., Choi A., Narayanan E., Stewart-Jones G.B.E., et al. Serum Neutralizing Activity Elicited by mRNA-1273 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1468–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2102179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cameroni E., Saliba C., Bowen J.E., Rosen L.E., Culap K., Pinto D., et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies overcome SARS-CoV-2 Omicron antigenic shift. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Novavax. Novavax COVID-19 Vaccine Demonstrates 89.3% Efficacy in UK Phase 3 Trial.

- 61.Novavax. Novavax Confirms High Levels of Efficacy Against Original and Variant COVID-19 Strains in United Kingdom and South Africa Trials. March 11, 2021.

- 62.van Dorp L., Acman M., Richard D., Shaw L.P., Ford C.E., Ormond L., et al. Emergence of genomic diversity and recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou H.Y., Ji C.Y., Fan H., Han N., Li X.F., Wu A., et al. Convergent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in human and animals. Protein. Cell. 2021:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s13238-021-00847-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Su D., Li X., He C., Huang X., Chen M., Wang Q., et al. Broad neutralization against SARS-CoV-2 variants induced by a modified B. 1.351 protein-based COVID-19 vaccine candidate. bioRxiv. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gobeil P.A., Pillet S., Boulay I., Charland N., Lorin A., Cheng M., et al. Durability and Cross-Reactivity of Immune Responses Induced by an AS03 Adjuvanted Plant-Based Recombinant Virus-Like Particle Vaccine for COVID-19. MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34728-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gagne M, Moliva JI, Foulds KE, Andrew SF, Flynn BJ, Werner AP, et al. mRNA-1273 or mRNA-Omicron boost in vaccinated macaques elicits comparable B cell expansion, neutralizing antibodies and protection against Omicron. bioRxiv. 2022:2022.02.03.479037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Chandrashekar A, Yu J, McMahan K, Jacob-Dolan C, Liu J, He X, et al. Vaccine Protection Against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant in Macaques. bioRxiv. 2022:2022.02.06.479285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Kandeel M., Mohamed M.E.M., Abd El-Lateef H.M., Venugopala K.N., El-Beltagi H.S. Omicron variant genome evolution and phylogenetics. J Med Virol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jmv.27515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amanat F., Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines: Status Report. Immunity. 2020;52:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Focosi D., Tuccori M., Baj A., Maggi F. SARS-CoV-2 Variants: a Synopsis of In Vitro Efficacy Data of Convalescent Plasma, Currently Marketed Vaccines, and Monoclonal Antibodies. Viruses. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/v13071211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu K., Choi A., Koch M., Elbashir S., Ma L., Lee D., et al. Variant SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines confer broad neutralization as primary or booster series in mice. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Logue J., Johnson R., Patel N., Zhou B., Maciejewski S., Zhou H., et al. Immunogenicity and In vivo protection of a variant nanoparticle vaccine that confers broad protection against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35606-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu J., Ren L., Huang X., Qiu C., Liu Y., Liu Y., et al. Sequential priming and boosting with heterologous HIV immunogens predominantly stimulated T cell immunity against conserved epitopes. Aids. 2006;20:2293–2303. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328010ad0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fournillier A., Frelin L., Jacquier E., Ahlén G., Brass A., Gerossier E., et al. A heterologous prime/boost vaccination strategy enhances the immunogenicity of therapeutic vaccines for hepatitis C virus. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1008–1019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levine M.Z., Holiday C., Jefferson S., Gross F.L., Liu F., Li S., et al. Heterologous prime-boost with A(H5N1) pandemic influenza vaccines induces broader cross-clade antibody responses than homologous prime-boost. npj Vaccines. 2019;4:22. doi: 10.1038/s41541-019-0114-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Post N., Eddy D., Huntley C., van Schalkwyk M.C.I., Shrotri M., Leeman D., et al. Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zou J., Xie X., Fontes-Garfias C.R., Swanson K.A., Kanevsky I., Tompkins K., et al. The effect of SARS-CoV-2 D614G mutation on BNT162b2 vaccine-elicited neutralization. npj Vaccines. 2021;6:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00313-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petráš M., Králová L.I. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the context of original antigenic sin. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021:1–3. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1949953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Richmond P.C., Hatchuel L., Pacciarini F., Hu B., Smolenov I., Li P., et al. Persistence of the immune responses and cross-neutralizing activity with Variants of Concern following two doses of adjuvanted SCB-2019 COVID-19 vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xie X., Zou J., Fontes-Garfias C.R., Xia H., Swanson K.A., Cutler M., et al. Neutralization of N501Y mutant SARS-CoV-2 by BNT162b2 vaccine-elicited sera. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Krammer F. A correlate of protection for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is urgently needed. Nat Med. 2021;27:1147–1148. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sette A., Crotty S. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell. 2021;184:861–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pillet S., Arunachalam P.S., Andreani G., Golden N., Fontenot J., Aye P., et al. Safety, immunogenicity and protection provided by unadjuvanted and adjuvanted formulations of recombinant plant-derived virus-like particle vaccine candidate for COVID-19 in non-human primates. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00809-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gobeil P., Pillet S., Séguin A., Boulay I., Mahmood A., Vinh D.C., et al. Interim Report of a Phase 2 Randomized Trial of a Plant-Produced Virus-Like Particle Vaccine for Covid-19 in Healthy Adults Aged 18–64 and Older Adults Aged 65 and Older. MedRxiv. 2021 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mean Body Weight. BALB/c mice were immunized IM on Days 0 and 21 with 3.75 µg of either CoVLP.B1351 or CoVLP (formulated with AS03 adjuvant) or control (phosphate buffered saline). Body weight for each animal (8/group, except for control 5/group) was measured prior to immunization (on Days 0 and 21), daily for 7 days post-dosing, and weekly afterwards up to Day 35. Results are reported as mean body weight (± SD) per group. At each timepoint, statistical comparisons with the control were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (except for day 22, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was performed on log10 transformed data). Significant significance was set at p < 0.05. No significant differences were observed

Mean Weekly Food Consumption. BALB/c mice were immunized IM on Days 0 and 21 with 3.75 µg of either CoVLP.B1351 or CoVLP (formulated with AS03 adjuvant) or control. Food consumption was measured weekly throughout the study period on all animals (8/group, excepted for control 5/group). Results are reported as mean weekly food consumption (± SD) per group. Statistical comparisons with the control were performed for each 7-day study period using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis followed by a Dunnett’s test on ranks. Significant differences were annotated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Aberrant measurement was reported for CoVLP + AS03 between Days 7-14 and could be explained be eating like behavior reported in animals

Injection Site Observations (Draize Scoring). Animals were injected either with CoVLP. B1351 or CoVLP (formulated with AS03 adjuvant) or control on Days 0 and 21. Injection site reaction was evaluated daily on individual mouse for 7 days post-immunization according to the Draize scoring scale and weekly thereafter. Frequency of observations is presented at the right of the histogram. Draize score is defined as: 0 = no erythema/edema; 1 = very slight erythema/edema (barely perceptible); 2 = well defined erythema (pale red in color)/slight edema (edges of area well defined by definite raising); 3 = moderate to severe erythema (definite red color)/moderate edema (area well-defined and raised approximately 1 mm); 4 = severe erythema (beet or crimson red in color) to slight eschar formation (injuries in depth)/severe edema (raised more than 1 mm and extending beyond the area of exposure). Note that no observation was recorded following the second immunization (Day 21). Therefore, only results after the first immunization are shown. Data are presented as mean Draize scoring ± SD.