Highlights

-

•

What is already known about this subject? Speckle-tracking strain echocardiography (STE) is added to conventional echocardiography and has been shown to detect subclinical myocardial contractile dysfunction before a reduction in LVEF.

-

•

What does this study add? In this study, we evaluate the utility of LV STE for predicting worsening CCC in patients with Chagas disease.

-

•

How might this impact on clinical practice? Screening for changes in STE-based Global Longitudinal Strain (GLS) may provide a non-invasive approach to identify patients who could benefit from earlier management, such as more frequent follow-up or initiation of treatment.

Keywords: Chagas disease, Chagas cardiomyopathy, Echocardiography, Strain imaging

Abstract

Background

Chagas disease is an endemic protozoan disease with high prevalence in Latin America. Of those infected, 20–30% will develop chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCC) however, prediction using existing clinical criteria remains poor. In this study, we investigated the utility of left ventricular (LV) echocardiographic speckle-tracking global longitudinal strain (GLS) for early detection of CCC.

Methods and results

139 asymptomatic T. cruzi seropositive subjects with normal heart size and normal LV ejection fraction (EF) (stage A or B) were enrolled in this prospective observational study and underwent paired echocardiograms at baseline and 1-year follow-up. Progressors were participants classified as stage C or D at follow-up due to development of symptoms of heart failure, cardiomegaly, or decrease in LVEF. LV GLS was calculated as the average peak systolic strain of 16 LV segments. Measurements were compared between participants who progressed and did not progress by two-sample t-test, and the odds of progression assessed by multivariable logistic regression. Of the 139 participants, 69.8% were female, mean age 55.8 ± 12.5 years, with 12 (8.6%) progressing to Stage C or D at follow-up. Progressors tended to be older, male, with wider QRS duration. LV GLS was −19.0% in progressors vs. –22.4% in non-progressors at baseline, with 71% higher odds of progression per +1% of GLS (adjusted OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.20–2.44, p = 0.003).

Conclusion

Baseline LV GLS in participants with CCC stage A or B was predictive of progression within 1-year and may guide timing of clinical follow-up and promote early detection or treatment.

1. Introduction

Chagas disease is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi and its vector for transmission are triatomine (kissing) bugs. It is a leading cause of congestive heart failure (CHF) in Latin America where approximately 6 million people are infected [1]. Migration has also resulted in an estimated 300,000T. cruzi infected individuals residing within the United States [2]. The highest prevalence is in Bolivia, with 6.1% of the entire population is affected, while the absolute number of cases is greatest in Brazil, Argentina and Mexico [3]. In a public hospital in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, 79% of patients with CHF had Chagas disease [4]. The current Bolivian guidelines include antitrypanosomal treatment (eg. benznidazole) up to age 15 years. However, some data suggests that treatment of adults with indeterminate or chronic stages may decrease Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCC) progression, mainly in non-randomized studies of patients without established cardiomyopathy [5], [6]. In patients with established CCC, treatment reduced parasite detection but was not associated with reduction in progression or cardiovascular events [7]. A method of identifying patients at highest risk of CCC progression, before the development of systolic dysfunction, may facilitate management.

Cardiac manifestations usually begin in early adulthood following acute infection and progress over decades; thus, the prevalence of clinical disease also increases with age. During the chronic phase, about 70–80% remain asymptomatic (indeterminate form) while 20–30% develop chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCC) and heart failure at a rate of 1.85% to 7% annually [3], [8]. Chronic inflammation results in myocardial fibrosis which impairs contractile function, damages the conduction system, and can lead to heart block, arrhythmias, and dilated cardiomyopathy with symptomatic HF. [9], [10], [11], [12].

While some potential risk factors have been identified, such as male sex, reinfection, parasite strain, and comorbidities, there is currently a lack of reliable predictors of worsening CCC [13]. Electrocardiographic (ECG) abnormalities and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) have been utilized to categorize Chagas cardiac disease [14]. Speckle-tracking strain echocardiography (STE) is a newer non-invasive imaging technique added to conventional echocardiography which has been shown to detect subclinical myocardial contractile dysfunction before a reduction in LVEF. In this study, we evaluate the utility of LV STE for predicting worsening CCC in patients with Chagas disease.

2. Methods

This ongoing prospective observational cohort study was conducted at the Hospital Juan de Dios, the largest public hospital in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Participants in this cohort were seropositive for T. cruzi and were enrolled between March 2016 – April 2017. They underwent an interview, physical exam, vitals, resting ECG and a limited 2D echocardiogram annually. Patients were not involved in the design and conduct of this research.

We defined Chagas severity at each visit based on a modification of the Acquatella criteria [4], [15]. Stage A is defined as seropositive patients that are asymptomatic with a normal ECG. Stage B represents seropositive patients with ECG abnormalities including right bundle branch block (RBBB), left anterior fascicular block (LAFB), left bundle branch block (LBBB), ventricular extrasystoles, atrioventricular block, atrial fibrillation/flutter, bradycardia (<50 bpm), tachycardia (>100 bpm) but without LV systolic dysfunction. Stage C is defined as seropositive patients with evidence of mild to moderate systolic dysfunction by 2D echocardiogram (EF men: 40–51%, women: 40–53%). Stage D patients are those with severe systolic dysfunction by 2D echocardiogram (EF < 40%).

Participants were included if they were classified as stage A or B at their baseline visit and had technically adequate echocardiograms (<3 LV segments missing or unanalyzable, with frame rates 70–90 FPS) available for analysis at baseline and 1-year follow-up. We focused on LV longitudinal strain as this measure is the most clinically validated and available on most echo machines. Our limited studies had apical LV views available in most patients, whereas LV short axis (for radial strain) or right ventricular apical (for RV free wall strain) were less available. We sought to identify echocardiographic markers of progression of CCC from the milder/asymptomatic stages without LV systolic dysfunction (stages A or B) to the onset of symptoms of CHF, dilated cardiomyopathy, or systolic dysfunction (stages C or D) as this marks a significant transition point in clinical care. This protocol was approved by Universidad Católica Boliviana (Santa Cruz, Bolivia), Asociación Benéfica PRISMA (Lima, Perú), Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (Lima, Perú), and Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, USA). All participants provided written informed consent for the initial study.

2.1. Serologic confirmation

Patients underwent serologic confirmation in our Santa Cruz lab by anti-T. cruzi enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Wiener Chagatest, Rosario, Argentina) and indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA) (Polychaco IHA, Buenos Aires, Argentina). For specimens with discrepant results, aliquots were tested by trypomastigote excreted-secreted antigen (TESA)-blot. Confirmed infection was defined by positive results by at least 2 assays.

2.2. Echocardiographic analysis

Echocardiograms were performed at a single site using a GE Vivid-I machine. Images were obtained with a 3.4 MHz sector transducer. LV 2D measurements were obtained in conformity with the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines [16]. Relative wall thickness, LV mass index, and fractional shortening percentage were calculated. LVEF was calculated by the modified Simpson’s biplane method using the apical four- and two-chamber views. Evaluation of LV diastolic function was based on pulsed-wave Doppler imaging of mitral valve inflow velocities, measuring peak early (E) and late (A) diastolic velocity to calculate the E/A ratio, and the E-wave deceleration time. Using tissue Doppler imaging, the average of septal and lateral early diastolic velocity (e’) and E/e’ ratio was used to estimate LV filling pressures [17].

Functional assessment of the RV was performed by analyzing M−mode derived tricuspid annular systolic plane excursion (TAPSE). In the absence of RV outflow tract obstruction and tricuspid or pulmonic stenosis, the tricuspid regurgitant velocity was used to estimate RV systolic pressure (RVSP).

We utilized a vendor-neutral offline imaging platform (Image-Arena v4, TomTec Imaging Systems) to assess averaged peak LV global longitudinal systolic strain (GLS), a summative measure of LV contractility and myocardial deformation based on the degree of systolic shortening of each segment of the LV5. It is expressed as a negative percentage, with less negative numbers indicating worse function. Using standard 2D cine end-diastolic frames from apical three, four, and two-chamber views, LV GLS was calculated as the average of 16 regional segments [16]. The software employed automatic tracking, which was manually adjusted to ensure adequate speckle colocation along the endocardial borders. All echocardiographic measurements including strain were performed jointly by two reviewers (SW, MMS) blinded to the disease classification and clinical variables.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Differences in baseline characteristics and echocardiographic measures by CCC progression status were compared using two-sample t test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The relationship between baseline LV GLS and risk of progression from asymptomatic severity classes (A or B at baseline) to stage C or D was assessed using univariate and multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for LVEF and QRS duration. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were generated comparing the discriminative performance of LV GLS versus LVEF and QRS duration for predicting progression to stage C or D. The test performance characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values) of LV GLS at different thresholds for progression to stage C or D was calculated. Statistical analysis was performed in Stata v14.2 [18].

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics

A total of 139 participants (69.8% women) with Chagas stage A (34.5%) or B (65.5%) at baseline were included in this study (Table 1). There was no difference in follow-up time between echocardiograms in the non-progressors (382 ± 59 days) vs. progressors (380 ± 67 days) p = 0.909. Mean age was 55.2 ± 12.6 years among non-progressors and 61.9 ± 9.8 years among progressed (p = 0.078), and 69.8% were female with men more likely to progress (p = 0.026). Hypertension was present in 65.7% and diabetes in 15.1%, with mean BMI 29.4 kg/m2. Of the 139 participants, 12 (8.6%) progressed to stage C or D at follow-up. Baseline QRS duration was significantly wider in participants who progressed versus those who did not (115.4 ± 25.1 vs. 95.8 ± 29.9 ms, p = 0.030) and this difference was similar at the follow-up visit (123.3 ms vs. 102.9 ms, p = 0.072); LBBB was more common in progressors (p = 0.001) as was atrial fibrillation or flutter (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics of participants by progression status.

|

Total (n = 139) |

Not Progressed (n = 127) |

Progressed (n = 12) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | 55.8 ± 12.5 | 55.2 ± 12.6 | 61.9 ± 9.8 | 0.078 |

| Female, % | 69.8 (97) | 72.4 (92) | 41.7 (5) | 0.026 |

| Hypertension, % | 65.7 (88) | 67.7 (84) | 40.0 (4) | 0.076 |

| Systolic, mmHg | 123.9 ± 23.4 | 123.9 ± 23.7 | 124.3 ± 21.1 | 0.947 |

| Diastolic, mmHg | 75.6 ± 12.7 | 75.2 ± 12.7 | 79.3 ± 12.6 | 0.282 |

| Diabetes, % | 15.1 (21) | 15.0 (19) | 16.7 (2) | 0.704 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.4 ± 6.4 | 29.3 ± 6.5 | 30.1 ± 5.3 | 0.694 |

| Chagas treatment, % | 10.1 (14) | 10.2 (13) | 8.3 (1) | 0.931 |

| Chagas Stage A, % | 34.5 (48) | 34.7 (44) | 33.3 (4) | 0.927 |

| Chagas Stage B, % | 65.4 (91) | 65.4 (83) | 66.7 (8) | – |

| Baseline Visit ECG | ||||

| Heart rate, bpm | 66.8 ± 9.9 | 66.9 ± 10.1 | 65.5 ± 8.5 | 0.638 |

| PR interval, ms | 167.1 ± 23.9 | 166.6 ± 24.1 | 173.5 ± 21.2 | 0.380 |

| QRS duration, ms | 97.5 ± 29.9 | 95.8 ± 29.9 | 115.4 ± 25.1 | 0.030 |

| QTc, ms | 425.9 ± 25.5 | 426.3 ± 24.4 | 420.7 ± 36.9 | 0.485 |

| LBBB, % | 0.7 (1) | 0 (0) | 8.3 (1) | 0.001 |

| RBBB or Incomplete RBBB, % | 10.8 (15) | 10.2 (13) | 16.7 (2) | 0.493 |

| LPFB, % | 2.2 (3) | 1.6 (2) | 8.3 (1) | 0.124 |

| LAFB, % | 12.9 (18) | 12.6 (16) | 16.7 (2) | 0.688 |

| IVCD, % | 4.3 (6) | 3.2 (4) | 16.7 (2) | 0.085 |

| AV Block 1st Degree, % | 8.6 (12) | 8.7 (11) | 8.3 (1) | 0.969 |

| AV Block 2nd or 3rd Degree, % | 0.7 (1) | 0.8 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.758 |

| AFib or Flutter, % | 1.4 (2) | 0 (0) | 16.7 (2) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged QT, % | 1.4 (2) | 1.6 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.661 |

| Follow-up Visit ECG | ||||

| Heart rate, bpm | 68.6 ± 13.2 | 68.9 ± 13.7 | 65.6 ± 4.5 | 0.403 |

| PR interval, ms | 159.5 ± 21.1 | 158.8 ± 20.8 | 168.0 ± 23.3 | 0.187 |

| QRS duration, ms | 104.7 ± 37.5 | 102.9 ± 37.5 | 123.3 ± 32.9 | 0.072 |

| QTc, ms | 422.3 ± 44.5 | 421.3 ± 45.6 | 432.5 ± 30.7 | 0.409 |

| LBBB, % | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| RBBB or Incomplete RBBB, % | 15.1 (21) | 13.4 (17) | 33.3 (4) | 0.065 |

| LPFB, % | 0.7 (1) | 0 (0) | 8.3 (1) | 0.001 |

| LAFB, % | 18.0 (25) | 16.5 (21) | 33.3 (4) | 0.148 |

| IVCD, % | 2.9 (4) | 2.4 (3) | 8.3 (1) | 0.237 |

| AV Block 1st Degree, % | 3.6 (5) | 3.2 (4) | 8.3 (1) | 0.357 |

| AV Block 2nd or 3rd Degree, % | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| AFib or Flutter, % | 2.2 (3) | 0.8 (1) | 16.7 (2) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged QT, % | 0.7 (1) | 0.8 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.758 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD for continuous variables, or % (n) for dichotomous variables.

ECG, electrocardiogram; LBBB, left bundle branch block; RBBB, right bundle branch block; LAFB, left anterior fascicular block; IVCD, intraventricular conduction delay; LPFB, left posterior fascicular block.

3.2. Echocardiographic features at baseline by progression status

LVEF was lower among progressors compared to non-progressors at baseline (58% ± 7.3 vs. 63% ± 4.6, p < 0.001) and follow-up (Table S1 in supplemental) with similar findings for LV fractional shortening. LV mass and chamber size (internal diameter in diastole or systole) were greater in progressors than in non-progressors, but this difference was attenuated after accounting for sex or indexed to body surface area. LV GLS was more negative (normal values tend to be more negative) in those who remained stage A or B at follow-up compared to those who progressed (–22.4% vs. −19.0%, p < 0.001) to stage C or D (Figure S1, supplemental) with similar findings for segmental strain in all 16 segments. LV diastolic function was generally comparable in the two groups at baseline, with a trend towards septal and lateral tissue doppler velocities being lower in progressors (which became significant at follow-up) but was not significantly associated with progression. Measures of right ventricular function were similar in the two groups.

3.3. Relationship between baseline LV strain and progression of cardiomyopathy

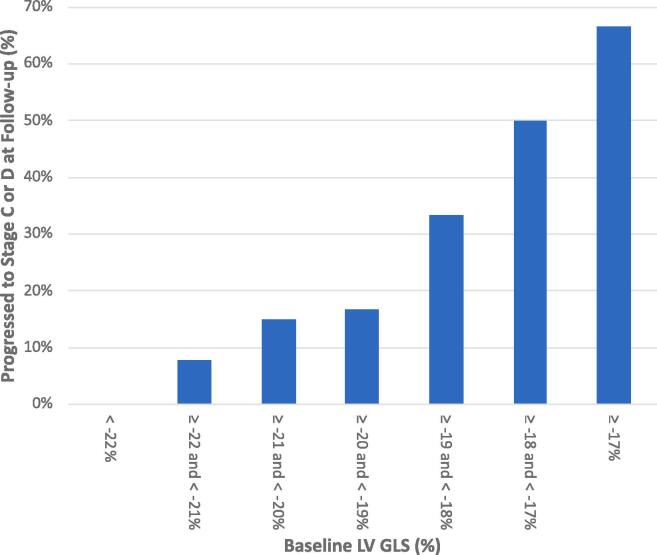

Each 1% increase (more positive) in LV GLS was associated with an 82% higher risk of progression from stage A/B to stage C or D in univariate analyses (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.32–2.51, p < 0.001) and 76% higher risk after adjusting for age and sex (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.24–2.51, p = 0.002) (Table 2). In a multivariable model, LVEF and QRS duration were not found to be predictors of progression whereas LV GLS remained significant (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.20–2.44, p = 0.003). Similar results were obtained using ordinal logistic regression considering the progression from A/B to C as 1 category increase and A/B to D as 2 categories increase. In comparing the accuracy of LV GLS with LVEF and QRS duration in predicting progression to stage C or D, an Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.890 (95% CI 0.82 – 0.96) was obtained for LV GLS versus 0.735 for LVEF (95% CI 0.58–0.89; p = 0.073) and 0.760 for QRS duration (95% CI 0.65–0.87; p = 0.017) (Fig. 1). Combining the three parameters (LV GLS, LV EF, QRS duration) in a multivariable logistic regression produced an AUROC of 0.906 which was not statistically significantly different from LV GLS alone for prediction of progression. Within each percentage of baseline LV GLS, more positive values had a greater percentage of patients progressing to stage C or D (Fig. 2). Table S2 (supplemental) shows the corresponding test characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, positive [PPV] and negative [NPV] predictive values, and accuracy) of LV GLS using various thresholds to define abnormal, within our study population where the progression rate was 8.6% in 1 year (i.e. prevalence of progression). Using an LV GLS threshold of ≥−21% results in 30.2% of subjects testing positive (abnormal) and produces a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 75%; whereas a threshold of ≥−18% gives a sensitivity of 33% and specificity of 98% with only 5.0% of all subjects testing positive.

Table 2.

Relationship between baseline measures and progression of cardiomyopathy.

| OR (95% CI)* | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||

| LV GLS (per +1%)** | 1.82 (1.32–2.51) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | ||

| LV GLS (per +1%)** | 1.76 (1.24–2.51) | 0.002 |

| Age (per 1 year) | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) | 0.705 |

| Female | 0.41 (0.10–1.59) | 0.196 |

| Model 3 | ||

| LV GLS (per +1%)** | 1.71 (1.20–2.44) | 0.003 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 1.10 (0.93–1.31) | 0.259 |

| QRS duration (per 10 ms) | 1.28 (0.97–1.70) | 0.083 |

*Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval from univariate and multivariate logistic regression.

** LV GLS, left ventricular global longitudinal systolic strain.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for LV GLS, LVEF and QRS duration. * LV GLS, left ventricular global longitudinal systolic strain. LV EF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Fig. 2.

Progression to Stage C or D at follow-up by Baseline LV GLS. LV GLS, left ventricular global longitudinal systolic strain.

4. Discussion

Non-invasively detecting the incidence or progression of CCC has been of interest for decades, particularly in regions where T. cruzi is endemic. We evaluated echocardiographic GLS longitudinally for predicting the transition from CCC stage A/B to the onset of mild to moderate (stage C) or severe systolic dysfunction (stage D) as this represents a clinically meaningful point associated with worsening symptoms and the need to initiate goal-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for heart failure, as well as greater overall healthcare system utilization.

Electrocardiographic (ECG) abnormalities are among the earliest markers of cardiac involvement in Chagas disease. Studies using ECG in the 1980s found that the highest incidence of new conduction deficits occurred in 15 to 19 year-olds, and those with baseline RBBB had 7.3-fold increased mortality over the 7-year follow-up [19], [12]. Lengthening of the QRS interval by 5 ms was predictive of a 5% decrease in LVEF in subsequent follow-up and intraventricular conduction delay is considered a poor prognostic indicator in CHF [20], [21].

Echocardiography in Chagas disease can be relatively normal, or show regional wall motion abnormalities, thinning and ventricular aneurysms. Advanced CCC can present as a globally hypokinetic, biventricular dilated cardiomyopathy with associated functional mitral and tricuspid regurgitation [15]. Strain is a quantitative measure of myocardial deformation defined as the change in length of a segment relative to its original length and can be obtained using 2D speckle-tracking echocardiography. It has been used to detect subclinical abnormalities in myocardial contractility in several disease states, and often precedes a decrease in LV ejection fraction. In Chagas disease strain has been used in the indeterminate form to detect myocardial involvement [22] and correlates with the amount of fibrosis detected by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging [23]. GLS of the RV free wall is the most accurate method of detecting RV systolic dysfunction (RV EF < 50%) as defined by CMR [24]. In later stages, it has been shown to predict cardiac events, adding prognostic information beyond LVEF and E/e’ [25].

Our study demonstrates that STE-based GLS is predictive of future (1-year) progression of CCC and could be used to identify patients at highest risk who may benefit from closer follow-up. Multivariable analysis (Table 2) and ROC curves (Fig. 1) show that GLS was the strongest predictor when compared to LVEF and QRS duration by ECG. There appeared to be a relatively linear relationship (Fig. 2) with higher (more positive) values of GLS having a greater proportion of patients progressing at follow-up. Surprisingly, some patients still progressed even with values of strain considered to be fairly normal at baseline (–22 to −20%) indicating that super-normal values (<–22%) are needed if attempting to completely eliminate the risk. Because the performance of strain can be dependent on image quality, frame rate, experience, and equipment – it is important to standardize the acquisition and analysis as much as possible [26]. Furthermore, the values of strain obtained will differ slightly by software used (eg. GE vs. Philips[TomTec]) but a recent comparison showed that longitudinal strain (GLS) had the lowest bias between these two vendors [27].

4.1. Clinical and health-system implications

In Table S2 we present test characteristics using GLS at various abnormal cutpoints. Because of the relatively small sample size, these values should be considered estimates and serve as a guide to true performance if deployed in a population setting. Our cohort was recruited in Bolivia and had a 1-year progression rate of 8.6% which may not be representative across different countries or settings. The prevalence of progression would affect positive and negative predictive values but would not be expected to change sensitivity or specificity significantly.

These results could be used to support a high-sensitivity screening strategy to simultaneously identify high-risk patients, while reassuring low-risk patients and lengthening their follow-up intervals. For example, choosing a threshold of ≥−21% would result in 30% of patients testing positive and a quarter of them (24%) progressing within a year. These individuals could be brought back in 6 months for repeat testing, while the remaining 70% who tested negative could be deferred for 1–2 years with a high NPV (98%) and cost savings to the system. The precise specifications and benefits of such a program would need to be validated in larger and longer-term studies. The data also suggests a more diagnostic use case to detect subclinical myocardial involvement with a normal ejection fraction. Selecting a threshold of ≥−18% would result in over half (57%) of the 5% who test positive progressing within a year.

Treatment of chronic Chagas infection with trypanocidal therapy (benznidazole) in the early stages of disease is guideline recommended [14]. However, in the BENEFIT trial, treatment of patients with established cardiomyopathy did not reduce the risk of progression or cardiovascular events [7]. The Viotti (2006) study [6] did show a reduction in progression, but was a smaller non-randomized trial where participants were younger and at an earlier stage of disease (Kuschnir groups 0, I or II) [28]. About 34% of participants in that study had ECG abnormalities related to Chagas, but without clinical signs of heart failure or LV dysfunction – similar to stage A/B in our population. The different results could be explained by trial design, treatment at an earlier stage before the onset of cardiac damage, or differences in parasite susceptibility. Methods of detecting subclinical or early disease, such as STE-strain, could have a role in developing treatment strategies or facilitating future research.

5. Limitations

The main limitations of our study are the small sample size, and short duration (1-year) of follow-up. Because of this, there were very few events (participants who progressed) in our study. Combining stages A and B in our analysis was therefore also necessary for statistical and sample size considerations. We were not able to evaluate progression from A and B separately, which is also of great clinical interest and would need to be studied in a larger population. Other studies have shown that patients with a normal ECG (stage A) have a lower risk of progression than those with characteristic ECG abnormalities (stage B) [6], [12]. We were not able to obtain RV strain, and strain analyses also have some inherent variability, can be technically difficult to perform reproducibly, and may not be available in all echocardiographic laboratories. Echo strain is not as widely available or as quick and low-cost as ECG, which may limit the real-world applicability of our findings. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other populations or countries with Chagas disease.

6. Conclusion

In summary, STE-based GLS was predictive of progression of CCC and the development of systolic dysfunction in our cohort of seropositive Chagas patients with stage A or B disease at baseline. Screening for these changes may provide a non-invasive approach to identify patients who could benefit from earlier management, such as more frequent follow-up or initiation of treatment. Further studies would be needed to confirm the utility of GLS as a screening tool at the population level as well as determine feasibility and cost-effectiveness in regions where Chagas disease is endemic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The Chagas Working Group includes:

Sassan Noazin and Fatemeh Jahan Bakhsh from Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Jessy Condori, Margot Ramirez Jaldin, Eliana Carolina Saenza Vasquez, Steffany Vucetich and.

Lorena Guibarra all affiliated with Asociación Benéfica Prisma. Santa Cruz, Bolivia.

Contributorship Statement

Robert H. Gilman, Caryn Bern, Freddy Tinajeros, Monica Mukherjee, Jorge Flores, and Manuela Verastegui were involved in planning of the study. Paula Carballo Jimenez, Ronald Gustavo Durán Saucedo, Lola Camila Telleria, Brandon Mercado Saavedra, Monica Miranda-Schaeubinger, and Sithu Win were involved in conduct of the research, Monica Miranda-Schaeubinger, Sithu Win, Paula Carballo Jimenez, Ronald Gustavo Durán Saucedo, Anne Raafs, Stephane Heymans, Rachel Marcus, Robert H. Gilman, and Monica Mukherjee were involved in reporting of work. Robert H. Gilman is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Subject terms

Echocardiography, cardiomyopathy, heart failure.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health - 1R01AI107028-01A1. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2022.101060.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Chagas disease in Latin America an epidemiological update based on 2010 estimates. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2015;90:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bern C., Montgomery S.P. An estimate of the burden of Chagas disease in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e52–e54. doi: 10.1086/605091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nunes M.C.P., Beaton A., Acquatella H., et al. Chagas Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Current Clinical Knowledge and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138:e169–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hidron A.I., Gilman R.H., Justiniano J., et al. Chagas cardiomyopathy in the context of the chronic disease transition. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010;4:e688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bern C. Antitrypanosomal therapy for chronic Chagas’ disease. N.Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2527–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1014204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viotti R., Vigliano C., Lococo B., et al. Long-term cardiac outcomes of treating chronic Chagas disease with benznidazole versus no treatment: a nonrandomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006;144:724–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morillo C.A., Marin-Neto J.A., Avezum A., et al. Randomized Trial of Benznidazole for Chronic Chagas’ Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:1295–1306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bern C. Chagas’ Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:456–466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1410150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rassi A., Rassi A., Marin-Neto J.A. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin-Neto J.A., Cunha-Neto E., Maciel B.C., et al. Pathogenesis of chronic Chagas heart disease. Circulation. 2007;115:1109–1123. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.624296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rassi A., Rassi A., Little W.C. Chagas’ heart disease. Clin. Cardiol. 2000;23:883–889. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960231205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maguire J.H., Hoff R., Sherlock I., et al. Cardiac morbidity and mortality due to Chagas’ disease: prospective electrocardiographic study of a Brazilian community. Circulation. 1987;75:1140–1145. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.6.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prata A. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of Chagas disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:92–100. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Andrade J.P., Marin-Neto J.A., de Paola A.A.V., et al. I Latin American guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas cardiomyopathy. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2011;97:1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acquatella H. Echocardiography in Chagas heart disease. Circulation. 2007;115:1124–1131. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.627323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang R.M., Bierig M., Devereux R.B., et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagueh S.F., Smiseth O.A., Appleton C.P., et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016;29:277–314. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station. ;TX: StataCorp LP.

- 19.Maguire J.H., Mott K.E., Hoff R., et al. A three-year follow-up study of infection with Trypanosoma cruzi and electrocardiographic abnormalities in a rural community in northeast Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1982;31:42–47. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nascimento B.R., Araújo C.G., Rocha M.O.C., et al. The prognostic significance of electrocardiographic changes in Chagas disease. J. Electrocardiol. 2012;45:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashani A., Barold S.S. Significance of QRS complex duration in patients with heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005;46:2183–2192. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.García-Álvarez A., Sitges M., Regueiro A., et al. Myocardial deformation analysis in Chagas heart disease with the use of speckle tracking echocardiography. J. Card. Fail. 2011;17:1028–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomes V.A.M., Alves G.F., Hadlich M., et al. Analysis of Regional Left Ventricular Strain in Patients with Chagas Disease and Normal Left Ventricular Systolic Function. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016;29:679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreira H.T., Volpe G.J., Marin-Neto J.A., et al. Right Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction in Chagas Disease Defined by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: A Comparative Study with Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017;30:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos Junior OR, da Costa Rocha MO, Rodrigues de Almeida F, et al. Speckle tracking echocardiographic deformation indices in Chagas and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: Incremental prognostic value of longitudinal strain. PLoS One 2019;14:e0221028. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0221028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Chan J., Shiino K., Obonyo N.G., et al. Left Ventricular Global Strain Analysis by Two-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: The Learning Curve. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017;30:1081–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugimoto T., Dulgheru R., Bernard A., et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal left ventricular 2D strain: results from the EACVI NORRE study. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2017;18:833–840. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jex140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuschnir E., Sgammini H., Castro R., et al. Evaluation of cardiac function by radioisotopic angiography, in patients with chronic Chagas cardiopathy. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 1985;45:249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.