Abstract

Background

Although half of Rohingya refugees are women and adolescent girls, the sexual and reproductive health issues of these vulnerable groups are still unexplored. The aim of this study was to review and describe menstrual hygiene management (MHM) along with the existing challenges of MHM among Rohingya adolescent girls.

Methods

This concurrent mixed methods study was conducted among adolescents aged 13–18 years living in Kutupalong refugee camps in Ukhiya, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Camp-based surveys along with focus group discussions were performed for data collection. The findings of a total of 12 FGDs and 101 survey responses were included for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used for quantitative data analysis, and thematic analysis was considered for the qualitative data.

Observation and results

Approximately one-fourth of the adolescent girls (28.71%) had premenstrual knowledge. Only 8% had “Good” knowledge, and 12% had a basic understanding. Half of the women used cloths during menstruation, while others (20.79%) used homemade clean pads, disposable sanitary pads (17.82%), and used only underwear without absorbance (10.89%). The frequency of changing sanitary pads varied, but the majority of respondents (48.51%) changed padding at least once daily. Common disposal places were inside the toilet (30.69%), open spaces (17.82%), dustbins (6.93%) and water sources (3.96%). An inadequate and irregular supply of sanitary napkins or absorbents leads to poor MH practices. Limited cleaning and disposal facilities, lack of privacy in camps or informal settlements, confined and crowded places and nonsupportive environments in the camp were also factors affecting the use of pads and disposal. Family and cultural beliefs, stigma, restrictions, and fear of sexual violence were also noted within typical day-to-day activities during menstruation.

Conclusions

The provision of adolescent-friendly wash facilities, appropriate information and adequate menstrual supplies is needed to improve the MH response in an emergency context. Despite some limitations, this study could lead to future changes relative to MH for women and adolescents in Rohingya.

Keywords: Menstruation, Adolescent, Emergency crisis, Rohingya crisis

Menstruation; Adolescent; Emergency crisis; Rohingya crisis.

1. Introduction

The Rohingya people of Myanmar are among the most persecuted communities globally and are often forced to flee their homes to escape conflict and persecution [1]. Bangladesh has been hosting Rohingya refugees from Myanmar for nearly three decades, with an estimated 303,070 individuals entering during that time [2, 3, 4]. However, the most recent outbreaks of violence by the Myanmar army among the Rohingya communities since 25 August 2017 resulted in an influx of >700,000 Rohingyas in Cox's Bazar (specifically in two subdistricts: Ukhia and Teknaf), the southeast coastal district of Bangladesh [4]. The sudden influx of this large population poses a challenging situation for Bangladesh as a host country that must immediately respond to the urgent need for food, shelter, clean water, and healthcare to treat injuries and traumas [5, 6]. With limited resources, the Bangladesh government faces significant capacity issues in response to the current refugee crisis. The government has pledged to provide equitable access to health services focusing on emergency health services, infectious disease, seasonal threats, and sexual and reproductive health (SRH), including obstetrics care [7]. Bangladeshi nongovernment organizations (NGOs) and religious institutions that are also engaging in relief work have played a prominent role in the response. However, UN agencies are also aiding in the response to resolve the crisis and needs of the refugees in an integrated way [8, 9].

It is evident that 52% of the Rohingya population is comprised of women and adolescent girls, and one in six families is headed by a single mother [10]. This high population of refugees require services that go beyond basic care, including antenatal care, postnatal care, hygiene care, and care during menstruation, which is a pervasive issue for women globally [7, 11]. During times of crisis and disaster, humanitarian response seeks to provide relief support for the suffering population by meeting essential needs in a comprehensive and predictable manner where shelter, food, clean water and medicine are prioritized. However, the provision of menstrual management remains overlooked during such disasters [11, 12].

In these situations, women and girls lack access to basic materials, such as sanitary pads, cloths, and underwear that are needed to manage monthly blood flow [13, 14, 15]. Privacy is often nonexistent in transit, camps or informal settlements [12, 16]. Moreover, the vulnerable community lacks proper knowledge about menstrual health and menstruation [17]. Rohingya women mostly use natural materials such as mud, leaves, dung, or animal skins to manage their menstrual flow [10, 17]. This is despite the provision of menstrual hygiene products as part of their dignity kits, which they may feel uneasy using as it requires changing or washing reusable sanitary pads/cloths or disposing of them privately and hygienically in the same spaces used by men. In addition, the lack of access to water and personal latrines and the consequential increase in open defecation puts women and children at increased risk of diseases [10].

Despite the activities of the ‘Sexual and Reproductive Health Working Group,’ coordinated by UNFPA and other partner organizations [7], very few initiatives encourage and provide the current knowledge, practices, and barriers to hygienic menstrual practices among vulnerable women and young adolescent groups. There is no situation analysis readily available to foster integrated and sustainable health promotion; prevention plans would be best suited for adolescent girls and women aged 12–59 years in the Rohingya refugee camps. Considering this, the study was designed to assess the constraints on and current practices of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in the Rohingya camps in Bangladesh.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and study design

This concurrent mixed methods study (using qualitative and quantitative techniques) was carried out for six months covering July–December 2019 in the Kutupalong refugee camp in Ukhiya, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. The study population was comprised of adolescent girls (13–18 years) with a history of menarche who were forcedly displaced from the Rakhine state of Myanmar, migrated to Bangladesh on 25 August 2017 and resided in the refugee camps of one of the selected subdistricts of Cox's Bazar districts. This study aimed to explore the management pattern of the menstrual cycle and the challenges of Rohingya adolescent girls with regards to MH. Informed written consent was obtained from the respondents who were at least 18 years old and literate. In the case of minors, informed consent was taken from the guardian, either parents or husbands. Thumbprints signatures were allowed to obtain consent for those who were illiterate. This study focused on participants' access to basic materials and privacy necessary to manage monthly blood flow; it also examined existing practices, taboos and health education regarding menstruation among the study population. Camp-based surveys and focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted for data collection.

Study place: Data collection was confined to one refugee camp in Ukhia Upazila, which is part of district Cox's Bazar, located in the Chittagong division. The coordinate of Ukhia upazila is 21.2126 N92.1634 E. The camp is almost 400 km southeast of Dhaka. Kutupalong is a huge tent city that houses more than 500,000 inhabitants including the residents of the Balukhali camp.

2.2. Data collection procedure

Quantitative: For quantitative data, a semistructured questionnaire was used. The questionnaire focused on the demographic profiles of the respondents, perception and knowledge regarding menstrual hygiene, frequency of engagement in MH activity, materials for managing the menstrual cycle, implementation challenges, existing taboos and social stigma. Detailed literature was searched before preparing the questionnaire. Insight from the researcher was also used to prepare the final questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed in English and then translated to Bengali by an experienced translator. The survey was conducted in the local Rohingya (arakan) language with the assistance of a local female interpreter. The responses were recorded in Bengali by the interpreter and then back translated into English. Rechecking and verification of the internal consistency of responses were completed on the day of data collection. Before finalization, the translated questionnaire was pretested on 20 Rohingya refugee adolescent girls with their consent. The experience of the pretesting was adjusted during the finalization of the questionnaire. The researcher was directly engaged in data collection and data management.

Qualitative: For the qualitative data, focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted at both study sites. On each day, 7–10 participants were included in each group discussion. Similarly, on average, 10 participants were interviewed with the aid of a questionnaire by KP. Samples were selected purposively from adolescents who were willing to participate and provided informed consent.

Detailed procedure of FGD: A total of 12 FGDs were conducted to gain insight into the adolescents knowledge and practice levels, sources of menstrual hygiene information available to them, and possible barriers to maintaining personal hygiene. The total number of participants was limited to 10, with the best possible inhomogeneous representation. These girls were selected based upon predetermined criteria: the age range was 13–18 years, and they willingly participated in the study by signing an informed consent form. A checklist was used during the FGD, keeping the objectives of the study in mind.

Initially, the local facilitators (camp supervisors) maintained communication prior to participation, and all procedures and the study's aim and objectives were described in detail during a preliminary meeting. All queries were answered by the data collection team. Health camp nurses were involved in FGD sessions along with KP and her team to create a relaxed environment. The FGD was conducted in the Bengali and local Rohingya languages with the help of female volunteers and interpreters. After initial contact and confirmation by signing a consent form, a round sitting arrangement was used during FGDs devoid of any disturbances. The place was clean, well ventilated, and had adequate space to accommodate all participants and researchers. The principal investigator (KP) participated in each focus group discussion to make the session livelier. Sessions were audio recorded to document all responses with prior permission. Additionally, written notes were taken during the interview. The interview was conducted in approximately 90 min with proper ethical implications. The statements were recorded in Bengali and translated into English by an experienced translator.

2.3. Data management

Quantitative data: A total of 101 questionnaires were collected, excluding all participants of the FDGs. The investigator collected all data, and a manual check was performed. An automated check was performed after data entry in the spreadsheet of the statistical software. Missing and inconsistent data were addressed carefully and removed from the analysis.

Qualitative data: Data were collected by the research team through written and audio recordings. Data were retrieved from audio recordings and were transcribed in a preset format. These data were then rechecked and compared with the notes taken by the KP and others. Final data editing and verification were performed by the principal investigator (KP). After preparation of the transcript (in Bangla), it was professionally translated into English in accordance with the objectives of the study. Following English translation, the manuscript was rechecked and reviewed by the principal investigator, and final encoding and analysis were performed. All data were written and sorted under a prefixed theme, and the complete transcript was prepared for qualitative data analysis. In the event there was any confusion in understanding a word or sentence, three of the investigators collectively reviewed the interpretation.

2.4. Assessment of knowledge and practice

Key parameters to assess knowledge and practice were customized for this study. Insight was taken from the study by Yadav et al. [8, 18]. The classification of the knowledge and practice level of each respondent was made on the basis of the score calculated. The range for the level of knowledge was classified and estimated using the formula Mean + S. D at 90% C.I. at both schools. According to this value, any respondents who scored below this particular calculated score classified as having ‘Poor Knowledge/practice’ and those who scored above classified as having ‘Good Knowledge/practice’; likewise, the respondents with a score in the same range classified as having ‘Average Knowledge/practice’.

2.5. Ethical consideration and informed written consent

The researcher was duly concerned about the ethical issues related to the study. Formal ethical clearance was given by the Institutional review board (IRB) of the American International University-Bangladesh (AIUB) for conducting the study, and formal permission was obtained from the responders. Confidentiality was maintained properly. Informed written consent was obtained from the subjects informing them of the nature and purpose of the study, the procedure of the study, the right to refuse and withdraw from participation in the study, and the participants did not gain financial benefit from this study.

2.6. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were provided to describe the study population, where categorical variables were summarized by using frequency tables, and continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations. Series of steps (e.g., broad impression, identification of the key themes, condensing the text from the code, and exploring meaning & synthesizing) were followed during qualitative data analysis, which was adopted from Malterud's ‘systematic text condensation’ procedure [19]. The key themes identified from the data were shared with the entire research team for additional validation and discussion. Subsequently, the presentation of the results was shared under the major analytical theme and triangulated with the analysis of the quantitative part.

3. Result

This study presents the results of quantitative and qualitative analyses regarding the constraints and current practices of menstrual hygiene of 101 adolescent girls in the Rohingya refugee camp.

3.1. Quantitative analysis

The mean age of the studied adolescent girls was 14 (±1.58) years. More specifically, half (55.4%, n = 56) of the respondents were studying or studied up to primary school, and 30.7% (n = 31) of the respondents were illiterate. 36.4% (n = 37) of the respondents’ fathers were illiterate. The majority of them (62.37%, n = 63) had been residing in the Rohingya refugee camp for 1–2 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents (n = 101).

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | 13-15 years | 82 (81.12) |

| 15-18 years | 19 (18.88) | |

| Mean (±SD) years | 14 (±1.58) | |

| Religion | Muslim | 95 (94.05) |

| Others | 6 (5.95) | |

| Education | Illiterate | 31 (30.7) |

| Primary School | 56 (55.4) | |

| Secondary School | 14 (13.9) | |

| Marital Status | Unmarried | 21 (20.79) |

| Married | 80 (79.21) | |

| Education of Mother | Illiterate | 48 (47.52) |

| Literate | 53 (52.48) | |

| Education of Father | Illiterate | 37 (36.64) |

| Literate | 64 (63.36) | |

| Duration of staying in Refugee Camp | <1 year | 16(15.84) |

| 1 year-2 years | 63 (62.37) | |

| >2 years | 22 (21.79) |

Table 2 shows that 66.8% (n = 67) of girls knew that menstruation was a physiological process, and 20.79% (n = 21) believed it was a curse. Among the girls, 47.52% (n = 48) obtained knowledge of menstruation before attaining menstruation. Fifty-five percent (54.45%) were scared during menarche, 27.72% (n = 28) felt discomfort and 11.88% (n = 12) felt irritated. Forty-one (40.59%) respondents received information about menstruation from their mother. More than half of the studied girls felt embarrassed during menstruation (Table 2). Only 7.92% of respondents availed themselves of gender-specific restroom facilities on the camp. Approximately 64.8% of the respondents were not satisfied with the toilet facilities, and 77.4% reported unavailability of adequate soap and water in the washroom. Approximately 72.5% were not satisfied with privacy in the camp's toilet (Table 3).

Table 2.

Knowledge and perception about menarche & menstruation (n = 101).

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age of Menarche | 9-11 years | 51 (50.49) |

| 12-14 years | 42 (41.58) | |

| ≥15 years | 8 (7.92) | |

| Mean (±SD) years | 12 ± 1.56 | |

| Reaction on Menarche | Scared | 55 (54.45) |

| Depressed | 28 (27.72) | |

| Irritated | 12 (11.88) | |

| Accepted as natural process | 6 (5.94) | |

| Knowledge regarding menstruation before menarche | Yes | 48 (47.52) |

| No | 53 (52.48) | |

| Perception about Menstruation | Physiological | 67 (66.8) |

| Pathological | 9 (8.9) | |

| Curse | 21 (20.79) | |

| Don't know | 4 (3.6) | |

| Feeling of embarrassment during menstruation | Yes | 58 (57.4) |

| No | 21 (20.8) | |

| Sometimes | 22 (21.8) | |

| Menstrual blood is releasing from which organ | Urinary bladder | 9 (8.91) |

| Ovary | 15 (14.85) | |

| Uterus | 21 (20.79) | |

| Stomach | 13 (12.87) | |

| Don't know | 43 (42.57) | |

| Duration of menstrual cycle | 26-30 days | 59 (58.41) |

| 30-35 days | 25 (24.75) | |

| Others | 10 (9.90) | |

| Don't know | 7 (6.94) | |

| Normal Flow | 3-5 days | 32 (31.68) |

| 5-7 days | 49 (48.51) | |

| Others | 20 (19.80) | |

| Knowledge about menstrual hygienic practices before menarche | Yes | 29 (28.71) |

| No | 71 (70.29) | |

| Knows that Poor MHM can cause infection | Yes | 33 (32.67) |

| No | 67 (66.37) | |

| Can girls go out/school during menstruation? | Yes | 29 (28.71) |

| No | 72 (71.28) | |

| Can girls cook food during menstruation? | Yes | 12 (11.88) |

| No | 89 (88.11) | |

| Source of knowledge | Mother | 41 (40.59) |

| Sister | 24 (23.76) | |

| Other Female Relatives | 17 (16.83) | |

| Entertainment/Newsmedia | 6 (5.95) | |

| School | 13 (12.87) |

Table 3.

Restroom and related facilities during menstruation (n = 101).

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender-specific restroom facilities in camp | Yes | 8 (7.92) |

| No | 93 (92.8) | |

| Satisfy about toilet facilities in camp | Yes | 36 (35.2) |

| No | 65 (64.8) | |

| Adequate soap & water facilities in toilet | Yes | 23 (22.6) |

| No | 78 (77.4) | |

| Satisfy about privacy in camp's toilet | Yes | 27 (26.5) |

| No | 73 (72.5) |

Table 4 shows that most girls (50.49%, n = 51) were using discarded cloth as absorbent material during menstruation, and 20.79% (n = 21) were using clean homemade pads. Commercial disposable sanitary pads were used as absorbent material among 17.82% (n = 18) of girls. Approximately 48.51% (n = 49) of participants changed absorbents once daily. After use, 30.69% (n = 31) disposed of the absorbent inside the toilet, and 17.82% (n = 18) disposed of it in an open space. If reusing, only 22.77% (n = 23) of girls used soap and water to wash the absorbent, and only 33.67% (n = 34) dried the washed absorbent cloth by hanging them indoors. Approximately 25.74% (n = 26) of respondents washed their hands before and after changing their pads.

Table 4.

Practice & restriction regarding menstruation hygiene management (n = 101).

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of absorbent | Disposable Sanitary Pad | 18 (17.82) |

| Clean Homemade Pad/Cloth | 21 (20.79) | |

| Old Cloth | 51 (50.49) | |

| Only Underwear | 11 (10.89) | |

| Changing of absorbent in a day | Don't change everyday | 3 (2.97) |

| Once | 49 (48.51) | |

| Twice | 21 (20.79) | |

| Thrice | 16 (15.84) | |

| Quarterly | 7 (6.93) | |

| More than quarterly | 5 (4.95) | |

| Disposal of absorbent | Open Space | 18 (17.82) |

| Water source | 4 (3.96) | |

| Toilet | 31 (30.69) | |

| Dustbin | 7 (6.93) | |

| Reuse | 41 (40.59) | |

| Washing hands before and after changing absorbents | Don't wash | 34 (33.66) |

| Only after changing | 41 (40.59) | |

| Washes before and after changing | 26 (25.74) | |

| Materials used to clean reusable absorbent | Soap and water | 23 (22.77) |

| Only water | 16 (15.84) | |

| Others | 2 (1.98) | |

| Dispose | 60 (59.40) | |

| Drying technique | Sun dry | 6 (5.94) |

| Ironing | 4 (3.96) | |

| Hanging indoor | 31 (30.69) | |

| No need to dry | 60 (59.40) | |

| Restrictions | Religious activities | 37 (36.63) |

| Certain food | 10 (9.90) | |

| Drinking Water | 8 (7.92) | |

| Sleeping with all family members | 5 (4.95) | |

| Touching cattles | 6 (5.94) | |

| Eating food with members | 4 (3.96) | |

| Religious activities, certain foods, touching cattles | 19 (18.81) | |

| Religious activities, touching cattles and sleeping with family | 14 (13.86) |

∗Multiple response considered.

Approximately 21% (n = 21) of the girls knew that the uterus was the source of menstrual blood, and 33.67% (n = 34) had knowledge regarding menstrual hygiene management. Overall, 25.75% (n = 26) knew that poor menstrual hygiene management might cause infection (Table 5).

Table 5.

Assessment of level of knowledge and practice regarding Menstrual hygiene.

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Key Parameters in assessing knowledge | ||

| Knowledge about what is menstruation | Yes | 67 (66.34) |

| No | 34 (33.66) | |

| Knows that from which organ menstrual blood comes | Yes | 21 (20.79) |

| No | 80 (79.20) | |

| Knowledge about normal duration of menstrual cycle | Yes | 41 (40.59) |

| No | 60 (59.40) | |

| Knowledge about normal flow of menstruation | Yes | 34 (33.67) |

| No | 67 (66.33) | |

| Knowledge about menstrual hygienic practices | Yes | 29 (28.71) |

| No | 72 (71.28) | |

| Knows that Poor MHM can cause infection | Yes | 26 (25.75) |

| No | 75 (74.25) | |

| Knows exactly how menstruation affect normal day to day life and daily activities are not forbidden | Yes | 29 (28.71) |

| No | 72 (71.28) | |

| Can girls cook food during menstruation? | Yes | 12 (11.88) |

| No | 89 (88.11) | |

| Key Parameters in assessing Practice regarding menstrual hygiene management | ||

| Using clean and sanitary absorbent (disposable or useable) | Yes | 39 (38.61) |

| No | 62 (61.38) | |

| Adequate interval between changing absorbent | Yes | 28 (27.72) |

| No | 73 (72.27) | |

| Adequate Disposal/Reusing of absorbent | Yes | 38 (37.62) |

| No | 63 (62.37) | |

| Washing hands before and after changing absorbents | Yes | 26 (25.74) |

| No | 75 (74.25) | |

| Takes bath daily during menstruation | yes | 38 (37.62) |

| No | 63 (62.37) | |

| Cleaning genitalia after urination | Yes | 42 (41.58) |

| No | 59 (58.41) | |

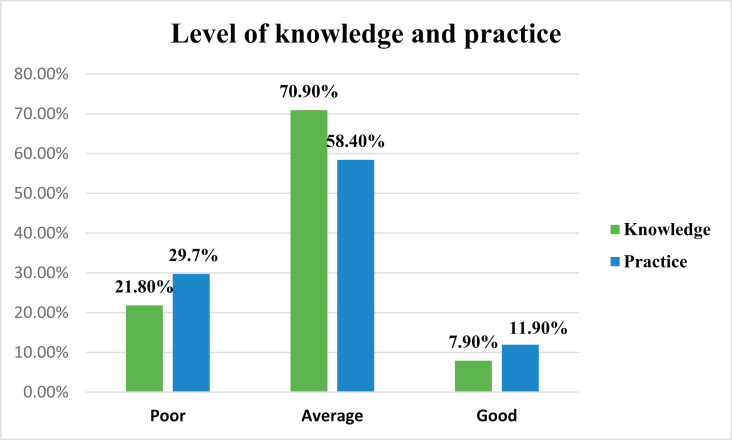

According to the data obtained from the study population (Figure 1), 70.9% (n = 71) of the respondents had average knowledge about menstruation and hygiene, 21.80% (n = 22) had poor knowledge, and 7.90% (n = 8) had good knowledge. The classification of the knowledge level of each respondent was made on the basis of the calculated knowledge score (Table 3). The range for the level of knowledge was classified and estimated using the formula Mean + 1 S. D at a 90% Confidence Interval. According to this value, any respondents who scored 3–7 were classified as having “average knowledge”, and those below score 3 were classified as having “poor knowledge”; likewise, the respondents with a value greater than seven were classified as having “good knowledge”. The classification of the practice level of each respondent was made on the basis of the practice score calculated (Table 4). The range for the level of practice was also classified and estimated using the formula Mean ± S. D at 90% confidence intervals. According to this value, any respondents who scored 2 to 6 were classified under having “Average Practice”, and those who scored below the score were 2 with “Poor Practice.” Likewise, the respondents with a value of more than 6 were classified as “Good Practice”. Out of the total respondents, 58.40 % (n = 59) of the respondents had an average practice of menstrual hygiene (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Level of knowledge and practice regarding menstruation and menstruation hygiene management (n = 101).

3.2. Qualitative analysis

3.2.1. Changes in menstrual hygiene practices among girls and women after displacement

Sanitary materials (e.g., disposable pads, reusable pads, cloths, etc.) used by displaced girls to manage monthly menstrual flow tended to change after displacement. Many girls reported that while living in Myanmar, they used disposable sanitary pads, reusable clothes, and other supportive materials, such as underwear and soap, in accordance with personal preferences and convenience. However, after the displacement, many girls reported being reliant on only distributions of sanitary materials. The frequency of distribution, availability, and affordability were found to influence the types of absorbents used. Distributions were at best monthly, but in reality they typically occurred every 2–3 months or biannually depending on the organization responsible for the given camp.

As one adolescent girl explained,

“When I have [disposable] pads, I will go outside, but when I only have cloth, I can’t go out and feel uncomfortable. However, I don’t have enough disposable sanitary pads, that’s why I have to wear old cloths for the maximum time. For going outside, I use a disposable sanitary pad, but for home, I use cloth. When I get a disposable sanitary pad from NGO, I will be very much happy.”

3.2.2. Inadequate wash facilities and safe, private spaces for changing menstrual materials and disposal

In the Rohingya camp, adolescent girls described challenges in finding spaces where they can change their menstrual material safely and privately, clean themselves and dispose of their menstrual waste. Their latrines were described as unsafe, uncomfortable, and dirty. In some latrines, there remain significant gaps in the walls, permitting visibility from the outside, and there is an absence of locks on the doors. That is why many girls experience anxiety regarding the potential for “peeping toms” or intruders while using these facilities. They often cannot take advantage of nighttime use of the latrines due to inadequate lighting on pathways and in toilet stalls, fear of general violence or sexual violence. Many girls and women opted to wake up very early (4 or 5 am) to use latrines without any disturbance. Some of the Rohingya girls indicated extreme discomfort while changing their menstrual materials even inside their shelter homes, as the walls were made up of tin or plastic sheeting. There was not enough space for washing, drying the cloths and disposing of sanitary materials; they would often resort to drying them in the home or under their clothes, which is not hygienic. As the camp is very crowded and congested, cloths are often kept in dirty places. Some households developed makeshift household toilets, sanitary bins or hygienic spaces for the disposal of sanitary material, however, these are reportedly insufficient. Most of the girls reported that they threw the materials in the toilet, which might cause water clogging. Some of them burned the used pads/materials. Many of the respondents described carrying dark-colored plastic bags for discreetly holding the used materials to later dispose of in the household trash.

One displaced girl explained:

‘The houses are too small and don't allow for privacy. It is one room for the entire family. The size of the house and the lack of separation from the men and boys is a problem. We have to hide the damp menstrual cloths underneath existing clothing or mattresses to dry. We cannot wash the cloth with soap most of the time due to a lack of soap and safe water. We feel discomfort about drying the cloth, and when we use the damp used cloth, it causes irritation, discomfort, sometimes causes itching, rashes, burning sensation in urinary tract.’

3.2.3. Social constraints and premenstrual knowledge

Among the Rohingya girls, one tenth of the participants responded that it happened due to pathological cause, and one fifth of the participants thought it was a curse from God to them. They faced many social restrictions in daily activities during menstruation.

One adolescent Rohingya girl explained,

‘My mother and grandmother forbid me and ask me to stay away from the day-to-day activities. I am not allowed to drink too much water and not to eat sour types of food. I have to sleep far from our family members, and I don't like it. I feel disgusted about menstruation. When I am at home, I don't go to school at that period.’

In an emergency crisis, lack of health education from school, media, or even from family leads girls to experience menarche without any mental or logistical preparation. In the camp, many girls reported that they did not have any knowledge regarding menstruation before experiencing it. When they faced it for the first time, they felt distressed and embarrassed at the onset of bleeding. The majority of adolescent girls reported that they did not receive any education on menstruation, the process, the cycle, or how it pertains to their reproductive health during their time in the camps or predisplacement.

4. Discussion

During puberty, hormonal, psychological, cognitive, and physical changes coincide and create a challenge for adolescents, who have to face emotional, social, and behavioral dimensions. These challenges are accompanied by the added pressure of cultural expectations, traditional values, and beliefs throughout their lives. In this subcontinent, most adolescent girls enter womanhood unprepared, and the information they receive is often very selective and surrounded by taboos. During emergency crises, even fundamental facts about menstruation and reproductive health receive little attention. Therefore, a girl's attitude and expectations about menstruation become even more challenging.

The present study observed a lack of gender segregation of toilet facilities, shame, and a misconception regarding menstruation, making the girls in refugee camps very uncomfortable. Infrequent distributions of laundry soap and absorbents such as disposable sanitary napkins created further challenges for girls to maintain good MHM practices. Good menstrual hygienic practices include sanitary pads/other clean material such as cloths/tampons/cup and adequate washing of the genital areas, which is essential during the menstruation period. Women and girls of reproductive age need access to clean and soft absorbent sanitary products, which in the long run protect their health from various infections. One-tenth of the study participants revealed that they were maintaining a good practice level of menstruation hygiene management, while the rest of them were seem to be maintaining a poor or average practice level. Approximately half of the adolescent girls reported using old cloths as an absorbent during menstruation. Among those who were reusing the materials, some were using soap for washing, some were not, and most were drying the cloth by hanging them inside the home, which is unhygienic and unhealthy. The girls and women in this study were interested in using disposable pads due to the privacy and logistical challenges surrounding washing and drying reusable materials, such as cloth. During an emergency crisis, women's choices and the options of menstrual-related materials and menstrual practices were altered. The supply of sanitary napkins was reported to be infrequent and not meeting demand. Lack of privacy was reported as a major constraint on maintaining menstrual hygiene. Nearly half of them were changing absorbents only once daily and throwing the used material inside the toilet or open space. The disposal system of the camp was very limited. However, keeping a bin inside toilets also tended to be restricted due to strong cultural taboos and potential humiliation.

Menstruation is a very complex physiological process involving different hormones, genital organs, and the nervous system. A healthy lifestyle and positive mental attitude are very much needed to manage with this change. However, social taboos and stigma make it an awkward subject to talk about, especially with preteen girls. In the present study, more than half of the girls knew that menstruation is a physiological process, but only one-fifth of them knew the source of menstrual blood. Less than half of the participating girls had adequate knowledge regarding the flow and duration of the cycle. Numerous similar studies have been conducted nationally and internationally on the knowledge and perception regarding menstrual hygiene [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]]. The present study revealed that 70.90% had average knowledge about menstrual hygiene. The issue of menstruation is ignored or misunderstood mainly due to ignorance, taboos and misconceptions, and sociocultural factors that prevent women from articulating their needs. The implications of ignoring this issue are severe and, at times, possibly life-threatening. Shannon et al. conducted a study in Kenya and observed that young girls are not usually taught how to manage their menstruation, especially before menarche when they have no knowledge, which is a monthly aspect of their lives and has a tremendous impact on the ways a girl views herself and her roles within society [29]. After menarche, more than half of the girls were found to be scared. Less than half of the girls had premenstrual knowledge. A study in Bangladesh showed that most girls did not know about menstruation before menarche [23]. The study revealed that mothers were the major source of information for primary knowledge related to menstruation. A study by Shaheen Akhter in Bangladesh found that overall, women gained knowledge about menstruation mostly from mothers and sisters, which is in alignment with the present study [24]. Similarly, mothers were found to be the primary source of information regarding menstruation studies conducted in Rajsthan by Khanna et al. and Thakre S et al. from Nagpur, which corresponds with the present study [25, 26]. Lack of awareness leads to poor and corrupted knowledge, which results in a confusing, frightening, and shame-inducing experience and may be followed by stress, fear, embarrassment, and social exclusion during menstruation. A similar study by Mahajan and Kaushal revealed that 29% had adequate knowledge about menstrual hygiene, and 71% had inadequate knowledge about menstrual hygiene [30]. In an emergency crisis, adolescent girls did not have the opportunity to learn or to obtain any education relevant to MH. There are some schools in camps, but their purpose was mainly to provide primary education. Here, ‘menstrual hygiene management’ type topics are not included. Mothers were surrounded by severe stigma and taboos when discussing these topics freely with them. Thus, girls have remained far from any knowledge from the media, internet, TV, radio, etc. They must face the situation without proper knowledge or facilities. Most of the respondents stated that they were restricted from eating certain foods, mainly sour foods, drinking plenty of water, cooking or attending social gatherings during their menstrual cycles.

5. Conclusion

Among the Rohingya adolescent girls, one-fourth had premenstrual knowledge at various levels. Diverse materials were used in addition to disposable sanitary pads. Adequate facilities for changing and disposing of sanitary materials are sparse. Limited supportive environments, family and cultural beliefs, stigma, restrictions, and fear of sexual violence were identified as constraints on appropriate practices.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Kashfi Pandit: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Mohammad Jahid Hasan and Tazul Islam: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Tareq Mahmud Rakib: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the “Pi Research Consultancy Center (www.pircc.org) for data analysis and other formatting support. Additionally, we thank all respondents who gave their valuable time and opinion on these stressful topics.

References

- 1.Wali N., Chen W., Rawal L.B., et al. Integrating human rights approaches into public health practices and policies to address health needs amongst Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh: a systematic review and meta-ethnographic analysis. Arch. Publ. Health. 2018;76:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13690-018-0305-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khatun F. Implications of the Rohingya crisis for Bangladesh at the dialogue on " addressing Rohingya crisis: options for Bangladesh & quot. Addressing Rohingya cris options Bangladesh. http://cpd.org.bd/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Presentation-on-Implications-of-the-Rohingya-Crisis-for-Bangladesh.pdf

- 3.JRP for Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis. 2018. www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/bangladesh/document/jrp-rohingya-humanitarian-crisis [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Organization for Migration (IOM) 2018. Needs and Population Monitoring (NPM) Bangladesh Round 11 Site Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh: health sector bulletin No.1. Heal Sect. Bull..

- 6.Ahmed R., Farnaz N., Aktar B., et al. Situation analysis for delivering integrated comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services in humanitarian crisis condition for Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh: protocol for a mixed-method study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO . 2019. Rohingya Crisis in Cox’s Bazar District, Bangladesh: Health Sector Bulletin.http://www.searo.who.int/bangladesh/health-sector-cxb-bangladesh-no9.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wake C., Bryant J. 2018. Capacity and Complementarity in the Rohingya Response in Bangladesh.https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12554.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crisis Rohingya, Cox’s Bazar B.H.S.B. 2018. Health Sector Coordination Team.http://www.searo.who.int/bangladesh/healthsectorcxbbanbulletinno4.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee S. The Rohingya crisis: a health situation analysis of refugee camps in Bangladesh. Obs. Res. Found. 2019;91:298–310. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommer M. Menstrual hygiene management in humanitarian emergencies: gaps and recommendations. Waterlines. 2012;31:83–104. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bastable A, Russell L. Gap Analysis in Emergency Water, Sanitation and hygiene Promotion. London: Humanitarian Innovation Fund.

- 13.Parker A., Smith J.A., Verdemato T., Cooke J., Webster J.C.R. Menstrual management: a neglected aspect of hygiene interventions. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2014;23:437–454. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden T. Menstrual hygiene management in emergencies: taking stock of support from UNICEF and partners. N. Y. City UNICEF. 2012;1–30 [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Menstrual hygiene: what’s the fuss? Piloting menstrual hygiene management (MHM) kits for emergencies in Bwagiriza refugee camp, Burundi. Soc. Gen. Int. Fed. Red. Cross Red. Crescent.

- 16.Fisher S. Violence against women and natural disasters: findings from post-tsunami Sri Lanka. Violence Against Women. 2010;16:902–918. doi: 10.1177/1077801210377649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oxfam . 2018. One Year on Time to Put Women and Girls at the Heart of the Rohingya Response.https://www.oxfamamerica.org/static/media/files/bp-one-year-on-rohingya-refugee-women-girls-110918-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yadav R.N., Joshi S., Poudel R., et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice on menstrual hygiene management among school adolescents. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2018;15:212–216. doi: 10.3126/jnhrc.v15i3.18842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand. J. Publ. Health. 2012;40:795–805. doi: 10.1177/1403494812465030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sapkota D., Sharma D., Budhathoki S., et al. school-going adolescents of rural Nepal. J. Kathmandu Med. Coll. 2013;2:122–128. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chowdhury M.A.K., Billah S.K., Khan F., et al. 2018. Report on Demographic Profiling and Needs Assessment of Mternal Child Health (MCH) Care for the Rohigya Refugee Population in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.http://dspace.icddrb.org/jspui/handle/123456789/9067 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muhit I.B., Chowdhury S.T. Vol. 2. 2013. Menstrual hygiene condition of adolescent schoolgirls at Chittagong division in Bangladesh; pp. 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akhter S. Vol. 12. 2006. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices on Reproductive Health and Rights of Urban and Rural Women in Bangladesh; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taker S.B., Thakre S.S., Reddy M. Menstrual hygiene Knowledge and practice among adolescents school girls of Saoner,Nagpur District. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2011;5:1027–1033. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanna A., Goyal R.S., Bhawsar R. Menstrual practices and reproductive problems: a study of adolescent girls in Rajasthan. J. Health Manag. 2005;7:91–107. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali T.S., Rizvi S.N. Menstrual knowledge and practices of female adolescents in urban Karachi,Pakistan. J. Adolesc. 2010;33:531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tiwari H., Oza U.N., Tiwari R. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about menarche of adolescent girls in Anand district, Gujarat. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2006;12:428–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMahon S.A., Winch P.J., Caruso B.A., et al. The girl with her period is the one to hang her head’ Reflections on menstrual management among schoolgirls in rural Kenya. BMC Int. Health Hum. Right. 2011;11:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahajan A., Kaushal K. A descriptive study to assess the knowledge and practice regarding menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls of Government School of Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. CHRISMED J. Health Res. 2017;4:99. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.