Abstract

Chronic medical conditions are increasingly common and associated with a high burden for persons affected by them. Digital health interventions might be a viable way to support persons with a chronic illness in their coping and self-management. The present special issue's editorial on digital health interventions in chronic medical conditions summarizes core findings and discusses next steps needed to further the field while avoiding to reinvent the wheel, thereby elaborating on four topics extracted from the special issue's articles: 1) Needs assessment and digital intervention development, 2) Efficacy and (cost-)effectiveness, 3) Dissemination and implementation research: reach and engagement as well as 4) next generation of digital interventions.

Keywords: Digital health interventions, Chronic medical diseases, Diabetes, Cancer, Pain, Heart disease

Chronic medical conditions such as coronary heart disease, cancer, diabetes, asthma and arthritis are increasingly common and associated with a high burden for persons affected by them. As noted by Corbin and Strauss (1985), managing a chronic illness involves ‘three lines of work’: illness work, everyday life work, and biographical work. Persons with chronic medical conditions are confronted with a multitude of disease (self-)management challenges such as adhering to complex and often ambivalent treatment plans over a long period of time, coping with symptoms, functional limitations and treatment side-effects, as well as dealing with social issues (e.g. stigma, role functioning) and an increased risk for mental health problems such as depression and anxiety (Härter et al., 2007; Petrie and Jones, 2019).

Digital health interventions might be a viable way to support persons with a chronic illness in their coping and self-management and achieve optimal health outcomes, both medical and psychological (Bendig et al., 2018). Moreover, such approaches allow not only to be tailored to the specific characteristics of individuals with medical conditions, but also to be attuned to the needs of persons at different stages of the disease trajectory, e.g. (co)-treatment, after-care and palliative care. While there is already substantial evidence in the area of digital interventions in the field of mental health, there is still much to learn about the needs and best way of providing digital interventions for people with medical conditions (Ebert et al., 2018).

The present special issue provides a series of fourteen studies in medical conditions, the majority of which can be classified as in the early translational research stage of needs assessment and intervention development (Blaney et al., 2021; Bonnert et al., 2021; Carolan-Olah et al., 2021; Geirhos et al., 2021; Mellergård et al., 2021; Muijs et al., 2021; Nap-van der Vlist et al., 2021; Verkleij et al., 2021). A few studies report on the efficacy and effectiveness of digital interventions (Bendig et al., 2021; Domhardt et al., 2021b; Terhorst et al., 2021; Terpstra et al., 2021; van der Hout et al., 2021), while two studies focus on the next development stage of digital interventions, aiming for personalisation and adaptiveness (Harnas et al., 2021; Nap-van der Vlist et al., 2021). The studies target a broad range of chronic medical conditions, including diabetes (Geirhos et al., 2021; Mellergård et al., 2021; Muijs et al., 2021), cancer (Harnas et al., 2021; Nap-van der Vlist et al., 2021; van der Hout et al., 2021), arthritis and pain (Blaney et al., 2021; Geirhos et al., 2021; Terhorst et al., 2021; Terpstra et al., 2021), cystic fibrosis (Geirhos et al., 2021; Nap-van der Vlist et al., 2021; Verkleij et al., 2021), asthma (Bonnert et al., 2021) and coronary artery disease (Bendig et al., 2021) as well as chronic medical conditions in general (Domhardt et al., 2021b) in adults as well as youth (Domhardt et al., 2021b; Geirhos et al., 2021; Nap-van der Vlist et al., 2021).

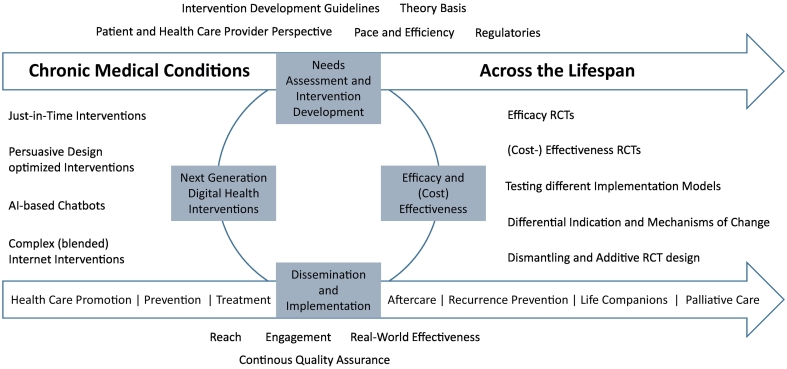

This special issue provides us the opportunity to reflect on the current status of digital health in medical conditions in the broader context of digital interventions and identify the next steps needed to further the field while avoiding to reinvent the wheel, with four extracted interdependent categories (Fig. 1):

-

1.

Needs Assessment and Digital Intervention Development

-

2.

Efficacy and (Cost-)Effectiveness

-

3.

Dissemination and Implementation Research: Reach and Engagement

-

4.

Next Generation of Digital Interventions

Fig. 1.

Digital health interventions in people with chronic medical conditions.

1. Needs assessment and digital intervention development

The substantial number of papers on need assessment and intervention development in this special issue appears indicative for the field of digital health interventions in people with chronic medical conditions being still in its early stage. While there are clearly overarching psycho-social themes across diseases, it is important to identify the specific needs, challenges and preferences of specific patient groups as they may vary across conditions and severity stage of disease. For example people with diabetes mellitus (Geirhos et al., 2021; Mellergård et al., 2021) might be particularly interested in interventions supporting their long-term daily struggle, while those with a progressive condition or in palliative care phase (Capurro et al., 2014; Verkleij et al., 2021) may have a demand for meaning-centered interventions, related to coping with limited life-expectancy, dying or struggling with the help- and hopelessness in a not yet always very supportive, personalised health care system. As exemplified by Carolan-Olah et al. (2021), interventions should also be attuned to the demands and preferences of the target population, in socio-demographic and cultural terms, next to the disease-specific needs. Interventions are to be optimized for people with a medical condition with a migration background, low socioeconomic status and different educational levels. In this context, it seems recommendable to build interventions on existing knowledge gathered in the past two decades of digital intervention development, that have led to intervention development guidelines and recommendations from both a clinical and a technological perspective (Edwards-Stewart et al., 2019; Holfelder et al., 2021; Karekla et al., 2019; Michie et al., 2017).

2. Efficacy and (cost-)effectiveness

Once needs are assessed and the interventions developed, they usually pass the translational process of clinical testing with feasibility and pilot trials followed by efficacy and (cost-)effectiveness trials. A few aspects warrant special attention in order to make a difference in the field of digital interventions for people with chronic medical conditions. First, interventions might not work the same across disease conditions and at different stages of the disease and treatment. As one example, Bendig et al. (2021) reported on a failed trial examining an intervention for depression in people with coronary artery disease, while we do know that this kind of intervention can work e.g. for people with diabetes (Nobis et al., 2018; Nobis et al., 2015; van Bastelaar et al., 2008). However, two other trials, one on the prevention of depression in patients with back pain (Sander et al., 2020) and one on the treatment of depression in patients with back pain (Baumeister et al., 2021), using almost the same intervention highlighted that we still need to take a closer look at what works for whom at which stage of disease. While the prevention trial, targeting individuals with chronic pain and subclinical symptoms of depression, resulted in a more than impressive hazard ratio of 0.48, i.e. onset of depression was halved within a period of twelve months (Sander et al., 2020), the treatment trial, including only people with a diagnosed Major Depression Disorder, provided a null-finding, at least for the primary outcome (Baumeister et al., 2021), despite the fact that the efficacy of digital depression interventions in the general population is well established (Königbauer et al., 2017). This finding also supports the assumption that evidence generated in the general population can not necessarily be simply generalized to chronic medical populations.

Thus, digital interventions for depression in chronic medical conditions can work and make a difference, but we cannot assume they work for all people at any stage of disease with any intervention, regardless of the specific active components and technological approaches. More research is warranted to deepen our understanding of the differential effectiveness of interventions by means of moderator analyses as estimator for personalised intervention provision as well as studies on the active components and the mechanisms of change (Breitborde et al., 2010). As one example, it has been shown that people with chronic pain are more likely to benefit from an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) based pain intervention in case of initially lower psychological flexibility (Probst et al., 2018), and psychological flexibility has been verified as mechanism of change (Lin et al., 2018). Improving our knowledge on the moderators, causal factors and mechanisms of change can iteratively inform future intervention development to optimize (digital) health care (Domhardt et al., 2021a).

3. Dissemination and implementation research: reach and engagement

Dissemination and implementation research should accompany our efforts to inform health care policy about the effectiveness and potential of digital interventions in real world settings (Etzelmueller et al., 2020; Gaebel et al., 2021; Titov et al., 2018). A main challenge in this context is reach, i.e. reaching the target population at large and facilitating acceptance towards digital health interventions (Baumeister et al., 2014; Baumeister et al., 2015; Baumeister et al., 2020), as well as reaching those not yet well covered by our health care systems, thereby aiming to reduce health care disparities (Wasserman et al., 2019). A second topic of interest is engagement, i.e. scientific evidence on how digital health interventions are used in real word settings outside the research context. Fleming et al. (2018) highlighted that completion or sustained use of self-help interventions for depression, low mood or anxiety provided in real-world was only registered for 0.5% to 28.6% of health intervention users. Similarly, Baumel et al. (2019) calculated that there is a research bias regarding engagement estimates with intervention usage being four times higher in trials compared with the same interventions in real-world. Therefore, the report by van der Hout et al. (2021) in this special issue on reasons for not reaching or engaging cancer patients regarding the provided digital intervention is of utmost relevance, underscoring the need to better understand ways of implementing evidence based health care delivery models.

4. Next generation of digital health interventions

Information from the translational process of developing and evaluating digital health interventions for people with chronic medical conditions can help to further improve interventions, thereby taking the rapid technological innovation cycle into account. Next generation digital health interventions for people with chronic medical conditions will not only be informed by formative feedback from studies alongside the translational process, but also by intervention designs aiming to provide personalised and adaptive interventions such as Just-in-time-adaptive interventions (i.e. personalised interventions provided at a moment of opportunity; (Nahum-Shani et al., 2017)) or AI-based medical and psychotherapeutic chatbots (Bendig et al., 2019; Pryss et al., 2019). Similarly, next generation digital health interventions can and should build more thoroughly on persuasive design principles in order to improve intervention engagement - one of the well-established barriers to successful intervention designs (Baumeister et al., 2019). The complexity of this kind of technologically enhanced interventions is nicely illustrated by Harnas et al. (2021) in this special issue, who provide a case report series on personalizing cognitive behavioural therapy for cancer-related fatigue by means of ecological momentary assessments. Another challenge is the development of digital interventions fit for people with medical conditions as integral part of often complex health care services models and disease management programs.

5. Conclusion

The present special issue clearly illustrates the potential as well the challenges that we face on the road to exploit the full potential of digital intervention for people with a chronic medical condition. We commend the many colleagues who have contributed to this special issue and provided much needed evidence to add to this developing field of research. We hope it will stimulate future research within and across medical conditions to provide answers on how digital interventions can make a difference to help improve the lives of people with chronic medical conditions – within and beyond established health care services.

References

- Baumeister H., Nowoczin L., Lin J., Seifferth H., Seufert J., Laubner K., Ebert D.D. Impact of an acceptance facilitating intervention on diabetes patients’ acceptance of Internet-based interventions for depression: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014:105. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.04.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister H., Seifferth H., Lin J., Nowoczin L., Luking M., Ebert D. Impact of an acceptance facilitating intervention on patients’ acceptance of Internet-based pain interventions: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. J. Pain. 2015;31:528–535. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000118PM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister H., Kraft R., Baumel A., Pryss R., Messner E.-M. 2019. Persuasive e-Health Design for Behavior Change; pp. 261–276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister H., Terhorst Y., Grässle C., Freudenstein M., Nübling R., Ebert D.D. Impact of an acceptance facilitating intervention on psychotherapists’ acceptance of blended therapy. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister H., Paganini S., Sander L.B., Lin J., Schlicker S., Terhorst Y., Moshagen M., Bengel J., Lehr D., Ebert D.D. Effectiveness of a guided Internet- and Mobile-based intervention for patients with chronic back pain and depression (WARD-BP): a multicenter, pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2021;90:255–268. doi: 10.1159/000511881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumel A., Edan S., Kane J.M. Is there a trial bias impacting user engagement with unguided e-mental health interventions? A systematic comparison of published reports and real-world usage of the same programs. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019;9:1020–1033. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendig E., Bauereiß N., Ebert D.D., Snoek F., Andersson G., Baumeister H. Internet- and mobile based psychological interventions in people with chronic medical conditions. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Int. 2018;115:659–665. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bendig E., Erb B., Schulze-Thuesing L., Baumeister H. Next generation: chatbots in clinical psychology and psychotherapy to foster mental health – a scoping review. Verhaltenstherapie. 2019:1–15. doi: 10.1159/000499492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bendig E., Bauereiß N., Buntrock C., Habibović M., Ebert D.D., Baumeister H. Lessons learned from an attempted randomized-controlled feasibility trial on “WIDeCAD” - an internet-based depression treatment for people living with coronary artery disease (CAD) Internet Interv. 2021;24:100375. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney C., Hitchon C.A., Marrie R.A., Mackenzie C., Holens P., El-Gabalawy R. Support for a non-therapist assisted, Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (iCBT) intervention for mental health in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Internet Interv. 2021;24:100385. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnert M., Särnholm J., Andersson E., Bergström S.E., Lalouni M., Lundholm C., Serlachius E., Almqvist C. Targeting excessive avoidance behavior to reduce anxiety related to asthma: a feasibility study of an exposure-based treatment delivered online. Internet Interv. 2021;25:100415. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitborde N.J.K., Srihari V.H., Pollard J.M., Addington D.N., Woods S.W. Mediators and moderators in early intervention research. Early Interv. Psychiatry. 2010;4:143–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capurro D., Ganzinger M., Perez-Lu J., Knaup P. Effectiveness of ehealth interventions and information needs in palliative care: a systematic literature review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16 doi: 10.2196/jmir.2812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carolan-Olah M., Vasilevski V., Nagle C., Stepto N. Overview of a new eHealth intervention to promote healthy eating and exercise in pregnancy: initial user responses and acceptability. Internet Interv. 2021;25:100393. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., Strauss A. Managing chronic illness at home: three lines of work. Qual. Sociol. 1985;8:224–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00989485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domhardt M., Cuijpers P., Ebert D.D., Baumeister H. More light? Opportunities and pitfalls in digitalized psychotherapy process research. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.544129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domhardt M., Schröder A., Geirhos A., Steubl L., Baumeister H. Efficacy of digital health interventions in youth with chronic medical conditions: a meta-analysis. Internet Interv. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Van Daele T., Nordgreen T., Karekla M., Compare A., Zarbo C., Brugnera A., Øverland S., Trebbi G., Jensen K.L., Kaehlke F., Baumeister H. Internet-and mobile-based psychological interventions: applications, efficacy, and potential for improving mental health. A report of the EFPA E-Health Taskforce. Eur. Psychol. 2018;23:167–187. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards-Stewart A., Alexander C., Armstrong C.M., Hoyt T., O’Donohue W. Mobile applications for client use: ethical and legal considerations. Psychol. Serv. 2019;16:281–285. doi: 10.1037/ser0000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzelmueller A., Vis C., Karyotaki E., Baumeister H., Titov N., Berking M., Cuijpers P., Riper H., Ebert D.D. Effects of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in routine care for adults in treatment for depression and anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020 doi: 10.2196/18100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T., Bavin L., Lucassen M., Stasiak K., Hopkins S., Merry S. Beyond the trial: systematic review of real-world uptake and engagement with digital self-help interventions for depression, low mood, or anxiety. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20 doi: 10.2196/jmir.9275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebel W., Lukies R., Kerst A., Stricker J., Zielasek J., Diekmann S., Trost N., Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E., Bonroy B., Cullen K., Desie K., Ewalds Mulliez A.P., Gerlinger G., Günther K., Hiemstra H.J., McDaid S., Murphy C., Sander J., Sebbane D., Roelandt J.L., Thorpe L., Topolska D., Van Assche E., Van Daele T., Van den Broeck L., Versluis C., Vlijter O. Upscaling e-mental health in Europe: a six-country qualitative analysis and policy recommendations from the eMEN project. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021;271:1005–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01133-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geirhos A., Lunkenheimer F., Holl R.W., Minden K., Schmitt A., Temming S., Baumeister H., Domhardt M. Involving patients’ perspective in the development of an internet- and mobile-based CBT intervention for adolescents with chronic medical conditions: findings from a qualitative study. Internet Interv. 2021;24:100383. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnas S.J., Knoop H., Booij S.H., Braamse A.M.J. Personalizing cognitive behavioral therapy for cancer-related fatigue using ecological momentary assessments followed by automated individual time series analyses: a case report series. Internet Interv. 2021;25:100430. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härter M., Baumeister H., Reuter K., Jacobi F., Höfler M., Bengel J., Wittchen H.-U. Increased 12-month prevalence rates of mental disorders in patients with chronic somatic diseases. Psychother. Psychosom. 2007;76 doi: 10.1159/000107563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holfelder M., Mulansky L., Schlee W., Baumeister H., Schobel J., Greger H., Hoff A., Pryss R. Medical device regulation efforts for mHealth apps during the COVID-19 pandemic - an experience report of Corona Check and Corona Health. J. 2021;4:206–222. doi: 10.3390/j4020017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karekla M., Kasinopoulos O., Dias Neto D., Ebert D.D., Van Daele T., Nordgreen T., Höfer S., Oeverland S., Jensen K.L. Special issue: adjustment to chronic illness original articles and reviews. Best practices and recommendations for digital interventions to improve engagement and adherence in chronic illness sufferers. Eur. Psychol. 2019;24:49–67. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Königbauer J., Letsch J., Doebler P., Ebert D., Baumeister H. Internet- and mobile-based depression interventions for people with diagnosed depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Klatt L.-I., McCracken L.M., Baumeister H. Psychological flexibility mediates the effect of an online-based acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: an investigation of change processes. Pain. 2018;159:663–672. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellergård E., Johnsson P., Eek F. Developing a web-based support using self-affirmation to motivate lifestyle changes in type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study assessing patient perspectives on self-management and views on a digital lifestyle intervention. Internet Interv. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S., Yardley L., West R., Patrick K., Greaves F. Developing and evaluating digital interventions to promote behavior change in health and health care: recommendations resulting from an international workshop. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017 doi: 10.2196/jmir.7126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muijs L.T., de Wit M., Knoop H., Snoek F.J. Feasibility and user experience of the unguided web-based self-help app ‘MyDiaMate’ aimed to prevent and reduce psychological distress and fatigue in adults with diabetes. Internet Interv. 2021;25:100414. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahum-Shani I., Smith S.N., Spring B.J., Collins L.M., Witkiewitz K., Tewari A., Murphy S.A. Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017;52:446–462. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9830-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nap-van der Vlist M.M., Houtveen J., Dalmeijer G.W., Grootenhuis M.A., van der Ent C.K., van Grotel M., Swart J.F., van Montfrans J.M., van de Putte E.M., Nijhof S.L. Internet and smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment and personalized advice (PROfeel) in adolescents with chronic conditions: a feasibility study. Internet Interv. 2021;25:100395. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobis S., Lehr D., Ebert D.D., Baumeister H., Snoek F., Riper H., Berking M. Efficacy of a web-based intervention with mobile phone support in treating depressive symptoms in adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:776–783. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1728PM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobis S., Ebert D.D., Lehr D., Smit F., Buntrock C., Berking M., Baumeister H., Snoek F., Funk B., Riper H. Web-based intervention for depressive symptoms in adults with types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus: a health economic evaluation. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2018;212 doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie K.J., Jones A.S.K. Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine. Third edition. 2019. Coping with chronic illness; pp. 110–113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Probst T., Baumeister H., McCracken L., Lin J. Baseline psychological inflexibility moderates the outcome pain interference in a randomized controlled trial on Internet-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic pain. J. Clin. Med. 2018;8:24. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pryss R., Kraft R., Baumeister H., Winkler J., Probst T., Reichert M., Langguth B., Spiliopoulou M., Schlee W. 2019. Using Chatbots to Support Medical and Psychological Treatment Procedures: Challenges, Opportunities, Technologies, Reference Architecture; pp. 249–260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sander L.B., Paganini S., Terhorst Y., Schlicker S., Lin J., Spanhel K., Buntrock C., Ebert D.D., Baumeister H. Effectiveness of a guided web-based self-help intervention to prevent depression in patients with persistent back pain: the PROD-BP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terhorst Y., Messner E.M., Schultchen D., Paganini S., Portenhauser A., Eder A.S., Bauer M., Papenhoff M., Baumeister H., Sander L.B. Systematic evaluation of content and quality of English and German pain apps in European app stores. Internet Interv. 2021;24:100376. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra J.A., van der Vaart R., Ding H.J., Klppenburg M., Evers A.W. Guided Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with rheumatic conditions: a systematic review. Internet Interv. 2021;26 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B., Nielssen O., Staples L., Hadjistavropoulos H., Nugent M., Adlam K., Nordgreen T., Bruvik K.H., Hovland A., Repål A., Mathiasen K., Kraepelien M., Blom K., Svanborg C., Lindefors N., Kaldo V. ICBT in routine care: a descriptive analysis of successful clinics in five countries. Internet Interv. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Bastelaar K.M., Pouwer F., Cuijpers P., Twisk J.W., Snoek F.J. Web-based cognitive behavioural therapy (W-CBT) for diabetes patients with co-morbid depression: design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hout A., van Uden-Kraan C.F., Holtmaat K., Jansen F., Lissenberg-Witte B.I., Nieuwenhuijzen G.A.P., Hardillo J.A., Baatenburg de Jong R.J., Tiren-Verbeet N.L., Sommeijer D.W., de Heer K., Schaar C.G., Sedee R.J.E., Bosscha K., van den Brekel M.W.M., Petersen J.F., Westerman M., Honings J., Takes R.P., Houtenbos I., van den Broek W.T., de Bree R., Jansen P., Eerenstein S.E.J., Leemans C.R., Zijlstra J.M., Cuijpers P., van de Poll-Franse L.V., Verdonck-de Leeuw I.M. Reasons for not reaching or using web-based self-management applications, and the use and evaluation of Oncokompas among cancer survivors, in the context of a randomised controlled trial. Internet Interv. 2021;25:100429. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkleij M., Georgiopoulos A.M., Friedman D. Development and evaluation of an internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for anxiety and depression in adults with cystic fibrosis (eHealth CF-CBT): an international collaboration. Internet Interv. 2021;24:100372. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman J., Palmer R.C., Gomez M.M., Berzon R., Ibrahim S.A., Ayanian J.Z. Advancing health services research to eliminate health care disparities. Am. J. Public Health. 2019;109:S64–S69. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]