Abstract

With the aim of verifying the optical properties of the systems formed by poly(3-methylthiophene) (P3MT) and poly(3-octylthiophene) (P3OT) on platinum (Pt) for use in organic photovoltaic device applications, electrochemical preparations of different interfaces with poly(3-alkylthiophenes) (P3ATs), synthesized both with 18 °C and without temperature control, were compared. These interfaces were prepared both as blends (Pt/P3MT:P3OT) and as layered films (Pt/P3MT/P3OT and Pt/P3OT/P3MT). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was used to characterize the systems, and based on Bode-Phase diagrams, it was possible to monitor the stabilization of radical cation and dication segments of the thiophene ring. The findings corroborated previous studies by electrochemical spectroscopy and using in situ Raman spectroscopy under the same experimental conditions. We were able to verify the effects of experimental variables, such as synthesis temperature and different kinds of deposition. Temperature was found to be an extremely important factor in synthesis, since films synthesized at 18 °C favored the stabilization of radical cation segments in the polymer matrix, and layered deposition also favored the stabilization of these segments, since the layer closest to the electrode can act as an induction layer for the stability of radical cation segments in the system. Photoluminescence spectroscopy was used to verify the optical properties of the interfaces, in which occur the contributions of three segments in the P3ATs matrix. Thus, it has been demonstrated through photoluminescence decay time that the relative amount of radical cation and dication segments in the polymer matrix affects the lifetime of these segments in the different materials prepared, due to emission effects for these systems.

Keywords: Poly(3-alkylthiophenes), Photoluminescence spectroscopy, Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, Organic photovoltaic cells

Poly(3-alkylthiophenes); photoluminescence spectroscopy; Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy; organic photovoltaic cells.

1. Introduction

The polymer semiconductor interface with the substrate could be better exploited for building efficient organic photovoltaic cells (OPC), and has therefore played a crucial role in the research because of its charge transport properties [1]. These polymers include poly(3-alkylthiophenes) (P3ATs), which have also been assessed regarding the structural stability of segments present in their polymer chains [2, 3, 4, 5].

Generally, in order to improve the efficiency of organic devices, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxithiophene) has been used, doped with poly(4-styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) at the interface between the indium oxide doped with tin (ITO) and the P3ATs, as a facilitating layer to improve hole injection into OPCs [3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. However, this interface can be easily rendered fragile by acid attack on the surface of the ITO, due to the chemical nature of the PEDOT:PSS [12].

In order to establish an interface that is more stable under ambient conditions, one alternative is to use materials between the P3AT polymers. Bento et al. [13], studied the electrochemical properties of homopolymer and blended P3AT films prepared under ambient conditions. The polymer blends were obtained electrochemically by a solution of monomers at 1:1 (v/v). The Bode-Phase diagrams obtained by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were fundamental for determining the influences of the different charge transfer processes on the conductivity of each system. Similarly, De Santana et al. [4], observed that the synthesis temperature and the nature of the electrolyte were important variables for understanding polymer segment stability in the electrochemical synthesis of P3ATs.

In order to verify the optical properties of these materials, Batista et al. [14], used photoluminescence spectroscopy (PL) with time-dependent resolution and observed that the different segments stabilized in the P3AT polymer matrix resulted in differences in the emission decay time and contributions, in which an increase in faster emission contributions and a reduction in emission decay time indicated the formation of segments that facilitated energy transport between the chains.

In this study, we electrochemically synthesized blends of poly(3-methylthiophene) and poly(3-octylthiophene) (P3MT and P3OT) to obtain a 1:1 (v/v) blend of monomers 3-methylthiophene and 3-octylthiophene on platinum electrode, designated Pt/P3MT:P3OT, in a lithium perchlorate and acetonitrile (LiClO4-ACN) electrolyte, keeping the temperature constant at 18 °C. We also synthesized layered films from solutions containing monomers and previously deposited on platinum to produce the interfaces designated Pt/P3MT/P3OT and Pt/P3OT/P3MT.

The stabilized interfaces were studied with the aim of monitoring the structural stability of these materials after preparation, keeping them under ambient conditions for this assessment. These systems were characterized by EIS, monitoring the presence of radical cation and dication segments at the interfaces as prepared and as time progressed, allowing us to monitor the equilibrium between segments and to investigate the equilibrium between the segments and the systems optical characteristics by photoluminescence spectroscopy, and to measure the photoluminescence decay time for discussion of possible effects on emission of these materials as prepared.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

The 3-methylthiophene (C5H6S), 3-MT, and 3-octylthiophene (C12H20S), 3-OT monomers at 99% purity were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. The support electrolyte was lithium perchlorate (LiClO4) at 99% purity, supplied by AcrosOrganics, and the solvent was acetonitrile (CH3CN), ACN, obtained from JT Baker at 99.5 % purity and HPLC grade.

2.2. Electrochemical synthesis

All the films in this study were synthesized electrochemically on Pt electrode by chronoamperometry using an Autolab PGSTAT 302 N potentiostat/galvanostat coupled to a microcomputer running NOVA 1.8. The experimental arrangement was as described in previous studies [3, 15, 16], keeping the temperature at 18 °C, or alternatively with no ambient temperature control. Characteristic current-time curve can be seen in a previous publication [17]. The results were reproducible, considering the synthesis conditions monitored, and the data were presented after the analysis of triplicates.

For the P3MT and P3OT homopolymers and the layered Pt/P3MT/P3OT and Pt/P3OT/P3MT films, a potential of 1.70 V was applied for 120 s, and for the blend, the potential of 1.70 V was applied for 240 s, using a solution of LiClO4 0.100 mol L−1 in ACN containing the monomers at concentrations of 0.035 mol.L−1 for the 3-MT and 0.040 mol L−1 for the 3-OT. After preparing the interfaces under these conditions, they were left under ambient conditions for subsequent analysis at specified times.

2.3. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

To obtain impedance diagrams at open circuit potential (OCP), an Autolab PGSTAT 302 N potentiometer was used with a FRAM32 impedance module, varying the frequency from 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz. The open-circuit stabilization potentials were reached when the OCP remained constant ± 5 mV for 30 min, the time necessary to reach the stationary state at which the current remained constant.

2.4. Photoluminescence spectroscopy and photoluminescence decay time

The films were optically characterized using a 457 nm diode laser for photoluminescence (PL). The results were recorded using an Ocean Optics USB2000 + spectrometer. PL decay time was measured in FluoTime 200 (PicoQuant) equipment, which performs the time-correlated single photon count (TCSPC). This equipment incorporates a microchannel plate detector (MCP) and a 440 nm 10 MHz pulsed laser for detection. System time resolution was 50 ps, with a detection band from 500 nm to 700 nm.

3. Results and discussion

Figure 1 shows the Bode-Phase diagrams at OCP related to the Pt/P3MT and Pt/P3OT homopolymers in 0.100 mol L−1 LiClO4-ACN as a function of time, after synthesis at 18 °C.

Figure 1.

Bode-Phase diagrams at OCP obtained for the (a) Pt/P3MT and (b) Pt/P3OT systems synthesized at 18 °C, at the following times: ( ) as prepared, (

) as prepared, ( ) after 24h, (

) after 24h, ( ) after 48h e (

) after 48h e ( ) after 96 h.

) after 96 h.

These results are discussed in light of the findings published by Bento et al. [9], who used electrochemical impedance spectrometry combined with in situ Raman spectroscopy to characterize the quinone segments of the thiophene ring in the materials. Bode-Phase diagrams were used so that, on applying the different potentials to the ITO/P3MT and ITO/P3OT systems, there was a phase angle displacement. The phase angle of the materials, observed in the lowest frequency region (0.01–0.10 Hz), was displaced to higher frequency regions (higher than 0.10 Hz) on applying more anodic potentials. The in situ Raman spectra for these systems were used to assign bands to the radical cation segments present at the lowest potentials and the frequencies observed at more anodic values indicated the stabilization of the dication segment.

The diagrams in Figure 1a show that the Pt/P3MT homopolymer exhibited polaronic conduction phase stabilization related to the radical cation segment at all assessment times, with the phase angle observed in the lower frequency regions (0.011 Hz).

In contrast, the Pt/P3OT system exhibited variations as time progressed. The diagram in Figure 1b shows that the film as prepared favored stabilization of the radical cation segment, with a phase around 0.010 Hz. At other times, we observed the displacement of the phase angle to the highest frequency region (0.532 and 1.182 Hz), attributed to stabilization of the bipolaronic conduction phase related to the dication segments formed by the natural dedoping effect [5].

Based on the arguments above, we studied the effects of different kinds of deposition and the temperature on stabilization of the radical cation segments in the films formed by the blended interfaces (Pt/P3MT:P3OT) and layered films (Pt/P3MT/P3OT and Pt/P3OT/P3MT) after synthesis, as a function of time.

Figure 2 a and b show the respective Bode-Phase diagrams for the Pt/P3MT:P3OT system in 0.100 mol L−1 LiClO4-ACN, both without and with synthesis temperature control, as a function of time after blend synthesis and at OCP.

Figure 2.

Bode-Phase diagrams at OCP obtained for the Pt/P3MT:P3OT system (a) without synthesis temperature control and (b) at 18 °C, at the following times: ( ) as prepared, (

) as prepared, ( ) after 48h and (

) after 48h and ( ) after 96h.

) after 96h.

The Bode-Phase diagrams of the Pt/P3MT:P3OT system as prepared (Figure 2a) with no temperature control show the coexistence of phase angles in the lowest and highest frequency regions (0.012 and 63.230 Hz), indicating the presence of polaronic and bipolaronic conduction related to the radical cation and dication segments respectively. This behavior is repeated 48h after synthesis, with a reduction in the phase angle related to the radical cation segments as a result of the natural displacement of radical cation equilibrium toward dication. At 96 h after synthesis, stabilization of bipolaronic conduction was observed, with the phase angle at 4.041 Hz.

In the Bode-Phase diagrams for the Pt/P3MT:P3OT blend synthesized at 18 °C (Figure 2b), from preparation to 96 h after synthesis we observed the predominance of the phase related to polaronic conduction in the low frequency region (0.011 Hz), indicating stabilization of the radical cation in this system. At 96 h, a second phase in the highest frequency region (16.252 Hz) was observed, indicating the presence of bipolaronic conduction, explained by the onset of displacement of the of radical cation equilibrium to dication.

Figures 3a and 3b show the Bode-Phase diagrams related to the layered interface of the Pt/P3MT/P3OT system, synthesized without and with temperature control, previously synthesized in 0.100 mol L−1 LiClO4-ACN. These were monitored as a function of time after synthesis at OCP.

Figure 3.

Bode-Phase diagrams at OCP obtained for the Pt/P3MT/P3OT (a) without synthesis temperature control, and (b) synthesis at 18 °C, at the following times: ( ) as prepared, (

) as prepared, ( ) after 48h and (

) after 48h and ( ) after 96h.

) after 96h.

In the Bode-Phase diagrams in Figure 3a related to the layered Pt/P3MT/P3OT system synthesized without temperature control, after preparation we observed the coexistence of phase angles at 0.016 and 0.317 Hz, relating respectively to polaronic and bipolaronic conduction, indicating that soon after synthesis, both the radical cation and dication segments stabilized. At 48 and 96 h after synthesis, the phase angle was displaced to 1.878 and 3.556 Hz respectively, indicating greater stabilization of dication segments as time progresses, due to the natural destabilization of radical cation segments.

In Figure 3b, showing the Pt/P3MT/P3OT system synthesized at a controlled temperature of 18 °C, we observed the stabilization of the phase angles in the low frequency region (0.011 Hz), related to polaronic conduction from preparation until 96 h after synthesis, due to the stabilization of the radical cation segments throughout the period of analysis.

In the sequence documented herein, the layer preparation positions were altered with the aim of gaining further knowledge of the interfaces formed by these polymers.

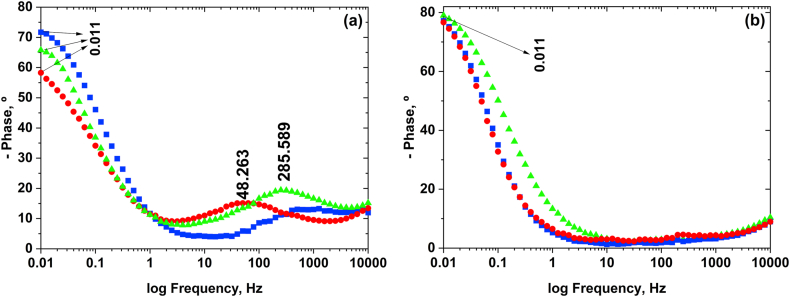

Figure 4 a and b show the Bode-Phase diagrams related to the Pt/P3OT/P3MT system, synthesized respectively without and with temperature control in 0.100 mol L−1 LiClO4-ACN as a function of the time elapsed after synthesis and at open-circuit potential (OCP).

Figure 4.

Bode-Phase diagrams at OCP obtained for the Pt/P3OT/P3MT system (a) without synthesis temperature control and (b) synthesis at 18 °C, at the following times: ( ) as prepared, (

) as prepared, ( ) after 48h and (

) after 48h and ( ) after 96h.

) after 96h.

Figure 4a shows that after synthesis of the system as prepared, the radical cation segments stabilized in the Pt/P3OT/P3MT system without temperature control, and that at 48 and 96h after synthesis, the phase angle was in the highest frequency region (48,263 and 285,589 Hz, respectively) indicating the onset of displacement of radical cation segment equilibrium to dication.

However, for the Pt/P3OT/P3MT system synthesized at room temperature (18 °C), shown in Figure 4b, the phase angle stabilized in the lowest frequency region (0.011 Hz) from preparation until 96 h after synthesis, verifying that these synthesis conditions favored the stabilization of radical cation segments throughout the assessment period.

Thus, it was possible to verify in all Pt/P3MT:P3OT, Pt/P3MT/P3OT and Pt/P3OT/P3MT systems the effect of temperature on the stabilization of quinone segments in the films, during which the films synthesized with temperature control at 18 °C stabilized the radical cation segments for longer periods of time, whereas in the films synthesized without temperature control these segments rapidly destabilized.

It was also observed that some films, including Pt/P3MT:P3OT and Pt/P3MT/P3OT, exhibited the coexistence of radical cation and dication segments, whereas the films as prepared and systems synthesized at controlled temperature exhibited stabilization of radical cation segments for 48 h in the blend and 96 h in layered systems, indicating that synthesis temperature control is an important variable in the stability of radical cation segments in P3AT polymer matrices.

In addition to the effect of temperature, the kind of deposition influenced the stabilization of radical cation segments; in films synthesized in layers, these segments were stabilized for longer periods, since the layer closest to the platinum electrode acts as an induction layer, favoring the stability of radical cation segments in the outermost layer over the platinum electrode. Thus, we observed greater stabilization of radical cation segments for longer periods of time in layered films, as opposed to homopolymers and blends, both with and without temperature control.

After electrical characterization of the interfaces studied, photoluminescence (PL) and time-resolved photoluminescence measurements were taken in order to optically characterize the systems. This was done to verify their potential for incorporation of these interfaces into devices in order to intensify the emission of radiation, even for the thin films usually incorporated into these systems.

Figure 5 shows the PL spectrum for the Pt/P3MT:P3OT film, that showed widened, low-intensity emissions, possibly formed by the three segments in the P3AT matrix: quinone with higher energy around 550 nm; aromatic around 570 nm and semiquinone with lower energy extending from 595 nm to 700 nm [3, 18].

Figure 5.

PL spectrum for the Pt/P3MT:P3OT film.

Time-resolved PL measurements were made to assess the emission decay times for films consisting solely of homopolymers (Pt/P3MT, Pt/P3OT), layered films containing the two polymers under investigation (Pt/P3OT/P3MT, Pt/P3MT/P3OT) and films prepared as blends (Pt/P3MT:P3OT). In addition to the structures and emissions of these films, decay was also investigated to shed light on emission mechanisms. The results for decay time (τ) and contributions (%) are given in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5.

Table 1.

Emission decay times and % decay contribution for Pt/P3MT, Pt/P3OT films as prepared.

| Pt/P3MT | τ1(ns) | % τ1 | τ2(ns) | % τ2 | τ average (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550 nm | 2.77 ± 0.08 | 84 | 0.439 ± 0.043 | 16 | 2.387 |

| 570 nm | 2.54 ± 0.11 | 84 | 0.328 ± 0.043 | 16 | 2.182 |

| 595 nm | 2.63 ± 0.21 | 81 | 0.422 ± 0.078 | 19 | 2.220 |

| Pt/P3OT | τ1(ns) | % τ1 | τ2(ns) | % τ2 | τ average (ns) |

| 550 nm | 1.17 ± 0.06 | 50 | 0.189 ± 0.011 | 50 | 0.679 |

| 570 nm | 1.69 ± 0.04 | 54 | 0.310 ± 0.011 | 46 | 1.062 |

| 595 nm | 1.97 ± 0.03 | 58 | 0.387 ± 0.011 | 42 | 1.306 |

Table 2.

Emission decay times and % decay contribution for Pt/P3MT, Pt/P3OT films 96 h after preparation.

| Pt/P3MT 96 h |

τ1(ns) | % τ1 | τ2(ns) | % τ2 | τ average (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550 nm | 1.37 ± 0.12 | 35 | 0.210 ± 0.008 | 65 | 0.621 |

| 570 nm | 1.22 ± 0.09 | 46 | 0.177 ± 0.007 | 54 | 0.661 |

| 595 nm | 1.20 ± 0.04 | 51 | 0.236 ± 0.007 | 49 | 0.726 |

| Pt/P3OT 96 h |

τ1(ns) | % τ1 | τ2(ns) | % τ2 | τ average (ns) |

| 550 nm | 1.66 ± 0.04 | 61 | 0.241 ± 0.012 | 39 | 1.102 |

| 570 nm | 1.55 ± 0.05 | 60 | 0.221 ± 0.011 | 40 | 1.020 |

| 595 nm | 1.21 ± 0.06 | 47 | 0.182 ± 0.009 | 53 | 0.663 |

Table 3.

Emission decay times and % decay contribution for Pt/P3OT/P3MT and Pt/P3MT/P3OT films.

| Pt/P3OT/P3MT Layered films |

τ1(ns) | % τ1 | τ2(ns) | % τ2 | τ average (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550 nm | 1.11 ± 1.00 | 2 | 0.255 ± 0.037 | 98 | 0.273 |

| 570 nm | 0.85 ± 1.96 | 15 | 0.228 ± 0.059 | 85 | 0.323 |

| 595 nm | 1.74 ± 2.96 | 25 | 0.285 ± 0.074 | 75 | 0.640 |

| Pt/P3MT/P3OT Layered films |

τ1(ns) | % τ1 | τ2(ns) | % τ2 | τ average (ns) |

| 550 nm | - | - | 0.166 ± 0.007 | 100 | 0.166 |

| 570 nm | 0.703 ± 0.120 | 19 | 0.127 ± 0.006 | 81 | 0.236 |

| 595 nm | 0.877 ± 0.006 | 47 | 0.153 ± 0.006 | 53 | 0.493 |

Table 4.

Emission decay times and % decay contribution for Pt/P3OT/P3MT and Pt/P3MT/P3OT films 96 h after preparation.

| Pt/P3OT/P3MT Layered films |

τ1(ns) | % τ1 | τ2(ns) | % τ2 | τ average (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550 nm | 1.66 ± 0.06 | 56 | 0.299 ± 0.017 | 44 | 1.068 |

| 570 nm | 2.10 ± 0.04 | 61 | 0.428 ± 0.017 | 39 | 1.453 |

| 595 nm | 2.28 ± 0.04 | 62 | 0.487 ± 0.016 | 38 | 1.592 |

| Pt/P3MT/P3OT Layered films |

τ1(ns) | % τ1 | τ2(ns) | % τ2 | τ average (ns) |

| 550 nm | 1.99 ± 0.06 | 66 | 0.384 ± 0.023 | 34 | 1.438 |

| 570 nm | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 67 | 0.349 ± 0.023 | 33 | 1.375 |

| 595 nm | 1.39 ± 0.07 | 71 | 0.293 ± 0.023 | 29 | 1.063 |

Table 5.

Emission decay times and % decay contribution for Pt/P3MT:P3OT films as prepared and 96 h after preparation.

| Pt/P3MT:P3OT 0 h |

τ1(ns) | % τ1 | τ2(ns) | % τ2 | τ average (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550 nm | 0.193 ± 0.006 | 93 | 0.024 ± 0.008 | 7 | 0.182 |

| 570 nm | 0.189 ± 0.006 | 92 | 0.023 ± 0.006 | 8 | 0.176 |

| 595 nm |

0.228 ± 0.007 |

90 |

0.034 ± 0.007 |

10 |

0.208 |

| Pt/P3MT:P3OT 96 h |

τ1(ns) |

% τ1 |

τ2(ns) |

% τ2 |

τ average (ns) |

| 550 nm | 1.44 ± 0.06 | 57 | 0.175 ± 0.009 | 43 | 0.896 |

| 570 nm | 1.41 ± 0.06 | 55 | 0.160 ± 0.009 | 45 | 0.850 |

| 595 nm | 1.30 ± 0.06 | 53 | 0.152 ± 0.008 | 47 | 0.763 |

The data were processed in light of previous results, showing that the increase in the quantity of higher-energy chains in the material should lead to a reduction in emission times, for both more isolated chains (τ1) (slower), and clusters (τ2), in which energy transfer is facilitated [11].

Table 1 gives the decay times and the percentage contributions for the Pt/P3MT and Pt/P3OT films characterized soon after preparation.

Of the results obtained overall for the Pt/P3MT and Pt/P3OT films, based on the relative emissions of the quinone (550 nm), aromatic (570 nm) and semiquinone (595 nm) segments, the Pt/P3MT film made greater contributions to the slowest decays (τ1), of 84% and 81%, characteristic of chains well isolated from one another. For the Pt/P3OT film, the quinone segments made contributions closer to the slow (τ1) and fast (τ2) relative decay times (between 46 and 58%). Faster emission was observed through the P3OT structures, in regard to both the component times obtained, and in terms of total emission contributions. These findings corroborate the average times obtained as a function of emission intensity, and the P3OT had an average decay time approximately twice as fast as those of the P3MT.

Table 2 gives the decay times and percentage contributions for the Pt/P3MT and Pt/P3OT films characterized at 96 h after preparation.

As time progressed, it was possible to observe clearly significant changes in regard to emissions from both films. The P3OT showed obvious dedoping of the semiquinone segments and subsequent formation of quinone structures, as observed in the EIS experiments as a function of time (Figure 1b). This process was evidenced by a reduction in the faster components (τ2) of the structure as a whole, with fast contributions of semiquinone segments ranging from 0.387 ns (42%) to 0.182 ns (53%). Similarly, the quinone segments showed a very characteristic increase in τaverage from 0.679 to 1.102 ns, indicating, as previously reported, a reduction in energy transfer between these structures, which at this stage were more scarce in the material. For the P3MT, although the semiquinone segments stability obtained was good (Figure 1a), its emission behavior was quite different. General behavior was typified by an overall drop by a factor of 3 in τaverage for all emission peaks, evidence of the existence of one or more mechanisms favoring energy transfer among the chains of this compound. In this case, the “debottlenecking” of semiquinone segments could be responsible at least in part for this process. This is because previously, with the film as prepared (0 h), there was so great a discontinuity for semiquinone segments that they became isolated from each other, despite their high numbers in the structure. With the dedoping of these structures and consequent formation of quinone segments, interaction among all structures was facilitated.

Tables 3 and 4 give the decay times and percentage contributions for the Pt/P3OT/P3MT and Pt/P3MT/P3OT films characterized soon after preparation.

Note that, as shown by the results in Table 3, both layered configurations caused drastic changes in the emissions from films deposited over Pt. The decay times obtained for the films as prepared (0 h) were very much lower than those obtained for the homopolymers, both at 0 h and as time progressed (Tables 1 and 2). Although we observed some slower components, fast emission was predominant, mainly in terms of quinone segment emission (98–100%). This could be explained by the abundance of these structures in the film, but in contrast to what had been previously observed, there was a higher quantity of quinone segments in multilayered films, as well as facilitated energy transfer between these structures, possibly because of the layered deposition. In addition, the emission intensity was observed to undergo changes in regard to the polymer deposited on the surface of the material, and this response was much greater for the outermost layer of P3OT.

Analyzing these results, it can be stated that, as in the case of isolated polymers, when there is a layer of P3OT on the surface (Pt/P3MT/P3OT), lower emission time is observed because of the response of the isolated material. The difference in this case is that, in the presence of a lower layer of P3MT, fast emissions from quinone structures (550 nm) are favored, showing that there is a greater abundance of quinone structures in the film, facilitating better energy migration in the system and therefore emission, followed by a drop in τ.

In regard to behavior over time, once again we observed changes in the film characteristics. As expected, and as previously discussed, the semiquinone segments are dedoped with the consequent formation of quinone segments. This behavior is evidenced by an increase in quinone structure emission time τaverage under the influence of a drastic increase in long contributions related to the energetically isolated chains. In this case in particular, since there is a greater interaction between the two polymer layers, the situation is not very well characterized in terms of semiquinone segment times.

Finally, we analyzed Pt/P3MT:P3OT blends. The results are given in Table 5, with decay times and percentage contribution of the Pt/P3MT:P3OT films as prepared and at 96 h after preparation.

The results for the Pt/P3MT:P3OT interface indicate significant differences in regard to decay time. For the film as prepared, there were two decay components, but these can no longer be discussed in terms of a slower (>800 ps) and a faster (∼200 ps) component. We observed the fast component only, in the presence of a second very fast component, beyond the equipment's evaluation capability (<40 ps). Thus, what we observe is fast emission from all blend segments, characterizing facilitated energy transfer. Once again, as time progresses, there are structural changes in the segments making up the blend, evidenced by the increase in τaverage, characterized especially by the occurrence of slower components in the films at 96 h after preparation.

4. Conclusions

The deposition of the P3MT layer over the P3OT previously deposited on Pt, or vice versa, at a potential of +1.70 V, could indicate the predominance of radical cation segments in the polymer matrices of both layered films. Furthermore, as a function of time, the stability of these segments in the layer next to the platinum electrode favors the stability of the radical cation in the outermost layer on the electrode.

For the Pt/P3MT:P3OT blend, destabilization of radical cation segments to dication segments after a long period due to the absence of an induction layer to retain the radical cation segments. Thus, these layered interfaces could provide an alternative for replacing the poly(3,4-ethyldioxithiophene)-poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) in OPCs.

Assessing the effect of temperature on synthesis, we observed that films synthesized at a controlled temperature of 18 °C stabilized radical cation segments for longer times, whereas films synthesized with no temperature control exhibited destabilization of these segments over time, indicating that synthesis temperature control is an extremely important factor in the stabilization of radical cation segments.

Based on the emission decay time of homopolymers films, under the effect of natural dedoping, the quinone segments showed a reduction in energy transfer between structures, disfavoring energy transport among all segments, including semiquinone segments still present in the polymer matrix.

The blends showed improved energy transport properties, since the decay times were much lower than those of the other systems and exhibited an increase in emission time 96 h after synthesis, indicating that structural changes occurred resulting in an increase in average emission decay time. In layered systems, decay time was much lower than those of the homopolymers at all evaluation times, indicating better energy transport in layered systems compared to homopolymers, and the deposition sequence favors energy transport between structures, with the best results for the Pt/P3MT/P3OT system, validating the EIS results.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Leandro Rodrigues Koenig: Performed the experiments.

Aline Domingues Batista: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Wesley Renzi: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Henrique de Santana: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Araucaria Foundation (09/2016- PROPPG/UEL 03/2016), and by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). Leandro R. Koenig was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation to the Spectroscopy Laboratory (SPEC) at the PROPPG/UEL Multiuser Center.

References

- 1.Therézio E.M., Piovesan E., Anni M., Silva R.A., Oliveira O.N., Marletta A. Substrate/semiconductor interface effects on the emission efficiency of luminescent polymers. J. Appl. Phys. 2011;110:44504. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng W.D., Qi Z.J., Sun Y.M. Comparative study of photoelectric properties of a copolymer and the corresponding homopolymers based on poly(3-alkylthiophene)s. Eur. Polym. J. 2007;43:3638–3645. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bento D.C., Maia E.C.R., Cervantes T.N.M., Fernandes R.V., Di Mauro E., Laureto E., da Silva M.A.T., Duarte J.L., Dias I.F.L., de Santana H. Optical and electrical characteristics of poly(3-alkylthiophene) and polydiphenylamine copolymers: applications in light-emitting devices. Synth. Met. 2012;162:2433–2442. [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Santana H., Maia E.C.R., Bento D.C., Cervantes T.N.M., Moore G.J. Spectroscopic study of poly(3-alkylthiophenes) electrochemically synthesized in different conditions. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2013;24:3352–3358. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koizumi H., Dougauchi H., Ichikawa T. Mechanism of dedoping processes of conducting poly(3-alkylthiophenes) J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:15288–15290. doi: 10.1021/jp051989k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang F., Vollmer A., Zhang J., Xu Z., Rabe J.P., Koch N. Energy level alignment and morphology of interfaces between molecular and polymeric organic semiconductors. Org. Electron. 2007;8:606–614. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baibarac M., Lapkowski M., Pron A., Lefrant S., Baltog I. SERS spectra of poly(3-hexylthiophene) in oxidized and unoxidized states. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1998;29:825–832. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maia E.C.R., Bento D.C., Laureto E., Zaia D.A.M., Therezio E.M., Moore G.J., de Santana H. Spectroscopic analysis of the structure and stability of two electrochemically synthesized poly(3-alkylthiophene)s. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2013;78:507–521. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bento D.C., Da Silva E.A., Olivati C.A., Louarn G., De Santana H. Characterization of the interaction between P3ATs with PCBM on ITO using in situ Raman spectroscopy and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015;26:7844–7852. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bento D.C., Maia E.C.R., Fernandes R.V., Laureto E., Louarn G., de Santana H. Photoluminescence and Raman spectroscopy studies of the photodegradation of poly(3-octylthiophene) J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2014;25:185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renzi W., Franchello F., Cordeiro N.J.A., Pelegati V.B., Cesar C.L., Laureto E., Duarte J.L. Analysis and control of energy transfer processes and luminescence across the visible spectrum in PFO: P3OT blends. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017;28:17750–17760. [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Jong M.P., van IJzendoorn L.J., de Voigt M.J.A. Stability of the interface between indium-tin-oxide and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/poly(styrenesulfonate) in polymer light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000;77:2255. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bento D.C., Maia E.C.R., Cervantes T.N.M., Olivati C.A., Louarn G., de Santana H. Characterization of the interaction between P3ATs with PCBM on ITO using in situ Raman spectroscopy and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015;26:7844–7852. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batista A.D., Renzi W., Duarte J.L., de Santana H., Stability Structural, Studies Optical. Of poly(3-hexylthiophene) in an ITO/PEDOT: PSS/P3HT interface. J. Electron. Mater. 2018;47:6403–6410. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cervantes T.N.M., Bento D.C., Maia E.C.R., Zaia D.A.M., Laureto E., Da Silva M.A.T., Moore G.J., de Santana H. In situ and ex situ spectroscopic study of poly(3-hexylthiophene) electrochemically synthesized. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2012;23:1916–1921. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bento D.C., Maia E.C.R., Rodrigues P.R.P., Louarn G., de Santana H. Poly(3-alkylthiophenes) and polydiphenylamine copolymers: a comparative study using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2013;24:4732–4738. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maia R., Bento D.C., Laureto E., Zaia D.A.M., Therézio M., Moore G., de Santana H. Spectroscopic analysis of the structure and stability of two electrochemically synthesized poly(3-alkylthiophene)s. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2013;78:507–521. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batista A.D., Renzi W., Fernandes R.V., Laureto E., Duarte J.L., de Santana H. Effects of Au/PEDOT: PSS/P3HT interface morphology on the electrical and optical properties of poly (3-hexylthiophene) J. Electron. Mater. 2019;48:6008–6017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.