Abstract

Introduction

Personality disorders (PD) have a serious impact on the lives of individuals who suffer from them and those around them. It is common for family members to experience high levels of burden, anxiety, and depression, and deterioration in their quality of life. It is curious that few interventions have been developed for family members of people with PD. However, Family Connections (FC) (Hoffman and Fruzzetti, 2005) is the most empirically supported intervention for family members of people with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

Aim

The aim of this study is to explore the effectiveness of online vs face-to-face FC. Given the current social constraints resulting from SARS-CoV-2, interventions have been delivered online and modified.

Method

This was a non-randomized pilot study with a pre-post evaluation and two conditions: The sample consisted of 45 family members distributed in two conditions: FC face-to-face (20) performed by groups before the pandemic, and FC online (25), performed by groups during the pandemic. All participants completed the evaluation protocol before and after the intervention.

Results

There is a statistically significant improvement in levels of burden (η 2 = 0.471), depression, anxiety, and stress (η 2 = 0.279), family empowerment (η 2 = 0.243), family functioning (η 2 = 0.345), and quality of life (μ2 η 2 = 0.237). There were no differences based on the application format burden (η 2 = 0.134); depression, anxiety, and stress (η 2 = 0.087); family empowerment (η 2 = 0,27), family functioning (η 2 = 0.219); and quality of life (η 2 = 0.006), respectively).

Conclusions

This study provides relevant data about the possibility of implementing an intervention in a sample of family members of people with PD in an online format without losing its effectiveness. During the pandemic, and despite the initial reluctance of family members and the therapists to carry out the interventions online, this work shows the effectiveness of the results and the satisfaction of the family members. These results are particularly relevant in a pandemic context, where there was no possibility of providing help in other ways. All of this represents a great step forward in terms of providing psychological treatment.

Keywords: Personality disorders, Psychological treatment to relatives, Dialectical behavior therapy, Relatives, Carers, Family members, Emotional dysregulation

1. Introduction

Personality disorders (PD) encompass rigid, inflexible, and persistent patterns of behaviors, thoughts, or feelings that have a severe impact on an individual's life (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These disorders tend to be comorbid with other psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, behavioral disorders, substance use, eating disorders, or mood disorders (Plana-Ripoll et al., 2019), and they have a considerable public health or social cost due to continuing crises and relapses (Caballo, 2009; Plana-Ripoll et al., 2019). In this regard, about 2.8% of the people who come into contact with the mental health system present a PD (Newton-Howes et al., 2020), and this percentage rises when focusing on people who seek medical care in a hospital. Specifically, people with PD represent 20.5% of emergencies and 26.6% of inpatients in hospitals (Lewis et al., 2019). In the community, it is estimated that 9% of people suffer from at least one PD (Lenzenweger et al., 2007).

At present, psychotherapy is the first line of treatment for PD (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2012). In the last years, there has been an increase in clinical research on the efficacy of psychological treatments for borderline personality disorders. There are treatments with highly demonstrated efficiency, as the dialectical behavioral therapy (Linehan, 1993). However, there are scarce empirically supported interventions for people with personality disorders. So far, Young's Schema-Focused Therapy (Young and Brown, 1994) or the Alden's cognitive-interpersonal therapy for avoidant-personality disorder (1989). It is common in clinical practice for therapists to try to adapt empirically supported treatments to these problems (Guillén et al., 2018).

In this regard, family members are a fundamental part of the recovery process of these patients (Acres et al., 2019), and they often play the role of informal therapists (de Mendieta et al., 2019). However, in many cases, family members lack standardized information to help them understand the disease and the chaos surrounding it and support them during the patient's recovery process and in crisis management (Acres et al., 2019; Hoffman et al., 2003). In addition, the daily difficulties faced by the families and the emotional burden they experience can lead to a disruption in the functioning of the family unit (Marco-Sánchez et al., 2020; Rajalin et al., 2009). Thus, family members are more likely to experience mental health problems (e.g., Bailey and Grenyer, 2014; Seigerman et al., 2020), such as depression, anxiety, or stress (Bennett et al., 2019; Greer and Cohen, 2018), compared to the general population; and some of these problems, such as burden (de Mendieta et al., 2019), emotional regulation difficulties (Bailey and Grenyer, 2014), and impaired empowerment (Kay et al., 2018), are greater than in family members of patients with other severe mental disorders (Bailey and Grenyer, 2013, Bailey and Grenyer, 2014) or serious illnesses (Seigerman et al., 2020).

Despite the high level of need of family members of people with PD, few interventions have been developed for them (Guillén et al., 2020; Sutherland et al., 2020). Until a few years ago, treatments were targeted exclusively at patients, and if family members were included, it was only in some specific sessions with the aim of better understanding and helping patients (e.g., Blum et al., 2002; Rathus and Miller, 2002; Woodberry and Popenoe, 2008). With the same aim in mind, there are some patient and family programs where they receive treatment together (Kazdin et al., 1992; Santisteban et al., 2003, Santisteban et al., 2015). However, specific programs exclusively for family members have gradually been developed. Although some of them are targeted at family members of patients with any PD and based on psychoeducation strategies and DBT skills training (e.g., Guillén et al., 2018), to date, most of the empirically supported programs are directed toward family members of BPD patients. All these interventions are offered in group format, but they differ in their orientation and structure.

Thus, programs for family members can be exclusively oriented toward psychoeducation, with the aim of providing information about BPD in order to increase their understanding of the behaviors of these patients and improve the family relationship (Grenyer et al., 2018; Pearce et al., 2017), or they can be oriented mainly toward skills training (Hoffman et al., 2005, Hoffman et al., 2007; Miller and Skerven, 2017; Regalado et al., 2011; Wilks et al., 2016).

To date, the most empirically supported intervention for family members of BPD patients is Family Connections (FC) (Hoffman et al., 2005), a 12-session adaptation of DBT, also delivered in a group format. Subsequent replications of this intervention have demonstrated its effectiveness in family members of patients with BPD (Flynn et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2005, Hoffman et al., 2007; Ekdahl et al., 2014; Liljedahl et al., 2019; Neiditch, 2010). Thus, FC has been helpful in reducing levels of burden (Flynn et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2005; Liljedahl et al., 2019; Neiditch, 2010), depression (Flynn et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2007; Neiditch, 2010), stress (Fonseca-Baeza et al., 2020), grief (Flynn et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2005, Hoffman et al., 2007; Neiditch, 2010), and expressed emotion (Liljedahl et al., 2019), as well as in improving mastery (Flynn et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2005, Hoffman et al., 2007), empowerment (Neiditch, 2010), and hope (Miller and Skerven, 2017). Our work group implemented this program for BPD families in an association for PD families and obtained good results (Fonseca-Baeza et al., 2020). Therefore, so far, in the case of personality disorders, there are few empirically supported treatments for both patients and their families and relatives (Fonseca-Baeza et al., 2020; Guillén et al., 2018). In addition, these treatments are sometimes difficult to implement, in many cases, implementation is limited and not accessible to all individuals (Iliakis et al., 2019), and so there is a need to address how these evidence-based treatments can be made available to more people.

There is strong agreement in the literature that online interventions provide the opportunity to offer treatments to people who would otherwise not be able to access them (e.g., Frías et al., 2020; Paldam et al., 2018; Rogers et al., 2017). Internet-based interventions have been found to be effective in reducing some symptomatology associated with PD, such as alcohol misuse (Riper et al., 2014), non-suicidal self-injury (Bjureberg et al., 2018; Lewis et al., 2012), suicidal ideation (Christensen et al., 2014; Hetrick et al., 2014; Lai et al., 2014; Robinson et al., 2014, Robinson et al., 2016), or emotional dysregulation (Bjureberg et al., 2018). Focusing on interventions directed to family members of patients with PD, the MOST platform (Lederman et al., 2014) has included Kindred, an online intervention for carers of young people with BPD that delivers psychoeducation and therapy, carer-to-carer social networking, and sessions with clinicians. In a pilot study, Kindred has shown improvements in both carers and BPD patients, even at a three-month follow-up (Gleeson et al., 2020).

However, as far as we know, there is only one study that administers an online intervention through a Webex videoconferencing platform. The intervention is, Schema Focused Therapy, which has been adapted as an online intervention for older adults (van Dijk et al., 2020). It is integrative psychotherapy combining theory and techniques from previously existing therapies, including, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychoanalytic object relations theory, attachment theory, and Gestalt therapy (Kellogg and Young, 2008). Schema therapy is an evidence based treatment for borderline personality disorders, and has been adapted for other disorders, including late-life affective disorders.

In summary, on the one hand, in previous face-to-face studies, FC has been shown to be effective in reducing burden and stress and increasing validation and problem-solving skills of family members of people with PD (Fonseca-Baeza et al., 2020). On the other hand, access to effective online interventions has become more urgent in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, where partial or total lockdown and social distance measures have forced people to change the way they relate to each other. For this reason, interventions have quickly been adapted to online delivered formats due to this situation (e.g., van Dijk et al., 2020).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that explore whether there are differences in the effectiveness of family interventions depending on the format: administering the intervention via videoconference (online) or in person (face to face). The main objective of this study is to assess, in a pragmatic pilot study, the feasibility and effectiveness of FC implemented in an online format in family members of people with personality disorders, compared to the same protocol carried out in face-to-face groups. The specific objectives of the study are: a) to examine whether there are statistically significant differences before vs after the intervention; b) to examine whether there are statistically significant differences between face-to-face and online formats; and c) to analyze the opinions of participants in the online format about their experience in this modality.

Based on previous studies and literature, we propose the following exploratory hypotheses: a) both implementation modalities will improve the primary (burden, depression, anxiety, and stress) and secondary (empowerment, family function, emotional regulation, resilience, quality of life, and validation) outcome measures; b) there will be no differences between the face-to-face and online formats; and c) participants in the online format will be satisfied with this modality.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and inclusion criteria

This study used a non-probabilistic convenience sample of family members of persons diagnosed with PD. The total sample consisted of 45 family members (80% female, n = 36; aged 43–73 years; M = 57.20, SD = 6.95). Regarding parentage, the majority were mothers (73.3%, n = 33), followed by fathers (15.6%, n = 7), partners (6.7%, n = 3), brothers (2.2%, n = 1), and aunts (2.2%, n = 1). Regarding the educational level, 26.7% had primary education (n = 12), 42.2% secondary education (n = 19), 26.7% higher education (n = 12), and 4.4% had no studies (n = 2). Regarding marital status, 77.8% were married (n = 35), 13.3% divorced (n = 6), 6.7% single (n = 3), and 2.2% widowed (n = 1). Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample in both intervention conditions.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of family members in the two implementation conditions of the intervention.

| FC face-to-face n = 20 | FC online n = 25 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 17 (85%) | 19 (76%) |

| Men | 3 (15%) | 6 (24%) | |

| Age | M = 60.70 (SD = 4.601) | M = 54.40 (SD = 7.303) | |

| Family member's relationship | Mother | 16 (80%) | 17 (68%) |

| Father | 3 (15%) | 4 (16%) | |

| Partner | 1 (5%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Brother | – | 1 (4%) | |

| Aunt | – | 1 (4%) | |

| Educational level | No studies | 2 (10%) | – |

| Primary education | 10 (50%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Secondary education | 8 (40%) | 11 (44%) | |

| Higher education | – | 12 (48%) | |

| Marital status | Married | 19 (95%) | 16 (64%) |

| Divorced | – | 6 (24%) | |

| Single | – | 3 (12%) | |

| Widowed | 1 (5%) | – | |

| Family member's gender | Women | 10 (58.8%) | 17 (77.3%) |

| Men | 7 (41.2%) | 5 (22.7%) | |

| Family member's age | M = 31.94 (SD = 11) | M = 26.36 (SD = 11.35) |

Note: FC = Family Connections.

The sample of patients was composed of 39 persons diagnosed with PD (68% female, n = 27; aged 14–43 years; M = 29.21, SD = 11.40). Regarding the patients' diagnosis, 71% (n = 28) had borderline personality disorder, 22.45% (n = 9) had an unspecified personality disorder, 5.9% (n = 1) had schizotypal personality disorder, and 5.90% (n = 1) had an antisocial personality disorder. The mean age of onset of the disorder was 16 years. Fifty-six percent of the patients were undergoing psychological treatment, and 44% were not. The mean for suicidal attempts was 2.78, with 3 self-injuries in the past six months, 1.62 psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 5 years, and 0.34 psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 6 months.

Inclusion criteria for participating in the intervention were: a) being a family member of a person diagnosed with PD (DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); b) signing an informed consent form declaring voluntary participation in the study with no financial incentive; and c) agreeing to attend the intervention sessions. The exclusion criterion was the presence of a serious mental disorder in the family member that required specific specialized care (psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, etc.) or that would disrupt the progress of the intervention.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

Demographic variables questionnaire: sex, age, parentage, and educational level of family members, and age and sex of persons with PD.

2.2.2. Primary intervention outcomes

Burden assessment scale (BAS; Reinhard et al., 1994). This scale assesses the family members' objective and subjective burden in the past six months. It consists of 19 items grouped in seven subscales. Higher values indicate a heavier burden. Internal reliability of the scale ranges from 0.89 to 0.91, and it shows adequate validity. In this study, Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.93 to 0.66.

Depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995). This scale assesses negative emotional symptoms. It consists of 21 items grouped in four subscales. Higher values indicate more severe negative emotional symptoms. Regarding the internal consistency, Cronbach's alphas were excellent, ranging from 0.94 to 0.87. In this study, Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.94 to 0.84.

2.2.3. Secondary intervention outcomes

Family empowerment scale (FES; Koren et al., 1992). This scale assesses three forms of empowerment: attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors. It consists of 34 items grouped in four subscales. Higher scores indicate a greater sense of empowerment. Regarding the internal consistency, Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.87 to 0.88, and validity and reliability were adequate. In this study, Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.93 to 0.82.

Family assessment device – global functioning scale (FAD-GFS; Epstein et al., 1983). This questionnaire assesses general family functioning. It consists of 60 items grouped in seven subscales. Higher scores indicate worse family functioning. Regarding the internal consistency, Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.92 to 0.72, and test-retest reliabilities were adequate. In this study, Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.89 to 0.69.

Quality of life index (QLI; Mezzich et al., 2000). This index assesses various dimensions related to self-perceived well-being and quality of life. It consists of 10 items. Higher scores indicate greater quality of life. This instrument has good psychometric properties, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.89 and test-retest reliability of 0.87. In this study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.91.

2.2.3.1. Treatment opinion questionnaire

This is an ad hoc questionnaire directed to the participants in the online group. They were asked in which modality they would prefer to repeat FC (online or face-to-face format), and which modality they would recommend to other family members.

2.3. Procedure

As described above, the aim of this study was to implement the FC intervention in family members of people with PD. To this end, approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Valencia. Participants in the study were from two institutions: a) the Valencian Association for Family members of persons with PD; and b) a Specialized Unit for Personality Disorders, both located in Valencia, Spain. Once the study had been explained to the family members, they were offered the opportunity to participate in the study. Interested family members signed the informed consent form, and several clinical psychologists carried out a clinical interview to verify that they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Participants filled in the assessment protocol at two moments, PRE and POST intervention. The family members were assigned to one of two experimental conditions, depending on the moment they received the intervention. Participants who received FC between October 2019 and March 2020 performed the intervention in the face-to-face format. However, in March 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic began, and we had to adapt the format for the groups that were about to start. Therefore, the family members who received the intervention between October and December 2020 performed the intervention in online format. This decision was determined by the home confinement and serious restrictions adopted in Spain after the nationwide state of alert was activated due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Once the intervention had ended, a focus group was carried out online with 25 people in order to record family members' personal opinions about the intervention. A focus group is a qualitative research method that provides information about a specific topic from the perspective of a group of people who share a central element of their experience, reducing the influence of the researcher during the process (Madriz, 2000). In this case, participants were asked an open question about their willingness to repeat or recommend FC in online format, and a psychologist wrote down each participant's answer.

2.3.1. Intervention

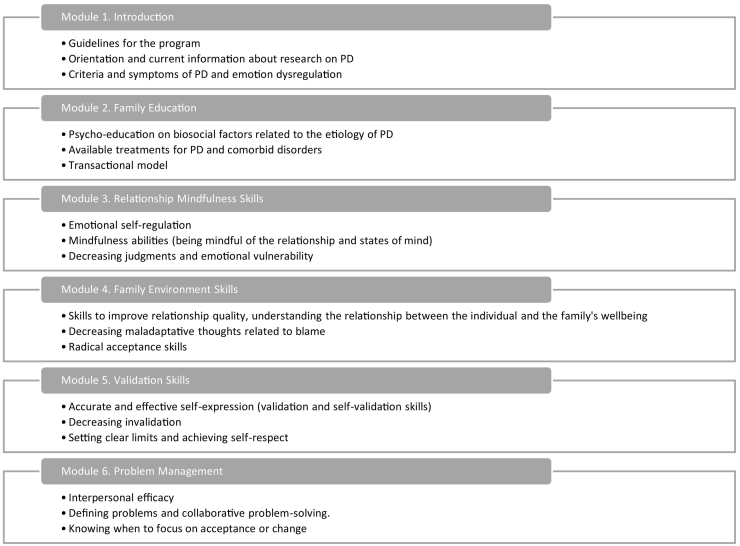

FC is a group intervention structured in six modules (Hoffman et al., 2005) conducted in 12 two-hour sessions held once a week. The intervention was led by two psychologists with specific training in FC. There were 8–12 participants per group. The modules include information about the latest research on PD, BPD, and emotional dysregulation, associated symptoms and behaviors, and skills and coping strategies to better manage family relationships and regulate their own emotions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Family Connections Intervention. Hoffman et al., 2005, Hoffman et al., 2007.

The duration, number of participants, number of sessions, frequency, and structure of the sessions were the same in both conditions. The two conditions received the same intervention; the only difference was the format, face-to-face or online. Regarding the structure of the sessions, at the beginning of the session, homework was reviewed. Subsequently, the different skills were introduced and put into practice through several group dynamics. More specifically, in the sessions the skill is introduced, e.g. validation, acceptance, mindfulness, or problem management. In each of them, the skill to be worked on during the session is presented. Examples are given from the family members themselves, and a discussion is held to see if the skill has been understood. Videos of other family members (actors) with the same problem are used, and the consequences of using or not using the different skills are shown. Finally, time is left to share, discuss, support in each particular case, how they can learn to introduce the skill. Participants are reinforced and validated for the effort they are making, from a “non-judgmental” stance, always encouraging them to learn more skills and to use them. At the end of each session, the homework is introduced.

2.3.2. Face-to-face implementation format

The intervention was carried out at the headquarters of the Association of Family Members of People with PD. Two groups were held; one from October to December 2019 and the other from January to March 2020. One week before the beginning of FC, participants were scheduled to receive the assessment protocol, which had to be filled in before the intervention. In the last intervention session, the protocol was given to them again. One week later, the protocol was collected.

2.3.3. Online implementation format

The intervention was carried out through a videoconferencing platform. Two groups were held from October to December 2020, one composed of family members from the Association and the other composed of family members of patients who attended the Specialized Unit for Personality Disorders. One week before the beginning of FC, participants received the assessment protocol via email, and they had to fill it in before the intervention. At the end of the last intervention session, the protocol was sent to them again. One week later, the focus group took place through the videoconferencing platform.

2.4. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS.25 (IBM Corp, 2017). First, the reliability of the measurement instruments was analyzed, and subscales with a Cronbach's alpha below 0.60 were eliminated. Regarding the reliability of the instruments, the following subscales were eliminated: worry (BASS; α = 0.30), problem solving (FAD-GFS; α = 0.52), communications (FAD-GFS; α = 0.59), roles (FAD-GFS; α = 0.13), affective responsiveness (FAD-GFS; α = 0.49), and behavioral control (FAD-GFS; α = 0.59). Second, to examine whether there were any differences between the two experimental conditions before beginning the intervention, Student's t or X2 were carried out. Third, to compare the efficacy of the two conditions, multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were conducted, and partial eta squared was calculated as the effect size measure.

3. Results

Regarding the sociodemographic variables of the family members, there were no significant differences between the two conditions in family members' gender (χ2(1) = 0.563, p = .453) or parentage (χ2(5) = 2.843, p = .724) before the intervention; however, the family members in the online format were younger (t (43) = 3.357, p = .002) than family members in the face-to-face format, and they had reached a higher educational level (χ2(3) = 19.492, p = .000) (Table 1). Regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of the patients, there were no difference in gender (χ2 (1) = 3.240, p = .072) or age (t (42) = 1.196, p = .238) between the conditions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of persons diagnosed with personality disorders in the two implementation conditions of the intervention.

| FC face-to-face n = 17 | FC online n = 22 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 10 (58.8%) | 17 (77.3%) |

| Men | 7 (41.2%) | 5 (22.7%) | |

| Age | M = 32.06 (SD = 11.20) | M = 26.36 (SD = 11.35) | |

| Personality disorder | Borderline | 12 (70.6%) | 16 (72.7%) |

| Unspecified | 3 (17.6%) | 6 (27.3%) | |

| Schizotypal | 1 (5.9%) | ||

| Antisocial | 1 (5.9%) | ||

| Psychological care currently | Yes | 10 (58.8%) | 12 (54.5%) |

| No | 7 (41.2%) | 10 (45.5%) | |

| Onset age | M = 16 (SD = 6.53) | M = 16.33 (SD = 1.66) | |

| Suicidal attempts | M = 4 (SD = 5.88) | M = 1.53 (SD = 1.775) | |

| Self-injuries (last 6 months) | M = 3 (SD = 6.52) | M = 6 (SD = 18.52) | |

| Psychiatric hospitalisations (last 5 years) | M = 2.18 (SD = 3.13) | M = 1.06 (SD = 1.81) | |

| Psychiatric hospitalisations (last 6 months) | M = 0.41 (SD = 0.80) | M = 0.27 (SD = 0.59) |

Note: FC = Family Connections.

Regarding the primary outcomes, before the intervention there were no significant differences between conditions on the BAS subscales: objective burden (t (42.157) = 0.954, p = .345), subjective burden (t (43) = −0.802, p = .427), limitations on personal activity (t (40.574) = 1.187, p = .242), negative effects on social interactions (t (40.948) = −0.797, p = .430), resentment (t (41.309) = −1.036, p = .306), and the global scale (t (43) = 0.183, p = .856); or on the DASS-21 subscales: depression (t (43) = −0.487, p = .629), anxiety (t (43) = −1.140, p = .260), stress (t (43) = −0.123, p = .903), and total score (t (43) = −0.625, p = .535). Regarding secondary outcomes, there were no significant differences on the following FES subscales before the intervention: family (t (43) = 1.544, p = .130) and service system (t (43) = 1.566, p = 1.25); there were no significant differences on some FAD-GFS subscales either: general functioning (t (42) = −1.383, p = .174) and the global scale (t (42) = 0.817, p = .059). Moreover, there were no differences on the QLI (t (42) = 0.590, p = .558). However, statistically significant differences were found before the intervention on the following subscales: community/political (FES) (t (43) = 2.298, p = .026), global scale (FES) (t (43) = 2.062, p = .045), and affective involvement (FAD-GFS) (t (42) = −2.446, p = .019).

As Table 3 shows, MANOVAs revealed that, using Pillai's trace, after the intervention family members presented statistically significant improvements in the primary outcomes – BAS (F (7,37) = 4.708, p = .001), DASS-21 (F (3,41) = 5.277, p = .004) – and in some secondary outcomes – FES (F (3,41) = 4.382, p = .009), FAD-GFS (F (8,35) = 2.309, p = .042), and QLI (F (1,42) = 13.025, p = .001), regardless of the administration format (F (7,37) = 0.819, p = .578; F (3,41) = 1.298, p = .288; F (3,41) = 0.383, p = .766; F (8,35) = 1.227, p = .313; F (1,42) = 0.272, p = .605.

Table 3.

Measures of family members before and after the intervention in the two implementation conditions.

| FC face-to-face |

FC online |

Pre-post |

Between groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment M (SD) | Post-treatment M (SD) | Pre-treatment M (SD) | Post-treatment M (SD) | F | η2 | F | η2 | |

| Burden (BAS) | 4.708⁎⁎⁎ | 0.471 | 0.819 | 0.134 | ||||

| Objective burden | 29.77(5.52) | 26.16(5.47) | 27.84(8.02) | 26.12(6.86) | 13.453⁎⁎⁎ | 0.238 | 1.696 | 0.038 |

| Subjective burden | 27.50(4.54) | 24.74(4.86) | 28.84(6.30) | 26.62(5.47) | 9.732⁎⁎ | 0.185 | 0.115 | 0.003 |

| Limitations on personal activity | 12.85(2.58) | 11.11(2.61) | 11.64(4.20) | 10.76(3.57) | 14.301⁎⁎⁎ | 0.250 | 1.552 | 0.035 |

| Negative effects on social interactions | 10.65(2.03) | 9.53(2.23) | 11.28(3.23) | 10.72(2.70) | 4.996⁎ | 0.104 | 0.560 | 0.013 |

| Resentment | 5.30(1.26) | 4.74(1.25) | 5.80(1.96) | 5.36(1.68) | 3.658 | 0.078 | 0.055 | 0.001 |

| Global scale | 54.40(8.86) | 48.42(8.67) | 53.80(12.35) | 50.08(10.14) | 13.695⁎⁎⁎ | 0.242 | 0.743 | 0.017 |

| Depression, anxiety, and stress (DASS-21) | 5.277⁎⁎ | 0.279 | 1.298 | 0.087 | ||||

| Depression | 5.94(4.17) | 4.37(3.98) | 6.68(5.31) | 4.56(3.39) | 12.036⁎⁎⁎ | 0.219 | 0.264 | 0.006 |

| Anxiety | 3.35(3.07) | 2.21(2.40) | 4.72(4.61) | 4.2(3.85) | 3.564 | 0.077 | 0.497 | 0.011 |

| Stress | 8.35(3.86) | 5.37(3.23) | 8.52(5.12) | 6.68(5.31) | 15.753⁎⁎⁎ | 0.268 | 0.962 | 0.022 |

| Total | 17.64(10.19) | 11.95(7.72) | 19.92(13.51) | 15.48(9.41) | 14.591⁎⁎⁎ | 0.253 | 0.223 | 0.005 |

| Family empowerment (FES) | 4.382⁎⁎ | 0.243 | 0.383 | 0.027 | ||||

| Family | 39.95(5.63) | 43.79(5.99) | 36.64(8.15) | 39.68(6.43) | 12.124⁎⁎⁎ | 0.220 | 0.164 | 0.004 |

| Service system | 40.50(5.67) | 41.84(4.98) | 37.04(8.30) | 38.04(8.65) | 1.854 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.001 |

| Community/political | 26.85(6.36) | 29.05(5.61) | 22.20(7.04) | 22.84(7.24) | 3.460 | 0.074 | 1.046 | 0.024 |

| Global scale | 107.30(14.44) | 114.68(13.71) | 95.88(21.11) | 100.56(19.52) | 7.218⁎⁎ | 0.144 | 0.363 | 0.008 |

| Family global functioning (FAD-GFS) | 2.309⁎ | 0.345 | 1.227 | 0.219 | ||||

| Affective involvement | 13.75(3.26) | 12.79(2.65) | 16.17(3.27) | 15.75(2.89) | 2.323 | 0.052 | 0.362 | 0.009 |

| General functioning | 26.65(5.71) | 22.64(5.29) | 29.29(5.76) | 28.71(4.87) | 8.956⁎⁎ | 0.176 | 4.988⁎ | 0.106 |

| Total | 133.70(15.87) | 120.92(16.27) | 144.00(18.80) | 137.92(14.06) | 14.886⁎⁎⁎ | 0.261 | 0.178 | 0.043 |

| Quality of life (QLI) | 63.70(13.31) | 70.95(13.90) | 61.04(16.05) | 66.46(14.74) | 13.025⁎⁎⁎ | 0.237 | 2.72 | 0.006 |

Note: FC = Family Connections; BAS = Burden assessment Scale; DASS-21 = Depression, anxiety, and stress scale; FES = Family empowerment scale; FAD-GFS = Family assessment device – global functioning scale; QLI = Quality of life index.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

As Table 3 shows, separate univariate ANOVAs of each subscale revealed that improvements were found in the following primary outcomes on the BAS subscales: objective burden (F (1,43) = 13.453, p = .001), subjective burden (F (1,43) = 9.732, p = .003), limitations on personal activity (F (1,43) = 14.301, p = .000), negative effects on social interactions (F (1,43) = 4.996, p = .031), and the global scale (F (1,43) = 13.695, p = .001); and on the DASS-21 subscales: depression (F (1,43) = 12.036, p = .001), stress (F (1,43) = 15.753, p = .000), and total score (F (1,43) = 14.591, p = .000). Regarding the secondary outcomes, there were improvements on the following FES subscales after the intervention: family (F (1,43) = 12.124, p = .001) and global scale (F (1,43) = 7.218, p = .010); there were also improvements on some FAD-GFS subscales: general functioning (F (1,42) = 8.956, p = .005) and global scale (F (1,42) = 14.866, p = .000). Moreover, there was an improvement on the QLI (F (1,42) = 13.025, p = .001). However, no significant improvements were found on resentment (BAS) (F (1,43) = 3.658, p = .062), anxiety (DASS-21) (F (1,43) = 3.564, p = .066), service system (FES) (F (1,43) = 1.854, p = .180), community (FES) (F (1,43) = 3.460, p = .070), or affective involvement (FAD-GFS) (F (1,43) = 2.323, p = .135). Furthermore, separate univariate ANOVAs only revealed significant group effects on general functioning (FAD-GFS), where family members in the face-to-face format showed a further statistically significant improvement compared to the online format (F (1,42) = 4.988, p = .031).

As indicated above, an attempt was made to obtain more information about the degree of satisfaction with the online intervention from the groups that took part in the online format in the second year. Regarding the opinions of family members who participated in the online format, 31.82% of them would repeat the online intervention or recommend this format, whereas 27.27% would prefer the face-to-face intervention group or recommend this format. The rest of the family members would participate in FC in either format (31.81%) or in a blended format that included face-to-face and online sessions (9.1%), and they would also recommend them indistinctly (36.36%) or in a blended format (4.55%).

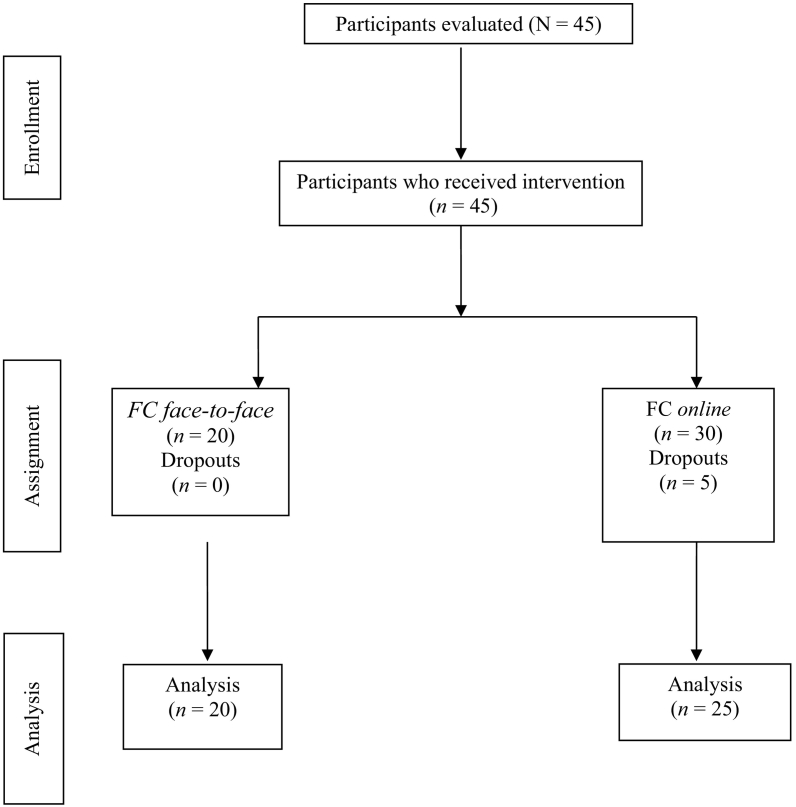

Finally, the number of dropouts was registered, based on attending less than 80% of the sessions. In the face-to-face FC condition, one group with 8 participants, and one group of 12 participants were conducted. In the online FC condition, there were one group of 11 people and two groups of 12 participants. In these groups there were a total of 5 dropouts. Groups were held both in the mornings and afternoons so that families' scheduling needs could be met. As Fig. 2 shows, in the online format, there were five dropouts, whereas in the face-to-face format, there were no dropouts. When they were asked for their reasons, they stated that it was because of their personal situation and that they would like to attend the intervention again in future editions.

Fig. 2.

Sample evolution throughout intervention.

Note: FC = Family Connections.

4. Discussion

The main objectives of this study were to assess, in a pragmatic pilot study, the effectiveness of FC implemented in an online format in a sample of family members of people with personality disorder, compared to the same protocol carried out face-to-face, and study the acceptability of the online delivery format.

Regarding the first study objective, to analyze the differences before vs after the intervention, family members experienced improvements in the primary outcomes of both constructs: burden and depression, anxiety, and stress. This result is in line with those obtained in other studies that assessed FC in a face-to-face format. Specifically, the studies found a significant reduction in burden (Flynn et al., 2017; Fonseca-Baeza et al., 2020; Hoffman et al., 2005, Hoffman et al., 2007; Liljedahl et al., 2019; Neiditch, 2010), anxiety, and stress (Fonseca-Baeza et al., 2020). Some studies found improvements in depression levels (Flynn et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2007; Neiditch, 2010), whereas others reported no changes (Hoffman et al., 2005). Regarding online interventions for family members of patients with BPD, Kindred was effective in reducing burden and stress levels (Gleeson et al., 2020), and other interventions or smartphone apps for family members of patients with other mental disorders were helpful in reducing stress (Fuller-Tyszkiewicz et al., 2020; Gleeson et al., 2017) or depression (Fuller-Tyszkiewicz et al., 2020), but not anxiety (Fuller-Tyszkiewicz et al., 2020; Gleeson et al., 2017). Due to the inconsistent results, further research is needed to determine the influence of these interventions on the burden and anxious-depressive symptomatology of family members.

Focusing on the secondary outcomes, family members improved their levels of empowerment, family functioning, and quality of life. Other FC studies also found an increase in the empowerment level (Neiditch, 2010), as did other face-to-face interventions for family members of patients with BPD (Bateman and Fonagy, 2018; Grenyer et al., 2018). Empowerment experienced by family members of patients with PD is severely impaired, ranking significantly below other groups of family members (Bailey and Grenyer, 2013). They attribute this deficiency to the absence of skills that would help them to control the circumstances of their lives, even though they would like to be able to rely on their skills to appropriately care for the patients (Kay et al., 2018). In this regard, FC has been shown to be effective (Hoffman et al., 2005, Hoffman et al., 2007).

In relation to family functioning, in general the results of the FC studies show an improvement in family functioning (Flynn et al., 2017; Liljedahl et al., 2019). Other face-to-face studies also show an improvement in family functioning (Bateman and Fonagy, 2018; Grenyer et al., 2018; C. R. Wilks et al., 2016), and online interventions for family members of persons with BPD have found a significant improvement in family interactions (Gleeson et al., 2020). Proper family functioning is essential, especially in families where there are individuals with PD, because the self-destructive behaviors they often engage in have a direct influence on the family system, interfering with its dynamics (Marco-Sánchez et al., 2020). Improving family functioning is, therefore, an essential part of these interventions.

Regarding quality of life, only two studies have assessed the effectiveness of FC in increasing quality of life – showing no change (Liljedahl et al., 2019; Rajalin et al., 2009), whereas one online-intervention, Kindred, increased it (Gleeson et al., 2020). Quality of life is a multidimensional construct that comprises objective descriptors and subjective evaluations of physical, material, social, and emotional wellbeing (Felce and Perry, 1995), areas that are affected in these family members (e.g., Kay et al., 2018; de Mendieta et al., 2019). The need to improve them is reflected in the new randomized control trial protocols (Betts et al., 2018; Fernández-Felipe et al., 2020).

Regarding the comparison of the two intervention formats, results indicate that there are no differences between face-to-face and online formats. This is the first study to compare the effectiveness of Family Connections in these two different delivery formats. We believe this study makes a great contribution, given that family members or even therapists are often more reluctant to carry out online interventions. However, this work shows that an online intervention can be just as effective as a face-to-face intervention on all its variables (burden, and depression, anxiety, and stress; and the level of empowerment, family functioning, and quality of life). Today, since the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the enormous growth in the morbidity of mental disorders, a radical change is taking place in our society and health systems. The need to generate online health therapies has been highlighted in the context of the pandemic (Shore et al., 2020), due to the strict need to limit personal contact and reach everyone who needs help and in places where it would otherwise not be feasible.

However, during a pandemic, when mental health problems are increasing exponentially, it is essential to explore other ways of providing professional help to all those in need. Thus, analyzing the effectiveness of face-to-face interventions and comparing them with an online format can be extremely valuable. It may be more efficient to change an empirically validated intervention from a face-to-face format to an online format until new Internet-based interventions can be developed and validated.

In relation to the third objective of this study, it should be noted that this was not an initial objective when we began the study. However, as the pandemic began and the interventions had to be adapted, there was some initial reluctance to continue with the online groups, both from the family members who were going to receive the intervention and from the therapists and co-therapists. For this reason, we decided that it would be relevant to try to collect information and analyze the opinions of the groups that participated in the online format. However, it was not possible to collect this information in the face-to-face groups carried out during the first year because too much time had already passed. Regarding the information provided by family members in the online format, the second objective of the study, over 70% of the family members were satisfied with the online delivery format. They indicated that they found it useful and had felt comfortable and confident in the online intervention, suggesting high acceptability of the online format. This finding is in line with other studies conducted with patients with PD (Jacob et al., 2018; Köhne et al., 2020; Rizvi et al., 2011; van Dijk et al., 2020) or with relatives of patients with other mental disorders (Grové et al., 2016; Matar et al., 2018). This result is not unexpected given that the therapeutic alliance created in online interventions is roughly equivalent to the one created face-to-face (Berger, 2017). However, it is essential to study which variables have an influence on the therapeutic alliance and which family members will benefit most from interventions delivered in an online or face-to-face format.

Finally, in terms of dropout rates, no dropouts were recorded in the face-to-face format, whereas dropouts in the online format reached 16.67%. This level is considerably lower than what was found in other similar interventions for relatives, where dropout rates of around 29% were found (Flynn et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2005; Pearce et al., 2017; Rajalin et al., 2009; Regalado et al., 2011). Therefore, the dropout rates in both formats show, indirectly, the acceptability of FC by family members.

This study presents some limitations that should be noted. First, it is a pragmatic pilot study with a small overall sample of family members of people with personality disorders. The online sample was significantly younger and had achieved a higher educational level. It would be necessary to explore the possible differences between face-to-face vs online implementation formats in a larger sample, with groups matched on age and educational level, to confirm these results. Moreover, not all the personality disorder diagnoses were represented; nor were they distributed equally in the two groups. Participants who wanted to take part in the study were included in the study. A larger sample would have been desirable, although the global sample size in this study is similar to or larger than in other similar studies (Betts et al., 2018; Gleeson et al., 2020). Second, this is a modest pragmatic pilot study and participants were not randomly allocated to each treatment condition, but our study provides data about the feasibility of designing and conducting more methodologically sound studies, such as randomized controlled trial or non-inferiority trials which will require larger samples and more rigorous methodological controls. Furthermore, as noted above, the study was not designed from the outset in all its details, but due to the emergence of COVID, certain aspects of the trial were modified as it was being conducted. However, our study helps to answer a key question in pragmatic trials, namely, whether something can be done (Eldridge et al., 2016). Third, we used a per-protocol analysis comparing those patients who completed the treatment originally allocated, then our results provide a lower level of evidence than intention to treat analysis. Fourth, the study does not offer follow-up data to assess whether the changes produced are maintained over time. Thus, future research should carry out follow up studies of FC, where improvements in the use of the learned skills could occur after the intervention and continue to increase over time (Brown et al., 2019). In addition, there are other variables that could have moderated these results and were not considered, such as the severity of the patients or their treatments, whether they are living with the family members, or any online problems that arose, such as Internet outages.

5. Conclusion

The present pilot study provides relevant data about the possibility of implementing FC in a sample of family members of people with PD in an online format without losing its effectiveness. During the pandemic, and despite the initial reluctance of family members and the therapists to carry out the interventions online, this work shows the effectiveness of the results and the satisfaction of the family members. Offering online interventions represents a qualitative leap in terms of the possibility of reaching remote places, putting people with the same problem in contact in different parts of the world, and creating support networks to face the problem and share common solutions and tools. All of this represents a great step forward in terms of providing psychological treatment. This is especially relevant in cases where face-to-face interactions are not possible or appropriate, such as the social and health situation resulting from SARS-CoV-2. In the future, other forms of online interventions should be designed and tested, including those that use evidence-based intervention protocols that are manualized and ready to be applied online with varying degrees of support from clinicians. In any case, to advance in this line of knowledge, it is necessary to carry out studies with greater methodological rigor in order to obtain firmer conclusions about the efficacy and clinical usefulness of Internet-based interventions for family members of patients with PD.

Funding

This study is partially funded by the Generalitat Valenciana, Consellería de Innovación, Ciencia y Sociedad Digital: Subvenciones para Grupos de Investigación Consolidables – AICO/2021– and the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades by means of an FPU grant (FPU15/07177) awarded to the second author.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Acres K., Loughhead M., Procter N. Australasian Emergency Care. Vol. 22. Elsevier; Australia: 2019. Carer perspectives of people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder: a scoping review of emergency care responses; pp. 34–41. Issue 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Diagnostic And Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- Bailey R.C., Grenyer B.F.S. Burden and support needs of carers of persons with borderline personality disorder: a systematic review. Harv.Rev.Psychiatry. 2013;21(5):248–258. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0b013e3182a75c2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey R.C., Grenyer B.F.S. Supporting a person with personality disorder: a study of carer burden and well-being. J. Personal. Disord. 2014;28(6):796–809. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Fonagy P. A randomized controlled trial of a mentalization-based intervention (MBT-FACTS) for families of people with borderline personality disorder. Personal.Disord. 2018;10(1):70–79. doi: 10.1037/per0000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett C., Melvin G.A., Quek J., Saeedi N., Gordon M.S., Newman L.K. Perceived invalidation in adolescent borderline personality disorder: an investigation of parallel reports of caregiver responses to negative emotions. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2019;50(2):209–221. doi: 10.1007/s10578-018-0833-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger T. The therapeutic alliance in internet interventions: a narrative review and suggestions for future research. Psychother. Res. 2017;27(5):511–524. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2015.1119908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts J., Pearce J., McKechnie B., McCutcheon L., Cotton S.M., Jovev M., Rayner V., Seigerman M., Hulbert C., McNab C., Chanen A.M. A psychoeducational group intervention for family and friends of youth with borderline personality disorder features: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Borderline Personal.Disord.Emot.Dysregulation. 2018;5(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s40479-018-0090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjureberg J., Sahlin H., Hedman-Lagerlöf E., Gratz K.L., Tull M.T., Jokinen J., Hellner C., Ljótsson B. Extending research on Emotion Regulation Individual Therapy for Adolescents (ERITA) with nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: open pilot trial and mediation analysis of a novel online version. In. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1885-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum N., Pfohl B., St. John D., Monahan P., Black D.W. STEPPS: a cognitive-behavioral systems-based group treatment for outpatients with borderline personality disorder - a preliminary report. Compr. Psychiatry. 2002;43(4):301–310. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.33497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T.A., Cusack A., Anderson L., Reilly E.E., Berner L.A., Wierenga C.E., Lavender J.M., Kaye W.H. Early versus later improvements in dialectical behavior therapy skills use and treatment outcome in eating disorders. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2019;43(4):759–768. doi: 10.1007/s10608-019-10006-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caballo V.E. Editorial Síntesis; 2009. Manual de trastornos de la personalidad. Descripción, evaluación y tratamiento. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H., Batterham P.J., O’Dea B. E-health interventions for suicide prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2014;11(8):8193–8212. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110808193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk S.D.M., Bouman R., Folmer E.H., den Held R.C., Warringa J.E., Marijnissen R.M., Voshaar R.C.O. (Vi)-rushed into online group schema therapy based day-treatment for older adults by the COVID-19 outbreak in the Netherlands. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2020;28(9):983–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl S., Idvall E., Perseius K.I. Family skills training in dialectical behaviour therapy: the experience of the significant others. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2014;28(4):235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge S.M., Lancaster G.A., Campbell M.J., Thabane L., Hopewell S., Coleman C.L., et al. Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual framework. PLoS One. 2016;11(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein N.B., Baldwin L.M., Obispo D.S. The McMaster family assessment device. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 1983;9(2):171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1983.tb01497.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felce D., Perry J. Quality of life: its definition and measurement. Res. Dev. Disabil. 1995;16(1):51–74. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(94)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Felipe I., Guillén V., Marco H., Díaz-García A., Botella C., Jorquera M., Baños R., García-Palacios A. Efficacy of “Family Connections”, a program for relatives of people with borderline personality disorder, in the Spanish population: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):302. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02708-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn D., Kells M., Joyce M., Corcoran P., Herley S., Suarez C., Cotter P., Hurley J., Weihrauch M., Groeger J. Family connections versus optimised treatment-as-usual for family members of individuals with borderline personality disorder: non-randomised controlled study. Borderline Personal.Disord.Emot.Dysregulation. 2017;4(18) doi: 10.1186/s40479-017-0069-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Baeza S., Guillén Botella V., Salvador Marco H., Fernández I., Díaz A., García-Palacios, Azucena Botella C., Baños Rivera R.M. Revista digital del 1er Congreso Internacional Virtual de ISEP: “La psicología de hoy: nuevas competencias y herramientas en tiempo de crisis. ISEP Editorial; 2020. Implementación de “Family Connections” en una asociación de familiares de personas con trastorno de personalidad; pp. 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Frías Á., Solves L., Navarro S., Palma C., Farriols N., Aliaga F., Hernández M., Antón M., Riera A. Technology-based psychosocial interventions for people with borderline personality disorder: a scoping review of the literature. Psychopathology. 2020;53(5–6):254–263. doi: 10.1159/000511349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M., Richardson B., Little K., Teague S., Hartley-Clark L., Capic T., Khor S., Cummins R.A., Olsson C.A., Hutchinson D. Efficacy of a smartphone app intervention for reducing caregiver stress: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment.Health. 2020;7(7) doi: 10.2196/17541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson J., Lederman R., Herrman H., Koval P., Eleftheriadis D., Bendall S., Cotton S.M., Alvarez-Jimenez M. Moderated online social therapy for carers of young people recovering from first-episode psychosis: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1775-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson J., Alvarez-Jimenez M., Betts J.K., McCutcheon L., Jovev M., Lederman R., Herrman H., Cotton S.M., Bendall S., McKechnie B., Burke E., Koval P., Smith J., D’Alfonso S., Mallawaarachchi S., Chanen A.M. A pilot trial of moderated online social therapy for family and friends of young people with borderline personality disorder features. Early Interv. Psychiatry. 2020;(July):1–11. doi: 10.1111/eip.13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer H., Cohen J.N. Partners of Individuals with borderline personality disorder. Harv.Rev.Psychiatry. 2018;26(4):185–200. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenyer B.F.S., Bailey R.C., Lewis K.L., Matthias M., Garretty T., Bickerton A. A randomized controlled trial of group psychoeducation for carers of persons with borderline personality disorder. J. Personal. Disord. 2018;33(2):1–15. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2018_32_340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grové C., Reupert A., Maybery D. The perspectives of young people of parents with a mental illness regarding preferred interventions and supports. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016;25(10):3056–3065. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0468-8. 18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guillén V., Marco Salvador J.H., Jorquera Rodero M., Bádenes L., Roncero Sanchís M., Baños Rivera R. Who cares for the caregiver? Treatment for family members of people with eating disorders and personality disorders. Informació Psicològica. 2018;116:65–78. doi: 10.14635/IPSIC.2018.116.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guillén V., Díaz-García A., Mira A., García-Palacios A., Escrivá-Martínez T., Baños R., Botella C. Interventions for family members and carers of patients with borderline personality disorder: a systematic review. Fam. Process. 2020 doi: 10.1111/famp.12537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick S., Yuen H.P., Cox G., Bendall S., Yung A., Pirkis J., Robinson J. Does cognitive behavioural therapy have a role in improving problem solving and coping in adolescents with suicidal ideation? Cogn.Behav.Ther. 2014;7 doi: 10.1017/S1754470X14000129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P.D., Buteau E., Hooley J.M., Fruzzetti A.E., Bruce M.L. Family members' knowledge about borderline personality disorder: correspondence with their levels of depression, burden, distress, and expressed emotion. Fam. Process. 2003;42(4):469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P.D., Fruzzetti A.E., Buteau E., Neiditch E.R., Penney D., Bruce M.L., Hellman F., Struening E. Family connections: a program for relatives of persons with borderline personality disorder. Fam. Process. 2005;44(2):217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P.D., Fruzzetti A.E., Buteau E. Understanding and engaging families: an education, skills and support program for relatives impacted by borderline personality disorder. J. Ment. Health. 2007;16(1):69–82. doi: 10.1080/09638230601182052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iliakis E.A., Sonley A.K.I., Ilagan G.S., Choi-Kain L.W. Treatment of borderline personality disorder: is supply adequate to meet public health needs? Psychiatr. Serv. 2019;70(9):772–781. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob G.A., Hauer A., Köhne S., Assmann N., Schaich A., Schweiger U., Fassbinder E. A schema therapy-based eHealth program for patients with borderline personality disorder (priovi): naturalistic single-arm observational study. JMIR Ment.Health. 2018;5(4) doi: 10.2196/10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay M.L., Poggenpoel M., Myburgh C.P., Downing C. Experiences of family members who have a relative diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Curationis. 2018;41(1):1–9. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v41i1.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A.E., Siegel T.C., Bass D. Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1992;60(5):733–747. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg S.H., Young J.E. In: Twenty-first Century Psychotherapies: Contemporary Approaches to Theory And Practice. Lebow Jay L., editor. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, West Sussex; Hoboken, NJ: 2008. Cognitive therapy; pp. 43–79. ISBN 9780471752233. OCLC 123332183. [Google Scholar]

- Köhne S., Schweiger U., Jacob G.A., Braakmann D., Klein J.P., Borgwardt S., Assmann N., Rogg M., Schaich A., Faßbinder E. Therapeutic relationship in ehealth–a pilot study of similarities and differences between the online program priovi and therapists treating borderline personality disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(17):1–15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren P.E., DeChillo N., Friesen B.J. Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: a brief questionnaire. Rehabil.Psychol. 1992;37(4):305–321. doi: 10.1037/h0079106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.H., Maniam T., Chan L.F., Ravindran A.V. Caught in the web: a review of web-based suicide prevention. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederman R., Wadley G., Gleeson J.F., Bendall S., Alvarez-Jimenez M. Moderated online social therapy: designing and evaluating. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum.Interact. 2014;2:1–27. doi: 10.1145/2513179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger M.F., Lane M.C., Loranger A.W., Kessler R.C. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K.L., Fanaian M., Kotze B., Grenyer B.F.S. Mental health presentations to acute psychiatric services: 3-year study of prevalence and readmission risk for personality disorders compared with psychotic, affective, substance or other disorders. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(1) doi: 10.1192/bjo.2018.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S.P., Heath N.L., Michal N.J., Duggan J.M. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. Vol. 6. 2012. Non-suicidal self-injury, youth, and the Internet: what mental health professionals need to know. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljedahl S.I., Kleindienst N., Wångby-Lundh M., Lundh L.-G., Daukantaitė D., Fruzzetti A.E., Westling S. Family connections in different settings and intensities for underserved and geographically isolated families: a non-randomised comparison study. Borderline Personal.Disord.Emot.Dysregulation. 2019;6(14):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40479-019-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond S., Lovibond P. 2nd edition. Psychology Foundation; 1995. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. [Google Scholar]

- Madriz E. In: Handbook of Qualitative Research. Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S., editors. Sage Publications; 2000. Focus groups in feminist research; pp. 835–850. [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Sánchez S., Mayoral-Aragón M., Valencia-Agudo F., Roldán-Díaz L., Espliego-Felipe A., Delgado-Lacosta C., Hervás-Torres G. Funcionamiento familiar en adolescentes en riesgo de suicidio con rasgos de personalidad límite: un estudio exploratorio. Rev.Psicol.Clín.Con NiñosAdolesc. 2020;7(2):50–55. doi: 10.21134/rpcna.2020.07.2.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matar J.L., Maybery D.J., McLean L.A., Reupert A. Web-based health intervention for young people who have a parent with a mental illness: Delphi study among potential future users. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20(10) doi: 10.2196/10158. Oct 31 https://www.jmir.org/2018/10/e10158/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mendieta C., Robles R., González-Forteza C., Arango I., Pérez-Islas C., Vázquez-Jaime B.P., Rascón M.L. Needs assessment of informal primary caregivers of patients with borderline personality disorder: psychometrics, characterization, and intervention proposal. Salud Mental. 2019;42(2):83–90. doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2019.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzich J.E., Ruipérez M.A., Pérez C., Yoon G., Liu J., Mahmud S. The Spanish version of the quality of life index: presentation and validation. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2000;188(5):301–305. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M.L., Skerven K. Family skills: a naturalistic pilot study of a family-oriented dialectical behavior therapy program. CoupleFam.Psychol.Res.Pract. 2017;6(2):79–93. doi: 10.1037/cfp0000076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council . National Health and Medical Research Council; 2012. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Borderline Personality Disorder. [Google Scholar]

- Neiditch E.R. St. John's University; 2010. Effectiveness And Moderators of Improvement in a Family Education Program for Borderline Personality Disorder. [Google Scholar]

- Newton-Howes G., Cunningham R., Atkinson J. Personality disorder prevalence and correlates in a whole of nation dataset. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01876-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paldam A., Mathiasen K., Lauridsen S.M., Stenderup E., Dozeman E., Folker M.P. Implementing internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for common mental health disorders: a comparative case study of implementation challenges perceived by therapists and managers in five European internet services. Internet Interv. 2018;11(January):60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce J., Jovev M., Hulbert C., Mckechnie B., Mccutcheon L., Betts J., Chanen A.M. Evaluation of a psychoeducational group intervention for family and friends of youth with borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personal.Disord.Emot.Dysregulation. 2017;4(5):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s40479-017-0056-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plana-Ripoll O., Pedersen C.B., Holtz Y., Benros M.E., Dalsgaard S., de Jonge P., Fan C.C., Degenhardt L., Ganna A., Greve A.N., Gunn J., Iburg K.M., Kessing L.V., Lee B.K., Lim C.C.W., Mors O., Nordentoft M., Prior A., Roest A.M., Saha S., Schork A., Scott J.G., Scott K.M., Stedman T., Sørensen H.J., Werge T., Whiteford H.A., Laursen T.M., Agerbo E., Kessler R.C., Mortensen P.B., McGrath J.J. Exploring comorbidity within mental disorders among a Danish national population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):259. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajalin M., Wickholm-Pethrus L., Hursti T., Jokinen J. Dialectical behavior therapy-based skills training for family members of suicide attempters. Arch.Suicide Res. 2009;13(3):257–263. doi: 10.1080/13811110903044401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathus J.H., Miller A.L. Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. SuicideLifethreatening Behav. 2002;32(2):146–157. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.2.146.24399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regalado P., Pechon C., Stoewsand C., Gagliesi P. Familiares de personas con Trastorno Límite de la Personalidad: estudio pre-experimental de una intervención grupal. Rev.Argent.Psiquiat. 2011;22:245–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard S.C., Gubman G.D., Horwitz A.V., Minsky S. Burden assessment scale for families of the seriously mentally ill. Eval.Program Plan. 1994;17(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(94)90004-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riper H., Blankers M., Hadiwijaya H., Cunningham J., Clarke S., Wiers R., Ebert D., Cuijpers P. Effectiveness of guided and unguided low-intensity internet interventions for adult alcohol misuse: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi S.L., Dimeff L.A., Skutch J., Carroll D., Linehan M.M. A pilot study of the DBT coach: an interactive mobile phone application for individuals with borderline personality disorder and substance use disorder. Behav. Ther. 2011;42(4):589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J., Hetrick S., Cox G., Bendall S., Yung A., Yuen H.P., Templer K., Pirkis J. The development of a randomised controlled trial testing the effects of an online intervention among school students at risk of suicide. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):155. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J., Hetrick S., Cox G., Bendall S., Yuen H.P., Yung A., Pirkis J. Can an internet-based intervention reduce suicidal ideation, depression and hopelessness among secondary school students: results from a pilot study. Early Interv.Psychiatry. 2016;10(1):28–35. doi: 10.1111/eip.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M.A.M., Lemmen K., Kramer R., Mann J., Chopra V. Internet-delivered health interventions that work: systematic review of meta-analyses and evaluation of website availability. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017;19(3):1–28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban D.A., Muir J.A., Mena M.P., Mitrani V.B. Integrative borderline adolescent family therapy: meeting the challenges of treating adolescents with borderline personality disorder. <sb:contribution><sb:title>Psychotherapy Theory Res. Pract.</sb:title> </sb:contribution><sb:host><sb:issue><sb:series><sb:title>Train.</sb:title></sb:series></sb:issue></sb:host>. 2003;40(4):251–264. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.40.4.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban D.A., Mena M.P.D., Muir J., Mccabe B.E., Abalo C., Cummings A.M. The efficacy of two adolescent substance abuse treatments and the impact of comorbid depression: results of a small randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr. Rehabil.J.l. 2015;38(1):55–64. doi: 10.1037/prj0000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigerman M.R., Betts J.K., Hulbert C., McKechnie B., Rayner V.K., Jovev M., Cotton S.M., McCutcheon L., McNab C., Burke E., Chanen A.M. A study comparing the experiences of family and friends of young people with borderline personality disorder features with family and friends of young people with other serious illnesses and general population adults. Borderline Personal.Disord.Emot.Dysregulation. 2020;7(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s40479-020-00128-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore J.H., Schneck C.D., Mishkind M.C. Telepsychiatry and the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic—current and future outcomes of the rapid virtualization of psychiatric care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1211–1212. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland A.E., Stickland J., Wee B. Can video consultations replace face-to-face interviews? Palliative medicine and the Covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care. 2020;2020:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilks C.R., Korslund K.E., Harned M.S., Linehan M.M. Dialectical behavior therapy and domains of functioning over two years. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016;77:162–169. doi: 10.1016/J.BRAT.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry K.A., Popenoe E.J. Implementing dialectical behavior therapy with adolescents and their families in a community outpatient clinic. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2008;15(3):277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2007.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young J.E., Brown G. In: Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schemavan Focused Approach. 2nd ed. Young J.E., editor. Professional Resource Press; Sarasota: 1994. Young schema-questionnaire. [Google Scholar]