Abstract

In Saudi Arabia, the COVID-19 pandemic forced students with dyslexia to complete their learning through online applications, like their peers without dyslexia. This study explores the influence of assistive technology (AT) on improving the visual perception (VP) and phonological processing (PhP) abilities of students with dyslexia. Three learning applications were used (Google Classroom, Zoom, and Quizlet) as AT platforms. A quantitative approach was adopted based on a quasi-experimental design. Single-subject experimental methods were used to examine the influence of AT on improving students’ VP, PhP, and frequency of access (FA). Fourteen students with dyslexia who were selected as participants through purposeful sampling were divided into two experimental groups based on gender. The results showed that AT influenced the VP, PhP, and FA in both experimental groups. Girls scored higher than boys in VP, PhP, and FA, and a positive correlation was found between VP and PhP with AT applications among girls and boys. A simple linear regression analysis showed that a significant and positive relationship exists between FA and the VP and PhP abilities of students with dyslexia through AT applications.

Keywords: Assistive technology, Students with dyslexia, Visual perception, Phonological processing, Language disabilities

Introduction

Dyslexia refers to impairments in the recognition, decoding, spelling, and reading of words (Smirni et al., 2020). Studies in the neuropsychological and cognitive fields have confirmed that two mental functions are involved in the process of recognizing written words (Cheng et al., 2021; Dobson, 2019): phonological function and visual recognition. The phonological function is represented by the use of phonemic transliteration, which is known as phonological processing (PhP), while the visual function is applied through the visual recognition of written units, known as visual perception (VP) (Zhao et al., 2018). Both functions are necessary from the early stages of reading acquisition, when the child can recognize the representative value of writing symbols, and the act of learning reinforces the link between letters and the corresponding phonemes (Cai et al., 2020). Thus, works to create conversion rules by keeping the visual-space properties in memory for these Biblical symbols (Cai et al., 2020). As the acquisition process progresses, the lexical path begins to be employed. In this path, reading involves recognizing the lexical representations of words based on some of their written characteristics (Wang & Bi, 2022). Moreover, the results of related studies have confirmed the link between reading acquisition and PhP. Whereas reading is based on the construction of a literal phonological correspondence between the auditory units and the written and visual written units (Zhao et al., 2018). The link between phonological ability and visual ability appears in the results of comparative studies between normal and dyslexic readers; however, phonological ability is not limited as one of the primary acquisitions necessary for the phonemic link (Smirni et al., 2020). It is a manifestation of the ability to decode the relationship between the represented element and the sounds that are the subject of representation in a linear way (Smirni et al., 2020). Thus, difficulty in reading occurs because of a defect in double decoding, which requires an ability to decode the phonetic encoding and the mental image of the word (Smirni et al., 2020; Wang & Bi, 2022; Zhao et al., 2018).

In this context, many studies have emphasized that dyslexia causes disorders in both VP and PhP (Ali et al., 2021; Johnston et al., 2017), which leads to difficulties in recognizing letters and words (Yang et al., 2021). Van der Kleij et al. (2019) noted that VP and PhP have crucial impacts on the reading ability of Dutch children with dyslexia and emphasized the importance of VP and PhP in remediating the accuracy This means that in the upper grades, children with dyslexia struggle to perform fluent and accurate reading in Dutch orthography. Before embarking on the process of acquiring writing and reading skills, dyslexic students perform poorly in PhP, as they have reading difficulties and need assistance to acquire lexical knowledge (Muyassaroh & Kamala, 2021; Yang et al., 2021).

Students suffering from dyslexia are poor at pseudo-word reading and non-word repetition. They find it difficult to name objects, they have poor short-term memory and poor phonemic awareness, and they lack phonological cues in verbal memory tasks (Pelleriti, 2018). Moreover, dyslexic students are characterized by difficulties in revitalizing and retrieving previous knowledge about reading, so they experience significant difficulties at the level of comprehension (Zhao et al., 2018). By contrast, the average (or good) reader shows greater abilities not only in the varied use of reading strategies according to the discourse style of the text being read but also in the awareness and explicit expression of these strategies and the application of prior knowledge (Zhao et al., 2018). Students with dyslexia are also characterized by some general symptoms, such as difficulty learning the alphabet; difficulty linking sounds and the letters that represent them; difficulty identifying or generating rhymed words or counting syllables in words; difficulty dividing words into individual sounds or mixing sounds to make words; difficulty retrieving a word or naming problems; difficulty learning to decode words, and thus confusing opposite words such as before/after, right/left, above/below; and difficulty distinguishing between similar sounds in words or mixing sounds in the pronunciation of multi-syllable words (Chen et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2021). Therefore, this study investigates how AT can contribute to improving students’ PhP and VP, which are responsible for the occurrence of dyslexia.

A review of existing studies showed that few studies have investigated the use of AT for dyslexic students or examined dyslexic students in the early stages of learning, as more research has focused on dyslexia among adults. Considering the negative influence of dyslexia if left untreated, many studies (Abu-Keshk & Kürüm, 2021; Dawson et al., 2019; Rasheed-Karim, 2021) stated that dyslexic students who did not receive a reading intervention to remediate their reading difficulties at the VP and PhP levels suffer more intense consequences of dyslexia at higher levels of education. While many studies have examined dyslexia in Arabic students (Aldabaybah & Jusoh, 2018; Arifa, 2021; El Kah & Lakhouaja, 2018; Gharaibeh, 2021; Rabia & Wattad, 2022; Schiff & Saiegh-Haddad, 2017), they did not examine the influence of AT on dyslexic students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Benmarrakchi et al. (2017) emphasized the importance of the factors that are considered inherent in Arabic to meet the needs of dyslexic students, such as the similarity of some letters in writing and orthography, and the rule of ICT technology and its crucial benefits for dyslexic students, which matches their learning style.

Furthermore, students with dyslexia need special support to achieve their educational goals appropriately and satisfactorily (Zawadka et al., 2021). Such support includes receiving specific teaching and learning activities and using compensatory strategies and tools according to their specific needs and the nature of their learning (Hebebci et al., 2020). Hence, their educational needs require continuous and systematic care (Zawadka et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic, which has become a tangible reality in daily life activities, has increased the vulnerability of students with dyslexia due to the consequences of school closures and increased educational losses (Yan et al., 2021). The suspension of daily school activities that were previously available to them affected their ability to acquire reading skills. Those activities that aided the development of VP and PhP are now provided without the associated support (Petretto et al., 2020). Since the formal education of students who do not have any kind of disability has shifted to digital platforms and applications forcibly, attention was naturally drawn to how these applications contribute to helping students with dyslexia overcome their problems (Smith & Hattingh, 2020). AT applications can be used to improve the development of both VP and PhP for these students (Chanioti, 2017).

The pandemic has created learning difficulties for all students through the necessity to adapt technology to overcome the problems resulting from the school closures. According to Forteza-Forteza et al. (2021), technological resources should be used to enhance learning processes as part of the basic standards for teaching and classroom practice. Moreover, several studies have revealed the negative impact of the closures on psychological, emotional, and cognitive aspects, as well as on certain types of learning (Hebebci et al., 2020; Daniel, 2020). These difficulties have had a greater effect on special groups, such as students with dyslexia, who have been most affected by this crisis (Soriano-Ferrer et al., 2021). According to the parents of students with dyslexia, these students also showed greater social isolation (Sarti et al., 2021). Also, the continued school closures will have increased consequences for the learning potential of students with dyslexia (Baschenis et al., 2021). Therefore, specific technological interventions should be accelerated to reduce the risks and negative effects on global development (Zhang et al., 2021). Therefore, this study investigates the use of AT in teaching Arabic by targeting dyslexic students in grade three in Saudi Arabia. The study was conducted among two experimental groups comprising dyslexic students divided based on gender. This study investigated the influence of AT applications during the COVID-19 pandemic on the VP, PhP, and frequency of access (FA) of dyslexic students. FA refers to the frequency that students have access to the AT applications.

Literature review

In this section, Sect. 2.1 discusses the findings of existing studies on the dyslexia phenomenon in relation to VP and PhP, Sect. 2.2 examines the influence of AT on dyslexia, Sect. 2.3 discusses the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Sect. 2.4 describes the problem under study, as well as the related research questions and hypotheses.

Dyslexia

Dyslexia is a neurodevelopmental disorder, resulting in a weakness to read words despite having good levels of intelligence and education and an acceptable socioeconomic level background (Soriano-Ferrer et al., 2021). Dyslexia is one of the most common learning disorders and affects the academic performance of 5%–10% of students worldwide (Wang & Bi, 2022). At a time when literacy has been prioritized as a prerequisite for alleviating global problems such as poverty, dyslexia has emerged as a major impediment to its realization (Gosse and Van Reybroeck, 2020). PhP and VP influence dyslexia word (Smirni et al., 2020). Language development occurs at a very young age among children, emphasizing the need for appropriate language development strategies at the elementary school level (Wang & Bi, 2022). As children develop language and sound detection abilities from a young age, teachers must identify students with specific learning difficulties and use appropriate learning strategies to enhance their VP and PhP (Afonso et al., 2020). Su et al. (2018) highlighted that teaching in any ordinary classroom entails handling all kinds of students, including those with dyslexia, who find it difficult to develop cognitive abilities and reading-related skills. As a result, students end up experiencing difficulties in VP and PhP, which can cause them to perform poorly, unlike their non-dyslexic counterparts. Therefore, to improve the performance of students with dyslexia, teachers must embrace strategies to enhance the VP and PhP levels of their students. Van der Kleij et al. (2019) stated that students with dyslexia find it difficult to spell and decode words correctly. According to them, students with these challenges constituted about 5%–17% of the total student population in the United States (Van der Kleij et al., 2019). The same challenge affects a significant number of elementary students from various parts of the world. The next section discusses the visual and phonological theories that have been used to explain dyslexia from the perspectives of VP and PhP.

Visual perception & phonological processing

Dyslexia is considered to be a VP impairment that causes people to experience difficulties in processing words and letters on a page of text. Verhoeven et al. (2019) argued that dyslexic individuals have VP challenges characterized by increased visual crowding, poor vergence, and unstable binocular fixations. Zhang et al. (2021) pointed out that, at the biological level, the visual system is divided into parvocellular and magnocellular pathways, and each pathway has varied roles and properties. For instance, the magnocellular pathway is disrupted selectively among dyslexic individuals, which causes deficiencies in the person’s VP and visuospatial attention, resulting in abnormal binocular control. Zhang et al. (2018) maintained that disruption of the magnocellular pathway, which is usually common among individuals with dyslexia, affects their VP. This disruption also causes abnormal processing of visual motion among dyslexic individuals. Thus, dyslexic children find it difficult to view texts and end up performing poorly in reading. The VP deficit is related to developmental dyslexia. Chen et al. (2019) stated that the VP plays a critical role in reading Chinese words and texts and extends far beyond many common reading skills. Poor VP is caused by the disruption of the magnocellular pathway in dyslexic students and affects their PhP (Cheng et al., 2021). Failure to recognize sight words and texts makes it difficult for them to read properly. Therefore, phonological and visual theories are relevant to the explanation of dyslexia from the perspectives of the VP and PhP. On the other hand, Gosse and Van Reybroeck (2020) claimed that dyslexia is a linguistic factor that affects an individual’s PhP. PhP refers to metalinguistic skills that help a child have conscious thoughts in a given language (Friantary et al., 2020). Van der Kleij et al. (2019) discovered that most apparent visual problems can be linked to language difficulties, especially PhP deficiencies. According to him, PhP refers to a person’s ability to determine the phonological or language structure and manifests in the ability to distinguish between units of speech, including individual phonemes in rhymes and syllables. A child’s PhP is determined by their ability to read and spell words correctly (Verhoeven et al., 2019). A child with poor phonological skills progresses poorly and is likely to be classified as dyslexic (Cheng et al., 2021). Cao et al. (2017) pointed out that phonological theory postulates that people with dyslexia have incapacities in the storage, representation, and retrieval of speech sounds. According to them, the ability to attend to and manipulate linguistic sounds is necessary, as it helps establish and automate the graphophonic relationship that underlies a person’s phonological and decoding skills (Cao et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2021). Because of the importance of these two factors in acquiring correct reading skills to reduce dyslexia, the current study investigates the influence of AT applications in improving both VP and PhP among students with dyslexia.

Furthermore, several related studies have dealt with the relationship between VP and PhP, and their influencing role in the phenomenon of dyslexia (Chen et al., 2019; Hebert et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018). Cheng et al. (2021) also discussed whether a VP deficit is independent of PhP in Chinese students’ developmental dyslexia. A group of 45 dyslexic Chinese aged between 8 and 11 years participated in this study. A model based on strings of letters and numbers, dots, and color codes was used to measure the extent of the students’ VP. The students’ PhP skills were measured in three dimensions: phonemic awareness, rapid automatic naming, and short-term verbal memory. The results showed that dyslexic children in China had deficits in VP span and all three dimensions of PhP skills. These results indicate that they are closely related to each other. Accordingly, the current study seeks to investigate the correlation between VP and PhP among students with dyslexia through AT applications.

The influence of AT on dyslexia

AT comprises equipment and software that can be used in full or in part to help people with disabilities. Two types of AT are aimed at people with dyslexia, the first of which facilitates access to learning and the production of learning materials with enhanced readability, including pen readers, audiobooks, alternative keyboards, optical character recognition, portable word processors, and variable-speed tape recorders (Jamaludin et al., 2018; Rauschenberger et al., 2019). The second type of AT is aimed at teaching literacy (e.g., Nessy, Touch-type Read, and Spell, or TTRS, GraphoGame, Lexercise Screener, and Lexa). This second is the focus of the current study, building on recent research and developments. Furthermore, the utilization of AT has played a major role in diagnosing and treating students with dyslexia. At the diagnostic level, Wang and Bi (2022) established an improved genetic algorithm-optimized back-propagation neural network model, laying the foundation for the artificial intelligence expert diagnosis system to predict whether Chinese children will have dyslexia, based on data from 399 children. The model achieved an overall prediction accuracy of about 94%. The model had excellent predictive power for Chinese children with or without developmental dyslexia. It also had the power to direct more targeted prevention and treatment strategies. At the study level, Gupta et al. (2021) designed a multi-platform augmented reality-based educational application called Augmentally to provide companionship in reading and learning everywhere for children with dyslexia. The results indicated that the application constituted a valuable solution for periodic reading activities for children who do not have easy access to educational specialists, in addition to being easy to deal with and low in cost. Buele et al. (2020) developed a 3D virtual system that allows a child diagnosed with dyslexia to complete activities performed in conventional therapy. To achieve this, the application consists of two games (each with three levels of difficulty). In each game, virtual objects are combined with auditory messages to provide the user with an immersive experience and to train more than one sense in a single activity. The children are asked to correctly locate the syllables that make up a word. This tool was tested by eight children, ages 8 to 12, with parental supervision allowed. The attached database also stores children’s responses for the specialist to deal with in the future. In addition, Burac and Cruz (2020) developed an educational application based on AT called IREAD to improve the reading skills of students with dyslexia through text-to-speech technology. The application relies on the method of repeated instruction for teaching by teachers and is based on web-based learning resource management. The usability assessment of the application was conducted based on the following dimensions: efficiency, quality of support, ease of use, and satisfaction. The results showed that the application supports an individualized learning style that provides fun and engaging learning activities. In addition, the application has a very positive overall usability. Alghabban et al. (2017) developed a mobile cloud computing system based on a multimodal interface tool, which could be customized to meet students’ learning styles, and found an improvement of almost 30% in students’ learning capabilities in Arabic. These findings demonstrate that AT can play a crucial role in addressing the effects of dyslexia on the learning output of students with this disability. Pirani and Sasikumar (2015) and Hall et al. (2015) developed a system to enhance reading abilities and learning among students with dyslexia based on the AT environment. Kumar and Karie (2014) developed a mobile platform for students with speech disabilities that converts pictures (input) to text, and then to sound (output) through an intelligent integral search engine. Fernández-López et al. (2013) proposed a mobile platform to cover learning exercises to improve students’ learning skills. Rekha et al. (2013) developed ReadAid, an application aimed at helping children with dyslexia improve their reading abilities and demonstrated its success in supporting the target group. AT-supported learning allows students to participate in the learning process, express their opinions freely, and share their knowledge on an equal basis (Al-Zoubi & Suhail, 2020; Smith & Hattingh, 2020; Yan et al., 2021). The introduction of AT significantly enhanced VP and PhP among elementary school students with specific learning difficulties, for example, by improving equality in the learning process (Borhan et al., 2018; Rajapakse et al., 2018). Like their peers without dyslexia, students with dyslexia have adequate time to study and acquire knowledge through AT, which enables them to go through class content and understand new concepts in their own time (Novembli & Azizah, 2019; Sajan et al., 2019). In this way, AT allows students with dyslexia to control and optimize their learning speeds (Novembli & Azizah, 2019; Thelijjagoda et al., 2019). These findings demonstrate that AT can play a crucial role in addressing the effects of dyslexia and the learning output of students with this disability.

During the pandemic

To contain the spread of the virus during the COVID-19 pandemic, nations embraced measures aimed at promoting social distancing, which included the closure of schools and the emergence of studying from home. To continue teaching, schools embraced the use of technology, whereby students attended classes via online platforms. This method of learning proved effective during the pandemic. However, this method has also proven effective in both assessment and training when applied in classrooms under normal circumstances for all students (Petretto et al., 2020). Furthermore, to reduce the negative effects of the pandemic, especially for dyslexic students, many worldwide associations have contributed to the learning field. Perhaps the most prominent of them is the British Dyslexia Association (BDA), which provides a helpful framework to identify learners with dyslexia and supports teachers with webinar training to make a dyslexia-friendly virtual school. While many strategies were developed to teach and assess students with dyslexia during the pandemic (Muyassaroh & Kamala, 2021), the fate of 5%–10% of students’, namely dyslexic students, remains unaddressed (Van der Kleij et al., 2019). This is a considerable number that must be factored in when drawing up learning programs to help realize literacy goals. It is thus imperative to evaluate the effect of AT on dyslexic students, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced the world to rely on technology.

Schools around the world have implemented academic modifications and accommodations relevant to assisting dyslexic students in attaining their learning goals. For instance, teachers give extra time to dyslexic students to finish their tasks and assist them in taking notes and modifying assignments (Alsswey et al., 2021). Therefore, most teachers have found it difficult to help dyslexic students who were used to special attention in the classroom during the pandemic. Learning from home makes it difficult for a teacher to determine whether the teaching methodology helps such students attain their learning needs (Ali et al., 2021). However, it is imperative for teachers to ensure that such students realize their learning goals (Muyassaroh & Kamala, 2021). Hence, as the world relies on technology, it is necessary to ensure that technology assists such students in achieving their learning needs (Alsswey et al., 2021). To do so, teachers should use AT, either hardware and software, or devices that can enhance a learner’s level of independence and productivity. To help such students improve their reading, spelling, and writing skills, it is imperative to use an AT that can enhance the student’s VP and PhP (Ali et al., 2021).

Several studies have been conducted to support students with dyslexia during the pandemic period (e.g., Arifa, 2021; Maggio et al., 2021; Shaw et al., 2022). These studies unanimously agree on the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and well-being of children with disabilities and their families, especially those with developmental dyslexia, and they recommend providing and supporting conscious post-disaster trauma treatment practices. Several researchers (Buele et al., 2020; Schiavo et al., 2021; Aldabaybah & Jusoh, 2018) have stated that these practices can be introduced intensively and consciously by transferring traditional learning strategies to applications and digital environments. Considering the features of these applications that support audiovisual learning (McNicholl et al., 2020; Schmitt et al., 2019), this study was conducted to employ the potential features and characteristics of AT applications to support students with dyslexia in developing their reading skills by improving VP and PhP. The study was conducted during the partial lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia between January 26 and June 22, 2021.

Problem under study

Dyslexia is a common disorder and is caused by many factors, such as environmental influences, emotional factors, and VP and PhP disorders. Dyslexia has different manifestations according to language. Therefore, it presents differently in English compared to Arabic (Alsswey et al., 2021; Gharaibeh, 2021; Rabia & Wattad, 2022). The Arabic alphabet consists of 28 letters, which represent 34 phonetics. There are 25 consonant letters and 3 vowel letters. The vowels may be short or long (Al-Zoubi & Suhail, 2020; El Kah & Lakhouaja, 2018). The most common symptoms of dyslexia, especially in Arabic, depend on two issues. First, for long vowels to be correctly represented to an Arabic reader, it is necessary to vocalize diacritics in pronunciation as well as in writing. The second issue relates to one or more diacritical marks, orthographs, and the shape of the letters, which result in incorrect spelling and mistakes in writing. In the Arabic language, there are 14 diacritical marks. For example, the letter “أ” (A), may have three forms of marks (إِ,أَ, and أُ), so each type has a specific phonetic (a, e, o). Further, there is a similarity in orthographs: the letter “س” (S), pronounced in Arabic as /seen/, has a similar orthograph to the letter “,ث, which is pronounced in Arabic as /Thaa/. The similarity among some letters in both orthograph and shape is a challenge for those who have dyslexia. These issues relate to impaired VP and PhP abilities. This study aims to use AT applications to improve these factors and reduce the severity of dyslexia among students. As AT applications can clarify Arabic language issues, they can improve both the readers’ VP and PhP using texts, images, videos, and animations.

The current study follows the abovementioned studies (Al Otaiba & Petscher, 2020; Khateri et al., 2021; Sasupilli et al., 2019; Smith & Hattingh, 2020), which highlighted the scarcity of research on the benefits of a computerized system for dyslexic students and fills the gap in research dealing with the relationship between AT and students with dyslexia. To compensate for this shortcoming and the suspension of conventional education with increasing reliance on learning applications during the pandemic, the authors present a procedural framework to employ AT applications that can enhance the VP and PhP of dyslexic students.

Research questions

This study aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What influence do AT applications have on the (a) VP, (b) PhP, and (c) FA of dyslexic students in Saudi Arabia during the pandemic, examining boys and girls separately.

RQ2: Does a correlation exist between dyslexic students’ VP and PhP after using the AT applications?

RQ3: Does the students’ FA to AT applications affect their VP?

RQ4: Does the students’ FA to AT applications affect their PhP?

Hypothesis

The current study investigates the influence of AT applications on dyslexic students in Arabic, a Semitic language, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many studies have explored the most common issues that Arabic speakers struggle with, such as diacritical marks, orthographs, and similar shapes (Abu-Rabia & Abu-Rahmoun, 2012; Al Rowais et al., 2013; Al-Zoubi & Suhail, 2020; El Kah & Lakhouaja, 2018; Gharaibeh, 2021), which are present in conjunction with VP and PhP. Dyslexia affects students’ VP and PhP (Ali et al., 2021; Johnston et al., 2017). Hebert et al. (2018) discussed the close interconnectedness between the VP and PhP and pointed out that PhP and VP ability highly depend on a child’s transcription skills.

Overall, dyslexic students need to develop their VP and PhP abilities so that they can easily grasp these concepts (Varga et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic imposed a new kind of learning on both dyslexic and non-dyslexic students, requiring the use of AT; therefore, teachers must use AT that adapts to the visual and phonological impairments of these students (Smith & Hattingh, 2020; Yan et al., 2021). Students benefit from specific AT applications to help them improve their pattern recognition and to properly identify existing similarities among multiple texts. Consequently, we are curious about the effectiveness of AT applications in enhancing students’ VP and PhP. Moreover, considering the valuable effects of AT for dyslexics (Buele et al., 2020; Burac and Cruz, 2020; Gupta et al., 2021), researchers have also questioned the influence of AT applications on FA and, from there, the extent of FA’s influence on VP and PhP. Therefore, the current study addresses the following research hypotheses (Table 1):

H1. No statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) exists in the VP of dyslexic students between the first (girls) and second experimental groups (boys) after using AT applications.

H2. No statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) exists in the PhP of dyslexic students between the first (girls) and the second experimental groups (boys) after using AT applications.

H3. No statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) exist in the FA of dyslexic students between the first (girls) and the second experimental groups (boys) after using AT applications.

H4. No statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) exist in the correlation coefficients for dyslexic students between VP and PhP for both experimental groups after using AT applications.

H5. The FA to AT applications does not affect students’ VP.

H6. The FA to AT applications does not affect students’ PhP.

Table 1.

Hypotheses and their independent and dependent variables

| Hypotheses | Independent variable | Dependent variable |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | AT applications | VP |

| H2 | AT applications | PhP |

| H3 | AT applications | FA |

| H4 | VP | PhP |

| H5 | FA | VP |

| H6 | FA | PhP |

Methodology

The current study performed an experimental treatment for specific educational tasks and tested the effects of employing this treatment. To learn more about the studied phenomenon from the perspective of the participants, a quantitative approach was followed (Leedy & Ormrod, 2005). Accordingly, the current study adopted a quasi-experimental design, as it aimed to examine and test the causal relationships between variables. The quasi-experimental design is the most suitable for this purpose, as it relies on field experimentation and not laboratory experimentation (Neuman, 2014). The participants in the current study were students in the third grade who were diagnosed with dyslexia and were living et al.-Ahsa Governorate. The students had different nationalities: eight Saudis, six Egyptians, three Sudanese, and three Jordanian, though all of them were from Arab countries, and their mother tongue was Arabic. Accordingly, a quasi-experimental design was used to clarify the relationship between AT applications and their influence on VP, PhP, and FA in both boys and girls during the pandemic. Moreover, the current study adopted a single-subject experimental method, which is used to clarify the effects of an independent variable intervention on a dependent variable (Neuman & McCormick, 1995). The results of studies based on single-subject experiment methods are attributed to the nature of the effects that the variable (AT) had on the dependent variables (VP, PhP, and FA) and not to any other factors. Also, the recommendations related to the results are developed through an adequate explanation of the systematic procedures that were applied to the study sample members (Horner et al., 2005). Furthermore, single-subject experiment methods are particularly useful for studying therapeutic program problems and providing a solution when it is unrealistic to administer systematic procedures with large samples (Barlow & Hayes, 1979). This situation fully applies to the current study, which seeks to address the problem of developmental dyslexia with a small sample size available. Single-subject empirical investigations can also serve as a follow-up to case study research, where case study data are documented and followed up individually to explore attempts to make changes in the future. The collected data will assist in the planning and design of curricula in many special education programs (Neuman & McCormick, 1995).

Sample

The Department of Special Education et al.-Ahsa Governorate, Al-Reeyada International School, was chosen as the site for this study. A total of 150 students were enrolled in the third grade at the time of the study. In the second term, and to select a purposeful sampling, in which based on their characteristics (Cohen et al., 2002) as dyslexic and to match the aim of the current study, Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM) were carried out to measure the holistic intelligence of students. A diagnoses-achievement test was also conducted to measure students’ reading disabilities. These tests were guided by the psychologist at the school and under the supervision of the Ministry of Education in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Based on these tests, 25 students were diagnosed with dyslexia. In the next phase, for ease of control, a random choice was made to identify 20 participants. Their RPM scores ranged from 17 to 27 (M = 22.00, SD = 4.74), and their diagnosis achievement test scores ranged from 5 to 7 (M = 5.90; SD = 0.85). Participants were aged between eight and nine years (M = 2.00; SD = 0.85), as shown in Fig. 1. In the next phase, all participants were distributed based on their gender (10 girls/ 10 boys); then, six students (three girls/ three boys) were randomly chosen for the pilot study, and the remaining students were divided into a first experimental group comprising seven girls and a second experimental group comprising seven boys. The students’ parents gave their verbal consent for their children’s participation in the study. They were free to leave the study whenever they wanted.

Fig. 1.

The mean distribution for the research sample

Instrument

Below, the current study discusses the procedures used to develop the constructs for both the graphical VP and PhP scales and the phrases used to measure the visual and phonological recognition among the dyslexic students.

Graphical VP scale

Drawing from previous research, a graphical VP scale was developed to assess students’ VP based on an evaluation of their visual recognition abilities in the Arabic language. The scale comprised 17 phrases distributed across 6 axes: visual discrimination (phrases 1, 2, 3, and 4), spatial relationships (phrases 9, 12, 14, and 17), visual memory (phrases 6 and 13), figure-ground (phrases 11 and 15), visual closure (phrases 5, 10, and 8), and visual attention (phrases 7 and 16). To evaluate each student accurately, the phrases of the axes on the VP scale were transformed into a set of questions. Each question was linked to a specific picture, and both the phrase and the question were expressed simultaneously. These questions were taken from the Arabic language course that was taught in third grade while considering the common manifestations of dyslexia in terms of diacritical marks, orthographs, and similar shapes, as shown in Fig. 2. During the process of the experiment, each student was asked to answer each question one by one, and the student’s response was noted under the corresponding phrase on the scale. Therefore, the authors named the scale the graphical VP scale. Each phrase contributed one point to the final score. A four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (always) to 4 (rarely) was adopted to estimate the students’ scores on the VP scale. Possible scores for the scale ranged from 17 (lowest) to 68 (highest). A special education expert examined the scale, and a few amendments were made to the scale based on his input before being used for the study. As the students answered the questions, the authors monitored and evaluated their performance, rating the consistency of their performance from 1 (always) to 4 (rarely).

Fig. 2.

The procedural format for the graphical VP scale for dyslexic students

Graphical phonological processing scale

A graphical PhP scale was developed to assess students’ PhP by measuring their phonological recognition abilities in Arabic. The scale comprised 19 phrases, distributed on four axes: word awareness (phrases 1, 10, and 18), syllable awareness (phrases 2, 7, 13, and 14), rhythm awareness (phrases 4, 15, 16, and 19), and phonemic awareness (phrases 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, and 17). Each phrase was worth one point. A four-point Likert scale was adopted, ranging from 1 (rarely) to 4 (always), to estimate the students’ scores on the PhP scale. Possible scores ranged from 19 (lowest) to 76 (highest). As shown in Fig. 3, the phrases on all axes were transferred to graphical questions. A special education expert also examined this scale, and a few amendments were made to the scale based on his inputs before it was finalized. The students were asked to answer these questions while the authors monitored and evaluated their performance, rating the consistency of their performance from 1 (rarely) to 4 (always).

Fig. 3.

The procedural format for the graphical PhP scale for dyslexic students

Expert review

To calculate the interrater and content validity, three experts were chosen based on their vast experience in the field of teaching methods and curriculums in Arabic, instructional technology, special education, and dyslexia. The cognitive objectives, the content for teaching Arabic, and the prepared activities were presented to the first expert of teaching methods and curriculums in Arabic to obtain his opinions on the suitability of the content for the students, the attainment of the cognitive objectives, and the level of importance and precision of the content. The proposed AT applications (Google Classroom, Zoom, and Quizlet) were presented to the second expert in instructional technology for his opinions on the suitability of the applications and the content provided. Both experts agreed on the relevance of the content to the students and to the cognitive objectives. The experts also noted that the AT applications were convenient to use and offered a few amendments, such as paraphrasing some of the content so that it was in line with the objectives and levels (Bloom grades). Both scales were presented to a third expert in special education and dyslexia for his opinion. The third expert indicated that the two scales were highly suitable and relevant to the objectives and levels, and that the phrases were precise, scientifically accurate, and relevant to the axes and to the procedure that the student would undergo. He offered a few recommendations to make some adjustments by rewriting and merging a few phrases because they had the same meaning. Additional adjustments were made to phrases, considering how dyslexia affected the perception of terms of diacritical marks, orthographs, and similar shapes.

Pilot study

After making the suggested amendments, both scales were ready to use. To calculate the statistical validity and reliability of the scales, six students (three girls and three boys) were randomly chosen for the pilot, and both scales were applied to them. Internal consistency validity was calculated by evaluating the correlation between the scores for each student on the entire scale and on every axis. The correlation values for the graphical VP and PhP scales ranged from 0.90 to 0.92, and from 0.89 to 0.91, respectively. Both scales were deemed suitable. After two weeks, the two scales were applied again to the same sample to calculate reliability. The correlation between both processes was 0.84 and 0.82 for the graphical VP and PhP scales, respectively, representing high reliability. The current study relied on measuring the correlation coefficients between the first and second applications to calculate the value of the reliability coefficient. To obtain honest and realistic values for the study tool with a small sample size, it is recommended to use the retest method to calculate the reliability coefficient by measuring the correlation coefficients between the first and second applications of the study tool instead of applying Cronbach’s alpha (Guadagnoli & Velicer, 1988; Samuels, 2017; Yurdugül, 2008). The time for both scales was calculated by dividing the total time the students spent on each measure by the number of students. The timings for the graphical VP and PhP scales were 40 and 42 min, respectively.

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee at King Faisal University, under application No. KFU-REC/2020–09-04, to conduct this study at the Al-Reeyadah International School in the Al-Hasa Governorate. The authors asked the school administration to provide a list of students, along with their ages and ratings of using AT applications in blended learning before the pandemic. This list was designed to assist the authors with the discussion results. This list also assisted us in understanding whether these applications had a positive impact on the current sample. The school provided the authors with the duties and activities assigned to the students prior to the pandemic and arranged these activities according to the intensity of use and by students, from lowest to highest. The authors also coordinated with the schoolteacher responsible for Arabic to set up the experiment and the AT applications. Google Classroom was used to upload prerecorded lessons, Zoom was used for live sessions, and Quizlet was used to present learning activities, homework, and assignments.

Pre-recorded Arabic lessons were uploaded by the class teacher every Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday onto Google Classroom according to the syllabus. After watching the lessons, every student was asked to leave a comment with their doubts on any part of the lesson. The next step was to set up a live session, which was hosted every Wednesday on Zoom. The class teacher met with the students face-to-face and presented the same lesson, while a short paragraph in the Arabic language was shown to develop the VP through the axis of the graphical VP scale. The lessons considered one or more dyslexia issues, such as diacritical marks, orthographs, and shapes of the letters. PhP was also presented considering the axis of the graphical PhP scale, which was involved in the lesson paragraphs and activities, again considering one of the dyslexia issues. The teacher helped the students spell and read one of the paragraphs from the lesson to correct their faults and gave them immediate feedback.

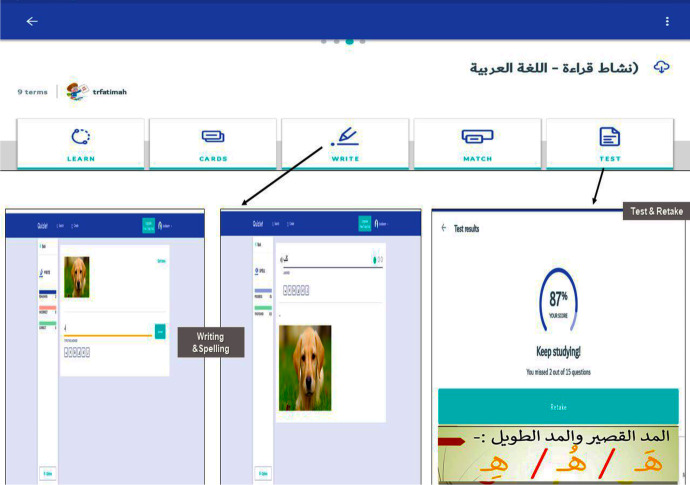

Every Thursday, an insight into the previous step and a summary of the activities were uploaded using the tool of (learn, matching, and flashcards), which were built in the Quizlet application, and the visual and phonological exercises, including the diacritical marks, orthographs, and the shapes of the letters, about the located lesson were presented. The students’ queries were considered in the first step, for example, the short and long vowels for specific letters and their locations in the word (first, middle, or end) in the Arabic language, and the right vocalization and visualization orthographs for the word were presented, as shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

Fig. 4.

Using learn tool, cards tool and match tool in the Quizlet application

Fig. 5.

Using write and test tool in the Quizlet application

In this phase, every student had to do their homework and other assignments on Quizlet. This helped identify the VP and PhP in the lesson-on-hand with the test and write tools. Appropriate feedback (instant/final) was given to each student via the application. If a student was proficient, enrichment was provided. If a student failed, an opportunity for further training was provided. This was done for eight consecutive weeks.

In the 14th week, the authors set up live sessions via Zoom with the help of the class teacher to meet the students individually according to an allocated timetable to apply the procedural format for both scales (graphical VP and PhP scales). The format consisted of 36 procedural questions and covered all phrases in both scales. Moreover, the class teacher presented the procedural format to each student separately. The authors had different roles: one helped the class teacher present the specific procedural format to the students, another monitored the students’ performance on the graphical VP scale, and the third monitored the students’ performance on the graphical PHP scale, as previously explained in the Instruments section.

The login for each student in every AT application (Google Classroom, Zoom, Quizlet) was gathered during the study period to calculate the FA. In terms of login information, this included the number of times the studied applications were accessed. A four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (rarely) to 4 (always) was adopted to estimate the students’ scores for FA. The FA scores ranged from 1 (lowest) to 4 (highest). If the student’s FA was restricted to logging in to see the pre-recorded lessons via Google Classroom, they were evaluated as rarely and scored 1 point. If their FA was restricted to logging in solely to the two pre-recorded lessons via the Google Classroom application and the live session via the Zoom application, they were evaluated as occasionally and scored 2 points. If their FA was involved logging in to both pre-recorded lessons via the Google Classroom application, to the live session via the Zoom application, and the activities via Quizlet application, they were evaluated as mostly) and assigned 3 points. If their FA was inclusive for all days of the week over the whole application, they were evaluated always and scored 4 points (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

FA for both experimental groups in AT applications

The experiment took place over 14 weeks in the second term of the school year. Classes were suspended because of the pandemic from January 26 to June 22, 2021.

Results

IBM’s SPSS v. 26 software was used. An independent samples t-test was conducted to examine the differences between the mean scores of the two experimental groups (girls vs. boys) in VP, PhP, and FA. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were also identified between VP and PhP. Analytical simple linear regression was used to identify the independent variables that served as predictors (FA) of the dependent variables (VP and PhP).

Homogeneity between the two groups

Table 2 presents the homogeneity between the first and second experimental groups before proceeding with the experiment. The results of the independent samples t-tests of the graphical VP scale scores of both groups show that no significant differences existed between the first (girls) (M = 37.85, SD = 2.67) and the second (boys) (M = 36.42, SD = 2.43) experimental groups in the VP pre-test (t (12) = 1.04, p > 0.05 = 0.351). Both groups were homogeneous before the experiment was conducted.

Table 2.

Independent samples t-test for the research groups on the VP (pre-test)

| GROUP SIZE | N | MEAN | SD | DF | T | SIG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (1) | 7 | 37.85 | 2.67 | 12 | 1.04 | 0.351 |

| Boys (2) | 7 | 36.42 | 2.43 |

Research question results

This section discusses the results of the research questions.

RQ1-A

What influence did the AT applications have on the VP of dyslexic students in Saudi Arabia during the pandemic?

Table 3 presents the means and standard deviations for the first and second experimental groups and the results of the t-test of the two groups’ scores on the graphical VP scale post-test. The findings showed that significant differences existed between the first experimental group (girls) (M = 66.71; SD = 1.60) and the second experimental group (boys) (M = 62.28; SD = 3.90) in the VP post-test (t(12) = 2.77; p < 0.05 = 0.016) in favor of the first experimental group (girls). Accordingly, the first hypothesis was rejected.

Table 3.

Independent samples t-test for both research groups on the VP (post-test)

| GROUP SIZE | N | MEAN | SD | DF | T | SIG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (1) | 7 | 66.71 | 1.60 | 12 | 2.77 | 0.016 |

| Boys (2) | 7 | 62.28 | 3.90 |

RQ1-B

What influence did AT applications have on the PhP of dyslexic students in Saudi Arabia during the pandemic?

Table 4 shows the means and standard deviations for the first and second experimental groups and the independent sample t-tests of both groups’ scores in the graphical PhP scale post-test. The results showed that significant differences existed between the first (girls) (M = 74.71; SD = 1.60) and second (boys) (M = 66.00; SD = 6.83) experimental groups in the post-test (t(12) = -3.28; p < 0.05 = 0.002) in favor of the former. Thus, the second hypothesis was rejected.

Table 4.

Independent samples t-test for the research groups on the PhP (post-test)

| GROUP SIZE | N | MEAN | SD | DF | T | SIG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (1) | 7 | 74.71 | 1.60 | 12 | 3.28 | 0.002 |

| Boys (2) | 7 | 66.00 | 6.83 |

RQ1-C

What influence did AT applications have on the FA of dyslexic students to AT in Saudi Arabia during the pandemic?

Table 5 presents the means and standard deviations for both experimental groups and the independent samples t-tests of both groups’ scores in the FA post-test. The results showed that there were significant differences between the first (girls) (M = 3.42; SD = 0.53) and second (boys) (M = 2.57; SD = 1.27) experimental groups in the post-test (t(12) = -1.643; p < 0.05 = 0.019) in favor of the former. Accordingly, the third hypothesis was rejected.

Table 5.

Independent samples t-test for the research groups on the FA (post-test)

| GROUP SIZE | N | MEAN | SD | DF | T | SIG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (1) | 7 | 3.42 | 0.53 | 12 | 1.643 | 0.019 |

| Boys (2) | 7 | 2.57 | 1.27 |

RQ2

Does a correlation exist between dyslexic students’ VP and PhP after using the AT application?

Table 6 presents the Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the VP and PhP (r = 0.989**, p < 0.05), which shows that it is significant at the level (p < 0.05). Accordingly, and considering the correlation as significant (Lehman et al., 2005), we conclude that a positive correlation exists between the VP and PhP for dyslexic students after using AT applications. Accordingly, the fourth hypothesis was rejected.

Table 6.

Results of the correlation analysis

| VARIABLE | VP PhP |

|---|---|

| R | 0.989** |

| SIG | 0.000 |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1−tailed). p < .05

RQ3

Does the students’ FA to AT applications affect their VP?

A simple linear regression analysis was used to identify the relationship between FA for dyslexic students, which is considered an independent predictor variable, and VP, which is a dependent variable.

RQ4

Does the students’ FA to AT applications affect their PhP?

To understand the relationship between FA for dyslexic students, which is considered an independent predictor variable, and the PhP, which is a dependent variable, a simple linear regression analysis was used.

Discussion

This section discusses the results of the study and the hypotheses.

H1

No statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between the first (girls) and second experimental groups (boys) in terms of their VP after using the AT application.

Table 3 and Fig. 7 show the post-test results for VP, which indicate that a significant difference was found between the two groups after using the AT application. In previous research (Benmarrakchi et al., 2017; Buele et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2021; Malcolm & Roll, 2017), it was observed that students in both groups were satisfied with the AT applications and had better outcomes when compared to the pre-test results. The current results supported the use of AT applications, as both groups showed improved scores. There was a greater degree of improvement in VP using AT applications among girls than among boys, which may be because girls were more familiar with AT applications than boys before this study. The school had previously assigned tasks for the students using some form of instructional application; however, boys with dyslexia achieved lower scores and were more disruptive compared to girls, which affected their learning outcomes. This view is supported by other studies, which found that boys were most likely to be referred for treatment, as they are more disruptive than girls (Malcolm & Roll, 2017). Other studies (Berget & Sandnes, 2015; Cai et al., 2020) have shown that more boys have more significant VP problems compared to girls in terms of their ability to recognize diacritical marks and orthography. This could be because there is less recognition of VP issues among girls compared to boys. Fewer diagnoses will lead to less identification of the issue among the girls. By contrast, Draffan et al. (2007) found that no differences existed between boys and girls regarding the use of AT, and that its impacts and outcomes were homogenous. It may be that AT cannot be employed for people with different disabilities. Another study found that AT was ineffective among students with movement-related disabilities or disabilities that caused pain (Malcolm & Roll, 2017). AT was also not as effective for people with neurological damage. Therefore, the differences in the VP scores between boys and girls could be due to the differences in their disabilities.

Fig. 7.

Independent samples t-test for both research groups on the VP (post-test)

Suroya and Al-Samarraie (2016), Cheng et al. (2021), and Friantary et al. (2020) supported the use of AT to improve visual prediction among students with dyslexia. The results of these studies show that girls with dyslexia can predict the next target and are more motivated to view the content. However, boys exhibit a longer gaze and focus on the current target. However, Caccia et al. (2019) found a contradictory result, wherein boys scored higher than girls. They noted that this was because boys were better at spatial–visual tasks than at comprehension (Caccia et al., 2019). This result is consistent with those of Benmarrakchi et al. (2017), who addressed the role of information and communication technology (ICT) in supporting dyslexic students. They indicated that most students who suffer from dyslexia tend to be visual learners (Benmarrakchi et al., 2017). AT supports these students by making use of a wide variety of information and audio-visual learning materials. AT can also be used as a tool for adaptive learning and as a scaffolding tool (Schmitt et al., 2019). Additionally, AT could be used to reduce the common difficulties of students with dyslexia, such as the vocalization of diacritics in pronunciation as well as in writing, and the similarity among some letters in both orthograph and shape. Several researchers (De Avelar et al., 2015; McNicholl et al., 2020; Muftah & Altaboli, 2020) have also emphasized the current result, which showed that combining the visual information in the graphical user interface design in the AT applications increases students’ educational skills and their VP abilities.

H2

No statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between the first (girls) and the second experimental groups (boys) in terms of their PhP after using the AT application.

As can be seen in Table 4 and Fig. 8, the results showed statistical differences between the two groups in the PhP in the post-test, indicating that girls scored higher in PhP compared to boys. Our results contradicted those of Caccia et al. (2019) and Rasmusson and Åberg-Bengtsson (2015), who showed that boys scored better in reading the graphs compared to girls. This difference in results may be because there was a greater use of digital media among the girls in the present study compared to those examined in the abovementioned studies. The study which showed a better performance in phonological ability compared to the girls was likely due to less interest in the use of digital media and technology among the female students (Žarić et al., 2018). Girls in this study may have had greater access to technology, which may have improved their outcomes vis-à-vis enhanced reading abilities. Boys may have done poorly in reading and comprehension because they focused more on online games and entertainment than on the syllabus. The differences in gender PhP could also be the result of differences in technology use among people from different countries (El-Sady et al., 2020). Krafnick and Evans (2019) also claimed that the different characteristics exhibited by boys and girls may have been a factor affecting girls’ superiority. For instance, boys showed a slower processing speed and less inhibitory control, demonstrating the reason for the lower scores of boys in the present study. Furthermore, the higher scores of girls in the present study could be due to the higher strength of language skills among girls with dyslexia. Su et al. (2018) stated that changes in brain volume can affect performance. Thus, it is possible that girls exhibited a higher ratio of gray matter to white matter. Additionally, the differences in the outcomes could also be due to age variations and sample size. For example, Altarelli et al. (2014) showed that differences in PhP could be due to changes in brain anatomy or genetic factors.

Fig. 8.

Independent samples t-test for both research groups on the PhP (post-test)

Furthermore, the current result can be explained in light of Benmarrakchi et al.’s (2017) study, which showed that 60% of students with dyslexia prefer the auditory learning style when using ICT applications. This finding explains the current results of the students’ superiority in PhP ability.

H3

No statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between the first (girls) and second experimental groups (boys) in terms of their FA after using the AT application.

Table 5 and Fig. 9 show the statistical differences among girls and boys in the FA in the post-test, indicating that the influence of using AT applications led to an increased login frequency among the students over the 14 weeks. This result shows the potential characteristics of AT applications. For example, interactive learning, which involved the students in cooperation and collaboration interactions among them or with their teacher (Rasmusson & Åberg-Bengtsson, 2015), led to more engagement in the AT applications and thus an increase in their FA. Moreover, the learning activities and games, which were characterized by a familiar graphical user interface that resulted in a competitive environment, led to increased social engagement and thus enhanced FA among students. Gallego-Durán et al. (2019) and Cagiltay et al. (2015) emphasized that competition and challenges between players led to greater access to digital platforms. Moreover, the Anoual and Abdelhak (2014) revealed that the AT system that was developed for dyslexics was influential because it used simple graphic pages with applicable background colors, which increased the students’ attention and usage. Accordingly, the current AT applications, which had a friendly graphical user interface, increased the students’ FA.

Fig. 9.

Independent samples t-test for both research groups on the FA (post-test)

The results also showed that the girls’ group scored higher in FA than the boys’ group. This finding can be explained by what was mentioned before in terms of the differences between girls and boys in the ratings of using AT applications in blended learning before the pandemic, where girls scored higher. Furthermore, individual linguistic skills and differences in nationalities among the students, as well as environmental and cultural differences, were potential factors in the current result.

To increase access to AT applications among students with dyslexia, Habib et al. (2012) suggested unifying the application in terms of the educational level and educational institution to which they belonged, and to not move from one application to another, as this requires more effort not only to deal with the new system but also to master its terminology, which would increase cognitive load in addition to the symptoms of dyslexia from which they suffer, which reduces the FA rate. This result is consistent with the procedures of the current study in terms of standardizing the AT applications for students with dyslexia: Google Classroom was used for uploading prerecorded classes, Zoom was used for live sessions, and Quizlet was used to present learning activities, homework, and assignments. This led to an increase in the students’ FA of these applications, and then its reflection on the development of both VP and PhP. Moreover, Barden (2014) emphasized that it is necessary to consider the amount of educational content, educational design, and the graphical design of AT applications. These important factors lead to one of two outcomes: an increase in FA, or complete invisibility from their use. These factors were already available in the AT applications adopted by the current study, which led to an increase in the motivation of students with dyslexia to increase their FA. Furthermore, many factors play a crucial role in increasing FA in AT applications. Venturini and Gena (2017) conducted experiments to improve the FA of the web for dyslexics and found several factors that should be combined in AT systems: complete, exhaustive, and intuitive glossaries; increasing the minimum font and line spacing size; decreasing the number of characters for each text column; and giving precise guidelines for designing a clear layout. Rello et al. (2012) also explored a set of recommendations to improve FA for dyslexics in AT systems, emphasizing that larger character spacing can significantly improve the readability for dyslexic and non-dyslexic peers. As such factors were available in the AT applications used in the current study, the students scored higher in the FA after using them.

H4

No statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between the correlation coefficients for both experimental groups’ VP and PhP after using the AT application.

According to several studies (Chen et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2018; Hebert et al., 2018; Corvace et al., 2020; Van der Kleij et al., 2019; Ali et al., 2021), VP is key to PhP. Therefore, VP is essential in supporting the mapping of phonological units, resulting in improved reading and PhP. Figure 10 shows that while the VP shares 97.9% of the PhP accomplishment in AT applications (R2 = 0.979), it does not necessarily cause it. Different approaches may offer more potential factors, such as social interaction and technology acceptance parameters (Tariq & Latif, 2016), which refers to when content is presented via pictures and videos to clarify, for example, the written letter shape at different places in the word, the vowels letters and its orthograph, and the diacritical marks and morphology for letters in the Arabic language. Accordingly, these factors enhanced the VP ability of students and affected their learning outcomes (Corvace et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2021). Consequently, the PhP was also enhanced.

Fig. 10.

Linear scatter plot between VP& PhP

Law et al. (2018) emphasized that morphological awareness is a significant influencer in high-functioning adults with dyslexia. Many studies have explored the relationship between VP and PhP. For example, Wang and Yang (2018) found a good relationship between them, claiming that the literacy should be presented according to specific criteria relating to the amount of words and shapes in a good visual format to guarantee that the PhP will happen in the right way among Chinese bilingual students. Bellocchi et al. (2017) emphasized that phonological awareness and visual–motor integration predict reading outcomes among children with developmental disabilities.

H5

The students’ FA to AT applications was not found to affect their VP.

According to Table 7 and Fig. 11 (r = 0.807; r2 = 651; p < 0.05 = 0.000), a positive correlation exists between FA and VP for dyslexic students after using the AT applications, which demonstrates that only FA can explain approximately 65% of the VP occurrence. As Fig. 11 shows, the simple regression model was significant (f = 22.404; p < 0.05 = 0.000), and the value of the unstandardized coefficient had a statically significant positive relationship to clarify how the FA can predict and explain the VP (B = 2.857; β = 0.807; t = 4.733; p < 0.05 = 0.000). Accordingly, the more FA dyslexic students have in AT applications, the more their VP ability improves (by 2.857); the current model predicts that an increase in FA by one unit will develop 2.857 more VP for dyslexic students. Accordingly, the fifth hypothesis was rejected. However, this means that the remaining 35% of the variation in VP cannot be explained by FA. Therefore, there must also be other influential variables (Field, 2013) that revolve around the variety of writing activities, hypertext, and interactive hypermedia that were involved in the AT applications. In the current study, these variables were used to clarify the morphology, orthography, and pronunciation of letters according to the diacritical marks, and they reveal students’ doubts about similar letters and vowels and how to write them neatly. Consequently, an increase in VP ability occurs for dyslexic students. Moreover, it was emphasized that online distance learning helped students build students’ visual cognitive skills (Al Mulhim & Eldokhny, 2020; Capacio et al., 2021; Eldokhny & Drwish, 2021; Ge et al., 2018). Consequently, the current AT applications also met the needs of the dyslexic students in terms of building their mental models, which further influenced their VP. Additionally, as cited in Alsobhi et al. (2014), Staels and Van den Broeck (2015) state that dyslexic students have various symptoms and that AT applications must deal with each student as a special case. Accordingly, the current AT applications were supported with multimodal systems, which served as a crucial factor in enhancing the students’ VP according to reinforcing the principle of individual differences among students.

Table 7.

Results of the simple regression analysis between FA and VP

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE | VP |

|---|---|

| PREDICTOR VARIABLE | FA |

| R | 0.807 |

| R2 | 0.651 |

| F | 22.404 |

| SIG | 0.000 |

| B | 55.929 |

| 2.857 | |

| β | 0.807 |

| T | 29.300 |

| 4.733 | |

| SIG | 0.000 |

| 0.000 |

Fig. 11.

Scatterplot showing the relationship between VP development and the number of FA

However, many studies related to the field of ICT (Al-Dokhny et al., 2021; Al-Rahmi et al., 2019; Alyoussef, 2021; Tarasov et al., 2020) were conducted in light of the technology acceptance model (TAM) developed by Davis (1989), which confirmed that providing an effective e-learning environment for students helps increase their behavioral intention to use it in the future. The environment must provide perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness, where the perceived ease of use makes easy access to the resources of these systems through the hand-easy tools, which in turn affect their perceived usefulness. From this viewpoint, we can understand how the students in the current study experienced ease in using the tools and resources of the AT applications, which was reflected in their interest in both VP and PhP via increasing the FA to the AT applications.

H6

The students’ FA to AT applications was not found to affect their PhP.

Table 8 and Fig. 12 (r = 0.790; r2 = 624; p < 0.05 = 0.000) show a positive correlation between the FA and the PhP for dyslexic students with AT applications. Accordingly, the sixth hypothesis was rejected. Figure 12 shows that the simple regression model was significant (f = 19.885; p < 0.05 = 0.001) and the value of the unstandardized coefficient has a statically significant positive relationship to clarify that the FA can predict and explain the PhP (B = 5,000; β = 0.790; t = 4.459; p < 0.05 = 0.001). Accordingly, the greater the FA among dyslexic students to AT applications, the more their PhP ability increases. For example, if FA is increased by one unit, then the current model predicts that dyslexic students will develop 5,000 extra PhP. However, FA can only explain approximately 62% of PhP. Therefore, other variables must also have an influence. These variables may relate to the variety of listening activities and interactive narration videos that are included in the current AT applications, as well as the vocalization activities that support the pronunciation of diacritical marks and vowel letters and have been used to clarify the morphology and pronunciation of letters in the Arabic language. Furthermore, Rello et al. (2012) found that AT applications become more influential in PhP, as they allow dyslexic students to choose font size, colors, and spacing for letters, thus enhancing their VP ability. Hence, we can also expect increases in PhP, which supports the current results.

Table 8.

Results of the simple regression analysis between FA and PhP

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE | PhP |

|---|---|

| PREDICTOR VARIABLE | FA |

| R | 0.790 |

| R2 | 0.624 |

| F | 19.885 |

| SIG | 0.001 |

| B | 55.357 |

| 5.000 | |

| Β | 0.790 |

| T | 15.612 |

| 4.459 | |

| SIG | 0.000 |

| 0.001 |

Fig. 12.

Scatterplot showing the relationship between PhP development and the number of FA

Limitations and future research

The current study has some limitations in that the data were collected only from students who were enrolled in grade three at one school in the Al-Ahsa governorate of the KSA. Thus, this must be considered when generalizing the findings. Furthermore, as we did not perform an analysis of the quantitative or qualitative data to address the impact of the learning style and its relationship with the gender of students with dyslexia when using AT applications, more futuristic studies are highly recommended. Also, the current study is based on the AT type, which addressed literacy teaching applications, but it did not address the type based on offering access to the learning and production of learning materials in an integrated format combined with software and hardware.

Moreover, there is an urgent need to conduct more research into factors related to the structure of AT systems and programs, such as font size; criteria for including images, videos, and audio; and the text density of the content, which would provide an enjoyable, flexible, and stimulating learning environment for dyslexics. Accordingly, reducing students’ learning efforts would help them develop both self-regulation skills and self-efficacy when dealing with such systems individually or through the supervision of both teachers and parents. More studies should also be conducted to develop mechanisms for early intervention and diagnosis of children with dyslexia in early childhood to overcome the dyslexia paradox and mitigate its negative effects in the future. Furthermore, solutions should be sought by employing effective AT systems at the level of software and hardware.

Educational institutions also face great challenges for their students. It is no longer sufficient to provide appropriate AT in learning settings for dyslexic students, based on the nature of the courses and the skills they require. Rather, it has become a requirement to ensure perceived ease of use and the usefulness of the AT system that has been used. Therefore, more futuristic studies are highly recommended.

Conclusions

This study was conducted to measure the influence of AT on dyslexic students. Pre- and post-tests were conducted to check the VP, PhP, and FA of third-grade students during the partial lockdown in the first academic term of 2020 because of COVID-19. Google Classroom, Zoom, and Quizlet were the AT applications used to enhance the students’ VP and PhP. The findings showed that no significant differences existed between the two experimental groups, which were divided by gender in terms of VP, PhP, and FA. However, girls scored higher than boys in VP, PhP, and FA. This outcome may have been because boys were more disruptive than girls; we also saw that they used AT applications less than girls prior to the pandemic. Furthermore, girls were more interested in online learning and in using digital media, while boys were more interested in playing online games. There was a statistically significant difference in the correlation coefficient between VP and PhP among girls and boys. The results also showed that FA can predict the development of VP and PhP for dyslexics; a higher FA increases VP and PhP, and these increases reduce the severity of dyslexia. Overall, more research should be conducted in clinical settings where students can review special training regarding improvements in language and reading abilities, as well as other areas. This can improve their cognitive abilities, and appropriate measures can be implemented to improve their performance and skills.

The research findings suggest that more research is needed to explore teachers’ need to use AT in the classroom and their need for specific built-in tools, which could be applicable to the learning styles of students with large sample sizes. Furthermore, research should explore the role of AT in providing solutions to other issues of dyslexia in the Arabic language. For example, homograph language, definite articles, and the glottal stop (Hamza) were crucial factors in dyslexia. AT applications can contribute to reducing these factors in the Arabic language in an influential way by using multimedia elements.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amany Ahmed Al-Dokhny, Email: amany.eldokhny@sedu.asu.edu.eg, Email: aeldokny@kfu.edu.sa.

Amani Mohammed Bukhamseen, Email: abukhamseen@kfu.edu.sa.

Amr Mohammed Drwish, Email: AMR_DARWISH@edu.helwan.edu.eg.

References

- Abu-Keshk ATH, Kürüm Y. The effect of sustained silent reading on dyslexic students’ reading comprehension in ELT. International Journal of Social Research. 2021;8:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Rabia S, Abu-Rahmoun N. The role of phonology and morphology in the development of basic reading skills of dyslexic and normal native Arabic readers. Creative Education. 2012;3(07):1259. doi: 10.4236/ce.2012.37185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afonso O, Suárez-Coalla P, Cuetos F. Writing impairments in Spanish children with developmental dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2020;53(2):109–119. doi: 10.1177/0022219419876255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mulhim E, Eldokhny A. The impact of collaborative group size on students’ achievement and product quality in project-based learning environments. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning. 2020;15(10):157–174. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v15i10.12913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Otaiba S, Petscher Y. Identifying and serving students with learning disabilities, including dyslexia, in the context of multitiered supports and response to intervention. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2020;53(5):327–331. doi: 10.1177/0022219420943691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Rowais, F., Wald, M., & Wills, G. (2013). An Arabic framework for dyslexia training tools. 1st International Conference on Technology for Helping People with Special Needs (ICTHP-2013), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 19 - 20 Feb 2013. pp. 63–68.

- Aldabaybah, B., & Jusoh, S. (2018). Usability features for Arabic assistive technology for dyslexia. In 2018 9th IEEE Control and System Graduate Research Colloquium (ICSGRC) (pp. 223–228). IEEE. 10.1109/ICSGRC.2018.8657536

- Al-Dokhny A, Drwish A, Alyoussef I, Al-Abdullatif A. Students’ intentions to use distance education platforms: An investigation into expanding the technology acceptance model through social cognitive theory. Electronics. 2021;10(23):2992. doi: 10.3390/electronics10232992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alghabban WG, Salama RM, Altalhi AH. Mobile cloud computing: An effective multimodal interface tool for students with dyslexia. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;75:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S. A., Fadzil, N. A., Reza, F., Mustafar, F., & Begum, T. (2021). A mini review: Visual and auditory perception in dyslexia. IIUM Medical Journal Malaysia, 20(4). 10.31436/imjm.v20i4.1616.