Abstract

Huge vaccination drives are underway around the world for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. However, the search for antiviral drugs is equally crucial. As new drug discovery is a time-consuming process, repurposing of existing drugs or developing drug candidates against SARS-CoV-2 will make the process faster. Considering this, 63 approved and developing antimalarial compounds were selected to screen against main protease (Mpro) and papain-like protease (PLpro) of SARS-CoV-2 using in silico methods to find out possible new drug candidate(s). Out of 63 compounds, epoxomicin showed the best binding affinity against the Mpro with CDocker energy of − 57.511 kcal/mol without any toxic effect. This compound was further taken for molecular dynamic simulation study, where the Mpro-epoxomicin complex was found to be stable with binding free energy − 79.315 kcal/mol. The possible inhibitory potential of the selected compound was determined by 3D-QSAR analysis and found to be 0.4447 µM against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Finally, the structure activity relationship of the compound was analyzed and two fragments responsible for overall good binding affinity of the compound at the active site of Mpro were identified. This study suggests a safe antimalarial drug, namely epoxomicin, as a probable inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro which needs further validation by in vitro/in vivo studies before clinical use.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11224-022-01916-0.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Antimalarial agent, Molecular dynamics, Drug repurposing, Antiviral agent, Epoxomicin

Introduction

Beginning from the seafood market of Wuhan, China, on December 2019, the pneumonia-like disease COVID-19 has spread over 180 countries around the world affecting around 167,423,479 individuals and accounting for 3,480,480 deaths until 26 May 2021 [1, 2]. This deadly disease is caused by a single-stranded RNA virus termed as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), belonging to the coronavirus family, and is the third pathogenic betacoronavirus that has crossed the species barrier from the animal host to infect humans other than severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [3–5]. Due to the exponential transmission rate of the infected cases, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on 11 March 2020 [6]. Unfortunately, no specific effective drugs have yet been developed or available in the market for the treatment of COVID-19. Although some of the vaccines have reached the clinical trial phase II/III, still they have some serious drawbacks and are not yet ready for common people [7].

After the discovery of the full genome sequence, several crucial proteins like the main protease (Mpro) and papain-like protease (PLpro) of the virus were identified as possible targets for the drug development process [8, 9]. Both these two proteins have a vital role in the replication of the virus. After releasing the viral genome into the host cytoplasm, the replicase gene is translated to express polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab which contain nsp1-11 and nsp1-16 respectively. These polyproteins are cleaved by viral proteases like Mpro and PLpro [10]. Due to its importance in viral replication, conserved sequences, and 3D structures, Mpro has become a potential target for drug discovery against the novel coronavirus [11]. In addition to the role in viral replication, PLpro also suppresses innate immunity through reversing the ubiquitination and ISGylation events where SARS-CoV-2 PLpro prefers the ISGylated proteins [12]. This dual functionality of PLpro makes it an attractive target for drug discovery against SARS-CoV-2. In the past few months, several studies have reported many potent inhibitors of the Mpro and PLpro but some of them are yet to be verified [13, 14].

As the discovery of new drug is time-consuming and costly process, repurposing of the existing approved drugs could substentially fasten the process of drug development. Many reseaserchers are trying to repurpose the already available drug from different categories against the SARS-CoV-2 [15, 16]. These kinds of studies have already been initiated and, up to some extent, success has been achieved. So in our study, we have selected a library of 63 approved and under development antimalarial drugs for in silico screening against the two target proteins Mpro and PLpro of SARS-CoV-2 using several computational methods including molecular docking followed by molecular dynamics simulation, quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) analysis, and structure activity relationship (SAR).

Material and methods

Selection and preparation of the compound library of antimalarial drugs

A total of 63 antimalarial drugs was collected from DrugBank database and already published articles to build the compound library [17, 18]. The structures of the selected compounds were generated in Marvin Sketch v20.4 and saved as.sdf file format for future use. The SMILES of the compounds were loaded to Discovery Studio 2020 (DS 2020) molecular modelling software (Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA, San Diego, USA) and three-dimensional structures were generated using the “Small Molecule” tool of the DS 2020. Then, energy minimization of the compounds was carried out using “Full Minimization” protocol under “Small Molecule” tool using CHARMm-based (Chemistry at Harvard Macromolecular Mechanics) smart minimizer which performs 2000 steps of Steepest Descent followed by Conjugate Gradient algorithm with an energy RMSD gradient of 0.01 kcal/mol. Then, the compound library was saved in a single file for further studies [19].

Preparation of the target proteins and selection of binding sites

The X-ray crystal structures of the two proteins, namely main protease (Mpro) (PDB ID: 6M0K) [20] and papain-like protease (PLpro) (PDB ID: 6WX4) [21], were obtained from the Protein Data Bank websites [22]. To prepare the target proteins for the docking process, first, both proteins were loaded in DS 2020. Then, the targets were cleaned and prepared by the “Prepare Protein” protocol under the “Macromolecules” tool of DS 2020. During cleaning, alternate conformations were deleted, terminal residues were adjusted, and bond orders were corrected. In the preparation process, water molecules were removed from the structure and co-crystal ligands were kept with the proteins. Then, energy minimizations of the enzymes were performed using the CHARMm-based smart minimizer method at maximum steps of 200 and energy RMSD gradient of 0.1 kcal/mol [19].

The binding site spheres for the two proteins were selected around the co-crystal inhibitors using the “Edit and Define Binding Site” method under the “Receptor-Ligand Interactions” tools of DS 2020. The active binding site sphere of Mpro had the coordinates of X: − 12.074224, Y: 12.007731, Z: 69.419457 and radius 8.169772 Å; and PLpro had the coordinates of X: 8.904486, Y: − 27.443594, Z: − 37.926085 and radius 10.323938 Å (Fig. S1). The validation of the binding sites and docking study was done by redocking the co-crystal inhibitors in the selected active binding sites [23].

Preliminary in silico screening for binding affinity and safety

Molecular docking study

The compound library was docked with the two selected targets using simulation-based docking protocol “CDocker” of DS 2020 [24]. CDocker uses a CHARMm-based molecular dynamics (MD) algorithm to dock compounds into the active binding site of a receptor. In this process, high-temperature molecular dynamics was used to generate random conformations of the compounds at the active binding site. Finally, compound poses were created using random rigid-body rotations followed by simulated annealing. Then, a final minimization of the complex was done to refine the different poses of the compound at the binding site. After docking, the binding poses of the compounds were analyzed and compared with the binding poses of the co-crystal ligands of the respective two target proteins.

Determination of scoring functions

The compounds which showed better results than the co-crystal inhibitor (FJC) were taken for determining the different docking scores based on the CDocker energy. Different scoring functions of the best pose of the compounds like LigScore1, LigScore2, piecewise linear potentials (-PLP1 and -PLP2), and potential of mean force (-PMF) were determined to evaluate molecular binding affinity of the compounds. The scoring functions of the co-crystal inhibitors were taken as control to evaluate the test compounds against the two respective targets [25].

Toxicity analysis

The filtered compounds obtained from the docking study were analyzed for different types of toxicity using the “Toxicity Prediction” protocol under the “Small Molecules” tool of the DS 2020. In the toxicity analysis, different parameters like carcinogenicity (NTP (National Toxicology Program) and FDA (Food and Drug Administration) Rodent Carcinogenicity), mutagenicity (Ames Mutagenicity), Developmental Toxicity Potential (DTP), oral LD50 (Rat Oral LD50, lethal dose 50), and skin irritation (Skin Irritancy) were determined. The “Toxicity Prediction” protocol uses TOPKAT (Toxicity Prediction by Komputer Assisted Technology) models which accurately and rapidly assess the toxicity of compounds based on their 2D molecular structure. TOPKAT uses range-validated Quantitative Structure–Toxicity Relationship (QSTR) models for assessing specific toxicological endpoints of test compounds [26].

Molecular dynamic simulation study

The compound that showed the best binding affinity against the selected target protein was further considered for molecular dynamics (MD) simulation study using DS 2020. MD simulation is considered a common method for the investigation of biomolecular interaction along with their conformational dynamics [27]. The best protein–ligand complex generated from the docking study was taken for MD simulation study along with the original crystal structure of the target proteins bound with the co-crystal inhibitors. The protein–ligand complexes were initially cleaned and prepared using the macromolecule tool of DS 2020. Then, the complexes were solvated using explicit periodical boundary condition in a cubic box of water of size 10 Å × 10 Å × 10 Å. The system was neutralized by adding 0.15 M NaCl during the solvation process. The solvated systems were energy minimized (5000 steps steepest descent and 5000 steps conjugate gradient with energy RMSD (root mean square deviation) gradient 0.01 kcal/mol), heated (20 ps), and equilibrated (500 ps) using the “Standard Dynamic Cascade” protocol of DS 2020. After that, 50-ns production was run in NPT ensemble at 300 K for the whole protein–ligand complexes where snapshots were saved every 2 ps. For the electrostatics calculations, the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method was used, and to constrain bonds containing hydrogen the SHAKE algorithm was used with the time step of 2 fs. After completing the simulation, RMSD, RMSF (root mean square fluctuation), and ROG (radius of gyration) were computed by taking the starting structure as a reference to evaluate the conformational changes of the protein–ligand complexes. Throughout the simulation, the distances of different hydrogen bonds formed were also monitored and analyzed. Finally, different non-bond interactions were also analyzed from the average interaction structure of the protein–ligand complexes and compared with the interactions obtained from the starting structures [21–24].

MM-PBSA-based binding free energy calculation

The MM-PBSA-based calculation of binding free energy (ΔG) is one of the important parameters to estimate the binding affinity of a compound to a biological macromolecule or target as well as thermodynamic stability of the protein–ligand complex [30]. This technique provides a fast and accurate prediction of absolute binding affinity of a compound within the active binding site of a target protein in the form of binding free energy which is very important for stability and particular potency of the compound [31]. Hence, after MD simulation, the binding free energies for each protein–ligand complex were calculated using the “Binding Free Energy—Single Trajectory” protocol of DS 2020 using the MM-PBSA method. In the analysis, the binding free energies of all the generated conformations were calculated and, finally, the average binding free energy (ΔG) was determined for each protein–ligand complex.

Prediction of inhibitory potential

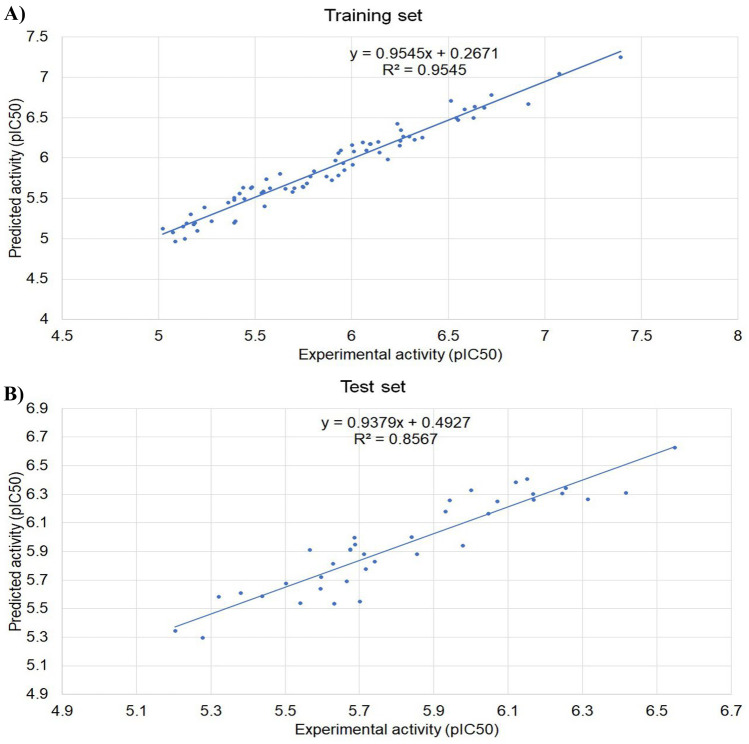

The possible inhibitory potentials of the final hit and the co-crystal inhibitor (FJC) were predicted using 3D-QSAR (quantitative structure activity relationship) analysis. To build the model, a dataset of synthesized Mpro inhibitors were collected from PostEra website [32] along with their inhibitory potential in the form of IC50 values. A total of 111 compounds (IC50 range 0.0405–9.5268 µm) were collected from the website and their IC50 values were converted into pIC50 values using an online tool before using them to build the model [33]. Initially, the compounds were aligned using the molecular overlay method (50% electrostatic and 50% steric fields), which were then divided into a training set (73 compounds) and a test set (38 compounds) based on molecular diversity in each group. The Grid-Based Temp model was generated using two probe types to calculate energy grids, which indicates electrostatics and steric effects. The regression analysis was performed by cross-validated partial least square (PLS) method of leave-one-out (LOO). The pIC50 values served as dependent variables to build the model which validates the test set for stability and predictability.

HYDE analysis

Different atoms and fragments have different roles in the binding affinity as well as biological activity of a molecule. The proper analysis of these roles of the compounds can provide valuable information for further development of new drug candidates with improved efficacy as well as safety. Hence, the final hit and the co-crystal inhibitor were further analyzed using the SeeSAR 10.1 bioinformatics tool to analyze the possible atoms/fragments having significant contributions towards the inhibitory potential of the compounds against Mpro [34, 35].

Results and discussion

Preliminary in silico screening for binding affinity and safety

In the simulation-based docking study, CDocker energy (kcal/mol) was considered for filtering the best compounds because it provides comparatively accurate information regarding the binding affinity of a compound in the active site [24]. In the case of Mpro, out of the 63 compounds, 15 compounds showed better CDocker energy in comparison to the co-crystal ligand (FJC or 11b; − 21 = − 0.1189 kcal/mol) which is an irreversible inhibitor of Mpro with IC50 value 0.51 µm (Table S1). But in the case of PLpro, none of the compounds showed better results than the co-crystal ligand (VIR51) (Table S2). Therefore, only those 15 compounds having better CDocker energy value than FJC were considered for further analysis. For all the 15 compounds and the co-crystal inhibitor FJC, some other parameters like LigScores, -PLP scores, and -PMF scores were also determined. These scoring functions like LigScores indicate polar attraction between ligand and receptor whereas -PLP scores evaluate hydrogen bond interactions. -PMF computes Helmholtz binding free interaction energies between ligands and the receptor. The docking scores of all the selected compounds are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Docking scores of the best compounds in comparison to the co-crystal inhibitor

| Name | LigScore1 | LigScore2 | -PLP1 | -PLP2 | -PMF | CDocker energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FJC | 3.71 | 4.7 | 82.4 | 70.27 | 22.89 | − 21.119 |

| Trimethoprim | 3.44 | 4.63 | 65.54 | 59.04 | − 7.55 | − 28.263 |

| Methylene blue | 2.46 | 4.69 | 69.54 | 60.3 | 36.2 | − 23.691 |

| Primaquine | 2.1 | 4.54 | 60.8 | 56.27 | 17.48 | − 22.061 |

| Pyrimethamine | 2.61 | 4.51 | 53.93 | 50.81 | 36.88 | − 21.131 |

| Acediasulfone | 4.05 | 4.75 | 61.13 | 59.64 | 48.65 | − 26.122 |

| Cycloguanil | 1.89 | 4.05 | 48.6 | 38.88 | 35.58 | − 21.145 |

| Naphthoquine | 3.3 | 5.45 | 88.19 | 80.12 | 49.09 | − 23.526 |

| WR99210 | 3.05 | 5.09 | 67.49 | 56.8 | 35.12 | − 27.449 |

| Propafenone | 2.43 | 4.79 | 67.84 | 62.64 | 35.58 | − 34.266 |

| Decoquinate | 2.35 | 4.85 | 76.53 | 59.59 | 63.98 | − 34.215 |

| NITD-731 | 4.3 | 5.42 | 93.36 | 86.47 | 35.04 | − 36.581 |

| Epoxomicin | 4.91 | 5.85 | 96.59 | 80.07 | 58.89 | − 57.511 |

| P218 | 4.49 | 5.15 | 85.32 | 69.8 | 7.07 | − 44.36 |

| Albitiazolium | 2.66 | 4.85 | 72.25 | 63.59 | 37.45 | − 37.048 |

| SSJ-183 | 2.43 | 4.98 | 88.99 | 71.94 | 50.08 | − 24.889 |

Furthermore, the selected 15 compounds were considered for toxicity assessment. Out of these 15 compounds, only 3 compounds, epoxomicin, NITD-731, and P218, were found to be safe concerning carcinogenicity (NTP and FDA), mutagenicity, developmental toxicity prediction (DTP) index, and skin irritancy in the toxicity analysis (Table 2). Among the 3 compounds, epoxomicin showed the best CDocker energy (− 57.5107 kcal/mol) suggesting the presence of higher binding affinity of epoxomicin towards the binding site of Mpro. Hence, epoxomicin was selected for further molecular dynamic simulation study.

Table 2.

Toxicity analysis of the filtered compounds from docking study

| Name | NTP | FDA | Ames mutagenicity | DTP | Skin irritancy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Rat | Mouse | Rat | ||||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | ||||

| Trimethoprim | C | C | NC | C | NC | SC | SC | MC | NM | T | None |

| Methylene blue | NC | NC | C | C | MC | MC | SC | SC | M | NT | Mild |

| Primaquine | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | SC | NC | NC | M | NT | None |

| Pyrimethamine | NC | C | NC | C | NC | NC | NC | NC | NM | NT | None |

| Acediasulfone | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | SC | SC | MC | NM | NT | None |

| Cycloguanil | NC | C | NC | NC | NC | SC | NC | NC | NM | NT | None |

| Naphthoquine | NC | C | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NM | T | None |

| WR99210 | NC | C | NC | C | NC | NC | NC | NC | NM | NT | Mild |

| Propafenone | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NM | T | None |

| Decoquinate | NC | C | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NM | NT | None |

| NITD-731 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NM | NT | None |

| Epoxomicin | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NM | NT | None |

| P218 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NM | NT | None |

| Albitiazolium | NC | NC | NC | NC | MC | MC | SC | SC | NM | NT | Mild |

| SSJ-183 | NC | C | C | C | MC | NC | SC | NC | NM | NT | Mild |

C carcinogenic, NC non-carcinogenic, SC single-carcinogenic, MC multiple-carcinogenic, NM non-mutagenic, M mutagenic, T toxic, NT non-toxic

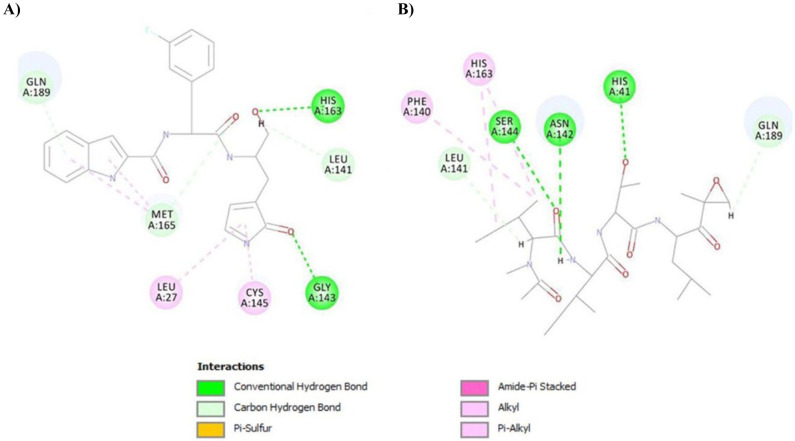

On analyzing the compound-target interactions, it was observed that epoxomicin formed three conventional hydrogen bond interactions with His41, Asn142, and Ser144; two carbon hydrogen bond interactions with Leu141 and Gln189; and three hydrophobic interactions (Pi-Alkyl) with Phe140 and His163. On the other hand, FJC formed two conventional hydrogen bonds with Gly143 and His163; three carbon hydrogen bonds with Leu141, Met165, and Gln189; and four hydrophobic interactions with Leu27, Cys145, and Met165. It is worth mentioning that His41 and Cys145 are present in the catalytic site of Mpro and they are involved in the bond formation with epoxomicin and FJC respectively. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that binding of epoxomicin and FJC may affect the catalytic activity of Mpro (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Interactions of the compounds in the active binding site of Mpro with (A) FJC and (B) epoxomicin

Molecular dynamics simulation study

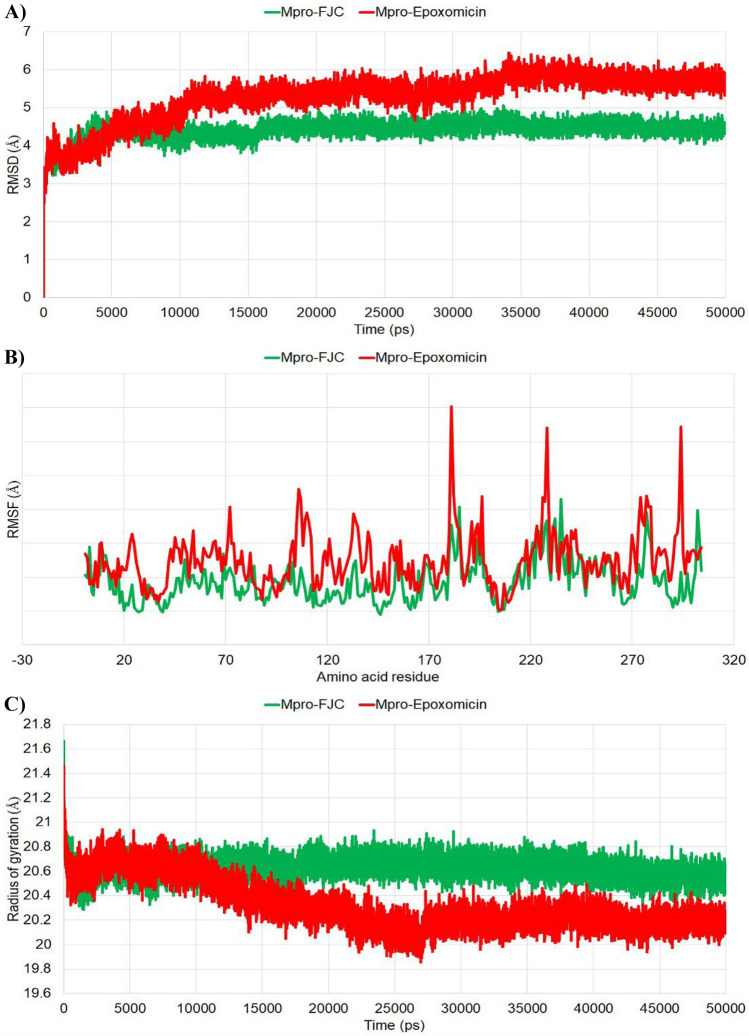

To understand the binding of ligand to the receptor, molecular dynamics simulation was performed as this in silico approach mimics the real physiological conditions of in vitro and in vivo wet lab experiments [36]. Hence, the RMSD, RMSF, and ROG of the Mpro-epoxomicin complex were calculated for the 50-ns simulation period and compared with the control (Mpro-FJC complex). The whole protein–ligand complexes were considered to calculate the RMSD, RMSF, and ROG of the test and the control complexes. After the completion of the 50-ns simulation, the RMSD plots for both the complexes were analyzed. From the RMSD plot, it was observed that Mpro-FJC reached the plateau state within 5 ns and it maintained the deviations within or near ~ 5 Å until the end of the simulation trajectory. On the other hand, the Mpro-epoxomicin complex reached the plateau state after 11 ns and maintained the deviations near 6 Å (Fig. 2A). The fluctuations of the individual residues within the simulation period were plotted where the fluctuations of the residues of Mpro-epoxomicin were found to be more in comparison to the Mpro-FJC complex (Fig. 2B). The amino acid residues in Mpro-epoxomicin had an average RMSF of 1.252 Å whereas in Mpro-FJC it was 0.938 Å. All the residues fluctuated below 2 Å in Mpro-FJC complex. On the other hand, in Mpro-epoxomicin, some of the residues (Asn72, Ile106, Gln107, Phe181, Thr196, Thr226, Leu227, Asn228, Asp229, Asn274, Asn277, Arg279, and Phe294) varied over 2 Å. Considering the catalytic residues, i.e., His41 and Cys145, it was observed that His41 has a RMSF value of 0.540 Å in the Mpro-FJC complex and 0.849 Å in the Mpro-epoxomicin complex. On the other hand, Cys145 showed a RMSF value of 0.496 Å in Mpro-FJC and 1.083 Å in Mpro-epoxomicin. The amino acid residues in Mpro-epoxomicin were slightly more altered during the simulation period of 50 ns. From the ROG analysis, it was found that the Mpro-FJC complex was consistent and stable within the simulation period but Mpro-epoxomicin started to form a more compact complex from 17 ns onwards (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Different stability-indicating parameters obtained from the molecular dynamic simulation study: (A) RMSD, (B) RMSF, and (C) ROG

In this study, we further analyzed the interactions of the compounds with Mpro from the average protein–ligand complex obtained after 50-ns MD simulation (Fig. 3) and also monitored the formation of H-bonds during the simulation period. After MD simulation, the co-crystal inhibitor FJC formed twelve conventional hydrogen bonds with Thr25, Thr26, Asn142, Ser144, Cys145, His163, Glu166, His172, Ala191, and Gln192; three carbon hydrogen bonds with Thr25, Leu141, and Asn142; and five hydrophobic interactions (Amide-Pi Stacked, Pi-Alkyl, Pi-Anion) with Cys44, Met49, Leu141, and Leu191 in the active site of the target protein. On the other hand, epoxomicin formed five conventional hydrogen bonds with Thr25, His41, Cys44, and Asn142; two carbon hydrogen bonds with His41 and Asn142; and four hydrophobic interactions (Alkyl) with Leu27 and Cys145 in the active site. From the interactions, it was observed that FJC formed conventional hydrogen bond interaction with one catalytic residue Cys145, but did not form any interaction with His41. On the other hand, epoxomicin interacted with both the catalytic residues of Mpro (His41 and Cys145) forming conventional and carbon hydrogen bonds with His41 and hydrophobic bond (Alkyl) with Cys145.

Fig. 3.

Interactions of the compounds obtained from the average protein–ligand complexes generated after 50 ns of simulation; (A) surface model of Mpro-FJC complex, (B) surface model of Mpro-epoxomicin complex, (C) 2D structure of Mpro-FJC complex, (D) 2D structure of Mpro-epoxomicin complex after 50 ns of simulation

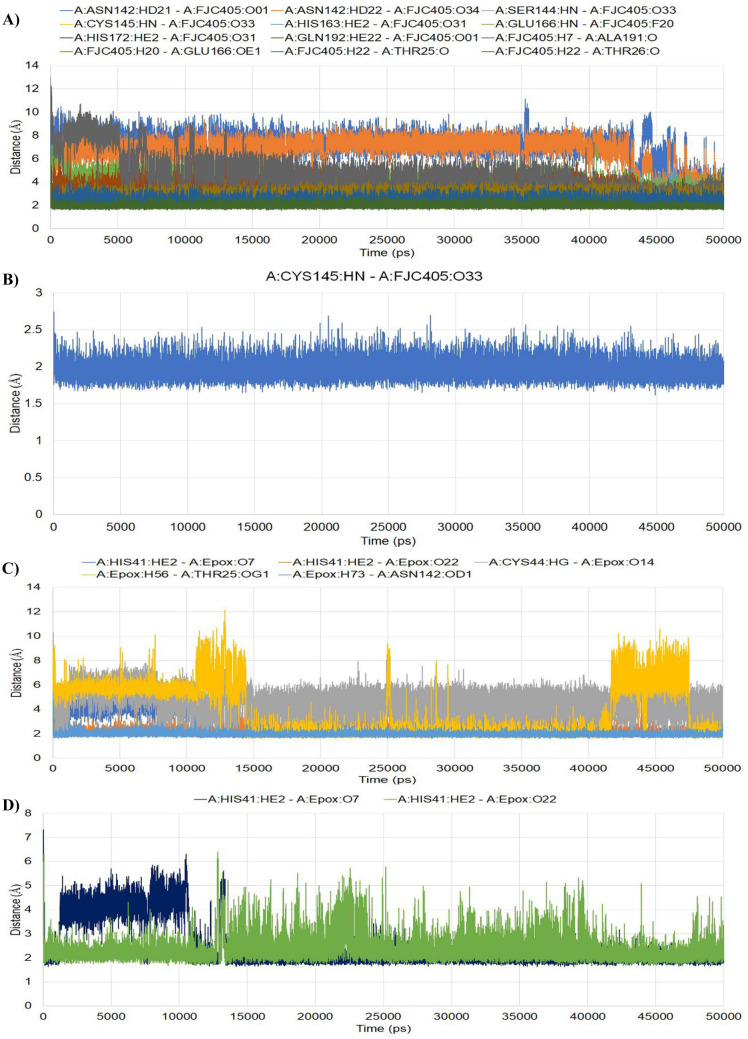

The number of H-bonds formed and their distances within the simulation period for each conformation were generated and depicted in Fig. 4. In Mpro-FJC complex, a total of twelve hydrogen bonds were found where one of them was formed with Cys145 residue. The distance of this H-bond was very stable and maintained an average of 1.961 Å during the simulation period. In the case of Mpro-epoxomicin complex, a total of five H-bonds were found where two of them were formed with His41 residue. One of them was stabilized after 11 ns of simulation and maintained the average distance of 2.456 Å during the simulation period. The other H-bond fluctuated very less and maintained an average distance of 2.353 Å during the simulation period.

Fig. 4.

Fluctuations of distances of the H-bonds formed during the simulation period: (A) Mpro-FJC, (B) H-bond with Cys145 in Mpro-FJC, (C) Mpro-epoxomicin, (D) H-bonds with His41 residue in Mpro-epoxomicin

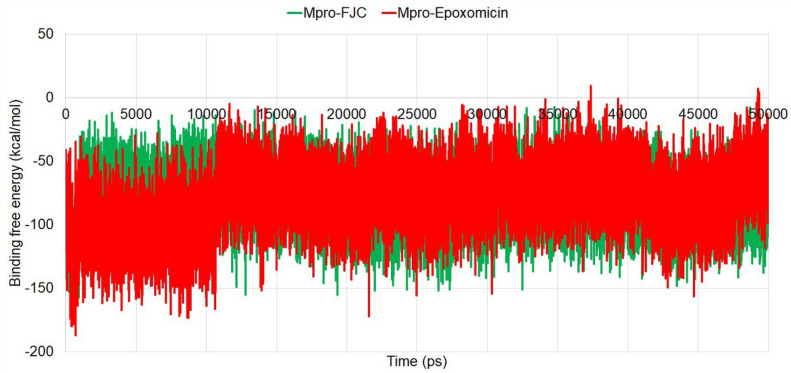

MM-PBSA-based binding free energy

The binding free energies (ΔG) of the protein–ligand complexes indicate the tendency of forming complexes by the ligands and their thermodynamic stability; hence, they can directly relate to the potency of a compound in terms of inhibition or activation. In this study, the MM-PBSA-based approach was used to calculate the ΔG of all the conformations generated during the 50-ns simulation and finally the average value was determined. After calculation, the average ΔG of the Mpro-epoxomicin complex was found to be similar (− 79.315 kcal/mol) with the average ΔG of Mpro-FJC complex (− 79.105 kcal/mol) which indicated the formation of a stable complex with spontaneous interaction similar to the co-crystal inhibitor (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Binding free energies of the two protein–ligand complexes during the simulation period

Prediction of inhibitory potential

The predicted activity (IC50) of the compounds was determined with the help of 3D-QSAR analysis. In this study, the three-dimensional (3D) structures of a set of compounds were used to calculate the energy potential in the 3D-QSAR method. The calculated potential energy was then used as descriptors to build the 3D-QSAR model to correlate the 3D structures and their biological activities. The generated QSAR model gives the information on the correlation between the molecular field and the biological activities of the compounds [37]. By using the following linear equation, the predicted activity, i.e., IC50, of the compounds and control was determined.

where NEP denotes the number of descriptors of electrostatic potential (EP), VEP is the electrostatic potential value on a grid point, and CEP(i) is the model coefficient for EP descriptor i. Similarly, NVDW, CVDW(i), and VVDW denote the number of descriptors of van der Waals (VDW) interaction, the model coefficient for VDW descriptor i, and VDW interaction energy on a grid point respectively. The generated VDW and EP grids aligned with the training set are given in supplementary materials (Fig. S3) whereas the alignment of the best poses of the reference compound, i.e., co-crystal inhibitor FJC (or 11b), and the test compound epoxomicin is given in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Alignment of the compounds with the (A) VDW and (B) EP grids; (C) compound with green colour is the FJC and that with the red colour is the epoxomicin

The linear plot of the training set and the test set is depicted in Fig. 7. The determined R2 values for the training set were found to be 0.9545 and 0.8567 for the test set during validation. From the 3D-QSAR analysis, the predicted IC50 value of FJC was observed to be 0.0945 μM whereas the reported IC50 of FJC against Mpro was 0.040 ± 0.002 μM [20]. Both the predicted and reported IC50 values of FJC lie in the same order of magnitude. On the other hand, the predicted IC50 of the test drug epoxomicin was observed to be 0.4447 μM.

Fig. 7.

3D-QSAR model for the (A) training set and (B) test set

Since epoxomicin is an established drug for the treatment of malaria and other diseases, so, it was considered for further structure activity analysis to assess the role of different fragments and individual atoms towards the overall binding affinity.

HYDE analysis

From the HYDE analysis, we tried to find out the role of the individual atoms along with the different possible fragments (pharmacophore) of the molecules in the overall binding affinity in the active site of the target Mpro [35, 38]. In the case of co-crystal inhibitor FJC, we identified two fragments or pharmacophore of the molecule having good contributions towards the binding affinity. Most of the atoms of these two fragments had good or positive contributions in the binding affinity as indicated by the green coronas obtained from the HYDE analysis (Fig. 8A1, A2, and A3). But in the case of fragment 2, the oxygen atom present in the pyrrolidone ring has negative impact (red corona, 1.5 kj/mol) in the binding affinity. Similarly, in the case of epoxomicin, two fragments were identified having good contributions towards the overall binding affinity of the molecule. Those two fragments are indicated by the green coronas. On the other hand, overall atoms of four groups (two -CH3 and two -NH- groups) of epoxomicin showed bad or negative contributions (red coronas) towards the overall binding affinity of the molecule which were not part of the above-mentioned fragments having good contribution (Fig. 8B1, B2, and B3).

Fig. 8.

Structure activity analysis of (panel A) co-crystal inhibitor (FJC) and (panel B) epoxomicin by HYDE analysis

Conclusion

The shortest possible way to combat with the newly emerging COVID-19 pandemic is to find a new drug from the old ones and based on this we designed the present study. Already hydroxychloroquine from antimalarial categories gained attention from the scientists and research organization as a possible drug against the novel coronavirus. But due to significant adverse effects in comparison to the low therapeutic benefits, the WHO decided to stop the trials of this drug. Considering these facts, we selected the library of approved and under development antimalarial drugs to virtually screen against vital targets of the novel virus to find out possible new drugs from these categories. In our study, we found a drug epoxomicin that showed high binding affinity in the active site of SARS-CoV-2 target Mpro. From the in silico studies and structure activity relationship analysis, it was observed that the drug epoxomicin has the possible antiviral capability against COVID-19 by inhibiting the function of Mpro. But it needs to be verified by in vitro/in vivo studies before clinical experiments. Epoxomicin, a selective proteasome inhibitor, is a clinically relevant antimalarial drug which has potent gametocytocidal activity. From this preliminary study, we have found the possible repurposing of this drug against COVID-19 and it might be able to serve the purpose individually or in combination with other antiviral drugs. Hence, we suggest for evaluating the effectiveness of the drug against the deadly virus to find out its possible antiviral roles.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the Drug Design Software facility of the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Dibrugarh University, established by the support of University Grants Commission, New Delhi (India), under UGC-SAP (DRS-I) [F.3-13/2016/DRS-I (SAP-II)]. Neelutpal Gogoi also acknowledges the support from BioSolveIT GmbH, Sankt Augustin, Germany, for providing the special licence of SeeSAR software to carry out a part of the computational analysis.

Author contribution

NG, BG, PC, and AKG developed the idea of the research work. NG performed the software-based experimental part. BG analyzed the results and PC verified them. AKG, AD, and DC provided input in the development stage of the manuscript. Finally, all the authors finalized and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhou P, Lou YX, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 26 May 2021

- 3.Nagar PR, Gajjar ND, Dhameliya TM (2021) In search of SARS CoV-2 replication inhibitors: virtual screening, molecular dynamics simulations and ADMET analysis. J Mol Struct 1246. 10.1016/J.MOLSTRUC.2021.131190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, et al. COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020;24:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bojadzic D, Alcazar O, Chen J, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of the coronavirus spike: ACE2 protein-protein interaction as blockers of viral attachment and entry for SARS-CoV-2. ACS Infect Dis. 2021;7:1519–1534. doi: 10.1021/ACSINFECDIS.1C00070/SUPPL_FILE/ID1C00070_SI_001.PDF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhameliya TM, Nagar PR, Gajjar ND (2022) Systematic virtual screening in search of SARS CoV-2 inhibitors against spike glycoprotein: pharmacophore screening, molecular docking, ADMET analysis and MD simulations. Mol Divers. 10.1007/S11030-022-10394-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Hodgson SH, Mansatta K, Mallett G, et al. What defines an efficacious COVID-19 vaccine? A review of the challenges assessing the clinical efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:e26–e35. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30773-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu C, Liu Y, Yang Y, et al. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:766–788. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gioia M, Ciaccio C, Calligari P et al (2020) Role of proteolytic enzymes in the COVID-19 infection and promising therapeutic approaches. Biochem Pharmacol 182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Ullrich S, Nitsche C (2020) The SARS-CoV-2 main protease as drug target. Bioorganic Med Chem Lett 30:127377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Báez-Santos YM, St. John SE, Mesecar AD. The SARS-coronavirus papain-like protease: structure, function and inhibition by designed antiviral compounds. Antiviral Res. 2015;115:21–38. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amin SA, Banerjee S, Ghosh K, et al. Protease targeted COVID-19 drug discovery and its challenges: insight into viral main protease (Mpro) and papain-like protease (PLpro) inhibitors. Bioorganic Med Chem. 2021;29:115860. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gajjar ND, Dhameliya TM, Shah GB (2021) In search of RdRp and Mpro inhibitors against SARS CoV-2: molecular docking, molecular dynamic simulations and ADMET analysis. J Mol Struct 1239. 10.1016/J.MOLSTRUC.2021.130488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Phadke M, Saunik S. COVID-19 treatment by repurposing drugs until the vaccine is in sight. Drug Dev Res. 2020;81:541–543. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viveiros Rosa SG, Santos WC (2020) Clinical trials on drug repositioning for COVID-19 treatment. Rev Panam Salud Publica/Pan Am J Public Heal 44. 10.26633/RPSP.2020.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biamonte MA, Wanner J, Le Roch KG. Recent advances in malaria drug discovery. Bioorganic Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:2829–2843. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gogoi N, Chetia D, Gogoi B, Das A. Multiple-targets directed screening of flavonoid compounds from citrus species to find out antimalarial lead with predicted mode of action: an in silico and whole cell-based in vitro approach. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2019;17:69–82. doi: 10.2174/1573409916666191226103000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai W, Zhang B, Jiang XM et al (2020) Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science (80- )368:1331–1335. 10.1126/science.abb4489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Rut W, Lv Z, Zmudzinski M, et al. Activity profiling and crystal structures of inhibitor-bound SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease: a framework for anti–COVID-19 drug design. Sci Adv. 2020;6:4596–4612. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain AN. Bias, reporting, and sharing: computational evaluations of docking methods. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2008;22:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s10822-007-9151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu G, Robertson DH, Brooks CL, Vieth M. Detailed analysis of grid-based molecular docking: a case study of CDOCKER - a CHARMm-based MD docking algorithm. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1549–1562. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin CH, Chang TT, Sun MF, et al. Potent inhibitor design against h1n1 swine influenza: structure-based and molecular dynamics analysis for m2 inhibitors from traditional chinese medicine database. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2011;28:471–482. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2011.10508589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dearden JC. In silico prediction of drug toxicity. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2003;17:119–127. doi: 10.1023/A:1025361621494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padhi AK, Rath SL, Tripathi T. Accelerating COVID-19 research using molecular dynamics simulation. J Phys Chem B. 2021;125:9078–9091. doi: 10.1021/ACS.JPCB.1C04556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noha SM, Schmidhammer H, Spetea M. Molecular docking, molecular dynamics, and structure-activity relationship explorations of 14-oxygenated N-methylmorphinan-6-ones as potent μ-opioid receptor agonists. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8:1327–1337. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai CY, Chang TT, Sun MF, et al. Molecular dynamics analysis of potent inhibitors of M2 proton channel against H1N1 swine influenza virus. Mol Simul. 2011;37:250–256. doi: 10.1080/08927022.2010.543972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Genheden S, Ryde U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2015;10:449–461. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rastelli G, Del Rio A, Degliesposti G, Sgobba M. Fast and accurate predictions of binding free energies using MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:797–810. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.PostEra | COVID-19. https://covid.postera.ai/covid. Accessed 1 Aug 2020

- 33.Chandrabose Selvaraj, Sunil Kumar Tripathi K. K. Reddy and S. Singh Tool development for Prediction of pIC50 values from the IC50 values - A pIC50 value calculator | Association of Biotechnology and Pharmacy. In: 2011. http://www.abap.co.in/tool-development-prediction-pic50-values-ic50-values-pic50-value-calculator. Accessed 26 May 2021

- 34.SeeSAR • your modern everyday drug design dashboard. https://www.biosolveit.de/products/seesar/. Accessed 26 May 2021

- 35.Gogoi N, Chowdhury P, Goswami AK, et al. Computational guided identification of a citrus flavonoid as potential inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Mol Divers. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11030-020-10150-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahanta S, Chowdhury P, Gogoi N et al (2020) Potential anti-viral activity of approved repurposed drug against main protease of SARS-CoV-2: an in silico based approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Ahmed N, Anwar S, Htar TT (2017) Docking based 3D-QSAR Study of tricyclic guanidine analogues of batzelladine K As anti-malarial agents. Front Chem 5. 10.3389/fchem.2017.00036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Schneider N, Hindle S, Lange G, et al. Substantial improvements in large-scale redocking and screening using the novel HYDE scoring function. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2012;26:701–723. doi: 10.1007/s10822-011-9531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.