Abstract

In May 2020, Baltimore City, Maryland, implemented the Lord Baltimore Triage, Respite, and Isolation Center (LBTC), a multiagency COVID-19 isolation and quarantine site tailored for people experiencing homelessness. In the first year, 2020 individuals were served, 78% completed isolation at LBTC, and 6% were transferred to a hospital. Successful isolation can mitigate outbreaks in shelters and residential recovery programs, and planning for sustainable isolation services integrated within these settings is critical as the COVID-19 pandemic continues. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(6):876–880. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306778)

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, susceptibility of populations made vulnerable because of structural inequities related to race, income, and other circumstances became apparent.1–3 Prior to COVID-19, housing instability and homelessness were recognized as being associated with increased morbidity and mortality.4,5 Living in congregate settings such as shelters placed an already medically vulnerable population at high risk of COVID-19 infection3 with the potential for poor outcomes. In response, jurisdictions across the United States quickly established isolation and quarantine (I&Q) sites for individuals experiencing homelessness to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks in shelter settings, reduce community spread, and provide clinical monitoring for marginalized populations.6–9 Here we describe implementation activities and data from the first year (May 12, 2020, to May 11, 2021) of the COVID-19 isolation hotel in Baltimore City, Maryland.

INTERVENTION

The Baltimore City Health Department and the Mayor’s Office of Homeless Services created a public–private partnership with the University of Maryland Medical System and the Lord Baltimore Hotel to open the 300-room Lord Baltimore Triage, Respite, and Isolation Center (LBTC) for COVID-19 I&Q support.

PLACE AND TIME

LBTC, located at the historic Lord Baltimore Hotel, opened on May 12, 2020, and services are ongoing; here we present one year of data through May 11, 2021.

PERSON

Services are designed to meet the needs of people experiencing homelessness or in recovery programs, but accommodations are open to any individual or family in the community requiring COVID-19 I&Q and are not restricted to Baltimore City residents.

PURPOSE

LBTC’s mission is to (1) limit the spread of COVID-19 in high-risk settings and among medically vulnerable populations, (2) ensure the safety and well-being of individuals and families during their I&Q, (3) provide additional support to residents in I&Q to ensure a successful transition after their stay, and (4) provide a dynamic service that can adapt to community needs as the COVID-19 pandemic evolves.

IMPLEMENTATION

LBTC offers clinical support and monitoring for individuals and families who have confirmed COVID-19, who have COVID-19 symptoms and are awaiting test results, or who require quarantine after COVID-19 exposure. Referrals are accepted seven days a week from hospitals and emergency departments, shelters, residential recovery programs (inpatient substance use treatment programs and recovery housing), clinics, other community sites, and individuals who self-refer. The Baltimore City Health Department COVID-19 outbreak team also conducts contact tracing and testing and makes referrals to LBTC for individuals in shelters and recovery programs. Clinical staff complete a telephone intake with a clinical safety checklist for all referrals before acceptance to LBTC. Medical transportation is provided to limit community exposure. Residents undergo a security check to remove weapons and illicit substances.

Several floors of the hotel are considered the “hot zone,” which is designated by physical barriers and includes a separate entrance and elevator bank. Staff wear full personal protective equipment while in the hot zone. Residents are asked to stay in their rooms except when visiting the smoking room, and nonclinical staff are stationed on each floor to ensure resident safety. Meals prepared by the Lord Baltimore Hotel are delivered to residents three times a day.

Clinical staff perform daily resident wellness checks, including symptom screening and checking of vital signs, and provide over-the-counter medications and supplies for a comfortable stay. Staff work with pharmacies and treatment programs to ensure that medications are delivered, including methadone. Clinical staff are on site 24 hours per day for evaluation of medical needs and triage to the hospital. Harm reduction strategies include an alcohol withdrawal protocol with monitored distribution of alcohol and opioid overdose prevention strategies such as same-day buprenorphine initiation, clinical monitoring after suspected drug use, and naloxone training for staff.

National guidelines are followed to determine release from I&Q. A discharge planner ensures a safe discharge location, including arranging placement at a shelter or recovery program if needed. In September 2020, LBTC opened a co-located shelter to provide an additional safe discharge location for homeless residents completing I&Q. Residents in the shelter receive ongoing housing case management and clinical case management services with the goal of securing housing.

EVALUATION

Clinical information and outcome data were prospectively tracked in a secure REDCap database administered by the Baltimore City Health Department for the purposes of clinical monitoring during I&Q. Descriptive statistics are presented for residents served in I&Q in LBTC’s first year of operations.

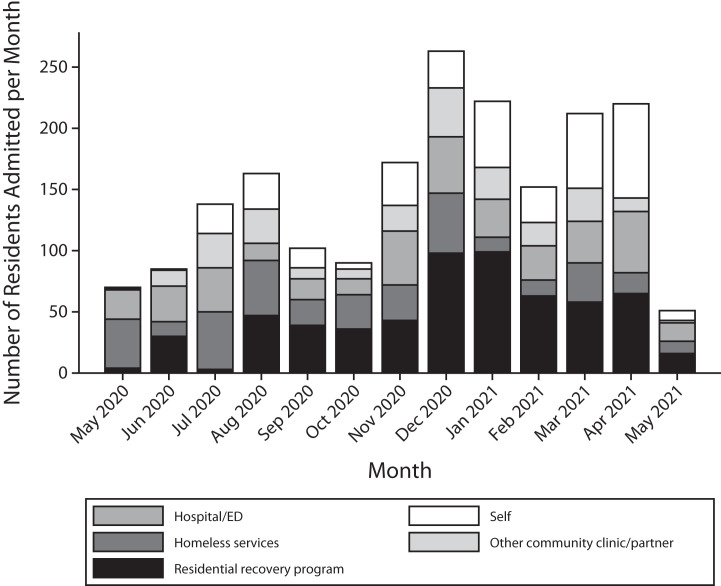

From May 12, 2020, to May 11, 2021, a total of 2020 residents were served in I&Q (Table 1). Of these individuals, 1337 (66.1%) were experiencing homelessness, were unstably housed, or were living in a shelter or residential recovery program setting. The main sources of referrals were residential recovery programs (n = 601; 29.8%), hospitals or emergency departments (n = 387; 19.2%), self-referrals (n = 373; 18.5%), and shelters or Health Care for the Homeless (n = 360; 17.8%). Figure 1 shows the number of residents admitted per month by referral source. During the study period, the peak number of residents was 93 (data not shown), and LBTC never reached full capacity.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Individuals Served in COVID-19 Isolation and Quarantine at the Lord Baltimore Triage, Respite, and Isolation Center: Baltimore, MD, May 12, 2020–May 11, 2021

| Characteristic | Individuals Served (n = 2020), No. (%) |

| Age, y | |

| 0–18 | 116 (5.7) |

| 19–30 | 438 (21.7) |

| 31–50 | 818 (40.5) |

| 51–59 | 443 (21.9) |

| ≥ 60 | 205 (10.1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 1371 (67.9) |

| Female | 627 (31.0) |

| Transgender | 16 (0.8) |

| Missing | 6 (0.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black or African American | 1296 (64.2) |

| White | 419 (20.7) |

| Latinx, Latin–Black, or Latin–White | 105 (5.2) |

| Other | 69 (3.4) |

| Missing | 131 (6.5) |

| COVID-19 status | |

| Positive | 1478 (73.2) |

| Negative | 507 (25.1) |

| Results missing | 35 (1.7) |

| Housing status on intake | |

| Shelter or residential recovery program | 1008 (49.9) |

| Homeless or unstably housed | 329 (16.3) |

| Housed but unable to isolate | 617 (30.5) |

| Missing | 66 (3.3) |

| Referral source | |

| Residential recovery program | 601 (29.8) |

| Hospital or emergency department | 387 (19.2) |

| Self-referred | 373 (18.5) |

| Shelter | 243 (12.0) |

| Health Care for the Homeless | 117 (5.8) |

| Other community clinic or partner | 237 (11.7) |

| Missing | 62 (3.1) |

| Medical and behavioral health status | |

| At least 1 major medical comorbiditya | 919 (45.5) |

| At least 1 mental health diagnosisb | 866 (42.9) |

| Substance use disorderc | 860 (42.6) |

| Major medical, mental health, and substance use disorder | 297 (14.7) |

| Discharge reason | |

| Completed isolation or quarantine | 1580 (78.2) |

| Chose to leave | 265 (13.1) |

| Hospital transfer | 124 (6.1) |

| Administrative discharge | 15 (0.7) |

| Deceased | 1 (0.1) |

| Other | 22 (1.1) |

| Missing | 13 (0.6) |

aIncludes diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, HIV, hepatitis C, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or history of cancer, blood clots, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

bIncludes depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and dementia.

cIncludes reported active illicit use, use of medication for opioid use disorder, and currently in a recovery house or substance use disorder treatment program.

FIGURE 1—

Number of Residents Admitted per Month at the Lord Baltimore Triage, Respite, and Isolation Center, by Referral Source: Baltimore, MD, May 12, 2020–May 11, 2021

Note. ED = emergency department.

A total of 1478 individuals (73.2%) had a positive COVID-19 test result, and the remainder were either symptomatic but tested negative or quarantined after an exposure and remained COVID-19 negative. Medical and behavioral health comorbidities were common; 919 residents (45.5%) had at least one major medical condition, 866 (42.9%) had a major mental health diagnosis, 860 (42.6%) had a substance use disorder, and 297 (14.7%) had all three. The majority of individuals completed I&Q at LBTC (n = 1580; 78.2%). Only 6.1% of residents (n = 124) were transferred to a hospital; 265 (13.1%) chose to leave early, and 15 (0.7%) were discharged for unsafe behavior. Fifty residents (2.5%) transitioned to living in our on-site shelter after completion of I&Q.

ADVERSE EFFECTS

There was one death that was not related to COVID-19.

SUSTAINABILITY

LBTC was designed and implemented within weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic’s initial impact on Baltimore, when the length and scope of the pandemic were unpredictable. Federal COVID-19 emergency funds have been used for this project, and these funding mechanisms will dissipate as the country transitions to recovery planning. LBTC emergency-level operations are not sustainable at the current scale. Strong partnerships between agencies serving people experiencing homelessness, health departments, and clinical partners are needed to develop smaller-scale, long-term isolation services modeled on successful LBTC components.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

LBTC has provided safe and effective I&Q services for Baltimore City and beyond. Clinical support and hospitality services tailored to meet the needs of individuals who are experiencing homelessness and have a substance use disorder led to 78% of people completing I&Q and only 6% being transferred to a higher level of care, rates that are comparable with those of other isolation sites.7 On the basis of prevalence estimates of secondary household infections, LBTC has likely prevented thousands of COVID-19 infections within shelters and recovery programs.10 Isolation services that remove infectious individuals from shelter settings are effective in preventing disease transmission and reducing costs,11 ultimately improving health outcomes and preventing deaths.

Key elements of the LBTC model such as clinical monitoring, infection prevention measures, and harm reduction strategies could be modified and implemented in existing shelter or residential recovery program settings where individual room occupancy is available. Models for integrated clinical and shelter services exist12 and should be expanded as many jurisdictions move toward noncongregate hotel-based shelter care. Integrated on-site clinical services, including infectious disease isolation, medical respite, primary care, and behavioral health services, could prove effective in providing person-centered care to people experiencing homelessness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the more than 2000 people who valued the health of their families and community and chose to isolate at the Lord Baltimore Triage, Respite, and Isolation Center. The success of this project is attributable to the incredible contributions of all partners involved and the hundreds of staff who have worked at the center.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was needed for this research because secondary data were used.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-covid-19-data-snapshot-fact-sheet.pdf

- 2.Gelberg L, Baggett TP.2020.

- 3.Mosites E, Parker EM, Clarke KEN, et al . Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence in homeless shelters—four US cities, March 27–April 15, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(17):521–522. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6917e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkataramani AS, Tsai AC. Housing, housing policy, and deaths of despair. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(1):5–8. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montgomery MP, Paulin HN, Morris A, et al. Establishment of isolation and noncongregate hotels during COVID-19 and symptom evolution among people experiencing homelessness—Atlanta, Georgia, 2020. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27(3):285–294. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs JD, Carter HC, Evans J, et al. Assessment of a hotel-based COVID-19 isolation and quarantine strategy for persons experiencing homelessness. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210490. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordan-Martin NC, Madad S, Alves L, et al. Isolation hotels: a community-based intervention to mitigate the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Secur. 2020;18(5):377–382. doi: 10.1089/hs.2020.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacKenzie OW, Trimbur MC, Vanjani R. An isolation hotel for people experiencing homelessness. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):e41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2022860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madewell ZJ, Yang Y, Longini IM, Halloran ME, Dean NE. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2031756. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baggett TP, Scott JA, Le MH, et al. Clinical outcomes, costs, and cost-effectiveness of strategies for adults experiencing sheltered homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028195. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melnikow J, Ritley D, Evans E, et al. Integrating Care for People Experiencing Homelessness: A Focus on Sacramento County. Davis, CA: University of California, Davis, Center for Healthcare Policy and Research; 2020. [Google Scholar]