Abstract

Adolescents living in low-resource settings lack access to adequate psychological care. The barriers to mental health care in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) include high disease burden, low allocation of resources, lack of national mental health policy and child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) professionals and services, poverty, illiteracy and poor availability of adolescent friendly health services. WHO has recommended a stepped task shifting approach to mental health care in LMIC. Training of non-mental health specialists like peers, teachers, community health workers, paediatricians and primary care physicians by CAMH and framing country-specific evidence-based national mental health policies are vital in overcoming barriers to psychological care in LMIC. Digital technology and telemedicine can be used in providing economical and accessible mental health care services to adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescents, low resources, child and adolescent mental health (CAMH), community-based care, low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), non-mental health specialists, psychological care, task shifting approach

Introduction

Globally, 1/5 of youth have a mental health diagnosis with self-harm the second most common cause of death for adolescents worldwide (World Health Organization (WHO), 2017; WHO, 2020). Low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) are home to nearly 90% of the adolescents in the world (UN Department for Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2017). An estimated 10–15% percent of all diseases in LMIC are found to be neuropsychiatric in nature (Patel, 2007) but are much less likely to receive treatment than their higher-resourced peers. While all countries struggle to keep up with the mental health needs of their adolescent populations, particularly those in rural areas, higher income countries (HIC) lead the way in the development of interventions for prevention and treatment of common mental illnesses. The number of psychiatrists in HIC is 72 times higher than LMIC (van Ginneken et al., 2013). As a result, HIC’s interventions are often resource heavy. They might include professional mental health providers in schools, mandated treatments for those in the juvenile justice system, embedded professional psychology services in primary care and outreach by child and adolescent mental health specialists.

Poverty and nutritional, educational and socioeconomic deprivation contribute to increased prevalence and adverse consequences of mental health disorders in LMIC (Barry et al., 2013). However, low priority is given to mental health by LMIC governments in comparison to more prevalent issues like infectious diseases. There are limited financial resources in health systems, and a lack of trained mental health professionals (Juengsiragulwit, 2015). Only a third of LMIC have a national mental health policy with less than 1% of annual budgetary allocation to mental health (Juengsiragulwit, 2015). The treatment gap for mental disorders in these countries is as high as 90% (Docherty et al., 2017). In LMIC, the median 1-year treated prevalence in the child and adolescent population is 159 per 100,000 with less than 1% of inpatient beds in mental health facilities allocated for children and adolescents (Morris et al., 2011). In countries where non-mental health specialists like doctors, nurses, community health workers and teachers are available to provide mental health services, many lack mental health training. With very few child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) professionals, non-mental health providers may have a very limited or even non-existent referral network for difficult cases (Weobong et al., 2017).

Barriers in implementation of mental health programmes in LMIC

One of the major barriers to the wide spread implementation of the most effective treatment models used by HIC is the dependence on highly skilled professionals who have training in the unique life stage of adolescents. Psychologists, psychiatric nurses, nurse prescribers, and psychiatrists who have a specialist background in adolescent health and medicine, developmental psychology, and/or able to provide psychotropic medications are scarce in LMIC. Even where non-specialist health providers with shorter training such as psychiatric nurses are available, they are overburdened and under supervised. They may also have logistic limitations to their effectiveness such as being pulled to provide care for non-psychiatric disease (often fuelled by the global nursing numbers crisis and brain drain). These nurse providers are often in accelerated programmes with very few and sometimes no opportunities to learn in adolescent mental health treatment environments. This combined with lack of mentorship and continuing education, due to scarcity of CAMH professionals can limit their efficacy in the field.

Even when specially trained mental health providers are available, other factors hinder access to mental health care for youth in LMIC. Although mental health stigma is common in much of the world, its impact can be more far reaching in countries with shifting cultural ideas around mental illness and its manifestations particularly in youth.

Case vignette

This stigma extends to those who provide medical treatment, and may even be expressed by caregivers in schools, and other youth serving centres. Self-stigma experienced by adolescents also compromises access to existing mental health services. As modern youth are increasingly exposed to free information via the internet, they become more knowledgeable about mental illness and its implications. They often worry about the social implications of being identified as mentally ill and struggle with seeking and maintaining care (Maulik et al., 2017).

In many LMIC, youth do not have the legal right to consent and confidentially to their own mental health treatment and may have to depend on caregivers/families for finance, transportation, or information to navigate the mental health system. Many families lack mental health literacy making the burden of services difficult to understand or easy to disregard, some may be personally or culturally averse to adolescents speaking privately to counsellors, and some caregivers have their own stigma against mental illness and thus limit access to services for the youth they care for.

In resource-limited settings, physician- to patient-level difficulties are common. Trained CAMH professionals, for example, might be constrained by the lack of availability of psychotropic medications by ‘stock outs’, or an overall lack of availability in the public system especially when they are not on government essential medications lists. This is exacerbated by the potential need for liquid formulations in young adolescents still learning to take tablets, and weight-based dosing in those who have not yet reached advanced pubertal stages. Mental disorders may require frequent visits to health professionals and as a result, patients with co-morbid chronic disease such as sickle cell anaemia, insulin dependent diabetes, or HIV may struggle the burden of additional medical visits that often disrupt school schedules and other necessary personal milestones.

A framework for mental health services in LMIC

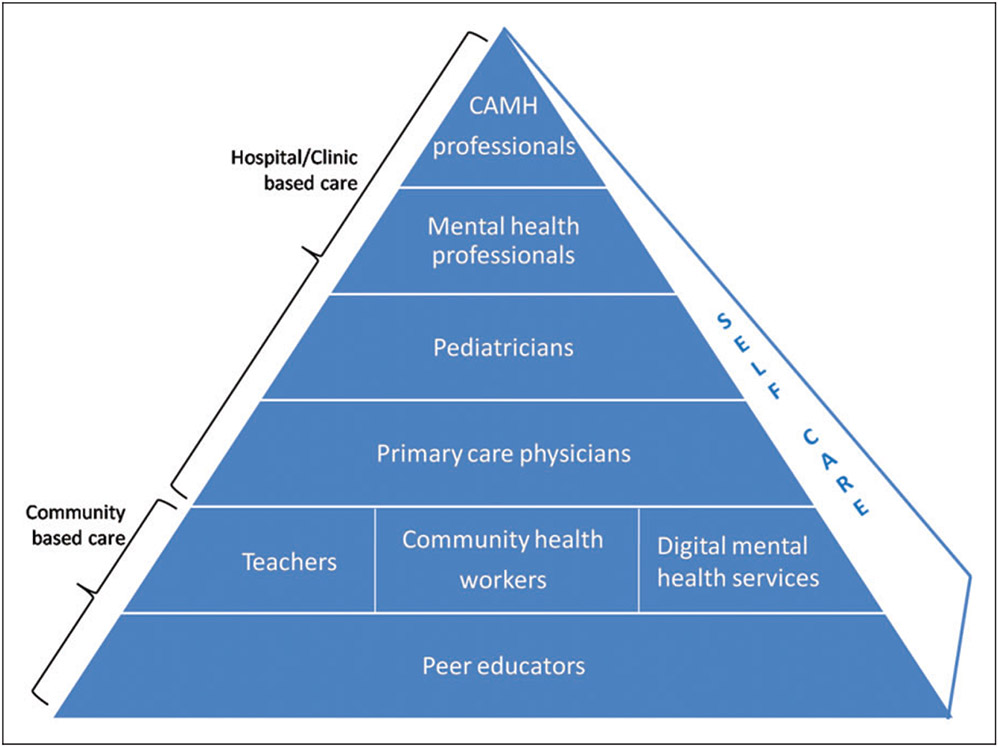

A suggested framework of adolescent mental health services in LMIC at community and hospital levels is shown in Figure 1. Current research has shown that peer support groups, community health workers and school teachers can be effectively trained to deliver community mental health promotion and intervention services. Primary care physicians and paediatricians can upgrade their clinical skills in adolescent mental health care through training programmes. National professional organizations of psychiatrists, psychologists, paediatricians, and CAMH professionals can provide technical guidance for educational materials and conferences, and ideally be available for direct and remote consultation for the most difficult cases.

Figure 1.

Suggested Framework for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMH) in LMIC. Source: Adapted from WHO (2008).

Overcoming barriers in low-resource settings

What can be done to address some of these major barriers particularly the lack in specialized human resources in LMIC? As countries create guidelines and research infrastructure, several exciting areas have emerged to address the crisis of under recognition and lack of treatment. With the WHO framework as a guide (Figure 1), we see that LMIC are indeed implementing integrated frameworks with a strong focus on ‘decentralized’, task shifting, and community-based mental health care.

Community-based care

Peer educators

There are several programmes that use peers as liaisons for youth. This may involve youth groups that can be a source of psychosocial support, fun and relatability for youth known to be at high risk for mental health concerns such as those living with HIV. The activities of the social groups, such as the Teen Club models found throughout Southern Africa, focus on general activities and life skills presented in fun and social settings by youth trained to provide general support (MacKenzie et al., 2017). There may also be one-on-one peer support programmes where older adolescent and young adults might be paired with youth who have mental health struggles. These youth peer educators are often ‘model patients’, who are themselves showing signs of sound mental and physical health. They act as mentors and provide education and care for struggling youth. These peer educators could also undergo skill training to become youth lay counsellors. While peer education models based on promoting self-care and disease management are common, peer lay counsellor roles are in their infancy. Beyond providing training in life skills, as seen in the Zvindiri programme in Zimbabwe, peer educators can be further trained in problem-solving therapy and evidence-based psychological intervention (Willis et al., 2018). Youth in this model act as community health workers. Modules are being developed to ensure adequate training, supervision, and mental health support for these youth lay counsellors.

Community health workers/lay counsellors

Community health workers have emerged as valuable members of mental health teams in countries that have implemented trained lay counsellor programmes. Projects in India and Zimbabwe have emerged as leaders in task shifting using lay counsellors among LMIC and HIC alike (Chibanda et al., 2016; Patel, 2017). These lay counsellors are trained and supervised community health workers who provide psychological treatment, psychoeducation and referral as needed (Nadkarni et al., 2017; Weobong et al., 2017). This task shifting stepped approach to care is becoming more common as it is cost-effective and addresses a great need. These lay counsellors are trained to detect symptoms of common mental disorders like depression and anxiety, and plan interventions for treatment. Most of the evidence for the efficacy of these programmes is limited to adults however. Older teens who are 18 and above have shown to be as responsive to lay counsellor interventions as older adults but studies in younger adolescents are forthcoming. What is clear is that lay counsellors require well-planned adequate supervision, a clear referral network for complex cases, and to have their own mental health needs assessed and supported (Hoeft et al., 2018).

Other alternatives to problem-solving therapy-based models include training community health workers and other community support people in brief interventions such as those seen in models like Screening Behaviour Intervention Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) for management of substance use disorders in some countries (Gentilello, 2014). These motivational interviewing-based interventions can be particularly helpful for youth with mild disorders and prevent deleterious consequences of self-harm and death. Involving community health workers as lay counselors provides important connection points to all youth but is particularly important for those youth in areas with low densities of health workers (Barry et al., 2013). These providers can extend the reach of mental health professionals by focusing on different elements of mental health care. They may focus on identification of youth with potential mental health concerns, for example, either by referrals from teachers, families, or community members, or by being trained to facilitate annual or semi-annual mental health screening surveys that are then directly referred to medical professionals. Employing community health workers as lay counsellors is a growing field with innovative task shifting interventions continuing to emerge.

Teachers and schools

School teachers can be trained to deliver universal programmes to promote emotional well-being. Schools have access to a large number of adolescents making them an excellent access point. Teachers and school environments can be ideal for mental health promotion, disease prevention and intervention programmes. Some countries have implemented mental health promotion programmes adapted from HIC to fit into the local cultural milieu. A systematic review of evaluation of school and community based life skills and resilience-based mental health promotion programmes for adolescents in LMIC in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Central and South America reported a positive effect on motivation, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and coping in areas of conflict (Barry et al., 2013). In India currently, multicomponent school programmes delivered by school teachers and peers that focus on prevention of substance use, bullying, depression and promotion of safe sexual behaviour are under evaluation for effectiveness (Shinde et al., 2017). The school setting has also been recently used to successfully pilot a low-intensity transdiagnostic psychological intervention for common adolescent mental health problems by lay counsellors under the PRIDE (Premium for Adolescents) programme (Michelson et al., 2011; Parikh et al., 2019). The PRIDE programme promotes a stepped care approach to psychological intervention in Indian secondary schools. Training of teachers and implementing programming in schools have the potential to increase access to care for adolescents by breaking down many of the logistic barriers adolescents face when trying to engage with the health care setting (Petersen et al., 2019).

Digital mental health services

Mobile health (mHealth) that includes using wireless digital devices for achieving health goals can be used in resource-limited settings and are seen as perfect entry points for adolescents in LMIC who have growing access to mobile phones and a strong interest in digital social engagement. In recent times, there has been a 90% penetration of the internet in LMIC and more than 50% population owns a smartphone with even higher estimates having some mobile phone access. mHealth programmes reduce the difficulty in accessibility, transportation, stigmatization, provider prejudice and issues regarding privacy and confidentiality (Feroz et al., 2019). WHO recommends the use of mobile health apps (MHApps) as there is evidence for their efficacy for management of depression, anxiety, psychosis, substance use, suicide and anxiety in HIC.

There are limitations that must be considered as these models are piloted in LMIC. There may be concerns related to privacy and confidentially especially with youth who share a mobile phone or access to the internet. There must also be culturally appropriate applications in relevant local languages. Stakeholders from a recent study in India shared that the use of MHApps for severe mental illness should also provide community-relevant tools such as access support groups, tips for caregivers, and other culturally relevant content (Sinha Deb et al., 2018). In Indonesia, internet-based behavioural activation therapy was found useful in treating adults with depression and nicotine addiction (Arjadi & Patel, 2018; Free et al., 2013). Developments are being made in adolescent-specific mobile interventions as well. A mobile phone game named ‘POD’ based on problem-solving techniques for school children with emotional and behavioural problems has been piloted in India recently (Gonsalves et al., 2019). Mobile and internet-based programmes are also being developed in LMIC for task sharing in terms of diagnosis, treatment, supervision of adherence to management and integrating services (Naslund et al., 2019).

Paediatricians and primary care physicians

Sometimes a young person needs services beyond the scope of community-based care. The next step then is to engage trained primary care physicians and paediatricians to meet adolescent mental health care needs. In LMIC with resource constraints, the integration of adolescent mental health services into existing primary care has shown promise.

Consultant paediatricians in addition to functioning as primary care physicians who provide first-line professional-level mental health care have the opportunity to be major sources of advanced child and adolescent mental health care due to their training in developmental frameworks. Paediatricians understand normal paediatric and adolescent behaviour and can recognize when deviations in normal development occur. They often have training in basic child neurology and developmental disorders as well. This makes paediatric specialists particularly excellent targets for training as systems attempt to enhance their CAMH workforce. Some paediatric medical societies in LMIC have already begun trying to bridge the gap. In India, for example, the Indian Academy of Pediatrics has hosted workshops and other trainings to enhance paediatrician comfort with mental illnesses in children and adolescents (Shastri, 2019).

The WHO mental health gap action (mhGAP) programme produced a number of materials centred around establishing a mental health system that is integrated with general medical care. The materials target non-mental health specialists in a primary care setting using a task shifting approach. Within the mhGAP framework, there is an intervention guide (mhGAP-IG) that is a comprehensive manual with educational resources that can be used by non-mental health professionals to treat mental illnesses in low-resource settings. mhGAP-IG includes child and adolescent developmental and behavioural disorders modules that follow an evidence-based algorithmic approach for diagnosis and management of mental, neurological and substance use (MNS) disorders. In 2016, WHO launched a revised version of this guide, mhGAP IG 2.0, and more than 100 countries have adopted these training modules since its original inception. WHO emphasizes the cultural and contextual adaptation of these modules to make them acceptable to communities and countries in which they are implemented.

A recent systematic analysis, the PRogramme for Improving MEntal health care (PRIME) and its sister study ‘emerging mental health systems in LMIC Study’ (EMERALD) program, found mhGAP IG materials when properly integrated into a comprehensive integrated mental health services package can improve mental health services in LMIC (Keynejad et al., 2018; Petersen et al., 2019). Researchers in Uganda assessed the effect of integrating the mhGAP IG modules for CAMH and they found a trend towards improved detection of MNS disorders (Akol et al., 2018). International Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions (IACAPAP) has free online courses on child and adolescent mental health and has developed a e-textbook and slides that when used with the mhGAP training materials results in increased knowledge among non-mental health specialists (Akol et al., 2017).

Ideally, mental health services integrated with adolescent friendly health services should comply with the WHO standards of adolescent care ensuring privacy, confidentiality and respect for the adolescent client (WHO, 2015). Screening for mental health disorders and promotion of positive health should form an essential component of routine annual health care maintenance visits. WHO Job Aid and HEEADSSSS psychosocial history taking tools can be used to provide comprehensive adolescent health care (WHO, 2010). After screening and assessment, when needed, primary care providers can use the mhGAPIG and other protocolized guidelines to assess when and what kind of treatment is needed and can also refer youth back to community-based programmes, provide medications if needed, or if complex, refer to mental health professionals.

Mental health and CAMH professionals

As evidence emerges for the stepped approach to adolescent mental health care, there is much to overcome. A Cochrane Review in 2013 revealed minimal effectiveness of non-mental health specialist workers in treatment of mental, neurological and substance use disorders in children and adolescents and recommended more robust research study designs and training programmes for the future (van Ginneken et al., 2013). It is likely that stigma against mental disorders among non-mental health specialist workers plays a role in this, as well as lack of comfort, lack of training, and potentially unclear policies and guidelines (Kohrt et al., 2018). Mental health professionals without child and adolescent training can be leveraged to treat severe cases and in some countries they are the only providers with any training in psychiatry or psychology because no CAMH professionals exist. They are available for general consultation, therapy, diagnosis, and the development of treatment plans. They also have significant experience with mental health–related stigma and could provide training to help other providers overcome stigma. Like general physicians, they may also create a treatment plan to be executed by primary care physicians who are more readily available for routine follow-up. These general psychiatrists, psychologists and mental health speciality providers such as psychiatric nurses or nurse prescribers should have opportunities to network with other mental health professionals who have specialist training in working with children and adolescents.

Programmes for primary care physicians, non-medical professionals and general mental health specialists should preferably be developed by CAMH professionals. This would strengthen task shifting in resource-limited settings (Russell & Nair, 2010a, 2010b; Spagnolo et al., 2017). In India, there is a training programme in adolescent mental health care for primary care paediatricians; in Ethiopia, there are trainings for non-physician mental health professionals and in Tunisia for general practitioners (Russel & Nair, 2010a, 2010b; Spagnolo et al., 2017; Faregh et al., 2019; Tesfaye et al., 2014). In India, CAMH professionals have developed community mental health programmes (Ramaswamy & Seshadri, 2019) and effective life skill education programmes for schools (Srikala & Kishore, 2010). These programmes should have embedded systems for evaluating their impact and effectiveness on clinical and public health care. Where available, CAMH professionals would be ideal for seeing the most complex patients who are referred by primary care physicians, mental health professionals and general psychiatrists, and paediatricians. Given the scarcity of such specialists, they likely have the greatest reach as coaches and trainers for lay and professional health workers, diagnosticians, treatment plan generators, and researchers. As technologies such as telemedicine and other remote options become more affordable, the reach of CAMH specialists will truly expand in LMIC.

Promotion of positive mental health

Prevention of adolescent mental illness is an exciting emerging area. WHO has begun to work with LMIC to create programmes for promoting positive mental health. Evidence-based work in higher income countries has shown that empathy, problem solving, positive coping, realistic future orientation and resilience can be leveraged as potential skills that will help prevent mental illness in adolescents in LMIC and all over the world. This will require government ministries to approach mental illness across sectors from education to youth development to public health to invest in cost-effective teaching methods. This area is worthy of considerable investment and if effective has the potential to play a huge role in reduction of adolescent morbidity and mortality. This would enable the young working population to enter the workforce through fewer missed productivity days and reduce mortality and morbidity due to mental disorders. Even more importantly, investment in adolescent mental health would enhance overall wellness in the largest group of adolescents and young adults our planet has ever seen for generations to come.

Conclusions

In summary

There is a large burden of mental illness in adolescents in LMIC with an equally large treatment gap.

Interventions common in HIC that rely on a high density of human resources often has limited applicability in resource poor settings.

There are many barriers to bridging the treatment gap in LMIC including a low density of professionals, stigma, adolescent specific factors and more.

The WHO advocates for an approach that emphasizes community-based solutions first with stepped care to more advanced specialist engagement.

Peer educators and lay health workers can provide trained support for youth that may otherwise be hard to reach.

Teacher implemented, school-based, and mHealth solutions are all being used as cost-effective models to gain fast and easy access to youth while overcoming many logistical barriers that adolescents face.

Medical providers without mental health specialization can provide the first level of advanced screening, diagnostics and treatment for adolescents.

Paediatricians should be a focus for enhanced training as their specialization and workforce numbers (exceeding that of CAMH specialists), equips them to be a bridge between primary care and CAMH providers.

General mental health specialist and CAMH specialists are currently quite rare, but in the stepped care model, they function well in curriculum development, training, diagnostics, and plan generation with referral back to primary and community-based care.

A 14-year-old girl belonging to a rural family in India was found to have social withdrawal, talking to self in response to an imaginary playmate, and an excessive interest in the opposite sex. Initially this was considered normative behaviour with onset of menarche. A year after the onset of her symptoms, a school teacher noted a significant deterioration in her handwriting along with poor academic performance and referred her to a tertiary mental health care facility where she was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Despite this diagnosis, her parents refused antipsychotic treatment citing the negative image a mental health diagnosis and drug treatment would place upon the family.

Box 1. The evidence gap.

In order to provide solutions to address barriers at personal, clinic, and governmental levels, the adolescent mental health data gap must also be overcome. LMIC have poor surveillance in adolescent mental illness so it is difficult to quantify the burden of illness and define targets for reduction in national health policies and programmes. Even where surveillance is done, finding validated tools in different languages and contexts using rigorous gold standards such as psychiatric interviews can be difficult. This is even more notable for mild mental illness, as cut offs scores for their identification would require large population based research studies. This problem can be compounded in communities with small populations and multiple languages. The funding and research expertise necessary to perform these studies is growing in many LMIC though many challenges remain. Some treatment interventions particularly psychosocial, and psychological behaviourally based interventions also lack an evidence base for adolescents living in LMIC. This is very important in countries, where culture, social pressures, language and other contexts require ‘evidence-based interventions’ to be studied to establish their local relevance, efficacy, and effectiveness. While global mental health interventions in LMIC are still woefully underfunded, organizations throughout Europe and Canada have begun to earmark funds to study this important area and countries have begun to create evidence-based protocols for mental disorders.

Box 2. The role of governments.

Governments and public health systems at large can mitigate some of the mental health systems barriers that adolescents face. The WHO assessment instrument for mental health systems echoes this with their six domains for mental health services; namely national policy, mental health services, integration into primary care, human resources, integration with other departments like education and promoting mental health research (Lund et al., 2010). Mental health policies should include adolescent-specific language. Namely, they should address legal barriers and enable adolescents to self-consent for treatment which can improve their access to care. Clinical guidelines, such as those found in the mhGAP IG, also serve as multi-disciplinary, cross ministerial road maps that can provide mandates for surveillance, prevention and treatment from primary care and beyond. These mandates can then be guides used to direct funding for clinical services, human resource requests, and research funding as systems grow. Recognizing the importance of CAMH, the government of India recently upgraded the specialized adolescent health care facility at the national nodal tertiary care centre (Yadav et al., 2019) and included mental health in the national adolescent health policy and programme (Satia, 2018). Governments can support medical organizations and societies to provide training manuals, medical school modules, continuing medical education, and other educational tools to educate adolescents and young adults regarding mental health disorders and emotional well-being. Governments can promote multisectoral integration by linking media, public education, health and social welfare departments to establish public campaigns and other mental health promoting activities. Policies, guidelines, mandates, and cooperative integration are critical for all innovation to reach youth in low-resource settings and would be cost-effective in improving their quality of life.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Biographies

Preeti M Galagali is a primary care adolescent health physician practicing in Bengaluru, India, since 15 years. She has developed a number of adolescent health teaching modules and has been extensively involved in training programs for pediatricians, teachers and community health workers. She has conducted many community based life skills based education and parenting programs.

Merrian J Brooks is an instructor of pediatrics and attending physician in adolescent medicine at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Her research through the Botswana UPENN Partnership involves investigating peer to peer youth lay counseling models in Botswana.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Akol A, Makumbi F, Babirye JN, Nalugya JS, Nshemereirwe S, & Engebretsen I (2018). Does mhGAP training of primary health care providers improve the identification of child- and adolescent mental, neurological or substance use disorders? Results from a randomized controlled trial in Uganda. Global Mental Health, 5, e29. 10.1017/gmh.2018.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akol A, Nalugya J, Nshemereirwe S, Babirye JN, & Engebretsen I (2017). Does child and adolescent mental health in-service training result in equivalent knowledge gain among cadres of non-specialist health workers in Uganda? A pre-test post-test study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11, 50. 10.1186/s13033-017-0158-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arjadi R, & Patel V (2018). Q&A: Scaling up delivery of mental health treatments in low and middle income countries: Interviews with Retha Arjadi and Vikram Patel. BMC Medicine, 16(1), 211. 10.1186/s12916-018-1209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry MM, Clarke AM, Jenkins R, & Patel V (2013). A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health, 13, 835. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Weiss HA, Verhey R, Simms V, Munjoma R, Rusakaniko S, Chingono A, Munetsi E, Bere T, Manda E, Abas M, & Araya R (2016). Effect of a primary care-based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of American Medical Association, 316(24), 2618–2626. 10.1001/jama.2016.19102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty M, Shaw K, Goulding L, Parke H, Eassom E, Ali F, & Thornicroft G (2017). Evidence-based guideline implementation in low and middle income countries: Lessons for mental health care. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11, 8. 10.1186/s13033-016-0115-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faregh N, Lencucha R, Ventevogel P, Dubale BW, & Kirmayer LJ (2019). Considering culture, context and community in mhGAP implementation and training: Challenges and recommendations from the field. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13, 58. 10.1186/s13033-019-0312-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feroz A, Abrejo F, Ali SA, Nuruddin R, & Saleem S (2019). Using mobile phones to improve young people’s sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review protocol to identify barriers, facilitators and reported interventions. Systematic Reviews, 8(1), 117. 10.1186/s13643-019-1033-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, Watson L, Felix L, Edwards P, Patel V, & Haines A (2013). The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: A systematic review. PLOS Medicine, 10(1), Article e1001362. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilello L (2014). Chapter four – Detection of populations at-risk or addicted: Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in clinical settings. In Madras B & Kuhar M (Eds.), The effects of drug abuse on the human nervous system (pp. 77–101). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalves PP, Hodgson ES, Kumar A, Aurora T, Chandak Y, Sharma R, Michelson D, & Patel V (2019). Design and development of the ‘POD adventures’ smartphone game: A blended problem-solving intervention for adolescent mental health in India. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 238. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, & Unützer J (2018). Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: A systematic review. The Journal of Rural Health: Official Journal of the American Rural Health Association and the National Rural Health Care Association, 34(1), 48–62. 10.1111/jrh.12229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengsiragulwit D (2015). Opportunities and obstacles in child and adolescent mental health services in low- and middle-income countries: A review of the literature. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health, 4(2), 110–122. 10.4103/2224-3151.206680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keynejad RC, Dua T, Barbui C, & Thornicroft G (2018). WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) Intervention Guide: A systematic review of evidence from low and middle-income countries. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 21(1), 30–34. 10.1136/eb-2017-102750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Jordans M, Turner EL, Sikkema KJ, Luitel NP, Rai S, Singla DR, Lamichhane J, Lund C, & Patel V (2018). Reducing stigma among healthcare providers to improve mental health services (RESHAPE): Protocol for a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial of a stigma reduction intervention for training primary healthcare workers in Nepal. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 4, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, Kakuma R, Corrigall J, Joska JA, Swartz L, & Patel V (2010). Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 71(3), 517–528. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie RK, van Lettow M, Gondwe C, Nyirongo J, Singano V, Banda V, Thaulo E, Beyene T, Agarwal M, McKenney A, Hrapcak S, Garone D, Sodhi SK, & Chan AK (2017). Greater retention in care among adolescents on antiretroviral treatment accessing ‘Teen Club’ an adolescent-centred differentiated care model compared with standard of care: A nested case-control study at a tertiary referral hospital in Malawi. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(3), e25028. 10.1002/jia2.25028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulik PK, Devarapalli S, Kallakuri S, Tewari A, Chilappagari S, Koschorke M, & Thornicroft G (2017). Evaluation of an anti-stigma campaign related to common mental disorders in rural India: A mixed methods approach. Psychological Medicine, 47(3), 565–575. 10.1017/s0033291716002804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Malik K, Krishna M, Sharma R, Mathur S, Bhat B, Parikh R, Roy K, Joshi A, Sahu R, Chilhate B, Boustani M, Cuijpers P, Chorpita B, Fairburn CG, & Patel V (2019). Development of a transdiagnostic, low-intensity, psychological intervention for common adolescent mental health problems in Indian secondary schools. Behaviour research and therapy. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J, Belfer M, Daniels A, Flisher A, Villé L, Lora A, & Saxena S (2011). Treated prevalence of and mental health services received by children and adolescents in 42 low-and-middle-income countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 52(12), 1239–1246. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni A, Weiss HA, Weobong B, McDaid D, Singla DR, Park AL, Bhat B, Katti B, McCambridge J, Murthy P, King M, Wilson GT, Kirkwood B, Fairburn CG, Velleman R, & Patel V (2017). Sustained effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Counselling for Alcohol Problems, a brief psychological treatment for harmful drinking in men, delivered by lay counsellors in primary care: 12-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. PLOS Medicine, 14(9), Article e1002386. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund JA, Shidhaye R, & Patel V (2019). Digital technology for building capacity of non-specialist health workers for task sharing and scaling up mental health care globally. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27(3), 181–192. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh R, Michelson D, Malik K, Shinde S, Weiss HA, Hoogendoorn A, Ruwaard J, Krishna M, Sharma R, Bhat B, Sahu R, Mathur S, Sudhir P, King M, Cuijpers P, Chorpita BF, Fairburn CG, & Patel V (2019). The effectiveness of a low-intensity problem-solving intervention for common adolescent mental health problems in New Delhi, India: Protocol for a school-based, individually randomized controlled trial with an embedded stepped-wedge, cluster randomized controlled recruitment trial. Trials, 20(1), 568. 10.1186/s13063-019-3573-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V (2007). Mental health in low- and middle-income countries. British Medical Bulletin, 81–82, 81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Weobong B, Weiss HA, Anand A, Bhat B, Katti B, Dimidjian S, Araya R, Hollon SD, King M, Vijayakumar L, Park AL, McDaid D, Wilson T, Velleman R, Kirkwood BR & Fairburn CG (2017). The healthy activity program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 389(10065), 176–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, van Rensburg A, Kigozi F, Semrau M, Hanlon C, Abdulmalik J, Kola L, Fekadu A, Gureje O, Gurung D, Jordans M, Mntambo N, Mugisha J, Muke S, Petrus R, Shidhaye R, Ssebunnya J, Tekola B, Upadhaya N, & Thornicroft G (2019). Scaling up integrated primary mental health in six low- and middle-income countries: Obstacles, synergies and implications for systems reform. BJPsych Open, 5(5), e69. 10.1192/bjo.2019.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy S, & Seshadri S (2019). Methodologies and skills in child and adolescent mental health, psychosocial care, and protection: A repository of training and intervention materials. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(3), 226–227. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_155_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell PS, & Nair MK (2010a). Strengthening the Paediatricians Project 1: The need, content and process of a workshop to address the Priority Mental Health Disorders of adolescence in countries with low human resource for health. Asia Pacific Family Medicine, 9(1), 4. 10.1186/1447-056X-9-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell PS, & Nair MK (2010b). Strengthening the Paediatricians Project 2: The effectiveness of a workshop to address the Priority Mental Health Disorders of adolescence in low-health related human resource countries. Asia Pacific Family Medicine, 9(1), 3. 10.1186/1447-056X-9-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satia J (2018). Challenges for adolescent health programs: What is needed? Indian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 43(Suppl. 1), S1–S5. 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_331_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shastri D (2019). Respectful adolescent care – A must know concept. Indian Pediatrics, 56(11), 909–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde S, Pereira B, Khandeparkar P, Sharma A, Patton G, Ross DA, Weiss HA, & Patel V (2017). The development and pilot testing of a multicomponent health promotion intervention (SEHER) for secondary schools in Bihar, India. Global Health Action, 10(1), 1385284. 10.1080/16549716.2017.1385284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha Deb K, Tuli A, Sood M, Chadda R, Verma R, Kumar S, Ganesh R, & Singh P (2018). Is India ready for mental health apps (MHApps)? A quantitative-qualitative exploration of caregivers’ perspective on smartphone-based solutions for managing severe mental illnesses in low resource settings. PLOS ONE, 13(9), Article e0203353. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolo J, Champagne F, Leduc N, Piat M, Melki W, Charfi F, & Laporta M (2017). Building system capacity for the integration of mental health at the level of primary care in Tunisia: A study protocol in global mental health. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 38. 10.1186/s12913-017-1992-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikala B, & Kishore KK (2010). Empowering adolescents with life skills education in schools – School mental health program: Does it work? Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 52(4), 344–349. 10.4103/0019-5545.74310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye M, Abera M, Gruber-Frank C, & Frank R (2014). The development of a model of training in child psychiatry for non-physician clinicians in Ethiopia. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 8(1), 6. 10.1186/1753-2000-8-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN Department for Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), Population Division. (2017). World population prospects 2017. https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-the-2017-revision.html [Google Scholar]

- van Ginneken N, Tharyan P, Lewin S, Rao GN, Meera SM, Pian J, Chandrashekar S, & Patel V (2013). Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low- and middle-income countries. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, CD009149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weobong B, Weiss HA, McDaid D, Singla DR, Hollon SD, Nadkarni A, Park AL, Bhat B, Katti B, Anand A, Dimidjian S, Araya R, King M, Vijayakumar L, Wilson GT, Velleman R, Kirkwood BR, Fairburn CG, & Patel V (2017). Sustained effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Healthy Activity Programme, a brief psychological treatment for depression delivered by lay counsellors in primary care: 12-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Plos Medicine, 14(9), Article e1002385. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis N, Napei T, Armstrong A, Jackson H, Apollo T, Mushavi A, Ncube G, & Cowan FM (2018). Zvandiri-Bringing a differentiated service delivery program to scale for children, adolescents, and young people in Zimbabwe. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 78(Suppl 2), S115–S123. 10.1097/qai.0000000000001737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2008). Integrating mental health into primary care: A global perspective. https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/integratingmhintoprimarycare/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2010). Adolescent job aid: A handy desk reference tool for primary level health workers. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9789241599962/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2015). Global standards for quality health care services for adolescents. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/global-standards-adolescent-care/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): Guidance to support country implementation. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/framework-accelerated-action/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). https://www.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent/indicator-explorer-new/mca/adolescent-mortality-rate—top-20-causes-(global-and-regions) [Google Scholar]

- Yadav AS, Madegowda RK, Sharma E, Jacob P, Vijaysagar KJ, Girimaji SC, Seshadri SP, & Srinath S (2019). New initiatives: A psychiatric inpatient facility for older adolescents in India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(1), 81–88. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_275_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]