Abstract

Most prior bisexual research takes a monolithic approach to racial identity, and existing racial/ethnic minority research often overlooks bisexuality. Consequently, previous studies have rarely examined the experiences and unique health needs of biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals. This exploratory qualitative study investigated the identity-related experiences of biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults within the context of health and well-being. Data were collected through 90-min semi-structured telephone interviews. Participants were recruited through online social network sites and included 24 adults between ages 18 and 59 years. We aimed to explore how identity-related experiences shape biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals’ identity development processes; how biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals negotiate their identities; how the blending of multiple identities may contribute to perceptions of inclusion, exclusion, and social connectedness; and how biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals may attribute positive and negative experiences to their identities. Interview transcripts were analyzed using an inductive thematic approach. Analysis highlighted four major themes: passing and invisible identities, not measuring up and erasing complexity, cultural binegativity/queerphobia and intersectional oppressions, and navigating beyond boundaries. Our findings imply promoting affirmative visibility and developing intentional support networks may help biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals cultivate resiliency and navigate sources of identity stress. We encourage future research to explore mental health and chronic stress among this community.

Keywords: Bisexual, Biracial, Multiracial, Intersectionality, Sexual orientation

Introduction

Although previous literature shows bisexual individuals of color often experience a sense of invisibility and marginality (Collins, 2004), most prior sexual minority research takes a monolithic approach to racial identity. Further, bisexuality is rarely examined within race and ethnicity research (Collins, 2004; Muñoz-Laboy, 2018). Thus, the identities of biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals are underrepresented, obfuscating potential health concerns. Using a gender-diverse sample of participants, this exploratory qualitative study investigated the identity-related experiences of biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults within the context of health and well-being.

Bisexual People of Color

Prior research shows bisexual people of color experience multiple layers of oppression (Harper et al., 2004). Numerous studies reveal bisexual people of color face binegativity, heterosexism, homophobia, and racism in many contexts (Balsam et al., 2013; Bowleg, 2013; Fukuyama & Ferguson, 2000; Ghabrial & Ross, 2018; Ross et al., 2010). For instance, they may encounter racial discrimination and biphobia from the LGBT + community and heterosexism from racial/ethnic communities (Balsam et al., 2013; Ochs, 1996). Thus, those who participate in the LGBT + community and their racial/ethnic community may feel like they must juggle two lives, unable to be their whole selves (Brooks et al., 2010; Rust, 1996). Bisexual people are often stereotyped as indecisive, unpredictable, promiscuous, confused, and untrustworthy, making it difficult to disclose their sexual identity (Collins, 2004; Kich, 1996; Lingel, 2009). Identity denial for bisexual people is significantly associated with depression, lower self-esteem, and decreased feelings of authenticity (Garr-Schultz & Gardner, 2019). Consequently, visibility among bisexual people, especially those of color, is an ongoing concern (Bostwick & Dodge, 2019).

There is a well-documented body of evidence noting bisexual individuals, regardless of race, experience physical and mental health disparities in comparison with lesbian, gay, and heterosexual groups (Bostwick et al., 2010; Dodge et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2015). Previous research reveals bisexual people have more mental health challenges and significantly higher rates of mental distress compared to lesbians and gay men (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2010). Compared to heterosexual people, bisexual people have more challenging life events (Dodge & Sandfort, 2007). Moreover, bisexual women have a significantly higher lifetime prevalence of rape, physical violence, and stalking by an intimate partner than both lesbians and heterosexual women (Walters et al., 2013).

For bisexual people of color, their racial identity can exacerbate these disparities (Bowleg, 2013; Collins, 2004; Meyer, 2003; Rust, 1996); still yet, bisexual people of color continue to be underrepresented in sexual minority research (Harper et al., 2004), mental health research (Ghabrial & Ross, 2018), and race and ethnicity research (Collins, 2004; Muñoz-Laboy, 2018). Further, despite biracial/multiracial people constituting one of the largest growing racial/ethnic groups in the USA (Mather et al., 2019), and despite people of color being more likely to identify as bisexual than their white counterparts (Movement Advancement Project, 2016), biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals are relatively unacknowledged in sexual minority and racial/ethnic minority research data.

Biracial/multiracial individuals have unique stressors in comparison with people of color who identify as belonging to only one racial category including differentness and dissonance between self-perception and others’ perceptions of them (Kich, 1992), racial identity mislabeling, pressure to choose a singular racial identity (Poston, 1990), cultural isolation, and increased stress from low identity integration (Cheng & Lee, 2009). Biracial/multiracial individuals also face prejudice within their different racial/ethnic communities (King, 2011). Therefore, it is inaccurate to assume research including bisexual people of color who belong to only one racial category can highlight the specific lived experiences and health needs of biracial/multiracial and bisexual people. It is necessary to account for biracial/multiracial people separately to avoid the oversimplification of their racial identity (Stanley, 2004).

Biracial/Multiracial and Bisexual Adults and Literature Gaps

A small body of literature exists on biracial/multiracial and bisexual communities. Dworkin (2002) explored the influence of bisexuality on bicultural and biracial identities, illustrating the strengths, stresses, and complexities of biracial–bisexual and bicultural–bisexual identities. In her qualitative study exploring socializing agents of identity development, King (2013) found multiracial/biracial–bisexual/pansexual adolescents often felt invisible in their multiple identities. Participants additionally noted an overarching sense of not belonging within social groups. Thompson (2012) investigated how mixed-race and bisexual individuals conceptualize their identity-based communities, finding participants often self-selected and self-created their communities with others within the same “constellation of identities.” While these three studies provide much needed representation for biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals, they have important limitations. First, they only include the perspectives of cisgender women, excluding those with other gender identities. Secondly, in Dworkin’s (2002) study, most participants were white, and the study primarily focused on how women with multiple aspects of identity (i.e., religion, age) construct their bisexual identity. Thus, biracial and bisexual identities were only addressed briefly. Further, these studies did not specifically examine identity negotiation processes or instances of oppression, which are commonly noted as salient experiences for biracial/multiracial or bisexual individuals (Harper et al., 2004; Kich, 1992; Pachankis, 2007). While King’s (2013) study explored identity development, her findings were only presented within the college context.

Both Israel (2004) and Thompson (2000) wrote autobiographical narratives highlighting their personal experiences with their biracial (in Thompson’s case, specifically Hapa) and bisexual identities. These studies present rich perspectives detailing the authors’ experiences exploring, questioning, processing, validating, and embracing their multiple identities; nonetheless, these studies only show the author’s perspective. Other authors have described the twinship between biracial/multiracial and bisexual identities via theoretical conceptualizations (Stanley, 2004) and the potential for contextualizing these identities through similar models for identity development (J. Collins, 2000; Fukuyama & Ferguson, 2000). While J. Collins (2000) adapted her findings for biracial and bisexual adults, her study only included a sample of biracial adults. Additionally, Fukuyama and Ferguson (2000) and Stanley (2004) provided implications for counseling biracial and bisexual adults; however, their research was confined to a review of relevant literature and did not include participant data.

More recently, Galupo et al. (2019) have explored the positive experiences of bisexual/plurisexual and biracial/multiracial participants through an online survey, finding most respondents had meaningful positive experiences from their identities. To date, this is the only study to examine the benefits of the intersections of these identities. Participants discussed how the interconnectedness of their identities served as a strength, made them wonderfully unique, afforded them more experiences and options, and increased their community connections. While the design of this study prevented the authors from clarifying participants’ responses, this research contributes essential progress toward understanding the experiences of biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals.

Current Study

The current study fills a void in the literature in three distinct ways. First, this study will examine biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults’ intersectional experiences with identity negotiation and oppression—two areas that have not received any research attention, to our knowledge, yet provide important connections to psychological well-being, chronic stress, and physical health (Camacho et al., 2020; Harrell, 2000; Meyer, 2007). Next, the design of this study will allow us to expand on Galupo and colleague’s findings and more thoroughly contextualize and understand participants’ positive experiences, with hopes of generating implications for developing resiliency among this group. Finally, this study addresses the gaps above by utilizing a gender-diverse sample of participants, giving voice to those who hold multiple identities outside of commonly dichotomous categories.

Given the exploratory nature of this study and the substantial lack of research on biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals, the purpose of this study is to investigate participants’ identity-related lived experiences and consider the implications of these experiences for health and well-being. The following four questions guided our research:

What experiences and factors shape biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults’ identity development?

How do biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults negotiate their identities?

How do biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults’ identities influence their perceptions of community inclusion, exclusion, and social connectedness?

What positive and negative experiences do biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults attribute to their identities?

Method

Theoretical Framework

Overview

We used an intersectionality framework to guide our analytic strategy, the development of our interview guide, and our data collection process. Collins (2015, p.2) references intersectionality as “the critical insight that race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, ability, and age operate as reciprocally constructing phenomena that in turn shape complex social inequalities.” In other words, intersectionality conceptualizes the nonadditive nature of social identities (P. Collins, 2000) and the nonadditive effects of social inequality (Choo & Ferree, 2010).

The core ideas of intersectionality emerged from the 60s and 70s from Black women, Indigenous women, and women of color within multiple freedom and liberation movements (Collins & Bilge, 2020). The noteworthy scholarship of Audre Lorde (1984) and Gloria Anzaldúa (1987) further advanced these ideas in the 80s. Further, the Combahee River Collective demonstrated the groundbreaking argument that single identity frameworks only advance partial and incomplete analyses of the social injustices faced by marginalized groups (Combahee River Collective, 1995). Thus, the complex challenges that historically marginalized groups experience cannot be solved by mono-categorical solutions (Valk, 2008) or an additive approach (Abrams et al., 2020; Bowleg, 2012).

Over the last decade, intersectionality research has expanded within the public health field (Alvidrez et al., 2021). Bowleg’s (2008, 2012, 2013) research and writings have been foundational in identifying intersectionality as a critical theoretical framework for public health. Through intersectionality, the health sciences can generate more holistic representations of marginalized experiences and the forces that create those experiences (Abrams et al., 2020). Further, intersectionality provides excellent potential for studying health disparities, health behaviors and practices, health outcomes, and identities (Choo & Ferree, 2010; Bauer, 2014). This framework has been used to explore public health considerations such as gay and bisexual Black men’s intersectional health experiences (Bowleg, 2013; Dworkin, 2015); mass shootings targeting the LGBT Latinx community (Ramirez et al., 2018); multiple minoritized identities of patients in healthcare settings (Jaiswal et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2016); self-identified health concerns of racially diverse bisexual men (Williams et al., 2020); and most recently, intersectionality has been utilized to highlight the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on those at the most marginalized demographic intersections (Bowleg, 2020).

While this work has been important, studies that cite intersectionality as a guiding framework are still lacking in research on bisexual people of color (Ghabrial & Ross, 2018; Gonzalez & Mosley, 2019). Of the few existing studies on biracial/multiracial and bisexual identities, only one identifies intersectionality as a guiding framework; however, only positive elements of intersectionality were contextualized (Galupo et al., 2019; Ghabrial, 2017). The current study will add to the growing body of work on the intersectional experiences of racially diverse bisexual groups and add a new perspective to better understand the overlapping identities of biracial/multiracial and bisexual groups.

Application Within the Current Study

Identity is an essential dimension of intersectionality’s critical inquiry and praxis (Collins & Bilge, 2020). In the current study, we used intersectionality as an analytical tool for emphasizing identity. Scholarship that utilizes intersectionality as an identity-based analytic tool commonly examines how intersecting identities create distinct social experiences for individuals and social groups (Goldberg, 2009). We used intersectionality to explore and further understand participants’ lived social experiences with multiple overlapping identities (biracial/multiracial and bisexual). Participants’ identities were understood as differently performed in varying social contexts through this intersectional lens instead of fixed. Further, power relations shape these social contexts (Collins & Bilge, 2020; Hall, 2017), meaning participants might experience privilege and oppression simultaneously (Abrams et al., 2020).

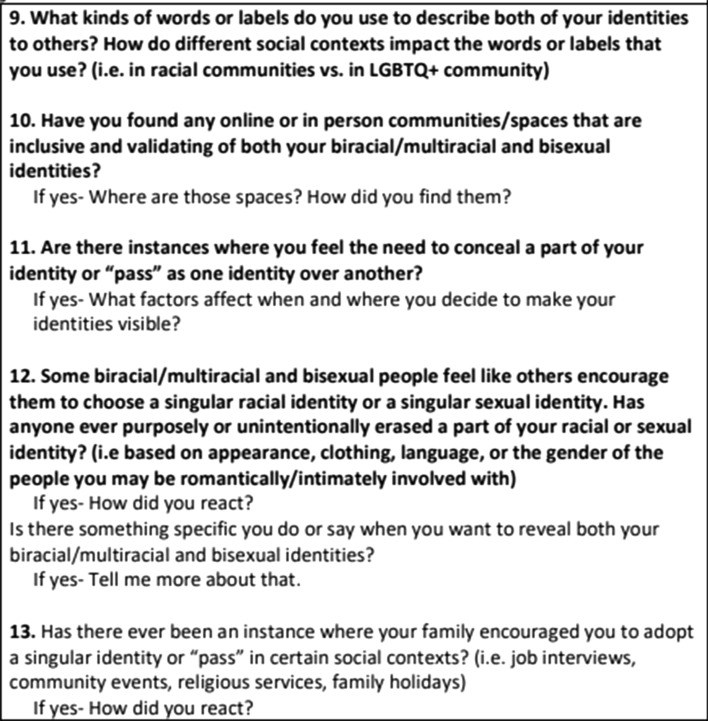

Besides using intersectionality as an analytic tool, we implemented tenants of intersectionality when designing our interview guide and collecting the data. When creating the interview guide, we were careful to ensure our questions did not imply participants should rank their identities or give salience to one above another (Bowleg, 2008). Additionally, we piloted our interview guide with three individuals from the target group of interest to help ensure potential participants would understand the questions and that the questions would evoke responses relevant to the research questions (Abrams et al., 2020).

Methodological Approach

Throughout this study, we relied on an interpretivist approach that centers the meaning-making practices of our participants. Interpretivist paradigms privilege participants’ subjective experiences during the data collection process (Thorne et al., 2004). We acknowledge the nature of human experience is constructed and contextual, allowing for shared realities (Thorne et al., 1997). Further, we acknowledge our research team is also part of this meaning-making process, as the inquirer and person of inquiry interact to influence one another inseparably (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Participants

The present study employed a qualitative interview study design. We collected data from October 2019 to December 2019 through semi-structured, in-depth phone and Zoom interviews. In addition to having phone/internet access, eligibility criteria included being 18 years of age or older, self-identifying as biracial or multiracial, self-identifying as bisexual, and residing in the USA. The final sample of participants included 24 biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults.

Participants were primarily recruited through various LGBTQ + , bisexual-specific, and biracial/multiracial groups on social media sites. We ensured we gained administrator approval before posting recruitment information in these online groups. Recruitment information was also sent to organizations, community advocacy groups, and listservs for these populations. The recruitment flyer described the study as an “interview that examines experiences with identity and wellbeing.” The flyer stated we were looking for participants who self-identified as biracial or multiracial and bisexual. Interested participants (n = 91) completed an eligibility screening questionnaire using Qualtrics, an online survey platform. We excluded those who did not self-identify as bisexual (n = 4), those who did not live in the USA (n = 1), and those who did not self-identify as biracial or multiracial (n = 11). Those who met the eligibility criteria and provided virtual consent to participate in the study (n = 75) were then contacted by the primary researcher (DW) to set an interview time and date. Participants who responded and completed the interview were compensated for their time with a $50 electronic Amazon gift card. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the authors’ institution.

Our sample was comprised of 24 adults (see Table 1 for demographics) between the ages of 18 and 59 years, with an average age of 28 (± s = 8.15). Participants included 14 cisgender women, two cisgender men, three transmen, four non-binary or genderqueer individuals, and one individual who self-identified as questioning. Half of participants (n = 12) were from the Northeast of the USA, one-third (n = 8) were from the Midwest, three were from the Southeast, and one was from the West.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (N = 24)

| Pseudonym | Self-identified race | Age | Self-identified sexual identity | Gender identity | Geographical region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kelli | Asian, White | 20 | Bisexual, Queer | Cisgender Woman | Midwest |

| Josephine | American Indian or Alaska Native, Hispanic/Latinx, White | 34 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | West |

| Jackie McArthur | Black or African-American, White | 27 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Midwest |

| AB | Black or African-American, White | 32 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Northeast |

| Dewey | Black or African-American, Hispanic/Latinx | 22 | Bisexual | Transgender Man | Midwest |

| Taja | Hispanic/Latinx, White | 32 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Midwest |

| Mimi | American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African-American, White | 59 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Northeast |

| Sarah | American Indian or Alaska Native, Native American or other Pacific Islander, White | 24 | Bisexual | Non-binary/Genderqueer | Midwest |

| Caleb | Black or African-American, Hispanic/Latinx | 29 | Bisexual | Non-binary/Genderqueer | Northeast |

| John | Hispanic/Latinx, White | 25 | Bisexual | Transgender Man | Northeast |

| Jay | Black or African-American, White | 25 | Bisexual | Cisgender Man | Midwest |

| Lee | Hispanic/Latinx, White | 22 | Bisexual | Questioning | Northeast |

| Lyssa Taro | Middle Eastern/North African, White | 29 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Midwest |

| Noémie | American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African-American | 30 | Bisexual, Queer | Non-binary/Genderqueer | Northeast |

| Jay | American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, White | 35 | Bisexual | Non-binary/Genderqueer | Northeast |

| MT | Asian, Hispanic/Latinx, White | 30 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Northeast |

| Zander | American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African-American, White | 18 | Bisexual | Transgender Man | Southeast |

| Mskty | American Indian or Alaska Native, White | 27 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Southeast |

| James | Black or African-American, Hispanic/Latinx | 27 | Bisexual | Cisgender Man | Northeast |

| Nicole | Black or African-American, White | 18 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Midwest |

| Lore | Hispanic/Latinx, White | 29 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Northeast |

| Cleopatra | Black or African-American, White | 21 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Southeast |

| Teresa | Hispanic/Latinx, White | 24 | Bisexual | Cisgender Woman | Northeast |

| Laura | Asian, White | 29 | Bisexual, Pansexual | Cisgender Woman | Northeast |

Measures and Procedure

Demographics

In the eligibility screening questionnaire, participants were asked to choose whether they identified as biracial or multiracial. Those who selected “yes,” were then directed to select all options they felt best described their racial identity: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African-American, Hispanic/Latinx, Middle Eastern/North African, Native American or other Pacific Islander, White, or not listed. Those who selected “not listed” were prompted to write in a response. We recognize racial categories are social constructs that are both designed and defined by those who have historically held influence and power (Winant, 1998). In this study, we are only analyzing racial classifications within the context of the USA. We acknowledge constructions of race vary globally.

To collect data on sexual identity, respondents were asked: “How would you describe your sexual identity? Bisexual, Gay, Heterosexual or Straight, Lesbian, Pansexual, Queer, Not Listed (please specify).” Those who selected “pansexual,” “queer,” or “not listed” were directed to a follow-up question, which asked them whether they would also describe their sexual identity as “bisexual.” Only participants who selected “yes” were included in this study.

We collected data on gender identity by asking participants: “How do you identify in terms of gender? Cisgender Woman, Cisgender Man, Gender Non-Conforming, Non-binary/Genderqueer, Transgender Female, Transgender Male, Not Listed (please specify).” Those who selected “not listed” were asked to write in a response.

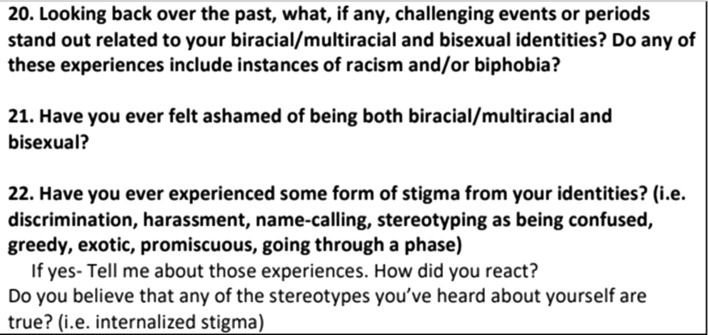

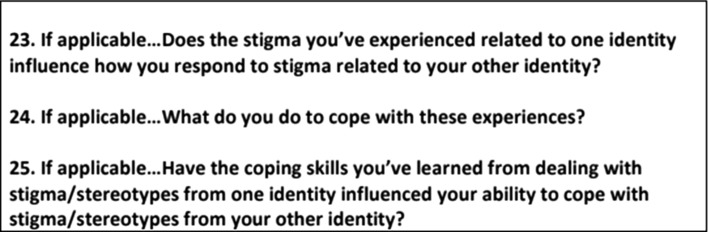

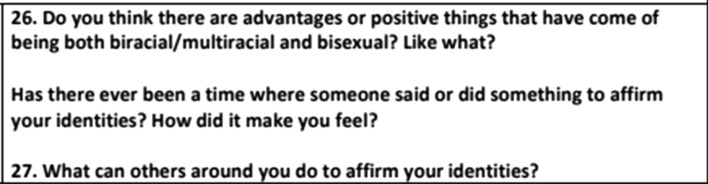

Interviews

Interviews lasted approximately 50–90 min with the average interview lasting 60 min. The interview guide explored identity development, identity negotiation, perceptions of inclusion, exclusion, and social connectedness within communities, and identity-related positive (i.e., benefits, strengths) and negative experiences (i.e., racism, stigma, stereotypes). This article reports relevant themes related to identity negotiation and positive and negative experiences (see Appendix for interview guide). Participants chose pseudonyms and were interviewed by four study investigators (DW, EB, BT, and BD) who had prior training and experiences conducting qualitative research. The interviewers recorded notes during the interview process to reference when coding and analyzing the data. Interviews were audio-recorded and machine transcribed through Temi, an automated speech recognition engine (Rev, 2020). Three graduate-level trained research assistants and the first author checked the transcripts against the recordings for accuracy and made corrections and edits where necessary.

Coding

Three research team members (DW, EB, and BT) developed the codebook inductively within Dedoose, a qualitative data organization and management software (SocioCultural Research Consultants, 2018). Each of the researchers first familiarized themselves with the data at least once before beginning the coding process (Ando et al., 2014; Braun & Clarke, 2006). The initial codebook was based on emergent codes and subcodes we developed and applied to meaningful chunks within the data (i.e., codable moments or codable units) via independent, open coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Ando et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2019).

We carefully documented and maintained a decision trail during this process, noting the origin and operalization of each code and subcode, code progressions, and code revisions (when codes were merged, reassessed, or renamed) (Guest et al., 2006; Nowell et al., 2017; Mihas & Odum Institute, 2019). This process helped ensure consistency and accuracy across code applications. When new codes or subcodes emerged or changes were made to the codes, the coders revisited previous transcripts accounting for this new approach and documented this within our auditable notations (Jain & Ogden, 1999; Nowell et al., 2017). The codebook was complete once most codable units or moments fit within the coding guide. We based the final version of the codebook on twelve interview transcripts.

Peer debriefing also helped us engage more deeply with the data and establish our decision trail (Nowell et al., 2017). The coding team met multiple times during codebook development to discuss emerging impressions of the data and to assess consistency and reliability in coding. When discrepancies existed in code utilization, we discussed these differences until we reached an agreement reflective of the data (Roberts et al., 2019). We used Cohen’s kappa (McHugh, 2012) to measure inter-rater reliability and found agreement was consistently above 0.81.

Data Analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was utilized to analyze the data. This form of analysis was selected for the present study as it provides a rich and detailed yet complex account of the data. We followed the six-step process for inductive thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). We sorted codes into potential themes and aggregated relevant coded data extracts within the initially identified themes. Then, we examined our codes and considered how they might combine to form overarching themes. After this process, we refined our set of potential themes and examined patterns between codes and relationships between different levels of themes. Lastly, we defined and named our themes and subthemes.

The researchers reflected on their biases throughout this process and recorded how their assumptions and lived experiences might impact data analysis and interpretation. Reflexivity, a guiding principle in feminist research, helped us be mindful of our presence throughout the research process. We consciously considered how we positioned ourselves and others in representations of our research. Four members of the authorship team have extensive experience conducting research related to the intersections of sexual identity and race/ethnicity, and five members of the team have been engaged in years of advocacy for bisexual people of color. Multiple of the authors also identify as members of the LGBTQ + community and/or people from communities of color.

Results

Four main themes (see Table 2) emerged from the interview data related to identity negotiation and negative and positive experiences: (1) passing and invisible identities, (2) not measuring up and erasing complexity, (3) cultural binegativity/queerphobia and intersectional oppressions, and (4) navigating beyond boundaries.

Table 2.

Themes and corresponding interview questions

| Theme | Corresponding question |

|---|---|

| 1) "I navigate the liminal space”: Passing and invisible identities | What factors affect when and where you decide to make your identities visible? |

| 2) “I’m both not enough and too much”: Not measuring up and erasing complexity | Some biracial/multiracial and bisexual people feel like others encourage them to choose a singular racial identity or a singular sexual identity. Has anyone ever purposely or unintentionally erased a part of your racial or sexual identity? |

| 3) "I've experienced a multitude of adversity": Cultural binegativity/ queerphobia and intersectional oppressions | Looking back over the past, what if any, challenging events or periods stand out related to your biracial/multiracial and bisexual identities? Do any of these experiences included instances of racism and/or biphobia? |

| 4) “My identities help me transcend boundaries”: Beyond boundaries | Do you think there are advantages or positive things that have come of being both biracial/multiracial and bisexual? |

Theme 1. “I Navigate the Liminal Space”: Passing and Invisible Identities

Many participants felt they existed in a liminal space between two worlds due to their identities’ perceived invisibility or ambiguity. One participant expressed this “in-betweenness” as “floating between things and never really feeling like you’re latching down anywhere in particular” (Jay, 35, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, White, Non-binary/Genderqueer). This suspension between identities was often understood as a middle space or “gray area” that transcended normative categorizations of race and sexual identity. For instance, Jay (25, Black or African-American, White, Cisgender Man) discussed that the intersections of his identities left him “[unable to] fit into a category.” Because of the liminal nature of their identities, participants possessed a plurality of selves that could be deployed or differently interpreted within a multitude of social interactions. Thus, to navigate the liminal space, many participants engaged in forms of passing—a mechanism that allows individuals to be viewed in an identity group different from their own. While passing was viewed as a necessary component of safety and protection, respondents also revealed how passing caused them discontent and discomfort.

When asked, “what factors affect when and where you decide to make your identities visible?” three distinct forms of passing emerged in participants’ responses. First, multiple respondents described passing both intentionally and actively through identity concealment. Identity concealment is a stigma management strategy in which individuals decide when, how, and where to disclose different identities in various situations, contexts, and places (Maliepaard, 2017). Participants described deploying more socially accepted identities or avoiding disclosing their identities to increase material opportunities and belonging. “Most of the time I just say I’m gay since there’s a lot of stigma around bisexual, and I sort of realized at a young age that being more ‘white’ would generally be beneficial to me in life” (John, 26, Hispanic/Latinx and White, Transgender Male). Accordingly, participants who intentionally and actively passed were able to move out of a liminal state into accepted professional and social positions. For instance, Noémie (30, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African-American, Non-binary/Genderqueer) mentioned feeling the need to pass at the intersections of their race and sexual identity nearly every day to navigate the world, “especially if there’s money involved, in a professional setting where I need to earn money. Usually in those settings, you’re penalized for being outside the norm.” While intentional and active passing may appear to be a privilege and a “choice,” biracial/multiracial and bisexual people may lack true agency in passing as many routinely feel compelled to do so. Respondents often contextualized passing as a necessary component of survival, safety, and discrimination avoidance. Two participants explained their safety considerations when deciding whether they would pass:

I kind of feel like I have to assess a situation [for violence], and if the conversation is turning political or about sexuality and race, I really have to consider, do I want to just let them talk and say their piece or do I feel like this is a safe enough space where I can talk about my story? (MT, 30, Asian, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Cisgender Woman)

Passing is a safety mechanism [for me]. Passing as whatever you need to. Being able to jam yourself into one box or another, even if it's just temporary is what keeps you from getting beaten up. (Jay, 35, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, White, Non-binary/Genderqueer)

The second way in which participants engaged in passing was through processes that were intentional but passive. Others misrecognized participants in ways that were inconsistent with their self-identification. Despite this, respondents allowed others to mislabel them or make assumptions about their identities without correcting them. This was often to avoid questions concerning their identities or out of resignation others would always attempt to define them. Lee accepted others’ labels of their identities for most of their life:

Most of my life has just been concealing and letting people decide for me. It's like a guessing game. It's like you never know how they're going to treat you and you never know what you're gonna get from walking into a new space. That is exactly my experience. Like my whole life, just waiting for people, waiting to hear in a conversation how they see me. Just waiting for information to be revealed about who they think I am because I didn't have the choice really. (22, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Questioning)

Lee felt stripped of the power to assert their identities because they readily anticipated others would project identities onto them. Respectively, Lee came to expect this labeling and passed according to how others defined them. This passing instance reveals the depths of discomfort and stress many biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals feel from consistently being mislabeled or having their identities discredited.

Finally, interviewees struggled to balance the identity invisibility they presumed others noticed and their authentic identity. Consequently, participants also passed unintentionally through others’ unvoiced assumptions of their identities. Biracial/multiracial and bisexual people are largely hyperaware of how they believe they are perceived in various spaces. Skin tone, physical features, and the gender of one’s partner(s) heavily influence how individuals are “read” by others. Participants were conscious of how their appearance and relationship status impacted their outward presentation. As a white-passing individual in a heterosexual appearing relationship, Sarah lamented that the intersectional invisibility of their identities causes them to pass, even when they do not wish to.

I feel like a lot of the struggles or the hard times are when I'm trying to come to terms with how I present myself and how I deal with the world because most of the time, the world is gonna treat me like a straight, white person. (24, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native American or other Pacific Islander, White, Non-binary/Genderqueer)

While some may view passing as an advantage or benefit, it is predicated on invisibility. When biracial/multiracial and bisexual people unintentionally pass from the invisibility of their identities, they feel unseen, unheard, and unimportant:

I have passing privilege…I mean I can’t choose to not be bisexual and Syrian or biracial, but technically no one has to know. But I like when people know, that feels better. I feel uncomfortable that I can get away with that. It makes me feel less valid a lot of the times. (Lyssa Taro, 29, Middle Eastern/North African, White, Cisgender Woman)

Lyssa Taro and Sarah contest the ideology that passing is inherently privileged or advantageous. For both respondents, the level of invisibility they faced from passing served as a source of discontentment and invalidation.

Theme 2. “I’m Both Not Enough and Too Much”: Not Measuring Up and Erasing Complexity

When asking participants about their experiences with identity erasure, several recounted feeling insufficient or overly complex in their identities when they experienced erasure. Some believed their identities were disregarded as a result of being “not enough.” These experiences left multiple participants internalizing feelings of insufficiency as they associated measuring up in their identities with the noticeability of cultural identifiers and their relationship status or relationship history. For others, their identities were conversely perceived as “too much.” Consequently, their identities were simplified or diminished when others deemed them overly complicated or excessively confusing.

The invisibility of participants’ identities and challenges with identity erasure left many participants feeling they were not enough to consider themselves bisexual people of color. At times, others determined this sense of not measuring up. Lyssa Taro revealed people are often skeptical of her biracial and bisexual identities due to her appearance and relationship history. The authenticity and believability of her identities are based on conditional and stereotypical expectations she fails to meet.

I feel like [with] my bisexuality and me having Middle Eastern heritage, people have this idea of how I should look and act, but since I don’t really meet it, I’m often told to take a backseat. They're like, “you’re half Middle Eastern, why aren't you darker? Why don’t you wear a hijab? You’ve mainly dated men? Well how many women have you slept with?” I think it just tells me, you’re just another straight white girl. You basically are, even though you’re not. (29, Middle Eastern/North African, White, Cisgender Woman).

The invisibility of bisexual identities often leaves individuals in heterosexual appearing relationships to have their queerness questioned or to be presumed as straight. As Lyssa Taro expressed, her bisexuality only appears credible to others if her queerness is visible in her relationship status or apparent in her sexual history. This is further complicated by the intersections of her race and sexual identity, as she is commonly faced with proving both of her identities. Lyssa Taro’s identities are disqualified from measuring up to others’ preconceived ideas of what it means to be of Middle Eastern descent and bisexual as she lacks the necessary relationship history and cultural identifiers. The concept of a “deficiency” in measuring up asserts the underlying notion there is a uniform way or a correct way for someone to exist in their identities. In other instances, the perception of not being enough was based on internalized feelings of imposter syndrome. Kelli stated:

I feel like a total outsider. I have hella imposter syndrome. I guess I don’t really count...my boyfriend is a cis man, and I’m very light so I don’t really call myself a person of color, so I have a hard time taking up space because I don’t want to claim something I’m not, especially not from someone else. But then, where do I ever take up space? Where is my time…where is my place to do that? I’m trying to fully accept myself and not rely on other people to seek out that constant validation, but I feel like other all the time. (Kelli, 20, Asian, White, Cisgender Woman)

While Kelli shares her desire not to claim too much space from others with “undisputable” identities, she simultaneously feels she lacks belonging and access to spaces where she is allowed the freedom to discuss her experiences openly. Beneath her comments lies the conviction there are social criteria she must meet to be fully considered a bisexual person of color; hence, she silences herself to avoid claiming what she perceives as a false narrative. Similarly, MT was cautious of discussing her identities with others in her identity communities, fearing she does not have the right to empathize with the experiences of people who have experienced more oppression than her.

It gets challenging being multiracial and bisexual. I guess monoracial and full people of color… I feel like I don't have a right to encroach on their conversations because I'm not fully a person of color. And so, when those conversations are happening that I’m part of, I kind of feel like I have to stay silent…And I guess with queer friends because I'm in a heterosexual relationship because I've never like, one of my best friends is a lesbian and she's very much had the unfortunately typical experience where her parents rejected her and all this horrible stuff that she's had to go through. And I didn't have to go through that. And I know that's because of mostly outwardly having relationships with men. And so, it's like I've been walking this line between like privilege and oppression, like my whole life with the overlap of these two major identities. (30, Asian, Hispanic/Latinx, and White, Cisgender Woman)

In other instances, participants recounted experiences where their identities were deemed too complicated. Accordingly, some felt that others reduced the multiplicity of their identities for their comfort. Lee provided an example of this:

Sometimes when I'm around a lot of my friends, my biracialness [and bisexuality] definitely gets washed away. People say things that refer to me and my group of friends all being white, and I don't even know why they would say anything like that. But they say things that refer to me being a part of that. It's a very conscious choice…And if some of my friends know I have a boyfriend, they don’t give me the opportunity to express I might be interested in girls as well. They just stick to the box of what they know and don’t give me room to expand my identities in any other way…They're choosing to be like, “okay, we’re going to make her one of us because it's easier.” (22, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Questioning)

Biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals are commonly categorized simply for others’ convenience. To Lee’s social circle, it was easier to simplify their identities than to acknowledge their fullness. Forcing Lee into conforming to the majority’s identity released Lee’s friends from the tension of Lee’s complexity. In Noémie’s experience, people diminish their identities out of discomfort with ambiguity. Seeing and acknowledging biracial/multiracial and bisexual people as full beings rather than fragmented pieces of a whole person causes dissonance for those who rely on categorization for understanding:

There’s been an attempt to remove my sexuality and remove the complexity of racial identity, any sort of culture and practice that’s not European. People don't do great at handling complexity when it comes to race and sexuality and gender. They want an absolute. Honestly, I can't see it, you know, because I'm, I've been living in this body…I guess based on that, I think maybe people are trying to relate to me and they feel frustrated when they can't, but for me, that's an everyday thing, so I can live with that discomfort personally, but other people can’t. (Noémie, 30, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African-American, Non-binary/Genderqueer)

Both Lee and Noémie highlight the impact of identity colonization. Erasing their complexity and replacing it with a more palatable variation of their identities implicitly reveals the superiority complex driving these behaviors. Lore described another time when societal expectations suggested her identities were “too much:”

We're in such a dualistic culture. People either want me to be one or the other. I think when I was dating, when I was with a woman, a lot of my straight friends assumed that I was a lesbian. People just lump me in and forget about the bisexuality. Scratch that whole part and scratch me being biracial. People want to see me either as Latinx or white, and I'm not. I am, I'm more than either…I'm both, you know, simultaneously. It's hard for folks to wrap their head around that sometimes. (29, Hispanic/Latinx and White, Cisgender Woman)

Both/and is an uncomfortable concept for people to process when they are customary to either/or. Lore’s narrative highlights how biracial/multiracial and bisexual people are frequently pressured to select sides rather than representing themselves as a whole.

Theme 3. “I’ve Experienced a Multitude of Adversity”: Cultural Binegativity/Queerphobia and Intersectional Oppressions

When asked, “looking back over the past, what, if any, challenging events or periods stand out related to your biracial/multiracial and bisexual identities?” participants recounted experiencing instances of binegativity and queerphobia within their racial and ethnic communities and intersectional oppressions. For bisexual people of color, cultural norms and expectations can pose significant challenges in gaining sexual identity acceptance and affirmation within their racial/cultural group membership, thus inhibiting the expression of bisexual identities. Consequently, some participants described struggles in balancing loyalty to their family and heritage and being “out” as a bisexual person. “I've had to distance myself from the Dominican culture I grew up in because of my queer identity. I don't know how much of myself I can express or if I want to be around these people because I'm afraid I might get some backlash” (John, 26, Hispanic/Latinx and White, Transgender Male). Jay explained another example of this mentioning:

There really isn't a place in Japanese culture for queer people. It's probably better in the last few years, but you know, the expression that my dad and my grandmother and like lots of other Japanese people I know use is “the nail that sticks up, gets pounded down.” Your job as an Asian person is to not draw attention to yourself at all costs. And by being something other than the norm, you are making yourself the center of attention, which is considered very gauche and rude and inappropriate. So, it was very difficult for me to reconcile… And it turned out that my family has a lot of issues acknowledging the fact that bisexual people exist and are real. They just don't understand it. And especially when I was in relationships with men, they were like, “why does it matter? Why do you have to keep bringing this up?” And they had a very difficult time taking me seriously. At several points in high school, I was literally homeless because my mom threw me out of the house because of my sexuality. And even now I think it's a struggle. (Jay, 35, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, White, Non-binary/Genderqueer)

Jay described the guidelines for permissible behavior and prioritized identity traits within their culture. As bisexuality was misaligned with traditional Japanese cultural values and expectations, Jay’s family refused to acknowledge it as a legitimate or acceptable sexual identity.

Multiple stereotypes persist surrounding bisexuality in addition to perceptions of bisexuality as “not being real.” In particular, bisexual men are frequently on the receiving end of gendered binegativity that stereotypes them as “weak or too submissive.” This narrative is further complicated for biracial and bisexual men due to heteronormative cultural expectations surrounding masculinity. For instance, James stated:

Black people are some of the most homophobic people that I could deal with. I do think it's a culture thing. And I would say that Black people, they have this thing, or I should say we have this thing where men just can’t be anything other than straight. If they're not straight, then it's a problem. It's a bad thing. They're not a man anymore, and they don’t belong anymore. It's just the end of the world. (James, 27, Hispanic/Latinx and Black or African-American, Cisgender Man)

James perceives the Black community as having rigidity in gender expectations; these normative expectations for performances of masculinity solely leave space for heterosexuality. Deviation from these norms can result in biracial and bisexual men being emasculated and disregarded from their racial and ethnic group membership.

In other instances, participants mentioned feeling forced to choose between their sexual identity or racial identity due to cultural queerphobia. For example, Noémie’s Afro-Caribbean neighborhood intentionally held cultural church events during Pride weekend to deter community members from attending.

For me to get into the city to get to Pride, I had to pass through several cultural religious processions. And I knew they were holding them that weekend specifically because it was Pride weekend cause it’s not a regular thing. I would love to feel like part of this community, but this opposition to queerness made me uncomfortable. A lot of people had to choose between identities that day. (30, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African-American, Non-binary/Genderqueer)

By holding their event the same weekend as Pride, Noémie viewed their cultural community’s actions as rejecting their intersectional identities.

Several respondents also described how they experienced multiple layers of oppression from their intersectional identities. Laura explained that the aggressive and violent comments people have made to her could not be isolated to a singular piece of her identity, saying:

I’ve definitely experienced misogyny, homophobia, biphobia, and racism. Men have said negative Asian stereotypes to me, like when I’m with a girlfriend…It’s impossible to parse out what negative experience would be in the biracial bucket and what would be in the bisexual bucket if that makes sense. (29, Asian and White, Cisgender Woman)

Similarly, Caleb (29, Black or African-American and Hispanic/Latinx, Non-binary/Genderqueer) mentioned experiencing “transphobia, biphobia, queerphobia, and racism,” acknowledging that these intersectional forms of oppression made them more vulnerable to hardships and stress and have decreased economic security.

I really do see like parallels in terms of the oppressive nature of what's laid upon all my identities. I’m navigating being in a world that feels like really hard, like inherently hard and stressful. I’ve experienced what it’s like to be Black, bi, and trans, and like visibly gender variant…it’s really impacted my net worth, financial stability, how I’m treated at work...I know that if I were white, you know, I would be having a very different experience, right? I would have more access to spaces and resources. (Caleb, 29, Black or African-American and Hispanic/Latinx, Non-binary/Genderqueer)

Other participants described being exoticized and fetishized for their identities. This manifested in offensive sexual advances, assumptions of promiscuity, and racially objectifying commentary surrounding their bodies. Josephine highlighted how misogyny, racism, and biphobia converged when she was exoticized and fetishized as an object of fantasy:

There’s this perception from heterosexual men, especially in college because they were predominantly either white spaces or spaces that didn't have a lot of people of color, definitely like the feeling of being like exoticized as a bisexual woman of color and that I'm identifying as bisexual as some form of like you're always into threesomes right now. So, also this like sexualizing promiscuous component to it…that's very objectifying, it's hurtful. And having that tied to like your body, so thinking about your hips or your breasts in a way that's different than like white women. I think that was hard. I mean there definitely were comments about me being half-Latina and bisexual and all the stereotypes that come with that for sexuality and sexual justification. So, I do think that that was hard. (34, American Indian or Alaska Native, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Cisgender Woman)

Theme 4. “My Identities Help Me Transcend Boundaries”: Navigating Beyond Boundaries

Despite respondents’ identity-related challenges and oppressive experiences, participants also highlighted how their identities helped them navigate beyond boundaries. When participants were asked whether there were any advantages or positive things that have come of being both biracial/multiracial and bisexual, a few participants mentioned they “were not sure” or could not think of any positive experiences associated with the intersections of their identities. However, most participants revealed they had positive experiences from existing in a space beyond boundaries in three ways: their identities liberated them from the limits of boxes, increased their self-awareness, and provided them with a richer range of experiences and perspectives.

When explaining the positive elements of their identities, many participants articulated their identities allowed them to subvert categorization and restrictive societal standards. As Taja noted, “I come off as the wild card, you know? I really like that” (32, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Cisgender Woman). Respondents suggested they received a sense of freeness from falling outside of boxes and resisting the notion they must choose a singular identity. Defying boundaries of traditional categories, labels, and norms was viewed as something worthy of appreciation:

I've never quite felt like I fit into one category cause that's kind of been my whole existence. It's been this like, I don't fit into your box. I feel like I've come to terms with that, and I think that that's something that I find really cool about myself. I don't fit into your little boxes. I like things that are unconventional and, if I could choose, I wouldn't want to fit in a little box. (Kelli, 20, Asian, White, Cisgender Woman)

I also see the joy in all of them [my identities], you know? Existing outside of the bounds of colonialism or like white supremacy and all those things. (Caleb, 29, Black or African-American, Hispanic/Latinx, Non-binary/Genderqueer)

In rejecting others’ attempts to box them in, participants claimed ownership over their identities, noting they possessed the power to speak for themselves and define themselves. “It has made me very independent, has made me value my own authority over other people's authority” (Lore, 29, Hispanic/Latinx, White, cisgender women).

Respondents described increased self-awareness as a second advantage to existing beyond boundaries. The complex nature of their identities encouraged them to process and reflect on them regularly. Participants often spent substantial amounts of time learning, talking, and thinking about their identities and their place in the world, which in turn promoted personal growth:

I think it's been a very elevated learning experience in ways because at a fairly young age…I was able to do a lot of reading on sexuality, on gender, race politics in general. So I do feel in a way that belonging to those communities and having those identities, I do think it was just a way to elevate my understanding of things other people may not have been able to conceptualize as easy at that age of maybe like 16 or 17. I do feel like it kind of helped broaden things in general for me that at this point in my life, I would say I have a fairly well-rounded understanding of myself and most of those topics in general. (Teresa, 24, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Cisgender Woman)

Those who are minoritized by others often spend more time and conscious effort considering their identities than those in majority groups. Participants highlighted that their increased self-awareness stemmed from living in a world where they had to think about their identities. Biracial/multiracial and bisexual people are largely cognizant that their identities impact how others perceive them and engage with them:

I think that I'm very aware of thinking through who I am as a person because of my experiences. Maybe in a way that people who don't have these identities don't necessarily think through. I have definitely thought a lot about my race, a lot about my sexual orientation in ways that I think that people that might be the majority don't think about those things. So, I think I'm very self-aware if that's what the strength of both of those identities is (Josephine, 34, American Indian or Alaska Native, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Cisgender Woman).

Finally, respondents noted their multiplicity of identities provided them with a broader range of rich experiences and openness to more worldviews. For Caleb and Nicole, this meant increased access to communities they could make connections and share different perspectives with:

I get access to communities that feel inherently generative or mostly reciprocal. (Caleb, 29, Black or African-American, Hispanic/Latinx, Non-binary/Genderqueer)

I feel like [my identities] kind of made me more open minded, especially when it comes to political issues. I can kind of see both sides even though I don't agree with some of the people… I feel like I can relate to more people just because I identify with multiple communities. (Nicole, 18, Black or African-American, White, Cisgender Woman)

John described gaining “a wider worldview and understanding of things than a lot of people who might be coming from just like one kind of identity” (25, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Transgender Man). Similarly, Lee sees their identities as an advantage because they feel they have the opportunity to experience more out of life. “I'm very grateful for my experience because I'm glad that I get to see all these nuanced things, and I get to experience identity in such a vast way. I'm glad that I get to feel all these things” (22, Hispanic/Latinx, White, Questioning).

Discussion

Biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals are underrepresented within sexual minority and racial/ethnic minority research. The present study explored the identity-related experiences of 24 biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults with diverse gender identities while considering health and well-being implications. Findings revealed four main themes: participants negotiated the invisibility and liminality of their identities through passing; participants faced challenges with being perceived as not enough to authentically claim their biracial/multiracial and bisexual identities or too much to be their whole selves; participants experienced intersectional forms of oppression and binegativity from their racial/ethnic groups; and participants perceived that their identities positively impacted their lives through liberation from strict categories, growth in self-awareness, and richer experiences.

There were many notable findings within this study. The identity negotiation experiences of respondents were contextually shifting and fluid given the liminality of their identities. Their acute awareness of the social and financial disadvantage they could face at the intersections of their identities deterred many of them from revealing their biracial/multiracial and bisexual identities in certain social contexts (e.g., professional settings, settings where the risk of violence was perceived as high). For some participants, this included strategically deploying elements of their identity they presumed were more socially desirable and “safe.” The ability of respondents to move between different aspects of their identities might appear to be an exhibition of agency (Adams, 2018); however, these decisions surrounding identity disclosure and passing revealed more constraint than agentic power. Participants described passing out of necessity, not out of desire.

Passing is often generalized as a “privileged” behavior (Silvermint, 2018), yet our findings provide an alternative argument to this essentialism. While respondents gained elements of security from passing, participants’ narratives around identity concealment underscore the depths of structural oppression. Racism, binegativity, and heterosexism create a toxic, dangerous environment for biracial/multiracial and bisexual people where they avoid identity disclosure to mitigate threats of microaggressions, violence, discrimination in employment, and to simply survive daily. Thus, participants’ identity negotiation behaviors ultimately stem from social injustice. Furthermore, though stigma concealment is utilized as a protective behavior (Pachankis, 2007), it may have adverse psychological health outcomes for those who conceal out of concern of discrimination and victimization (Camacho et al., 2020; Feinstein et al., 2020). While our findings illuminate biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals’ attempts to avoid negative treatment, these identity negotiation behaviors might be detrimental to mental health and psychological well-being.

Participants’ narratives also revealed how being mislabeled and passing unintentionally caused them stress. In particular, white-passing participants who were perceived as heterosexual recounted several instances of feeling invisible, discredited, and unimportant, suggesting the perceived social benefits of passing may not outweigh the perceived identity stress and discomfort. Previous research has discussed the adverse health effects of passing based on racial identity or sexual identity (Frost & Bastone, 2008; Harris, 2018; Ragins et al., 2007); however, this study is one of the first to highlight the distress that may occur from passing at the intersections of one's racial identity and sexual identity.

We discovered that feelings of identity insufficiency among participants stemmed from pressure to meet conditional and often stereotypical expectations surrounding race and sexual identity. Commentary around “being too light” and “dating too many men,” shaped much of the backlash respondents received on the authenticity of their identities. Because sexual identity is an unseen category (Ghabrial, 2019), bisexuality is only rendered visible through disclosure statements (Hayfield et al., 2013). Participants described how others expected them to “look” or “act” bisexual, yet we ask, how one can embody bisexuality as an unmistakable identity? Calling to mind the provocative question posed by Whitney (2001), “if I choose to identify myself as bisexual, is it necessary for me to somehow prove this through my daily performance of identity? How then do I perform the identity of two [or more] sexualities simultaneously?” Recent news stories have additionally highlighted the identity disbelief and denial biracial and multiracial people often received based on their hair texture, physical characteristics, skin color, and language (Donnella, 2017; Venkatraman & Lockhart, 2020). Participants’ stories show how social norms at the intersections of these identities often require biracial/multiracial and bisexual people to prove their identities, prompting them to internalize feelings of identity insufficiency. Interestingly, we discovered cisgender women who were white-passing and in long-term heterosexual appearing relationships noted the most challenges in claiming authority in their identities or feeling their identities were “legitimate.” These findings are similar to previous studies revealing cisgender bisexual women dating cisgender men may have internalized fear of not being queer enough (Bradford, 2004; Ghabrial, 2019; Rust, 2000), and biracial and multiracial people who pass for white commonly experience racial identity invalidation (i.e., “you’re not a real person of color”) (Franco et al., 2016). Undoubtedly, living in a society where bisexual erasure and monoracism do not exist would significantly reduce participants’ internal struggles with the believability of their identities.

Respondents were often not presented with the option of identifying with more than one race and being attracted to individuals of more than one gender identity. This highlights the repressive nature behind dominant ideologies that privilege binary thinking. According to Kich (1996), the dominant majority is intolerant of ambiguity due to fear, anxiety, or an inability to understand multiple sides of ambivalence; subsequently, many participants found their identities colonized and problematized through heteronormativity and racial erasure.

We found participants experienced binegativity and queerphobia within their racial/ethnic communities, often leaving them with challenging decisions concerning being “out” as bisexual and participating in the LGBTQ + community or choosing loyalty to their family and racial/ethnic communities’ cultural values. The loss of family and community social support and belonging was a salient factor participants considered when navigating their bisexuality, leading some respondents to feel forced to choose either their racial identity or their sexual identity. While binegativity is pervasive across multiple races and ethnic groups, research suggests racial/ethnic minorities might have less favorable attitudes toward bisexual people than their white counterparts (Dodge et al., 2016; Friedman et al., 2014). Dual or multiple minority biracial/multiracial and bisexual people may have exacerbated experiences with cultural queerphobia given the multiple racial/ethnic minority communities to which they belong.

In line with extant literature on LGB people of color (Chmielewski, 2017; Firestein, 2007; Fukuyama & Ferguson, 2000; Watson et al., 2021), participants described how interlocking systems of binegativity, racism, misogyny, and transphobia made them vulnerable to verbal harassment, stereotypes, discrimination, fetishization, exoticization, and stress. Scholars have well documented that systems of oppression impede well-being for bisexual people of color (Meyer, 2007; Mosley et al., 2019) and increase chronic stress and chronic illness among racial and ethnic minorities (American Psychological Association, 2012). Notably, the majority of participants who discussed experiences with fetishization and exoticization were racially ambiguous cisgender women. These findings can be explained through overlaps between historical connotations of mixed-race and light-skinned women as desirable or sexually intriguing (Nakashima, 1992; Root, 1990), the hypersexualization of bisexual women from heterosexual men (DeCapua, 2017), and the consistent societal monitoring of women’s sexual behavior as a tool of control and objectification (Lerum & Dworkin, 2009).

Finally, several participants also noted positive feelings and experiences related to their multiple identities, contrasting most research that only discusses the mental stress caused by multiple minority identities (Fukuyama & Ferguson, 2000; Ghabrial & Ross, 2018; Harper et al., 2004; Meyer, 1995, 2003). Our study elaborates on Galupo et al.’s (2019) findings, as qualitative interviews allowed us to gather additional context and clarification for participants’ perceptions of positives related to their identities. Though not all interviewees expressed advantages from their identities, most positively viewed their identities as a means to transcend boundaries. They utilized the liminality of their identities as a strength to directly trouble and question the rigidity of identity norms. Thus, biracial/multiracial and bisexual people may counteract their identity stress through self-acceptance, demonstrating their resiliency and the benefits of being somewhat free of dominant norms.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study presents novel findings on the lived experiences of gender-diverse biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults. Participants provided detailed and rich responses to questions due to the qualitative, interview-based nature of the study, contributing to a more in-depth understanding of biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals’ experiences and concerns. However, this study is not without limitations. Firstly, our findings cannot be assumed to represent all biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults. Further, given the dispersion of participants across varying geographical areas, we could not consider the possible influence of specific geographical and sociopolitical contexts on identity-related experiences.

Secondly, most of our participants were between 18 and 30 years of age. A more age-diverse sample would provide greater insight into how aging influences biracial/multiracial and bisexual people’s identity-related experiences. We encourage future research that explores the identity-related experiences of aging biracial/multiracial and bisexual people, as research suggests older bisexual adults face unique challenges and disparities (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Muraco, 2010). Furthermore, while some participants discussed gendered experiences with oppression, we did not specifically ask how participants’ gender identity intersected with their racial identity and sexual identity. Including questions related to gender identity could have helped further contextualize the complexities of multiple identities. Additional research on the intersections of gender identities, biracial/multiracial identities, and bisexual identities is warranted, especially among transgender and gender-expansive individuals. Future research should additionally consider how invisibility in gender identity might converge with invisibility within biracial/multiracial and bisexual identities.

Conclusion and Implications

Biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals are underrepresented in both research and social contexts. The present study is one of few to present narratives of a gender-diverse sample of biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults within the context of health and well-being. Biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals have unique experiences with invisibility, which are often compounded by the intersections of their identities. While identity invisibility is used as a protective factor in avoiding discrimination and identity questioning, it also creates discomfort and distress from feelings of invalidation. Participants struggled with feeling insufficient and overly complex in their identities due to their relationship status and history, skin tone, physical appearance, and others’ discomfort with ambiguity. Respondents also noted multiple instances of intersectional oppressions along with binegativity within their racial and ethnic communities. Nevertheless, participants still highlighted how their identities afforded them opportunities to defy categories, intensify their self-awareness, and expand their abundance of experiences.

We hope our findings will inform public health professionals and those who serve individuals from multiple minoritized communities. Since participants identified distinct challenges with intersectional invisibility, mislabeling, stereotyping, and social erasure, we urge public health professionals and scholars to be critically conscious of these factors when designing research questions, implementing interventions, or developing community services and resources directed toward biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults.

Our findings also imply biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults have a great need for affirmative visibility, identity acknowledgment, and identity celebration. We encourage the development of more community-level resources to promote positive social visibility among biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults, which might cultivate more feelings of identity affirmation and validation. Further, developing intentional spaces or support networks where biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals can connect with one another or other individuals at the intersections of multiple identities and cultures might create more opportunities for resiliency and mitigate feelings of identity stress.

Participants’ experiences with oppression were not singular (e.g., the presumption that oppressive experiences are separate entities, and one aspect of oppression alone can explain experiences of disadvantage) or additive (e.g., the presumption that experiences of oppression can be “ranked”) (Bowleg, 2012; Collins & Bilge, 2020). Thus, our findings support the urgent need for applying a multidimensional, systems approach to address the interlocking forms of oppression (P. Collins, 2000) faced by biracial/multiracial and bisexual communities at the macrolevel. Further, racial and ethnic minority communities must address their cultural binegativity and queerphobia. The initiation of community dialogues or the use of community mediation might serve as valuable tools for coalescing understanding and allyship between biracial/multiracial and bisexual individuals and their racial/ethnic minority communities (Bowleg, 2013).

Finally, given the impact of identity concealment, erasure, and oppression on mental health and the documented elevated rates of depression and anxiety among bisexual groups (Ross et al., 2018), our findings warrant further research that directly investigates mental well-being and chronic stress among biracial/multiracial and bisexual adults.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Marisa Franco, Ph.D., and Brian Feinstein, Ph.D., for their mentorship and insight on this study.

Appendix

Interview Guide

Identity Negotiation Questions

Negative Experiences Questions

Positive Experiences Questions

Authors’ Contributions

This study was conceptualized by DW, BD, and EB. Material preparation and data collection were performed by DW, EB, BT, and BD. Interviews were transcribed by YRRG, BT, and SK. Analysis was performed by DW. The first draft of the manuscript was written by DW and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Indiana University-Bloomington (Ethics approval number: 1905212965).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to Publish

Participants signed an informed consent form regarding publishing their data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abrams J, Tabaac A, Jung S, Else-Quest N. Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;258:113–138. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Q. (2018). “It goes both ways”: Negotiating passing, identities of liminality, and everything in-between. Maryland Shared Open Access Repository. https://mdsoar.org/handle/11603/7742.

- Alvidrez J, Greenwood GL, Johnson TL, Parker KL. Intersectionality in public health research: A view from the National Institutes of Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2021;111:95–97. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2012). Fact sheet: Health disparities and stress. https://www.apa.org/topics/racism-bias-discrimination/health-disparities-stress

- Ando H, Cousins R, Young C. Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: Development and refinement of a codebook. Comprehensive Psychology. 2014;3:03P. doi: 10.2466/03.CP.3.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa G. Borderlands/la frontera: The new mestiza. Spinsters/Aunt Lute Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Beadnell B, Molina Y. The Daily heterosexist experiences questionnaire: Measuring minority stress among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2013;46(1):3–25. doi: 10.1177/0748175612449743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;110:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(3):468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick, W. B., & Dodge, B. (2019). Introduction to the special section on bisexual health: Can you see us now?. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bowleg L. When Black+ lesbian+ woman≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59(5):312–325. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. “Once you’ve blended the cake, you can’t take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality. Sex Roles. 2013;68(11–12):754–767. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0152-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. We’re not all in this together: On COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequality [Editorial] American Journal of Public Health. 2020;110(7):917. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. The bisexual experience: Living in a dichotomous culture. Journal of Bisexuality. 2004;4(1–2):7–23. doi: 10.1300/J159v04n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]