Abstract

Providing effective contraception for nonhuman primates (NHP) is challenging. Deslorelin acetate is a commercially available gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist that may provide a relatively noninvasive, long-lasting, and potentially reversible alternative to standard NHP contraception methods. This study evaluated the duration of suppression of progesterone and estradiol in 6 adult female rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) that received a single subcutaneous 4.7 mg deslorelin implant. We hypothesized that deslorelin would suppress production of these hormones for 6 mo with a corresponding cessation of menses. Prior to implantation, blood was collected over 1 mo for baseline hormone analyses. Macaques were sedated at the onset of the next menstrual cycle and a 4.7 mg deslorelin implant was placed in the interscapular region. Blood was collected over the subsequent month at the same intervals used for the baseline collection schedule, and then every 7 d thereafter. Results showed that estradiol and progesterone transiently increased 1 to 3 d after implantation, then fell to basal levels within 6 d of implantation. The duration of hormone suppression (progesterone < 0.5 ng/mL) varied among animals. Two macaques returned to cyclicity by 96 d and 113 d after implantation, while hormones remained suppressed in the other 4 macaques at 6 mo after implantation. Cessation of menses correlated with hormone suppression except in 1 animal that continued to have sporadic vaginal bleeding despite progesterone remaining below 0.5 ng/mL. This study indicates that deslorelin is a noninvasive and long-lasting contraceptive method in female rhesus macaques. However, individual variation should be considered when determining reimplantation intervals.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: CNPRC, California National Primate Research Center; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone

Introduction

Providing effective contraception for nonhuman primates (NHP) can be challenging, especially in NHP research breeding facilities in which colony size must wax and wane to meet ongoing research demands. Currently, common NHP contraceptive methods include pharmaceutical agents, surgical interventions, and pairing restrictions.37 Due to its efficacy and relatively infrequent dosing schedule, the synthetic progestogen medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) is one of the most heavily used medical contraceptives for NHPs in zoos and research institutions. However, MPA has been anecdotally associated with uterine irregularities, metrorrhagia, menorrhagia, and breakthrough pregnancy. Surgical methods such as tubal ligation, ovariectomy, vasectomy, and castration are inherently invasive and may irreversibly preclude an animal’s suitability for use in future research projects. Although simple and noninvasive, restricting the housing of intact females with intact males limits potential pairing options in a species for which social housing is the gold standard of animal welfare. Deslorelin acetate is a long-acting subcutaneous implant that may offer a reversible, minimally invasive alternative to current contraceptive methods.

Deslorelin is a synthetic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist that acts by suppressing pituitary production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), thereby indirectly suppressing estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone production from the gonads19. As an agonist, deslorelin initially increases the production of these hormones and GnRH receptors.19 Despite the increase in the number of GnRH receptors, they eventually become saturated; hormonal feedback then leads to downregulation of gonadotropin release and suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.19

Deslorelin acetate (Suprelorin F, Virbac, Fort Worth, TX) is marketed in the United States as a slow-release subcutaneous implant containing 4.7 mg of deslorelin. This implant can be administered in a manner similar to placing a companion animal microchip.32 This implant has been proven safe and efficacious for the management of adrenal disease in ferrets33,34 and has been successfully used off-label as a contraceptive in other species.1,6-9,13,14,16,17,20-22,25,27,31 In Australia and Europe, deslorelin is available as 4.7 mg and 9.4 mg implants and is labeled to provide contraception that lasts for 6 mo and 12 mo, respectively, in dogs.11

According to the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), deslorelin has been used for contraception in multiple species of prosimians, new world monkeys, old world monkeys, and apes.37 However, only a few studies have been published on deslorelin use in NHPs4,23,26,28, and to our knowledge, no published research has established the duration of efficacy in rhesus macaques. A 4.7 mg deslorelin implant did not suppress testosterone and spermatogenesis in male ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta).4 Similarly, in the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), a 2.35 mg dose of deslorelin did not suppress ovarian cyclicity and ovulation in females.28 Deslorelin has been reported to transiently decrease testosterone levels and aggression in male lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus)26 and olive baboons (Papio anubis).23 Another GnRH agonist, buserelin, suppressed hormone production and cyclicity in female stump-tailed macaques (Macaca arctoides) for at least 90 d when formulated as a 2.6 mg sustained-release subcutaneous implant.12

In this study, we evaluated the duration of efficacy of deslorelin in adult female rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). We hypothesized that a single 4.7 mg implant would suppress the production of estrogen and progesterone for at least 6 mo, with a corresponding cessation of detectable menses.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Six adult female rhesus macaques of similar age and weight (age [mean ± SD], 12.6 ± 1.1 y; weight, 10.3 ± 1.0 kg) were used in this study (Table 1). Criteria for enrollment in the study included nonpregnant adult females over 5 y old (sexually mature) with a body condition score of at least 2.5 out of 5 and a history of consistent menstrual cycles. Prior to beginning the study, macaques received a physical exam that included body condition scoring, digital rectal palpation, a focused ultrasound exam of the reproductive organs, and a CBC and serum biochemistry panel to ensure systemic health. Based on this initial exam and historic ultrasound evaluations, 3 of the 6 macaques were diagnosed with uterine fibroids. One of these macaques had also previously been diagnosed with an ovarian cyst via ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. All macaques were multiparous with the number of live births ranging from 2 to 6. Macaques were free of simian retrovirus type D, simian immunodeficiency virus, and simian T-lymphotropic leukemia virus. Preventative care consisted of physical exams at least annually and semiannual TB testing. All macaques were born at the CNPRC and had been vaccinated against measles and tetanus after 6 mo of age.

Table 1.

Demographics of study macaques at the time of enrollment

| Animal | Age (y) | Weight (kg) | Body condition score (1–5) | Housing condition | Mean cycle length (d)* | Uterine irregularities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 12.6 | 9.4 | 3.5 | Paired | 30.3 ± 1.2 | Fibroid, ovarian cyst |

| M2 | 10.6 | 10.1 | 4 | Paired | 27 ± 1 | Fibroid |

| M3 | 12.6 | 8.9 | 3.5 | Unpaired | 26.3 ± 2.3 | Fibroid |

| M4 | 13.5 | 11.5 | 4 | Unpaired | 29 ± 2 | None |

| M5 | 13.3 | 10.5 | 3.5 | Paired | 30.3 ± 1.5 | None |

| M6 | 13.3 | 11.4 | 4 | Paired | 28 ± 2 | None |

Mean cycle length determined by averaging 3 representative cycles occurring within the 4 mo prior to enrollment in the study, illustrated as average cycle length ± 1 SD.

Macaques were housed indoors in standard caging under a 12:12-h light:dark cycle. Rooms were maintained at constant temperature and humidity (23° ± 3 °C and 30% to 70%, respectively). During the study, animals were paired with another female or housed singly with visual and auditory contact with conspecifics. The diet consisted of a commercial chow (LabDiet Monkey Diet 5047, Purina Mills International, St. Louis, MO) fed twice daily (5 biscuits at each feeding) along with fresh produce offered twice weekly and unrestricted access to potable water obtained from the UC Davis campus domestic water system. In the month prior to study initiation, chow rations were decreased from 7 to 5 biscuits at both AM and PM feedings for all indoor-housed females to mitigate obesity in the colony. The current study was approved by the University of California, Davis IACUC and performed in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and Regulations,2,3 the Guide for the Care and Use for Laboratory Animals,18 and Public Health Service policy at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC), which maintains full AAALAC accreditation and USDA registration.

Deslorelin product.

This study used 4.7 mg deslorelin implants (Suprelorin F, Virbac, Fort Worth, TX). This drug is formulated as a solid cylinder measuring 2.3 mm × 12.5 mm, weighing 50 mg, and comes preloaded in an implanting needle. The implant contains 4.7 mg deslorelin acetate in an inert, biocompatible matrix and thus does not require removal. The implants were stored between 2 °C and 8 °C according to package instructions until use.32

Detection of menses.

Per standard operating procedures, husbandry staff observed animals daily for signs of menses. If blood was noted on the genitals or in/under the cage without evident trauma, the female was recorded as in menses in her electronic record.

Sample collection and storage.

Throughout the study, venipuncture was performed in the morning between 0800 and 0900 by trained personnel using an awake cage-side technique. Briefly, each macaque was positioned in her home cage using the squeeze-back mechanism and encouraged to present her left arm for cephalic vein access. Approximately 1.5 mL of blood was collected at each timepoint, after which macaques received a treat. Blood samples were centrifuged within 15 min of collection at 3000 x g for 10 min. Serum was then aliquoted into 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tubes that were stored at -80 °C until shipped to the Oregon National Primate Research Center Endocrine Technologies Core for analyses.

Study design.

For this study, the first day of observed menses was considered day 1 of the ovarian (menses) cycle. After study enrollment, blood was collected from the cephalic vein on the second day of each animal’s cycle as well as on days 4, 7, 12, 14, 21, and 24. On the first day of the next cycle, each female was sedated with 10 mg/kg ketamine intramuscularly and approximately 1.5 mL of blood was collected via femoral venipuncture. Each macaque received an ultrasound exam, was implanted with deslorelin as described below, and returned to the home cage to recover from sedation. Blood was collected throughout the following month as illustrated in Figure 1. In months 2 to 6 after implantation, blood collection frequency was reduced to every 7 d.

Figure 1.

Timeline of blood collection and deslorelin implantation. Numbers correspond to days of the menstrual cycle (day 1 = first day of observed menstruation) in each month. Red circles indicate blood collection. * M3 only, † M1, M2, M5, and M6 only

Deslorelin implantation.

Although the exact date of deslorelin implantation varied based on each individual’s menstrual cycle, all macaques received implants within a 3-wk time frame. Under sedation, the interscapular area was clipped and cleaned with alcohol gauze. Per manufacturer instructions,32 the applicator needle containing the deslorelin implant was attached to an actuator syringe via a Luer-lock mechanism. The needle was fully inserted into the prepared skin and the plunger on the actuator syringe was depressed, displacing the implant into the subcutaneous space. The needle was then removed, and pressure was applied to the insertion area for approximately 30 s.

Ultrasound exams.

Focused reproductive ultrasound exams were performed on each macaque prior to the start of the study to identify any uterine or ovarian abnormalities. Subsequent exams and uterine measurements were performed on the day of implantation and at 3 and 6 mo after implantation. Under ketamine sedation, macaques were placed in a supine position and their caudal abdomens were shaved prior to application of ultrasound gel. A Philips CX50 ultrasound system with a C8-5 MHz transducer was used (Philips; Amsterdam, Netherlands). The uterus was visualized in the midsagittal and midtransverse planes for measurement of uterine body length, width, and thickness. Uterine volume was estimated based on the calculation for ellipsoids:15

Serum hormone analysis.

Serum samples were analyzed via automatic immunoassay for progesterone and estradiol using a Roche Cobas e411 analyzer validated for use in NHPs (Roche; Indianapolis, IN). Lower detection limits for estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) were 5 pg/mL and 0.05 ng/mL, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

The statistical analyses for progesterone suppression and uterine volume were conducted in JMP Pro 16.1.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A one-sided matched pairs t test (progesterone) and Tukey-Kramer posthoc test (uterine volume) were used to test the null hypothesis that the pre- and post-treatment values were not different. α was set to 0.05. A correlation analysis of uterine volume and progesterone levels was performed using the Pearson product-moment test with two baseline outlier progesterone levels removed. Descriptive statistics are expressed as mean with SEM. Data were not transformed for analysis or presentation.

Results

Deslorelin suppressed estradiol and progesterone for at least 3 mo.

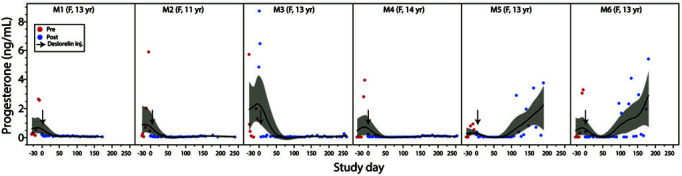

In the month before implantation, estradiol and progesterone levels fluctuated widely (Figure 2), consistent with progression through the follicular and luteal phases of the ovarian cycle. On day 1 after implantation, a transient surge in estradiol and/or progesterone was observed, the magnitude of which varied between animals. However, in all animals, estradiol and progesterone concentrations returned to basal levels by day 6 after implantation (Figures 2 and 3). Macaques were considered to be hormonally suppressed as long as progesterone remained below 0.5 ng/mL. A significant (P = 0.02) decrease in progesterone with an estimated reduction of 0.725 ng/mL (95% CI: 0.043 to 1.406) was present during the 6 mo after implantation. The earliest return to cyclicity (progesterone > 0.5 ng/mL) occurred at 96 d after implantation in M6, while 4 of 6 macaques had not returned to cyclicity by 6 mo after implantation (Table 2). Using standard survival analysis, the estimated probability of failing progesterone suppression is 17% at 84 d and increases to 33% by 102 d.

Figure 2.

Hormonal profiles before and after implantation in 2 representative macaques, M4 (top) and M6 (bottom). M6 demonstrated the earliest return to cyclicity at 96 d after implantation while M4 remained suppressed at 6 mo after implantation. M5 showed a similar hormone profile to M6, returning to cyclicity 113 d after implantation. M1, M2, and M3 remained suppressed at 6 mo, similar to M4.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal changes of serum progesterone. Serum progesterone concentration (ng/mL) throughout the study shows acute suppression within 6 d after treatment, lasting at least 3 mo (M5 and M6) and to over 6 mo (M1 to M4). The smoother line shown is the spline (using δ of 0.05). Confidence of fit is shown using the bootstrap confidence region (gray area).

Table 2.

Duration of hormonal suppression and cessation of menses

| Animal | Duration of hormonal suppression (d)* | Duration of menses cessation (d) |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | ≥180 | ≥180 |

| M2 | ≥180 | ≥180 |

| M3 | ≥180 | ≥180 |

| M4 | ≥180 | ≥180 |

| M5 | 113 | 119 |

| M6 | 96 | 105 |

Duration of hormonal suppression defined as number of days after implantation prior to first progesterone concentration above 0.5 ng/mL.

Menses cessation correlated with hormone suppression.

After implantation, macaques continued to show menses for 1 to 6 d, consistent with their previous cycles. Four animals (M1, M2, M3, M4) exhibited a transient cessation of menses for 1 to 11 d, followed by 2 to 5 d of vaginal bleeding. M4 bled for 2 additional days later in the month. M1 continued to have sporadic vaginal bleeding throughout the month and for the remainder of the study despite a hormonal profile consistent with suppression. In the 2 macaques that returned to cyclicity (M5 and M6), resumption of menses reliably occurred 11 to 12 d after progesterone levels exceeded 0.5 ng/mL. Therefore, cessation of menses correlated with progesterone suppression in this study.

Uterine size correlated with hormonal activity.

Average uterine volumes and ultrasound photos on the day of implantation and at 3 and 6 mo after implantation are shown in Figures 4 and 5. Uterine volume was significantly lower at 3 mo (P < 0.0001) and 6 mo (P < 0.0002) after implantation. Macaques that had returned to cyclicity by 6 mo after implantation (M5 and M6) had uterine volumes comparable to baseline, despite being imaged at different ovarian cycle phases. In contrast, uterine size remained decreased at 6 mo after implantation in macaques that remained hormonally suppressed (M1 to M4) (Figures 4 and 5). Thus, in this study, uterine size correlated strongly with progesterone levels (Figure 6; r = 0.73, Pearson product-moment test, 95% CI: 0.36 to 0.90). The uterine fibroids previously diagnosed in M1, M2, and M3 became less distinct with poorly defined borders in follow-up ultrasounds in which uterine size was significantly decreased, while the ovarian cyst in M1 remained readily identifiable.

Figure 4.

Individual trends in mean uterine volume. Uterine volume decreased by 3 mo after implantation in all macaques. By 6 mo after implantation, uterine volume in M5 and M6 had returned to baseline while volume remained decreased in M1 to M4, correlating with their hormonal profiles.

Figure 5.

Ultrasound images of 2 representative macaques, M4 (top) and M6 (bottom), before implantation and at 3 mo and 6 mo after implantation. M1, M2, and M3 showed a similar progression of uterine size to M4 while M5 was similar to M6.

Figure 6.

Uterine size correlated strongly with progesterone levels. Pearson r = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.36-0.90. Shaded area represents density plot with 95% coverage.

Discussion

Population management is a critical aspect of maintaining NHP breeding colonies. Depending on current and anticipated needs of the research community, suspension of breeding may be necessary to accommodate reductions in demand, budget, or housing availability. An ideal method of contraception would be safe, noninvasive, long-lasting, and reversible. In this study, deslorelin successfully suppressed cyclicity of progesterone and estradiol in female rhesus macaques for at least 3 mo and up to over 6 mo. This suppression correlated with the cessation of menses and a decrease in uterine size, and the return of normal cyclicity in M5 and M6 suggests reversibility of deslorelin’s effects.

As seasonal breeders, progesterone and estradiol levels in outdoor-housed rhesus macaques vary widely depending on the time of year.36 This seasonality is less rigid in indoor-housed macaques, which can produce infants year-round.5 However, macaques that show seasonality with anovulatory cycles in the nonbreeding season still exhibit menstruation.35 In this study, macaques were implanted in December, at the tail-end of the breeding season. Observation of menses cessation in coordination with reduced hormone levels provided a secondary indicator that the animal was truly hormonally suppressed rather than simply anovulatory. In the year before implantation, study animals cycled every month with very few exceptions: M1 did not menstruate in July, M4 did not in February, and M6 did not in May, July, or August. However, M6 only has 1- to 2-d menstrual cycles so she perhaps did cycle in 1 or more of these months without being noted by husbandry staff. Thus, cessation of menses for multiple consecutive months would be unusual in these macaques, even during the nonbreeding season. We can therefore conclude with a high degree of confidence that the hormone suppression observed in these animals was due to deslorelin.

The blood collection schedule used in this study was based on the normal macaque ovarian cycle (Figure 7), which begins at the onset of menstruation. Similar to humans, macaques are reported to exhibit a sharp midcycle preovulatory estradiol peak on day 12, followed by a rise in progesterone, which remains elevated throughout most of the luteal phase.38 To capture a representative picture of each animal’s normal hormone cycle prior to implantation, blood was collected on days 2, 4, 7, 12, 14, 21, and 24. The final blood collection time point, day 24, was determined based on the shortest average cycle length of the 6 study animals. M3 had the shortest average cycle length at 26 d, with 2 recent cycles of 25 d. To allow measurement of hormone levels in the late luteal phase of all macaques before M3 proceeded to the next cycle, blood was collected from all macaques on day 24.

Figure 7.

Normal ovarian hormone cycle of a rhesus macaque (adapted using preimplantation data from this study). Note the sharp peak in estradiol on day 12, followed by a sustained rise in progesterone during the luteal phase.

Due to preimplantation variability, we did not include a composite graph of all 6 hormone profiles. Estradiol did not always peak on day 12, and in 1 animal (M5), a defined peak could not be identified. In M5, progesterone did not appear to rise above 1 ng/mL even before implantation and estradiol did not rise above 50 pg/mL. This variability may be due to our institution’s method of menses detection, which was used to time the blood collections in this study. Our noninvasive method of detecting menses in indoor-housed macaques is via visual observation of blood on the vulva and/or in the cage pan. However, this detection method depends on the skill and experience of the animal husbandry staff, the cooperation of the animal to present her rump for visualization, and the volume of discharge produced on a given day. The low pre-implantation hormone levels seen in M5 may have been due to either failure to capture the estradiol and progesterone peaks due to inaccurate blood collection timing or an anovulatory cycle.

In this study, we defined hormonal suppression as serum progesterone concentrations below 0.5 ng/mL, consistent with follicular phase levels and anovulation.29 Because progesterone is elevated throughout most of the 14 to 17 d luteal phase,29 the weekly blood sampling in months 2 to 6 of this study allowed us to capture significant elevations, indicating a return to cyclicity. Estradiol levels were not used to determine hormonal suppression due to the very brief duration that this hormone remains elevated during the preovulatory peak (Figure 7).

The findings in M1 were inconsistent with the other macaques in this study. Estradiol levels were higher in M1 than in the other macaques both before and after implantation, although the absence of an estradiol peak and progesterone failing to rise above 0.5 ng/mL indicate that M1 was suppressed for 6 mo after implantation. M1 also continued to have sporadic noncyclic vaginal bleeding throughout the study. Although she was pair-housed, her companion was pregnant for most of the study, with a conception date 7 d after M1 was implanted. The subsequent vaginal bleeding reports were therefore not likely to be from the companion. The reason for this irregularity in M1 is unclear. However, vaginal bleeding despite hormonal suppression may represent anovulatory cycles, which have been described in macaques with low progesterone levels, the absence of estradiol peaks, and inconsistent menstruation.35 Alternatively, the high estradiol levels and sporadic vaginal bleeding may be related to M1’s persistent ovarian cyst. A unilateral ovariectomy with histopathology may allow better characterization of influence of this reproductive abnormality on M1’s hormone profile.

In this study, deslorelin induced at least 6 mo of hormonal suppression in 4 out of 6 females. At the time of this publication, M1 to M4 remained suppressed even 8 mo after implantation. The variation in the duration of effect did not appear to correlate with age, weight, or pairing status. Three of the 4 long-term suppressed macaques had reproductive abnormalities (uterine fibroids in M1, M2, M3 and an ovarian cyst in M1), while both macaques with short-term suppression were reproductively normal. The sample size was not sufficient to determine if the relationship between duration of suppression and the presence or absence of reproductive abnormalities is significant. Possible reasons for the early return to cyclicity observed in M5 and M6 may include partial implant removal from the injection site. Although pressure was held after implantation to avoid this, both M5 and M6 were paired with another female macaque, and therefore the implant could have been manipulated or removed during normal affiliative grooming behavior after recovery from sedation. Although the implant is formulated as a solid cylinder, palpation is difficult even immediately after injection and the implant becomes more porous over time as the deslorelin diffuses out. Thus, trying to determine whether the implant was still in place was not feasible after M5 and M6 returned to cyclicity. However, individual variation in the duration of efficacy has been reported in other deslorelin studies in multiple species.19 Thus, animals should be monitored for the first 6 mo after initial implantation to determine how frequently reimplantation is necessary if long-term hormone suppression is desired.

With an increasing number of research studies focusing on geriatric macaques, successful management becomes necessary for diseases that accompany aging, including endometriosis and uterine fibroids. In NHPs, endometriosis has historically been treated either surgically with ovariectomy or ovariohysterectomy or medically with progestin therapy.24 Surgical intervention is inherently invasive, permanent, and, in many cases, does not successfully stop the production of hormones due to adhesions that retain and obscure remnant ovarian tissue.10 Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) is used both as a contraceptive and a treatment for endometriosis in NHPs.23,37 However, multiple adverse effects have been reported after chronic treatment in humans and NHPs, including bone density loss, decreased insulin sensitivity, and impaired glucoregulatory function.10 In addition, at this institution, DMPA has been associated with endometrial hyperplasia and menorrhagia in both rhesus macaques and titi monkeys after cessation of therapy. At the CNPRC, deslorelin is now routinely prescribed for female macaques with clinical evidence of endometriosis such as dysmenorrhea, peri-uterine cysts identified via ultrasonography, and/or significant palpable uterine adhesions. Deslorelin is also temporarily or indefinitely administered to geriatric and nongeriatric female macaques with prolonged or heavy menstruation with anemia secondary to uterine fibroids. At the time of publication, we have successfully managed reproductive disease in over 40 macaques by using implanted deslorelin.

Weight gain has been reported after ovariectomy-induced hormone suppression in rhesus macaques30 and has been associated with synthetic progestogen therapy.37 Three of 6 macaques in this study exhibited mild weight loss during the 6 mo after implantation. However, due to a colony-wide decrease in chow rations for females at our institution in the month before implantation, we cannot draw accurate conclusions as to the effects of deslorelin on body weight in this study. The potential long-term effects of deslorelin on weight gain, fertility, bone density, and glucoregulatory function have not been established in NHPs and may warrant further investigation.

Future studies can extend the current study by using a larger sample size with a placebo arm, comparing the duration of suppression after implantation at different times of the year, comparing efficacy between macaques with and without uterine and/or ovarian abnormalities, and performing breeding trials to assess return to fertility after implantation. Additional information about duration of efficacy could be determined by a pharmacokinetic study, including the validation of a deslorelin assay for NHPs.

This study introduces deslorelin as a potential clinical and population management tool that can be applied to NHPs at the individual and colony levels. While deslorelin has been used as a contraceptive for years in the zoo and wildlife setting, our study highlights its use in NHP research breeding colonies. At the CNPRC, deslorelin has been used as a contraceptive in multiple female rhesus macaques; reimplantation can often be coordinated with scheduled exams to avoid any momentary pain or distress associated with the injection. In addition, as mentioned above, we have implanted over 40 female rhesus macaques with deslorelin as clinical treatment for hormonally responsive diseases such as endometriosis and menorrhagia. We also used deslorelin in a male rhesus macaque with a chronic, nonhealing sperm granuloma to inhibit semen production while allowing him to remain with his long-term female companion. In addition, we expanded the use of deslorelin as a contraceptive into our titi monkey colony, in which the use of DMPA resulted in many breakthrough pregnancies. At the time of publication, over 20 titi monkeys have been implanted. Thus, deslorelin has many varied potential applications in the management of NHP colonies.

The purpose of this study was to determine the duration of hormone suppression in female rhesus macaques given a 4.7 mg deslorelin implant. Despite the individual variability, deslorelin appears to provide a minimally invasive and long-lasting alternative to other methods of contraception for NHPs.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by grants from the Office of the Director of National Institutes of Health (P51 OD011107) and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant number UL1 TR001860. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors would like to thank the CNPRC technical crew for their experience and expertise, as well as David Erikson at the Oregon National Primate Research Center Endocrine Technologies Core.

References

- 1.Ackermann CL, Volpato R, Destro FC, Trevisol E, Sousa NR, Guaitolini CR, Derussi AA, Rascado TS, Lopes MD. 2012. Ovarian activity reversibility after the use of deslorelin acetate as a short-term contraceptive in domestic queens. Theriogenology 78:817–822. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Animal Welfare Act as Amended. 2013. 7 USC §2131–2159. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Animal Welfare Regulations. 2013. 9 CFR § 3.129.

- 4.Annais C, Oriol TP, Maria SA, Laura M, Dolores CM, Cati G, Miguel C, Manel LB. 2018. Effect of deslorelin implants on the testicular function in male ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta). JZAR 6:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck RT, Lubach GR, Coe CL. 2020. Feasibility of successfully breeding rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) to obtain healthy infants year-round. Am J Primatol 82:e23085. 10.1002/ajp.23085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertschinger HJ, Jago M, Nöthling JO, Human A. 2006. Repeated use of the GnRH analogue deslorelin to down-regulate reproduction in male cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). Theriogenology 66:1762–1767. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson DA, Gese EM. 2009. Influence of exogenous gonadotropin-releasing hormone on seasonal reproductive behavior of the coyote (Canis latrans). Theriogenology 72:773–783. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cope HR, Peck S, Hobbs R, Keeley T, Izzard S, Yeen-Yap W, White PJ, Hogg CJ, Herbert CA. 2019. Contraceptive efficacy and dose-response effects of the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist deslorelin in Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii). Reprod Fertil Dev 31:1473–1485. 10.1071/RD18407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowan ML, Martin GB, Monks DJ, Johnston SD, Doneley RJ, Blackberry MA. 2014. Inhibition of the reproductive system by deslorelin in male and female pigeons (Columba livia). J Avian Med Surg 28:102–108. 10.1647/2013-027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruzen CL, Baum ST, Colman RJ. 2011. Glucoregulatory function in adult rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) undergoing treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate for endometriosis. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 50:921–925. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Driancourt MA, Briggs JR. 2020. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist implants for male dog fertility suppression: a review of mode of action, efficacy, safety, and uses. Front Vet Sci 7:483. 10.3389/fvets.2020.00483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser HM, Sandow J, Seidel H, von Rechenberg W. 1987. An implant of a gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (buserelin) which suppresses ovarian function in the macaque for 3-5 months. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 115:521–527. 10.1530/acta.0.1150521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geyer A, Daub L, Otzdorff C, Reese S, Braun J, Walter B. 2016. Reversible estrous cycle suppression in prepubertal female rabbits treated with slow-release deslorelin implants. Theriogenology 85:282–287. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goericke-Pesch S, Georgiev P, Atanasov A, Albouy M, Navarro C, Wehrend A. 2013. Treatment of queens in estrus and after estrus with a GnRH-agonist implant containing 4.7 mg deslorelin; hormonal response, duration of efficacy, and reversibility. Theriogenology 79:640–646. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein SR, Horii SC, Snyder JR, Raghavendra BN, Subramanyam B. 1988. Estimation of nongravid uterine volume based on a nomogram of gravid uterine volume: its value in gynecologic uterine abnormalities. Obstet Gynecol 72:86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guthrie A, Strike T, Patterson S, Walker C, Cowl V, Franklin AD, Powell DM. 2021. The past, present and future of hormonal contraceptive use in managed captive female tiger populations with a focus on the current use of deslorelin acetate. Zoo Biol 40:306–319. 10.1002/zoo.21601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbert CA, Trigg TE, Renfree MB, Shaw G, Eckery DC, Cooper DW. 2005. Long-term effects of deslorelin implants on reproduction in the female tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii). Reproduction 129:361–369. 10.1530/rep.1.00432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson JG. 2013. Therapeutic review: deslorelin acetate subcutaneous implant. J Exot Pet Med 22:82–84. 10.1053/j.jepm.2012.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kauffold J, Rohrmann H, Boehm J, Wehrend A. 2010. Effects of long-term treatment with the GnrH agonist deslorelin (Suprelorin) on sexual function in boars. Theriogenology 74:733–740. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koeppel KN, Barrows M, Visser K. 2014. The use of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog deslorelin for short-term contraception in red pandas (Ailurus fulgens). Theriogenology 81:220–224. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson S, Belting T, Rifenbury K, Fisher G, Boutelle SM. 2013. Preliminary findings of fecal gonadal hormone concentrations in six captive sea otters (Enhydra lutris) after deslorelin implantation. Zoo Biol 32:307–315. 10.1002/zoo.21032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez G, Lacoste R, Dumasy M, Garbit S, Brouillet S, Coutton C, Arnoult C, Druelle F, Molina-Vila P. 2020. Deslorelin acetate implant induces transient sterility and behavior changes in male olive baboon (Papio anubis): A case study. J Med Primatol 49:344–348. 10.1111/jmp.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattison JA, Ottinger MA, Powell D, Longo DL, Ingram DK. 2007. Endometriosis: clinical monitoring and treatment procedures in rhesus monkeys. J Med Primatol 36:391–398. 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2006.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton ML, Bashaw MJ, del Castillo SM, Jöchle W, Lamberski N, Rieches R, Bercovitch FB. 2006. Long-term suppression of fertility in female giraffe using the GnRH agonist deslorelin as a long-acting implant. Theriogenology 66:431–438. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penfold LM, Norton T, Asa CS. 2021. Effects of GnRH agonists on testosterone and testosterone-stimulated parameters for contraception and aggression reduction in male lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus). Zoo Biol 40:541–550. 10.1002/zoo.21635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petritz OA, Guzman DS, Hawkins MG, Kass PH, Conley AJ, Paul-Murphy J. 2015. Comparison of two 4.7-milligram to one 9.4-milligram deslorelin acetate implants on egg production and plasma progesterone concentrations in Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica). J Zoo Wildl Med 46:789–797. 10.1638/2014-0210.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenfield D, Viau P, Alvarenga C, Pizzutto C. 2016. Effectiveness of the GnRH analogue deslorelin as a reversible contraceptive in a neotropical primate, the common marmoset Callithrix jacchus (Mammalia: Primates: Callitrichidae). J Threat Taxa 8:8652–8658. 10.11609/jott.2305.8.4.8652-8658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu K. 2008. Reproductive hormones and the ovarian cycle in macaques. J Mamm Ova Res 25:122–126. 10.1274/0916-7625-25.3.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan EL, Daniels AJ, Koegler FH, Cameron JL. 2005. Evidence in female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) that nighttime caloric intake is not associated with weight gain. Obes Res 13:2072–2080. 10.1038/oby.2005.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Summa NM, Guzman DS, Wils-Plotz EL, Riedl NE, Kass PH, Hawkins MG. 2017. Evaluation of the effects of a 4.7-mg deslorelin acetate implant on egg laying in cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus). Am J Vet Res 78:745–751. 10.2460/ajvr.78.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Virbac AH. Inc. 2012. Deslorelin. [Package insert]. Fort Worth, TX.

- 33.Wagner R, Finkler M, Fecteau K, Trigg T. 2009. The treatment of adrenal cortical disease in ferrets with 4.7-mg deslorelin acetate implants. J Exot Pet Med 18:146–152. 10.1053/j.jepm.2008.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner RA, Piché CA, Jöchle W, Oliver JW. 2005. Clinical and endocrine responses to treatment with deslorelin acetate implants in ferrets with adrenocortical disease. Am J Vet Res 66:910–914. 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker ML, Gordon TP, Wilson ME. 1983. Menstrual cycle characteristics of seasonally breeding rhesus monkeys. Biol Reprod 29:841–848. 10.1095/biolreprod29.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker ML, Wilson ME, Gordon TP. 1984. Endocrine control of the seasonal occurrence of ovulation in rhesus monkeys housed outdoors. Endocrinology 114:1074–1081. 10.1210/endo-114-4-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace P, Asa C, Agnew M, Cheyne S. 2016. A review of population control methods in captive-housed primates. Anim Welf 25:7–20. 10.7120/09627286.25.1.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinbauer GF, Niehoff M, Niehaus M, Srivastav S, Fuchs A, Van Esch E, Cline JM. 2008. Physiology and endocrinology of the ovarian cycle in macaques. Toxicol Pathol 36 7_suppl:7S–23S. 10.1177/0192623308327412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]