Abstract

Survival rodent surgery requires the use of sterile instruments for each animal, which can be challenging when performing multiple surgeries on batches of animals. Glass bead sterilizers (GBS) are widely considered to facilitate this practice by sterilizing the tips of the instruments between animals. However, other disciplines have raised questions about the efficacy of the GBS, especially when used with surgical tools that have grooves or ridges that may contain organic debris. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of the GBS to sterilize instruments commonly used in rodent surgery by intentionally contaminating a selection of instruments with a standardized bacterial broth inoculated with Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. As expected, a simple ethanol wipe was ineffective in sterilizing instruments in all treatment groups. An ethanol wipe followed by GBS was effective in sterilizing 82.5% (99 of 120) of the instruments. Our study suggests that the GBS may not be effective for consistent sterilization of surgical instruments.

Abbreviations: GBS, glass bead sterilizer

Introduction

Survival rodent surgery in biomedical research requires the use of sterile instruments for each animal. Fulfilling this requirement can be challenging when performing multiple surgeries in batches with many animals undergoing surgery in one session because of potential difficulty in ensuring a sterile set of tools for every surgery. Maintenance and care of dozens of surgical instrument packs may not be feasible and relying on autoclaving or chemical sterilants between animals would complicate the efficient performance of surgeries due to the prolonged time required to sterilize instruments. The use of ethanol is not adequate because it is considered a disinfectant, not a sterilant.7,11,18 Soaking instruments in ethanol is not a suitable a sterilization method8 and may not even thoroughly clean the instruments.5 In light of these concerns, the use of the glass bead sterilizer (GBS) is widely used in the United States to sterilize instrument tips between individual rodents when doing batches of surgeries.9

The GBS works by using electric heaters to heat glass beads in an insulated container to a temperature range of 450 °F and 515 °F (Figure 1). To sterilize instruments, the operator removes all organic debris and then places the instrument tips into the well containing the glass beads for 15 seconds, based on manufacturer recommendations.6 However, other professions have evaluated the efficacy of the GBS with varying conclusions. For example, studies evaluating the use of a GBS for the sterilization of acupuncture needles determined that the GBS consistently and effectively eradicated bacteria from acupuncture needles,21 although concerns were still raised about the ability to remove hardier disease-causing agents, such as prions.10 Other specialties, such as chiropody and dentistry, have noted that these devices are not completely reliable in the sterilization of instruments.13,14,16,19,23,24 Failure to sterilize instruments may be due to variations in temperature within the well.4 The dental profession has performed significant evaluation of the use of the GBS with conflicting results. Some data indicate that the GBS is effective on specific types of equipment such as orthodontic bands22 and long-shank burrs,20 especially if coupled with other treatments, such as the use of ethanol.15 The inconsistencies in responses led the American Dental Association to publish guidance that GBS should not be used by their members.12 In addition, the Centers for Disease Control have issued guidance that these devices should not be used in hospital settings.17

Figure 1.

Photograph of a hot bead sterilizer. Glass beads fill the well in the center and are heated temperature range between 450°F and 515°F. Manufacturer recommendations states that decontamination of tool tips requires 15 seconds contact time in beads.

This study was designed to assess the ability of a GBS to sterilize instruments commonly used in rodent survival surgeries. Our use of the GBS included wiping organic debris off the surface of the instrument before placing the instrument in the well for 15 s.3 Our experimental design was based on the premise that sterility is either maintained or broken during surgery. The presence of any bacteria remaining on the instruments after processing would indicate failure of the GBS. The results of in this study can provide additional guidance to laboratory animal practitioners formulating policies for survival surgical procedures for their animal care and use programs.

Materials and Methods

Instruments.

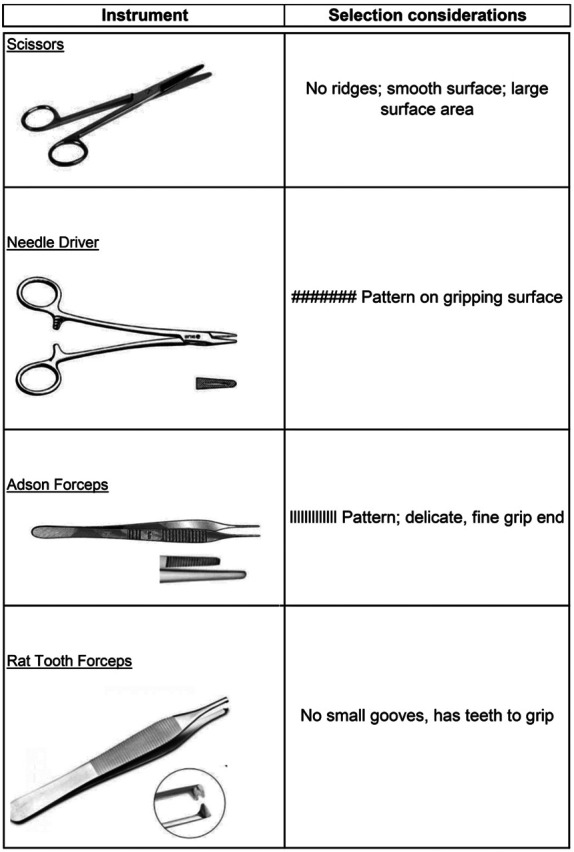

Recognizing that instruments without significant ridges or burrs might be more easily sterilized, an assortment of instruments with variable designs were selected for evaluation (Figure 2). These instruments were chosen based on both frequency of use in survival rodent surgery and the presence or absence of small grooves. The Adson forceps have a small pad with many shallow grooves. In comparison with the Adson forceps, the rat tooth forceps are about the same size but do not have a grooved gripping surface. In studies with dental instruments, burrs (covered in small grooves and having “highly complex and detailed surface features”) were likely to fail sterilization in the GBS.14 All instruments were sterilized in a steam autoclave before use in this study.

Figure 2.

Surgical instruments tested and their special characteristics.

Glass Bead Sterilizer.

The Glass Bead Sterilizer (Germinator 500, CellPoint Scientific) was filled with clean glass beads specifically intended for this device. The instrument has an indicator light that turns on once the internal thermometer reached the set point of 500 °F ± 15 °F. The experiment commenced once the indicator light was illuminated. Use of this instrument was consistent with manufacturer guidelines.6

Treatment groups.

Four treatment groups were established: (1) negative control [sterile instruments, not contaminated]; (2) positive control [contaminated, no other manipulation]; (3) ethanol wiping only [contaminated and wiped with ethanol]; and (4) ethanol with GBS [contaminated, wiped with ethanol, placed in GBS]. When performing the wipe of the tools, we saturated a gauze square with ethanol and made one, smooth, continuous movement down the instrument. We gripped the instrument with the intent to touch the complete surface of the instrument with the gauze. This wipe was performed to mimic common, regular working procedures during rodent survival surgery.

Treatments were as follows:

-

(1)

Negative control – Sterile, autoclaved instruments (8 instruments, 2 of each type: scissors, needle drivers, Adson forceps, and rat tooth forceps) were taken from the sterile pack and immediately dipped for 2 s into a tube of sterile thioglycolate broth media.

-

(2)

Positive control – Sterile, autoclaved instruments (8 instruments, 2 of each type: scissors, needle drivers, Adson forceps, and rat tooth forceps) were individually dipped for 2 s in thioglycolate broth containing bacteria and then dipped for 2 s into a tube of sterile thioglycolate broth.

-

(3)

Sterile, autoclaved instruments (60 instruments (15 of each type: scissors, needle drivers, Adson forceps, and rat tooth forceps) were inoculated by dipping them one at a time in bacterial broth for 2 s. Each instrument was wiped with gauze saturated with 70% ethanol and then dipped for 2 s into a tube of sterile thioglycolate broth.

-

(4)

Sterile, autoclaved instruments (60 instruments, of each type: scissors, needle drivers, Adson forceps, and rat tooth forceps) were inoculated by dipping them one at a time in bacterial broth for 2 s. Each instrument was wiped with gauze saturated with 70% ethanol and placed in the GBS for 15 s based on manufacturer’s directions. Each instrument was then dipped for 2 s into a tube of sterile thioglycolate broth.

Microbiology.

Bacterial thioglycolate broth was inoculated with American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) bacterial strains Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and incubated at 95 ± 3 °F (35 ± 2 ºC) for 18 to 24 h. Bacterial concentrations in the broth were determined by standard plate count methods to be 2.2 × 109 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL for S. aureus and 1.9 × 109 CFU/mL for E. coli.

Sterile instruments were contaminated by submersion of approximately 4 cm of the instrument in the bacterial broth for 2 s. The tube was slightly agitated before the instrument tip contamination to ensure a uniform suspension of bacteria in the broth. After the assigned treatment, instrument tips were submerged in sterile thioglycolate broth tubes. The broth tubes were incubated at 95 ± 3 °F (35 ± 2 ºC) for 48 h. Broth cultures with no visible growth at 48 h were considered negative. Cloudy broth, indicating bacterial growth, was subcultured to blood agar and incubated at 95 ± 3 °F (35 ± 2 ºC) for 48 h. Bacterial species were identified by mass spectrometry (MALDI Biotyper, Bruker, Billerica, MA).

Results

Culture data are presented in Table 1. None of the sterilized instruments produced any bacterial growth in the sterile broth tubes (negative control). Both bacterial species were recovered from all the broth tubes inoculated by exposure to the contaminated untreated instruments (the positive control). Both bacterial species were also recovered from most broth tubes exposed to instruments that had been treated with either ethanol alone or ethanol with GBS. A simple wipe of the instrument with ethanol-saturated gauze did not achieve instrument sterilization for all instruments in any of the four groups. After the use of an ethanol wipe in combination with the GBS wipe, all Adson forceps and some instruments of the other 3 types tested as sterile. Some of the other 3 types of instruments (23.3% / 21 of the 90) remained positive for bacterial growth after an ethanol wipe followed by 15 s of exposure to a GBS. Combining results from all instruments in the ethanol with GBS treatment groups, 82.5% (99 of 120) of the total instruments were sterilized.

Table 1.

Results of bacterial growth. Number of positive tubes and total number of inoculated tubes, with percentage of positive tubes shown in parentheses.

| Treatment | Scissors | Needle Driver | Adson Forceps | Rat Tooth Forceps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | 0 of 2 (0%) E. coli 0 of 2 (0%) S. aureus |

0 of 2 (0%) E. coli 0 of 2 (0%) S. aureus |

0 of 2 (0%) E. coli 0 of 2 (0%) S. aureus |

0 of 2 (0%) E. coli 0 of 2 (0%) S. aureus |

| Positive control | 2 of 2 (100%) E. coli 2 of 2 (100%) S. aureus |

2 of 2 (100%) E. coli 2 of 2 (100%) S. aureus |

2 of 2 (100%) E. coli 2 of 2 (100%) S. aureus |

2 of 2 (100%) E. coli 2 of 2 (100%) S. aureus |

| Ethanol wipe | 11 of 15 (73%) E. coli 11 of 15 (73%) S. aureus |

11 of 15 (73%) E. coli 11 of 15 (73%) S. aureus |

9 of 15 (60%) E. coli 10 of 15 (67%) S. aureus |

11 of 15 (73%) E. coli 11 of 15 (73%) S. aureus |

| Ethanol wipe with GBS | 4 of 15 (26%) E. coli 4 of 15 (26%) S. aureus |

2 of 15 (13%) E. coli 4 of 15 (26%) S. aureus |

0 of 15 (0%) E. coli 0 of 15 (0%) S. aureus |

4 of 15 (26%) E. coli 3 of 15 (20%) S. aureus |

Discussion

Our data indicate that neither alcohol alone nor alcohol with GBS was always effective in sterilizing surgical instruments. A simple wipe of the instrument with ethanol-saturated gauze was completely ineffective in sterilizing all instruments in a set. An ethanol wipe followed by 15 s of exposure to a GBS was also ineffective in completely sterilizing 3 of the 4 instrument types. However, given that the techniques for contamination and sterilization were the same for all instruments, these differences could be due to instrument surface area, as the Adson forceps were slightly smaller and thinner than all other instruments in our study. The rat tooth forceps were comparable in width, but not in all dimensions. The grooved surface of the pads of the Adson forceps did not increase the risk of contamination as originally hypothesized.

Additional studies investigating the efficacy of longer exposure times in the GBS or longer exposure to ethanol (such as soaking instruments in ethanol) may inform updated recommendations on sterilization procedures for instruments used in survival rodent surgery.7,8 Asepsis is defined as the absence of pathogenic microorganisms that cause infection,2 and aseptic technique is the method adopted to eliminate all potential sources of contamination of the surgical field. Adopting high standards of asepsis will reduce the risk of postsurgical wound infections. Therefore, aseptic technique is an important component of successful surgical outcomes and is used to reduce microbial contamination to the lowest possible practical level.9 However, no procedure, piece of equipment, or germicide alone can achieve that objective. Asepsis can be achieved only through proper preparations of the animal, surgeon, and equipment and the use of proper technique.

Research results can be altered significantly or invalidated due to local or systemic infections caused by breaks in aseptic technique. Aseptic surgery uses procedures that limit microbial contamination so that infection does not occur.18 In biomedical research settings, rodent surgeries are often performed in batches of multiple animals that undergo the same surgical procedure in one session. GBS is a generally accepted method for sterilization of instrument tips between animals undergoing surgery in the same session.3 Sterilization of instruments between each animal is important to minimize the risk of infection. Infection can increase inflammation, delay healing, and potentially alter research results. In addition, poor aseptic technique can result in infections that may cause pain, distress, and if severe, can result dehiscence at the surgery site, generalized infections, severe illness, animal suffering, or animal death. Even low-grade infections change the animal’s physiology in ways that may interact or interfere with specific research procedures.7

Our goal for this project was to evaluate the effectiveness of GBS for surgical instrument sterilization. Rodent survival surgery in biomedical research requires aseptic technique and sterile instruments for both animal welfare and accurate data.1 Our results indicate that the GBS used according to recommended practices does not ensure instrument sterility and alternate methods of sterilization should be used to ensure aseptic technique.

References

- 1.Animal Welfare Regulations.2013. 9 CFR § 3.129.

- 2.Bausch SJ. 2011. The operating room and asepsis, p. 66–73. In: Tear M, editor. Small animal surgical nursing. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernal J, Baldwin M, Gleason T, Kuhlman S, Moore G, Talcott M. 2009. Guidelines for rodent survival surgery. J Invest Surg. 22:445–451. 10.3109/08941930903396412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corner GA. 1987. An assessment of the performance of a glass bead sterilizer. J Hosp Infect 10:308–311. 10.1016/0195-6701(87)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa DM, Lopes LKO, Hu H, Tipple AFV, Vickery K. 2017. Alcohol fixation of bacteria to surgical instruments increases cleaning difficulty and may contribute to sterilization inefficacy. Am J Infect Control 45:e81–e86. 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.04.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Electron Microscope Sciences. [Internet]. Instructional manual CAT 66118-10, 66118-20 EMS germinator 500. [Cited 30 August 2021]. Available at https://www.emsdiasum.com/microscopy/technical/manuals/66118.pdf.

- 7.Huerkamp MJ. 2002. Alcohol as a disinfectant for aseptic surgery of rodents: crossing the thin blue line? Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 41:10–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard HL, Haywood JR, Laber K. 2001. Alcohol as a disinfectant. AAALAC International Connection; (Winter/Spring: ): 16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jørgensen VR, Rosted P. 2001. Non-disposable acupuncture needles are potential hazards of transmission of prion diseases. Ugeskr Laeger 163:1295–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keen JN, Austin M, Huang LS, Messing S, Wyatt JD. 2010. Efficacy of soaking in 70% isopropyl alcohol on aerobic bacterial decontamination of surgical instruments and gloves for serial mouse laparotomies. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 49:832–837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM. 2003. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 52:1–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar KV, Kiran Kumar KS, Supreetha S, Raghu KN, Veerabhadrappa AC, Deepthi S. 2015. Pathological evaluation for sterilization of routinely used prosthodontic and endodontic instruments. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 5:232–236. 10.4103/2231-0762.159962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathivanan A, Saisadan D, Manimaran P, Kumar CD, Sasikala K, Kattack A. 2017. Evaluation of efficiency of different decontamination methods of dental burs: an in vivo study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 9:37–40. 10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_81_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nisalak P, Prachyabrued W, Leelaprute V. 1990. Glass bead sterilization of orthodontic pliers. J Dent Assoc Thai 40:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raju TB, Garapati S, Agrawal R, Reddy S, Razdan A, Kumar SK. 2013. Sterilizing endodontic files by four different sterilization methods to prevent cross-infection - an in-vitro study. J Int Oral Health 5:108–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutala WA, Weber DJ. 2008. Centers for Disease Control. Sterilization, p. 59–80. Guideline for disinfection and sterilization in healthcare facilities. Washington (DC): Centers for Disease Control (US). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutala WA, Weber DJ. 2019. Disinfection, sterilization, and antisepsis: an overview. Am J Infect Control 47:A3–A9. 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SajjanShetty S, Hugar D, Hugar S, Ranjan S, Kadani M. 2014. Decontamination methods used for dental burs: a comparative study. J Clin Diagn Res 8:ZC39–41. 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9314.4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schutt RW, Starsiak WJ. 1990. Glass bead sterilisation of surgical dental burs. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 19:250–251. 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80404-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisco V, Winters LL, Zange LL, Brennan PC. 1988. Efficacy of various methods of sterilization of acupuncture needles. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 11:94–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith GE. 1986. Glass bead sterilization of orthodontic bands. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 90:243–249. 10.1016/0889-5406(86)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venkatasubramanian R, Das UM, Bhatnagar S. 2010. Comparison of the effectiveness of sterilizing endodontic files by 4 different methods: an in vitro study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 28:2–5. 10.4103/0970-4388.60478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zadik Y, Peretz A. 2008. The effectiveness of glass bead sterilizer in the dental practice. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim 25:36–39, 75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]