Abstract

Purpose

To study the wider field (WF) swept-source OCT angiography (SS-OCTA) metrics, especially the nonperfusion area (NPA), in the diagnosing and staging of diabetic retinopathy (DR).

Design

Cross-sectional observational study (November 2018 to September 2020).

Participants

A total of 473 eyes of 286 patients (69 eyes of 49 control patients and 404 eyes of 237 diabetic patients).

Methods

We imaged using 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm angiograms on WF SS-OCTA. Images were analyzed using the ARI Network and FIJI ImageJ. Mixed effects multiple regression models and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis were used for statistical analyses.

Main Outcome Measures

Quantitative metrics such as vessel density (VD); vessel skeletonized density (VSD); foveal avascular zone (FAZ) area, circularity, and perimeter; and NPA in DR and their relative performance for its diagnosis and grading.

Results

Among patients with diabetes (median age, 59 years), 51 eyes had no DR, 185 eyes (88 mild, 97 moderate-severe) had nonproliferative DR (NPDR), and 168 eyes had proliferative DR (PDR). Trend analysis revealed a progressive decline in superficial capillary plexus (SCP) VD and VSD, and increased NPA with increasing DR severity. Additionally, there was a significant reduction in deep capillary plexus (DCP) VD and VSD in early DR (mild NPDR), but the progressive reduction in advanced DR stages was not significant. The NPA was the best parameter to diagnose DR (area under the curve [AUC], 0.96), whereas all parameters combined on both angiograms efficiently diagnosed (AUC, 0.97) and differentiated between DR stages (AUC range, 0.83–0.97). The presence of diabetic macular edema was associated with reduced SCP and DCP VD and VSD within mild NPDR eyes, whereas increased VD and VSD in SCP were observed in the moderate-severe NPDR group.

Conclusions

Our work highlights the importance of NPA, which can be measured more readily and easily with WF SS-OCTA compared with fluorescein angiography. It is quick and noninvasive, and thus can be an important adjunct for DR diagnosis and management. In our study, a combination of all OCTA metrics on both 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm angiograms had the best diagnostic accuracy for DR and its severity. Further longitudinal studies are needed to assess NPA as a biomarker for progression or regression of DR severity.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy classification, Ischemia index, Nonperfusion area, OCT angiography, OCTA Quantitative vascular metrics

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AUC, area under the curve; BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; CFP, color fundus photography; DCP, deep capillary plexus; DM, diabetes mellitus; DME, diabetic macular edema; DR, diabetic retinopathy; FA, fluorescein angiography; FAZ, foveal avascular zone; FOV, field of view; logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; NPA, nonperfusion area; NPDR, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; OCTA, OCT angiography; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SCP, superficial capillary plexus; SS-OCTA, swept-source OCT angiography; UWF, ultra-widefield; VD, vessel density; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VSD, vessel skeletonized density; WF, wider field

Nearly half a billion people (9.3% of adults aged 20–79 years) are living with diabetes mellitus (DM) worldwide.1 Approximately one-third of them are estimated to have diabetic retinopathy (DR), and a further one-third of those develop vision-threatening DR, that is, proliferative DR (PDR) or diabetic macular edema (DME).2 Considering its economic burden, efficient management depends on early diagnosis and accurate staging, which is further based on the implementation of the most appropriate imaging modality. The gold standard for DR grading is based on a classification using 7 standard fields of color fundus photography (CFP) by the ETDRS grading system. This captures the central posterior 90° field of view (FOV), approximately 30% of the retina. Ultra-widefield (UWF) can capture 200° of FOV, that is, 82% of the retina3 with a shorter acquisition time and similar clinical efficacy for DR diagnosis.4 Silva et al3 suggested a more severe DR grading in 10% of eyes with UWF imaging compared with the standard CFP. Beyond CFP, fluorescein angiography (FA) enhances the detection of microvascular changes but has several disadvantages of being invasive and time-consuming, as well as the potential risk of anaphylaxis to the dye. A recent editorial by Sun et al5 suggested the need of an updated DR grading system incorporating the systemic health status along with modern multimodal imaging techniques, calling for the need of quantitative DR staging system.

OCT angiography (OCTA) has emerged as a noninvasive alternative to FA.6 It has several advantages, as it is dyeless and noninvasive, and providing depth-resolved information of the superficial capillary plexus (SCP) and deep capillary plexus (DCP), besides structural slabs. With higher image resolution, it allows for quantification at the capillary microvasculature level, such as the measurement of vessel density (VD), vessel skeletonized density (VSD), and size and shape of the foveal avascular zone (FAZ).7 Following the introduction of OCTA, quantitative changes in the retinal vasculature have been described in DR using 3 × 3 mm angiograms from spectral-domain OCTA, almost all of which come from smaller studies.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 The OCTA FOV with commercially available systems was limited to 3 × 3 mm and 6 × 6 mm angiograms until recently. These scan types can only detect changes within the central macular area. By acquiring angiograms with a wider FOV than the commercially available OCTA devices, for example, 12 × 12 mm (∼50°–60° FOV) and 15 × 15 mm (∼60°–70° FOV) angiograms, wider field (WF) swept-source OCTA (SS-OCTA) can highlight the early capillary dropout, potentially altering how we manage DR. Hirano et al15 imaged 60 DR eyes with 3 × 3 mm, 6 × 6 mm, and 12 × 12 mm FOV, and described a significant decline in nonproliferative DR (NPDR) relative to diabetic persons with no evidence of DR (no DR) and PDR versus NPDR. Moreover, Tan et al16 described a significant decline in vessel metrics when comparing mild NPDR with no DR and moderate-severe NPDR with mild NPDR in 76 DR eyes using 12 × 12 mm FOV.

Because the mid-peripheral retina bears the major brunt of diabetic microangiopathy in the form of capillary occlusion, widefield retinal imaging is a promising approach for DR prognostication.17, 18, 19 Widefield OCTA has a high sensitivity and specificity for detection of nonperfusion area (NPA) relative to UWF FA.20 Couturier et al21 described additional areas of NPA missed on FA. However, the available data using 12 × 12 mm FOV for DR staging are still sparse. Besides vessel metrics and FAZ, only 2 studies evaluated NPA on a smaller cohort. Tan et al16 did not report the diagnostic accuracy of NPA for diagnosing the presence of DR and its severity. The recently published work by Kim et al22 reported the receiver operating characteristics (ROCs) for both VD and NPA, but the dichotomous groups were presented as a combination of widely varying DR grading. Although all these quantitative metrics have been studied before in various angiogram sizes and OCTA devices, it is yet unclear as to which is the most sensitive and accurate parameter for detecting DR and its severity.

We investigate the use of WF SS-OCTA for its precise quantification of various retinal vascular metrics and to determine the diagnostic accuracy of various parameters including NPA, VD, VSD, FAZ area, FAZ perimeter, and FAZ circularity for diagnosing the presence of DR and discriminating its severity. For a secondary objective, we also investigated the effect of DME on these metrics within eyes from the same DR severity group.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional observational study at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Harvard Medical School, from November 2018 to September 2020. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary (2019P001863). Written detailed informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Our research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations.

Study Subjects

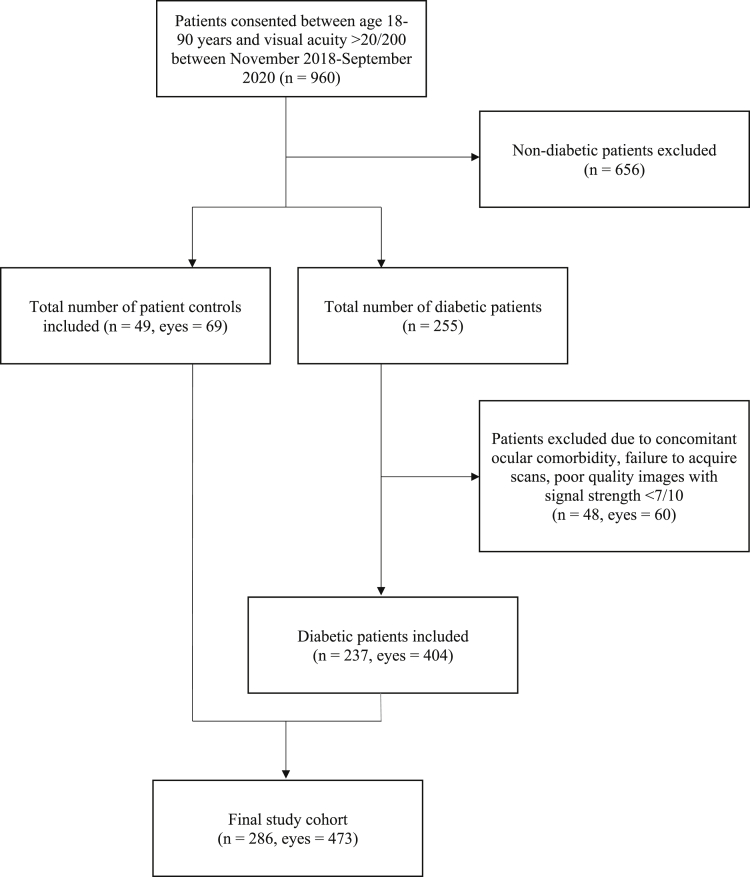

A total of 960 patients from the age group 18 to 90 years with a minimum Snellen’s best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/200 consented to participate in the study (Fig 1). Of these, 255 were patients diagnosed with DM, of whom 60 eyes of 48 patients were excluded because of inadequate image quality or presence of ocular comorbidities, such as concomitant chorioretinal disease, open-angle glaucoma, angle-closure glaucoma, optic neuropathy, pathological myopia, refractive error of more than −6 diopters (D), severe media opacity, vein occlusion, or arterial occlusion. For our cohort of control eyes, we included patients presenting to the retina service for a routine eye examination. The control eyes may have presented for conditions such as posterior vitreous detachment, lattice without myopia, peripheral retinal breaks, or fellow eyes of ocular trauma or retinal detachment. We excluded patients with a systemic diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes and no ocular comorbidity such as glaucoma, myopia, and optic neuropathy.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of study recruitment.

Study Protocol

We performed a complete ophthalmic examination for all patients including BCVA, intraocular pressure measurement, slit-lamp, and dilated fundus examination. Trained research fellows acquired 12 × 12 mm and 6 × 6 mm angiogram images centered on the fovea for all patients with a 100 kHz SS-OCTA instrument (PLEX Elite 9000, Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc.) that uses a tunable laser of central wavelength of 1040 to 1060 nm with a bandwidth of 100 nm. It has an A-scan depth of 3 mm (in tissue), axial resolution (optical) of 6.3 μm (in tissue), axial resolution (digital) of 1.95 μm (in tissue), and a transverse resolution of 20 μm. The 12 × 12 mm angiogram has an approximately 50° to 60° FOV of the central posterior pole of retina, and the 6 × 6 mm angiogram captures the central macular area. Spectralis OCT2 B-scan (Heidelberg Engineering), UWF CFP, or UWF FA (Optos) was acquired the same day. The grading of DR was done by experienced senior retina faculty (J.B.M., D.G.V., D.H., J.W.M., D.M.W., L.A.K.) based on the clinical exam and the ancillary imaging using International Clinical DR Disease Severity Scale.23 For the purpose of this study, we combined the eyes with moderate NPDR and severe NPDR in a common group with moderate-severe NPDR. This was done to reduce the potential error in misclassification given their nearly overlapping diagnostic criteria based on CFP and clinical examination.

Systemic and Ocular Parameters

An in-depth review of electronic medical records was performed for all patients to record all systemic and ocular parameters. Among systemic parameters, we recorded age, gender, race, duration of DM, type of DM, dependency on insulin, body mass index, mean arterial blood pressure, smoking status, and glycosylated hemoglobin. The ocular parameters included BCVA, IOP, lens status, presence or absence of DME, ocular comorbidity, history of therapeutic interventions such as focal laser, panretinal photocoagulation, anti-VEGF therapy, and pars plana vitrectomy.

Image Processing and Analysis

We controlled for image quality by excluding images with signal strength <7. We further excluded poor-quality images due to media opacity, defocus, and presence of various artifacts (motion, edge, threshold), as previously mentioned. We used the same screen with standard parameters and illumination settings for evaluation of all images. A single experienced grader evaluated all images for quality control (I.G.) with confirmation by the senior author (J.B.M.). Macular Density v0.7.3 on the ARI Network (Zeiss Portal v5.4-1206) was used for the calculation of quantitative OCTA metrics such as VD and VSD on SCP, DCP, and full-thickness retina slabs, and FAZ metrics on the superficial retinal layer (Figs 2 and 3). The algorithm uses legacy segmentation to define superficial slab between the inner limiting membrane and 70% of the distance between it and the outer plexiform layer. The deep slab is defined between the inner plexiform layer and the outer plexiform layer, 110 μm above the retinal pigment epithelium–fit line. The deep slabs were generated after projection artifact removal. The VD was defined as the total area of perfused vasculature per unit area in a region of measurement, ranging from zero to 1. It was calculated after binarization of the angiogram layers to generate a black and white image. The VSD was defined as the total length of skeletonized vessels, that is, each binarized vessel was converted to a line of 1 pixel width, per unit area of measurement. While VD provides complete vasculature information in terms of size and length, VSD evaluates only the length, reducing the weightage of large vessels, and thus VSD may be more sensitive to the retinal microvasculature changes that many clinicians and researchers seek to identify.24 The FAZ parameters were assessed as area, perimeter, and circularity. Circularity was defined as a uniformity index with perfect circle having a value of 1. Additionally, superficial slabs of 12 × 12 mm angiograms were used to quantify NPA (mm2) with a semiautomated algorithm on FIJI (an expanded version of ImageJ: 2.0.0-rc-69/1.52p; National Institutes of Health)25 by a single experienced grader (I.G.). We used Huang’s fuzzy black and white thresholding using the cutoff derived from the pixel values of the FAZ. True NPA was reported after excluding the minor low-signal artifacts,26 if present (Fig 3, z-ad).

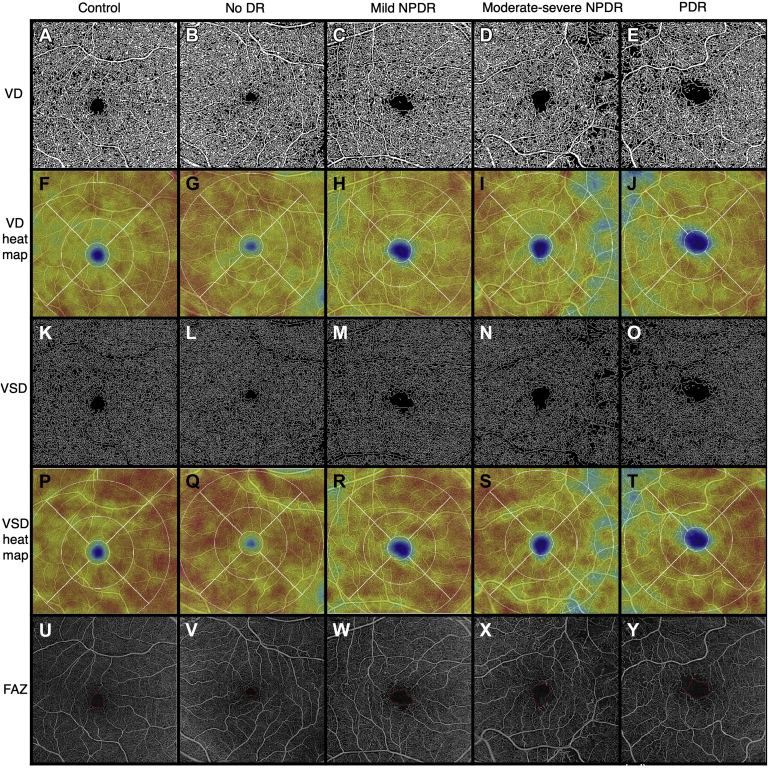

Figure 2.

Representative full-thickness 6 × 6 mm en face swept-source OCT angiography (SS-OCTA) images of control eyes and eyes from patients with diabetes with different stages of diabetic retinopathy (DR), obtained from the ARI network (Zeiss Portal v5.4-1206). Vessel density (VD) (A-E): binarized SS-OCTA images from different study groups. Vessel density heat map (F-J): color density maps with overlaying standardized ETDRS grid of the binarized images according to the VD distribution. Vessel skeletonized density (VSD) (K-O): skeletonized SS-OCTA images from different study groups. Vessel skeletonized density heat map (P-T): Color density maps with overlaying standardized ETDRS grid of the skeletonized images according to the VSD distribution. Foveal avascular zone (FAZ) (U-Y): Representative images outlining the FAZ. NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

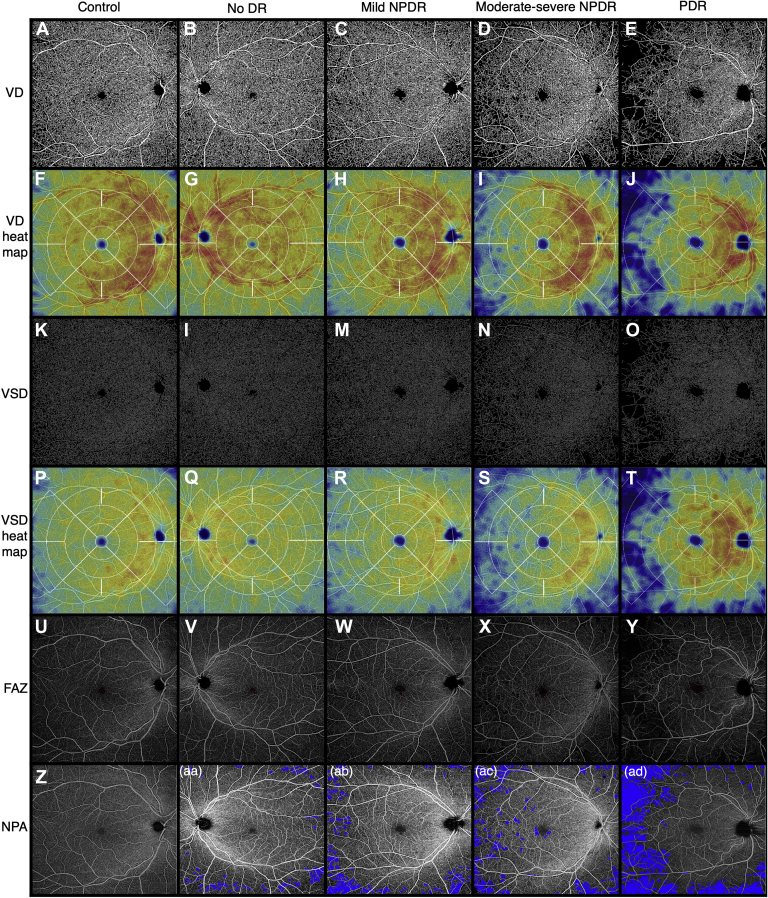

Figure 3.

Representative full-thickness 12 × 12 mm en face swept-source OCT angiography (SS-OCTA) images of control eyes and eyes from patients with diabetes with different stages of diabetic retinopathy (DR), obtained from the ARI network (Zeiss Portal v5.4-1206). Vessel density (VD) (A-E): binarized SS-OCTA images from different study groups. Vessel density heat map (F-J): color density maps with overlaying standardized ETDRS grid of the binarized images according to the VD distribution. Vessel skeleton density (VSD) (K-O): skeletonized SS-OCTA images from different study groups. Vessel skeleton density heat map (P-T): color density maps with overlaying standardized ETDRS grid of the skeletonized images according to the VSD distribution. Foveal avascular zone (FAZ) (U-Y): representative images outlining the FAZ. Nonperfusion area (NPA) (Z-ad): Representative images from superficial capillary plexus (SCP) with NPA shaded in blue color. NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.0.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and StataIC version 16.1 (StataCorp 2019. StataCorp LLC). The population demographics and ocular characteristics were described using traditional descriptive methods. The level of significance was set to 2-sided P value <0.05. Mixed-effects multiple linear regression models fit by restricted maximum likelihood were used to account for the correlation between the 2 eyes from the same patients. All initial multivariate models presented are adjusted for age, an established risk factor, followed by secondary models additionally controlling for prior therapeutic interventions besides age. We additionally performed post hoc Tukey’s honest significant difference multivariate analysis adjusting for multiple comparisons to compare the DME differences within the same DR grading group. The ROCs based on OCTA metrics were used to determine a cutoff value, sensitivity, and specificity. Area under the curve (AUC) describes the diagnostic efficacy, using the predicted probability of the study parameters for a patient with DR compared with the one without DR. A value of 1 equates to perfect prediction by the model, whereas values above 0.8 and 0.7 signify a strong model and good model, respectively. A value of 0.5 denotes that the model is no better than random chance, and below 0.5 indicates a poor model.

Results

Study Population

Our cohort comprised 473 eyes, of which 69 were control eyes. Among 404 eyes from 237 patients with a diagnosis of DM, 51 eyes had no evidence of DR. Of the 353 DR eyes, 185 eyes had NPDR (mild: 88 eyes, moderate-severe: 97 eyes) and 168 eyes had PDR. The demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and 2. There were 464 eyes with 6 × 6 mm (control: 69, no DR: 51, mild NPDR: 86, moderate-severe NPDR: 95, PDR: 163); 349 eyes with 12 × 12 mm (control: 54, no DR: 31, mild NPDR: 73, moderate-severe NPDR: 75, PDR: 116) angiograms; and 339 eyes with both 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm (control: 53, no DR: 31, mild NPDR: 71, moderate-severe NPDR: 73, PDR: 111).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Population

| Study Parameter (Median (IQR) or n (%) | Control (n = 49) | Patients with DM (n = 237) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 57 (45–63) | 59 (50–66) | 0.09 |

| Sex, Female | 19 (38.8) | 103 (43.46) | 0.66 |

| Race | 0.006 | ||

| White | 34 (72.3) | 129 (56.6) | |

| Black | 6 (12.8) | 46 (20.2) | |

| Asian | 3 (6.4) | 17 (7.5) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.1) | 34 (14.9) | |

| Other∗ | 3 (6.4) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Smoking | 0.44 | ||

| Never | 27 (67.5) | 129 (57.3) | |

| Former | 11 (27.5) | 76 (33.8) | |

| Current | 2 (5.0) | 20 (8.9) | |

| MABP, mmHg | 97.7 (89.1–102.5) | 95.0 (86.7–104.3) | 0.50 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.4 (22.7–30.3) | 30.7 (26.4–34.5) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.6 (5.5–5.7) | 8.0 (7.0–9.3) | <0.001 |

| Type of diabetes | - | ||

| 1 | 40 (16.9) | ||

| 2 | 197 (83.1) | ||

| Duration of DM, yrs | - | 19 (10–27) | |

| Received treatment with insulin | - | 171 (72.2) |

Values in bold are statistically significant (P < 0.05). BMI = body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters); DM = diabetes mellitus; HbA1c = glycosylated hemoglobin; IQR = interquartile range; MABP = mean arterial blood pressure.

Race, Other: American Indian, Latino, Middle eastern, Puerto Rico.

Based on Mann–Whitney U test or Pearson’s chi-square test of association with Yates’ continuity correction, when applicable.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Eyes, Organized by Study Groups

| Study Parameter Median (IQR) or n (%) | Control (n = 69) | No DR (n = 51) | Mild NPDR (n = 88) | Moderate-severe NPDR (n = 97) | PDR (n = 168) | P Value∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOP, mmHg | 16.0 (14.0–17.0) | 18.0 (15.0–19.0) | 17.0 (14.0–18.0) | 16.0 (15.0–19.0) | 16.0 (14.0–17.3) | 0.02 |

| BCVA (logMAR) | 0.00 (0.00–0.08) ∼20/20 |

0.02 (0.00–0.04) ∼20/20–1 |

0.04 (0.00–0.14) ∼20/20–2 |

0.12 (0.02–0.22) ∼20/25–1 |

0.18 (0.09–0.40) ∼20/32–1 |

<0.001 |

| Lens status | <0.001 | |||||

| Pseudophakia | 3 (4.35) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (20.45) | 23 (23.71) | 70 (41.67) | |

| Phakic | 66 (95.65) | 51 (100.0) | 70 (79.55) | 74 (76.29) | 97 (57.74) | |

| Aphakia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.60) | |

| Laterality, OD | 38 (55.1) | 25 (49.0) | 44 (50.0) | 54 (55.67) | 91 (54.17) | 0.89 |

| Prior history of focal laser | - | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 8 (8.25) | 13 (7.7) | 0.06 |

| Prior history of PRP | - | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.14) | 4 (4.12) | 128 (76.2) | <0.001 |

| Prior history of receiving anti-VEGF injection | - | 0 (0.0) | 13 (14.8) | 24 (24.74) | 85 (50.6) | <0.001 |

| Number of anti-VEGF injections, if received | - | - | 3.50 (1.0–5.25) | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–7.75) | 0.40 |

| Prior history of PPV | - | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 39 (23.21) | <0.001 |

| DME | - | 0 (0.0) | 21 (23.9) | 71 (73.20) | 91 (54.2) | <0.001 |

Values in bold are statistically significant (P < 0.05). BCVA = best-corrected visual acuity; DME = diabetic macular edema; DR = diabetic retinopathy; IOP = intraocular pressure; IQR = interquartile range; logMAR = logarithm of minimum angle of resolution; NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; OD = right eye; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PPV = pars plana vitrectomy; PRP = panretinal photocoagulation; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor.

Based on Kruskal–Wallis test or Pearson’s chi-square test of association with Yates’ continuity correction, when applicable.

Quantitative OCTA Metrics

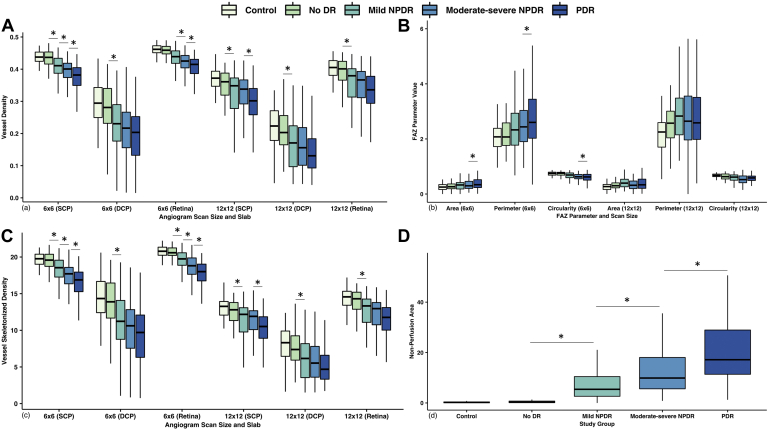

Vessel Density

We found a significant progressive decline in the SCP, DCP, and full-thickness retina VD in 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm angiograms across all the DR stages compared with controls (Table 3, Fig 4a). There was no significant difference between the control patients and no DR group on any angiogram. Compared with the preceding stage, mild NPDR eyes had significant reductions in SCP (6 × 6: ß = −0.02, P = 0.04; 12 × 12: ß = −0.04, P = 0.01), DCP (6 × 6: ß = −0.04, P = 0.01; 12 × 12: ß = −0.05, P = 0.01), and full-thickness retina (12 × 12: ß = −0.05, P = 0.01). The reduction on full-thickness retina of 6 × 6 mm angiogram closely missed the significance level (ß = −0.02, P = 0.051). Likewise, we observed reduction for the moderate-severe NPDR group on SCP (ß = −0.02, P = 0.02) and full-thickness retina (ß = −0.02, P = 0.01) of 6 × 6 mm angiograms. Additionally, the PDR group had a significant reduction in SCP (ß = −0.02, P = 0.003) and full-thickness retina (ß = −0.02, P = 0.01) of 6 × 6 mm and SCP (ß = −0.03, P = 0.01) of 12 × 12 mm angiograms. The 12 × 12 mm full-thickness retina also showed reductions but did not reach the level of statistical significance (ß = −0.02, P = 0.054). While adjusting for prior treatments, a similar trend was present except when comparing PDR eyes with moderate to severe NPDR.

Table 3.

Mixed-Effects Multiple Linear Regression Model Results by Study Group, Adjusted for Age (Model A) and Age along with Prior Therapeutic Interventions (Model B)

| Study Parameter | Control (n = 69) |

No DR (n = 51) |

Mild NPDR (n = 88) |

Moderate-Severe NPDR (n = 97) |

PDR (n = 168) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Model A |

Model B |

Median (IQR) | Model A |

Model B |

Median (IQR) | Model A |

Model B |

Median (IQR) | Model A |

Model B |

|||||||

| vs. Control β (P Value) |

vs. Control β (P Value) |

vs. Control β (P Value) |

vs. No DR β (P Value) |

vs. Control β (P Value) |

vs. No DR β (P Value) |

vs. Control β (P Value) |

vs. Mild NPDR β (P Value) |

vs. Control β (P Value) |

vs. Mild NPDR β (P Value) |

vs. control β (P Value) |

vs. moderate-severe NPDR β (P Value) |

vs. control β (p value) |

vs. moderate-severe NPDR β (P Value) |

||||||

| 6 × 6 mm | |||||||||||||||||||

| VD (SCP) | 0.44 (0.43–0.45) | 0.44 (0.42–0.45) | −0.01 (0.33) | −0.01 (0.33) | 0.41 (0.39–0.43) | −0.03 (0.001) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.001) | −0.02 (0.04) | 0.40 (0.37–0.42) | −0.05 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.04 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.052) | 0.38 (0.35–0.41) | −0.07 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.003) | −0.06 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.07) |

| VD (DCP) | 0.29 (0.25–0.34) | 0.28 (0.23–0.34) | −0.02 (0.26) | −0.02 (0.27) | 0.23 (0.18–0.29) | −0.06 (<0.001) | −0.04 (0.01) | −0.06 (<0.001) | −0.04 (0.02) | 0.22 (0.16–0.27) | −0.08 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.15) | −0.07 (<0.001) | −0.01 (0.29) | 0.20 (0.13–0.25) | −0.10 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.13) | −0.08 (<0.001) | −0.01 (0.59) |

| VD (Retina) | 0.46 (0.45–0.47) | 0.46 (0.45–0.47) | −0.01 (0.29) | −0.01 (0.28) | 0.44 (0.42–0.46) | −0.03 (0.001) | −0.02 (0.051) | −0.02 (0.001) | −0.02 (0.051) | 0.43 (0.40–0.44) | −0.04 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.04 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.42 (0.39–0.43) | −0.06 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.05 (<0.001) | −0.01 (0.12) |

| VSD (SCP) | 19.76 (19.01–20.39) | 19.58 (18.73–20.38) | −0.40 (0.36) | −0.38 (0.36) | 18.54 (17.27–19.57) | −1.32 (0.001) | −0.93 (0.03) | −1.31 (<0.001) | −0.92 (0.03) | 17.71 (16.35–18.58) | −2.35 (<0.001) | −1.03 (0.004) | −2.18 (<0.001) | −0.87 (0.01) | 16.88 (15.28–17.94) | −3.39 (<0.001) | −1.04 (0.001) | −3.22 (<0.001) | −1.04 (0.01) |

| VSD (DCP) | 14.34 (12.41–16.67) | 13.89 (11.67–16.45) | −0.90 (0.25) | −0.89 (0.26) | 11.23 (8.78–14.07) | −2.88 (<0.001) | −1.98 (0.01) | −2.80 (<0.001) | −1.92 (0.01) | 10.62 (7.56–12.82) | −3.95 (<0.001) | −1.08 (0.09) | −3.65 (<0.001) | −0.84 (0.19) | 9.71 (6.31–12.08) | −4.89 (<0.001) | −0.94 (0.09) | −4.21 (<0.001) | −0.56 (0.46) |

| VSD (Retina) | 20.79 (20.24–21.34) | 20.58 (20.24–21.24) | −0.38 (0.35) | −0.37 (0.34) | 19.75 (18.87–20.58) | −1.20 (0.001) | −0.82 (0.04) | −1.15 (0.001) | −0.78 (0.04) | 18.81 (17.64–19.88) | −2.29 (<0.001) | −1.09 (0.001) | −2.05 (<0.001) | −0.91 (<0.01) | 18.00 (16.74–19.03) | −3.23 (<0.001) | −0.94 (0.001) | −2.96 (<0.001) | −0.91 (0.02) |

| FAZ Area | 0.26 (0.17–0.34) | 0.25 (0.19–0.36) | −0.01 (0.92) | −0.01 (0.90) | 0.33 (0.18–0.42) | 0.05 (0.49) | 0.06 (0.47) | 0.05 (0.45) | 0.06 (0.42) | 0.30 (0.21–0.48) | 0.09 (0.20) | 0.04 (0.55) | 0.08 (0.25) | 0.03 (0.69) | 0.34 (0.23–0.48) | 0.21 (<0.001) | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.16 (0.057) | −0.08 (0.25) |

| FAZ Perimeter | 2.09 (1.74–2.39) | 2.04 (1.77–2.93) | −0.08 (0.82) | −0.08 (0.82) | 2.29 (1.76–2.93) | 0.28 (0.35) | 0.36 (0.29) | 0.30 (0.32) | 0.38 (0.26) | 2.52 (1.91–3.11) | 0.47 (0.12) | 0.18 (0.52) | 0.43 (0.15) | 0.13 (0.64) | 2.56 (2.02–3.37) | 1.14 (<0.001) | 0.68 (0.006) | 1.02 (0.006) | 0.59 (0.09) |

| FAZ Circularity | 0.75 (0.69–0.79) | 0.76 (0.69–0.79) | −0.01 (0.67) | −0.01 (0.67) | 0.69 (0.59–0.76) | −0.05 (0.058) | −0.04 (0.21) | −0.05 (0.052) | −0.04 (0.19) | 0.63 (0.55–0.71) | −0.08 (0.004) | −0.03 (0.31) | −0.07 (0.007) | −0.02 (0.44) | 0.62 (0.51–0.73) | −0.12 (<0.001) | −0.05 (0.03) | −0.13 (<0.001) | −0.06 (0.050) |

| 12x12 mm | |||||||||||||||||||

| VD (SCP) | 0.37 (0.35–0.39) | 0.36 (0.32–0.39) | −0.01 (0.46) | −0.01 (0.45) | 0.35 (0.28–0.37) | −0.05 (<0.001) | −0.04 (0.01) | −0.05 (<0.001) | −0.04 (0.02) | 0.34 (0.29–0.37) | −0.05 (0.001) | 0.01 (0.67) | −0.04 (0.002) | −0.01 (0.53) | 0.30 (0.26–0.34) | −0.08 (<0.001) | −0.03 (0.01) | −0.06 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.20) |

| VD (DCP) | 0.22 (0.18–0.27) | 0.20 (0.17–0.26) | −0.004 (0.85) | −0.004 (0.84) | 0.17 (0.10–0.22) | −0.05 (0.001) | −0.05 (0.01) | −0.05 (0.001) | −0.05 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.10–0.22) | −0.05 (0.001) | −0.002 (0.87) | −0.05 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.95) | 0.13 (0.09–0.18) | −0.07 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.14) | −0.06 (0.001) | −0.01 (0.45) |

| VD (Retina) | 0.41 (0.38–0.43) | 0.40 (0.37–0.42) | −0.01 (0.69) | −0.01 (0.68) | 0.38 (0.31–0.40) | −0.05 (<0.001) | −0.05 (0.01) | −0.05 (<0.001) | −0.04 (<0.01) | 0.37 (0.31–0.39) | −0.05 (<0.001) | −0.000 (0.97) | −0.05 (<0.001) | −0.002 (0.88) | 0.34 (0.29–0.38) | −0.07 (<0.001) | −0.02 (0.054) | −0.06 (<0.001) | −0.01 (0.39) |

| VSD (SCP) | 13.27 (12.08–13.94) | 12.80 (11.33–13.79) | −0.39 (0.51) | −0.39 (0.50) | 12.18 (9.78–13.08) | −1.87 (<0.001) | −1.48 (0.01) | −1.84 (<0.001) | −1.45 (0.01) | 11.90 (10.10–12.67) | −1.75 (<0.001) | 0.12 (0.79) | −1.62 (0.001) | 0.22 (0.62) | 10.52 (8.91–11.85) | −2.85 (<0.001) | −1.10 (0.004) | −2.37 (<0.001) | −0.74 (0.14) |

| VSD (DCP) | 8.31 (6.45–9.90) | 7.38 (5.93–9.25) | −0.31 (0.65) | −0.32 (0.65) | 6.16 (3.55–8.18) | −1.83 (0.001) | −1.52 (0.02) | −1.82 (0.001) | −1.50 (0.02) | 5.53 (3.61–7.80) | −2.04 (<0.001) | −0.21 (0.68) | −2.00 (<0.001) | −0.18 (0.73) | 4.68 (3.33–6.60) | −2.71 (<0.001) | −0.67 (0.14) | −2.46 (<0.001) | −0.46 (0.43) |

| VSD (Retina) | 14.56 (13.42–15.33) | 14.30 (12.88–15.20) | −0.32 (0.62) | −0.32 (0.61) | 13.33 (11.09–14.26) | −2.09 (<0.001) | −1.77 (0.003) | −2.02 (<0.001) | −1.70 (0.004) | 12.96 (10.75–13.79) | −2.10 (<0.001) | −0.01 (0.98) | −1.91 (<0.001) | 0.11 (0.81) | 11.77 (10.03–13.11) | −2.91 (<0.001) | −0.81 (0.051) | −2.44 (<0.001) | −0.53 (0.33) |

| FAZ Area | 0.27 (0.20–0.35) | 0.28 (0.20–0.41) | 0.07 (0.86) | 0.07 (0.86) | 0.39 (0.26–0.54) | 0.59 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.20) | 0.59 (0.08) | 0.51 (0.20) | 0.32 (0.20–0.47) | 0.24 (0.47) | −0.35 (0.26) | 0.23 (0.50) | −0.36 (0.25) | 0.34 (0.21–0.52) | 0.58 (0.06) | 0.33 (0.23) | 0.46 (0.26) | 0.23 (0.54) |

| FAZ Perimeter | 2.25 (1.70–2.59) | 2.44 (1.91–3.00) | 0.38 (0.76) | 0.39 (0.75) | 2.83 (2.15–3.45) | 2.23 (0.03) | 1.85 (0.12) | 2.23 (0.03) | 1.84 (0.12) | 2.61 (1.99–3.54) | 1.22 (0.22) | −1.01 (0.27) | 1.18 (0.24) | −1.05 (0.26) | 2.59 (1.99–3.54) | 1.90 (0.04) | 0.68 (0.40) | 1.90 (0.12) | 0.72 (0.51) |

| FAZ Circularity | 0.68 (0.63–0.72) | 0.64 (0.55–0.74) | −0.04 (0.34) | −0.04 (0.31) | 0.61 (0.52–0.69) | −0.10 (0.001) | −0.06 (0.09) | −0.10 (0.001) | −0.06 (0.09) | 0.53 (0.41–0.66) | −0.13 (<0.001) | −0.04 (0.14) | −0.13 (<0.001) | −0.04 (0.18) | 0.59 (0.48–0.65) | −0.11 (<0.001) | 0.02 (0.37) | −0.14 (<0.001) | −0.01 (0.74) |

| NPA, Superficial slab | 0.20 (0.04–0.40) | 0.26 (0.12–0.74) | 1.47 (0.54) | 1.37 (0.56) | 5.41 (2.64–10.45) | 6.79 (0.001) | 5.32 (0.02) | 6.64 (0.001) | 5.27 (0.02) | 9.88 (5.61–18.04) | 12.92 (<0.001) | 6.12 (0.002) | 12.21 (<0.001) | 5.57 (0.002) | 17.15 (11.37–28.93) | 20.43 (<0.001) | 7.53 (<0.001) | 15.28 (<0.001) | 3.07 (0.13) |

Values in bold are statistically significant (P < 0.05). DCP = deep capillary plexus; DR = diabetic retinopathy; FAZ = foveal avascular zone; IQR = interquartile range; NPA = nonperfusion area; NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy; SCP = superficial capillary plexus; VD = vessel density; VSD = vessel skeletonized density. Therapeutic interventions are prior history of focal laser, prior history of panretinal photocoagulation, prior history of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections received, and prior history of pars plana vitrectomy.

Figure 4.

Boxplots of quantitative vascular metrics measured on wider field (WF) swept-source OCT angiography (SS-OCTA) (A), vessel density (VD) (B), foveal avascular zone (FAZ) area, mm2; FAZ perimeter, mm; and FAZ circularity (C) vessel skeleton density (VSD), mm-1(D) nonperfusion area (NPA) (12 × 12), mm2. 6 × 6 = 6 × 6 mm angiogram size; 12 × 12 = 12 × 12 mm angiogram size. DCP = deep capillary plexus; DR = diabetic retinopathy; NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy; SCP = superficial capillary plexus. ∗P < 0.05 on mixed-effects multiple linear regression analyses, controlling for age.

Vessel Skeletonized Density

When comparing DR with controls, we observed a similar declining trend in the SCP, DCP, and full-thickness retina VSD for both angiograms, but no significant difference between no DR and controls (Table 3, Fig 4c). On the preceding stage analysis, mild NPDR had significant reduction in the SCP (6 × 6: ß = −0.93, P = 0.03; 12 × 12: ß = −1.48, P = 0.01), DCP (6 × 6: ß = −1.98, P = 0.01; 12 × 12: ß = −1.48, P = 0.01), and full-thickness retina (6 × 6: ß = −0.82, P = 0.04; 12 × 12: ß = −1.77, P = 0.003). Likewise, the moderate-severe NPDR group had a significant reduction in 6 × 6 mm SCP (ß = −1.03, P = 0.004) and the full-thickness retina (ß = −1.09, P = 0.001). The PDR group exhibited a reduction in 6 × 6 mm SCP (ß = −1.04, P = 0.001) and the full-thickness retina (ß = −0.94, P = 0.001), and 12 × 12 mm SCP (ß = −1.10, P = 0.004), with the full-thickness retina slab just barely below the level of significance (ß = −0.81, P = 0.051). While controlling for the treatment history, we observed an analogous decline, except loss of significance in decline in PDR versus moderate-severe NPDR for SCP VSD on 12 × 12 mm angiograms.

FAZ Parameters

On 6 × 6 mm angiograms, PDR eyes had significantly increased FAZ area (ß = 0.21, P < 0.001), perimeter (ß = 1.14, P < 0.001), and decreased circularity (ß = −0.12, P < 0.001) compared with the controls (Table 3, Fig 4b). Likewise, the moderate-severe NPDR group had more irregular FAZ relative to controls (ß = −0.08, P = 0.004). On 12 × 12 mm angiograms, the FAZ area was similar in the DR groups and controls. We observed increased FAZ perimeter for mild NPDR (ß = 2.23, P = 0.03) and PDR (ß = 1.90, P = 0.04) versus controls. There was a decreased FAZ circularity among all DR groups relative to controls. Compared with the preceding stage, only PDR eyes had significant changes on 6 × 6 mm angiograms (area ß = 0.13, P = 0.02; perimeter ß = 0.68, P = 0.01 and circularity ß = −0.05, P = 0.03). Additionally, controlling for prior treatment, we observed no significant difference in FAZ area. The remaining results were similar except for loss of significance when comparing PDR with moderate-severe NPDR for FAZ perimeter on both angiograms and FAZ circularity on 6 × 6 mm angiograms.

Nonperfusion Areas

Adjusting for age, mild NPDR (ß = 6.79, P = 0.001), moderate-severe NPDR (ß = 12.92, P < 0.001), and PDR (ß = 20.43, P < 0.001) eyes had significantly more NPA measured on 12 × 12 mm angiograms relative to control eyes (Table 3, Fig 4d) as well as to the previous DR stage (mild NPDR: ß = 5.32, P = 0.02; moderate-severe NPDR: ß = 6.12, P = 0.002; PDR: ß = 7.53, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference between controls and diabetic patients with no DR (ß = 1.47, P = 0.54). The results retained their statistical significance when simultaneously controlling for previous therapeutic interventions, except the PDR eyes lost the significance compared with moderate-severe NPDR eyes (ß = 3.07, P = 0.13).

Effect of Diabetic Macular Edema

In our cohort, 21 eyes with mild NPDR (23.9%), 71 eyes with moderate-severe NPDR (73.2%), and 91 eyes with PDR (54.2%) had DME (Table 2). Adjusting for age, among the mild NPDR group, we observed eyes with DME having significantly reduced VD (β = −0.04, P = 0.04) and VSD (β = −2.14, P = 0.04) in DCP and FAZ circularity (β = −0.10, P = 0.01) on 6 × 6 mm angiograms (Table 4). Alternatively, they had reduced VSD in SCP (β = −1.25, P = 0.048) and the full-thickness retina (β = −1.92, P = 0.01) on 12 × 12 mm angiograms. Among the moderate-severe NPDR group, eyes with DME were found to have significantly increased VD (β = 0.03, P = 0.02) and VSD (β = 1.32, P = 0.01) in SCP, VD (β = 0.02, P = 0.03), and VSD (β = 1.07, P = 0.03) in the full-thickness retina, and significantly decreased FAZ area (β = −0.19, P = 0.047) on 6 × 6 mm angiograms. There was no difference observed for PDR eyes with and without DME. We noted similar results when controlling for prior treatments, except the significance in decreased SCP VSD among mild NPDR eyes and FAZ area among moderate-severe NPDR eyes.

Table 4.

Results of Quantitative Analyses of Eye with and without Diabetic Macular Edema within the Same Study Group Using Mixed Effects Multiple Linear Regression with Post Hoc Tukey’s Honest Significant Differences Test, Adjusting for Age (Model A) and Age Along with Prior Therapeutic Interventions (Model B)

| Angiogram | Study Parameter | Presence of DME (Ref: DME absent) | Model A |

Model B |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P Value | β | P Value | |||

| 6 × 6 mm | VD (SCP) | Mild NPDR | −0.02 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||

| PDR | 0.004 | 0.64 | 0.002 | 0.83 | ||

| VD (DCP) | Mild NPDR | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.03 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.18 | ||

| PDR | −0.001 | 0.92 | −0.003 | 0.80 | ||

| VD (Retina) | Mild NPDR | −0.02 | 0.18 | −0.02 | 0.12 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | ||

| PDR | −0.002 | 0.68 | −0.005 | 0.54 | ||

| VSD (SCP) | Mild NPDR | −0.80 | 0.14 | −0.99 | 0.09 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 1.32 | 0.01 | 1.25 | 0.02 | ||

| PDR | 0.06 | 0.86 | −0.01 | 0.97 | ||

| VSD (DCP) | Mild NPDR | −2.14 | 0.04 | −2.29 | 0.03 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 1.30 | 0.17 | 1.34 | 0.17 | ||

| PDR | −0.10 | 0.88 | −0.20 | 0.77 | ||

| VSD (Retina) | Mild NPDR | −0.72 | 0.15 | −0.88 | >0.99 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 1.07 | 0.03 | 1.02 | 0.046 | ||

| PDR | −0.28 | 0.39 | −0.35 | 0.32 | ||

| FAZ Area | Mild NPDR | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.18 | 0.71 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | −0.19 | 0.047 | −0.56 | 0.22 | ||

| PDR | −0.08 | 0.21 | −0.23 | 0.47 | ||

| FAZ Perimeter | Mild NPDR | 0.06 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 0.75 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | −0.61 | 0.17 | −0.18 | 0.07 | ||

| PDR | −0.30 | 0.30 | −0.06 | 0.40 | ||

| FAZ Circularity | Mild NPDR | −0.10 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.001 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 0.02 | 0.66 | 0.02 | 0.70 | ||

| PDR | −0.03 | 0.27 | −0.03 | 0.26 | ||

| 12 × 12 mm | VD (SCP) | Mild NPDR | −0.002 | 0.19 | −0.03 | 0.18 |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | ||

| PDR | −0.001 | 0.27 | −0.01 | 0.31 | ||

| VD (DCP) | Mild NPDR | −0.001 | 0.43 | −0.01 | 0.53 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 0.002 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.20 | ||

| PDR | −0.001 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.58 | ||

| VD (Retina) | Mild NPDR | −0.03 | 0.16 | −0.03 | 0.18 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.08 | ||

| PDR | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.18 | ||

| VSD (SCP) | Mild NPDR | −1.25 | 0.048 | −1.31 | 0.057 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 1.25 | 0.051 | 1.30 | 0.056 | ||

| PDR | −0.55 | 0.22 | −0.52 | 0.29 | ||

| VSD (DCP) | Mild NPDR | −0.11 | 0.88 | −0.06 | 0.94 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 0.87 | 0.25 | 0.97 | 0.22 | ||

| PDR | −0.45 | 0.40 | −0.34 | 0.55 | ||

| VSD (Retina) | Mild NPDR | −1.92 | 0.01 | −1.91 | 0.01 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 1.28 | 0.06 | 1.41 | 0.058 | ||

| PDR | −0.81 | 0.10 | −0.69 | 0.20 | ||

| FAZ Area | Mild NPDR | −0.35 | 0.46 | −1.14 | 0.47 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | −0.46 | 0.34 | −2.04 | 0.19 | ||

| PDR | 0.06 | 0.85 | −0.08 | 0.94 | ||

| FAZ Perimeter | Mild NPDR | −0.99 | 0.48 | −0.42 | 0.44 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | −1.79 | 0.20 | −0.53 | 0.33 | ||

| PDR | 0.28 | 0.78 | −0.03 | 0.94 | ||

| FAZ Circularity | Mild NPDR | −0.02 | 0.57 | −0.03 | 0.51 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.24 | ||

| PDR | −0.02 | 0.46 | −0.002 | 0.96 | ||

| Nonperfusion area | Mild NPDR | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.41 | 0.89 | |

| Moderate-severe NPDR | −0.68 | 0.79 | −0.74 | 0.79 | ||

| PDR | 2.27 | 0.21 | 3.08 | 0.13 | ||

Values in bold are statistically significant (P < 0.05). DCP = deep capillary plexus; DME = diabetic macular edema; FAZ = foveal avascular zone; NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy; SCP = superficial capillary plexus; VD = vessel density; VSD = vessel skeletonized density. Therapeutic interventions include prior history of focal laser, prior history of panretinal photocoagulation, prior history of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections received, and prior history of pars plana vitrectomy.

Best-Corrected Visual Acuity

The median Snellen’s BCVA among control eyes was 20/20, 20/20-1 in no DR, 20/20-2 in mild NPDR, 20/25-1 in moderate-severe NPDR, and 20/32-1 in PDR (Table 2). We used multivariate mixed effects multiple linear regression models controlling for age, DR grading, and presence of DME to assess for the correlation between the study parameters and logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) (Table S1). On 6 × 6 mm angiograms, there was a significant negative correlation between logMAR and VD (SCP: ß = −0.87, P < 0.001; DCP: ß = −0.31, P = 0.01; retina: ß = −0.72, P = 0.001), VSD (SCP: ß = −0.02, P < 0.001; DCP: ß = −0.01, P = 0.003; retina: ß = −0.02, P = 0.001) and FAZ circularity (ß = −0.21, P = 0.001), whereas there was a significant positive correlation with FAZ area (ß = 0.09, P < 0.001) and perimeter (ß = 0.02, P < 0.001). On 12 × 12 mm angiograms, there was a similar significant correlation between logMAR and VD (SCP: ß = −0.60, P < 0.001; DCP: ß = −0.37, P = 0.02; retina: ß = −0.42, P = 0.01), VSD (SCP: ß = −0.02, P < 0.001; retina: ß = −0.02, P = 0.001), FAZ circularity (ß = −0.17, P = 0.02), FAZ area (ß = 0.09, P < 0.001), and NPA (ß = 0.004, P = 0.002), except VSD (DCP: ß = −0.01, P = 0.055) and FAZ perimeter (ß = 0.004, P = 0.052).

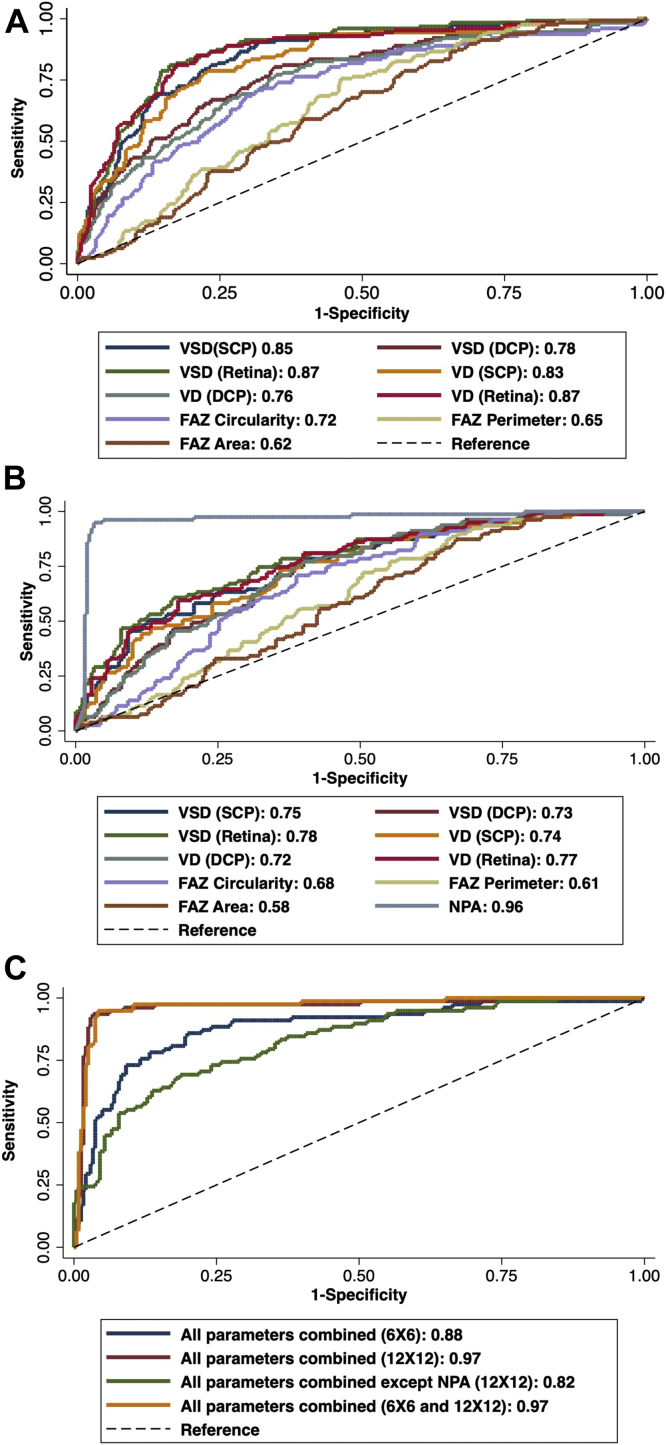

ROC Analysis

On ROC analysis of individual quantitative OCTA metrics in 6 × 6 mm angiograms, VSD (AUC, 0.87) and VD (AUC, 0.87) of the full-thickness retina had the highest predictive accuracy for presence of DR (Table 5, Fig 5a). On 12 × 12 mm angiograms, NPA had the highest accuracy (AUC, 0.96), followed by the full-thickness retina VSD (AUC, 0.78) and VD (AUC, 0.77) (Fig 5b). By using a logistic regression model, combined ROC analysis was performed for all metrics on 6 × 6 mm, 12 × 12 mm, 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm combined, and 12 × 12 mm without NPA (Fig 5c). Combined metrics on both angiograms (AUC, 0.97) and 12 × 12 mm (AUC, 0.97) had the highest diagnostic accuracy, followed by all parameters on 6 × 6 mm (AUC, 0.88) and 12 × 12 mm metrics excluding NPA (AUC, 0.82).

Table 5.

Area Under the Receiver Operator Curve Analyses Comparing the Accuracy of Each Quantitative Metric and Angiogram for Predicting the Presence of DR and Between Its Different Stages

| Study Parameter | Presence of DR vs. Absence of DR | No DR vs. Controls | Mild NPDR |

Moderate-Severe NPDR |

PDR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. Controls | vs. No DR | vs. Controls | vs. Mild NPDR | vs. Controls | vs. Moderate-severe NPDR | |||

| 6 × 6 mm, AUC (95% CI) | ||||||||

| VD (SCP) | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | 0.54 (0.43–0.64) | 0.74 (0.67–0.82) | 0.69 (0.60–0.78) | 0.86 (0.80–0.91) | 0.62 (0.54–0.70) | 0.92 (0.89–0.96) | 0.62 (0.56–0.70) |

| VD (DCP) | 0.76 (0.71–0.81) | 0.54 (0.43–0.65) | 0.72 (0.64–0.80) | 0.66 (0.56–0.76) | 0.78 (0.71–0.85) | 0.56 (0.47–0.64) | 0.82 (0.76–0.88) | 0.56 (0.49–0.64) |

| VD (Retina) | 0.87 (0.83–0.90) | 0.56 (0.46–0.67) | 0.76 (0.69–0.84) | 0.71 (0.62–0.80) | 0.90 (0.86–0.95) | 0.65 (0.57–0.73) | 0.95 (0.92–0.98) | 0.63 (0.56–0.70) |

| VSD (SCP) | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | 0.53 (0.43–0.64) | 0.74 (0.66–0.82) | 0.69 (0.60–0.77) | 0.87 (0.82–0.92) | 0.65 (0.57–0.73) | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | 0.64 (0.57–0.71) |

| VSD (DCP) | 0.77 (0.72–0.82) | 0.54 (0.43–0.64) | 0.72 (0.64–0.80) | 0.67 (0.58–0.77) | 0.80 (0.73–0.86) | 0.57 (0.49–0.65) | 0.84 (0.79–0.90) | 0.57 (0.50–0.64) |

| VSD (Retina) | 0.87 (0.84–0.91) | 0.55 (0.45–0.66) | 0.75 (0.67–0.82) | 0.70 (0.61–0.79) | 0.90 (0.86–0.95) | 0.68 (0.60–0.76) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.65 (0.58–0.72) |

| FAZ area | 0.62 (0.57–0.67) | 0.55 (0.45–0.65) | 0.60 (0.52–0.69) | 0.55 (0.45–0.65) | 0.62 (0.54–0.71) | 0.61 (0.52–0.69) | 0.67 (0.60–0.74) | 0.56 (0.49–0.63) |

| FAZ perimeter | 0.65 (0.60–0.71) | 0.54 (0.43–0.64) | 0.61 (0.52–0.69) | 0.57 (0.48–0.70) | 0.66 (0.58–0.74) | 0.55 (0.47–0.63) | 0.71 (0.64–0.78) | 0.57 (0.49–0.64) |

| FAZ circularity | 0.72 (0.67–0.78) | 0.51 (0.40–0.61) | 0.64 (0.56–0.73) | 0.63 (0.54–0.73) | 0.75 (0.67–0.83) | 0.52 (0.43–0.60) | 0.77 (0.70–0.83) | 0.55 (0.48–0.63) |

| All parameters combined | 0.88 (0.84–0.93) | 0.62 (0.49–0.75) | 0.84 (0.76–0.91) | 0.70 (0.57–0.82) | 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | 0.71 (0.63–0.80) | 0.99 (0.98–1) | 0.71 (0.63–0.78) |

| 12 × 12 mm, AUC (95% CI) | ||||||||

| VD (SCP) | 0.74 (0.68–0.80) | 0.60 (0.47–0.74) | 0.72 (0.63–0.81) | 0.63 (0.52–0.75) | 0.74 (0.65–0.83) | 0.52 (0.43–0.62) | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) | 0.61 (0.52–0.70) |

| VD (DCP) | 0.72 (0.66–0.78) | 0.57 (0.43–0.71) | 0.71 (0.61–0.80) | 0.65 (0.53–0.76) | 0.73 (0.64–0.81) | 0.52 (0.43–0.62) | 0.80 (0.73–0.87) | 0.54 (0.45–0.63) |

| VD (Retina) | 0.77 (0.71–0.83) | 0.57 (0.43–0.70) | 0.73 (0.64–0.82) | 0.68 (0.57–0.80) | 0.77 (0.68–0.85) | 0.54 (0.44–0.63) | 0.86 (0.79–0.92) | 0.60 (0.51–0.69) |

| VSD (SCP) | 0.75 (0.69–0.81) | 0.58 (0.44–0.71) | 0.73 (0.64–0.82) | 0.65 (0.53–0.77) | 0.76 (0.68–0.85) | 0.53 (0.43–0.62) | 0.85 (0.79–0.92) | 0.61 (0.53–0.70) |

| VSD (DCP) | 0.73 (0.67–0.78) | 0.58 (0.44–0.71) | 0.70 (0.61–0.79) | 0.63 (0.52–0.75) | 0.73 (0.64–0.82) | 0.53 (0.44–0.63) | 0.80 (0.73–0.88) | 0.54 (0.45–0.60) |

| VSD (Retina) | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) | 0.56 (0.42–0.70) | 0.74 (0.65–0.83) | 0.69 (0.57–0.80) | 0.79 (0.71–0.87) | 0.51 (0.42–0.61) | 0.87 (0.82–0.93) | 0.60 (0.51–0.69) |

| FAZ area | 0.58 (0.52–0.65) | 0.66 (0.54–0.79) | 0.71 (0.61–0.80) | 0.59 (0.47–0.70) | 0.58 (0.48–0.68) | 0.61 (0.51–0.70) | 0.62 (0.53–0.71) | 0.54 (0.45–0.62) |

| FAZ perimeter | 0.61 (0.55–0.65) | 0.69 (0.57–0.81) | 0.72 (0.63–0.81) | 0.57 (0.45–0.69) | 0.64 (0.54–0.73) | 0.56 (0.46–0.65) | 0.66 (0.57–0.75) | 0.52 (0.43–0.61) |

| FAZ circularity | 0.68 (0.62–0.74) | 0.63 (0.49–0.77) | 0.66 (0.57–0.76) | 0.54 (0.43–0.67) | 0.58 (0.48–0.68) | 0.57 (0.48–0.67) | 0.74 (0.67–0.82) | 0.54 (0.45–0.62) |

| NPA | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 0.57 (0.43–0.70) | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 0.90 (0.82–0.97) | 1 | 0.71 (0.62–0.79) | 1 | 0.67 (0.61–0.77) |

| All parameters combined | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.81 (0.72–0.91) | 0.98 (0.96–1) | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 1 | 0.84 (0.77–0.90) | 1 | 0.74 (0.67–0.81) |

| All parameters combined except NPA | 0.82 (0.77–0.88) | 0.76 (0.65–0.87) | 0.82 (0.75–0.90) | 0.72 (0.61–0.84) | 0.94 (0.89–0.97) | 0.75 (0.67–0.83) | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | 0.71 (0.63–0.79) |

| 6 × 6 mmand 12 × 12 mm, AUC (95% CI) | ||||||||

| All parameters | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.88 (0.81–0.95) | 0.99 (0.98–1) | 0.93 (0.86–0.99) | 1 | 0.88 (0.82–0.93) | 1 | 0.83 (0.77–0.89) |

The AUC values >0.8 are highlighted in bold. AUC = area under the curve; CI = confidence interval; DCP = deep capillary plexus; DR = diabetic retinopathy; FAZ = foveal avascular zone; NPA = nonperfusion area; NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy; SCP = superficial capillary plexus; VD = vessel density; VSD = vessel skeletonized density.

Figure 5.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses comparing the accuracy of each quantitative metric for predicting the presence of diabetic retinopathy (DR) for (A) on 6 × 6 mm angiogram size and (B) 12 × 12 mm angiogram size. C, Combined ROC analyses comparing the accuracy of all quantitative metrics on 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm angiograms for predicting the presence of DR. The numbers signify the area under the curve (AUC) value. The dashed line represents the trade-off resulting from random chance. DCP = deep capillary plexus; FAZ = foveal avascular zone; NPA = nonperfusion area; SCP = superficial capillary plexus; VD = vessel density; VSD = vessel skeletonized density. 6 × 6 and 12 × 12 refer to the angiogram sizes in mm × mm.

Likewise, ROC analysis was performed to compare their diagnostic accuracy between consecutive stages of DR. Comparing controls with no DR, all the individual metrics on either of the angiogram sizes performed poorly, but the consolidated metrics on both angiograms had the highest accuracy of differentiating them (AUC, 0.88) followed by all parameters combined on 12 × 12 mm angiograms (AUC, 0.81). Comparing no DR with the mild NPDR group, VD (AUC, 0.71) and VSD (AUC, 0.70) of 6 × 6 mm full-thickness retina had the highest diagnostic accuracy. On 12 × 12 mm angiograms, NPA had the highest accuracy (AUC, 0.90). Combined metrics on both angiograms had the highest accuracy of differentiating the groups (AUC, 0.93) followed by consolidated 12 × 12 mm metrics (AUC, 0.92). Comparing mild NPDR with moderate-severe NPDR groups, individual metrics on both angiograms had similar poor accuracy, but NPA on 12 × 12 mm had the highest accuracy (AUC, 0.71). Integrated metrics on both angiograms had the highest predictive accuracy (AUC, 0.88). Comparing moderate-severe NPDR with PDR groups, individual metrics had similar poor diagnostic accuracy. Consolidated metrics on both angiograms had the highest accuracy of differentiating the groups (AUC, 0.83).

Discussion

Our study provides a thorough evaluation of the most commonly measured quantitative OCTA metrics and NPA, on the largest cohort to date, using both 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm angiograms on WF SS-OCTA to assess the retinal vasculature changes in DR. On ROC analyses for assessment of the accuracy of individual OCTA metrics, NPA was the best biomarker for diagnosis of DR. Vessel density and VSD performed superiorly on 6 × 6 mm relative to 12 × 12 mm angiograms, whereas FAZ parameters were poor predictors irrespective of angiogram FOV. Cumulative metrics measured on both 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm FOV had superior accuracy in predicting the presence of DR and even its grading. In light of these findings along with the already known effect of chronic hyperglycemia leading to vascular endothelial dysfunction and retinal ischemia, WF SS-OCTA metrics incorporating more peripheral DR changes like NPA can emerge as reliable imaging biomarkers and potential adjuncts for DR staging, management, prognostication, and even post-treatment surveillance.

Our work proposes NPA quantified on WF angiograms (superficial slab) as being the most accurate diagnostic metric for both DR diagnosis and staging. By adjusting for age, we observed a consistent increase in NPA in all DR stages relative to controls as well as the preceding DR stage. This increase remained significant when additionally controlling for prior interventions such as focal laser, panretinal photocoagulation, anti-VEGF, and pars plana vitrectomy for all comparisons, except for PDR versus moderate-severe NPDR. This may be due to the exclusion of the most advanced PDR eyes because we had a BCVA cutoff of 20/200. On combined ROC analysis for all metrics on both angiograms, the addition of NPA provided superior AUC reaching good (0.81–0.90) to excellent (>0.90) accuracy. Similar to our results, the study by Tan et al16 found a significant increase in NPA in NPDR eyes relative to controls, mild NPDR versus no DR, and moderate-severe NPDR versus mild NPDR. However, eyes with PDR were not included, and AUC for NPA to detect DR was not reported.16 In 2021, Kim et al22 evaluated NPA in squares of size 10 × 10 mm, 6 × 6 mm, and 3 × 3 mm cropped from a single 12 × 12 mm OCTA image and reported higher AUC for NPA, with NPA from 10 × 10 mm having the best accuracy followed by 6 × 6 mm and then 3 × 3 mm squares. But the different grades of DR from wide range of the clinical spectrum were grouped together for binarizing the outcome to assess ROC for the OCTA metrics, which might make clinical interpretation difficult.22 Our study examines NPA quantified on 12 × 12 mm angiograms for assessing its prediction accuracy, as well as consolidating it with other OCTA quantitative metrics to diagnose and stage DR, in a large cohort.

Apart from NPA, we also studied quantitative OCTA such as vessel metrics and FAZ parameters among healthy patients and diabetic patients. We observed no difference between controls and no DR in any study parameter, on any angiogram size, which is similar to previous literature on vessel15,16 and FAZ metrics.27, 28, 29 In our study, the mild NPDR eyes showed a reduction in all vessel metrics in all layers on both the angiograms relative to controls and the no DR group. Likewise, the moderate-severe NPDR and PDR eyes had decreased VD and VSD in all layers on both sized angiograms relative to controls and a statistically significant reduction in SCP and full-thickness retina on 6 × 6 mm angiograms compared with mild NPDR and moderate-severe NPDR, respectively. The PDR eyes additionally had decreased VD and VSD in SCP on 12 × 12 mm angiograms, which lost statistical significance when adjusting for history of prior treatment. Our results are consistent with previous literature.8,13,14,27,30, 31, 32, 33 Additionally, we observe a significant decline in vessel metrics of both SCP and DCP in early-stage DR, whereas only SCP is significantly reduced in more advanced stage DR compared with the previous stage. Because the latter group showed a reduction in vessels of both SCP and DCP relative to controls but not to previous stages, we postulate that with the onset of clinical signs of DR in the mild NPDR stage, the loss of DCP VD/VSD is already established, and increasing ischemia continues to then decrease the SCP VD/VSD further with DR progression. The literature is equivocal on whether SCP or DCP is correlated with progression of DR. Ong et al33 showed that on pairwise analysis, VD changes in DCP were not evident between any consecutive stages but were present between study groups separated by 2 or more stages. On the contrary, VD decline in SCP occurred in early (mild NPDR vs. no DR) and late NPDR (severe NPDR vs. moderate NPDR) progression. It has been shown that the DCP is more sensitive to ischemia because of its presence in the watershed zone of oxygen supply,34 and that DCP may show reduced VD in no DR eyes in patients with type 1 DM.35 Studies using OCTA prove that retinal capillary units terminate in the DCP, where blood flows from the SCP and drains into deep venules via DCP, thus slowing of retinal blood flow and possibly preferentially affecting DCP perfusion.10,36,37 An alternative hypothesis is supported by the prior work of Nesper et al27 reporting steeper decline in adjusted flow index, a surrogate marker for flow index, in DCP with increasing DR severity. Sun et al38 established in their prospective study that reduced VD in DCP and increased FAZ area at the baseline was predictive of worsening of DR severity.

We also analyzed the effect of DME on quantitative metrics within every stage of DR, adjusting for the effect of age and prior therapeutic interventions. In mild NPDR with DME, there was a decrease in vessel metrics in the DCP and FAZ circularity on 6 × 6 mm, and decreased VSD in the full-thickness retina on 12 × 12 mm compared with those without DME. On the contrary, in moderate-severe NPDR with DME, vessel metrics in the SCP and full-thickness retina were increased. The effect of DME on vessel metrics are still debated, with studies reporting mixed results. Hirano et al15 showed that VD was decreased in NPDR eyes with DME compared with non-DME counterparts in DCP on 3 × 3 mm angiograms. This was not observed for PDR eyes. Consistent with this, our results further differentiate among NPDR. It is believed that DME is said to occur as a result of a break in the inner blood retinal barrier or changes in DCP that may be involved in removal of interstitial fluid from the retina.37, 39, 40 Alternatively Sun et al38 conducted a prospective study to evaluate OCTA metrics for risk of DME development, which was found to be associated with reduced VD in SCP but not DCP. This also builds on our previous result where we see significant progressive SCP vessel reduction with increasing severity, but progressive DCP vessel decline is significant only in early DR stages.

Our results showed that the quantitative metrics on 6 × 6 mm had higher accuracy of diagnosing DR compared with 12 × 12 mm angiograms on ROC analyses. This is consistent with previous studies on VD and FAZ metrics.8,11,15 This universal difference in diagnostic accuracy is due to the greater image resolution of the foveal area on narrow FOV angiograms, increased proportion of FAZ area relative to the angiogram area, or the earlier involvement of microvasculature around the macula in DR.8 This work showed that the combined use of all quantitative metrics on 12 × 12 mm angiograms had a greater accuracy in assessing DR severity compared with 6 × 6 mm. The difference in predictive accuracy was due to the evaluation of NPA on 12 × 12 mm, which was evident, when excluding NPA from the 12 × 12 mm metrics, that lead to decreased accuracy compared with 6 × 6 mm angiograms. We also noted the best results with consolidated metrics on both angiograms to diagnose and stage DR. This could be due to the combined advantages of higher resolution of macular area on 6 × 6 mm angiograms and thus better sensitivity of vessel and FAZ metrics in picking up central pathology, as well as the wide FOV helping us quantify NPA and incorporating mid-peripheral pathological changes in DR. Alam et al31 used a cumulative model to test the combined accuracy of quantitative metrics including FAZ area, FAZ circularity, vessel tortuosity, vessel perimeter index, VD, and vessel caliber in differentiating control versus NPDR and control versus mild NPDR in the 6 × 6 mm angiogram size. The combined AUC was higher than any of the individual metrics. These results showcase the combined efficacy of the metrics in predicting DR severity that can be missed on individual metrics.

Although there have been a few prior studies demonstrating the advantage of OCTA in predicting DR and its severity, there are some limitations in their study designs. Most of the studies were conducted in relatively small patient populations. Many also excluded eyes with DME or prior therapeutic intervention, limiting their ability to be applied broadly to clinic settings where both will be present. Most studies also evaluated a narrower FOV with 3 × 3 mm angiograms. In those few studies that did look at evaluated 12 × 12 mm angiograms, only 2 evaluated NPA in smaller cohorts.16,22 Although age is known to be associated with a chronic decline in vessel metrics, few studies controlled for age. Patients who underwent photocoagulation were excluded or not controlled for in their respective analysis. We adjusted for all these parameters in our analyses. In most studies, patients were grouped into a bucket term of “DR” or “NPDR” without any subgroup analysis that would reduce the granularity of study results. Likewise, for ROC analysis, when performed, patients were usually dichotomized into 2 broad categories, “DR” and “no DR,” which could lead to a less precise result. Despite individual ROC analysis for various quantitative metrics, except one, none have evaluated the cumulative accuracy of various metrics in predicting the severity of DR. The studies had numerous different methods of segmentation and manual image analysis. To overcome this, our study uses the ARI network for standardized image analysis, and these values can be used as a basis to build on the normative datasets for future incorporation of automatic vessel metrics result maps after imaging, with continued advancement of technology.

Study Limitations

This study does have a few notable limitations. As it is only a cross-sectional study with imaging captured at a single time point, a follow-up study with longitudinal data from patients with DR would be even more helpful for determining the role of SS-OCTA in predicting DR progression. The inclusion criteria included only patients with visual acuity better than 20/200, which may skew the results for those more advanced cases with severe vision loss. The DR grading was determined by clinical exam, which might have induced some error and bias. Although we strived to recruit similar groups by demographics, our controls consisted of a lower proportion of Hispanics and Blacks than our patients with DM, which could limit the applications in some clinical settings.

While the current DR grading systems rely solely on 30-degree CFP, there has been tremendous expansion of the available retinal imaging modalities, particularly UWF CFP, UWF FA, autofluorescence, and WF OCTA. Multimodal imaging has gained popularity for both clinical and research applications, prompting a natural call for an updated DR staging system and exploration of these new imaging tools.5 We have previously shown noninferiority of WF SS-OCTA to UWF FA in detecting the key lesions of DR, such as neovascularisation and NPA. We also demonstrated that a multimodal approach combining WF SS-OCTA with UWF CFP had identical detection rate to UWF FA for DR lesions.6

Conclusions

Our study further states the case for WF SS-OCTA as a versatile and critical imaging device for the diagnosis and severity classification of DR in the clinical practice. Although 12 × 12 mm is subject to more artifacts and has smaller resolution for the foveal area, it excels in predicting DR severity by improving the ability to identify NPAs. Indeed, NPAs quantify the amount of microvascular damage and retinal ischemia, and thus have the highest sensitivity to diagnose DR. We recommend a combination of 6 × 6 mm and 12 × 12 mm angiogram sizes for a patient diagnosed with DM, leveraging the advantages of both macular and extramacular angiograms for accurate diagnosis of DR and its prognostication resulting in early management of diabetic eye disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the staff for their help and assistance in research and patient recruitment from retina clinics at MEEI.

Manuscript no. XOPS-D-21-00133

Footnotes

Supplemental material available atwww.ophthalmologyscience.org.

Disclosure(s):

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures form.

The author(s) have made the following disclosure(s): D.E.: Consultant – Alcon, Allergan, Dutch Ophthalmic, Glaukos; Financial support – Alderya Therapeutics, Pykus Therapeutics, Neurotech Pharmaceuticals.

L.A.K.: Research support – National Eye Institute, CureVac AG; Financial support – Pykus Therapeutics.

D.M.W.: Patent – Massachusetts Eye and Ear.

J.W.M.: Consultant – Heidelberg Engineering, Sunovion, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, ONL Therapeutics; Patent and financial support – ONL, Valeant Pharmaceuticals/Massachusetts Eye and Ear; Financial support – Lowy Medical Research Institute, Ltd.

D.H.: Consultant – Allergan, Genentech, Omeicos Therapeutics; Financial support – National Eye Institute, Lions VisionGift, Commonwealth Grant, Lions International, Syneos LLC, Macular Society.

D.G.V.: Consultant – Valitor, Olix Pharmaceuticals; Financial support – National Eye Institute; Grants – National Institute of Health (grant nos. R01EY025362 and R21EY0203079), Research to Prevent Blindness, Loefflers Family Foundation, Yeatts Family Foundation, and Alcon Research Institute.

J.B.M.: Consultant – Alcon, Allergan, Carl Zeiss, Sunovion, Genentech and Topcon.

Financial Support: Lions International Fund (Grants 530125 and 530869). The funding organization had no role in design or conduct of this research.

Demetrios Vavvas, MD, PhD, an editor of this journal, was recused from the peer-review process of this article and had no access to information regarding its peer-review.

Presented at: the 44th Virtual Annual Macula Society meeting 2021, The Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Meeting 2021, the American Society of Retina Specialists Meeting 2021 and Macula 2022 Will's Eye Hospital. It has been awarded the National Eye Institute Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology travel grant.

HUMAN SUBJECTS: Human subjects were included in this study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Massachusetts Eye and Ear (2019P001863). Written detailed informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Our research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations.

No animal subjects were used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Garg, Cui, Moon, Li, Laíns, Eliott, Elze, Kim, Wu, Miller, Miller

Data collection: Garg, Le, Lu, Cui, Wai, Katz, Zhu, Husain, Vavvas, Miller

Analysis and interpretation: Garg, Uwakwe, Le, Lu, Wai, Laíns, Elze, Vavvas, Miller

Obtained funding: N/A

Overall responsibility: Garg, Uwakwe, Kim, Miller

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Saeedi P., Petersohn I., Salpea P., et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yau J.W.Y., Rogers S.L., Kawasaki R., et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:556–564. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silva P.S., Cavallerano J.D., Sun J.K., et al. Peripheral lesions identified by mydriatic ultrawide field imaging: distribution and potential impact on diabetic retinopathy severity. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2587–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva P.S., Cavallerano J.D., Sun J.K., et al. Nonmydriatic ultrawide field retinal imaging compared with dilated standard 7-field 35-mm photography and retinal specialist examination for evaluation of diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:549–559.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun J.K., Aiello L.P., Abràmoff M.D., et al. Updating the staging system for diabetic retinal disease. Ophthalmology. 2020;128:490–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui Y., Zhu Y., Wang J.C., et al. Comparison of widefield swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography with ultra-widefield colour fundus photography and fluorescein angiography for detection of lesions in diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316245. bjophthalmol-2020-316245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spaide R.F., Fujimoto J.G., Waheed N.K., et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018;64:1–55. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agemy S.A., Scripsema N.K., Shah C.M., et al. Retinal vascular perfusion density mapping using optical coherence tomography angiography in normals and diabetic retinopathy patients. Retina. 2015;35:2353–2363. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang T.S., Gao S.S., Liu L., et al. Automated quantification of capillary nonperfusion using optical coherence tomography angiography in diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:367–373. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.5658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupas B., Minvielle W., Bonnin S., et al. Association between vessel density and visual acuity in patients with diabetic retinopathy and poorly controlled type 1 diabetes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:721–728. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho J., Dans K., You Q., et al. Comparison of 3 mm × 3 mm versus 6 mm × 6 mm optical coherence tomography angiography scan sizes in the evaluation of non–proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2019;39:259–264. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samara W.A., Shahlaee A., Adam M.K., et al. Quantification of diabetic macular ischemia using optical coherence tomography angiography and its relationship with visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durbin M.K., An L., Shemonski N.D., et al. Quantification of retinal microvascular density in optical coherence tomographic angiography images in diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:370–376. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ting D.S.W., Tan G.S.W., Agrawal R., et al. Optical coherence tomographic angiography in type 2 diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:306–312. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.5877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirano T., Kitahara J., Toriyama Y., et al. Quantifying vascular density and morphology using different swept-source optical coherence tomography angiographic scan patterns in diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103:216–221. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-311942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan B., Chua J., Lin E., et al. Quantitative microvascular analysis with wide-field optical coherence tomography angiography in eyes with diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimizu K., Kobayashi Y., Muraoka K. Midperipheral fundus involvement in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:601–612. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(81)34983-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niki T., Muraoka K., Shimizu K. Distribution of capillary nonperfusion in early-stage diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1431–1439. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva P.S., Dela Cruz A.J., Ledesma M.G., et al. Diabetic retinopathy severity and peripheral lesions are associated with nonperfusion on ultrawide field angiography. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2465–2472. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawada O., Ichiyama Y., Obata S., et al. Comparison between wide-angle OCT angiography and ultra-wide field fluorescein angiography for detecting non-perfusion areas and retinal neovascularization in eyes with diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256:1275–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-3992-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Couturier A., Rey P.-A., Erginay A., et al. Widefield OCT-angiography and fluorescein angiography assessments of nonperfusion in diabetic retinopathy and edema treated with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:1685–1694. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim K., In You J., Park J.R., et al. Quantification of retinal microvascular parameters by severity of diabetic retinopathy using wide-field swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259:2103–2111. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05099-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson C.P., Ferris F.L., Klein R.E., et al. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1677–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Sheikh M., Falavarjani K.G., Tepelus T.C., Sadda S.R. Quantitative comparison of swept-source and spectral-domain OCT angiography in healthy eyes. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retin. 2017;48:385–391. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20170428-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Pretto L.R., Moult E.M., Alibhai A.Y., et al. Controlling for artifacts in widefield optical coherence tomography angiography measurements of non-perfusion area. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43958-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nesper P.L., Roberts P.K., Onishi A.C., et al. Quantifying microvascular abnormalities with increasing severity of diabetic retinopathy using optical coherence tomography angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:BIO307–BIO315. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-21787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di G., Weihong Y., Xiao Z., et al. A morphological study of the foveal avascular zone in patients with diabetes mellitus using optical coherence tomography angiography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:873–879. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carnevali A., Sacconi R., Corbelli E., et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography analysis of retinal vascular plexuses and choriocapillaris in patients with type 1 diabetes without diabetic retinopathy. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54:695–702. doi: 10.1007/s00592-017-0996-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Binotti W.W., Romano A.C. Projection-resolved optical coherence tomography angiography parameters to determine severity in diabetic retinopathy. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:1321–1327. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alam M., Zhang Y., Lim J.I., et al. Quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography features for objective classification and staging of diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2020;40:322–332. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhanushali D., Anegondi N., Gadde S.G.K., et al. Linking retinal microvasculature features with severity of diabetic retinopathy using optical coherence tomography angiography. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:519–525. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ong J.X., Kwan C.C., Cicinelli M.V., Fawzi A.A. Superficial capillary perfusion on optical coherence tomography angiography differentiates moderate and severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. PLoS One. 2020;15:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu S., Pang C.E., Gong Y., et al. The spectrum of superficial and deep capillary ischemia in retinal artery occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:53–63.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carnevali A., Sacconi R., Corbelli E., et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography analysis of retinal vascular plexuses and choriocapillaris in patients with type 1 diabetes without diabetic retinopathy. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54:695–702. doi: 10.1007/s00592-017-0996-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonnin S., Mané V., Couturier A., et al. New insight into the macular deep vascular plexus imaged by optical coherence tomography angiography. Retina. 2015;35:2347–2352. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garrity S.T., Paques M., Gaudric A., et al. Considerations in the understanding of venous outflow in the retinal capillary plexus. Retina. 2017;37:1809–1812. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Z., Tang F., Wong R., et al. OCT angiography metrics predict progression of diabetic retinopathy and development of diabetic macular edema: a prospective study. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:1675–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spaide R.F. Retinal vascular cystoid macular edema: review and new theory. Retina. 2016;36:1823–1842. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freund K.B., Sarraf D., Leong B.C.S., et al. Association of optical coherence tomography angiography of collaterals in retinal vein occlusion with major venous outflow through the deep vascular complex. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:1262–1270. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.