Abstract

This study explored the in vivo wound healing potential of Vitis vinifera seed extract using an excision wound model with focus on wound healing molecular targets including TGFBR1, VEGF, TNF-α, and IL-1β. The wound healing results revealed that V. vinifera seed extract enhanced wound closure rates (p < 0.001), elevated TGF-β and VEGF levels, and significantly downregulated TNF-α and IL-1β levels in comparison to the Mebo®-treated group. The phenotypical results were supported by biochemical and histopathological findings. Phytochemical investigation yielded a total of 36 compounds including twenty-seven compounds (1–27) identified from seed oil using GC-MS analysis, along with nine isolated compounds. Among the isolated compounds, one new benzofuran dimer (28) along with eight known ones (29–36) were identified. The structure of new compound was elucidated utilizing 1D/2D NMR, with HRESIMS analyses. Moreover, molecular docking experiments were performed to elucidate the molecular targets (TNF-α, TGFBR1, and IL-1β) of the observed wound healing activity. Additionally, the in vitro antioxidant activity of V. vinifera seed extract along with two isolated compounds (ursolic acid 34, and β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside 36) were explored. Our study highlights the potential of V. vinifera seed extract in wound repair uncovering the most probable mechanisms of action using in silico analysis.

Keywords: Vitis vinifera, benzofuran, wound healing, TNF-α, TGF-β, in silico

1. Introduction

Wounds are a significant global health issue that has serious commercial and social impacts on health institutes, patients, and caregivers [1]. Wounds are divided into physical, thermal, or chemical injuries that create an opening or crack in the skin’s integrity or modify the anatomical integrity of living tissues [2]. Wound healing is graded into the following phases: Inflammation, proliferation, extracellular matrix formation, and finally remodeling [3]. To develop new tissue, fibroblasts spread during the proliferative phase and secrete many growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and type I collagen [4]. Ethnomedicinal investigations have searched arduously for natural remedies for wound healing [4,5].

Vitis vinifera Linn. (F. Vitaceae) is a climber which is woody in nature and containing coiled climbing tendrils. It bears small, pale, tender flowers, which are modified to berry fruits that vary from green to various degrees of purple black [6,7,8]. V. vinifera fruits, commonly known as grape, were utilized in traditional medication since ancient times [8]. In Malatya, the fruit is helpful in forming blood [9]. While in Elazığ, it is used for treatment of anemia [10]. In Pakistan, it is commonly employed as carminatives [11]. The Tuscany area uses alcoholic drinks derived from grapes for the digestive system [12]. While Cyprus uses alcohol marinade as a liniment, poultice, and mouthwash [13].

Grape skin is a valuable source of unsaturated fatty acids, crude fibers, polyphenols proanthocyanidins (flavan-3-ol oligomers units including catechin/epicatechin), minerals, flavan-3-ols (catechins and proanthocyanidins), and resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene), which are valuable by-product for antioxidant and hygienic formation [14]. It has been reported that incorporation of its flour into wheat flour improved the nutritional properties of the bakery products [14]. Topical application of grape skin was reported to speed wound healing in mice, where it showed to increase the rate of wound shrinkage and hydroxyproline composition, and lower the epithelialization stage in the considered animals [15].

V. vinifera’s fruits are considered a major source of phenolic antioxidant compounds, including resveratrol, quercetin, catechins, epigallocatechin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, procyanidins, and anthocyanins [16]. Researchers reported that applying a high-resveratrol V. vinifera fruit extract to the wounds of mice accelerated wound healing, which might be due to the manipulation of redox-sensitive processes that promote dermal tissue repair [17]. V. vinifera’s seeds consist of polyphenolic compounds, such as (+)-catechin, (−)-epicatechin, flavanols, resveratrol, and proanthocyanidins [18], that have been established to exhibit powerful anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant, anti-diabetic, anti-platelet, anti-cholesterol, anti-aging, anti-microbial, and anti-tumour properties [18]. Researchers reported that the surface application of oil of grape seed has proved to stimulate wound healing in animals, especially mice, through enhancing the time of wound shrinkage, hydroxyproline matter, and reducing the epithelialization lifetime [19].

Despite the existence of studies describing the wound healing potential of V. vinifera seeds, and other related organs, very little is known regarding its mode of action in wound healing potential. Consequently, our study explores the in vivo wound healing efficacy of V. vinifera seed extract by excision wound model, focusing on important wound healing molecular targets including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), transforming growth factor-beta receptor type 1 kinase (TGFBR1), interleukin -1β (IL-1β), collagen type I, and VEGF. Additionally, a phytochemical investigation of seed extract and molecular docking of isolated compounds using TNF-α, TGFBR1 and IL-1β was performed to pinpoint the chemical molecules that contribute to the wound healing activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, Reagents, Chemicals, Spectral Analyses, Extraction, and Fractionation of V. vinifera Seeds

Plant material, chemicals, reagents, spectral analyses, extraction, and fractionation of V. vinifera seeds are discussed in detail in the Supplementary Materials (Materials and Methods section, pages S2).

2.2. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

H2O2 scavenging and SOD scavenging activity of V. vinifera seed crude extract were discussed in the Supplementary Materials in detail.

2.3. In Vivo Wound Healing Activity

Twenty-four albino rabbits (adult male New Zealand Dutch) were used. The wound healing potency of V. vinifera seed crude extract was assessed utilizing the excision wound model, which is discussed in detail in the Supplementary Materials with a histological study, gene expression analysis, and western blotting.

2.4. Preparation of the Fatty Acid Methyl Esters with GC-MS Analysis, Isolation, and Purification of Compounds

Methylation was done using concentrated sulfuric acid to obtain FAMEs. The analysis was carried out using GC-MS. While isolation and purification of compounds were carried out using different chromatographic techniques. The details are discussed in the section of Supplementary Materials.

2.5. Molecular Docking Studies

The details are discussed in the Supplementary Materials for the structures of all test compound drawings and the crystal structures of TNF-α, TGFBR1, and 1L-β1.

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Antioxidant Potential of V. vinifera Seed Extract

3.1.1. Hydrogen Peroxide Scavenging Power

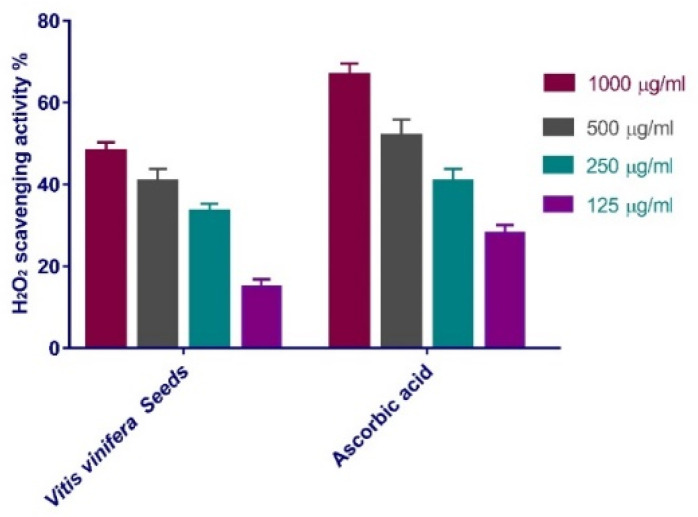

The antioxidant power of V. vinifera seed extract as a scavenger potential against hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was reported in this study. The maximal H2O2 radical scavenging activity of the seed extract of V. vinifera was 48.1% at 1000 µg/mL concentration, according to the data. V. vinifera seed extract suppressed the formation of hydrogen peroxide radicals in a dose-dependent mode, demonstrating a consistent antioxidant potential with IC50 of 175.8 μg/mL concentration (Figure 1), in comparison with standard (ascorbic acid, IC50 = 178.1 μg/mL).

Figure 1.

H2O2 radical scavenging activity of V. vinifera seed extract at variant concentrations (1000 µg/mL, 500 µg/mL, 250 µg/mL, and 125 µg/mL). Bars illustrate mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant difference among groups is analyzed by a two-way ANOVA test.

3.1.2. Superoxide Radical Scavenging Power

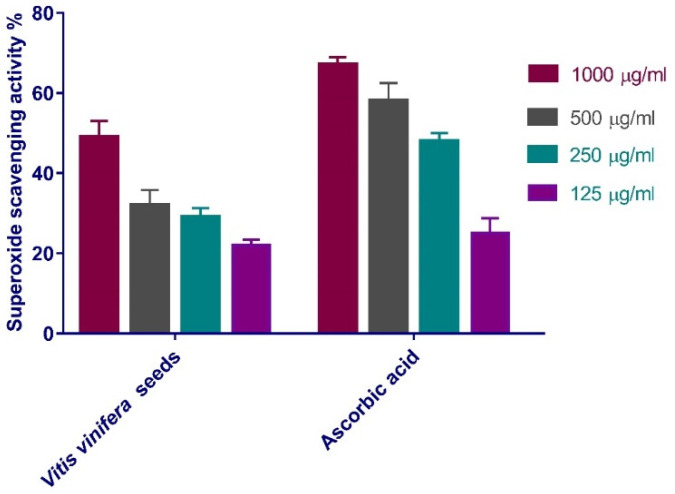

The (SOD) potential of V. vinifera seed extract was evaluated. The results revealed that the scavenging impact of the standard and extract rises with concentration (Figure 2), with V. vinifera seed extract exhibiting the maximum SOD scavenging activity. V. vinifera seed extract has 49% superoxide scavenging efficacy at 1000 μg/mL concentration. IC50 (The concentration of V. vinifera seed extract required for 50% inhibition) was detected to be 151.2 µg/mL, whereas 155.8 μg/mL was needed for ascorbic acid.

Figure 2.

SOD scavenging power of V. vinifera seed extract at variant concentrations (1000 µg/mL, 500 µg/mL, 250 µg/mL, and 125 µg/mL). Bars illustrate mean ± SD (standard deviation). Significant difference among all groups is evaluated by a two-way ANOVA test.

3.2. Wound Healing Activity

3.2.1. Estimation of Wound Closure Rate

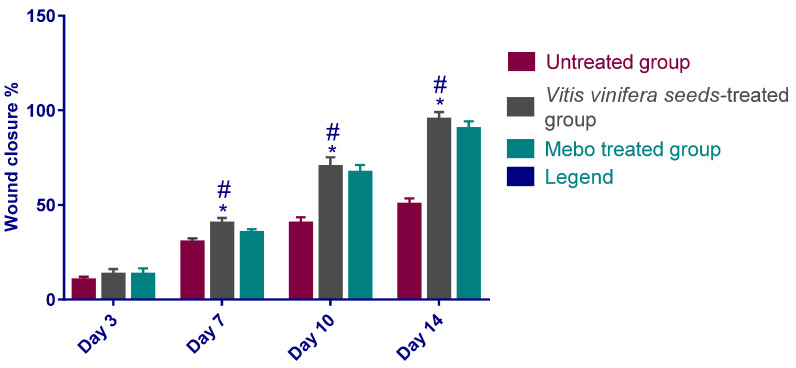

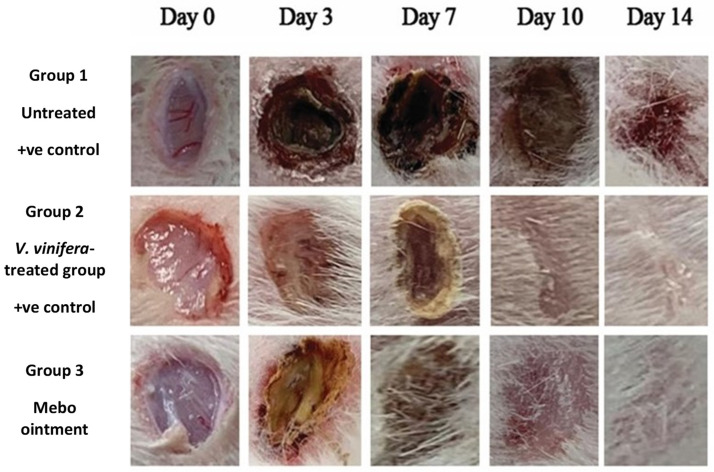

The results show that the wound closure rate in all experimental groups amplified in a time-dependent mode. The wound closure percentages were about 10 to 13% in each group on day 3 after injury, with the smallest being in the untreated group and the highest in the treated ones, with no significant difference (p > 0.001) between groups. However, the wound closure in the V. vinifera seed-treated group reached 40% on day 7 after treatment, which was significantly higher (p < 0.001) than the corresponding untreated group (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Wound closure percentages in tested groups; group 1: Untreated group (the positive control); group 2: V. vinifera seed-treated group; group 3: Mebo®-treated group, over time post-injury (0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 days). Significant difference between groups is analyzed by a two-way ANOVA test. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. * p < 0.001 compared with the data of the untreated group on the respective day and # p < 0.001 in comparison with those of the Mebo® group on the respective day.

Figure 4.

Wound closure rates in tested groups (group 1: Untreated group representing the control; group 2: V. vinifera seed-treated group; group 3: (MEBO®-treated group) over time post-injury (0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 days). Significant difference among groups is evaluated by a two-way ANOVA test. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. p < 0.001 compared to those of the control group on the respective day and p < 0.001 compared with those of the Mebo® group on the relevant day.

Additionally, the group that was treated with V. vinifera seed extract also produced high wound closure percentages compared to those of the MEBO® (Moist Exposed Burn Ointment)-treated group (p < 0.001).

The percentage of wound closing of the V. vinifera seed-treated group (70%) were significantly greater (p < 0.001) than that of untreated group (40%) on the tenth day after injury.

On day 14, the wounds in the treated groups were perfectly cured and the wound closure scored 95% in rabbits that were treated with V. vinifera seed extract and 90% in the MEBO®-treated group (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

3.2.2. Effect of Seed Extract of V. vinifera on Expression of TGF-β, TNF-α, IL-1β, Collagen Type I and VEGF

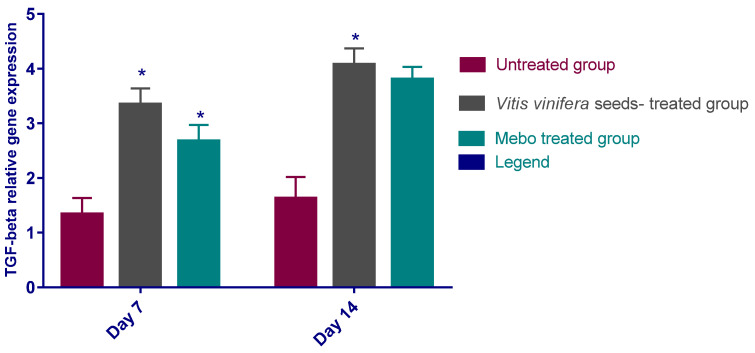

Figure 5 depicts the mRNA expression of TGF-β following excisional wound therapy with V. vinifera seed extract and MEBO®. TGF-β relative mRNA expression in skin tissues was substantially higher in V. vinifera seed-treated wounds for 7 or 14 days in comparison to the positive control group (p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Relative gene expression of TGF-β in wound layers of various groups. After making normalization to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), the data indicate a fold difference in expression relative to the normal control group. The bars reflect the mean ± SD and are based on the results of three independent investigations. A one-way ANOVA test is utilized to measure whether there is a significant variation between groups, where: * p < 0.001 when compared to the untreated group on a specified day, and p < 0.001 when compared to the Mebo® group on the same day.

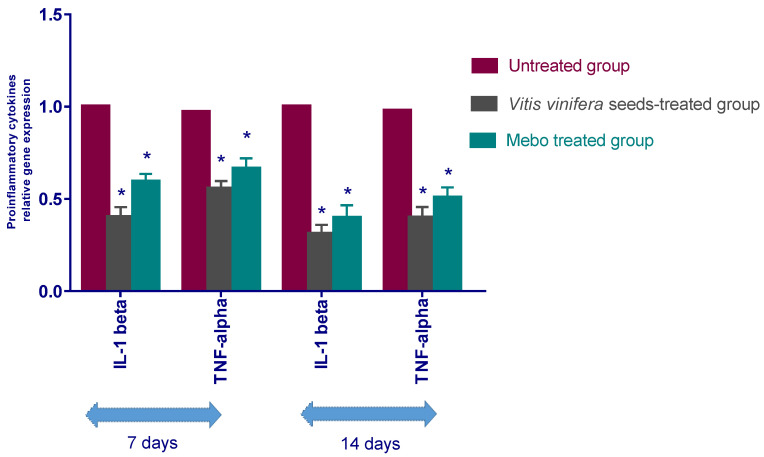

As illustrated in Figure 6, the gene expression of TNF-α and IL-1β was explained. Analysis of the gene expression of full-density wound specimens on day 7 post-injury showed that the action of the inflammatory markers’ TNF-α and IL-1β was remarkably downregulated in wounds treated with V. vinifera seed extract or Mebo® compared to the untreated wounds. However, wounded rabbits treated with V. vinifera seed extract displayed a much apparent reduction in the inflammatory markers (TNF-α, and IL-1β) when in comparison to the Mebo®-treated group. Moreover, V. vinifera seed extract treatment or MEBO® treatment for 14 days showed a significantly dramatic decrease in TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA expression in comparison to the untreated group at (p < 0.001). Again, the expressions of TNF-α as well as IL-1β in V. vinifera seed-treated wounds were markedly lower than in the Mebo®-treated group.

Figure 6.

Relative gene expression of both IL-1β and TNF-α in wound tissues of various groups. After making normalization to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), the data indicate a fold difference in expression relative to the natural control group. The bars indicate the mean ± SD and are based on the results of three independent investigations. A one-way ANOVA test is employed to measure whether there is a significant change between groups, where: * p < 0.001 when compared to the untreated group on a specified day, and p < 0.001 when compared to the Mebo® group on the same day.

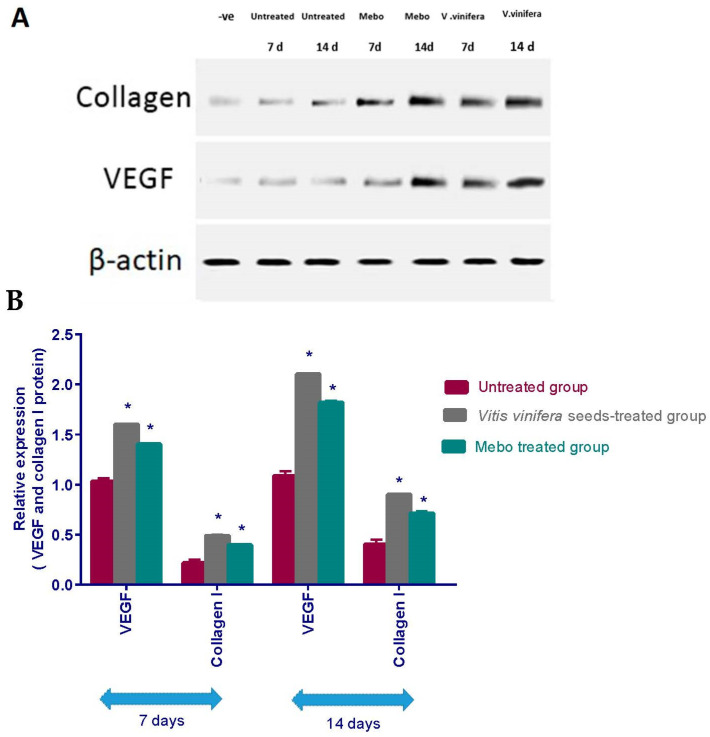

As illustrated in Figure 7, the relative protein expression of VEGF and type I collagen was illustrated. Analysis of the relative expression of VEGF as well as type I collagen in full thickness wound samples on day 7 post-injury showed significantly upregulated levels in wounds treated with V. vinifera seed extract or MEBO® compared to the untreated wounds. However, wounded rabbits treated with V. vinifera seeds displayed a much more significant elevation in the relative protein expression compared to Mebo®-treated rabbits. Moreover, V. vinifera seed extract treatment or MEBO® treatment for 14 days revealed a more significant elevation in relative protein expression when compared to untreated wounds at (p < 0.001). Again, the relative expression of VEGF and type I collagen genes in V. vinifera seed-treated wounds was markedly higher than Mebo®-treated wounds.

Figure 7.

Effect of V. vinifera seed extract on the expression of VEGF and collagen type I proteins. (A) Representative immunoblotting of VEGF, collagen type I proteins, and β-actin proteins for all groups. (B) Densitometric expression of VEGF and collagen type I proteins was expressed as fold difference relative to normal control rabbits applying bands in (A) seeking normalization to the comparable internal control β-actin. The bars show the mean ± SD and are based on the results of three independent investigations. A one-way ANOVA test is applied to measure whether there is a significant difference between groups, where: * p < 0.001 when compared to the positive control group on a specified day, and p < 0.001 when compared on the same day to the Mebo® group.

3.2.3. Histopathological Investigation

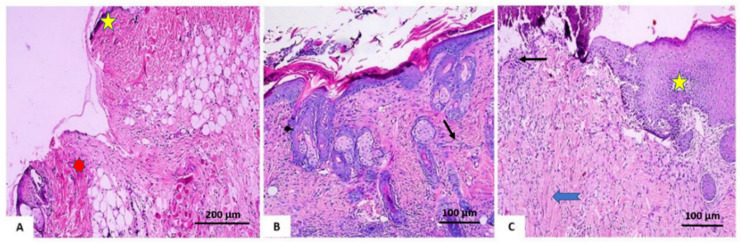

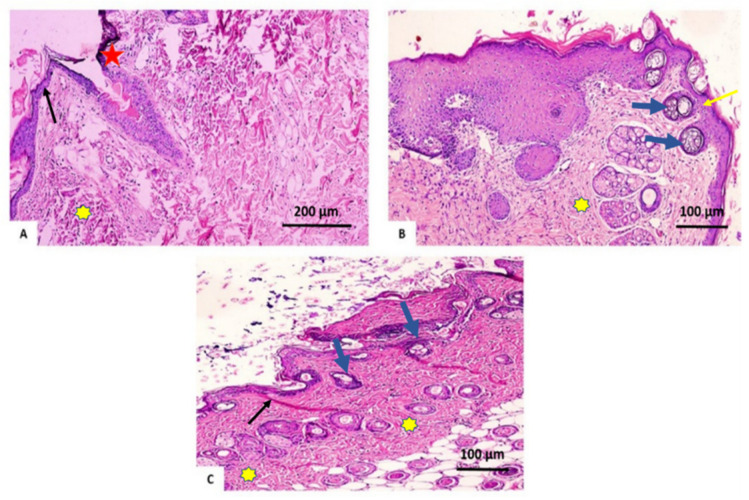

On day 7 after treatment, group 1 (the control group) demonstrated normal wound dominance with its normal architecture, including epidermis, dermal collagen bundles, hair follicles as well as oil glands. The wound showed sloughed granulation tissue, in addition to collagen fibers compactly packed in an irregular form, inflammatory cellular infiltration, blood clots, and extravasated red blood cells. In the deepest area of the lesion, the striated muscle exposed necrotic myofiber (Figure 8A). Group 2 (V. vinifera seed extract-treated group), the blood clot knotted over the wound was still visible, partial reepithelization and granulation tissue occupying the injury from below was mainly cellular. Confused dense collagen with fibers developed compactly formed in an uncommon arrangement resulting in specific scarring by relation to alternative treated groups (Figure 8B). Scare tissues closing the wound and crawling of epidermal cells at wound borders were announced with limited re-epithelization in Group 3 (Mebo®-treated group). A significant inflammation-derived cellular infiltration (predominantly of macrophages) and collagen fibers developed, packing the defect in a reticular type with distances in between approximately nearing those of the neighbor’s natural dermis. The reticular dermis involves the typical active, enlarged, spindle-shaped fibroblasts containing the basophilic cytoplasm and oval nuclei (open face) (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Skin wounds seven days post-incision. (A) Group 1 shows ordinary wounded edges with the ordinary epidermis (yellow star). The wound is packed with sloughed granulation tissue (represented by red asterisk) and blood clots. (B) Group 2 shows dermal collagen fibers compactly organized (black arrow). (C) Group 3 shows scar tissue blocking the wound (yellow star), collagen fibers (blue arrowhead) mirroring that of the neighboring normal dermis, as well as inflammatory cellular infiltration of macrophages (black arrows). (Hematoxylin and eosin stain 200 and 400).

At the post-treatment day 14, group 1 (untreated group) produced an extensive wound area and was packed with a heavy coat of granulation material, which was composed of numerous layers of connective tissue cells with inflammatory cellular infiltration included in an acidophilic matrix. The dermis is composed of confused, weak collagen with noticeable neovascularization (Figure 9A). In group 2 (V. vinifera seed-treated group) showed contracted scar tissue blocked the wound and the epidermis appeared formed of only 1–3 rows of epithelial cells. The granulation tissue from below was mainly cellular and populated with fibroblasts, while the reticular layer contained disorganized dense compactly arranged collagen fibers (Figure 9B). In group 3 (Mebo®-treated groups), the skin tissue presented more or less normal with ordinary stratified keratinized epithelium. Soft scar tissue may be found extended into the dermis. The dermal matrix offered some hair follicles, many blood capillaries, and a lack of inflammatory cells penetration. The collagen bundles in the papillary dermis are displayed as fine connecting bundles, and the reticular dermis is produced as coarse wavy bundles that appeared in diverse paths (Figure 9C).

Figure 9.

Wounded skin 14 days after incision. (A) Group 1 presents a large wound area with necrosis and discontinuation of the skin (red star) excessive inflammatory cells penetration included in an acidophilic matrix (yellow asterisks), and the ordinary skin (black arrow). (B) Group 2 shows epidermis composed of 1–3 rows of epithelial cells (yellow arrow), collagen fibers compactly established with great fibroblasts (yellow asterisk), as well as freshly developed hair follicles (blue arrows). (C) Group 3 illustrates normal epithelium, fine scar tissue developing into the dermis (thick black arrows), reticular dermis bears coarse collagen bundles (appearing wavy) established in various ways (yellow asterisk), as well as the freshly created hair follicles (blue arrows). (H and E stain 200 and 400).

3.3. Phytochemical Investigation of Vitis vinifera Crude Seed Extract

3.3.1. GC/MS Analysis for Oil Content in Vitis vinifera Crude Extract

V. vinifera seeds yielded 1.20% v/w oil dry weight, marked by having no odor, being lighter than water, and yellow colored with white faint turbidity at chamber warmth. A total of 27 compounds were identified using GC/MS analysis, representing 71.16% (Table 1) of the total, and consisting of fatty acids (FA), lipids, and hydrocarbons, where fatty acids were the major item and represented about 50.33% of the oil while the hydrocarbons represented about 19.04%. Twenty-one FA were identified including fourteen saturated fatty acid (27.54%), four monounsaturated fatty acid (8.32%), and three polyunsaturated fatty acid (14.47%). The sixteen major FAs found in V. vinifera seeds oil were C9:0, C9:0, C14:0, C15:0, C16:1 (9), C16:0, C17:0, C18:2 (9,12), C18:2 (12,15), C18:1 (9), C18:1 (9), C18:0, C18:3 (6,9,11), C20:1 (11), C20:, and C22:1 (13) (Table 1). It was observed that palmitic, azelaic, and stearic acids were the pre-dominant SFA in V. vinifera seed oil, accounting for about 8.90%, 3.85%, and 3.84% of all the saturated FA, respectively. Moreover, the total UFA content was around 22.79%. Among the UFA, 9-hexadecenoic, 9-octadecenoic, and cis-11-eicosenoic acids were the pre-dominant MUFA, accounting for almost 2.57%, 2.42%, and 2.00% of the total MUFA, respectively. Combined n-2, and n-3 PUFA (18:2, C18:2, and C18:3) accounted for 14.47% of total FA, which contained 6.91, 5.72, and 1.84% of 9,12-octadecadienoic acid, 12,15-octadecadienoic acid, and 6-cis,9-cis,11-trans-octadecatrienoic acid, as major ones, respectively. Lipids represented 1.79%, which accounted mainly for 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid,2,3 dihydroxy propyl ester, and 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid,2-(acetyloxy)-1-[(acetyloxy)methyl] ethyl ester (Table 1). While hydrocarbons represented about 19.04% and included tetradecane, 1-hexadecanol, 1-docosene, and nonacos-1-ene (Table 1, Figure S1).

Table 1.

Vitis vinifera seed oil composition using GC/MS analysis.

| No. | Compound | C:D | Type | Area % | RT | RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tetradecane | C14:0 | SHC | 1.06 | 5.94 | 920 |

| 2 | Nonanoic acid, 9-oxo- | C9:0 | SFA | 2.31 | 10.60 | 887 |

| 3 | Octanedioic acid (Suberic acid) | C8:0 | SFA | 0.55 | 10.81 | 904 |

| 4 | Octanoic acid, 6,6-dimethoxy- | C10:0 | SFA | 0.80 | 11.81 | 827 |

| 5 | Undecanoic acid, 10-methyl- | C12:0 | SFA | 0.34 | 12.30 | 864 |

| 6 | Nonanedioic acid (Azelaic acid) | C9:0 | SFA | 3.85 | 12.87 | 912 |

| 7 | 1-Hexadecanol | C16:0 | SFO | 2.43 | 13.64 | 943 |

| 8 | Decanedioic acid (Sebacic acid) | C10:0 | SFA | 0.99 | 14.71 | 902 |

| 9 | Tetradecanoic acid (Myristic acid) | C14:0 | SFA | 1.54 | 16.09 | 923 |

| 10 | Undecanedioic acid | C11:0 | SFA | 0.34 | 16.54 | 863 |

| 11 | Pentadecanoic acid | C15:0 | SFA | 1.30 | 17.87 | 784 |

| 12 | 9-Hexadecenoic acid | C16:1 (9) | MUFA | 2.57 | 19.21 | 915 |

| 13 | Hexadecanoic acid (Palmitic acid) | C16:0 | SFA | 8.90 * | 19.61 | 939 |

| 14 | 1-Docosene | C22:1 (1) | MUHC | 11.55 * | 20.76 | 962 |

| 15 | Heptadecanoic acid (Margaric acid) | C17:0 | SFA | 1.04 | 21.21 | 893 |

| 16 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid | C18:2 (9,12) | PUFA | 6.91 * | 22.31 | 923 |

| 17 | 12,15-Octadecadienoic acid | C18:2 (12,15) | PUFA | 5.72 * | 23.10 | 885 |

| 18 | 9-Octadecenoic acid | C18:1 (9) | MUFA | 2.42 | 23.16 | 921 |

| 19 | Octadecanoic acid (Stearic acid) | C18:0 | SFA | 3.84 | 23.33 | 911 |

| 20 | 6-Cis,9-cis,11-trans-octadecatrienoic acid | C18:3 (6,9,11) | PUFA | 1.84 | 24.72 | 849 |

| 21 | Cis-11-eicosenoic acid | C20:1 (11) | MUFA | 2.00 | 25.37 | 848 |

| 22 | Eicosanoic acid | C20:0 | SFA | 1.48 | 25.72 | 882 |

| 23 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid,2,3 dihydroxy propyl ester | C21:3 (9,12,15) | Lipid | 0.30 | 26.27 | 808 |

| 24 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid,2-(acetyloxy)-1-[(acetyloxy)methyl] ethyl ester | C25:3 (9,12,15) | Lipid | 1.49 | 26.50 | 817 |

| 25 | Nonacos-1-ene | C29:1 (1) | MUHC | 4.00 | 26.61 | 920 |

| 26 | 13-Docosenoic acid | C22:1 (13) | MUFA | 1.33 | 28.04 | 894 |

| 27 | Docosanoic acid | C22:0 | SFA | 0.26 | 28.37 | 852 |

| SFA | 27.54 | |||||

| MUFA | 8.32 | |||||

| PUFA | 14.47 | |||||

| SHC | 1.06 | |||||

| MUHC | 15.55 | |||||

| SFO | 2.43 | |||||

| Lipid | 1.79 | |||||

| Total | 71.16 | |||||

RI: retention index, RT: the retention time/minute, C:D: carbon number per double bond number-covering their position, *: main compound, SFA: saturated fatty acid, MUFA: mono unsaturated fatty acid, PUFA: poly unsaturated fatty acid, SHC: saturated hydrocarbon, MUHC: mono unsaturated hydrocarbon, SFO: saturated fatty alcohol.

3.3.2. Phytochemical Investigation of V. vinifera Seed Extract

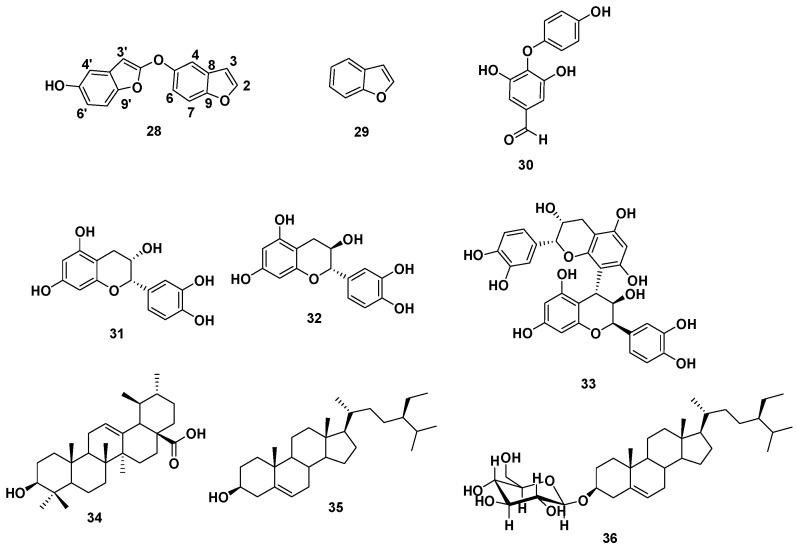

Based on physicochemical as well as chromatographic characters, the spectra obtained from UV, proton (1H), with DEPT-Q NMR, along with the relation to the biography and some authoritative references, the crude extract of V. vinifera seeds provided the new benzofuran dimer (28) along with eight known compounds (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Structures of compounds isolated from Vitis vinifera seed extract. 2-(Benzofuran-5-yloxy) benzofuran-5-ol 28, benzofuran 29 [20], 4-(4-hydroxyphenoxy)-3,5-dihydroxybenzaldehyde 30 [21]. (-)-Epi-catechin 31 [14], catechin 32 [14], procyanidin B2 33 [14], ursolic acid 34 [22], β-sitosterol 35 [23], β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside 36 [24].

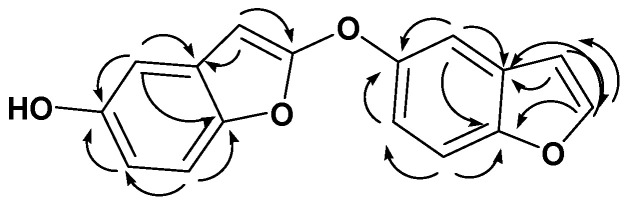

Analysis of the [High Resolution Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry], (HR-ESI-MS), 1D, and 2D NMR analysis data of compound 28 advocated a possible dimeric benzofuran derivative core scaffold [25]. The HR-ESI-MS data presented an adduct pseudo-molecular ion peak at m/z 267.0659 [M + H]+ (calc. for C16H11O4, 267.0657), suggesting 12 degrees of unsaturation. The 1H and DEPT-Q 13C NMR data (Table 2, Figures S2 and S3), as well as HSQC (heteronuclear single quantum correlation experiment) data (Figure S4), predicted nine methine resonance peaks appeared at δH 7.68, d (7.0) δC 145.9, δH 7.09, dd (3.0, 7.0) δC 104.0, δH 7.40, d (2.5) δC 108.8, δH 6.37, dd (2.5,8.0) δC 114.0, and δH 7.30, d (8.0) δC 123.8, δH 7.79, d (3.0) δC 144.5, δH 7.40, d (2.5) δC 108.8, δH 6.37, dd (2.5,8.0) δC 114.0, δH 7.30, d (8.0) δC 123.8, and seven quaternary carbons at δC 113.5, 116.8, 148.4, 148.4, 157.3, 157.3, and 160.8, indicating the characteristic core structure for dimeric benzofuran derivatives [25], where HMBC (heteronuclear multiple bond correlation) experiment of 28 (Figure 11 and Figure S5) confirmed that. The downfield shift for resonating peaks for C5, C5` at 148.4, and 160.8, suggested the presence of hydroxyl groups at C5 and C5` in each benzofuran unit.

Table 2.

DEPT-Q (400 MHz) and 1H-NMR (100 MHz) data of compound 28 in CDCL3; carbon multiplicities were figured out by the DEPT-Q experiments.

| Position | δ C | δH (J in Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 145.9, CH | 7.68, d (7.0) |

| 3 | 104.0, CH | 7.09, dd (3.0, 7.0) |

| 4 | 108.8, CH | 7.40, d (2.5) |

| 5 | 148.4, qC | |

| 6 | 114.0, CH | 6.37, dd (2.5,8.0) |

| 7 | 123.8, CH | 7.30, d (8.0) |

| 8 | 116.8, qC | |

| 9 | 157.3, qC | |

| 2′ | 148.4, qC | |

| 3′ | 144.5, CH | 7.79, d (3.0) |

| 4′ | 108.8, CH | 7.40, d (2.5) |

| 5′ | 160.8, qC | |

| 6′ | 114.0, CH | 6.37, dd (2.5,8.0) |

| 7′ | 123.8, CH | 7.30, d (8.0) |

| 8′ | 113.5, qC | |

| 9′ | 157.3, qC |

qC, quaternary, CH, methine.

Figure 11.

Selected HMBC ( )correlations of compound 28.

)correlations of compound 28.

Comparing the 1H and DEPT-Q 13C NMR data (Table 2, Figure 10), along with HSQC data (Figure S4), for C2‵ (δC 148.4, qC), and C3‵ ( δH 7.79, d (3.5) δC 144.5, CH) with C2 (7.68, d (7.0) δC 145.9, CH), and C3 (δH 7.09, dd (3.5,7.0) δC 104.0, CH) suggested the attachment of one of the benzofuran units at C2‵ by converting the methine of C2‵ to quaternary carbon (Table 2). The DEPT-Q 13C NMR data (Table 2, Figure S3) showed downfield shift for resonance peaks of C2‵ (δC 148.4) and C3‵ (δC 144.5) compared with C2 (δC 145.9) and C3 (δC 104.0), suggesting O attachment at C2‵. Accordingly, compound 28 was identified as 2-(benzofuran-5-yloxy) benzofuran-5-ol.

3.4. Molecular (In Silico) Docking Studies

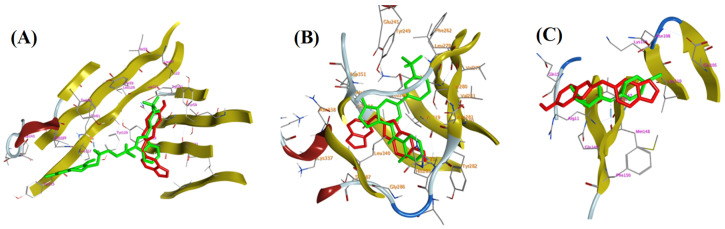

In silico docking studies have been done on the crystal structures of the three main targets that might contribute to the wound healing potential of V. vinifera seed extract, TNF-α, PDB ID: 2AZ5, TGFBR1, PDB ID: 6B8Y, and IL-1β, PDB ID: 6Y8M, which were downloaded from the protein data bank (PDB). The binding free energy represented by (Kcal/mol) and the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD, Å) in the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) program were utilized in ranking different isolated compounds in comparison to the co-crystallized ligand. Besides, the different interactions within the active sites of amino acid residues along with their energies were listed. Firstly, the docking studies within the TNF-α active site showed that all the test compounds attained binding energies of −3.7887 to −6.3236 kcal/mol), close to that of the co-crystallized ligand (−5.5254 kcal/mol), with an accuracy of less than 2 Å RMSD. Interestingly, the binding accuracy of these test compounds was better than the co-crystallized ligand and one of them has higher binding energy than the co-crystallized ligand (Table 3).

Table 3.

Interaction binding energies (S; kcal/mol) and binding accuracy (RMSD; Å) of isolated compounds from V. vinifera seeds and co-crystallized ligand within TNF-α active site (PDB ID: 2AZ5).

| Compounds | Energy Score (S; kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| 29 | −3.7887 | 0.9620 |

| 31 | −4.4254 | 1.2060 |

| 33 | −6.3236 | 1.2519 |

| 34 | −5.2661 | 1.1197 |

| 2AZ5 co−crystallized ligand | −5.5254 | 1.3787 |

| 28 | −4.8903 | 1.5440 |

| 30 | −4.5148 | 1.5722 |

| 32 | −4.5435 | 1.8509 |

| 35 | −5.3554 | 1.6566 |

| 36 | −5.5049 | 1.8187 |

Virtual screening studies on TGFBR1 kinase showed interesting and promising findings. Almost all the isolated compounds (except ursolic acid 34 and β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside 36) showed higher affinity to the active site over the co-crystallized ligand, this was presented by their better binding energy value (−4.847: −7.3066 kcal/mol) compared to the co-crystallized ligand (−5.102 kcal/mol) with an accuracy of less than 2 Å RMSD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Interaction binding energy (S; kcal/mol) as well as (RMSD; A) binding accuracy of isolated compounds from V. vinifera seeds and co-crystallized ligand within TGFBR1 kinase (PDB ID: 6B8Y).

| Compounds | Energy Score (S; kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| 28 | −5.7708 | 0.9288 |

| 29 | −4.847 | 0.5381 |

| 30 | −6.777 | 0.9806 |

| 31 | −5.5238 | 1.0294 |

| 32 | −7.019 | 0.9637 |

| 34 | 6.5779 | 1.0290 |

| 6B8Y co-crystallized ligand | −5.102 | 1.1231 |

| 33 | −7.3066 | 1.6720 |

| 35 | −5.4909 | 1.2527 |

| 36 | 2.7322 | 2.2620 |

All the isolated compounds showed binding free energy comparable to that of the co-crystallized ligand within the interleukin 1 beta active site with accuracy in the same way below 2 Å RMSD (Table 5). Interestingly, β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside 36 showed higher binding energy (S = −5.2574 kcal/mol) than co-crystallized ligand but its accuracy was as not high as its test congeners (>2 Å RMSD).

Table 5.

Interaction binding energy (S; kcal/mol) and binding accuracy (RMSD; A) of isolated compounds from V. vinifera seeds and co-crystallized ligand within the IL-1β active site (PDB ID: 6Y8M).

| Compounds | Energy Score (S; kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| 29 | −3.1641 | 1.0862 |

| 30 | –3.6842 | 1.0402 |

| 32 | −3.7588 | 1.0871 |

| 34 | −4.3905 | 1.0397 |

| 35 | −4.6213 | 0.8752 |

| 6Y8M co-crystallized ligand | −4.2536 | 1.0950 |

| 28 | −3.9952 | 1.3281 |

| 31 | −4.2309 | 1.1256 |

| 33 | −4.2061 | 1.8351 |

| 36 | −5.2578 | 2.1526 |

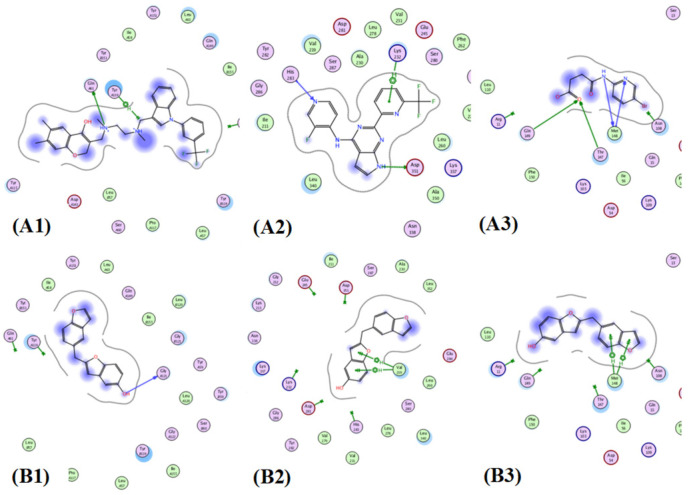

Moreover, the 2D-interaction diagram Figure 12 showed a good fitting of compound 28 with various amino acid residues of three active sites comparable to the co-crystallized ligands.

Figure 12.

Docking poses of co-crytallized ligand (green) and compound 1 (red) within: (A) TNF-α (PDB ID: 2AZ5); (B) TGFBR1 kinase (PDB ID: 6B8Y); (C) IL-1β (PDB ID: 6Y8M).

Moreover, the 2D-interaction diagram Figure 13 showed a good fitting of compound 28 with various amino acid residues of three active sites comparable to the co-crystallized ligands; results were listed in Table 6.

Figure 13.

Showing 2D-binding interactions of co-crystallized ligand (A1–A3) and compound 1 (B1–B3) within active sites of: TNFα (PDB ID: 2AZ5); TGFBR1 kinase (PDB ID: 6B8Y); and IL-1β (PDB ID: 6Y8M).

Table 6.

Binding free energy score (S; kcal/mol) with binding interactions for different co-crystallized ligands and compound 28 within TNF-α (PDB ID: 2AZ5); TGFBR1 kinase (PDB ID: 6B8Y); and IL-1β (PDB ID: 6Y8M) binding sites.

| Active Site | Ligand | Binding Energy Score (S; kcal/mol) |

Ligand—Active Site Interactions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. a. Residue | Bond Type | Bond Length (Å) | |||

| TNF-α (PDB ID: 2AZ5) |

Co-crystallized ligand | −5.5254 | GLN 61 | H-donor | 2.97 |

| TYR 119 | H-pi | 4.08 | |||

| Compound 28 | −4.8903 | GLY 121 | H-donor | 3.11 | |

| TGFBR1 kinase (PDB ID: 6B8Y) | Co-crystallized ligand | −5.102 | ASP 351 | H-donor | 2.72 |

| HIS 283 | H-acceptor | 2.89 | |||

| LYS 232 | pi-H | 3.94 | |||

| Compound 28 | −5.7708 | VAL 219 | pi-H | 4.27 | |

| VAL 219 | pi-H | 4.15 | |||

| IL-1β (PDB ID: 6Y8M) | Co-crystallized ligand | −4.2536 | MET 148 | H-donor | 2.73 |

| MET 148 | H-acceptor | 2.94 | |||

| THR 147 | H-acceptor | 2.62 | |||

| GLN 149 | H-acceptor | 2.46 | |||

| Compound 28 | −3.9952 | MET 148 | pi-H | 4.51 | |

| MET 148 | pi-H | 4.15 | |||

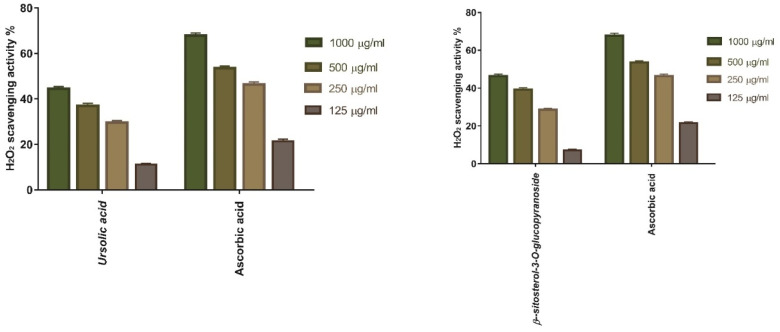

3.5. In Vitro Antioxidant Potential of the Two Compounds Isolated from V. vinifera Seed Extract

3.5.1. Hydrogen Peroxide Scavenging Activity of Ursolic Acid and β-Sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside

The antioxidant activities of ursolic acid 34 and β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside 36 as a scavenger potential against H2O2 were investigated in this study. The maximal H2O2 radical scavenging activities of compounds 34 and 36 were 44.44% and 46.42% at 1000 µg/mL concentration, respectively, according to the data. Compounds 34 and 36 suppressed the formation of H2O2 radicals in a dose-dependent manner, demonstrating a consistent antioxidant potential with IC50 of 197.1 and 222 μg/mL concentration, respectively (Figure 14), in comparison with ascorbic acid (IC50 = 181.2 μg/mL).

Figure 14.

H2O2 radical scavenging activity of ursolic acid 34, and β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside 36 at different concentrations (1000 µg/mL, 500 µg/mL, 250 µg/mL, and 125 µg/mL). Bars show mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant difference among groups is analyzed by a two-way-ANOVA-test.

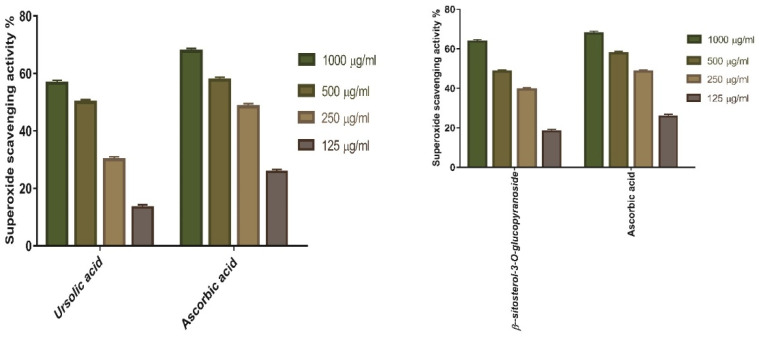

3.5.2. Superoxide Radical Scavenging Activity of Ursolic Acid, and β-Sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside

SOD activities of ursolic acid 34, and β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside 36 was evaluated. The results showed that both compounds had 55.66%, and 63.63% SOD at 1000 μg/mL concentration, respectively. The concentration of compounds 34, and 36 needed for 50% inhibition (IC50) was 221.4, and 205 µg/mL, respectively, whereas 156.6 μg/mL was demanded for ascorbic acid (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Superoxide radical scavenging potential of ursolic acid as well as β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside at variant concentrations (1000 µg/mL, 500 µg/mL, 250 µg/mL, and 125 µg/mL). Bars represent mean ± SD (standard deviation). Significant differences between groups are investigated by a two-way-ANOVA-test.

4. Discussion

Wound healing include several steps with improving tissue formation in degenerated tissue as near as possible to its real nature [26]. Studies reported that wound healing is classified into three phases: Inflammation process involving suppression of immune system and secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators, a proliferative phase through collagen growth, proliferation of fibroblasts, and development of new blood vessels, beside a remodeling phase involving regeneration and replacement of injured tissue [27,28]. Therefore, drugs that could speed wound repair with a potential contribution in all phases of the wound healing process will be good targets, specifically those with small costs and fewer side effects.

Topical application of V. vinifera seed extract on wounded excisions in the animals exhibited a significant (p < 0.001) diminishing in wound area compared to the untreated wounds (Figure 4) and that was in addition to the accelerated wound closure rate in V. vinifera seed extract-treated wounds. Wound closure can be characterized as the centripetal flow of the boundaries of a full-thickness wound to encourage the closure of the wound tissue [29,30,31]. Wound closure is thus a signal of re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, granulation, keratinocyte differentiation, fibroblast proliferation, and proliferation [31].

Wound-healing processes require complex interactions between cells and different growth factors [32], where the TGF-β affects the most important part throughout all stages of wound healing. During the inflammatory as well as hemostasis phase, the TGF-β recruits and stimulates inflammatory cells, macrophages, and coating neutrophils, whereas, in the proliferative-phase, it produces numerous cellular replies comprising angiogenesis, granulation tissue improvement, re-epithelialization and extracellular matrix removal [32]. It encourages fibroblasts to do proliferation and vary into myofibroblasts which cooperate in wound closure in the remodeling phase [33]. Pastar et al., 2014, and Haroon et al., 2002 [34,35], noted that chronic and non-healing wounds generally produce a failure of TGF-β1 warning, while Feinberg et al., 2000 [36], declared that TGF-β1 delivers an inhibitory effect on the interpretation of collagenases, which impair collagen and extracellular matrix. These notes are coherent with the above measurements, which established that V. vinifera seed extract enhanced TGF-β1 expression and hence recovered wound healing. When compared to untreated wound tissues, gene expression investigation of wound tissues revealed an increase in TGF-β1 levels in V. vinifera-treated wound tissues. This could indicate that V. vinifera seed extract increased TGF-β1 expression in injured tissues.

Expression of IL-1β, and TNF-α (pro-inflammatory cytokines) is required to improve neutrophils, and remove bacteria and pollution from the wound section and identifies dynamic inducer MMPs (metalloproteinase) regeneration in inflammatory and fibroblast cells. In the wound healing process, the MMP diminishes and excludes broken extracellular matrixes (ECM) to aid wound reconstruction [37]. However, a long period of the inflammatory phase draws to a complication in the healing process and these cytokines and proteinase damage the tissue and lead to the outcome of chronic wounds. TNF-α is one of the growth factors excreted from macrophages, which incorporates IL-1β to enhance and overcome respective collagen manufacture and fibroblast proliferation [38]. The TNF-α prompts NF-κB, which in time encourages gene interpretation of an overabundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α as well as proteases, as MMP, to clear dispersed TNF-α and potentiate the effects of such inflammatory cytokines [39]. So, suppressing inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α; and IL-1β) by V. vinifera seed extract can inhibit continued inflammation and hence avoid impaired wound repair.

Additionally, healing the wounds is resolved by various growth factors which are excreted in feedback to injury, such as VEGF, which exerts a significant role in the regenerationof new blood vessels [40]. VEGF stimulates wound healing via various processes, consisting of collagen deposition, angiogenesis, and epithelialization, and attaches to the two VEGF receptors (VEGF-1, and VEGF-2), which are revealed on vascular endothelial cells [41]. These data are coherent with the early findings that V. vinifera seed extract enhanced VEGF expression and hence improved wound healing. The relative protein expression of VEGF was developed in V. vinifera seed extract-treated wound tissues related to untreated wound tissues, which might indicate that V. vinifera seed extract increased VEGF expression in wound tissues.

Moreover, wound improvement is interfered in by type I collagen, which is the primary protein inside skin tissue [42] and exerts an essential role in improving connective tissue by holding tissue health and an extracellular matrix outline for cellular adhesion and migration [4]. The task of collagen in wound healing is to bring fibroblasts and facilitate the removal of modern collagen to the wound bed [43]. Chronic wounds generate enormous MMPs that obstruct the ordinary wound improvement process [43]. Collagen pickles and arrests extreme MMPs located within the extracellular matrix (ECM) [43]. So, upregulation of relative expression of Type I collagen by V. vinifera seed extract can thus prevent extended inflammation and hence promote wound healing.

Antioxidants are thought to help manage wound oxidative stress and hence speed up the healing process. They usually play a critical role in controlling the damage that biological components such as DNA, protein, lipids, and body tissue may sustain in the presence of reactive species. The maximal H2O2 radical scavenging activity of V. vinifera seed extract was 48.1% at 1000 µg/mL concentration. According to the data. V. vinifera seed extract suppressed the formation of H2O2 radicals in a dose-dependent manner, demonstrating a consistent antioxidant activity with IC50 of 175.8 μg/mL concentration (Figure 1) compared with standard ascorbic acid (IC50 = 178.1 μg/mL) [44]. High levels of ROS in a wound site can stimulate collagen disintegration and hence loss of ECM. When the ECM is broken, handles such as re-epithelization, and angiogenesis, which are necessary for wounds to improve, are diminished [45,46]. Moreover, elevated ROS can induce inflammation and increases pro-inflammatory cytokines and hence prolong inflammation [47].

Besides, redox signaling and enhanced oxidative stress play a vital role in normal wound healing via encouraging hemostasis, inflammation, angiogenesis, granulation tissue creation, wound closure, and extracellular matrix development and maturation [48]. As a result, the superoxide scavenging activity of V. vinifera seed extract was evaluated. The results showed that the scavenging impact of the standard and extract rises with concentration (Figure 2), with V. vinifera seed extract exhibiting the maximum superoxide radical scavenging activity. V. vinifera seed extract has 49% SOD efficacy at 1000 μg/mL concentration, with IC50 of 151.2 µg/mL, whereas 155.8 μg/mL was needed for ascorbic acid [49]. The antioxidant activity of V. vinifera seed extract that is attributed by its H2O2 and SOD scavenging activity can eliminate ROS and hence enhance its wound-healing activity. This antioxidant potential may be endorsed to the phenolic content of the extract.

A phytochemical investigation of the seed extract was performed to explore the chemical molecules that might contribute to the wound healing activity. Phytochemical investigation of Vitis vinifera extract yielded a total of 36 compounds including twenty-seven compounds (1–27) identified from seed oil using GC/MS analysis, along with nine isolated compounds, including one new benzofuran dimer (28), and eight known ones (29–36). The structure of the new compound was elucidated using 1D and 2D NMR and HRESIMS analyses (see Section 2.2).

Molecular docking was carried out to explore the molecular targets that might contribute to the wound healing potential. The three examined targets (TGFBR1, TNF-α, and IL-1β) play a vital role in the wound healing process. The high scores and extremely comparable interaction patterns of multiple ligands in V. vinifera seed extract with the stated wound healing targets provided some molecular explanation for the extract’s wound healing effect. Additionally, the binding modes and free energies obtained for the isolated compounds during the molecular docking studies within active sites of TGFBR1, TNF-α, and IL-1β (Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6) confirm in vivo animal study results, is which manifested by the significant change in the mRNA expression of TGF-β (increased) and the inflammatory markers, TNF-α and IL-1β (decreased). Our data suggested that V. vinifera seed extract could accelerate the switching process from inflammatory to anti-inflammatory responses, which afterwards promotes healing.

5. Conclusions

In this study, Vitis vinifera seed extract displayed remarkable wound healing activity via accelerated wound closure rate, enhancing TGF-β1, VEGF, as well as Type I collagen expression, and suppressing inflammatory markers (TNF-α and IL-1β). Nine compounds were isolated and identified from V. vinifera seeds. Molecular docking analysis on three molecular targets predicted the possible mode of action in the wound healing activity. Additionally, the potent in vitro antioxidant activity of Vitis vinifera seed extract, and two isolated compounds (ursolic acid 34, and β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside 36) that are attributed by its SOD, and H2O2 scavenging activity can eliminate ROS and hence enhance its wound-healing activity. This antioxidant potential may be endorsed to the phenolic content of the extract. Finally, this study recommended the application of V. vinifera seed extract in wound care as a promising therapy to accelerate the wound healing process; however, future detailed mechanistic studies are still required to confirm those results.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R25), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors deeply acknowledge the Researchers Supporting Program (TUMA-Project-2021-6), AlMaarefa University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for supporting steps of this work.

Supplementary Materials

The next supporting information are available to be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antiox11050881/s1, Figure S1: GC-MS spectrum for V. vinifera seed oil; Figures S2–S21:1D and 2D NMR spectra of compounds 28–36. See [19,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: U.R.A. and A.H.E.; methodology: A.H.E., T.A.-W., E.M.Z., S.S. and M.M.A.-S.; software: A.H.E., M.M.G., S.A.M., Y.A.M. and F.A.; formal analysis: A.H.E., U.R.A., M.A.E., M.S.A. and S.K.A.J.; investigation: A.H.E., U.R.A., T.A.-W. and E.M.Z.; resources: A.H.E., F.A., Y.A.M. and S.S.; data curation: U.R.A., E.M.Z., A.H.E. and M.S.A.; writing—original draft: A.H.E., U.R.A. and E.M.Z.; writing—review and editing: All authors; supervision: U.R.A. and A.H.E.; project administration: S.S., M.M.A.-S., M.M.G., S.A.M., Y.A.M., F.A., M.A.E., M.S.A. and S.K.A.J.; funding acquisition: U.R.A. and M.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Deraya University authorized this study and stated that animals should not suffer at any stage of testing and should be kept in line with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (ethical permission No: 5/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R25); Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University; Riyadh; Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Benbow M. Using Debrisoft [R] for wound debridement: Maureen Benbow briefly considers different methods of wound debridement and focuses on the advantages associated with a novel, alternative method of debridement. J. Community Nurs. 2011;25:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boakye Y.D., Agyare C., Ayande G.P., Titiloye N., Asiamah E.A., Danquah K.O. Assessment of wound-healing properties of medicinal plants: The case of Phyllanthus muellerianus. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:945. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer A.J., Clark R.A. Cutaneous wound healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zahid M., Lodhi M., Rehan Z.A., Tayyab H., Javed T., Shabbir R., Mukhtar A., El Sabagh A., Adamski R., Sakran M.I., et al. Sustainable development of chitosan/Calotropis procera-based hydrogels to stimulate formation of granulation tissue and angiogenesis in wound healing applications. Molecules. 2021;26:3284. doi: 10.3390/molecules26113284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zahid M., Lodhi M., Afzal A., Rehan Z.A., Mehmood M., Javed T., Shabbir R., Siuta D., Althobaiti F., Dessok E.S. Development of hydrogels with the incorporation of Raphanus sativus L. seed extract in sodium alginate for wound-healing application. Gels. 2021;7:107. doi: 10.3390/gels7030107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agyare C., Asase A., Lechtenberg M., Niehues M., Deters A., Hensel A. An ethnopharmacological survey and in vitro confirmation of ethnopharmacological use of medicinal plants used for wound healing in Bosomtwi-Atwima-Kwanwoma area, Ghana. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;125:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farzaei H., Abbasabadi Z., Abdollahi M., Rahimi R. A comprehensive review of plants and their active constituents with wound healing activity in traditional Iranian medicine. Wounds A Compend. Clin. Res. Pract. 2014;26:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bungau S.G., Popa V.-C. Between religion and science: Some aspects: Concerning illness and healing in antiquity. Transylv. Rev. 2015;26:3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tetik F., Civelek S., Cakilcioglu U. Traditional uses of some medicinal plants in Malatya (Turkey) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;146:331–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayta S., Polat R., Selvi S. Traditional uses of medicinal plants in Elazığ (Turkey) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;154:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adnan M., Ullah I., Tariq A., Murad W., Azizullah A., Khan A.L., Ali N. Ethnomedicine use in the war affected region of northwest Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egea T., Signorini M.A., Bruschi P., Rivera D., Obón C., Alcaraz F., Palazón J.A. Spirits and liqueurs in European traditional medicine: Their history and ethnobotany in Tuscany and Bologna (Italy) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;175:241–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gharib Naseri M.K., Ehsani P. Spasmolytic effect of Vitis vinifera hydroalcoholic leaf extract on the isolated rat uterus. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2003;7:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oprea O.B., Apostol L., Bungau S., Cioca G., Samuel A.D., Badea M., Gaceu L. Research on the chemical composition and the rheological properties of wheat and grape epicarp flour mixes. Rev. Chim. 2018;69:70–75. doi: 10.37358/RC.18.1.6046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nayak B.S., Ramdath D.D., Marshall J.R., Isitor G.N., Eversley M., Xue S., Shi J. Wound-healing activity of the skin of the common grape (Vitis Vinifera) variant, cabernet sauvignon. Phytother. Res. 2010;24:1151–1157. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jadeja R., Devkar R. Polyphenols in chronic diseases and their mechanisms of action. Polyphen. Hum. Health Dis. 2014;1:615–623. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L., Sun B. Grape and wine polymeric polyphenols: Their importance in enology. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019;59:563–579. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1381071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Z.F., Zhang H. Phytochemical constituents, health benefits, and industrial applications of grape seeds: A mini-review. Antioxidants. 2017;6:71. doi: 10.3390/antiox6030071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shivananda Nayak B., Dan Ramdath D., Marshall J.R., Isitor G., Xue S., Shi J. Wound-healing properties of the oils of Vitis vinifera and Vaccinium macrocarpon. Phytother. Res. 2011;25:1201–1208. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Lampasona M.E., Catalán C.A., Gedris T.E., Herz W. Benzofurans, benzofuran dimers and other constituents from Ophryosporus charua. Phytochemistry. 1997;46:1077–1080. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)84397-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loevgren K., Hedberg A., Nilsson J.L.G. Adrenergic receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 1980;23:624–627. doi: 10.1021/jm00180a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jedinák A., Mučková M., Košt’álová D., Maliar T., Mašterová I. Antiprotease and antimetastatic activity of ursolic acid isolated from Salvia officinalis. Z. Für Nat. C. 2006;61:777–782. doi: 10.1515/znc-2006-11-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nirmal S.A., Pal S.C., Mandal S.C., Patil A.N. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of β-sitosterol isolated from Nyctanthes arbortristis leaves. Inflammopharmacology. 2012;20:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s10787-011-0110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S.-H., Shin D.-S., Oh M.-N., Chung S.-C., Lee J.-S., Chang I.-M., Oh K.-B. Inhibition of sortase, a bacterial surface protein anchoring transpeptidase, by β-sitosterol-3-O-glucopyranoside from Fritillaria verticillata. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2003;67:2477–2479. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toyoda K., Yaoita Y., Kikuchi M. Three New Dimeric Benzofuran Derivatives from the Roots of Ligularia stenocephala M ATSUM. et K OIDZ. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005;53:1555–1558. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diegelmann R.F., Evans M.C. Wound healing: An overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing. Front. Biosci. 2004;9:283–289. doi: 10.2741/1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landén N.X., Li D., Ståhle M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: A critical step during wound healing. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016;73:3861–3885. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2268-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krzyszczyk P., Schloss R., Palmer A., Berthiaume F. The role of macrophages in acute and chronic wound healing and interventions to promote pro-wound healing phenotypes. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:419. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pachuau L. Recent developments in novel drug delivery systems for wound healing. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015;12:1895–1909. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1070143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suguna L., Singh S., Sivakumar P., Sampath P., Chandrakasan G. Influence of Terminalia chebula on dermal wound healing in rats. Phytother. Res. 2002;16:227–231. doi: 10.1002/ptr.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang T., Yin L., Yang J., Shan G. Emodin, an anthraquinone derivative from Rheum officinale Baill, enhances cutaneous wound healing in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007;567:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wankell M., Munz B., Hübner G., Hans W., Wolf E., Goppelt A., Werner S. Impaired wound healing in transgenic mice overexpressing the activin antagonist follistatin in the epidermis. EMBO J. 2001;20:5361–5372. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beer H.-D., Gassmann M.G., Munz B., Steiling H., Engelhardt F., Bleuel K., Werner S. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2000. Expression and function of keratinocyte growth factor and activin in skin morphogenesis and cutaneous wound repair; pp. 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pastar I., Stojadinovic O., Yin N.C., Ramirez H., Nusbaum A.G., Sawaya A., Patel S.B., Khalid L., Isseroff R.R., Tomic-Canic M. Epithelialization in wound healing: A comprehensive review. Adv. Wound Care. 2014;3:445–464. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haroon Z.A., Amin K., Saito W., Wilson W., Greenberg C.S., Dewhirst M.W. SU5416 delays wound healing through inhibition of TGF-β activation. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2002;1:121–126. doi: 10.4161/cbt.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feinberg R.A., Kim I.S., Hokama L., De Ruyter K., Keen C. Operational determinants of caller satisfaction in the call center. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2000;11:34–36. doi: 10.1108/09564230010323633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schultz G.S., Ladwig G., Wysocki A. Extracellular matrix: Review of its roles in acute and chronic wounds. World Wounds. 2005;2005:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasaki M., Kashima M., Ito T., Watanabe A., Izumiyama N., Sano M., Kagaya M., Shioya T., Miura M. Differential regulation of metalloproteinase production, proliferation and chemotaxis of human lung fibroblasts by PDGF, interleukin-1β and TNF-α. Mediat. Inflamm. 2000;9:155–160. doi: 10.1080/09629350020002895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sano C., Shimizu T., Tomioka H. Effects of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor on the tumor necrosis factor-alpha production and NF-κB activation of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Cytokine. 2003;21:38–42. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4666(02)00485-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: Basic science and clinical progress. Endocr. Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carmeliet P. VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology. 2005;69:4–10. doi: 10.1159/000088478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hochstein A., Bhatia A. Collagen: Its role in wound healing. Wound Manag. 2014;4:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brett D. A review of collagen and collagen-based wound dressings. Wounds. 2008;20:347–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pizzimenti S., Toaldo C., Pettazzoni P., Dianzani M.U., Barrera G. The “two-faced” effects of reactive oxygen species and the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal in the hallmarks of cancer. Cancers. 2010;2:338–363. doi: 10.3390/cancers2020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siwik D.A., Pagano P.J., Colucci W.S. Oxidative stress regulates collagen synthesis and matrix metalloproteinase activity in cardiac fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C53–C60. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.1.C53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez-Menocal L., Shareef S., Salgado M., Shabbir A., Van Badiavas E. Role of whole bone marrow, whole bone marrow cultured cells, and mesenchymal stem cells in chronic wound healing. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015;6:24. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh K., Agrawal N.K., Gupta S.K., Sinha P., Singh K. Increased expression of TLR9 associated with pro-inflammatory S100A8 and IL-8 in diabetic wounds could lead to unresolved inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) cases with impaired wound healing. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2016;30:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim D.-O., Chun O.K., Kim Y.J., Moon H.-Y., Lee C.Y. Quantification of polyphenolics and their antioxidant capacity in fresh plums. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:6509–6515. doi: 10.1021/jf0343074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chun O.K., Kim D.-O., Lee C.Y. Superoxide radical scavenging activity of the major polyphenols in fresh plums. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:8067–8072. doi: 10.1021/jf034740d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolliger H.R., Brenner M., Gänshirt H., Mangold H.K., Seiler H., Stahl E., Waldi D. Thin-Layer Chromatography: A Laboratory Handbook. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harikrishnan L.S., Warrier J., Tebben A.J., Tonukunuru G., Madduri S.R., Baligar V., Mannoori R., Seshadri B., Rahaman H., Arunachalam P. Heterobicyclic inhibitors of transforming growth factor beta receptor I (TGFβRI) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tramontina V.A., Machado M.A.N., Filho G.d.R.N., Kim S.H., Vizzioli M.R., Toledo S. Effect of bismuth subgallate (local hemostatic agent) on wound healing in rats. Histological and histometric findings. Braz. Dent. J. 2002;13:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hummon A.B., Lim S.R., Difilippantonio M.J., Ried T. Isolation and solubilization of proteins after TRIzol® extraction of RNA and DNA from patient material following prolonged storage. Biotechniques. 2007;42:467–472. doi: 10.2144/000112401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alsenani F., Ashour A.M., Alzubaidi M.A., Azmy A.F., Hetta M.H., Abu-Baih D.H., Elrehany M.A., Zayed A., Sayed A.M., Abdelmohsen U.R. Wound Healing Metabolites from Peters’ Elephant-Nose Fish Oil: An In Vivo Investigation Supported by In Vitro and In Silico Studies. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:605. doi: 10.3390/md19110605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alzarea S.I., Elmaidomy A.H., Saber H., Musa A., Al-Sanea M.M., Mostafa E.M., Hendawy O.M., Youssif K.A., Alanazi A.S., Alharbi M. Potential anticancer lipoxygenase inhibitors from the red sea-derived brown algae sargassum cinereum: An in-silico-supported In-Vitro Study. Antibiotics. 2021;10:416. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10040416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He M.M., Smith A.S., Oslob J.D., Flanagan W.M., Braisted A.C., Whitty A., Cancilla M.T., Wang J., Lugovskoy A.A., Yoburn J.C. Small-molecule inhibition of TNF-α. Science. 2005;310:1022–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.1116304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hassan H., Abdel-Aziz A. Evaluation of free radical-scavenging and anti-oxidant properties of black berry against fluoride toxicity in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48:1999–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sonboli A., Mojarrad M., Ebrahimi S.N., Enayat S. Free Radical Scavenging Activity and Total Phenolic Content of Methanolic Extracts from Male Inflorescence of Salix aegyptiaca Grown in Iran. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. IJPR. 2010;9:293–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.