Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Federal and state governments implemented temporary strategies for providing access to opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Advocates hope many of these policies become permanent because of their potential to expand access to care.

OBJECTIVE

To consider the multitude of ways access to and utilization of treatment for individuals with OUD might have been expanded by state and federal policy so researchers can do a better job evaluating the effectiveness of specific policy approaches, which will depend on the interaction with other state policies.

EVIDENCE REVIEW

We summarize state-level policy data reported by government and nonprofit agencies that track health care regulations, specifically the Kaiser Family Foundation, Federation of State Medical Boards, American Association of Nurse Practitioners, American Academy of Physician Assistants, and the National Safety Council. Data were collected by these sources from September 2020 through January 2021. We examine heterogeneity in policy elements adopted across states during the COVID-19 pandemic in 4 key areas: telehealth, privacy, licensing, and medication for opioid use disorder. The analysis was conducted from March 2020 through January 2021.

FINDINGS

This cross-sectional study found that federal and state governments have taken important steps to ensure OUD treatment availability during the COVID-19 pandemic, but few states are comprehensive in their approach. Although all states and Washington, DC have adopted at least 1 telehealth policy, only 17 states have adopted telehealth policies that improve access to OUD treatment for new patients. Furthermore, only 9 states relaxed privacy laws, which influence the ability to use particular technology for telehealth visits. Similarly, all states have adopted at least 1 policy related to health care professional licensing permissions, but only 35 expanded the scope of practice laws for both physician assistants and nurse practitioners. Forty-four states expanded access to initiation and delivery of medication for OUD treatment. Together, no state has implemented all of these policies to comprehensively expand access to OUD treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

With considerable policy changes potentially affecting access to treatment and treatment retention for patients with OUD during the pandemic, evaluations must account for the variation in state approaches in related policy areas because the interactions between policies may limit the potential effectiveness of any single policy approach.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severely disrupted critical treatment and recovery supports for individuals with opioid and other substance use disorders (SUD), even as more than 93 000 Americans were dying from drug poisonings.1 Shelter-in-place orders led to reduced social support, disruptions to work or job loss, and increased psychological distress.2,3 These factors can exacerbate substance misuse and increase risk of relapse for those in recovery. Early evidence shows that substance misuse, including opioid use disorders (OUD), increased during the pandemic.4,5

To manage the health care crisis caused by COVID-19, state and federal policies were adopted to improve access to health care in general, many of which addressed specific barriers to SUD/OUD treatment access and utilization such as inadequate geographic access to providers and evidence-based therapies.6,7 Research has begun examining the effect of telehealth policies, which have been instrumental in expanding access to providers, but changes in other policies are also relevant for understanding how much telehealth allowances improve access to treatment, including privacy requirements, licensing requirements, and rules regarding prescribing medications for OUD (MOUD) treatment.6,8,9 These areas of policy can interact with telehealth policies and influence their overall effect.

The goal of this cross-sectional study is to inform researchers of the range of state and federal policies that may affect access to and utilization of SUD treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic, some of which are not narrowly focused on SUD treatment but are still relevant if researchers intend to conduct robust evaluations of a given policy’s effect. We reviewed federal and state policy changes implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic that address important barriers in access to effective SUD/OUD treatment raised in the literature,9–14 namely (1) coverage, delivery, and payment of telehealth, (2) management of consent, privacy, and security requirements, (3) licensing requirements, and (4) initiation and dispensing of medication. We describe the heterogeneity across states in each of these 4 policy areas, and examine through the example of telehealth, how particular combinations of policies across the 4 domains might limit or expand the reach of policies in this area. We conclude that researchers examining the effectiveness of any singular policy approach will need to consider the broader policy environment to properly evaluate effectiveness of any single policy.

Methods

Although a number of COVID-19 policy databases exist, these databases either narrowly focus on particular patients, clinicians, medications, or types of facilities, providing a fragmented view of access to SUD treatment, or they are overly general and apply to health care or prescriptions broadly, providing no guidance about which policies are relevant to SUD and OUD treatment, which fall under additional federal regulations. Following best practices in public health law methods,15 we began with a conversation among our interdisciplinary team of experts to identify potentially relevant policy domains that could influence known barriers to SUD treatment access, utilization, and retention, namely cost, privacy, and access to effective treatment and medications.9–14 We then conducted a review of the literature11,16,17 of the effect of COVID-19 policies on SUD and OUD treatment access, utilization, and retention. This review led us to the conceptualization of 4 interrelated health policy domains that influence the effectiveness of specific COVID-19 policies (1) coverage, delivery, and payment of telehealth, (2) management of consent, privacy, and security requirements, (3) licensing requirements, and (4) initiation and dispensing of medication. This study was not reviewed by any institutional review board because it did not involve human participants, but rather existing state policies in the public domain.

To identify laws and regulations within these policy domains affecting patients, we reviewed key government and nonprofit agencies that track health care statutes and regulations, specifically the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF),18 Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB),19 American Association of Nurse Practitioners,20 American Academy of Physician Assistants,21 and the National Safety Council.22 We identified these sources through ongoing work conducted by the RAND-USC Schaeffer Opioid Policy Tools and Information Center of Excellence, an NIDA-funded P50 Research Center whose researchers regularly scan government and nonprofit agency webpages reporting on state legislation, regulation, and executive directives targeting the delivery of OUD treatment services and other policies minimizing harm from opioids. Data on state policies identified through these sources were collected from September 2020 through January 2021.

While several agencies report selective information on policies implemented or changed during the COVID-19 pandemic for particular patient populations, none comprehensively consider policies specific to SUD and/or OUD treatment across all 4 domains and all types of patients. This study makes its contribution by considering how specific and broad COVID-19 health policies combine to determine the full policy environment for public and private patients seeking or receiving SUD or OUD treatment specifically.

Results

Coverage, Delivery, and Payment for Telehealth

At the onset of the pandemic, federal and state governments quickly authorized increased reimbursement and coverage for telehealth services, including audio services, synchronous audiovisual, or asynchronous methods. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, this mode of delivery for SUD treatment had been underutilized compared with other psychiatric services23 due to technological requirements, privacy concerns, and cost.24 Through the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act and the Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allowed telehealth reimbursement at levels similar to in-person visits for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries.25 In addition, CMS also waived restrictions on Medicare coverage, permitting service delivery to those living outside of rural areas, and allowed delivery via smartphones.26 Through its Interim Final Rule, CMS further allowed clinicians to evaluate Medicare beneficiaries with audio phones only,27 a provision later broadened to include many behavioral health services.28

Within Medicaid, CMS issued guidance29 permitting state programs more flexibility in determining coverage for telehealth,30 leading many states to allow for reimbursement of telehealth services in Medicaid plans.19,26 Several commercial insurers followed suit.31 Finally, the Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General issued a policy statement32 providing physicians and other practitioners serving federal health care program beneficiaries the flexibility to reduce or waive cost sharing for telehealth visits due specifically to COVID-19.

Using emergency orders, states expanded service and payment requirements for those providing commercial and state public health insurance, including provisions specifically targeting SUD therapies. As shown in the Table,18,19,22,33,34 as of September 2020, nearly all states passed laws requiring benefit coverage for behavioral health telehealth services. Twenty-two states waived requirements for a preexisting patient-provider relationship, and 41 states waived requirements for a prior in-person evaluation. Only 17 states facilitated behavioral health telehealth services by adopting all 3 policies. In addition, nearly all states and Washington, DC have allowed providers to conduct audio-only consultations.19 Responding to these state initiatives, many large private insurers expanded coverage of telehealth services to encompass audio-only communication.31

Table.

State Policies Related to Coverage, Delivery, and Payment of Telehealth During COVID-19

| State | Coverage and delivery | Payment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telehealth coverage for behavioral health (September 2020) | Waiver of requirement (December 2020) | Reimbursement parity for telehealth and in-person services [private insurance] (January 2021) | Payment parity for at least some telehealth services compared to face-to-face services [Medicaid] (January2021) | Payment parity for mental health via telehealth (September 2020) | |||

| For established clinician-patient relationship for telehealth | For prior in-person contact for telehealth (December 2020) | Private insurance | Medicaid | ||||

| Total | 46 States plus Washington, DC | 22 States | 41 States | 17 States | 42 States plus Washington, DC | 15 States | 17 States |

| AL | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| AK | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| AZ | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| AR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| CA | Y | N | Ya | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| CO | Y | Y | Ya | N | Y | Y | N |

| CT | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| DE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| DC | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N |

| FL | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| GA | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N |

| HI | Y | Y | Ya | N | Y | Y | N |

| ID | Y | Y | Ya | N | Y | N | N |

| IL | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| IN | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| IA | Y | Y | Ya | Y | Y | N | Y |

| KS | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N |

| KY | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| LA | Y | Y | Ya | N | N | N | N |

| ME | Y | N | Ya | Y | Y | N | Y |

| MD | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| MA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| MI | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N |

| MN | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| MS | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| MO | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| MT | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| NE | Y | N | Ya | N | Y | N | N |

| NV | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| NH | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| NJ | Y | Y | Yb | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| NM | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| NY | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| NC | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| ND | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| OH | Y | Y | Yb | N | N | N | N |

| OK | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N |

| OR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| PA | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| RI | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| SC | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| SD | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| TN | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| TX | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| UT | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N |

| VT | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| VA | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N |

| WA | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| WV | Y | Yc | Y | N | N | N | N |

| WI | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N |

| WY | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N |

Policy existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Restrictions apply.

Policy applies only for patients with COVID-19.

As of December 2020, 17 states required telehealth visits within commercial insurance to be paid at the same rate as analogous in-person services (ie, “payment parity”), compared with 42 states and Washington, DC for Medicaid (Table, columns 4–5).18 Fifteen states further required payment parity for commercially covered mental health telehealth visits, and 17 states established the same for Medicaid (Table, columns 6–7).22 Only 8 states required payment parity for mental health telehealth services for both those with Medicaid and the privately insured.

Managing Consent, Privacy, and Security

Telehealth services must comply with a range of federal and state privacy laws. The 1996 Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) limits disclosure of personal health information by health care professionals to narrowly defined circumstances, and mandates that the technology used be secure against reasonably anticipated threats. Records from federally assisted SUD treatment programs are provided additional privacy protections under 42 CFR Part 2, which requires that patients provide detailed, specific written consent to disclose their records.35 These policies have sharply limited the platforms available for telehealth and slowed development in the use of telehealth for SUD treatment.36,37

Although HHS released a notice on March 17, 2020, stating that they would not enforce HIPAA rules against clinicians and therapists using private communication services such as Facetime to provide telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic,38 many states have stricter privacy laws than those provided by the federal government, imposing additional barriers to telehealth services and generating a confusing regulatory patchwork.39 According to KFF,26 only 9 states (Alabama, Delaware, California, Georgia, Maine, Maryland, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Utah) relaxed their state-level privacy laws to facilitate telehealth as of May 2020. Of these, state Medicaid programs in Alabama, Delaware, Georgia, and Maine specifically waived their requirements for providers to obtain written consent from patients prior to conducting a telehealth consultation, requiring only verbal consent instead.26

Licensing Requirements

Shortages of licensed SUD treatment programs and physicians were a problem well before the COVID-19 pandemic.12,14 Although addiction specialty physicians exist, only opioid treatment programs (OTPs) can provide psychological and medical services for OUD, and they face rigorous federal requirements40 to administer or dispense MOUD, causing shortages of licensed facilities in many areas.14 Persistent workforce barriers have further contributed to the lack of qualified personnel who can provide office-based treatment.41,42 The 2016 Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act43 allowed physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) to obtain buprenorphine prescribing waivers in addition to physicians; however, they must act within federal laws to prescribe buprenorphine and the scope of practice regulations established by their state. State scope of practice regulations limiting the circumstances under which these practitioners can prescribe—for example, by requiring collaboration with a physician—may undercut the effectiveness of these provisions, particularly in rural areas.8,9 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, only 19 states and Washington, DC provided NPs with full practice authority and only 5 states waived PA practice agreements, allowing them to initiate and manage treatment, and prescribe medications.20,21

During the COVID-19 pandemic, states adjusted their NP and PA licensing requirements and scope of practice laws to expand capacity to provide care for patients with COVID-19. First, state-permitted service activities were expanded, occasionally with increased prescribing privileges. Second, many states waived restrictions on clinicians licensed out-of-state or whose license had recently lapsed owing to retirement. The federal government adopted similar provisions for those treating the publicly insured. In addition, CMS waived previous limitations to allow NPs, PAs, and other professionals to provide services to Medicare beneficiaries via telehealth.28

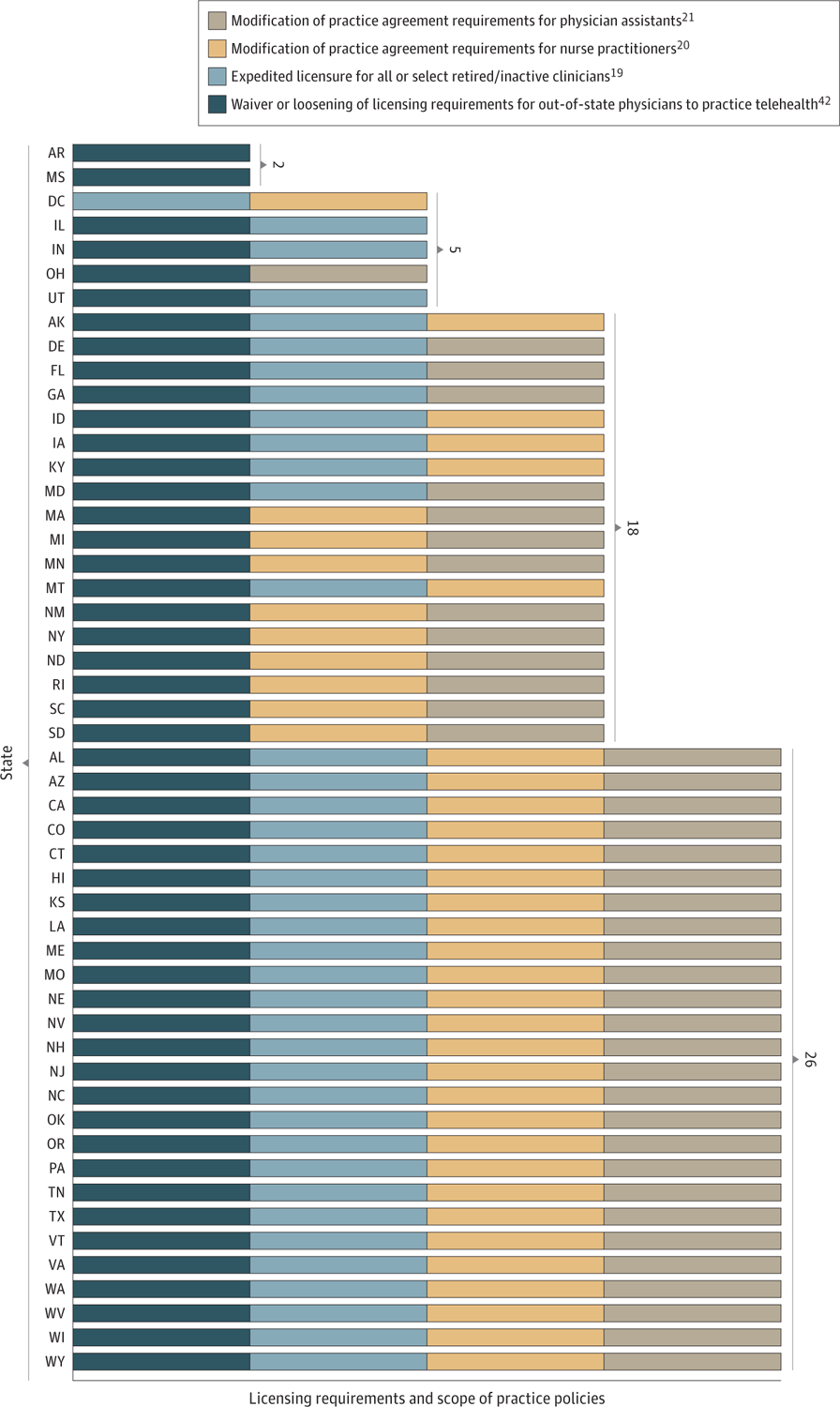

By December 2020, all 50 states relaxed their licensing laws to allow out-of-state clinicians to practice in their state33 (Figure 1), but policies in Alabama, California, New Jersey, and Tennessee only applied for patients with COVID-19 (and hence would not expand access for those suffering from SUD and/or OUD). Thirty-eight states and Washington, DC had expedited licensing for all or select inactive or retired clinicians.19 Forty states expanded scope of practice laws for PAs to allow for expanded prescribing privileges and treatment outside of telehealth, with only New Mexico and South Dakota restricting this to patients with COVID-19.21 Forty-one states and Washinton, DC expanded prescribing privileges and treatment outside of telehealth for NPs, with only Maine’s policy restricted to patients with COVID-19.20

Figure 1.

State Licensing Requirements and Scope of Practice Policies During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Initiation and Dispensing of Medication

The federal and state regulations governing the prescribing and dispensing of MOUD differ considerably from those of other medical prescriptions.40 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, federal law mandated that methadone could only be prescribed and dispensed through a state-licensed OTP. Moreover, methadone had to be dispensed on-site daily to patients. Take-home doses were only allowed under limited circumstances, and only if state law also permitted it. In addition, under the Ryan Haight Act of 2008, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) required an in-person medical evaluation before initiating any medication. Some states also imposed regulations on the prescribing of buprenorphine in office-based settings, such as requiring office-based DEA waivered clinicians to register with the state to dispense MOUD.44

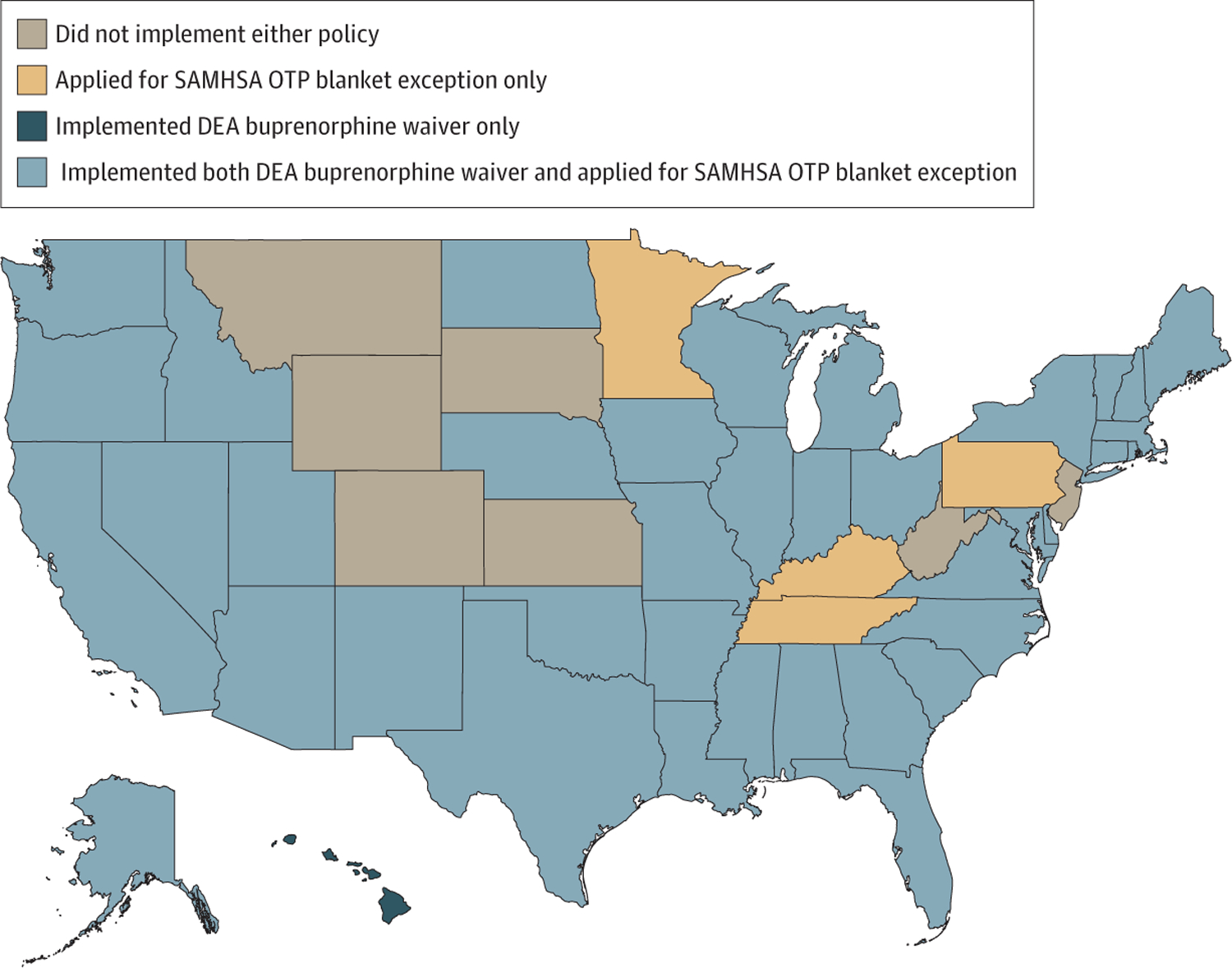

To facilitate uninterrupted OUD treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government took several steps to expand access to MOUD. For instance, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which has regulatory authority over OTPs, issued an exemption enabling clinicians practicing at OTPs to initiate buprenorphine to new patients without an in-person evaluation.45 In addition, it issued guidance encouraging states to request blanket exceptions for stable patients in OTPs to receive up to 28 days of take-home medication and less stable patients to receive up to 14 days of take-home medication for all MOUD, including methadone. Opioid treatment programs were also allowed to temporarily waive urine drug testing requirements, provide doses off-site without separate registration, and have authorized employees, law enforcement, and national guard to deliver doses at home to patients.6 As shown in Figure 2, 42 states requested these blanket exception for their OTPs.22

Figure 2.

State Implementation of Federal Policies Related to Medication for Opioid Use Disorder During COVID-19

DEA Indicates US Drug Enforcement Administration; OTP, opioid treatment program; SAMHSA, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The DEA also took steps to temporarily expand access to treatment by announcing that any DEA-waivered clinician could use telehealth, including audio-only consults, to prescribe buprenorphine without an in-person evaluation if allowed under state law.26,45 In response, 39 states and Washinton, DC issued emergency orders to enable implementation by waivered clinicians (Figure 2).22

As shown in Figure 2, although 6 states did not expand access to MOUD using either mechanism, most states chose to pursue expansion using both mechanisms. The only exceptions were 4 states (Minnesota, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania) that only applied for the SAMHSA OTP Blanket Exception (making medication available through OTPs) and Hawaii, which only pursued implementation of the DEA buprenorphine waiver.

Looking Across Policy Domains

Although numerous COVID-19 policies have been passed expanding access to SUD/OUD treatment services and medication, it is unclear the degree to which barriers have been fully removed. Given the unique requirements, licensing, and restrictions imposed on the delivery of effective SUD and/or OUD treatment, singular policies tackling 1 mode of delivery or type of clinician are rarely enough; additional hurdles likely exist.

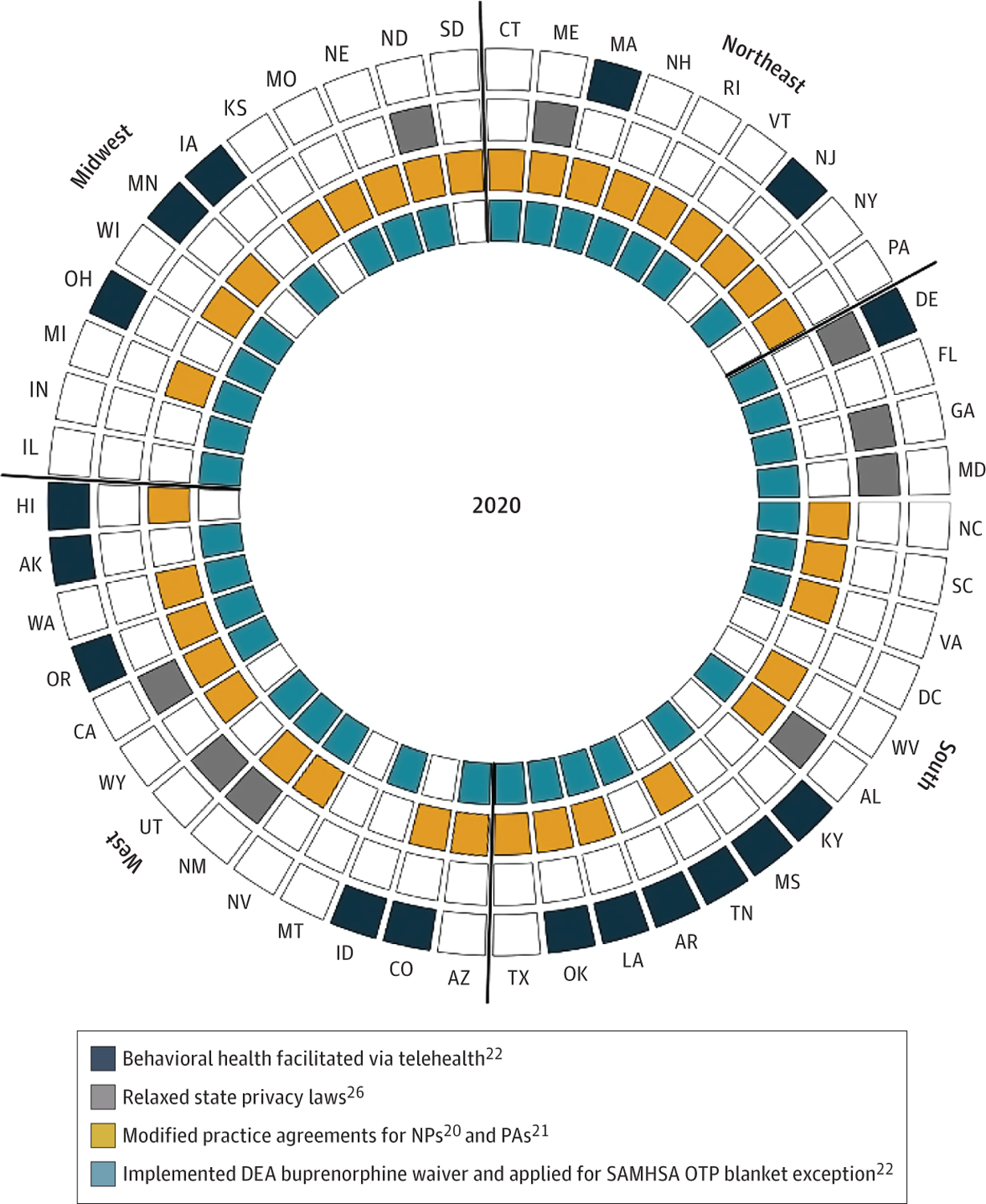

Figure 3 demonstrates this point by examining policies across domains that influence the effectiveness or reach of telehealth services. It shows in the outside circle the 17 states (in dark blue) from the Table that allowed for behavioral health telehealth, waiving requirements on prior in-person contact or established relationships. It then shows in the next layer (in gray) that only 9 states relaxed state privacy laws that might also block the use of telehealth for treatment. Whereas 35 states (in yellow) expanded practice agreements for NPs and PAs who may be more likely to take on OUD patients, these expanded scope of practice laws were not consistently adopted in states allowing telehealth services. Finally, only 38 states implemented both the DEA waiver for buprenorphine and applied for the SAMHSA blanket exception.

Figure 3.

State Policies Influencing Opioid Use Disorder Treatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic

DEA Indicates US Drug Enforcement Administration; OTP, opioid treatment program; SAMHSA, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. States in the outermost layer under the title “behavioral health facilitated via telehealth” include those that enacted all 3 of the following policies: telehealth coverage for behavioral health, waiver of requirement for established clinician-patient relationship for telehealth, and waiver of requirement for prior in-person contact for telehealth.

Notably, no state implemented policies in all 4 of these domains. The relevance of a state adopting any 1 specific policy will likely depend on the state and that policy (eg, some states may not have restrictive privacy laws needing modification). Nonetheless, researchers evaluating the effectiveness of any 1 particular COVID-19 policy will need to consider these issues of overlapping restrictions to properly consider the effectiveness of the policy they are interested in evaluating.

Discussion

Unprecedented policy changes have occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic that address significant barriers in access to effective SUD treatment, and OUD treatment in particular. Researchers and policy makers are eager to understand which policies have been effective at improving access and retention in treatment because there is a need to tackle the ongoing addiction crisis even after the pandemic ends. Services for treatment of SUD and/or OUD are delivered in a variety of settings with unique regulations, making this task difficult. It is therefore unclear the extent to which any particular policy will reduce barriers to access alone.

For example, research shows that the delivery of counseling for SUD treatment via telehealth is effective,46 but prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, underutilized.23 With as much as 40% of US counties lacking a physician authorized to prescribe buprenorphine,30 and at least 18% of people living 30 minutes or longer from the nearest OTP to access methadone,47 one would expect telehealth services to be more widely used. However, additional requirements of a preexisting clinician-patient relationship or in-person consultation prior to conducting telehealth visits, coupled with potentially restrictive state privacy laws that require direct consent, may have limited their use. Moreover, it is unclear whether weakening of strict privacy laws, which also reduce confidentiality protections,48 will discourage treatment persistence for those who value privacy. This trade-off will be important to understand before we can understand the incremental effect of these policies on outcomes.

It seems likely that the increased flexibility for health care professionals to initiate and provide evidence-based medications to patients with OUD may improve uptake and retention in treatment,49 particularly when combined with expanded licensing privileges to practice telehealth. Similarly, expansion of scope of practice laws targeting NPs and PAs, who are more likely to deliver care in rural areas, will likely improve treatment uptake and retention.8,9 These policies, however, are most likely to be effective when coupled with policies that retain at-home access to effective MOUD.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this analysis. In particular, although our analysis considered enacted policies that may have affected SUD and/or OUD treatment access during the COVID-19 pandemic, they provide no information about the implementation of these policies. As a result, the data we have described may not reflect policies in practice. Concerns regarding implementation are compounded by the relevance of both federal and state laws in the delivery of SUD treatment. Although the sharing of public health authority is meant to allow for coordination and customization of policies to the local context, differing policy perspectives can create conflict between federal and state governments. Thus, it is even more important for researchers to consider whether overlapping federal and state SUD and/or OUD policies may have a greater effect than polices enacted by federal or state actors alone. The research is further limited to its focus on policies already collected by various agencies. We did not conduct our own legal analysis of relevant policies, and thus it is possible that additional state policies are important to consider when evaluating the effectiveness of particular COVID-19 emergency policies.

Conclusions

Despite unprecedented policy changes in rules regarding the delivery of SUD services during the COVID-19 pandemic, drug overdose data indicate that substance use, particularly opioid use, still rose.1 Early evidence evaluating access to buprenorphine during the COVID-19 pandemic supports the belief that telehealth can increase access to OUD treatment. The number of people filling buprenorphine prescriptions has remained constant, whereas use of other prescriptions has decreased.50 Careful evaluations of these policies will need to consider additional policies that were also changed within the state environment during this period. Although the federal government has been the leader in expanding access to OUD clinicians and medications, individuals with Medicaid and commercial insurance require additional state actions to benefit from these federal allowances.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dr Pessar reported grants from National Institute on Drug Abuse Abuse (P50DA046351) during the conduct of the study. Dr Ge reported grants from National Institute on Drug Abuse (P50DA046351) during the conduct of the study. Dr Smart reported grants from National Institute on Drug Abuse P50DA046351 during the conduct of the study. Dr Pacula reported grants from National Institute on Drug Abuse during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support:

All authors prepared this article with support through a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to the Opioid Policy Tools and Information Center (OPTIC) of Excellence (P50DA046351).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

NIDA had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions:

We thank our colleagues Brad Stein, PhD, (RAND Corporation) and Susan Ridgely, JD (RAND Corporation) for their helpful insights and comments. These individuals did not receive compensation for their contributions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. 2021. Accessed September 26, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- 2.Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson E, Daly M. Explaining the rise and fall of psychological distress during the COVID-19 crisis in the United States: longitudinal evidence from the Understanding America Study. Br J Health Psychol. 2021;26(2):570–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linas BP, Savinkina A, Barbosa C, et al. A clash of epidemics: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic response on opioid overdose. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;120:108158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson J. CDC warns of surge in drug overdose deaths during COVID-19. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2:e210001–e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieberman A, Davis C, Samuels E, Weinstein Z, Vincent L. Increased Access to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder during the COVID-19 Epidemic and Beyond. The Network for Public Health Law; 2020. Accessed December 20, 2020. www.networkforphl.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/7-23-2020-Webinar-Slides.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khatri Utsha, Davis Corey S., Krawczyk Noa, Lynch Michael, Berk Justin, Samuels. These Key Telehealth Policy Changes Would Improve Buprenorphine Access While Advancing Health Equity. Health Affairs Blog: Health Affairs; 2020. Accessed December 20, 2020. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200910.498716/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett ML, Lee D, Frank RG. In rural areas, buprenorphine waiver adoption since 2017 driven by nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(12):2048–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spetz J, Toretsky C, Chapman S, Phoenix B, Tierney M. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant waivers to prescribe buprenorphine and state scope of practice restrictions. JAMA. 2019;321(14):1407–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin AM, Bynum JPW, Maust DT, Gottlieb DJ, Meara E. Long-term implications of a short-term policy: redacting substance abuse data. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):975–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis CS, Samuels EA. Opioid policy changes during the COVID-19 pandemic-and beyond. J Addict Med. 2020;14(4):e4–e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dick AW, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, et al. Growth in buprenorphine waivers for physicians increased potential access to opioid agonist treatment, 2002–11. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):1028–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen Y, Sharfstein JM. Confronting the stigma of opioid use disorder—and its treatment. JAMA. 2014;311(14):1393–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sigmon SC. Access to treatment for opioid dependence in rural America: challenges and future directions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(4):359–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tremper C, Thomas S, Wagenaar AC. Measuring law for evaluation research. Eval Rev. 2010;34(3):242–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priest KC. The COVID-19 pandemic: practice and policy considerations for patients with opioid use disorder. Health Affairs Blog. 2020; 10. Accessed July 26, 2021. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200331.557887/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terry N, Goldstein M, Nahra K. COVID-19: Substance Use Disorder, Privacy, And The CARES Act. Health Affairs Blog. 2020. Accessed March 25, 2021. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200605.571907/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.State COVID-19 Data and Policy Actions. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020. https://www.kff.org/report-section/state-covid-19-data-and-policy-actions-policy-actions/#telehealth [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. States and Territories Modifying Requirements for Telehealth in Response to COVID-19. Federation of State Medical Boards, 2020. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/pdf/states-waiving-licensure-requirements-for-telehealth-in-response-to-covid-19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.COVID-19 State Emergency Response: Temporarily Suspended and Waived Practice Agreement Requirements. American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 2020. December 15, 2020. www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/covid-19-state-emergency-response-temporarily-suspended-and-waived-practice-agreement-requirements [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suspended/Waived Practice Requirements. American Academy of Physician Assistants, 2020. December 15, 2020. www.aapa.org/news-central/covid-19-resource-center/covid-19-state-emergency-response/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Safety Council. State of the Response: State Actions to Address the Pandemic Report Methodology, pgs. 8–11, 2020. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.nsc.org/getmedia/10cf1e25-92af-4caa-b5c1-b22114468cf1/state-response-report-methodology.pdf

- 23.Huskamp HA, Busch AB, Souza J, et al. How is telemedicine being used in opioid and other substance use disorder treatment? Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(12):1940–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughto JMW, Peterson L, Perry NS, et al. The provision of counseling to patients receiving medications for opioid use disorder: telehealth innovations and challenges in the age of COVID-19. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;120:108163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2021. www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weigel G, Ramaswamy A, Sobel L, Salganicoff A, Cubanski J, Meredith F. Opportunities and Barriers for Telemedicine in the U.S. During the COVID-19 Emergency and Beyond. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020. Accessed May 11, 2020. www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/opportunities-and-barriers-for-telemedicine-in-the-u-s-during-the-covid-19-emergency-and-beyond/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Trump Administration Makes Sweeping Regulatory Changes to Help U.S. Healthcare System Address COVID-19 Patient Surge. 2020. Accessed December 20, 2020. www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/additional-backgroundsweeping-regulatory-changes-help-us-healthcare-system-address-covid-19-patient

- 28.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Trump Administration Issues Second Round of Sweeping Changes to Support U.S. Healthcare System During COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Accessed December 20, 2020. www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-issues-second-round-sweeping-changes-support-us-healthcare-system-during-covid

- 29.COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for State Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Agencies. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/downloads/covid-19-faqs.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanco C, Compton WM, Volkow ND. Opportunities for research on the treatment of substance use disorders in the context of COVID-19. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Health Insurance Providers Respond to Coronavirus (COVID-19). America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP); 2020. Accessed March 20, 2021. www.ahip.org/health-insurance-providers-respond-to-coronavirus-covid-19/

- 32.OIG Policy Statement Regarding Physicians and Other Practitioners That Reduce or Waive Amounts Owed by Federal Health Care Program Beneficiaries for Telehealth Services During the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak In: General HaHSOoI, ed.2020. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/special-advisory-bulletins/960/policy-telehealth-2020.pdf

- 33.State-by-State Chart of COVID Telehealth Waivers. Federation of State Medical Boards, 2020. Accessed December 31, 2020. https://www.fsmb.org/provider-pass/SysSiteAssets/pdf/state-by-state-emergency-telehealth-information.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medicaid Emergency Authority Tracker: Approved State Actions to Address COVID-19. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/medicaid-emergency-authority-tracker-approved-state-actions-to-address-covid-19/#note-1-12 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bossenbroek MD. Thirty years in the making: 42 CFR Part 2 revisited and revised. Health Lawyer. 2016; 29(6):1. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spivak S, Strain EC, Cullen B, Ruble AAE, Antoine DG, Mojtabai R. Electronic health record adoption among US substance use disorder and other mental health treatment facilities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;220:108515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghitza UE, Sparenborg S, Tai B. Improving drug abuse treatment delivery through adoption of harmonized electronic health record systems. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2011;2011(2):125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Services HaH. OCR Announces Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency. Health and Human Services; 2020. Accessed March 20, 2021. www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman DA. Increasing access to care: telehealth during COVID-19. J Law Biosci. 2020;7(1):a043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis CS, Carr DH. Legal and policy changes urgently needed to increase access to opioid agonist therapy in the United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;73:42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haffajee RL, Bohnert ASB, Lagisetty PA. Policy pathways to address provider workforce barriers to buprenorphine treatment. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6)(suppl 3):S230–S242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walley AY, Alperen JK, Cheng DM, et al. Office-based management of opioid dependence with buprenorphine: clinical practices and barriers. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1393–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants Provision of Medication-Assisted Treatment. Scope of Practice Policy, 2017. Accessed December 11, 2020. http://scopeofpracticepolicy.org/nurse/nurse-practitioners-physician-assistants-provision-medication-assisted-treatment/ [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System. Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.pdaps.org/

- 45.Prevoznik TW. Letter to DEA Qualifying Practitioners and Other Practitioners, 2020. Drug Enforcement Administration. March 31, 2020. Accessed December 20, 2020. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-022)(DEA068)%20DEA%20SAMHSA%20buprenorphine%20telemedicine%20%20(Final)%20+Esign.pdf?mc_cid=8dffbfc637&mc_eid=d4494a732e [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin LA, Casteel D, Shigekawa E, et al. Telemedicine-delivered treatment interventions for substance use disorders: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;101:38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleinman RA. Comparison of driving times to opioid treatment programs and pharmacies in the US. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(11):1163–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knopf A. CARES Act eliminates most of 42 CFR Part 2. Alcoholism & Drug Abuse Weekly 2020;32:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Onofrio G, Venkatesh A, Hawk K. The adverse impact of COVID-19 on individuals with OUD highlights the urgent need for reform to leverage emergency department–based treatment. Nejm Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery 2020. doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen TD, Gupta S, Ziedan E, et al. Assessment of filled buprenorphine prescriptions for opioid use disorder during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):562–565. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]