Abstract

Simple Summary

Guidelines recommend early initiation of palliative care (PC) for patients with advanced cancers. Central nervous system (CNS) malignancies pose particular challenges for patients, who benefit from supportive care services such as PC, home health, and social work support. We analyze a cohort of privately insured patients with malignant brain or spinal tumors from the Optum Clinformatics Datamart Database to investigate health disparities in supportive care service access and utilization. We introduce a novel construct, “provider patient racial diversity index” (provider pRDI), the proportion of non-white minority patients a provider encounters to approximate a provider’s patient demographics and suggest a provider’s exposure to diversity. Our manuscript adds to existing literature on patient-level health disparities and provides a platform for future research focused on provider-level quality improvement interventions for utilization of supportive care services.

Abstract

Patients with primary or secondary central nervous system (CNS) malignancies benefit from utilization of palliative care (PC) in addition to other supportive services, such as home health and social work. Guidelines propose early initiation of PC for patients with advanced cancers. We analyzed a cohort of privately insured patients with malignant brain or spinal tumors derived from the Optum Clinformatics Datamart Database to investigate health disparities in access to and utilization of supportive services. We introduce a novel construct, “provider patient racial diversity index” (provider pRDI), which is a measure of the proportion of non-white minority patients a provider encounters to approximate a provider’s patient demographics and suggest a provider’s cultural sensitivity and exposure to diversity. Our analysis demonstrates low rates of PC, home health, and social work services among racial minority patients. Notably, Hispanic patients had low likelihood of engaging with all three categories of supportive services. However, patients who saw providers categorized into high provider pRDI (categories II and III) were increasingly more likely to interface with supportive care services and at an earlier point in their disease courses. This study suggests that prospective studies that examine potential interventions at the provider level, including diversity training, are needed.

Keywords: health inequities, brain cancer, spinal tumor, advanced cancer, racial diversity, palliative care, home health

1. Introduction

Palliative care (PC) is defined as a critical service with the purpose of alleviating serious health-related suffering [1]. Social work services and home health agency services provide much-needed support beyond PC for patients with difficult cancer diagnoses and their families [2,3,4,5]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends that patients with advanced cancer receive interdisciplinary and dedicated PC concurrent with active cancer care early in their disease courses [6]. According to ASCO, advanced cancer is defined as late-stage, distant metastases, or life-limiting with a prognosis of 6–24 months [6]. Usage of PC and related supportive services, such as home health and social work support, contributes to high-quality oncologic care.

Central nervous system (CNS) malignancies pose particular challenges for patients. Metastatic cancers may spread to the brain or spine, impacting function and quality of life. Glioblastoma (GBM) and other high-grade gliomas, such as astrocytoma or gliosarcoma, are commonly diagnosed primary brain malignancies in adults. While high-grade gliomas such as WHO Grade III anaplastic astrocytoma carry an approximate median survival time of 2–5 years, GBM, in particular, has a poor prognosis with a median overall survival of 16–21 months [7,8,9]. Historically, patients with brain metastases were precluded from participating in clinical trials due to presumed poor prognosis [10].

Despite national guidelines and recommendations, there are disparities in access to PC and other valuable supportive services among patients with advanced cancer, including those diagnosed with CNS malignancies. Retrospective studies on advanced cancers have identified racial minority background as a marker of poorer healthcare utilization and outcomes [11,12]. A recent national study also examined outcomes at the facility level by comparing minority-serving hospitals, with higher proportions of Black and Hispanic patients, to non-minority serving hospitals [13]. Unfortunately, minority-serving hospitals were significantly less likely to refer minority patients with metastatic cancer to PC, highlighting systemic problems underlying racial disparities [13].

We explore potential areas of healthcare quality improvement by creating a novel variable, “provider patient racial diversity index” (provider pRDI), which is defined by the proportion of non-white minority patients seen by a provider. The variable not only acts as a proxy for a provider’s practice and locale demographics but may offer insight into the level of cultural sensitivity of providers who demonstrate higher provider pRDI. We relied on the Optum Clinformatics Datamart Database (Optum) to construct a cohort of privately insured neurosurgical patients from all backgrounds who were diagnosed with a malignant CNS tumor. We aimed to (1) identify key modifiers of referral to and utilization of PC and supportive services, such as home health and social work; (2) investigate the impact of provider pRDI on supportive care utilization and referral timing; and (3) provide context for future necessary studies on healthcare inequities and potential provider-level quality improvement initiatives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

All data used in this study was derived from Optum 2003–2021, which we have previously described and covers the healthcare claims of over 100 million enrollees. It includes the longitudinal healthcare service claims billed by providers in both inpatient and outpatient settings, which can be queried by provider class, setting, service type (as categorized by the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) system), and diagnosis (as indicated by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system). All services were linked to encrypted provider and enrollee identifiers. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (#62056).

2.2. Cohort Design

All patients with at least one neurosurgery encounter (defined as a billed claim by a neurosurgeon) with a diagnosis of a malignant primary or secondary CNS tumor and no prior evidence of PC (defined as a billed claim by palliative or hospice care) were included in our study. The index diagnosis date was defined as the first qualifying tumor diagnosis code. At least 30 days of pre-index lookback, which was used for canvassing documented medical comorbidities, was required for study inclusion. Comorbidities were included based on the Elixhauser comorbidity index [14]. Other medical covariates included tumor etiology (primary versus metastatic) and receipt of surgery during the period of follow-up. Supportive care services were defined based on claims filed PC or hospice care providers. Similarly, social work services and home health services were identified based on provider categorization on each individual claim.

Patient-level demographics such as age, sex, and race were included in all analyses. Additionally, healthcare plans were categorized as Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO), indemnity (IND), other (OTH), point-of-service (POS). We further sought to understand markers of physician exposure to patient diversity and overall cultural sensitivity. To do so, we defined a novel metric termed provider pRDI, which categorizes healthcare providers as category I, II, or III where increasing indices correlate with increasing exposure to patients of minority races. To estimate provider pRDI, we extracted all inpatient and outpatient services billed by each anonymized provider and mapped them to anonymized patients. From this, we estimated the fraction of patients served by each provider that were of a minority race to which a priori defined thresholds were applied. Specifically, providers whose patient population were less than 30%, between 30% and 49%, and over 50% minority race were termed “category I”, “category II”, and “category III” providers, respectively.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The primary outcomes-of-interest were timing of supportive care services relative to initial tumor diagnosis and to documented death date. Other outcomes evaluated included incidence of supportive services as well as total utilization of these services based on healthcare spending. Multivariable mixed effects Cox, logistic, and linear regression were used to evaluate incidence of care initiation, incidence of utilization, and cumulative costs, respectively. Propensity score matching was used to generate matched cohorts balanced for demographics and comorbidities and conducted in a 1:1:1 approach using a greedy matching algorithm. Covariate balance was evaluated by computing standardized mean differences (SMD). All analyses were conducted in The R Project for Statistical Computing, version 4.0.0 (R Core Team, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA)

3. Results

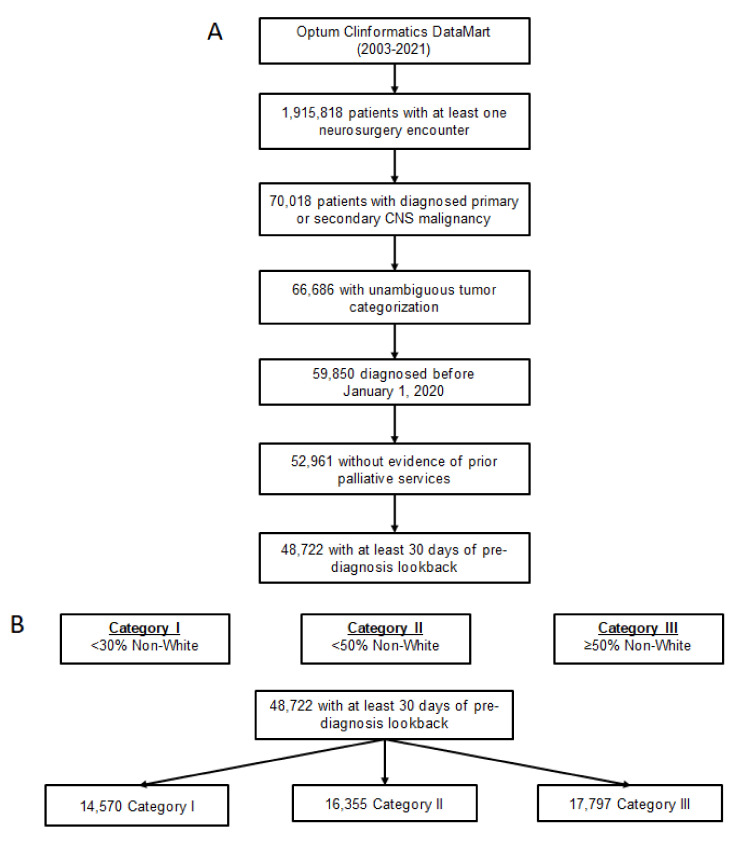

In total, 48,722 patients met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Full cohort characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Notably, the number of secondary malignancies (N = 23,554) was nearly equal to the number of primary malignancies (N = 25,168). Additionally, the distribution of provider pRDI was nearly even, with 14,570 patients qualifying under category I (29.9%), 16,355 under category II (33.6%), and 17,797 under category III (36.5%).

Figure 1.

Cohort flowchart and provider patient racial diversity index. (A) Flowchart of neurosurgical patients with central nervous system (CNS) malignancies included for analysis, derived from Optum 2003–2021. (B) Designation and breakdown of provider patient racial diversity index categories.

Table 1.

Unmatched and matched cohort characteristics.

| Unmatched Cohort Characteristics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Category 1 (N = 14,570) |

Category 2 (N = 16,355) |

Category 3 (N = 17,797) |

SMD (0 vs. 1) |

SMD (0 vs. 1) |

|||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Year of Diagnosis | 2013.77 | 4.77% | 2011.01 | 4.47% | 2011.83 | 4.52% | 0.597 | 0.417 |

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | 61.31 | 16.2% | 58.56 | 21.16% | 60.83 | 14.83% | 0.146 | 0.031 |

| Sex | 0.044 | 0.075 | ||||||

| Female (ref) | 7146 | 49% | 8385 | 51.3% | 9399 | 52.8% | ||

| Male | 7424 | 51% | 7970 | 48.7% | 8398 | 47.2% | ||

| Race | 0.105 | 0.582 | ||||||

| White (ref) | 12,635 | 86.7% | 14,671 | 89.7% | 11,156 | 62.7% | ||

| Asian | 284 | 1.9% | 249 | 1.5% | 874 | 4.9% | ||

| Black | 806 | 5.5% | 812 | 5% | 3453 | 19.4% | ||

| Hispanic | 845 | 5.8% | 623 | 3.8% | 2314 | 13% | ||

| Tumor Type | 0.498 | 0.564 | ||||||

| Primary (ref) | 10,128 | 69.5% | 7466 | 45.6% | 7574 | 42.6% | ||

| Secondary | 4442 | 30.5% | 8889 | 54.4% | 10,223 | 57.4% | ||

| Insurance Plan | 0.48 | 0.203 | ||||||

| HMO | 3668 | 25.2% | 3136 | 19.2% | 4205 | 23.6% | ||

| EPO | 602 | 4.1% | 1208 | 7.4% | 1351 | 7.6% | ||

| IND | 295 | 2% | 461 | 2.8% | 336 | 1.9% | ||

| OTH | 4213 | 28.9% | 2175 | 13.3% | 4155 | 23.3% | ||

| POS | 4549 | 31.2% | 7568 | 46.3% | 5767 | 32.4% | ||

| PPO | 1243 | 8.5% | 1807 | 11% | 1983 | 11.1% | ||

| Received Surgery Post-Diagnosis | 9271 | 63.6% | 10,540 | 64.4% | 11,861 | 66.6% | 0.017 | 0.063 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 116 | 0.8% | 104 | 0.6% | 175 | 1% | 0.019 | 0.02 |

| Cardiac Arrhythmia | 342 | 2.3% | 323 | 2% | 404 | 2.3% | 0.026 | 0.005 |

| Valvular Disease | 119 | 0.8% | 110 | 0.7% | 160 | 0.9% | 0.017 | 0.009 |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorders | 56 | 0.4% | 34 | 0.2% | 62 | 0.3% | 0.032 | 0.006 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 168 | 1.2% | 140 | 0.9% | 227 | 1.3% | 0.03 | 0.011 |

| Hypertension Uncomplicated | 1487 | 10.2% | 1356 | 8.3% | 2159 | 12.1% | 0.066 | 0.061 |

| Hypertension Complicated | 88 | 0.6% | 110 | 0.7% | 196 | 1.1% | 0.009 | 0.054 |

| Paralysis | 42 | 0.3% | 29 | 0.2% | 50 | 0.3% | 0.023 | 0.001 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 511 | 3.5% | 603 | 3.7% | 759 | 4.3% | 0.01 | 0.039 |

| Diabetes Uncomplicated | 605 | 4.2% | 598 | 3.7% | 1032 | 5.8% | 0.026 | 0.076 |

| Diabetes Complicated | 186 | 1.3% | 110 | 0.7% | 264 | 1.5% | 0.062 | 0.018 |

| Hypothyroidism | 380 | 2.6% | 356 | 2.2% | 445 | 2.5% | 0.028 | 0.007 |

| Renal Failure | 144 | 1% | 107 | 0.7% | 212 | 1.2% | 0.037 | 0.02 |

| Liver Disease | 91 | 0.6% | 125 | 0.8% | 163 | 0.9% | 0.017 | 0.033 |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease excluding bleeding | 16 | 0.1% | 13 | 0.1% | 28 | 0.2% | 0.01 | 0.013 |

| AIDS/HIV | 7 | 0% | 11 | 0.1% | 34 | 0.2% | 0.008 | 0.041 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis/Collagen | 131 | 0.9% | 128 | 0.8% | 165 | 0.9% | 0.013 | 0.003 |

| Coagulopathy | 50 | 0.3% | 70 | 0.4% | 81 | 0.5% | 0.014 | 0.018 |

| Obesity | 176 | 1.2% | 113 | 0.7% | 170 | 1% | 0.053 | 0.024 |

| Weight Loss | 35 | 0.2% | 71 | 0.4% | 92 | 0.5% | 0.033 | 0.045 |

| Fluid and Electrolyte Disorders | 137 | 0.9% | 175 | 1.1% | 242 | 1.4% | 0.013 | 0.039 |

| Blood Loss Anemia | 10 | 0.1% | 17 | 0.1% | 31 | 0.2% | 0.012 | 0.03 |

| Deficiency Anemia | 150 | 1% | 185 | 1.1% | 233 | 1.3% | 0.01 | 0.026 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 25 | 0.2% | 31 | 0.2% | 33 | 0.2% | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| Drug Abuse | 24 | 0.2% | 19 | 0.1% | 32 | 0.2% | 0.013 | 0.004 |

| Psychoses | 58 | 0.4% | 32 | 0.2% | 56 | 0.3% | 0.037 | 0.014 |

| Depression | 387 | 2.7% | 375 | 2.3% | 396 | 2.2% | 0.023 | 0.028 |

| Matched Cohort Characteristics | ||||||||

| Characteristic | Category 1 (N = 7504) |

Category 2 (N = 7504) |

Category 3 (N = 7504) |

SMD (0 vs. 1) |

SMD (0 vs. 1) |

|||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Year of Diagnosis | 2011.19 | 4.55% | 2010.99 | 4.62% | 2011.36 | 4.52% | 0.043 | 0.037 |

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | 62.52 | 15.22% | 62.36 | 15.1% | 61.71 | 15.42% | 0.01 | 0.052 |

| Sex | 0.055 | 0.019 | ||||||

| Female (ref) | 3756 | 50.1% | 3961 | 52.8% | 3826 | 51% | ||

| Male | 3748 | 49.9% | 3543 | 47.2% | 3678 | 49% | ||

| Race | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| White (ref) | 7093 | 94.5% | 7093 | 94.5% | 7093 | 94.5% | ||

| Asian | 78 | 1% | 78 | 1% | 78 | 1% | ||

| Black | 189 | 2.5% | 189 | 2.5% | 189 | 2.5% | ||

| Hispanic | 144 | 1.9% | 144 | 1.9% | 144 | 1.9% | ||

| Tumor Type | 0.062 | 0.069 | ||||||

| Primary (ref) | 3470 | 46.2% | 3237 | 43.1% | 3213 | 42.8% | ||

| Secondary | 4034 | 53.8% | 4267 | 56.9% | 4291 | 57.2% | ||

| Insurance Plan | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| HMO | 2302 | 30.7% | 2302 | 30.7% | 2302 | 30.7% | ||

| EPO | 277 | 3.7% | 277 | 3.7% | 277 | 3.7% | ||

| IND | 213 | 2.8% | 213 | 2.8% | 213 | 2.8% | ||

| OTH | 1702 | 22.7% | 1702 | 22.7% | 1702 | 22.7% | ||

| POS | 2247 | 29.9% | 2247 | 29.9% | 2247 | 29.9% | ||

| PPO | 763 | 10.2% | 763 | 10.2% | 763 | 10.2% | ||

| Received Surgery Post-DX | 4548 | 60.6% | 4742 | 63.2% | 5129 | 68.4% | 0.053 | 0.162 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 62 | 0.8% | 64 | 0.9% | 88 | 1.2% | 0.003 | 0.035 |

| Cardiac Arrhythmia | 173 | 2.3% | 205 | 2.7% | 222 | 3% | 0.027 | 0.041 |

| Valvular Disease | 51 | 0.7% | 59 | 0.8% | 84 | 1.1% | 0.012 | 0.047 |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorders | 29 | 0.4% | 17 | 0.2% | 31 | 0.4% | 0.029 | 0.004 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 101 | 1.3% | 90 | 1.2% | 119 | 1.6% | 0.013 | 0.02 |

| Hypertension Uncomplicated | 759 | 10.1% | 760 | 10.1% | 1063 | 14.2% | <0.001 | 0.124 |

| Hypertension Complicated | 53 | 0.7% | 72 | 1% | 84 | 1.1% | 0.028 | 0.043 |

| Paralysis | 20 | 0.3% | 17 | 0.2% | 27 | 0.4% | 0.008 | 0.017 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 320 | 4.3% | 369 | 4.9% | 392 | 5.2% | 0.031 | 0.045 |

| Diabetes Uncomplicated | 326 | 4.3% | 355 | 4.7% | 518 | 6.9% | 0.019 | 0.111 |

| Diabetes Complicated | 60 | 0.8% | 68 | 0.9% | 112 | 1.5% | 0.012 | 0.065 |

| Hypothyroidism | 186 | 2.5% | 210 | 2.8% | 210 | 2.8% | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Renal Failure | 75 | 1% | 59 | 0.8% | 97 | 1.3% | 0.023 | 0.028 |

| Liver Disease | 54 | 0.7% | 74 | 1% | 81 | 1.1% | 0.029 | 0.038 |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease excluding bleeding | 9 | 0.1% | 8 | 0.1% | 17 | 0.2% | 0.004 | 0.026 |

| AIDS/HIV | 3 | 0% | 6 | 0.1% | 19 | 0.3% | 0.016 | 0.056 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis/Collagen | 59 | 0.8% | 63 | 0.8% | 83 | 1.1% | 0.006 | 0.033 |

| Coagulopathy | 33 | 0.4% | 34 | 0.5% | 53 | 0.7% | 0.002 | 0.035 |

| Obesity | 51 | 0.7% | 57 | 0.8% | 76 | 1% | 0.009 | 0.036 |

| Weight Loss | 31 | 0.4% | 38 | 0.5% | 43 | 0.6% | 0.014 | 0.023 |

| Fluid and Electrolyte Disorders | 86 | 1.1% | 105 | 1.4% | 131 | 1.7% | 0.023 | 0.05 |

| Blood Loss Anemia | 8 | 0.1% | 11 | 0.1% | 16 | 0.2% | 0.011 | 0.027 |

| Deficiency Anemia | 87 | 1.2% | 117 | 1.6% | 101 | 1.3% | 0.035 | 0.017 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 13 | 0.2% | 23 | 0.3% | 19 | 0.3% | 0.027 | 0.017 |

| Drug Abuse | 6 | 0.1% | 8 | 0.1% | 14 | 0.2% | 0.009 | 0.029 |

| Psychoses | 17 | 0.2% | 25 | 0.3% | 31 | 0.4% | 0.02 | 0.033 |

| Depression | 186 | 2.5% | 228 | 3% | 222 | 3% | 0.034 | 0.03 |

Overall, 12,805 patients received at least one PC referral (26.3%), 3,612 patients received social work services (7.4%), and 11,488 patients received home health services (23.6%) during the period of post-diagnosis follow-up. Among those that did receive PC, median time to PC initiation was 96 days. This was lower for those with newly diagnosed secondary malignancies (86 days vs. 117 days, p < 0.001).

On multivariable regression analysis of time to service initiation, Hispanic race was associated with decreased initiation of PC (versus white, OR 0.882, 95% CI 0.813 to 0.958, Table 2). Similarly, Hispanic and Asian race were associated with decreased initiation of home health services while all minority races were associated with reduced initiation of social work services. In contrast, higher provider pRDI was associated with higher incidence of initiating palliative, home health, and social work services (II vs. I, OR 1.347, 95% CI 1.271 to 1.429; III vs. I, OR 1.478, 95% CI 1.396 to 1.566).

Table 2.

Mixed effects model evaluating incidence of supportive care service utilization.

| Characteristic | Palliative Care | Home Health Services | Social Worker Services | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-Value | OR | p-Value | OR | p-Value | |

| Year of Diagnosis | 1.027 | <0.001 | 0.935 | <0.001 | 1.029 | <0.001 |

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | 1.011 | <0.001 | 1.005 | <0.001 | 0.983 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female (ref) | ||||||

| Male | 0.971 | 0.178 | 0.981 | 0.389 | 0.850 | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White (ref) | ||||||

| Asian | 0.881 | 0.053 | 0.842 | 0.013 | 0.599 | <0.001 |

| Black | 1.031 | 0.396 | 0.981 | 0.612 | 0.756 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.882 | 0.003 | 0.900 | 0.016 | 0.819 | 0.003 |

| Tumor Type | ||||||

| Primary (ref) | ||||||

| Secondary | 1.678 | <0.001 | 1.398 | <0.001 | 0.737 | <0.001 |

| Insurance Plan | ||||||

| HMO | ||||||

| EPO | 1.587 | <0.001 | 1.401 | <0.001 | 1.109 | 0.185 |

| IND | 0.274 | <0.001 | 0.299 | <0.001 | 2.166 | <0.001 |

| OTH | 2.197 | <0.001 | 0.391 | <0.001 | 0.822 | 0.003 |

| POS | 1.744 | <0.001 | 1.582 | <0.001 | 1.239 | <0.001 |

| PPO | 1.656 | <0.001 | 0.863 | <0.001 | 1.013 | 0.856 |

| Received Surgery Post-Diagnosis | 1.772 | <0.001 | 2.263 | <0.001 | 1.458 | <0.001 |

| Provider pRDI Category | ||||||

| I | ||||||

| II | 1.347 | <0.001 | 1.268 | <0.001 | 1.335 | <0.001 |

| III | 1.478 | <0.001 | 1.556 | <0.001 | 1.498 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0.827 | 0.131 | 1.042 | 0.765 | 0.587 | 0.055 |

| Cardiac Arrhythmia | 0.951 | 0.505 | 0.881 | 0.153 | 0.840 | 0.249 |

| Valvular Disease | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.360 | 0.019 | 1.476 | 0.056 |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorders | 0.874 | 0.481 | 0.763 | 0.234 | 1.802 | 0.033 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 0.947 | 0.591 | 0.739 | 0.020 | 0.751 | 0.201 |

| Hypertension Uncomplicated | 0.964 | 0.344 | 0.987 | 0.763 | 0.816 | 0.005 |

| Hypertension Complicated | 1.065 | 0.613 | 0.842 | 0.262 | 0.583 | 0.058 |

| Paralysis | 0.906 | 0.672 | 1.426 | 0.112 | 1.452 | 0.207 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 1.011 | 0.851 | 1.003 | 0.957 | 0.861 | 0.164 |

| Diabetes Uncomplicated | 1.093 | 0.095 | 1.150 | 0.020 | 1.302 | 0.004 |

| Diabetes Complicated | 1.172 | 0.103 | 0.881 | 0.318 | 1.330 | 0.093 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.066 | 0.353 | 1.075 | 0.346 | 1.093 | 0.438 |

| Renal Failure | 0.970 | 0.794 | 0.947 | 0.702 | 1.230 | 0.338 |

| Liver Disease | 1.127 | 0.301 | 1.210 | 0.122 | 0.800 | 0.315 |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease excluding bleeding | 1.692 | 0.063 | 1.132 | 0.709 | 1.388 | 0.506 |

| AIDS/HIV | 0.950 | 0.879 | 1.540 | 0.164 | 0.833 | 0.762 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis/Collagen | 0.976 | 0.829 | 1.327 | 0.016 | 1.126 | 0.515 |

| Coagulopathy | 1.113 | 0.509 | 1.380 | 0.056 | 1.197 | 0.522 |

| Obesity | 0.989 | 0.918 | 1.019 | 0.885 | 1.437 | 0.026 |

| Weight Loss | 1.186 | 0.292 | 1.533 | 0.010 | 0.763 | 0.403 |

| Fluid and Electrolyte Disorders | 0.957 | 0.671 | 0.946 | 0.630 | 1.021 | 0.907 |

| Blood Loss Anemia | 0.640 | 0.154 | 0.913 | 0.787 | 0.453 | 0.280 |

| Deficiency Anemia | 1.009 | 0.923 | 1.180 | 0.137 | 0.945 | 0.753 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 0.736 | 0.238 | 0.891 | 0.672 | 0.830 | 0.649 |

| Drug Abuse | 0.981 | 0.945 | 1.077 | 0.803 | 0.469 | 0.152 |

| Psychoses | 1.331 | 0.131 | 0.744 | 0.244 | 2.712 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1.118 | 0.112 | 1.142 | 0.072 | 2.775 | <0.001 |

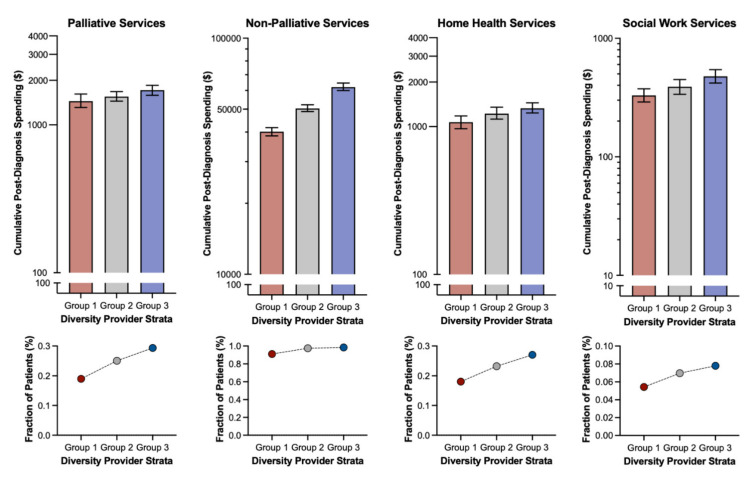

Regarding total healthcare spending, patient race did not impact cumulative utilization of palliative, home health, or social work services (Table 3). However, those patients qualifying under category II had significantly higher PC spending (vs. I, B = 276.364, 95% CI 138.550 to 414.179) while those qualifying under category III had significantly higher spending on both PC (vs. I, B = 439.061, 95% CI 301.514 to 576.608) and home health services (vs. I, B = 849.411, 95% CI 393.651 to 1305.171).

Table 3.

Mixed effects model evaluating supportive care service spending.

| Characteristic | Palliative Care | Home Health Services | Social Worker Services | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | p-Value | B | p-Value | B | p-Value | |

| Year of Diagnosis | −6.284 | 0.328 | −50.284 | 0.018 | −1.836 | 0.618 |

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | 6.053 | <0.001 | −3.555 | 0.537 | 1.07 | 0.283 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female (ref) | ||||||

| Male | −208.974 | <0.001 | −136.668 | 0.432 | −20.919 | 0.487 |

| Race | ||||||

| White (ref) | ||||||

| Asian | −71.749 | 0.648 | −513.737 | 0.324 | 169.436 | 0.060 |

| Black | 104.263 | 0.242 | −434.966 | 0.141 | −87.706 | 0.086 |

| Hispanic | 83.091 | 0.407 | −545.657 | 0.101 | −51.849 | 0.367 |

| Tumor Type | ||||||

| Primary (ref) | ||||||

| Secondary | −177.758 | 0.001 | −419.209 | 0.023 | −39.836 | 0.213 |

| Insurance Plan | ||||||

| HMO | ||||||

| EPO | −533.252 | <0.001 | −140.992 | 0.720 | −185.904 | 0.006 |

| IND | −1095.737 | <0.001 | −935.989 | 0.124 | −238.122 | 0.024 |

| OTH | 1439.161 | <0.001 | −641.019 | 0.026 | −265.996 | <0.001 |

| POS | −563.782 | <0.001 | 55.797 | 0.823 | −163.057 | <0.001 |

| PPO | 279.395 | 0.004 | −540.616 | 0.096 | −220.862 | <0.001 |

| Received Surgery Post-Diagnosis | 636.44 | <0.001 | 829.55 | <0.001 | −24.814 | 0.433 |

| Provider pRDI Category | ||||||

| I | ||||||

| II | 276.364 | <0.001 | 97.673 | 0.675 | 19.296 | 0.632 |

| III | 439.061 | <0.001 | 849.411 | <0.001 | 17.006 | 0.672 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Congestive Heart Failure | −505.04 | 0.096 | −326.31 | 0.746 | −122.111 | 0.483 |

| Cardiac Arrhythmia | 125.699 | 0.500 | −84.224 | 0.891 | −33.675 | 0.752 |

| Valvular Disease | 220.38 | 0.464 | −172.757 | 0.863 | −42.285 | 0.806 |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorders | −204.489 | 0.665 | −552.753 | 0.724 | −40.923 | 0.880 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 55.874 | 0.826 | −129.424 | 0.878 | 530.424 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension Uncomplicated | −51.218 | 0.595 | −18.985 | 0.953 | −102.452 | 0.063 |

| Hypertension Complicated | −214.48 | 0.499 | −124.797 | 0.906 | −152.06 | 0.403 |

| Paralysis | 788.05 | 0.134 | 629.979 | 0.717 | −118.86 | 0.693 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 259.933 | 0.063 | 283.419 | 0.541 | 36.887 | 0.646 |

| Diabetes Uncomplicated | 688.99 | <0.001 | 125.795 | 0.778 | −60.088 | 0.437 |

| Diabetes Complicated | 517.228 | 0.042 | −215.891 | 0.798 | 520.013 | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 243.271 | 0.159 | −187.655 | 0.743 | −79.269 | 0.424 |

| Renal Failure | −466.209 | 0.115 | 255.195 | 0.795 | −53.658 | 0.752 |

| Liver Disease | −257.867 | 0.390 | −450.065 | 0.650 | −116.873 | 0.496 |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease excluding bleeding | 377.287 | 0.623 | −1041.792 | 0.682 | 9.399 | 0.983 |

| AIDS/HIV | −297.161 | 0.710 | −1294.699 | 0.625 | −11.993 | 0.979 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis/Collagen | 419.5 | 0.136 | 377.811 | 0.685 | 691.935 | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 11.361 | 0.978 | 13257.089 | <0.001 | −24.972 | 0.916 |

| Obesity | −322.404 | 0.240 | −13.938 | 0.988 | 182.74 | 0.245 |

| Weight Loss | 748.606 | 0.072 | 31.574 | 0.982 | −73.72 | 0.757 |

| Fluid and Electrolyte Disorders | −191.583 | 0.455 | −999.169 | 0.239 | 7.816 | 0.958 |

| Blood Loss Anemia | −690.447 | 0.367 | −191.622 | 0.940 | −108.058 | 0.805 |

| Deficiency Anemia | 9.335 | 0.970 | −270.483 | 0.745 | −93.898 | 0.514 |

| Alcohol Abuse | −388.13 | 0.529 | −391.862 | 0.848 | 246.143 | 0.486 |

| Drug Abuse | 64.879 | 0.923 | −539.659 | 0.808 | −273.219 | 0.477 |

| Psychoses | 3.204 | 0.995 | −285.142 | 0.858 | 67.88 | 0.805 |

| Depression | −88.445 | 0.609 | −109.414 | 0.849 | 402.072 | <0.001 |

We also analyzed impact of gender and insurance type on incidence of supportive care services. In general, gender had no impact on service initiation, and male gender was only significantly associated with lower likelihood of referral to social work (vs. female, OR 0.850, Table 2). For the most part, private insurance plans were related to greater rates of initiation of supportive care services, although the results for home health and social work referral were variable (Table 2).

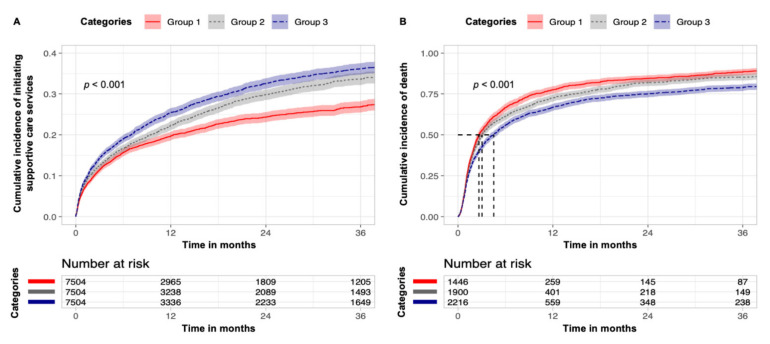

After matching, we aimed for covariate balance, particularly those associated with demographics and plan type (Table 1). Comparing these matched cohorts stratified by provider pRDI, patients classified within higher categories had significantly higher incidence of initiating supportive care services (Figure 2A, p < 0.001). Furthermore, incidence of death following initiation of these services was significantly lower among patients of higher categories, indicating earlier supportive care service involvement (Figure 2B, p < 0.001). Comparing overall cumulative use of palliative, home health, and social work services, patients classified under higher provider pRDI categories demonstrated significantly higher utilization. Comparing palliative, non-palliative, home health, and social work services, increasing provider pRDI was associated with monotonic increases in both spending and prevalence of utilization (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Timing of initiation of supportive care services. (A) Cumulative incidence of initiating supportive care services over time stratified by provider patient racial diversity index (provider pRDI) categories for the matched cohort. (B) Cumulative incidence of death following supportive care service initiation over time stratified by provider pRDI.

Figure 3.

Effect of provider patient racial diversity index (provider pRDI): effect of provider pRDI on spending for palliative, non-palliative, home health, and social work services in the matched cohort.

4. Discussion

Our final cohort included 48,722 privately insured neurosurgical patients with diagnoses of primary and secondary CNS malignancies. Our analysis demonstrates statistically significant low rates of PC, home health, and social work services among patients of racial minority groups, even though, over time, all patients had greater likelihood of referral to these services. Hispanic patients had low likelihood of engaging with all three categories of supportive care services. Black, Asian, and Hispanic patients all had significantly lower utilization of social work services. However, patients who saw providers categorized into high provider pRDI (categories II and III) were increasingly more likely to interface with supportive care services and at an earlier point in their disease courses.

4.1. Racial Disparities in Treatment and Surgical Outcomes

Pervasive racial disparities exist for patients with CNS malignancies in accessing high-quality care at specialized centers. Hospitals that receive high volumes of patients with CNS malignancies arguably have better postoperative outcomes, but a retrospective study revealed that Hispanic white patients with GBM compared to non-Hispanic white patients had significantly lower odds of receiving surgery at a high-volume center (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.49–0.69, p < 0.001) [15].

Race appears to influence treatment options for patients with CNS malignancies as well. Out of 103,652 patients, non-Hispanic white patients had significantly higher rates of gross total surgical resection of their GBM (30.7%) as well as receipt of chemotherapy (65.8%) [16]. In addition, African American patients with metastatic spinal disease were less likely to receive surgery (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.62–0.82, p < 0.001; RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.93) compared to white patients [17,18]. Race-based disparities were also apparent when comparing utilization of conventional external beam radiation versus more modern spinal stereotactic body radiation therapy for spinal metastases treatment; African American background was significantly more associated with the traditional radiation modality (adjusted OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7–1.0) [19].

Racial background affects neurosurgical outcomes and post-operative disposition. Our cohort indicates that patients from minority backgrounds, namely Hispanic and Asian, are not referred to home health services as often as their Caucasian counterparts. Such a finding is reflected in published neurosurgical literature as well. For patients who underwent craniotomies for brain tumor resection, being from a Black background increased the risk of non-home disposition and extended length of stay by 6.9% and 6.5%, respectively, compared to white patients [20]. A similar phenomenon was seen in cohorts of Black patients who had undergone surgery for spine metastases, where the odds of non-home discharge were significantly higher than for white patients (adjusted OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.28–3.92, p = 0.005; OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.05–1.35, p = 0.007) [17,21]. Patients’ racial backgrounds impact their surgical care and postoperative outcomes, such as non-routine dispositions other than the ideal home discharge with appropriate home health and supportive services.

4.2. Racial Disparities in Palliative and Supportive Care

Patients with advanced cancer experience disparities in access to various supportive care services, such as PC. Minorities with advanced cancer expressed greater needs for support, including psychological, financial, social, and daily living aid [22]. These differences persisted for up to 12 months of follow-up for the cohort of patients with newly diagnosed advanced lung cancer [22]. Even though African American patients with advanced cancer perceived greater needs for hospices, they were among the lowest utilizers of such services [23,24]. Beyond hospice services, patients of racial minorities also had higher symptom burden—depressed mood, pain, and fatigue—by the time of referral to an institution’s Supportive Care Center [25]. As for patients with CNS malignancies, such as brain metastases, non-white patients were less likely to receive PC [26]. There were no recent and relevant publications with data on minority patients who suffer from spinal tumors.

4.3. Provider Influences on Quality of Healthcare for Minority Groups

An opportunity for systems-level modification is the influence of providers on the quality of healthcare delivered for minority patients. Providers from racial minority backgrounds were more likely to care for underserved, minority patients [27]. By focusing on providers and the diversity of their patient populations, we sought to not only use provider pRDI as a proxy of the practice’s demographic diversity but also allude to its potential utility of assessing a provider’s individual cultural sensitivity. In our cohort, the level of provider pRDI shows a clear correlation with increased utilization, spending, and earlier referral patterns of all supportive services: PC, social work, and home health.

Unfortunately, there are challenges in effective medical communication and delivering care for minority patients. First, language barriers prevent access to quality healthcare. A systematic review of 33 studies on patient–provider relationships where the patients’ primary language was not English demonstrated that the vast majority of studies reported favorable outcomes for language-concordant care and 9% of studies resulted in worse outcomes for language-discordant care [28]. Furthermore, not only do physicians communicate less effectively with minority patients, but these patients also express their needs less assertively than do white patients [29]. Such a phenomenon may predispose minority patients to receive fewer recommendations for care, highlighting potential underlying provider biases [29,30]. One study offers an alternative finding, where unconscious racial biases were not necessarily associated with clinical decision making in the acute surgical care setting, even though such biases were present in most surveyed physician respondents [31].

Racial concordance between patient and provider is an important concept that has been previously studied and indicates higher patient satisfaction and quality of delivered healthcare. For example, Black patients rated their Black doctors as “excellent” (adjusted OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.55–3.72) and reported receiving all necessary and recommended medical care in the past year (adjusted OR 2.94, 95% CI 1.10–7.87) [32]. A similar effect on patient satisfaction was reported by Hispanic patients who saw Hispanic physicians (adjusted OR 1.74, 95% CI 1.01–2.99) [32].

However, in situations where racial concordance may not be obtained, it is still critical to address and encourage cultural sensitivity among providers. In one survey of surgical oncologists, 71% of respondents reported seeing patients from six or more racial minority groups, although only 58% of providers received specific cultural diversity training [33]. Those who completed such training scored higher on the Cultural Competence Assessment than surgeons not exposed to diversity training (10.56 versus 9.82, p < 0.001) [33]. Our study’s findings regarding provider pRDI suggest the importance of exposure to racial diversity in patient populations and, by extension, cultural sensitivity in providing quality care for racial minority patients. Future prospective studies to examine the association between provider pRDI and the utilization and timing of healthcare resources, such as PC and other supportive care services, would need to be conducted.

Most published research on the topics of racial disparities in oncology and palliative care were conducted within the American healthcare system, with one Australian study assessing rates of chemotherapy administration in culturally and linguistically diverse patient populations [34]. While the aforementioned retrospective analysis determined no differences in adjuvant chemotherapy use, additional studies are warranted to characterize the prevalence and contributing factors of health inequities in diverse healthcare systems beyond the United States [34].

Even with many publications identifying and acknowledging the reality of racial disparities, more research is required to elucidate potential root causes and methods of critically assessing health inequities. For instance, it has been demonstrated that the quality of healthcare minority patients receive is influenced by where these patients access care [13,35,36]. Beyond characterizing hospital facilities, health disparity research may also benefit from a focus on healthcare providers themselves.

Limitations of our study include those inherent to retrospective studies based on nationwide claims databases. These include selection bias and missing or miscoded data and variables. The Optum database itself includes only patients who are privately insured, resulting in a more homogeneous sampling for the patient cohort in question. All diagnoses and claims were also identified based on standard coding systems, such as ICD, and cannot be subject to further verification for accuracy. We introduce the novel construct—provider pRDI—in our study, as the Optum database does not include provider details, such as experience level, or granular geographic and demographic details, such as racial makeup, income levels or descriptors of households, of the patient population in a certain locale. In addition, it is not yet known whether our study findings are generalizable to healthcare systems beyond the United States. Strengths of our study include the number of analyzed patients as well as the longitudinal aspect of the analyses from diagnosis of CNS malignancy until death in terms of investigating timing of PC and other supportive services. Future studies can take myriad directions: the impact of specific socioeconomic or provider-level factors on supportive care utilization and referral patterns; the influence of provider pRDI on other aspects of high-quality end-of-life care, such as shared care plans and advance care planning; or the longitudinal effects of cultural sensitivity training for providers on provider pRDI and utilization of supportive care services [37].

5. Conclusions

Patients suffering from malignancies of the central nervous system are less likely to receive palliative and other supportive services in a timely manner when they are of racial minority backgrounds. Such an effect is mitigated when these patients encounter at least one provider who scores highly on the provider patient racial diversity index—a measure of the proportion of non-white patients seen by the said provider. Patients seen by providers who encounter a more diverse patient population also receive supportive care services earlier in their disease courses. Our study highlights not only patient-level healthcare disparities in access to and utilization of quality palliative and supportive healthcare but also the possibility and need for provider-level intervention.

Abbreviations

| American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) |

| Central nervous system (CNS) |

| Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) |

| Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO) |

| Glioblastoma (GBM) |

| Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) |

| Indemnity (IND) |

| International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system |

| Other (OTH) |

| Palliative care (PC) |

| Point-of-service (POS) |

| Provider patient racial diversity index (provider pRDI) |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.J. and A.W.; methodology, M.C.J., G.L., G.H. and A.W.; formal analysis, M.C.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.W. and M.C.J.; writing—review and editing, G.H., J.R., C.C.Z., R.T. and G.L.; supervision, A.W.; funding acquisition, A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Stanford University (protocol number 62056 with date of approval 24 July 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. The data presented in this study are openly available in Optum Clinformatics Datamart Database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

A.W. is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under award F32HS028747.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Palliative Care. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toor H., Barrett R., Myers J., Parry N. Implementing a Novel Interprofessional Caregiver Support Clinic: A Palliative Medicine and Social Work Collaboration. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021:10499091211051669. doi: 10.1177/10499091211051669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bekelman D.B., Johnson-Koenke R., Bowles D.W., Fischer S.M. Improving Early Palliative Care with a Scalable, Stepped Peer Navigator and Social Work Intervention: A Single-Arm Clinical Trial. J. Palliat. Med. 2018;21:1011–1016. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moncho M.E.I., Palomar-Abril V., Soria-Comes T. Palliative Care Unit at Home: Impact on Quality of Life in Cancer Patients at the End of Life in a Rural Environment. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021;39:529–532. doi: 10.1177/10499091211038303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chini C., Bascialla L., Giaquinto A., Magni E., Gobba S.M., Proserpio I., Suter M.B., Nigro O., Tinelli G., Pinotti G. Homcology: Home chemotherapy delivery in a simultaneous care project for frail advanced cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer. 2020;29:917–923. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrell B.R., Temel J.S., Temin S., Alesi E.R., Balboni T.A., Basch E.M., Firn J.I., Paice J.A., Peppercorn J.M., Phillips T., et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:96–112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stupp R., Taillibert S., Kanner A.A., Kesari S., Steinberg D.M., Toms S.A., Taylor L.P., Lieberman F., Silvani A., Fink K.L., et al. Maintenance Therapy With Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Temozolomide vs Temozolomide Alone for Glioblastoma. JAMA. 2015;314:2535–2543. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stupp R., Taillibert S., Kanner A.A., Read W., Steinberg D.M., Lhermitte B., Toms S., Idbaih A., Ahluwalia M.S., Fink K., et al. Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Maintenance Temozolomide vs Maintenance Temozolomide Alone on Survival in Patients With Glioblastoma. JAMA. 2017;318:2306–2316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nabors L.B., Portnow J., Ahluwalia M., Baehring J., Brem H., Brem S., Butowski N., Campian J.L., Clark S.W., Fabiano A.J., et al. Central Nervous System Cancers, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020;18:1537–1570. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbett K., Sharma A., Pond G.R., Brastianos P.K., Das S., Sahgal A., Jerzak K.J. Central Nervous System–Specific Outcomes of Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trials in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer, and Melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1062. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng C., Wen W., Morgans A.K., Pao W., Shu X.-O., Zheng W. Disparities by Race, Age, and Sex in the Improvement of Survival for Major Cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:88–96. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vlacich G., Samson P.P., Perkins S.M., Roach M.C., Parikh P.J., Bradley J.D., Lockhart A.C., Puri V., Meyers B.F., Kozower B., et al. Treatment utilization and outcomes in elderly patients with locally advanced esophageal carcinoma: A review of the National Cancer Database. Cancer Med. 2017;6:2886–2896. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole A.P., Nguyen D.-D., Meirkhanov A., Golshan M., Melnitchouk N., Lipsitz S.R., Kilbridge K.L., Kibel A.S., Cooper Z., Weissman J., et al. Association of Care at Minority-Serving vs Non-Minority-Serving Hospitals With Use of Palliative Care Among Racial/Ethnic Minorities with Metastatic Cancer in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019;2:e187633. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elixhauser A., Steiner C., Harris D.R., Coffey R.M. Comorbidity Measures for Use with Administrative Data. Med. Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyal A., Zreik J., Brown D.A., Kerezoudis P., Habermann E.B., Chaichana K.L., Chen C.C., Bydon M., Parney I.F. Disparities in access to surgery for glioblastoma multiforme at high-volume Commission on Cancer–accredited hospitals in the United States. J. Neurosurg. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.3171/2021.7.JNS211307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodges T.R., Labak C.M., Mahajan U.V., Wright C.H., Wright J., Cioffi G., Gittleman H., Herring E.Z., Zhou X., Duncan K., et al. Impact of race on care, readmissions, and survival for patients with glioblastoma: An analysis of the National Cancer Database. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2021;3:vdab040. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdab040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos R.D.L.G., Benton J.A., Gelfand Y., Echt M., Rodriguez J.V.F., Yanamadala V., Yassari R. Racial disparities in clinical presentation, type of intervention, and in-hospital outcomes of patients with metastatic spine disease: An analysis of 145,809 admissions in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;68:101792. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2020.101792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiu R.G., Murphy B.E., Zhu A., Mehta A.I. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Inpatient Management of Primary Spinal Cord Tumors. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:e175–e184. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim E., McClelland I.S., Jaboin J.J., Attia A. Disparities in Patterns of Conventional Versus Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Spine Metastasis in the United States. J. Palliat. Care. 2020;36:130–134. doi: 10.1177/0825859720982204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muhlestein W.E., Akagi D.S., Chotai S., Chambless L.B. The Impact of Race on Discharge Disposition and Length of Hospitalization After Craniotomy for Brain Tumor. World Neurosurg. 2017;104:24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hung B., Pennington Z., Hersh A.M., Schilling A., Ehresman J., Patel J., Antar A., Porras J.L., Elsamadicy A.A., Sciubba D.M. Impact of race on nonroutine discharge, length of stay, and postoperative complications after surgery for spinal metastases. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2022;36:678–685. doi: 10.3171/2021.7.SPINE21287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazor M.B., Li L., Morillo J., Allen O.S., Wisnivesky J.P., Smith C.B. Disparities in Supportive Care Needs Over Time Between Racial and Ethnic Minority and Non-Minority Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022;63:563–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LoPresti M.A., Dement F., Gold H.T. End-of-Life Care for People With Cancer From Ethnic Minority Groups. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2014;33:291–305. doi: 10.1177/1049909114565658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith A.K., Earle C.C., McCarthy E.P. Racial and Ethnic Differences in End-of-Life Care in Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries with Advanced Cancer. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008;57:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reyes-Gibby C.C., Anderson K.O., Shete S., Bruera E., Yennurajalingam S. Early referral to supportive care specialists for symptom burden in lung cancer patients. Cancer. 2011;118:856–863. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubens M., Ramamoorthy V., Saxena A., McGranaghan P., Bhatt C., Das S., Shehadeh N., Veledar E., Viamonte-Ros A., Odia Y., et al. Inpatient Palliative Care Use Among Critically III Brain Metastasis Patients in the United States. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;43:806–812. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu G., Fields S.K., Laine C., Veloski J.J., Barzansky B., Martini C.J. The relationship between the race/ethnicity of generalist physicians and their care for underserved populations. Am. J. Public Health. 1997;87:817–822. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.5.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diamond L., Izquierdo K., Canfield D., Matsoukas K., Gany F. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Patient–Physician Non-English Language Concordance on Quality of Care and Outcomes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019;34:1591–1606. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04847-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schouten B.C., Meeuwesen L., Schouten B.C., Meeuwesen L. Cultural differences in medical communication: A review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006;64:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ibrahim S.A., Whittle J., Bean-Mayberry B., Kelley M.E., Good C., Conigliaro J. Racial/Ethnic Variations in Physician Recommendations for Cardiac Revascularization. Am. J. Public Health. 2003;93:1689–1693. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.10.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haider A.H., Schneider E.B., Sriram N., Dossick D.S., Scott V.K., Swoboda S.M., Losonczy L., Haut E.R., Efron D.T., Pronovost P.J., et al. Unconscious Race and Social Class Bias Among Acute Care Surgical Clinicians and Clinical Treatment Decisions. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:457–464. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saha S., Komaromy M., Koepsell T.D., Bindman A.B. Patient-Physician Racial Concordance and the Perceived Quality and Use of Health Care. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999;159:997–1004. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.9.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doorenbos A.Z., Morris A.M., Haozous E.A., Harris H., Flum D.R. ReCAP: Assessing Cultural Competence Among Oncology Surgeons. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016;12:61–62. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.006932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thai A.A., Tacey M., Byrne A., White S., Yoong J. Exploring disparities in receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy in culturally and linguistically diverse groups: An Australian centre’s experience. Intern. Med. J. 2017;48:561–566. doi: 10.1111/imj.13572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasnain-Wynia R., Baker D.W., Nerenz D., Feinglass J., Beal A.C., Landrum M.B., Behal R., Weissman J.S. Disparities in Health Care Are Driven by Where Minority Patients Seek Care. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167:1233–1239. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu P.W., Scully R.E., Fields A.C., Welten V.M., Lipsitz S.R., Trinh Q.-D., Haider A., Weissman J.S., Freund K.M., Melnitchouk N. Racial Disparities in Treatment for Rectal Cancer at Minority-Serving Hospitals. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020;25:1847–1856. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bevilacqua G., Bolcato M., Rodriguez D., Aprile A. Shared care plan: An extraordinary tool for the personalisation of medicine and respect for self-determination. Acta Biomed. 2021;92:e2021001. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92i1.9597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. The data presented in this study are openly available in Optum Clinformatics Datamart Database.