Abstract

Significance:

Secondary lymphedema is a debilitating disease caused by lymphatic dysfunction characterized by chronic swelling, dysregulated inflammation, disfigurement, and compromised wound healing. Since there is no effective cure, animal model systems that support basic science research into the mechanisms of secondary lymphedema are critical to advancing the field.

Recent Advances:

Over the last decade, lymphatic research has led to the improvement of existing animal lymphedema models and the establishment of new models. Although an ideal model does not exist, it is important to consider the strengths and limitations of currently available options. In a systematic review adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, we present recent developments in the field of animal lymphedema models and provide a concise comparison of ease, cost, reliability, and clinical translatability.

Critical Issues:

The incidence of secondary lymphedema is increasing, and there is no gold standard of treatment or cure for secondary lymphedema.

Future Directions:

As we iterate and create animal models that more closely characterize human lymphedema, we can achieve a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology and potentially develop effective therapeutics for patients.

Keywords: animal model, lymphatic injury, secondary lymphedema

Alex K. Wong, MD, FACS

SCOPE AND SIGNIFICANCE

This review will highlight animal models of secondary lymphedema presented within the last ten years to bring researchers and health care professionals up to date with the literature. We provide a brief background on the etiology and pathophysiology of lymphedema and the current limitations of treatment faced in the clinical setting. The models highlighted in this review demonstrate promising outcomes for developing a deeper understanding of lymphedema pathology and therapies.

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE

Secondary lymphedema has etiologies in lymph node dissection and radiation therapy, which are indicated in the management of malignancies ranging from head and neck cancers, to melanoma, gynecological, and genitourinary cancers.1–3 Lymphedema progresses with painful soft tissue swelling in the peripheral limbs, which results in reduced mobility and quality of life. Although significant strides have been made in lymphatic research, the underlying mechanisms of the disease are still poorly understood. Animal models are indispensable to lymphatic research as they bridge the gap between in vitro discoveries and therapeutic applications in the clinic.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Current treatments are largely limited to conservative measures, such as weight management, exercise, and physiotherapy, which relieve patient discomfort by reducing limb volume and improving daily functions.4 Few pharmacological options to tackle mechanisms of lymphedema have been identified. Microsurgical interventions, such as lymph node transplant and lymphovenous bypass, mechanically drain the edematous tissue, but these relatively new procedures are invasive, lack long-term follow-up data, and are costly to patients.5 With a shortage of cost-effective treatments, there is an increasing demand for therapy targeting mechanisms of lymphedema to prevent, delay, or even cure this debilitating disease.

BACKGROUND

Animal models of lymphedema

Lymphatic vessels are vital to the human circulatory system and fluid homeostasis. As a result of our high-pressure arterial system, excess fluid is filtered from the capillaries into the interstitial compartment. While most of this excess fluid is recirculated by the venous capillaries, the remaining interstitial fluid is high in protein, and is drained into the lymphatic capillaries where it becomes lymph.6 The lymphatic system provides a conduit from extravascular tissue to the venous system and is involved in fluid removal, lipid absorption, and immune cell transport.7 Lymphedema, the manifestation of lymphatic dysfunction, is the accumulation of lipid and protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space that occurs after the loss of fluid homeostasis from lymphatic agenesis, obstruction, or destruction.8 The result is a debilitating disease characterized by chronic limb swelling, which currently affects hundreds of millions of individuals worldwide.

The etiologies of lymphedema are categorized into primary (inherited) or secondary (acquired) origins. Primary lymphedema refers to lymphatic dysfunction as a result of genetic mutations and, while rare, may present at birth (congenital), childhood through young adulthood (praecox), or even late adulthood (tarda).6 One congenital form of lymphedema, Milroy's disease, is associated with a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 (VEGFR-3) signaling defect. Because VEGFR-3 signaling is a key component of lymphangiogenesis, Milroy's disease is an example of agenesis and demonstrates the absence of lymphatic vessels.9

On the other hand, secondary lymphedema (acquired) is caused by lymphatic injury with resulting lymphatic obstruction or destruction. One example of lymphatic obstruction found in the developing world is lymphatic filariasis, which is most commonly caused by Wuchereria Bancrofti. The larvae of this parasite, inherited from a mosquito bite, migrate to and reside in our lymphatic vessels, resulting in lymphatic stasis.

In developed countries, such as the United States, secondary lymphedema is most commonly caused by lymphadenectomy, which is the surgical removal of lymph nodes from areas such as axillary and pelvic regions in the treatment of malignancies.9 This results in the artificial disruption of lymphatic drainage that can advance to a chronic state of inflammation and fibrosis, increasing pain and risk of infection commonly of the lower limbs. Current management techniques include physiotherapy, manual lymphatic massage, and compression therapy.10 Compression therapy supplements the physiological role of muscles in pumping the excess fluid back to the circulatory system, effectively reducing limb volume through a combination of garments and bandages. Lifestyle modifications, such as exercise, are recommended due to the close association between lymphedema progression, obesity, and cardiovascular health.11 Emerging trials have demonstrated that weight management and exercise reduce limb swelling and improve quality of life.12 However, patient adherence to these conservative measures may be poor due to their time-consuming nature, disruption in daily activities, and reduction in overall quality of life.13

It is evident that accessible treatments only limit the progression of symptoms and do not address the underlying problem. Due to the lack of a definitive treatment in the clinic, several animal models of lymphedema have been employed in laboratories to test novel therapeutic options. In an effort to understand the pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment of lymphedema, researchers have conducted animal studies, but these present with a multitude of advantages and disadvantages in terms of cost, reliability, and clinical relevance in modeling this human disease.

Exploration of novel approaches and elucidation of lymphedema pathogenesis will allow investigators to approach therapy development from a new angle and ultimately translate this to the delivery of high-value care. Recently, Frueh et al.14 evaluated the accessibility of surgical approaches to lymphedema treatments, while Hadrian et al.15 summarized imaging modalities in lymphedema evaluation. This review builds upon these previous findings with the addition of recent innovations and assesses postsurgical animal models of secondary lymphedema reported within the past decade.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.16 After consultation with an information specialist, the databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus) were searched for published literature restricted to the dates between January 2010–December 2020. The algorithm for article retrieval, title/abstract screening, full-text review, and data extraction is presented (Fig. 1). The search terms used were (“Animal Model” OR (“Animal Model” AND (“Disease” OR “Laboratory” OR “Experimental”)) AND (“Lymphedema” OR “Lymphatic Injury”)). The final search queries are detailed in Appendix Table A1.

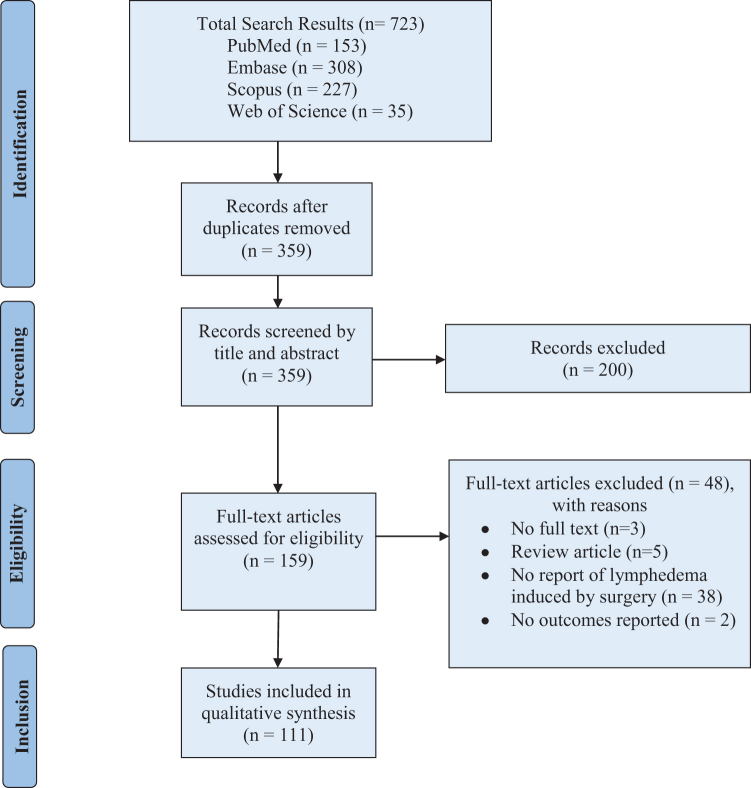

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Adapted from Moher et al.16 Color images are available online.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed in Table 1 were rigorously applied at each stage to initial abstract/title screening and full-text screening by two independent reviewers. Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer. Included studies were evaluated for reports of outcomes of lymphedema, such as changes in limb volume and a suggested set of histopathological parameters14 (i.e., fibrosis, immune infiltration, and adipose deposition). Corresponding authors of published articles without readily available full text articles were contacted for a copy. Articles of which authors did not respond to requests for the full text were excluded from review.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

| Articles published in English Preclinical animal models of surgery or radiation-induced lymphedema Reports of animal studies published between the years 2010–2020 |

| Exclusion criteria |

| No full text availability No report of surgery or radiation-induced lymphedema No report of lymphedema success rate, limb volume, fibrosis, inflammation, or adipose deposition Human, ex vivo, or in vitro studies Letters, comments, and editorials |

DISCUSSION

Our database searches yielded 723 citations. After duplicates were removed, 359 studies remained. Title and abstract screening resulted in 159 studies for in-depth review. Full text review was performed with rigorous application of our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Forty-eight studies were excluded due to the reasons listed in Fig. 1, and 111 studies were selected for data extraction. To provide a concise summary, 29 of the eligible 111 studies were highlighted to represent recent advancements, the breadth of animal species and associated methods of lymphedema induction, primary outcomes such as limb measurements, and secondary outcomes such as fibrosis, immune cell infiltration, and adipose deposition. Limb measurements were frequently represented as a standardized mean in individual studies. For the purpose of this review, changes in limb measurement as a result of lymphedema induction were calculated and then simplified to a percent increase or decrease compared to animal controls. Secondary outcomes were presented as a descriptive summary due to the diversity of experimental design.

A narrative summary of each species is presented. While our database searches provided an abundance of high-quality studies, meta-analysis was not possible due to the high degree of heterogeneity across studies, such as significant variations in animal characteristics and surgical techniques, variance in time points, and inconsistent reporting of outcomes.

A comparison of animal models

Animal models bridge in vitro studies and clinical trials. A current lack of definitive treatments highlights the need for a clinically relevant model of secondary lymphedema.17 While the research community has made important strides in this endeavor, an ideal animal model of secondary lymphedema remains elusive. When selecting a potential model, key factors must be considered. First, the model must mimic the pathophysiology of lymphedema in humans. Macroscopic changes, such as changes in limb circumference or volume, should be reproducible with an induction method. The model should also reflect histopathological changes, such as fibrosis, infiltration of immune cells, and adipose deposition.14,18 Furthermore, the model must be highly reliable; if a model cannot be consistently reproduced within the same or in another research environment, the experimental result loses credibility. Finally, each model comes with its unique set of resources such as cost, microsurgical skills, and equipment. Surgical excision of lymphatic structures, especially of small animal models, may require microscopes, and research personnel must be adequately trained in these protocols. In this study, we draw from the details of our highlighted studies to provide a concise summary of each model's strengths and potential pitfalls and compare the key factors stated above.

Mouse

Mouse limb and tail models are widely used in lymphatic research due to their accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and anatomical and histological representation of human lymphedema.15 Structurally, gross anatomical swelling as a result of lymphadenectomy and radiotherapy observed in humans can also be replicated in mice. Similarly, histological sequelae, such as fibrosis, fatty tissue deposition, and immune cell infiltration, are frequently modeled in mice. Five of the highlighted mouse studies consistently observed at least one histopathological phenomenon (i.e., fibrosis, inflammation, or adipose deposition) after lymphedema induction (Table 2).19–23

Table 2.

Overview of mouse models of lymphedema

| Study (Year) | Animal Model | n (Total) | n with SL (%) | Method of SL Induction | Method of SL Evaluation | Effect of SL on Limb Measurements | Effect of SL on Fibrosis, Immune Cells, Adipose Deposition | Treatment | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mendez et al. (2012)26 | Mouse Forelimb | 20 | NS | Axillary lymph node excision | Forelimb thickness, rhodamine tracer, immunohistochemistry, fluorescence lymphangiography | +20% on day 10a +3% on day 25a |

N/A | Anti-VEGFR-3 antibodies | 60 days |

| García Nores et al. (2018)20 | Mouse Forelimb | 10 | NS | Axillary lymph node excision | Flow cytometry | N/A | Increased local CD4+ infiltrate | Diphtheria toxin | 42 days |

| Morfoisse et al. (2018)24 | Mouse Forelimb | 40 | NS | Axillary and brachial lymph node excision with partial mastectomy of the second mammary gland | Forelimb thickness, fluorescence lymphangiography, microwave sensor | +20–25% on day 14 | Increased fibrosis and dermal thickness | 17β estradiol pellets | 28 days |

| Bramos et al. (2016)33 | Mouse Hindlimb | 22 | 10/11 (89%) | Popliteal lymph node excision | Paw thickness, lymphatic drainage, immunohistochemistry | +19% on day 20 | Increased dermal thickness, mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate | 9-cis retinoic acid | 90 days |

| Frueh et al. (2016)19 | Mouse Hindlimb | 12 | NS | Popliteal lymph node excision | 3D volumetry, planimetry, circumferential length, paw thickness | +70% on day 3a +10% on day 28a |

Increased dermal thickness and dilated lymphatics on H&E | N/A | 28 days |

| Wiinholt et al. (2019)35 | Mouse Hindlimb | 50 | NS | Popliteal lymph node excision, 10 Gy radiation | Micro-CT | +60% on day 14a +37% on day 28a +21% on day 42a |

N/A | N/A | 56 days |

| Chang et al. (2013)38 | Mouse Tail | 56 | NS | Circumferential excision | Tail volume | +100% on day 14a | N/A | Indomethacin, other enzyme inhibitors, antioxidants | 14 days |

| Jang et al. (2016)16 | Mouse Tail | 20 | NS | Circumferential excision | Tail volume, immunohistochemistry, qRT-PCR | +57% on day 12a | Increased anti-F4/80 staining (macrophage) | Low-level laser therapy | 12 days |

| Gardenier et al. (2017)21 | Mouse Tail | 24 | NS | Circumferential excision | Tail volume, histology, lymphoscintigraphy | +50% on day 42a | Increased collagen and subcutaneous fat deposition, mononuclear cell response | Topical Tacrolimus 0.1% | 63 days |

| Gousopoulos et al. (2017)23 | Mouse Tail | 15 | NS | Circumferential excision | Tail diameter | +63.9% ± 26.5% on day 42 | Increased collagen and fat deposition, macrophage infiltration | High-fat diet | 42 days |

% Change in limb measurements was estimated based on data presented in figures and tables.

3D, three dimensional; CT, computed tomography; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; N/A, not applicable; NS, not stated; qRT-PCR, real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SL, secondary lymphedema; VEGFR-3, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3.

Mouse forelimb

Across the eligible studies, the mouse forelimb model of lymphedema was established using similar methods of axillary lymphadenectomy. After injecting dye into the paw, the axillary lymph nodes, prenodal and postnodal collecting lymphatics, and the associated fat are surgically excised. Of note, out of ten eligible studies using a mouse forelimb model, no study combined surgery with irradiation procedures. Morfoisse et al.24 modified this technique to test the effect of 17β-estradiol on lymphatic endothelial cells. Secondary lymphedema was induced through partial mastectomy of the second mammary gland in conjunction with axillary and brachial lymphadenectomy. By closely mimicking breast cancer surgery, this unique forelimb model was designed to be more clinically relevant to breast cancer-related lymphedema than other options.

A significant drawback of the mouse forelimb model is the rapid resolution of edema reported by several studies. For example, after a peak 20–25% volume increase, foot edema resolved within four weeks.24 The shortcomings in replicating chronic lymphedematous states were demonstrated in a study by Kwon et al.,25 in which minimally invasive axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) did not lead to differences in wrist diameter or arm area. A potential explanation for this phenomenon is that induction of acute lymphedema leads to changes in the interstitial forces that significantly increase the rate of fluid drainage in the mouse forelimb. After performing ALND, Mendez et al.26 blocked VEGFR-3 signaling by using antibody treatment, thereby inhibiting lymphangiogenesis. However, an insignificant difference in lymphatic drainage was observed. Furthermore, anatomical swelling resolved between postoperative days 10 and 60. Taken together, spontaneous resolution of lymphedema in their murine forelimb model occurred before lymphatic vessel regeneration, which precludes this model from consistently reflecting the chronic changes of secondary lymphedema.

Mouse hind limb

Based on our review of the literature, the mouse hind limb is a more commonly used model of lymphedema than the mouse forelimb. To induce lymphedema, a circumferential strip of skin and subcutaneous tissue is resected above the knee after injecting dye into the footpad. Out of 31 eligible studies, the most common combinations of removed lymph nodes were popliteal (n = 10), popliteal and inguinal (n = 7), popliteal and subiliac (n = 4), and inguinal (n = 3). In addition, the prenodal and postnodal lymphatic vessels are excised or ligated without disrupting the adjacent vasculature. Six studies did not remove lymph nodes during surgery; instead, these studies disrupted lymphatic function by electrocauterization of lymphatic vessels of the thigh or circumferential incision of the skin only.27–32

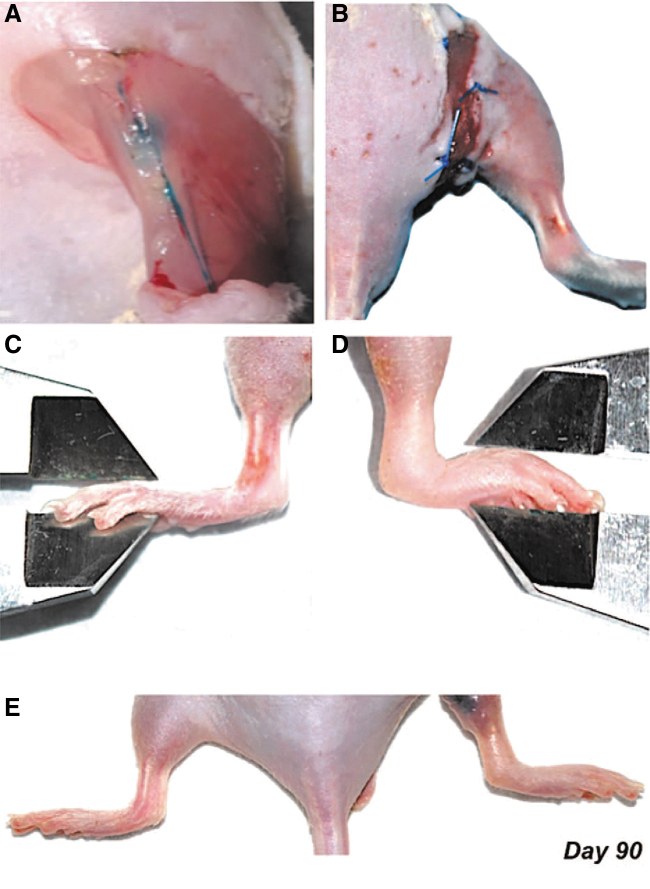

One strength of supplementing surgery with irradiation is the production of sustained lymphedema that mirrors the timeframe for chronic human lymphedema. Ten studies combined surgery with radiation, which exacerbated the extent of lymphatic dysfunction. Irradiation procedures varied extensively across studies in terms of anatomical field, timing, and dosage. In eight out of ten studies, a preoperative dose of irradiation within the range of 7.5–30 Gy was administered typically one week before surgical intervention. For example, using a combination of radiation and surgical injury, Bramos et al.33 explored the preventative and curative effects of 9-cis retinoic acid. After a dose of 20 Gy radiation, popliteal lymphadenectomy was reported to induce lymphedema in 89% of control mice, producing an average increased paw thickness of 19% that persisted until postoperative day 90 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Hind limb lymphedema after combined radiation injury and surgical lymphadenectomy.32 (A) Distal intradermal injection of Evans blue dye allows visualization of lymphatic vessels and popliteal lymph node before excision. (B) Circumferential full-thickness skin excision with a 2 mm wound gap disrupts the superficial dermal lymphatic system. (C) Representative example of a nonoperated hind limb and paw thickness being measured with a digital caliper. (D) Representative example of an operated hind limb from a control (vehicle treated) animal. Note the significant difference in lymphedema and paw thickness compared with the nonoperated hind limb and paw. (E) Representative example of hind limb lymphedema (right) compared with the nonoperated hind limb (left) 90 days after lymphadenectomy. Reprinted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.: Bramos et al.33 Color images are available online.

To determine the optimal timing and dosage of irradiation for this model, Jorgen et al.34 performed a comprehensive study that tested a range of doses (7.5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 Gy) and investigated the effects of a single preoperative dose versus a combined preoperative and postoperative dose. While several radiation dosages significantly inhibited lymph flow, the procedure that minimized adverse effects was combined surgical obstruction with two fractions of 10 Gy radiation. Other studies have demonstrated the efficacy of such an approach. Testing this hypothesis, Wiinholt et al.35 administered two doses of radiation and followed mice over a 56-day period. A dose of 10 Gy was administered to the mouse hind limb seven days prior to surgery, during which popliteal and inguinal nodes were removed. On postoperative day three, this was followed by repeat irradiation. In the following eight weeks, mean hind limb volume increased by up to 160% on day 14 and up to 121% on day 42. The resulting persistence of lymphedema was determined to closely represent the chronic lymphedematous state, which occurs months to years from initial lymphatic injury in humans.

A potential pitfall of the mouse hind limb model is that a chronic lymphedematous state is often elusive when lymphedema is induced by surgery in the absence of radiation. After performing inguinal lymphadenectomy, Komatsu et al.36 observed that acute edema in the hind limb began to resolve after postoperative day four. Furthermore, Kwon et al.37 report that removal of the popliteal lymph nodes without irradiation leads to no significant change in ankle thickness and cross-sectional leg area from axial computed tomography (CT) measurements taken 27 days after the operation. Finally, Frueh et al.19 performed popliteal lymph node excision and observed limb swelling for only up to 28 days compared to the contralateral unoperated limb. Thus, radiation may be a necessary addition to surgical excision to increase the duration of the lymphedematous state and better model human pathology.

Mouse tail

The mouse tail model is a highly popular model used to study lymphedema due to its simplicity and reproducibility. At a distance of 2–3 cm from the base of the tail, a circumferential, full-thickness incision is made to disrupt the dermal lymphatic system, and a 1–2 cm wide strip of tail skin is excised. The deep lymphatic vessels adjacent to the lateral tail veins are visualized by injecting dye into the distal end of the tail and are subsequently ablated under a surgical microscope. Across 41 studies that used the mouse tail model, there were only a few modifications to the surgical technique, which involved minor differences in skin incision size or distance between the base of the tail and skin incision.

One particular advantage of the mouse tail model is its correlation between excision size and degree of swelling, a phenomenon that is frequently observed in humans. In two mouse tail models, Gardenier et al.21 performed a 2-mm circumferential excision of the mid-tail section, while Chang et al.38 performed up to an 8-mm circumferential excision of the tail. The former reported a 50% increase in volume on day 42, while the latter reported a 100% increase on day 14. Jang et al.22 reported a 57% increase in tail volume by day 12, while Gousopoulos et al.23 noted a 63.9% increase in tail diameter by day 42. Due to differences in surgical techniques and recorded time points across research groups, the observed effect may vary across studies.

Another strength of this model is that the histological sequelae observed in a lymphedematous mouse tail mimics those seen in the progression of human lymphedema. Fibrosis, fat deposition, and infiltration of immune cells have been identified as key processes in the pathogenesis of lymphedema.39–41 As a result, many studies have investigated potential treatments to ameliorate these detrimental effects.42,43 Recently, Gardenier et al.21 described a role for topical tacrolimus, an anti-T cell agent, in dampening the fibrotic response in a mouse tail model. Early (postoperative day 14) and late (postoperative day 42) topical tacrolimus treatment resulted in significantly reduced collagen type I deposition and scar index, as well as decreased infiltration of leukocytes in the dermis and subcutaneous fat layers.

Despite its low cost and well-documented nature, the mouse tail model has several shortcomings in its ability to effectively model human lymphedema. The most obvious limitation is its clinical relevance from an anatomical standpoint because of the lack of an anatomically similar appendage in humans. The mouse tail is not subject to the same gravitational forces experienced in human limbs, which have been documented to exacerbate the progression of lymphedema.33 In addition, mice have been reported to experience spontaneous lymphatic regeneration due to their small size.15 Three studies that followed tail volume changes for at least 25 days observed an initial peak in tail volume followed by a gradual decline, indicative of resolution.19,26,44 Mouse models exhibiting short lymphedematous states with spontaneous resolution may confound therapies intended to target the chronic lymphedematous nature in humans. Although the use of irradiation procedures in a mouse tail model is quite rare (3 out of 41 mouse tail studies), it is possible that irradiation can prevent the spontaneous resolution of lymphedema.14

Rat

Rat models yield similar advantages and disadvantages as mouse models. A rat model of lymphedema allows for clearer gross visualization of its cervical, inguinal, and popliteal lymphatics due to its larger anatomical size. Only a few recent rodent studies reported success rates of lymphedema induction (Table 3). This may be attributed to their well-documented nature in the literature, accessibility, and relatively simple nature of procedures. Nevertheless, the possibility of infection or necrosis must be taken into consideration during the experiment planning, as success rates may be influenced by a multitude of factors, such as experience with microsurgical techniques and postoperative management of the surgical site.

Table 3.

Overview of rat models of lymphedema

| Study (Year) | Animal Model | n (Total) | n with SL (%) | Method of SL Induction | Method of SL Evaluation | Effect of SL on Limb Measurements vs. Control | Effect of SL on Fibrosis, Immune Cells, Adipose Deposition | Treatment | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puscas et al. (2018)45 | Rat Forelimb | 50 | NS | Axillary lymph node excision | Forelimb volume | +48.89% ± 24.88% on day 21 | Mononuclear cells; fibrosis at lymphadenectomy site | Intense physical activity, antioxidants | 21 days |

| Lynch et al. (2015)46 | Rat Forelimb | 40 | NS | Axillary lymph node excision | Forelimb volume, ICG fluorescence lymphography, Masson's Trichrome staining | +11% on day 64 | Fibrosis | Bleomycin | 64 days |

| Triacca et al. (2018)47 | Rat Hindlimb | 16 | NS | Popliteal and inguinal lymph node excision 22.7 radiation |

Hindlimb volume, lymphofluoroscopy, skin dielectric constant | +27% on day 56 | N/A | Implantation of drainage device | 56 days |

| Matsumoto et al. (2018)48 | Rat Hindlimb | 20 | NS | Amputation and replantation | Ankle circumference, ICG fluorescence lymphography, immunohistochemistry | +26% on day 3a | N/A | N/A | 14 days |

| Kawai et al. (2014)52 | Rat Tail | 45 | NS | Circumferential excision | Tail circumference, ICG fluorescence lymphography, immunohistochemistry | +33% on day 35a | N/A | Transplantation of human LECs or unpurified HDMECs | 36 days |

| Serizawa et al. (2011)53 | Rat Tail | 90 | NS | Circumferential excision | Tail volume, ICG fluorescence lymphography, qRT-PCR, immunohistochemistry, biochemical analysis | +25% on day 25a | N/A | Extracorporeal shock wave therapy | 25 days |

| Daneshgaran et al. (2019)50 | Rat Head and Neck | 36 | 18/20 (90%) | Circumferential excision of superficial and deep cervical lymph nodes 27.5 Gy radiation |

Head and neck circumference, MRI fat volume analysis, ICG fluorescence lymphography, immunohistochemistry, picrosirius red staining, qRT-PCR | 11% on day 60a | Increased collagen deposition, TGF-β1 expression, infiltration of CD3+ T lymphocytes, fat volume on MRI | N/A | 60 days |

% Change in limb measurements was estimated based on data presented in figures and tables.

ICG, indocyanine green; LEC, lymphatic endothelial cell; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; qRT-PCR, real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor beta 1.

Rat forelimb

Due to the high degree of anatomical homogeneity between rats and mice, the surgical methods for forelimb lymphedema are almost identical. For example, a 10-mm long incision is made across the axilla of the rat, and the axillary lymph nodes and associated prenodal and postnodal collecting lymphatic vessels are excised. Subsequently, Puscas et al.45 investigated the effect of intense physical exercise and antioxidant supplementation on chronic lymphedema in the rat forelimb by performing ALND. After 21 days, the limb volume of all animals increased significantly by an average of 48.9%. Infiltration of mononuclear immune cells and mastocytes, as well as signs of severe fibrosis were observed at the site of lymph node removal.45 Consequentially, fibrosis plays an important role in suppressing lymphangiogenesis in the rat forelimb model. By exacerbating fibrosis with bleomycin, Lynch et al.46 demonstrated significant increases in wrist diameter and the persistence of these measurements by postoperative day 64. Although the rat forelimb model is seldom used, it offers a viable option that reflects the chronic nature of lymphedema in cases of severe fibrotic scarring.

Rat hind limb

For the rat hind limb model, a dye is injected into the distal end of the paw to visualize the lymphatic system. After making a circumferential incision in the dermal and subcutaneous layers, the lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels are resected. In most cases, the inguinal fat pad is excised to remove the inguinal lymph nodes. Out of the 16 eligible studies, 11 utilized the rat hind limb model to perform both inguinal and popliteal lymphadenectomies, while the remainder performed inguinal only (n = 3), popliteal only (n = 1), or vessel ligation only (n = 1). Matsumoto et al.48 introduced an original approach of acute lymphedema induction by amputating the rat hind limb at the groin line and between the inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes. Replantation surgery was performed immediately after amputation. The femoral bone was internally fixed, and the femoral artery and vein were combined through microsurgical anastomosis, while the lymphatic vessels were not. Finally, the muscle, subcutaneous, and skin layers were sutured.

Similar to its mouse counterpart, surgery can be combined with irradiation to spur a more robust development of lymphedema in the rat hind limb. Nine studies incorporated postoperative radiation to the groin area. Although the dosage varied among studies, Yang et al.49 concluded that out of 20, 30, or 40 Gy radiation, removal of both inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes followed by a dose of 20 Gy on postoperative day 7 minimizes the morbidity and mortality rates in Sprague-Dawley rats. Most studies opted to administer a single dose of irradiation rather than fractionated doses. Some notable exceptions include a study by Daneshgaran et al.50 in which rats were given a clinically relevant 27.5 Gy dose administered over five days. In addition, Harb et al.51 investigated a single dose of 22.7 Gy versus a cumulative dose of 40.5 Gy delivered in 15 fractions, although a definitive conclusion could not be made because the cumulative dose was not combined with a circumferential skin incision.

Rat tail

Although the rat tail model is rarely selected for lymphedema studies, it has some uses due to its relative ease. Similar to the mouse tail surgery that was previously described, a circumferential incision is made distal to the base of the tail, and the dermis and underlying deep lymphatic vessels are excised. Due to their larger size, it is possible to perform the procedure under loupe magnification instead of a surgical microscope, which is necessary for tail surgery in mice. According to a study by Kawai et al.,52 successful induction of lymphedema in nude rats led to a 33% increase in the tail circumference on day 35. These findings are consistent with another study by Serizawa et al.53 in which lymphedematous tails in Sprague-Dawley rats increased in volume by 25% on day 25. The rat tail model may not demonstrate as significant changes in gross measurements as in the mouse tail model, which has been shown to exhibit increases in tail volume between 50% and 100% (Table 3). This phenomenon, coupled with higher costs of animal procurement and husbandry, may explain the popularity in the application of the tail model to mice rather than to rats.

Rat head and neck

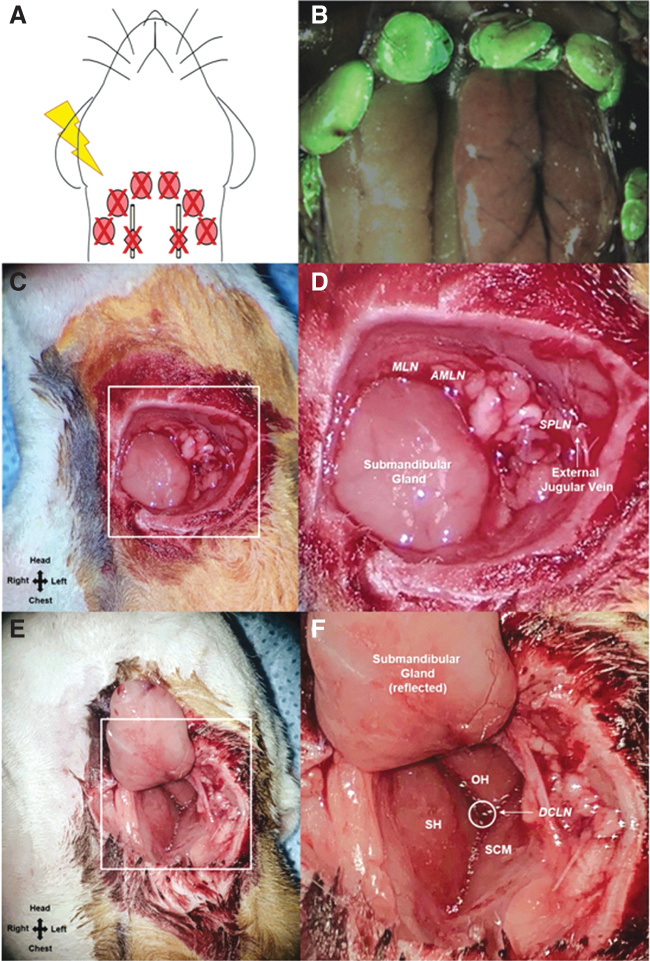

In a first study of its kind, Daneshgaran et al.50 developed a reproducible model of head and neck lymphedema in Prox1-EGFP rats. Through a dissecting microscope, a full-thickness skin incision was made circumferentially around the neck, and the superficial and deep cervical lymph nodes were excised. The surgical area was irradiated with a dose of 27.5 Gy delivered over five consecutive days (Fig. 3). Lymphedema was evaluated by neck circumference, face width measurements, and magnetic resonance imaging fat volume analysis. Lymphatic clearance was assessed by indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence lymphography and histological staining. In the combined lymphadenectomy and irradiation group, postsurgical lymphedema was observed in all animals. The cervical excision resulted in gross head and neck swelling beginning on postoperative day 15. Impaired lymphatic drainage, and histological changes that are key indicators of lymphatic dysfunction in humans, such as increased fibrosis, inflammatory response, and fat deposition, were also observed. One aspect to note of this head and neck model is the risk of infection; the necrosis and infection rate were reported to be 10%, and thus, the number of animals was doubled in anticipation of excluded rats.50

Figure 3.

Schematic of the cervical lymphadenectomy model, including identification and removal of cervical lymph nodes using Prox1-EGFP lymphatic reporter rats.49 (A) To induce cervical lymphedema, rats underwent surgical dissection of the superficial cervical lymph nodes (red ovals) and deep cervical lymph nodes (red diamonds overlying the carotid sheath) followed by irradiation. (B) Superimposed images of superficial cervical lymph nodes located around the submandibular glands and the same lymph nodes under green fluorescence microscopy in a Prox1-EGFP lymphatic reporter rat. (C) Intraoperative image of rat neck identifying the field of view for D. (D) Identification of the superficial cervical lymph nodes: MLN located superiomedial to the submandibular gland, AMLN located superiolateral to the submandibular gland, SPLD overlying the external jugular vein. (E) Intraoperative image of rat neck identifying the field of view for F. (F) Identification of the DCLN located deep to the junction of the SH, OH, and SCM muscles and overlying the carotid sheath. AMLN, accessory mandibular lymph node; DCLN, deep cervical lymph nodes; MLN, mandibular lymph node; OH, omohyoid; SCM, sternocleidomastoid; SH, sternohyoid; SPLD, superficial parotid lymph node. Reprinted from Daneshgaran et al.50 Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY. Color images are available online.

Rabbit

Rabbit models of lymphedema have grown in popularity due to their ease. One of the rabbit model's advantages over rodent models is size, which has allowed for wider vessel selection in procedures, such as vascularized lymph node transplantation.54 In addition, greater follow-up times have demonstrated that effects of limb swelling can persist long term in contrast to the spontaneous resolution of lymphedema previously reported in rodents. Lymphedematous hind limb volume remains highly stable from postoperative months three to nine, which suggests that the rabbit hind limb model can effectively mimic the chronic nature of human disease progression.55

Rabbit ear

The rabbit ear model offers a microsurgical approach of inducing secondary lymphedema with a relatively rapid disease progression. Two studies in particular produced lymphedema by circumferential excision at the ear and evaluated disease progression by ear thickness, hematoxylin and eosin staining, and immunohistochemistry (Table 4). Kubo et al.56 removed a strip of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and perichondrium from the ear base, but preserved a section of dorsal skin called a “skin bridge.” The skin bridge is the only section on the dorsal ear available for lymphatic regeneration, thus facilitating histological analysis.45,56 All animals developed lymphedema in both ears. Despite the risk for cartilage necrosis due to the removal of the perichondrium, all animals survived to the experimental endpoint without local complications.56 However, a potential pitfall of this model is its reliability; only 80% of animals developed chronic swelling that lasted for at least 12 months postoperatively.55

Table 4.

Overview of rabbit models of lymphedema

| Study (Year) | Animal Model | n (Total) | n with SL (%) | Method of SL Induction | Method of SL Evaluation | Effect of SL on Limb Measurements | Effect of SL on Fibrosis, Immune Cells, Adipose Deposition | Treatment | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiang et al. (2010)59 | Rabbit Hindlimb | 6 | 6/6 (100%) | Microsurgical ablation of groin lymph nodes and vessels, limited field groin irradiation | Lymphoscintigraphy, 3D dynamic contrast-enhanced MRL | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 weeks |

| Zhou et al. (2011)55 | Rabbit Hindlimb | NS | 80% | Surgical excision of groin lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels 20 Gy radiation |

Water displacement volumetry, immunohistochemistry, Western blot analysis | NS | N/A | Bone marrow stromal cell transplantation and VEGF-C | 9 months |

| Penuela et al. (2019)54 | Rabbit Hindlimb | 8 | NS | Popliteal lymph node excision | Hindlimb volume by truncated cone formula, H&E staining | +41% on day 15a | N/A | Vascularized lymph node transfer | 30 days |

| Penuela et al. (2018)57 | Rabbit Ear | 7 | 7/7 (100%) | Total skin denudation and microsurgical destruction of the lymph channels and blood vessels | Ear thickness, H&E, immunohistochemistry, picrosirius red staining | +46% on day 7a | Increased fibrosis on day 15 | Lymphovenous anastomosis | 30 days |

| Kubo et al. (2010)56 | Rabbit Ear | 7 | NS | Circumferential excision of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and perichondrium; lymphatic vessel excision | Ear thickness, H&E, Western blot, immunohistochemistry | NS | NS | Extracorporeal shock wave therapy | 4 weeks |

% Change in limb measurements was estimated based on data presented in figures and tables.

MRL, magnetic resonance lymphangiography; VEGF-C, vascular endothelial growth factor C.

Building upon prior studies, Penuela et al.57 described a reproducible ear model in New Zealand White rabbits, in which they performed circumferential excision. Lymphatic and blood vessels were excised with either a scalpel, thermal electrocautery, or sutures. Within one week of lymphedema induction, the ear thickness peaked, and by three weeks, the swelling subsided, while ear thickness remained stable.57 With the presence of collagen deposition, but lack of macrophage infiltration, Penuela et al.57 attributed this to the rabbit ear's innate ability to heal quickly, which is in accordance with previous reports of rabbit ear scar formation within three to four weeks following trauma.45,54,58 In contrast, the former study by Kubo et al.56 circumvented the rapid healing process by utilizing the skin bridge and did not report a significant difference in ear volume until four weeks after shockwave therapy. Meanwhile, Penuela et al.57 reported a maximum increase in ear thickness observed on postoperative day 7 that plateaus between postoperative days 15 and 20. Nevertheless, the timeline for lymphedema induction and maintenance in the rabbit ear model must be considered. While a follow-up period of a mere three to four weeks may not be considered sufficient to assess chronic human lymphedema, histopathological evidence in rabbit ear models demonstrated otherwise. Perhaps, lymphedema development in rabbit ear models must be evaluated on an accelerated timeline.

Rabbit hind limb

In the rabbit hind limb model, popliteal lymphadenectomy, which is the most common method of lymphedema induction, was performed by all three eligible studies. Meanwhile, similar to protocols used in smaller rodent models, two of these hind limb studies incorporated postoperative radiation (Table 4). In New Zealand white rabbits, the lymph node and lymphatic vessels of the groin were ablated under a microscope, followed by groin irradiation. All rabbits successfully developed obstructive lymphedema in the operated hind limb.59 On postoperative day three, 20 Gy was administered to the groin area.55 Chronic lymphedema, defined as chronic swelling lasting longer than 12 months, was produced in 80% of animals, while the mean change in limb volume was 160% on postoperative day 28.55 Bone marrow stromal cell transplantation and vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) administration led to decreased limb volume and increased lymphatic vessel density. In a more acute hind limb model, Penuela et al.54 examined the effect of vascularized lymph node transfer (VLNT). While radiation was not used in this study, popliteal lymph node and lymphatic vessels were excised from the left hind limb of New Zealand White rabbits. Limb volume was estimated by measuring the perimeter of the hind limb every 2 cm from the ankle to the knee. VLNT in the lymphedematous limb resulted in a significant reduction in hind limb volume by postoperative day 30. However, lymphedema resolution has been reported in their prior study.57 Taken together, these studies demonstrate the advantages of following animal models over longer periods, especially in an attempt to extrapolate the lymphedema described by animal studies to that seen in the clinic.

Sheep

While small animals provide a cost-effective means to study lymphedema, large animals provide advantages, such as more accurate quantification of lymphatic function. Due to their size, larger animal models allow for relative ease in gross visualization of surgical sites and lymphatic targets. For example, groups can utilize methods such as injection of 125iodine radiolabeled bovine serum albumin to evaluate the lymphatic network's ability to transport protein from interstitial space back into venous circulation. Such techniques are only possible with vessels of sufficient size for cannulation.60

Sheep hind limb

The sheep hind limb model of secondary lymphedema is an excellent option with high reliability. Baker et al.60 report that the removal of a single popliteal lymph node and associated vessels produced lymphedema in all 50 sheep. Changes in limb circumference lasted for six weeks postoperatively.60 Lymphedema induction produced consistent findings with a previous study, indicating that swelling persisted for 16 weeks after surgery in 38 out of 41 sheep.61 After the popliteal lymph node excision, growth factor therapy was administered. Leg measurements revealed that the lymphadenectomy control group had significantly higher edema after six weeks. Lymphatic transport was quantified using radiolabeled bovine serum albumin injection, and lymphatic networks were imaged by fluoroscopy with lipiodol injection. Overall, growth factor therapy promoted lymphangiogenesis, improved lymphatic function, and reduced postoperative edema. However, one of the model's shortcomings is that the degree of lymphatic injury is significantly less severe than what is typically seen in human cancer patients. Although the removal of one lymph node may produce acute lymphedema in the hind limb of a sheep, human patients may undergo a combination of complex procedures, including multiple surgeries, radiotherapy, and lymphadenectomy, which culminate in chronic lymphedema.60

While this model examines an isolated hind limb lymphatic network, the goal, in line with both small and large animal models, is not to necessarily replicate the complete multifaceted system of human lymphedema. For instance, formation of lymphovenous anastomosis observed in chronic lymphedema patients was not observed in the popliteal region of the sheep model.60 Similarly, the degree of lymphatic impairment in sheep was also reduced. While the success rate of their induction technique was relatively high, Baker et al. did not follow their model for longer than 6 weeks, despite the lack of clinical symptoms observed in patients for up to a year.60 Direct comparisons remain a challenge. Although the definitions of lymphedema are not well established across species, physiological phenomena in humans are nevertheless present and can still be observed in animals. Thus, these models are sufficient as a valuable starting point to assess the pathological consequences and therapeutic options of lymphedema.

Dog

The complex nature of lymphatic networks in large animals closely resembles that of the human body, bringing these models closer in clinical translatability. Recently, canine hind limb models have shown promise as a relevant option due to the high degree of similarity between the lymphatic systems of dogs and humans. Suami et al.62 introduced the concept of lymphosomes, which are areas of skin or soft tissue that drain to nodes in the corresponding lymphatic basins, drawing parallels between the lymphatics of dogs and humans.

Dog forelimb

After mapping the entire superficial lymphatic system of four mongrel carcasses, Suami et al.62 successfully developed a novel canine model of the forelimb. In two mongrel dogs, ICG was injected in interdigital web spaces of the foot or the elbow joint. The axillary lymph node and associated structures were excised. By postoperative day ten, these dogs exhibited increased elbow swelling of 14.5–18.1%. However, swelling at the forelimb resolved by postoperative week three.

Building upon this initial study, Suami et al.63 investigated VLNT on postsurgical lymphedema in the canine forelimb after resection of the superficial cervical and axillary nodes. Three days later, the surgical site was irradiated with 15 Gy. Secondary lymphedema was assessed using ICG fluorescence lymphography, lymphangiography, forelimb measurements, CT, radiography, and histology (Table 5). Only one of two canines developed chronic lymphedema, which was diagnosed by increased girth of the distal forearm after 12 months, mirroring the chronic nature of disease in humans.63 The second canine demonstrated no significant change in limb circumference after one month. VLNT showed promise as a treatment for lymphedema by stimulating the formation of new lymphatic drainage pathways, leading to decreased limb swelling.

Table 5.

Overview of large animal models of lymphedema

| Study (Year) | Animal Model | n (total) | n with SL (%) | Method of SL Induction | Method of SL Evaluation | Effect of SL on Limb Measurements | Effect of SL on fibrosis, immune cells, adipose deposition | Treatment | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al. (2010)60 | Sheep Hindlimb | 50 | 50/50 (100%) | Popliteal lymph node excision | Leg circumference, radiolabeled BSA, lipiodol lymphangiography | +35% on day 42a | N/A | VEGF-C and ANG-2 administration | 6 weeks |

| Suami et al. (2013)63 | Dog Forelimb | 2 | 2/2 (100%) | Superficial cervical and axillary node excision | Forelimb circumference, ICG fluorescence lymphography, radiographic microinjection | +14.5–18.1% on day 10 | N/A | N/A | 6 months |

| Suami et al. (2016)78 | Dog Forelimb | 2 | 1/2 (50%) | Superficial cervical and axillary node excision 20 Gy radiation |

Forelimb circumference, ICG fluorescence lymphography, radiographic microinjection, lymphangiography, CT, H&E | NS (swelling peaked after 1.5 months) | N/A | Vascularized lymph node transfer | 18 months |

| Blum et al. (2010)69 | Pig Hindlimb | 26 | NS | Lymphadenectomy of both groins | Tc-99 m-NC-SPECT/CT lymphoscintigraphy | No significant increases postoperative 5 or 8 months | N/A | Lymph node transplantation | 8 months |

| Lahteenvuo et al. (2011)71 | Pig Hindlimb | 16 | NS | Inguinal node excision Autologous transfer of pedicular lymph node |

Seroma volume, Lipiodol X-ray lymphangiography, Patent Blue and Evans Blue injection, H&E, immunohistochemistry, Western blot | N/A | N/A | VEGF-C or VEGF-D administration | 2 months |

| Hadamitzky et al. (2016)73 | Pig Hindlimb | 16 | NS | Superficial right inguinal, right popliteal lymph node excision 15 Gy radiation |

Multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analysis, CT imaging of lymphatics, H&E staining, immunohistochemistry | N/A | Fibrous ear tissue (untreated), minimal | Nanofibrillar scaffolds | 3 months |

| Wu et al. (2014)76 | Monkey Upper Limb | NS | NS | Axillary lymph node excision 30 Gy radiation at preoperative week 2 and postoperative week 4 |

Limb circumference, high-resolution magnetic resonance lymphography, bioelectrical impedance analysis, immunohistochemistry | +37% at 24 months; palm thickness +15–40% | N/A | N/A | 24 months |

% Change in limb measurements was estimated based on data presented in figures and tables.

VEGF-D, vascular endothelial growth factor D.

Nevertheless, canine models present challenges, such an inability to consistently produce lymphedema, the mortality rate, and cost. The rate of lymphedema induction has been reported to range from 60% to 80%, while key studies identified in our review observed clinical manifestations in all dogs under limited sample sizes.63–65 In an example of a larger study, Chen et al.66 report twelve of seventeen dogs that underwent irradiation and lymphedema surgery met the criteria for lymphedema (>15% increase in limb size compared to control hind limb), two dogs did not (5–15% increase in limb size), and the remaining three suffered complications of infection.66 High costs and mortality rates of the model pose significant risks even though recent studies suggest that the lymphatic system of dogs shares similarities with that of humans. Further investigation is necessary to accurately assess the reliability of the canine model.

Pig

Among large animals, pigs have also had lymphosomes mapped, and significant homology has correlated swine lymphatic networks to those of humans.67 As a result, pig lymphatics can also be identified by ICG lymphography. Due to their size, pigs are compatible with more advanced visualization techniques, such as CT, allowing for precise visualization of lymph nodes and vessel regeneration in a porcine model.68,69 This technique is also used clinically to identify lymph nodes in breast cancer patients to avoid incidental irradiation exposure of off-target nodes during treatment.70

Pig hindlimb

Lahteenvuo et al.71 induced lymphedema in the hind limb of domestic pigs by excising the afferent and efferent lymph vessels proximal and distal to the superficial inguinal lymph node. The pedicular lymph node was attached laterally from its original position. Viral vectors encoding the prolymphangiogenic vascular endothelial growth factors C and D (VEGF-C/D) were injected into the inguinal lymph node, which significantly improved the function of lymphatic flow and increased the density of lymphatic vessels. In subsequent experiments, the requirement of VEGF-C for lymphangiogenesis due to its interaction with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) and VEGFR-3 was confirmed in a pig model.72

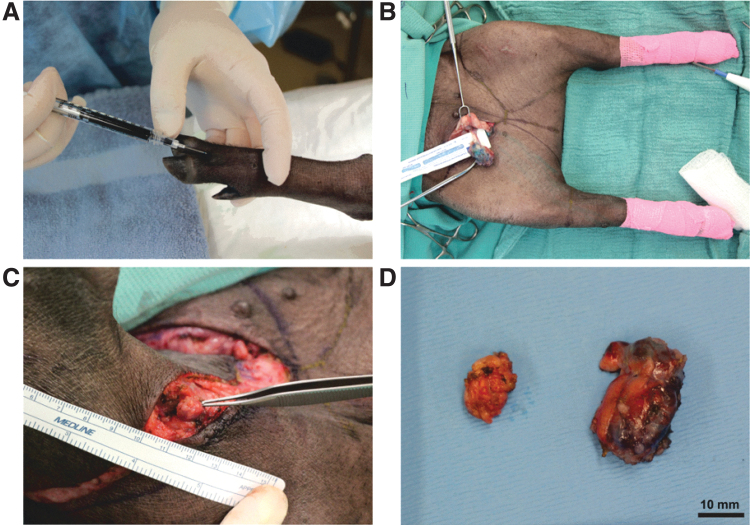

Meanwhile, two of five porcine studies performed lymphadenectomy of the inguinal lymph nodes. Blum et al.69 explored the effects of lymph node auto-transplantation on Gottingen minipigs after superficial inguinal lymph node resection. Lymph nodes were fragmented and retransplanted to the groin. At postoperative five and eight months, no significant increase in hind limb diameters was observed. Lymphatic obstruction and dermal backflow were noted frequently with retransplantation of smaller pieces, while larger fragments were commonly reintegrated into the lymphatic system. In the second groin lymphadenectomy study, Hadamitzky et al.73 evaluated the efficacy of aligned nanofibrillar collagen scaffolds after resection of both superficial inguinal and right popliteal lymph nodes, followed by a dose of 15 Gy on postoperative day 14. Scaffold treatment revealed increased LYVE-1+ lymphatic collectors in close proximity to the scaffolds at the three-month endpoint. In addition to a reduction in the bioelectrical impedance ratio in the scaffold-treated group, a significant increase in the number of de novo lymphatic collectors was observed on CT. Our group has recently attempted to induce lymphedema in the hind limb of Yucatan minipigs by combined inguinal and popliteal lymphadenectomy after visualization of lymphatic networks by methylene blue dye injection (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Lymphadenectomy of inguinal and popliteal nodes in Yucatan minipigs. (A) Methylene blue injection of the experimental right hindlimb. (B) Lymphadenectomy of the right inguinal node and methylene blue dye visualization of lymphatic vessels. (C) Lymphadenectomy of the right popliteal node. (D) Specimen of inguinal (right) and popliteal (left) nodes. Color images are available online.

One significant limitation of the swine lymphatic network is the absence of axillary lymph nodes.67 Since a large portion of clinical secondary lymphedema is a result of axillary lymphadenectomy, mimicking the progression of disease from initial lymphatic injury in swine remains a challenge. A pitfall of the pig hind limb model is the absence of macroscopic changes in limb volume or circumference. Out of 26 Gottingen pigs, Blum et al.69 noted no significant change in the diameters of hind limbs after five and eight months postoperatively. Immediately after lymph node removal, Lahteenvuo et al.71 reported accumulation of seroma in the inguinal region, which spontaneously resolved by two weeks. Although evaluation of lymphatic function supported the prolymphangiogenic effects of the treatments under investigation, current evidence indicates that the porcine hind limb model does not encapsulate changes in limb size as seen in severe cases of human lymphedema.

Monkey

Use of non-human primates in translational research offers an extremely valuable opportunity to model human diseases. The close phylogenetic relationship between primates and humans allows studies to produce results with higher validity than with other animal models.74 Non-human primates share genetic, immunological, and anatomical similarities with humans to a greater extent than rodents, rabbits, and dogs, which is highly relevant for secondary lymphedema.75 In contrast to a rodent tail, which humans lack, and a pig limb, which lacks axillary nodes, a monkey model carries more homologous structures while subjected to similar gravitational forces as humans. This opens up new possibilities for investigating human lymphedema in a model that may be clinically relevant to a greater extent than the frequently employed small animals.

Monkey upper limb

Due to strong homology between primates and humans, Wu et al.76 describes the first reproducible rhesus monkey model of upper extremity lymphedema. Axillary lymph nodes were dissected, and drainage lymphatic vessels along with the subcutaneous fat and deep lymphatic tissues were excised and irradiated with two doses 30 Gy before and after surgery. Upper extremity morphology was assessed with water displacement and tape measurements. At three months, magnetic resonance lymphography indicated pathologic changes in lymphatic vessel structure, such as disappearance of major lymphatic trunks and delayed lymphatic flow. Bioelectrical impedance analysis revealed increased water content, while immunohistochemistry demonstrated dilated lymphatic vessels in the affected limb. Over a period of 24 months, the circumference of the lymphedematous limb increased by up to 137%. Overall, the authors produced a successful model of upper limb lymphedema in rhesus monkeys that demonstrates pathologic changes consistent with the progression of human disease.

Research involving non-human primates also brings forth major financial and ethical concerns. In addition to high costs of procurement and husbandry, the use of non-human primates is surrounded by controversy centered around the moral justification of inducing pain and suffering to another species with such high cognitive capacity.76,77 Another disadvantage is that in contrast with inbred rodent strains that are genetically identical, non-human primates can exhibit outbred genetic variation. When combined with low sample sizes, these differences in genotype could not only confound results but also lower the statistical power of the study.76 All of these constraints must be thoroughly examined before selecting a primate model of lymphedema.

LIMITATIONS

Even though our methodology provides a comprehensive update of recent animal lymphedema models reported within the last ten years, this review has a few important limitations. A meta-analysis was not performed because the eligible studies were too heterogeneous to be directly compared. Future reviews could implement a more focused set of inclusion and exclusion criteria, such as limiting the species, surgical induction technique, or follow-up period, to achieve higher levels of homogeneity for a potential meta-analysis. Comparing models across various species or anatomical locations is problematic because the qualitative and quantitative parameters for assessing lymphedema in an animal model vary significantly across studies. Even within the same model, the direct comparison of results becomes challenging due to differences in animal conditions across laboratories coupled with varying surgical techniques across users. However, this is also reflective of the cost and time constraints faced by investigators when selecting an animal model to pursue.

Finally, small and large animal models of lymphedema pose unique challenges in translation to human disease. There lacks an agreement on standards of measurement, such as the onset of lymphedema and extent of lymphatic injury. Small animals, such as rodents, may face issues of acute onset and spontaneous resolution, which varies with the model's lymphedema induction technique. On the other hand, large animals, such as pigs, may not develop grossly appreciable lymphedema at all. Not all clinical features observed in human lymphedema are necessarily present in or can be replicated by a given system. Interspecies comparisons are an undeniable challenge, and each model must be assessed by their own merits and limitations.

CONCLUSION

Due to its extreme morbidity, secondary lymphedema requires further scientific investigation, but selecting an appropriate model remains a challenge. While an ideal model does not exist, we offer an updated guide of animal models of lymphedema used within the past decade to assist researchers in their decision-making process. We provide a breadth of animal model pursuits and present the diversity in induction, evaluation, and treatments. Important factors to consider when choosing a model include clinical translatability, reliability, cost, and requirements for radiation or microsurgery (Table 6). While small animal models are simple to reproduce, cost-effective, and exhibit clinical manifestations of lymphedema relatively quickly, these models are often limited by clinical translatability. Large animal models closely mimic the lymphatic system of humans and display chronic effects similar to severe lymphedema, but require a greater investment of resources due to higher costs, longer follow-up times, and potential issues with model consistency. Ultimately, researchers must select the model that not only fulfills the requirements of their experiment but also fits within the unique constraints of their specific study.

Table 6.

Comparison of animal lymphedema models

| Animal | Anatomical Location | Number of Studiesa | Number of Studies with Radiation | Cost | Clinical Relevance | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Forelimb | 10 | 1/10 (10%) | ☆ | ☆☆ | • Low cost • Mouse lymphedema surgeries are relatively simple • Irradiation procedures can be used in combination with therapy |

• Clinical translatability may be limited due to spontaneous resolution of acute lymphedema in mice • The mouse's small size makes microsurgical equipment and training necessary |

| Hindlimb | 31 | 9/31 (29%) | ☆ | ☆☆ | |||

| Tail | 41 | 3/41 (7%) | ☆ | ☆ | |||

| Rat | Forelimb | 2 | 0/2 (0%) | ☆ | ☆☆ | • Low cost • Rat lymphedema surgeries are relatively simple • Irradiation procedures can be used in combination with therapy • A model of head and neck lymphedema exists in rats |

• Clinical translatability may be limited due to differences in genomic responses to disease between rodents and humans • The head and neck model lymphedema may be associated with a risk for infection or necrosis |

| Hindlimb | 16 | 9/16 (56%) | ☆ | ☆☆ | |||

| Tail | 2 | 0/2 (0%) | ☆ | ☆ | |||

| Head and Neck | 1 | 1/1 (100%) | ☆ | ☆☆ | |||

| Rabbit | Hindlimb | 3 | 2/3 (66%) | ☆☆ | ☆☆ | • Limb swelling occurs quickly and persists during long-term follow-up | • Reliability may be limited in producing lymphedema |

| Ear | 2 | 0/2 (0%) | ☆☆ | ☆ | • Ear thickness swelling and fibrosis occurs rapidly | • Reliability has not been supported extensively | |

| Sheep | Hindlimb | 1 | 0/1 (0%) | ☆☆ | ☆☆ | • Preliminary studies demonstrate high reliability • Model is compatible with more precise visualization of lymphatic function (e.g., 125I-BSA) |

• Further studies are needed to support high reliability shown in previous studies |

| Dog | Forelimb | 2 | 1/2 (50%) | ☆☆ | ☆☆ | • The canine lymphatic system closely resembles that of humans → increased clinical relevance to humans | • Reliability may be limited in consistently producing lymphedema (60–80%) • Risk of infection, mortality rate |

| Pig | Hindlimb | 5 | 1/5 (20%) | ☆☆ | ☆☆ | • Model is compatible with more precise visualization of lymphatic structure (e.g., SPECT/CT) | • Limb circumference changes are not observed in preliminary studies |

| Monkey | Upper Limb | 1 | 1/1 (100%) | ☆☆☆ | ☆☆☆ | • Most similar to humans → highest clinical translatability among animal models | • High costs of procurement and husbandry • Ethical concerns of non-human primate use in research |

The sum of the “Number of Studies” column in table is greater than 111 studies that met the inclusion criteria because some studies used two or more animal models.

☆ = low, ☆☆ = medium, ☆☆☆ = high.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

Postsurgical lymphedema is commonly caused by oncological procedures, such as lymphadenectomy.

Treatments for lymphedema are severely limited.

Animal models have been essential to lymphatic research, helping us better characterize lymphedema and providing a medium to explore novel therapies.

Small animal models are relatively simple and cost-effective, but their clinical relevance is limited.

Large animal models are more clinically translatable, but cost and management may be a challenge for investigators.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 3D

three dimensional

- ALND

axillary lymph node dissection

- CT

computed tomography

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- ICG

indocyanine green

- LEC

lymphatic endothelial cell

- LYVE-1

lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MRL

magnetic resonance lymphangiography

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- qRT-PCR

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor beta 1

- VEGF-C

vascular endothelial growth factor C

- VEGF-D

vascular endothelial growth factor D

- VEGFR-2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2

- VEGFR-3

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3

- VLNT

vascularized lymph node transfer

Appendix Table A1.

Systematic review search algorithm

| Database | Search Terms | No. of Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“Disease Models, Animal”[MeSH Terms] OR “Animal Model” OR (“Animal Model” AND (“Disease” OR “Laboratory” OR “Experimental”))) AND (“Lymphedema”[MeSH Terms] OR “Lymphedema” OR “Lymphatic Injury”) AND (“2010/01/01”[PDat]: “2020/12/31”[PDat]) NOT (“editorial”[pt] OR “letter”[pt] OR “comment”[pt]) |

153 |

| Embase | (“disease model” OR “disease model”/exp OR “animal model” OR “animal model”/exp OR ((“animal model” OR “animal model”/exp) AND (“disease” OR “disease”/exp OR “laboratory” OR “laboratory”/exp OR “experimental”))) AND (“lymphedema”/exp OR “lymphedema”) AND [2010–2020]/py AND “article”/it | 308 |

| Web of Science | ((TS = (“Disease Model” OR “Animal Model” OR (“Animal Model” AND (“Disease” OR “Laboratory” OR “Experimental”))) AND TS = (“Lymphedema” OR “Lymphedema” OR “Lymphatic Injury”))) AND DOCUMENT TYPES: (Article) Indexes = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan = 2010–2020 |

35 |

| Scopus | ALL((“Disease Model” OR “Animal Model” OR (“Animal Model” AND (“Disease” OR “Laboratory” OR “Experimental”))) AND (“Lymphedema” OR “Lymphedema” OR “Lymphatic Injury”)) AND DOCTYPE(ar) AND PUBYEAR >2009 AND PUBYEAR <2021 | 866 |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND FUNDING SOURCES

We would like to thank Jennifer Dinalo, PhD, for her expertise in developing the literature search terms.

A.K.W. acknowledges support from National Institutes of Health UL1TR001855, KL2TR001854, TR03HL154300, K08HL132110, R03 HL154300, and R01 HL157626 as well as Plastic Surgery Foundation, and the American Society for Reconstructive Microsurgery (ASRM) and Lymphatic Education and Research Network's (LE&RN) Combined Pilot Lymphedema Research Grant.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: A.K.W., J.F.H., and R.P.Y.; methodology: A.K.W., J.F.H., and R.P.Y.; project administration and supervision: A.K.W.; literature search and review: A.K.W., J.F.H., and R.P.Y.; data extraction: J.F.H., R.P.Y., E.W.S., and J.W.; formal analysis: J.F.H., R.P.Y., E.W.S., and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation: J.F.H., R.P.Y., E.W.S., and J.W.; and writing—review and editing: A.K.W., J.F.H., R.P.Y., E.W.S., and J.W.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE AND GHOSTWRITING

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests. The content of this article was expressly written by these authors. No ghostwriters were used in the production of this article.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jerry F. Hsu, BS, is a second-year medical student at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. He is completing a research fellowship at the University of Southern California's (USC) Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in Dr. Wong's laboratory and is interested in a career in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Roy P. Yu, BS, is a first-year medical student at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and conducts research in Dr. Wong's laboratory. Eloise W. Stanton, BA, is a first-year medical student at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and conducts research in Dr. Wong's laboratory. Jin Wang, MD, is a plastic surgeon and a research fellow at City of Hope in Dr. Wong's laboratory. Alex K. Wong, MD, is Professor and Chief of Plastic Surgery at City of Hope National Medical Center. In addition to his clinical practice and involvement in medical education, he directs a research laboratory focused on studying lymphedema, adult-derived stem cells, and novel biologics for wound healing, molecular pathogenesis of silicone breast implant capsular contracture, and microvascular flap physiology.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hayes SC, Janda M, Cornish B, Battistutta D, Newman B. Lymphedema after breast cancer: incidence, risk factors, and effect on upper body function. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3536–3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McLaughlin SA, DeSnyder SM, Klimberg S, et al. Considerations for clinicians in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of breast cancer-related lymphedema, recommendations from an expert panel: part 2: preventive and therapeutic options. Ann Surg Oncol 2017;24:2827–2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernas M, Thiadens SRJ, Smoot B, Armer JM, Stewart P, Granzow J. Lymphedema following cancer therapy: overview and options. Clin Exp Metastasis 2018;35:547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McNeely ML, Peddle CJ, Yurick JL, Dayes IS, MacKey JR. Conservative and dietary interventions for cancer-related lymphedema. Cancer 2011;117:1136–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang DW. Lymphaticovenular bypass for lymphedema management in breast cancer patients: a prospective study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126:752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grada AA, Phillips TJ. Lymphedema: pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77:1009–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aspelund A, Robciuc MR, Karaman S, Makinen T, Alitalo K. Lymphatic system in cardiovascular medicine. Circ Res 2016;118:515–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lawenda BD, Mondry TE, Johnstone PAS. Lymphedema: a primer on the identification and management of a chronic condition in oncologic treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:8–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59:324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Executive Committee of the International Society of Lymphology. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2020 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 2020;53:3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, et al. Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med 2009;361:664–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shaw C, Mortimer P, Judd PA. A randomized controlled trial of weight reduction as a treatment for breast cancer-related lymphedema. Cancer 2007;110:1868–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shih YC, Xu Y, Cormier JN, et al. Incidence, treatment costs, and complications of lymphedema after breast cancer among women of working age: a 2-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2007–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frueh FS, Gousopoulos E, Rezaeian F, Menger MD, Lindenblatt N, Giovanoli P. Animal models in surgical lymphedema research—a systematic review. J Surg Res 2016;200:208–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hadrian R, Palmes D. Animal models of secondary lymphedema: new approaches in the search for therapeutic options. Lymphat Res Biol 2017;15:2–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hadamitzky C, Pabst R. Acquired lymphedema: an urgent need for adequate animal models. Cancer Res 2008;68:343–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rutkowski JM, Moya M, Johannes J, Goldman J, Swartz MA. Secondary lymphedema in the mouse tail: lymphatic hyperplasia, VEGF-C upregulation, and the protective role of MMP-9. Microvasc Res 2006;72:161–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frueh FS, Körbel C, Gassert L, et al. High-resolution 3D volumetry versus conventional measuring techniques for the assessment of experimental lymphedema in the mouse hindlimb. Sci Rep 2016;6:34673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. García Nores GD, Ly CL, Savetsky IL, et al. Regulatory T cells mediate local immunosuppression in lymphedema. J Invest Dermatol 2018;138:325–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gardenier JC, Kataru RP, Hespe GE, et al. Topical tacrolimus for the treatment of secondary lymphedema. Nat Commun 2017;8:14345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jang DH, Song DH, Chang EJ, Jeon JY. Anti-inflammatory and lymphangiogenetic effects of low-level laser therapy on lymphedema in an experimental mouse tail model. Lasers Med Sci 2016;31:289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gousopoulos E, Karaman S, Proulx ST, Leu K, Buschle D, Detmar M. High-fat diet in the absence of obesity does not aggravate surgically induced lymphoedema in mice. Eur Surg Res 2017;58:180–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morfoisse F, Tatin F, Chaput B, et al. Lymphatic vasculature requires estrogen receptor-α signaling to protect from lymphedema. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2018;38:1346–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kwon S, Price RE. Characterization of internodal collecting lymphatic vessel function after surgical removal of an axillary lymph node in mice. Biomed Opt Express 2016;7:1100–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mendez U, Brown EM, Ongstad EL, Slis JR, Goldman J. Functional recovery of fluid drainage precedes lymphangiogenesis in acute murine foreleg lymphedema. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012;302:H2250–H2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hwang JH, Kim IG, Lee JY, et al. Therapeutic lymphangiogenesis using stem cell and VEGF-C hydrogel. Biomaterials 2011;32:4415–4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jun H, Lee JY, Kim JH, et al. Modified mouse models of chronic secondary lymphedema: tail and hind limb models. Ann Vasc Surg 2017;43:288–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim IG, Lee JY, Lee DS, Kwon JY, Hwang JH. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy combined with vascular endothelial growth factor-C hydrogel for lymphangiogenesis. J Vasc Res 2013;50:124–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee CY, Kang JY, Lim S, Ham O, Chang W, Jang DH. Hypoxic conditioned medium from mesenchymal stem cells promotes lymphangiogenesis by regulation of mitochondrial-related proteins. Stem Cell Res Ther 2016;7:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ogino R, Hayashida K, Yamakawa S, Morita E. Adipose-derived stem cells promote intussusceptive lymphangiogenesis by restricting dermal fibrosis in irradiated tissue of mice. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nikitenko LL, Shimosawa T, Henderson S, et al. Adrenomedullin haploinsufficiency predisposes to secondary lymphedema. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:1768–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bramos A, Perrault D, Yang S, Jung E, Hong YK, Wong AK. Prevention of postsurgical lymphedema by 9-cis retinoic acid. Ann Surg 2016;264:353–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jorgensen MG, Toyserkani NM, Hansen CR, et al. Quantification of chronic lymphedema in a revised mouse model. Ann Plast Surg 2018;81:594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wiinholt A, Jorgensen MG, Bucan A, Dalaei F, Sorensen JA. A revised method for inducing secondary lymphedema in the hindlimb of mice. J Vis Exp 2019; DOI: 10.3791/60578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Komatsu E, Nakajima Y, Mukai K, et al. Lymph drainage during wound healing in a hindlimb lymphedema mouse model. Lymphat Res Biol 2017;15:32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kwon S, Agollah GD, Wu G, Sevick-Muraca EM. Spatio-temporal changes of lymphatic contractility and drainage patterns following lymphadenectomy in mice. PLoS One 2014;9:e106034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chang TC, Uen YH, Chou CH, Sheu JR, Chou DS. The role of cyclooxygenase-derived oxidative stress in surgically induced lymphedema in a mouse tail model. Pharm Biol 2013;51:573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Avraham T, Zampell JC, Yan A, et al. Th2 differentiation is necessary for soft tissue fibrosis and lymphatic dysfunction resulting from lymphedema. FASEB J 2013;27:1114–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ghanta S, Cuzzone DA, Torrisi JS, et al. Regulation of inflammation and fibrosis by macrophages in lymphedema. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2015;308:H1065–H1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zampell JC, Aschen S, Weitman ES, et al. Regulation of adipogenesis by lymphatic fluid stasis: part I. Adipogenesis, fibrosis, and inflammation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012;129:825–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gousopoulos E, Proulx ST, Scholl J, Uecker M, Detmar M. Prominent lymphatic vessel hyperplasia with progressive dysfunction and distinct immune cell infiltration in lymphedema. Am J Pathol 2016;186:2193–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]