Abstract

Accumulation of trehalose is widely believed to be a critical determinant in improving the stress tolerance of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is commonly used in commercial bread dough. To retain the accumulation of trehalose in yeast cells, we constructed, for the first time, diploid homozygous neutral trehalase mutants (Δnth1), acid trehalase mutants (Δath1), and double mutants (Δnth1 ath1) by using commercial baker’s yeast strains as the parent strains and the gene disruption method. During fermentation in a liquid fermentation medium, degradation of intracellular trehalose was inhibited with all of the trehalase mutants. The gassing power of frozen doughs made with these mutants was greater than the gassing power of doughs made with the parent strains. The Δnth1 and Δath1 strains also exhibited higher levels of tolerance of dry conditions than the parent strains exhibited; however, the Δnth1 ath1 strain exhibited lower tolerance of dry conditions than the parent strain exhibited. The improved freeze tolerance exhibited by all of the trehalase mutants may make these strains useful in frozen dough.

In the baking industry, frozen-dough technology has recently been accepted due to its advantages, which include supplying oven-fresh bakery products to consumers and improving labor conditions for bakers (15). Ordinary commercial baker’s yeast is generally susceptible to damage during frozen storage and does not retain sufficient leavening ability after frozen storage. Prefermented frozen doughs yield low-quality bread due to the poor gassing power of freeze-injured yeast. Several types of freeze-tolerant yeasts have been found in natural sources (10, 14). Although freeze-tolerant yeasts have also been obtained by conventional mutation procedures (20, 22, 32), bread baked with freeze-tolerant yeast strains obtained by conventional mutation procedures has less taste and flavor than bread baked with the parent strains. In this study our goal was to construct freeze-tolerant baker’s yeast strains from commercial strains by using DNA recombinant techniques without degrading the other beneficial properties of the yeasts (e.g., taste and flavor).

We focused on trehalose as a cryoprotectant for yeast cells. The reason for this is that in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae the disaccharide trehalose is thought to be a critical determinant of stress tolerance, including freezing dehydration, and heat shock tolerance, because its concentration increases under certain adverse environmental conditions (7, 9, 13, 29). The cellular levels of trehalose are controlled by a balance between the trehalose-synthesizing and trehalose-hydrolyzing enzymes (23). The bifunctional enzyme called trehalose-6-phosphate synthetase/trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase synthesizes trehalose in the cytosol by condensing glucose-6-phosphate and UDP-glucose (23). The following two enzymes are capable of hydrolyzing trehalose: a neutral cytosolic trehalase (designated Nth1p) and an acidic trehalase (designated Ath1p) (19). Both Nth1p and Ath1p have been purified from S. cerevisiae, and the corresponding genes have been cloned and sequenced (1, 8, 17). Maximum Nth1p activity occurs at pH 6.0 to 7.0, and this activity is regulated by the RAS/adenylate cyclase signal transduction pathway, which converts the inactive form to the phosphorylated, active form (19). Nth1p plays a role in protecting cells against heat shock (25). In contrast to cytosolic Nth1p, Ath1p is a vacuolar protein whose optimum pH is 4.5 (21); this protein is necessary for the phenotype of growth on trehalose (i.e., trehalose utilization) (26). Biswas and Ghosh reported that Ath1p is present in trehalase-sucrase aggregates (2). However, the regulatory pathway that controls Ath1p activity is not known.

In order to determine the effect of trehalase disruption during the baking process, we constructed trehalase-deficient diploid strains derived from commercial baker’s yeast strains. Because commercial strains differ from laboratory strains in many properties, such as trehalose content, stress tolerance, leavening ability, and flavor formation, commercial strains were used in this work. In fact, neither haploid nor diploid strains derived from laboratory strains can be used for baking tests due to their poor gassing powers. We found that trehalase-deficient mutants accumulate higher levels of trehalose than their parent strains accumulate under the culture conditions that are optimal for high trehalose contents and that trehalose accumulation correlates with high freeze tolerance in frozen-dough baking. We also found that it may be possible to use mutant yeast strains obtained by gene disruption for commercial applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, growth conditions, and mating.

The strains of baker’s yeast used in this study are listed in Table 1. Yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium contained (per liter) 10 g of yeast extract (Difco Laboratories), 20 g of peptone (Difco), and 20 g of glucose. YPD agar contained 2% Bacto Agar (Difco) in addition to the components mentioned above. Synthetic dextrose medium contained (per liter) 1.7 g of yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate (Difco), 5 g of ammonium sulfate, and 20 g of glucose. Liquid fermentation (LF) medium contained (per liter) 100 g of sucrose. For negative selection of ura3 mutants, we used 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) plates containing (per liter) 1 g of 5-FOA, 6.7 g of yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (Difco), 20 g of glucose, 120 mg of uracil, and 20 g of Bacto Agar (Difco). Cane molasses medium contained (per liter) 30 g of sugar (calculated as sucrose), 5.66 g of urea, and 0.62 g of NaH2PO4.

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Description |

|---|---|

| T7 | Prototroph (MATa NTH1 ATH1) |

| T18 | Prototroph (MATα NTH1 ATH1) |

| T19 | Prototroph (MATα NTH1 ATH1) |

| T21 | Prototroph (MATa NTH1 ATH1) |

| T7dN | MATa nth1::URA3 ATH1, derived from T7 |

| T18dN | MATα nth1::URA3 ATH1, derived from T18 |

| T19dN | MATα nth1::URA3 ATH1, derived from T19 |

| T21dN | MATa nth1::URA3 ATH1, derived from T21 |

| T7dA | MATa NTH1 ath1::URA3, derived from T7 |

| T18dA | MATα NTH1 ath1::URA3, derived from T18 |

| T19dA | MATα NTH1 ath1::URA3, derived from T19 |

| T21dA | MATa NTH1 ath1::URA3, derived from T21 |

| T7dNA | MATa nth1::URA3 ath1::URA3, derived from T7dN |

| T18dNA | MATα nth1::URA3 ath1::URA3, derived from T18dN |

| T19dNA | MATα nth1::URA3 ath1::URA3, derived from T19dN |

| T21dNA | MATa nth1::URA3 ath1::URA3, derived from T21dN |

| T118 | MATa/α NTH1/NTH1 ATH1/ATH1, obtained by mating T7 and T18 |

| T128 | MATa/α NTH1/NTH1 ATH1/ATH1, obtained by mating T19 and T21 |

| T154 | MATa/α nth1/nth1 ATH1/ATH1, obtained by mating T7dN and T18dN |

| T164 | MATa/α nth1/nth1 ATH1/ATH1, obtained by mating T19dN and T21dN |

| A318 | MATa/α NTH1/NTH1 ath1/ath1, obtained by mating T7dA and T18dA |

| A328 | MATa/α NTH1/NTH1 ath1/ath1, obtained by mating T19dA and T21dA |

| AT418 | MATa/α nth1/nth1 ath1/ath1, obtained by mating T7dNA and T18dNA |

| AT428 | MATa/α nth1/nth1 ath1/ath1, obtained by mating T19dNA and T21dNA |

The yeast cells used in the baking and freeze tolerance tests (see below) were grown in molasses medium by using a continuously fed batch culture (simulating industrial yeast production) in a 30-liter fermentation jar (Oriental Bioserves, Tokyo, Japan) at 30°C (27). Diploid strains were constructed by mating strains of opposite mating types in YPD medium. Overnight cultures of each haploid parent were mixed and incubated at 30°C for 4 h without shaking. The mixtures were diluted 50-fold with fresh YPD medium. After cultivation overnight at 30°C, the mating mixture was plated onto YPD agar. Diploid strains were selected on the basis of colony size. Diploid formation was confirmed by pulse-field gel electrophoresis by using the method of Chu et al. (6) and a model CHEF-DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

The parent and trehalase mutant strains used in this study have been deposited in the Genetic Resources Center, National Institute of Agrobiological Resources, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) Culture Collection (Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan). The MAFF reference numbers are as follows: MAFF 113256 for T118, MAFF 113257 for T128, MAFF 113271 for A318, and MAFF 113272 for AT418.

Plasmid construction and disruption of trehalase genes.

We constructed the trehalase-deficient strains by using one-step gene disruption, which involved double recombination events at the homologous site (28). Transformation was carried out by using the LiCl methods described by Schiestl and Gietz (31). A fragment used for the ATH1 disruption procedure was constructed as follows. The ATH1 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified by PCR from strain T7 chromosomal DNA by using primers designed on the basis of the ATH1 sequences described by Destruelle et al. (8). The sequence of primer 1 was 5′-CATCCACTGGGAGTGGTTTC-3′, and the sequence of primer 2 was 5′-CGAGATGATTGCCAATGTCT-3′. The PCR product was then cloned into pGEM-T (Promega), which yielded pCI1. Next, pCI1 was digested with HindIII with only one site of the ATH1 ORF in the plasmid. The URA3 gene isolated as a HindIII fragment from YEp24 was inserted into the HindIII site of pCI1, which yielded pCY1. pCY1 was linearized with PvuII prior to transformation. A fragment used for the NTH1 disruption procedure was constructed as follows. NTH1 was obtained from the CEN fragment of chromosome III included in YCp50 by using a gene eviction method (33). A KpnI-EcoRI 770-bp fragment of NTH1 was inserted into the KpnI-EcoRI site of pUC19, which yielded pNTH1-KE. The URA3 gene isolated as a HindIII fragment from YEp24 prior to blunting with a Klenow fragment was ligated to pNTH1-KE, which had been blunted with a Klenow fragment after it was digested with XhoI. The resulting plasmid, pNTHd1, was linearized with EcoRI and KpnI prior to transformation into the parent strain.

DNA isolation, Southern blot analysis, and molecular biology methods.

Yeast DNA was isolated essentially as described by Hereford et al. (12). Southern hybridization was carried out by using a Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham) and an ECL direct nucleic acid labeling and detection system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Standard molecular biology techniques were adapted as described by Sambrook et al. (30).

Assays for trehalose, protein, and trehalase activity.

Yeast cells were collected by centrifugation (1,000 × g) for 10 min and were washed three times with cold (4°C) distilled water. After 0.5 M trichloroacetic acid was used to extract the trehalose from the yeast cells, the amount of trehalose was measured by the anthrone method (4). A crude lysate of yeast cells was prepared by disruption with glass beads. The protein concentration of the crude lysate was determined by the Bradford method (3). The activities of neutral trehalase and acid trehalase were assayed by using crude extracts of cells as described by Mittenbuhler and Holzer (21).

Dehydration of yeast cells.

First, yeast cells were dehydrated to 68% relative humidity, and then a sorbitan monostearate emulsion was added at a proportion equivalent to 1.5% of the yeast solids content (11). The preparation obtained was extruded through a screen having a mesh size of 0.4 mm. The yeast was dried to a solids content of 95% by fluidization in a current of hot, dry air. Dehydration was carried out within 50 min; during this process the temperature of the yeast did not exceed 38°C.

Amount of gas produced in dough.

To determine leavening ability, the volume (in milliliters) of carbon dioxide gas produced after incubation for 2 h at 30°C was measured by using a Formograph AF-1000 apparatus (Atto Co., Tokyo, Japan). The volume was normalized to standard conditions (30°C, 101.3 kPa). The low-sugar dough formula contained 100 parts of bread-making flour (13.5% moisture basis), 6 parts of sugar, 2 parts of NaCl, 2 parts of yeast (67% moisture basis), and 65 parts of water. The ingredients were mixed for 2 min with a Swanson type mixer (Eberhardt-Denver Co., Denver, Colo.), and the resulting dough was divided into 40-g pieces, which were kept in polyethylene bags. The dough pieces were fermented for 60 min at 30°C before they were frozen at −20°C. The frozen dough was thawed for 30 min at 30°C before gas production was measured.

Baking.

White bread and sweet bread were prepared by the straight dough method. The formula for the white bread was as follows: 100 parts of bread-making flour (13.5% moisture basis), 2 parts of NaCl, 2 parts of yeast cells (67% moisture basis), 5 parts of shortening, and 66 parts of water. The ingredients were mixed for 2 min with a Swanson type pin mixer (Eberhardt-Denver Co.). After fermentation for 115 min at 30°C, the dough was punched twice and molded (relative humidity, 75%). The dough was divided, and a sample which was used for a freeze tolerance test was stored for 1 week at −20°C. The frozen dough was thawed for 30 min at 30°C before final proofing. After the dough was proofed for 55 min at 38°C, it was baked for 25 min at 200°C. The formula for the sweet bread was as follows: 70 parts of bread-making flour (13.5% moisture basis), 30 parts of semihard flour (13.5% moisture basis), 25 parts of sucrose, 0.7 parts of NaCl, 4 parts of yeast cells (67% moisture basis), 6 parts of shortening, 2 parts of nonfat dry milk powder, and 54 parts of water. After the dough was proofed for 45 min at 38°C, it was baked for 20 min at 200°C. The loaf volume (in milliliters) and weight (in grams) were measured within 1 h after baking and the specific volume (in milliliters per gram of bread) was calculated. Both the external characteristics and the internal characteristics of the bread were evaluated by using the method of the Japan Yeast Industry Association.

RESULTS

Construction of trehalase mutants derived from commercial baker’s yeast strains by gene disruption.

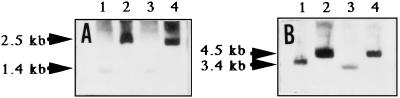

Table 1 shows the strains used in this study. The haploid strains which we used for trehalase gene disruption and to form diploid strains were selected from commercial baker’s yeast strains based on high levels of transformation efficiency and good fermentation properties. The diploid strains that were obtained by mating the haploid strains had gassing powers equivalent to the gassing powers of commercial baker’s yeast strains (data not shown). Since the parent strains were prototrophs, the spontaneous ura3 mutants were obtained by 5-FOA negative selection (5). The ura3 mutants derived from four haploid strains (two mating type a strains and two mating type α strains) were used for transformation. The Δnth1 mutants and the Δath1 mutants were obtained by transformation of the haploid strains with fragments containing NTH1 or ATH1. Southern blot analysis confirmed that gene disruption occurred. Genomic DNAs isolated from transformants and parent strains were digested with EcoRI and were hybridized by using either an NTH1 probe or an ATH1 probe (data not shown). The Δnth1 ath1 double mutants were constructed by transformation of Δnth1 ura3 mutants, which were obtained by spontaneous 5-FOA reselection from Δnth1 strains by using the fragment for ATH1 disruption. The Southern blot analysis confirmed that the double mutation was present (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Southern blot analysis of Δnth1 ath1 double mutant. Total yeast genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI, electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with a 1.4-kb EcoRI-KpnI fragment containing the NTH1 ORF (A) and a 1.1-kb fragment containing the ATH1 ORF prepared by PCR in which primer 1 and primer 2 (B) were used as probes. Lane 1, T118; lane 2, AT418; lane 3, T128; lane 4, AT428.

We constructed two series of diploid trehalase mutants that had different genetic backgrounds; one series had a genetic background of T7 and T18, and the other had a genetic background of T19 and T21 (Table 1). Neutral and acidic trehalase activities were assayed in cell extracts obtained from parent strains T118 and T128, Δnth1 strains T154 and T164, Δath1 strains A318 and A328, and Δnth1 ath1 strains AT418 and AT428. In the T118 background, neither the Δath1 strain nor the Δnth1 ath1 strain exhibited any acidic trehalase activity throughout the entire growth process, and the neutral trehalase activities of the Δnth1 and Δnth1 ath1 strains were less than 20% of the activities of the parent strains in the logarithmic phase (Table 2). In contrast, the neutral trehalase activity was decreased slightly by the trehalase disruption in T128 (Table 2). In both genetic backgrounds, neither the Δath1 strains nor the Δnth1 ath1 strains were able to grow on a medium that contained trehalose as the sole carbon source. In rich media, such as YPD medium or molasses medium, the cell densities of all of the trehalase mutants increased and approached the cell densities of the parent strains (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Neutral and acid trehalase activities of trehalase mutants

| Strain | Neutral trehalase activity (mU/mg of protein)a | Acid trehalase activity (mU/mg of protein)b |

|---|---|---|

| T118 | 96.0 | 13.5 |

| T154 | 18.0 | 13.5 |

| A318 | 62.0 | 1.0 |

| AT418 | 19.0 | 3.2 |

| T128 | 16.5 | 10.5 |

| T164 | 10.5 | 10.0 |

| A328 | 13.0 | 1.0 |

| AT428 | 10.0 | 1.0 |

Cells were grown in molasses medium and were harvested at the mid-logarithmic phase. One unit of neutral trehalase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the hydrolysis of 1 μmol of trehalose/min at 30°C at pH 7.0.

Cells were grown in molasses medium and were harvested at the late stationary phase. One unit of acid trehalase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the hydrolysis of 1 μmol of trehalose/min at 30°C at pH 4.5.

Intracellular accumulation and degradation of trehalose in the trehalase mutants.

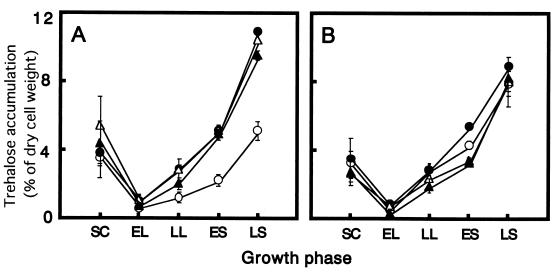

In this study, cells of trehalase mutants and parent strains were grown in continuously fed batch cultures in order to obtain a high trehalose content, which simulated the industrial yeast production process. At various times during growth, samples were removed, and the intracellular trehalose levels were measured (see above). We tested two different genetic backgrounds, T118 and T128. In the T118 background, the Δnth1 (T154), Δath1 (A318), and Δnth1 ath1 (AT418) strains accumulated substantially more trehalose than parent strain T118 accumulated (Fig. 2A). At the end of the stationary phase, the amounts of trehalose accumulated by these mutants were about twice the amounts accumulated by the parent strains. Under the experimental conditions used, all of the mutant strains exhibited nearly identical trehalose accumulation characteristics. Contrary to expectations, the NTH1 ATH1 double disruption had no detectable synergistic effect on trehalose accumulation. In contrast, the amount of trehalose that accumulated was slightly increased by the trehalase disruption of T128, which accumulated more trehalose than T118 accumulated (Fig. 2B). To determine the effect of trehalase disruption on the baking of frozen dough, we used the T118 background mutant series as a model for an analysis of stress tolerance in dough.

FIG. 2.

Intracellular trehalose accumulation by trehalase mutants of T118 (A) and trehalase mutants of T128 (B). Samples were obtained at various growth phases, including the seed culture (SC), the early logarithmic phase (EL), the late logarithmic phase (LL), the early stationary phase (ES), and the late stationary phase (LS). (A) Symbols: ○, T118; ●, T154; ▵, A318; ▴, AT418. (B) Symbols: ○, T128; ●, T164; ▵, A328; ▴, AT428. The results are means ± standard deviations based on three independent experiments.

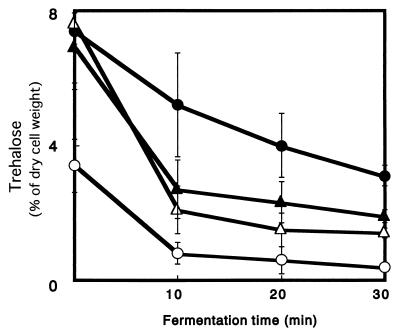

In general, during fermentation the amount of trehalose in baker’s yeast decreased very rapidly. When trehalase mutants fermented in LF medium for 10 to 30 min at 30°C, the amounts of trehalose that accumulated in the cells differed from the amounts that accumulated in the parent strains (Fig. 3). In parent strain T118, the trehalose level was less than 1% after 10 min. In the Δnth1, Δath1, and Δnth1 ath1 strains, the trehalose levels also decreased initially but only to between 1.5 to 4%, and then they remained relatively constant. In the Δnth1 ath1 strain, no trehalase activity was expected, but the trehalose level decreased. This may have been due to an NTH1 homologue, NTH2.

FIG. 3.

Changes in intracellular trehalose content during fermentation in LF medium at 30°C. Symbols: ○, T118; ●, T154; ▵, A318; ▴, AT418. The results are means ± standard deviations based on three independent experiments.

Stress tolerance of the trehalase mutants.

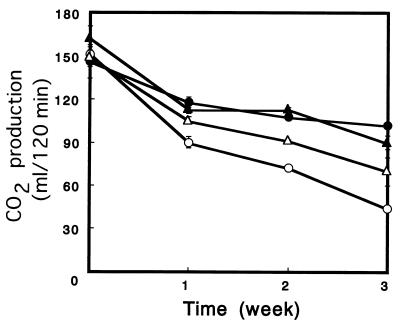

Intracellular accumulation of trehalose is believed to increase a yeast’s tolerance to freezing. We assessed this tolerance in white bread doughs at various frozen-storage times by measuring the rates of CO2 production in thawed doughs that contained trehalase mutants and parent strains (Fig. 4). All of the trehalase mutants retained more gassing power than the parent strains retained. Among the trehalase mutants, the Δnth1 strain had the highest freeze tolerance associated with a high intracellular trehalose level during fermentation and produced 100 ml of CO2 even after 3 weeks frozen storage.

FIG. 4.

Gassing power in frozen doughs stored for different periods of time at −20°C. The doughs were thawed, and then CO2 production at 30°C was measured for 2 h. Symbols: ○, T118; ●, T154; ▵, A318; ▴, AT418. The results are means ± standard deviations based on three independent experiments.

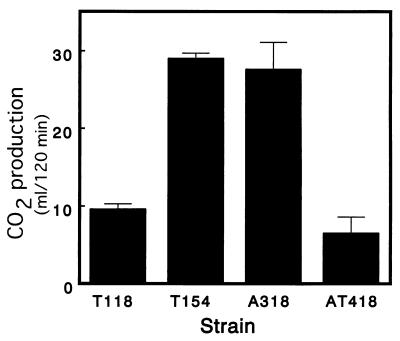

Like the protective role of trehalose during freezing, trehalose increases a yeast’s tolerance to dehydration. We therefore examined the effects of trehalase disruption on dehydration. Cells of trehalase mutants and parent strains were dehydrated to a relative humidity of 5%, which simulated the industrial instant dry yeast production process. Then, CO2 production after rehydration of the dried yeast was measured (Fig. 5). The gassing powers of the Δnth1 and Δath1 strains after rehydration were higher than the gassing powers of the parent strains. The Δnth1 ath1 strain exhibited remarkably low dry tolerance with its gassing power after rehydration; its gassing power was lower than that of the parent strain. There was no significant correlation between residual trehalose levels and dry tolerance. These results imply that trehalase activity is necessary for growth after rehydration in order to obtain sufficient energy.

FIG. 5.

Gassing power after dehydration to a relative humidity of 5% and rehydration. CO2 production by each yeast in LF medium at 30°C was measured for 2 h. The results are means ± standard deviations based on three independent experiments.

Baking with trehalase mutants obtained by gene disruption.

The baking properties of trehalase mutants were assessed by measuring the specific volumes of baked white bread and sweet bread. The specific volume represented the leavening property of baker’s yeast because it increased in proportion to the residential gassing power in the dough. White breads prepared with either the parent strains or the trehalase mutants had similar specific volumes, but the sweet breads prepared with the trehalase mutants had higher specific volumes than the sweet breads prepared with the parent strains (Table 3). In general, the fermentation ability of baker’s yeast is inhibited in doughs containing osmolytes, such as sugar and salt, at high concentrations. In fact, the specific volume of sweet bread prepared with a parent strain was significantly less than the specific volume of white bread prepared with the parent strain (Table 3). However, the specific volumes of sweet breads prepared with the trehalase mutants remained high. A high level of trehalose may protect the ability to ferment from high osmolarity.

TABLE 3.

Effect of trehalase disruption on fermentation ability in white bread dough and sweet bread dough and on frozen storage of white bread dough

| Strain | Sweet bread dough, nonfrozen

|

White bread dough, nonfrozen

|

White bread dough, frozen for 1 week

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loaf vol (ml)a | Specific vol (ml/g of bread) | Loaf vol (ml)a | Specific vol (ml/g of bread) | Loaf vol (ml)a | Specific vol (ml/g of bread) | |

| T118 | 715 | 4.3 | 715 | 4.9 | 505 | 3.4 |

| T154 | 780 | 4.7 | 750 | 5.0 | 590 | 4.1 |

| A318 | 780 | 4.7 | 765 | 5.2 | 555 | 3.7 |

| AT418 | 810 | 4.9 | 730 | 4.9 | 590 | 3.9 |

Volume of bread prepared with 100 g of flour and normalized to 4 g (wet weight) of yeast.

Bread quality tests showed that the crust color and internal characteristics (grain, crumb color, texture, aroma, and taste) of white bread prepared with trehalase mutants were similar to those of bread prepared with the parent strains (data not shown).

In the frozen-dough baking tests, white bread dough was stored for 1 week at −20°C, molded, proofed, and then baked for 30 min at 200°C. The specific volumes of the bread dough before and after storage were compared. The bread containing the trehalase mutants had a higher specific volume than the bread containing the parent strain. In particular, the Δnth1 strain produced the highest specific volume. These results suggest that trehalase disruption improves the freeze tolerance of baker’s yeast in dough.

DISCUSSION

In the baking industry, frozen-dough methods require yeast strains that have a high freeze tolerance and also retain desirable properties, such as flavor and strong gassing power. Although freeze-tolerant yeasts have been obtained by mutation (20, 22, 32), breads prepared with freeze-tolerant yeast strains obtained by conventional mutation procedures generally lack adequate taste and flavor. In this study, we examined the possibility that mutant yeast strains obtained by gene disruption could be used commercially.

The yeast strains available for frozen dough accumulate high levels of trehalose (9, 13, 29). Several studies have shown that there is a close correlation between trehalose levels and tolerance to freezing (16, 24). Trehalose is believed to be a stress-related metabolite and may have a stress protection function (18, 23). We attempted to regulate cellular levels of trehalose by avoiding hydrolyzing enzymes. We constructed, for the first time, diploid homozygous trehalase mutants derived from commercial baker’s yeast strains by molecular biological techniques. During fermentation, the trehalase mutations suppressed degradation of intracellular trehalose and significantly improved freeze tolerance (Fig. 3 and 4). Parent strain T118 had good leavening and flavor formation abilities, but it had a freeze tolerance that was slightly poorer than the freeze tolerance of commercial baker’s yeast available from the market for frozen-dough baking. Strain T154, which is an NTH1 disruptant derived from T118, was developed to have a freeze tolerance level similar to that of commercial frozen-dough baking yeast, as well as the other beneficial properties of T118. White bread dough containing T154 can be frozen for up to 2 weeks without a loss of gassing power. Our results suggest that the ath1 and nth1 mutations are effective for breeding of baker’s yeast. Kim et al. have reported that ATH1 disruption of laboratory strains is more effective for trehalose accumulation than NTH1 disruption and that the ATH1 NTH1 double disruption has a synergistic effect (16). In contrast, we did not observe either of these effects. One possible reason for this is that the effects of trehalase disruption on trehalose accumulation may depend on the genetic background of the strains themselves. For the trehalase mutants that we studied, the patterns of trehalose accumulation varied from strain to strain, depending on the parent used (Fig. 2). Our results show that the effect of trehalase disruption on trehalose accumulation was less for strains that have high-trehalose backgrounds.

Kim et al. have reported that ATH1 disruption results in tolerance to dehydration, as well as tolerance to freezing (16). In this study, the Δnth1 and Δath1 mutants exhibited significantly increased dry tolerance compared with the parent strain, but the Δnth1 ath1 strain exhibited significantly decreased dry tolerance. One possible explanation for why the double disruptant exhibited lower dry tolerance is that trehalase activity may be a requirement for rehydration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by grant-in-aid BMP 97-V-1-3-12 (Bio-Media Program) from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries.

REFERENCES

- 1.App H, Holzer H. Purification and characterization of neutral trehalase from the yeast ABYS1 mutant. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17583–17588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas N, Ghosh A K. Possible role of isoaspartyl methyltransferase towards regulation of acid trehalase activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1335:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(96)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brim M. Transketolase: clinical aspects. Methods Enzymol. 1966;9:506–514. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown P A, Szostak J W. Yeast vectors with negative selection. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:278–290. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu G, Vollrath D, Davis W R. Separation of large DNA molecules by contour-clamped homogenous electric fields. Science. 1986;234:1582–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.3538420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowe J H, Crowe L M, Chapman D. Preservation of membranes in anhydrobiotic organisms: the role of trehalose. Science. 1984;223:701–703. doi: 10.1126/science.223.4637.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Destruelle M, Holzer H, Klinonsky D J. Isolation and characterization of a novel yeast gene, ATH1, that is required for vacuolar acid trehalase activity. Yeast. 1995;11:1015–1025. doi: 10.1002/yea.320111103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dijck P V, Colavizza D, Smet P, Thevelin J M. Differential importance of trehalose in stress resistance in fermenting and nonfermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:109–115. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.109-115.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn Y-S, Kawai H. Isolation and characterization of freeze-tolerant yeasts from nature available for the frozen dough method. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:829–831. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hennette, A. L., R. P. Clement, B. D. Colavizza, and I. Berthlof. April 1998. U.S. patent 5,741,695.

- 12.Hereford L, Fahrner K, Woodford J J, Rosbash M, Kaback D B. Isolation of yeast histone genes H2A and H2B. Cell. 1979;18:1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90237-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hino A, Mihara K, Nakashima K, Takano H. Trehalose levels and survival ratio of freeze-tolerant versus freeze-sensitive yeasts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1386–1391. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1386-1391.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hino A, Takano H, Tanaka Y. New freeze-tolerant yeast for frozen dough preparations. Cereal Chem. 1987;64:269–275. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu K H, Hoseney R C, Sib P A. Frozen dough. I. Factors affecting stability of yeasted doughs. Cereal Chem. 1979;56:419–424. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Alizadeh P, Harding T, Hefner-Gravink A, Klionsky D J. Disruption of the yeast ATH1 gene confers better survival after dehydration, freezing, and ethanol shock: potential commercial applications. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1563–1569. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1563-1569.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kopp M, Muller H, Holzer H. Molecular analysis of the neutral trehalase gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4766–4774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krallish I, Jeppsson H, Rapoport A, Hahn-Hagerdal B. Effect of xylitol and trehalose on dry resistance of yeasts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:447–451. doi: 10.1007/s002530050954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Londesborough J, Varimo K. Characterization of two trehalases in baker’s yeast. Biochem J. 1984;219:511–518. doi: 10.1042/bj2190511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsunami K, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A, Nakamura I, Yajima N. Physical and biochemical properties of freeze-tolerant mutants of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Ferment Bioeng. 1990;70:275–276. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mittenbuhler K, Holzer H. Purification and characterization of acid trehalase from the yeast suc2 mutant. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8537–8543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa S, Ouchi K. Construction from a single parent of baker’s yeast strains with high freeze tolerance and fermentative activity in both lean and sweet doughs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3499–3502. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3499-3502.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nwaka S, Holzer H. Molecular biology of trehalose and the trehalases in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1998;58:197–237. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nwaka S, Kopp M, Burgert M, Deuchler I, Kienle I, Holzer H. Is thermotolerance of yeast dependent on trehalose accumulation? FEBS Lett. 1994;344:225–228. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nwaka S, Mechler B, Destruelle M, Holzer H. Phenotypic features of trehalase mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:286–290. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00105-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nwaka S, Mechler B, Holzer H. Deletion of the ATH1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae prevents growth on trehalose. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:235–238. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed G, Peppler H J. Baker’s yeast production. In: Reed G, editor. Yeast technology. Westport, Conn: AVI Publishing Company Inc.; 1973. pp. 53–102. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothstein R J. One-step gene disruption in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:202–210. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudolph A S, Crowe J H. Membrane stabilization during freezing: the role of two natural cryoprotectants, trehalose and proline. Cryobiology. 1985;22:367–377. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(85)90184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schiestl R H, Gietz R D. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet. 1989;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takagi H, Iwamoto F, Nakamori S. Isolation of freeze-tolerant laboratory strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae from proline-analogue-resistant mutants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:405–411. doi: 10.1007/s002530050948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winston F, Chumley F, Fink G R. Eviction and transplacement of mutant genes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:211–228. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]