Abstract

Background

The provision of commercialised gambling products and services has changed radically in recent decades. Gambling is now provided in many places by multi-national corporations, with important implications for public health and policymaking. The United Kingdom is one of the most liberalised gambling markets globally, however there are few empirical analyses of gambling policy from a public health perspective. This study aims to provide a critical analysis of a core element of UK gambling policy, the provision of industry-funded youth gambling education programmes.

Methods

Adopting a commercial determinants of health lens, a discourse theoretical analysis was conducted using the logics of critical explanation. The data comprised resources provided by three gambling industry-funded charities (GambleAware, GamCare and the Young Gamers and Gamblers Education Trust) and their partners.

Results

The resources present a gambling education discourse that serves to reproduce the ‘responsible gambling’ agenda, while problematising children and young people. While the resources appear to offer educational content and opportunities for debate, the dominant focus is on teaching about personal responsibility and on the normalisation of gambling and gaming and their industries, while constraining the concept of agency. The resources encourage young people to act as individuals to control their impulses, and to correct what are portrayed as faulty cognitions with the aim of becoming responsible consumers. Our findings demonstrate how the gambling education discourse aligns with wider industry interests, serving to deflect from the harmful nature of the products and services they market while shifting responsibility for harm onto children, youth and their families.

Conclusions

Despite being delivered in the name of public health, the resources construct a discourse favourable to corporate interests. Educators, parents, policymakers, and others need to be empowered to address the conflicts of interest that exist in the delivery of gambling industry-funded resources. The promotion of such industry-favoured interventions should not be allowed to undermine efforts to implement regulations to prevent gambling harms.

Keywords: Gambling industry, Discourse, Public health, Commercial determinants of health, Corporate social responsibility, Conflicts of interest

Highlights

-

•

Gambling harms are increasingly being recognised as a public health issue globally.

-

•

There have been few empirical analyses of gambling youth education programmes from a public health perspective.

-

•

Like elsewhere in the world, UK gambling education programmes are predominantly funded by the gambling industry.

-

•

Our findings demonstrate the ways in which the gambling education discourse aligns with industry interests.

-

•

Our study contributes to an under-researched aspect of the commercial determinants of health and applies a novel framework.

-

•

Greater scrutiny of youth gambling education programmes is needed.

1. Introduction

Gambling policy and the provision of commercialised gambling products and services have undergone radical transformation in recent decades (Sulkunen et al., 2021). Gambling is now provided in many contexts by multi-national corporations, with important implications for public health and policymaking (Cassidy, 2020). It is a highly profitable industry that continues to grow, facilitated by advancements in product design, marketing strategies, and web-based technologies (Banks, 2014; Sulkunen et al., 2021). These developments have had considerable harmful impacts on many individuals, families, and communities, with an important example being the United Kingdom (UK), where gambling policy changes have rendered it one of the most liberalised markets in the world (Cassidy, 2020; House of Lords Select Committee, 2020; Public Health England, 2021; Sulkunen et al., 2021). As in other jurisdictions, the concept of ‘responsible gambling’ has emerged as a central pillar in UK gambling policy (Cassidy, 2020), a highly contested policy topic (van Schalkwyk et al., 2021a).

The central idea behind responsible gambling is that gambling products, services, and practices are in and of themselves harmless and that harm arises from misuse or abnormal play. Following this line of thinking, it is then argued by industry that when provided with the ‘right’ information and tools that support self-restraint, monitoring and exclusion, people can, and should, learn to gamble responsibly and, by implication, avoid harm. Risk of harm therefore emerges from people not ‘playing responsibly’ as a consequence of their lack of control, irresponsibility, or faulty decision-making. The responsibility for harm therefore comes to lie with the consumer. This may be seen as a “dividing practice” (Bacchi & Goodwin, 2016), leading to the construction of the ‘responsible gambler’ as someone who is in control, gambling for the ‘right’ reasons (e.g. to have fun), as opposed to the ‘problem gambler’ or ‘gambling addict’ who is to be understood as deficient or faulty in some way. What constitutes responsible or safe gambling often remains ambiguously defined. The concept of responsible gambling and the trend toward pathologizing those harmed by gambling have been the focus of critical scholarship, which highlights the industry's role in promoting these conceptualisations and how they serve to problematise and stigmatise but not protect people (Cassidy, 2020; Hancock & Smith, 2017; Miller, Thomas, & Robinson, 2018; Miller & Thomas, 2018; Schüll, 2014). This approach is reminiscent of those adopted towards other potentially harmful commodities, such as food and alcohol, where it is for the individual consumer to use information and self-guiding tips, tools and guidelines to control and regulate their consumption, while living within pro-consumption minimally-regulated social contexts (Room, 2011). The role of the gambling industry, and less so the government, is therefore to provide (or fund) information and services that enable consumers to gamble in the ‘right’ way (Hancock & Smith, 2017). This policy approach places the majority of the burden of managing the risk and consequences of engaging with harmful products on individuals and deflects from the impacts of policy or product design, industry practices and power, the obligation of governments to protect citizens, and business' ethical and social responsibilities (Hancock & Smith, 2017). This conceptual and policy approach is shaped and enabled by, and in turn reproduces, wider neoliberal ideas, values, and policy regimes that are based on the primacy of deregulated markets, marketization and privatization, the conflation of citizenship with the right to consume, and individualised models of health and responsibility (Cassidy, 2020; Harvey, 2007; Schüll, 2014; Schneider, Schwarze, Bsumek, & Peeples, 2016).

However, there are few empirical analyses of UK gambling policy from a public health perspective, and there have been no independent analyses of youth gambling education initiatives, which represent a core element of this policy system and are predominantly funded by the industry and delivered by industry-funded charities. This is despite gambling education ostensibly representing a major policy response to addressing gambling harms. Indeed, teaching about the risks of gambling is now a statutory requirement for all state-funded schools in the UK (Department for Education, 2019). This provides an opportunity for the gambling industry to influence policy discourses and engage with policymakers and other actors through the funding, promotion and provision of gambling education programmes.

Adopting a commercial determinants of health lens, this analysis aims to provide a critical study of the provision of industry-funded youth gambling education programmes. The primary focus of this analysis is to explore whether and how the resources promote a particular account of gambling and gambling-related harms which is amenable to industry interests and their favoured policy regime. In this way, the study supports understanding how the resources may contribute to wider industry strategies, and consideration of the implications from a public health perspective. Using a discourse theoretical approach, we aim to describe, explain and critique: (1) the ways in which gambling, its risks and harms are constructed, (2) the assumptions, reasonings, and logics, on which these conceptualisations rest, (3) the identities, roles and responsibilities constructed within the texts, and (4) what and how pedagogical practices are employed. The study is therefore concerned with a much broader analysis rather than a narrow focus on whether the content is ‘factual’ or not. This approach supports understanding how these educational interventions serve to hinder or promote policy and social change that advances the public good.

2. Background

In Britain, different organisations, including charities and private companies, deliver youth gambling education programmes. Information provided by them is directed at children, young people, teachers, youth workers, other professionals, and parents. The main charities include GambleAware, GamCare, and the Young Gamers and Gambling Education Trust (YGAM) (GambleAware, 2020; GamCare; ; Young Gamers and Gamblers Education Trust. YGAM resources.; Young Gamers and Gamblers Education Trust. YGAM for parents), which are funded directly by the gambling industry and/or receive funding indirectly through GambleAware. Many gambling industry operators promote their funding of youth education initiatives in high-profile pledges and commitments, and in response to government consultations. In May of 2020, the Betting and Gaming Council (BGC), the self-proclaimed “industry standards body”, announced the:

launch of a £10 million independent gambling education initiative [that] will equip a generation of young people to better understand the risks associated with gambling and engage with gambling products and environments in an informed way. (Betting and Gaming Council, 2020)

The programme is delivered by GamCare and YGAM, with the funding being provided by BGC gambling industry members. As part of this programme, GamCare overseas the delivery of the BigDeal website (GamCare, 2020). The website provides materials directed at young people, parents, and professionals. YGAM provides a gambling and gaming education curriculum, and also launched an online Parent Hub in July 2020, providing materials about the harms of gambling, gaming and how to “establish a healthy online/offline balance” (Young Gamers and Gamblers Education Trust. YGAM for parents). The launch of the parent hub received endorsement by the Gambling Health Alliance (GHA), an alliance led by the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH, a charity that focuses on campaigning and education in relation to public health issues (Royal Society of Public Health)) and funded by GambleAware (Atkinson, 2020). In April 2021, YGAM announced the launch of “a new and improved” version of the Parent Hub website (Young Gamers and Gamblers Education Trust).

GambleAware also provides a range of youth education materials (GambleAware, 2021) in partnership with the PSHE Association (a charity and membership organisation that focuses on supporting the teaching of personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) education). GambleAware have also partnered with Fast Forward, a Scottish-based charity, to develop a “Gambling Education Hub, which is intended to promote gambling prevention and education in Scotland” (Fast Forward, 2020). In partnership with Parent Zone, GambleAware published a resource pack directed at “parents, carers and professionals, so they can support young people to stay in control of their finances and understand the risks of gambling”, and a second resource to support families to “learn about the gambling-like risks children may face when playing online games - and simple practical things parents and carers can do to keep gaming fun and safer”. (GambleAware, 2021; Parent Zone (a); Parent Zone (b)).

2.1. Concerns about gambling industry-funded charities

Concerns have been raised about these gambling industry-funded charities. For example, in 2016 concerns were raised by campaigners in the mainstream media regarding YGAM and the risk of conflicts of interest given the charity's reliance on industry funding and the involvement of gambling executives and industry lobbyists as ambassadors and trustees (Grierson, 2016). In 2021, the Charity Commission launched an investigation into YGAM upon receiving a complaint about its relationship with the BGC (Simmons, 2021). Within 7 days it closed the investigation, explaining that it was satisfied with the working relationship between YGAM and the BGC (Menmuir, 2021).After this episode, YGAM's Head of Delivery wrote a guest blog that was published on the BGC's website stating that by working together with teachers and youth workers “we are educating and safeguarding future generations” (Riding, 2021). The BGC make similar claims about the impacts of the youth prevention programme. However, no robust evidence of preventing harm or improving understanding is provided.

Concerns have been raised about GambleAware by academics, members of parliament, and others, particularly in relation to their role as leading fund-raiser and commissioner of gambling-related research, education, and treatment while being dependent on gambling industry-funding. In their interim report on online gambling harm, the Gambling Related Harm All Party Parliamentary Group stated “GambleAware collects funds from the industry to research and treat gambling addiction, but we are deeply concerned about the way they operate and an urgent review of their role and effectiveness is required” (Gambling Related Harm All Party Parliamentary Group, 2019). However the reasoning behind this statement was challenged by GambleAware (Etches, 2020). Some researchers problematise the arrangements that govern the relationships between the gambling industry, bodies like GambleAware, governments, regulators, and researchers and their institutions, drawing similarities with the use of third-party organisations by other harmful industries to distort the evidence-base and influence policymaking and public debate (Adams, 2011, 2016; Cassidy, 2020; Cowlishaw & Thomas, 2018; van Schalkwyk et al., 2021a, 2021b).

2.2. Problematising gambling industry-funded youth education programmes

Here we problematise the educational resources provided by gambling industry-funded organisations. The term problematise is used to signal the act of questioning and resurfacing the ‘taken-for-granted’, rendering it in need of explanation and critique (Howarth, 2010; Bacchi and Goodwin, 2016). Given limited evidence of the effectiveness of gambling education-based initiatives (Blank, Baxter, Woods, & Goyder, 2021), and their continued promotion by industry, those in receipt of industry-funding, and the Government as a means to protect children and young people from gambling harms, scholarly critique of their role within gambling policy and the implications for public health is overdue. Such materials are central to constructing and reproducing certain understandings of gambling, the gambling industry, the role and responsibility of different actors, and what constitute legitimate and possible forms of gambling policy. In this way, they constitute part of the gambling policy discourse whose institution is inherently political in nature and involves the exercise of power by virtue of exclusion of other possible ways of understanding and regulating gambling, and other social identities and practices (Howarth, 2000).

3. Theory and methods

The analysis was approached through a commercial determinants of health lens (Kickbusch, Allen, & Franz, 2016; Maani, McKee, Petticrew, & Galea, 2020; Mialon, 2020). This field of research is informed by an understanding that corporate practices and strategies can impact on public health and the determinants of health in diverse ways. This study draws on post-structuralist discourse theory, PSDT herein, and the logics of critical explanation (Glynos & Howarth, 2007; Hawkins, 2021; Howarth, Norval,& Stavrakakis, 2000; Howarth, Glynos & Griggs, 2016; Laclau & Mouffe, 1985), thereby serving to demonstrate how these provide a set of conceptual and analytical tools that can support conducting critical investigations of corporate political strategy and wider practices. The next two sections introduce PSDT and the logics of critical explanation respectively, followed by a description of the data included for analysis, and how the analysis was conducted.

3.1. Post-structuralist discourse theory

PSDT as developed by Laclau and Mouffe and later the work of others, offers a theory of discourse based on the primacy of politics and social antagonisms (Glynos & Howarth, 2007; Griggs & Howarth, 2019; Howarth, 2000, 2010; Howarth et al., 2016; Laclau & Mouffe, 1985). Central to this concept of discourse is “the idea that all objects and actions are inherently meaningful, and that their meaning is conferred by particular systems of significant difference” known as discourses (Howarth, 2000).

The emergence and formation of discourses is historical and contextual and they are contingent in that they represent a partial and contestable account of the social world (Howarth, 2000). The constitution of a discourse in a given social context involves the exercise of power, as it forecloses and conceals other possibilities, with implications for policymaking and people's lives and wellbeing (Howarth, 2000, 2010). Certain discourses (as established ‘ways of understanding, doing and being’) can become deeply embedded or ‘sedimented’ and take on the appearance of necessity or permanence (Hawkins, 2021). However, even these hegemonic discourses are inherently unstable and potentially vulnerable to moments of dislocation that expose the contingent nature of the prevailing social and political order and the possibility of understanding and doing things differently (Griggs & Howarth, 2019; Howarth, 2010). Forming and maintaining a sedimented discourse thus involves hegemonic practices that manage diverse grievances and demands, and that conceal the contingent nature of the social world (Howarth, 2000, 2010).

PSDT explores human identity and agency through the concepts of subject positions and political subjectivity. During times of social and political stability, individuals may identify with certain subject positions (e.g. those of mother, teacher, researcher, advocate etc.) whose meaning is determined in relation to the overall discourse. Conversely, at times of dislocation or policy contestation and debate, the contingent nature of the social world is revealed, and agents are called upon to exercise political subjectivity, that is, to identify with competing discourses and in this way to reproduce or challenge a given policy or system of policies, contributing to social or policy change (or stability) (Howarth, 2000).

Discourse-theoretically informed analyses aim to study how certain discourses emerge, achieve predominance, are maintained and contested at a given place in time: namely, to support explanation of social and policy change or stability (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002; Howarth, 2010). To that end it has seen the development of an analytical framework which seeks to operationalise the key tenets of PSDT for the analysis of concrete empirical cases.

3.2. The logics of critical explanation

To supplement the conceptual architecture established by PSDT, Glynos and Howarth developed an analytical framework referred to as the logics of critical explanation, establishing a methodology for conducting an explanatory critique of social regimes and policy change or stability (Glynos & Howarth, 2007; Laclau & Mouffe, 1985). They identify three types of logic – social, political, fantasmatic – as conceptual tools for the analysis of discourse (Remling, 2018a, 2018b). These logics seek to support “the discourse theorist to describe, explain and critique the emergence, maintenance and dissolution of structures of meaning, rules and practices in the social world” (Hawkins, 2021).

From a general perspective, Glynos and Howarth explain that “the logic of a practice comprises the rules or grammar of the practice, as well as the conditions which make the practice both possible and vulnerable” (emphasis in original) (Glynos & Howarth, 2007). Social logics enable the researcher to ‘come-to-grips’ with what is ‘going-on’ in a particular context (Howarth, 2010). They can be seen as representing the ‘the rules of the game’ or norms and values that guide social practices, the “internal structure of a discursive formation” (Hawkins, 2015). Social logics enable the researcher to describe and characterise discourses.

Political logics capture the practices through which a discourse emerges, and hegemony is established and maintained. Conversely, they are integral to the processes of contestation and challenge, whereby competing discursive projects are formed and seek to bring about a dislocation in the current hegemonic ordering of the social, catalysing its dissolution and a rearticulation of social relations. The logics of equivalence and difference, the formation or disarticulation of equivalential chains of identities and demands, developed by Laclau and Mouffe, are introduced into the framework as the key components of the political logics. The logics of equivalence and difference aid in describing and explaining the processes through which disparate demands or grievances are linked to form counter-discourses to contest existing hegemonic social orders or the ways in which these are ‘managed’ or dismantled to maintain the status quo (Glynos & Howarth, 2007; Hawkins, 2021; Howarth, 2010; Laclau & Mouffe, 1985).

The logic of equivalence describes the processes and practices that ‘bind’ or ‘unite’ disparate elements together to form a coherent discursive formation and that simplify the social space into two antagonistic poles, while the logic of difference involves the relaxing of these bonds to divide and complexify the social realm, to incorporate new grievances and demands thereby preventing the formation of, or dissolving, competing discourses (Howarth, 2010; Laclau & Mouffe, 1985). The logics of equivalence and difference should not be viewed as separate concepts but as interrelated and ongoing processes that involve articulation and reproduction or contestation and dissolution of a social order or policy. The emergence, reproduction or dissolution of a discourse therefore emanates from the dynamic and complex interplay between the logics of equivalence and difference. Political logics thus allow the researcher to explain how certain policies and practices emerge, are reproduced, contested, or transformed (Glynos & Howarth, 2007).

Fantasmatic logics are introduced into the analytical framework to aid in understanding why and how subjects are ‘gripped’ by certain practices, or policy discourses, despite the possibility of other systems of relations, practices, and policies. It is in this element of the framework that the influence of Lacanian theory, particularly the concept of fantasy, is most evident (Hawkins, 2021). It serves to capture the ways in which subjects acquire a sense of completeness and closure through identification with a given discourse – the pursuit of a fully formed and complete social identity and order – described by Glynos and Howarth as the “enjoyment of closure” (Glynos & Howarth, 2007).

Fantasmatic logics aid in resurfacing the ideological dimensions of a discourse that conceal the contingency and contestability of identities and social relations, while naturalising certain discourses as the necessary way of ordering social practices. In this way they capture how and why discourses resist change and public contestation (or the direction and speed of social change when it does arise) and how fantasy acts to conceal the radical contingency of social relations. Constructing fantasmatic narratives thus involves ‘smoothing’ over contradictory and often incompatible dimensions of a discourse that arise from engaging with the promise of complete social closure and control. That is, fantasmatic logics enable engaging with the possibility of realising the impossible. Concealment and ‘smoothing over’ may therefore rely on distributing certain features of narratives between different fora – public-official versus unofficial. Identification of contradictions or differential disclosure of certain features of the narratives employed in the construction and reproduction of a discourse can therefore serve as markers of fantasy (Glynos & Howarth, 2007).

Glynos and Howarth identify two dimensions of fantasy that come into play in discursive narratives: the ‘beatific’ and the ‘horrific’, which work hand-in-hand (Glynos & Howarth, 2007). Beatific narratives are built around a promise of a ‘fullness-to-come’, a harmonising and stabilising of the social world if a given hurdle is overcome or fantasy object obtained. Horrific narratives mirror the beatific dimension, in describing the horrors or losses that will unfold in the event the hurdle is not surmounted or the fantasy object is ‘taken’ by a discursively constructed ‘other’.

4. Applying the critical logics approach for empirical analysis

Application of the critical logics approach has been operationalised for the study of varied public discourses (Hawkins, 2021; Remling, 2018a, Remling, 2018b; Hawkins, 2015; Å m, 2013; Andersson and Ö hman, 2016; Clarke, 2012; Glynos, Klimecki, & Willmott, 2015; Glynos & Speed, 2012; Glynos, Speed, & West, 2014; Griggs, Anderssen, Howarth, & Liefferink, 2016; Quennerstedt, McCuaig, & Mårdh, 2021). The application of the critical logics approach to the analysis of educational materials directed at teachers, children and young people, and parents can aid in understanding ‘what are these texts doing?': how do they contribute to the maintenance or transformation of the hegemonic gambling discourse, including how gambling is conceptualised as a product or source of harm, the roles and responsibilities of different actors, and the role of regulation.

4.1. Data collection

Educational resources directed at children, young people, teachers/professionals, and parents were collected and collated over the period October 2020 to April 2021 (Table 1). Resources produced by GambleAware in partnership with the PSHE Association, Fast Forward and Parent Zone were downloaded from their respective websites and crosschecked with the relevant page on the GambleAware website (GambleAware, 2021) to ensure all relevant data had been obtained. YGAM educational resources were obtained via the YGAM website, and all online and PDF materials were downloaded from the 2020 and 2021 YGAM Parent Hub and the BigDeal websites (with webpages being downloaded and converted to PDFs for the purpose of analysis). The final dataset comprised a total of 282 texts. Further details are provided in the supplementary materials.

Table 1.

Summary of the data identified, collected, and analysed.

| Programme/resource | Lead organisations | Intended audience | Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Youth education programme | YGAM | Teachers and professionals who work with young people | Workshop and teaching resources with lesson plans, including lesson-specific materials, factsheets, and supporting PowerPoint presentations on certain topics eg. why people gamble/game, probability and luck, the gambling or gaming industry, money and debt, risks of gaming and gambling, addiction, and mental health. Materials for Key Stage 2 through to Key Stage 5, and ages 7–25 years. |

| Parents Hub | YGAM | Parents | Website, films, and downloadable PDF documents: two main sections covering gaming and gambling. Materials related to: primary-aged children, secondary ages 11–14 years, or secondary ages 15–18 years. |

| Youth education programme | GambleAware and PSHE | Teachers and students | Teaching handbooks with lesson plans and resources (exploring risk in relation to gambling, KS2 lesson pack, and promoting resilience to gambling, KS4 lesson pack), and general information on how to address gambling through PSHE education. Materials for Key stage 2 (ages 7–11) and Key stage 4 (ages 14–16.) |

| Youth education programme | GambleAware and Fast Forward | Teachers and other professionals | Gambling education toolkit with general background information and lesson plans and resources on 6 topics: What is gambling, Why is gambling an issue, How does gambling work?, How can gambling be risk?, What is gambling harm? How to reduce the risk of harm? Toolkit states that “session examples are designed to be used primarily with S3 to S6 pupils/14–17 years old, in school and youth work settings, although they may be adapted to be suitable also in other contexts”. |

| Youth education programme | GambleAware and Parent Zone | Parents/carers/families, and professionals who work with young people | Two resources packs: Gaming or gambling (FAQ, quiz, lesson plane, glossary, top tips related to the topic or gambling or gaming), and Know the stakes - resources for parents (FAQ, glossary, top tips) & resources for professionals (FAQ, glossary, top tips, guide). |

| BigDeal website | GamCare | Youth, Parents and professionals | Information sheets, videos, quizzes, and blogs, youth facing section and a section for professionals and parents. |

It was discovered that all the programmes address both topics of gambling and gaming (the latter involving the use of a gaming console often with multiplayer web-based features). Gaming-related materials were therefore also included in the analysis, which aligns with the growing recognition of the interconnectedness of the two industries (Banks, 2014; Wardle, 2021). Throughout the analysis the term ‘gambling education discourse’ will be used to refer to the discourse analysed through the corpus of texts, recognising that this encompasses both gambling and gaming.

4.2. Analysis

The analysis proceeded through a sequence of stages. The initial stage involved high-level reading of the entire dataset, followed by a second closer reading to build in-depth familiarity with the content of the texts. The texts were then read a third time to identify and record emerging key themes and associated textual elements. The data was coded systematically using a hybrid approach involving both inductive and deductive coding (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Themes or ‘codes’ were conceptualised as concepts or topics that were identified as distinct entities within and across the resources. This process was iterative, involving constant comparison and refinement of codes and associated textual elements as the entire corpus was coded and a comprehensive initial code book was developed.

At this stage a second researcher (MP) coded a representative sample of the dataset. Emergent themes were then openly discussed to reach consensus and develop a final coding framework. This was then applied to the entire dataset on a further close reading of the texts, allowing for the emergence of additional themes. The coded data were then analysed to identify the social, political and fantasmatic logics. During this process, coded textual elements were structured in relation to the logics, meaning the data were coded as being relevant to the identification of the social, political and/or fantasmatic logics. Coded data could be assigned to more than one logics-category. This structured data was then used to conduct an in-depth critical analysis involving description, explanation, and articulation, ‘moving’ back-and-forth across the structured data and intermittently returning to the theory and the literature on gambling and corporate strategy (Howarth et al., 2016). This final stage, moving through identification to explanation and critique was supported by the concept of interdiscursivity (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002; Livesey, 2002). This aided the identification and linking together of the logics by contextualising the gambling education discourse, and revealing the discourses that were drawn on and the ways in which they were reproduced and transformed. In-depth coding and analysis of textual sources were supported using NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International).

5. Results

Detailed accounts of the social, political and fantasmatic logics of the gambling education discourse are presented in the results, followed by a discussion section synthesising the logics and placing the findings within the wider literature on gambling policy discourses and corporate political strategies. Exemplar quotes are presented and the intended audience of the text from which the quotes originated is indicated throughout the results. The quotes are referenced using a code generated by the authors to guide the reader to further details about the relevant document provided in the supplementary materials. More extensive and additional quotes associated with each of the logics are also provided in the supplementary materials.

5.1. The social logics of gambling education

The gambling education discourse, as represented by the documents analysed, is constructed by a number of social logics articulating the place of gambling and gaming in the wider social context and certain understandings of gambling and gaming harms, their origins, implications, and required interventions.

5.1.1. Constructing gambling and gaming

The meaning of gambling and gaming and their position within the discourse are captured by the logics of consumerism and commodification. Focusing on gambling specifically, gambling is constructed as a normal consumer product and leisure pursuit. Gambling products and the gambling industry are portrayed as normal and ubiquitous aspects of British society and the expansion of gambling's presence, its marketing, and the influence of the industry as an inevitable progression. The role and rise of gaming as a childhood leisure activity and as a commercial industry are similarly portrayed as normal and inevitable. The other side to this normalisation and commodification of gambling and gaming, as constructed in some of the documents, is the recognition that both are potentially harmful. This dual nature of gambling and gaming as normal leisure activities that are also associated with a risk of harm is presented as justification for why children, youth, parents, teachers, and other professionals need to be provided with information and skills-building resources. Education and information are presented as having a central role in addressing the risks of gambling and gaming harms. Furthermore, that gambling and gaming should be approached and learned about simultaneously is presented as a given. The school and home therefore become natural sites in which actions are to be taken to prevent these harms. As the 2021 YGAM Parent Hub explains to parents:

Whether it’s on the TV, on the radio, at the football stadium or popping up during video games, gambling ads and influences are everywhere (YGAM-PH-2021-Gbling-09).

Similarly, the 2020 YGAM Parent Hub explained “Gaming has become part of everyday life. Many young people participate in it on a daily basis” (YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSup11to14-Gming-03 & InfoSup15to18-Gming-09).

A PSHE Association/GambleAware resource directed at teachers of students in years 5/6 (key stage 2, KS2, ages 9–11 years) similarly echoed the increasing exposure of students to gambling opportunities and the need for skills to “navigate” this context:

It is important that even at a younger age, pupils build the skills to navigate a world (both offline and online) where gambling is prevalent and start to develop a nuanced understanding of risky gambling behaviours and the impact of problem gambling on people’s health and wellbeing (GA-PSHE-KS2-03).

5.1.2. Articulating the harms and the centrality of risk, responsibility, and the moral consumer

Accompanying these understandings about the context from which harms are emerging, the logics of risk, resilience and healthism (the individualising and commodification of health (Crawford, 1980)) are critical in the construction of the gambling and gaming education discourse. Both gambling and gaming are to be understood as risky products when used in certain ways and for certain purposes. Society in general is portrayed as being full of risk and children and young people must be supported to develop the resilience and skills needed to navigate and minimise these risks as individuals. The notion of healthism is evident in the way health and well-being are described in individualistic terms and are to be achieved through individual actions, including being in control, and acting responsibly by making informed and rational decisions. In this way the logics of rationalisation, consumerism, self-restraint, and informed decision-making structure claims about what is needed for children and young people to protect themselves and to justify the suggested pedagogies in the resources. It is here that the moral tone of the materials becomes apparent. There are healthy and unhealthy gambling behaviours, with fun, responsible and safe gambling being achieved through gambling for the right reasons and spending the right amount of money. Parents are advised to have conversations with their children about gambling and gaming, and to help them think about the value of money and how best to spend their own money. Implicit assumptions and moral judgements are made about what is the “right” type of behaviour and decision, and what is seen as a healthy and moral use of money. For example, YGAM informs parents that:

If someone is playing for the fun of it then they will be happy. However it is good to help your child think about the overall picture so they can approach gambling activities in the right way (YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSup11to14-Gbling-09 & 15to18-Gbling-10).

Building on this idea that is it only certain behaviours, motives, and choices that lead to harm, the inherent risk associated with the products is minimised and the role of informed rational decision making elevated. The content of the materials then rests heavily on a logic of problematising children and young people. It is their tendency to act based on emotion, impulsivity, and their faulty cognitions and lack of knowledge that become the loci of the problem. This claim is made by presenting facts and information about how children's minds work, stages of brain development, known human cognitive biases, such as the gamblers fallacy, and psychology-based evidence about decision-making and delayed gratification. For example, the 2020 YGAM Parent Hub explained to parents that:

Remember young people aren’t prepared to balance emotion and logic to make healthy choices The rational side of their brain is still not fully developed, they lead with their emotional side of the brain which means their arguments may not seem rational (emphasis in original, YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSup15to18-Gming-07).

The PSHE Association/GambleAware key stage 4 (KS4, ages 14–16 years) teaching resource encourages teachers to introduce their students to the Marshmallow Test as a means through which to explore the concepts of “temptation, impulsive behaviour and delayed gratification” which is then promoted as a way of addressing gambling harms. Strategies adopted by children to delay the consumption of a marshmallow are presented by the teaching resource as being extrapolatable to the aims of gambling education. In this way, the discourse articulates the issue of preventing gambling harms with the use of individual-level coping strategies to control impulsivity and delay the gratification obtained through consumption. For example, after showing them a demonstration video of the Marshmallow Test and presenting the findings of the original and later studies, the teacher is then instructed to:

Ask students how this might apply to gambling … Emphasise that resisting impulsivity is a skill/attribute which can be learned and that we can avoid situations which require the need for us to exercise this skill/attribute in the first place. With this in mind, we will look at influences which can make it difficult to resist impulsive and/or unhealthy behaviours (GA-PSHE-KS4-01).

While the harms and risks associated with gambling and gaming are acknowledged, the dominant message is that these risks can be known, measured, monitored, and avoided through the provision of educational activities, tools, tips, and facts, the majority of which resemble responsible gambling messaging and tools promoted by the gambling industry and the bodies they fund. By receiving knowledge and skilled-based lessons and by ‘staying in control’, ‘making responsible decisions’ and adopting the ‘right behaviours’, harms can be prevented or minimised. Central to this assertion are the concepts of risk assessment, self-monitoring, the use of family contracts, and blocking tools. All of these are promoted as ways to identify and obtain balanced and healthy lifestyles. The PSHE Association/GambleAware KS4 teaching resource advises teachers that:

Students should consider two alternatives: an ‘in the moment’ response, not based on all the evidence; and an alternative response, with more accurate beliefs. This is to help young people to see that effective risk assessment requires a more neutral, fact-based approach rather than an emotional one (GA-PSHE-KS4-01).

The YGAM, GamCare, PSHE Association/GambleAware, Fast Forward, and Parent Zone teaching materials all centre around these logics. Much of the same advice, tools, and tips are interchangeably applied to gambling and gaming. However, the discourse is ambiguous as to what constitutes too much gambling or gaming, which products are safe, and what amount of use or exposure is healthy and safe – this is for individual children and families to identify and adhere to.

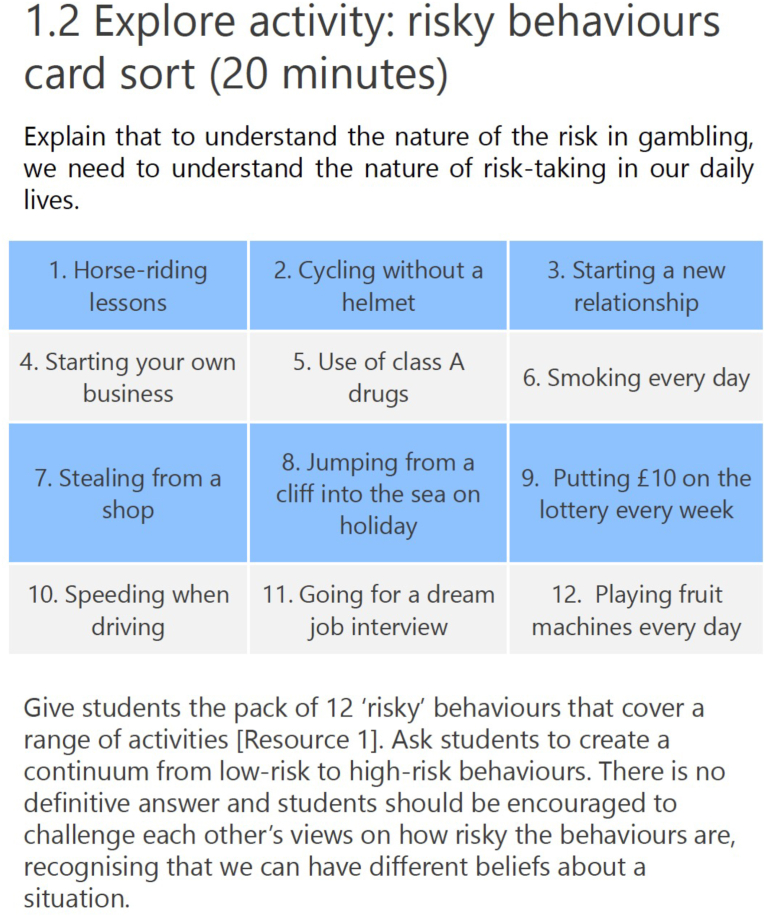

All the programmes provide lessons in which students are taught about risk. For example, students are presented with situations or scenarios (such as gambling, drinking alcohol, taking drugs, cycling, going for a job interview, entering a new relationship) and are asked to identity the risks and influences on the behaviour of the depicted characters, sometimes being asked to rank the behaviours from least to most risky (Fig. 1, see also Fig. 3 in political logics). The key logic is that by calculating, assessing, and managing risk, individuals can be safe, in control and enjoy gambling. For example, a YGAM lesson directed at year 8 students (ages 12–13 years), titled The House Edge, intends for students to be able to “identify gambling related harms” which is conflated within the lesson with knowing the probabilities of certain gambling outcomes. Gambling harms are not explicitly presented to the students, despite it being stated in the accompanying teachers' resource that it can be taught as a stand-alone lesson or as part of an extended 6-lesson series (YGAM-Sch-Y8-SOW).

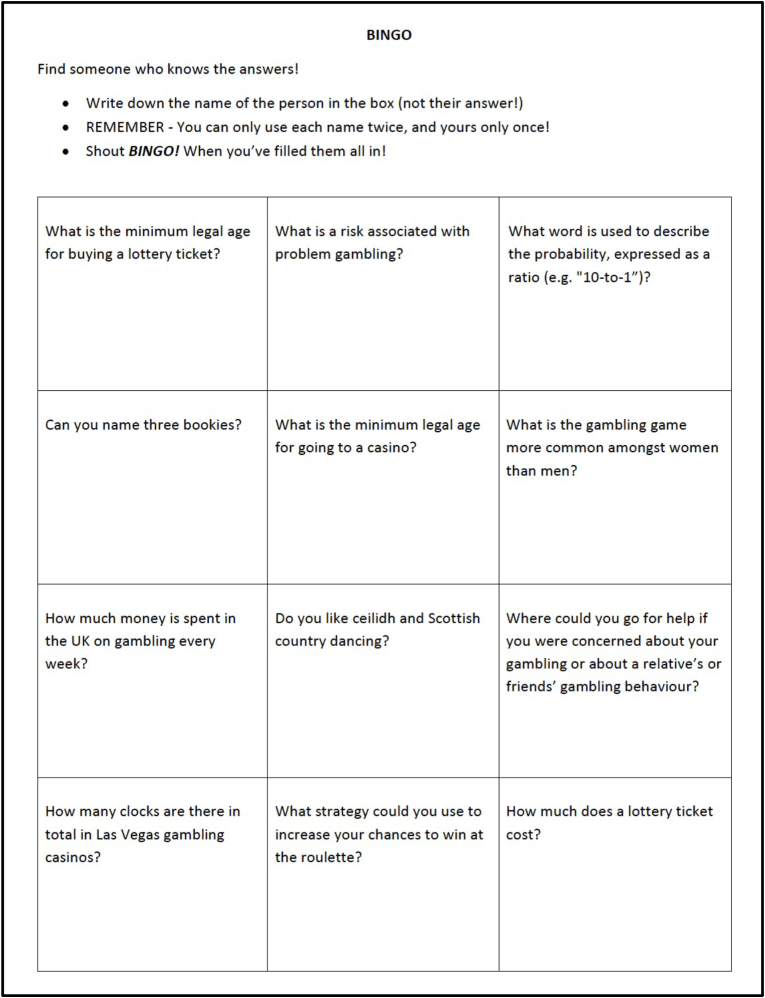

Fig. 1.

Example activity intended to support teaching about risk, Key Stage 4 (ages 14-16 years) teaching pack, PSHE Association/GambleAware (GA-PSHE-KS4-01).

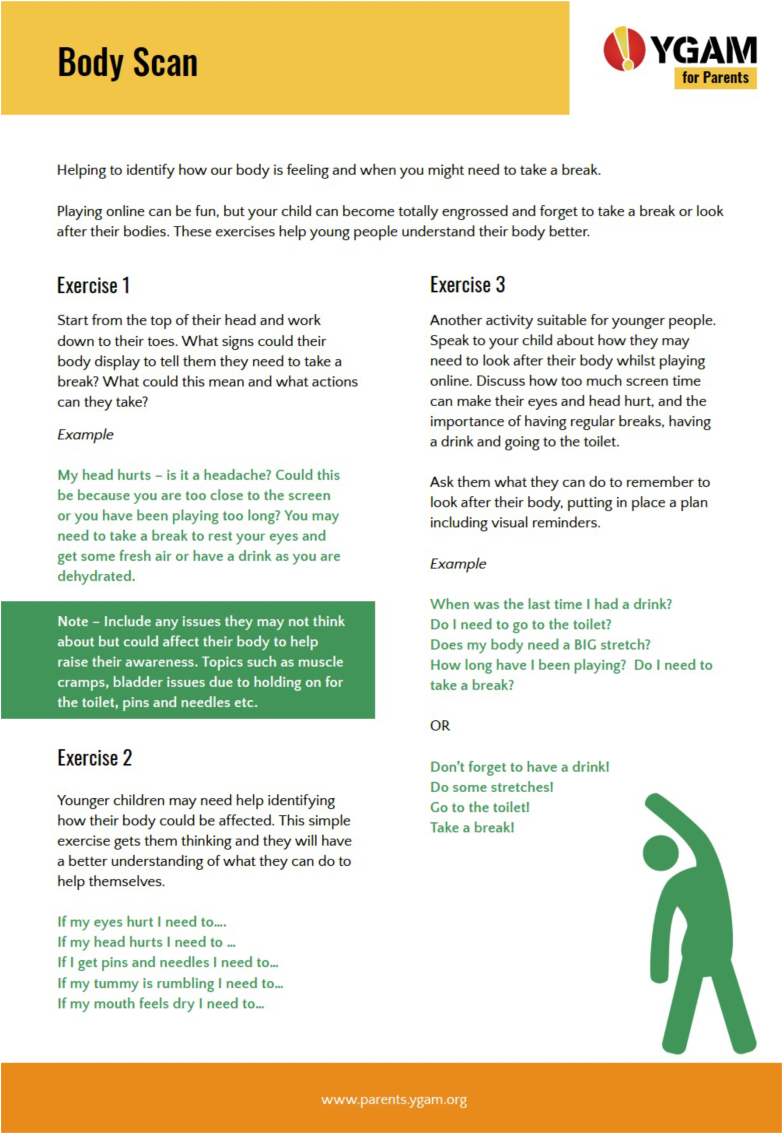

Fig. 3.

Gambling scenarios, Key Stage 4 (ages 14-16 years) teaching pack, PSHE Association/GambleAware (GA-PSHE-KS4-01).

5.1.3. The logic of medicalisation

A logic of medicalisation (e.g., referring to symptoms and signs, and directing people to treatment services) also contributes to the construction of the discourse. Children and young people are to be taught about the signs and symptoms of gambling or gaming addiction and about accessing treatment-based services. Parents are similarly encouraged to learn about addiction and to ask their children if they can identity if they are addicted. A parent-facing factsheet featuring on the 2020 YGAM Parent Hub stated:

Would your child recognise if they were addicted to online play?

Ask your child what behaviours someone who is addicted to online gaming would show? … Can they identify if they play too much? … If they recognise they may play too long, ask them what they feel is a healthy amount and decide on a time (YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSupPr-Gming-07).

Central to this discourse were the logics of balance and alternatives, that is, promoting the adoption of a ‘healthy balance’ to gambling and gaming and achieving this through engaging in alternative activities (including building forts, going rock climbing, and holding baking competitions), and setting limits on the amount of time and money spent on gaming and gambling (or gambling-like features such as loot boxes). A YGAM 2020 Parent Hub factsheet for parents, entitled Helpful Tips, suggested that “[i]f you suspect your child may be gambling too much there are some activities to help you discuss the topic with your child” (YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSup11to14-Gbling-08). Such activities centre on setting limits, tracking of behaviours, and the need to observe and reflect by exploring “[w]hat do they consider the pros and cons of their gambling activities?“, “[w]hy do they gamble?“, “[w]hat other activities can create the same feelings?” and “[w]hen do they consider gambling to tip to become [sic] a problem?” Similar advice is presented in relation to gaming and is adopted throughout the YGAM teaching resources, often partnered with promoting the use of surveys and self-monitoring tools.

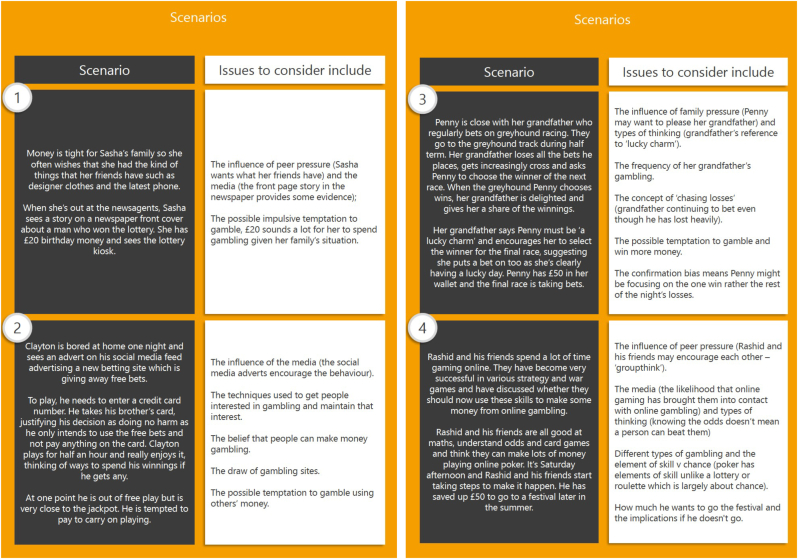

Parents are to encourage children to use reminders to ensure they remember to move, hydrate themselves and to use the toilet when gaming (Fig. 2). That children are interacting with gaming products that encourage forms of play that can result in physical harm or neglecting of basic needs, are turning to gaming due to bullying or difficulties interacting socially, and that anxiety is provoked when not gaming, as described within the materials, are not problematised in and of themselves. These issues appear to be perceived as inevitable, and it is for parents and their children to address them privately.

Fig. 2.

Parent-facing advice and information sheet, gaming-related activities section, YGAM Parent Hub 2020 (YGAM-PH-2020-ActPr-05).

Along with the provision of facts, tips, tools and links to services, children and young people are encouraged to actively participate in their creation and dissemination. For example, at various stages in the YGAM curriculum, teachers are provided with lesson plans in which students are instructed to develop communications materials that raise awareness about the harms of gambling or gaming and provide behavioural advice and signpost to services. In this way teaching about the harms of gambling and gaming is articulated with student-led production and promotion of responsible/safer gambling/gaming materials.

5.2. Political logics

Analysis of the resources revealed the ways in which gambling education discourses normalise and legitimise certain practices, identities, and understandings while obscuring others. It is here that the logics of equivalence and difference capture the political aspects of the resources – the mode through which social practices are instituted and reproduced while other ideas and possibilities are concealed and marginalised.

5.2.1. Logics of equivalence and difference

The logic of equivalence is observed in the way equivalences are drawn between gambling and other industries or issues. This serves to establish a unifying structure to the discourse, incorporating other social projects and elements – simplifying the social space and backgrounding differences. Teachers are advised that gambling is a topic to be taught in schools just like any other risky behaviour, such as the use of alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drugs. Parents are similarly advised to speak with their children about gambling and gaming harms just as they would with other topics like smoking, illegal drugs, and sex. A chain of equivalence is therefore established linking these risky behaviours, which is further extended to include the solutions – building knowledge, resilience, rational thinking, and personal responsibility. Equivalence is similarly established in the way the resources claim that the skills that can be obtained through their delivery will help children and young people in other aspects of their lives, rendering them resilient and resourceful more broadly.

Similarly, the gambling industry and its advertising practices are portrayed to parents and teachers as being just like any other industry. For example, the 2020 YGAM Parent Hub stated that:

Advertising is a powerful tool used by companies to reach consumers all over the world, and gambling companies are no different to other organisations, exploring many different avenues to reach the masses (emphasis in original, YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSupPr-Gbling-03, InfoSup11to14-Gbling-02 & InfoSup15to18-Gbling-02).

The PSHE Association/GambleAware KS4 teaching resource similarly explained that:

The purpose of this lesson is not to demonise the gambling industry. They are promoting their trade just like any other potentially risky pastime might, fully sanctioned by law … The aim is to create a sense of balance by developing a more objective portrayal of gambling (GA-PSHE-KS4-01).

In this way diverse aims and practices such as addressing gambling and gaming harms, teaching children about health and risky behaviours, safeguarding, and promoting the health and wellbeing of children and young people, obtaining financial independence, and building digital resilience are united and seemingly blended into a unifying ethos of personal responsibility and risk management. This articulation involves the logic of rhetorical redescription (Howarth, 2010), whereby the concept and language of responsible gambling are rearticulated and transformed into social practices of preventing gambling and gaming harms among children and young people. The materials display a rhetorical alignment where the logic of responsible gambling is aligned with the need to protect children and young people from gambling and gaming harms. Similarly, market rationality and being an informed, responsible, and in control consumer are conflated with being safe and protected. In this way teachers, children, young people, and their parents are articulated within the larger common project of responsible gambling, and the wider corporate-favoured individual responsibility agenda (Howarth et al., 2000). This is facilitated by the reproduction of the identity of the responsible gambler and gamer (and consumer, more broadly), providing a subject position within the discourse with which teachers, parents and students can identify and strive to assume. Similarly, the notion of problem or unhealthy gambling (and gaming), and the problem or irresponsible gambler (and gamer) is constructed as the antagonistic and undesirable other. Thus, the organising and unifying principle of responsibility and rationality embodied by the informed and responsible gambler versus the problem, uninformed or irrational gambler divides the social space around two antagonistic poles. An instructive example of how this is achieved is through the provision of scenarios or vignettes which describe the right or the wrong type of gambling behaviours. For example, Fig. 3 displays scenarios that are provided to teachers to share with students as part of a lesson on gambling behaviours within the PSHE Association/GambleAware KS4 teaching pack.

Among other instructions, teachers are advised to:

Allow for a 10-minute class discussion to explore some of the issues that emerge from the scenarios such as:

-

•

the reasons why people might take the risks associated with gambling;

-

•

what each character should do and why;

-

•

the importance of an objective approach to risk assessment.

The logic of equivalence thus captures the emergence of the gambling education discourse structured around the identity and practices of the responsible and in-control gambler (and gamer).

The intersecting logic of difference serves to manage and contain grievances “so that the existing order can be reproduced without direct challenge” (Howarth, 2010). The logic of difference captures the differential incorporation (or even co-optation) of diverse identities and demands into the internal detail of the discourse, thus providing social subjects with different identities and functioning to keep elements “distinct, separate, and autonomous” (Glynos & Howarth, 2007). It is here that the concept of risk is employed to dissolve equivalential chains that may form to contest the presence and tolerance of harm to children and young people and how this should be addressed. In this way teachers, students, and parents are informed that everyone is different, and that risk arises from an individual's inherent faulty thinking and impulsive decision-making and is related to the ‘type’ of gambler or gamer they are, and what ‘feelings’ and ‘emotions’ they derive from such activities. It is therefore for individual children, young people, and families to address these issues. This is to be achieved by receiving education and adhering to the advice, tips, and tools promoted in the resources and through making informed, rational decisions. In this way the resources articulate the role that teachers, parents, and students (and industry, governments, and others) have in relation to each other (the logic of difference) and the unifying concept of responsible gambling and the responsible gambler (logic of equivalence). Put simply, the concept of responsibility unites while the concept of risk simultaneously divides.

The articulation of different subject positions rests heavily on problematising children and young people (as outlined in the social logics), supplementing the concept of risk in internally dividing the discourse and creating a system of differences. By identifying children and young people, their lack of knowledge, skills, control, and responsibility as the issue of concern, unique but related subject positions emerge – teachers are to provide knowledge and skills, parents need to have conversations and use parental blocking tools, and children and young people are to engage with the prescribed activities, learn the facts, control their impulsivity, delay gratification, and adopt the right behaviours. This practice reinforces the notion that those who cannot or will not acquire restraint and knowledge thus constitute the pathologized or irresponsible minority and are to be viewed as responsible for the harms they experience. This reveals one of the ways in which the resources serve to reproduce the hegemonic discourse of responsible gambling which rests on problematising people and pathologizing the harms.

5.2.2. Hegemonic practices

The act of providing educational resources can be seen as serving to manage and dissipate demands and grievances by giving the appearance that ‘something is being done’ while simultaneously doing little to “disturb or modify a dominant practice or regime in a fundamental way” (Howarth, 2010). A similar process is captured by the way the resources create a veneer of being critical in nature. Each of the school-based resources provide lessons in which teachers are intended to engage students in critical analysis of the gambling and gaming industries' advertising practices and product design, as well as in several debate and discussion-based activities. Indeed, the resources openly acknowledge the need to provide students with skills to critique the issue of gambling and the associated risks, and claim to teach critical thinking skills. For example, teachers are informed that:

Providing young people with the skills and strategies to think critically about gambling and the risks it poses is therefore crucial. … This resource intends to fill that gap (GA-PSHE-KS4-01).

These elements of the discourse reveal the reductions, simplifications and omissions that have occurred in the process of its construction and reproduction (Clarke, 2012). Superficially the resources appear to encourage children and young people to learn about and debate topics such as policy approaches to regulating gambling and gaming, who is responsible for keeping them safe from harm, and who is vulnerable to addiction. However, the way in which these issues are conceptualised and framed, the content of the supporting information and references provided, and the aspects and topics that are deemed ‘up for debate’ all potentially shape and constrain how students and teachers engage critically which the topics. This in turn limits the extent to which they are empowered to question and contest the social, economic, political, and cultural origins and determinants of gambling harms, the distribution of harms and vulnerabilities, and the power dynamics at play – all central pillars of critical pedagogy (Fitzpatrick & Tinning, 2014; Giroux, 2020).

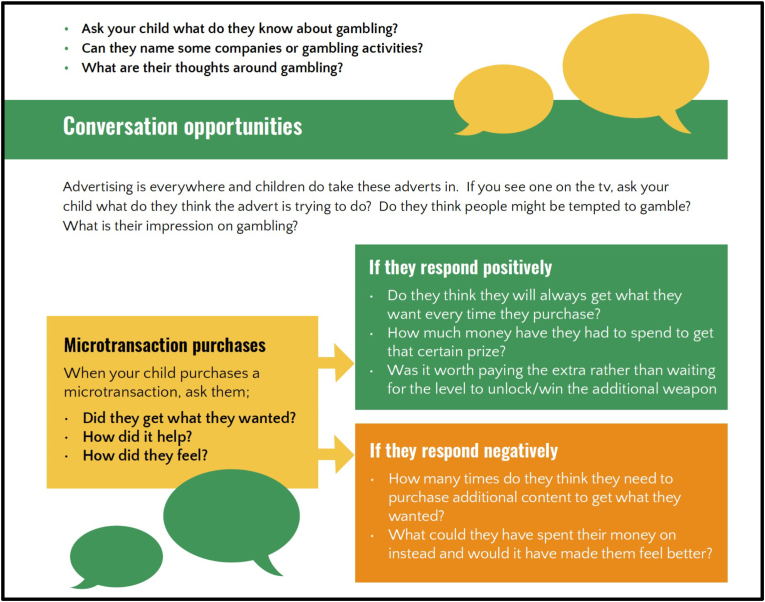

Activities centred on analysing gambling and gaming advertising content and form are designed in such a way as to give the impression that critique is a technical exercise as opposed to one based on questioning industry practices or their right to market harmful products. The resources intend for students to learn how to identify how advertisements ‘work’, about developments in design and technique over time, and to appreciate that different forms of media are used. It is for individuals to use these skills to ensure that they are not influenced by advertisements. Similarly, parents are advised to discuss advertisements with their children, identifying what the advertisements are doing, how they encourage gambling and how advertising makes them feel (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Section from an information document directed at parents titled Engaging with your child, Gambling Information & Support for Primary-Aged Children, YGAM Parent Hub, 2020 (YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSupPr-Gbling-05).

Other forms of corporate marketing such as corporate social responsibility (CSR), including the funding of research, education and treatment, the use of affiliates, and the promotion of complex highly profitable in-play sport bets, are not included. More contested forms such as VIP schemes, and free bets are mentioned but not explored in any detail. The use of such techniques and others including the portrayal of winning, odds, and glamour within advertisements are problematised and articulated within the discourse in ways that cast them as influences that children and young people are to accept and learn about. Gambling and gaming advertising, as entities of concern, are normalised, and re-articulated within the logics of business conduct and marketing strategies.

The YGAM resources include debate and discussion-based lessons that focus on advertising and the role of the Gambling Act in liberalising gambling advertising. Other lessons call upon students to consider what “the most and least ethical form of marketing?” are or to debate whether advertising should be restricted until after the watershed1 (e.g. YGAM-Sch-Y11-L5). However, by emphasising concepts like ‘opinions’ and ‘debates’, with no reference to health, equity, ethics, human rights or legal frameworks for example, such lessons potentially lack depth and meaning, and the discourse remains silent on how these debates are conducted in the social and political realm, how different actors seek to influence the policy process, the conflicting views on the impacts of advertising, and whose interests should be seen as legitimate, and prioritised. Policy and regulation are posed as points of discussion or opportunities to express opinions, whereas interventions based on risk assessment, personal responsibility and rational decision-making are presented as the actionable solutions to gambling and gaming harms – these approaches are not offered up for debate. This reinforces dominant industry-favoured framings that ever more research is needed, there remains open debate about the harms, it is too early to undertake decisive far-reaching policy reform, and divergent views are therefore of equal legitimacy (Oreskes & Conway, 2011).

Other critical aspects include understanding how the gambling industry makes profit. However, the link between harms, addiction and the industry's profits is not elaborated upon in the materials analysed. One example is a YGAM lesson intended for year 8 students titled The House Edge (YGAM-Sch-Y8-L4). Students are to undertake activities to learn about odds and probability which are accompanied by the following questions:

ACTIVITY: HOW DOES PROBABILITY APPLY TO GAMBLING?

-

•

How do gambling companies make their money?

-

•

Are young people aware of the probability of them actually winning?

-

•

Do you think this would impact the likelihood of them participating?

In this way, gambling industry revenue is portrayed as being generated from the loss of customers due to the low odds of winning. The addictive nature of products, the placement of gambling outlets in deprived areas, the use of advanced marketing techniques such as VIP schemes and third-party affiliates, and gambling policy are not connected in the materials to the industry's accumulation of profit.

Notably, the YGAM resources include lessons in which students are intended to debate gambling policy and the regulation of gambling advertising and gaming features. However, the scope of these activities is narrow and limited to a specific product or policy question and the ways in which the teachers and students engage with the debates topics are potentially influenced by the details and references provided by the resources. Debates on gambling-like features of games are focused on loot boxes, and debates about gambling policy are focused on advertising. Teachers and their students are not informed about the highly contested and political nature of gambling policy more broadly, how, where and by whom gambling policy is formed, how to engage with this process, and the rights of citizens to decide the role of gambling in their societies and to shape their gambling environments. That gambling policy has undergone radical changes in the last 40 years and that multiple advocacy groups are seeking reform to gambling policies and the industry practices and products sanctioned by these policies, are not addressed in the debates, despite lessons specifically referring to the Gambling Act 2005 and the need to protect vulnerable groups, for example. The debate activities are preceded, followed-up by or presented alongside suggestions to design or discuss individual-level actions that can be taken to achieve responsible gambling behaviours and reduce risk, such as designing responsible gambling posters or asking students to list actions they are going to take to change their behaviour. Students are instructed to take action, but in the form of responsible gambling-like marketing and personal behaviour change.

The gambling education discourse may therefore be seen as pseudo-critical as many of the critical elements are detached from the social and political context and do not challenge or contest the current order of things in a comprehensive or actionable way. It is in this way that a logic of incrementalism can be seen to be at play serving to give a sense of challenging the status quo while posing little threat to business-as-usual (Smerecnik & Renegar, 2010).

5.3. Fantasmatic logics

Fantasmatic logics help in understanding and critiquing how and why certain social practices or policies appeal to, or ‘grip’, agents and in this way explain how and why certain social practices or policy systems resist change, and conversely the speed and direction of change when it does occur. As described above, two dimensions of the fantasmatic narrative, beatific and horrific, are often observed. The former is captured in the stated aims and expected impacts of the resources. Many of the materials analysed made claims that the resources promote skills acquisition and understanding, and that their delivery would ensure children and young people's safety, resilience, health, and well-being, now and into the future. This is particularly evident within the explanatory letter provided by YGAM for distribution to parents:

The topics covered will provide children and young people with the knowledge, understanding and skills to live safe and healthy lives, empowering them to make informed choices (YGAM-PrSchRes-01 & YGAM-KS5-04).

YGAM materials directed at professionals working in the youth sector state:

Our programme aims to prevent and reduce gaming and gambling related harm, empowering children, and young people to make informed choices developing critical thinking skills and resilience for life (YGAM-KS5-16-05 & YGAM–NCS–03).

Speaking directly to young people, a BigDeal website blog explains that:

Gambling can be fun, but it also has the potential to cause harm. Gambling should also never become a way to help you deal with anything else in life you don’t feel able to cope with. The tips below can help you reduce your risk of harm, and protect your mental health if you gamble (GC-BD-yp-08).

The 2020 YGAM Parent Hub explained to parents that by adopting the suggested steps outlined on the website they could ensure that children could gamble in a balanced and healthy way:

Children gambling at young ages does not mean they will turn into problematic gamblers, however there are steps you can take to ensure that when they do gamble they can establish a healthy attitude and balance (YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSup11to14-Gbling-03).

Having discussions and conversations about the topics of gambling and gaming were explicitly described to parents as measures through which harms could be prevented. The 2020 YGAM Parent Hub also proposed that by teaching children about certain life-style skills and involving them in household functions such as cooking, shopping and budgeting they would be less likely to adopt harmful behaviours and activities (see the supplementary materials for additional quotes related to the fantasmatic and other logics).

Therefore, while it is acknowledged that children and young people are being exposed to risks of harm, the dominant messages are that by learning about gambling, gaming and the risks, how to control their emotion-driven and irrational thinking, how to appreciate the value of money and make financial plans and perform risk assessments and self-monitoring, they will be protected from these harms and lead healthy lives. Thus, the political nature and origins of current gambling practices and policy regimes from which these harms emerge and the ideas and assumptions that inform these remain in the background and go uncontested. Similarly, the normalisation of gaming in children and young people's lives and the largely unregulated ways in which these products are designed and marketed, are predominantly constructed in the discourse as incontestable and inevitable, particularly in the information presented to parents. In this way, education and parental conversations are promoted as not only being sufficient and effective in preventing (or minimising) gambling and gaming-related harms, but they are also presented as the route to lifelong health and resilience.

This beatific narrative serves to deflect from the void created by the unknowns surrounding the risks posed by gambling and gaming and their rapid evolution and expansion, the unpredictable impacts of technological innovation, and the industries' conduct. By structuring this narrative around concepts like knowledge, understanding, control, resilience, skills, risk assessment, and choice, the discourse creates a sense of order and reason, defending against the emergence of challenges to the status quo and potentially rendering other perspectives on what is needed to adequately protect children and young people from gambling and gaming harms unthinkable or extreme in nature.

The horrific narrative was apparent through the use of value-laden statements which created an implicit understanding of what would transpire if children and their parents did not adopt the choices and recommendations detailed in these resources. Much of the content adopts a moralising tone (as described in the social and political logics), with the implication being that behaviours that do not conform with what is depicted as being the right, informed, and rational choices are therefore foolish, faulty, or wrong. Harms incurred are therefore the fault of parents, children, and young people.

5.3.1. Markers of fantasy: contradictions and slippages

Close analysis of these narratives reveals the presence of noteworthy contradictions and slippages, exposing the ways in which the fantasmatic logics ‘smooth’ over or conceal the discourse's lack of completeness or points of weakness. Of particular relevance here is how the discourse handles and obscures the uncertainty around gambling and gaming harms, including their form and likelihood, the highly contested nature of gambling policy in the UK, and the lack of robust evidence on how to prevent gambling and gaming-related harms. This was evident in the slippage in how different concepts and meanings were inconsistently and interchangeably used within and across the materials. For example, signs, symptoms, risk factors, risks, harms, prevention, and treatment were used interchangeably and there was a tendency to conflate the risk aspect of gambling as a game of chance or ‘risk’ and the concept of risks of harm associated with engaging with gambling activities. By not attending to the lack of conclusive data on, and understanding of, the risks of experiencing harms and at what levels or forms of gambling (or gaming), the resources obscure the contradiction present in instructing students and parents to assess and manage the risks. For example, the PSHE Association/GambleAware KS4 teaching resource instructs teachers to:

Ask students to remember that risk = the potential harmthe likelihood of the harm happening (emphasis in original, GA-PSHE-KS4-01).

How children, young people, parents, and teachers are intended to apprehend and consider the risks associated with gambling and gaming when the likelihood of different harms occurring is still widely unknown and contested in broader social and political contexts is not addressed within the discourse. The concepts of risk and harm are articulated as given entities that can be grasped with certainty while simultaneously described inconsistently and ambiguously both within and between programmes. Serious harms (such as relationship breakdown, job and home loss, violence, and suicide) or their implications are rarely mentioned (if at all) and, when mentioned, explored in little detail. Finally, and contrary to the stated goals of educating about and preventing gambling harms, it is notable how little gambling harms and determinants of their emergence and inequitable distribution were explicitly discussed in the resources. The discourse disproportionately focuses on building understanding of why people gamble or game, the products and their producers, how advertising ‘works’, risk, self-monitoring and risk assessment, personal responsibility, lifestyles, and people's, particularly children and young people's, impulsive and irrational decision-making.

There is also contradiction in the way the nature of the problem is articulated, particularly regarding the location of the problem. While overwhelmingly portrayed as an issue of personal responsibility and decision-making, at times reference is made to the addictive and seductive nature of gambling and gaming products as well as industry advertising. The 2020 YGAM Parent Hub explained to parents in a document exploring the issue of microtransactions within games that:

The issue being raised is both activities [gambling and microtransactions] are similar in the psychological sense; They have addictive content which activate the brains [sic] chemical reward system and create feelings of uncertainty, anticipation and excitement … The issue starts as their brain becomes used to the rewards and craves more (YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSup11to14-Gbling-04).

In this way the discourse constructs an understanding of gambling and gaming addiction as being like a drug addiction, with references to downers, highs, addictive products, and the need for substitute products or activities. The 2020 YGAM Parent Hub provided a list of “Top games” in which some were described as being “seriously addictive”. That games with such addictive potential are available and that children and young people are habitually playing these games are not called into question, and the ways in which the concepts of choice and informed decision-making may be incompatible with the normalisation of addictive products that are strategically designed and marketed remain unexplored. Instead, there are instances when teachers are provided with lessons in which they are advised to instruct students to identify steps they can take as individuals to “stay safe” while gaming.

These moments in which the addictive potential of the products, the ways in which they interact with the brain's reward system and alter consumers' neurochemistry and when the power and sophistication of marketing are articulated reveal the tensions at play in the discourse. On the one hand the serious nature of the context and the potential for harm is acknowledged but the dominant discursive construct is that people are the problem, and their understanding, choices and behaviours are to be changed and rendered the focus of interventions. The materials guard against these sites of contradiction becoming potential opportunities for contestation and conflict by reassuring teachers and parents that speaking with and informing children and young people will protect them from harm - the education fantasy.

Contradiction is also evident in the discursive construction of the drivers behind children's behaviours and the actions parents and teachers are advised to take. As described under the social logics, children and adolescents are portrayed to teachers and parents as being irrational and driven by emotion. Their brains are described as not having developed the capacity to make rational decisions: “Remember children and teenagers aren't prepared to balance emotion and logic to make healthy choices – they won't be considering the consequences of their actions” (emphasis in original, YGAM-PH-2020-ActPr-10).

Despite these assertions, most of the learning activities directed at children and young people are based on teaching about facts, risks assessment and self-monitoring, and parents are instructed to have conversations with their children about harms, how to spot signs of addiction, the responsible use of money and budgeting for a household. For example, one document provided by the 2020 YGAM Parent Hub stated:

At this age, a child’s brain is very much dictated by their emotions and feelings. The rational part of their brain has not fully formed. Opening a loot box, purchasing a skin, winning on the tombola or having enough tickets to ‘win’ an amazing prize generates rewards in the brain which a child enjoys and wants to repeat again and again (YGAM-PH-2020-InfoSupPr-Gbling-04).

The same document goes on to encourage parents to educate their children about the odds of winning and making informed purchasing decisions.

The scale, nature, and impacts of external influences are similarly articulated in ways that are contradictory and inconsistent with proposed responses to address these influences. The influence of product design and marketing strategies are at times described as being able to “hook” or “trick people”. For example, a PSHE Association/GambleAware KS2 teaching resource, titled Chancing it, specifies that teachers should:

Take feedback. Draw some conclusions, such as:

Adverts or pop-ups are often designed to try and ‘hook’ people into gambling or to keep them trying over and over again; people can be persuaded or tricked into thinking it is easy to win (GA-PSHE-KS2-03).

The same presentation instructs teachers to explain to their students “that gambling is an activity meant for adults, but that sometimes even adults can find it difficult to manage the risks and feel they can easily lose control”.

While a number of influences are mentioned within and across the different resources, peer pressure is often elevated in relation to other influences. This is done despite the fact that at other stages in the materials Gambling Commission survey data collating responses from young people on why they gamble is displayed suggesting that 6% of those surveyed listed peer pressure as a factor associated with their reasons for gambling, ranked below a number of other factors including fun and winning. YGAM teaching materials reported that peer pressure was ranked 5th among the reasons why young people engage in gaming, however, as with gambling, peer pressure is emphasised as a key influence of gaming behaviours. The YGAM resources outline lesson plans in which students are instructed to “create a poster to help young people stand up to peer pressure when it comes to gambling”.

That children and young people are exposed to such an array of influences and are to be expected to identify, resist, and build resilience to these forms of manipulative environments and products are not challenged within the materials. Contrastingly, the central theme throughout the resources is that children need to build resilience and take personal actions to mitigate the impacts of these influences. For example, the PSHE Association/GambleAware KS4 teaching resource provides teachers with prompts to share with students advising them on how to avoid being influenced, including “avoid friends who are gambling”, “build a fulfilling life where the stimulation from gambling would not be required”, and “balance the likely outcomes to recognise the reward could be a false reward; it is the buzz not the money itself which is the draw which can be gained in healthier ways e.g. exercising, finding a subject/job/cause which motivates a person” (GA-PSHE-KS4-01).