Abstract

Voltage-gated ion channels are plasma membrane proteins that generate electrical signals following a change in the membrane voltage. Since they are involved in several physiological processes, their dysfunction may be responsible for a series of diseases and pain states particularly related to neuronal and muscular systems. It is well established for decades that bioactive peptides isolated from venoms of marine mollusks belonging to the Conus genus, collectively known as conotoxins, can target different types and isoforms of these channels exerting therapeutic effects and pain relief. For this reason, conotoxins are widely used for either therapeutic purposes or studies on ion channel mechanisms of action disclosure. In addition their positive property, however, conotoxins may generate pathological states through similar ion channel modulation. In this narrative review, we provide pieces of evidence on the pathophysiological impacts that different members of conotoxin families exert by targeting the three most important voltage-gated channels, such as sodium, calcium, and potassium, involved in cellular processes.

Keywords: conotoxins, voltage-gated ion currents, sodium, potassium, calcium, drug discovery

1. Introduction

Marine organisms produce a great variety of toxins. Among them, venomous mollusks cone snails have provided so far more than 6000 different toxins that have been isolated and characterized by more than 100 different species. Cone snails have been the object of huge interest and study since ancient times due to their shell features but mostly for their poison-associated toxins. The main physiological roles of these toxins are for self-defense from predators but also to predate themselves and to compete with other marine species, also thanks to a poisonous sting that may be fatal for humans. The venomous properties of the toxins have been revealed to exert pharmacological bioactivities, especially on a vast variety of pain-associated neurological disorders. Hence, the toxin’s level of poisonousness has been used as an efficient and beneficial pharmacological and therapeutic tool, making conids good candidates for new drug design and development [1,2,3]. Conus-derived toxins, known as conotoxins (CnTX), are venomous small peptides consisting of 5–50 amino acid residues with multiple disulfide bonds among cysteines. An old classification divided CnTX into cysteine-rich and cysteine-poor groups. At present, instead, three CnTX groups are classified based on the cysteine framework gene superfamily and the pharmacological family. The cysteine framework group is underlined by the specific organization of cysteine residues in the toxin primary structure whereas the gene superfamily is based upon the evolutionary relationship between different conopeptides. In particular, CnTXs are translated from mRNA as precursor peptides and cDNA sequencing allows the increased discoveries of new toxin sequences.

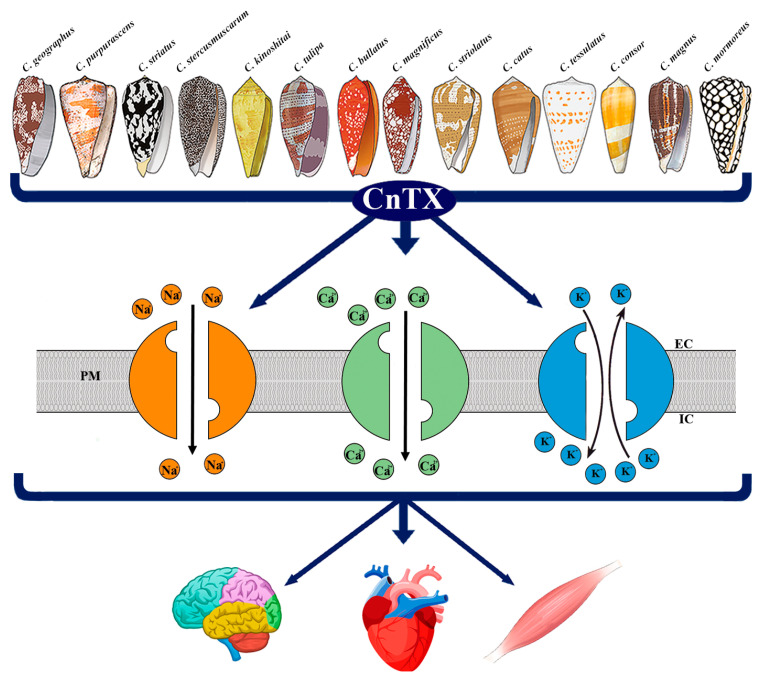

Currently, pharmacological family classification is related to the receptor target and the type of CnTX-target interaction. CnTX included in the same superfamily share a similar signal peptide sequence, which undergoes structural and functional differentiation when they become encoded mature peptides [4,5]. Nonetheless, over 10,000 CnTX sequences have been disclosed and published; however, 3D structural and functional information is still lacking and their pharmacological characterizations have not been elucidated. CnTX includes several different pharmacological families that selectively target specific voltage-gated ion channels, G protein-coupled receptors, enzymes, and transporters [6,7,8]. Currently, CnTXs are under evaluation by neuroscientists and drug developers for their peculiar selectivity to mammalian and human targets and, in particular, for their ability to inhibit voltage-gated ion channels. As an example, the µ-CnTX family exerts its activity by combining multiple peptides action known as “cabal”, which is aimed to ensure the most effective bioactivity through ion channels modulation. Due to their ability to interact with human ion channels, these toxins are considered “specialists in neuropharmacology” and given their therapeutic potential, some of them have been involved in human clinical treatments [9,10,11]. Based on their specific selectivity, CnTX represent basic tools to elucidate ion channel function and their involvement in biological mechanisms and processes. In this review, we focus on the main CnTX pharmacological properties and their modulation of voltage-gated sodium (NaV), calcium (CaV), and potassium (KV) channels acting through different and, sometimes, opposite physiological and pathological mechanisms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative image of CnTX bioactivity via voltage-gated ion channel modulation. Conus derived toxins (CnTX) target numerous and different NaV and/or CaV and/or KV channel subtypes generating ion current fluxes through neurons of central and peripheral nervous systems as well as in heart and skeletal muscle cells. IC = intracellular compartment; EC = extracellular compartment; PM = plasma membrane.

2. Ion Channels

On the plasma membrane, the different distribution of ions and related electrical charges inside and outside the cell generates an electrical gradient known as cell voltage. This trans-membrane potential named resting potential (RP) is specific in each cell type and ranges from −10 to −100 millivolts representing a store of energy for which its variation underlies a series of biological processes. In a steady-state situation, the cell membrane does not allow the free diffusion of ions that may occur only through ion channels. These are complex pore-forming proteins embedded in the plasma membrane characterized by specificity, gating, and conductance. These properties define for each ion channel which specific ion may cross it in the case of it being modulated by a change in voltage, known as voltage-gated channel, or by a ligand as well as the number of ions that may cross the channel [12]. Nonetheless, several different ions participate in the voltage generation; those mainly involved in biological mechanisms are extracellular, such as sodium (Na+) and calcium (Ca2+), and intracellular, such as potassium (K+).

These three cations passing through voltage-gated channels play physiological roles in generating, shaping, and transducing electrical signals in the cells. In particular, potassium (KV) is essential for determining and regulating the RP and cell volume, and sodium (NaV) is responsible for the action potential generation and propagation, whereas calcium (CaV) is mainly involved in cell signaling waves and cascades [13,14,15]. From a structural point of view, voltage-gated ion channels are formed by the main pore-forming domain, which consists of either single or multiple distinct subunits. Once activated, voltage-gated ion channels undergo a conformational modification allowing ion passage through the pore; this is then deactivated/inactivated, returning quickly to a non-conducting state [16]. The ion passage through an ion channel is called ion current and is associated with a change of RP due to the transient change of ion concentrations inside the cell. The membrane depolarization is due to the shift of RP toward positive values and is associated with sodium and calcium entry, whereas hyperpolarization due to potassium exit leads RP toward negative values. A schematic pathway that links ion channel activity and biological processes arise on a sensory domain that receives physical or chemical stimuli and converts them into ion fluxes, which in turn induces a series of signal transduction cascades. A broad volume of studies reports the involvement of ion currents in a variety of physiological processes such as reproduction, gamete maturation, cell volume regulation, cell division, cardiac functionality, skeletal muscle contraction, and neuronal excitability [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Ion current activities are also involved in dysfunctions in some of the overmentioned processes. The disorders, collectively known as channelopathies, are genetic diseases resulting from the malfunction of ion channels that induce a vast array of diseases of the nervous, cardiac, respiratory, urinary endocrine, and immune systems. Among them, the best-described pathologies are hypertension, epilepsy, diabetes, blindness, cardiomyopathy, asthma, gastrointestinal disturbs, and even cancer [29]. A pivotal role in most of the known neurological channelopathies is played by NaV channels dysfunction due to the key role of this channel in the generation and propagation of the action potential, the distinctive feature of neuronal activity. In fact, mutations of the three NaV channels isoforms 1.1-, 1.2-, and 1.6-encoding genes have been shown to be responsible for several intellectual, behavioural, and clinical disabilities. More specifically, NaV channel mutations and disorders in the conducting properties and regulation have been observed in some cases of demyelination, ischemia, and Angelman Syndrome [30,31]. The defects in ion channel functionality are caused by either genetic or acquired factors. Ion channel gene mutations are the most common cause of channelopathies, whereas drugs and toxins targeting ion channels appear to exert contrasting impacts by either impairing ion channel function and/or acting as therapeutic tools able to relieve or even treat human channelopathies [32].

3. Pathophysiological Response to CnTX Voltage-Gated Channel Modulation

3.1. NaV Channels

NaV channels are voltage-gated ion channels responsible for the generation of the rapid RP depolarization known as action potential that, in excitable cells, propagates electrical signals in muscles and nerves in either the central or peripheral nervous system [33]. Since NaV channels underlie neurotransmission, contraction, excitation coupling, and associated physiological functions [33], mutations and defects in their functional activity are associated with several neurological disturbances and channelopathies [34]. From a structural point of view, NaV channels are heteromeric complexes with a pore-forming α subunit of about 260 KDa linked to one or two β subunits of different molecular weights. The α subunit contains the binding site for several neurotoxins and drugs that target the channel and significantly change its activity. The β subunits are involved in different signaling roles in physiological processes such as cell adhesion, gene regulation, and brain development and in the kinetic regulation of channel opening. Both α and β subunits contain the receptors for toxins targeting the channel. Currently, characterized according to the α-pore-forming subunit sequences, nine isoforms of the NaV channels α subunits (1.1–1.9) have been identified. Specifically, isoforms 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and 1.6 are predominantly expressed in the central nervous system, whereas isoforms 1.7, 1.8, and 1.9 are mainly expressed in the peripheral nervous system. In addition, skeletal and heart muscles contain 1.4 and the 1.5 isoforms, respectively [35,36,37,38].

Toxins and venom compounds targeting NaV channels are of particular importance due to their pivotal role played in the neuromuscular system. Together with their pathophysiological action, CnTX have also provided basic information on the molecular structure, function, and subtype-selectivity of NaV channels [39] (Table 1).

Table 1.

CnTX subfamilies targeting voltage-gated sodium (NaV) channel subtypes, functional impact, and pathophysiological activity.

| Species | CnTX Subfamilies | Channel Subunit Targeted | Functional Impact | Pathophysiological Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. geographus | μ-GIIIA | NaV1.4 | block skeletal muscle channels | paralysis | [40] |

| C. geographus | μ-GIIIB μ-GIIIC |

NaV1.1 NaV1.2 NaV1.4 NaV1.6 |

discriminate between muscle and neuronal channels | - | [41] |

|

C. bullatus

C. catus C. consor C. magnus C. purpurascens C. stercusmuscarum C. striatus C. tulipa |

μ-CnIIIA μ-CnIIIB μ-CnIIIC μ-CIIIA, μ-MIIIA |

NaV1 | block channel conductance | paralysis (CIIIA) | [42] [43] |

| C. purpurascens | μ-PIIIA | NaV1.2 NaV1.4 NaV1.7 |

inhibit channel modulation | - | [44] |

| C. stercusmuscarum | μ-SmIIIA | irreversible block of NaV currents |

nociceptive role | [45,46] | |

| C. striatus | μ-SIIIA | NaV1.2 | block of neuronal NaV current |

analgesic activity | [47] |

|

C. tulipa

C. kinoshitai C. striatus |

μ-TIIIA, μ-KIIIA, μ-KIIIB, μ-SIIIB |

NaV1.1 NaV1.2 NaV1.3 NaV1.4 NaV1.6 |

affinity NaV channels |

analgesic activity | [48,49,50] |

| C. marmoreus | μO-MrVIA, μO MrVIB, μO MfVIA |

NaV1.8 | inhibit channel activity | analgesic activity | [51] |

| C. radiatus | ί-RXIA | NaV1.6 | shift channel activation | - | [52] |

Several CnTX families and, in particular, µ-, µO-, δ-, and ι′-CnTX can target NaV channels upon binding specific sites on the α subunits. In particular, they may act as pore blockers that structurally occlude the pore or interfere with voltage sensors [53,54]. These families, in fact, differently modulate channel activity acting as either inhibitors (µ- and µO-CnTX) or stimulators (δ- and ι′-CnTX) of NaV activity. The channel inhibition is underlined by different mechanisms. For example, µ-CnTX blocks ion conductance by binding to the channel’s external vestibule, whereas µO-CnTXs are gating modulators that bind the external side of the pore, causing channel closure [55,56]. Similarly, δ- and ι′-CnTX activate channels by two different mechanisms that prolong the channel’s opening and shift voltage activation to more hyperpolarized potentials, respectively [57]. µ-CnTX are small peptides composed of 16–22 amino acids and three disulfide bonds that, by inhibiting the α-subunit of NaV channels, affect neuromuscular transmission causing paralytic to analgesic effects in mammals [58,59]. Currently, among the 12 CnTX known, μGIIIA was the first one to be isolated from Conus geographus; by binding the NaV1.4 sub-type channel pore, it exerts the inhibition of rat skeletal muscle channels [40]. From the same venom, the two isoforms μ-GIIIB and μ-GIIIC, differing for only four residues, exhibited a different affinity for the muscle subtype NaV channels 1.4 and the neuronal NaV1.1, NaV1.2, and NaV1.6 channel subtypes. These μCnTX can discriminate between muscle and neuronal NaV channels, becoming candidates for therapeutic plans on neurological disorders. Therefore, a wide range of studies was aimed to identify whether interactions between several μ-CnTX and NaV channel subtypes may act as selective inhibitors of NaV channels neuronal subtypes, with possible clinical impact on neurological processes [41]. In this light, several μ-CnTXs with affinities for neuronal NaV channel subtypes were isolated from Conus bullatus, catus, consor, kinoshitai, magnus, purpurascens, stercusmuscarum, striatus, striolatus, and tulipa. Among these, μ-CnIIIA, μ-CnIIIB, μ-CnIIIC, μ-CIIIA, and μ-MIIIA can block the conductance of NaV1 subtypes in amphibian neurons. Some of them, by inhibiting olfactory and sciatic nerve action potentials, modulate pain signals and exert analgesic activity [42]; however, only CIIIA may cause paralysis [43]. μ-PIIIA is a peculiar versatile μ-CnTX that can differentiate NaV channel subtype isoforms by inhibiting NaV1.2, NaV1.4, and NaV1.7 channel subtypes from rat brain, skeletal muscle, and peripheral nerves, respectively. Furthermore, recent studies revealed that μ-PIIIA is a strong inhibitor of NaV channels involved in muscle contraction and, specifically, of NaV neuronal subtypes in both the central and peripheral nervous systems [44,60]. Isolated from the venom of Conus stercusmuscarum, μ-SmIIIA, due to its strong affinity for neuronal NaV channel subtypes, it can irreversibly block NaV currents in different neurons of either amphibians or rats, demonstrating a nociceptive role [45,46]. On the contrary, a robust analgesic action is exerted in mammals by μ-SIIIA from Conus striatus through the neuronal block of NaV1.2 subtype [47]. Strong and mild affinities for neuronal NaV channels were described in several μ-CnTXs, such as μ-TIIIA, μ-KIIIA, μ-KIIIB, and μ-SIIIB, which were isolated from different conids and associated with neuronal pain and analgesic activity in mice affected by inflammatory diseases [48,49,50]. In support of the role of the amino acid sequence, a recently patented invention led to the development of a µ-CnTX peptide with a specific sequence forming a bioactive fragment suitable for pharmaceutical use for either the treatment of NaV channel-associated diseases or replacing anesthesia in a patient undergoing surgery [61].

In this line, μO-CnTX MrVIA, MrVIB, and MfVIA that are isolated from Conus marmoreus play analgesic actions on pathophysiological pains in a large variety of animal models through the inhibition of NaV1.8 channel activity [51]. Although δ- and ι′-CnTX stimulate NaV activity, based on the induction of repetitive action potential oscillations in several cells and tissues, no clear pathophysiological evidence has been observed. Nonetheless, an electrophysiological study aimed to identify the cytotoxicity of CnTX ί-RXIA isolated from Conus radiatus demonstrated that this CnTX induces repetitive action potentials in frog axons and mouse sciatic nerve, possibly through the shift of voltage dependence activation of NaV1.6 subunits toward hyperpolarized levels. It was, therefore, assumed to be applicable in clinical applications for new neurological therapies [10,52]. Currently, increasing structural studies of NaV channels have been performed in complex with toxin and drug modulators targeting either pore and/or voltage sensors. These are providing new hints on pharmacological mechanisms and can discover new isoforms of NaV channels with potential applications in the future [62].

3.2. CaV Channels

Ca2+ is the signaling ion for which its elevation from the resting state is involved in many physiologic processes in most cell types. Ca2+ homeostasis is regulated by an intricate connection of intracellular organelles, binding molecules, and transmembrane channels and transporters. Rapid Ca2+ entry into the neurons gives rise to action potential propagation along cells, activating a cascade of processes such as enzyme activation and gene regulation. CaV channels are at the origin of depolarization evoked by Ca2+ entry into excitable cells of either brain or muscle tissues. This, in turn, is responsible for most physiological functions as Ca2+ dependent muscle contraction, neurotransmitters release, gene transcription, and others. Dysfunctions in these processes, therefore, may alter neurotransmission and gene transcription generating neuropathic pain and related disease states [63,64]. Ca2+ channels are made by 4–5 different subunits, among which the α1 includes the voltage sensor, related apparatus, and the conduction pore [65]. According to the voltage changes and depolarization amplitude needed for their activation, CaV channels are organized into two categories: high- and low-voltage activated Ca2+ channels. The most known members of CaV channels are (i) the high voltage-activated L-type characterized by slow voltage-dependent inactivation involved in cell excitability, contraction, gene expression regulation, and oocyte maturation; and (ii) the P/Q-, N-, and R-types that are more prominently active in fast neuronal signal transmissions [23,66]. T-types are the low voltage-activated channels present in either neurons or smooth and cardiac muscular tissues. N-type CaV2.1 and CaV2.2, in particular, play important roles in the transmission of pain signals to the central nervous system. About ten different genes encode for different types of CaV subunits that are grouped into three major classes (CaV1, CaV2, and CaV3). Specifically, the CaV1 family encodes four different types of L-type channels, CaV2 family for 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3 corresponding to P/Q type, N-type, and R-type channels, respectively, whereas the CaV3 family includes three different types of T-type CaV channels [67]. Following channel gating, once Ca2+ ions are released into the cytosol, they behave as second messengers binding a large number of proteins and, in turn, influence multiple cell functions and complete several physiological processes [68]. Although most of the studies have focused on the pivotal involvement of CaV1.2 and CaV2.2 isoforms in the modulation of pain states, some hints also revealed the involvement of T-type CaV3.1–CaV3.3 with a special focus on the CaV3.2 knockdown effect in mechanical, thermal, and chemical pain diseases [69] (Table 2).

Table 2.

CnTX subfamilies targeting voltage-gated calcium (CaV) channel subtypes, functional impact, and pathophysiological activity.

| Species | CnTX Subfamilies | Channel Subunit Targeted | Functional Impact | Pathophysiological Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. pennaceus | ω-PnVIA ω-PVIB |

HVA CaV | selectively but reversibly block HVA currents | - | [70] |

| C. textile | ω-TxVII | CaV | block CaV currents | - | [71] |

| C. geographus | ω-GVIA | CaV | irreversibly block CaV channels | - | [72] |

| C. magnus | ω-MVIIA ω-MVIIC |

CaV2.2 P/Q-type CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 |

inhibits channel activity blocks channel activity |

analgesic on chronic pain neuroprotective effect |

[73,74] |

| C. moncuri | ω-MoVIA ω-MoVIB |

CaV2.2 | channel affinity | - | [75] |

| C. striatus | ω-SVIA ω-SVIB ω-SO-3 |

CaV2.2 CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 N-type CaV2.2 |

targeting binding affinity inhibition |

paralytic effect lethal injection attenuates acute and chronic pain |

[76,77] |

| C. catus | ω-CVIE ω-CVIF ω-CVID |

CaV N-type CaV2.2 |

affinity antagonist activity | inhibition of nociceptive pain; reducing allodynic behaviour alleviates chronic neuropathic pain reduce allodynic behaviour | [78,79,80] |

| C. fulmen | ω-FVIA | N-type CaV2.2 | inhibition | reduces nociceptive behaviour, neuropathic pain, mechanical and thermal allodynia | [81] |

| C. textile | ω-CNVIIA | N-type CaV2.2 | inhibition | blocks neuromuscular junction, paralysis, death | [82] |

| C. pergrandis | α-PeIA | GABAB receptors coupled to N-type CaV | blocking activity | analgesic activity | [83] |

|

C. victoriae

C. regius |

α-Vc1.1 α-RgIA α-AuIB α-MII |

GABAB receptors coupled to N-type CaV2.2. | inhibition | analgesic activity on sciatic nerve ligation injury; allodynia relieves | [84,85,86,87] |

In the 1990s, numerous studies aimed at identifying new conopeptides, which which its homologues would exhibit possible affinity for CaV channels. However, it was only later that these peptides were characterized and their possible similarities disclosed. The in vitro studies of toxin administration and, in particular, their effects on neuropathic disturbs have been progressively evidenced, and the clinical applications for relieving different pathologies were established. The most known CnTX able to modulate CaV channels, by occluding the channel pore and, thus, preventing Ca2+ entry, is the ω-CnTX family. Typically, ω-CnTX are peptides that are composed of 24–30 amino acids and belong to the superfamily of disulfide-rich conopeptides [88,89]. In the ω-CnTX family, numerous peptides have been isolated from different conid venoms [90]. Depending on the molecular structure, ω-CnTXs that target neuronal N-type CaV channels have been identified as potential drugs for chronic pain treatments. The antagonism with the N-type CaV also suggested a ω-CnTX-neuroprotective effect through a size reduction in cerebral infarction and the delayed inhibition of neuronal cell death in the hippocampal CA1 area [91].

PnVIA and PnVIB from Conus pennaceus were among the first ω-CnTx identified to be able to discriminate subtypes of high voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ currents in molluscan neurons. In the snail Lymnaea stagnalis, they selectively but reversibly blocked transient HVA currents in caudodorsal cells with negligible effects on L-type currents. Although no clear effects on neurological dysfunctions were reported, they were considered useful selective drugs for relevant CaV channel subtypes [70]. Similarly, ω-CnTx TxVII from Conus textile showed a Ca2+ current block activity for which its effects were studied in the caudodorsal neurons in the mollusk Lymnaea stagnalis. Although preliminary studies on this CnTx did not reveal any pathophysiological effects, it was considered a promising tool for designing selective peptide probes for L-type Ca2+ channels [71].

GVIA from Conus geographus was first investigated in in vitro studies and was shown to induce an irreversible block of CaV channels in frog skeletal neuromuscular junction by preventing acetylcholine release. Furthermore, GVIA, demonstrating a role in the attenuation of the Ca2+ component of the action potential in the dorsal root ganglion of a chick embryo, provided useful information on presynaptic connection mechanisms [72]. MVIIA from Conus magnus is the most popular CnTX since, following its isolation and characterization, it gave rise to a widely used pharmacological preparation able to relieve pain in humans [92]. Ziconotide, or Prialt as a commercial name, is used in the treatment of chronic pain related to cancer pathologies; however, it also decreases spontaneous tremors and locomotor activities. By inhibiting the CaV2.2 channel, MVIIA acts as an analgesic drug for which its therapeutic mechanism relies on amino acid residues such as arginine13 and tyrosine13 positions [73]. Furthermore, the different affinity for the CaV2.2 channel allows discriminating MVIIA from two newly discovered ω-CnTX, MoVIA, and MoVIB, which were identified from Conus moncuri [75]. The search for alternative CnTX is of topical importance since ω-MVIIA induces warring side effects that severely limit its use as a pain reliever [77]. Similarly, some features of ω-MVIIA are in common with ω-MVIIC from Conus magnus, a peptide blocker of P/Q-type CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 channels that is essential in the process of neurotransmitter release underlying the development of spinal cord injury. The block of these CaV channels by the CnTX exerts a specific neuroprotective effect in rats [74]. Three paralytics ω-CnTX that were isolated and characterized in the 90 s from Conus striatus are SVIA, SVIB, and SO-3. SVIA targets CaV2.2 channels and exerts strong paralytic effects in lower vertebrates and milder effects in mammals. SVIB, through both CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 channel activation, is lethal to mice when injected; however, it showed different binding affinity sites with respect to those of GVIA and/or MVIIA [76]. SO-3 is an inhibitor of the N-type CaV2.2 channel and possesses structure and analgesic activity similar to MVIIA. Mainly, it attenuates either acute or chronic pain in rodents and exhibits less evident disturbing side effects than MVIIA (ziconotide) [77].

The ω-CnTX CVIE, CVIF, and CVID from Conus catus are neurophysiological tools useful for the potential therapeutic inhibition of nociceptive pain pathways. The first two CnTX showed a higher affinity for CaV channels in the inactivated state acting on the rat partial sciatic nerve ligation model of neuropathic pain and also significantly reduced allodynic behavior [78]. CVID is an N-type CaV channel selective CnTX displaying higher selectivity and selective antagonist activity for N-type CaV2.2 with respect to P/Q-type channels. For this reason, it has been investigated and tested as an analgesic drug in clinical trials, demonstrating a beneficial action on chronic neuropathic pain with a specific ability to reduce allodynic behavior in mice [79,80].

Isolated from Conus fulmen, FVIA ω-CnTX displayed a remarkable effect on pain and blood pressure. By inhibiting N-type CaV 2.2, FVIA exhibited similar properties to that of MVIIA by reducing, in a dose-dependent manner, nociceptive behavior in neuropathic pain models and mechanical and thermal allodynia in the rat model. Moreover, for this CnTX, the reversible action has been considered a great advantage over MVIIA due to its potency and lowered side effects [81]. Identified from Conus textile, the peculiar CNVIIA ω-CnTX demonstrated an inhibitory effect on N-type CaV2.2 channel accompanied by an unexpected blocking activity on the neuromuscular junction in amphibians. On the contrary, direct intracerebroventricular injection in mice was reported to cause mild tremors and shaking movements whereas higher doses of intramuscular administration in fishes resulted in paralysis and even death. Due to these peculiar characteristics, CNVIIA was suggested to represent a new selective tool for the N-type CaV channel by means of a new and unique pharmacological profile [82]. Together with the large amount of ω -CnTx, some α-CnTXs were shown to act on N-type CaV channels exerting analgesic effects. In particular, the synthesized α-CnTX PeIA showed a potent blocking activity on N-type CaV channels coupled to GABAB receptors. Potential structure–activity applications of PeIA CnTX have been suggested as an analgesic compound for drug design aimed at pain treatment [83]. More recently, the α-CnTXs Vc1.1, RgIA, and some variants, such as AuIB and MII, have been shown to possess analgesic properties through the inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine and GABAB receptors coupled to N-type CaV2.2. indicating a novel mechanism for reducing DGD neuron excitability [87]. Interestingly, the GABAB receptor expression was essential for inhibiting N-type CaV2.2 channels and the development of related α-CnTX analgesia. Although this mechanism is still to be clarified, it has been experimentally shown that α-CnTX successfully acted on partial/chronic sciatic nerve ligation injury models and on allodynia relief [84,85,86].

3.3. KV Channels

KV channels are plasma membrane proteins allowing the selective outside/inside flux of K+ ions in response to the membrane depolarization. KV current activity plays a crucial role in many biological processes and functions such as RP and cell volume regulation, propagation of action potential in nerves, cardiac and skeletal muscles, cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [93]. Furthermore, KV s are essential in the regulation of Ca2+ six transmembrane helices (S1–S6) embedded in the lipid bilayer, forming the voltage sensor domain (S1 to S4) and the pore-forming domain (S5, S6). The voltage sensor domain induces a channel conformational change by sensing RP changes, whereas the interaction with the pore generates K+ ion current fluxes [94]. KV channels include 12 different channel families among which a pivotal role is played by the KV1 family, which contains up to eight isoforms (KV1.1–KV1.8). Among them, KV1.3 was first detected in T-cells and, hence, is considered as a possible target for treating autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis. Subsequently, KV1.3 has been proved to be widely distributed in organs and tissues and mainly expressed in both nervous and immune systems participating in several signaling pathways of either normal and/or cancer cells. In particular, KV1.3 channel expressions and/or alterations are involved in numerous pathophysiological processes, such as insulin and apoptosis sensitivity, neoplastic malignancy, inflammatory diseases, cognitive alterations, and anxiety [95]. More recently, it has been shown that the inhibitors of the KV1.3 channel reduce neuroinflammation in rodents together with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease and trauma derived brain injury likely by enabling microglia to resist depolarization stimuli [96]. Being involved in overmentioned pathologies, the KV1.3 channel and its blockers have been considered as safe pharmacological tools for chronic inflammatory disease therapies such as type II diabetes mellitus, obesity, and cancer [97]. Among the CnTX studied so far, a few can modulate KV channels (Table 3).

Table 3.

CnTX subfamilies targeting voltage-gated potassium (KV) channel subtypes, functional impact, and pathophysiological activity.

| Species | CnTX Subfamilies | Channel Subunit Targeted | Functional Impact | Pathophysiological Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. striatus | kA-SIVA | KV | block | spastic paralytic symptoms | [98] |

| C. purpurascens | K-PVIIA | KV1.3 | inhibition | therapeutics for multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and dermatitis |

[99,100] |

| C. radiatus | kM-RIIIK K-CnTX RIIIJ |

Human KV1.2 KV1.2–KV1.5 |

block target |

cardio-protective action no activity |

[101,102] |

| C. striatus | K-Conk-S1; K-Conk-S2 |

KV1.7 | target | therapeutics for diabetes | [103] |

|

C. capitaneus

C. miles C. vexillum C. striatus C. imperialis |

I-superfamily conus peptides | KV1.1 KV1.3 |

block | - | [104,105] |

| C. virgo | ViTx | KV1.1 KV1.3 |

inhibition | - | [106] |

| C. purpurescens | CGX-1051 | KV | inhibition | cardioprotective | [107] |

In 1998, two novel peptides from the venoms of Conus striatus and Conus purpurascens were purified and characterized, demonstrating their ability to bind and block KV channels. kA-CnTX SIVA caused peculiar spastic paralytic symptoms in fish and repetitive action potential oscillations in amphibian nerve-muscle tissues in response to exposure and injection [98]. The latter κ-CnTX PVIIA, belonging to a different family, was first described to bind and block K+ channels [99]. This peptide possesses a disulfide bridge pattern similar to those of ω- and δ-CnTX [108]. Later, it was shown that κ-PVIIA is a functional peptide able to inhibit the shaker KV channel. In particular, a selectivity on the KV1.3 subtype was evidenced, suggesting its potential use as therapeutics for multiple sclerosis since T-cells that express a large number of KV1.3 channels are important mediators of autoimmunity.

In addition, KV1.3 blockers can ameliorate several harmful diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and dermatitis in animal models with a safety profile in rodents and primates [100]. Accurate molecular simulation techniques aimed to disclose the interaction between PVIIA and shaker KV channels demonstrated the existence of two clusters of amino acids that are critical for the binding between the toxin and the ion channel. The consistency of this binding model and the experimental data indicate that the interaction between PVIIA-KV and shaker KV channels may be useful for the development of new therapeutic agents [109].

kM-CnTX RIIIK is a 24 amino acid peptide isolated from Conus radiatus venom identified as the first CnTX able to block human KV1.2 channels. Although structurally similar to µ-CnTX GIIIA, RIIIK inhibits shaker KV expressed in Xenopus oocytes, whereas it showed no affinity with the mammalian KV1.1, KV1.3, and KV1.4 subtypes [101]. When administered before reperfusion, RIIIK significantly reduced the in vivo infarct size in rat hearts demonstrating a potential cardioprotective action. On the contrary, another K-CnTX RIIIJ from the same conid venom did not exert any clear cardio-protective effects when targeting KV1.2–KV1.5. However, both isoforms were suggested to provide new hints for understanding the biological mechanism of cardioprotection [102]. Recently, the affinity of RIIIJ to its KV1 channel target was investigated and disclosed a selectivity on two functional KV1 complexes in mouse DRG neurons. Similarly to K-CnTX, Conk-S1 and Conk-S2, which are able to discriminate different KV1, they were suggested to have therapeutic potentials for the treatment of hyperglycemic disorders. In fact, they were specifically effective in enhancing insulin secretion and lowering glucose levels due to the target of KV1.7 channel. It was demonstrated that Conk-S1 treatments may modulate pancreatic β-cell excitability at high glucose concentrations, eliminating the risk of hypoglycemia. Hence, these compounds were candidates as therapeutic drugs for diabetes by lowering blood glucose levels [103,110].

KV channels targeting is rarer in CnTX concerning the inhibitory activity exerted on both NaV and CaV channels. For this reason, the I-superfamily has received peculiar attention, although no pathophysiological impact has been yet demonstrated. I-superfamily includes a class of peptides with four disulfide bridges that were isolated from venoms of eleven different Conus species. The functional characterization of these toxins showed their ability to block the KV activity of subtype 1.1 and 1.3 channels and to inhibit or modify ion channels of nerve cells. Due to the structural organization of amino acid residues, it was suggested that they may exert different bioactivities and functions [104,105]. Nonetheless, a large number of studies were carried out on the bioactive CnTX superfamily structure; however, only a few indications have been provided on the physio-pathological impact of CnTX-targeting KV channels and their potential therapeutic properties. In fact, some authors recently defined this lack of investigations as “zone of ignorance” in molecular neuroscience, highlighting the need for new in-depth studies on the advantages of using κ-CnTX as pharmacological tools in living cells [111].

At last, it is worth mentioning that ViTx from Conus virgo was the first CnTX member of a structurally new superfamily of conid peptides affecting vertebrate K+ channels. Electrophysiological voltage-clamp studies testing various ion channels indicated that this toxin was able to inhibit KV1.1 and KV1.3 subtypes. However, limited studies were performed on possible biological actions. Its impact and activity remains still unexplored, at present, compared with NaV and CaV channels, and few therapeutic applications of CnTX modulated KV channels have been identified [106].

Moreover, synthetic versions of conopeptides have been tested for therapeutic use. In the case of CGX-1051, the KV channel inhibitor from Conus purpurascens evaluated for possible cardioprotective properties on mammalian models showed a clinically relevant dose-dependent reduction in infarct size in both rats and dogs [107].

4. Conclusions

It is known that millions of adults worldwide suffer from channelopathy-related pain sensation and pathologies. Therapies for lowering pain symptoms have serious expensive socio-economic impacts due to reduced work performances of people facing anti-pain therapies. Furthermore, current medications have been demonstrated to have reduced efficacy and safety and can even be toxic [112]. In addition, a warring association between neurological pains and other diseases, such as cancer-associated chemotherapy, HIV, and diabetes, has been shown. In addition, neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson, and multiple sclerosis syndromes, are often age-related diseases, which affect a large number of people around the world. These are known to be associated with aberrant neuronal excitability often related to ion channels malfunctioning. Therefore, an urgent need to discover and develop new effective pain treatments with almost no side effects has been recognized. In this line, a large field of studies has been focused on clarifying the mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of pain syndromes. The use of CnTX as therapeutic medications is well known [113]; nevertheless, some limitations such as low bioavailability and vulnerability to degradation still impede their widespread clinical use. The use of CnTX as therapeutic medications and research tools is well known for the scientific and societal benefits provided by their clinical application. However, due to their proven toxicity in humans, in a recent review, a potential alarm for their misuse as biological weapons has been highlighted, describing in detail biosecurity concerns along with past and current regulations for CnTX use in medical and research fields [114]. Since, in the last decades, many cardiac, muscular, and neurological disorders have been associated with the malfunction of ion channels, the ability of many CnTX to target ion channel protein subtypes renders them promising pharmacological tools for non-opioid anti-pain therapy. CnTXs are isolated from a large amount of Conus venoms, and their related isoforms fascinate scientists and clinicians due to their enormous potential for diseases diagnosis and care. In this narrative review, we provided evidence of the modulation of CnTX on the three major and most well-studied voltage-gated ion channels. Interestingly, CnTXs targeting NaV, CaV, and KV channels exert different and, sometimes, opposite effects, generating beneficial effects that alleviate pain or inducing, especially in animal models, aberrant channel dysfunctions and damage in organ and system functioning. In fact, some CnTXs reported in this review, even if isolated from the same species, can exert cardio and neuroprotective effects other than analgesic and therapeutic actions, but in contrast, they may generate pathological diseases such as paralysis and death. What is noteworthy is that studies on animal models may be helpful for defining action mechanisms as well as binding and affinity among CnTX, ion channel function, and biological processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fiammetta Formisano for the creation of art graphics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.T., R.B. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.T., R.B. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, E.T., R.B. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gao B., Peng C., Yang J., Yi Y., Zhang J., Shi Q. Cone Snails: A Big Store of Conotoxins for Novel Drug Discovery. Toxins. 2017;9:397. doi: 10.3390/toxins9120397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Layer R., McIntosh J. Conotoxins: Therapeutic Potential and Application. Mar. Drugs. 2006;4:119–142. doi: 10.3390/md403119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terlau H., Olivera B.M. Conus Venoms: A Rich Source of Novel Ion Channel-Targeted Peptides. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:41–68. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaas Q., Westermann J.-C., Craik D.J. Conopeptide characterization and classifications: An analysis using ConoServer. Toxicon. 2010;55:1491–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson S., Norton R. Conotoxin Gene Superfamilies. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:6058–6101. doi: 10.3390/md12126058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halai R., Craik D.J. Conotoxins: Natural product drug leads. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:526. doi: 10.1039/b819311h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin A.-H., Muttenthaler M., Dutertre S., Himaya S.W.A., Kaas Q., Craik D.J., Lewis R.J., Alewood P.F. Conotoxins: Chemistry and Biology. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:11510–11549. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis R.J. Conotoxins: Molecular and Therapeutic Targets. In: Fusetani N., Kem W., editors. Marine Toxins as Research Tools. Volume 46. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2009. pp. 45–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duggan P., Tuck K. Bioactive Mimetics of Conotoxins and other Venom Peptides. Toxins. 2015;7:4175–4198. doi: 10.3390/toxins7104175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallo A., Boni R., Tosti E. Neurobiological activity of conotoxins via sodium channel modulation. Toxicon. 2020;187:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2020.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tosti E., Boni R., Gallo A. µ-Conotoxins Modulating Sodium Currents in Pain Perception and Transmission: A Therapeutic Potential. Mar. Drugs. 2017;15:295. doi: 10.3390/md15100295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeFelice L.J. Electrical Properties of Cells: Patch Clamp for Biologists. Springer Science & Business Media; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berridge M.J., Bootman M.D., Roderick H.L. Calcium signalling: Dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carafoli E. Calcium signaling: A tale for all seasons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1115–1122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032427999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitaker M. Calcium at Fertilization and in Early Development. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:25–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hille B. Ionic channels in excitable membranes. Current problems and biophysical approaches. Biophys. J. 1978;22:283–294. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85489-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannon S.C. Channelopathies of Skeletal Muscle Excitability. Compr. Physiol. 2015;5:761–790. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann E.K., Lambert I.H., Pedersen S.F. Physiology of Cell Volume Regulation in Vertebrates. Physiol. Rev. 2009;89:193–277. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klabunde R.E. Cardiac electrophysiology: Normal and ischemic ionic currents and the ECG. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2017;41:29–37. doi: 10.1152/advan.00105.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misonou H. Homeostatic Regulation of Neuronal Excitability by K+ Channels in Normal and Diseased Brains. Neuroscientist. 2010;16:51–64. doi: 10.1177/1073858409341085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosendo-Pineda M.J., Moreno C.M., Vaca L. Role of ion channels during cell division. Cell Calcium. 2020;91:102258. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2020.102258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubaiy H.N. A Short Guide to Electrophysiology and Ion Channels. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2017;20:48. doi: 10.18433/J32P6R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tosti E. Calcium ion currents mediating oocyte maturation events. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2006;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tosti E. Dynamic roles of ion currents in early development. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2010;77:856–867. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tosti E., Boni R. Electrical events during gamete maturation and fertilization in animals and humans. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2004;10:53–65. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webb R.C. Smooth muscle contraction and relaxation. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2003;27:201–206. doi: 10.1152/advances.2003.27.4.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallo A., Tosti E. Ion currents involved in gamete physiology. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2015;59:261–270. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.150202et. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tosti E., Boni R., Gallo A. Ion currents in embryo development. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today. 2016;108:6–18. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J.-B. Channelopathies. Korean J. Pediatr. 2014;57:1. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2014.57.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meisler M.H., Hill S.F., Yu W. Sodium channelopathies in neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021;22:152–166. doi: 10.1038/s41583-020-00418-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solé L., Tamkun M.M. Trafficking mechanisms underlying NaV channel subcellular localization in neurons. Channels. 2020;14:1–17. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2019.1700082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imbrici P., Nicolotti O., Leonetti F., Conte D., Liantonio A. Ion Channels in Drug Discovery and Safety Pharmacology. In: Nicolotti O., editor. Computational Toxicology. Volume 1800. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2018. pp. 313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Catterall W.A., Lenaeus M.J., Gamal El-Din T.M. Structure and Pharmacology of Voltage-Gated Sodium and Calcium Channels. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020;60:133–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mackieh R., Abou-Nader R., Wehbe R., Mattei C., Legros C., Fajloun Z., Sabatier J.M. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels: A Prominent Target of Marine Toxins. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:562. doi: 10.3390/md19100562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catterall W.A. From Ionic Currents to Molecular Mechanisms. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Catterall W.A., Goldin A.L., Waxman S.G. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and Structure-Function Relationships of Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005;57:397–409. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mattei C., Legros C. The voltage-gated sodium channel: A major target of marine neurotoxins. Toxicon. 2014;91:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Malley H.A., Isom L.L. Sodium Channel β Subunits: Emerging Targets in Channelopathies. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2015;77:481–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deuis J.R., Mueller A., Israel M.R., Vetter I. The pharmacology of voltage-gated sodium channel activators. Neuropharmacology. 2017;127:87–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cummins T.R., Aglieco F., Dib-Hajj S.D. Critical Molecular Determinants of Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Sensitivity to μ-Conotoxins GIIIA/B. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;61:1192–1201. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.5.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green B.R., Olivera B.M. Current Topics in Membranes. Volume 78. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2016. Venom Peptides From Cone Snails; pp. 65–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Favreau P., Benoit E., Hocking H.G., Carlier L., D’hoedt D., Leipold E., Markgraf R., Schlumberger S., Córdova M.A., Gaertner H., et al. A novel µ-conopeptide, CnIIIC, exerts potent and preferential inhibition of NaV1.2/1.4 channels and blocks neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: A µ-conopeptide with novel neuropharmacology. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;166:1654–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang M.-M., Fiedler B., Green B.R., Catlin P., Watkins M., Garrett J.E., Smith B.J., Yoshikami D., Olivera B.M., Bulaj G. Structural and Functional Diversities among μ-Conotoxins Targeting TTX-resistant Sodium Channels. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3723–3732. doi: 10.1021/bi052162j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Safo P., Rosenbaum T., Shcherbatko A., Choi D.-Y., Han E., Toledo-Aral J.J., Olivera B.M., Brehm P., Mandel G. Distinction among Neuronal Subtypes of Voltage-Activated Sodium Channels by μ-Conotoxin PIIIA. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:76–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00076.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang C.-Z., Zhang H., Jiang H., Lu W., Zhao Z.-Q., Chi C.-W. A novel conotoxin from Conus striatus, μ-SIIIA, selectively blocking rat tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels. Toxicon. 2006;47:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.West P.J., Bulaj G., Garrett J.E., Olivera B.M., Yoshikami D. μ-Conotoxin SmIIIA, a Potent Inhibitor of Tetrodotoxin-Resistant Sodium Channels in Amphibian Sympathetic and Sensory Neurons. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15388–15393. doi: 10.1021/bi0265628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao S., Zhang M.-M., Yoshikami D., Azam L., Olivera B.M., Bulaj G., Norton R.S. Structure, Dynamics, and Selectivity of the Sodium Channel Blocker μ-Conotoxin SIIIA. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10940–10949. doi: 10.1021/bi801010u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khoo K.K., Feng Z.-P., Smith B.J., Zhang M.-M., Yoshikami D., Olivera B.M., Bulaj G., Norton R.S. Structure of the Analgesic μ-Conotoxin KIIIA and Effects on the Structure and Function of Disulfide Deletion. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1210–1219. doi: 10.1021/bi801998a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schroeder C.I., Adams D., Thomas L., Alewood P.F., Lewis R.J. N- and c-terminal extensions of μ-conotoxins increase potency and selectivity for neuronal sodium channels. Biopolymers. 2012;98:161–165. doi: 10.1002/bip.22032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang M.-M., Green B.R., Catlin P., Fiedler B., Azam L., Chadwick A., Terlau H., McArthur J.R., French R.J., Gulyas J., et al. Structure/Function Characterization of μ-Conotoxin KIIIA, an Analgesic, Nearly Irreversible Blocker of Mammalian Neuronal Sodium Channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:30699–30706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knapp O., McArthur J.R., Adams D.J. Conotoxins Targeting Neuronal Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Subtypes: Potential Analgesics? Toxins. 2012;4:1236–1260. doi: 10.3390/toxins4111236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiedler B., Zhang M.-M., Buczek O., Azam L., Bulaj G., Norton R.S., Olivera B.M., Yoshikami D. Specificity, affinity and efficacy of iota-conotoxin RXIA, an agonist of voltage-gated sodium channels NaV 1.2, 1.6 and 1.7. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008;75:2334–2344. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shen H., Li Z., Jiang Y., Pan X., Wu J., Cristofori-Armstrong B., Smith J.J., Chin Y.K.Y., Lei J., Zhou Q., et al. Structural basis for the modulation of voltage-gated sodium channels by animal toxins. Science. 2018;362:eaau2596. doi: 10.1126/science.aau2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tikhonov D.B., Zhorov B.S. Predicting Structural Details of the Sodium Channel Pore Basing on Animal Toxin Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:880. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hui K., Lipkind G., Fozzard H.A., French R.J. Electrostatic and Steric Contributions to Block of the Skeletal Muscle Sodium Channel by μ-Conotoxin. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002;119:45–54. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leipold E., DeBie H., Zorn S., Adolfo B., Olivera B.M., Terlau H., Heinemann S.H. µO-Conotoxins Inhibit NaV Channels by Interfering with their Voltage Sensors in Domain-2. Channels. 2007;1:253–262. doi: 10.4161/chan.4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leipold E., Hansel A., Olivera B.M., Terlau H., Heinemann S.H. Molecular interaction of δ-conotoxins with voltage-gated sodium channels. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3881–3884. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green B.R., Bulaj G., Norton R.S. Structure and function of μ-conotoxins, peptide-based sodium channel blockers with analgesic activity. Future Med. Chem. 2014;6:1677–1698. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li R.A., Tomaselli G.F. Using the deadly μ-conotoxins as probes of voltage-gated sodium channels. Toxicon. 2004;44:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Finol-Urdaneta R.K., McArthur J.R., Korkosh V.S., Huang S., McMaster D., Glavica R., Tikhonov D.B., Zhorov B.S., French R.J. Extremely Potent Block of Bacterial Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels by µ-Conotoxin PIIIA. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17:510. doi: 10.3390/md17090510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Favreau P., Benoit E., Molgo J., Stocklin R. Mu-Conotoxin Peptides and Use Thereof as a Local Anesthetic. 20120087969A1. US Patent. 2012 April 12;

- 62.Noreng S., Li T., Payandeh J. Structural Pharmacology of Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. J. Mol. Biol. 2021;433:166967. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berridge M.J. Neuronal Calcium Signaling. Neuron. 1998;21:13–26. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zamponi G.W., Lewis R.J., Todorovic S.M., Arneric S.P., Snutch T.P. Role of voltage-gated calcium channels in ascending pain pathways. Brain Res. Rev. 2009;60:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mochida S. Presynaptic Calcium Channels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2217. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Catterall W.A. Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:a003947. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bourinet E., Zamponi G.W. Block of voltage-gated calcium channels by peptide toxins. Neuropharmacology. 2017;127:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dolphin A.C. Voltage-gated calcium channels and their auxiliary subunits: Physiology and pathophysiology and pharmacology: Voltage-gated calcium channels. J. Pharmacol. 2016;594:5369–5390. doi: 10.1113/JP272262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vink S., Alewood P. Targeting voltage-gated calcium channels: Developments in peptide and small-molecule inhibitors for the treatment of neuropathic pain: VGCC ligands and pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;167:970–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kits K.S., Lodder J.C., Van Der Schors R.C., Li K.W., Geraerts W.P., Fainzilber M. Novel ω-Conotoxins Block Dihydropyridine—Insensitive High Voltage—Activated Calcium Channels in Molluscan Neurons. J. Neurochem. 1996;67:2155–2163. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67052155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fainzilber M., Lodder J.C., van der Schors R.C., Li K.W., Yu Z., Burlingame A.L., Geraerts W.P.M., Kits K.S. A Novel Hydrophobic ω-Conotoxin Blocks Molluscan Dihydropyridine-Sensitive Calcium Channels. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8748–8752. doi: 10.1021/bi9602674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kerr L.M., Yoshikami D. A venom peptide with a novel presynaptic blocking action. Nature. 1984;308:282–284. doi: 10.1038/308282a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patel R., Montagut-Bordas C., Dickenson A.H. Calcium channel modulation as a target in chronic pain control: Calcium channel antagonists and chronic pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018;175:2173–2184. doi: 10.1111/bph.13789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oliveira K.M., Lavor M.S.L., Silva C.M.O., Fukushima F.B., Rosado I.R., Silva J.F., Martins B.C., Guimarães L.B., Gomez M.V., Melo M.M. Omega-conotoxin MVIIC attenuates neuronal apoptosis in vitro and improves significant recovery after spinal cord injury in vivo in rats. Int. J. Clin. Exp. 2014;7:3524. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sousa S.R., McArthur J.R., Brust A., Bhola R.F., Rosengren K.J., Ragnarsson L., Dutertre S., Alewood P.F., Christie M.J., Adams D.J., et al. Novel analgesic ω-conotoxins from the vermivorous cone snail Conus moncuri provide new insights into the evolution of conopeptides. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:13397. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31245-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ramilo C.A., Zafaralla G.C., Nadasdi L., Hammerland L.G., Yoshikami D., Gray W.R., Kristipati R., Ramachandran J., Miljanich G. Novel α- and ω-conotoxins and Conus striatus venom. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9919–9926. doi: 10.1021/bi00156a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang F., Yan Z., Liu Z., Wang S., Wu Q., Yu S., Ding J., Dai Q. Molecular basis of toxicity of N-type calcium channel inhibitor MVIIA. Neuropharmacology. 2016;101:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berecki G., Motin L., Haythornthwaite A., Vink S., Bansal P., Drinkwater R., Wang C.I., Moretta M., Lewis R.J., Alewood P.F., et al. Analgesic ω-Conotoxins CVIE and CVIF Selectively and Voltage-Dependently Block Recombinant and Native N-Type Calcium Channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;77:139–148. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.058834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lewis R.J., Nielsen K.J., Craik D.J., Loughnan M.L., Adams D.A., Sharpe I.A., Luchian T., Adams D.J., Bond T., Thomas L., et al. Novel ω-Conotoxins from Conus catus Discriminate among Neuronal Calcium Channel Subtypes. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35335–35344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schroeder C., Doering C., Zamponi G., Lewis R. N-type Calcium Channel Blockers: Novel Therapeutics for the Treatment of Pain. J. Med. Chem. 2006;2:535–543. doi: 10.2174/157340606778250216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee S., Kim Y., Back S.K., Choi H.-W., Lee J.Y., Jung H.H., Ryu J.H., Suh H.-W., Na H.S., Kim H.J., et al. Analgesic Effect of Highly Reversible ω-Conotoxin FVIA on N Type Ca2+ Channels. Mol. Pain. 2010;6:1744–8069. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Favreau P., Gilles N., Lamthanh H., Bournaud R., Shimahara T., Bouet F., Laboute P., Letourneux Y., Ménez A., Molgó J., et al. A New ω-Conotoxin That Targets N-Type Voltage-Sensitive Calcium Channels with Unusual Specificity. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14567–14575. doi: 10.1021/bi002871r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Daly N.L., Callaghan B., Clark R.J., Nevin S.T., Adams D.J., Craik D.J. Structure and Activity of α-Conotoxin PeIA at Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subtypes and GABAB Receptor-coupled N-type Calcium Channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:10233–10237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cai F., Xu N., Liu Z., Ding R., Yu S., Dong M., Wang S., Shen J., Tae H.-S., Adams D.J., et al. Targeting of N-Type Calcium Channels via GABAB-Receptor Activation by α-Conotoxin Vc1.1 Variants Displaying Improved Analgesic Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:10198–10205. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cuny H., de Faoite A., Huynh T.G., Yasuda T., Berecki G., Adams D.J. γ-Aminobutyric Acid Type B (GABAB) Receptor Expression Is Needed for Inhibition of N-type (CaV2.2) Calcium Channels by Analgesic α-Conotoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:23948–23957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.342998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Klimis H., Adams D.J., Callaghan B., Nevin S., Alewood P.F., Vaughan C.W., Mozar C.A., Christie M.J. A novel mechanism of inhibition of high-voltage activated calcium channels by α-conotoxins contributes to relief of nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. Pain. 2011;152:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sadeghi M., McArthur J.R., Finol-Urdaneta R.K., Adams D.J. Analgesic conopeptides targeting G protein-coupled receptors reduce excitability of sensory neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2017;127:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Adams D.J., Callaghan B., Berecki G. Analgesic conotoxins: Block and G protein-coupled receptor modulation of N-type (CaV2.2) calcium channels: Conotoxin modulation of calcium channel function. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;166:486–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hannon H., Atchison W. Omega-Conotoxins as Experimental Tools and Therapeutics in Pain Management. Mar. Drugs. 2013;11:680–699. doi: 10.3390/md11030680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ramírez D., Gonzalez W., Fissore R., Carvacho I. Conotoxins as Tools to Understand the Physiological Function of Voltage-Gated Calcium (CaV) Channels. Mar. Drugs. 2017;15:313. doi: 10.3390/md15100313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ito Y., Araki N. Calcium antagonists: Current and future applications based on new evidence. Neuroprotective effect of calcium antagonists. Clin. Calcium. 2010;20:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Miljanich G.P. Ziconotide: Neuronal Calcium Channel Blocker for Treating Severe Chronic Pain. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:3029–3040. doi: 10.2174/0929867043363884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carvalho-de-Souza J.L., Saponaro A., Bassetto C.A.Z., Rauh O., Schroeder I., Franciolini F., Catacuzzeno L., Bezanilla F., Thiel G., Moroni A. Experimental challenges in ion channel research: Uncovering basic principles of permeation and gating in potassium channels. Adv. Phys. X. 2022;7:1978317. doi: 10.1080/23746149.2021.1978317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kuang Q., Purhonen P., Hebert H. Structure of potassium channels. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015;72:3677–3693. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1948-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Serrano-Albarrás A., Estadella I., Cirera-Rocosa S., Navarro-Pérez M., Felipe A. KV1.3: A multifunctional channel with many pathological implications. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2018;22:101–105. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2017.1420170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fomina A.F., Nguyen H.M., Wulff H. KV1.3 inhibition attenuates neuroinflammation through disruption of microglial calcium signaling. Channels. 2021;15:67–78. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2020.1853943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pérez-Verdaguer M., Capera J., Serrano-Novillo C., Estadella I., Sastre D., Felipe A. The voltage-gated potassium channel KV1.3 is a promising multitherapeutic target against human pathologies. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2016;20:577–591. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2016.1112792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Craig A.G., Zafaralla G., Cruz L.J., Santos A.D., Hillyard D.R., Dykert J., Rivier J.E., Gray W.R., Imperial J., DelaCruz R.G., et al. An O-Glycosylated Neuroexcitatory Conus Peptide. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16019–16025. doi: 10.1021/bi981690a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shon K.-J., Stocker M., Terlau H., Stühmer W., Jacobsen R., Walker C., Grilley M., Watkins M., Hillyard D.R., Gray W.R., et al. κ-Conotoxin Pviia Is a Peptide Inhibiting theShaker K+ Channel. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rangaraju S., Chi V., Pennington M.W., Chandy K.G. KV1.3 potassium channels as a therapeutic target in multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2009;13:909–924. doi: 10.1517/14728220903018957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ferber M., Al-Sabi A., Stocker M., Olivera B.M., Terlau H. Identification of a mammalian target of κM-conotoxin RIIIK. Toxicon. 2004;43:915–921. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen P., Dendorfer A., Finol-Urdaneta R.K., Terlau H., Olivera B.M. Biochemical Characterization of κM-RIIIJ, a KV1.2 Channel Blocker. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:14882–14889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Finol-Urdaneta R.K., Belovanovic A., Micic-Vicovac M., Kinsella G.K., McArthur J.R., Al-Sabi A. Marine Toxins Targeting KV1 Channels: Pharmacological Tools and Therapeutic Scaffolds. Mar. Drugs. 2020;18:173. doi: 10.3390/md18030173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kauferstein S., Huys I., Kuch U., Melaun C., Tytgat J., Mebs D. Novel conopeptides of the I-superfamily occur in several clades of cone snails. Toxicon. 2004;44:539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu Z., Xu N., Hu J., Zhao C., Yu Z., Dai Q. Identification of novel I-superfamily conopeptides from several clades of Conus species found in the South China Sea. Peptides. 2009;30:1782–1787. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kauferstein S., Huys I., Lamthanh H., Stöcklin R., Sotto F., Menez A., Tytgat J., Mebs D. A novel conotoxin inhibiting vertebrate voltage-sensitive potassium channels. Toxicon. 2003;42:43–52. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(03)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lubbers N.L., Campbell T.J., Polakowski J.S., Bulaj G., Layer R.T., Moore J., Gross G.J., Cox B.F. Postischemic Administration of CGX-1051, a Peptide from Cone Snail Venom, Reduces Infarct Size in Both Rat and Dog Models of Myocardial Ischemia and Reperfusion. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2005;46:141–146. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000167015.84715.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Savarin P., Guenneugues M., Gilquin B., Lamthanh H., Gasparini S., Zinn-Justin S., Ménez A. Three-Dimensional Structure of κ-Conotoxin PVIIA, a Novel Potassium Channel-Blocking Toxin from Cone Snails. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5407–5416. doi: 10.1021/bi9730341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Moran O. Molecular simulation of the interaction of κ-conotoxin-PVIIA with the Shaker potassium channel pore. Eur. Biophys. 2001;30:528–536. doi: 10.1007/s00249-001-0189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Finol-Urdaneta R.K., Remedi M.S., Raasch W., Becker S., Clark R.B., Strüver N., Pavlov E., Nichols C.G., French R.J., Terlau H. Block of KV1.7 potassium currents increases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012;4:424–434. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201200218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cordeiro S., Finol-Urdaneta R.K., Köpfer D., Markushina A., Song J., French R.J., Kopec W., de Groot B.L., Giacobassi M.J., Leavitt L.S., et al. Conotoxin κM-RIIIJ, a tool targeting asymmetric heteromeric KV1 channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:1059–1064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1813161116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gaskin D.J., Richard P. The Economic Costs of Pain in the United States. J. Pain. 2012;13:715–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Essack M., Bajic V.B., Archer J.A.C. Conotoxins that Confer Therapeutic Possibilities. Mar. Drugs. 2012;10:1244–1265. doi: 10.3390/md10061244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bjørn-Yoshimoto W.E., Ramiro I.B.L., Yandell M., McIntosh J.M., Olivera B.M., Ellgaard L., Safavi-Hemami H. Curses or cures: A review of the numerous benefits versus the biosecurity concerns of conotoxin research. Biomedicines. 2020;8:235. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8080235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.